- Multimodality, Interaction & Discourse (MIDI), Faculty of Arts, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

In linguistics, if-clauses have attracted the interest of scholars working on syntax, typology and pragmatics alike. This article examines if-clauses as a resource available to tour guides for reorienting the visitors’ visual attention towards an object of interest. The data stem from 11 video-recorded tours in Italian, French, German and Dutch (interpreted into Flemish Sign Language). In this setting, guides recurrently use if-clauses to organize a joint focus of attention, by soliciting the visitors to bodily and visually rearrange. These clauses occur in combination with verbs of vision (e.g., to look), or relating to movement in space (e.g., to turn around). Using conversation analysis and interactional linguistics, this study pursues three interrelated objectives: 1) it examines the grammatical relationship that speakers establish between the if-clause and the projected main clause; 2) it analyzes the embodied conduct of participants in the accomplishment of if/then-constructions; 3) it describes if-clauses as grammatical resources with a twofold projection potential: a vocal-grammatical projection enabling the guide (or the addressees) to achieve a grammatically adequate turn-continuation, and an embodied-action projection, which solicits visitors to accomplish a situationally relevant action, such as reorienting gaze towards an object of interest. These projections do not run independently from each other. The analysis shows how, while producing an if-clause, guides adjust their emerging talk—through pauses, expansions and restarts—to the visitors’ co-occurring spatial repositioning. These practices are described as micro-sequential adjustments that reflexively affect turn-construction and embodied compliance. In addressing the above phenomena and questions, this article highlights the fundamentally adaptive, situated and action-sensitive nature of grammar.

Introduction

From a syntactic perspective, an if-clause is commonly described as a subordinate clause, or protasis, which is canonically followed by a then-clause, the apodosis, with which it forms a conditional construction.1 Within functional linguistics, different labels have been used to account for the kinds of conditionality that seem to relate the protasis to the apodosis: Sweetser (1990) distinguished content conditionals (If Mary goes, John will go), from epistemic conditionals (If she’s divorced, (then) she’s been married), and from speech-act conditionals (If I may say so, that’s a crazy idea).2 Sweetser’s epistemic conditionals resonate with the way in which if-clauses are conceived of in logic (Frege, 1923; Gibbard, 1981; Krzyżanowska, 2015), where conditional reasoning is based on an antecedent (if) and a consequent (then). Finally, Lerner’s (1991) interactional approach described the if-clause as the first component of a compound turn-constructional unit (TCU; Sacks et al., 1974): upon uttering the if-component, the speaker projects the relevance of a second component, the then-component. While these approaches pursue very different analytical goals and methodological procedures, they all seem to purport an understanding of if-clauses as forming the first part of a bipartite construction.

In many languages, if-clauses are recognizable as such from the onset of their production, since they are formed with particular conjunctions in clause- and TCU-initial position, such as se (Italian), si (French), wenn (German), and als (Dutch).3 In these languages, such TCU-beginnings enable speakers to display the syntactic trajectory of their turn-in-progress early on. Because of this, if-clauses are a fundamental resource for the organization of turn-taking, as they allow recipients to foresee the possible end of a turn-in-progress, and possibly to collaboratively complete the bi-clausal structure (Günthner, 2020; and more generally Lerner, 1991 on “two-part formats”). The interactional import of if/then-constructions has been described for various languages (English: Ford, 1997; German: Auer, 2000; Günthner, 1999; Günthner, 2020; Italian: Lombardi Vallauri, 2010; Finnish: Nissi, 2016 among many others), but researchers have focused exclusively on the ways in which if-clauses are dealt with in talk, whereas little is known about how such constructions are embedded in the interactants’ embodied conduct (but see Lindström et al., 2019).

In addition to the canonical understanding of if-clauses as first components of a bipartite construction, several authors have discussed the occurrence of stand-alone if-clauses in different languages. For German, Buscha (1976) described the latter as isolierte Nebensätze ‘isolated subordinate quotes’ whereas Stirling (1999) spoke of isolated if-clauses for Australian English. Schwenter (2006) referred to independent si-clauses for Spanish, and Laury (2012) to independent jos-clauses for Finnish, whereas for Italian, Lombardi Vallauri (2010) spoke of free conditionals. In his typological approach, Evans (2007) introduced the notions of insubordinated clause and insubordinated conditionals for if-clauses that do not project a second component. These notions have since been adopted by many linguists (see Beijering et al., 2019).4

The pragmatic dimension of stand-alone if-clauses is systematically described in the literature on the topic. Evans (2007, p. 387) argued that they serve “interpersonal control,” i.e., speakers accomplish a request, order, wish, etc. by producing an isolated protasis. They do so, according to the literature, in a polite way, hence the description of the resource as a polite directive (Ford and Thompson, 1986; Lindström et al., 2016) or as an if-request (Evans, 2007; Lindström et al., 2019). These studies highlighted that speakers may produce and recipients may treat if-clauses as complete constructions, although they may syntactically appear as subordinate clauses. As Günthner (2020) has shown, prosody is an important feature that allows participants to differentiate between complete and projecting if-clauses. Complete if-clauses are generally produced with a terminal intonation (Stirling, 1999, p. 289), whereas if-clauses articulated with a continuing intonation project more talk—which may be more or less syntactically integrated, as the analyses below show.

If-clauses, be they treated as complete or projecting, pose an interesting problem of “action formation and ascription” (Levinson, 2013) for interactants and of “action description” for analysts. Indeed, speakers need to design their turn-in-progress in a way that addressees can hear it as making relevant some specific action, and addressees need to enable themselves to understand an if-clause as soliciting a specific action from them. This study reveals that both action formation and action ascription are crucially achieved by combining vocal and embodied resources.

The literature describes the action speakers accomplish with an if-clause by referring to a variety of labels (request, proposal, wish, suggestion, offer, etc.; see Buscha, 1976; Evans, 2007; Laury, 2012), which generally treat them as directives (but see Günthner, 2020 for independent if-clauses in German that convey warnings, threats, assessments or stance). This variety of labels is symptomatic for the difficulty analysts have in pinning down the pragmatic dimension of such if-clauses. For the sake of simplicity, the notion of solicitation will be used to refer to if-clauses by which speakers project that an (embodied) action is expected from the visitors. This use has been described extensively for stand-alone if-clauses, which are often seen as resulting from a grammaticalization process whereby uttering the main clause (the canonically present apodosis) is no longer necessary (Evans, 2007). At variance with this explanation, if-clauses produced by tour guides are analyzed here as a means to reorient the visitors’ attention, and this study shows that these are systematically followed by a then-clause, i.e., by an apodosis. Moreover, it takes into analytical consideration the temporal and situated dimensions of the production of talk. Hence, this paper examines if-clauses that establish both what Auer (2005) called a grammatical projection (or syntactic projection; Auer, 2009)—thereby preparing the grounds for a subsequent then-clause—and an action projection (Auer, 2005), which makes relevant a specific action to be carried out by the addressees, namely that they orient their embodied attention towards an object that is perceptually accessible in the immediate environment. This article uses a slightly adapted terminology, as it examines the vocal-grammatical projection that emerges in vocal languages (as opposed to, e.g., signed languages) and the embodied-action projection, whereby what is projected is an embodied action (as opposed to a vocally accomplished action, such as an “answer,” etc.).

By examining a specific setting of interaction, guided tours, this study highlights how the grammatical resources that languages provide emerge in time in a way that is sensitive to the situated activities at hand. Guided tours are indeed a perspicuous setting (Garfinkel and Wieder, 1992) for analyzing how a participant with specific deontic and epistemic rights and obligations, i.e., the guide, organizes group activities. Interactionally oriented researchers have identified guided tours as a setting of interaction in which deictic reference is recurrent (De Stefani, 2010), in which participants jointly organize their relevant activities (Stukenbrock and Birkner, 2010; Best, 2012). They have examined how participants accomplish those activities by adopting specific spatial configurations (Best and Hindmarsh, 2019) and how the guides’ expertise may be challenged by visitors (De Stefani and Mondada, 2014; De Stefani and Mondada, 2017). Moreover, researchers have focused on more (but not exclusively) language-related practices observable in guided tours, such as narratives (Burdelski, 2016), ostensive definitions of perceptually accessible referents (Traverso and Ravazzolo, 2016) and demonstrations thereof (Fukuda and Burdelski, 2019).

This line of research has also shown that guides are expected to organize the alternance between mobile and stationary phases of the visit, to select objects of interest, provide explanations, etc. Moments of stationary interaction are typically organized around objects of interest that are perceptually accessible and about which the guide provides information. Therefore, one practical problem for guides involves creating a joint focus of attention that enables visitors to (visually) access the object in question. Such joint attention does not presuppose a simultaneous access to the object, but can also occur “successively, i.e., when speakers withdraw their gaze from the object before addressees look at it.” (Stukenbrock, 2020, p. 4). This is particularly true for addressees who are members of large groups, and who in moments of collective reorientation risk mutually hindering visual access to the object of interest. The phenomenon investigated here, i.e., grammar as a resource for action organization, is tightly related to Stukenbrock’s (2018, 2020) studies on joint attention, since guides use if-clauses precisely as a further resource to orient the visitors to a common focus of attention. The main concern relates here, however, to the ways in which guides embed this specific linguistic resource in the situatedly emerging course of action.

As a complement to the existing literature, this article addresses the following research questions:

- Which formats of if/then-constructions are observable in the setting under scrutiny and across a variety of languages?

- What is the projection potential of if-clauses?

- To what extent is embodied conduct involved in making if-constructions perceivable as solicitations to establish a focus of joint attention?

- How do embodied conduct and turn-construction reflexively affect each other?

By answering these questions, this article extends the literature on guided tours as an interactionally organized social activity. It also proposes a detailed analysis of a specific grammatical format, if-clauses, as a resource with a twofold projection potential, i.e., a vocal-grammatical one and an embodied-actional one. The context-sensitive analysis of a grammatical construction—which considers embodiment, spatial configurations and temporality to be of paramount importance in the participants’ engagement to form and ascribe action (in Levinson’s 2013 sense)—sheds new light on if-constructions. In particular, it shows that a description in terms of conditionality insufficiently captures the use attested in guided tours and it describes the setting as a perspicuous environment for observing complete if/then-constructions (rather than stand-alone if-clauses) as emerging from the practical need to organize a joint focus of attention. These constructions result, as such, from micro-sequential adaptations between the guide’s talk and the visitors’ embodied responses.

Materials and Methods

This study is based on a 17 h corpus of video-recorded guided tours of cities and museums collected in various countries and languages, namely Italian (3 tours), French (3 tours), German (1 tour), Dutch with interpretation into Flemish Sign Language (1 tour).5 The size of the groups varied from 4 to over 20 participants, who were assisted by one or two guides. Twenty-three occurrences of if-clauses used by guides in their attempt to create a joint focus of attention were identified.6 These have been transcribed following standards established by Jefferson (2004) for talk and Mondada (2018a) for embodied actions.7 In the transcripts, the lines in the original language are translated into colloquial English (in italics). An additional interlinear gloss with the minimally necessary grammatical clarifications is provided for the target constructions. The analysis has been carried out with instruments offered by Conversation Analysis (Sacks et al., 1974; Sacks 1992) and Interactional Linguistics (Selting and Couper-Kuhlen, 2001; Couper-Kuhlen and Selting, 2018).

Results

The if-clauses guides use to reorganize the visitors’ focus of attention show some convergence across the languages analyzed, especially with regard to verb semantics and the subject of the clause. The verbs overwhelmingly relate to: 1) spatial positioning and movement (such as Italian girarsi or French se retourner ‘to turn around’); and to 2) visual perception (for instance, Italian guardare, French regarder, Dutch kijken or German (sich) anschauen ‘to look, observe’). In some languages, verbs are employed in which both dimensions are present, such as Italian affacciarsi, which can be glossed as ‘to position oneself with the face towards X and to look’. The grammatical subject is most frequently a second person plural (15 cases) or singular (1 case, in Dutch),8 but other subjects have been observed (e.g., 3rd person impersonal pronoun in German and French), for which language-specific preferences may account. If-clauses produced with these features are projective in two ways: 1) They are projective with respect to grammar, in that they prosodically index turn-continuation, thereby making expectable a subsequent main clause (Auer, 2005; Auer, 2009; Deppermann and Streeck, 2018); they are heard as a protasis that makes relevant an apodosis, or as a first component of a compound TCU that projects a second component (Lerner, 1991); they project thus a vocal-grammatical continuation; 2) They are also projective with respect to action, in that they make relevant an action to be carried out by the visitors; they are recognizable as first actions that make the accomplishment of a second action conditionally relevant (Goodwin, 2002; Schegloff, 2007), more precisely, an action that addressees have to carry out bodily. Thus they also project an embodied action.

The following sections illustrate the most significant findings emerging from the analysis of 23 occurrences of if/then-constructions observed in the organization of a joint focus of attention. The sections on If-Clauses Followed by (Non-)Integrated Main Clauses take grammatical features of the constructions as a starting point and examine their temporal and embodied contingencies. The section entitled Micro-Sequential Adjustments illustrates the micro-sequential dimension of turn-construction by showing how a guide’s turn-in-progress is sensitive and responsive to the addressees’ embodied conduct. Finally, and in a contrastive vein, the section on If-Clauses in Vocal and Signed Languages argues that while if-clauses are a powerful resource for reorienting the visitors’ attention in vocal languages, they are less successfully employed in signed languages. In all the excerpts below, a box with a single line highlights the protasis, whereas the apodosis is indicated with a box drawn with a double border line. On occasion, the boundaries of protasis and apodosis are not clearly identifiable since speakers may extend (e.g., with relative clauses), or repair (e.g., with restarts) either component. Therefore, the highlighting is intended to spotlight the target units of the turns-at-talk, not to provide a fine-grained grammatical analysis.

If-Clauses Followed by Integrated Main Clauses

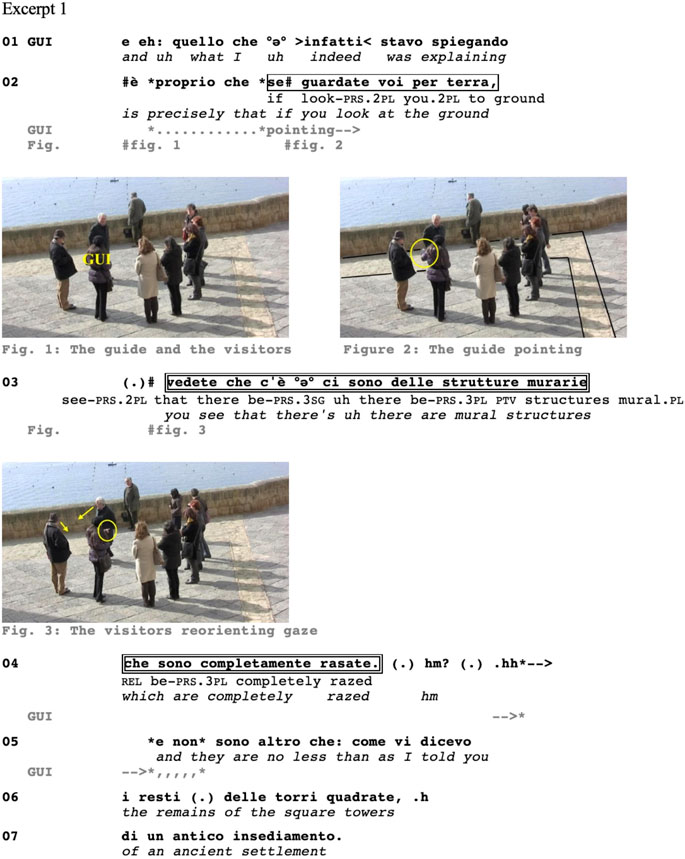

Excerpt 1 shows a fairly canonical case of an if-clause followed by a then-clause, as observed in guided tours. The group is visiting Castel dell’Ovo, a seaside castle and one of the oldest buildings located in the city of Naples, Italy. The participants are standing in a circle on the terrasse of the castle (Figure 1), embodying an F-formation (Kendon, 1990). The guide is providing explanations about the transformations that the terrace underwent over the centuries.

While in the data available it is not visible at what moment the guide reorients her gaze toward the environmental features that she is about to introduce in talk, the video excerpt shows that she starts performing a pointing gesture with her extended left index shortly before articulating the unit “se”/‘if’ (Figures 1, 2; l. 02). What becomes progressively recognizable as an if-clause (“se guardate voi per terra,”/‘if you look at the ground’; l. 02) is accompanied by the guide’s pointing hand, which follows the area in which the intended object is visible (highlighted in Figure 2). While the guide formulates the area in which the new referent will be located already at the end of the protasis (“per terra”/‘at the ground’; l. 02), the pointing gesture is instrumental for the visitors in identifying the new focus of attention, i.e., vestiges of razed walls, since it traces (Goodwin, 2003) the area in which the object can be found, thereby delimiting a domain of scrutiny (Goodwin, 2003; Stukenbrock, 2020). Note that (some) visitors are orienting their gaze towards the referent9 already before the guide starts articulating the apodosis (Figure 3). The guide then produces the second part of the if/then-construction (“vedete che c’è […]”/‘you see that there is […]’; ll. 03–04), after a micro-pause of about 0.2 s (l. 03), while her hand continues to trace the area of interest.

The analysis shows that the guide displays an embodied reorientation towards a perceptually accessible object already before starting to articulate the if-clause, thereby self-orienting (Stukenbrock, 2020: 5) in preparation of the upcoming reorganization of the collective focus of attention. In this case, the visitors (certainly some of them), orient their attention very early towards the area indicated by the guide, i.e., even before she starts articulating the apodosis. This is certainly facilitated by the fact that the achievement of a joint focus of attention requires only minimal reorientation—which may possibly be achieved just by eye-movements, at least for visitors who are already positioned in such a way to have an easy access to the domain of scrutiny delimited by the guide. The easy perceptional accessibility of those environmental features enables the guide to produce the if/then-construction in a smooth way, without major hitches or interruptions. Also, the solicited action (to “look”) is recognizable very early in the TCU, as the verb form “guardate”/‘you look’ occupies the subsequent position after the conjunction “se”/‘if’ (l. 02). Moreover, the then-clause appears to be perfectly integrated into the syntactic trajectory projected by the if-clause. While in many Germanic languages the level of syntactic integration of the then-clause can be identified on the basis of the position of the finite verb, in Italian, the position of the finite verb in the then-clause is not a useful criterion to measure syntactic integration. Rather, the smooth continuation of the syntactic trajectory, the semantic consonance of verbs in the if-clause (“guardate”/‘you look’; l. 02) and in the then-clause (“vedete”/‘you see’; l. 03), as well as the fact that the same subject occurs in both clauses, convey a sense of syntactic integration and causal relationship.

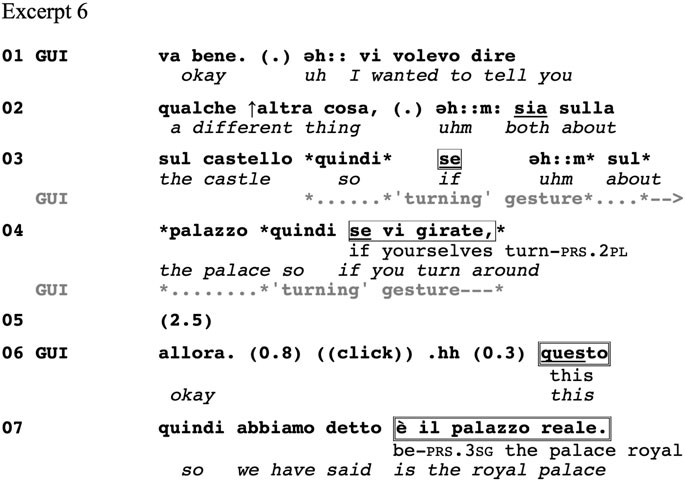

Excerpt 2 is taken from a guided visit of a manor in Brittany, France. The guide has positioned herself facing the visitors, who are slowly walking towards her while she remains silent. The guide then uses an if-clause to organize the visitors’ visual attention and movement in space (“si vous allez ↑voir dans l’fond”/‘if you go have a look at the back’; l. 01).

EXCERPT 2. http://clapi.icar.crns.fr, Manor guide 2, 50:16–50:24.

As in the previous case, the protasis is produced in concomitance with a pointing gesture (Figure 4). Notably, in this case the guide uses a gesture that Kendon (2004), (p. 140) described as open hand palm vertical, which Stukenbrock (2015, p. 153) called a ‘visual direction instruction’ (visuelle Richtungsanweisung). This is a different pointing gesture from the one observed in Excerpt 1, which was executed with an extended index and hence oriented toward identifying a referent in the immediate environment. While in both cases the gestures indicate a “path” to follow (McNeill, 2000; Chui, 2009; De Stefani and Deppermann, 2021), in Excerpt 1 the path represented the shape of the object of interest, whereas in Excerpt 2 it is the path that the visitors have to follow to gain visual access to the object of interest. In this case, too, the guide produces the apodosis immediately after the end of the if-clause (“vous allez avoir un ultime témoignage […]”/‘you will have a final testimony […]’; ll. 02–03). However, although the visitors seem to be visually oriented towards the area that the guide has just indicated (Figure 5), at no moment do they start moving towards the area where the ‘final testimony of Madame Astor’s modernism’ (ll. 02–03) will be visible. This is witnessed also by the guide, as shown by her overt solicitation to ‘go have a look’, which she produces subsequently (“j’vous laisse aller voir”/‘I let you go have a look’; l. 04) while executing again an open hand palm vertical-gesture (Figure 6). It is only at this point that the visitors walk further towards the next room of the manor.

This excerpt illustrates a case in which visitors do not hear the protasis or the apodosis as an invitation to take action immediately. Indeed, the guide needs to produce additional language material to successfully reorient their attention (l. 04). Hence, the analysis of this excerpt shows one practical problem of guides, consisting in making sure that the visitors hear an if-clause as conveying an instruction to take action hic et nunc. That the visitors fail to do so in this excerpt may be related to (at least) two aspects. Contrary to what was observed in Excerpt 1, here the reorientation required from the visitors is substantial—they have to walk to the end of the corridor in order to discover the object of interest. Moreover, whereas in Excerpt 1 the guide invited reorientation to a visible and nameable referent that was identifiable in the immediate environment, in Excerpt 2 she does not mention a specific referent, but rather provides a conceptual description of what can be seen (‘Madam Astor’s modernism’; l. 03). There may be, of course, a pedagogical rationale behind this choice: the visitors will be able to discover for themselves what they deem to be a sign of ‘modernism’—and in this case they will indeed successfully do so, as they are going to discover that the manor, dating back to 1860, was equipped with a fully functioning automatic toilet (not transcribed).

Just like in Excerpt 1, the protasis and the apodosis show high syntactic integration. This is evidenced by the fluid articulation of the two clauses, by their semantic relatedness displaying a causal relationship, and by the recurrence of the same subject (“si vous allez ↑voir […] vous allez avoir […]”/‘if you go have a look […] you will have […]’; ll. 01–02).

The excerpts presented up to this point have provided first illustrations of the grammatical and action-related projection potentials of if-clauses in guided tours. These were embedded in embodied conduct (repositioning, gaze orientation, pointing) that the guide accomplished before initiating the if-clause by which she introduced a new object of interest. The guide’s protasis was followed immediately (Excerpt 2) or after a very short pause (Excerpt 1) by the apodosis. At times, however, guides allow more notable pauses to occur after the protasis or visitors may foresee early on the projected content of the apodosis. The reasons for this are laid out in the following sections.

If-Clauses Followed by a Pause

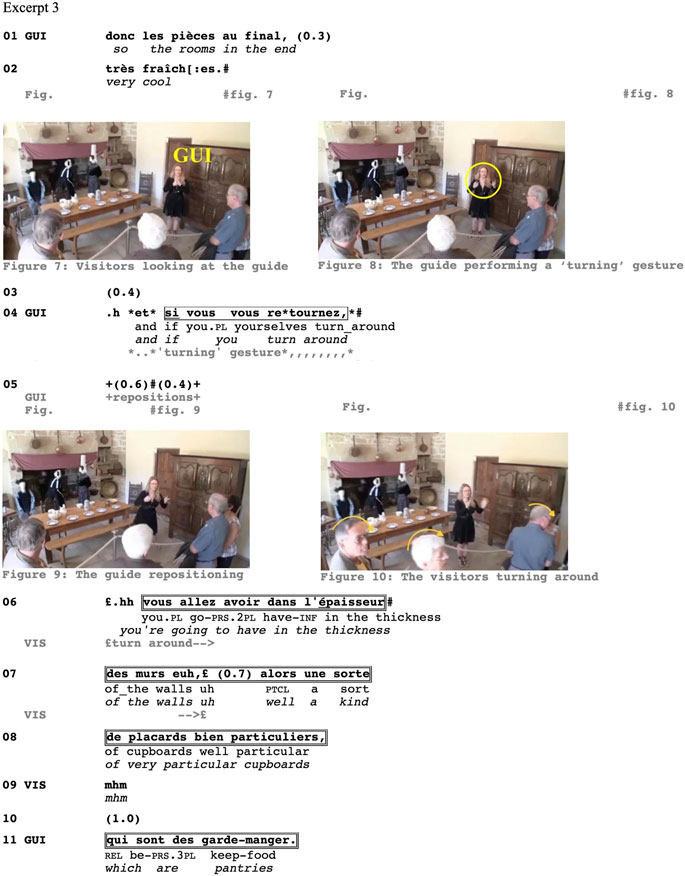

Excerpt 3 is taken from a tour through the same Breton manor as seen in Excerpt 2, with a different guide and other tourists. The group is standing in the kitchen of the manor and the visitors are facing the guide (Figure 7). At the beginning of the excerpt, the guide is articulating the upshot of her previous explanations (“donc”/‘so’; l. 01), observing that the rooms the group is visiting were ‘very cool’ (l. 02). At this point, the guide’s turn reaches a point of grammatical, pragmatic and prosodic completeness.

EXCERPT 3. http://clapi.icar.crns.fr, Manor guide 1, 07:08–07:20.

At l. 04, the guide extends her talk with a TCU prefaced by “et”/‘and,’ which is followed by an if-clause (“si vous retournez,”/‘if you turn around’). While uttering that component, she lifts both hands and performs a circular gesture, thereby providing an iconic representation of a “turning” movement (Figure 8). She subsequently allows a pause to occur (l. 05), during which she repositions her body, which enables her to adopt a position facing the object that she is going to introduce (Figure 9). It is only when the guide starts articulating the apodosis (“vous allez avoir […]”/‘you’re going to have […]’; l. 06) that the visitors visibly reorient themselves, by turning their heads, and then their bodies, in the direction embodied by the guide (Figure 10).

The excerpt shows the embodied work the guide performs in order to make sure that visitors hear the if-clause she is uttering as a solicitation to turn around. She performs a “turning” gesture (Figure 8) while articulating the protasis (l. 04), repositions herself, and allows a pause to occur at the end of the if-clause (l. 05). This pause is instrumental in conveying the pragmatic import of the protasis, namely that visitors should hear it as prompting them to take some action. It is also conducive to the visitors’ understanding that they should accomplish the projected action hic et nunc. In other words, in allowing a pause to occur, the guide gives the visitors time to apprehend her words as a solicitation to turn around, which they have to comply with without any delay. They indeed do so at l. 06, thereby enabling the guide to talk about the newly introduced referent (“placards bien particuliers,”/‘very particular cupboards’; l. 08), while the visitors are orienting their visual attention to the domain of scrutiny embodied by the guide. The duration of the pause is reflexively tied to the visitors’ embodied conduct. The guide can be seen to carefully monitor the visitors’ reorientation and to articulate the apodosis only once they have visual access to the object she is going to talk about. Moreover, this example shows that in vocal languages and with hearing participants, once the domain of scrutiny has been identified, visitors can withdraw their bodily orientation from the guide without encountering problems of understanding.

All the cases analyzed so far showed a protasis followed by a syntactically integrated apodosis, both clauses being produced by the same speaker, i.e., the guide. A relationship of causality between protasis and apodosis was observable in all the cases (of the kind: if you look at X/turn around (protasis), you’ll see/have (aposodis)). This is compatible with Sweetser’s (1990) notion of content conditional and confirms the idea of grammatical projection, i.e., that speakers articulating a protasis establish a projection that is syntactically fulfilled by the apodosis. With respect to action projection, the analyses have shown how guides ensure that if-clauses are heard as soliciting an embodied-actional response from the visitors, i.e., the reorientation towards a joint focus of attention. The next section discusses a case in which the visitors collectively display their understanding of both the grammatical and actional projection the guide establishes by articulating an if-clause, thereby documenting the participants’ locally and endogenously emerging analysis of grammar as it unfolds.

An Endogenous Analysis of If-Clauses: Co-Constructions

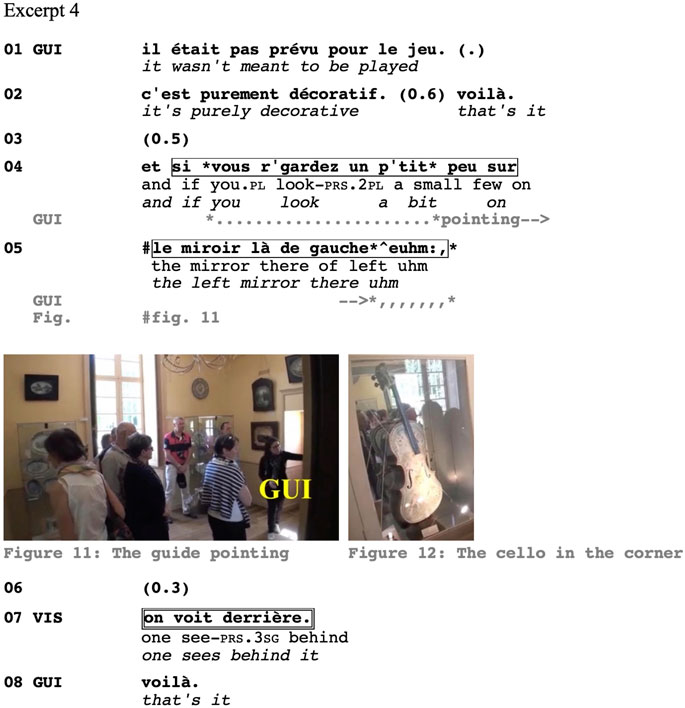

The excerpts discussed so far have shown if/then-constructions entirely produced by the guide. This section presents a case in which the guide articulates the protasis, but the apodosis is uttered collectively by the visitors. It shows the compelling strength of if-clauses in projecting a grammatically fitted continuation. Excerpt 4 is taken once more from a guided tour through the Breton manor, but the composition of the group is again different. The guide is providing explanations about a richly adorned cello that served ‘purely decorative’ (l. 02) purposes, while the visitors are looking in the direction of the cello. It is exposed in a glass display in a corner of the room (Figure 12).

EXCERPT 4. http://clapi.icar.crns.fr, Manor guide 3, 45:48–46:00.

The visitors have been oriented towards the cello already before the beginning of this excerpt. The object of interest is thus already established and perceptually available. At l. 02 the guide reaches a moment of syntactic, prosodic and pragmatic completion, and the guide’s “voilà”/‘that’s it’ (l. 02) makes a sequential closing expectable (Mondada, 2018b). At lines 04–05, however, the guide articulates an “et”-prefaced if-clause (“et si vous r’gardez un p’tit peu […]”/‘and if you look a bit […]’), thereby soliciting the visitors to orient their gaze towards the ‘left mirror’ (l. 05). Notably, she performs a pointing gesture that starts only after the initiation of the if-clause (l. 04), rather than before, as in the previously discussed Excerpts 1, 2. This difference may not be anecdotal. Indeed, whereas in the previous excerpts the guides were orienting the visitors’ attention to a so-far unmentioned object, in this case the object of interest (the cello) has already been identified and named. Moreover, the visitors are already looking at the cello (Figure 11), and are just solicited to fine-tune their gaze. The reorientation hence requires only a minimal adjustment of the gaze, which they accomplish immediately. Indeed, at l. 07 the visitors chorally10 produce the second part of the if/then-construction (“on voit derrière.”/‘one sees behind (it)’), thereby displaying their understanding of the guide’s grammatical turn-construction under way, and completing it. They modify the grammatical subject from the 2nd person “vous” (l. 04) to the subject pronoun “on”—which is used in French as a 3rd person singular (impersonal) or as a 1st person plural—thereby adjusting the construction to their perspective as a speaking party. At the same time, the visitors exhibit not only that they have already accomplished the gaze reorientation—i.e., that they have heard the if-clause as a solicitation to accomplish a specific action—but also that they have correctly identified the reason why the guide has just solicited an adjustment of their gaze orientation. This is confirmed by the guide’s “voilà”/‘that’s it’ at l. 08.

Günthner (2020, p. 199) has described jointly produced if/then-constructions as collaborative achievements in which second speakers “align with first speaker’s initiated syntactic project,” thereby illustrating the emerging dimension of grammatical turn-formatting, while at the same time demonstrating that participants resort to their own grammatical knowledge when co-constructing turns-at-talk. While the analysis of Excerpt 4 confirms Günthner’s point, the if/then-construction resulting from collaborative talk shows a minor, but significative difference with respect to the if/then-constructions described in Excerpts 1–3. Indeed, the change of the grammatical subject (“vous” in the protasis, “on” in the apodosis)—which is expectable as the apodosis describes an experience that the visitors are making at the time of utterance—is sensitive to the participants’ speakership status, as illustrated already by Jespersen (1924) notion of shifters,11 and testifies to the situated nature of language use. In contrast with the excerpts discussed so far, the following section discusses cases in which the then-clause is not fully integrated from a syntactic point of view.

If-Clauses Followed by Non-Integrated Main Clauses

The if-clauses examined in this study are systematically produced with a continuing intonation. Therefore, they are not stand-alone structures but project more talk, which may be more or less integrated. In German, the level of grammatical integration of then-clauses can be measured on the basis of the position of the finite verb (Günthner 2020, pp. 189–197). A then-clause showing the finite verb in second position (rather than in first position) is generally treated as non-integrated. This is exemplified by Excerpt 5, which has been recorded in the Natural History Museum of Berlin, Germany. The group is standing next to a skeleton of a brachiosaurus—which has a very long neck as a distinctive feature—and the guide is providing explanations. A little boy has just said that he believes that the brachiosaurus was able to lower his neck to ground level (not transcribed), and the guide now aligns with this idea (ll. 01–02).

At l. 03 the guide tilts his head back and gazes in the direction of the referent he is about to introduce. Clearly, he delineates what Stukenbrock (2020, p. 5) has called a domain of pointing, i.e., he embodies a reorientation that subsequently enables him to perform a pointing gesture directed to the intended object. He reorients his gaze while saying “es ist so,”/‘it’s like this,’ an idiomatic expression comparable to English here’s the thing, which projects more talk to come (see Auer, 2006). What follows is the if-clause “wenn wir uns den hals anschaun,”/‘if we look at the neck’ (l. 04), which the guide produces in concomitance with a pointing gesture towards the referent located above his head (Figure 13). At this point, most of the visitors’ heads display a level orientation, with the exception of one woman who is already looking in the direction indicated by the guide. This changes shortly after, when the guide continues to talk. While he produces the words “da sind so lange,”/‘there are like long’ (l. 05), the visitors collectively orient their gaze towards the area in which the guide is looking (Figure 14). It is only after a short pause (l. 05) that the guide produces the lexical item “stangen”/‘bars,’ with which he identifies the referent to which he is drawing the visitors’ attention.

While from a grammatical perspective the protasis is produced as a canonical if-clause (“wenn wir uns den hals anschaun”/‘if we look at the neck’; l. 04), the format of what can be identified as the apodosis (“da sind so lange, (0.6) stangen dran”/‘there are like long bars attached’; ll. 05–06) has been described as a non-integrated main clause (Günthner, 1999; Günthner, 2020).12 Not only is the then-clause constructed with the finite verb in second position, it is also hosting a different grammatical subject. It starts with the existential construction “da sind”/‘there are’ (l. 05), whereas the protasis mentioned the inclusive subject “wir”/‘we’ (l. 04). Existential constructions—but also deictic/demonstrative constructions as ‘this is,’ etc.—are observable when perceptional accessibility to the focus of joint attention is (about to be) established.

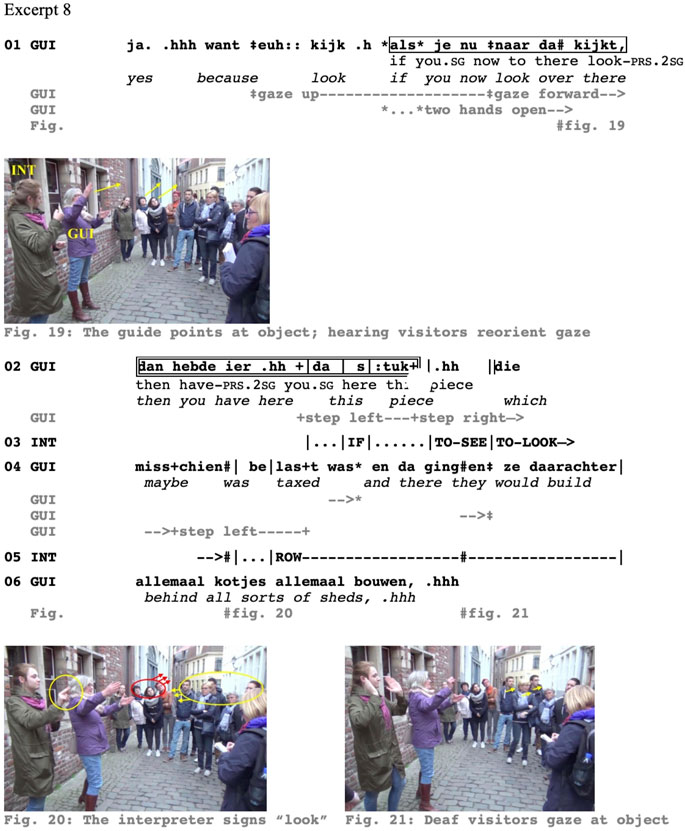

While in German syntactic (non-)integration can be measured on the basis of the position of the finite verb, this is not possible for other languages, such as Italian, where other criteria have to be sought. The following excerpt provides a case in point. Excerpt 6 is taken from a guided tour through Naples, organized for a school class. The group is standing in a large square (Piazza del Plebiscito) as the excerpt starts.13 The guide is facing the Royal Palace, whereas the schoolchildren are mostly oriented towards the guide.

At ll. 01–04 the guide announces that she ‘wanted’ to provide additional information to the visitors about the ‘castle’ (l. 03). She initiates an if-clause while at the same time performing a “turning” gesture with her right hand (l. 03). However, she abandons the projected turn-construction and accomplishes a self-correction that replaces the lexical unit “castello”/‘castle’ (l. 03) with “palazzo”/‘palace’ (l. 04). She then resumes the abandoned construction and articulates a grammatically complete if-clause (“se vi girate,”/‘if you turn around’; l. 04), while redoing the “turning” gesture. She then allows a 2.5-s pause to occur (l. 05), which gives the visitors the time to comply with the solicitation for action and to turn around so that they can see the ‘palace’ that the guide has just mentioned. Once the collective reorientation has been achieved, the guide continues her talk. She starts her next TCU with “allora.” (l. 06), an item that is used in a variety of ways in present-day Italian. One possible use is linked to if/then-constructions (se/allora in Italian; see Mazzoleni, 2001, pp. 781–784), as it is the item that may initiate the then-component. However, in this case the guide articulates it with a falling intonation, which makes it hearable as a “discourse marker” that is recurrently used in displaying transition to a new activity (see Bosco and Bazzanella, 2005). A further pause occurs, then the guide produces a click and after an inbreath and a further pause (l. 06) she starts producing what will progressively become recognizable as a main clause: “questo quindi abbiamo detto è il palazzo reale.”/‘this so we have said is the royal palace’ (ll. 06–07). While the protasis was articulated with a continuing intonation, which displayed incompleteness and projected more talk to come, what the guide produces as the second component of her construction is recognizable as a grammatically non-integrated continuation. Indeed, the turn-continuation is delayed by grammatically unattached material (“allora”/‘okay’) as well as by pauses and vocalizations (l. 06).

In contrast to Excerpts 1–4, in Excerpts 5–6 the protasis and the apodosis are not describable as forming a content conditional (Sweetser, 1990), which for Excerpt 6 would have implied an understanding of the construction as ‘if you turn around, then this is the Royal Palace.’ In other words, no relationship of causality is overtly established between the protasis and the apodosis. One could argue that ellipsis has occurred (‘if you turn around, then you can see that this is the Royal Palace’), an argument that is frequently put forward in the literature on independent if-clauses (Evans, 2007). However, independently from the cognitive underpinnings of this use, from an interactional perspective it is clear that none of the participants orient toward a putative “absence” of language material at this point (see also Lindström et al., 2019 for a critical assessment of the ellipsis model). While the protasis the guide produces in Excerpt 6 appears to come close to the insubordinated if-requests described by Evans (2007), one fundamental difference with respect to Evans’ examples relates to prosody. Indeed, in Excerpt 6 (as in all the other excerpts discussed in this article) the speakers project—also through prosodic means—that their turn is incomplete, that more talk is expectable. The extent to which subsequent talk is grammatically more or less fitted to the preceding if-clause is a matter of situated adaptation to the interactional contingencies. For instance, apodoses starting with constructions such as ‘there are,’ ‘this is’ may occur when perceptual accessibility to the referent in question is (about to be) established. Also, guides can be seen to actively monitor the visitors’ embodied behavior, and to adapt their turn-in-progress to the embodied responses they witness in the visitors’ conduct. The following excerpt provides an exemplary illustration of this.

Micro-sequential Adjustments

The analyses provided so far have already shown the extent to which the grammatical construction of turns-at-talk is reflexively structured by concomitant embodied behavior. This is visible even more clearly in Excerpt 7, taken from the same tour through Castel dell’Ovo, Naples, seen in Excerpt 1. At the beginning of the excerpt, the guide is engaged in an explanation about the different transformations that the castle underwent throughout the centuries (ll. 01–04), while all the visitors orient their attention towards the guide who is standing next to an opening in the ground (Figure 15).

While the guide is still engaged in providing explanations, she repositions her body and moves closer towards an opening in the ground that is enclosed by a guard rail (l. 04). This change of position, which the visitors can witness, foreshadows an activity that departs from the activity of providing explanations, in which the guide was engaged up to this point. Indeed, at l. 05 she starts gazing towards the area surrounded by the guard rail (Figure 16), while at the same time producing an if-clause “infatti .h se voi vi affacciate,” (l. 05), formed with the reflexive verb affacciarsi, for which no English equivalent exists, but which can be glossed as ‘to position oneself in a way to get visual access to something (by facing it).’14 The if-clause, which is articulated with a continuative prosody, is potentially complete at this point. However, the guide extends it with the deictic expressions “qui:”/‘here’ and “al di sotto”/‘below’ (l. 06). These extensions are not just casual phenomena of talk. Rather, by extending the if-clause in this way, the guide orients to the fact that the visitors need some time in order to reposition themselves and gain visual access to the referent to which she wishes to draw their attention. That reorientation is visible, for instance, in the modified posture that the three women on the left of Figures 16, 17 adopt by lowering their torso and orienting their head toward the area the guide indicates. That the guide is monitoring the visitors’ conduct is even more visible in her subsequent talk. Indeed, at l. 07 she produces what can be heard as the beginning of the projected main clause: “troverete,”/‘you will find.’ The verb, which occurs in the future tense, is produced while some visitors are visibly orienting towards the area the guide has indicated (e.g., the three women mentioned earlier), whereas others do not seem to have gained visual access to that area. This is particularly true for a white-haired man (WHI) who starts moving toward the guard rail at this moment, while the guide is visually monitoring him (Figure 17). Clearly, the guide can witness that WHI is not yet seeing the object she is going to talk about and that he is currently repositioning himself. Consequently, she adapts her turn-in-progress: she allows a 2-s pause to occur (l. 07) and then produces a softly spoken “non so se si vede”/‘I don’t know if you (can) see it’ (l. 07). This extension is sensitive to WHI’s embodied conduct. Indeed, as soon as WHI reaches the guard rail (Figure 18), the guide utters a new version of the apodosis, now formatted as “ci sono delle colonne.”/‘there are columns’ (l. 08). Note that she now uses an existential construction (“ci sono”/‘there are’) in the present tense. This way of formatting her turn-in-progress, in particular the transition from future to present tense, shows that she takes into account the current disposition of the visitors’ bodies and gaze when constructing her talk. So, while by substituting “troverete”/‘you will find’ (l. 07) with “ci sono”/‘there are’ (l. 08) the guide shifts from an integrated to a non-integrated format, the latter is sensitive to the visitors’ embodied and responsive conduct that the guide is witnessing, and appears hence to be the more adequate format, for all practical purposes. Once the referent has been introduced by the guide, and seen by the visitors, the guide resumes the previous activity, i.e., she provides explanations. In particular, she explains that the columns are actually the remains of a sumptuous villa that belonged to the Roman politician and commander Lucullus (ll. 11–13).

The analysis of this example has highlighted the reflexive relationship observable between the stepwise unfolding of the participants’ turns-at-talk and their mutually witnessable embodied conduct. The guide adapts her turn-construction to the witnessable and progressively achieved establishment of a joint focus of attention that she has solicited from the visitors. The pauses, expansions and self-repairs (including grammatical choices, e.g., of tense), exhibit micro-sequential adaptations of her talk to the visitors’ embodied conduct. Moreover, they show that observable compliance with the solicitation to reorient oneself is treated as necessary in order to fulfill the grammatical projection established by the protasis.

If-Clauses in Vocal and Signed Languages

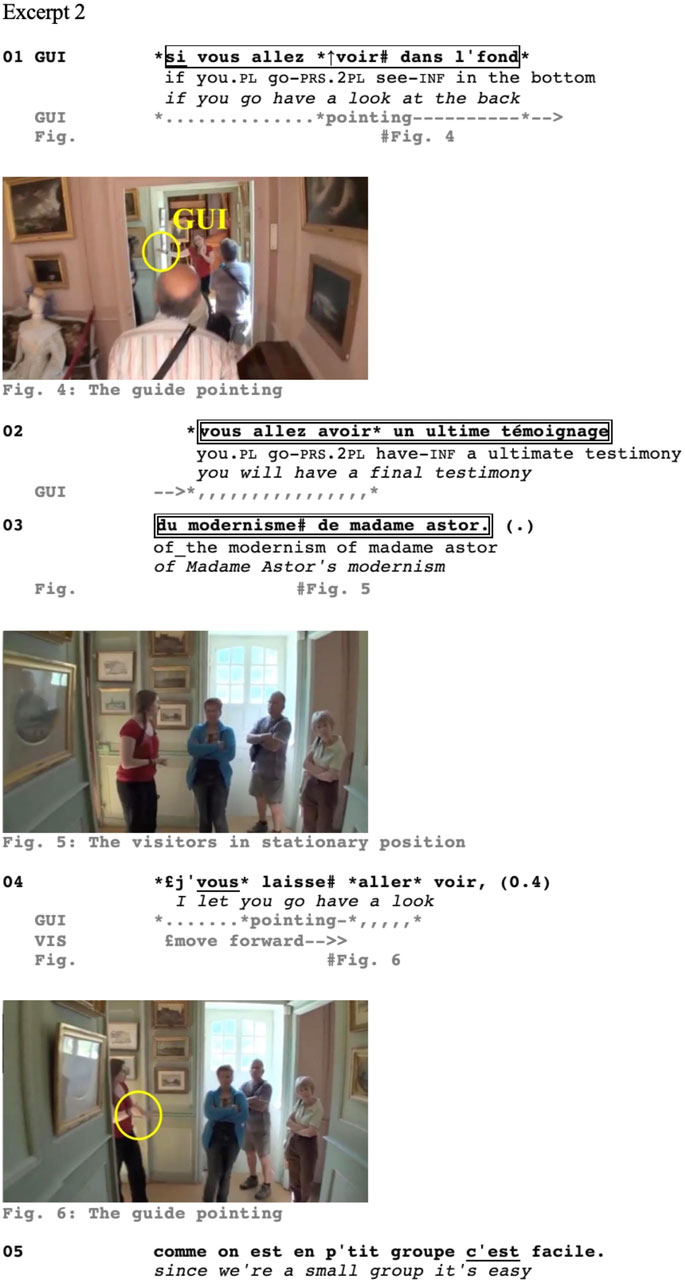

The analyses presented in the previous sections have shown that if/then-constructions may be useful in many vocal languages for organizing a joint focus of attention. They may be problematic, however, in vocal languages in which the if-component is not placed in clause-initial position (e.g., Japanese),15 or in languages that do not primarily rely on vocal resources, for instance signed languages. The last excerpt of this article documents, contrastively, a practical problem of an action-soliciting vocal if-clause interpreted into a signed language. It is taken from a guided tour through the city of Ghent, Belgium. The group is composed of people with diverse hearing status, ranging from fully hearing to deaf. A guide provides explanations in Dutch, while an interpreter renders her words in Flemish Sign Language, which is the official signed language of the deaf community in Flanders. At the beginning of Excerpt 8, the guide is explaining how working people used to live in the buildings visible in the street in which the group is currently standing. Since in earlier times people had to pay taxes on the facade of buildings, owners would extend the buildings with annexes set up in a row behind the facade. By doing so, owners were able to expand the buildings without paying more taxes, while at the same creating more space to rent.

At l. 01, the guide bodily reorients herself—by gazing upwards, and by extending her two open hands in the direction of the area before her (Figure 19). Shortly after, she produces the if-clause “als je nu naar da kijkt”/‘if you now look over there’ (l. 01):

Two visitors can be seen to reorient their gaze in the direction embodied and vocally indicated by the guide as soon as the latter produces the protasis (Figure 19). Clearly, by responding in this way, the visitors in question embody their being visitors who have auditive access to the guide’s words and who treat the protasis as soliciting them to reorient their gaze towards a new focus of attention, in accordance with the previously analyzed cases. Immediately after, the guide articulates the apodosis, in which she names the new object of attention (“dan hebde ier .hh da s:tuk”/‘then you have here this piece’; l. 02). The apodosis is syntactically integrated, with the finite verb “hebde” (a regional form of Dutch heb je, literally ‘have you’) in first position. Up to this point the example hence provides a further illustration of the phenomena discussed in If-Clauses Followed by Integrated Main Clauses.

The interpreter’s rendering of the guide’s words occurs, necessarily, with some delay. It is only at line 03 (while the guide is already producing the apodosis) that the interpreter starts rendering the guide’s protasis. She does so by selecting the same syntactic structure, i.e., by signing “IF” and shortly after “TO-LOOK” (l. 03). Note that the sign for “TO-LOOK” is executed with a deictic component in that the interpreter directs her V-shaped hand (extended index and middle finger) toward the area that needs to be “looked at.” Figure 20 shows that while the interpreter is producing this sign, the visitors visible on the right side of the image are visually oriented to her signing. Shortly after, three of them reorient their gaze towards the area indicated by the interpreter (Figure 21). While this is evidence that if-clauses may also be heard as soliciting reorientation in Flemish Sign Language, it also shows the pitfalls of this practice in a signed language. Indeed, by withdrawing their gaze from the interpreter at this moment, the deaf visitors risk missing her subsequent signing, thereby possibly failing to perceive the reason why they were solicited to reorient their attention, which may lead to difficulties in identifying the object of interest. Since signed languages crucially rely on embodiment and vision, rather than on voice and audition, soliciting recipients to look away from the interpreter and only later explaining what they see is indeed not a successful way of organizing joint attention among users of those languages.

Discussion

The analytical part of this article has brought to the fore the practical utility of if-clauses for tour guides as they carry out their professional tasks. The analysis focused on languages in which such clauses are recognizable from the onset of their production and was limited to if-clauses offered by guides and heard by visitors as solicitations to reorient towards a joint focus of attention. In all the 23 occurrences identified in the data, the if-clause (or protasis) was followed by a second component. Detailed analyses were provided for eight occurrences. The degree of grammatical integration of the second component (or apodosis) varied from fully integrated (Excerpts 1–3, 8) to non-integrated (Excerpts 5–6). Whereas fully integrated apodoses result in if/then-constructions that are compatible with Sweetser’s (1990) description of content conditionals, the same does not hold true for the non-integrated occurrences observed. The progressively unfolding format of the if-clause and the retrospectively observable turn-constructional features of the if/then-pattern have proven to be sensitive to embodied conduct, both of the speaker and the addressees. Guides systematically bodily display reorientation before or while articulating if-clauses, thereby exhibiting that they are in the process of establishing a domain of pointing (Stukenbrock, 2020, p. 5). Such bodily reorientation occurring in concomitance with an if-clause is likely to be perceived, by visitors, as progressively implementing a solicitation to establish a joint focus of attention towards a new object of interest. Typically, pointing gestures with the extended index or open hand(s) (Excerpts 1, 2, 4, 5, 8) and “turning” gestures (Excerpts 3, 6) were observed before or during the articulation of if-clauses. While from a formal point of view these would be categorized as different gesture types (with possibly different functions), the examination of their use in the specific ecology of guided tours shows that guides use them, in association with if-clauses, in similar ways, namely to reorient the visitors’ attention—either by establishing deictic reference to the object of interest (pointing), or by iconically representing the participants’ expected bodily reorientation (“turning” gesture). The conjoint deployment of embodied (reorientation) and vocal (if-clause) resources addresses what Schegloff (2007, p. xiv) called the action formation problem, i.e., the guide’s practical problem of making their action recognizable as a solicitation to establish a joint focus of attention. Clearly, the if-clause format is available to guides as a grammatical resource for soliciting reorientation toward what becomes progressively recognizable as an object of interest. However, soliciting reorientation is an accountable action. This is why, in this setting and in the data examined for this article, action-projecting if-clauses are systematically followed by main clauses, which allow the guide to account for her action. While the protasis allows guides to open up the domain of scrutiny that visitors are expected to orient to, it is in the apodosis that they reveal the specific object that becomes visible to the visitors’ eyes and on which they now provide information. Guided tours are thus a setting in which action-projecting if-clauses systemically establish grammatical projection. Ellipsis of the main clause—the mechanism from which Evans (2007) derives the occurrence of insubordinated if-clauses—is not expectable in this specific setting because guides need to account for the solicited reorientation.

The visitors face the problem of ascribing (Levinson, 2013) an action to the guide’s vocal and embodied conduct. It is through their silent, bodily reorientation and repositioning that they exhibit their understanding of the guide’s action as a solicitation to establish joint attention to a visually accessible object in the environment. Visitors may reorient themselves early, while the protasis is still in progress (Excerpt 1), especially in cases in which their reorientation requires only a minimal adjustment (e.g., of gaze orientation). It is in these contextual environments that co-construction of the if/then-format (Excerpt 4) is more likely, precisely because visitors are in a position to identify early on the intended object of interest and to display that identification by producing the apodosis. Visitors can also be seen to reorient once the protasis is recognizably achieved (Excerpt 5), while guides can allow a pause to occur after the protasis (Excerpts 3, 6) so as to give the visitors the time to reorient themselves before articulating the apodosis, by which they describe and name the intended object of interest. On occasion, however, visitors fail to respond in adequate ways, and guides may choose to articulate a more overt solicitation-format (Excerpt 2). This testifies to the practice as soliciting a reorientation that visitors need to accomplish hic et nunc. However, because an if-clause may not be heard as soliciting immediate action, it is not describable as a straightforward request. Rather, the guide uses it as a subtle resource to possibly mobilize embodied action, as an attempt of “weak manipulation” (Declerck and Reed, 2001, p. 386) of the visitors’ conduct. The visitors’ reorientation is not only sensitive to the recognizability of the protasis as a soliciting action, but also to the sensorial accessibility of the referent. The visitors’ embodied response is attentively monitored by guides while they articulate what eventually materializes as an if/then-construction. Their doing so is further evidence of the embodied-actional projection guides establish by articulating such if-clauses. As guides monitor the visitors’ embodied responses, they can be seen to adjust their unfolding turn, in particular, to the visitors’ possibly commencing and unfolding bodily reorientation (Goodwin, 1979, Goodwin C., 1980). This may lead to pauses, hesitations, incrementation, restarts, and other repair phenomena, thereby revealing the micro-sequential dimension of turn construction (Goodwin M. H., 1980; De Stefani, 2021; Deppermann and Schmidt, 2021), and affecting the syntax of the if/then-construction: what started as a grammatically integrated apodosis, may end up as a non-integrated completion of the if-clause (Excerpt 7). Also, the selection of the subject, verb tense, etc. that guides use for the apodosis is crucially related to the visitors’ embodied conduct: presentative and demonstrative constructions (‘there are,’ ‘this is,’ etc.) tend to be selected when visitors have already gained access to the intended object of interest (Excerpts 5–7). The reflexive constitution of turns-at-talk and embodied action is linguistically visible in how the guide’s if/then-format unfolds moment by moment, in the emergence of a grammatical construction that is continuously adapted to the contingencies at hand, and in the coordinated accomplishment of collective, embodied action.

Clearly, if-clauses are a powerful resource available to guides for organizing a joint focus of attention—in languages in which the protasis is recognizable as such at clause-initial position, such as the ones analyzed in this article. While this also holds true for Flemish Sign Language (Excerpt 8), the practical utility of if/then-constructions in signed languages for creating joint attention in the setting of guided tours is questionable.

Conclusion

In the setting examined in this article, if-clauses set off both a vocal-grammatical projection, by foreshadowing a then-clause, and an embodied-actional projection, by soliciting visitors to bodily reorient themselves. If-clauses are then one resource available to guides for solving a recurrent interactional problem, together with specific embodied conduct (repositioning, pointing, gazing). This practice is compatible with Mondada’s (2012) notion of complex multimodal gestalt. While vocal and embodied conduct are concomitant, and while their temporal unfolding is not isochronous, the practical utility of the practice for the guide is to enable them to solicit an embodied action from the visitors hic et nunc. Hence, its recurrence in guided tours has illustrated the “iterability of solutions for coordination problems that previously worked under similar circumstances” (Deppermann and Streeck, 2018, p. 6). Grammar has proven to be a resource, but also a non-linear, micro-sequentially emerging achievement (Goodwin, 1979) that is attuned to embodied conduct and that is embedded in the participants’ organization of their interactional tasks. How guides temporally coordinate if-clauses with their embodied conduct is sensitive to a variety of contextual features (number of participants, distance from the object of interest, visibility of the object, visitors’ responsiveness, language-specific limitations and possibilities, etc.). For this reason, it appears impossible to abstract the empirical evidence in a discarnate model. Indeed, the results presented in this article hold true for the setting of guided tours, but cannot be generalized to other uses of if/then-constructions. Therefore, this study cautions against exclusively format-based approaches to language, which tend to assign specific functions to grammatical resources. It also cautions against purely pragmatic perspectives, which often identify discrete action types (e.g., requests) that are then studied in a variety of settings. If grammar is (also) a resource for organizing action, then its analysis has to take into consideration the ecological habitat in which it materializes. In the setting analyzed here, if-clauses are available to guides as a grammatical resource that enables them, in concomitance with embodied conduct, to solicit an embodied action, not an action accomplished through talk (Enfield and Sidnell, 2017). This observation provided the rationale for the notion of embodied-action projection suggested in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: http://clapi.icar.crns.fr (data in French), https://dgd.ids-mannheim.de (data in German). Data in Italian, Dutch and Flemish Sign Language have been collected by the author.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

ED conceived and designed the study, established the data collection and carried out the analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by KU Leuven under grant C14/18/034. It is a contribution to the project “Beyond the clause: Encoding and inference in clause combining,” codirected by Bert Cornillie, Kristin Davidse, ED, and Jean-Christophe Verstraete (2018–2022). The data in Italian were collected as part of the project “The constitution of space in interaction: A conversational approach to the study of place names and spatial descriptions,” directed by the author of this article and financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation under grant PP001-119138.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I thank the ICAR Lab (Lyon, France) and the Leibniz Institute for the German Language (Mannheim, Germany) for granting me access to the corpora CLAPI (Corpus de Langues Parlées en Interaction) and FOLK (Forschungs- und Lehrkorpus Gesprochenes Deutsch) respectively. I also thank Matthew Burdelski for his advice on Japanese and Isabelle Heyerick for the fieldwork that led to the recording of guided tours interpreted into Flemish Sign Language and for her help with the transcription of that data. I am also grateful to the editors and reviewers for their constructive comments on a previous version of this article.

Footnotes

1Naturally, an if-clause can also follow a main clause (see, e.g., Declerck and Reed, 2001). However, since this study homes in on the projective potential of if-clauses as observed in a specific setting of interaction (guided tours), the construction “main clause + if-clause” is not part of the collection analyzed for this article.

2All examples are taken from Sweetser’s (1990) chapter.

3In these (and other) languages, different resources may be available for expressing the token if (such as German wenn, falls, sofern or Italian se, qualora, nel caso che). The protasis can also be articulated without any if-like token (see Declerck and Reed, 2001 for English and Mazzoleni, 2001, p. 771 for Italian). For the sake of simplicity, this article uses the notion if-clause also for languages other than English.

4Similarly, for English, and based on interactional data, Lerner (1991, p. 444) observed that not all if-clauses, or first components in his terminology, are followed by second components.

5The French data are available through the CLAPI-corpus (http://clapi.icar.crns.fr), whereas the German data are taken from the FOLK-corpus (https://dgd.ids-mannheim.de) (see Acknowledgments). All the other data have been collected by the author of this article.

6Only one excerpt will be discussed for German and for Dutch (with interpretation into Flemish Sign Language) respectively, but the practice is pervasive also in these languages and more occurrences are available.

7In the transcription of signed language, the symbol | was used to indicate the simultaneous occurrence of signing with vocal turns-at-talk. The signed data were transcribed based on their grammatical function and semantic content with the help of Isabelle Heyerick.

8Although the languages studied here provide different resources for addressing a group of persons (2nd person plural in French, 2nd/3rd person plural in Italian and German, 2nd person plural or 1st person singular in Flemish Dutch), and although guides could use inclusive (1st person plural) or impersonal (3rd person singular) forms, the tendency towards using a 2nd person plural form is striking.

9In this contribution, the notions of referent and object are used interchangeably to indicate physical and visually accessible phenomena that become the focus of joint attention. The difference some authors working on joint attention and pointing make between target and referent (e.g., Stukenbrock, 2015: 72–85) is not considered here. Such a distinction is an intersubjective achievement that becomes evident as the interaction unfolds (Goodwin, 2003; Stukenbrock, 2020).

10The description of the apodosis as produced “chorally” indicates that several visitors articulate it conjointly. It does not imply that all the visitors do so.

11A change of the subject from the protasis to the apodosis is also observable in the co-constructed examples discussed by Günthner (2020: 197–201).

12The canonical construction with a fully integrated main clause in the apodosis would be Wenn wir uns den Hals anschauen, (dann) sind da so lange Stangen dran, with the finite verb sind “are” in first position of the then-clause.

13Since not all the children’s parents accepted that their children be video-recorded, the recordings do not show all the visitors involved. A detailed analysis of the visitors’ embodied conduct is hence not possible, and video stills are not provided.

14A typical phrase would be affacciarsi alla finestra, i.e., to stand at the window and look out.

15But see Burdelski’s (2021) analysis of Japanese guided tours, where he documents one case in which a guide invites joint attention with a construction involving the Japanese if-token -tara in the normatively expected clause-final position (p. 10). This is so far the only occurrence of such a use in Burdelski’s data (personal communication).

References

Auer, P. (2000). “Pre- and post-positioning of Wenn-Clauses in Spoken and Written German,” in Cause, Condition, Concession, Contrast: Cognitive and Discourse Perspectives. Editors E. Couper-Kuhlen, and B. Kortmann (Berlin: De Gruyter), 173–204. doi:10.1515/9783110219043-008

Auer, P. (2005). Projection in Interaction and Projection in Grammar. Text. 25, 7–36. doi:10.1515/text.2005.25.1.7

Auer, P. (2006). “Construction grammar meets conversation: Einige Überlegungen am Beispiel von ‘so’-Konstruktionen,” in Konstruktionen in der Interaktion. Editors S. Günthner, and W. Imo (Berlin: De Gruyter), 291–314.

Auer, P. (2009). On-line Syntax: Thoughts on the Temporality of Spoken Language. Lang. Sci. 31, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2007.10.004

K. Beijering, G. Kaltenböck, and M. S. Sansiñena (2019). Insubordination: Theoretical and Empirical Issues (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton).

Best, K. (2012). Making Museum Tours Better: Understanding what a Guided Tour Really Is and what a Tour Guide Really Does. Mus. Management Curatorship. 27, 35–52. doi:10.1080/09647775.2012.644695

Bosco, C., and Bazzanella, C. (2005). “Corpus Linguistics and the Modal Shift in Old and Present-Day Italian: Temporal Pragmatic Markers and the Case of ‘allora’,” in Corpora and Historical Linguistics. Editors C. D. Pusch, and W. Raible (Tübingen: Gunter Narr), 443–453.

Burdelski, M. (2016). We-focused and I-Focused Stories of World War II in Guided Tours at a Japanese American Museum. Discourse Soc. 27, 156–171. doi:10.1177/0957926515611553

Burdelski, M. (2021). Practices of Inviting Visitor Involvement in Storytelling within Museum Guided Tours. Handai Nihongo Kenkyuu. 33, 1–32.

Buscha, A. (1976). Isolierte Nebensätze im dialogischen Text. Deutsch als Fremdsprache. 13/5, 274–279.

Chui, K. (2009). Linguistic and Imagistic Representations of Motion Events. J. Pragmatics 41, 1767–1777. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2009.04.006

Couper-Kuhlen, E., and Selting, M. (2018). Interactional Linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

De Stefani, E. (2010). “Reference as an Interactively and Multimodally Accomplished Practice: Organizing Spatial Reorientation in Guided Tours,” in Spoken Communication. Editors M. Pettorino, A. Giannini, I. Chiari, and F. Dovetto (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 137–170.

De Stefani, E. (2021). Embodied Responses to Questions-In-Progress: Silent Nods as Affirmative Answers. Discourse Process. 58, 353–371. doi:10.1080/0163853X.2020.1836916

De Stefani, E., and Deppermann, A. (2021). Les gestes de pointage dans un environnement changeant et éphémère: les leçons de conduite. Langage et Société. 173/2, 141–166. doi:10.3917/ls.173.0143

De Stefani, E., and Mondada, L. (2014). Reorganizing Mobile Formations. Space Cult. 17, 157–175. doi:10.1177/1206331213508504

De Stefani, E., and Mondada, L. (2017). “Chapter 6. Who's the Expert?,” in Identity Struggles: Evidence from Workplaces Around the World. Editors D. Van De Mieroop, and S. Schnurr (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 95–124. doi:10.1075/dapsac.69.06des

Declerck, R., and Reed, S. (2001). Conditionals: A Comprehensive Empirical Analysis. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110851748

Deppermann, A., and Schmidt, A. (2021). Micro-sequential Coordination in Early Responses. Discourse Process. 58, 372–396. doi:10.1080/0163853X.2020.1842630

Deppermann, A., and Streeck, J. (2018). “The Body in Interaction,” in Time in Embodied Interaction: Synchronicity and Sequentiality of Multimodal Resources. Editors A. Deppermann, and J. Streeck (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 1–29. doi:10.1075/pbns.293.intro

Enfield, N., and Sidnell, J. (2017). On the Concept of Action in the Study of Interaction. Discourse Stud. 19, 515–535. doi:10.1177/1461445617730235

Evans, N. (2007). “Insubordination and its Uses,” in Finiteness: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations. Editor I. Nikolaeva (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 366–431.

Ford, C. E. (1997). “Speaking Conditionally: Some Contexts for If-Clauses in Conversation,” in On Conditionals Again. Editors A. Athanasiadou, and R. Dirven (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 387–413. doi:10.1075/cilt.143.21for

Ford, C. E., and Thompson, S. A. (1986). “Conditionals in Discourse: A Text-Based Study from English,” in On Conditionals. Editors E. C. Traugott, A. ter Meulen, J. Snitzer Reilly, and C. A. Fergusson (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 353–372. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511753466.019

Frege, G. (1923). Logische Untersuchungen. Dritter Teil: Gedankengefüge. Beiträge zur Philosophie des deutschen Idealismus 3, 36–51.

Fukuda, C., and Burdelski, M. (2019). Multimodal Demonstrations of Understanding of Visible, Imagined, and Tactile Objects in Guided Tours. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 52, 20–40. doi:10.1080/08351813.2019.1572857

Garfinkel, H., and Wieder, L. (1992). “Two Incommensurable, Asymmetrically Alternate Technologies of Social Analysis,” in Text in Context: Contributions to Ethnomethodology. Editors G. Watson, and R. M. Seiler (London: Sage), 175–206.

Gibbard, A. (1981). “Two Recent Theories of Conditionals,” in Ifs: Conditionals, Belief, Decision, Chance, and Time. Editors W. L. Harper, R. Stalnaker, and G. Pearce (Dordrecht: D. Reidel), 211–247.

Goodwin, C. (1979). “The Interactive Construction of a Sentence in Natural Conversation,” in Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology. Editor G. Psathas (New York: Irvington), 97–121.

Goodwin, C. (1980). Restarts, Pauses, and the Achievement of a State of Mutual Gaze at Turn-Beginning. Sociological Inq. 50, 272–302. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682x.1980.tb00023.x

Goodwin, C. (2003). “Pointing as a Situated Practice,” in Pointing: Where Language, Culture, and Cognition Meet. Editor S. Kita (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 217–241.

Goodwin, M. H. (1980). Processes of Mutual Monitoring Implicated in the Production of Description Sequences. Sociological Inq. 50, 303–317. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682x.1980.tb00024.x

Günthner, S. (1999). Wenn-Sätze im Vor-Vorfeld: Ihre Formen und Funktionen in der gesprochenen Sprache. Deutsche Sprache 3, 209–235.

Günthner, S. (2020). “Chapter 7. Practices of Clause-Combining,” in Emergent Syntax for Conversation: Clausal Patterns and the Organization of Action. Editors Y. Maschler, S. Pekarek Doehler, J. Linström, and L. Keevallik (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 185–220. doi:10.1075/slsi.32.07gun

Jefferson, G. (2004). “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction,” in Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation. Editor G. H. Lerner (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 14–31.

Kendon, A. (1990). Conducting Interaction: Patterns of Behavior in Focused Interaction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511807572

Krzyżanowska, K. (2015). Between if and Then: Towards an Empirically Informed Philosophy of Conditionals. [Groningen, The Netherlands]. [PhD dissertation]: University of Groningen

Laury, R. (2012). Syntactically Non-integrated Finnish jos ‘If'-Conditional Clauses as Directives. Discourse Process. 49, 213–242. doi:10.1080/0163853x.2012.664758

Lerner, G. H. (1991). On the Syntax of Sentences-In-Progress. Lang. Soc. 20, 441–458. doi:10.1017/s0047404500016572

Levinson, S. C. (2013). “Action Formation and Ascription,” in The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Editors J. Sidnell, and T. Stivers (Chichester: Blackwell), 103–130.

Lindström, J., Laury, R., and Lindholm, C. (2019). “Insubordination and the Contextually Sensitive Emergence of If-Requests in Swedish and Finnish Institutional Talk-In-Interaction,” in Insubordination: Theoretical and Empirical Issues. Editors K. Beijering, G. Kaltenböck, and M. S. Sansiñena (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 55–78.

Lindström, J., Lindholm, C., and Laury, R. (2016). The Interactional Emergence of Conditional Clauses as Directives: Constructions, Trajectories and Sequences of Actions. Lang. Sci. 58, 8–21. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2016.02.008

Lombardi Vallauri, E. (2010). Free Conditionals in Discourse. Li. 33, 50–85. doi:10.1075/li.33.1.04lom

Mazzoleni, M. (2001). “Le frasi ipotetiche,” in Grande grammatica italiana di consultazione. Editors L. Renzi, G. Salvi, and A. Cardinaletti (Bologna: il Mulino), 2, 751–784.

McNeill, D. (2000). Analogic/Analytic Representations and Cross-Linguistic Differences in Thinking for Speaking. Cogn. Linguistics. 11 (1-2), 43–60. doi:10.1515/cogl.2001.010

Mondada, L. (2012). “Deixis: An Integrated Interactional Multimodal Analysis,” in Interaction and Usage-Based Grammar Theories: What about Prosody and Visual Signals? Editors P. Bergmann, and J. Brenning (Berlin: De Gruyter), 173–206.

Mondada, L. (2018a). Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 51, 85–106. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Mondada, L. (2018b). “Chapter 13. Turn-Initial voilà in Closings in French. Reaffirming Authority and Responsibility over the Sequence,” in Between Turn and Sequence: Turn-Initial Particles across Languages. Editors J. Heritage, and M.-L. Sorjonen (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 371–412. doi:10.1075/slsi.31.13mon

M. Selting, and E. Couper-Kuhlen (2001) in Studies in Interactional Linguistics (Amsterdam: John Benjamins).

Nissi, R. (2016). Spelling Out Consequences: Conditional Constructions as a Means to Resist Proposals in Organisational Planning Process. Discourse Stud. 18, 311–329. doi:10.1177/1461445616634556

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., and Jefferson, G. (1974). A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation. Language 50, 696–735. doi:10.1353/lan.1974.0010

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511791208

Schwenter, S. A. (2006). Meaning and Interaction in Spanish Independent si-Clauses. Lang. Sci. 58, 22–34. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2016.04.007

Stirling, L. (1999). “Isolated If-Clauses in Australian English,” in The Clause in English. Editors P. Collins, and D. Lee (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 273–294. doi:10.1075/slcs.45.18sti

Stukenbrock, A. (2015). Deixis in der face-to-face-Interaktion. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110307436

Stukenbrock, A. (2018). “Chapter 11. Mobile Dual Eye-Tracking in Face-To-Face Interaction,” in Advances in Interaction Studies. Editors G. Brône, and B. Oben (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 265–302. doi:10.1075/ais.10.11stu

Stukenbrock, A. (2020). Deixis, Meta-Perceptive Gaze Practices, and the Interactional Achievement of Joint Attention. Front. Psychol. 11, 1779. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01779

Stukenbrock, A., and Birkner, K. (2010). “Multimodale Ressourcen für Stadtführungen,” in Deutschland als fremde Kultur: Vermittlungsverfahren in Touristenführungen. Editors M. Costa, and B. Müller-Jacquier (München: Judicium), 214–243.

Sweetser, E. (1990). From Etymology to Pragmatics: Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Sematic Structure. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511620904

Keywords: if/then-constructions, projection, grammar, embodiment, micro-sequentiality, interactional linguistics, conversation analysis

Citation: De Stefani E (2021) If-Clauses, Their Grammatical Consequents, and Their Embodied Consequence: Organizing Joint Attention in Guided Tours. Front. Commun. 6:661165. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.661165

Received: 30 January 2021; Accepted: 21 June 2021;

Published: 30 August 2021.

Edited by:

Simona Pekarek Doehler, Université de Neuchâtel, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Anja Stukenbrock, University of Lausanne, SwitzerlandJan Krister Lindström, University of Helsinki, Finland