- 1Department of Linguistics, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, United States

- 2Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, United States

- 3Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, United States

This paper investigates the body’s role in grammar in argument sequences. Drawing from a database of public disputes on language use, we document the work of the palm-up gesture in action formation. Using conversation analysis and interactional linguistics, we show how this gesture is an interactional resource that indexes a particular epistemic stance—namely to cast the proposition being advanced as obvious. In this report, we focus on instances in which participants reach what we refer to as an ‘impasse’, at which point the palm up gesture becomes a resource for reasserting and pursuing a prior position, now laminated with an embodied claim of ‘obviousness’ that is grounded in the sequentiality of the interaction. As we show, the palm up gesture appears with and in response to a variety of syntactic and grammatical structures, and moreover can also function with no accompanying verbal utterance at all. This empirical observation challenges the assumption that a focus on grammar-in-interaction should begin with, or otherwise be examined in relation to, ‘standard’ verbal-only grammatical categories (e.g., imperative, declarative). We conclude by considering the gestural practice we focus on alongside verbal grammatical resources (specifically, particles) from typologically distinct languages, which we offer as a contribution to ongoing discussions regarding an embodied conceptualization of grammar—in this case, epistemicity.

Introduction

Arguments are an inevitable part of the human social experience. As Antaki (1994) summarizes:

Social life is argumentative; and what moves an argument along is social: the topics people argue over, the content of the challenges and rebuttals, and so on. People argue about categories and particulars—what something is, and what implications you can draw from it; they argue over definitions, terms and usages (160).

The present study examines arguments that arise in a particular social setting, namely in the context of individuals being targeted and harassed for speaking a language other than English in public in the United States. As will be seen in the data presented here, such harassment often results in a series of argumentative moves back and forth between challenger, target, and occasionally bystanders as well1. The issues debated in these arguments range from the “legality” of speaking a language other than English, to whether or not such language-based discrimination constitutes racism, even to the very nature of what America and being an American “means”. While the specific topics debated vary from encounter to encounter, across these individual instances, challengers, targets, and bystanders are demonstrably engaged in arguments, taking oppositional stances (Du Bois 2007; Du Bois and Kärkkäinen 2012) from one another on a moment-by-moment basis in the interaction.

Prior research has revealed a range of devices that can be used to construct actions as argumentative or oppositional in context. With regard to grammar, specifically, many of these practices are best conceived of as examples of what Goodwin (1990) has called “format-tying”, wherein participants make strategic use of the structures of prior utterances (e.g., their syntax or prosody) to construct new utterances that are thereby “publicly available” (12) as tied to that prior talk, as some transformation thereof (see, e.g., Corsaro and Maynard 1996; Goodwin 2006, 2018). Devices for format-tying include, for example, the incorporation of negation and other polarity markers (Boggs 1978; Goodwin 1982; Halliday and Hasan 1976:178; Raymond and Stivers, 2016), shifting deictic terms (Goodwin 1990), as well as the use of imperatives that re-employ prior syntactic formats (Goodwin, 2002). And indeed, examples of such practices are readily observable in the argumentative data under analysis here.

In extract (1), for instance, a challenger twice responds to the assertion “that’s ra:cist” (line 49) with its negated equivalent: “It’s <↑no:t racist>“, followed by a repeat “it’s not racist” (lines 50–51).

And in the following case (2), we see the incorporation of negation, as well as shifts in deictic references: “She” and “me” from line 17 shift to “I” and “you” in line 20, and the challenger also reuses the same syntactic format. With this, the challenger rejects the assertion that what she is doing is categorizable as “harassing”.

These instances also illustrate how prosodic delivery—e.g., on “<↑no:t>” (example 1, line 50) and “you::.” (example 2, line 20)—can likewise figure into designing utterances as format-tied to a prior, including features such as pitch leaps, vowel lengthening, raised volume, and particular intonational contours (Goodwin 1998; Goodwin et al., 2002). These various grammatical resources for format-tying are deployed in their local sequential contexts so as to construct prior talk as “arguable”—that is, as containing “objectional features” (Maynard 1985:3) that are constituted as such through the subsequent action (e.g., a disagreement, a counter, etc.).

As might be expected given the verbal bias in much linguistic and interactional inquiry (see Keevallik 2018), the vast majority of research on grammatical resources for maintaining opposition in arguments focuses on verbal resources of the sort cited thus far. This may additionally be influenced by the fact that many studies, as Maynard (1988) notes, emphasize “semantic continuity” as in some way criterial for their operationalization of “opposition”, thereby categorically neglecting any and all oppositional actions accomplished nonverbally (23). And while research by the Goodwins—e.g., on embodied replays (Goodwin 1998), embodied affective stances (Goodwin, 2002), and pointing practices (Goodwin 2003)—has certainly illustrated the import of gestural resources in argumentative contexts, verbal resources continue to dominate discussions as far as grammar is concerned. Particularly in light of the growing body of research on the complex interplay between grammar and the body (e.g., Fox and Heinemann 2015; Keevallik 2018, 2020; Li 2019; Mondada 2014; Pekarek Doehler 2019; Ford et al., 2012; Raymond, et al., 2021), more systematic consideration is called for concerning how verbal and gestural resources are deployed so as to produce actions that are understood, in context, as oppositional.

In this paper, we focus on a particular gesture that is recurrently used in the arguments in our data—namely, a supine, palm-up, open-arm, lateral gesture, which, as we will show, may or may not be produced concurrently with a verbal utterance. Building on work by Kendon (2004), Shaw (2013), and Clift (2020), we propose that this gesture is among the resources for displaying stance in argumentative contexts, in particular an epistemic stance of obviousness. The paper is organized as follows: After a brief description of the data relied upon for the present study, we begin by describing our collection-building process, underscoring the import of sequential position in examining the gesture’s contribution to ongoing trajectories of action. We then demonstrate the routine use of our target gesture and discuss what this embodied resource accomplishes in the immediacy of interaction. We conclude by considering the gestural practice we focus on alongside verbal grammatical resources—namely, particles—from typologically distinct languages, which we offer as a dimension of cross-linguistic evidence in favor of an embodied conceptualization of epistemicity in grammar.

Data: The Corpus of Language Discrimination in Interaction

Maynard (1985) writes that “the arguable property of an utterance or action, as made evident in a disagreement move, lies in the purported breaking of some rule” (19). In the data drawn on for the present study, the key arguable property is breaking the “rule” that only English should be used in public spaces in the United States. While of course no such “rule” or “law” exists in the U.S.—and indeed the U.S. does not even have a de jure official language at the federal level—the hegemonic and de facto ‘official’ status of English is recognizable in that speakers of languages other than English are routinely cast as “un-American” in various ways, and through various intersecting discourses and ideologies (see, inter alia, Anderson 1983; Baugh 2017; Bonfiglio 2002; García 2014; Lempert and Silverstein 2012; Lippi-Green 2012; Santa Ana 2002; Silverstein 2015, 2018; Zentella 1995, 2014). In the encounters we examine in this study, a “challenger” in some way takes issue with a “target” for the target’s use or endorsement of a language other than English (LOE) in a public place, such as a store or restaurant. In this corpus, the LOE is frequently Spanish, though other languages are targeted as well. Despite the fact that in many cases the target was demonstrably not speaking the LOE to the challenger, and indeed the challenger was an overhearer (Goffman 1981), the challenger nonetheless inserts themselves into the target’s/s’ interaction, the account for which being that the target is breaking the “rule” of what language “should” be used publicly. In this way, the challengers not only interactionally claim to know about this “rule” (thus enacting an epistemic stance; see Heritage 2013), but they also simultaneously claim the authority to determine how that rule applies to the target and their conduct (thus enacting a deontic stance; see Stevanovic and Peräkylä 2012). The arguments that then ensue, which form the basis for the present analysis, are the result of targets and bystanders engaging with these challengers and their claims, and thus with the epistemic and deontic stances that these challengers have “talked into being” (Heritage 1984a:290).

These arguments, and the data for this study, come from a growing, publicly accessible online corpus of videos, the Corpus of Language Discrimination in Interaction (CLDI), in which targets are challenged for speaking a language other than English in public (Raymond, et al., in prep). The ubiquity of cell phones and social media has created a new genre of online viral video in which people video-record public interactions and post them online, allowing us to capture and examine precisely these sorts of spontaneously occurring social activities which have thus far largely evaded systematic interactional inquiry (but see Reynolds 2011, 2015, discussed below).

It bears mention that the use of this type of data is not without its limits. For example, videos are usually recorded on cellphones or security cameras, which does not always result in the highest-quality images, or consistently capture each participant in frame2. In addition, the majority of these videos begin after the argument is already underway, as it is typically the launch or an escalation of the confrontation that itself provides the impetus for someone to then begin recording the encounter (cf. Sacks 1986)3. Despite these limitations, however, the corpus as a whole provides a close-up look at what is a very real experience for many members of U.S. society as they speak languages other than English in public spaces4. These confrontations offer a unique window into the (re)production of norms and ideologies about language, race, and social life in the United States (see Hill 2008; Lippi-Green 2012; Alim 2016; Rosa and Flores 2017; Rosa 2019), allowing us to examine these and other intersections as they manifest themselves in the details of moment-by-moment social interaction (see Raymond, et al., in prep).

The extracts reproduced here were transcribed according to Jefferson (2004) conventions, while also drawing on Kendon (2004), Hepburn and Bolden (2017), and Mondada (2018) guidelines for representing gestural and visual practices.5 Images of the video data are included to show the most complete picture possible of the gesture in question.

The data were examined using Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics, which emphasize the analysis of collections of exemplars (for overviews, see Clift 2016; Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018, respectively). In the next section, we describe the collection-building process for the present study.

The Supine, Palm-Up, Open-Arm, Lateral Gesture in Context

Gestures are often divided into two main classifications, interactive and representational. Interactive gestures manage dialogue, such as by navigating turn-taking (Abner et al., 2015), and have also been labelled pragmatic, illocutionary, or discourse gestures (Kendon 2004). Representational gestures focus more on the content at hand, and include topic, deictic, iconic, metaphoric, and emblematic gestures (i.e., McNeill 1992). However, gestures often cross categorical boundaries (Kendon 2004; Enfield 2009), thereby making explicit categorization difficult.

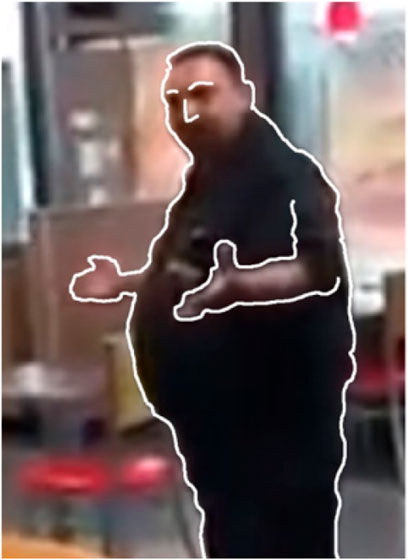

In this study, we focus on one of a family of gestures that continues to be, in many ways, “puzzling” (Cooperrider, et al., 2018:14)—specifically, a supine, palm-up, open-arm, lateral gesture, which may or may not be produced concurrently with a verbal utterance. An example of the gesture is shown in Figure 1, with the shape of the body outlined to better visualize the gesture, which we will do in all the figures we present.

Streeck (2009, 2017) argues that such palm-up, open arm gestures originally derive from object transfer, such as presentations, offerings, or hand-overs. Following this, Andrén (2017) has studied how children manipulate objects in tandem with open-arm movements. In the greater gesture landscape, Chu et al. (2014: 700) show that variants of the palm-up are common amongst English speakers, with palm-revealing gestures accounting for 24% of over 8,000 gestures produced. “And yet,” as Cooperrider et al. (2018) summarize, “palm-ups remain puzzling. They vary considerably from one use to the next, even in sign languages; they go by different labels; they resist current gesture classification schemes and elude existing linguistic categories” (14). If palm-up gestures are so pervasive (in our dataset as well) and at the same time so varied, with little consensus on the origin of the gesture and its physical boundaries, how might we operationalize their study in interaction, and in particular in the argumentative contexts we investigate here?

Clift (2020) describes the core practice of what she calls the “palm-up” (PU) gesture as a “…rotation of the palms upwards or outwards towards the recipient, with—if standing—a raise of the arms outwards away from the body. These are then momentarily held static in parallel, iconically displaying a temporary halt to the progressivity of the interactional sequence” (204), as seen in Figure 1 (see also Kendon 2004; Müller 2004). As Clift (2020) observes, “where PU [palm-up] producers are standing, there is a lift of the arms away from the body to about mid-body or waist height” (191). There appears to be some variation in the naming of this particular gesture: Kendon (2004) refers to it as “palm up open hand,” while Müller (2004) refers to it as “palm up open arm.” In this paper, we will follow Clift in referring to the gesture as “palm up” or PU, though specifically, the PUs under consideration here are supine and two handed,6 produced while standing, without noticeable shoulder shrugging (see the discussion below regarding shrugs).

As we explored the data, the first author noticed that PUs seemed to be employed recurrently as embodied resources in this collection of public arguments. We then began to collect PUs broadly in the dataset, whether one-handed or two, standing or seated, and so on. Although of course all of the data are constrained to the argumentative contexts of the CLDI Corpus, collecting broadly in this way allows the researcher to, for example, explore potential environments of relevant possible occurrence, to examine (what may turn out to be) boundary cases of the practice or phenomenon in question, and to identify local, situation- and context-specific particulars of the practice’s deployment (see Clift & Raymond 2018; Mondada 2014; Schegloff 1996, 1997). Moreover, in analyses of multimodal phenomena, this process ensures that the verbal channel is not inappositely prioritized in the building of the collection (see Mondada 2014; Floyd 2016; Streeck 2018). This procedure generated an initial collection of 45 instances7.

Mondada (2018) and Clift (2020) underscore the import of sequence organization (Schegloff 2007) in refining and analyzing a collection of exemplars that exhibit the use of a particular gesture. As Mondada puts it, “the meaning of a movement is not reducible to its form but is related to the moment in which it is produced; a moment that is meaningful in relation to its sequential environment and its position in ongoing action” (Mondada, 2018:91). It is thus through consideration of a gesture’s deployment within a sequence or trajectory of actions that researchers are able to link the particulars of the gesture to the particulars of action.

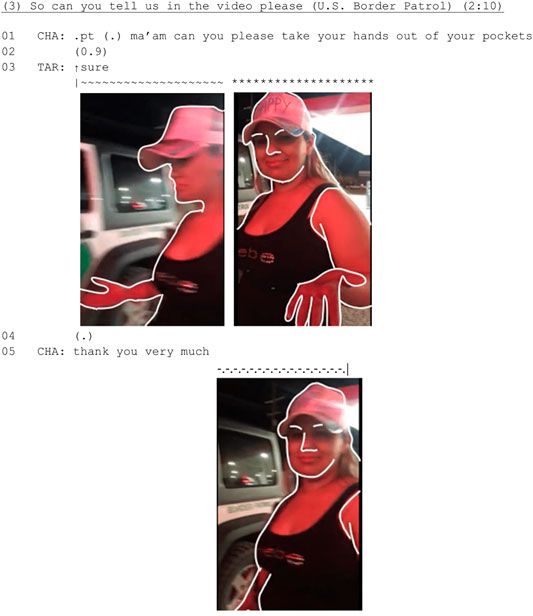

As we began a case-by-case analysis of our collection of palm-up gestures, this became immediately evident in that ostensibly the “same” gesture performed demonstrably distinct interactional work in different sequential contexts. For example, it became relevant to distinguish our focal gesture from ‘shrugs’, which may include the PU but additionally incorporate raised shoulders (on which, see Debras 2017; Jehoul et al., 2017; Kendon 2004; Streeck 2009) and perform demonstrably different actions (for example, in response to a request for information). In the same vein, consider the following case (3), in which an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officer asks a woman to take her hands out of her pockets, and she obliges, producing a palm-up gesture.

In these video stills, the gesture looks quite similar in form to other examples of a PU gesture, such as that in Figure 1 and the other examples we will examine below. However, in its sequential context, the palm-up gesture here accomplishes an action that is altogether distinct from that which we focus on in the remainder of the analysis. Here, the PU gesture is produced in response to the officer’s directive in line one to take her hands out of her pockets; the gesture thereby constitutes a bodily enactment of compliance with an ICE officer’s directive—a directive which is produced and understood as an instruction not only to remove her hands from her pockets, but to do so and also make visible that she has nothing threatening to the officer in her hands.

Specifically, here we focus on the PU gesture in the construction of what are, in their local sequential context, oppositional actions—that is, actions that counter, disagree with, or otherwise construct as “arguable” (Maynard 1985) some prior talk or action by another participant. In this way, we see PUs as part of complex multimodal gestalts (Mondada 2014, 2016)—assemblages that “build emerging and changing positionings between the participants, whose relations, actions, and the rights and obligations related to them, are negotiated not only in discursive but also in embodied ways” (Mondada 2016:344). But of course the data we are examining are riddled with argumentative actions; so, among the various oppositional, multimodally constructed actions in these confrontational interactions, at what points are assemblages with PU gestures produced, and what does their deployment accomplish in the immediacy of the in-progress argument?

Arriving at an Impasse

In the data in the Corpus of Language Discrimination in Interaction, we recurrently find the palm-up gesture in the construction of particular oppositional actions, namely those delivered in the context of what we will refer to as an ‘impasse’.8 What we aim to capture with the use of this term is that the participants have arrived sequentially at a point where each has committed to a position in the argument, neither is conceding or backing down, and importantly, those positions betray incompatible views of reality (e.g., It’s illegal → It’s not). Upon arriving at this sort of demonstrable ‘reality disjuncture’ (Pollner 1975, 1987), one way that participants proceed is by pursuing a line of action and stance that they themselves already committed to (see Clift 2020:195–9). It is in this sequential environment that we regularly find use of the PU gesture in our dataset.

Shaw (2013:250) argues that the open-hand, palm-up gesture can be a resource to evaluate prior talk, or in other words, display stance. Drawing on this and Kendon (2004), we argue that the PU gesture indexes an epistemic stance in relation to the action being committed—namely, marking the proposition as obvious or redundant, about which “nothing further can be said” (Kendon 2004:265)9 In the cases presented here, participants leverage the sequentiality of interaction as the source of the ‘obviousness’ or ‘redundancy’: By taking the stance that the action they are producing should at this moment be ‘obvious’, the gesturer sequentially categorizes the recipient’s prior conduct as having been unsuccessful in terms of the action it was designed to implement. The gesture turn thus operates not only on the prior, but also holds the interlocutor accountable for the divergent stances that have emerged over the course of prior talk, resulting in a ‘reality disjuncture’ or ‘impasse’. It is in this way that the gesture serves not as simply a pursuit of a prior stance, but as one that highlights the persistence of pursing this stance in the face of the recipient’s attempts to counter it. Gesturers thereby come off in context as enacting having ‘won’ this point of the argument by pushing for sequence closure—“nothing further can be said”. The present analysis thus allows us to both ground and particularize ‘obviousness’ in the sequentiality of interaction, as a participants’ category and resource for the design and interpretation of action.

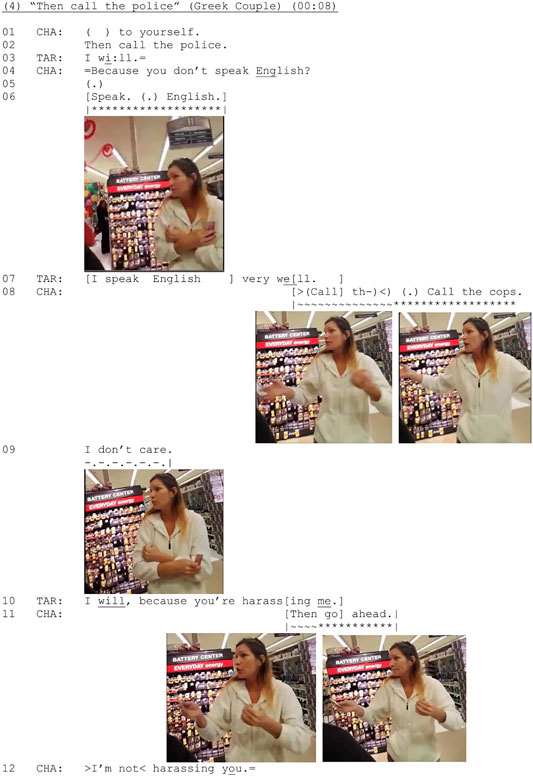

Consider example 4) below. Here, in the midst of one confrontation, the challenger directs the target to “call the police” (line 2), offering as an account “because you don’t speak English?” (line 4). In response, the target expresses that, in fact, she “speak[s] English very well.” (line 7), which both claims as well as demonstrates (Sacks 1992) the logical inappositeness of the challenger’s stated view of reality. By extension, this move by the target aims to reject what that version of reality was intended to convey in terms of action: Her inability to speak English cannot serve as a legitimate account for the challenger to call the police, because in fact she speaks English very well. It is in the context of this exposed reality disjuncture that the challenger then reissues her directive, this time with a PU gesture (line 8).

Here, the target’s line 7—“I speak English very well”—is delivered so as to undermine the challenger’s initial account for endorsing the idea of calling the police and to expose the reality disjuncture between the two parties. In reissuing her directive to “Call the cops” in the context of this counterevidence, the challenger incorporates a PU gesture (line 8). This embodied practice laminates a stance of obviousness onto the pursuit action in that it insists on the enduring relevance of her initial action in the face of the target’s attempt to counter it. In this way, the target’s attempt at issuing a counter is cast as unsuccessful, thereby pushing for closure of this particular point within the argument. The challenger’s turn-final “I don’t care” (line 9) likewise works to frame this as a point about which “nothing further can be said” (Kendon 2004:265).10

In this case, though, the target does not acquiesce to the challenger’s push for sequence closure, but rather works to get the last word in herself with an agentive “I will,”, before continuing to issue an account of her own, “because you’re harassing me” (line 10). Prior to this account being brought to completion, though, the challenger again pursues her own same action trajectory with “Then go ahead.”, and again producing the PU gesture. We therefore have a second use of our focal practice in this sequence. As in line 8, the PU gesture in line 11 enacts a stance of obviousness by presenting the relevance of this action as enduring and self-evident from the interaction thus far. In this second case, the challenger immediately extends her turn to counter the target’s new account/accusation of ‘harrassment’; notably, though, she releases the PU gesture with the onset of this new unit, thereby illustrating the relevance of the gesture specifically to the pursuit action of line 11.

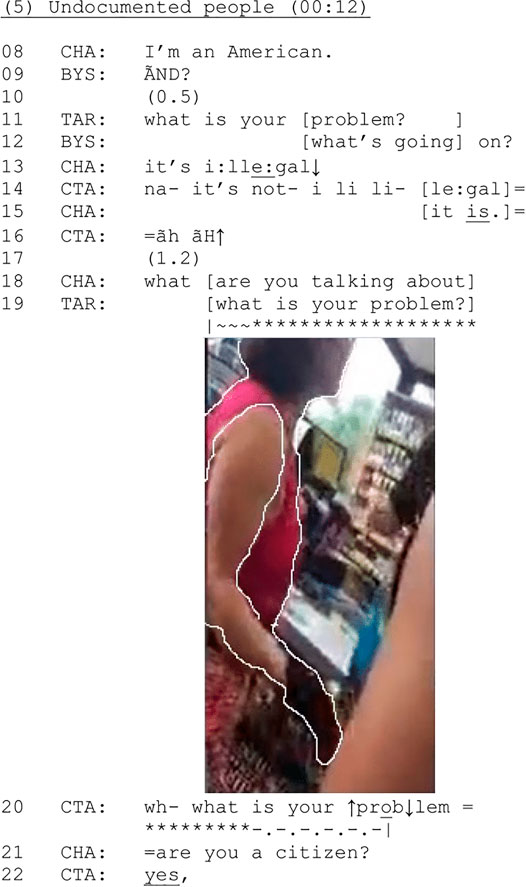

Consider a similar instance in (5), in which claims of legality are again challenged. Here, the challenger is a gas station employee standing behind the counter, and the target is the customer in the pink shirt. A co-target is not seen on screen, but her voice is audible (identified as “CTA” in transcript). In this case, the target addresses the challenger’s earlier claims about speaking a LOE in public with “What is your problem” (line 11). This turn may at some level be interpretable as an account solicitation, but its deployment in the dispute relies on categorization of the recipient (here, the challenger) as the one with a “problem” and thereby at fault for the present discord; the turn thus expresses an accusation in addition to whatever account-soliciting work it may also be doing (see Clayman and Heritage 2002; Bolden and Robinson 2011; Couper-Kuhlen and Thompson, frth.). The challenger responds by citing as his account that speaking a LOE in public is “i:lle:gal↓” (line 13). The co-target immediately disagrees in line 15, incorporating negation, but the challenger reasserts his stance with “it is.” (line 15) in overlap. Latched to this overlapped reassertion is the co-target’s production of nasalized “ah” vowels, produced in the form of a response cry (Goffman 1978) to enact further disagreement with the challenger’s stance. At this sequential impasse of whether speaking a LOE in public is, or is not, illegal, marked with a 1.2-s silence (line 17), we see the target produce a PU-accompanied utterance in overlap, reissuing “what is your problem?” (line 19).

At line 16, as the co-target produces the nasalized ahs, the target brings up her arm as if to point, but quickly abandons this gesture with the onset of the challenger’s turn. She then produces the PU gesture while reissuing her earlier action “what is your problem” (line 19), holding the PU through another reissuing at line 20. The PU gesture enacts a stance of obviousness by presenting the relevance of the accusation/account solicitation as enduring and self-evident from the interaction thus far, notwithstanding the challenger’s attempts to address it with the notion of legality. This casts the challenger’s response as an unsuccessful defense of his position, and may also contribute to framing this as an ‘unanswerable’ question. That in this case it is the target who produces the gestured turn, while in the prior example it was the challenger, moreover illustrates that what we are dealing with here is indeed an interactional resource, as opposed to a practice that just one ‘side’ or the other makes use of in these debates.11

While our first two examples showed the ‘same’ action being redelivered in a subsequent, PU-accompanied pursuit turn, case (6) illustrates a differently designed action in the PU-accompanied turn, but an action that nonetheless is produced and understood as pursuing and insisting on a prior stance within the reality disjuncture.

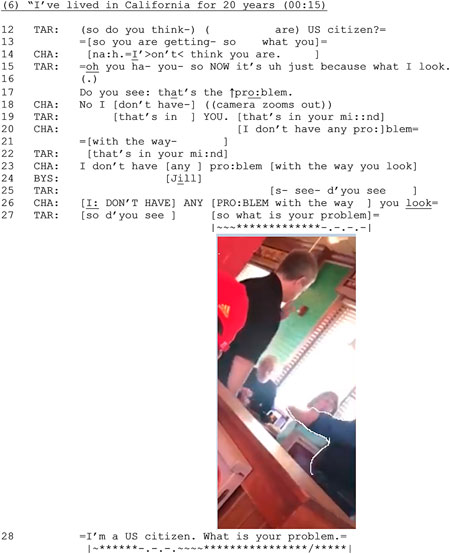

Within arguments, participants can be agentive in their deployment of resources so as to actively occasion a sequential impasse at a reality disjuncture. Reynolds (2011, 2015), for instance, describes how parties to an argument can “manufacture challenge” through the use of a “pre-challenge phase”, which serves to lay the groundwork for a subsequent challenging action. In example (6), involving a restaurant manager and a customer, we see just this sort of pre-challenge. In this case, the customer is initially upset that the manager has spoken Spanish. However, as the argument continues, the debate turns into whether the problem is the language use, the manager’s citizenship status, or the way he looks.

Line 12, though difficult for us as analysts to decipher12, is clearly heard and understood by the challenger as an inquiry into her beliefs about the target’s citizenship status, to which she responds with: “na:h. = I’>on’t < think you are.” (line 14). Upon hearing the challenger’s answer to his question, the target produces an oh-prefaced response (line 15), “oh you ha- you- so NOW it’s uh just because what I look.” Through his turn-initial oh, he “registers, or at least enacts the registration of, a change in […] state of knowledge or information” (Heritage 1998:291). Having publicly displayed this change of state, he follows up with “do you see: that’s the ↑pro:blem.” (line 17), cementing his stance that his “look(s)” (e.g., skin color) must be what the challenger actually has a problem with, rather than his having been speaking Spanish.13

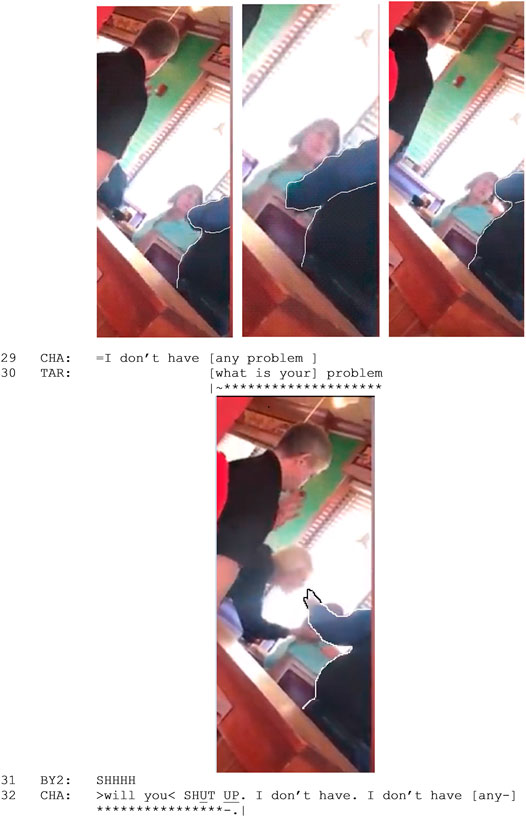

What follow are a series of attempted vehement rejections of this view of reality by the challenger (lines 18, 20–21, 23, 26, 29, 32), produced in overlap with further continuation by the target (lines 19, 22, 25, 27, 30). It is in the context of this demonstrable reality juncture, exacerbated by the evident competition in overlap (French and Local 1983; Schegloff 2000), that the target produces “so what is your problem.“, accompanied by a PU gesture (lines 27, 28 and 30).

With the PU-accompanied “so what is your problem” in line 27, the target pursues his earlier trajectory of action with regard to exposing the basis for the challenger’s claims: He proposed it must be his “looks”, and she disagreed, so then what is “the problem”? As in the prior example, “what is your problem” here seems less an account solicitation than some sort of accusation, as presumably a ‘true’ account solicitation would yield the floor for the solicited account to be provided, which the speaker demonstrably does not do here. Instead, the target takes the stance that it is obvious that the problem is something beyond his language use or citizenship status, hence the proffered explanation of his ‘look[s]’. The target’s use of the PU in his turn additionally casts the challenger’s prior rejections (lines 18, 20–21, 23, and 26) as unsuccessful in defending her point that the problem isn’t his looks.

That this multimodal turn is produced as a pursuit of the earlier accusation is further illustrated by the reinvocation of citizenship from the preparatory or pre-challenge phase—“I’m a US citizen” (line 28), produced while the target has his arms crossed on his chest, a demonstrable departure from his previous PU. This claim is latched onto a second iteration of “What is your problem” (line 28), which is again accompanied by a PU. The challenger likewise demonstrates her interpretation of these inquiries into her “problem” as pursuing the prior accusationthat her stance is based in the target’s looks, in that she continues to respond by rejecting that claim (line 29). Midway through this turn from the challenger—the now-projectable design of which exposes the persistence of the reality disjuncture—the target issues yet another “what is your problem”—again here with the PU gesture (line 30). The target’s use of the PU at line 30 reissues the stance that it is obvious that the challenger has a problem with his looks and has not admitted or successfully explained that “problem”, particularly in light of the fact that he has pursued this line of action three times, casting his challenger’s attempted oppositions as continually unsuccessful. Note that the challenger continues her orientation to the target’s move here as in pursuit of acquiescence to the “looks” accusation, in that she continues to respond with the same disconfirmation: “I don’t have any problem with the way you look” (line 36).

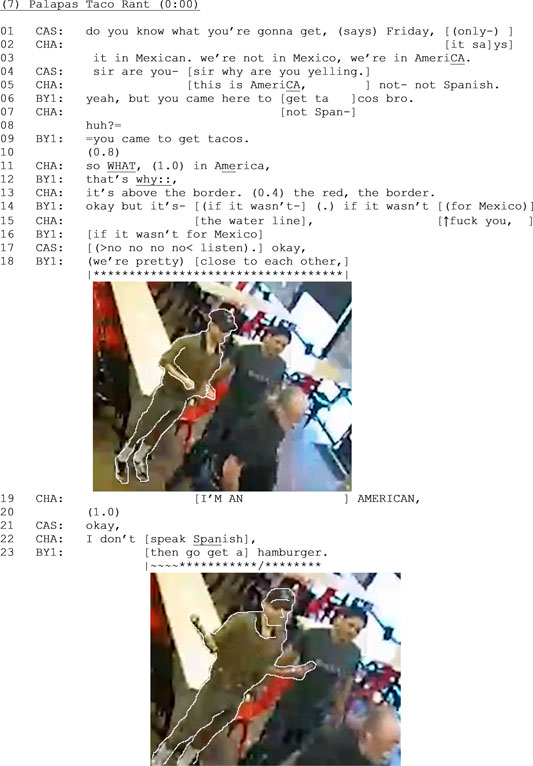

The next example (7), taken from security-camera footage, offers an additional case of this sort—that is, where two parties hold opposing viewpoints, and the PU is deployed in delivering an action that pursues a prior line of action but does so with a different action-type than was used earlier. Here, the challenger is ordering tacos at a fast-casual restaurant. The challenger is upset that the restaurant has special menu items written on a sign in Spanish and is berating the cashier for the presence of Spanish. In line 6, a bystander (another customer, standing a few feet behind the challenger, the leftmost participant in the image) inserts himself into the interaction between the challenger and the cashier with “yeah, but you came here to get tacos bro”—thereby taking the position that Spanish should not be surprising at a restaurant that specializes in tacos, a dish common to many ‘officially’ Spanish-speaking countries (lines 6 and 9). At line 11, the challenger counters with reference to the restaurant being “in America” and “above the border” (with Mexico) (line 13). The bystander acquiesces to this but immediately goes on to explain that “if it wasn’t for Mexico”—presumably headed toward some explanation of Mexico’s role in the origins of tacos; however, after three attempts produced in overlap (including with a “Fuck you” from the challenger, line 15), he abandons that piece of evidence in favor of a geographical one: “(we’re pretty) close to each other” (line 18). In partial overlap, the challenger asserts “I’m an American” (line 19) to further account for his stance within the argument. In response to this, after 1-s silence, the bystander produces “then go get a hamburger”, laminated with the PU gesture (line 23).

The bystander’s then-prefaced, PU-accompanied “then go get a hamburger” (line 23) undermines the action agenda of the challenger’s “I’m an American” (line 19), rejecting its sufficiency as an account for, or defense of, the challenger’s anti-Spanish/anti-Mexican stance. The PU turn also points back to the bystander’s initial turns, “yeah, you came here to get tacos bro.” (line 6) and “you came to get tacos.” (line 9). Although the PU turn delivers a different action (a directive) than was produced earlier in lines 6 and 9, it nonetheless pursues the same trajectory of action—namely, deploying categories related to nation-states, geography, and nationality in order to create category-bound features of food and language use, and casting it as obvious and now sequentially self-evident that Spanish would be used at a restaurant serving tacos. The participants had reached an impasse in which their perspectives were demonstrably not aligning—one offering accounts in the form of food origins and geographical proximity, the other accounting in terms of borderlines and culminating with an assertion about personal identity. It is in the environment of this demonstrated stalemate and hitch in progressivity (note the 1-s pause in line 20) that the bystander elects to pursue his earlier established stance through this directive action, accompanied now by the PU gesture. The gesture is held as the directive to go get a hamburger is repeated in line 25, followed up by an additional directive to “go get a hot dog”, also produced twice (lines 25, 27); hamburgers and hot dogs are thus categorized as canonical American foods, and thus what are ‘logically appropriate’ for the challenger in light of his counterclaim—yet another dimension of the ‘obviousness’ of bystander’s action. This multimodal pursuit in line 25 thereby frames the challenger’s “I’m an American” (line 19) defense as unsuccessful in defending his stance against the use of Spanish in the restaurant.

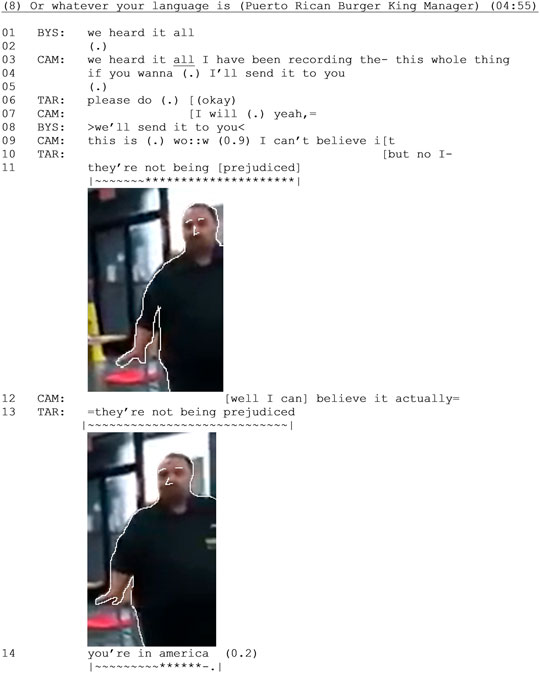

Consider one final example in (8). This case comes from the aftermath of a challenger-target confrontation, wherein a restaurant patron targets the manager of a fast-food restaurant. The patron/challenger tells the manager/target that if he wants to speak Spanish, he should go back to Mexico, to which the manager/target responds that he is not even Mexican. After the challenger leaves the restaurant, a pair of bystanders—other patrons in the restaurant, labeled ‘BYS(tander)’ and ‘CAM(era person)’ in the transcript below—tell the target that they witnessed the whole encounter and caught it on video (lines 1–4). The bystanders and the target then align and affiliate with each other for several turns expressing their collective outrage at how the challenger behaved, culminating in the exchange of email addresses so that the bystanders can send the target a copy of the video (line 20-onward).

During the earlier exchange with the challenger, the target’s identity as not Mexican was explicitly topicalized in response to directives from the challenger, namely that he “go back to Mexico”, to his “Mexican country”—e.g., “guess what ma’am (.) I’m not Mexican” (data not shown). In addition, during the argument, on no less than ten distinct occasions did the target overtly categorize what the challenger was doing as “prejudiced” (data not shown). In the aftermath of the confrontation, when the target is talking with the bystanders, he asserts “but no I- they’re not prejudiced” (line 11), repeated in line 13, “they’re not being prejudiced” (note the distinct palm-down gesture present through these turns). Given the earlier context, which the bystanders have already claimed to have witnessed in its entirety, this assertion is plainly offered sarcastically, and as preliminary to subsequent rebuttal. In support of this sarcastic stance that the challenger was “not” being prejudiced, the target then launches into an episode of direct reported speech (Holt 1996), quoting from the exchange he just had with the challenger: “You’re in America. (0.2) Go back to Mexico.” (lines 14–15). This reported directive to go back to Mexico re-creates a particular moment in which a reality disjuncture was demonstrable in the interaction. Importantly, this reality disjuncture is relevant not only in the context of the reported speech event, where the challenger was inappositely insisting on the target’s Mexicanness in spite of his claims to the contrary, but also in the present context of speaking with the bystanders, for whom the target’s non-Mexicanness is likewise sequentially established and salient. In response to this reported directive, the target produces the PU gesture by itself, without any verbal accompaniment, which he holds through the bystanders’ subsequent laughter and through his next turn (lines 15–17).

As the target quotes the challenger in lines 14–15 (“You’re in America/Go back to Mexico”), he holds a pointing gesture, deictically embodying you’re. When the target exposes the faulty logic of this directive, he switches from the point to the PU, displaying an embodied contrast that is produced as responsive to the reality disjuncture exposed by the directive “Go back to Mexico,” because a man not of Mexican origin cannot/would not go “back” to Mexico. The PU gesture’s indexation of obviousness here works to expose the logical nonsensicality of the challenger’s proposition given what is accountably known from the sequential progression of the interaction. Use of the PU gesture in combination with silence in response to this reported-speech directive delegitimizes the challenger’s earlier directive, and simultaneously pursues the target’s earlier sarcastic assessment that the challenger was “not being prejudiced” (lines 11/13) by offering reported-speech evidence of his stance (see Clift 2006). This enactment is received with affiliative laughter from both of the bystanders, who thereby show themselves to share the target’s stance as to the obviousness of challenger’s conduct as being prejudiced. This case likewise demonstrates that the PU gesture can be produced, understood, and responded to appropriately by itself—i.e., without being laminated onto any particular accompanying verbal utterance.

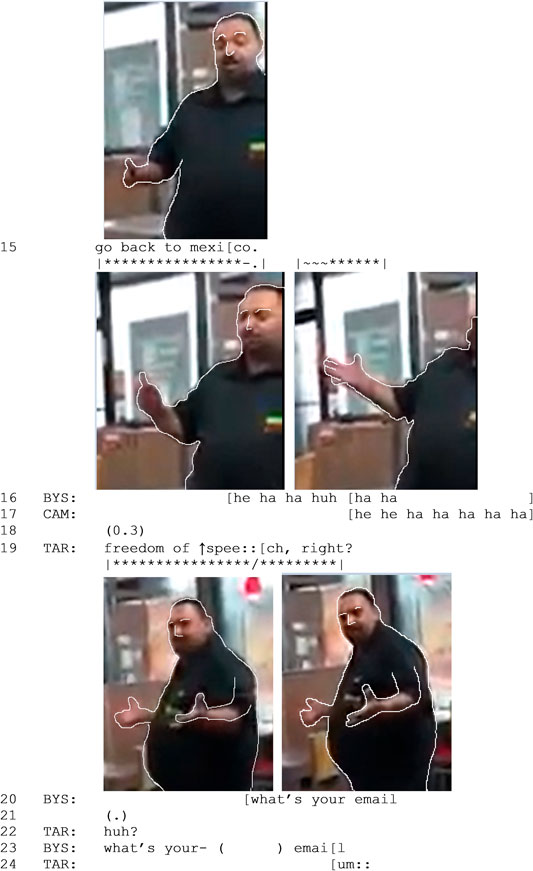

The target holds the PU gesture through the laughter and into his subsequent turn—“Freedom of speech” (line 19)—during which the gesture is lowered slightly. He appends “right” and strikes the gesture before lowering his arms, with releasing the gesture appearing to mark the participants’ arrival at a publicly demonstrated shared understanding (Sikveland and Ogden 2012)—that the target plainly cannot “go back” to Mexico, as he is not from there, and that the United States operates under a policy of “freedom of speech” that by definition does not mandate the use of any particular language in public spaces. This reference to “freedom of speech” seems to also work as a figure of speech (Drew and Holt 1998) in that it provides for a transition to the bystander asking for the manager’s email to send him the video.

In this section, we have illustrated the use of the PU gesture in a particular sequential and action context—namely to pursue a line of action that the speaker themselves already committed to previously, despite having arrived at a demonstrable ‘reality disjuncture’ with their recipient. Using a PU gesture in pursuing a line of action committed to earlier indexes a stance of obviousness, which in context works to frame the interlocutor’s prior conduct as having been an attempt at undermining the gesturer’s line of action, but an attempt that has failed. As might be expected, such moments—and, accordingly, the use of the PU gesture—are recurrent in the expressly argumentative data that we examined here.

Discussion

On ‘Obviousness’ as a Participants’ Category

In light of this analysis of the PU gesture, we can now ask how this embodied resource fits in with other interactional resources that have been claimed to index ‘obviousness’. In addition to the encoding of obviousness through lexical marking (e.g., adverbs like obviously, response types like of course; Stivers 2011), particles are one element of verbal grammar that appear to be routinely used cross-linguistically to encode stances of obviousness.

Consider, first, the case of turn-initial oh in English. When used as a preface, speakers mobilize the particle’s change-of-state semantics in order to convey an epistemic stance toward the action being committed (Heritage 1984b, 1998, 2002). This epistemic stance can in context be one of ‘obviousness’, grounded in the prior talk of the interactants. “Oh-prefaced responses are common,” Heritage (1998) writes, “in environments where questions address matters on which the respondent has already conveyed relevant information either explicitly or by presupposition”—that is, in sequential environments “where the information is (or should be) ‘already known’ to the questioner” (297).14

For a case of a particle that “can appear anywhere in the clause” (Valijärvi and Kahn 2017:234), consider gal in North Sámi, a Uralic language spoken in the northern regions of Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Valijärvi and Kahn write that this “independent particle” can be used for “confirming or reinforcing the truth or obviousness of a statement” (234). The authors unfortunately do not provide a sequentially contextualized example, only the isolated utterance “Mun in gal háliit dope fitnat.“, which they translate as “I really don’t want to go there” (235). Note that North Sámi also has an enclitic particle –han, which, when attached to the first constituent in the clause, similarly “indicates that the information to which it refers is or should be obvious or known to the interlocutor” (232).

As we consider such cross-linguistic observations from typologically distinct languages, it becomes evident that indexing ‘obviousness’ constitutes a participants’ concern and a participants’ project, but one that is undoubtedly multidimensional in nature. Indeed, the action environments in which oh indexes obviousness are plainly distinct from the PU environments we’ve explored in this paper. However, in both cases, what we see are participants grounding their claims of obviousness in what should (from their perspective) accountably be known at that moment in the interaction.

For an even closer parallel between the particular sort of ‘obviousness’ indexed by the PU gesture and the work of particles, consider the Mandarin modal particle me /mə/15 As Chappell (1991) illustrates, in utterance-final position, me functions:

1) to remind the listener that the entire proposition is obvious or self-evident from the preceding discussion or from their shared cultural knowledge

2) to express disagreement, possibly combined with indignation or impatience at the hearer’s opposite point of view (16).

With regard to interaction, Chappell writes that the particle “conveys that since the situation is clear and obvious, no further discussion need be entered into” (17), thereby taking the stance that “there’s nothing more to say about it” (24). The near-exact parallel with Kendon (2004) wording to describe the PU gesture—as marking the proposition as obvious or redundant, about which “nothing further can be said” (265)—is striking.

Equally striking is the parallel between the PU examples reviewed in this paper, and the following anecdote about me from Chao’s (1968) grammar of Mandarin:

“Because this me involves a dogmatic and superior attitude on the part of the speaker, I have often found it difficult, on my field trips for dialect survey, to elicit the dialectal equivalents of this particle from the informants, who often felt diffident about assuming a dogmatic tone. I would take a pencil and say to the informant (in as near his dialect as I knew how) ‘This is a pen.’ ‘No, this is a pencil.‘, he would say. ‘No, it isn’t’. ‘Yes, it is.’ And after a few times, if he got in the right mood, he would say, impatiently.

Shì de me, zhè shì qiānbǐ me!

be DE ME this be pencil ME.

‘Yes it is, it is a pencil.’

But if the informant was a student who mistakenly thought that I had come out to teach him the standard National Language, instead of trying to learn from him, then it was often impossible to elicit the impatient, dogmatic mood of the particle me (Chao 1968:801, fn. 73; cited in Chappell 1991:23)”.

Note in particular the back-and-forth “a few times” of “Yes, it is”—“No, it isn’t”, which is precisely the ‘impasse’ or ‘reality disjuncture’ sort of sequential context in which we find the PU gesture in our data. Moreover, what the me speaker does with his me-marked turn in Chao’s example is reassert an action that he himself had already expressed earlier, but now taking the stance that proposition should at this point be obvious in light of the sequential progression of the talk. Just like use of the PU gesture in our corpus, then, by using the me particle to index the obviousness of the reasserted proposition, the speaker orients to the existence of ongoing discord between the interactants, while simultaneously highlighting the persistence of his own stance in the face of the recipient’s attempts to counter it.

In the case of Mandarin me, then, grammar is being brought to bear to encode a particular stance of obviousness in sequential and action environments that appear to be (to borrow a phrase from Levinson) so “very similar, in some cases eerily similar” (Levinson 2006:46) to our cases of the PU gesture that the a priori exclusion of the body from our conceptualization of grammar becomes difficult to substantiate.

Our aim in considering verbal grammatical resources in this way should not be interpreted as an attempt to prioritize the verbal channel over the gestural. Rather, our objective here is to draw concerted attention to just how similar the PU gesture in our data seems to be to other resources examined in the literature in terms of their positioning and functions: If these other (verbal) resources so unambiguously constitute part of our conceptualization of grammar—and of the grammatical encoding of epistemicity, specifically—then on what grounds can the PU gesture be discounted? It is difficult for us to see the logic in an theory of grammar that posits turn-final me in Mandarin as part of grammar, used to take a particular epistemic stance in interaction, while at the same time rejecting the PU gesture’s inclusion in a similar category. That one is accomplished verbally and the other is accomplished gesturally does not, in our view, constitute adequate grounds for the categorization of one as ‘grammar’ and the other not. We likewise cannot see the logic in attempting to understand humans’ orientations to epistemicity solely through verbal resources, without recognizing the empirical reality—evident in the data we have considered here—that the body too is brought to bear on the encoding of epistemic stances. Such a division would reflect an analyst’s conceptualization of grammar, verbally biased, as opposed to an understanding of grammar that is informed by and prioritizes the participants’ perspectives, which they make visible to each other and to us, in and through their conduct—corporeal conduct included. As Du Bois (1985) writes, “grammars code best what speakers do most” (363), and as we have seen in the data reviewed here, as well as in the prior literature we’ve discussed, coding something like ‘obviousness’ seems to be something the “speakers”—or, rather, participants—routinely find themselves in need of encoding as they interact with one another. In this way, we support Keevallik (2018) call for a reconceptualization of the notion of ‘grammar’ to one that is “capable of incorporating aspects of participants’ bodily behavior” (1), as the entire body is brought to bear in the service of producing and understanding action in sequences of interaction.

On Particles and Gestures in Grammar

Thinking in a more holistic way about grammar opens up a range of avenues for future research, as it allows us to situate our inquiries within the fuller array of resources that participants bring to bear to make sense with one another on a moment-by-moment basis in face-to-face interaction.

In the prior section, we focused on similarities between the PU gesture and different verbal particles, all of which were argued to index epistemic stances of ‘obviousness’. A further similarity between the PU gesture and many of these particles appears to be what might be conceived of as their ‘optional’ or ‘marked’ status. As Heritage (1998) writes, in the case of oh-prefacing, the use of this particle “is an optional marking of response—not a required, or still less, ‘routinized’ feature of response. Further, as an optional practice, it is used to achieve specific, marked effects” (329, fn. 11; see also Heritage 1997 for an analysis of the lack of an oh). Similarly, as Chao (1968) recounted in his footnote, no matter the sequential progression of the talk—in the terms used in this study, no matter how persistent the reality disjuncture—“it was often impossible to elicit the impatient, dogmatic mood of the particle me” from certain speakers (Chao 1968:801, fn. 73). The same is true of the PU gesture, in that it is not a routinized feature of all pursuit actions, for example. Rather, it is deployed with specific marked effect in certain sequences, to index a particular epistemic stance that the proposition should be obvious to the recipient.

Our reason for highlighting the ‘optionality’ of indexing this particular epistemic stance—i.e., of obviousness—is that it is distinct from the morphosyntactic marking of, for example, the origin of some piece of knowledge as directly witnessed vs hearsay vs assumed, etc., which many languages mark obligatorily. What we see in common when considering the PU gesture alongside the ‘optional’ verbal particles reviewed here, then, is a realm of grammar that is “altogether more discretionary” (Raymond et al., 2021) on the part of the participants—where interactants can be seen and heard to be making grammatical choices in response to and in accordance with the contingencies of moment-by-moment interaction, and the stances they elect (but are not required) to take as they collaboratively produce and interpret action (see Ochs et al., 1996; Ford and Fox 2015; Thompson et al., 2015; Clift 2016; Couper-Kuhlen and Selting 2018).

A further parallel between the PU gesture and at least some of the verbal particles that index obviousness is their ability to be laminated onto a range of different morphosyntactic constructions and action types. The same can be seen in our examples, in that we find the PU gesture accompanying declarative assertions (extract 8, line 19), interrogatives (extract 5, line 19; extract 6, lines 27 and 30), imperatives (extract 7, line 23; extract 4, line 8), and even without any verbal syntax at all (extract 8, line 15). Moreover, the gesture can be produced smoothly, notwithstanding hitches and reformulations of the particular verbal grammatical design of the turn (extract 4, line 8). The PU gesture thus shares a family resemblance with the particles reviewed here in the relative flexibility with which these resources can be laminated onto different verbal designs, as deemed relevant by the speaker. That particles and gestures—both with their particular affordance of a certain ‘independence’ vis-à-vis other elements of verbal grammar—appear to be the grammatical resources that social interactants bring to bear in adopting this particular epistemic stance, grants us insight into ‘obviousness’ as a participants’ grammatical category. It may be precisely because interactants find themselves in need of indexing the obviousness of a wide range of actions—not only those formulated with a very particular verbal morphosyntactic configuration—that particles and gestures are useful grammatical resources with which to encode such an epistemic stance.

Nevertheless, apart from these similarities, there are of course differences that merit further exploration. Due to its embodied nature, the PU offers particular affordances: For example, it can be produced simultaneously with verbal discourse, and it can be held for the duration of a turn or across multiple turns (Clift 2020). Ford et al. (2012) argue that these affordances make embodied movements particularly useful for displaying stance, especially when we compare them to verbal particles, as the ability to hold gesture throughout turns is a powerful property that distinguishes them from traditionally sequentially-bounded vocal resources of grammar.

It is also important to remember that the English-speaking participants in our dataset do have other verbal resource for indexing obviousness in addition to the PU gesture. So while, as we have argued, in these cases participants can be seen to be leveraging prior talk and conduct as the basis for indexing obviousness, there are evidently—for the participants—different ‘sorts’ of obviousness that are differently marked, whether by verbal or gestural resources. More systematic attention to the differences in the particulars of these stances of ‘obviousness’, across languages, will continue to expand our understanding of epistemicity as a participants’ category of grammar.

Conclusion

In this paper, we began by asking how participants locally construct their actions so as to be understood as belonging to, and thereby simultaneously constructing, an ongoing argument. As highlighted in the excerpts analyzed here, in argumentative contexts, participants often reach a point of impasse, where both sides maintain opposing stances, and neither gives way to their opponent. We have shown that at these reality disjunctures, participants can employ the PU gesture to not only pursue a previously established position, but also take an epistemic stance to index the obviousness of that position in the face of attempted counteractions by the recipient.

We then linked the positioning and function of the PU gesture to features of verbal grammar in different languages, allowing us to highlight similarities in resources produced via the verbal and gestural channels of grammar. On the basis of this discussion, we argued that an a priori separation of the body from our conceptualization of grammar—in this case, the grammar of epistemicity—is tantamount to disattending to the details of participants’ conduct in interaction, which thereby does a disservice to the study of grammar in action.

As we have illustrated in this analysis, the PU gesture we focused on is found with and in response to a variety of syntactic and grammatical structures, and moreover can also appear on its own, with no verbal utterance at all. This empirical observation challenges the assumption that a focus on grammar-in-interaction should begin with, or otherwise be examined in relation to, ‘standard’ verbal-only grammatical categories (e.g., imperative, declarative). Had we begun with a particular verbal grammatical form, for instance, we would have missed the opportunity to consider an embodied practice that can be laminated onto a range of different verbal grammatical turn designs, which indeed appears to be one of its primary affordances. By taking the embodied practice as the common unit of grammatical analysis, and investigating where, specifically, these gestures are produced in interaction, we were able to expand our understanding of epistemicity in grammar by unpacking ‘obviousness’ as a participant’s category, thereby exploring the intersection between grammar and the body in a novel way.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

Open-access to this article is provided by a grant from the University of Colorado Boulder (to Raymond).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandy Thompson and Zygmunt Frajzyngier for sharing their cross-linguistic and typological expertise with us, which is especially reflected in the Discussion section presented here. Any remaining errors are, of course, our own.

Footnotes

1We borrow the terms “challenger” and “target” from Reynolds (2015:303). These are used to label participants in the overall activity, rather than on a local/turn-by-turn basis (i.e., a challenger of a previous turn). See “Data” section below.

2As a case-in-point, it is conceivable that these gestures also include specific facial details, although the videos are not always high-enough quality to conduct such an analysis. Instead, we focus on what is clearly captured and demonstrable—i.e., the palms and arms.

3For more discussion on the use of third-party video, see Jones and Raymond (2012).

4The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has reported that national-origin discrimination complaints have increased 76% since 2005. Cases and complaints based on language use are categorized as national-origin discrimination. See also Fermoso (2018), who reports specifically on cases of anti-Spanish-speaking discrimination.

5Most relevant are the following symbols, all from Kendon (2004), with the number of symbols corresponding to the length of the gesture, in conjunction with any spoken discourse:| to indicate the beginning and end of the gesture ∼ ∼ ∼ to show the preparation phase * * * to show the stroke of the recognizable gesture/to show a re-doing of a stroke -.-.- to show recovery and return of hand placement.

6Because the videos often pan quickly between multiple people, both hands of the focus participant are not always perfectly visible. Nevertheless, when both hands and arms are in view, they follow the same format of the PU gesture in the focal turns.

7Note that the corpus referred to here is, as stated in the prior section, ever-increasing in terms of the number of videos it houses. The numbers reported here are thus included primarily to give a sense of relative, as opposed to absolute, frequencies.

8See Park (2010) for an analysis of the use of anyway at impasses.

9Beaupoil-Hordel and Debras (2017) similarly found that palm-ups in shrugging gestures can also index obviousness, specifically at the conclusion of an activity where there is nothing more to do (see also Jehoul, Brône & Feyaerts 2017).

10Note also the transformation of “police” (line 2) to “cops” (line 8) (on which, see Jefferson 1974:184).

11See also case (7) in which the gesture is produced by a bystander.

12The difficulty in hearing this turn is caused by the various bystander/audience reactions (e.g., “Wow”) that are still wrapping up at its onset (data not shown).

13We acknowledge that at this moment, the target is challenging the original challenger’s problem. Nevertheless, we have kept participant ID labelling consistent across the entire interaction. See footnote 1.

14For a parallel analysis of prefatory particles and obviousness in French (e.g., ah oui), see Persson (2020).

15The vowel here is an unstressed atonal schwa, which, following Chappell (1991), we are representing in the context of this particle as ‘me’.

References

Abner, N., Cooperrider, K., and Goldin-Meadow, S. (2015). Gesture for Linguists: A Handy Primer. Lang. Linguistics Compass. 9 (11), 437–451. doi:10.1111/lnc3.12168

Alim, H. S. (2016). “Introducing Raciolinguistics,” in Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race. Editors H. S. Alim, J. Rickford, and A. Ball (New York: Oxford University Press), 1–30. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190625696.003.0001

Anderson, B. R. O. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Andrén, M. (2017). “Children's Expressive Handling of Objects in a Shared World,” in Intercorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction. Editors C. Meyer, J. Streeck, and J. Jordan (Oxford University Press), 1, 105–142. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190210465.003.0005

Antaki, C. (1994). Explaining and Arguing: The Social Organization of Accounts. London: Sage Publications. Available at: http://archive.org/details/explainingarguin0000anta.

Baugh, J. (2016). “Linguistic Profiling and Discrimination,” in The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society. Editors O. García, N. Flores, and M. Spotti (Oxford). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190212896.013.13

Beaupoil-Hourdel, P., and Debras, C. (2017). Developing Communicative Postures. Lia. 8 (1), 89–116. doi:10.1075/lia.8.1.05bea

Boggs, S. T. (1978). The Development of Verbal Disputing in Part-Hawaiian Children. Lang. Soc. 7 (3), 325–344. doi:10.1017/S0047404500005753

Bolden, G. B., and Robinson, J. D. (2011). Soliciting Accounts With Why-Interrogatives in Conversation. J. Commun. 61, 94–119. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01528.x

Chappell, H. (1991). “Strategies for the Assertion of Obviousness and Disagreement in Mandarin: A Semantic Study of the Modal Particle Me,” in Santa Barbara Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 3: Asian Discourse and Grammar. Editors P. M. Clancy, and S A. Thompson (Santa Barbara: University of California), 9–32. doi:10.1080/07268609108599451

Chu, M., Meyer, A., Foulkes, L., and Kita, S. (2014). Individual Differences in Frequency and Saliency of Speech-Accompanying Gestures: The Role of Cognitive Abilities and Empathy. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143 (2), 694–709. doi:10.1037/a0033861

Clayman, S. E., and Heritage, J. (2002). The News Interview: Journalists and Public Figures on the Air. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clift, R. (2006). Indexing Stance: Reported Speech as an Interactional Evidential. J. Sociolinguistics 10 (5), 569–595. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2006.00296.x

Clift, R. (2020). Stability and Visibility in Embodiment: The ʻPalm up' in Interaction. J. Pragmatics 169, 190–205. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.005

Clift, R., and Raymond, C. W. (2018). Actions in Practice: On Details in Collections. Discourse Stud. 20 (1), 90–119. doi:10.1177/1461445617734344

Clift, R. (2020). Stability and Visibility in Embodiment: The 'Palm up' in Interaction. J. Pragmatics. 169, 190–205. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.005

Cooperrider, K., Abner, N., and Goldin-Meadow, S. (2018). The Palm-Up Puzzle: Meanings and Origins of a Widespread Form in Gesture and Sign. Front. Commun. 3, 23. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2018.00023

Corsaro, W. A., and Maynard, D. W. (1996). “Format Tying in Discussion and Argumentation Among Italian and American Children,” in Social Interaction, Social Context, and Language: Essays in Honor of Susan Ervin-Tripp. Editors D. I. Slobin, J. Gerhardt, A. Kyratzis, and E. Guo (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 157–174.

Couper-Kuhlen, E., and Selting, M. (2018). Interactional Linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Couper-Kuhlen, E., and Thompson, S. A. (Frth). “Action Ascription in Everyday Advice-Giving Sequences,” in Action Ascription: Interaction in Context. Editors A. Depperman, and M. Haugh (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Drew, P., and Holt, E. (1998). Figures of speech: Idiomatic expressions and the management of topic transition in conversation. Lang. Soc. 27 (4), 495–522.

Du Bois, J. W. (1985). “Competing Motivations,” in Iconicity in Syntax. Editor J. Haiman (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 343–365. doi:10.1075/tsl.6.17dub

Du Bois, J. W., and Kärkkäinen, E. (2012). Taking a Stance on Emotion: Affect, Sequence, and Intersubjectivity in Dialogic Interaction. Text & Talk. 32 (4), 433–451. doi:10.1515/text-2012-0021

Du Bois, J. W. (2007). “The Stance Triangle,” in Stancetaking in Discourse: Subjectivity, Evaluation, Interaction. Editor R. Englebretson (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 139–182. doi:10.1075/pbns.164.07du

Enfield, N. (2009). The Anatomy of Meaning: Speech, Gesture, and Composite Utterances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fermoso, J. (2018). “Why Speaking Spanish Is Becoming Dangerous in America.” the Guardian. Available at: www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/may/22/speaking-spanish-dangerous-america-aaron-schlossberg-ice.

Floyd, S. (2016). Modally Hybrid Grammar?: Celestial Pointing for Time-Of-Day Reference in Nheengatú. Language 92 (1), 31–64. doi:10.1353/lan.2016.0013

Ford, C. E., and Fox, B. A. (2015). “Ephemeral Grammar: At the Far End of Emergence,” in Studies in Language and Social Interaction. Editors A. Deppermann, and S. Günthner (John Benjamins Publishing Company), 27, 95–120. doi:10.1075/slsi.27.03for

Ford, C. E., Thompson, S. A., and Drake, V. (2012). Bodily-Visual Practices and Turn Continuation. Discourse Process. 49 (3–4), 192–212. doi:10.1080/0163853X.2012.654761

Fox, B. A., and Heinemann, T. (2015). The Alignment of Manual and Verbal Displays in Requests for the Repair of an Object. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 48 (3), 342–362. doi:10.1080/08351813.2015.1058608

French, P., and Local, J. (1983). Turn-Competitive Incomings. J. Pragmatics 7, 17–38. doi:10.1016/0378-2166(83)90147-9

García, O. (2014). U.S. Spanish and Education. Rev. Res. Education 38 (1), 58–80. doi:10.3102/0091732X13506542

Goodwin, M. H. (1982). Processes of Dispute Management Among Urban Black Children. Am. Ethnol. 9 (1), 76–96. doi:10.1525/ae.1982.9.1.02a00050

Goodwin, M. H. (1990). He-Said-she-Said: Talk as Social Organization Among Black Children. Indiana University Press.

Goodwin, M. H. (1998). “Games of Stance: Conflict and Footing in Hopscotch,” in Kids’ Talk: Strategic Language Use in Later Childhood. Editors S. M. Hoyle, and C. T. Adger (Oxford University Press), 23–46.

Goodwin, C. (2003). “Pointing as Situated Practice,” in Pointing: Where Language, Culture and Cognition Meet. Editor K. Sotaro (Bloomington, IN: Lawrence Erlbaum), 217–241. doi:10.4324/9781410607744-13

Goodwin, C. (2006). Retrospective and Prospective Orientation in the Construction of Argumentative Moves. Text Talk - Interdiscip. J. Lang. Discourse Commun. Stud. 26 (4–5), 443–461. doi:10.1515/TEXT.2006.018

Goodwin, M. H., Goodwin, C., and Yaeger-Dror, M. (2002). Multi-Modality in Girls’ Game Disputes. J. Pragmatics 34 (10–11), 1621–1649. doi:10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00078-4

Harness Goodwin, M. (2002). Building Power Asymmetries in Girls' Interaction. Discourse Soc. 13 (6), 715–730. doi:10.1177/0957926502013006752

Enfield, N. (2009). The Anatomy of Meaning: Speech, Gesture, and Composite Utterances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hepburn, A., and Bolden, G. B. (2017). Transcribing for Social Research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781473920460

Heritage, J. (1984a). “A Change-Of-State Token and Aspects of its Sequential Placement,” in Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Editors J. Atkinson, and J. Heritage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Heritage, J. (1997). “Conversation Analysis and Institutional Talk: Analyzing Data” in Qualitative Research: Theory, Method, and Practice. Editor D. Silverman (London: Sage), 161–182.

Heritage, J. (1998). Oh-prefaced Responses to Inquiry. Lang. Soc. 27 (3), 291–334. doi:10.1017/s0047404500019990

Heritage, J. (2002). “Oh-Prefaced Responses to Assessments: A Method of Modifying Agreement/disagreement,” in The Language of Turn and Sequence. Editors C.E. Ford, B.A. Fox, and S.A. Thompson (Oxford University Press), 196–224.

Heritage, J. (2013). “Epistemics in Conversation,” in The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Editors J. Sidnell, and T. Stivers (Wiley-Blackwell), 370–394.

Holt, E. (1996). Reporting on Talk: The Use of Direct Reported Speech in Conversation. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction. 29 (3), 219–245. doi:10.1207/s15327973rlsi2903_2

Jefferson, G. (1974). Error Correction as an Interactional Resource. Lang. Soc. 3 (2), 181–199. doi:10.1017/s0047404500004334

Jefferson, G. (2004). “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction,” in Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation. Editor G.H. Lerner (Philadelphia: John Benjamins), 13–31. doi:10.1075/pbns.125.02jef

Jehoul, A., Brône, G., and Feyaerts, K. (2017). The Shrug as Marker of Obviousness. Linguistics Vanguard. 3 (s1). doi:10.1515/lingvan-2016-0082

Jones, N., and Raymond, G. (2012). “The Camera Rolls”. ANNALS Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 642 (1), 109–123. doi:10.1177/0002716212438205

Keevallik, L. (2020). “Chapter 6. Linguistic Structures Emerging in the Synchronization of a Pilates Class,” in Mobilizing Others: Grammar and Lexis within Larger Activities. Editors C. Taleghani-Nikazm, E. Betz, and P. Golato (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 147–173. doi:10.1075/slsi.33.06kee

Keevallik, L. (2018). What Does Embodied Interaction Tell Us about Grammar? Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 51 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413887

Lempert, M., and Silverstein, M. (2012). Creatures of Politics: Media, Message, and the American Presidency. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucb/detail.action?docID=995566.

Levinson, S. C. (2006). “On the Human "Interactional Engine,” in Roots of Human Sociality: Cognition, Culture, and Interaction. Editors N.J. Enfield, and S. C. Levinson (London: Berg), 39–69.

Li, X. (2019). “Multimodal Turn Construction in Mandarin Conversation - Verbal, Vocal, and Visual Practices in the Construction of Sytactically Incomplete Turns,” in Multimodality in Chinese Interaction. Editors X. Li, and T. Ono (Berlin: De Gruyter), 181–212. doi:10.1515/9783110462395-008

Lippi-Green, R. (2012). English with an Accent: Language, Ideology and Discrimination in the United States. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Maynard, D. W. (1985). How Children Start Arguments. Lang. Soc. 14 (1), 1–29. doi:10.1017/s0047404500010915

Maynard, D. W. (1988). Language, Interaction, and Social Problems. Soc. Probl. 35 (4), 311–334. doi:10.1525/sp.1988.35.4.03a00020

McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal about Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mondada, L. (2014). The Local Constitution of Multimodal Resources for Social Interaction. J. Pragmatics 65, 137–156. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004

Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of Multimodality: Language and the Body in Social Interaction. J. Sociolinguistics 20 (3), 336–366. doi:10.1111/josl.1_12177

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 51 (1), 85–106. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Müller, Cornelia. (2004). “The Palm-Up-Open-Hand. A Case of a Gesture Family?,” in The Semantics and Pragmatics of Everyday Gestures. Editors (Berlin: Weidler), 233–256.

Müller, C. (2004). The Palm-Up-Open-Hand. A case of a gesture family? In The semantics and pragmatics of everyday gestures (pp.233–256). Cornelia Müller, Roland Posner (Eds.). Berlin: Weidler.

Ochs, E., Schegloff, E. A., and Thompson, S. A. (1996). Introduction. In Interaction and Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Park, I. (2010). Marking an Impasse: The Use of Anyway as a Sequence-Closing Device. J. Pragmatics 42, 3283–3299. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.06.002

Paul, Drew., and Holt, Elizabeth. (1998). Figures of Speech: Idiomatic Expressions and the Management of Topic Transition in Conversation. Lang. Soc. 27 (4), 495–522.

Pekarek Doehler, S. (2019). At the Interface of Grammar and the Body: Chais Pas (“dunno”) as a Resource for Dealing With Lack of Recipient Response. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 52 (4), 365–387. doi:10.1080/08351813.2019.1657276

Persson, R. (2020). Taking Issue With a Question While Answering it: Prefatory Particles and Multiple Sayings of Polar Response Tokens in French. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 53 (3), 380–403. doi:10.1080/08351813.2020.1786977

Pollner, M. (1975). 'The Very Coinage of Your Brain': The Anatomy of Reality Disjunctures. Philos. Soc. Sci. 5 (3), 411–430. doi:10.1177/004839317500500304

Pollner, M. (1987). Mundane Reason: Reality in Everyday and Sociological Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Raymond, C. W., Albert, S., Grothues, N., Henry, J., Marrese, O., Pielke, M., et al. (in prep). The Corpus of Language Discrimination Interaction (CLDI). Manuscript. Boulder: University of Colorado.

Raymond, C. W., Clift, R., and Heritage, J. (2021). Reference Without Anaphora: On Agency Through Grammar. Linguistics: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Language Sciences. doi:10.1515/ling-2021-0058

Raymond, C. W., Robinson, J., Fox, B. A., Thompson, S. A., and Montiegel, K. (2021b). Modulating Action Through Minimization: Syntax in the Service of Offering and Requesting. Lang. Soc. 1, 53–91. doi:10.1017/s004740452000069x

Reynolds, E. (2011). Enticing a Challengeable in Arguments: Sequence, Epistemics and Preference Organisation. Pragmatics 21, 411. doi:10.1075/prag.21.3.06rey

Reynolds, E. (2015). How Participants in Arguments Challenge the Normative Position of an Opponent. Discourse Stud. 17, 303. doi:10.1177/1461445615571198

Rosa, J. (2019). “Looking like a Language, Sounding like a Race: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Learning of Latinidad,” in Looking like a Language, Sounding like a Race (Oxford University Press).

Rosa, J., and Flores, N. (2017). Unsettling Race and Language: Toward a Raciolinguistic Perspective. Lang. Soc. 46 (5), 621–647. doi:10.1017/S0047404517000562

Sacks, H. (1986). Some Considerations of a Story Told in Ordinary Conversations. Poetics 15 (1–2), 127–138. doi:10.1016/0304-422x(86)90036-7

Santa Ana, O. (2002). Brown Tide Rising: Metaphors of Latinos in Contemporary American Public Discourse. Austin, TX, University of Texas Press. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucb/detail.action?docID=3443287.

Schegloff, E. A. (1996). “Turn Organization: One Intersection of Grammar and Interaction,” in Interaction and Grammar. Editors E. Ochs, E. A. Schegloff, and S. Thompson (Cambridge University Press), 52–133. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511620874.002

Schegloff, E. A. (1997). Practices and Actions: Boundary Cases of Other‐Initiated Repair. Discourse Process. 23 (3), 499–545. doi:10.1080/01638539709545001

Schegloff, E. A. (2000). Overlapping Talk and the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation. Lang. Soc. 29 (1), 1–63. doi:10.1017/s0047404500001019

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis, 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shaw, E. (2013). Gesture in Multiparty Interaction: A Study of Embodied Discourse in Spoken English and American Sign Language. Unpublished thesis manuscript. Washington DC: Georgetown University.

Sikveland, R. O., and Ogden, R. (2012). Holding Gestures Across Turns. Gest. 12 (2), 166–199. doi:10.1075/gest.12.2.03sik

Silverstein, M. (2015). How Language Communities Intersect: Is “Superdiversity” an Incremental or Transformative Condition? Lang. Commun. 44, 7–18. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2014.10.015

Silverstein, M. (2018). “Monoglot “Standard” in America: Standardization and Metaphors of Linguistic Hegemony,” in The Matrix of Language. Editors D. Brenneis, and R. K. S. Macaulay. 1st ed (Routledge), 284–306. doi:10.4324/9780429496288-18

Stivers, T. (2011). Morality and question design: 'of course' as contesting a presupposition of askability, In The Morality of Knowledge in Conversation (Tanya Stivers, Lorenza Mondada, Jakob Steensig, eds.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 82–106.

Streeck, J. (2017). Self-making Man: A Day of Action, Life, and Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Streeck, J. (2018). Grammaticalization and Bodily Action: Do They Go Together? Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 51 (1), 26–32. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413889