95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 31 May 2021

Sec. Psychology of Language

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.660821

This article is part of the Research Topic The Grammar-Body Interface in Social Interaction View all 20 articles

Joint decision-making is a thoroughly collaborative interactional endeavor. To construct the outcome of the decision-making sequence as a “joint” one necessitates that the participants constantly negotiate their shared activity, not only with reference to the content of the decisions to be made, but also with reference to whether, when, and upon what exactly decisions are to be made in the first place. In this paper, I draw on a dataset of video-recorded dyadic planning meetings between two church officials as data, investigating a collection of 35 positive assessments with the Finnish particle ihan “quite” occurring in response to a proposal (e.g., tää on ihan kiva “this is quite nice”). The analysis focuses on the embodied delivery of these assessments in combination with their other features: their sequential location and immediate interactional consequences (i.e., accounts, decisions, abandoning of the proposal), their auxiliary verbal turn-design features (i.e., particles), and the “agent” of the proposals that they are responsive to (i.e., who has made the proposal and whether it is based on some written authoritative material). Three multimodal action packages are described, in which the assessment serves 1) to accept an idea in principle, which is combined with no speaker movement, 2) to concede to a plan, which is associated with notable expressive speaker movement (e.g., head gestures, facial expressions) and 3) to establish a joint decision, which is accompanied by the participants’ synchronous body movements. The paper argues that the relative decision-implicativeness of these three multimodal action packages is largely based on the management and distribution of participation and agency between the two participants, which involves the participants using their bodies to position themselves toward their co-participants and toward the proposals “in the air” in distinct ways.

When people meet to speak with each other, they use multiple modalities beyond speech, such as eye gaze, gestures, and body postures (Streeck et al., 2011). Research in multimodal conversation analysis (e.g., Stivers and Sidnell, 2005; Deppermann, 2013; Hazel et al., 2014) has thus demonstrated how bodily practices significantly contribute to social action in interaction. Following the same agenda, this paper focuses on the embodied delivery of positive assessments including the Finnish particle ihan “quite” (see Extract 1 below). It will be argued that, when produced during joint decision making in response to proposals, the decision-making implications of such assessments are based, among other things, on the participants using their bodies to position themselves toward their co-participants and toward the matter at hand in distinct ways.

The new focus on the body in research on social interaction has problematized, not only the logocentric bias in the analysis of social action (see e.g., Linell, 2005; Mondada, 2006; Erickson, 2010; Streeck et al., 2011; Stevanovic and Monzoni, 2016), but also the hitherto taken-for-granted analytical boundary between language and the body (e.g., Keevallik, 2018; Pekarek Doehler, 2019). This new perspective has challenged the formal linguistic perspective, where grammar has been thought of as a “device for organizing information in self-contained sentences that coherently express propositions” (Keevallik, 2018, p. 1), and instead favored the functional linguistic perspective, which promotes a more all-encompassing understanding of the nature of language. From this perspective, bodily resources have also been seen to constitute grammar in that “they form conventionalized patterns that can be abstracted and systematically described together with their social function” (Keevallik, 2018, p. 2). Thus, for example, in a series of studies on dance classes, (Keevallik, 2013; Keevallik, 2015; Keevallik, 2017a; Keevallik, 2017b) has shown that an embodied demonstration may occupy a grammatical and temporal slot within the emerging syntax and that syntax can be discontinued at a number of structural positions. As with any grammar or lexis, the deployment of such practices needs to be learned within a language community (Keevallik, 2018, p. 2).

The complex formations of the ways in which the verbal dimension of the participants’ conduct is embedded in the situated courses of action with material and embodied elements has been referred to as “multimodal gestalts” (Mondada, 2014a; Mondada, 2014c; Mondada, 2015), “social action formats” (see Rauniomaa and Keisanen, 2012), or “multimodal action packages” (Hayashi, 2005; Goodwin, 2007; Iwasaki, 2009; Lilja and Piirainen-Marsh, 2019; Pekarek Doehler, 2019; Hofstetter and Keevallik, 2020). An essential feature of such multimodal formations is that none of their single components can achieve the given action on its own. In many cases, these formations become conventional practices for achieving certain goals within a community or activity. Such conventional practices include, for example, the striking of the hammer to conclude an auction sale (Heath and Luff, 2013) or to initiate a move to a next item in the meeting agenda (Pomerantz and Denvir, 2007), completing a turn-at-play by placing a token on the game board (Hofstetter, 2020), or formalizing decisions by writing them down (Mondada, 2011; Lindholm et al., 2020).

Multimodal action packages have been shown to be sensitive to complex temporal and material contingencies. While the notion that action formation depends on the sequential position and other interactional contingencies is basic to all conversation analysis, the idea of multimodal action packages goes further. As Hofstetter and Keevallik (2020) have pointed out, some aspects of these formations “stretch the conception of actions as bounded units, instead showing them to be emergent, multimodal phenomena that appear on prepared ground”. The idea of the “prepared ground” has also been referred to as the “local ecology of action” (Mondada, 2014a; Mondada, 2014b), which is continuously changing and dynamic, providing the participants with a temporarily available set of resources to implement a range of social actions. The existence of and changes in these temporarily available sets of resources often show in the grammatical choices that participants make when designing their utterances as actions. For example, in his study on announcements of massaging procedures during massage therapy sessions, Nishizaka (2016) showed that the syntactic forms of these utterances varied relative to the stage of the ongoing therapy session and the concurrent body movements. Similarly, De Stefani and Gazin (2014) found that the inclusion of a verb in a driving teacher’s instructional turn depended on whether the instruction was provided “early” or “late” in the driving lesson. Also, in my own studies on teachers’ directives during children’s musical instrument instruction (Stevanovic, 2017; Stevanovic and Kuusisto, 2019; Stevanovic, 2020), the use of the Finnish clitic particles −pA and −pAs was found to be sensitive to the temporal trajectory of the instructional activities and to the participants’ positioning of their bodies in the physical space of the room.

In addition to their temporal and material contingencies, multimodal action packages, I argue, may also be sensitive to interpersonal concerns. On the one hand, this view draws on the perspective of functional linguistics, in which social and interpersonal matters have been seen to motivate the choice of lexical and syntactic features and thus to be central for understanding the nature of language (Keevallik, 2018, p. 1). On the other, such a view aligns with some recent, conversation-analytically-informed theorizing on action formation (e.g., Heritage, 2013; Clayman and Heritage, 2014; Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2014; Stevanovic, 2018), which has sought to explicate systematic linkages between the participants’ publicly observable features of action design and the basic facets of their momentary social relations. One interpersonal concern worth considering from this perspective is the degree of separateness vs. connectedness, or fission vs. fusion, between the participants in interaction, with reference to the social action or activity underway (Enfield, 2011; Enfield, 2013; Arundale, 2020). A key issue is the extent to which each participant is an “actor” in that action (Goffman, 1981) and whether the participants’ agency roles in relation to each other are symmetrical or asymmetrical in this respect. In general, speech favors asymmetry in that it typically involves one speaker at the time inhabiting the action underway and claiming a “sole entitlement to voice that speech” (Lerner, 2002, p. 250). In contrast, the bodily dimension of the participants’ interactional conduct is more flexible in allowing two or more participants to construct the action underway as joint (see Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2015). Such collaborative aspects of action are highlighted, for example, when participants in interaction smile and laugh together (Kangasharju and Nikko, 2009), move as a dancing couple (Broth and Keevallik, 2014), and synchronize their body sways during conversational transitions (Stevanovic et al., 2017). In this paper, the degree of fission vs. fusion in the participants’ moment-by-moment unfolding relation toward each other and toward the action or activity underway will be considered in the context of responses to proposals during joint decision-making interaction.

Joint decision-making is an integral part of our everyday social life, pertaining to both our professional activities and our mundane endeavors with family and friends. As an example, we may consider couples doing grocery shopping together at the supermarket (see e.g., De Stefani, 2013), students in a peer group choosing their next learning activities (Kämäräinen et al., 2020), and family members together interpreting inkplot images in a psychological test (Siitonen and Wahlberg, 2015). However, empirical research on naturally occurring joint decision-making interaction has shown it to be a complex interactional endeavor (Bilmes, 1981; Tysoe, 1984; Boden, 1994; Huisman, 2001; Clifton, 2009; Asmuss and Oshima, 2012; Siitonen and Wahlberg, 2015). It involves the use of multiple resources: syntax, lexical choices, prosody, body postures, material objects, and gaze, in and through which the participants manage their level of participation and the relative distribution of agency during the different phases of the process in contextually appropriate ways (Stivers, 2005; Stevanovic, 2012b; De Stefani, 2013; Stevanovic, 2013a; Kushida and Yamakawa, 2015; Stevanovic, 2015; Stevanovic et al., 2017).

Joint decision-making has been associated with certain, repeatable social actions that come across as constitutive of the entire activity. Specifically, drawing on a rich body of studies in the field of conversation analysis, joint decision-making interaction may be described with reference to sequences of proposals and responses (for a recent review, see Weiste et al., 2020). Essentially, it is through the recipients’ subsequent responses to proposals that joint decisions may emerge. In line with the classic findings on preference structure (Davidson, 1984; Pomerantz, 1984), Houtkoop (1987) showed that rejections of proposals are often delayed, whereas accepting responses to proposals are typically done straightaway. However, responses to proposals vary a lot, ranging from acceptances, through demur to complete disregard, while explicit rejections may come across as relatively rare. From this perspective, Stevanovic (2012a) suggested that joint decisions emerge when the recipients’ responses to proposals contain three components. First, the recipient claims understanding of what the proposal is about (access). Second, he or she indicates that the proposed plan is feasible (agreement). And third, he or she demonstrates willingness to treat the proposed plan as binding (commitment). If the recipient abandons the sequence before providing all these components, the proposal is de facto rejected, without the recipient needing to produce an explicit rejection of the proposal.

In addition to the three above-mentioned components, the emergence of joint decisions has also been associated with the coordinated use of other resources such as prosodic salience (Stevanovic, 2012b), matching of body sway and pitch register (Stevanovic et al., 2017), and material artifacts and writing (Lindholm et al., 2020). While reciprocal exchanges of explicit verbal commitment to a new decision (e.g., “Let’s do it!”) constitutes a common way to mark the emergence of a new decision, other resources are regularly needed to bring the joint decision-making activity effectively to a close (Stevanovic, 2012b). As I will argue in this paper, this is even more clearly so, when the verbal content of the accepting proposal response is more ambiguous, as is the case when the response consists of an utterance in the form of a positive assessments including the Finnish particle ihan “quite”.

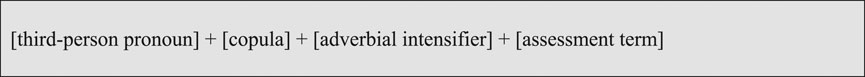

Social activities involve people routinely making assessments (Pomerantz, 1984, p. 57). According to Goodwin and Goodwin (1987), assessments are about “evaluating in some fashion persons and events being described within their talk” (p. 6) and they involve “an actor taking up a position toward the phenomena being assessed” (p. 9). In Finnish, assessments follow by and large the same syntactic form as in English (Tainio, 1996, p. 85). Rauniomaa (2007) has described Finnish assessments as including the following components: a particular referent to be assessed (third-person pronoun), a verb or a verb-like word that links the referent to the assessment (copula), and an evaluation of the referent (assessment term), which may be preceded by a scaling device that intensifies or weakens the assessment (adverbial intensifier) (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. The syntactic form of assessments in Finnish (from Rauniomaa 2007, p. 226).

Positive assessments involve a favorable evaluation of the assessable. In addition, positive assessments may also convey a deontic stance, such “deontic assessments” being frequent in response to utterances that formulate a future course of action involving both participants (Seuren, 2018). However, it is specifically in relation to their deontic nature that positive assessments are linguistically underdetermined: the overall tone of the assessment may be clearly positive but all the interactional, social, and practical consequences of the assessment for the participants may need to be inferred from the context (Stevanovic, 2012a). As I will show in this paper, this is the case especially in the context of informal planning meetings, where a positive assessment in response to a proposal may well indicate both access to the content of the proposal and agreement with the in-principle feasibility of the idea, but not necessarily any commitment to future action.

In this paper, I will analyze positive assessments including the Finnish particle ihan produced in response to a proposal. Finnish is typologically a “particle language”, where a rich set of particles may be used to guide recipients’ inferences of what the speakers are momentarily up to, without the particles actually altering the propositional content of the clause (Koivisto, 2016). In the above-depicted syntactic form of Finnish assessments, the place of the adverbial intensifier is commonly inhabited by the particle ihan, which has been classified as an intensity particle (Hakulinen et al., 2004, p. 814). However, as a scaling device that either intensifies or weakens the assessment, ihan has two different functions depending on the subsequent adjective1 whose intensity it modifies. In the context of a negative assessment, such as se on ihan perseestä “it is IHAN bollocks”, the particle ihan generally intensifies the assessment and thus translates as “really”. In contrast, in the context of positive assessments, the situation is more complex. In many positive assessments such as se on ihan hyvä “it is IHAN good”, which this paper focuses on, the particle ihan weakens.2 the intensity of the subsequent adjective and may be best translated as “quite”.3

According to Hakulinen and colleagues (2004, p. 815), ihan may be used to relate the following adjective or another type of assessment term to some contrasting feature arising from the context. As part of positive assessments produced in responses to proposals, many contrasting contextual features are thinkable. For example, such features could involve the ideas 1) that the proposed idea is good enough, even if others may have thought otherwise, 2) that the proposed idea is good enough, because better solutions to the current problem may not be available to the participants, and 3) that the proposed idea sounds good even if the speaker has no say in its realization or is reluctant to consider the idea in detail. In all cases, ihan weakens the positively evaluative aspect of the assessment, without yet excluding the possibility that a proposed idea may still be worthy of a decision. Furthermore, in some cases, the particle ihan also adds to the positive assessment a “fatalistic” flavor, conveying that the proposed idea must do, given the current circumstances (cf. on “fatalistic” prosody, see Stevanovic 2012b). Thus, as verbal constructions, positive ihan assessments may imply the emergence of a joint decision but this interpretation or outcome is not inevitable.

Given the ambiguity of positive assessments including the Finnish particle ihan “quite” as responses to proposals, in this study, I investigate the participants’ bodily behaviors and other behavioral and contextual features that accompany the delivery of these assessments, considering the preconditions and the interactional consequences of the assessments in each case. My investigation is guided by the following research questions:

(1) What types of “multimodal action packages” may be associated with the delivery of the positive ihan assessments as a response to proposals?

(2) How can we account for the role of the bodily behavioral components in these multimodal action packages?

My data consist of fifteen video-recorded planning meetings, where pastors and cantors discuss and make decisions concerning their joint work tasks. Although pastors and cantors have their own territories of knowledge and expertize, the precise distribution of the deontic rights between them mostly cannot be assumed a priori–except, perhaps, for the content of the sermon (the pastor’s domain) and the choice of the organ postlude (the cantor’s domain). This means that any symmetrical distribution of deontic rights between the participants is interactionally achieved, as proposals are transformed into joint decisions. In addition to proposals, planning meetings also involve discussion about plans made earlier by one of the participants. Although there are plans that may be realized without the co-worker approving them, the participants may still sometimes want to share them, for example, for the purposes of affiliation (see e.g., Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2014, pp. 198–200).

The data were collected in seven congregations in the regions of several bishoprics of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland during the spring of 2008 (for a more detailed description of the data set, see Stevanovic, 2013b). The data were transcribed according to the conventions developed by Gail Jefferson (Schegloff, 2007, 265–269; see Supplementary Appendix A1), and analyzed with conversation analysis (Heritage, 1984; Schegloff, 2007). The data extracts analyzed in this paper were additionally glossed verbatim in English (see Supplementary Appendix A2).

While there are about 300 proposal sequences in these data, this paper focuses on the sub-collection of these sequences that involve a positive assessment with the particle ihan as a response to a proposal. In these positive assessments (N = 35), the particle ihan is placed as an adverbial intensifier before the assessment term, as shown in Figure 1 above. The assessment term may be either an adjective or a noun phrase involving an adjective.

My analysis proceeded through three phases. First, I asked about the nature of the proposal that the positive ihan assessment was responsive to: How was the proposal sequentially placed in relation to a possibly emerging decision? Was it genuinely about suggesting joint decision-making on some matter or was it more like a request for the recipient to confirm the reception of a decision made unilaterally by the speaker? Second, I analyzed the participants’ embodied conduct during the delivery of the positive ihan assessment: What types of body movements were the participants engaged in? Were both participants moving or was it either the proposer or the proposal recipient? Finally, I brough the outcomes from these two phases of investigation to bear on one another and identified three multimodal action packages that seemed to serve distinct functions in response to proposals.

In this section, I will describe the three multimodal action packages surrounding the delivery of positive ihan assessments in response to proposals. In the first package, the assessment is used to accept an idea in principle, without the assessment leading to a decision. In the second package, the assessment serves as a way for the speaker to concede to an idea that the co-participant has already decided upon. In the third package, the participants display joint commitment to a new decision and bring the sequence collaboratively to a close. In what follows next, I will discuss these three packages one at a time.

As pointed out above, joint decisions emerge when the recipients’ responses to proposals involve a claim of understanding of what the proposal is about (access), an indication that the proposed plan is feasible (agreement), and a demonstration of willingness to treat the decision as binding (commitment), while the sequence can be abandoned before these components have been provided (Stevanovic, 2012a). This outcome seems to be the case in the two cases analyzed below. In these instances, the proposal recipient offers a positive assessment of the proposed idea, such in-principle acceptance of the idea serving to indicate access and agreement, but not commitment.

In Extract 2, a pastor (p) and a cantor (C) are trying to select hymns for a mass. The participants have previously brought up several hymns as viable options and at the beginning of the extract the cantor makes yet another proposal by referring to a possible hymn by name (line 1). This is followed by the pastor’s positive evaluation of the hymn (line 2).

In this context, the cantor’s initiating turn (line 1) may be heard as a proposal for a hymn to be sung in the mass and, in his responsive turn, also the pastor seems to treat it as such. In the first part of his responsive turn, the adverbial intensifier ihan is preceded by the particle kyllä “certainly”, which conveys its speaker’s knowledgeable status (Keevallik and Hakulinen, 2018), and it is followed by the adjective hyvä “good”, which marks the assessment as a positive one. After a silence, however, the pastor augments the assessment term to include, besides the adjective hyvä “good”, also the noun alkuvirsi “opening hymn”. The ensuing noun phrase (“a good opening hymn”) not only assesses the hymn but also specifies its placement in the mass. In so doing, the pastor underlines the decision-making relevance of his action, as it is typical to select hymns in the chronological order in which they are sung in the mass. The decision-making relevance is further emphasized by the turn-final particle että, which is typically used to leave some aspect of the turn implicit and to invite the recipient to deal with that implication (Koivisto, 2014). Thus, in this case, a conclusion arises that the hymn is good enough for the present purposes and thus worth choosing. However, these cues seem not to be enough to establish a decision and bring the sequence to a close. Instead, a 2 s-long silence ensues (line 3). Thereafter, the cantor breaks the silence by producing a positive assessment of another possible opening hymn (lines 4–5), thus abandoning her previous proposal and replacing it by making a new one.

As for the participants embodied behaviors during the extract, the cantor first keeps on looking at the pastor (Frame 1) but drops her gaze in the middle of the 2 s silence that follows the pastor’s positive ihan assessment turn (Frame 2). During the sequence, the cantor is also producing small hand gestures, thus displaying engagement in the current talk (see Frames 1 and 2). This is where the pastor’s behavior is in stark contrast to that of the cantor: he is physically completely still. During his positive ihanassessment turn, he looks at the cantor, but produces no head or hand movements and no observable changes of facial expression (Frames 1 and 2). All this contributes to the interpretation of the pastor’s behavior as accepting the cantor’s proposal in principle while simultaneously conveying that no final decision has been reached.

Extract 3 is from the end of a different meeting where a pastor (p) and a cantor (C) have been planning activities for school children–more specifically a church event to be realized at the end of the spring semester, which is approaching in a month. Just previously, however, the cantor has started describing her proposal for a Christmas play that they could prepare for the school children at the end of the year. The beginning of the extract shows the final part of the cantor’s long description (lines 1, 2, and 4) and the pastor’s response to it, which involves three minimal responses (lines 3, 5, and 7) and a positive ihan assessment (line 7).

The pastor’s positive ihan assessment (line 7) may be heard as an invitation to bring the sequence toward a closure. The cantor, however, does not finish, but instead, in overlap with the pastor’s assessment, continues her detailed Christmas play description (lines 9–23; lines 11–23 not shown in the transcript). Thereafter, the cantor provides an assessment of the previous Christmas plays having been “laborious” (lines 24–25), thus implying that her current idea would be different in this respect and therefore worthwhile. Notably, however, the pastor does not respond when given a slot to do so (see the cantor’s stretched turn final syllables in line 25 and the silence in line 26). Finally, the cantor wraps up her description with a summarizing utterance (mut et ihan ninku tän tyyppinen “but that just like this type of (thing)”, lines 27 and 31), which the pastor receives first with minimal response tokens (line 28) and then with a more substantial response (lines 30 and 33). The pastor’s more substantial response does not, however, include any explicit assessment of the cantor’s idea. Instead, it makes a blunt appeal to postpone further discussion on the topic until the autumn. The cantor responds by accounting for her sudden motivation to discuss Christmas play issues (line 34–35) and brings—together with the pastor—not only the sequence but also the entire meeting to a close (lines 39–43).

During the pastor’s positive ihan assessment turn, the cantor carries on with her telling in overlap with the pastor, being continuously engaged with the pastor through her gaze and gestures (see Frames 1 and 2). The pastor, in contrast, is physically completely still, just like his colleague in Extract 2. He looks at the cantor but produces his positive ihan assessment turn with no head or hand movements and no observable changes of facial expression.

In sum, the positive ihan assessment turns in Extracts 2 and 3 shared the following features: 1) they were provided in response to proposals with observable decision-making implications, 2) they were produced with no body movement by the speaker, 3) they conveyed the speaker’s acceptance of the proposal in principle but were followed by the participants circumventing joint decision-making either by abandoning the proposal or postponing the decision-making to the future.

Proposals for future action may sometimes be produced in ways that do not genuinely invite joint decision-making about its details (see e.g., Stevanovic et al., 2020). Instead, the speaker implies that a decision has already been made, either unilaterally by the speaker or collaboratively by a group of people that includes the proposal speaker but excludes the recipient. The proposal speaker nonetheless offers his or her plan for the recipient to acknowledge or confirm, thus seeking to establish some “symmetry of deontic rights” (e.g., Stevanovic, 2013a) between the participants. This is another interactional environment where response to proposals in the form of positive ihan assessments occur in my data. As I will argue below, in these instances, the recipient not only acknowledges a new piece of information as received, but also concedes to a previously established plan with specific displays of agency comparable to ones described in earlier literature (see e.g., Kent, 2012; Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012; Ekberg and LeCouteur, 2015; Stevanovic and Monzoni, 2016; Keevallik, 2017a; Ekberg and LeCouteur, 2020).

In Extract 4, a pastor (p) and a cantor (C) are discussing a singing event. At the beginning of the extract, the cantor tells the pastor about an idea that she has previously agreed on with some other church workers and which concerns the entire series of singing events that she is organizing (lines 1–3, and 5). Although the pastor will only be visiting one of these events to give a devotional speech and his approval is thus not necessary for the realization of the idea, the cantor nonetheless asks the pastor’s opinion about it (line 5).

The pastor responds to the cantor’s plan description by producing a positive ihan assessment turn (line 5), in which the turn-initial particle no “well” stresses its concessive character (see Vepsäläinen, 2019) and the turn-final joo indicates readiness for sequence closure (Hakulinen, 2001, p. 7). During the turn the pastor raises his eyebrows and turns his head and gaze away from the cantor (see Frames 1 and 2), thus producing a public performance of “doing thinking” (Brouwer, 2003, p. 540). Subsequently, the cantor accounts for the plan (lines 8, 9, and 11), which is accompanied by the pastor providing yet another account for the reasonability of the plan (lines 10, 12–13, 16, and 18). All in all, the pastor seems not only to be acknowledging some new piece of information as received, but he is also actively engaged in displaying some “ownership of the decision” (Clifton, 2009).

In Extract 5, a pastor (p) and a cantor (C) are talking about a confirmation school that they are soon going to teach. At the beginning of the extract, the pastor tells the cantor about his plan for the event, which would involve them singing hymns together with the children (lines 1, 4, and 6). While it is certainly polite to tell the cantor about such plans in this type of a meeting, in principle, such a plan could have been realized anyway—by simply announcing the hymns in the confirmation school.

The cantor conveys acceptance of the pastor’s plan with several “yeah” and “yes” tokens (lines 3, 5, and 8). Thereafter, she produces an account that highlights the virtues of the plan (lines 10–13), the turn-initial siis “I mean” framing the turn as a specification of her initial acceptance. On this basis the cantor ends up concluding that the plan is ihan hyvä “quite good”, while the long and audible inbreath and a silence before the assessment adds a concessive flavor to it (line 14). The production of the assessment is accompanied by the cantor’s hand gesture (Frame 1) and an affective head shake (cf. Goodwin, 1980), in which she first turns her head away from the pastor (Frame 2) and then immediately back (Frame 3). Thereafter, the cantor introduces a new idea based on the pastor’s plan (line 16), thus implicitly claiming partial ownership of it.

Hence, the positive ihan assessment turns in Extracts 4 and 5 involved the following common features: 1) they were provided in response to proposals with less obvious joint decision-making implications, 2) they were accompanied by turn-design features underlining their concessive character, 3) they were associated with notable body movement by the speaker, and 4) they were surrounded by the speaker extensively accounting for the reasonability of his or her co-participant’s already-made plan, which served to underscore the speaker’s agency in the face of his or her consent.

Finally, there are positive ihan assessment turns that effectively lead to the participants establishing a joint decision in the here and now of the encounter. As I will argue below, this outcome is enabled by the deployment of a variety of resources that, not only emphasize the decision-making relevance and deontic nature of the assessment (see Seuren, 2018), but also underline and work to construct a shared distribution of agency and symmetry between the two participants with regard to their deontic rights and ownership of the emerging decision. In my collection, such symmetry is most evident in cases where the “source” of the proposal under consideration is neither of the participants alone, but it is based on a document (e.g., Church Manual) or suggested by a person or an instance external to the encounter.

In Extract 6, a pastor (p) and a cantor (C) are discussing a potential hymn for the following Sunday’s mass, which has been proposed by another pastor who is not present at the meeting. Previously, the cantor has read out loud the lyrics of the hymn, the end of the reading showing at the beginning of the extract (line 1). This leads to the cantor concluding that the hymn is ihan hyvä “quite good” (line 5).

The matter that the origins of the proposal lie outside the current encounter allows the participants to position themselves relatively symmetrically in relation to each other, as regards the “ownership” of the proposal. This symmetricity is further facilitated by the cantor reading out loud the hymn lyrics (line 1), whereby she creates shared access to the detailed content of the proposal. The shared access is established by the pastor acknowledging the receipt of the cantor’s reading with a minimal response token (line 3).

The cantor’s subsequent assessment of the hymn (line 5) is both deontically conclusive.6 and indicative of a shared distribution of participant agency. The deontic conclusiveness is highlighted by the cantor prefacing the assessment with a particle chain no ni.7, which may be best translated as “okay”. The shared distribution of agency again is visible in two aspects of the participants’ conduct: First, the pastor participates in the cantor’s positive ihan assessment by stating “good” and “yeah” (line 6) in overlap with the cantor. Second, during the cantor’s assessment turn the two participants lean backwards in perfect synchrony. In this context, the movement seems to signal joint understanding of a transition from a previous joint decision-making sequence to a new one (Stevanovic et al., 2017). A new sequence is indeed launched right after this, as shown at the end of the extract (line 9).

In Extract 7, the same participants are discussing another hymn, which has also been suggested by a pastor external to the current encounter. At the beginning of the extract, the cantor comments on the melody of the hymn (lines 1–2), which is followed by a silence (line 3), affirmative response token “yeah” (line 4), a particle chain no ni “okay” (line 6), and a positive assessment with the particle ihan (line 6). The pastor remains silent throughout the extract.

Also in this case, the cantor’s positive ihan assessment turn is preceded by her establishing shared access to the matter at hand (lines 1–2) and highlighting the deontic conclusiveness of the assessment by prefacing it with “yeah” (line 4) and “okay” (line 6). Likewise, the production of the assessment turn is accompanied with remarkably synchronous body movements by the two participants: after the cantor’s particle chain no ni “okay” both participants, who have previously been looking down at their hymnals (Frame 1), straighten their torsos, raise their heads, and gaze upward (Frames 2 and 3), which is followed by the cantor launching a new sequence (lines 7–8). Thus, even though the pastor does not say anything during the end phase of this joint decision-making sequence, her embodied behavior, which is carefully coordinated with that of the cantor, marks the emergence of the decision as a collaborative achievement.

Extract 8, which is drawn from another meeting with a different set of participants, follows a similar pattern. In this case, a pastor (p) and a cantor (C) are discussing a specific proposal for an opening hymn for the next Sunday’s mass, which has been provided by the Church Manual. Similar to Extracts 6 and 7, also this case is characterized by a shared orientation to access, which is here established by the cantor singing the hymn (lines 1–2). Subsequently, the cantor provides two different positive ihan assessments of the hymn (lines 3 and 6). However, unlike in Extracts 6 and 7, the “particle display” of deontic conclusiveness of the assessment is not signaled by the cantor but by the pastor (line 5), who produces a long-stretched states no niin “okay” after the cantor’s first positive ihan assessment.

As in Extracts 6 and 7, the participants engage in a joint display of understanding that a decision is established and that the sequence should be ended. Also in this case, the participants’ synchronous body movements are a key component of this shared orientation. Here, the pastor’s noni “okay” (line 5) is accompanied by both participants starting to move their writing hands. Thereafter, during the cantor’s second positive ihan assessment turn (line 6), the participants lower their head and torso (Frames 1 and 2) and start writing (Frame 3). After a silence (line 7), the cantor launches a new sequence (line 8), thus finalizing the transition in a way analogous to Extracts 7 and 8.

In sum, the positive ihan assessment turns in Extracts 6–8 shared the following features: 1) they were provided in response to proposals toward which the participants were positioned relatively symmetrically to begin with, 2) they were prefaced with lexical markings of deontic conclusiveness (e.g., particle chain no ni “okay”), 3) they were produced with both participants engaging in body movements that exhibited a high degree of synchronicity, and 4) they were followed by a sequential closure and a transition to a new sequence, which in this context serve to indicate that a new, joint decision has been established.

In this paper, I have analyzed responses to proposals in the form of positive assessments with the Finnish particle ihan “quite”, mapping out their interactional functions in informal planning meetings between two church officials. The analysis focused on the use of these assessments in combination with other features of their delivery: the “origins” of the proposals that they are responsive to (i.e., a person or an instance internal vs. external to the encounter), their sequential location and immediate interactional consequences (i.e., accounts, decisions, abandoning of the proposal), their auxiliary verbal turn-design features (i.e., particles), and the participants’ bodily conduct during them (e.g., movements of hands and upper body, gaze, head gestures, facial expressions, degree of synchronicity of movement). As a result, three multimodal action packages were described. First, some positive ihan assessments were shown to be able to serve the mere “in-principle” acceptance of an idea, in which case the assessments were produced with no body movement by the speaker. Second, other positive ihan assessments seemed to convey concession to an already-made plan, in which case the assessments were accompanied with turn-design features underlining their concessive character, surrounded by the speaker extensively accounting for the reasonability of the idea, and associated with notable expressive body movement by the speaker. Third, and finally, there were positive ihan assessments in the data that served the establishing of a joint decision. In these instances, the assessments were provided in response to proposals toward which the participants were positioned relatively symmetrically to begin with, while the assessment turns were prefaced with lexical markings of deontic conclusiveness (i.e., no ni “okay”) and produced with both participants’ body movements exhibiting a high degree of synchronicity.

These results indicate that establishing joint decisions is essentially a matter of the successful coordination of sequential transitions. The participants need to have a common understanding when a decision has been reached and bring the sequence coordinately to a close, which may involve physical movements of the body. In this respect, the present findings are consistent with the ones from previous conversation-analytic studies, which have generally associated postural change with sequence closure (e.g., Schegloff, 1998; Li, 2014; Mondada, 2015). However, one might argue that managing a successful sequential transition is of specific importance for participants engaged in joint decision-making interaction. To launch a new sequence at a point at which the recipient has not yet assessed the content of the proposed idea is to establish a unilateral decision, while refraining from actively forwarding the interaction toward a decision is to reject a decision de facto (Stevanovic, 2012a). Thus, to establish a genuinely joint decision may call for what Enfield (2013) has referred to as the “the fusion, or unifying, of agency across and among individuals” (p. 104). This fusion, as has been specifically shown in this paper, may manifest as a high level of synchronicity in the participants’ body movements. In this respect, the findings of this paper are in line with a previous conversation-analytically informed movement-capture study on joint decision-making by myself and my colleagues (Stevanovic et al., 2017), in which we found that the instances of highest body sway synchrony between participants occurred during transitions from one joint decision-making sequence to a next.

While the fusion or unifying of agency between two or more individuals may thus characterize the emergence of joint decisions, the fission or dividing of agency is the inverse of this, and it may be associated with outcomes other than joint decisions (see Enfield, 2013; Arundale, 2020). Previous research has shown that public displays of physical bodily engagement are an essential part of managing agency and participation (e.g., Scheflen, 1972; Kendon, 1990; Goodwin and Goodwin, 2004). Physical bodily engagement reflects, constructs, and manifests the extent to which a person is willing to invest in the social action underway both affectively and cognitively. While agency and participation may thus be argued to have a bodily correlate, the exact ways in which the participants may use their bodies to manage participation are varied. As has been pointed out by Enfield (2013), “body movements of various kinds that would not normally be regarded as gesture—e.g., shifting in one’s chair—also tend to be temporally regulated in some way with relevance to the speech, with diagrammatic relevance to discourse structure” (p. 66). What seems to be relevant in determining whether the embodied features of the delivery of a positive ihan assessment steer the interpretation of the utterance toward an interpersonal fusion or fission is the gestalt constituted by these features. Are the participants moving together, as in Extracts 6–8 (fusion)? Or are there notable asymmetries between the participants in this respect, with one participant extensively moving and/or the other avoiding all visible movement altogether, as in Extracts 2–5 (fission)?

As pointed out above, the present findings are also consistent with previous conversation-analytic research, which has shown that conceding to a unilateral decision is not always interactionally an easy task but may involve specific displays of agency (see e.g., Kent, 2012; Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012; Ekberg and LeCouteur, 2015; Stevanovic and Monzoni, 2016; Keevallik, 2017b; Ekberg and LeCouteur, 2020). In line with what has been suggested previously, I argue that these specific displays of agency may also involve various “solo body movements”. However, what has been discussed less in the literature so far, is the potential affordance of a “movement freeze” to modify the interactional import of an assessment. It is the task of future research to consider whether this resource might work in an analogous way also in activity contexts other than joint decision making.

As this study has highlighted, social interaction is not only about organizing utterances and embodied behaviors into chains of initiating and responsive actions (Schegloff, 2007), but it is also more generally about the management of participation (Goffman, 1981; Rae, 2001) and agency (Kockelman, 2007; Enfield, 2011). More specifically, the analysis has shown that the relative decision-implicativeness of the three different multimodal action packages surrounding a positive ihan assessment is largely based on the degree of fission vs. fusion between the two participants, as to how they position themselves toward each other and to the proposal “in the air”. As a key aspect of the continuously changing “local ecology of action” (Mondada, 2014a; Mondada, 2014b), the degree of fission vs. fusion between the participants provides them with a temporarily available set of resources to accept ideas in principle, to concede to an already-made plan and to establish a joint decision, while the degree of fission vs. fusion is also reconstructed, negotiated or maintained by each new contribution in the unfolding action or activity. When considered through this conceptual lens, the multitude of forms that participants’ bodily behaviors can take may be grasped as instantiations of specific more comprehensive gestalts, whose interactional import may then be subjected to systematic analysis.

The analysis of this paper has demonstrated one way in which grammar and the body interact. They act synchronously, with embodied conduct augmenting and differentiating the interactional corollaries of a precise grammatical construction. In addition, the paper has advocated a view that is consistent with both the perspective of functional linguistics, which acknowledges social and interpersonal concerns as central for understanding language (Keevallik, 2018), and the recent conversation-analytically informed theorizing on the basic connections between action formation and social relations (e.g., Heritage, 2013; Clayman and Heritage, 2014; Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2014; Stevanovic, 2018). In this vein, the paper suggests that the ways in which participants are momentarily related toward each other and to the action or activity underway may also be considered as part of the structures of language use and thus also as part of the phenomenal field generally called “grammar”. As has been pointed out by Goffman (1981), “we quite routinely ritualize participation frameworks … in linguistic terms, we not only embed utterances, we embed interaction arrangements” (p. 153). What is needed therefore is a systematic investigation of these interaction arrangements as they reflect and translate into the moment-by-moment relational dynamics between the participants and manifest in their uses of both language and body.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Data consists of video recordings with identifiable participants and the author has no permission from the participants to make the data publicly available. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to bWVsaXNhLnN0ZXZhbm92aWNAdHVuaS5maQ==.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MS is the sole author of this paper.

This study was financially supported by the University of Helsinki.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.660821/full#supplementary-material

1The particle ihan can also be used as an intensifier in combination words other than adjectives, for example, before verbs (Minä ihan liikutuin “I was IHAN moved”) and nouns (Taidatkin olla ihan lintumiehiä “You seem to be IHAN a birdwatcher”; Hakulinen et al., 2004, p. 815).

2There are also several positive adjectives (e.g., mahtava “terrific”) that may be intensified by a preceding ihan, but positive assessments with these particular adjectives have been excluded from this study.

3The accuracy of the English translation of ihan as “quite” depends on the variety of English. The translation works best from the perspectives of those varieties where “quite” weakens the quality of the subsequent adjective.

4Although the word aika may here be best translated as “quite” and it occurs in a context very similar to the target phenomenon of this study, I am not making any claims about the use of aika in positive assessment, let alone suggesting interchangeability between aika and ihan.

5This is a form of ihan in which the final “n” is inaudible.

6By “deontic conclusiveness” I refer to a display of deontic rights by the way of implementing an action (e.g., formulating a decision) that is combined with an initiative to conclude the participants’ current sequence or activity.

7The particle chain no ni has various usages, but one that is relevant for the present considerations is the launching of a transition from one conversational phase to a next (Raevaara, 1989, p. 149). The particle chain may be found, for example, at the beginning of turns suggesting a closure of a telephone call (see e.g., Sorjonen 2001, p. 205). Translating no ni as “okay” is based on the common cross-language usage of “okay” as a marker of transition and closure (Mondada and Sorjonen, 2021).

Arundale, R. B. (2020). Communicating and Relating: Constituting Face in Everyday Interacting. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190210199.001.0001

Asmuss, B., and Oshima, S. (2012). Negotiation of Entitlement in Proposal Sequences. Discourse Stud. 14 (1), 107–126. doi:10.1177/1461445611427215

Bilmes, J. (1981). Proposition and Confrontation in a Legal Discussion. Semiotica 34, 251–275. doi:10.1515/semi.1981.34.3-4.251

Broth, M., and Keevallik, L. (2014). Getting Ready to Move as a Couple. Space Cult. 17 (2), 107–121. doi:10.1177/1206331213508483

Brouwer, C. E. (2003). Word Searches in NNS-NS Interaction: Opportunities for Language Learning?. Mod. Lang. J 87, 534–545. doi:10.1111/1540-4781.00206

Clayman, S. E., and Heritage, J. C. (2014). “Benefactors and Beneficiaries,” in Requesting in Social Interaction. Editors P. Drew, and E. Couper-Kuhlen (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 55–86. doi:10.1075/slsi.26.03cla

Clifton, J. (2009). Beyond Taxonomies of Influence: “Doing” Influence and Making Decisions in Management Team Meetings. J. Business Commun. 46 (1), 57–79. doi:10.1177/0021943608325749

Davidson, J. A. (1984). “Subsequent Versions of Invitations, Offers, Requests, and Proposals Dealing with Potential or Actual Rejection,” in Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Editors J. M. Atkinson, and J. Heritage (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 102–128.

De Stefani, E., and Gazin, A.-D. (2014). Instructional Sequences in Driving Lessons: Mobile Participants and the Temporal and Sequential Organization of Actions. J. Pragmatics 65, 63–79. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2013.08.020

De Stefani, E. (2013). “The Collaborative Organisation of Next Actions in a Semiotically Rich Environment: Shopping as a couple.”,” in Interaction and Mobility. Language and the Body in Motion. Editors P. Haddington, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Berlin: De Gruyter), 123–151.

Deppermann, A. (2013). Special Issue: Conversation Analytic Studies of Multimodal Interaction. J. Pragmatics 46 (1), 1–7.doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2012.11.014

Ekberg, K., and LeCouteur, A. (2015). Clients' Resistance to Therapists' Proposals: Managing Epistemic and Deontic Status. J. Pragmatics 90, 12–25. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2015.10.004

Ekberg, K., and LeCouteur, A. (2020). “Clients' Resistance to Therapists' Proposals: Managing Epistemic and Deontic Status in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Sessions,” in Joint Decision Making in Mental Health. Editors C. Lindholm, M. Stevanovic, and E. Weiste (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 95–114. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-43531-8_4

Enfield, N. (2011). “Sources of Asymmetry in Human Interaction: Enchrony, Status, Knowledge and agency,” in The Morality of Knowledge in Conversation. Editors T. Stivers, L. Mondada, and J. Steensig (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 285–312.

Enfield, N. J. (2013). Relationship Thinking: Agency, Enchrony, and Human Sociality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Erickson, F. (2010). “The Neglected Listener,” in New Adventures in Language and Interaction. Editor J. Streeck (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 243–256. doi:10.1075/pbns.196.11eri

Goodwin, C., and Goodwin, M. H. (1987). Concurrent Operations on Talk. IPrAPiP 1, 1–54. doi:10.1075/iprapip.1.1.01goo

Goodwin, C., and Goodwin, M. (2004). “Participation,” in Companion to Linguistic Anthropology. Editor A. Duranti (Oxford: Basil Blackwell), 222–243.

Goodwin, M. H. (1980). Processes of Mutual Monitoring Implicated in the Production of Description Sequences. Sociological Inq. 50, 303–317. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.1980.tb00024.x

Goodwin, C. (2007). Participation, Stance and Affect in the Organization of Activities. Discourse Soc. 18, 53–73. doi:10.1177/0957926507069457

Hakulinen, A., Vilkuna, M., Korhonen, R., Koivisto, V., Heinonen, T. R., and Alho, I. (2004). Iso Suomen Kielioppi [The Comprehensive Grammar of Finnish]. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

Hakulinen, A. (2001). Minimal and Non-minimal Answers to Yes-No Questions. Prag 11 (1), 1–15. doi:10.1075/prag.11.1.01hak

Hayashi, M. (2005). Joint Turn Construction through Language and the Body: Notes on Embodiment in Coordinated Participation in Situated Activities. Semiotica 2005, 21–53. doi:10.1515/semi.2005.2005.156.21

Hazel, S., Mortensen, K., and Rasmussen, G. (2014). Introduction: A Body of Resources - CA Studies of Social Conduct. J. Pragmatics 65, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2013.10.007

Heath, C., and Luff, P. (2013). Embodied Action and Organisational Interaction: Establishing Contract on the Strike of a Hammer. J. Pragmatics 46 (1), 24–38. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2012.01.002

Heritage, J. (2013). Action Formation and its Epistemic (And Other) Backgrounds. Discourse Stud. 15 (5), 551–578. doi:10.1177/1461445613501449

Hofstetter, E., and Keevallik, L. (2020). Embodied Interaction. Handbook Pragmatics: 23rd Annu. Installment 23, 111–138. doi:10.1075/hop.23.emb2

Hofstetter, E. (2020). Achieving Preallocation: Turn Transition Practices in Board Games. Discourse Process. 58, 113–133. doi:10.1080/0163853X.2020.1816401

Houtkoop, H. (1987). Establishing Agreement: An Analysis of Proposal-Acceptance Sequences. Dordrecht, NL: Foris Publications. doi:10.1515/9783110849172

Huisman, M. (2001). Decision-making in Meetings as Talk-In-Interaction. Int. Stud. Manage. Organ. 31 (3), 69–90. doi:10.1080/00208825.2001.11656821

Iwasaki, S. (2009). Initiating Interactive Turn Spaces in Japanese Conversation: Local Projection and Collaborative Action. Discourse Process. 46 (2-3), 226–246. doi:10.1080/01638530902728918

Kämäräinen, A., Eronen, L., Björn, P. M., and Kärnä, E. (2020). Initiation and Decision-Making of Joint Activities within Peer Interaction in Student-Centred Mathematics Lessons. Classroom Discourse, 1–20. doi:10.1080/19463014.2020.1744457

Kangasharju, H., and Nikko, T. (2009). Emotions in Organizations: Joint Laughter in Workplace Meetings. J. Business Commun. 46 (1), 100–119. doi:10.1177/0021943608325750

Keevallik, L., and Hakulinen, A. (2018). Epistemically Reinforced Kyl(lä)/küll-Responses in Estonian and Finnish: Word Order and Social Action. J. Pragmatics 123, 121–138. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2017.01.003

Keevallik, L. (2013). The Interdependence of Bodily Demonstrations and Clausal Syntax. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 46 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/08351813.2013.753710

Keevallik, L. (2015). “Coordinating the Temporalities of Talk and Dance,” in Temporality in Interaction. Editors A. Deppermann, and S. Günthner (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 309–336. doi:10.1075/slsi.27.10kee

Keevallik, L. (2017a). “Linking Performances: The Temporality of Contrastive Grammar,” in Linking Clauses and Actions in Social Interaction. Editors R. Laury, M. Etelämäki, and E. Couper-Kuhlen (Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society), 54–73.

Keevallik, L. (2017b). “Chapter 9. Negotiating Deontic Rights in Second Position,” in Imperative Turns at Talk: The Design of Directives in Action. Editors M.-L. Sorjonen, L. Raevaara, and E. Couper-Kuhlen (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 271–295. doi:10.1075/slsi.30.09kee

Keevallik, L. (2018). What Does Embodied Interaction Tell Us about Grammar? Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 51 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413887

Kendon, A. (1990). Conducting Interaction: Patterns of Behavior in Focused Encounters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kent, A. (2012). Compliance, Resistance and Incipient Compliance when Responding to Directives. Discourse Stud. 14, 711–730. doi:10.1177/1461445612457485

Koivisto, A. (2014). “Utterances Ending in the Conjunction Että,” in Contexts of Subordination: Cognitive, Typological, and Discourse Perspectives. Editors J. Kalliokoski, and H. L. Visapää Sorva (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 223–244. doi:10.1075/pbns.249.09koi

Koivisto, A. (2016). Receipting Information as Newsworthy vs. Responding to Redirection: Finnish News Particles Aijaa and Aha(a). J. Pragmatics 104, 163–179. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.03.002

Kushida, S., and Yamakawa, Y. (2015). Fitting Proposals to Their Sequential Environment: A Comparison of Turn Designs for Proposing Treatment in Ongoing Outpatient Psychiatric Consultations in Japan. Sociol. Health Illn 37 (4), 522–544. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12204

Lerner, G. H. (2002). “Turn-sharing: The Choral Co-production of Talk-In-Interaction,” in The Language of Turn and Sequence. Editors C. E. Ford, B. A. Fox, and S. A. Thompson (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 225–256.

Li, X. (2014). Leaning and Recipient Intervening Questions in Mandarin Conversation. J. Pragmatics 67, 34–60. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2014.03.011

Lilja, N., and Piirainen-Marsh, A. (2019). How Hand Gestures Contribute to Action Ascription. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 52 (4), 343–364. doi:10.1080/08351813.2019.1657275

Lindholm, C., Stevanovic, M., Valkeapää, T., and Weiste, E. (2020). “Writing: A Versatile Resource in the Treatment of the Clients' Proposals,” in Joint Decision Making in Mental Health: An Interactional Approach. Editor C. Lindholm, M. Stevanovic, and E Weiste (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan), 187–210. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-43531-8_8

Linell, P. (2005). The Written Language Bias in Linguistics: Its Nature, Origin and Transformations. London: Routledge.

Mondada, L., and Sorjonen, M.-L. (2021). “OKAY in Closings and Transitions,” in OKAY across Languages: Toward a Comparative Approach to its Use in Talk-In-Interaction. Editors E. Betz, A. Deppermann, L. Mondada, and M.-L. Sorjonen (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 93–127.

Mondada, L. (2006). “Video Recording as the Reflexive Preservation and Configuration of Phenomenal Features for Analysis,” in Video Analysis. Editors H. Knoblauch, J. Raab, H.-G. Soeffner, and B. Schnettler (Lang: Bern), 51–68.

Mondada, L. (2011). The Interactional Production of Multiple Spatialities within a Participatory Democracy Meeting. Social Semiotics 21, 289–316. doi:10.1080/10350330.2011.548650

Mondada, L. (2014a). Instructions in the Operating Room: How the Surgeon Directs Their Assistant's Hands. Discourse Stud. 16 (2), 131–161. doi:10.1177/1461445613515325

Mondada, L. (2014b). The Local Constitution of Multimodal Resources for Social Interaction. J. Pragmatics 65, 137–156. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004

Mondada, L. (2014c). “The Temporal Orders of Multiactivity,” in Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond Multitasking. Editors P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 33–76. doi:10.1075/z.187.02mon

Mondada, L. (2015). “Multimodal Completions,” in Temporality in Interaction. Editors A. Deppermann, and S. Günthner (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 267–308. doi:10.1075/slsi.27.09mon

Nishizaka, A. (2016). Syntactical Constructions and Tactile Orientations: Procedural Utterances and Procedures in Massage Therapy. J. Pragmatics 98, 18–35. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.04.004

Pekarek Doehler, S. (2019). At the Interface of Grammar and the Body: Chais Pas (“dunno”) as a Resource for Dealing with Lack of Recipient Response. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 52 (4), 365–387. doi:10.1080/08351813.2019.1657276

Pomerantz, A., and Denvir, P. (2007). “Enacting the Institutional Role of Chairperson in Upper Management Meetings: the Interactional Realization of Provisional Authority,” in Interacting and Organizing: Analyses of a Management Meeting. Editor C. Francois (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 31–51.

Pomerantz, A. (1984). “Agreeing and Disagreeing with Assessments: Some Features of Preferred/dispreferred Turn Shapes,” in Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Editors J. M. Atkinson, and J. Heritage (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 57–101.

Rae, J. (2001). Organizing Participation in Interaction: Doing Participation Framework. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 34 (2), 253–278. doi:10.1207/S15327973RLSI34-2_4

Raevaara, L. (1989). “No – Vuoronalkuinen Partikkeli [No – Turn-Initial Particle],” in Suomalaisen Keskustelun Keinoja I [Practices of Finnish Conversation]. Editor A. Hakulinen (Helsinki: Department of Finnish, University of Helsinki), 147–161.

Rauniomaa, M., and Keisanen, T. (2012). Two Multimodal Formats for Responding to Requests. J. Pragmatics 44 (6–7), 829–842. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2012.03.003

Rauniomaa, M. (2007). “Stance Markers in Spoken Finnish:Minun Mielestäandminustain Assessments,” in Stancetaking in Discourse: Subjectivity, Evaluation, Interaction. Editor R. Englebretson (Amsterdam, NL: Benjamins), 221–252. doi:10.1075/pbns.164.09rau

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511791208

Seuren, L. M. (2018). Assessing Answers: Action Ascription in Third Position. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 51 (1), 33–51. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413890

Siitonen, P., and Wahlberg, K.-E. (2015). Finnish Particles Mm, Jaa and Joo as Responses to a Proposal in Negotiation Activity. J. Pragmatics 75, 73–88. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2014.11.001

Sorjonen, M.‐L. (2001). Responding in Conversation: A Study of Response Particles in Finnish. Amsterdam: Benjamins

Stevanovic, M., and Kuusisto, A. (2019). Teacher Directives in Children's Musical Instrument Instruction: Activity Context, Student Cooperation, and Institutional Priority. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 63 (7), 1022–1040. doi:10.1080/00313831.2018.1476405

Stevanovic, M., and Monzoni, C. (2016). On the Hierarchy of Interactional Resources: Embodied and Verbal Behavior in the Management of Joint Activities with Material Objects. J. Pragmatics 103, 15–32. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.07.004

Stevanovic, M., and Peräkylä, A. (2012). Deontic Authority in Interaction: The Right to Announce, Propose, and Decide. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 45, 297–321. doi:10.1080/08351813.2012.699260

Stevanovic, M., and Peräkylä, A. (2014). Three Orders in the Organization of Human Action: On the Interface between Knowledge, Power, and Emotion in Interaction and Social Relations. Lang. Soc. 43 (2), 185–207. doi:10.1017/S0047404514000037

Stevanovic, M., and Peräkylä, A. (2015). Experience Sharing, Emotional Reciprocity, and Turn-Taking. Front. Psychol. 6 (450). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00450

Stevanovic, M., Himberg, T., Niinisalo, M., Kahri, M., Peräkylä, A., Sams, M., et al. (2017). Sequentiality, Mutual Visibility, and Behavioral Matching: Body Sway and Pitch Register during Joint Decision Making. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 50 (1), 33–53. doi:10.1080/08351813.2017.1262130

Stevanovic, M., Valkeapää, T., Weiste, E., and Lindholm, C. (2020). Joint Decision Making in a Mental Health Rehabilitation Community: the Impact of Support Workers' Proposal Design on Client Responsiveness. Counselling Psychol. Q., 1–26. doi:10.1080/09515070.2020.1762166

Stevanovic, M. (2012a). Establishing Joint Decisions in a Dyad. Discourse Stud. 14 (6), 779–803. doi:10.1177/1461445612456654

Stevanovic, M. (2012b). Prosodic Salience and the Emergence of New Decisions: On Approving Responses to Proposals in Finnish Workplace Interaction. J. Pragmatics 44 (6-7), 843–862. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2012.03.007

Stevanovic, M. (2013a). Constructing a Proposal as a Thought. Prag 23 (3), 519–544. doi:10.1075/prag.23.3.07ste

Stevanovic, M. (2013b). Deontic Rights in Interaction: A Conversation Analytic Study on Authority and Cooperation, Ph.D. dissertation. 10. Helsinki: Publications of the Department of Social Research 2013University of Helsinki.

Stevanovic, M. (2015). Displays of Uncertainty and Proximal Deontic Claims: The Case of Proposal Sequences. J. Pragmatics 78, 84–97. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2014.12.002

Stevanovic, M. (2017). “Chapter 12. Managing Compliance in Violin Instruction,” in Imperative Turns at Talk: The Design of Directives in Action. Studies in Language and Social Interaction. Editors M.-L. Sorjonen, L. Raevaara, and E. Couper-Kuhlen (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 30, 357–380. doi:10.1075/slsi.30.12ste

Stevanovic, M. (2018). Social Deontics: A Nano-Level Approach to Human Power Play. J. Theor. Soc Behav 48 (3), 369–389. doi:10.1111/jtsb.12175

Stevanovic, M. (2020). “Chapter 5. Mobilizing Student Compliance,” in Mobilizing Others: Grammar and Lexis within Larger Activities. Editors E M. Betz, C Taleghani-Nikazm, S. Peter, and Golato (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 115–145. doi:10.1075/slsi.33.05ste

Stivers, T., and Sidnell, J. (2005). Introduction: Multimodal Interaction. Semiotica 2005, 1–20. doi:10.1515/semi.2005.2005.156.1

Stivers, T. (2005). Parent Resistance to Physicians' Treatment Recommendations: One Resource for Initiating a Negotiation of the Treatment Decision. Health Commun. 18 (1), 41–74. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc1801_3

Streeck, J., Goodwin, C., and LeBaron, C. (2011). Embodied Interaction: Language and Body in the Material World. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Tainio, L. (1996). “Kannanotoista Arkikeskustelussa [On Assessments in Everyday Conversation],” in Kieli 10: Suomalaisen Keskustelun Keinoja II [Resources Of Finnish Conversation II], 81–108. Editor A. Hakulinen (Helsinki: University of Helsinki, Department of Finnish).

Tysoe, M. (1984). Social Cues and the Negotiation Process*. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 23 (1), 61–67. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1984.tb00609.x

Vepsäläinen, H. (2019). Suomen No-partikkeli Ja Kysymyksiin Vastaaminen Keskustelussa [The Finnish Particle No and Answering Questions]. PhD Dissertation. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

Keywords: multimodal action packages, joint decision-making, conversation analysis, proposals, body movements, participation, agency

Citation: Stevanovic M (2021) Three Multimodal Action Packages in Responses to Proposals During Joint Decision-Making: The Embodied Delivery of Positive Assessments Including the Finnish Particle Ihan “Quite”. Front. Commun. 6:660821. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.660821

Received: 29 January 2021; Accepted: 07 May 2021;

Published: 31 May 2021.

Edited by:

Leelo Keevallik, Linköping University, SwedenReviewed by:

Emma Betz, University of Waterloo, CanadaCopyright © 2021 Stevanovic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melisa Stevanovic, bWVsaXNhLnN0ZXZhbm92aWNAdHVuaS5maQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.