94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 16 September 2021

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.697547

This article is part of the Research Topic Language Research on Sustainability, Ecology, and Pro-environmental Behavior View all 8 articles

The present article deals with environmental health literacy (EHL) in contaminated sites. The Italian national epidemiological surveillance system of population resident in contaminated sites, including vulnerable subgroups, and the local epidemiological studies and communication initiatives implemented in specific sites are considered. The Italian experience in contaminated sites corroborates the importance of EHL as a key component of community capacity to participate in mitigating environmental health risks. Effective access to evidence-based information on environmental health risk is the basis for improving awareness of local institutional and social actors. The proactive involvement of stakeholders in preventive actions and the adoption of shared practices reflect the progressive increase of their EHL. Bidirectional communication relying on participative approaches, collaborative nationallocal initiatives, and dialogue with the communities is an effective tool for increasing EHL at each site. This enhances the community capacity to use the acquired knowledge in promoting prevention actions. Consideration of socioeconomic fragilities and vulnerable groups in well-designed EHL practices contributes to prevent adverse health effects induced by specific environmental exposures and to promote environmental justice at local level.

Environmental health literacy (EHL) has its roots in health literacy (Nutbeam, 2000; Nutbeam, 2008; Sørensen et al., 2012). EHL is defined as a learning process implemented in order to develop a wide range of skills and competencies about environmental health contents that people need to comprehend, evaluate, and use. EHL is therefore based on understanding the link between environmental exposure and health (Finn and O'Fallon, 2017). The EHL concept has evolved to include community dimensions, and it has been recognized as an important long-term contributor to community empowerment (White et al., 2014; Gray, 2018; Finn and O’Fallon, 2019). EHL can contribute to advancing the application of knowledge at the individual and community level (Freedman et al., 2009; Marsili et al., 2015; Finn and O'Fallon, 2017).

Health literacy was recognized as a key pillar of health promotion strategies (World Health Organization, 2017a). The importance of promoting environmental health equity in contaminated sites was underlined in the Sixth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health of the WHO European Region held in 2017 (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2017). In the conference declaration, the topics of contaminated sites and waste management were identified among the seven priorities for action, highlighting the need for minimizing the effects of environmental chemical contaminants on vulnerable groups (WHO Regional Office for World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2017). The topic of contaminated sites was included in the second WHO European Region assessment on environmental health inequalities (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019a). A systematic review of studies on environmental health inequalities in industrially contaminated sites documented evidence of the inequalities in the distribution of risk from contaminated sites as well as the mechanisms generating and maintaining such inequalities (Pasetto et al., 2019). The results of this review were included in the WHO assessment. In most of the sites considered in the review, the assessment of environmental inequalities highlighted a disproportionate amount of socioeconomic deprivation and vulnerability (Pasetto et al., 2019).

The most comprehensive conceptual expression of environmental health equity in contaminated sites is environmental justice (EJ). The EJ has been defined in quite different ways (Holified et al., 2018). It is commonly represented through two dimensions: distributive justice and procedural justice. Distributive justice has to deal with the fairness or unfairness of the distribution of environmental risks and benefits, while procedural justice refers to the mechanisms and processes through which distributive justice is created and sustained. The key concept of procedural environmental justice is the promotion of a more inclusive participation and a fairer distribution of power in environmental decision-making (Bell and Carrick, 2018). Indeed, a frequently documented mechanism behind procedural injustice in contaminated sites is the misrecognition of communities living in the territories where potential polluting sources are located and their marginalization in decision-making processes regarding the use of their lands (Pasetto et al., 2019). These communities are often overburdened by environmental deprivation, depression in their potentialities, and/or destabilization in health and quality of life (Wilson, 2009). The misrecognition and marginalization can affect more strongly the most disadvantaged subgroups of these communities (Pasetto et al., 2019).

Following the environmental justice (EJ) paradigm (Bullard, 1990; Walker, 2012), the notion of overburdened communities is a key in contaminated sites: it applies to communities in which lower socioeconomic conditions are combined with environmental noxious exposures and associated with high health risks. In sites contaminated by industrial activities, the history of the communities living nearby has been influenced by the presence of industrial plants, which represented a source of occupation (for someone) and of deterioration of natural and built environment with the potential of affecting the health status of communities (Pasetto and Iavarone, 2020). In this context, children, because of their particular susceptibility to environmental hazards, magnify the impacts of EJ (Landrigan et al., 2010).

The social vulnerability of the communities living in contaminated sites often includes low EHL levels. EHL has been analyzed in the framework of contaminated sites to emphasize its contribution to life-long learning processes and community changes (Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2014; Davis et al., 2018; Ramírez et al., 2019). In this framework, communication can be used as a tool for increasing EHL. A dialogue with the communities exposed to environmental and health risks focused on epidemiological data, and the sociocultural context (Tan and Cho, 2019) can promote EHL of engaged institutional and social actors fostering community empowerment (Marsili et al., 2019a).

In Italy, the notion of contaminated sites formally appeared in the national regulatory frame in 1986 with the creation of the Ministry of Environment. The Ministry set up a procedure for defining and identifying the areas of the country called “areas at high risk of environmental crisis”, where particular anthropogenic activities might have determined risks for human health. In 2006, the Ministry of Health assigned to the Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità; ISS) the commitment to design and implement the SENTIERI program. SENTIERI stands for National Epidemiological Study of Territories and Settlements Exposed to Pollution Risk, which has become a permanent epidemiological surveillance system of populations living in contaminated sites.

The aim of this article is to discuss the importance of EHL in contaminated sites by analyzing communication initiatives and participative approaches undertaken within both the Italian national epidemiological surveillance system of resident communities living close to contaminated sites (SENTIERI) and local epidemiological studies in specific contaminated sites. We describe how structured communication can contribute to increase EHL of the involved institutional and social actors in contaminated sites. We also discuss how the activities undertaken at national and local scales can strengthen environmental health equity in a public health perspective. Qualifying elements for EHL and environmental health equity are presented and discussed in both the selected national and local frameworks, highlighting the implications for EJ.

SENTIERI and the local epidemiological studies in specific contaminated sites have been chosen as exemplars because they are both representative of contexts in which promoting the adoption of preventive actions through the increase of awareness of institutional actors and resident communities. These actions rely on communication of evidence-based scientific knowledge and collaborations among key actors to promote participative decision-making. The communication strategies implemented at national and local scales as well as the collaborative approaches, adopted to strengthen the relationships between institutional and social actors in contaminated sites in Italy, are analyzed as key elements of EHL in promoting environmental health equity and EJ.

We have chosen SENTIERI because it represents a national, coordinated, authoritative, initiative to share and adopt strategies for communication in contaminated sites (Marsili et al., 2019b). In particular, we analyze and discuss in this article the SENTIERI communication strategy focusing on the engagement of local institutional and social actors to foster health prevention initiatives and environmental remediation.

The contaminated sites included in SENTIERI are those defined by the Ministry of Environment as National Priority Contaminated Sites (NPCSs) for remediation, consistent with the European guidelines concerning contamination of soil, underground and surface water, and food chain. SENTIERI investigates the health profile of the population living in NPCSs considering the patterns of environmental contamination of the sites and the available health information systems (Pirastu et al., 2013a). The last update of the SENTIERI epidemiological surveillance examined the health profile of population living in 45 NPCSs accounting for about 5,900,000 inhabitants on the basis of mortality, cancer incidence, and hospitalization data (Zona et al., 2019). Results of the multi-outcome surveillance, over an 8-year time window, showed an excess of overall mortality corresponding to about 5,000 (+4%) deaths in men and 7,000 (+5%) in women, of which about 3,000 and 2,000, respectively, were due to cancer. The adverse health outcomes in excess included mesothelioma, lung, gastric, and colon cancer and non-malignant respiratory disease. These excesses of adverse health effects occurred in areas characterized by the presence of oil refineries, petrochemical facilities, steel industries, former asbestos manufacturing plants, and hazardous waste dumping sites.

SENTIERI also focuses on vulnerable age-related subgroups of resident population: children, adolescents, and young adults. The last update of the SENTIERI epidemiological surveillance concerned about 1.2 million children (0–19 years) and 660,000 young people (20–29 years) residing in the 45 NPCSs. Results showed excess risks of hospital admissions in kids (<1 year) and children (0–14 years) for natural ill causes and for acute respiratory diseases and asthma, as well as excesses of some cancer types in children and young adults (Zona and Bruno., 2009; Iavarone et al., 2018). Environmental health equity and its relation with EHL are examined to discuss the environmental and health risks of vulnerable age-related population subgroups (children, adolescents, and young adults). Children are usually unaware of the environmental threats and are therefore unwittingly exposed to dangerous chemicals unable to avoid their effects. Moreover, children have distinctive activity patterns, behavior, and physiology that make them more vulnerable to environmental hazards (Landrigan et al., 2010; World Health Organization, 2017b) than adults. Critical aspects in children’s health profile can thus be regarded as a predictor of environmental impact on the population at study. For instance, children are uniquely vulnerable to the damaging health effects of air pollution. The high impact of air pollution on children’s health is a strong indicator of unsafe air quality, as their lungs are rapidly developing and therefore more vulnerable to inflammation and other damage caused by pollutants (World Health Organization, 2018).

Increasing EHL through the communication of results of systematic assessment of children’s health in contaminated areas allows the identification of social inequalities in exposure, as lower socioeconomic status communities are more frequently found to reside in areas contaminated by industrial emissions and/or hazardous waste (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2010; to be withdrawn World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019b; NIEHS, 2021).

Among the issues being studied in SENTIERI, two are of pivotal importance for EHL of the involved institutional and social actors: sharing communication strategies and EJ. The SENTIERI communication strategy has been progressively implemented by integrating social sciences and environmental epidemiology skills (Hoover et al., 2015; Marsili et al., 2019b). To this task, a prototype communication plan has been defined based on a methodological approach (Marsili et al., 2017) relying on the identification of target audiences, the adoption of tailored communication messages, and effective tools to engage local stakeholders such as participative meetings to share and address their contributions and concerns. All these aspects are extremely relevant to promote EHL in a contaminated community (Ramírez et al., 2019).

SENTIERI addresses inequalities among municipalities included in NPCSs through an index of multiple deprivations computed using socioeconomic variables derived by National Census data, such as percentage of residents with a primary education degree or below, percentage of the active population unemployed or searching for a first job, percentage of rented habitations, and household crowding (as dwellers/100 m2) (Pasetto et al., 2017). The first assessment of inequalities among municipalities followed by SENTIERI (Pasetto et al., 2017) showed that most of the municipalities have a high deprivation level. Furthermore, it highlighted a marked northsouth gradient, with worst conditions in the South and Islands, where 82% of municipalities close to contaminated sites fall into the two lowest socioeconomic status quintiles. Finally, it showed that municipalities with a higher deprivation also have a higher risk of mortality, especially in men (Pasetto et al., 2017).

Local frameworks are analyzed in this article, because it is the context where EHL determines the degree of acquired knowledge for undertaking participative prevention actions. Two NPCSs have been selected as representative of the local framework, namely the site of Milazzo (Sicily) and Porto Torres (Sardinia), because they present distinguishing features. Indeed, the Milazzo NPCS is characterized by long-lasting collaborations and communication initiatives involving both local health authorities and social actors, while in the Porto Torres NPCS, these initiatives are employed for the first time. We discuss EHL and environmental health equity-related issues in the two NPCSs in the light of both the evidence of distributive injustice among municipalities followed up by SENTIERI (Pasetto et al., 2017) and the community capacity to participate in prevention actions in contaminated sites (Pasetto et al., 2020).

The contaminated site of Milazzo was included by the Italian Government among the NPCSs in 2006. It includes the municipalities of Milazzo, San Filippo, and Pace del Mela in the Mela Valley (northeast Sicily), where 45,599 people live (2011 Census) (Zona et al., 2019). The environmental contamination is due to the presence of hydrocarbons and metals in soil and groundwater and an atmospheric widespread contamination caused by the industrial emissions of a refinery, a steel foundry, a power plant, a chemical facility of electric equipment production, and a storage plant of appliances. Moreover, the area of the former asbestos-cement plant (Sacelit Company) located in San Filippo del Mela has been identified as a source of environmental contamination and included in the NPCS in 2007. The plant was installed in 1958 and operated until 1993, 1 year after the national asbestos ban. During the operational period, about 220 people worked in the plant. The facility processed about 2,000 tons of asbestos mixture (including crocidolite) annually, with 16,000 tons of cement, without any personal protection device and air filtration systems, until mid-1970s. Widespread contamination by asbestos fibers and a lack of well-separated areas for specific activities were reported by the Committee of former exposed workers of Sacelit (https://comitatoespostiamianto.it). Asbestos-related diseases were highlighted by SENTIERI-ReNaM Report on the incidence of mesothelioma cases in NPCSs (GdL Sentieri-ReNaM, 2016) and by a ReNaM Report on the occurrence of occupational diseases in NPCSs mentioning the asbestos-cement plant among the involved occupational sectors (Brusco et al., 2019). A collaborative framework among national and regional institutions and the local Committee of former exposed workers of Sacelit has been continuously implemented in the last 2 decades.

The contaminated site of Porto Torres is located immediately close to the homonymous municipality in northwestern Sardinia, and it also includes the larger Sassari municipality. The contaminated area includes several petrochemical and chemical plants (most of them decommissioned), a thermoelectric power plant, and a harbor area. The Porto Torres industrial complex started its operation in 1962. In the 1970s, the industrial production increased, and at the same time, the first evidence of environmental contamination was observed, increasing the public concern about the atmospheric pollution in the residential area (Brigaglia and Ruju, 2012). The industrial area of Porto Torres was included among the NPCSs in 2002 because of the identification of widespread contamination of soil and water. SENTIERI documented the health profiles for the Porto Torres site combining figures of the two municipalities of Sassari and Porto Torres. Results showed an excess risk of mortality and hospitalization in both genders for all causes combined (i.e., overall mortality and causes of hospitalization) and for the subgroups of respiratory diseases and all cancers. The latter result was confirmed also by cancer incidence data (Zona et al., 2019). The case of Porto Torres is an exemplary case of what happened in several areas where petrochemical complexes were built in the 2 decades after the Second World War in southern Italy. It is an example of industrial development that exhausted its local positive impact within one generation, leaving a degraded and polluted environment for future generations. The inhabitants of Porto Torres municipality have yet to receive any information about the potential role of industrial contamination in affecting the health of their community.

The methodological approach proposed in this article relies on linking the national epidemiological surveillance system (SENTIERI) with local epidemiological studies using structured communication and the involvement of local institutional and social actors to foster EHL and promote health prevention actions.

Results are presented here for the national and the local frameworks emphasizing the outcomes of communication and collaboration activities and the implications for environmental health equity.

The publication of the study findings in peer-reviewed scientific journals was considered in the SENTIERI network a necessary but not a sufficient step. The communication of evidence-based results to well-identified target audiences became a key commitment and a relevant activity to be progressively implemented. For this reason, the target audiences for dissemination of the SENTIERI findings also include the nonexpert sections of society (such as other stakeholders and community members). Over the years, the SENTIERI Reports have been disseminated to a progressively growing list of target audiences, including the Ministries of Environment and of Health, the 20 Italian Regional Governments, the Regional Environmental Protection Agencies, and the Local Health Authorities, the Mayors of about 300 municipalities included in the territory of the NPCSs (Figure 1).

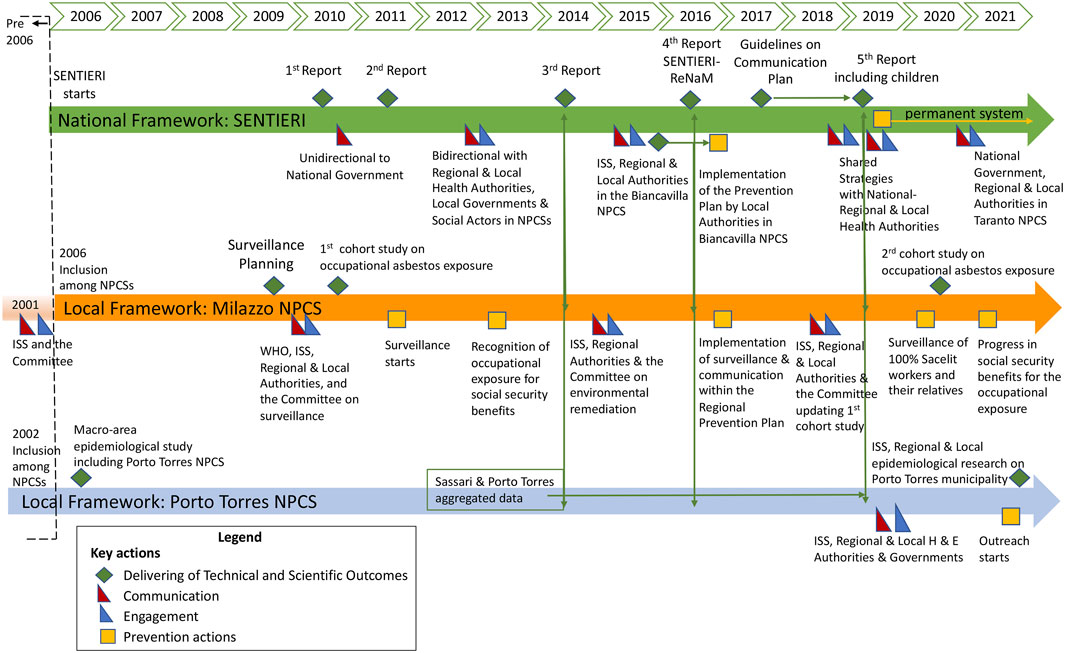

FIGURE 1. Diagram representing a timeline detailing the key undertaken actions: namely, sharing Technical and Scientific Outcomes (green diamonds), Communication and Engagement (red and blue triangles, respectively), and their relations with prevention actions (yellow squares) for the national (top green arrow) and local (bottom orange and cyan arrows) frameworks discussed in this study. The vertical bidirectional (green) arrows highlight the sharing of SENTIERI findings with local stakeholders. The horizontal unidirectional (green) arrows depict the connections among some actions. Prevention actions involved local health authorities and social actors and followed communication and engagement actions as well as the delivering of scientific outcomes.

Since 2011, the SENTIERI findings were officially presented at national level during institutional meetings. Because of the national feature of the epidemiological surveillance in NPCSs, SENTIERI provoked a lot of interest, sometimes controversial, among researchers, institutions, and community of residents since the first results’ publication (Pirastu et al., 2011). The SENTIERI results were presented in numerous meetings organized at regional level (Piedmont, Tuscany, Apulia, Sicily, Venetia, and Lombardy) and concerned both the national surveillance system and the community residents’ health profile in the specific NPCSs. These meetings made evidence-based information available to the attendees, providing useful insights to discuss EHL’s facets. The audience was often composed of a mix of citizens, local organizations, researchers from the local universities, physicians, environmental experts, local administrators, and journalists with different information needs and levels of EHL. The events had good media coverage; speakers were interviewed by journalists from local and regional newspapers and TVs. During the debates, many questions were asked, and some controversies arose on specific methodological issues as well as on the actual meaning of the presented data. These events represented an opportunity for overcoming unidirectional communication, because they were a true occasion of discussion between experts and stakeholders, including community members. This required the researchers to use plain language and a dialogue-oriented approach. The institutional meetings represented an effective tool to strengthen the relationships between institutional and social actors as well as to increase awareness of the involved community regarding environmental health risks. This demonstrates that a bidirectional communication model is vital in establishing effective collaborations.

Relying on previous experience and with the aim of fostering the adoption of structured communication processes in contaminated sites, SENTIERI has established a distinct communication strategy. A prototype communication plan has been designed following a methodological approach and involves cross-disciplinary expertise (Marsili et al., 2017). The plan promotes integration between the environment and health sectors aimed at consolidating prevention activities through participatory processes in decision-making. The communication plan includes guidelines tailored for health and environment institutional actors to foster its shared implementation and the adoption of structured communication activities.

The plan has been discussed with the regional and local health authorities for implementation in the local contexts. It is known to be essential to adopt suitable practices for sharing evidence-based knowledge of the health impact of environmental contamination including the associated uncertainties (Marsili et al., 2019b). Indeed, participative communication processes involving all the relevant stakeholders contribute to increased individual and collective EHL as a sociocultural component of resilience of the contaminated communities (Zarcadoolas et al., 2005; Freedman et al., 2009; Marsili et al., 2019a). This communication strategy has been considered among the operational indications for risk communication in contaminated sites by the Environment and Health Task Force of the Italian Ministry of Health as well as among the best practices for risk communication by the European network of institutions participating in the COST Action Industrially Contaminated Sites and Health Network (ICSHNet) (Iavarone and Martuzzi, 2019).

Among the numerous initiatives promoted by SENTIERI aimed at increasing EHL of institutional and social actors in Italian contaminated sites, we report in the following two experiences matured in two different NPCSs in Sicily to strengthen relationships between national-local involved actors and to mitigate environmental and health risk.

In our first example, we cite a communication activity that has been conducted in the Augusta-Priolo NPCS (Sicily) to present population health results for a community living in the presence of a major refinery and petrochemical industrial plant. A video was developed to present the environmental degradation of the area surrounding the industrial settlement together with the social implications for the affected community. The video benefitted from the strong collaboration with the local members of the national NGO Legambiente (https://www.legambiente.it/english-page/). Scientists, local authorities, and social actors were interviewed and shown in the video. The video was a tool to engage institutional and social actors at local scale. This communication initiative has strengthened the existing collaborations with local health authorities. An English short version of the video was produced for the aforementioned European network “ICSHNet” as a national-local collaborative initiative in contaminated sites (ICSHNet, 2019).

A dedicated communication initiative was also implemented by SENTIERI in the Biancavilla NPCS (Sicily) to increase EHL concerning prevention of exposure to a naturally occurring carcinogen, namely fluoro-edenite, in collaboration with the Regional Health Authority. Subsequently to the detection of a significant excess of mortality due to pleural mesothelioma in this town, located at the slopes of Etna Volcano, in the absence of occupational asbestos exposure, a previously unknown naturally occurring asbestiform fiber was detected in the soil of the area. The area includes a stone quarry from which building material was extracted and used in the local construction industry. The fiber was named fluoro-edenite and eventually classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a human carcinogen (Group 1) (IARC, 2017). The implementation of these activities was facilitated by the relationships with the local institutional actors. A set of primary prevention and health promotion interventions were provided to local health operators, administrators, institutions towards media, local educational system (teachers and students) (Bruno et al., 2015). Public meetings with citizens and social actors were held to communicate health risks from fluoro-edenite exposure as well as preventive actions. This contributed to strengthening prevention and behavioral change initiatives. A key indicator demonstrating the successful communication and the effective increase of EHL of local actors is seen by the inclusion of the shared prevention actions in the Sicilian Regional Plan of Health Interventions in the contaminated site of Biancavilla (Sicilia Regione, 2015) (Figure 1).

From the public health and equity perspective, increasing EHL of local institutional and social actors is essential to manage the health risks of vulnerable groups of population, such as children and youth age groups. This is considered a key issue in SENTIERI. As compared to the general or adult population, a higher uncertainty is usually associated with the risk estimates in both childhood and youth due to statistical aspects and scarce data linking environmental exposures to health effects, like cancer in children. Indeed, the currently available evidence linking childhood cancer to exposure to environmental carcinogens is largely inadequate for many chemicals that have been classified as carcinogenic in adults. The main limitations are generally associated with inadequate study design, scarce availability of exposure, and outcome data, and the small fraction of children exposed to environmental carcinogens in common residential settings. Therefore, studying communities living in areas with high levels of carcinogens is expected to empower the ability of epidemiological studies to detect excess risks of cancers in children (Iavarone et al., 2018). Moreover, communicating epidemiological results related to children and youth age groups requires cautiousness because of the high social impact of these findings. We use the case of the Taranto NPCS to illustrate the SENTIERI outcomes and to discuss the impact of communicating information related to children’s health on the perception of risk among relevant stakeholders.

TARANTO NPCS. The site is located in Apulia Region (southern Italy), which includes two municipalities (about 200,000 inhabitants), characterized by the presence of one of the largest steel plants in Europe, a refinery and other industrial productions, which was responsible for large and diffuse contamination with impacts on environment, health, and society (Pirastu et al., 2013b; Zona et al., 2019). SENTIERI strongly contributed to identifying the diseases in excess in the health profile of local residents (Pirastu et al., 2011; Comba et al., 2012; Iavarone et al., 2013; Pirastu et al., 2013a; Crocetti et al., 2014; Santoro et al., 2017; Zona et al., 2019) and the transfer and sharing of evidence-based knowledge with national and local stakeholders (Figure 1). This contribution became even more important when epidemiological data concerning excess risks of some tumors and congenital malformations in children and in young adults (Zona et al., 2019) became publicly available after their presentation in a public conference held at the Ministry of Health. The information distributed by most media (mainly via web) was often alarming and contributed to fear, outrage, and sense of impotence in local communities. Many alarming headlines appeared in the press, in television broadcasts, and especially on the web. The FIDH, an international human rights NGO federating 184 organizations from 112 countries, produced a document “The Environmental Disaster and Human Rights Violations of the ILVA steel plant in Italy” (FIDH, 2018). The Report takes into consideration the contribution of SENTIERI in identifying health risks in both general population and in the children and youth age groups and concluded with a series of recommendations to the Italian Government, including those aimed at fostering children’s health. The Taranto experience corroborates the importance of increasing EHL on children’s health surveillance as a key activity of SENTIERI for the contaminated communities.

The Milazzo NPCS is of particular interest for EHL, because it involves different stakeholders in a long-lasting process of interactions relying on a bidirectional communication. In 2001, some former workers of Sacelit asbestos-cement plant established a Committee “of former exposed” (https://comitatoespostiamianto.it/) in order to support their colleagues in accessing services for health care and social security. The collaboration between the Committee and the ISS researchers started in 2001, and it is still ongoing (Figure 1). The interaction between researchers and social actors was facilitated by the continuous exchange of information and the joint participation in local communication events. Following the public announcement made by the Committee and by local environmental NGOs as well as by the researchers, a team of the Ministry of Environment documented the environmental asbestos contamination of the area of ex-Sacelit that led to its inclusion in Milazzo NPCS in 2007. A collaboration agreement was signed by the Committee and the Local Health Authority aimed at implementing a plan for the health surveillance of the former asbestos-exposed subjects and their relatives and ISS collaborated to define the protocol for health surveillance (Zona et al., 2009; Zona et al., 2010).

The collaboration among ISS, the Committee, and the Local Health Authority relies on the adoption of a common language. The Committee voluntarily provided the list of exposed workers (not made available by Sacelit Company) in order to support the identification of occupational diseases and the people entitled to social security benefits. The list was further shared with ISS, to identify the former workers’ cohort, after review and validation by official records of the Italian Workers Compensation Authority. Since its design, all phases of the study were shared, and the methodological aspects and the communication of results were the objects of periodical meetings between the involved researchers and the Committee (Figure 1). Awareness of the different roles and tasks has characterized the relationships based on mutual respect, helpful in managing divergent conclusions in attributing individual cases to asbestos exposure. ISS performed an occupational cohort study on the San Filippo del Mela asbestos plant in order to assess the possible impact of occupational exposures on the health profile of the population (Mudu et al., 2014). The study was undertaken within a scientific collaborative framework supported by the WHO Regional Office for Europe, which included national and local institutions (such as ISS, the National Research Council, and the Regional Epidemiological Observatory). The communication experiences matured in the Milazzo NPCS confirm the importance of increasing EHL through participative initiatives at local level and the need for ongoing collaborations among national and local institutional and social actors.

The increased compliance over time of local and institutional actors with EHL is corroborated by various evidence, namely by the growing use of knowledge acquired in the frame of epidemiological studies in designing novel preventive actions. The cohort studies on the health status of the former workers of Sacelit partially filled the existing gap of evidence-based knowledge on the health impact of occupational exposure to asbestos in Sicily, and at local level, in San Filippo del Mela (Fazzo et al., 2010; Fazzo et al., 2020). In the equity perspective, these study findings were used by the Committee and the affected workers for the recognition of occupational diseases, a necessary step to adopt social security benefits for the workers and their relatives (Figure 1). Moreover, the health surveillance plan (Zona et al., 2010) represents one of the first experiences in Italy that uses health surveillance to monitor health outcomes of former asbestos-exposed workers and their relatives. The health surveillance plan nowadays includes all former Sacelit workers as well as the workers of other facilities in the Messina province and their relatives (Figure 1).

The awareness of the health risks of exposure to contaminants had its birth within the working environment, but it nowadays also concerns residential and environmental exposures. The Committee and other environmental NGOs and local organizations are active in initiatives aimed at promoting environmental remediation of the site. The Regional Government is carrying out a Plan of Health Interventions in the areas at high risk for environmental crisis, including Milazzo NPCS, and addressing epidemiological and health surveillance initiatives and communication activities with the affected communities (Sicilia Regione, 2013) (Figure 1).

An institutional collaboration has been established between the ISS and the regional and local health authorities of Porto Torres aimed at fostering capacity to address environmental health issues associated with industrially contaminated sites. An epidemiological study has been designed and implemented to describe the health profile of the population residing in the municipality of Porto Torres by adopting a systematic and inclusive approach for the collection of environmental and health data and the communication of the study findings to the community. The activities planned for the Porto Torres NPCS are dedicated to strengthening the scientific and technical capacities of the Sardinian health professionals and operators. This capacity-building initiative has been designed to increase the EHL of both regional and local environmental and health authorities, including the regional and local communication offices.

The planned communication activities are aimed at presenting the findings from the epidemiological study to the community living in the Porto Torres municipality and rely on the use of a form of language (i.e., words, expressions) appropriate to the different target audiences according to their level of literacy. Contents have been implemented, and different channels have been identified to effectively involve the local institutional actors in undertaking communication activities (e.g., communication through institutional websites of regional and local authorities, production and dissemination of outreach materials to be used in workshops, public meetings, and other initiatives for feedback reporting) (SardegnaSalute, 2021a) (Figure 1). An example of interactive tool that has been developed is the interactive map of the epidemiological study, including a glossary with definitions translating commonly used scientific words into lay language, to promote effective access to scientific information by the resident community (SardegnaSalute, 2021b). The implementation of the plan also foresees the engagement of the local educational system for developing training-to-trainers and peer-to-peer activities aimed at fostering the empowerment of the young population of Porto Torres. The proposed approach relies on the previous experiences of the schools’ network of the Casale Monferrato municipality (Piedmont region) located in an asbestos-contaminated area, already included among the NPCSs (Marsili et al., 2019c). The assessment of the performed activities is also built into the plan.

The current institutional collaboration is strengthening the inter-sectoral relationships between the involved environmental and health institutional actors at local level, as demonstrated by the joint participation in the communication activities as well as by the sharing of data for the epidemiological study. The cross-disciplinary approach promoted by SENTIERI has created a collaborative context suitable to share practices for communicating to the resident community, as demonstrated by the adoption of the SENTIERI communication plan. This is further evidence that collaboration and communication activities have been improving EHL of the institutional and social actors at local level.

Although the Porto Torres NPCS is one of the main industrially contaminated sites in Sardinia, little epidemiological data are available to date (Biggeri et al., 2006; Zona et al., 2019). Porto Torres NPCS includes for administrative reasons (i.e., for remediation activities) the two municipalities of Porto Torres (about 22,400 inhabitants) and Sassari (about 124,000 inhabitants). Porto Torres is immediately close to the industrial complex, while the town of Sassari is more than 20 Km away from the industrial site. SENTIERI provides health profiles for Porto Torres NPCS aggregating data of the two municipalities. Therefore, the figures on health profiles provided by SENTIERI do not only focus on the population mainly exposed to noxious factors from the contaminated site. The lack of epidemiological data combined with the request of information of the local population on the potential role of industrial contamination in affecting their health status makes Porto Torres municipality an exemplary case of unfair treatment that requires priority actions. The current scientific collaboration, relying on newly provided epidemiological data on Porto Torres municipality, represents the action necessary to understand the health profile of residents. Moreover, the shared implementation of structured communication represents a framework by which EHL of institutional and social actors can be increased.

Increasing EHL of regional and local health institutions is strengthening the bottom-up capacities and the autonomy to design and develop environmental and health data processing, epidemiological surveillance, and communication activities in Porto Torres. The current collaborative initiative is designed to respond to the needs of the local community, to enable the use of knowledge for prevention, and to promote environmental health equity.

The communication and collaboration experiences concerning the national epidemiological surveillance system SENTIERI and the epidemiological studies in NPCSs are discussed in this article to highlight the processes through which EHL can strengthen community capacity to participate in mitigating environmental health risks. The empowerment of affected communities is discussed as an indicator of increased EHL essential to promote EJ.

Figure 1 shows a diagram representing a timeline detailing the key actions, namely sharing technical and scientific outcomes, communication, and engagement, for the SENTIERI national framework and for the Milazzo and Porto Torres local frameworks. The timeline includes the prevention actions undertaken in each framework to show their relations with the key actions. The links between the national and the local frameworks and the sharing of SENTIERI findings with local stakeholders are also depicted in the figure (vertical green arrows). The figure highlights that prevention actions follow communication and engagement actions as well as the sharing of scientific outcomes. The participation of local health authorities and social actors in preventive actions is interpreted here as a corroborating evidence of the increase of their EHL. The diagram shown in Figure 1 also illustrates that the communication and the sharing of scientific results are a continuous and incremental process that is based both on the adopted methodological approach and on the implementation over time of collaborative contexts with local stakeholders.

Effective access to evidence-based information on environmental health risk is the basis for improving knowledge and awareness of institutional and social actors in NPCSs, relying on the adoption of lay language and the provision of tailored messages. This is the essential root of EHL (Gray, 2018). The bidirectional communication adopted by SENTIERI has encouraged the mutual understanding among researchers and the involved institutional and social actors. This approach is fundamental for promoting the evolution of awareness into expertise and motivation both to follow behavioral changes that protect individual health and to enable the participation in community decision-making processes.

The lens of equity is needed when undertaking epidemiological surveillance and communication regarding children’s environmental health. Lower socioeconomic status communities have little control over their environment and scarce ability to choose the place where to live. These aspects are strongly amplified in contaminated areas, where children living and playing outdoor might particularly experience higher exposure to toxicants and related health effects than adults. This requires that available scientific knowledge should be used to address evidence-based preventive actions by local and regional authorities. EHL can be a suitable tool to empower social awareness and to provide parents, pediatricians, family doctors, teachers with suitable information on how to protect children in contaminated areas. Communicating the results of children’s health surveillance in contaminated sites has several implications on the role of EHL in fostering the interpretation of study findings and the adoption of conscious behaviors by stakeholders. The increased health risks observed in children and youths are usually found to couple with bad health profiles also in the general adult population in the same contaminated sites, augmenting the resolution capacity of the surveillance system to characterize inequities at community level, and consequently to increase EHL in terms of knowledge to prepare the relevant stakeholders to make health-protective decisions using available data.

Milazzo NPCS. The experience of Milazzo-contaminated site highlights the importance for individuals and communities to move along a continuum of EHL, not limited to knowledge about the impacts of asbestos exposures in working and living environments, rather enabling the use of new knowledge for prevention actions through effective partnerships among researchers, social actors, and local health authorities. The Milazzo experience is indeed a bottom-up initiative in which local social actors were supported by a national research Institute and by the local and regional health authorities (Figure 1). This partnership is still today representing the framework in which growing EHL. Sharing knowledge on the social context and the scientific methodology and evidence of environmental contamination and health-related impacts among researchers and local actors have built trusting relationships and increased the awareness of researchers about community expectations.

Porto Torres NPCS. The recent experience of Porto Torres shows the need for targeted capacity building with local institutional actors to improve their EHL. This aspect implies strengthening capacities to design and conduct epidemiological studies and communication initiatives involving the whole community. The effectiveness of communication in contaminated sites and the contributions of EHL depend on the local socio-cultural conditions. The readiness of local actors, such as health professionals and local health authorities, and local organizations to undertake actions supported by institutional communication also depends on the political setting and the response of local authorities. This response is more easily achieved when appropriate social and cultural conditions exist in the specific context of the contaminated site, fostered by the available linking social capital such as the existing networks of trusting relationships among social actors and involved institutions (Solar and Irwin, 2010). The value of linking social capital in contrasting inequities and promoting health equity has been recognized by WHO as a cross-cutting component to the structural social determinants of health inequities and the intermediate social determinants of health (Solar and Irwin, 2010).

The two local experiences in Milazzo and Porto Torres NPCSs described in the present article confirm the importance of the existence of a national authoritative framework to promote collaborations with local authorities and social actors for supporting the local capacity and actions as well as to activate local empowerment (Marsili et al., 2019a) (Figure 1).

The empowerment of national and local authorities for adopting environmental and public health practices has the potential to reduce inequities in the distribution of environmental risks, since most contaminated site communities or population subgroups living nearby contaminated areas are prone to be fragile (in socioeconomic terms) (Pasetto et al., 2019; Pasetto and Fabri, 2020).

Tailored communication by national authoritative initiatives, such as the one promoted by SENTIERI, can strengthen the empowering processes at local scale (Figure 1). Specific cultural context (White et al., 2014) must be considered in order to ensure that the culturally specific knowledge of lower socioeconomic status groups in each contaminated site is considered in tailored EHL initiatives (Gray, 2018). For these vulnerable groups, modest health literacy is often correlated with poor health and reduced access to health services (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2012).

Suitable strategies for EJ promotion in contaminated areas should start from developing EHL for disadvantaged population subgroups able to address the local origin of their inequalities. In this framework, communication can be used as a tool for increasing EHL (Pasetto et al., 2020). Taking into consideration the organizational efficiency of local institutions as well as the occupational and socioeconomic conditions in each contaminated site is essential to assess distributive and procedural injustice and to design strategies for promoting EJ at local level (Pasetto et al., 2019).

The evidence presented in this article demonstrates the importance of EHL as a key component of community capacity to participate in mitigating environmental health risks. The implementation of shared prevention actions adopted by institutional and social actors in contaminated sites represents the main indicator of the effectiveness of the undertaken communication and collaboration activities. The appropriate use of the acquired knowledge and the awareness expressed by the proactive participation in preventive actions by the local institutional and social actors are representative of the progressive increase of their EHL contributing to empowering contaminated communities.

Increasing EHL of communities living in contaminated sites is a social process necessary to enable participative approaches related to decision-making and to strengthen community capacity to mitigate environmental health risks.

In this article, we have discussed the effectiveness of structured communication and participative collaboration activities to raise knowledge about specific risks as well as awareness and preparedness for the reduction of exposure to hazardous agents and the improvement of the health status of the communities living in contaminated sites in Italy. We have shown that communication strategies relying on a dialogue with the communities living in contaminated sites improve EHL as they provide the basis for prevention and risk management, in turn, addressing environmental health equity.

The experiences described in the present article concern epidemiological surveillance and communication in contaminated sites performed at national and local scales in Italy. Environmental health communication provided by a national surveillance system supports epidemiological studies and collaboration activities developed at local level by sharing strategies for structured communication in the local contexts of the contaminated sites. The relationships between national and local actors dealing with environmental and health impacts are therefore developed in such a way that engaged stakeholders on one side can influence the actions on the other side. Findings from this article will be useful for other researchers and health professionals dealing with national epidemiological surveillance and local epidemiological studies in contaminated sites from a public health and equity perspective.

The health impact of living in contaminated sites comes with various health risks, ranging from exposure to specific pollutants in air, water, soil, and the food chain, to the adoption of unhealthy behaviors often exacerbated by lower socioeconomic conditions. Naming these determinants of disease and illuminating their respective etiological role with the support of well-designed practices of EHL will help in pursuing and, to some degree, achieving the promotion of EJ.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

DM conceived the conceptual design of the paper. DM, PC, and RP contributed to the structured methodology; DM elaborated the interpretation of the data, drafting, and critically revising the manuscript; DM, RP, II, LF, AZ, and PC contributed to the writing and the revision of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for the plain content of the work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bell, D., and Carrick, J. (2018). “Procedural Environmental Justice,” in The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice. Editors R. Holifield, J. Chakraborty, and G. Walker (New York: Taylor & Francis), 101–112.

Biggeri, A., Lagazio, C., Catelan, D., Pirastu, R., Casson, F., and Terracini, B. (2006). Ambiente e salute nelle areee a rischio della Sardegna [Environment and health in high risk areas of Sardinia, Italy] Epidemiol. Prev. 30(1): Suppl 1. online. Available at: http://www.epidemiologiaeprevenzione.it/materiali/ARCHIVIO_PDF/Suppl/2006/EP_V30I1S1.pdf. (Accessed December 9th, 2020).

Brigaglia, M., and Ruju, S. (2012). Industria e Territorio nel Nord-Ovest della Sardegna. Cinquant'anni del Consorzio Industriale Provinciale di Sassari. online. Sassari, Italy: Consorzio industriale provinciale di Sassari. Available at: https://www.cipsassari.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/industria_e_territorio_nel_nord_ovest_della_sardegna_50_anni_del_cip_web.pdf (Accessed December 9th, 2020).

Bruno, C., Marsili, D., Bruni, B. M., Comba, P., and Scondotto, S. (2015). Prevenzione della patologia da fluoro-edenite: il modello Biancavilla. Percorsi di ricerca, interventi di sanità pubblica e di promozione della salute [Preventing fluoro-edenite related disease: the Biancavilla model. Research, public health and health promotion intervention], 28, 5Suppl. 1. Not Ist Super Sanità, 3–19. Available at: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/45616/ONLINEBiancavilla.pdf/9e93d72a-9fd6-569a-f6f8-3c86353610bb?t=1581097428228. (Accessed December 5th, 2020).

Brusco, A., Binazzi, A., Altimari, A., Bonafede, M., Boscioni, R., Clemente, M., et al. (2019). Le malattie professionali nei siti di interesse nazionale per le bonifiche (SIN). Inail: Milano, Italy; online. Available at: https://www.inail.it/cs/internet/docs/malattie-professionali-sin-2019.pdf. (Accessed November 5th, 2020).

Bullard, R. (1990). Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Oxford, UK: Westview Press.

Comba, P., Pirastu, R., Conti, S., De Santis, M., Iavarone, I., Marsili, G., et al. (2012). Environment and Health in Taranto, Southern Italy: Epidemiological Studies and Public Health Recommendations. Epidemiol. Prev. 36 (6), 305–320. Italian. PMID: 23293255.

Crocetti, E., Pirastu, R., Buzzoni, C., Minelli, G., Manno, V., Bruno, C., et al. (2014). SENTIERI Project: Results. Epidemiol. Prev. 38 (2 Suppl. 1), 29–124. Italian. PMID: 24986500.

Davis, L., Ramirez-Andreotta, M., McLain, J., Kilungo, A., Abrell, L., and Buxner, S. (2018). Increasing Environmental Health Literacy through Contextual Learning in Communities at Risk. Ijerph 15 (10), 2203. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102203

Fazzo, L., Nicita, C., Cernigliaro, A., Zona, A., Bruno, C., Fiumanò, G., et al. (2010). Mortality from asbestos-related causes and incidence of pleural mesothelioma among former asbestos cement workers in San Filippo del Mela (Sicily). Epidemiol. Prev. 34 (3), 87–92.

Fazzo, L., Cernigliaro, A., De Santis, M., Quattrone, G., Bruno, C., Zona, A., et al. (2020). Occupational Cohort Study of Asbestos-Cement Workers in a Contaminated Site in Sicily (Italy). Epidemiol. Prev. 44 (2-3), 137–144. doi:10.19191/EP20.2-3.P137.036

FIDH (2018). The Environmental Disaster and Human Rights Violations of the ILVA Steel Plant in Italy. Available at: https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/industrieitaly711aweb-1.pdf. (Accessed June 28th, 2021).

Finn, S., and O’Fallon, L. (2017). The Emergence of Environmental Health Literacy-From its Roots to its Future Potential. Environ. Health Perspect. 125 (4), 495–501. doi:10.1289/ehp.1409337

Freedman, D. A., Bess, K. D., Tucker, H. A., Boyd, D. L., Tuchman, A. M., and Wallston, K. A. (2009). Public Health Literacy Defined. Am. J. Prev. Med. 36 (5), 446–451. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.001

Gray, K. (2018). From Content Knowledge to Community Change: A Review of Representations of Environmental Health Literacy. Ijerph 15 (3), 466. doi:10.3390/ijerph15030466

R. Holifield, J. Chakraborty, and G. Walker (2018). The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice. (New York: Taylor & Francis).

Hoover, E., Renauld, M., Edelstein, M. R., and Brown, P. (2015). Social Science Collaboration with Environmental Health. Environ. Health Perspect. 123 (11), 1100–1106. doi:10.1289/ehp.1409283

IARC (2017). Fluoro-edenite. in: IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Some Nanomaterials and Some Fibres, 111. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 215–242. Available at: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Monographs-On-The-Identification-Of-Carcinogenic-Hazards-To-Humans/Some-Nanomaterials-And-Some-Fibres-2017 (Accessed June 28th, 2021).

Iavarone, I., and Martuzzi, M. (2019). COST Action Industrially Contaminated Sites and Health Network ICSHNet. Joint COST Action and WHO Report Guidance Document on Industrially Contaminated Sites and Health Impacts. online. Available at: http://www.icshnet.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/WHO-COST-Action-Guidance-Document.pdf (Accessed December 4th, 2020).

Iavarone, I., Pirastu, R., Minelli, G., and Comba, P. (2013). Children's Health in Italian Polluted Sites. Epidemiol. Prev. 37 (1 Suppl. 1), 255–260. English, Italian. PMID: 23585448.

Iavarone, I., Buzzoni, C., Stoppa, G., and Steliarova-Foucher, E. (2018). Cancer Incidence in Children and Young Adults Living in Industrially Contaminated Sites: from the Italian Experience to the Development of an International Surveillance System. Epidemiol. Prev. 42 (5-6S1), 76–85. SENTIERI-AIRTUM Working Group. doi:10.19191/EP18.5-6.S1.P076.090

ICSHNet (2019). COST Action Industrially Contaminated Sites and Health Network. Final Plenary Conference COSTO Action Industrially Contaminated Sites and Health Network (ICSHNet). Available at: http://www.icshnet.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Programme_-Final_COST_Action_Conference.pdfì. (Accessed June 28th, 2021).

Landrigan, P. J., Rauh, V. A., and Galvez, M. P. (2010). Environmental Justice and the Health of Children. Mt Sinai J. Med. 77 (2), 178–187. doi:10.1002/msj.20173

Marsili, D., Comba, P., and De Castro, P. (2015). Environmental Health Literacy within the Italian Asbestos Project: Experience in Italy and Latin American Contexts. Commentary. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 51 (3), 180–182. doi:10.4415/ANN_15_03_02

Marsili, D., Fazzo, L., Iavarone, I., and Comba, P. (2017). Communication Plans in Contaminated Areas as Prevention Tools for Informed Policy, online. Public Health Panor 3 (2), 261–267. Available at:http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/341543/8_PolicyPractice_CommunicationPlans_ENG.pdf?ua=1. (Accessed November 5th, 2020).

Marsili, D., Magnani, C., Canepa, A., Bruno, C., Luberto, F., Caputo, A., et al. (2019a). Communication and Health Education in Communities Experiencing Asbestos Risk and Health Impacts in Italy. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 55 (1), 70–79. doi:10.4415/ANN_19_01_14

Marsili, D., Battifoglia, E., Bisceglia, L., Fazzo, L., Forti, M., Iavarone, I., et al. (2019b). “La Comunicazione Nei Siti Contaminate [Communication in Contaminated Sites],” in SENTIERI: Epidemiological Study of Residents in National Priority Contaminated Sites. Fifth Report (Italian: Epidemiol Prev), 43, 2-3 Suppl. 1, 1–208. pp198-205. doi:10.19191/EP19.2-3.S1.032

Marsili, D., Canepa, A., Mossone, N., and Comba, P. (2019c). Environmental Health Education for Asbestos-Contaminated Communities in Italy: The Casale Monferrato Case Study. Ann. Glob. Health 85 (1), 84. doi:10.5334/aogh.2491

Mudu, P., Terracini, B., and Martuzzi, M. (2014). Human Health In Areas with Industrial Contamination. WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark. online. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/264813/Human-Health-in-Areas-with-Industrial-Contamination-Eng.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed January 20, 2020).

NIEHS (2021). National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Kids Environment Kids Health. Environmental & Health. Available at: https://kids.niehs.nih.gov/topics/environment-health/index.htm (Accessed June 28th, 2021).

Nutbeam, D. (2000). Health Literacy as a Public Health Goal: a challenge for Contemporary Health Education and Communication Strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 15 (3), 259–267. doi:10.1093/heapro/15.310.1093/heapro/15.3.259

Nutbeam, D. (2008). The Evolving Concept of Health Literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 67 (12), 2072–2078. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050

Pasetto, R., and Fabri, A. (2020). Environmental justice nei siti industriali contaminati: documentare le disuguaglianze e definire gli interventi. Rome, Italy: Rapporti ISTISAN 20/21 Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Environmental justice in industrially contaminated industrial sites: documenting inequalities and defining interventions. Available online at: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/0/20-21+web.pdf/1dcc3560-b97d-9d75-5155-e0f0a79b6f1f?t=1605515556122. (Accessed January 9th, 2021).

Pasetto, R., and Iavarone, I. (2020). “Environmental Justice in Industrially Contaminated Sites. From the Development of a National Surveillance System to the Birth of an International Network,” online in Toxic Truths: Environmental justice and Citizen Science in a post-truth Age. Editors A. Mah, and T. Davis. 1st ed. (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press), 199–219. Available at: https://www.manchesteropenhive.com/view/9781526137005/9781526137005.00023.xml. (Accessed December 7th, 2020).

Pasetto, R., Zengarini, N., Caranci, N., De Santis, M., Minichilli, F., and Santoro, M. (2017). Environmental justice nel sistema di sorveglianza epidemiologica SENTIERI [Environmental justice in SENTTIERi epidemiological surveillance system]. Epidemiol. Prev. 41 (2), 134–139. Available online at: https://www.epiprev.it/materiali/2017/EP2/EP2_134_int1.pdf (Accessed January 8th, 2020). doi:10.19191/EP17.2.P134.033

Pasetto, R., Mattioli, B., and Marsili, D. (2019). Environmental Justice in Industrially Contaminated Sites. A Review of Scientific Evidence in the WHO European Region. Ijerph 16 (6), pii, 998. doi:10.3390/ijerph16060998

Pasetto, R., Marsili, D., Rosignoli, F., Bisceglia, L., Caranci, N., Fabri, A., et al. (2020). Environmental justice Promotion in Industrially Contaminated Sites. Epidemiol. Prev. 44 (5-6), In. Sep-Dec. doi:10.19191/EP20.5-6.A001

Pirastu, R., Iavarone, I., Pasetto, R., Zona, A., and Comba, P. (2011). SENTIERI: Risultati [SENTIERI Project: Mortality Study of Residents in Italian Polluted Sites – Results]. Epidemiol. Prev. 35 (4), 1–204.

Pirastu, R., Pasetto, R., Zona, A., Ancona, C., Iavarone, I., Martuzzi, M., et al. (2013a). The Health Profile of Populations Living in Contaminated Sites: SENTIERI Approach. J. Environ. Public Health 2013, 1–13. doi:10.1155/2013/939267

Pirastu, R., Comba, P., Iavarone, I., Zona, A., Conti, S., Minelli, G., et al. (2013b). Environment and Health in Contaminated Sites: The Case of Taranto, Italy. J. Environ. Public Health 2013, 1–20. doi:10.1155/2013/753719

Ramírez, A. S., Ramondt, S., Van Bogart, K., and Perez-Zuniga, R. (2019). Public Awareness of Air Pollution and Health Threats: Challenges and Opportunities for Communication Strategies to Improve Environmental Health Literacy. J. Health Commun. 24 (1), 75–83. doi:10.1080/10810730.2019.1574320

Ramirez-Andreotta, M. D., Brusseau, M. L., Artiola, J. F., Maier, R. M., and Gandolfi, A. J. (2014). Environmental Research Translation: Enhancing Interactions with Communities at Contaminated Sites. Sci. Total Environ. 497-498 (0), 651–664. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.08.021

SardegnaSalute, (2021a). Website. Salute e Ambiente a Porto Torres. Available at: https://www.sardegnasalute.it/index.php?xsl=316&s=9&v=9&c=94516&na=1&n=10. (Accessed July 8, 2021).

SardegnaSalute, (2021b). Website. Salute e Ambiente a Porto Torres. Mappa e glossario. Available at https://www.sardegnasalute.it/index.php?xsl=316&s=9&v=9&c=94731&na=1&n=10. (Accessed July 8, 2021).

Santoro, M., Minichilli, F., Pierini, A., Astolfi, G., Bisceglia, L., Carbone, P., et al. (2017). Congenital Anomalies in Contaminated Sites: A Multisite Study in Italy. Ijerph 14 (3), 292. PMCID: PMC5369128. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030292

Sentieri-ReNaM, G. L. (2016). SENTIERI - Epidemiological Study of Residents in National Priority Contaminated Sites: Incidence of Mesothelioma. Epidemiol. Prev. 40 (5Suppl. 1), 1–116. doi:10.19191/EP16.5S1.P001.097

Sicilia, Regione, (2013). Piano straordinario di interventi sanitari nelle aree a rischio ambientale della Sicilia. Deliberazione n. 327 del 26 settembre 2013. Available at: http://pti.regione.sicilia.it/portal/page/portal/PIR_PORTALE/PIR_LaStrutturaRegionale/PIR_AssessoratoSalute/PIR_AreeTematiche/PIR_Epidemiologia/PIR_RISCHIOAMBIENTALE/Delibera_3136.pdf. (Accessed June 28th, 2021).

Sicilia, Regione. (2015).Piano straordinario di interventi sanitari nel SIN di Biancavilla. Decreto Attuativo n. 830 del 18 maggio 2015. Available at: http://pti.regione.sicilia.it/portal/page/portal/PIR_PORTALE/PIR_LaStrutturaRegionale/PIR_AssessoratoSalute/PIR_Infoedocumenti/PIR_DecretiAssessratoSalute/PIR_Decreti/PIR_Decreti2015/PIR_Decretiassessorialianno2015/18%2005%202015%20SERV%207%20(830).pdf. (Accessed June 28th, 2021).

Sørensen, K., Van den Broucke, S., Van den Broucke, S., Fullam, J., Doyle, G., Pelikan, J., et al. (2012). Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models. BMC Public Health 12, 8. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-8010.1186/1471-2458-12-80

Solar, O., and Irwin, A. (2010). A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion. Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). CSDH-WHO: Ginevra, Switzerland. online. Available at: https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf (Accessed on January 18th, 2021).

Tan, N. Q. P., and Cho, H. (2019). Cultural Appropriateness in Health Communication: A Review and A Revised Framework. J. Health Commun. 24 (5), 492–502. doi:10.1080/10810730.2019.1620382

White, B. M., Hall, E. S., Johnson, C., Hall, E. S., and Johnson, C. (2014). Environmental Health Literacy in Support of Social Action: An Environmental Justice Perspective. J. Environ. Health 77, 24–29. F020. Jul-AugPMID: 25185324.

Wilson, S. M. (2009). An Ecologic Framework to Study and Address Environmental Justice and Community Health Issues. Environ. Justice 2 (1), 23. doi:10.1089/env.2008.051515

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2010). Environment and Health Risks: a Review of the Influence and Effects of Social Inequalities. online. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/78069/E93670.pdf. (Accessed December 17th, 2020).

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, (2012). Health Literacy. The Solid Facts. World Health Organization: Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. online. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128703/e96854.pdf. (Accessed December 15th, 2020).

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2017). Declaration Of the Sixth Ministerial Conference On Environment And Health. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. online. Copenhagen, Denmark. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/events/events/2017/06/sixth-ministerial-conference-on-environment-andhealth/documentation/declaration-of-thesixth-ministerial-conference-on-environment-and-health. (Accessed December 4th, 2020).

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2019a). Environmental Health Inequalities in Europe. Second Assessment Report. online. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/environmental-health-inequalities-in-europe.-second-assessment-report-2019. (Accessed December 4th, 2020).

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2019b). Environmental Health Inequalities Resource Package. A Tool for Understanding and Reducing Inequalities in Environmental Risk. online. Copenhagen, Denmark. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/420543/WHO-EH-inequalities-resource-package.pdf. (Accessed December 16th, 2020).

World Health Organization (2017a). Promoting Health in the SDGs. Report on the 9th Global Conference for Health Promotion, Shanghai, China, 21–24 November 2016: All for Health, Health for All. online. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-PND-17.5. (Accessed December 1st, 2020).

World Health Organization (2017b). Inheriting a Sustainable World? Atlas on Children’s Health and the Environment. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Licence: CCBY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/inheriting-a-sustainable-world. (Accessed December 4th, 2020).

World Health Organization (2018). Air Pollution and Child Health: Prescribing Clean Air. Summary. Geneva: World Health Organization. (WHO/CED/PHE/18.01). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/air-pollution-and-child-health. (Accessed 28th, June 2021).

Zarcadoolas, C., Pleasant, A., and Greer, D. S. (2005). Understanding Health Literacy: an Expanded Model. Health Promot. Int. 20 (2), 195–203. doi:10.1093/heapro/dah609

Zona, A., and Bruno, C. (2009). Health Surveillance for Subjects with Past Exposure to Asbestos: from International Experience and Italian Regional Practices to a Proposed Operational Model. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 45 (2), 147–161. PMID: 19636166. doi:10.1590/s0021-25712009000400017

Zona, A., Bruno, C., Villari, C., Contiguglia, R., Fazzo, L., Mollica, G., et al. (2010). Health Surveillance for Subjects with Past Occupational Exposure to Asbestos: the Experience of Local Health Unit Messina 5 (Sicily). Epidemiol. Prev. 34 (3), 94–99. PMID: 20852346.

Keywords: environmental health literacy, contaminated sites, communication strategies, epidemiological surveillance, community capacity, environmental health equity, environmental justice

Citation: Marsili D, Pasetto R, Iavarone I, Fazzo L, Zona A and Comba P (2021) Fostering Environmental Health Literacy in Contaminated Sites: National and Local Experience in Italy From a Public Health and Equity Perspective. Front. Commun. 6:697547. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.697547

Received: 19 April 2021; Accepted: 12 August 2021;

Published: 16 September 2021.

Edited by:

Victoria Team, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Aminata Kilungo, University of Arizona, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Marsili, Pasetto, Iavarone, Fazzo, Zona and Comba. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela Marsili, ZGFuaWVsYS5tYXJzaWxpQGlzcy5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.