- Department of Design and Communication, University of Southern Denmark, Kolding, Denmark

Using conversation analysis and usage-based linguistics, I focus on a beginning L2 user in an ESL classroom and trace his use of a “family of expressions” which, from the perspective of linguistic theory, are instantiations of either the ditransitive dative construction (e.g., “he told me the story”) or a prepositional dative construction (e.g., “he told the story to me”). The semantics of both constructions denotes transfer of an object, physically or metaphorically, from one agent to another. Therefore, I investigate them as one type of object-transfer construction. The instances of the construction are found predominantly in instruction sequences, and I show how the L2 user co-employs talk and recycled embodied work that elaborates the deictic references of the talk and the relation of agent-object-recipient roles among them. Through my analyses, I will showcase the embodied nature of linguistic categorization (Langacker, 1987) but take the argument further and suggest that the semiotic resource known as “language” is a residual of embodied social sense-making practices (aus der Wieschen and Eskildsen, 2019). The study draws on the MAELC database at Portland State University, a longitudinal audio-visual corpus of American English L2 classroom interaction.

Introduction

This article reports on the dynamics of embodied second language (L2) interaction over time. Using conversation analysis (CA) and usage-based models of language (UBL), I focus on a beginning L2 user in an English as a second language (ESL) classroom and trace his use of a “family of expressions” which, from the perspective of linguistic theory, are instantiations of either the ditransitive dative construction (e.g., “he told me a story”) or a prepositional dative (e.g., “he told the story to me”).

Drawing on a range of previous studies in which we have traced, in the same focal learner as in this article, developmental changes in his deployments of gesture-talk assemblies, encountered and reused multiple times across several years (Eskildsen and Wagner, 2013, 2015, 2018), this article zooms in on how bodily actions serve to highlight aspects of semantics and contribute to action formation (Levinson 2013; Lilja and Piirainen-Marsh, 2019). Through this empirical evidence I home in on what is constitutive of embodied L2 interactional competence. Moreover, I attempt to throw light on linguistic categorization through participants’ visible embodied work. The article thus merges three strands of research: longitudinal conversation analytic L2 research focusing on interactional competence; research on embodied L2 interaction; and usage-based L2 research. In the following, I will outline previous research before moving on to a description of the present study. Then follows the empirical analyses before I end with a Discussion and Conclusion section.

Longitudinal Conversation Analysis-Based and Usage-Based Studies in L2 Research

Grounded in the concept of interactional competence (Kramsch, 1986; Garfinkel, 1967), longitudinal conversation analytic second language acquisition research (CA-SLA) has prolifically traced change across time in people’s methods for accomplishing social action (e.g., Hall et al., 2011; Pekarek Doehler and Pochon-Berger, 2015; Pekarek Doehler and Berger, 2018; König, 2020). Relatedly, a more linguistically-semiotically oriented research branch has traced changes in the interactional use of particular linguistic items over time (Ishida, 2009; Kim, 2009; Eskildsen, 2011; Masuda, 2011; Hauser, 2013; Pekarek Doehler and Balaman, 2021). Neighbouring this CA-based L2 research, L2 research drawing on usage-based models of language has investigated L2 constructional development as an exemplar-based and usage-driven process in both qualitative case studies and quantitative corpus-based studies (Eskildsen and Cadierno, 2007; Ellis and Ferreira-Junior, 2009; Eskildsen inter alia 2009, 2012, 2015, 2020a, b; Roehr-Brackin, 2014; Tode and Sakai, 2016; Römer and Berger, 2019; Horbowicz and Nordanger, 2022). Common to the linguistically-semiotically interested CA-based research and the usage-based research is the finding that linguistic patterns grow out of recurring exemplars in experience as resources-for-social-action (Pekarek Doehler, 2018; Eskildsen, 2018; Eskildsen and Kasper, 2019).

Usage-based SLA has documented the bottom-up, exemplar-based nature of learning in the form of e.g., verb-argument constructions (Ellis and Ferreira-Junior, 2009; Römer and Berger, 2019), object transfer constructions (Year and Gordon, 2009), can-constructions (Eskildsen, 2009), auxiliary do-constructions (Eskildsen, 2011); negation constructions (Eskildsen and Cadierno, 2007; Eskildsen 2012), motion constructions (Li et al., 2014; Eskildsen et al., 2015), relative clauses (Mellow, 2006), question formation (Eskildsen, 2015), French c’est and Swedish det är constructions (Bartning and Hammarberg, 2007), German gehen and fahren (Roehr-Brackin, 2014), L2 Finnish evaluative constructions (Lesonen et al., 2020a), and epistemic verb constructions in L2 Norwegian (Horbowicz and Nordanger, 2022). In the longitudinal work, the research focuses on the extent to which L2 construction learning is exemplar-based, i.e., moving along a trajectory from specific instances to increased productivity and schematicity within single constructions. However, research is also appearing that tackles the larger issue of how entire linguistic inventories are built out of recurring usage-patterns (Eskildsen 2014, Eskildsen 2017, Eskildsen, 2020a, Eskildsen, 2020b; Tode and Sakai, 2016). One finding that is consistently emerging from the growing body of usage-based research is that the exemplar-based trajectory is not necessarily a path from “one to many” but can also be from “a few to more” in a process where constructions that are partially specific and partially schematic (for example, “Are you + ADJECTIVE?” in L2 English question formation) play an essential role across phases in development (Eskildsen, 2015, Eskildsen 2017, Eskildsen 2020a; Lesonen et al., 2018, Lesonen et al., 2020a, Lesonen et al., 2020b; Horbowicz and Nordanger, 2022). However, recent research is showing that a usage-based trajectory may also be a matter of routinisation (Eskildsen, 2020a; Pekarek Doehler and Balaman, 2021).

Typical of usage-based case-studies, I take as my starting point for the empirical exploration a specific linguistic phenomenon. As pointed out in the Introduction, I refer to the phenomenon as a “family of expressions” whose common denominator, semantically, is that all instantiations denote transfer of an object, physically or metaphorically, from an agent to a recipient. In terms of linguistic theory, the instantiations are either ditransitive datives or prepositional datives (see e.g., Campbell & Tomasello, 2001). Ditransitivity concerns the presence in the syntactic structure of both a direct and an indirect object (e.g., “he told me a story”), whereas the prepositional dative is constructed by the use of a preposition (e.g., “the told the story to me”). There is quite some debate, going back at least to Halliday (1970), over the extent to which the two syntagmatic options are semantically and pragmatically equivalent (e.g., Thompson, 1988; Goldberg, 2003; Bresnan et al., 2007). This debate is of a larger scope than the present case-study in that it also involves other construction types (e.g., with the preposition “for”, as in “she bought a book for him”) and sometimes brings in invented examples and introspective methods. My study cannot definitively settle this argument because it is based on a limited number of examples, but my data do indicate that there at least can be object transfer involved in both ditransitive and prepositional datives. Therefore, I investigate the “family of expressions” as instantiations of what I will refer to as the object-transfer construction. As I will show, the core semantic property of object transfer is reflected in speakers’ embodied conduct, irrespective of syntactic type. Before coming to that, however, a note on gesture and L2 learning is in order.

Gesture and L2 Learning

SLA’s historical heritage as a cognitive or psychological field (e.g., Doughty and Long, 2003) has also been visible in the research on embodied actions which in SLA have primarily been understood as hand gestures that reflect underlying thought processes and are co-employed alongside speech, cf. the work of McNeill (1985, 1992) and Kendon (1986, 2004). The narrow focus on manual gestures has allowed for precise operationalizations of aspects of the gesturing and the formulation of specific research questions. Accordingly, studies of gestures in L2 interaction have primarily been experimental and have attempted to identify gestural features that indicate psycholinguistic processes, i.e. gestures are treated as visible renditions of thought processes (Gullberg, 2010). A specific interest in this research is the use of gestures in resolving communicative problems as L2 speakers have been found to gesture more than L1 speakers, especially in moments of production trouble (Graziano and Gullberg, 2019). Gullberg (2011) discusses how different types of gestures work to solve different kinds of problems; iconic gestures are typically invoked to solve lexical trouble, whereas trouble related to, for example, deixis and co-referencing–trouble that may accrue over several turns at talk–is typically solved by means of gestures that point out or embody the pointed-to or talked-about objects and places in physical space. Both kinds of repair work are co-constructed and dependent on repetitions of both speech and gestures. Gullberg further distinguishes interactional gestures that are typically deployed to indicate that the speaker is “doing thinking” (Houtkoop-Stenstra, 1994; quoted in Brouwer, 2003, p. 538) while keeping the floor.

While refraining from asserting a priori categorizations, microanalytic research–with which this paper finds kinship–has investigated gesture and other embodied behavior, for example, gaze and the handling of objects, as resources upon which participants draw in L2 interactions to perform a variety of actions, such as completing turns-at-talk (Olsher, 2004; Mori and Hayashi 2006), establishing recipiency (Mortensen, 2009), opening and closing sequences, displaying ongoing understanding (Eskildsen and Wagner, 2013, Eskildsen and Wagner, 2015), displaying willingness to participate (Evnitskaya and Berger, 2017); doing repair (Seo and Koshik, 2010; Lilja, 2014), instructing (Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018), explaining (Jakonen and Morton, 2015; Kääntä et al., 2018), and ascribing action (Lilja and Piirainen-Marsh, 2019).

The Present Study

This article builds on previous work (Eskildsen and Wagner 2013, Eskildsen and Wagner, 2015, Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018; aus der Wieschen and Eskildsen, 2019), in which we have traced the interplay between certain linguistic-semiotic resources and embodied action over time. We demonstrated that specific gestures are coupled with specific linguistic items in situations where new vocabulary items are used for the first time. Our findings suggest that linguistic constructions are deeply embodied, and changes in the use of specific kinds of gesture-word configurations over time are related to both interactional specifics in-situ and the more general learning process.

Combining usage-based and conversation analytic SLA, this article focuses on three aspects that have transpired as central to understanding L2 learning but which have not been investigated together before: 1) the coupling of specific linguistic material with specific embodied work in L2 interaction; 2) the exemplar-based nature of L2 construction use; 3) the actions accomplished through the use of a specific construction (here, the object-transfer construction). In addition, I will use my data as the empirical backdrop for a discussion of the embodied nature of linguistic categorization (Langacker, 1987). As such, the article sheds new light on the intricate relationship between embodied conduct and L2 interactional competence in situ and over time.

My phenomenon–the object-transfer construction and the embodied conduct with which it is coupled–is found through observation and discovery rather than being hypothesis-driven. It is a primarily interactional phenomenon, i.e., used and learned as part of collaborative sense-making practices. The common denominator among the instances is the collage that consists of embodied parts and spoken parts, but the embodied parts and the spoken parts themselves cannot be foreseen, they can only be discovered, “only actually found out, and just in any actual case” (Garfinkel, 2002: 98). This implies that the instances of the object-transfer gesture must each be described as if they were novel–but it is in the similarities that emerge from each example that the phenomenon is established as one: an embodied object-transfer construction.

Data

The data source for the present study is the Multimedia Adult English Learner Corpus (Reder, 2005), which consists of audio-visual recordings of classroom interaction in a United States English as a second language (ESL) context. The classrooms in which the recordings were made were equipped with video cameras and students were given wireless microphones on a rotational basis; the teacher also wore a microphone. The data for the present research come from Carlos (pseudonym), an adult Mexican Spanish-speaking learner of English. Carlos had been in the United States for 21 months prior to joining this ESL program, and he progressed successfully through the four levels (A-D), from beginner (SPL 0–2) to high intermediate (SPL 4–6; Reder, 2005), assigned to the classes by Portland Community College (PCC), over the course of 4 years. Table 1 displays Carlos’ time in class schematically. The gaps between periods indicate that he did not attend classes in those periods (due to work etc.).

Establishing the Phenomenon

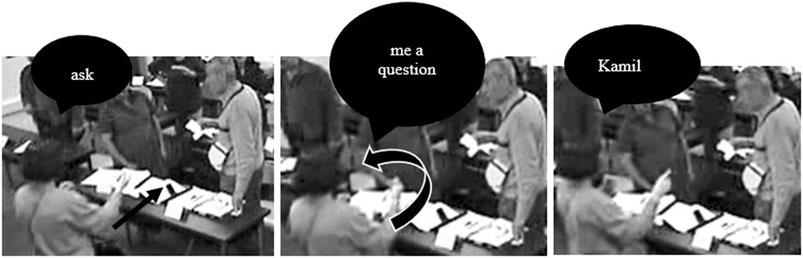

Although the focus here is on Carlos, I will start this section by showing an example of what I will refer to as the embodied object-transfer construction produced by another speaker, namely the teacher. Prior to the example, the teacher has instructed the students to ask each other questions and answer them using the short formats yes I am/no I’m not and yes I do/no I don’t. In addition, she also instructed them to correct each other if they use the wrong answer format (e.g. answering with a form of the copula (be) to a question format using do, as in “Do you like … ?/yes I am”). As the last part of her instructions, she now intends to illustrate with a student, Kamil, how it is done, so she needs Kamil to ask her a question. Her instruction to Kamil, exemplifying the phenomenon in this paper, is transcribed in Extract 11. The teacher instructs Kamil, saying “ask me a question Kamil”, followed by a meta-comment directed at the entire class, indicating that this is the last time she will exemplify the exercise (line 1).

Following a self-repair (the broken-off “I” and the “okay”), she repeats the instruction, this time saying, “ask me the question” (line 2). The linguistic format is the imperative version of the object-transfer construction and, as will be shown, the teacher’s embodied work is similar to that which Carlos draws on in his productions of the same and related constructions. I am not inferring that Carlos, although he is a ratifed co-participant here, picks it up from the teacher on this occasion; rather, the teacher’s embodied work here will serve as descriptive backdrop against which I will investigate Carlos’ uses. Moreover, the example in Extract 1 also serves to illustrate that Carlos’ embodied practices are not idiosyncratic; other people, here exemplified by the teacher, do similar things as well.

The teacher’s gesturing is a deictic-dynamic ensemble consisting of several key components: pointing to referents (corresponding to participants in the interaction and in the linguistic construction) and conveying the transfer of some object, tangible or abstract, between the participants. The first pointing gesture begins before the onset of the verbal instruction, suggesting that it functions as an embodied summons of the recipient, Kamil. While pointing towards Kamil, the teacher begins the verbal instruction, ask. She then flips the wrist toward herself while producing the next part of the verbal instruction, me a question. Towards the end of her first instruction, she makes a meta-comment and extends her index finger and points up in the air. This gesture seems to be working as an attention-getting device to all the students. After a self-repair during which she flips her wrist and flexes her index finger toward herself, she produces her second instruction in a way that is similar to the first: she points to the instructee (Kamil) and flips the wrist toward herself before retracting her arm to her torso. In both instruction instances, I argue, the teacher’s flips of the wrist indicate movement that is reflective of the object transfer–the asking of the question “from Kamil to herself”. The flips are performed in a timely fashion so as to cooccur with the verbal material signifying object transfer (“ask”), and the deictic gestures cooccur with the syntactic placement of the pointed-out participants: before the construction (because the doer is not verbalized in the imperative but here gestured into being instead) and around the production of “me” (Figures 1,2).

The crucial point is that the embodied work referred to here as “the object-transfer gesture” consists of pointing gestures and a gesture indicating movement. While it is thus the gestural ensemble that makes up the phenomenon, the embodied work can be teased apart into components. First, pointing gestures have several recognizable forms and have been investigated extensively (see e.g., Cochet and Vauclair, 2014; Mondada, 2014) and it is beyond the scope of this article to convey this research exhaustively. Two findings, however, are interesting for the present purposes: index-finger pointing has been found, among other things, to function as imperative (Cochet and Vauclair, 2014), and thumb-pointing is often found when precision in the pointing is not required (Wilkins, 2003). The part of the object-transfer gesture that indicates movement is arguably more elusive in terms of form but in both the teacher’s action (Extract 1) and in the examples we will see from Carlos’ data, the movement is indicated by a range of hand movements, e.g., wrist-flipping, that are contingent upon the participants’ locations and positions in the specific situations. In previous research, a related phenomenon has been investigated. This research has established the ubiquitous nature of the palm-up open hand (PUOH) gesture (e.g., Müller, 2004; Streeck, 2009; Cooperrider et al., 2018), a central use of which is found in contexts where (talk about) giving and receiving objects is relevant. It is argued in this research that this use is made possible because the palm works as a surface upon which an object to be given or received can be placed, metaphorically speaking (cf. McNeill, 1985). The actual process of giving or receiving is implied rather than conveyed in the gesture and can be part of a range of actions, for example, a presentation or inspection of an object or a request for an object.

In the present study, I do not focus on a specific type of hand gesture but rather trace an interplay of specific linguistic and bodily resources that have been found empirically to cooccur, in situ and over time. The linguistic and bodily resources combine into an embodied object-transfer construction. In Eskildsen and Wagner (2018) we traced Carlos’ development of embodied assemblies involving the verbs ask, say, and tell over a period of two-and-a-half years. We documented how these embodied assemblies were put to use predominantly in instruction environments and indexed targets and accomplished reference in the environment and indicated transfer of something going from A to B, typically as a flip or bend of the wrist–akin to what the teacher was shown to do in Extract 1. In our data (Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018), the participants were thus found to make sense of the relation between the targets indexed by the embodied work as an “A to B″ relation, not an “A + B″ relation. In all our instances, and in congruence with the linguistic format, the first appointed target was the “actor” and the second one “the receiver”, again similar to what the teacher was found to do in Extract 1. The embodied ensemble, in other words, “is a flexibly employed embodied construction that is fitted to local configurations and understood in situ as doing referencing to two co-participants and indicating an actional relation between them.” (Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018: 158).

By “flexibly employed” we also indicated that the coupling between the linguistic construction and the embodied conduct is not a permanently fixed gestalt; in fact, we showed that early in development, Carlos was more reliant on embodied conduct than in later instances, implying that the linguistic and the bodily parts need not be co-produced. We also found a tendency for Carlos to use the object-transfer gesture in instruction sequences. In this paper, I shift the primary analytic focus from the role of the embodied conduct in the achievement of the instruction to its role in forming the backbone of the object-transfer construction. I will show three examples that illustrate how Carlos employed the embodied object-transfer construction in instruction sequences, using the verbs “tell”, “ask”, and “say”. I then move one to analyze examples with “give”, the prototypical object-transfer verb, before showing a possibly deviant case with “show”.2 The analytic interest throughout is on the relationship between the verbal production and the specifics of the embodied conduct, and the primary aim is to get closer to an understanding of the relationship between embodiment and the semantics of the object-transfer construction, while a secondary aim is to understand the relationship between the semantics and the actions that Carlos accomplishes when using the embodied object-transfer construction.

The Embodied Object-Transfer Construction in Carlos’ Data3

Tell, say, ask

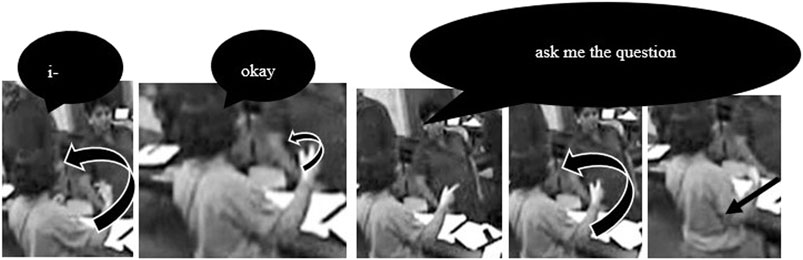

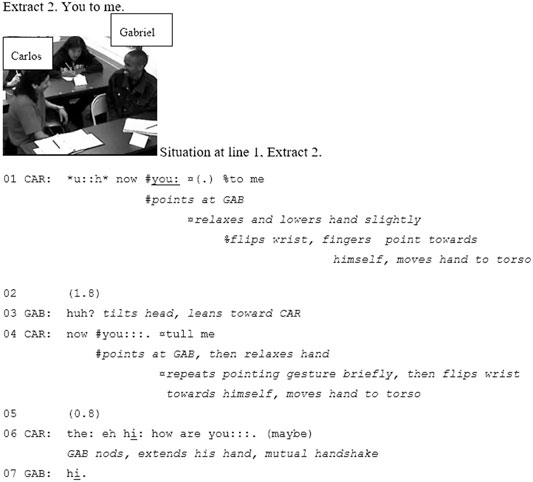

The first example of the construction in Carlos’ data (Extract 2) comes from his first day in class. Prior to the extract, the students have been instructed to introduce themselves to the person sitting next to them, using the format hi my name is _____ and nice to meet you. Carlos and his partner, Gabriel, have just done the exercise, initiated by Carlos, and after a lengthy pause during which the two students are looking around the classroom, Carlos self-selects to initiate the next activity (Extract 2, line 1).

His turn (line 1), now you to me (simplified) is a complex embodied ensemble in which deictic and dynamic gestures are coordinated with the talk. First is a deictic gesture, Carlos pointing at Gabriel, coinciding with the production of you. Then, following a micropause during which he abandons the deictic gesture, he makes a transition into the next bodily action at the onset of to, namely the flipping of his wrist as he makes a deictic-dynamic gesture toward himself that he finishes just before touching his own torso which coincides with the production of me.

Carlos’ turn is coordinated tightly with hand gestures. Now you:, with the lengthened vowel projecting more to come, is concurrent with a pointing gesture. Following a micro-pause, to me is produced alongside a movement in Carlos’ pointing from Gabriel to himself. The semantics of the construction–the object-transfer meaning component–is visible in the gesture because it is not a two-part deictic gesture in which Carlos first points at Gabriel and then at himself, but a smooth motioning from Gabriel to Carlos indicating transportation of something (Figure 3).

Next (lines 2–3), following a lengthy pause, Gabriel does an embodied open repair initiation (Seo and Koshik, 2010; Mortensen, 2016). Carlos’ next action (line 4) is a repair, a slightly modified version of his previous turn. What was audibly recognizable as the preposition to in line 1, in the repaired version in line four sounds like an attempt at the verb tell, as captured in the phonetic approximation tull. Throughout his turn, Carlos performs a set of embodied actions that are similar but not identical to what he did in line 1. This time, he restarts the pointing at the uttering of tull before doing the motioning from Gabriel to himself (Figure 4). Gabriel does not immediately respond to this turn either and Carlos continues in line 6 with what resembles an increment (Schegloff, 1996) to his previous turn, assuming that Carlos was in fact attempting “tell” (i.e., “tell me the hi, how are you (maybe)”). It transpires from Gabriel’s response (line 7) and the ensuing interaction (left out here in the interest of space) that he understands this as an invitation to do the introduction sequence one more time.

A closer look at the deictic-dynamic gestures employed by Carlos reveals the similarities between Carlos’ actions–the pointing gestures and the motioning toward himself are almost identical. In the repaired version, however, Carlos restarts his pointing at Gabriel at the onset of “tull”. This makes the object-transfer meaning component more salient because it highlights the sender of the transfer (Gabriel), but it also enhances the function of his action as he is instructing Gabriel to do the next action. Importantly, Carlos is not just repeating something, verbally and gesturally, he is repairing his turn linguistically and bodily. He is, in other words, re-designing his entire embodied action. The embodied components of Carlos’ action described here constitute the object-transfer gesture and the entire utterance You tull me the hi how are you (simplified) is, in grammatical terms, a double-object construction. Together, they combine into an embodied object-transfer construction. Note also that Carlos is pointing with his index finger which may further underline the instructional nature of his action as this is a form of pointing that has been shown to be used in imperative environments (Cochet and Vauclair, 2014).

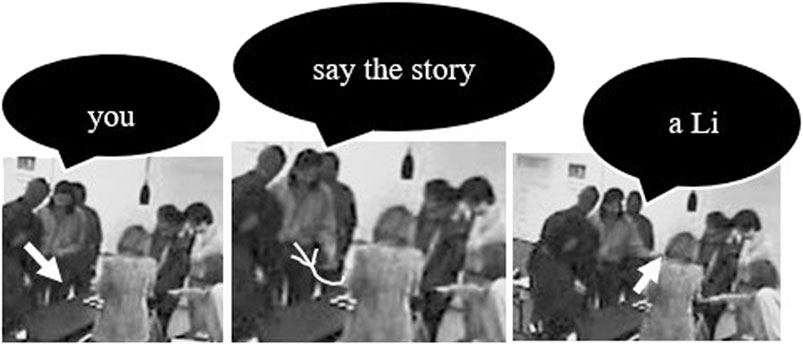

The next extract (3) is an example with the verb “say”. The students have been putting together a story based on small illustrated paper clippings in a task that they began during the prior session. The paper clippings–the white dots in the pictures–are now placed on a desk so as to display the storyline. Just before the extract, the teacher has instructed Li to ask Mariela to tell her (Li) the story because she (Li) was not present when they began the task. Mariela does not comply with the teacher’s instruction, and in line 1, Carlos explains to Mariela what she must do. Note that Mariela stands behind Gabriel.

Carlos’ turn, you say the story (.) a:: Li, is temporally aligned with his embodied actions: he makes two distinct gestures, one deictic-dynamic gesture going from Mariela to Li (aligned with you say the story), and one pointing gesture toward Li (aligned with a Li) (Figure 5). Mariela makes an open-class repair initiation (line 2) and Carlos does a repair of his utterance (line 4). His repaired version is delivered fluently (i.e., there is no micropause or vowel lengthening as in line 1) and he seems to also revise his gesture: going from Mariela via the story as represented by the paper clippings to Li, the gesture is now one fluent movement that more clearly marks out the positions in space of Mariela, the story, and Li (see also Figure 6), thus enhancing the semantics of the transfer of the story from Mariela to Li. The teacher confirms Carlos’ instruction (line 6) and points out the story and the instructed teller and recipient in space.

In both cases, Carlos’ embodied work points out actor, recipient, and trajectory of the action as well as the object to be transported, as represented by the paper clippings on the desk. But in the redesign of the action, the object-transfer trajectory is enhanced, and the gesture is done as one movement. The three arrows in Figure 6 represent the trajectory of Carlos’ gesturing: from Mariela downward and toward the story as represented by the paper clippings and from the story upward and toward Li. Figure 7 captures the entire movement in one frame grab.4

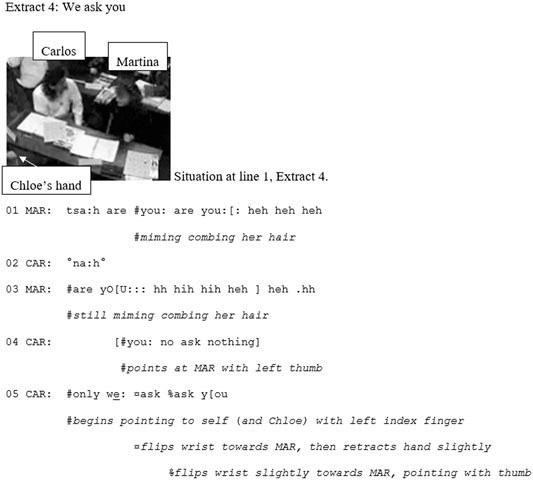

In the next example, recorded 3½ months later, the students are doing group work. The task is about miming and guessing actions; one person mimes an action and the two other people must guess. They have been instructed to use the question format “are you X-ing?” when trying to guess what the mimer is doing. Carlos is working with Martina and Chloe. Carlos and Martina share a desk, while Chloe is sitting at another desk to Carlos’ right and does not say anything in the extract (4) (Transcription on next page). In line 1, Martina mimes combing her hair while at the same time using the question format that the students were instructed to use prior to the task.

Carlos then begins expressing disagreement with how Martina is carrying out the task, claiming that she is not supposed to ask questions (simplified, no, you no ask nothing; lines 2–4). Throughout the turn in line 4 he is pointing at Martina, the deixis elaborating not only the person talked to and talked about, but also that person’s accountability of the previous action. Carlos’ instruction is in overlap with Martina’s continued work to do the task (line 3), but once out of the overlap Carlos elaborates on the instruction: only he and Chloe are supposed to ask Martina questions (line 5). The students then agree that Martina’s miming was “combing” before finally negotiating who does the miming and who does the guessing (not shown).

The point of interest is line five in which Carlos is using the object-transfer construction. Linguistically it is different from the previous instances in that the object to be transferred–here the question–is not verbalized; Carlos only says “we ask you” which is a syntactically, semantically, and pragmatically complete construction. Carlos’ bodily actions resemble those of previous cases: he points from the sender (“we”) to the recipient (“you”) of the object to be transferred (“the question”). The pointing toward himself is done with the left index finger but because of the camera angle, it is difficult to ascertain whether he is only pointing at his own torso or is including Chloe in the deictic field of gesture.5 The dynamic of the gesture is visible in the flipping of the wrist towards Martina coinciding with the progression of the talk (“we ask”): Carlos does not stop pointing at himself to restart a new deictic gesture toward Martina; rather, he is motioning from himself toward Martina with the flip of the wrist, while still pointing with the index finger. Between the two occurrences of “ask” in Carlos’ talk, he abandons the motioning from himself to Martina and relaxes his index finger. At the onset of the second “ask”, he then produces another flip of the wrist, this time with his thumb in a pointing position toward Martina (Figure 8). That his motioning gestures toward Martina coincide with “we ask” and “ask”, respectively, rather than “you” suggests that they do not primarily elaborate an entity in space. Instead, they seem to elaborate the trajectorial nature of the object-transfer construction. The embodied work elaborates the relevant points in space in concert with the trajectory of the object being transported, but precision in the actual pointing is not highlighted.

Summary: Tell, Say, Ask

We have seen three uses of the embodied, object-transfer construction that conveys the meaning of something being translocated to somebody by somebody. The words and the gesture work to index, in a locally adapted fashion, the what, wheres, and whos of the situated construction. The deictically fashioned gestures index the actor and the recipient of the action, and the dynamically fashioned gesture indexes the trajectory of the action from actor to recipient. The semantics of the construction and hence its “grammar” is therefore very concretely embodied, i.e., visible in the bodily conduct. Moreover, in the beginning, Carlos is using the object-transfer construction without the standard linguistic items to do so (i.e., “you to/tull me” and “say the story a Li” are both non-standard) and the gesturing seems to play a vital role, communicatively, in these early examples (see also Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018). Therefore, Carlos’ bodily actions are not only a matter of showing semantics; they are also instances of accountable behavior in terms of action formation and action ascription (Lilja and Piirainen-Marsh, 2019). That is, it is through the entire embodied construction that Carlos performs a social action that is recognized and understood by the co-participants, and it is this recognition and understanding that occasions the next relevant action.

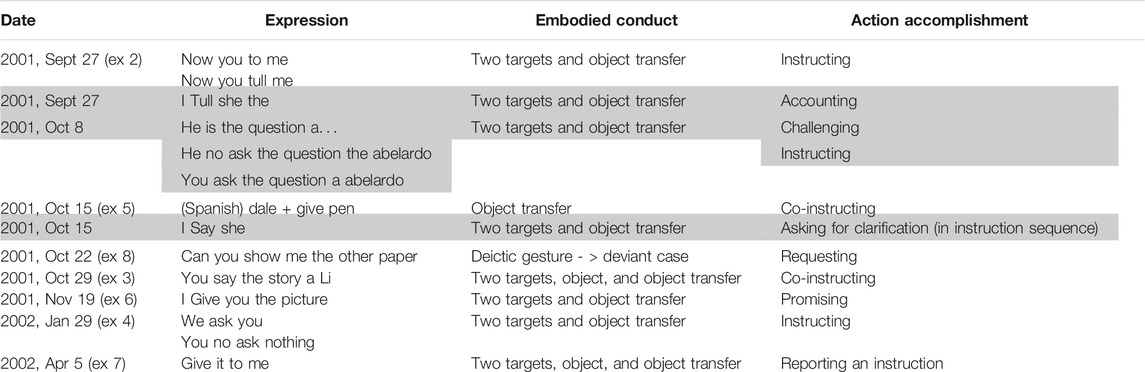

Table 2 shows all examples from Carlos’ first term in class and the examples analyzed in extracts 4 and 7, which come from his second term in class. The ones marked in grey (see Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018) were produced as locally crafted embodied ensembles in a manner that resembles the examples analyzed here. As the table shows, Carlos predominantly used the construction with the verbs “ask” or “say” or with non-standard items in such constructions, i.e., the “to/tull/tell”-approximation and copula “is”. There is, then, a limited array of verbs available to Carlos for producing these constructions, which suggests that Carlos is drawing on an exemplar-based set of expressions. Another point is that the constructions are non-standard and/or incomplete, syntactically. For example, people usually do not “say” stories, they “tell” them, and they typically do not ask questions “a” someone, but “to” someone (or they “ask them questions”). The verbs “show” and, perhaps, especially “give”, on the other hand, are used in a manner that corresponds to standard syntactic patterns (“can you show me”, “I give you the picture”, “give it to me”). Going beyond the data presented here, it seems that the standard use of “to” in the instantiations with “give” spills over to uses of other verbs over time (e.g., Carlos has a later use of “say”, “I say to him yes … ”, that corresponds to standard syntax) (cf. Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018, p. 148).

The data also indicate that the object-transfer construction itself carries meaning (Taylor, 1998). In Carlos’ case, this is perhaps so because it also exists as a semantic unit in Spanish. Something extralinguistic, perhaps conceptual, allows him, in combination with a complex of bodily work, to accomplish actions that are not straightforwardly or standardly accomplished by way of the linguistic structures alone. From the perspective of cognitive linguistics, it is a conceptual category, or schema, that Carlos draws on to produce the object-transfer construction. The co-participants, however, do not have access to Carlos’ conceptual categories so he needs to make them publicly available through embodied actions. This shows, in a very concrete and salient way, the fundamentally embodied nature of human linguistic categorization pointed out from a theoretical perspective by Langacker (1987): we understand the categories of language, through which we perceive and conceptualize the world, with our bodies. It is important, in this respect, to recall the first extract: the teacher’s embodied actions indicate that the bodily performance of the object-transfer is not Carlos’ prerogative but may be a more fundamentally human feat.

Interestingly, the uses shown here (and many of the ones analyzed in Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018) are found in instruction sequences; that is, especially early in development, Carlos is predominantly using the embodied object-transfer construction to accomplish instructions. Similarly, the teacher used the object-transfer construction to instruct Kamil in Extract 1. This indicates that there may be a relationship between the semantics of object-transfer and the pragmatics of giving instructions. If that is the case, the question is whether the act of instructing gives rise to the semantics of object-transfer or vice-versa or whether the relationship is somehow bidirectional. For now, this remains a point of speculation, but if people learn to use language a set of resources to accomplish social action, then there is merit to the idea that actions, such as instruction-giving, spawn semantics, such as the object-transfer construction.6

Give

Prototypically associated with the object-transfer construction, “give” has been found to be important in the learning of the double-object construction in L2 English (Ellis and Ferreira-Junior, 2009). In Carlos’ case, “give” seems to play a role in the emergence of the standard ditransitive dative construction. As can be seen in Table 2, the instantiation “I give you that picture” is the second such construction to occur, preceded only by “can you show me the other paper”. Other previous uses of the object-transfer construction are non-standard. Moreover, the emergence of the proposition “to” in the prepositional dative (instead of the probably Spanish-induced “a”) also seems to be related to “give” as seen in the instantiation “give it to me” which is the first of its kind in Carlos’ data. For these reasons, this section traces Carlos’ uses of “give”.

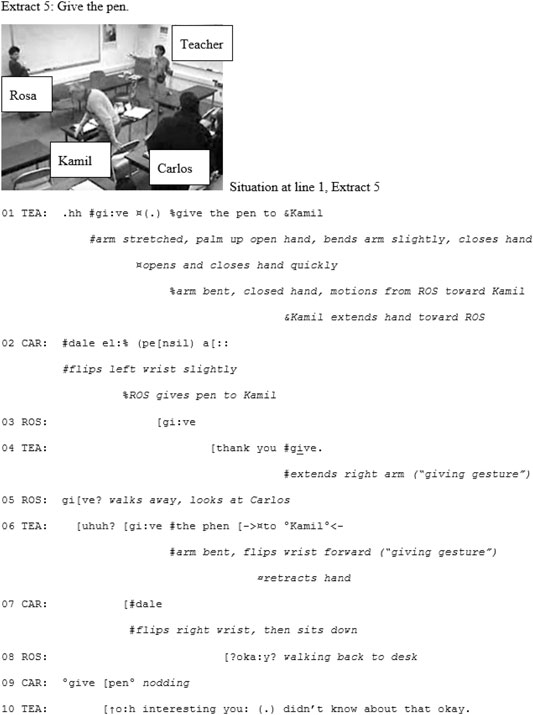

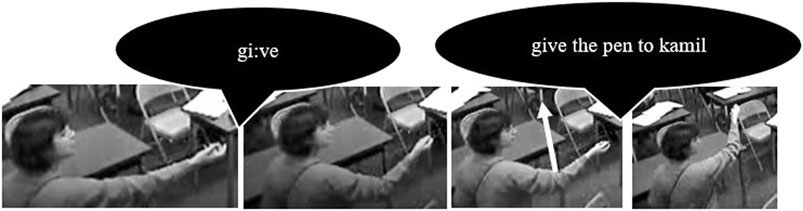

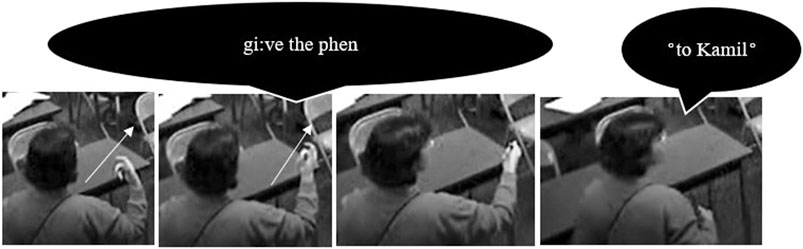

Extract 5 shows Carlos’ first encounter with “give” in the data. Prior to the extract, Rosa was at the whiteboard doing her part of a daily routine of writing the dates of “today, yesterday, and tomorrow” (Eskildsen, 2021). When Rosa was done, the teacher–using both verbal and embodied resources–instructed her to give the pen to another student. Rosa did not comply with the instruction and started go back to her desk when the teacher told her to stay at the whiteboard. Then comes line 1 in the extract, where the teacher repeats her instruction but this time specifying Kamil as the receiver of the pen. Her embodied actions signal both giver and receiver to elaborate what she is saying. The teacher’s gesture coinciding with the first “give” is done with a version of the PUOH gesture, but it seems as if she is doing the gesturing from the perspective of a recipient (the slight retraction of the arm). The focal conduct here, however, is the teacher’s gesture that outlines the trajectory from giver to recipient (Figure 9). It is fitted to the local circumstances of the talk in that the trajectory corresponds to the physical relation between Rosa and Kamil at the time of speaking.

In line 2, Carlos then contributes with a translation of the entire construction into Spanish7 that is accompanied by a slight flip of the wrist which may be indicative of the object-transfer aspect of the meaning of “give” (Figure 10). His turn is aimed at Rosa–neither the teacher nor Kamil speak Spanish–and, overlapping Carlos, Rosa begins giving the pen to Kamil, and utters gi:ve during the action (line 3). Rosa’s action is thus brought about by the teacher’s instruction, Kamil’s extended hand, and Carlos’ translation of “give the pen to” into Spanish (dale el pensil a). The teacher positively acknowledges Rosa’s actions (thank you, line 4)8 and repeats give, seemingly orienting to it as a teachable item as emphasized by her gesture which brings out yet again the meaning of give, as she extends her forearm in a “giving” gesture (Figure 11).

While walking away from the whiteboard, Rosa repeats give with try-marked intonation (line 5) in overlap with which the teacher confirms (uhuh, line 6) and does a post-trouble repeat of the troublesome instruction. This may be intended as a further attempt at teaching the “give"-construction, seeing as she does a revised version of the gesture that accompanied her first repetition of give (Figure 12). However, because of the configuration of the space, Kamil stands between Rosa and the teacher, and Rosa cannot see the teacher as she walks away from the whiteboard. The teacher may be realizing this around the uttering of pen which is overly aspirated, and it may be the reason why the rest of her turn is both a bit rushed and softer than the rest of her speech. Rosa does not establish eye contact with the teacher; instead she looks at Carlos who is standing by his desk in the middle of the room. Carlos’ turn in line 7, dale, accompanied by a movement of the hand that signals object transfer (Figure 13), sits sequentially so as to be a response to Rosa’s try-marked give in line 5. Rosa’s turn in line 8, however, is partially unintelligible due to the overlap with the teacher, so we cannot know for certain how she responds to Carlos, if at all. Rosa sits down again, as does Carlos who also repeats give pen in a soft voice (line 9), and the sequence is closed down by an expression of surprise from the teacher (line 10).

For the present purposes we note that this is the first time in class (as captured on video) Carlos uses give and he does it in the service of helping another Spanish speaking student understand the teacher’s instruction. In line 2, Carlos is offering a multimodal translation of the teacher’s instruction into Spanish and, in line 7, he produces a gesture that indicates object-transfer alongside the single-word translation of “give” into Spanish. Both actions show his own understanding of the instruction given by the teacher and the semantics of give, and they help Rosa overcome a comprehension problem. Finally, I note that the teacher uses bodily resources to highlight the object-transfer meaning of give, which underlines the robustness of the symbolic nature of the entire embodied construction. Adding to the robustness of the finding, the teacher’s embodied work, especially in line 1, is in alignment with previous research showing a locally crafted version of the PUOH gesture used to denote giving and/or receiving (e.g., Müller, 2004; Streeck, 2009; Cooperrider et al., 2018).

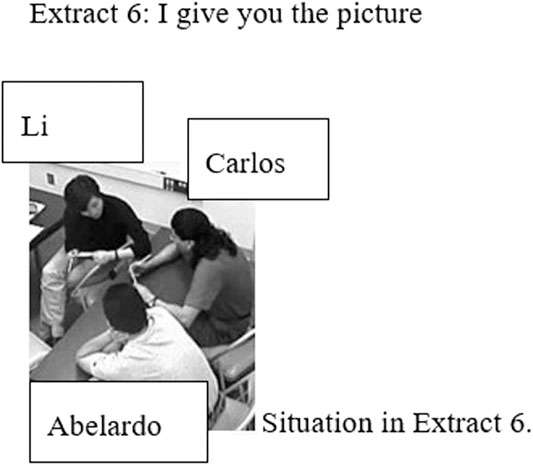

Five weeks later (Extract 6), Carlos, Li and Abelardo just finished their groupwork. Prior to the extract, Li has asked Carlos about a picture. His response is an account for not yet bringing the picture to class and following that account he reassures her that he will give her the picture. This is the turn of interest here. It does not receive a response from Li, so there is no line by line transcription of this example. A screenshot of the situation and the graphic rendition of the talk (Figure 14) suffice. At the time of uttering the promise to give her the picture, Carlos’ hands are in rest position holding a cue card (from the group work). Just before saying “I”, he retracts his hand toward himself. This movement stops at the onset of “give” at which point he moves his hand forward toward Li with a slight flip of the wrist. Finishing his turn, he puts his hands back in rest position. The gesture he makes here has some of the same trademarks that we have seen in the other examples: he points toward himself as the “actor” and then makes a movement toward the “recipient”, coinciding with the relevant linguistic material (“I”, “give”, and “you”). The forward motion of the hand, it seems, is not a smooth movement that is designed to only put the hand back in rest position but is rather a brief flip of the wrist indicating transfer.

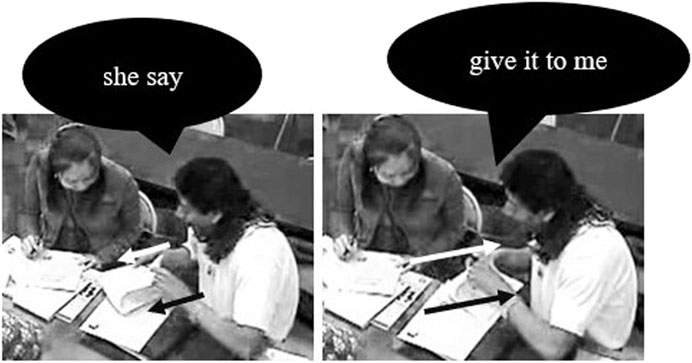

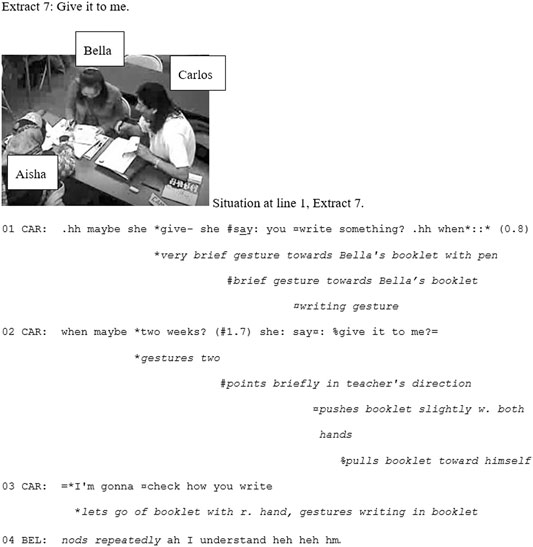

Four and a half months later the following interaction (Extract 7) takes place (Transcription on next page). Carlos, Bella, and Aisha are doing group work. Prior to the extract, a student passes by and hands Bella a booklet. While Aisha continues to work on the assigned task on her own, Bella and Carlos begin talking about the booklet, and Carlos, who already has a similar booklet, begins an explanation that falters, and after some shared laughter he restarts his explanation (line 1). This then runs from line 1 to 3. His point is that it is a booklet for written assignments that the students hand in to be checked by the teacher. In his explanation, “she” refers to the teacher. Bella claims understanding which closes the sequence (line 4).

For the present purposes the interest lies in the embodied actions surrounding the word “give” in line 2. In doing the reported speech (she say give it to me I’m gonna check how you write), Carlos takes the perspective of the teacher. He does so both verbally and gesturally, pushing the booklet slightly away during the production of “say” and pulling it toward himself at the onset of “give” (Figure 15).

This handling of the booklet corresponds with the meaning of “give” and the perspective Carlos is taking as the teacher who is asking to get the booklet from the student. Although the details of the embodied work are different from the previous examples, the handling of the object represents the semantics of the object-transfer construction; from the giver (indexed by the pushing) over the object (physically handled) to the recipient (indexed by the pulling).

Summary: Give

The first example of “give” showed the teacher doing an embodied enactment of the act of giving while instructing a student to give a pen to another student. Carlos participated in the instruction sequence by translating the object-transfer construction into Spanish and performing the “giving” bodily by flipping his wrist, thereby helping a fellow student understand the meaning of “give”.9 The two other examples showed, respectively, a prototypical use of give, “I give you the picture”, accompanied by embodied work indicating transfer from the giver to the recipient, and an enactment of the teacher instructing a student to hand over her homework. The giving and receiving in the latter example were done very concretely by Carlos taking the perspective of teacher and physically handling the book representing the homework. All the examples of “give”, while different from the previous examples, showcase the embodied nature of the object-transfer construction, albeit in locally crafted ways. The embodied work highlighting the object-transfer is dependent on the local ecology of the interaction (the positions of the speakers, the social actions carried out, the nature of the object being transferred etc.), so it is no surprise that the actual transferring of an object is not enacted in identical ways across examples. The point is that the object-transfer, in these cases, is done bodily as well as it is spoken verbally–but the doing of the semantics is occasioned by the interactional environment. The last example (“give it to me”) is a clear case of this.

A Deviant Case?

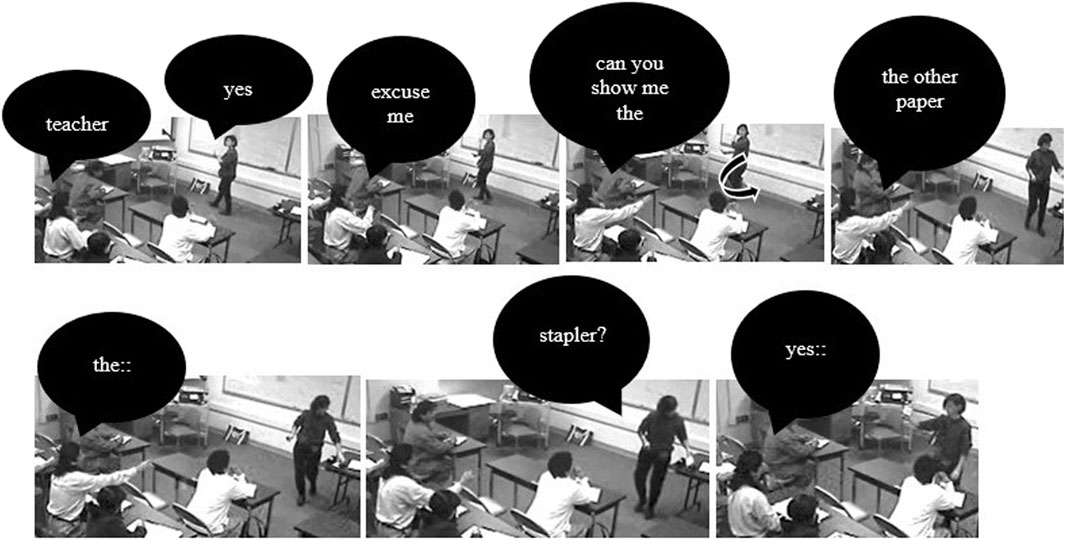

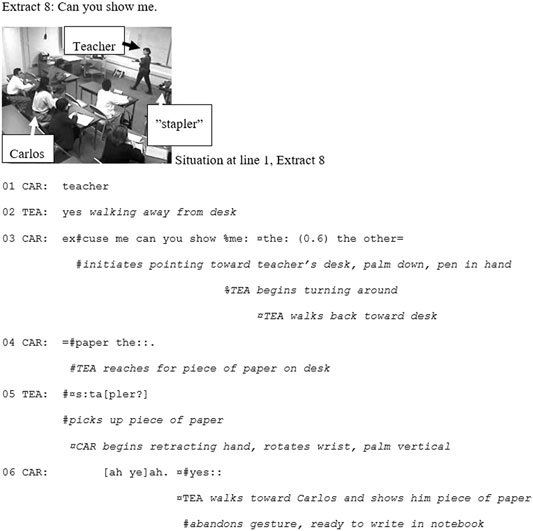

The last extract (8) shows that the verbal object-transfer construction and the deictic-dynamic gesturing described in this paper do not combine into a monolithic package. The talk-gesture pairing is permeable and flexible, allowing Carlos to recalibrate his semiotic resources when required by the interactional circumstances. The entire interaction is graphically represented in Figure 16, but the central action of interest is Carlos’ turn in line 3, which is a request for the teacher to show him a piece of paper on which she has written the word “stapler”, a lexical item that they practiced earlier. The piece of paper is on the teacher’s desk and the teacher is walking away from her desk when Carlos summons her (line 1). When answering the summons (line 2) she continues walking in the same direction.

Orienting to Carlos’ multimodal request, the teacher turns and begins walking back toward her desk during his turn. When he is verbalizing the requested object, “the other paper”, she begins reaching for the piece of paper on her desk with the word “stapler” written on it. She picks it up while saying the word stapler in rising intonation which calls for Carlos’ confirmation (lines 5–6). At the same time, Carlos begins retracting his hand while also slightly changing the nature of the pointing. Finally, the teacher holds up the piece of paper in front of him so that he can see the word, which accomplishes the compliance with the request. When she does that, Carlos abandons the deictic gesture and gets ready to write in his notebook (which is what happens next).

In sum, Carlos’ embodied work here is different from the previous examples. It primarily enhances the deictic part of the construction, i.e., that which he wants the teacher to show him. Interestingly, this is also the part that Carlos has trouble producing verbally. The deixis of the gesturing is designedly imprecise, it seems; Carlos is sitting at a distance from the thing pointed to, but he is not using his index finger to increase precision. He is pointing with his entire hand, palm down and a pen in his hand. The linguistic format, “the other paper”, works as a local specification. Arguably, it is a conspiracy of this linguistic format, the prior classroom work, Carlos’ projected action (a request) and his embodied work (the pointing) that enables the teacher to understand what he is after (see Figure 16). Finally, and speculatively, when Carlos begins retracting his hand, he also makes a rotation of the wrist so that his palm is vertical rather than horizontal. So, when he retracts his hand, the gesturing resembles a motion of pulling toward himself, as if bringing the requested item into his possession. This would, of course, fit in very nicely with the semantics of the construction, but whether or not the embodied work is actually designed to reflect that here is an open question.

Discussion and Conclusion

The data have showcased how an embodied object-transfer construction is used to convey the meaning of something being translocated to somebody by somebody. The words and the gesture work to index, in a locally adapted fashion, the what, wheres, and whos of the situated construction. The deictically fashioned gestures index the actor and the recipient of the action, and the dynamically fashioned gesture indexes the trajectory of the action from actor to recipient. In some cases (extracts 3 and 7), a deictic gesture also marks out the object being transported.

As we showed previously (Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018), Carlos couples the object-transfer gesture and the verbal object-transfer construction quite tightly to begin with. These situations then leave experiential traces that allow Carlos to draw on the gesture as resource in future similar situations. In other words, the gesture is situated and interactionally contingent but flexibly re-usable in more or less the same format over time, with space configurations and physical circumstances determining the specifics of gestural work. Carlos may also employ instantiations of the object-transfer construction without noticeable bodily work (Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018) or with different bodily work (Extract 7). As such, he is constantly calibrating his embodied interactional competence in response to changing environments.

The bodily actions found alongside the use of the object-transfer constructions seem to be of a primordial kind; they are employed before prima facie recognizable talk conveying transfer of something (“Now you to me”) and are therefore not to be thought of as a bi-product of spoken language. The data show that the object-transfer construction itself, as used by Carlos from an early stage, carries meaning (Taylor, 1998), perhaps because it exists as a semantic unit in Spanish. This constitutes very concrete and salient empirical evidence for the fundamentally and inherently embodied nature of language, grammar, and linguistic categorization. We understand and produce the categories of language, through which we perceive and conceptualize the world, with our bodies. The human capacity for stringing words together for communicative purposes is fundamentally rooted in recurring bodily actions in the world (Streeck, 2021). It is important, in this respect, to recall the extracts that focused, entirely or partially, on the teacher’s embodied actions. These examples indicate that the bodily performance of the object-transfer construction transcends individual speakers, suggesting that the empirical phenomenon is a fundamental aspect of the human condition. The findings here mirror the point brought forth by Keevalik (2018) and Streeck (2018) that both action formation and grammar are inherently multimodal. While this study has the limitations of a case-study, the fact that the investigated phenomenon can also be found in another participant (the teacher) implies that it is a worthwhile pursuit to investigate for other speakers, including L2 learners, as well.

Adding to the complexity of the phenomenon, the embodied work is not only a bodily enactment of the semantics of a construction, nor is it just a crutch in times of linguistic trouble, it also serves fundamental interactional purposes in the pursuit of intersubjectivity. There is evidence for this in the observation that Carlos predominantly uses the object-transfer gesture in situations where he gives instructions or explanations. There are quite a few instances in Carlos’ data where the object-transfer gesture is not deployed alongside the verbal use of the construction, cf. Eskildsen and Wagner (2018). Similarly, Extract 8 here (“can you show me the other paper”) showed Carlos drawing on other bodily resources to accomplish other actions (a request) through the use of the object-transfer construction. In other words, Carlos predominantly but not exclusively uses the embodied object-transfer construction as a method of instructing and/or enhancing and clarifying aspects of the ongoing talk, especially in the face of waning intersubjectivity. This can be seen in the absence of the object-transfer gesture in the deviant case and in extracts 2–7 where the embodied object-transfer construction as ensemble was used for those precise purposes: instructing, clarifying, explaining.

Over time (not shown here in the interest of space), Carlos further diversifies his interactional uses of the object-transfer construction, but there is a link between the social actions that Carlos accomplishes and his use of the embodied object-transfer construction (see Eskildsen and Wagner, 2018, for further discussion). This is at the core of his embodied interactional competence. He is not just using the object-transfer construction to talk about some scene in which somebody causes somebody else to receive something (the semantic meaning of the construction); instead he is using it for specific purposes in social situations that call on responses from co-participants. Carlos’ uses of the object-transfer construction is not only embodied; it is found in specific interactional environments and materializes out of social experience. Its use and understanding seem to be epiphenomenal to engaging in social sense-making practices. If this is a fundamental truth about human language, then it is the very accomplishment of social action that brings about linguistic form-meaning pairings. Ultimately, then, language is not only embodied; it is a residual of social sense-making practices, constantly brought to life by people in and through social interaction.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Data are available as stream from a server and password protected. Downloads not legal.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Portland State University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1Transcription conventions are in the appendix at the end of article.

2‘teach’ and ‘lend’ are the only other verbs (seven different verbs in total) used by Carlos in this construction.

3Analyses of Extracts 2 and 3 have been adopted and adapted from Eskildsen and Wagner (2018).

4Unfortunately, the video resolution is not high enough to reveal the format of Carlos’ deictic gestures (e.g., whether he points with his index finger or thumb), but the focus here is on the semantics of the transfer indicated by the entire bodily action, as he moves his hand from the instructed teller of the story via the story to the recipient.

5In the subsequent negotiation of who is supposed to mime and guess, respectively, Carlos does refer to Chloe and himself both verbally (using ‘we’) and gesturing clearly toward both of them.

6The relatively high number of instances found in instruction-sequences might be epiphenomenal to the classroom setting where instructing is a very frequent action. Teachers engage in many instructions and students may also instruct each other as they negotiate how a given and/or current task is to be carried out.

7The word ‘pensil’ is a transcription approximation. I have consulted an L1 Spanish speaking colleague and she agreed with the transcription but could not explain the use of this word here. It is not standard Peninsular Spanish.

8It could also be directed at Carlos, but the teacher is visibly oriented to Rosa and Kamil at this point, so this is unlikely.

9Carlos performs a similar gesture in a display of understanding that also works as a request for confirmation of “give” in another situation approximately 3 months later. This is left out in the interest of space.

References

aus der Wieschen, M. V., and Eskildsen, S. W. (2019). “Embodied and Occasioned Learnables and Teachables in an Early EFL Classroom,” in Conversation Analytic Perspectives on English Language Learning and Teaching in Global Contexts: Constraints and Possibilities. Editors H. t. Nguyen, and T. Malabarba (Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters), 31–58.

Bartning, I., and Hammarberg, B. (2007). The Functions of a High-Frequency Collocation in Native and Learner Discourse: The Case of French C'est and Swedish Det Är. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguistics 45 (1), 1–43. doi:10.1515/iral.2007.001

Bresnan, J., Cueni, A., Nikitina, T., and Baayen, H. (2007). “Predicting the Dative Alternation,” in In Cognitive Foundations Of Interpretation. Editors G. Boume, I. Krämer, and J. Zwarts (Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Science), 69–94.

Brouwer, C. E. (2003). Word Searches in NNS-NS Interaction: Opportunities for Language Learning? Mod. Lang. J 87 (4), 534–545. doi:10.1111/1540-4781.00206

Campbell, A. L., and Tomasello, M. (2001). The Acquisition of English Dative Constructions. Appl. Psycholinguistics 22, 253–267. doi:10.1017/s0142716401002065

Cochet, H., and Vauclair, J. (2014). Deictic Gestures and Symbolic Gestures Produced by Adults in an Experimental Context: Hand Shapes and Hand Preferences. Laterality: Asymmetries Body, Brain Cogn. 19 (3), 278–301. doi:10.1080/1357650x.2013.804079

Cooperrider, K., Abner, N., and Goldin-Meadow, S. (2018). The Palm-Up Puzzle: Meanings and Origins of a Widespread Form in Gesture and Sign. Front. Commun. 3. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2018.00023

Doughty, C., and Long, M. (2003). “The Scope of Inquiry and Goals of SLA,” in Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Editors C. Doughty, and M. Long (Malden, MA: Blackwell), 1–16.

Ellis, N. C., and Ferreira-Junior, F. (2009). Construction Learning as a Function of Frequency, Frequency Distribution, and Function. Mod. Lang. J. 93 (3), 370–385. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00896.x

Eskildsen, S. W. (2009). Constructing Another Language--Usage-Based Linguistics in Second Language Acquisition. Appl. Linguistics 30 (3), 335–357. doi:10.1093/applin/amn037

Eskildsen, S. W. (2011). “The L2 Inventory in Action: Conversation Analysis and Usage-Based Linguistics in SLA,” in L2 Learning as Social Practice: Conversation-Analytic Perspectives. Editors G. Pallotti, and J. Wagner (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i, National Foreign Language Resource Center), 337–373.

Eskildsen, S. W. (2012). L2 Negation Constructions at Work. Lang. Learn. 62 (2), 335–372. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00698.x

Eskildsen, S. W. (2014). What's New?: A Usage-Based Classroom Study of Linguistic Routines and Creativity in L2 Learning. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguistics 52 (1), 1–30. doi:10.1515/iral-2014-0001

Eskildsen, S. W. (2015). What Counts as a Developmental Sequence? Exemplar-Based L2 Learning of English Questions. Lang. Learn. 65 (1), 33–62. doi:10.1111/lang.12090

Eskildsen, S. W. (2017). “Emergent L2 Creativity,” in Multiple Perspectives on Language Play. Editor N. Bell (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), 281–316.

Eskildsen, S. W. (2018). Building a Semiotic Repertoire for Social Action: Interactional Competence as Biographical Discovery. Classroom Discourse 9 (1), 68–76. doi:10.1080/19463014.2018.1437052

Eskildsen, S. W. (2020a). “From Constructions to Social Action,” in Ontologies of English. Reconceptualising the Language for Learning, Teaching, and Assessment. Editors C. Hall, and R. Wicaksono (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 59–79. doi:10.1017/9781108685153.004

Eskildsen, S. W. (2020b). “Creativity and Routinisation in L2 English – Two Usage-Based Case-Studies,” in Usage-Based Dynamics in Second Language Development. Editors W. Lowie, M. Michel, A. Rousse-Malpat, M. Keijzer, and R. Steinkrauss (Bristol UK: Multilingual Matters), 107–129.

Eskildsen, S. W. (2021). “Doing the Daily Routine: Development of L2 Embodied Interactional Resources through a Recurring Classroom Activity,” in Classroom-Based Conversation Analytic Research: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Pedagogy. Editors S. Kunitz, O. Sert, and N. Markee (Cham: Springer), 71–101. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-52193-6_5

Eskildsen, S. W., and Cadierno, T. (2007). “Are Recurring Multi-word Expressions Really Syntactic Freezes? Second Language Acquisition from the Perspective of Usage-Based Linguistics,” in Collocations and Idioms 1: Papers from the First Nordic Conference on Syntactic Freezes. Editors M. Nenonen, S. Niemi, and J. Niemi, (Joensuu: Joensuu University Press), 86–96.

Eskildsen, S. W., Cadierno, T., and Li, P. (2015). “On the Development of Motion Constructions in Four Learners of English,” in Usage-Based Perspectives On Second Language Learning. Editors T. Cadierno, and S. W. Eskildsen (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), 207–232. doi:10.1515/9783110378528-011

Eskildsen, S. W., and Kasper, G. (2019). “Interactional Usage-Based L2 Pragmatics,” in The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Pragmatics. Editor N. Taguchi (New York: Routledge), 176–192. doi:10.4324/9781351164085-12

Eskildsen, S. W., and Wagner, J. (2015). Embodied L2 Construction Learning. Lang. Learn. 65 (2), 419–448. doi:10.1111/lang.12106

Eskildsen, S. W., and Wagner, J. (2018). “From Trouble in the Talk to New Resources: The Interplay of Bodily and Linguistic Resources in the Talk of a Speaker of English as A Second Language,” in Longitudinal Studies on the Organization of Social Interaction. Editors S. Pekarek Doehler, J. Wagner, and E. González-Martínez (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 143–171. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-57007-9_5

Eskildsen, S. W., and Wagner, J. (2013). Recurring and Shared Gestures in the L2 Classroom: Resources for Teaching and Learning. Eur. J. Appl. Linguistics 1 (1), 1–23. doi:10.1515/eujal-2013-0007

Evnitskaya, N., and Berger, E. (2017). Learners' Multimodal Displays of Willingness to Participate in Classroom Interaction in the L2 and CLIL Contexts. Classroom Discourse 8 (1), 71–94. doi:10.1080/19463014.2016.1272062

Garfinkel, H. (2002). Ethnomethodology’s Program: Working Out Durkheim’s Aphorism. Legacies of Social Thought Series. Editor A. W. Rawls (Lanham, MD: Rowan and Littlefield).

Goldberg, A. E. (2003). Constructions: A New Theoretical Approach to Language. Trends. Cogn. Sci. 7 (5), 219–224. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00080-9

Graziano, M., and Gullberg, M. (2019). When Speech Stops, Gesture Stops: Evidence from Developmental and Crosslinguistic Comparisons. Front. Psychol. 9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00879

Gullberg, M. (2010). Methodological Reflections on Gesture Analysis in Second Language Acquisition and Bilingualism Research. Second Lang. Res. 26, 75–102. doi:10.1177/0267658309337639

Gullberg, M. (2011). “Multilingual Multimodality: Communicative Difficulties and Their Solution in Second-Language Use,” in Embodied Interaction. Language and Body in the Material World. Editors J. Streeck, C. Goodwin, and C. LeBaron (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 137–151.

Hall, J. K., Hellermann, J., and Pekarek Doehler, S. (2011). L2 Interactional Competence And Development. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 288.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1970). “Language Structure and Language Function,” in New Horizons in Linguistics. Editor J. Lyons (Penguin Books), 140–165.

Hauser, E. (2013). Stability and Change in One Adult's Second Language English Negation. Lang. Learn. 63 (3), 463–498. doi:10.1111/lang.12012

Horbowicz, P., and Nordanger, M. (2022). Epistemic Constructions in L2 Norwegian: A Usage-Based Longitudinal Study of Formulaic and Productive Patterns. Language and Cognition, 1–29. doi:10.1017/langcog.2021.9

Ishida, M. (2009). “Development of Interactional Competence: Changes in the Use of Ne in L2 Japanese during Study Abroad,” in Talk-in-Interaction: Multilingual Perspectives. Editors H. t. Nguyen, and G. Kasper (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i, National Foreign Language Resource Center), 351–387.

Keevalik, L. (2018). What Does Embodied Interaction Tell Us about Grammar? Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 51, 1–21.

Kendon, A. (1986). Some Reasons for Studying Gesture. Semiotica 62, 3–28. doi:10.1515/semi.1986.62.1-2.3

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511807572

Kim, Y. (2009). “The Korean Discourse Markers -Nuntey and Kuntey in Native-Nonnative Conversation,” In Talk-in-Interaction: Multilingual Perspectives, Editors H. t. Nguyen, and G. Kasper (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i, National Foreign Language Resource), 317–350.

König, C. (2020). A Conversation Analysis Approach to French L2 Learning: Introducing and Closing Topics in Everyday Interactions. New York: Routledge.

Kramsch, C. (1986). From Language Proficiency to Interactional Competence. Mod. Lang. J. 70 (4), 366–372. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05291.x

Langacker, R. W. (1987). Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Theoretical Prerequisites (Stanford: Stanford University Press), Vol. 1.

Lesonen, S., Steinkrauss, R., Suni, M., and Verspoor, M. (2020b). Dynamic Usage-Based Principles in the Development of L2 Finnish Evaluative Constructions. Appl. Linguistics 2020, 1–32.

Lesonen, S., Steinkrauss, R., Suni, M., and Verspoor, M. (2020a). Lexically Specific vs. Productive Constructions in L2 Finnish. Lang. Cogn. 12, 526–563. doi:10.1017/langcog.2020.12

Lesonen, S., Suni, M., Steinkrauss, R., and Verspoor, M. (2018). From Conceptualization to Constructions in Finnish as an L2. P&C 24 (2), 212–262. doi:10.1075/pc.17016.les

Levinson, S. C. (2013). “Action Formation and Ascription,” in The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Editors T. Stivers, and J. Sidnell (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell), 103–130.

Li, P., Eskildsen, S. W., and Cadierno, T. (2014). Tracing an L2 Learner's Motion Constructions over Time: A Usage-Based Classroom Investigation. Mod. Lang. J. 98, 612–628. doi:10.1111/modl.12091

Lilja, N. (2014). Partial Repetitions as Other-Initiations of Repair in Second Language Talk: Re-establishing Understanding and Doing Learning. J. Pragmatics 71, 98–116. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2014.07.011

Lilja, N., and Piirainen-Marsh, A. (2019). How Hand Gestures Contribute to Action Ascription. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 52 (4), 343–364. doi:10.1080/08351813.2019.1657275

Masuda, K. (2011). Acquiring Interactional Competence in a Study Abroad Context: Japanese Language Learners' Use of the Interactional Particle Ne. Mod. Lang. J. 95 (4), 519–540. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01256.x

McNeill, D. (1985). So You Think Gestures Are Nonverbal? Psychol. Rev. 92 (3), 271–295. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.92.3.350

McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and Mind. What Gestures Reveal about Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mellow, J. D. (2006). The Emergence of Second Language Syntax: A Case Study of the Acquisition of Relative Clauses. Appl. Linguistics 27 (4), 645–670. doi:10.1093/applin/aml031

Mondada, L. (2014). “Pointing, Talk, and the Bodies,” in From Gesture in Conversation to Visible Action as Utterance: Essays in Honor of Adam Kendon. Editors M. Seyfeddinipur, and M. Gullberg (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 95–124. doi:10.1075/z.188.06mon

Mori, J., and Hayashi, M. (2006). The Achievement of Intersubjectivity through Embodied Completions: A Study of Interactions between First and Second Language Speakers. Appl. Linguistics 27 (2), 195–219. doi:10.1093/applin/aml014

Mortensen, K. (2009). Establishing Recipiency in Pre-beginning Position in the Second Language Classroom. Discourse Process. 46, 491–515. doi:10.1080/01638530902959463

Mortensen, K. (2016). The Body as a Resource for Other-Initiation of Repair: Cupping the Hand behind the Ear. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 49 (1), 34–57. doi:10.1080/08351813.2016.1126450

Müller, C. (2004). “Forms and Uses of the Palm up Open Hand: A Case of A Gesture Family?,” in The Semantics and Pragmatics of Everyday Gestures. Editors C. Müller, and R. Posner (Berlin: Weidler), 233–256.

Olsher, D. (2004). “Talk and Gesture: The Embodied Completion of Sequential Actions in Spoken Interaction,” in Second Language Conversations. Editors R. Gardner, and J. Wagner (London: Continuum), 221–245.

Pekarek Doehler, S., and Balaman, U. (2021). The Routinization of Grammar as a Social Action Format: A Longitudinal Study of Video-Mediated Interactions. Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 54 (2), 183–202. doi:10.1080/08351813.2021.1899710

Pekarek Doehler, S., and Berger, E. (2018). L2 Interactional Competence as Increased Ability for Context-Sensitive Conduct: A Longitudinal Study of Story-Openings. Appl. Linguistics 39 (4), 555–578.

Pekarek Doehler, S. (2018). Elaborations on L2 Interactional Competence: The Development of L2 Grammar-For-Interaction. Classroom Discourse 9 (1), 3–24. doi:10.1080/19463014.2018.1437759

Pekarek Doehler, S., and Pochon-Berger, E. (2015). “The Development of L2 Interactional Competence: Evidence from Turn-Taking Organization, Sequence Organization, Repair Organization and Preference Organization,” in Usage-Based Perspectives on Second Language Learning. Editors T. Cadierno, and S. W. Eskildsen (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), 233–268.

Roehr-Brackin, K. (2014). Explicit Knowledge and Processes from a Usage-Based Perspective: The Developmental Trajectory of an Instructed L2 Learner. Lang. Learn. 64, 771–808. doi:10.1111/lang.12081

Römer, U., and Berger, C. M. (2019). Observing the Emergence of Constructional Knowledge. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis 41 (5), 1089–1110. doi:10.1017/s0272263119000202

Schegloff, E. A. (1996). “Turn Organization: One Intersection of Grammar and Interaction,” in Interaction and Grammar. Editors E. Ochs, E. A. Schegloff, and S. A. Thompson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 52–133. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511620874.002

Seo, M.-S., and Koshik, I. (2010). A Conversation Analytic Study of Gestures that Engender Repair in ESL Conversational Tutoring. J. Pragmatics 42, 2219–2239. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.01.021

Streeck, J. (2009). Gesturecraft: The Manu-Facture of Meaning. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/gs.2

Streeck, J. (2018). Grammaticalization and Bodily Action: Do They Go Together? Res. Lang. Soc. Interaction 51 (1), 26–32. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413889

Streeck, J. (2021). The Emancipation of Gestures. Interactional. Linguistics. 1 (1), 90–122. doi:10.1075/il.20013.str

Taylor, J. R. (1998). “Syntactic Constructions as Prototype Categories,” in The New Psychology of Language. Editor M. Tomasello (Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum), 177–202.

Thompson, S. A. (1988). Information Flow and “Dative Shift” in English Discourse. Santa Barbara Pap. Linguistics Vol. 2, 147–163.

Tode, T., and Sakai, H. (2016). Exemplar-based Instructed Second Language Development and Classroom Experience. Itl 167 (2), 210–234. doi:10.1075/itl.167.2.07tod

Wilkins, D. (2003). “Why Pointing with the Index Finger Is Not a Universal (In Sociocultural and Semiotic Terms),” in Pointing: Where Language, Culture, and Cognition Meet. Editor S. Kita (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 171–215.

Year, J., and Gordon, P. (2009). Korean Speakers' Acquisition of the English Ditransitive Construction: The Role of Verb Prototype, Input Distribution, and Frequency. Mod. Lang. J. 93 (3), 399–417. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00898.x

Appendix A: Transcription Conventions

CAR:, TEA: Participants

Wei[rd w]ord Beginning and end of overlapping talk

[yeah]

#/¤/%/& Marks beginning of embodied action in transcribed talk (in one case, “-------” marks a gesture that is held for a while before the onset of talk)

#/¤/%/& Description of embodied conduct (in italics) on line below transcribed talk (in some cases, embodied conduct that is not

central to the investigated phenomenon is described without marked alignment with the talk)

(1.0) Pause/gap in seconds and tenth of seconds

(.) Micro pause (< 0.2 seconds)

word=

=word Multi-line turn

word Prosodic emphasis

wo:rd Prolongation of preceding sound

word? Rising intonation

word. Falling intonation

↑word Shift to high pitch

WORD Louder than surrounding talk

°word° Softer than surrounding talk

->word<- Faster than surrounding talk

wo- Cut-off

*word* Croaky voice

(word) Uncertain transcription

.hh / hh Hearable in-breath // out-breath

Keywords: gesture, second language learning, conversation analysis, usage-based linguistics, interactional competence

Citation: Eskildsen SW (2021) Embodiment, Semantics and Social Action: The Case of Object-Transfer in L2 Classroom Interaction. Front. Commun. 6:660674. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.660674

Received: 29 January 2021; Accepted: 12 July 2021;

Published: 27 September 2021.

Edited by:

Xiaoting Li, University of Alberta, CanadaReviewed by:

Jennifer Hinnell, University of British Columbia, CanadaEvelyne Berger, Institut et Haute école de la santé La Source, Switzerland

Copyright © 2021 Eskildsen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: S. W. Eskildsen, c3dlQHNkdS5kaw==

S. W. Eskildsen

S. W. Eskildsen