- Department of Sociology and Criminology & Law, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States

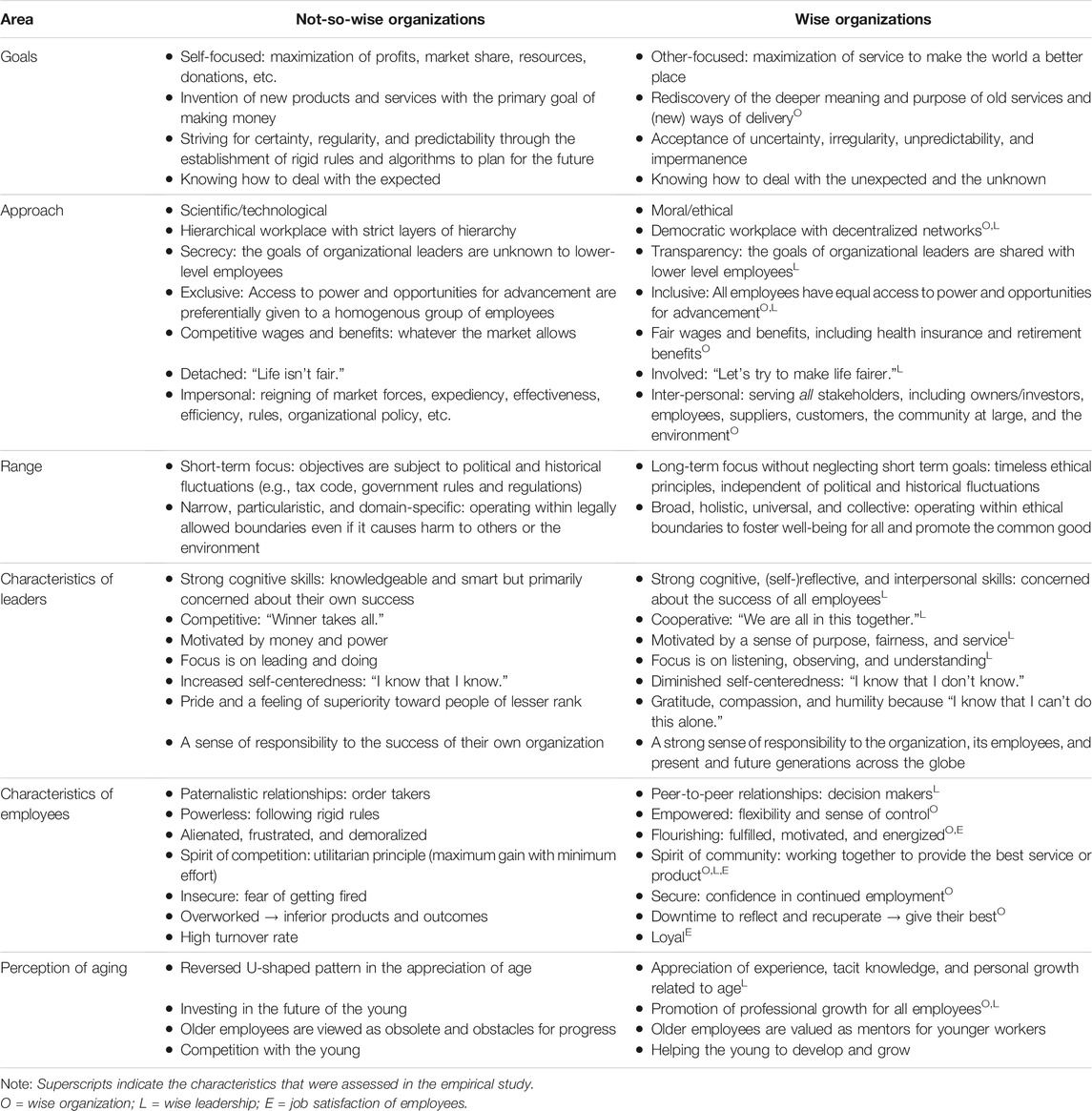

Objective: Research shows that wisdom benefits individuals, but is this also true for organizations? To answer this question, we first delineated the characteristics of wise and not-so-wise organizations in the areas of goals, approach, range, characteristics of leaders and employees, and perception of aging, using a framework derived from comparing wisdom with intellectual knowledge. Guided by this framework, we then tested whether wise organizations have a positive effect on employees’ physical and subjective well-being mediated by wise leadership and job satisfaction.

Method: We created a wise organization index for nine organizations from the 2007–2008 Age and Generations Study based on 74 to 390 average employees’ ratings of perceived work opportunities for training and development, flexibility at work, absence of time pressure at work, work-life balance, satisfaction with work benefits, job security, and job opportunities. A mediated path model was analyzed to test the hypothesis. The sample contained 821 employees (age range 19–74 years; M = 41.98, SD = 12.26) with valid values on wise (fair and supportive) leadership at the first wave of data collection and employee job satisfaction (career as calling, satisfaction with career progress, engagement at work, and organizational commitment) and physical and subjective well-being at the second wave of data collection at least 6 months later.

Findings: Results confirmed that the positive associations between the organizations’ overall wisdom index and employees’ physical and subjective well-being scores at Wave 2 was mediated by employees’ perception of wise leadership at Wave 1 and employee job satisfaction at Wave 2.

Originality/value: This study fills a gap in the organizational wisdom literature by 1) systematically contrasting the characteristics of wise organizations with not-so-wise organizations, 2) creating a novel wise organization index, and 3) testing the effects of wise organizations and wise leadership on employees’ job satisfaction and physical and subjective well-being.

Practical and societal implications: The results suggest that wise organizations encourage wise leadership, and wise leadership, in turn, fosters job satisfaction, which benefits employees’ physical and subjective well-being. Hence, wise organizations ultimately enhance workers’ well-being, which likely contributes to the success and reputation of the organization through higher employee productivity and better customer service.

Introduction

Wisdom has been considered the pinnacle of human development, orchestrating mind and virtue toward excellence (Baltes and Staudinger, 2000), but is this also true for organizations? According to Aristotle, practical wisdom (phronesis) is a master virtue that guides all the other virtues (Schwartz and Sharpe, 2006; Fowers, 2008; Swartwood and Tiberius, 2019). Yet, it is still not completely clear what wisdom is. For the ancient Greeks, practical wisdom implied knowing how to resist the desires of the passions and the deception of the senses so that one could live and conduct oneself based on a deep understanding of the most important things in life (Robinson, 1990; Swartwood and Tiberius, 2019). In contemporary wisdom research, several definitions of wisdom have been proposed, ranging from general wisdom-related knowledge in the fundamental pragmatics of life related to life planning, life management, and life review to self-transcendence (for an overview of the diverse wisdom definitions see Sternberg and Glück, 2019). After a review of the scientific wisdom literature, Meeks and Jeste (2009) and Bangen et al. (2013) summarized the common features of wisdom definitions as 1) prosocial attitudes/behaviors and values, 2) social decision making/pragmatic knowledge of life, 3) emotional homeostasis, 4) reflection/self-understanding, 5) value relativism/tolerance, and 6) acknowledgement of and dealing with uncertainty/ambiguity. Based on these definitions, a group of leading wisdom researchers suggested an overarching definition of wisdom as morally grounded excellence in social-cognitive processing, which includes the pursuit of truth with an awareness of the limitations of knowledge, a contextual balance of self- and other-oriented interests through reflection and perspective-taking, and an orientation toward the common good (Grossmann et al., 2020).

Our definition and conceptualization of wisdom as an integration of cognitive, reflective, and affective/compassionate dimensions is similar to morally grounded excellence in social-cognitive processing and compatible with Aristotle’s concept of practical wisdom but places greater emphasis on compassionate attitudes and behavior (Ardelt, 2003; 2004). The Three-Dimensional Wisdom Model was derived from a multi-dimensional scaling analysis by Clayton and Birren (1980) based on ratings of several wisdom descriptors by young, middle-aged, and older adults. The wisdom descriptors had been generated in an earlier study by another sample of young, middle-aged, and older adults. The cognitive dimension of wisdom encompasses the search for a deeper truth related to the intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects of life. It is concerned with existential questions about the deeper meaning of life and one’s role in the greater scheme of existence. To reach this kind of insight and understanding requires the reflective dimension of wisdom, which is the perception of phenomena and events from multiple perspectives to overcome self-centered tendencies of blaming other people or circumstances for one’s own shortcomings. Perspective-taking and a reduction in self-centeredness not only deepen insight into the true nature of things, including an awareness and acceptance of the limitations of knowledge, but also increase tolerance and understanding of other people’s behavior and shortcomings, which lead to the affective/compassionate dimension of wisdom, defined as sympathetic and compassionate love for others that manifests in prosocial behavior. All three dimensions are intertwined and reinforce each other. The Three-Dimensional Wisdom Model has the advantage of being relatively parsimonious while comprising the essential elements of wisdom as expressed in both expert and lay persons’ wisdom definitions in western and eastern cultures (Meeks and Jeste, 2009; Bangen et al., 2013; Weststrate et al., 2019; Ardelt et al., 2020).

We propose that the integration of cognitive, reflective, and compassionate personality characteristics will prompt an individual to act in a moral and ethical manner. As Aristotle (1998) remarked, “it is not possible to be good in the strict sense without practical wisdom, nor practically wise without moral virtue.” Wise people who have a deeper understanding of themselves, other people, and the mechanisms of life know that immoral and unethical acts will not only hurt others but ultimately hurt themselves (Hart, 1987; Aldwin et al., 2019; Swartwood and Tiberius, 2019). This is the reason, why ethical and moral behavior has been suggested to foster eudaimonia, variously translated as fulfillment, flourishing, or psychological well-being (Fowers, 2008; Ryff, 2014).

Empirical evidence confirms that wisdom is positively correlated to indicators of ethical attitudes and behavior, such as moral reasoning (Pasupathi and Staudinger, 2001), other-enhancing values (Kunzmann and Baltes, 2003; Webster, 2010), benevolence (Helson and Srivastava, 2002), empathy and emotional competence regarding others (Glück et al., 2013), forgiveness (Taylor et al., 2011), and humility (Krause, 2016). Among employees, wisdom is positively associated with ethical attitudes and the rejection of questionable business practices that are harmful to others and the environment (Oden et al., 2015). Wisdom also correlates positively with indicators of eudaimonia, such as ego integrity (Webster, 2003; Webster, 2007), ego development (Mickler and Staudinger, 2008), purpose in life, mastery, self-acceptance, positive relations with others, and autonomy (Helson and Srivastava, 2002; Ardelt, 2003; Kunzmann and Baltes, 2003; Wink and Dillon, 2003; Webster, 2007; Ardelt, 2011; Etezadi and Pushkar, 2013; Glück et al., 2013; Webster et al., 2014; Ardelt and Edwards, 2016; Ardelt and Ferrari, 2019). Moreover, wisdom is related to greater subjective well-being and the absence of ill-being, such as depressive symptoms, depressive brooding, and negative affect (Ardelt, 1997; Takahashi and Overton, 2002; Ardelt, 2003; Kunzmann and Baltes, 2003; Ferrari et al., 2011; Le, 2011; Bergsma and Ardelt, 2012; Etezadi and Pushkar, 2013; Zacher et al., 2013; Webster et al., 2014; Ardelt and Edwards, 2016; Krause, 2016; Ardelt and Jeste, 2018; Ardelt and Ferrari, 2019).

The question remains, however, whether the characteristics of personal wisdom could also be applied and adapted to organizations to re-humanize the workplace. If they can, wise organizations might benefit their employees and the common good through wise and ethical leadership (Limas and Hansson, 2004; Rowley and Gibbs, 2008; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011; McKenna and Rooney, 2019; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019; Kristjánsson, 2021 online first). Because organizations are social systems that consist of interrelated groups of people with distinct but interdependent duties based on fixed rules and procedures (Johnson, 2000; Marrett, 2001), a shift toward wiser rules and procedures by the organization’s leadership likely has beneficial ripple effects throughout the organization.

The goals of this article are threefold: First, we delineate the characteristics of wise organizations in contrast to not-so-wise organizations, using a framework derived from contrasting wisdom with intellectual knowledge (Ardelt, 2000). Second, guided by the distinction between wise and not-so-wise organizations, we conducted a secondary data analysis of the Age and Generations Study (Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer, 2013) to create a wise organization index and, third, empirically test the effects of wise organizations on perceptions of wise leadership and employees’ work-related and personal well-being, using a mediated path analysis model. Although the characteristics of organizational wisdom and wise leadership have been discussed in the literature, the majority of these contributions were theoretical rather than empirical (Kriger and Malan, 1993; Malan and Kriger, 1998; Srivastva and Cooperrider, 1998; Bierly et al., 2000; Rowley, 2006a; Rowley, 2006b; Kessler and Bailey, 2007; Nonaka and Toyama, 2007; Hays, 2008; Rooney and McKenna, 2008; Rowley and Gibbs, 2008; McKenna et al., 2009; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011; Ekmekçi et al., 2014; Intezari and Pauleen, 2014; Nonaka et al., 2014; Mora Cortez and Johnston, 2019; Kristjánsson, 2021 online first) or studied other aspects than employee well-being, such as improvements in organizational efficiency and effectiveness (Pinheiro et al., 2012), wise management decision-making (Intezari and Pauleen, 2018), characteristics of wise leaders (Yang, 2011), the desirability of wise leadership to organizational culture (Limas and Hansson, 2004), and workplace spirituality (Zaidman and Goldstein-Gidoni, 2011). Moreover, past definitions of organizational wisdom have been primarily focused on comprehensive knowledge and intelligence (Limas and Hansson, 2004; Hays, 2008; Pinheiro et al., 2012; Mora Cortez and Johnston, 2019) but neglected the compassionate, pro-social aspects of wisdom. Our study aims to fill a gap in the organizational wisdom literature by 1) systematically contrasting the characteristics of wise organizations with not-so-wise organizations in six areas, 2) creating a novel wise organization index, and 3) investigating whether wise organizations have a salutary impact on employees’ work-related and personal well-being mediated by wise leadership. If this is the case, wise organizations might not only benefit their employees but also themselves in the long-term through more engaged, committed, and productive employees (Bhatti and Qureshi, 2007; Halkos and Bousinakis, 2010; Fassoulis and Alexopoulos, 2015; Giolito et al., 2020).

Characteristics of Wise Organizations in Contrast to Not-So-Wise Organizations

We propose that the Three-Dimensional Wisdom Model is not only relevant for individuals but also for organizations. The cognitive wisdom dimension manifests in individuals as a search for knowledge about the deeper meaning of life and how best to live one’s life. Similarly, the cognitive dimension in wise organizations is represented by a search for the organization’s deeper meaning and purpose and a culture that fosters learning and professional development to adapt to changing circumstances and solve complex problems (Howard, 2010; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019). As in personal wisdom, the reflective wisdom dimension means that the organizational culture of wise organizations encourages perspective-taking and open-mindedness, which promotes understanding, respect, tolerance, and patience among employees and between employees and customers (Malan and Kriger, 1998; Small, 2004). Perspective-taking by the organization’s leadership results in the realization that the long-term success and survival of an organization depends on treating its workers as autonomous human beings rather than robots and providing products or services that are beneficial for all stakeholders, including consumers, clients, shareholders, employees, the community, and the environment. Hence, perspective taking leads to the affective/compassionate dimension of wisdom, which is the insight that the ultimate goal and purpose of a wise organization is the promotion of the common good for all stakeholders over the short-term and also the long-term by balancing wisdom with intelligence and creativity (Sternberg, 2003; Sternberg, 2007; Ekmekçi et al., 2014; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019; Sternberg, 2019; Sternberg, 2020). The sympathy and compassion that characterizes the affective/compassionate dimension in personal wisdom is expressed in organizational wisdom through a culture that promotes the common good for all stakeholder to make the world a better place and supportive and compassionate interpersonal relationships at work (Frost et al., 2000).

We adapted a framework that compared the characteristics of personal wisdom or applied wisdom-related knowledge with theoretical intellectual knowledge in the domains of goals, approach, range, acquisition, effects on the knower, and relation to aging (Ardelt, 2000; Ardelt, 2008) to describe the characteristics of wise organizations in contrast to not-so-wise organizations in the areas of goals, approach, range, characteristics of leaders and employees, and the perception of aging (see Table 1). The characteristics of wise and not-so-wise organizations, adapted from comparing the characteristics of wisdom and intellectual knowledge based on the Three-Dimensional Wisdom Model, are introduced as “ideal types” in Max Weber’s (1980) sense rather than descriptions of real organizations (Psathas, 2005; Clegg, 2017). Therefore, when providing examples to illustrate aspects of wise and not-so-wise organizations, we do not mean to imply that these organizations necessarily possess all other characteristics of these “ideal types” as well. Most organizations consist of a mixture of wise and not-so-wise organizational characteristics. However, by applying the “ideal type” approach, it is possible to assess where an organization exists on the not-so-wise to wise continuum. Organizations that have many characteristics of wise organizations would be considered wiser than organizations whose characteristics are closer to the not-so-wise organization type.

Goals

For decades, scholars in the field of business and management primarily studied the characteristics of successfully competitive organizations. Porter and Kramer (2006) criticized this one-sided attention to the profitability, processes, and outcomes of organizations and instead urged corporations to evaluate the social impact of corporate activities and pay attention to the beneficiaries of successful outcomes. Whereas not-so-wise organizations strive to attain self-focused goals, such as the maximization of profits, market share, resources, donations, etc., the ultimate goal of wise organizations is an other-focused maximization of service to make the world a better place (Nonaka and Toyama, 2007; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011; Spiller et al., 2011; Hart and Zingales, 2017; Aldwin and Levenson, 2019; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019). For example, the manufacturing company SC Johnson’s motto is “We’re SC Johnson. A family company at work for a better world™.”1 The company, which makes products for home cleaning and storage, personal care, and insect control, has implemented one of the most rigorous manufacturing systems in the world to meet its commitment towards global sustainability goals and zero manufacturing waste to landfill from its factories by 2021 (SC Johnson, 2017; Noria News Wires, 2021). Yet, SC Johnson is not only an environmentally aware company but has also been consistently recognized as a great place to work across several countries, such as Forbes’ list of America’s Best Large Employers (Stoller, 2021). Another example is the successful Māori economy in New Zealand, which is guided by kaitiakitanga, an ethic of stewardship, care, and compassion, to consciously create well-being for all. Kaitiakitanga recognizes the interconnectedness of all life, which makes it impossible for Māori organizations to pursue self-interested goals that harm others or the environment. Rather, the Māori economy is based on mutually beneficial relationships that take the well-being of all stakeholders into account (Spiller et al., 2011).

Although the products or services that wise and not-so-wise organizations offer might appear to be the same on the surface, the underlying goals are different. For example, universities might introduce online teaching with the goal of delivering educational opportunities to students who would not have had otherwise access or simply to earn extra tuition and fees. Healthcare organizations’ aim might be to heal people, alleviate their pain and suffering, and keep them well or to price their services for maximum profit (Schwartz and Sharpe, 2019a; Kaldjian, 2019). Non-profit organizations might focus on fulfilling their non-profit mission or on receiving donations and paying the salary of their executives. Companies might develop new products (e.g., new prescription drugs or vaccines) to relieve suffering or simply to earn a greater profit.

Moreover, if not-so-wise organizations invent new products and services with the primary goal of making money rather than improving people’s lives, they might ignore the consequences of their inventions and offer products that are harmful and hurt consumers, such as e-cigarettes and addictive prescription opioids. By contrast, wise organizations strive to rediscover the deeper meaning and purpose of old services, such as the importance of personal customer care, and re-imagine new ways of delivery (Howard, 2010). For example, the Lemon Tree Hotel chain in India has taken hospitality services to a new level by hiring “opportunity-deprived” people, such as hearing-impaired persons, as a key part of its workforce (Goyal, 2017; Kazmin, 2018). This initiative not only improves the prospects of workers who often face discrimination in the labor market but benefits the business too. The differently abled workers have a lower attrition rate, are often more focused on customer service, and tend to be more productive than their peers. In addition, other workers feel a sense of pride in the organization, which increases morale, and the hotels receive many positive reviews from customers.

Wise organizations accept uncertainty, irregularity, unpredictability, and impermanence and, therefore, can abandon rigid rules when the need arises to deal with the unexpected and the unknown (Intezari and Pauleen, 2014; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). Ongoing improvements for the common good and being nimble in highly dynamic and complex environments are critical attributes of a wise organizations (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019). For example, the clothing and gear company Patagonia reduces its environmental footprint by using renewable electricity and recycled materials.2 Moreover, it started its own resale platform, Worn Wear, where customers can repair, trade-in, and recycle their used Patagonia garments to keep them out of the landfill and save environmental resources (Barkho, 2020).3 During the COVID-19 pandemic, some organizations repurposed their manufacturing to make urgently needed medical equipment instead of fashion clothes and cars, which kept their business financially sustainable while saving lives (Robinson, 2020). Wise organizations are aware of their constraints and constantly strive to mitigate them (Goldratt, 1997). The goal is not to save money but to make money to sustain the health of the organization and finance improvements to make the world a better place. Goldratt and Cox’s (1992) Theory of Constraints consists of a process to identify the most important constraint that becomes an obstacle in achieving a goal. Once the constraint is identified, a wise organization engages in systematic improvement processes until the limiting factor is removed.

By contrast, not-so-wise organizations strive for certainty, regularity, and predictability through the establishment of rigid rules and algorithms to plan for the future. While rigid and established rules and algorithms might help companies to deal with the expected, they fail when the world changes (Nonaka and Toyama, 2007; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019). For example, the automobile brand Porsche used to have an exceptional reputation for its technically superior world-class engineering skills. For several decades, Porsche could command premium prices based on its brand strength. The company, however, neglected the slow but systematic erosion of its unique competitive advantage and underestimated Japanese competitors in the 1990s, which offered sport cars at much more affordable pricing. As a result, Porsche’s sales in North America dropped from 30,471 units in 1986 to 3,713 units in 19934 (Hamel and Prahalad, 1994). The turnaround only came after a new CEO drastically changed how cars were manufactured at Porsche. The company collaborated with Japanese auto manufacturers to introduce just-in-time lean manufacturing, which improved internal efficiency and drastically cut costs (Nash, 1996). While wiser companies do not lose sight of their ultimate goal to make the world a better place, they also strive to stay competitive, because they know that they have an ethical resposibility toward their employees, suppliers, loyal customers, and shareholders to stay in business.

Approach

Organizational culture reflects the fundamental “approach” of organizations (Lund, 2003; Ginevičius and Vaitkūnaite, 2006; Aydin and Ceylan, 2009). One characteristic of a wise organization is a culture of moral and ethical values that encourages moral and ethical behavior (French, 1979; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011; Intezari and Pauleen, 2014; Kristjánsson, 2021 online first). Whereas not-so-wise organizations follow a strictly scientific/technological approach, wise organizations emphasize authentic moral and ethical values that are propagated, supported, and modeled by leaders and supervisors (Sinclair, 1993; Boal and Hooijberg, 2000; Rooney and McKenna, 2005; McKenna et al., 2009; Toor and Ofori, 2009; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019; Rooney et al., 2021). For example, technological algorithms of many social media companies are used to keep people engaged and entice them to spend more time on their platforms, irrespective of the veracity of the content that is offered or the damage it might do to social relationships, the political system, or democracy in general. By contrast, a wise organization would favor truth over advertising income.

Because not-so-wise organizations emphasize planning and predictability, they attempt to control their stakeholders, including employees and customers. Such organizations build hierarchical workplaces with strict layers of hierarchy to closely control employees and their work outputs through rules, regulations, policies, and procedures (Lund, 2003). The goals of organizational leaders are often unknown to lower-level employees. Not-so-wise organizations might also suffer from a culture of nepotism that provides preferential treatment to a homogeneous group of employees (e.g., the “good-old-boy network”), both in terms of information and rewards (Ridgeway, 1997; Nelson, 2017). In addition, these organizations encourage internal and external competition among employees by creating competitive compensation and benefits structures (Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). Employees from the top to the bottom of the income structure are paid whatever the market and the law allow, even if the gap between leadership salaries and lower-income workers continues to spread and the full-time wages of lower-income workers might not be enough to make ends meet.5 A not-so-wise organization’s detached motto is “Life isn’t fair, so either accept it or move on.” Not-so-wise organizations are ruled by impersonal market forces that give priority to expediency, effectiveness, efficiency, rules, organizational policy, billing hours, sales volume, etc. rather than the people who are employed, served, or affected by the organization (Bennis, 1997). This means that immoral and unethical business practices and behavior, such as inhumane working conditions, the unethical treatment of animals, the manufacturing and distribution of unhealthy or addictive products, and environmental degradation, are ignored or even condoned as long as they result in great profits (Hart and Zingales, 2017).

In contrast, wise organizations are fair and democratic workplaces with decentralized networks (Schwartz and Sharpe, 2019a). This approach fosters transparency within the organization wherein the goals of organizational leaders are shared with lower-level employees who are invited to provide feed-back and input, either through organized labor or some other mechanism (e.g., an open door or email policy with the leadership). Such organizations strive to create inclusive structures and processes so that all employees have equal access to power and opportunities for advancement, irrespective of gender, age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation or identity, or other-abled bodies. Wise organizations pay fair wages and benefits, including health insurance and retirement benefits, and provide working conditions that allow a work-life balance (Greenberg and Baron, 2003). For example, Ben and Jerry’s commitment to economic justice is reflected in their livable wage initiative (Young, 2021), which offers workers a livable wage that is significantly higher than the national minimum wage and recalculated every year based on the actual cost of living in Vermont.6

A wise organization’s involved motto is “Life might not be fair; let’s try to make it fairer.” In contrast to the impersonal approach of not-so-wise organizations, the approach of wise organizations is inter-personal and relational. They serve and balance the interests of all stakeholder, including owners/investors, employees, suppliers, customers, the community at large, and the environment, by focusing on long-term success for the common good (Bierly et al., 2000; Rowley and Gibbs, 2008; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011; Spiller et al., 2011; Intezari and Pauleen, 2014; McKenna and Rooney, 2019; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). By collaborating with other groups and organizations, wise organizations are more likely to achieve these goals (Sternberg, 2007). For example, The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) is an international movement of people and organizations with the goal of prioritizing people and the planet before profits.7 ECG has developed a Common Good Matrix to assess an organization’s impact on all stakeholders with regard to human dignity, solidarity and social justice, environmental sustainability, and transparency and co-determination. The idea is to assign organizations points for meeting these goals and their products a Common Good score so that customers can make informed decisions about the products they buy. Societies that want to support ECG might offer lower taxes and other business incentives to organizations with higher Common Good scores. Similarly, B (“Benefit”) Corporations, another international movement that balances purpose and profit, use their business as a force for good by taking the interests of all stakeholders into account, while still striving to earn a profit.8

An example of a B Corporation is Greyston Bakery. This large and successful company does not ask for a resume, a working history, or even a skillset of job applicants but gives everyone a chance to work at their company, including people often considered “unemployable,” such as ex-convicts, addicts, and other-abled, unhoused, and illiterate persons (Chhabra, 2018). Greyston Bakery uses only quality ingredients without artificial preservatives, flavors, sweeteners, or hydrogenated fats to bake their signature brownies, benefiting customers. The company has a long collaborative relationship with Ben and Jerry’s, another B Corporation, to deliver the brownies that are used in Ben and Jerry’s Chocolate Fudge Brownie or Half-Baked™ ice cream flavors.9 In addition, Greyston provides workforce development and community wellness services to promote the professional and personal success of people in their community.10

Range

Not-so-wise organizations focus on short-term gains. Guided by self-interests, their objectives depend on the current laws, rules, and regulation, which are subject to political and historical fluctuations. The vision of a not-so-wise organization is narrow, particularistic, and domain-specific. Not-so-wise organizations operate within legally allowed boundaries of the tax code and government rules and regulations to earn as much profit as legally possible even if it causes harm to others or the environment.

By contrast, wise organizations focus on long-term success without neglecting short term goals (Sternberg, 2007; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019; Sternberg, 2020). Their modus operandi is based on timeless ethical principles, such as benevolence, fairness, justice, trust, integrity, and honesty, that are independent of political and historical fluctuations (Covey, 1991; Intezari and Pauleen, 2014). The vision of a wise organization is broad and holistic, taking the environmental and global impacts of its operations into account, and directed toward universal and collective goods to foster the well-being for all rather than only for the leaders and owners of the company (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011; Intezari and Pauleen, 2014; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019).

An example of conversion from a not-so-wise organization to a wiser organization is the carpet manufacturer Interface. Ray Anderson, the late CEO of Interface, began to change the company’s mission from a profit-only oriented carpet manufacturer that earned high revenues, while polluting and poisoning the environment, to a company with zero environmental impact that contributed to saving the planet without sacrificing economic success (Anderson and White, 2009; Schwartz and Sharpe, 2019b).

Characteristics of Leaders

Not-so-wise leaders might possess strong cognitive skills and be knowledgeable and smart, but they are primarily concerned about their own success rather than the well-being of their employees (Sternberg, 2005; Sternberg, 2018; Sternberg, 2020). Therefore, not-so-wise leaders have no misgivings about paying high salaries and bonuses to the leadership team while many of their lower-level employees struggle to make ends meet. The work environment is competitive with a “Winner takes all” attitude, and the leaders are primarily motivated by money and power (McKenna and Rooney, 2019).

Wise organizations, by contrast, have wise leaders with (self-)reflective and interpersonal skills in addition to knowledge and cognitive skills (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011; Intezari and Pauleen, 2018; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2019; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). Wise leaders might build wise organizations or be attracted to work in wise organizations, because wise individuals select their environment if they cannot shape or adapt to their current environment (Sternberg, 1998). Moreover, wise organizations are likely to promote and develop wise leaders through their internal organizational culture. Wise leaders strive to make good judgments and decisions that promote the success of all employees (McKenna and Rooney, 2019), because they know that “We are all in this together” (Spiller et al., 2011; Aldwin and Levenson, 2019). Wise leaders support others, unite people, and contribute toward human flourishing by bringing out the best in people, whereas foolish and toxic leaders do the opposite (Sternberg, 2005; 2018; 2020).

The felt support of a wise leader, in turn, increases employees’ commitment to the organization’s goals and success (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005). Wise and authentic leaders have high levels of self-awareness, self-knowledge, and self-reliability, are morally grounded, share information and appropriate feelings, and are motivated by a sense of purpose, fairness, and service (Avolio and Gardner, 2005; Avolio et al., 2009; McKenna et al., 2009; Yang, 2011; Hoch et al., 2018; McKenna and Rooney, 2019). More than technical knowledge and skills, wise leaders prioritize wise judgments and ethical principles (McKenna et al., 2009; Intezari and Pauleen, 2014). For example, in his 2015 annual letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett stated that his organization was not interested in an ego-driven leader who was motivated by excess pay. Instead, he wrote that “a Berkshire CEO must be “all in” for the company, not for himself” (McGregor, 2015). Yet, this “all in” should not come at the cost of ethical principles. Buffett emphasized that the character of the leader is crucial since “a CEO’s behavior has a huge impact on managers down the line” (McGregor, 2015). Wise leaders know how to bring out the best in people, while not-so-wise leaders focus on people’s self-centered interests to the detriment of a cooperative and supportive environment (Sternberg, 2018), such as creating sales competitions in businesses or teaching awards in colleges and universities where the “winner takes all,” while the positive contributions of all others remain unrewarded (Adam et al., 2007).

Self-centered not-so-wise leaders focus on leading and doing, because they believe they know that they know what the optimal course of action is without the input from others. This sense of omniscience, omnipotence, invulnerability, and self-assuredness in their own success (Sternberg, 2018; 2020) leads to pride and a feeling of superiority toward people of lesser rank who are considered not as intelligent, smart, and capable as themselves and, therefore, deserve the lower pay and benefits they receive.

Self-transcendent wise leaders, by contrast, know that they do not know everything (Intezari and Pauleen, 2014; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019) and are open to listen to others’ advice and suggestions, even if they are of lower rank, observe what is going on in their organization and the wider world, and try to understand others’ point of view (Limas and Hansson, 2004; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011). These leaders create a psychologically safe climate so that employees do not fear retaliation or ridicule if they voice dissent or make creative suggestions (Edmondson and Chamorro-Premuzic, 2020). Although wise leaders are intelligent and knowledgeable, they are also open, creative, honest, generous, grateful, compassionate, altruistic, caring, and humble (Bennis, 1997; Limas and Hansson, 2004; Hays, 2008; Sternberg, 2018; McKenna and Rooney, 2019), because they know that they cannot succeed by themselves without the support and cooperation of others (Edmondson and Chamorro-Premuzic, 2020). For example, in his 2015 annual letter to shareholders, Buffett remarked that leaders should be rational, calm, and decisive but also know their limits. They need to admit their mistakes, remain humble, and acknowledge and praise the contributions of others (McGregor, 2015).

Not-so-wise leaders’ sense of responsibility does not reach beyond the success of their own organization, while wise leaders feel a strong sense of responsibility not just for their own organization and its employees but also for present and future generations across the globe (Solomon et al., 2005; Rowley, 2006a; Aldwin and Levenson, 2019). For example, Emerson Electric’s motto is “Confidently protect your plant, personnel and community” by prioritizing safety first in all its plants and business operations.11 In addition to operating responsibly, Emerson invests in its employees through training and professional development opportunities for all employees, and it strengthens the surrounding communities through corporate philanthropy and employee volunteerism.12 An example of a wise leader who cared about the well-being of people across the globe is Roy Vagelos, the former president and CEO of the pharmaceutical company Merck. When scientists at Merck discovered a drug that could cure river blindness, a prevalent and crippling disease in sub-Saharan Africa, he decided to produce the drug and give it away for free to the countries that needed it most but could not afford to buy it. Although Merck’s profits suffered in the short-term by developing, producing, marketing, and distributing the drug for free, ultimately, the drug provided free positive advertising for Merck by curing over 55 million people of river blindness, which increased Merck’s profits in the long-term (Sternberg, 2020).

Characteristics of Employees

The wisdom of organizations and its leaders will inevitably affect its employees. In not-so-wise organizations employee relationships are hierarchical and paternalistic, with leaders who “know best” and lower-level employees who take and follow orders. Employees work according to rigid rules and job descriptions, which give them no opportunities to contribute their own ideas (Handy, 1997) and leaves them feeling powerless, alienated, frustrated, and demoralized. A spirit of competition reigns where employees work according to the utilitarian principle of maximum gain with minimal effort. In these organizations, rules and job descriptions determine the amount of effort employees are willing to exert.

In wise organizations, by contrast, employee relationships are characterized by democratic peer-to-peer relationships where employees are invited to contribute to the decision-making process and feel secure to offer constructive critiques and creative solutions to team members and leaders (Handy, 1997; Schwartz and Sharpe, 2019a; Edmondson and Chamorro-Premuzic, 2020). For example, a 2-year study at Google demonstrated that the most important factor for team success was feeling safe to contribute opinions, ideas, and solutions to the work team (Rozovsky, 2015). In these work environments, employees feel empowered to have some flexibility and control over how they perform their work, which leads to greater fulfillment and satisfaction at work (Spector, 2000). The sense of control given to workers depends more on the culture of the organization than the specific work tasks (Tata, 2000). For example, workers in auto manufacturing might do very repetitive tasks as part of the assembly line or be members of semi-autonomous work groups that provide the opportunity to engage in diverse and complex tasks and creative problem-solving (Woywode, 2002). Satisfied employees, in turn, tend to be more effective at work and trigger a positive flow of energy throughout an organization (Malik, 2013; Giolito et al., 2020).

Moreover, an organization whose ultimate goal is to promote the common good contributes to employee flourishing by motivating and energizing employees to collaborate in a spirit of community and provide the best service or product, which makes work both meaningful and fulfilling (Covey, 1991; Giolito et al., 2020). For example, after Anderson, the CEO of Interface, changed the goal of the company from manufacturing carpets to saving the planet while manufacturing carpets, employees’ commitment and motivation to help the company succeed increased, because their work had gained meaning by taking part in a greater mission (Anderson and White, 2009; Schwartz and Sharpe, 2019b).

Employees in wise organizations feel secure and confident in their continued employment, because the organizations have made an explicit commitment to their long-term employees. Wise organizations also understand the value of downtime for employees. They provide employees with enough time to reflect and recuperate from work so that employees can be more productive and able to give their best (Howard, 2010). Employees who are satisfied with their job, in turn, tend to be loyal to their organization (Aziri, 2011).

Not-so-wise organizations, by contrast, operate according to the “hire and fire” principle, which gives them greater flexibility but results in an insecure workforce that is under the constant threat of getting fired. Employees who are routinely required to work long shifts with few short breaks or an extended workweek to avoid getting fired or demoted without being given the necessary time to recuperate might experience burnout and deliver inferior products and services. Coupled with low autonomy at work, these jobs negatively affect employees’ mental health and increase the risk of mortality (Gonzalez-Mulé and Cockburn, 2017; Gonzalez-Mulé and Cockburn, 2021). In addition, overworked employees are more likely to leave the organization due to exhaustion and low job satisfaction (Aziri, 2011; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019).

Perception of Aging

While many organizations are aware of and try to combat racism and sexism in their organization through diversity training, ageism is often overlooked (Katerina et al., 2012; Kalinoski et al., 2013). In rapidly changing societies that are characterized by technological advances, the appreciation of employees’ work experience by age likely follows a reversed U-shaped pattern in not-so-wise organizations. These organizations might value younger employees with some work experience more than older employees who have been with the company for many years. Not-so-wise organizations invest in training for the younger members of their workforce but overlook their older employees. They believe that the knowledge and experience of older workers have become outdated and, therefore, older workers are viewed as obsolete and an obstacle for progress (Brooke and Taylor, 2005; Peterson and Spiker, 2005). Moreover, older workers are often perceived as unwilling to change, less motivated at work, poorer performers, and unhealthy (Ng and Feldman, 2012). This implicit or explicit competition between younger and older workers often results in older workers leaving the workforce prematurely, particularly if severance pay or early retirement incentives are offered (Brooke and Taylor, 2005).

Wise organizations, by contrast, do not only strive for racial, ethnic, and gender equality in their organizational culture but also appreciate the experience, tacit knowledge, and personal growth that older employees have accumulated (Hilsen and Olsen, 2021). Peterson and Spiker (2005) suggested that older workers possess intellectual, psychological, emotional, and social capital, which younger workers might lack. Intellectual capital consists of their work experiences, skills, and tacit knowledge, which is knowledge gained through experience that is difficult to express explicitly and to obtain vicariously through studying or reading books (Sternberg, 1998). The psychological capital of older workers includes the confidence, hope, optimism, and resilience that people obtain when they become experts in their job and know how to deal with crises and unexpected events that are not part of routine. Because they have worked in their field for a long time, older workers have “seen it all” and their equanimity is not as easily upset as that of younger workers. Older workers often have greater emotional capital than younger workers. Due to their past experiences and greater emotional maturity, they tend to be better at self-regulation than younger workers if things do not go as expected and planned. Long-time employees might also be more motivated to help the organization succeed than younger workers who joined the organization only recently and have not yet developed organizational loyalty. Finally, older workers’ social capital manifests in their work networks that they can tap into for help and advice and their behavior as organizational citizens. Compared to younger workers, older workers are more likely to engage in behavior that contributes to the overall success of the organization but is not necessarily formally recognized and rewarded, such as socializing new employees into the organization’s culture.

Wise organizations promote professional growth for all employees not just the young. They value older employees as mentors for younger workers to cultivate the intellectual, psychological, emotional, and social capital that older workers possess (Moon, 2014; Burmeister et al., 2020; Hilsen and Olsen, 2021). Helping the young to develop and grow allows middle-aged and older adults to engage in generative behavior that contributes to their psychosocial growth (Erikson et al., 1986; McKenna and Rooney, 2019; Wang and Fang, 2020) and subjective well-being (Stevens-Roseman, 2009; Shilo-Levin et al., 2021).

Testing the Effects of Wise Organizations on Wise Leadership and Employee Satisfaction and Well-Being

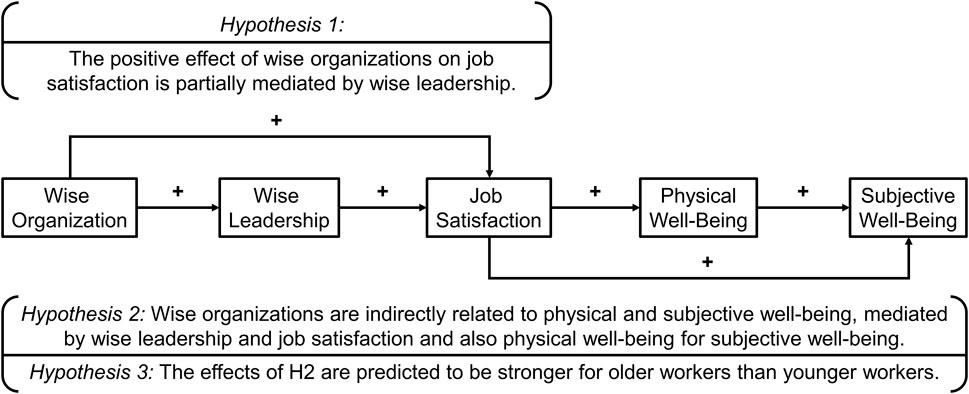

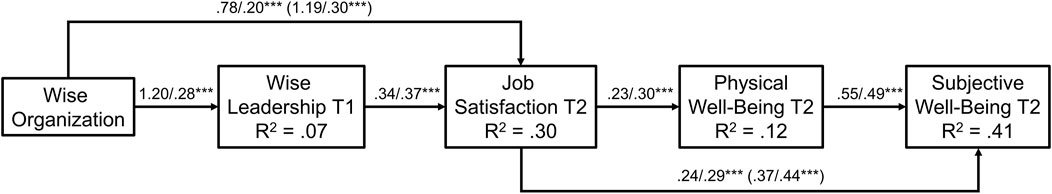

Given the delineated differences between wise and not-so-wise organizations, it is likely that wiser organizations benefit employees. To empirically test this assumption, a path model was developed that linked wise organizations to employees’ work-related and personal well-being (see Figure 1). First, we hypothesized that wise organizations have a positive impact on employees’ job satisfaction, partially mediated by wise leadership (Hypothesis 1). A wise organization will encourage a wise leadership style that is fair and supportive (Küpers and Statler, 2008; Rowley and Gibbs, 2008; McKenna and Rooney, 2019) and offer work that is meaningful and fulfills humans’ psychological needs for autonomy, relatedness, competence, and security, resulting in greater job satisfaction (Ryan and Deci, 2001; Lund, 2003; Aydin and Ceylan, 2009; Fatimah et al., 2012; Malik, 2013; Artz and Kaya, 2014; Unanue et al., 2017; Rothausen and Henderson, 2019; Zacher and Kunzmann, 2019). Job satisfaction was conceptualized in this study as viewing one’s career as a calling, satisfaction with career progress, engagement at work, and organizational commitment.

Second, we also predicted that wise organizations would initiate a positive chain reaction with positive effects of wise organizations on wise leadership and employees’ job satisfaction, wise leadership on job satisfaction, job satisfaction on employees’ physical and subjective well-being, and physical well-being on subjective well-being (Hypothesis 2). That is, wise organizations were expected to be directly related to wise leadership and job satisfaction and indirectly to physical and subjective well-being, mediated by wise leadership and job satisfaction. Research has demonstrated the important role of an ethical and supportive leadership style on employees’ job satisfaction (Aydin and Ceylan, 2009; Neubert et al., 2009; Schyns et al., 2009; Toor and Ofori, 2009; Long et al., 2014; Hoch et al., 2018; Khan and Lakshmi, 2018; Qing et al., 2019). Job satisfaction, in turn, tends to have a positive impact on both health and subjective well-being (Abramson et al., 1994; Cass et al., 2003; Judge and Ilies, 2004; Faragher et al., 2005). Finally, physical well-being and health have been shown to be consistent predictors of subjective well-being (Pinquart, 2001; George, 2010; Ngamaba et al., 2017), although subjective well-being might positively impact physical health longitudinally as well (Diener et al., 2017; Steptoe, 2019). Third, these effects were expected to be stronger for older workers than for workers under the age of 50 who can more easily change jobs if they are unhappy in a particular organization (Hypothesis 3).

Materials and Methods

Design

We designed a path model to test the hypotheses shown in Figure 1 and used secondary data from the 2007–2008 Age and Generations Study (Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer, 2013) to create a novel wise organization index, guided by the contrast between wise and not-so-wise organizations. The Age and Generations Study was well suited to test the hypotheses, because the data set contained responses from a large number of employees within nine organizations and longitudinal data on the organization, work situation, and personal well-being. This made it possible to measure organizational wisdom at the organizational level and perceptions of wise leadership at least 6 months before assessing employees’ job satisfaction and personal well-being to reduce the impact of common method variance (CMV), which might inflate the associations between employees’ perception of wise leadership and their own job satisfaction and well-being (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

Procedure and Sample

The original purpose of the 2007–2008 Age and Generations Study was to study the impact of organizational characteristics and multigenerational teams on employee outcomes and the unit’s performance and productivity (Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer, 2013). Organizations with multigenerational department/work units with a minimum of 200 employees in five industry sectors (retail, pharmaceuticals, finance and insurance, health care and social assistance, and higher education) were identified. Interested organizations were contacted through Human Resources, and employees of departments/work units in the organization with at least 100 employees were asked to participate in the study and complete an online or mail survey. Employees were asked to answer the survey twice between 2007 and 2008, with the 2nd survey invitation sent at least 6 months after the initial survey. Data were collected anonymously through random identification numbers, user names, and passwords that were assigned to respondents and kept separately by an external survey company.

A total of 1779 employees from nine organizations participated during the first wave of data collection, 1,097 employees took part in the second wave of data collection, and 910 employees completed both surveys. The current study contains the data of 821 employees who participated in Wave 1 and Wave 2 of data collection and had valid values on all the study variables. The 821 employees ranged in age from 19 to 74 years (M = 41.98, SD = 12.26), and 63% were female, 85% were white, and 34% identified as supervisors in their organization.

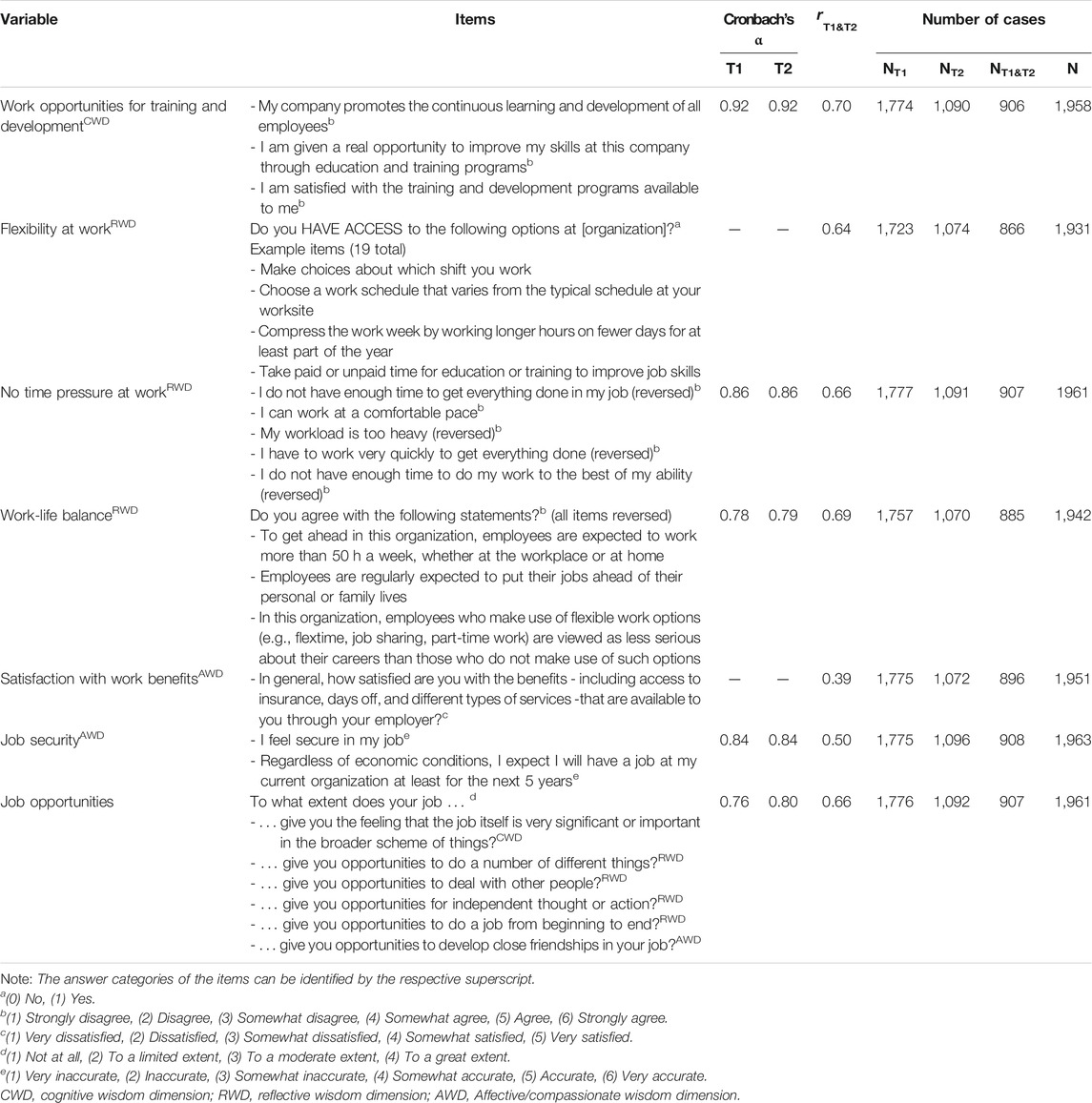

Measures

We used the characteristics of wise organizations listed in Table 1 to guide the operationalization of wise organization, wise leadership, and job satisfaction of employees. The characteristics that are represented in the measures are denoted by superscripts in Table 1 for wise organizations (O), wise leadership (L), and job satisfaction of employees (E). However, because this is a secondary data analysis, not all characteristics were available.

Wise organization was assessed as the average ratings of up to 1966 employees of seven variables: employees’ perceived work opportunities for training and development, flexibility at work, absence of time pressure at work, work-life balance, satisfaction with work benefits, job security, and job opportunities (see Table 2). Although it would have been ideal to assess all characteristics of wise organizations as listed in Table 1, the current study focused on employees’ perceptions of organizational culture based on the available measures in the Age and Generations Study. In Table 2, the cognitive dimension of the Three-Dimensional Wisdom Model is represented by work opportunities for training and development (“Approach” and “Perceptions of aging” in Table 1) and the feeling that the job itself is very significant or important in the broader scheme of things, which relates to the deeper meaning and purpose of the organization (“Goals” in Table 1) and employee fulfillment (“Characteristics of employees” in Table 1). To engage in perspective-taking, described by the reflective dimension of wisdom, a democratic workplace is required (“Approach” in Table 1) that provides employees flexibility, a sense of control, enough time and down-time to do the best work possible and achieve a satisfactory work-life balance, and opportunities for autonomy (“Characteristics of employees” in Table 1). The affective/compassionate wisdom dimension is exemplified by an organizational culture that serves all stakeholders and offers satisfactory work benefits (“Approach” in Table 1), secure employment, and opportunities for close friendships at work to develop a spirit of community (“Characteristics of employees” in Table 1).

Table 2 list the number of items for each variable, the answer scales, Cronbach’s alpha values for Wave 1 (T1) and Wave 2 (T2) scales, the test-retest correlation (r) between T1 and T2 variables, the number of respondents at T1 and T2, and the number of respondents who participated at both T1 and T2. Cronbach’s alpha values are not appropriate for the index flexibility at work, and satisfaction with work benefits consisted of a single item only. For the remaining variables, Cronbach’s alpha values ranged between 0.76 and 0.92. The test-retest correlations showed relative stability, ranging from 0.50 to 0.70, with the exception of 0.39 for the single item of satisfaction with work benefits.

The wise organization index at the organizational level was constructed as follows: First, the mean of all valid T1 and T2 items for a variable was computed. For respondents who only participated at T1 or T2, the respective T1 or T2 items were used, whereas T1 and T2 items were averaged for respondents who participated in both waves, resulting in the total number of cases for each variable that is shown in the last column of Table 2. Second, all variable scales were transformed into 1–6 scales. Third, the average of the seven variables was computed to construct the wise organization index at the employee level. Fourth, a one-way ANOVA with employees’ wise organization index as the dependent variable and organization identification number as the independent variable was conducted. Fifth, each of the nine organizations was assigned the average wise organization value of their respective employees. This procedure resulted in a wise organization index that consists of nine values, ranging from 3.90 to 4.62 on an original 1–6 scale (M = 4.31, SD = 0.21). Between 74 and 390 of the 1966 employees (median = 237 employees) contributed to the average wise organization rating of their respective organization. Because the names of the organizations were masked in the publicly available dataset, we do not know which organization received the highest or lowest value, but the differences in average values between many of the organizations were statistically significant, F (81,957) = 33.92, p < 0.001.

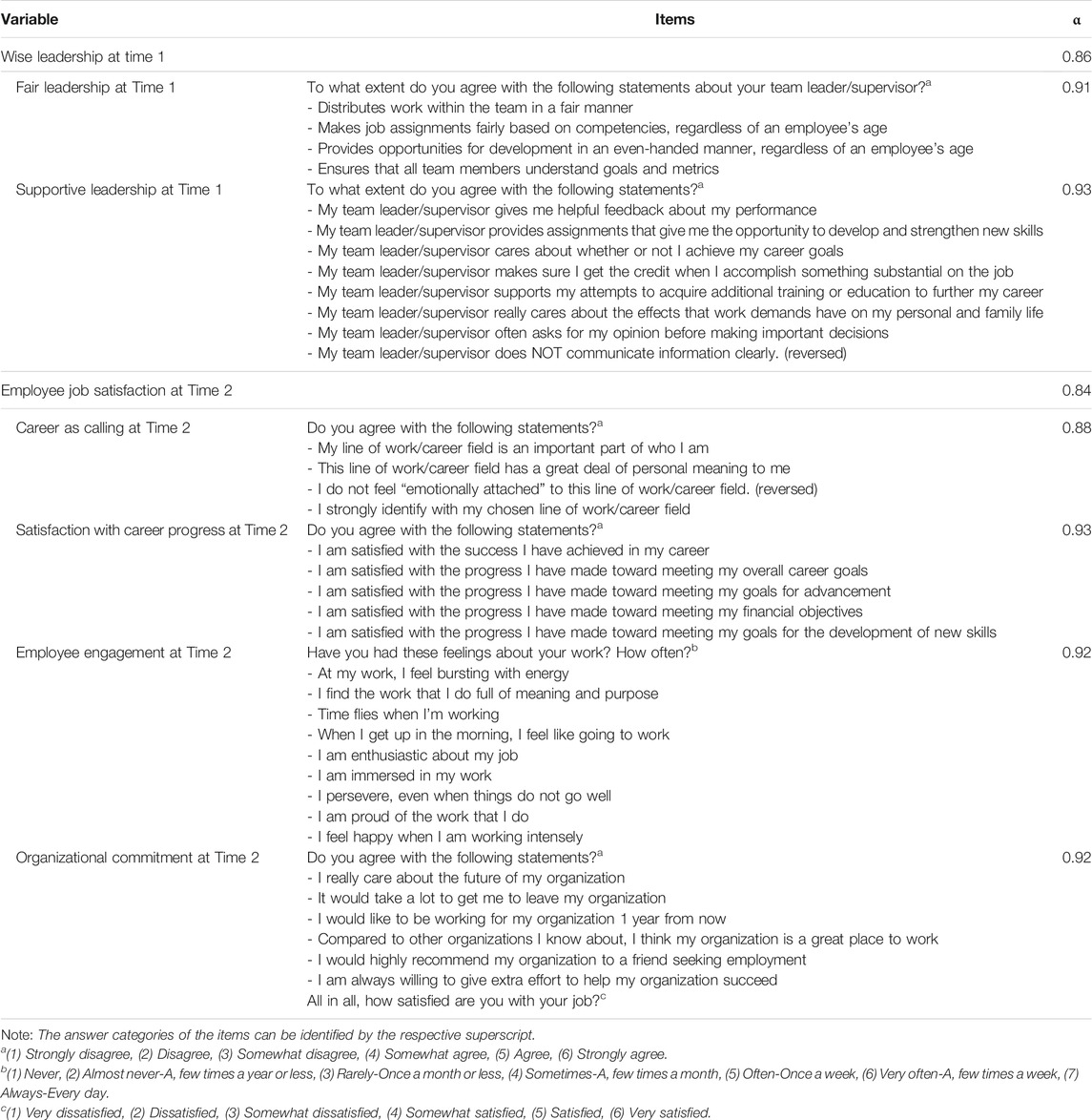

Wise leadership was assessed as the average of fair and supportive leadership at T1 at the individual level rather than the organizational level, because it is unlikely that all respondents of a particular organization had the same team leader or supervisor. Fair leadership was measured on 6-point scales as the average of four items and supportive leadership as the average of eight items listed in Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91, 0.93, and 0.86, respectively, for fair leadership, supportive leadership, and wise leadership based on the average of the fair and supportive leadership variables to weigh both variables equally (Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 for the 12 items). The correlation between fair and supportive leadership was r = 0.76 (p < 0.001).

Employee job satisfaction at T2 was the average of four variables: career as a calling, satisfaction with career progress, engagement at work, and organizational commitment (see Table 3 for details on items and answer scales). The four to nine variable items were averaged to compute each variable, resulting in Cronbach’s alpha scores ranging from 0.88 to 0.93. Subsequently, the 1–7 scale for engagement at work was transformed into a 1–6 scale before the mean of all four variables was taken to measure employee overall job satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha for this 4-variable scale was 0.83.

Physical well-being at T2 consisted of the average of five items that asked respondents to rate their health (1 = very poor, 6 = excellent), physical health problems (1 = not at all, 5 = could not do physical activities or could not do daily work), bodily pain (1 = none, 6 = very severe), and energy level (1 = very much, 5 = none) during the past 4 weeks. All items were transformed into 1–5 scales and scored in the direction of greater physical well-being before the average of the five items was computed. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

Subjective well-being at T2 was the average of three items. Two items asked respondents how much they have been bothered by emotional problems (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely) and how much personal or emotional problems kept them from doing their usual work, school, or other daily activities (1 = not at all, 5 = could not do daily activities) during the past 4 weeks. A third item inquired how respondents felt about their life these days, all things considered (1 = very dissatisfied, 6 = very satisfied). The first two items were reverse-coded, and the third item was transformed into a 1–5 scale before the average of the three items was taken, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.

Being a supervisor (0 = no, 1 = yes) was included as a control variable, because employees who are supervisors might be more dedicated to their job and invested in the organization. Respondents were categorized as a supervisor if they held this position at either T1 or T2. Other control variables were female gender (0 = no, 1 = yes), white race (0 = no, 1 = yes), age (in years), and education, assessed as highest grade completed on a 7-point scale (1 = less than high school, 7 = graduate degree) averaged across T1 and T2 (r = 0.97, p < 0.001).

Data Analysis

To check the correlations between the variables, Pearson’s bivariate correlations were performed first. Because the data consisted of organizational-level data and employee-level data, a two-level hierarchical linear model (HLM) might have been appropriate with wise organization as the level-2 variable and all remaining variables as level-1 variables, nested within the organization, although the level-2 statistical power was low with only nine organizations. To check whether HLM was necessary, four intercept-only models (unconstrained or unconditional models) with wise leadership, employee job satisfaction, physical well-being, and subjective well-being as the outcome variables were analyzed, using the mixed model procedure in SPSS 27 (Woltman et al., 2012). Results indicated that the variance in the four outcome variables by organization was not significantly different from zero with p-values ranging from 0.06 for job satisfaction as the outcome variable to 0.28 for subjective well-being as the outcome. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) ranged from 0.01 for subjective well-being to 0.14 for job satisfaction, meaning that only between 1% and 14% of the variation in the dependent variables could be accounted for by organization, while between 86% and 99% of the variation in the dependent variables could be accounted for by employees within organizations. Therefore, not enough between-organization variance existed to justify using HLM.

Instead, single and multigroup path models were analyzed, using LISREL 9.30, to test the hypotheses and compute indirect effects. Because a preliminary analysis in PRELIS 9.30 indicated that the variables did not follow a multivariate normal distribution (χ2 = 872.91, p < 0.001), the covariance and asymptotic covariance matrices were computed and weighted least squares (WLS) estimation was used to obtain corrected χ2-statistics, consistent coefficient estimates, and asymptotically correct standard errors and t-values of the estimates (Jöreskog et al., 1999). The WLS estimator is asymptotically sufficient even under the condition of nonnormality (Bollen, 1989).

Results

Bivariate Analysis

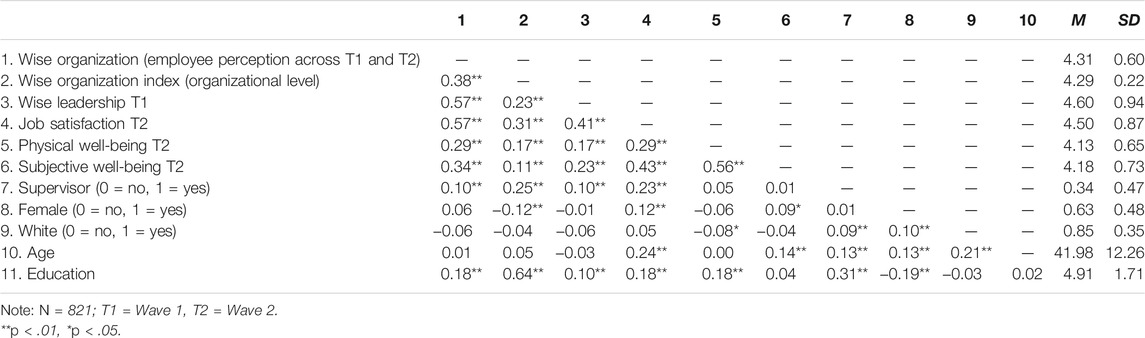

Table 4 shows the bivariate correlations between the study variables. Wise organization at the employee level is included in the table only for comparison purposes with wise organization at the organizational level. Not surprisingly, employees’ wise organization perception was more strongly correlated with the dependent variables than the organizational level wise organization index. However, employees’ perception of their organization might be affected by CMV, whereas the organizational level wise organization index is based on the average ratings of 74–390 employees of their respective organization and all 1966 respondents who participated in either Wave 1 or 2 of data collection. Therefore, the wise organization index is a more valid and reliable measure of wise organization at the organizational level than an employee’s individual perception of their organization. The correlation between the organizational and individual measure of wise organization was moderate, indicating that some agreement but also some variability existed among employees about their organization’s level of wisdom. Yet, even at the organizational level, the wise organization index was positively and significantly correlated with employees’ perception of wise leadership at T1 and their job satisfaction and physical and subjective well-being at T2. Moreover, supervisors, men, and respondents with a higher education were more likely to be employed by an organization with a higher wise organization index than non-supervisors, women, and those with a lower education. Interestingly, education was only weakly positively correlated with employees’ individual perception of their organization but strongly correlated with wise organization at the organizational level. This suggests that the workforce of wise organizations tends to have a higher average education level than the workforce of less wise organizations. In fact, the correlation between the wise organization index and the average education level for the nine organizations was r = 0.76 (p = 0.017, n = 9).

The correlations among the four dependent variables were positive and significant as expected. Among the control variables, being a supervisor was positively correlated with the perception of wise leadership and job satisfaction. Women and older employees tended to be more satisfied with their job and report higher subjective well-being than men and younger employees. Non-whites reported slightly higher average physical well-being scores than whites. Education was positively correlated with wise leadership perception, job satisfaction, and physical well-being.

Multivariate Path Analysis

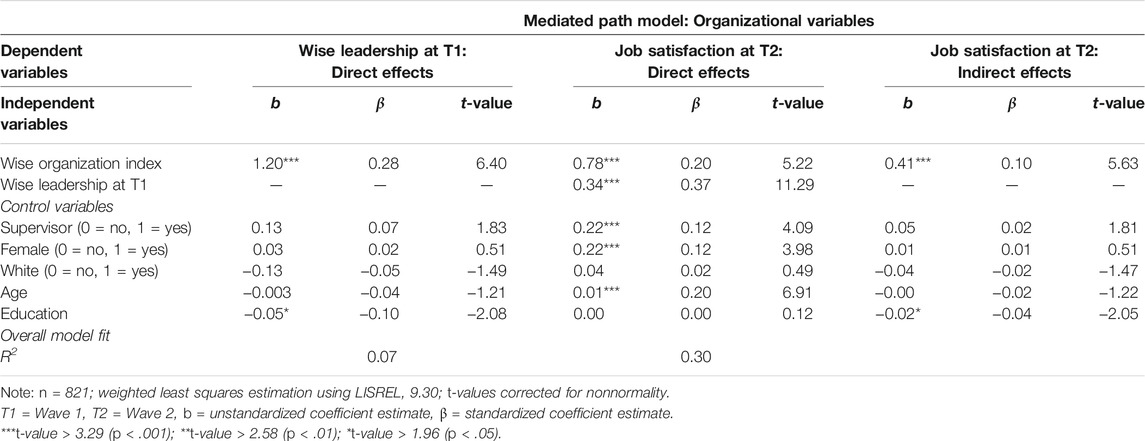

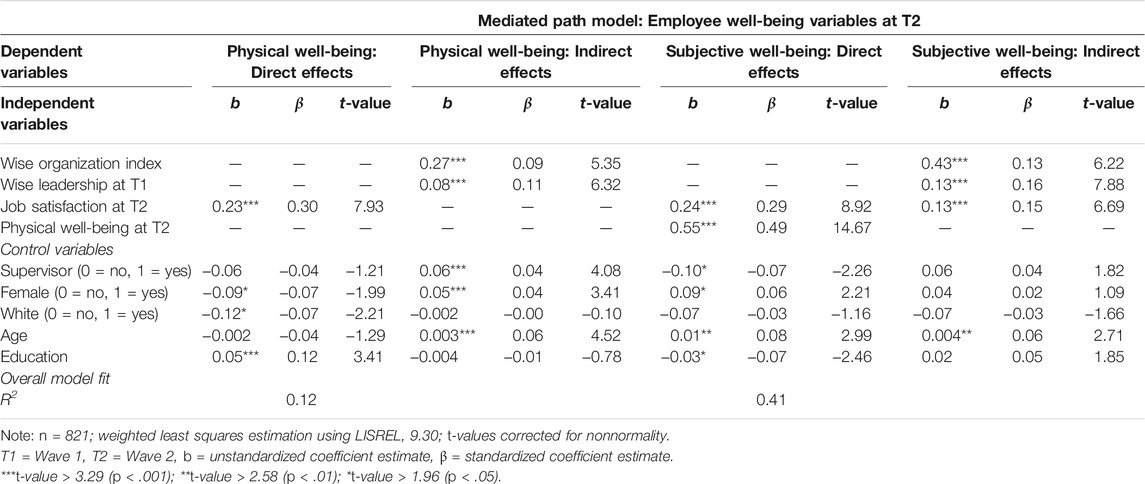

The results of the path analysis are shown in Table 5A and Table 5B and Figure 2, controlling for supervisor position, gender, race, age, and education. As predicted, wise organization was positively related to wise leadership at T1 and job satisfaction at T2. The direct effect of wise organization on job satisfaction at T2 was partially mediated by wise leadership at T1, confirming Hypothesis 1. About one-third of the association between wise organization and job satisfaction was mediated by wise leadership, as indicated by a significant indirect effect of wise organization on job satisfaction in addition to the direct positive effect. In accordance with Hypothesis 2, wise organization had a positive chain reaction effect on subjective well-being, mediated by wise leadership, job satisfaction, and physical well-being. Wise organization was positively related to wise leadership at T1 and job satisfaction at T2, job satisfaction at T2 was positively related to physical and subjective well-being at T2, and physical well-being at T2 was positively related to subjective well-being at T2, resulting in significant positive indirect effects of wise organization on physical and subjective well-being at T2. The direct positive effect of job satisfaction on subjective well-being was partially mediated by physical well-being as expected, as indicated by significant direct and indirect positive effects of job satisfaction on subjective well-being. Again, about one-third of the association between job satisfaction and subjective well-being was mediated by physical well-being. As part of the chain reaction of effects, wise leadership at T1 was also significantly indirectly related to greater physical well-being at T2, mediated by job satisfaction at T2, and to greater subjective well-being at T2, mediated by job satisfaction and physical well-being.

FIGURE 2. Results of the Path Analysis Model. Note: n = 821; WLS estimation using LISREL 9.30; unstandardized/standardized coefficient estimates controlling for supervisor position, gender, race, age, and education level; standard errors, t-values, and χ2 statistics corrected for non-normality. Unmediated direct effects of wise organization on job satisfaction and job satisfaction on subjective well-being in parentheses. WLS χ2 = 2.97 (p = 0.56, df = 4); GFI = 0.92, CFI = 1.00, IFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0; p for RMSEA<0.05 = 0.97; CN = 3,671.34. ***t-value > 3.29 (p < 0.001).

After controlling for all the other variables in the model, being a supervisor was positively directly related to job satisfaction and indirectly to physical well-being, mediated by job satisfaction. However, supervisors tended to score slightly lower on subjective well-being than non-supervisors. Yet, the total effects of being a supervisor on physical well-being (unstandardized/standardized total effect = −0.001/−0.001, t = −0.02, p = 0.99) and subjective well-being were non-significant (unstandardized/standardized total effect = −0.04/−0.03, t = −0.70, p = 0.48), because the direct and indirect effects canceled each other out. Compared to men, women tended to report greater job satisfaction and subjective well-being but also lower physical well-being. However, the indirect effect of being female on physical well-being was positive, mediated by job satisfaction. The negative direct effect and positive indirect effect of being female on physical well-being canceled each other out, resulting in a non-significant total effect of gender on physical well-being (unstandardized/standardized total effect = −0.04/−0.03, t = -0.76, p = 0.45). Non-white employees tended to report slightly higher physical well-being scores than white employees. Age was positively related to job satisfaction and subjective well-being, and indirectly positively related to physical and subjective well-being, mediated by job satisfaction, although the total effect of age on physical well-being was non-significant (unstandardized/standardized total effect = 0.001/.014, t = 0.40, p = 0.69). Education was negatively related to wise leadership scores and subjective well-being but positively to physical well-being. Yet the total effect of education on subjective well-being was non-significant (unstandardized/standardized total effect = −0.01/−0.03, t = -0.76, p = 0.45).

The variables in the model explained 7% of the variation in wise leadership at T1, 30% of the variation in job satisfaction at T2, 12% of the variation in physical well-being at T2, and 41% of the variation in subjective well-being at T2. Overall, the model fit the data well, with a non-significant WLS χ2-value of 2.97 (p = 0.56, df = 4), high goodness of fit (GFI), comparative fit (CFI), and incremental fit (IFI) indices, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of zero, and a Critical N (CN) of 3,671.34 that was much higher than the recommended minimum value of 200 (Bollen, 1989; Kline, 2005).

Additional multigroup analyses in LISREL 9.30 were conducted (not shown) to test whether the effects of the path model were significantly stronger for older workers (N = 269; age range 50–74 years, M = 56.08, SD = 5.04) than for younger workers (N = 552; age range 19–49 years, M = 35.10, SD = 8.17) who can more easily change jobs. Contrary to Hypothesis 3, the effects were not statistically different between the two age groups with one exception. Surprisingly, physical well-being was statistically stronger related to subjective well-being among younger rather than older workers, possibly indicating a positive health selection effect in the older age group. The effects of the control variables also did not differ significantly by age group with the exception of three age effects. Age was significantly positively related to wise leadership and physical and subjective well-being only among older workers. Age was significantly negatively related to physical well-being among younger workers. These results suggest that working at older ages and past social security eligibility more likely occurs if older employees feel healthy and well.

Discussion

Wisdom has been used to describe individuals, decisions, and advice, yet it can also be applied to organizations (Srivastva and Cooperrider, 1998; Limas and Hansson, 2004; Kessler, 2006; Hays, 2008; Rowley and Gibbs, 2008; Spiller et al., 2011; Zaidman and Goldstein-Gidoni, 2011; Pinheiro et al., 2012; Mora Cortez and Johnston, 2019). We compared wise and not-so-wise organizations in the areas of goals, approach, range, characteristics of leaders and employees, and perception of aging. Guided by these comparisons, we assessed wise organizations as an index of employees’ perception of work opportunities for training and development, flexibility at work, absence of time pressure at work, work-life balance, satisfaction with work benefits, job security, and job opportunities based on available measures in the 2007–2008 Age and Generations Study. High scores on these measures indicated that employees felt a) their organization was a democratic workplace, where employees were provided some autonomy over how and when they worked, b) they had opportunities for advancement and development, satisfactory work benefits, job security, and enough time to provide the best services or products without neglecting their home life, and c) their job provided a variety of opportunities and was personally significant and meaningful in the broader scheme of things.

Hypothesis 1, which predicted that a wise organization would enhance employees’ job satisfaction, in part by encouraging wise leadership, was supported. Employees who worked in wiser organizations rather than in less wise organizations were more likely to rate their team leader or supervisor as wise and tended to be more satisfied with their job, which was partially due to the perception of wise leadership. Wise leadership was assessed as the average of fair and supportive leadership, and job satisfaction included how much employees perceived their career as a personal calling, how satisfied they were with their career progress, how engaged, motivated, energized, and enthusiastic they were about their work, and how committed and loyal they were to their organization, because they felt it was a great place to work. These positive organizational, leadership, and work characteristics were predicted by Hypothesis 2 to have a beneficial impact on employees’ physical well-being and also their subjective well-being, partially mediated by physical well-being. This hypothesis was corroborated as well as illustrated in Figure 2. Compared to employees in less wise organizations, employees in wiser organizations tended to be more satisfied with their job and perceive their team leader or supervisor as wiser, which tended to contribute to greater job satisfaction, and employees who were satisfied with their job, in turn, were more likely to report higher physical and subjective well-being than those who felt less job satisfaction. Physical well-being tended to further enhance employees’ subjective well-being. Therefore, wiser organizations tended to benefit their employees’ physical and subjective well-being indirectly through wise leadership and greater job satisfaction. The path model in Figure 2 was equally valid for younger workers under the age of 50 and older workers between 50 and 74 years of age, except that the relation of physical well-being on subjective well-being was significantly stronger for younger than older workers, rejecting Hypothesis 3.

All of the analyses controlled for supervisor position, gender, race, age, and education level. Combining direct and indirect effects and after controlling for all of the other variables in the model, being a supervisor was positively related to job satisfaction, women and older participants tended to score higher on job satisfaction and subjective well-being than men and younger participants, whites tended to report lower physical well-being than non-whites, and education was negatively related to assessment of wise leadership but positively to physical well-being. In addition, age was inversely related to physical well-being among workers under the age of 50, indicating that health declines with age. Yet, surprisingly, age had a significant positive association with physical well-being among workers between the ages of 50 and 74, suggesting that older workers whose health deteriorates drop out of the labor force until a primarily healthy older workforce remains. Wise organizations seem to enable workers to work longer by contributing to their work-related, physical, and subjective well-being, which allows wise organizations to benefit from the intellectual, psychological, emotional, and social capital that older workers have accumulated (Peterson and Spiker, 2005).

To reduce the influence of CMV, wise organization was assessed at the organizational level as the average wise organization score of the 1966 employees in the nine organizations who participated in at least one wave of data collection, and employees’ perception of wise leadership was measured at least 6 months before job satisfaction and physical and subjective well-being of employees were assessed, which is one recommendation to deal with CMV (Podsakoff et al., 2012). This resulted in an analysis sample of 821 employees who took part in both surveys. While employees’ physical and subjective well-being might also affect the perception of their job satisfaction (Weziak-Bialowolska et al., 2020), it should be noted that most of the items used to assess job satisfaction in this study suggest greater temporal stability than the physical and subjective well-being measures, which inquired specifically about the employees’ well-being “during the past 4 weeks” or “these days.” Hence, it appears more likely that job-related variables affected employees’ physical and subjective well-being than vice versa.