- Pragmatics Department, Leibniz-Institute for the German Language, Mannheim, Germany

Research on multimodal interaction has shown that simultaneity of embodied behavior and talk is constitutive for social action. In this study, we demonstrate different temporal relationships between verbal and embodied actions. We focus on uses of German darf/kann ich? (“may/can I?”) in which speakers initiate, or even complete the embodied action that is addressed by the turn before the recipient's response. We argue that through such embodied conduct, the speaker bodily enacts high agency, which is at odds with the low deontic stance they express through their darf/kann ich?-TCUs. In doing so, speakers presuppose that the intersubjective permissibility of the action is highly probable or even certain. Moreover, we demonstrate how the speaker's embodied action, joint perceptual salience of referents, and the projectability of the action addressed with darf/kann ich? allow for a lean syntactic design of darf/kann ich?-TCUs (i.e., pronominalization, object omission, and main verb omission). Our findings underscore the reflexive relationship between lean syntax, sequential organization and multimodal conduct.

Introduction

The core insight into social interaction we owe to Conversation Analysis (henceforth: CA) is the sequential nature of talk-in-interaction (Schegloff, 2007). Yet, research into multimodal interaction has shown that simultaneous relationships between embodied behavior and talk are equally constitutive of action in interaction (Goodwin, 1979). In this paper, we are dealing with a particular kind of simultaneous relationship between talk and embodied action that has not been studied before. We analyze uses of the format darf/kann ich? (“may/can I?”) in German that are produced together with the embodied action that is addressed in the turn itself.

The format darf/kann ich? has different uses, such as, e.g., requests for permission, requests for objects, and offers. By using it, speakers attribute to recipients the right to decide on the future course of joint action. Accordingly, one would expect that the (bodily) action addressed in the darf/kann ich?-TCU1 is produced only after the completion of the turn, i.e., either in the third position by the speaker of the darf/kann ich?-TCU after the recipient's go-ahead or in the second position by the recipients themselves. An example of this type of sequential organization occurs in talk has been closed (l. 03), CS, who has been observing DB and OE working at the stove for a while, asks if she may put the rice into the water, which has started to boil (l. 06). DB, who is cooking, confirms already in overlap (l. 07). CS reconfirms (l. 08) and takes the glass containing the rice (l. 09), which she hands to EW (l. 11), who is standing nearer to the stove and who then puts the rice into the water.

Extract 1: FOLK_E_00300_SE_01_T_01_c5572

In this extract, the request, its granting and its implementation are strictly sequentially ordered: (i) the darf ich?-speaker requests permission for an intended action (Figure 1), (ii) the recipient, who is positioned as deontic authority, gives a go-ahead for the intended action (Figure 2), (iii) the requester reconfirms and produces the intended action (which is completed by a helpful third participant in this case, Figure 3).

However, in our data, the action addressed in the darf/kann ich?-TCU is overwhelmingly not produced after the recipient's go-ahead as in extract (1). Instead, darf/kann ich?-speakers often already initiate or even complete the embodied action addressed with this format simultaneously with their turn, before the recipient produces a second-pair part. An example is extract (2) from a boardgame interaction. GG asks whether she may take a more precise look at the card lying on the table. However, she grabs the card and starts inspecting it before the darf ich?-turn is completed (l. 05) and before her co-players grant permission for the embodied action she has already performed (l. 06-07; see extract (9) for an analysis of this case):

Extract 2: FOLK_E_00357_SE_01_T_01_DF_01_c1384

The relationship between talk and embodied action in such cases is paradoxical both in a sequential and in a pragmatic sense:

• Sequentially, the embodied action does not follow the response that is verbally sought, but precedes it;

• pragmatically, the embodied action presupposes that its permissibility is already intersubjectively established, while the verbal action is precisely devoted to gaining intersubjective assent.

In this paper, we argue that by producing multimodal packages as in extract 2, the speaker bodily enacts a high degree of agency, which is at odds with the low deontic stance they express through their darf/kann ich?-TCU. This embodied display of agency anticipates or even presumes intersubjectivity of the permissibility of the action. Furthermore, we demonstrate how the syntactic design of darf/kann ich?-TCUs is fitted to the embodied resources employed by the speaker, the accessibility of referents, and the projectability of the action addressed with darf/kann ich?

We first summarize the state of the art concerning the relationship of talk and embodied action (section Relationships Between Talk and Embodied Action), agency in interaction (section Agency in Interaction) and “lean syntax” in multimodal interaction (section Lean Syntax in Multimodal Interaction). After introducing the data and methods used for this study (section Data and Method), in section Grammar and Semantics of darf/kann ich?, we provide a grammatical description of the darf/kann ich?-formats under analysis and give a brief overview of prior research on similar formats in other languages. In section Types of Embodied Conduct of darf/kann ich?-Speakers, we show how the degrees of agency and of the presumption of intersubjectivity are tied to the temporal parameters of the coordination between darf/kann ich? and the embodied action. In section Discussion and Conclusion, we summarize our findings, suggest a cline of managing intersubjectivity concerning the permissibility of actions and discuss the reflexive relationship between lean syntax, sequential organization and multimodal conduct.

State of the Art

Relationships Between Talk and Embodied Action

In co-present interaction, multimodal resources are sequentially and simultaneously coordinated, both on the intrapersonal and on the interpersonal plane (Deppermann and Streeck, 2018). Multimodal coordination can take different forms. Multimodal gestalts arise from the coordination of talk and other resources, such as gaze, gesture, body movement, and object manipulation (Mondada, 2014a). Various resources are assembled in methodic ways to orchestrate (contributions to) an overall action in recognizable ways [see also Enfield (2009) on “composite utterances”]. Cases in point are references to co-present objects by the coordination of gaze, gesture, verbal reference, and the focal accent of the turn (Kendon, 1972; Schegloff, 1984; Stukenbrock, 2018), or the closing of a sequence or an encounter by coordinating verbal turns, gaze aversion, posture changes, and walking away (Broth and Mondada, 2013). Multimodal gestalts are not just combinations of multiple resources: They exhibit a temporal order regarding the onset and duration of the use of the individual resources. In such cases, different resources are not precisely simultaneously deployed, but overlap partly; they are adapted to each other in patterns that are characteristic for the multimodal gestalt (Mondada, 2018). Because of the systematic asynchronicity of the multiple resources used, which is distinctive for multimodal gestalts, their boundaries are often fuzzy [see, e.g., De Stefani and Mondada (2021) for transitions]. Resources whose onset precedes others can project the further trajectory of the whole gestalt, thereby enabling recipients to initiate early responses before the completion of the action that the gestalt is to implement (Deppermann et al., 2021).

Talk and other resources, however, can also be devoted to multi-activity (Haddington et al., 2014), such as when talking while driving (Mondada, 2012) or talking during manual work (Deppermann, 2014). Multi-activity can be simultaneous, but there can be other temporal relationships between activities as well (Mondada, 2014b), like fast shifting back and forth between activities, suspending, but not abandoning one activity (Raymond and Lerner, 2014) or completing one activity while already being oriented to the next (Kamunen and Haddington, 2020).

In our study, we demonstrate different relationships between the embodied and verbal conduct of darf/kann ich?-speakers. In section Preparation of Embodied Action + Halt Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Probable Intersubjectivity, we analyze cases in which the embodied conduct projects, but does not already accountably implement the action addressed with the darf/kann ich?-TCUs. In section Completion of Embodied Action Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Certainty of Intersubjectivity, we focus on cases in which the embodied action that is requested by the darf/kann ich?-turn is already produced simultaneously. Building on these findings, in section Discussion and Conclusion, we conceptualize the different temporal relationships between talk and embodied action in terms of a continuum of claiming agency and presupposing intersubjectivity.

Agency in Interaction

In the theory of action (e.g., Davidson, 1980), “agency” is a core notion, distinguishing mere behavior from action. According to Duranti (2004), agency includes (i) intentionality in the basic sense of actions being directed and controlled, (ii) the power to cause effects on other entities, as well as (iii) the moral evaluation of and responsibility for actions and “the possibility of having acted otherwise” (Duranti, 2004, p. 454). While philosophers interested in agency focus on the constitution of actions and linguists consider the properties associated with the semantic role of an “agent” in the representation of event structures (Dowty, 1991), linguistic anthropologists and CA researchers draw on Goffman's concept of “footing” (Goffman, 1981) for analyzing the relationship of agents to their conversational actions (Enfield, 2011; Rossi and Zinken, 2016). For instance, Enfield (2011, p. 304–306) associates the animator-role (producing and controlling the action) and the author-role (deciding on and composing the action) with the agentive quality of “flexibility,” the principal-role (being responsible for and committing to the action) with “accountability” (Enfield and Kockelman, 2017). The notion of agency in social interaction has moreover been tied to the display of epistemic and deontic stance (Raymond et al., 2021) in social interaction. Epistemic agency [see also Heritage and Raymond (2012)] concerns who among the participants has primary or more rights to claim some knowledge and who owns knowledge independently from others. Deontic agency concerns the rights to make a decision (Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012), to direct the future course of the interaction3 and to perform some action independently, i.e., without having been prompted or preceded by others. Claims to high/low agency are brought about by the interplay between the sequential position, participants' epistemic and deontic status, and the linguistic turn-design of an action. The first position has been treated as a default locus of agency, as going first implies “(1) being the one to say it; (2) saying it in the form of an assertion; and (3) saying it independently” (Enfield, 2011, p. 311). Prior CA research has dealt with linguistic practices respondents use against the primacy of first-positioned turns in order to claim high agency in second-positioned turns [see the overview in Raymond et al. (2021), p. 7–10; Enfield (2009)].

While the concept of agency has been used to refer to properties of verbal actions, to our knowledge, its relation to embodied actions remains understudied. The only exception is a study by Tuncer and Haddington (2020) on object transfer in offer/request sequences. Contrasting cases of (not) stretching out the hand to give vs. to take an object, they state that “one participant ‘does more’ to make the transfer possible [and] simultaneously displays agency to make a substantial move in the progression of the action sequence” (Tuncer and Haddington, 2020, p. 66; cf. Zinken, 2015). Who performs and who initiates which kind of body movement here is taken as a display of embodied agency concerning the promotion of and the alignment with a projected course of action.

The uses of darf/kann ich? that we study present a difficult case of enacting agency. The linguistic format displays a low deontic stance, because the recipient is positioned as having to decide on the further course of action. However, the speaker's embodied actions during the realization of the TCU claim high agency by self-initiating or even completing the action that permission or acceptance is sought for (see section Types of Embodied Conduct of darf/kann ich?-Speakers).

Lean Syntax in Multimodal Interaction

In multimodal interaction, “lean syntax” (Deppermann, 2020), i.e., omission of arguments and verbal phrases considered to be obligatory in normative grammars, is pervasive. Depending on their source, omissions have long been distinguished as analepsis vs. ellipsis (Klein, 1993).

Analepsis is a discursive phenomenon: Phrases can be dropped if they have an antecedent in prior talk that is still structurally latent, i.e., accessible and salient to the interlocutors (Auer, 2014, 2015). Analepsis thus rests on sequentiality. Major variants of analepsis are topic-drop (Helmer, 2016) and analeptic responsive actions, e.g., I will, I do in response to polar questions or the provision of a noun phrase instantiating the semantic role that is asked for by a wh-question (Mazeland, 2013; Thompson et al., 2015).

Ellipsis refers to the omission of parts of a clause whose referents are co-present in or recoverable from the situation of the talk [see already Bühler (1934)]. Yet, only few studies have shown how ellipsis is actually used in multimodal conduct and which constraints apply to it. Keevallik (2015, 2018) examines how embodied demonstrations in dance instructions instantiate slots of grammatical objects, adverbs and verbal phrases. In a study on object ellipsis in instructions and requests, Deppermann (2020, p. 285) concludes that perceptual availability of objects and movements, joint attention to them, and the joint orientation to an expectable upcoming practical action create affordances for using ellipsis, whereas the mere spatial co-presence of an object is not sufficient. In addition to perceivability, the relationship of a verbal turn to a joint project of speaker and addressee and its pertinence to the current activity of the addressee is a decisive condition for object ellipsis.

Analepsis, ellipsis and pronominalization by deictic or anaphoric pronouns hinge on the accessibility and salience of referents at the moment of the production of an utterance (Ariel, 1990). In contrast to lexicalization, omission and pronominalization of referents presuppose, and reflexively, index high accessibility of referents.

Projectability of action is another interactional factor that is crucial for syntactic complexity of turn-design. For instance, while non-projectable requests are characterized by the use of different prefatory elements [see, e.g., Taleghani-Nikazm (2006), ch.5; Keisanen and Rauniomaa (2012)] as well as more complex syntactic structure, “minimal” formats for requesting are used if the requested action is a projectable step or next task within the ongoing activity (Mondada, 2014c). Whether such requests are produced nonverbally or with simple noun phrases, depends on whether the referents of the request are projectable [see Rossi (2014, 2015, ch. 2), Sorjonen and Raevaara (2014), Deppermann (2020)]. The degree of projectability of the requested action for the recipient within the joint activity can be indexed by the syntactic complexity of clausal formats like imperatives (Zinken and Deppermann, 2017). Syntactic complexity can also be contingent on the disposition for, or expectation of a preferred answer. In their study on do you want…?, you want…? and want…? formats for offers and requests, Raymond et al. (2020) show that more minimal forms (without pronoun and/or auxiliary) display stronger expectation of a preferred response.

The darf/kann ich?-formats in our study exhibit omission and pronominalization of object arguments and sometimes also verbal phrases. In section Types of Embodied Conduct of darf/kann ich?-Speakers, we demonstrate how such turns build on the sequentially-based accessibility and the mutual visual salience of referents and sometimes also actions, which are indexed to be highly expectable. We also show how the embodied conduct of darf/kann ich?-speakers during turn-production contributes to how these turns are understood by recipients.

Data and Method

The study is based on video-recorded mundane and institutional talk-in-interaction from the publicly available corpus of spoken German FOLK4, hosted at the Leibniz-Institute for the German Language (IDS; Schmidt, 2016), as well as from private corpora. All person and place names have been anonymized; written consent for scientific use of transcribed excerpts and video-recordings was obtained from all research participants. The collection consists of 68 cases of darf/kann ich?-TCUs5. As our study deals with cases in which the embodied action addressed with the turn is initiated before or during turn-production, we excluded darf/kann ich?-TCUs that are produced without the initiation of the addressed embodied action [as extract (1)] or remote actions (e.g., kann ich's nachher haben? “can I have it afterwards?”) as well as instances with verba dicendi (e.g., kann ich etwas sagen?—can I say something?) and stative verbs (e.g., kann ich die Socken so lassen? “can I leave the socks like that?”). This generated a collection of 43 target cases. Our analysis draws on the methods of multimodal CA and Interactional Linguistics.

In our analysis, we distinguish two phases of embodied action addressed with darf/kann ich?-TCUs:

By “preparatory phase” we mean both (i) preparatory actions that establish (bodily, material) pre-conditions (Schmidt, 2018) for an intended core action as well as (ii) its actual initiation. “Initiation” refers to what Kendon (2004) calls the “preparation-phrase” of the core action proper before its actual accomplishment. Accordingly, the project of “stirring meat in a pot” can involve the following actions: (1) preparatory phase: taking a spoon (preparatory action) and moving the spoon toward/into the pot (initiation); (2) core action: stirring the meat. The reason for using “preparatory phase” as a broader term for both preparatory action and initiation lies in the fact that both make the core action strongly projectable, while not yet implementing it in a full, accountable way. Moreover, because there are differing degrees of granularity with respect to action ascription and because embodied actions are often subject to transition during their course, the segmentation of embodied action is not always straightforward.

Grammar and Semantics of darf/kann ich?

The focus of this study is on interrogative formats produced with either the modal verb dürfen (“may”) or können (“can”) in the first person singular. By using these formats, speakers position the recipient as having primary rights to decide upon future actions of the darf/kann ich?-speaker. However, the type of rights (e.g., epistemic or deontic), or the external source of authority are not explicitly addressed with the formats (cf. Kratzer, 2012).

In this study, we distinguish between two formats: [darf/kann ich + predicate?] and [darf/kann ich?] without a predicate (henceforth: bare uses). In both formats, the modal verb is inflected for first person singular in simple present indicative mood. [Darf/kann ich + predicate?] exhibits a (transitive or intransitive) main verb and/or one or more arguments (including oblique cases) fitted to the valence frame of the main verb:

The format can be produced either with falling or rising turn-final intonation. The V1-word-order marks these utterances as interrogatives.

Bare uses of darf/kann ich? do not exhibit a predicate, i.e., neither a full verbal phrase including a (transitive or intransitive) main verb, nor any argument. They may, however, exhibit modal particles (e.g., mal):

Bare uses of darf/kann ich? usually exhibit rising turn-final intonation.

While there is no research on bare uses of the format, the full format—depending on the main verb and the interactional context—is typically associated with requests for action (i.e., object transfer; Fox, 2015; Zinken, 2015) and requests for permission. Thompson et al. (2015, p. 215–6) argue that both how deontic rights are distributed and who is going to carry out the action addressed with such turns are the most important factors for differentiating between these two actions (cf. Zinken, 2015, p. 25–8). Levinson (1983, p. 357–363) analyzes formats like “Can I have/get…?” as pre-requests (position 1) designed to get a granting response (position 4). However, Fox (2015) shows that in institutional settings this format rather works as request for action, with recipients displaying an immediate verbal and embodied orientation toward compliance [see also Fox and Heinemann (2016)]. Zinken (2015) demonstrates that by requesting an object transfer with “can I have X?” speakers treat recipients as being in control over a “shared good,” obliging them to make the object available. Such requests are often produced with a reaching-out gesture, which underscores the requester's entitlement to the object and their agency over the course of action (Tuncer and Haddington, 2020).

Types of Embodied Conduct of darf/kann ich?-Speakers

Preparation of Embodied Action + Halt Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Probable Intersubjectivity

In this section, we demonstrate how darf/kann ich?-speakers orient on both linguistic and embodied levels to the recipient's higher deontic rights over the future course of action. At the same time, speakers display by their embodied action a high certainty concerning the expectation that their request will be granted. We present four cases of darf/kann ich?, which are used either to request permission or an object transfer. In all these cases, the darf/kann ich?-speaker initiates the preparatory phase of the embodied action addressed by the turn before or during the initiation of the turn. The core action, however, is not being initiated until the response is produced. We begin our analysis with cases of [darf/kann ich + Predicate?] (section [darf/kann ich + Predicate?]) and then proceed to cases of bare [darf/kann ich?] (section Bare [darf/kann ich (mal)?]).

[darf/kann ich + Predicate?]

Extract (3) comes from the beginning of the first practical driving lesson of STU (student). When being instructed on how to use the indicator, STU turns off the indicator too firmly, thereby inadvertently indicating to the left. Afterwards, the instructor (INS) explains how STU's problem has emerged (1.01-02). As soon as the end of the instructor's explanation becomes projectable, STU shifts her gaze from INS to the indicator and asks whether she can try to turn the indicator on once again (1.03):

Extract 3: FOLK_FAHR_02_05_2:13

The kann ich?-turn requests permission for the speaker's own intended action and makes a verbal go-ahead relevant from the recipient (1.05-06). Using this format, STU conveys a low deontic stance (Stevanovic, 2018) and positions INS as having primary rights to decide upon the future course of action, which fits into the interactional environment in which the request is produced. In terms of the participation framework, the instructor is the one who guides the training session and owns the car. In terms of its local placement, the request for permission is produced in turn-final overlap with the instructor's explanation. Thus, STU is in a deontically lower position, both with respect to deciding on the intended action in general and whether she is allowed to perform it at this particular moment. The speaker's orientation toward the recipient having higher deontic rights is also displayed by the student's embodied conduct: From the very onset of her request for permission, she moves her left hand toward the indicator. However, she halts and “freezes” her gesture, i.e., she neither touches nor turns the indicator lever until the instructor produces a go-ahead [see Rossi and Stivers (2020) for similar cases of halting category-sensitive actions].

Extract (3) shows a distinctive pattern of coordinating embodied action with a darf/kann ich?-request: Speakers initiate the preparatory phase of the intended action before or during turn-production. However, the projected action is suspended, the core action being initiated only when the request has been granted. By initiating a preparatory phase of an action, speakers show their expectation that no possible contingencies will occur in this particular context and that a preferred response, i.e., that a go-ahead is probable [cf. Zinken (2015), cf. Kendrick and Drew (2016), p. 9–10 on initiating an embodied action before the trouble is verbally addressed by the recipient]. Moreover, the embodied initiation of the intended action before its permission allows the speaker to complete the action immediately as soon as the request is granted. This supports the smooth and quick progression of the sequence. The unproblematic nature of the intended action is also confirmed by INS's response: In granting permission with ja gern (1.08) and na klar (1.09), INS not only “acquiesces” to the terms of STU's request (Heritage and Raymond, 2012), but also treats permission as taken for granted, or redundant (Auer, 2020, p. 268 on klar). This is in line with the multimodal resources employed in the instructor's response: Raised eyebrows (Ekman, 1979), eye blinking (Hömke et al., 2018), and shoulder shrug (e.g., Jehoul et al., 2017) index the answer to be obvious.

In our data, if the preparatory phase of the embodied action is initiated before or during the production of the darf/kann ich?-TCU, object referents of the turn are usually salient to both parties, because they are jointly attended to. Sometimes, they have already been mentioned in the immediately prior turn(s). This salience is reflected by the turn design: In extract (3), the temporal adverb nochmal (“once again”) and the pronominal object es (“it,” referring to operating the indicator) used in the kann ich?-TCU index that the student asks to perform the same action as she did before and that is currently being talked about by the teacher.

Whereas in extract (3) the preparatory phase is “frozen” until the go-ahead from the recipient is produced, extract (4) demonstrates that the preparation of the embodied action can be timed in such a way that the granting response comes already before the embodied action reaches its core phase. Anna (AG) and Nathalie (NR) are cooking dinner together. AG is making a salad dressing. In line 02, NR asks AG whether the salad dressing tastes good and looks at the bowl with the dressing. In response, AG treats this question as a pre-request by offering NR to try it (1.04). Already with the onset of AG's offer, NR starts approaching AG. NR accepts the offer with a response token ja, (“yes,” 1.06) and immediately continues with a darf ich?-TCU:

Extract 4: FOLK_E_00225_SE_01_T_02_DF_01_c4908

During the production of the darf ich?-turn, before saying “FINger,” NR starts moving her finger toward the dressing. The targeted location is referred to by the directional pronoun rein (“into-it”), indexing that the object is accessible both deictically (both participants look at the dressing) and anaphorically (the dressing has been the topic of the immediately preceding talk). In response, AG stops stirring the dressing and moves the fork aside, thus making space for NR to put her finger in. This embodied response projects a go-ahead, which follows directly (ja “yes;” 1.07). Immediately after AG's embodied projection, NR alerts AG to the fact that NR will now put her finger into the bowl by saying mach_s (“I'll do it”). This seems to indicate that she interpreted NR's embodied conduct as a go-ahead. Right after AG's verbal go-ahead (1.07), NR produces a third positioned OKAY in line 09, indexing that she registers the permission, and touches the dressing. The trajectory of NR's gesture toward the dressing is slow and finely timed in relation to the production of the darf ich?-turn and AG's response. This allows NR not to halt her embodied action before the response. Its continuous action trajectory indexes high certainty that permission will be given. Still, like in extract (3), the core action, i.e., putting the finger into the dressing, is not carried out until her request is granted. Thus, the darf ich?-speaker orients both verbally and nonverbally to the recipient as having higher deontic rights. While in extract (3), rights to control the activity can be explained by the participant's roles in the overall activity, in extract (4), the deontic asymmetry is tied to a local interactional level. First, by putting a finger into the dressing, NR interferes with AG's local project, which AG has to suspend to allow NR to taste the dressing. Second, AG holds the bowl, therefore NR has to intrude into AG's personal space to taste the dressing. Third, touching the dressing with a finger could be seen as an uncivilized act, especially given that both participants will eat it afterwards. This action might require explicit agreement, or negotiation about norms of appropriate tasting-behaviors, which cannot be presupposed.

Bare [darf/kann ich (mal)?]

Bare uses of darf/kann ich (mal)? can be coordinated with embodied actions in the same temporal ways as shown in section [darf/kann ich + Predicate?]. Furthermore, like cases presented in the prior section, the bare format [darf/kann ich?] is also used when the speaker's embodied action is about to intrude into the recipient's “territories of the self” (Goffman, 1971, p. 28–61), i.e., the intended action concerns an object that is owned by or in bodily control of the recipient or a project the recipient is responsible for. Yet, the environment, in which the format occurs, is different. In particular, the embodied actions addressed with the bare darf/kann ich?-TCU are highly projectable, either by virtue of the speaker's embodied conduct or the prior sequence. A case in point is extract (5), in which Saskia (SP), Roman (RP), and Lisa (LH) are baking a cake. LH had stated that her mixer is very expensive and that it's therefore good that RP is going to stir with a whisk (1.01). After SP is done with adding the eggs into the bowl, she turns to RP, shifts her gaze to the whisk that RP is holding, reaches with her right hand for the whisk (Figure 5) and produces a darf ich?-turn (1.05):

Extract 5: FOLK_E_00372_SE_01_T01_c230

The darf ich?-turn does not contain any arguments and does not mention the action. The action that is expected from the recipient is disambiguated by the embodied resources SP employs, namely, her bodily turn toward RP, her gaze at the whisk and her reaching-out gesture (1.06). Like in extracts (3) and (4), the initiation of embodied conduct during the darf/kann ich?-turn displays the speaker's expectation that a preferred response is probable, and supports activity progression. Yet, in extract (5), the requested action is an object transfer. Object transfers require the recipient's collaboration in form of giving the object, which is reciprocal to the requester's taking it (Heath et al., 2018; Tuncer and Haddington, 2020). The embodied initiation of the object transfer disambiguates or completes the verbal turn: The verb-slot and the object-argument-slot are filled by the direction of the grasping gesture, the speaker's gaze direction also clarifying the referent (the whisk). Furthermore, as SP is done with adding all ingredients right before the initiation of the darf ich?-turn, the next expectable step in this activity is mixing, for which the whisk is necessary. This contributes to the fact that the action requested in line 13 is easily recoverable.

The use of darf ich? in extract (5) can be explained by the fact that although SP is responsible for adding the ingredients to the bowl, it is RP who is responsible for mixing them with a whisk, as stated in line 01 as well as at the very beginning of this cooking activity. Furthermore, the whisk is in RP's personal space, as he is holding it. Thus, by constructing the turn with darf ich?, SP orients to RP's higher deontic rights grounded in his “control” over the project of stirring as well as the object. This is also displayed by SP's embodied conduct: Although she reaches out for the whisk (Figure 5) and claims higher agency over the ongoing course of action (Tuncer and Haddington, 2020), she neither grabs nor touches it until RP collaborates (Figure 6), i.e., initiates the action of “giving,” which is the second compulsory element of a collaborative object-transfer (Heath et al., 2018). That SP intrudes into RP's project is also oriented to in RP's verbal response (1.07): By giving his go-ahead saying verSUCH_s, (“try it”), RP treats the prior turn not as a request for action, but for permission. In doing so, he reclaims his agency, or “control,” over the course of action.

In extract (6) from a sales encounter in a perfumery, darf ich? relates to a different “territory” of the recipient, namely, her personal space. Before the extract, the customer (CU) said that she needs some time to think whether she wants to buy the perfume the seller (SE) had recommended. In line 01, SE offers to spray the perfume on CU. After relatively long pauses (1.02, 04) and a hesitation marker (ähm “uhm,” 1.03), which project a dispreferred response, CU reluctantly accepts (so ganz LEICHT,=ja, “like very slightly yes,” 1.06). In turn-final overlap, SE initiates a darf ich?-turn:

Extract 6: FOLK_VERK_07_A01_T01_20:05-20:24

Already during CU's hesitation marker ähm (“uhm,” l. 03), SE grabs the perfume flacon and looks at CU. At the beginning of CU's reluctant go-ahead (l. 05), SE takes the lid off the perfume flacon. The particle so in CU's response projects a specification of the manner, in which the action on offer is to be done. It thereby projects (conditional) acceptance of the offer. After CU starts nodding (l. 05), SE shifts his gaze to the flacon and produces a darf ich?-turn. While producing this turn, SE puts his index finger on the trigger, but does not start moving the flacon toward the customer before her response (Figure 7). In doing so, the seller orients to the customer's deontic authority, as spraying the perfume implies the intrusion into the client's personal space (i.e., private smells). In response, CU gives a go-ahead ja (“yes,” l. 08), steps forward and closes her eyes (l. 09 Figure 8). She thus adopts a posture to receive the spray. Right after the onset of her go-ahead and her bodily repositioning, SE starts spraying (l. 09). Thus, CU's verbal go-ahead (l. 08) as well as SE's initiation of spraying only after CU's go-ahead and her embodied display of readiness provide evidence that both participants orient to the darf ich?-turn as a request for permission. However, given that the customer has already granted permission to spray the perfume on her in line 05, the darf ich?-turn (l. 06) rather addresses the permissibility of initiating the action at this particular moment. In addition, it announces that the action will now be performed. This is important since the customer's bodily collaboration is required: She must approach the seller (l. 08), close her eyes (l. 09) and stop breathing in when spraying (Figure 8). Interestingly, SE initiates spraying by grabbing the flacon already in line 03 despite clear evidence of a projectable dispreferred response from the recipient (l. 02-04). His embodied conduct does not align with the course of action projected by the recipient's conduct and instead counter-factually treats granting as being highly expectable. By initiating the offered action, he claims agency, puts the customer under pressure to accept the offer and increases the face-threatening character of rejecting the offer (Brown and Levinson, 1987), because the offerer has already put effort into carrying out the offered action.

Like in extract (5), the lean turn design of bare darf ich? fits its interactional environment in extract (6): The action of spraying can be expected because it has been explicitly offered in the preceding context (l. 01). It can also be anticipated to be planned due to the embodied conduct of the seller (“frozen” hold of the flacon and gaze at it; l. 06-07). This does not only constrain the intended action, but also establish the focus of joint attention (Figure 7). Thus, the arguments of the turn and the intended action are both analeptically and deictically salient.

In this section, we have shown that in formatting their actions with darf/kann ich?, speakers orient to the intended action as affecting something in the recipient's “territory”– the authority associated with their social role [extract (3)], their responsibility for the project [extract (4)], or their personal bodily space [extracts (5–6)]. This orientation is also displayed in the speaker's embodied conduct during darf/kann ich?-TCUs: The core action is carried out only after a verbal [extracts (3), (4), (6)], or nonverbal [extracts (4–6)] go-ahead from the recipient. Yet, by initiating the preparatory phase of the intended action already before or during the production of the darf/kann ich?-TCU, speakers display that they presuppose a complying response as being probable. The initiation of the action before the response promotes the progressivity of the activity, allowing for quick continuation of the intended embodied action immediately after the recipient's assent. The linguistic design of darf/kann ich?-TCUs treats referents, and, in the case of bare darf/kann ich?-TCUs, actions as mutually salient. Accessibility of referents and/or actions is indexed by pro-forms [extracts (3–4)] or omission of object arguments and/or the full verb [extracts (5–6)]. Especially in cases of bare uses of darf/kann ich?, the unambiguous interpretation of action and object rests on joint attention to the object and on the embodied initiation of the preparatory phase of the action. Sometimes, it is additionally supported by topicalization in prior talk, whereas “the verbal segments on their own would be incomplete and incomprehensible” (Keevallik, 2018, p. 15; cf. Keevallik, 2015). This is also supported by the fact that in contrast to [darf/kann ich + predicate?], bare uses of darf/kann ich? in our collection are never produced without an embodied initiation of the intended action. In bare uses, thus, the prior expectability and/or the perceptual salience and recoverability of the action that the darf/kann ich?-TCU refers to is greater than in at least some of the cases of [darf/kann ich + predicate].

Completion of Embodied Action Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Certainty of Intersubjectivity

In section Preparation of Embodied Action + Halt Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Probable Intersubjectivity, we showed cases of darf/kann ich? in which speakers initiate the preparatory phase of the requested action, yet waiting to perform the core action only after the recipient's granting of the request. In doing so, speakers display that the permissibility of the addressed action was presupposed to be probable, but contingent on the recipient's response. In this section, we show cases of a greater incongruence between the agency claimed through verbal vs. nonverbal resources by darf/kann ich?-speakers. We analyze four cases in which speakers initiate not only the preparatory phase, but also the core action referred to in darf/kann ich?-TCUs before the recipient's response.

[darf/kann ich + predicate?]

Extract (7) comes from another driving lesson. Here, STU has been driving for about 19 seconds behind two cyclists, who are very slow. They have to be overtaken as soon as possible (l. 01-2), because there is currently no oncoming traffic. After INS has looked five times at STU, STU asks whether he may overtake the cyclists by using a darf ich?-format (l. 03):

Extract 7: FOLK_E_00146_SE_01_T_01_DF_01_c664

The choice of darf (“may,” l. 03) may highlight that the question concerns the right in accordance with the code of traffic and not a personal permission by the instructor. Still, INS is treated as epistemic authority for the correct interpretation of the deontic rules. Jetzt (“now”) indicates that the question concerns the permissibility of overtaking at this precise moment. Like in extracts (3–6), the object-referent (the cyclists) is deictically salient, which is indexed by the demonstrative pronoun die (“them;” l. 03).

INS had been looking at STU already six times before the onset of STU's turn in line 03. Looking at STU is a routine way for INS to index that some action is expected from STU. STU touches and then turns the indicator lever down and looks into the left side mirror, thus preparing to overtake (Deppermann et al., 2018). In contrast to the cases in section Preparation of Embodied Action + Halt Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Probable Intersubjectivity, the core action–the actual passing maneuver–is initiated before the darf ich?-turn is completed and way before the recipient's go-ahead in line 7. While STU's darf ich?-turn treats INS as deontic authority, his embodied actions display that STU himself is entitled to decide on his further course of action. By initiating the core embodied action before INS's go-ahead, STU claims high agency and presupposes intersubjectivity, i.e., that the permissibility of the passing maneuver is certain, thus not being in need for granting. This is confirmed by INS' later responses. His go-ahead treats the need for the requested action as obvious and the prior question as redundant (ja klar “yes sure,” l. 07) and the initiation of action as too late (l. 09–11). After the passing maneuver (l. 35–38), INS states that the student is expected to be already sufficiently competent to initiate actions such as overtaking on his own without having to ask for permission. In doing so, he criticizes STU for lacking to take autonomous actions, which is something that should already be established as a routine.

The multimodal realization of the darf ich?-turn poses a riddle concerning the action accomplished by STU: If considering only the verbal component as well as INS's responses, the darf ich?-turn seems to accomplish a request for permission. However, given the embodied action, i.e., the initiation of the core component of the action addressed by the darf ich?-turn before a second-pair part has occurred, STU's turn could also be interpreted as an announcement of the passing maneuver, while simultaneously checking its legitimacy.

In extract (7), the grantability of the action addressed with the darf ich?-turn seems to be secured on the basis of the high expectability of the action. Speakers can also initiate an action before a response after they have checked that there are no possible contingencies that would jeopardize the permissibility of the action. This is the case in extract (8) from another driving lesson. Here, STU stops the car and INS announces that the first stage of the drive is now complete (l. 01–03). In line 04, INS looks back. As becomes clearer in the following sequence, her gaze backwards aims at checking if she may move her seat backwards without disturbing the person sitting behind her (AL). Afterwards, she asks AL whether she can move her seat (l. 05):

Extract 8: FOLK_Fahrschule_FOLK_FAHR_02_A01_18:55_29:33

Already at the beginning of the kann ich?-turn, INS starts bending down toward the lever of her seat. She touches it by the end of the turn. Immediately after this preparatory action, she initiates the core action and starts pushing her seat back before the recipient's response (l. 06). As INS's moving the seat backwards intrudes into AL's personal space, INS's kann ich? seems to reflect that this imposition needs AL's permission, even if INS has already checked that AL will not be affected. Moreover, n stück (“a bit”) downgrades the imposition as not demanding much space. Like in extract (7), the core embodied action addressed with the kann ich?-turn starts before the recipient's response (l. 06). This indexes that intersubjective permissibility of the action is presupposed to be certain. The kann ich?-turn can be interpreted as two actions: either as a request for permission, if considering only the verbal sequence, or as an announcement, if taking INS's multimodal conduct into account. The announcement displays consideration of the recipient's imposition by preparing her for an upcoming action, which could be seen as an intrusion into her territory and/or as unexpected and perhaps even startling, if she is not prepared for it.

In some cases, however, the grantability of the addressed action is not established prior to it. Yet, by completing the action before recipient has granted permission, speakers can nevertheless construct the action in such a way as if permissibility was secured. This is shown in extract (9), in which four participants play the card-game “Dixit.” Before the beginning of the extract, Vanessa (VP) places four cards on the table (l. 01). In line 02, Gabriele (GG) starts intensely attending to one card. She leans forward toward it (l. 03), which can be interpreted as an embodied display of trouble (Kendrick and Drew, 2016). In line 04, she produces a request for information (was IS_n des. “what is that”) by simultaneously reaching out for the card she has been attending to (Figure 9), followed by a latched darf ich?-question whether she might take a closer look (l. 05).

Extract 9: FOLK_E_00357_SE_01_T_01_DF_01_c1384

GG's question in line 04 accounts for her embodied actions (display of embodied trouble + grasping the card) and is a preliminary to the darf ich?-TCU. GG grasps the card already at the onset of darf ich? (l. 05) and holds it closer to herself before the TCU is even completed (Figure 10). The request is not addressed to anyone in particular in this multi-party situation. GG gazes exclusively at the card throughout the whole extract. The use of genau (“precisely,” l. 05) self-reflexively accounts for the request by indexing the presupposition that she cannot recognize the picture on the card sufficiently from her position. The object (i.e., “card”) is omitted, as the reference is unambiguous by her gaze and the grasping gesture. The modal particle mal could be seen to index that the action/request is not necessarily expected by the others (Zinken and Deppermann, 2017).

In contrast to extracts (7) and (8), in this case, the core action is not only initiated, but already completed before the recipients have granted the request. The darf ich?-format seems to be devoted to making the action accountable–she takes the card, because she cannot recognize it properly– rather than to asking for permission. Still, the darf ich?-TCU opens a response slot, i.e., it enables the others to grant permission for her action, even if only belatedly. In this way, GG symbolically attributes authority to the other players, which is, however, not behaviorally consequential.

By completing the action before the recipients' response(s), GG treats its grantability as presupposed and unproblematic. However, we find no sequential evidence that the permissibility of this action is secured. We argue that this is what the recipient's responses (l. 06–07) might orient to: Despite the fact that all players see that the action is already completed, they treat GG's darf ich?-TCU as request for permission and reinvoke their authority and agency over the course of action, which was undermined, or ignored by GG's embodied conduct. In particular, RM's partial repeat (DARFST du, “you may,” l. 07) reclaims her deontic rights by “confirming” rather than merely “affirming” the proposition of the prior question (Heritage and Raymond, 2012, p. 187; Enfield et al., 2019).

As in other cases in our collection, we could observe in extract (9) that recipients give permission to a darf/kann ich?-TCU although the embodied action addressed in the TCU has already been executed (or is in the course of being performed). For the practical purposes of sequence progression, this permission is gratuitous, because progression is already effectuated independently from it. So why would recipients give permission nevertheless? One explanation might be that the conditional relevance of granting permission established by the darf/kann ich?-TCU may impose itself as a routine and/or a normative requirement to maintain the interactional order. Reflexively, the recipient's action of granting confirms the normative validity of this order, in spite of the darf/kann ich?-speaker's embodied action, which has just violated this order. With regard to the interpersonal relationship between participants, recipients can be seen to counter-factually reassert their agency as having deontic authority, especially if their go-ahead is formatted in an upgraded way, e.g., by an imperative as in extract (5), l. 07 or a partial repeat as in extract (9), l. 07. At the same time, by giving permission, recipients reinstate intersubjectivity by sanctioning the darf/kann ich?-speaker's preceding embodied action, as if it depended on their assent.

Thus, we have shown that by producing the darf ich?-TCUs, speakers offer the recipients a response space for granting the request and orient to the permissibility of the embodied action as being potentially contingent on the recipient. Still, by initiating, or even completing the core embodied action before the recipient's response, speakers treat the grantability of the action as presupposed and not contingent on the recipient's uptake. In doing so, they enact a high degree of agency by unilaterally progressing the course of action.

Bare [darf/kann ich (mal)?]

In the previous section entitled Bare [darf/kann ich (mal)?], we analyzed cases in which the darf/kann ich?-speaker initiates the preparatory phase of a requested embodied action, but does not intrude into the recipient's personal space before their granting response. In this section, we show cases in which darf/kann ich?-speakers cannot carry out an intended action, because recipients “stand in their way.” Thus, after initiating the preparatory phase, speakers do not halt the embodied action, but intrude into the other's personal space (e.g., by touching the recipient) in order to make the recipient adjust their bodily position.

In extract (10), Saskia (SP), Lisa (LH), and Roman (RP) are baking a cake together. We join the interaction in the very beginning of the cooking activity. In line 02, SP announces that she will wash her hands and starts approaching the sink. Yet, RP who stands in her way, does not yield space and instead observes LH's preparation of the dough. As SP arrives immediately behind RP and cannot move toward the sink (Figure 11), she produces the darf ich?-turn (l. 04):

Extract 10: FOLK_E_00372_SE_01_T_01_194

By using darf ich?, SP orients to the fact that the requested action intrudes into the personal space of RP (Figure 11) and forces him to interrupt his current activity (watching LH's preparations). Additionally, the modal particle mo seems to treat RP as being not prepared to give way, the request interfering with his current action–as can be seen by the fact that he did not react to SP's announcement of her action plan in line 02. SP's intended action is not named in the darf ich?-turn, because it is recoverable from the announcement and from SP's movement toward the sink.

SP advances her course of action and claims high agency. RP does not produce any verbal response, but is nonverbally compliant by adjusting his position (l. 05–06): He gives way and raises his arms (Figure 12), displaying in a stylized manner that he does not want to interfere with SP's course of action, i.e., stand in her way. Both SP's non-verbal conduct and RP's response treat the darf ich?-turn as implementing a request for action. As SP has already announced her action goal in line 02, the darf ich?-turn also works like an insisting reminder deemed for mobilizing a response that was lacking.

In extract (10), darf ich? is used with regard to an action that could have been anticipated by the recipient based on the prior sequence. The request is directed at a recipient who is blocking access to shared goods. This is also the case in extract (11). Rebeca (RE), Melanie (ME), and Jonas (JO) are having breakfast together. While producing an account for why she has not returned a sweater to ME, RE is putting butter on her bread (l. 01–03). Then she takes a slice of cheese and moves her hand toward the cutting board (l. 03), on top of which ME is resting her hand (Figure 13). ME doesn't seem to notice what RE is up to, as ME gazes at the plate before her. RE starts to remove ME's hand and immediately afterwards produces the kann ich?-turn (l. 04):

Extract 11: EMB_Teilchenessen_2016_2

Like in extract (10), the kann ich?-turn acknowledges that RE intrudes into ME's personal space by touching and pushing her hand away from the cutting board. The modal particle mal indexes that RE takes ME not to be prepared for the request (cf. Deppermann, 2021). RE's body movement projects that she intends to use the board for cutting the cheese. The particle bitte: (“please”) marks the action as a request and has been claimed to index deference (Brown and Levinson, 1987). It is prosodically marked through lengthening of the last syllable and the focal accent. As ME has been using the cutting board, which is a shared object, as her plate (despite the fact that she has one of her own), bitte: might convey a critical stance toward ME's behavior and her lack of anticipation that RE needs the board. This could also have been guessed by virtue of RE's earlier embodied actions in the project of making a sandwich (l. 01–03).

RE's embodied conduct before and during the realization of the kann ich?-turn displays the claim to high deontic rights and agency over the course of action. As soon as RE has nudged ME, ME withdraws her hand (Figure 14). She neither gives any verbal response nor does she express any visible stance on the episode. Therefore, given the nonverbal conduct of the kann ich?-speaker as well the recipient's response (i.e., non-verbal compliance), kann ich? accomplishes a request to adjust the embodied position and give access to the shared good.

Like in the previous section Bare [darf/kann ich (mal)?], bare darf/kann ich? is used for actions that are highly projectable not only because of the prior sequential context, but by virtue of the speakers' embodied conduct before and during production of the TCU. Still, in this section we demonstrated that speakers can use bare darf/kann ich? for a specific type of requests for action, namely, that the recipient adjusts their bodily position in order to allow recipients to complete their initiated course of action. This occurs if recipients restrain the speaker's access to shared goods, objects or facilities through their embodied position (cf. Zinken, 2015). In such cases, darf/kann ich?-speakers initiate an embodied action before the production of the darf/kann ich?-TCU and intrude into the personal space of the addressee without waiting for compliance. By using darf/kann ich?, speakers index that they understand their action to be violating the recipient's personal space (cf. section Bare [darf/kann ich (mal)?]). However, by continuing the embodied action, darf/kann ich?-speakers treat permissibility as intersubjectively certain and claim high agency over the course of the joint action.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that the degree of agency and the deontic stance that a participant claims by their actions can be systematically equivocal. We have analyzed a seemingly paradoxical package of a verbal turn produced in sync with an embodied action: While the darf/kann ich?-format of the TCU indexes low agency of the speaker and attributes deontic authority concerning the course of action to the addressee, the embodied action exerts high agency. If A6 initiates the embodied action that intrudes into B's “territory,” but suspends it before B grants the embodied action, B's permission is treated as probable (section Preparation of Embodied Action + Halt Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Probable Intersubjectivity); if A bodily intrudes into B's territory before B grants permission, B's permission is presupposed as being certain and unproblematic (section Completion of Embodied Action Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Certainty of Intersubjectivity). Through the analysis of these two different ways of coordinating embodied action and verbal action, we were able to show that embodied agency, which has almost never been attended to before in CA [except for Tuncer and Haddington, 2020], can be as important for interactional organization as verbal agency. We also demonstrated that high agency is not automatically tied to first actions. Darf/kann ich-TCUs are first actions that initiate sequences; yet, they index that deontic authority concerning (future) actions is ascribed to the addressee, thus subordinating A's agency to B's. Future research might inquire more into the relationship between sequential position, action type, linguistic and embodied resources in claiming agency in social interaction.

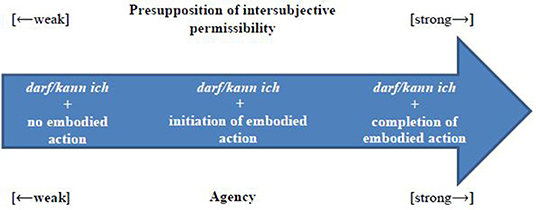

Putting our observations into a larger picture, we can locate the two variants of relationships between talk and embodied action, on a larger continuum concerning the degree of presupposition of permissibility and claims to agency. The temporal placement and the design of the embodied action, in particular the temporal organization of preparatory parts of the embodied action and the core action itself, is crucial in these respects. The temporal coordination between the trajectory of the embodied action and the darf/kann ich?-TCU indexes the assumed intersubjective status of permissibility, impinges on the exertion of agency and affects the ascription of deontic status to the participants in the sequence. We can posit three positions on this continuum (see Figure 15 below):

(1) At one extreme, there are cases in which A does not presuppose the intersubjective permissibility of the action A intends to perform. A ascribes deontic authority and sequential agency fully to B. This results in a strictly linear, sequentially organized negotiation of the permission and execution of the action [see extract (1)]:

– A: darf/kann ich?

– B: verbal/nonverbal granting

– A: initiation of both preparatory and core embodied action

(2) If A initiates the embodied action already while producing the turn, but suspends it before the B's granting (section Preparation of Embodied Action + Halt Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Probable Intersubjectivity), A indexes that permissibility is treated as being highly probable. By this, A claims agency by their embodied action, yet both the turn and the suspension index that the final decision on permissibility is left to B:

– A: darf/kann ich? + initiation of preparatory action

– B: verbal/nonverbal granting

– A: initiation of core action

(3) If A executes an embodied action intruding into B's territory before B grants it, A presupposes that permissibility of the addressed action is intersubjectively shared and doubtless (section Completion of Embodied Action Before Confirmation: Presupposition of Certainty of Intersubjectivity). By this, A claims high agency and does not assign B any sequential agency concerning A's next action. Yet, the darf/kann ich?-TCU shows an orientation to the need to intersubjectively account for the action (at least in terms of its intelligibility or expectability) and to ritually acknowledge B's deontic rights, even if in a way that is not behaviorally consequential. This paradoxical format thus can be seen as factually acting unilaterally, while indexing to be committed to an intersubjective normative order.

– A: darf/kann ich? + initiation of preparatory and core action

– B: verbal/nonverbal granting7

Figure 15: Continuum of presupposition of intersubjective permissibility and agency in relation to speakers' embodied conduct during darf/kann ich?-TCUs

The presuppositions concerning intersubjectivity are also reflected by the design of the darf/kann ich?-TCU. Its complexity depends on the multimodal interactional environment in which the turn is produced. In all cases of darf/kann ich?-TCUs that co-occur with (the beginning of) the embodied realization of the action, referents involved in this action have already been salient to B before A's turn-beginning because of joint attention (visual or haptic access of B) and/or because they have been mentioned in the preceding talk. The high degree of accessibility of the referents allows for pronominalization or omission of object arguments, and sometimes also the main verb. Often, the perceptual and the sequential sources of accessibility co-occur, thus yielding turns in which a distinction between deixis and anaphor or between ellipsis and analepsis is not possible. In the case of bare darf/kann ich?, it is not only the object that is salient, but in addition, the embodied action to be performed is highly projectable in the context of a routine sequence or series of actions (mainly object transfer to A or letting A pass). In such cases, the embodied action accompanying darf/kann ich?-TCUs disambiguates their meaning sufficiently and provides the elements which could be seen to be missing when considering the turn alone. Thus, our results deepen our understanding of how multimodal action allows for lean syntax (i.e., argument and main verb omission), which, in turn, indexes the presupposition of the intersubjective accessibility and expectability of referents and actions.

The kinds of coordination patterns between turn and embodied action that we have examined in this paper do not seem to match the concepts that have hitherto been developed for analyzing multimodal packages. Darf/kann ich?-TCUs during which the verbally addressed embodied action is already bodily initiated or even completed are neither composite utterances (Enfield, 2009) nor multimodal gestalts (Mondada, 2014a), because the linguistic and embodied resources do not work together to bring one overall action about. Instead, verbal and embodied action clearly implement (or prepare) two different actions. The embodied action pragmatically belies the verbal turn, as the action for which permission is sought, is already in progress. Embodied action and talk mutually elaborate each other (Goodwin, 2000): The embodied action indexes claims to permissibility and certainty of a confirming response regarding the action that the turn targets; the turn makes clear what the embodied action is up to. Yet, they are not instances of multi-activity either, because both actions belong to the same activity. They contribute to the same line of action. However, while the verbal action starts a new sequence, the embodied action that is simultaneously produced with it, anticipates the third position within the same sequence. While it has been repeatedly shown that asynchronicities of different modalities in implementing actions are common (e.g., Mondada, 2018), it is a novel finding that, relative to a verbal action initiating a sequence, a simultaneous embodied action by the same participant can already implement a third position before a response, i.e., the second position, has occurred. We are thus faced with a sequential shortcut in favor of progressivity—yet, at the expense of accomplishing intersubjectivity by reciprocal negotiation. Future research on multimodal interaction will need to show whether such reversals or anticipations of the order of actions within a sequence are a more general potential of assembling different bodily resources in multimodal conduct.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found online at: dgd.ids-mannheim.de Database of Spoken German, Forschungs- und Lehrkorpus gesprochenes Deutsch (FOLK), except for extract 11, which is from a private corpus.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

All authors have conducted the analyses presented together and have written the manuscript together.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by the Leibniz-Instiut für Deutsche Sprache and the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz Association.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Emma Betz for sharing some of the data we have used for this study. We thank Axel Schmidt as well as Andrea Golato and Pentti Haddington, who provided the reviews, and Xiaoting Li on the part of the editors of this Research Topic for their valuable comments on a prior version of the text.

Footnotes

1. ^Actions produced with darf/kann ich? always inhabit a complete TCU (turn-constructional unit; Sacks et al., 1974), which can, but does not have to be a complete turn.

2. ^Extracts are transcribed according to GAT2 transcription conventions for German (Selting et al., 2011) and Mondada's conventions for multimodal transcription (see https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription). Note that we use -b for “body,” -g for “gaze,” -h for “hand” and -f for “face” in transcribing non-verbal conduct.

3. ^See Enfield (2009, p. 286) on “sequential” and “thematic” agency.

4. ^The corpus is accessible to scholars after registering at http://dgd.ids-mannheim.de.

5. ^In our data, we did not find any interactional and functional differences between the uses of darf ich? and kann ich?. Therefore, we do not treat them as distinct formats in this paper.

6. ^Here, “A” stands for the darf/kann ich?-speaker and “B” for the recipient.

7. ^We expect that to the extreme right of the continuum, there would be the cases of A producing an embodied action that intrudes into B's territory without requesting at all (e.g., when a driving instructor grasps the steering wheel, Deppermann, 2017, when the parent touches the child to achieve compliance to a directive, e.g., Cekaite, 2015; see also the contributions to Cekaite and Mondada, 2021). A's action then can be considered as an effect-oriented action that does not exhibit any observable concern with intersubjective permissibility. Consequently, A claims high deontic rights and agency, while B is not treated as a partner who has rights to guide the sequence. Future research will have to prove whether the analysis sketched here holds true.

References

Auer, P. (2014). Syntactic structures and their symbiotic guests: notes on analepsis from the perspective of online syntax. Pragmatics 24, 533–560. doi: 10.1075/prag.24.3.05aue

Auer, P. (2015). “The temporality of language in interaction: projection and latency,” in Temporality in Interaction, eds A. Deppermann, and S. Günthner (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 27–56. doi: 10.1075/slsi.27.01aue

Auer, P. (2020). “Genau! Der auto-reflexive Dialog als Motor der Entwicklung von Diskursmarkern,” in Verfestigungen in der Interaktion – Konstruktionen, sequenzielle Muster, kommunikative Gattungen, eds B. Weidner, K. König, L. Wegner, and W. Imo (Berlin: de Gruyter), 263–294. doi: 10.1515/9783110637502-011

Broth, M., and Mondada, L. (2013). Walking away: the embodied achievement of activity closings in mobile interaction. J. Pragmatics 47, 41–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2012.11.016

Brown, P., and Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness. Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511813085

Cekaite, A. (2015). The coordination of talk and touch in adults' directives to children: touch and social control. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 48, 152–175. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2015.1025501

Cekaite, A., and Mondada, L. (2021). Touch in Social Interaction. Touch, Language, and the Body. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003026631

De Stefani, E., and Mondada, L. (2021). “A resource for action transition: OKAY and its embodied and material habitat,” in OKAY Across Languages, eds E. Betz, A. Deppermann, L. Mondada, and M.-L. Sorjonen (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 311–336. doi: 10.1075/slsi.34.10des

Deppermann, A. (2014). “Multimodal participation in simultaneous joint projects: Interpersonal and intrapersonal coordination in paramedic emergency drill,” in Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond Multitasking, eds P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 247–282. doi: 10.1075/z.187.09dep

Deppermann, A. (2017). “When the instructor takes the steering wheel,” in Paper presented at the 7th European Advanced Workshop on Mobility and Social Interaction (MOBSIN7). Paris: Telecom Paristech.

Deppermann, A. (2020). Lean syntax: how argument structure is adapted to its interactive, material, and temporal ecology. Linguistische Berichte 263, 255–294.

Deppermann, A. (2021). “Imperative im Deutschen: Konstruktionen, Praktiken oder social action formats?,” in Verfestigungen in der Interaktion. Konstruktionen, Sequenzielle Muster, Kommunikative Gattungen, eds B. Weidner, K. König, W. Imo, and L. Wegner (Berlin: de Gruyter), 195–229. doi: 10.1515/9783110637502-009

Deppermann, A., Laurier, E., Mondada, L., Broth, M., Cromdal, J., De Stefani, E., et al. (2018). Overtaking as an interactional achievement: video analyses of participants' practices in traffic. Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 19, 1–131.

Deppermann, A., Mondada, L., and Pekarek Doehler, S. (2021). Early responses. An introduction. Discourse Processes, 15. doi: 10.1080/0163853X.2021.1877516

Deppermann, A., and Streeck, J. (2018). Time in Embodied Interaction. Synchronicity and Sequentiality of Multimodal Resources. Amsterdam: Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/pbns.293

Dowty, D. (1991). Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67, 547–619. doi: 10.1353/lan.1991.0021

Duranti, A. (2004). “Agency in language,” in A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology, ed A. Duranti (Malden, MA: Blackwell), 451–73. doi: 10.1111/b.9781405144308.2005.00023.x

Ekman, P. (1979). “About brows: emotional and conversational signals,” in Human Ethology: Claims and Limits of a New Discipline, eds M. Von Cranach, K. Foppa, W. Lepenies, and D. Ploog (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 169–202.

Enfield, N. J. (2009). The Anatomy of Meaning: Speech, Gesture, and Composite Utterances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511576737

Enfield, N. J. (2011). “Sources of asymmetry in human interaction: enchrony, status, knowledge and agency,” in The Morality of Knowledge in Conversation, eds T. Stivers, L. Moncada, and J. Steensig (New York. NY: Cambridge University Press), 285–312. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511921674.013

Enfield, N. J., and Kockelman, P. (2017). Distributed Agency. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190457204.001.0001

Enfield, N. J., Stivers, T., Brown, P., Englert, C., Harjunpää, K., Hayashi, M., et al. (2019). Polar questions. J. Linguistics 55, 277–304. doi: 10.1017/S0022226718000336

Fox, B. (2015). On the notion of pre-request. Discourse Stud. 17, 41–63. doi: 10.1177/1461445614557762

Fox, B., and Heinemann, T. (2016). Rethinking format: an examination of requests. Language Soc. 45, 499–531. doi: 10.1017/S0047404516000385

Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Goodwin, C. (1979). “The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation,” in Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology, ed G. Psathas (New York, NY: Irvington Publishers), 97–121.

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. J. Pragmatics 32, 1489–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., and Nevile, M., (eds.). (2014). Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond Multitasking. Amsterdam: Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/z.187

Heath, C., Luff, P., Sanchez-Svensson, M., and Nicholls, M. (2018). Exchanging implements: the micro-materialities of multidisciplinary work in the operating theatre. Sociol. Health Illness 40, 297–313. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12594

Helmer, H. (2016). Analepsen in der Interaktion. Semantische und sequenzielle Eigenschaften von Topik-Drop im gesprochenen Deutsch. Heidelberg: Winter.

Heritage, J., and Raymond, G. (2012). “Navigating epistemic landscapes: acquiescence, agency and resistance in responses to polar questions,” in Questions: Formal, Functional and Interactional Perspectives, ed J. P. de Ruiter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 179–192. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139045414.013

Hömke, P., Holler, J., and Levinson, S. C. (2018). Eye blinks are perceived as communicative signals in human face-to-face interaction. PLoS ONE 13:e0208030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208030

Jehoul, A., Brône, G., and Feyaerts, K. (2017). The shrug as marker of obviousness. Linguistics Vanguard 3, 1–9. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2016-0082

Kamunen, A., and Haddington, P. (2020). From monitoring to co-monitoring: projecting and prompting activity transitions at the workplace. Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 21, 82–122.

Keevallik, L. (2015). “Coordinating the temporalities of talk and dance,” in Temporality in Interaction, eds A. Deppermann, and S. Günthner (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 309–336. doi: 10.1075/slsi.27.10kee

Keevallik, L. (2018). What does embodied interaction tell us about grammar? Res. Language Soc. Interaction 51, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2018.1413887

Keisanen, T., and Rauniomaa, M. (2012). The organization of participation and contingency in prebeginnings of request sequences. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 45, 323–351. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2012.724985

Kendon, A. (1972). “Some relationships between body motion and speech,” in Studies in Dyadic Communication, eds A. Siegman, and B. Pope (New York, NY: Pergamon Press), 177–210. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-015867-9.50013-7

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511807572

Kendrick, K. H., and Drew, P. (2016). Recruitment: offers, requests, and the organization of assistance in interaction. Res. Language Soc. Interaction 49, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2016.1126436

Klein, W. (1993). “Ellipse,” in Syntax. Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung, eds J. Jacobs, A. Stechow, W. Sternefeld, and T. Vennemann (Berlin: de Gruyter), 763–799.

Kratzer, A. (2012). Modals and Conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199234684.003.0004

Levinson, S. C. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511813313

Mazeland, H. (2013). “Grammar in conversation,” in The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, eds J. Sidnell, and T. Stivers, (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell), 475–491. doi: 10.1002/9781118325001.ch23

Mondada, L. (2012). Talking and driving: multiactivity in the car. Semiotica 191, 223–256. doi: 10.1515/sem-2012-0062

Mondada, L. (2014a). “Pointing, talk and the bodies: reference and joint attention as embodied interactional achievements,” in From Gesture in Conversation to Visible Utterance in Action, eds M. Seyfeddinipur, and M. Gullberg (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 95–124. doi: 10.1075/z.188.06mon

Mondada, L. (2014b). “The temporal orders of multiactivity: operating and demonstrating in the surgical theatre,” in Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond Multitasking, eds P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 33–76. doi: 10.1075/z.187.02mon

Mondada, L. (2014c). Instructions in the operating room: how the surgeon directs their assistant's hands. Discourse Stud. 16, 131–161. doi: 10.1177/1461445613515325

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: challenges for transcribing multimodality. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 51, 85–106. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Raymond, C. W., Clift, R., and Heritage, J. (2021). Reference without anaphora. On agency through grammar. Linguistics. doi: 10.1515/ling-2021-0058. [Epub ahead of print].

Raymond, C. W., Robinson, J. D., Fox, B. A., Thompson, S. A., and Montiegel, K. (2020). Modulating action through minimization: syntax in the service of offering and requesting. Language Soc. 49, 1–39. doi: 10.1017/S004740452000069X

Raymond, G., and Lerner, G. (2014). “A body and its involvements: adjusting action for dual involvements,” in Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond Multitasking, eds P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 227–246.

Rossi, G. (2014). “When do people not use language to make requests?,” in Requesting in Social Interaction, eds P. Drew, and E. Couper-Kuhlen (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 303–334. doi: 10.1075/slsi.26.12ros

Rossi, G., and Stivers, T. (2020). Category-sensitive actions in interaction. Soc. Psychol. Q. 84, 49–74. doi: 10.1177/0190272520944595

Rossi, G., and Zinken, J. (2016). Grammar and social agency: the pragmatics of impersonal deontic statements. Language 92, e296–e325. doi: 10.1353/lan.2016.0083

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., and Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50, 696–735. doi: 10.1353/lan.1974.0010

Schegloff, E. A. (1984). “On some gestures' relation to talk,” in Structures of Social Action, eds J.M. Atkinson, and J. Heritage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 266–296. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511665868.018