95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Commun. , 16 July 2021

Sec. Culture and Communication

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.668086

In Nepal, after every large earthquake, local people appear to be motivated to get better prepared for future earthquakes. However, their motivation vanishes before effective preparation, mainly due to the lack of earthquake education in their community. Promoting up-to-date scientific knowledge to a society living under high earthquake hazard is important and contributes to reduce the related risk. The dissemination of information in Nepal lags far behind modern seismological knowledge, and part of the local population still believes in religious explanations and stories about earthquakes. We run an educational program in Nepal to make people better aware of earthquakes and to improve their preparedness through obligatory school education, but the dichotomy between scientific and religious visions of earthquakes remains a challenge. For more efficient acceptance of earthquake preparatory advices, it is important to better perceive the religious narration of earthquakes and to include these in the educational communications. Thereby, we reviewed the main sources of Hindu literature and gathered relevant and interesting explanations on earthquake evidences and causes. The primary religious interpretations of earthquakes in different Hindu texts are related to the Gods and their actions, and some sources also include physical descriptions of earthquakes related situations or processes. We found that most of the stories, causes and explanations of earthquake do not match with the concepts of modern science, yet there are exceptions such as a historically old advice to leave buildings during the shaking. The collected findings are important not only from a religious literature review perspective, but also and mainly to develop an inclusive and more efficient strategy to communicate about earthquake related topics in the classroom as well as with the public in Nepal.

To develop natural hazard and disaster communication strategies in any community, it is important to understand the contexts of intercultural interactions and communication (Mumby, 1988; Deetz, 1996). Communication research is strongly based on experience and hence should not only be relevant to everyday life but also facilitate the success of everyday intercultural encounters (Ribeau, 1997). Since intercultural communication is complex, knowledge transfer from one culture (e.g. science) to another culture (e.g. religion) must consider the social context. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate cultural variations and their impacts on communication effectiveness (Leonard et al., 2009).

The focus of culture is on structure and of communication is on process (Birdwhistell, 2010). At the same time, the two are strongly related and influence each other (Hall and Hall, 1959), mainly through social interactions of individuals. When knowledge is to be transferred from one cultural context to another, it is necessary to think in terms of communication processes adapted to both parties, and to make an effort to sensitively resolve differences (Ablonczy-Mihalyka, 2015). In the educational environment, using different and efficient communication channels between the learner and the curriculum is important (Kelly and Westerman, 2016), especially if physical presence is hindered as in the COVID-19 context (e.g., Kelly and Westerman, 2020; Brown, 2021). We entered a challenging situation of intercultural communication in frame of a Seismology-at-school program in a religious environment, and here explore the undertaken pathways for more efficient cultural exchange between science and religion, and more efficient communication with the community members.

The oldest living major religion in the world is believed to be Hinduism (e.g., Klostermaier, 2007), with roots, traditions and customs dating back to possibly more than 5,000 years (Kak, 2000). Hinduism has originated on the Indian subcontinent and about 1 billion followers including population from India and Nepal currently place Hindu as the third-largest religion after Christianity and Islam.

One of the key thoughts of Hindu people is trust in Soul, Heaven, and Hell. What they assume is that people’s current and past actions and thoughts would determine their current life and future condition for living in this world or/and after death. In another word, the Hindus fully believe in a supernatural agency where the vice of humanity causes disasters and the virtue of humanity causes happiness (Oldham, 1899).

In the Hindu pantheon, 33 types of God are recognized, which, in some regions, is considered to be 330 million Gods. While the three main Hindu lords are known as Brahma (as the creator), Vishnu (as the preserver), and Shiva (as the destroyer and re-creator), there are also other prominent deities, such as Durga representing female energy, Lakshmi (for wealth), Kali (worshipped during the Diwali festival), Saraswati (for learning and knowledge), Swasthani (for miraculously granting wishes), etc. Kali is the fearful and ferocious form of the mother goddess Durga and also worshipped during Diwali to seek the help of the goddess in destroying evil. Most of the other deities are either related to them or represent different forms of these deities. In Hindu literature, the evil forces are represented by the Rakshasas (the demons), who are in constant battle with the Gods.

There are numerous ancient Hindu writings, yet the most important ones, namely Vedas, Ramayana, Mahabharata, Bhagwat Gita (the primary holy script for Hindus) and Puranas cover sufficient material to understand the main elements of Hinduism and the Hindu perception of the environment. Among these, the word Bhumikampa ( ) and Bhukampa (

) and Bhukampa ( ) refers to an earthquake (earth tremble) in Sanskrit and Nepali language, respectively. In some explanations, the word Prithvikampa (

) refers to an earthquake (earth tremble) in Sanskrit and Nepali language, respectively. In some explanations, the word Prithvikampa ( ) is also used for explaining the earth-shaking phenomena, which exactly means the planet Earth shaking (Earth tremble). The oldest of the sacred books of Hinduism, composed in an ancient form of Sanskrit in about 1500 BCE is Rig Veda, which also contains the earliest reference to an earthquake.

) is also used for explaining the earth-shaking phenomena, which exactly means the planet Earth shaking (Earth tremble). The oldest of the sacred books of Hinduism, composed in an ancient form of Sanskrit in about 1500 BCE is Rig Veda, which also contains the earliest reference to an earthquake.

People who follow the Hindu religion believe that natural entities are also Gods. Children in the family are brought up to follow the customs and ethics of their parents, society, but are encouraged to decide for themselves which Gods and Goddesses suit them. Since ancient times, there is tradition for people to acquire a certain education, they have at least a Guru, a spiritual director who teaches them what they need to know and what they should follow. However, because of this diversity, it cannot happen that everyone knows the same things and the knowledge cannot be taught in the same way.

The above-mentioned sources and cultural frame are critical to be kept in mind when planning educational activities in Hindu communities. In late 2017, we have initiated an educational program in Nepal to make people better aware of earthquakes and to improve their preparedness through obligatory school education (Subedi et al., 2020a). Nepal is situated just above the active boundary where the Indian plate goes down beneath the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau (e.g. Subedi et al., 2018) at an average rate of ∼2 cm/year, causing earthquakes. Geoscience research has shown that devastating earthquakes occurred in the area throughout history, and also that the region is sufficiently stressed to host a great (magnitude Mw ≥ 8) earthquake (e.g., Stevens and Avouac, 2015). The associated seismic risk – the level of expected damage – is high in Nepal, and it is estimated that casualties from a future major earthquake could possibly exceed 100,000 (Bilham, 2019).

Since modern seismological information has not reached the majority of people in Nepal (and probably in neighboring countries either), part of the local population still believes religious explanations and stories about earthquakes which already exist in the community. In frame of our educational program that currently involves 30 schools and reaches thousands of students, the dichotomy between scientific and religious visions of earthquakes is a challenge. In an initial survey among students, less than two-thirds indicated the scientific reason for earthquakes (Subedi et al., 2020b). Two surveys were conducted in the Central Nepal and we have carefully analyzed the results assuming the fact that earthquake knowledge depends on several factors, for example, social status, family background, etc. In addition, earthquake information levels depend on the education levels, and this varies between rural and urban areas; that’s why we account for geographical distribution while collecting the answers for surveys.

After careful preparation of the local teachers who educate the students, 2 yr later this ratio increased to 84%. However, from our field experience of communicating with local people of different age, social status, depth of religious belief, region of origin and culture, we realized that it remains crucial to explain not only the scientific reasons but also to collect and discuss religious aspects of earthquakes with the locals. This will help to facilitate a more equilibrated dialogue and for better acceptance of preparatory advices for future earthquakes. This is why we undertook the current study, to know the original text, context, and application of religious narration of earthquakes in different sources of Hindu literature.

In our best knowledge, the information available in Hindu writings on the explanation of earth-shaking is not comprehensively summarized in English. The educational program run in Nepal provides a good opportunity to attempt to consolidate ideas regarding the description of earthquakes in the Hindu literature by compiling information documented in different stories, which ultimately help to develop a better strategy for earthquake hazard and risk communication in Nepal.

Our primary approach was reading original sources and, wherever necessary, asking for professional translations of texts from Sanskrit. The texts were read in Nepali language by the first author of this study, and all texts can be found in bookshops. The exact versions of books that served as the basis of this study are described in the references. Subsequently, for sections identified as related to physical explanations of earthquakes, we compared the findings with concepts of modern seismology based on our experience of research, teaching, geophysical reference books and scientific literature.

To search the explanation of earthquakes, their cause and evidence if any mentions exist, we first read two major Hindu epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata thoroughly.

An important book of Hindu tradition in terms of both literature and philosophy is Bhagwat Gita (literally meaning “the song of the Lord”), the text of which we also browsed and found some interesting explanations about the creation of the world. In Hindu literature, the possibly heaviest books, explaining the history of the Universe from creation to destruction as well as the genealogies of kings, heroes, sages, and deities, are Puranas. They are written in the form of a dialogue and are composed of 400,000 words. To read all sequences of Puranas is beyond the scope of this work, however we scanned the text for a section of Puranas where our subject of interest is described, Agni Puranas.

We also select books that cover the broad range of topics and include explanations of earthquakes with details, such as Brihat Samhita and Adbhuta Sagara. We also browsed the Rig Veda for earthquake related stories.

We also review a book that is widely followed by Nepali women, called Swasthani Brata Katha, a Hindu tale narrated within the community every day for a month (the month of Magh, spanning approximately from mid-January to mid-February in each year).

The choice of text sources already reflects selective coding as we were principally interested in descriptions of earthquakes and related phenomena. On these sources, open coding was applied by browsing the full texts, so the selected chapters or paragraphs can be analyzed in more detail. Finally, to categorize our findings, we applied axial coding to re-group text of similar content and context – this choice is reflected in our work below. Wherever necessary, repeated reading or new translations of important text sections have been performed to clarify the content in the context of our analysis.

Finally, we have also asked relevant advice from nationally influential spiritual speakers who usually explain Hindu religion for the community.

The story written in Mahabharata probably around 200 BC is about the struggle between two groups of cousins in the Kurukshetra War (ca. 900 BC) and the fates of the Pandava Princes and the Kaurava, their successors (Penna, 1989). The Pandava refers to the five brothers namely, Yudhishthira, Bhim, Arjun, Nakul and Sahadeva, who are the main characters in the epic Mahabharata. They were the sons of Pandu, the king of Hastinapur and his two wives Kunti and Madri. The five brothers shared a wife, Draupadi. The Pandava waged war against their cousins Kaurava (Duryodhana and his brothers); Pandava won the war. In Mahabharata, Danava are described as powerful superhuman with good or bad qualities, and Danava battle constantly with the Gods. Although it is unlikely that any single person wrote the poem, its authorship is traditionally ascribed to the sage Vyasa (Vyasa, 1883; Roy, 1958). In Mahabharata and Brihat Samhita, it is mentioned that animal shows abnormal behavior before the earthquake, but does it relate with science or not is ongoing debate at least in the Neapli communities.

The poem is an ancient Sanskrit epic which follows Prince Ram’s quest to rescue his beloved wife Sita from the clutches of Ravana with the help of an army of monkeys. It is traditionally attributed to the authorship of the sage Valmiki and dated to around 500–100 BCE (Vatsyayan, 2004). The Ramayana is widely considered to be the first Nepali epic and is translated in the Nepali language by a Nepali poet, Bhanubhakta Acharya (Gyawali, 1997).

A set of questions asked by Lord Arjun about many human ethical dilemmas, philosophical issues, and life’s choices, answered by Lord Krishna right before the start of the climactic Kurukshetra War, is documented in Bhagwat Gita (Wilkins, 2008). The Bhagwat Gita was written about 5,000 yr ago (Satpathy and Muniapan, 2008), but it still reads absolutely new, fresh and relevant in today’s time for Hindu people.

A vast genre of Hindu literature, Puranas are primarily composed in Sanskrit and they are about a wide range of topics, particularly myths, legends, and other conventional knowledge. The first version of Puranas was likely to been composed between 300 and 1000 CE (Collins, 1988) and there are 18 great and 18 minor Puranas composed by 400,000 words (Chandra, 2017). Furthermore, in Agni Puranas, there is a dedicated chapter, chapter 263, in which different types of natural phenomena and measures of peace are described (Chaturvedi, 2002).

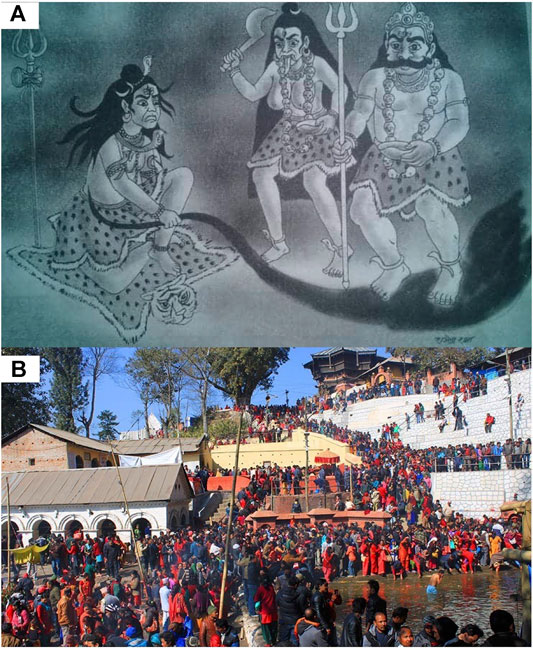

It is a series of stories mostly focused on Lord Shiva and described by Lord Kumar, the elder son of Shiva and Parvati, to Agastya Muni (a saint person). Swasthani is the Hindu Goddess who is very blessing to all her devotees and she always fulfills wishes of all those who adore her with a pure heart and full devotion (Birkenholtz, 2010; Shree Swasthani Brata Katha, 2020). It starts on the full moon day at the beginning of the month of Magh (ca. January or February) and continues as a series of 31 chapters for 31 days until the next full moon. When Agastya Muni wanted to know how this universe was formed, Kumar tells him the story. Since Swasthani Brata Katha is currently popular in Nepal and Hindu women strongly follow it, it is important to review this story as well. As presented in the story, some place’s name matches with present geographical locations in Nepal. For example, in the text, the Sali River is famous and widely described, and it is believed that having a ritual bath in Sali River may remove all the sins and bad activities; in the same time, there is a Sali River and Swasthani Temple near the Kathmandu Valley (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1. Showing the power of the God Shiva and Goddess Swasthani. (A) An illustration showing God Shiva while creating two Gods, Mahankali and Veerbhadra, by plucking two of his hairs, throwing them on the ground and making the earth to tremble (Swasthani, 2020: 69). (B) A picture of Nepali women at the Goddess Swasthani temple in Kathmandu waiting for worship (photo credit: Nakarmi, 2019).

These two books Brihat Samhita (origins at ca. 400–600 CE) and Adbhuta Sagara (900–1100 CE) are encyclopedic texts, including descriptions of earthquake phenomena with detailed information (Lyengar, 1999). These two sources have been briefly mentioned in the analysis of Iyengar (1999), however his work focused more on earthquake effects and we here decided to work directly from the original sources.

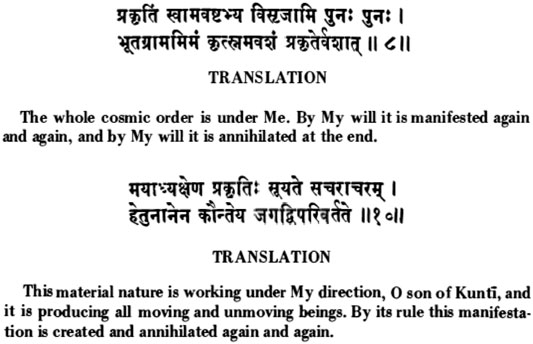

Earlier studies show that Hindu people have a great faith on the Gita philosophy (e.g., Dahal, 2019). In chapter 9 of Bhagwat Gita, the science of sciences and the mystery of mysteries about the Earth, its creation, and its destruction is presented. According to Krishna, the world is an indication of the energy of the supreme personality of Godhead. The universe belongs to Krishna by his divine energy which is difficult to overcome and all-natural phenomena including disasters are controlled by him. Also, nature produces all things movable and immovable in the world, under his guidelines. There is a personality who wields the power of Nature under Lord Shiva’s protection on behalf of Krishna. So “Mother Nature” is correct and refers to Durga. Then, Durga has many responsibilities which include control of the Sun, Moon, rains, winds, oceans, earthquakes, fire, and everything else that happens in the world. All the phenomena happening in this world are under the interest of Lord Krishna. The root cause for the creation of Nature and its destruction through ailments or natural disturbances like earthquakes or hurricanes or tsunamis would be upon the interest of Lord Krishna. Thus, Krishna told very clearly, God is responsible for the creation, sustenance, and destruction of this universe (Prabhupada and Swami, 1972). So, it is the God only who is doing all the phenomena in this world. Hence, he is responsible for everything happening on this Earth. This is the explanation of Nature and its creation according to Bhagwat Gita (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Description of Nature and its phenomena in Bhagwat Gita in Sanskrit and English (from Prabhupada and Swami, 1972).

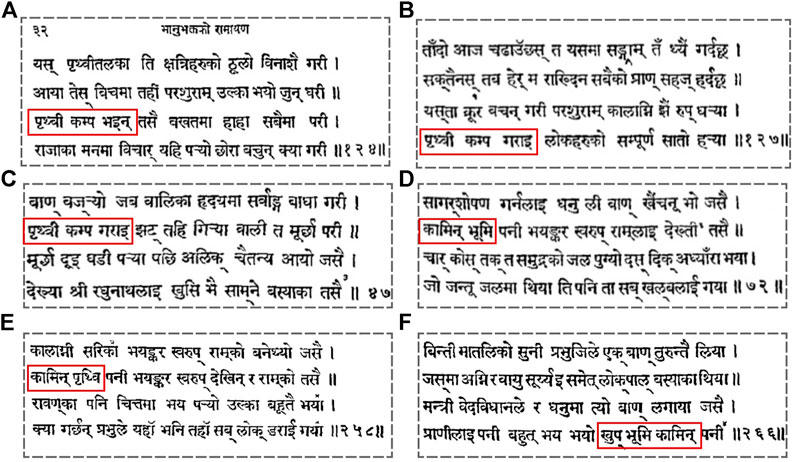

Some evidences for earth tremble are described in Ramayana. When Ram was on the way to Ayodhya, there were bad omens for though the birds in the air indicated approaching trouble, the animals on the lands were promised a happy consummation; a great storm broke out, trees were uprooted, the earth was shaking and clouds of dust went up and hid the Sun and there was all-enveloping darkness. The reason for this strange phenomenon was Parashuram (the sworn enemy of Kshatriyas and an avatar of the God Vishnu, with a bow on one shoulder and a battle-ax on the other, and with an arrow shining like lightning in his hand). Parashuram made the shaking of the earth to show his power when he met Ram and started to get angry and took the form of deadly fire (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Evidences of earth (Earth) shaking found in Ramayana (Gyawali, 1997). Red rectangles refer to texts where exactly the word “Earth tremble” or “earth shaking” or “earthquake” is written (A–F). There are a few further evidences of earth shaking which we don’t include in this figure but which have similar explanation.

As explained in the Ramayana, Vali (the king of Kishkindha) was blessed with the ability to obtain half the strength of his opponent. To become the next King, there was a battle between Vali and his younger brother Sugriva. At the time, Ram was supporting Sugriva and shot an arrow to Vali and hit his head, then Vali has fallen on the ground by making the earth shake.

The earth tremble has been observed at the time of Ravana’s birth. The main story of Ramayana is the war between Ram and Ravana as Ravana had captured Sita, the wife of Ram for a long time. As Ram was going to Ravana’s palace, he didn’t see the sea and called the sea (Sagar) to ask the way, he didn’t see the sea and got angry. The earth has started to shake while looking at the angry Ram. In addition, a powerful monkey working for Ram (Hanuman) in Ramayana, was searching for Sita along with Ram and his brother Lakshmana, and he went to Ravana’s palace. The Rakshasas quaked and sent the news about the presence of a monkey in the palace to Ravana. The earth also quaked when Hanuman gave warning to Ravana for fighting with Ram. The earth was shaking during the war between Ram and Ravana, for example when Ram was getting angry with Ravana, when Ram applied divine arrow and got ready to attack Ravana, etc. (Figure 3).

In Mahabharata, some unusual natural occurrences are illustrated, including the signature of earthquakes. The process of churning of the ocean (Samundra Manthan) is described well; originally, Samundra Manthan churning is the process of making butter from milk. The churning continued to thousand years. The force of the churning was so great that the mountain began to sink and to shake. During this action, there was a rotation of mountain causing shaking of all living things in the mountains. This is a good example of earth shaking described in Mahabharata (p.13).

The action of falling trees on the ground and the ground being washed away are often presented in different incidents. In general, the Earth is reported to be shaking by different activities during fights between Gods and Danava. The earth has shaken when Bhim (a God holding an energy equivalent to a thousand of elephants in his body) and Jatasura (a Rakshasa) fight each-other (p. 150, 225), when Bhim beats Jeemut (p. 356), when Suyodhan felt to the ground hit by the Bhim’s main weapon (p. 949), when Danava’s headless trunk fell upon the ground (p. 142). It is written that the earth has shaken while Arjun showing martial arts to his elder brother Yudhishthira (p. 229); when Arjun fell in his chariot (p. 1166), when he moves on for fight (p. 350), when his chariot sounds harsh voice (p. 376), and when Arjun and Karan blow the conch shell in anger (p. 432, 814).

Thousands of Pandava’s soldiers are said to have been the cause of Earth tremble as they left for battle (p. 406). On the first day of the battle between the Pandava and the Kaurava, the Earth has shaken as the Lord and their armies advanced to fight (p. 686). Again, the violent sound of the army on both sides make earth tremble (p. 641). Weapons fired from both sides during the Mahabharata war have been described as flames in the sky and ground shaking (p. 973) (Vyasa, 1883). When a Danava (Asuras) lying covered with sands, wakes up and begins to breathe, then the whole Earth with her mountains, forests and woods begins to tremble. And his breath raised up clouds of sands, and shrouded the very Sun, and for seven days continually the earth tremble all over, and sparks and flames of fire mixed with smoke spread far around (p. 196) (Roy, 2011).

Some people believe that the festival of Diwali originated from the event of Samudra Manthan. When Goddess Kali killed a terrible demon, she began to jump and dance with joy at her victory, a massive earthquake occurrence and Lord Shiva coming to the rescue of human beings before things became worse are reported. An important and scientifically the most intriguing earthquake mention in Mahabharata is that people did know about the earthquake’s approach from the animal’s behavior preceding an earthquake (Vyasa, 1883).

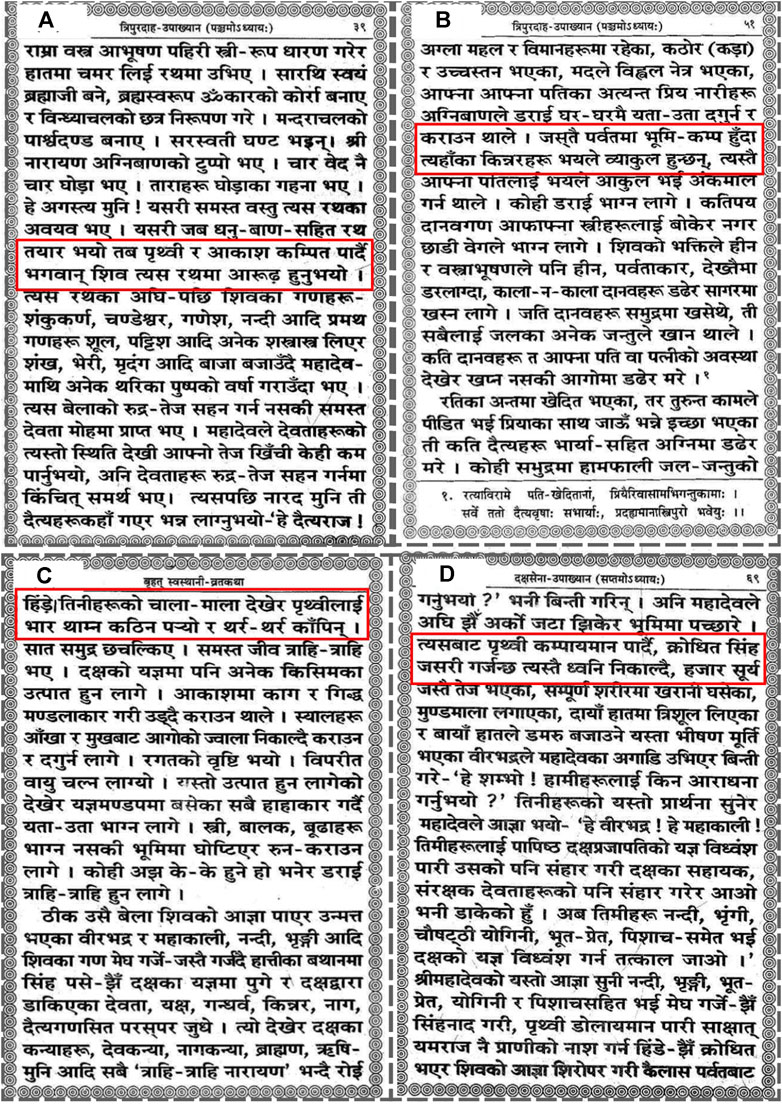

The Swasthani Brata Katha is mainly about Lord Shiva and his wives. At the time of the story, monster Tripurashur was hurting Gods and princes, and Lord Shiva agreed to kill him when he learned about this. The earth and sky have been reported to shake when Shiva sat in the specially designed carriage for the war. There was a more than 10,000 yr-long war with Tripurashur and by looking at the suitable time, Shiva set a divine arrow to hit him, which caused to earth to shake along with additional consequences like fire, flooding, etc. As per Swasthani Brata Katha, Lord Shiva had married Sati even though Sati’s father was not happy with that marriage. Once, Sati’s father had organized one of the grandest and greatest Yagna (worship). All the Gods and kings from all across the world were invited to attend except Shiva and Sati. Sati was surprised to see that there was no seat for Lord Shiva and her father further humiliated her husband, which led her to commit suicide by jumping in the fire of the Yagna. In the deep sorrow of Sati’s death, Lord Shiva plucked two hairs from his matted locks and has thrown them on the ground, where two Gods, Mahankali and Veerbhadra were created to take his revenge on Sati’s father, Dakshya Prajapati, because he was responsible for the self-immolation of Sati. While creating Veerbhadra, it is documented that the earth was shaking (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Evidences of earth shaking found in Swasthani Brata Katha (2020). Red rectangles is drawn to highlight the exact text where the word “earth tremble” or “earth shaking” or “earthquake” is written.

Since Veerbhadra and Mahankali were created to destroy Sati’s father, they were very strong and with extra power received from Lord Shiva. Shiva was angry and he ordered Veerbhadra to kill Dakshya Prajapati. When they were ready to move, the Earth couldn’t balance the weight of ferocious Veerbhadra and started to shake again. Along with the earth-shaking, there were waves in the sea and all living bodies were scared (Figure 1A).

Rig Veda explains that earthquakes happened when mountains flew over lands and then came to rest with a thud. Mostly, earthquakes have been explained as a consequence of the power of Rakshasa (devil) or power of the Gods (Wilson, 1997).

The 32nd chapter of Brihat Samhita focuses on the signs of earthquakes and their correlation with cosmic and planetary influences, underground water and undersea activities, unusual cloud formations, and the abnormal behavior of animals.

In Brihat Samhita, four types of earthquakes that can caused by four Gods have been described in detail. It is written that the Gods of wind, fire, heaven (Indra) and water will henceforth shake respectively to indicate the future good or bad condition of the world.

The precursory symptoms of an “earthquake of wind” are: the sky will be filled with dust and smoke; violent winds will shake the trees and the rays of the sun will appear dim. The result of this earthquake shows as: the crops will perish; the earth will become dry; forests will suffer; medicinal plants will be destroyed.

Early indications for an “earthquake of fire” are: the sky will be filled with the light of falling meteors and the appearance of a divine event into the sunset, and fire and wind will rage over the land. The consequences of such earthquakes are: the clouds will be destroyed; tanks and lakes will become dry.

Clouds like so many moving mountains (earthquake clouds), roaring, attended by lightning and black as the horn of a buffalo, as the bee and the black cobra, and yielding an abundance of rain are prior signs of an “earthquake of heaven.” Men of high caste and of high families, rulers and commanders of armies will perish because of its occurrence.

The preceding events for an “earthquake of water” are persons working at the sea or in rivers perishing; there will be excessive rain and rulers will cease to be hostile.

The effects assigned to earthquakes will occur within six months and a weighty lightning in two months. The earthquake brings the destruction of prominent kings if there is another earthquake on the 3rd, 4th, 7th day or at the end of the month, in 2 or in 6 wk. In an earthquake of wind, the shock will be felt at a distance of 1,600 miles; in one of fire, 880 miles; in one of water, 1,440 miles, and in one of heaven, 1,280 miles. This shows that an “earthquake of wind” is stronger compared to the others (Shastri and Bhat, 1947).

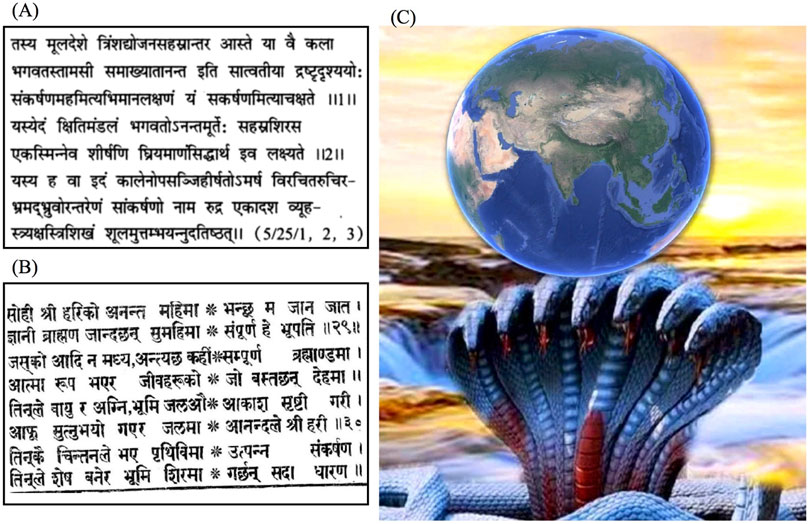

As referred to above, this book includes several different information on earthquakes and their causes. A first mention refers to God Vishnu, who shook the earth as he was yawning (possibly to go to bed to sleep). A second mention refers to elephants: when they breathe strongly, the earth shakes. Yet a third explanation for earthquakes is found in this source, referring to four different snake (Naag). According to Kashyap, there were four Naags who hold the Earth with the interest and permission of the God Vishnu, and when they get tired or one of them is weaker than the others, the Earth will be shaking. Another interesting story explaining earthquakes refers to flying mountains, and when God Indra cuts the arms of the mountains they stop moving. Another explanation is that the Earth is situated just above the sea, and mountains and forests are above the Earth; when sea creatures moves, the earth shakes. Garga says that earth tremors were due to the interaction of two strong winds which produced fire; this eventually impacted the oceans and shook the earth. Finally, falling different creations of Gods from the sky will also produce earthquakes according to the Surya. The Adbhuta Sagara also reports different earthquake effects, however those are not part of the focus of this article (Vallala, 1905).

In Puranas, some pieces of evidence have been found for earthquakes. During the birth time of Tarakasur, the world was affected by unpromising events like earthquakes, cyclones, etc. Also, when Siddhas and Charanas had provided a magnificent chariot to Indra so that Indra could fight with the demons, Indra was dashed against the ground with a great thump as a result of which the earth was shaken violently.

The way to get away from the different problems is given in chapter 263 of Agni Puranas. Every problem in the universe can be categorized in one of the following three types: money, space (the area outside the Earth’s atmosphere) and earth (ground). The problem of earthquakes is categorized in the earth related disaster type of problem. As earthquakes are defined as a problem, a solution to this problem is also written clearly. To do the earthquake Shanti, the worship must be performed by the people. If there is rain within a week of the earthquake, it is written that there will be no effect to the people afterward due to the earthquake, however, if there is no rain within a week and no worship has been performed by the people, then earthquakes could still be harmful for the people and the nation.

An overview of findings from primary sources are presented in Table 1.

While many ancient Hindu texts contain references to earthquakes, most of these are myths about this natural phenomenon related to other significant stories involving various Gods. However, Brihat Samhita and Adbhuta Sagara are two texts which contain some technical information on earthquakes comparable with modern concepts. In this section, we discuss the key information on earthquakes reported in the Hindu literature that have some direct, often physical explanation of the process.

As an example, comparable to natural science concepts, the answer to the question “Who had created the Earth” can be found in Bhagwat Gita. It is clearly written that the creation and the destruction of the Earth are possible by Gods. In addition, all-natural phenomena happening in this world are controlled by God. While these are similarly explained by some of the other religions as well, the comparison to concepts taught in science class is straightforward. For earthquake related topics, it is less so, simply because the process is less or not at all taught in middle or high school, especially in Nepal.

There are several reasons mentioned as the cause of an earthquake in Hindu literature. An earthquake is typically presented as a result of the action of Gods, however, the name of the God is distinct in different stories. The opinion of Kashyap is that earthquakes are due to the movement of sea creatures. Garga has the view that it is due to the sigh of elephants carrying the Earth, resting for a time from their labor which is written in Adbhuta Sagara. According to Vasishta, the interaction of two strong winds which eventually impact the oceans and shake the earth. The fourth opinion for the cause of the earthquake is that earthquakes can occur due to chance or unseen forces (see also in Iyengar, 1999).

The common explanation in Adbhuta Sagara and Brihat Samhita is that earthquakes were caused by flying mountains as they were frequently falling on the earth. With the request of the Earth, the God Indra cut the wings of the mountains and it is believed that the earth became stable. This is also explained in the Rig Veda. In earthquake science, the movement of mountains is documented as a consequence of plate tectonics but this is a result of earthquakes and not their cause.

In Brihat Samhita, Wind, Fire, Water, and Heaven are described in detail to cause the earth to shake. The cause of the earthquake is described also in Puranas. Accordingly, a strong Rakshasa called Dhundhu was alive under the sand and was so strong that even the Gods had been unable to kill. Dhundhu exhaled his breath once every year and this raises a massive cloud of sand and dust. The sun remained shrouded in dust and there were earthquakes as a result of his exhalation for an entire week. While among the four Elements listed above only Water seems to have a direct effect on earthquakes in modern science, this description of effects shows that the ancient Rishis and scholars had fairly realistic knowledge about the origin and consequences of earthquakes. For example, dust clouds from earthquake-triggered landslides have been reported to persist for several days in Switzerland in 1946.

Most Hindu people (including the first author) heard a tale in their childhood from grandfather or grandmother that the Earth is kept on the heads Sheshnaag, a giant snake with several heads, and that an earthquake occurs when Sheshnaag moves his heads. A part of this information is available in Mahabharata, Vedas, and Puranas literature.

In the Aadi Parva part of the Mahabharata, a dialogue between Brahman (the creator God in Hinduism) and Sheshnaag is presented. According to this, Brahman asked to Sheshnaag to carry properly and well this Earth so unsteady with her mountains and forests, her seas and towns and retreats, so that she (the Earth) may be steady. Following this request, Sheshnaag agreed to hold the Earth steady. In the meantime, Lord Ananta (king of Sheshnaag), of great prowess, came out to the sea to alone support the world at the command of Brahman (Adi parva, part 36).

In another part in Mahabharata, there is an explanation of the condition of the Earth, its origin, destruction and cataclysm. Lord Vishnu creates air, fire, land and water and sits in the water and carries the Earth on his head as Sheshnaag (p. 1085) (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5. The Earth is held by a Sheshnaag. (A) Explanation found in Purana in Sanskrit (Dwivedi, 2001). (B) Explanation found in Mahabharata in Nepali (Vyasa, 1883). (C) Schematic drawing of a seven-headed Sheshnaag supporting the Earth as explained in the text written in (A) and (B) (image modified after Sandeep, 2019).

A similar interpretation is also found in the Puranas: the whole Earth, which is kept on the head of the famous Sheshnaag named Ananta, seems like a grain of mustard. In the meantime, Dev (God) also sits on the head of Sheshnaag holding eleven military arrays. Sheshnaag has a speciality compared to other snakes: a jewel on its head (Dwivedi, 2001, Figure 5A). Therefore, when Sheshnaag moves his head, there is an earthquake (schematic drawing: Figure 5C). Knowing this information seems senseless in the first instance but it has a deep symbolic meaning like most of the stories mentioned in the Puranas, Vedas, and other Hindu scriptures. However, the occurrence of an earthquake based on the activities of Sheshnaag.

The most common belief for the cause of earthquakes in the Nepali communities is the change of arms of a Fish that carries the Earth. However, despite intense search, we could not find any document to support this oral tradition. Since Sheshnaag is described to live in the sea, the Fish and Sheshnaag could have been confused and might be presented in a similar frame, though with a different explanation. It is possible that in the past Sheshnaag was symbolically represented as the Fish, which would be the easiest way to make the descriptions and the story understandable.

There are different causes for earthquakes according to science, which we briefly discuss here. As explained by modern seismology, in most cases, the cause of an earthquake is plate tectonics and mechanical stress changes in Earth’s crust; therefore, most natural earthquakes happen along or near existing fault lines (Hetényi et al., 2018). However, there are also some earthquakes triggered by human activity that may occur far from the edges of tectonic plates. Recently, more than 700 sites for induced (human activity triggered) earthquakes have identified around the globe over the past 150 yr (Wilson et al., 2017). The most commonly reported human activities proposed to have induced earthquakes are by fluid injection during hydraulic fracturing (Clarke et al., 2014; Eaton et al., 2018), conventional oil production (Willacy et al., 2018), and groundwater extraction (González et al., 2012).

Some stories described in Hindu literature has shown actions that was followed by the God during the earthquake. For example, in the Puranas, when the wife of sage Shamik found the earth was shaking violently, she requested her husband to carry their son outside the hermitage so that he remains unharmed and said: “The astrologers say that whatever is kept outside the home during an earthquake becomes stable.” Sage Shamik followed her instructions and after the shaking of the earth had subsided, Shamik went outside and their son was fine (The Puranas, 2002). Going out of the house (if one is on the ground floor) and keeping away from buildings during an earthquake is also the modern advice given to people living in high earthquake hazard areas. Therefore, this story reported in the Puranas is a very nice illustration how practical, useful knowledge was already acquired in ancient times and reported in Hindu texts.

Building earthquake-resistant constructions alone is not enough for earthquake risk reduction, as the way people behave during an earthquake plays a very important role in minimizing casualties and corresponding losses.

In Nepal, eyewitness reported that children playing in the garden while the 2015 Gorkha earthquake occurred went into the house aiming to hide under the table (pers. comm.). It means that Nepali children assume “Hide under the Table” is the rule in case of an earthquake regardless where they are. However, this is incorrect, as there are very few earthquake-resistant houses in Nepal and staying outside is clearly safer. This is also referred to by the religious explanation, possibly reflecting old wisdom of the communities.

A number of foreshadowing for earthquakes including earthquake clouds are described in Brihat Samhita. Such behavior of clouds before the earthquake is studied also in modern science. In an example observed in Japan, while a common cloud was reported to move continuously, another cloud near the earthquake epicenter stayed stationary (Gup and Xie, 2007), although no causality (cause-to-consequence relation) was established.

Both Mahabharata and Brihat Samhita mention unusual behavior of animals before or during earthquakes. Such observations are still made in modern times, too, however they have proven to be unreliable signals in predict or signaling earthquakes. In many cases, earthquakes occurred without any warning sign from animals, and animals can behave strangely in times without earthquakes.

According to the Garga Samhita, traces of earthquakes are related to the Ketu (the descending lunar node in Hindu astrology) or dark spots on the Sun. Most of the earthquakes are felt either early in the morning or evening, although exceptions are also possible. It is also claimed that an earthquake may occur when a number of superior planets are in conjunction or in the same declinations or latitude. This is claimed to be verified by the case of the January 15, 1934 Bihar-Nepal earthquake, when seven planets have been reported to be located in the sign of Capricorn (Raman, 2007). The likelihood of earthquakes is higher during the full moon, particularly after midnight, and that is when the magnitude 6.2 Latur (India) earthquake occurred on September 30, 1993. It is noted that Earth is sensitive to the Sun’s rhythms. Earthquakes may occur due to disturbances in the Earth’s field force, which are brought about by incessant planetary motions (Raman, 2007).

According to Hindu sources (Raman, 2007), the planets deviate from their natural orbit when a solar eclipse or lunar eclipse occurs, and in such cases, there are higher chances of an earthquake to occur. Some examples of earthquake predictions are illustrated in the literature. As an example, on February 8, 2000 the 14th Dalai Lama, the main Buddhist religious leader, has announced India will face a devastating earthquake before February 2001 (Hogendoorn, 2014), which came to be true with the magnitude Mw7.7 earthquake on January 26, 2001, in Gujarat.

On the basis of astrology, many sources and people have predicted earthquakes publicly but it is not clearly mentioned whether these predictions were considered as reliable pre-information (Dwivedi, 2001) or not. Modern seismology considered these problems based on statistical analyses, and concluded that there is no clear link between planetary motions and earthquakes: while it is possible the minor stress changes in the Earth’s lithosphere from tides may help trigger already impending earthquakes, it is very unlikely that planetary effects directly cause seismic events that would not happen naturally within geologically short timescales (e.g. Heimisson and Avouac, 2020).

In the above research interesting information on earthquakes, their religious and historical contexts as well as physical causes have been gathered from Hindu literature, which are of direct use for teaching earthquake related topics at school. Our Seismology at school in Nepal program (Subedi et al., 2020a) is currently running in 30 schools in Central Nepal, and the program has already received very positive feedback showing that educational activities implemented at schools are effective in raising the awareness levels of children, promoting broader social learning in the community, and improving the adaptive capacities and preparedness for future earthquakes (Subedi et al., 2020b). One of the next objectives of the program is to reach more remote parts of the country, where earthquake education is not available at all, and where it is likely that traditional or religious beliefs are more widespread than in semi-urban areas or larger villages. Hence, especially in these rural regions, but also in more developed parts of the country, it is important for our program and involved school teachers to create a dialogue with local people who strongly believe in Hindu sources. Such a dialogue is more efficient if both parties are aware of enough information about earthquakes in Hindu literature. The interest here is not to oppose religious beliefs but to convey people the message what science gathered on earthquakes, their causes and consequences, and, especially, what are the good ways to improve local people’s preparedness. Such dialogues will not only enhance our earthquake communication skills with devout people, but will also open new opportunities to collect local, religious or even animistic beliefs and legends related to earthquakes.

We plan to implement the findings of this study in our future earthquake risk communication strategy in Nepal, and it can also be useful in other Hindu communities for example in India. The aim is not to convert people from Hinduism to other beliefs, but to provide an established base of comparison with scientific knowledge: whatever people think of earthquake causes afterwards, the level and quality of preparation is the main goal to reach for communities living under high earthquake hazard. The material will be available for educational trainings for teachers to enable them to continue to teach earthquake related topics to students, in a free and open access way through the educational program’s website (www.seismoschoolnp.org). We hope that the information reviewed in this study will be helpful for earthquake education in schools and so that the journey for earthquake preparation will be facilitated for the entire community.

The review of the main sources of Hindu literature for earthquake related text parts reveals many stories and explanations for the shaking of Earth in different stories throughout history. Some stories show the earth-shaking phenomena were described as long as 5,000 yr ago, which is long on the human memory timescale but still short on the geological timescale of 50 million years of Himalayan collision. At least five physically imagined causes of earthquakes are worth reporting here, ranging from flying mountains to the interest of a God to hold the Earth; yet none of these fit the modern seismological picture. At least one relevant and still valid practical advice could be found in ancient sources, namely that one should stay outside buildings during an earthquake. This makes sense also at present, especially if one is on the ground floor of a building that is not earthquake proof, which is often the case in Nepal (N.B.: if one is on a higher floor, it is better to hide under a strong table or doorframe). A few information on scientifically hot topics such as earthquake prediction were found, and explanations are presented either by the God’s statement or by observing some visible natural movements; however modern seismology provides no support for such predictions.

The baseline conclusion is that in the Hindu religious context, God creates the Earth and only God is responsible to create and destroy the Earth. The power of Gods has been found to be described as the cause of earth tremble or shaking in many occasions. Hence, it is expected that part of the population in Nepal still has religious concepts to explain earthquake phenomena. Our educational seismology project aims to bring modern ideas to the Nepali population at risk, yet conveying such information goes better in form of dialogue (rather than top-down teaching), for which it is very important to know the religious views on earthquake related questions. We conclude that although stories, causes, and explanations of earth-shaking mentioned in Hindu literature mostly do not match with the theory of modern science, the collected findings are important to develop a more efficient and appropriate strategy to communicate about earthquake related topics in the classroom as well as with the public. This has to consider the prior beliefs of students and their families, and, more generally, the cultural – here mainly religious – context of the group to receive knowledge from a scientific background.

All texts in Nepali and Sanskrit are compiled and translated in English by SS and verified by GH. Both authors discussed the results, and contributed to the final manuscript equally.

The authors acknowledge the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number PP00P2_187199).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We greatly acknowledge the Institute of Earth Sciences and the Faculty of Geosciences and Environment at the University of Lausanne. We are very thankful to Pundit Dinbhandhu Pokhrel for a long discussion about Hindu texts and earthquakes. Thanks to Narayani Dekvkota (Saraswati Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University), Narayan Paudel (Myagdi Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University), Shreedhar Dhakal for their assistance in Sanskrit Translation. We are particularly thankful to all teachers and students from the Nepali schools for their enthusiastic participation in the Seismology at School in Nepal program. We don’t want to forget the contribution of many authors who wrote or/and translate Hindu literature in different languages.

Ablonczy-Mihalyka, L. (2015). “Cross-cultural Communication Breakdowns: Case Studies from the Field of Intercultural Management,” in Proceedings of International Academic Conferences, London, September 2015 (London, UK: International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences).

Bilham, R. (2019). Himalayan Earthquakes: A Review of Historical Seismicity and Early 21st century Slip Potential. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publications 483 (1), 423–482. doi:10.1144/sp483.16

Birdwhistell, R. L. (2010). Kinesics and Context. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Birkenholtz, J. L. V. (2010). The “Svasthānī Vrata Kathā” Tradition: Translating Self, Place, and Identity in Hindu Nepal. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Brown, W. S. (2021). Successful Strategies to Engage Students in a COVID-19 Environment. Front. Commun. 6, 52. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.641865

Clarke, H., Eisner, L., Styles, P., and Turner, P. (2014). Felt Seismicity Associated with Shale Gas Hydraulic Fracturing: The First Documented Example in Europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41 (23), 8308–8314. doi:10.1002/2014gl062047

Dahal, G. (2019). Gita Philosophy and its Influence on Nepali Politics. Tribhuvan Univ. J. 33 (1), 167–178. doi:10.3126/tuj.v33i2.33607

Deetz, S. (1996). Crossroads-Describing Differences in Approaches to Organization Science: Rethinking Burrell and Morgan and Their Legacy. Organ. Sci. 7 (2), 191–207. doi:10.1287/orsc.7.2.191

Eaton, D. W., Igonin, N., Poulin, A., Weir, R., Zhang, H., Pellegrino, S., et al. (2018). Induced Seismicity Characterization During Hydraulic‐Fracture Monitoring with a Shallow‐Wellbore Geophone Array and Broadband Sensors. Seismological Res. Lett. 89 (5), 1641–1651. doi:10.1785/0220180055

González, P. J., Tiampo, K. F., Palano, M., Cannavó, F., and Fernández, J. (2012). The 2011 Lorca Earthquake Slip Distribution Controlled by Groundwater Crustal Unloading. Nat. Geosci 5 (11), 821–825. doi:10.1038/ngeo1610

Gup, G., and Xie, G. (2007). Earthquake Cloud over Japan Detected by Satellite. Int. J. Remote Sensing 28 (23), 5375–5376. doi:10.1080/01431160500353890

Gyawali, S. (Editors) (1997). Bhanubhaktako Ramayana. 2nd Edn. (Darjeeling: Nepali Sahitya Sammelan).

Heimisson, E. R., and Avouac, J. P. (2020). Analytical Prediction of Seismicity Rate Due to Tides and Other Oscillating Stresses. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090827. doi:10.1029/2020GL090827

Hetényi, G., Epard, J.-L., Colavitti, L., Hirzel, A. H., Kiss, D., Petri, B., et al. (2018). Spatial Relation of Surface Faults and Crustal Seismicity: A First Comparison in the Region of Switzerland. Acta Geod Geophys. 53 (3), 439–461. doi:10.1007/s40328-018-0229-9

Hogendoorn, R. (2014). Caveat Emptor: The Dalai Lama's Proviso and the Burden of (Scientific) Proof. Religions 5 (3), 522–559. doi:10.3390/rel5030522

Iyengar, R. N. (1999). Earthquakes in Ancient India. Curr. Sci. 77 (6), 827–829. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24102701 (Accessed February 10, 2021).

Kak, S. (2000). On the Chronological Framework for Indian Culture. Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, LA: Indian Council of Philosophical Research, 1–24.

Kelly, S. E., and Westerman, D. K. (2016). 18. New Technologies and Distributed Learning Systems. Commun. Learn. 16, 455–480. doi:10.1515/9781501502446-019

Kelly, S., and Westerman, D. (2020). Doing Communication Science: Thoughts on Making More Valid Claims. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 44 (3), 177–184. doi:10.1080/23808985.2020.1792789

Klostermaier, K. K. (2007). A Survey of Hinduism. 3rd edn. (New York, NY: Suny Press). 978-0-7914-7082-4.

Leonard, K. M., Van Scotter, J. R., and Pakdil, F. (2009). Culture and Communication. Adm. Soc. 41 (7), 850–877. doi:10.1177/0095399709344054

Mumby, D. K. (1988). Communication and Power in Organizations: Discourse, Ideology, and Domination. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Nakarmi, A. (2019). “Security Amplified for the Salinadi Fair”. Nepalbuzz.Com. Available at: https://nepalbuzz.com/news-events/security-amplified-for-the-salinadi-fair/ (Accessed February 6, 2021).

Oldham, R. D. (1899). Report of the Great Earthquake of 12th June, 1897. Calcutta: Office of the Geological Survey.

Penna, L. R. (19891961-1997). Written and Customary Provisions Relating to the Conduct of Hostilities and Treatment of Victims of Armed Conflicts in Ancient India. Int. Rev. Red Cross 29 (271), 333–348. doi:10.1017/s0020860400074519

Prabhupada, A. B. S., and Swami, B. (1972). Bhagavad-Gita as it Is with the Original Sanskrit Text, Roman Transliteration, English Equivalents, Translation, and Elaborate Purports. Los Angeles, CA: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

Raman, B. V. (2007). Astrology in Predicting Weather and Earthquakes. New Delhi, India: BVR Astrology Series Publications.

Ribeau, S. A. (1997). “How I Came to Know ‘in Self Realization There Is truth,” in Our Voices: Essays in Ethnicity, Culture, and Communication. 2nd Edn, Editors A. HallGonzalez, M. Houston, and V. Chen (Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury), 21–27.

Roy, P. C. (1958). The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text. 2nd Edn, Calcutta: Oriental Publishing, Vol. 12. Available at: https://holybooks.com/mahabharata-all-volumes-in-12-pdf-files/ (Accessed February 6, 2021).

Sandeep, C. (2019). Sheshnaag – Snake or Human? (Online Image). Available at: https://astrotalk.com/astrology-blog/sheshnaag-snake-or-human/ (Accessed February 6, 2021).

Satpathy, B., and Muniapan, B. (2008). The Knowledge of “Self” from the Bhagavad-Gita and its Significance for Human Capital Development. Asian Soc. Sci. 4 (10), 143–150. doi:10.5539/ass.v4n10p143

Shastri, P. V. S., and Bhat, V. M. R. (1947). Varahamihira’s Brihat Samhita with an English Translation and Notes. Bangalore: V.B. Soobbiah and Sons.

Shree Swasthani Brata Katha (2020). A Festival about Fasting, Reading, Discipline. Kathmandu: Ratna Books.

Stevens, V. L., and Avouac, J. P. (2015). Interseismic Coupling on the Main Himalayan Thrust. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42 (14), 5828–5837. doi:10.1002/2015gl064845

Subedi, S., Hetényi, G., Denton, P., and Sauron, A. (2020a). Seismology at School in Nepal: A Program for Educational and Citizen Seismology through a Low-Cost Seismic Network. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 73. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.00073

Subedi, S., Hetényi, G., and Shackleton, R. (2020b). Impact of an Educational Program on Earthquake Awareness and Preparedness in Nepal. Geosci. Commun. 3 (2), 279–290. doi:10.5194/gc-3-279-2020

Subedi, S., Hetényi, G., Vergne, J., Bollinger, L., Lyon‐Caen, H., Farra, V, et al. (2018). Imaging the Moho and the Main Himalayan Thrust in Western Nepal with Receiver Functions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45 (24), 13222–13230. doi:10.1029/2018gl080911

The Puranas (2002). A Compact, English-only Version of the Major 18 Puranas, Compiled by the Dharmic Scriptures Team.

Vallala, S., Sagara, A., text, S., and Muralidhar, S. (1905). Pandita Murali Dhara Jha Jyotishacharya. (Benares: Prabhakari & Co).

Vatsyayan, K. (2004). “The Ramayan Fi a Theme in the Visual Arts of South and Southeast Asia,” in The Ramayana Revisited. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 335.

Vyasa, K-D. (1883). The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Originally Published between 1883 and 1896. (Calcutta: Bharata Press). Available at: https://www.dwarkadheeshvastu.com/Epic-Mahabharat-Sampoorna-18-Parva-Nepali.aspx (Accessed February 6, 2021).

Wilkins, C. (2008). The Bhagvat-Geeta or Dialogues of Kreeshna and Arjoon. London: BiblioBazaar, LLC.

Willacy, C., van Dedem, E., Minisini, S., Li, J., Blokland, J. W., Das, I., et al. (2018). Application of Full-Waveform Event Location and Moment-Tensor Inversion for Groningen Induced Seismicity. The Leading Edge 37 (2), 92–99. doi:10.1190/tle37020092.1

Wilson, H. H. (1997). Rig-Veda-Sanhitā: A Collection of Ancient Hindu Hymns. London, UK: Cosmo Publications.

Keywords: earthquake, Hindu, religion, communication, Nepal

Citation: Subedi S and Hetényi G (2021) The Representation of Earthquakes in Hindu Religion: A Literature Review to Improve Educational Communications in Nepal. Front. Commun. 6:668086. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.668086

Received: 15 February 2021; Accepted: 14 June 2021;

Published: 16 July 2021.

Edited by:

Douglas Ashwell, Massey University Business School, New ZealandReviewed by:

Uttaran Dutta, Arizona State University, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Subedi and Hetényi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shiba Subedi, c2hpYmEuc3ViZWRpQHVuaWwuY2g=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.