- Communication Studies, Furman University, Greenville, SC, United States

This study analyzes securitized discourses and counter narratives that surround the COVID-19 pandemic. Controversial cases of security related political communication, salient media enunciations, and social media reframing are explored through the theoretical lenses of securitization and cascading activation of framing in the contexts of Slovakia, Russia, and the United States. The first research question explores whether and how the frame element of moral evaluation factors into the conversations on the securitization of the pandemic. The analysis tracks the framing process through elite, media, and public levels of communication. The second research question focused on fairly controversial actors— “rogue actors” —such as individuals linked to far-leaning political factions or militias. The proliferation of digital media provides various actors with opportunities to join publicly visible conversations. The analysis demonstrates that the widely differing national contexts offer different trends and degrees in securitization of the pandemic during spring and summer of 2020. The studied rogue actors usually have something to say about the pandemic, and frequently make some reframing attempts based on idiosyncratic evaluations of how normatively appropriate is their government's “war” on COVID-19. In Slovakia, the rogue elite actors at first failed to have an impact but eventually managed to partially contest the dominant frame. Powerful Russian media influencers enjoy some conspiracy theories but prudently avoid direct challenges to the government's frame, and so far only marginal rogue actors openly advance dissenting frames. The polarized political and media environment in the US has shown to create a particularly fertile ground for rogue grassroots movements that utilize online platforms and social media, at times going as far as encouragement of violent acts to oppose the government and its pandemic response policy.

Introduction

COVID-19 exemplifies a far reaching and multidimensional type of global emergency, where communication plays an important role. The spectrum of communication-related concerns ranges from a type of deliberate strategic messaging by governmental authorities to an “infodemic” of misinformation that spreads online. Interdisciplinary theoretical approaches offer comprehensive tools for analyses to illuminate such a complex maze of phenomena. This paper specifically presents an analytical lens for the examination of frames within securitized discourses and counter narratives that surround the pandemic. The proposed approach is applied to explore controversial cases of security related political communication and subsequent salient media enunciations on COVID-19 responses in Slovakia, Russia, and the United States (US).

Scholars (Vultee, 2010a,b; Watson, 2012) have made a convincing argument for integrating the political science theory of securitization (Buzan et al., 1998) with the media/communication model of framing (Goffman, 1974; Gitlin, 1980; Entman, 1993, 2003). Securitization reflects on the discursive acts of justification of extraordinary means to eliminate a threat. This sort of process can be essentially understood as a strategic persuasive master frame that is articulated by elites and passed through media coverage, to convince various publics of the appropriateness of the employed measures. In recent years, both conceptions have further evolved within their respective disciplines. Researchers expand and hone securitization to address emerging questions and changing dynamics of political communities within current contexts such as globalization. Important examples of these novel endeavors are in the growth of literature on just securitization (e.g., Floyd, 2019a) or the health security sector (e.g., Bengtsson and Rhinard, 2019). Communication scholars advise the revamping of framing to acknowledge disruptions of global media environments amid digitalization and the proliferation of internet platforms. A noteworthy example is a focus on rogue actors who disrupt persuasive framing routes initiated by elite politicians and legacy media organizations (Entman and Usher, 2018). These current developments are yet to be translated to the theoretical and empirical intersections between framing and securitization. Such a course is arguably necessary as it can reveal important insights on some of the highly concerning developments related to COVID-19.

Three cases are examined to verify the extent of applicability of securitization/framing as an updated analytical lens. Slovakia offers an instance of high and midlevel political elites contesting securitization of public health, economic threats, and human rights. One particularly controversial aspect of Slovakia's pandemic response involves unconstitutional surveillance legislation. The Russian case illustrates how legacy and digital media opinion leaders compete over the dominance of different framing streams. Nationalistically oriented Russian pundits discuss the situation around the novel coronavirus outbreak with frequent allusions to WWII commemoration and other remarks to reassert Russian exceptionalism. The US state of Michigan is an example of a place where anti-government and far-right militias protested in a standoff against the Governor's administration. The case gained international notoriety when militia members, armed with assault rifles, stormed the Capitol building in protest of stay-at-home orders. This type of “activist” activity reflects deeper issues within American society, which has been intensely polarized long before the infectious illness reached the country. This is painfully clear as the Boogaloo online movement attempts to co-opt the pandemic to start a civil war. The cases encompass a diverse set of circumstances and different types of political systems. All three cases exemplify controversial securitized framings around the threat of COVID-19, while the main arena of each manifests a distinct level of the framing process. Interesting contrasts and linkages materialize when considering the normative dimensions of the securitization argument and counterarguments emerging in the negotiations over how morally just is the “war on COVID.” The details of the process are further investigated through qualitative frame analysis. This study indeed puts the explanatory validity of the proposed theoretical framework to the test. Interdisciplinary theory building effort benefits from validation across such varied situations.

Beyond the scholarly theory building interest, this study offers valuable insights into communication surrounding problematic sociopolitical developments that are occurring in different locales around the world. Henceforth, practitioners of public relations, political consultants, journalists, and several other types of specialists can find valuable information through securitization/framing analysis. Impacts of COVID-19 are likely to be massive across numerous dimensions of global life. Rigorously informed approaches can become vital for mitigating the negative impacts of the pandemic. This article aims to provide one step toward the facilitation of an analytically informed look into the political and media communication processes that accompany the pandemic in Central Europe, Eurasia, and North America.

Review of Literature

The Copenhagen School's securitization as conceptualized by Buzan et al. (1998) represents an influential theory which is widely cited and utilized not just within its original international relations field, but across a plethora of fields and areas of inquiry (Baele and Thomson, 2017). In short, Buzan et al. characterize securitization as a speech act process, through which an actor implies that an existential threat looms over a significant referent object, and therefore certain extraordinary measures must be imposed to protect the referent object. Among the most noteworthy contributions of the securitization theory is widening the comprehension of the phenomenon of security and its accompanying occurrences. The following paragraphs first highlight some of these noteworthy components of securitization theory and then offer an account of the role that communication, specifically framing, plays in the securitization processes.

Buzan et al. (1998) conceive securitization as a situation where the referent object is not limited to just a nation-state. Several other collective units may and frequently do perform as referent objects; for instance, an ethnic group, a political group, a religious group, or even such broad collective units as an international pact, or a civilization (Buzan and Waever, 2009; Sperling and Webber, 2019). Furthermore, the possible assortment of referent objects is not restricted to human collectives but may include other concepts, such as a culture, an ideology, the cyberspace, or the climate. The defining feature determines that a referent object is accepted as worthy of protection and preservation by the larger society, or is accepted as such within a vital enough segment of the society.

Copenhagen School also argues that military related and sovereignty related understandings of securitization as applied to nation-state level are too constricted and do not fully capture a set of phenomena that are perceived and treated as security risks in societies (Buzan et al., 1998). Securitization scholars propose various security sectors including cybersecurity (e.g., Hart et al., 2014); economic security (e.g., Floyd, 2019b); health security (e.g., Kelle, 2007; Youde, 2018; Bengtsson and Rhinard, 2019); environmental security (e.g., Floyd, 2007; Fischhendler et al., 2016; Maertens, 2019); climate security (e.g., Scott, 2012); food security (e.g., Nussio and Pernet, 2013); or water security (e.g., Allouche et al., 2011). Depending on the context, the list of prospective security sectors is virtually unlimited, as long as other conditions for securitization are met. Floyd (2011, 2019a) also stresses the normative stipulation of the referent object, which ought to be an ethically appropriate entity to be protected.

A security threat does not necessarily imply complete physical destruction but might imply changing, or seriously altering, the essence of the referent object (Buzan et al., 1998). This is still in a way an existential threat. An example can be drawn from the environmental and ecological security sector. While with the extinction of certain species, an ecosystem does not necessarily completely cease to exist, it is altered from its previous form (Inouye, 2005). This alteration is considered securitized if it is believed to corrupt the essence of the referent object; the essential characteristics of the particular ecosystem in the example. So the threat must contravene an existential factor in the interpretation of the securitized discourse. Just as a military conflict does not always lead to the total obliteration of a political nation or a genocide of its people, wars bring other risks such as abridging traditions or liberties, which also represent existential attacks on the nation's defining essential features.

A crucial tenet of the theory poses that securitization is used for advocating extraordinary measures to mitigate the threat (Buzan et al., 1998). The Copenhagen School defines these types of measures as such procedures and actions that stray away from normal politics and at times even the usual principles of liberal democracy. Henceforth, securitization has been initially propositioned as a rather problematic occurrence. From this understanding, securitization is a power grabbing tool, which allows politicians and elites to bend the democratic principles that they should uphold. This reasoning reflects the formula that more security means less liberty and vice-versa, but also it pre-supposes that issues usually have possible liberal-democratic political solutions that should fit within the “normal politics” and do not necessitate extraordinary measures. However, other securitization scholars challenge the validity of the assumptions around extraordinary measures. Bourbeau (2014) points out many securitization processes are accompanied by very non- extraordinary measures. Leonard (2010) illustrates that securitization can be accompanied by measures which might be new to the specific issue but in of themselves are rather routine practices. Floyd (2016) explains how measures that result from securitization may simply encompass a change in behavior, and does not have to be particularly extraordinary but is nevertheless relatively substantial. Floyd (2011, 2019a) problematizes the theory's normative assumption, which is against extraordinary measures, as she instead proposes a just security theory inspired by the just war theory.

Upon reflecting on the key arguments of the securitization theory as well as some resonant critiques, the following working definition of securitization is employed in this article. The first tenet; securitization is a discursive act (Buzan et al., 1998). The second tenet; through securitization, a securitizing actor persuades that a normatively worthwhile referent object is under an existential threat (Buzan et al., 1998; Floyd, 2011, 2019a). The third tenet; the securitizing actor further argues that specific measures must be implemented to mitigate the threat; while the characteristics of the mitigating measures vary, some may include relatively extraordinary emergency procedures that are normally not employed in relation to the situation (Floyd, 2011, 2019a). The fourth tenet; securitization and its measures may be negative, positive, or mixed depending on a holistic normative evaluation of the relevant circumstances (Floyd, 2011, 2019a). This assemblage of defining tenets retains some important key arguments of the Copenhagen School but also incorporates significant amendments and additions that have emerged in the last two decades.

Buzan et al. (1998) describe securitization as a speech act implying a constructivist notion where the persuasive discursive process leads to the formation of particular realities. So, for some actors, securitization handily serves as a useful strategic tool enabling certain (perhaps extraordinary) measures, which consequently fortify the competitive positions of the actors in the political arena. The point that securitization is a speech act, an act of communication, pre-supposes there is an audience interacting with the persuasive message articulated by the actor. Copenhagen Schools poses that securitization succeeds when the audience accepts the actor's securitizing move with threat allegation and the prescription of response measures.

Communication scholarship has understandably taken notice of the securitization theory. However, Watson (2012) alleges the American academia, which is the largest and rather dominating in the global communication literature, has not engaged the securitization theory as much as is possible, and as can be possibly useful for the explanation of important phenomena related to communication aspects of securitizing processes. Within the more recent years, communication researchers continue to involve securitization theory (e.g., Engelbert and Awad, 2014; Vultee et al., 2015; Fischhendler et al., 2016; Chouliaraki and Georgiou, 2017), but the aggregate body of the integrated communication securitization literature remains rather thin.

Vultee (2010a,b) and Watson (2012) propose conceptual merging between securitization and the media/communication model of framing (Goffman, 1974; Gitlin, 1980; Entman, 1993, 2003). The model/theory of framing has several paradigmatically diverse articulations within the field of communication (e.g., Entman, 1993; Pan and Kosicki, 1993; Scheufele, 1999; D'Angelo, 2002). One of the most widely cited formulations of framing is Entman's frame as a structure that defines a problem, attributes causes, makes moral evaluations, and proposes solutions to the problem. According to Entman, the structure of the frame exists in several incarnations. First, it is a discursive structure within persuasive messages of political figures and other elites who make appeals within the sociopolitical conversation arena. A frame is also a media coverage structure. Within this incarnation, a frame serves to select particular discursive features to accompany the news coverage. These discursive features include the choice of words, definitions, illustrations, visuals, etc. Another incarnation of a frame is when it functions as a cognitive shortcut—a psychological schema, which serves in the perception of individuals–of the public—to interpret events. The multiform character of frames is summarized by Entman et al. (2009) in that “framing is an individual psychological process, but it is also an organizational process and product, and a political strategic tool” (p. 175).

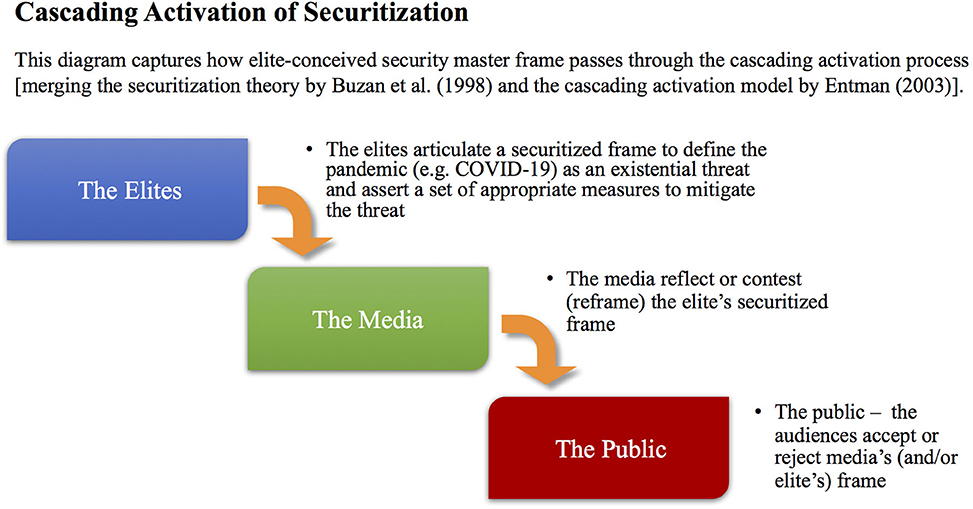

The various incarnations of frames are linked within Entman (2003) cascading activation model. This process suggests that frames are frequently conceived by members of the elite, including but not limited to governmental officials. The individuals with such influence and media visibility are considered to be positioned at the top of the cascade. Then the elite discursive frames go through the filter of mass media organizations, which are the middle portion of the cascade, where some type of reframing may or may not occur. For instance, if a frame is highly contested among the elites, likely, this frame also gets more challenged within the media coverage. Finally, the media content frames are depicted to the mass audiences via the media coverage. The interpretations suggested through the mediated frames interact with the cognition of the viewers, listeners, or readers, who consequently accept or reject the frame. Frames can originate within any level of the cascade, not just among the elites. But for a frame to travel metaphorically up-the-cascade, it is rather challenging and rare. Hence, first political elites, then the media elites, and then members of the public have a different magnitude of ability to advance their framing through the cascade. The metaphorical gravity force privileges those with power and media access.

The cascading activation model allows for an explanation of the functioning of securitization as a communication framing phenomenon. Elite actors strategically assert securitizing frame, which defines the problem as an existential threat, and where the suggested solution involves a specific set of measures. Vultee (2010a) suggests that securitization is “an organizing principle invoked by political actors—and, crucially, amplified, or tamed down by the news media—in an effort to channel the ways in which issues are thought about” (p. 78). Buzan et al. (1998) consider securitization “successful” once the target audience, for instance, the voters among the public, accepts securitization and the specific measures it has requested to employ. So it can be concluded that from the Copenhagen School's perspective, securitization is complete once the frame remains rather intact as it traverses through the cascade and is embraced by the media and the public. Entman (2003) posits that the success of a frame depends on a number of factors, including the degree of contestation of a frame on different levels, the interaction of the frame with other significant frames, and the overall cultural congruence of the frame. Accordingly, empirical studies demonstrate that securitization may fail under certain circumstances when crossing through the media level (Vultee, 2010b) or also it may be rejected by members of the media audience (Vultee et al., 2015).

Watson (2012) asserts framing and securitization create promising theoretical tandem: “not only that these two bodies of work are compatible and based on strongly overlapping theoretical and normative commitments, but also that “security” operates as a distinct master frame similar to “rights” and “injustice” and that securitization theory may usefully be understood as a subfield of framing” (p. 280). Consequently, this paper attempts to advance the theoretical combination by considering the recent advances in both theoretical reservoirs, identifying noteworthy overlaps, and applying the framework to an important contemporary issue – the COVID-19 pandemic.

Knowledge Building and Theoretical Frontiers

Copenhagen School stresses the audience's acceptance of the securitizing move and consequent measures is central to the actualization of securitization (Buzan et al., 1998). The audiences of securitization primarily include the other elites, the security professionals, and the public (Salter and Piche, 2011). A larger number of these stakeholders receive the majority of the securitizing messages through media. Except for the already referenced works of communication framing scholars, the media are not receiving a substantial place in securitization literature. Some studies offer a limited scope for mentions of the media as sites of manifestations or as mere tools for the securitizing actors (e.g., Bengtsson et al., 2019). However, it is rare to see more extensive discussions of the active role of media organizations and media elites in securitization, such in Engelbert and Awad (2014) and Lorenzo-Dus and Marsh (2012). A discussion of the role that digital media platforms play within the processes of securitization is rarely analyzed (e.g., Chouliaraki and Georgiou, 2017). Literature offers works where cyberspace is considered a referent object of securitization (e.g., Christou, 2019). Cascading network activation of framing highlights the level of media, where media-elites, other important media gate-keepers, and other journalistic professionals exercise a degree of influence, through which frame elements are subdued or emphasized (Entman, 2003). Thus, cascading activation stipulates an analytical tool, which can significantly enrich the understanding of the process of securitization. Specifically, cascading activation can provide an insight into what happens as a securitized frame is processed through the mass media level before arriving to the target audience.

When discussing contemporary media theory, there are some arguments that the theoretical frameworks may have to be revamped to fully account for emerging media technologies and platform, which in some cases alter the nature of experiences, effects, or normative implications beyond the specifications that the older theories describe (Bennett and Iyengar, 2010; Holbert et al., 2010; Ward and Wasserman, 2010; Ward, 2014; Aruguete and Calvo, 2018). Analogously, Entman and Usher (2018) acknowledge that with the development of new digital media platforms, some previously proposed models—including cascading activation—must be revisited and updated. The authors assert that the cascading activation still provides an important explanatory tool, as even in the environment of digital media platforms, elite figures such as top level politicians have an upper position within the cascade. While many citizens now enjoy more opportunities to voice their opinion thanks to social media and other products of digital technologies, the citizens still cannot rival the agenda-setting power of elites and mainstream media. Yet, for certain strata of the population, the influence of elite or mainstream media over the agenda decreased through what Entman and Usher label as “pump-valves” (p. 298) that redirect the stream of frames through the cascade. Examples of the pump-valves include ideological media or rogue actors. It is yet to be explored what such pump-valves of framing do when intersecting with a securitization process.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity to explore the above outlined quandaries. The measures that were implemented across different global societies were already identified as cases of securitization by pundits and researchers (Al-Sharafat, 2020; Eves and Thedham, 2020; Krasna, 2020; Sears, 2020). Hence, the pandemic offers a natural laboratory of cases with various characteristics (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cascading activation of securitization. Elite-conceived security master frame passes through the cascading activation process [based on works of Buzan et al. (1998) and Entman (2003)].

An important theoretical and ethics related discussion that is occurring in connection to securitization within the health sector addresses the normative dimension—or simply put the questions on whether it is right or wrong to securitize health (Roemer-Mahler and Elbe, 2016). Authors document serious ethics issues (e.g., Youde, 2008) as well as compelling cases for normative strengths that stem from health securitization (e.g., Aradau, 2004; Sjostedt, 2008). The perplexing normative deliberations around health securitization reflect a broader conversation on the ethicality of securitization. The work of Floyd (2011, 2019a) articulates a just securitization theory, which is inspired by the just war theory. As Floyd stresses, the theory should be informed by other relevant ethics frameworks to define when a case of securitization is right vs. wrong. According to Floyd's work, justice within securitization is determined by certain key factors such as; a presence of a real existential threat, a just referent object, the appropriate motivations of the securitizing actor, an appropriate form of countermeasures against the threat, the reasonable chances of success of the measures, and appropriate termination of the securitization. It has not yet been described through any empirical studies whether and how the normative aspects of securitization debate occupy any prominent position through the framing process as it happens in practice.

Analytical studies can provide insights into whether the discussions on just vs. the unjust character of the securitization of COVID-19 emerge within the multilevel cascade of framing that functions as a stream of securitized discourse. Hence, the first research question guiding this specific analysis aims:

RQ1: How does the “moral evaluation” frame element factor into framing and reframing of securitization of the COVID-19 pandemic?

It also remains curious how the phenomena of (a) the cascading activation of framing, (b) the contemporary platforms such as digital media, and (c) the securitization processes collide. COVID-19 offers a massive depository of case studies where such intersections transpire. Therefore, to narrow the focus, this study hones in on potential rogue actors (Entman and Usher, 2018), so those who are likely to use digital platforms for the advancement of adversarial frames:

RQ2: How do certain controversial actors (or rogue actors) intersect with the framing process of securitization of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Lastly, the article's author hopes that a byproduct of the analysis can supply useful insights for a plethora of practitioners who address processes around the pandemic or some similar problems.

Analyses

Approach to Analysis and Tools

The analysis of the framing process is the main tool for this exploration. This is accomplished by looking at three different cases, where each offers a noteworthy deeper look into a specific level of the Entman (2003) framing cascade: (a) the elite, (b) the media, and (c) the public. Entman and Usher (2018) propose an update to the model for situations where the framing streams separate as differing ideological pump-valves redirect the framing to particular constituencies. The pump-valve concept is applied within this analysis as well. The systematic approach of analyzing a discursive unit through the lens of frame elements (Matthes and Kohring, 2008) enables tracking the component of moral evaluation in each line of framing that is encountered within every studied case.

The cases were selected based on media prominent controversies around COVID-19, and where it is possible to focus on a different level of the framing cascade. The analysis tracks reactions of radical factions within each context—thus, each context must include some type of possible rogue actors. The comparison of radically oriented groups and personalities offers an interesting cross-sectional look at a spectrum of counter-frames to the government's securitized measures in connection to the health crisis. The cases of Slovakia, Russia, and the US facilitate this type of exploration. It is vital to illuminate cases from a few different parts of the world, as COVID-19 is such a global phenomenon that insightful research can uniquely benefit from internationally eclectic studies. The specific materials that are analyzed include various relevant artifacts that are available, such as news stories, politicians' speeches, press releases, published analytical works, or content posted on the social media profiles of the relevant actors and groups.

Slovakia; Extra Focus on the Elite Level

The onset of the global crisis surrounding the pandemic of COVID-19 offers a plethora of illustrations of securitization. One such case is Slovakia initiating numerous emergency measures in mid-March 2020. Slovakia was among the first European Union (EU) nations to close borders to all non-residents. This means that the citizens of fellow EU nations could no longer enter. Slovakia belongs to the Schengen area of the EU, meaning before the COVID-19 measures were implemented, the borders would be completely abolished between the other Schengen countries. All this was dismissed due to COVID-19. Additionally, the government promptly imposed a number of restrictions such as business and school closings. Besides mandatory restrictions, the government asked for compliance with other non-mandatory but recommended measures, for example, an appeal to wear facemasks in public. While the set of practices was very unusual, and in some ways disruptive to the typical life in the small East-Central European country, the media and the public showed an intense degree of compliance with the securitization (Beblavy, 2020; Steno, 2020).

The cascading activation of framing model provides an insight into the successful securitization of the pandemic in Slovakia. During the onset of the crisis, the serving Prime Minister (PM)—the executive head of the government of the country—was Peter Pellegrini, who set the initial frame of securitization. Pellegrini has deliberately and consistently framed the situation as a type of “war” with existential repercussions. For instance, he remarked in his speech that the nation is in war and “we must win this war with as little losses as possible” (Pellegrini, 2020, p. n. d.). Other elites across the majority of the political spectrum have employed similar framing of the pandemic as an existential, war-like threat. Thus, the other elites have not contested the securitization of Pellegrini. The consensus proved to be particularly critical as just when the outbreak reached the country in March, the executive branch of the government was in the midst of a transfer of power between outgoing Pellegrini's cabinet and incoming Igor Matovic's cabinet. Media frames mirrored the elite consensus of defining the COVID-19 as an existential threat. So in the language of cascading activation, the frame remained uncontested in March as it was advancing down the cascade.

Yet, the political fights between the government coalition and the opposition are fierce in Slovakia, which tends to be the case within multiparty political establishments. While the defining of COVID-19 as a threat is not subjected to scrutiny within these fights, the measures began to be questioned. The main controversy as related to COVID-19 measures was PM Matovic's coalition's Act on Electronic Communication legislation passed on March 25, 2020. The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2020) writes on the content of the new legislation:

“…the data that are subject to telecommunications secrecy may be made available to the Public Health Authority at the time of emergency in the health service for the purpose of their collection, processing and preservation to the extent of necessary for the identification of natural persons in order to protect life and health.” (p. 12)

International reports also describe the law as a potential breach of commitments to democratic values and the individual rights of the citizens (Verseck, 2020). The members of the opposition, including the former PM Pellegrini, reacted by fervent disagreement with the law, primarily citing the normative concerns over liberties. The opposition politicians nickname the law as “špehovací zákon” meaning the “stalker law.” Finally, the oppositional members of the National Assembly appealed the law to the Constitutional Court of Slovak Republic (Ústavný Súd Slovenskej Republiky). On May 13th, 2020, the Court ruled the law conflicts with the country's Constitution and thus terminated its effectiveness (Barr, 2020). The prompt institutional reaction might have not prevented the questionable law from causing further fractures in the general trust that the broader public has in the system's response to COVID-19. This issue and the rise of online misinformation and disinformation campaigns contribute to increased diversion in the acceptance of government's securitization of COVID-19 throughout summer 2020.

Elite contestation of the current securitization frame was introduced by a far right-wing political leader Marian Kotleba, the head of the party LSNS, which received ~8% of the electoral support in the parliamentary election in February 2020. Thus, Kotleba can be considered an elite in a sense of a being leader of the National Assembly party, but he represents a limited segment of the population. His party does not enjoy an association with any significant allies and is rather a pariah on the Slovak political scene. Kotleba has a history of being a member of a militia style organization, the Slovak Brotherhood (Slovenská Pospolitost). In April, Kotleba published a YouTube video, where he offers criticism of securitization of COVID-19, and asserts that the key interpretation of the situation should be seen as an attempt of foreign powers to take over Slovakia and “enslave Slovaks” through economic means (Kotleba, 2020). Kotleba also adds a large dose of conspiratorial remarks including the infamous “microchip-infested vaccine” trope, which shifts his claims into a rather marginalized arena of conversation. Kotleba's contestation of the general frame was met with reluctant acceptance. Another high-profile member of LSNS, the European Union Parliament Member Milan Uhrik, evaluated Kotleba's statements with some degree of disagreement when asked during a podcast interview in May of 2020. Uhrik even laughed about Kotleba's idea of a nefarious mind-controlling microchip in the vaccine and remarked “it is not likely possible” (Uhrik, 2020, p. n. d). Kotleba's early interpretation of the situation fell short of offering a counter-frame to the strong normative claims of both Pellegrini and Matovic on the commitment to protect the elderly. Perhaps Kotleba's fear of economic enslavement could have served as a normative counterargument, but he does not make that assertion. Kotleba's counter frame was initially failing to build a necessary momentum to seriously challenge the dominant frame. However, during summer, Kotleba along with some rogue actors from among social media influencers continued questioning governmental policy and spreading counter narratives through the internet. Later in summer 2020, Kotleba centered more on specific arguments of alleged adverse health effects of facemasks and the protection of children from these threats. For instance, Kotleba claims “facemasks are harmful to human organisms due to carbon dioxide” (TV Noviny., 2020, p. n. d.). Facebook has blocked Kotleba's video due to complaints it represents a hoax. Notably, once Kotleba fortified the normative basis of his frame as a matter of freedom, protection of health, and protection of children, his appeals have started to become more popular. Indeed, more of LSNS members and sympathizers started joining Kotleba's calls to actions such as a refusal to wear facemasks (SME., 2020). Another high-profile LSNS member, Milan Mazurek, as well as Uhrik shared a Facebook post that contributes to the “protection of children” spin claiming that the policy of requiring preschoolers to wear facemasks is a product of “heartless hyenas” (Mazurek, 2020, p. n. d.).

Conversely, another active paramilitary organization was involved in the pandemic containment efforts in spring. The militia-style organization Branci—or Slovenski Branci (Slovak Defenders)—was in the past considered by some as a possible threat to the state's security (Turecek and Sabo, 2019). Yet, the organization seems to embrace the current state's securitization of the pandemic situation. Branci used their social media to show activities such as the distribution of groceries to the vulnerable elderly people, distribution of facemasks to the marginalized Romani people in impoverished slums, or training the practice of disinfection procedures. Furthermore, it is visible that the militia members are wearing facemasks and hand gloves during their spring photo ops that are shared via the organization's Facebook page (Slovenski Branci., 2020). Later during the summer, Branci started to stay away from the topic of the pandemic and focus on other issues. It appears that this group is attempting to step out of the shadow of being viewed as a rogue. Branci's normalization attempts are backed up by an important sponsor—the organization is a protégé of Jan Carnogursky, a former PM of Slovakia (Turecek and Sabo, 2019; Carnogursky, 2020).

The general bulk of citizens has thus far complied with both mandatory and requested measures, and as of early summer 2020, Slovakia has belonged to the countries with one of the most contained COVID-19 outbreak on a global level (Beblavy, 2020).

It is also important to remark that just as Entman and Usher (2018) foresee, certain aspects of cascading activation remain powerful even within the environment of widely used and popular alternatives and social media platforms. This is reflected in the fact that popular Pellegrini's Facebook videos, including ones on COVID-19, reach as many as 700 thousand views (Slovakia is a country of ~5.4 million inhabitants). Hence, the elites are on the top of the hill of the metaphorical framing cascade. However, the influence of far right political elites and online rogue actors in impacting the frame should not be dismissed. While only 11.1% of Slovaks was reporting unwillingness to wear facemasks in April, it increased to 35.4% in September of 2020 (Habas, 2020), which is a number that far exceeds the electoral support of Kotleba. Hence, the decreasing compliance among Slovaks is likely to be related to a more complex set of factors, where the influence of other rogue actors might play a role that should be explored by future research. Still, it is important to consider ripple effects of ruptured public trust in the administration due to missteps such as PM Matovic's “stalker law,” which also might play a role in weakening the compliance with counter pandemic measures.

Russia; Extra Focus on the Media Level

Russia represents a case where the elites are fairly consolidated after two decades of the rule of President Vladimir Putin (between the years 2008–2012 Dmitry Medvedev was the President, but Putin remained vitally influential as the Prime Minister during that period). Putin has experienced numerous crises of varying degrees of intensity including armed conflicts, terrorism, civil unrest, devastating wildfires, and economic sanctions. Besides other crises, Russia deals with public health related problems, which are common for nations of such size and a recent history of political transition. In the past, Putin's administration has securitized the HIV-AIDS pandemic (Sjostedt, 2008), which shows that the elites have utilized the securitization frame to justify novel measures to mitigate a health problem.

With the outbreak of COVID-19, Russia has also adopted broad restrictive measures. Although, Putin has not utilized existential threat framing of the situation with COVID-19, nor has he used an outright “war” assertion, unlike Pellegrini. In his April 28, 2020 speech, Putin describes the pandemic as a “threat” and a “danger,” but he does not specify this is a threat of an existential dimension, and therefore it cannot be considered a pure example of straightforward securitization. Putin further asks the citizens for “discipline and mobilization” as “the more careful we will be within the next few days, the faster we can return to the normalcy” (Putin, 2020, p. n. d.). Thus, Putin leaves the interpretation of the situation somewhat ambiguous and keeps his own remarks agreeable and general enough. This might be a deliberate strategy of Putin to allow himself a maneuver space if certain policies do not work out well. Some critics of the President allege that Putin's typical strategy is to associate his name with successful projects and “scold” other officials for failed projects. But more insights can stem from an examination of the media framing of the situation—particularly how the media elites retell or expand the frame.

Russia serves as an interesting case to consider in connection to the media level framing, especially as certain Russian media elites are considered imperative opinion setters and influencers. An important media elite figure is Vladimir Solovyov, who hosts a popular nightly show on Russian federal television as well as a daily online podcast show. Solovyov is a vocal supporter of Putin and his policies, and he employs a particularly confrontational style during interviews of his guests, which leads some critics to label him the regime's lead propagandist. Solovyov is also identified as an influential media agenda-setter; for example, he started to frame the Russian response to the Ukrainian crisis through an ethno-nationalist perspective before Putin started employing that specific frame (Tolz and Teper, 2018).

In spring and early summer 2020, Solovyov has offered extensive time to coverage of COVID-19 and still periodically remarks on the pandemic. Throughout Solovyov's narrative, he characteristically expresses trust in Putin administration's response and management of the pandemic. In terms of normative aspects, he uses the situation to reassert the superiority of the value system, which he believes is characteristically intrinsic for Russia. For example, on July 7th, Solovyov proclaims that COVID-19 helps to demonstrate that the Western assertion of freedom as the major value is wrong (Solovyov, 2020). His guest reminds Solovyov that the mainstream Western conception defines one's freedom as ending exactly where another one's freedom begins, and thus the needs of practicing social distancing to prevent the spread of disease still fit well within the Western framework on the superiority of liberty. To this assertion, Solovyov responds highlighting that it is not about where another individual's freedom begins, to him it is more about the benefit of the society as a whole. Further, Solovyov explains his argument as based on Russia's cultural commitment to a more collectivism-inspired hierarchy of values. This type of argumentation is usual for Solovyov; philosophical deliberations are common for his shows.

Several other media elites appear on Solovyov's shows as pundits. For further analysis, the focus is on some specific individuals from among those pundits who, besides Solovyov's show, have an additional high profile legacy media or social media presence and an established track record of attempts to influence the public agenda, even if it involves some radical actions. First, one such media elite pundit is Sergei Kurginian (another version of English spelling of his name is Sergey Kurginyan). Besides frequently appearing on Solovyov's Sunday show, Kurginian is a well-known commentator (Lichtenstein et al., 2019). He appears on federal media and also on the YouTube channel of his Marxist-nationalist organization Sut' Vremeni. This organization includes a paramilitary wing and was involved in the war in Eastern Ukraine, which started in 2014. On the Sut' Vremeni channel, Kurginian stars in a series of lectures on the geopolitics of COVID-19. Through these lengthy narratives, Kurginian offers a number of alternative accounts including certain conspiratorial versions. However, the dominant reoccurring common frame of his interpretation asserts the necessity for reemergence of Russia as a global leader to advance new articulations of the Marxist-Leninist philosophy. One episode of Kurginian's series prominently uses a phrase “arise, vast country,” which is a line from the famous WWII song “Sacred War” (Kurginian, 2020). So Kurginian alludes to the paramount Russian national myth, which is deeply rooted in commemoration of the WWII victory (Khrebtan-Horhager, 2016). In the atmosphere of the celebration for the 75th anniversary of the defeat of the Nazi Axis, the topic is particularly relevant. For Kurginian, the country needs to arise now to face the broader threat of the anti-humanist capitalist system, which is trying to gain advances through the exploitation of COVID-19. Hence, Kurginian twists the pandemic crisis to further reaffirm the exceptionalism of Russia. Also, he proclaims his usual point of the moral decline of capitalism. Kuginian's perspective is representative of one whole line of reasoning among recognizable Russian media personalities, which is cooption of COVID-19 toward an argument of proving the previously advocated points. Some pundits like Kurginian and famous filmmaker Mikhalkov (2020) develop more conspiratorially leaning ideas than Solovyov who is fully supportive of the official government's line of explanation and action.

The second illustrative type of pundit is the writer Zakhar Prilepin. His background includes a successful career of fiction writer, pro-nationalist activism, and involvement in paramilitary warfare on the side of pro-Russian irredentists for the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic in Eastern Ukraine (Laruelle, 2019). His public influence has been increased by Prilepin's membership in the official state committee that worked on the Amendments to the Russian Constitution in 2020. Prilepin appears on federal media channels as host, interviewee, and additionally, much of this content is also available on digital platforms such as YouTube. Two spring episodes of the show that he hosts for the federal-reaching channel NTV, titled “Russian Lessons,” were devoted specifically to COVID-19. Prilepin proposes that pandemics are occurrences that periodically plight societies. However, Prilepin stresses that the society is not likely to change due to this difficult situation and it is crucial to focus and work toward what according to him is essential for Russians; “honor, family, children, dignity, motherland, nation, kin, and God” (Prilepin, 2020, p. n. d). Thus, Prilepin challenges the definition of a problem amid the securitization. For him, the normative hierarchy predetermines what needs to be the central focus of attention instead of the focus on the pandemic.

The individuals like Kurginian and Prilepin are at times criticized as tolerated or even “controlled” opposition in Russia. An example of an outside-of-the-system critic of the government is Igor Girkin, also well-known under the nom-de-guerre Strelkov (Laruelle, 2019). He is considered to be the best known Russian warlord, who took part in several armed conflicts in and outside of Russia, including most recently in the war in Eastern Ukraine. He uses alternative media options such as the internet and social media to present his views. There he ridicules the government's measures around COVID-19 and makes derogatory statements about people who wear masks. He expresses displeasure that many Moscow residents wear masks. Girkin (2020) asserts he refuses to wear a mask because it is “cowardly.” Overall, he does not provide any alternative course of action. His somewhat grumpy criticism is resembling the early iteration of Slovak Kotleba's underdeveloped frame without coherent ethical reasoning, rather than the more robustly crafted normative arguments of his Russian rivals Prilepin or Kurginian. As Laruelle (2019) observes, Girkin generally tends to present positions that are adversarial toward Putin's government, but currently Girkin does not possess a massive public influence and thus hardly represents a true challenger to the regime, so the authorities let him roam and talk. His weak COVID-19 counter-frame is an example of rogue media diversion, but it will hardly mobilize any masses—at least not in any foreseeable future.

The scrutinized Russian media personalities' reactions to the pandemic either support the government or offer an indirect or laconic criticism. It is important to note that the government imposed a strict anti-hoax policy, which criminalizes “COVID-19 dissidents.” That may be an explanation why the reframing attempts must be sandwiched between long hours of commentary as Kurginian does, or just described as less significant issues than others as Prilepin does. The ideological pump-valves are actively at work within the Russian media-sphere, while still playing the game safe enough within the rules as determined by the system of “managed democracy” in the country. The Russian pump-valve operators (the pundits) frequently develop augments based on moral evaluations and normative reasoning. Various segments of Russian society can find their niche among the media personalities' camps. The analysts and practitioners focusing on pandemic-related communication in Russia should pay attention to how the influence patterns of Russian political and media communication work. An extensive understanding of the culturally appealing themes and the public communication system with its logic is crucial. For instance, the WWII narratives play a more significant role in Russian framing of COVID-19 than would be true in other countries, but missing such an important component may weaken a broader campaign.

United States; Extra Focus on the Public Level

In Slovakia and Russia, the elevation of COVID-19 to the high salience of public interest was accompanied by a rather coherent narrative on the issue and relative elite agreement on the main interpretations. The onset of the pandemic was accompanied by more perplexing political communication in the US. Initially, President Donald Trump has made several statements that can be interpreted as normalizing the disease by comparing it to a common cold for instance (Brooks, 2020). However, Trump and his administration have also adopted a type of securitized framing, particularly when the pandemic had begun to occupy the main public agenda in March 2020. Specifically, Trump and some of his high officials started to compare the situation to war, but in a sense of economic security and/or security against an external threat, specifically China (Hansen, 2020). The Chinese Communist party is frequently framed as the key enemy culprit, which aligns with the culturally congruent demonization of Communism that happened during the decades of the Cold War (Herman and Chomsky, 1988). The left of the American political spectrum has been generally calling for more robust containment measures. One of the gravest normative issues raised across the public conversation addresses the problematic tendency of dismissing the concerns for those who are more vulnerable to severe consequences of the illness—who are disproportionately more likely to be the elderly and people of color (Harrington, 2020). Raising concerns that ageist, racist, and also classist tendencies are at play, leads to rather intense conflicts within the American political arena and general public communication sphere.

The elite cleavages within the US were quickly woven into the framing competition over COVID-19. This is very interesting in the sense that various securitizations are happening on the elite level and can be seen transferred into the media discourse, along with the track of ideologically informed pump-valves (Entman and Usher, 2018). The conflicting securitization discourses are perplexed as different states of the US implement not just different measures, but also different framings surrounding the measures.

Certain radical grassroots organized events and actions in the US have reached a level of national and even international attention. An internationally covered event was a protest in Michigan, which gained notoriety as several men with firearms and paramilitary gear entered the building of the State Capitol (Beckett, 2020). The visuals of the event resembled an armed takeover of a government administration building, which can be comprehended as an act of insurgency. The organization behind the protest is a small local group, Michigan Liberty Militia. The leader of the organization, Phil Robinson, denied any attempt of militancy or coup-oriented activity (The Vegas Take., 2020). The guns, in their view, guarantee the peacefulness of the assembly. On their social media accounts and in interviews for legacy media, the Michigan Liberty Militia have reasserted they just want to exercise their right to peacefully protest to show disagreement with the extent of COVID-19 measures as ordered by the Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. The group and sympathizing social media profiles strongly criticize the Governor; some would even go as far as to share meme material that equates Whitmer to Adolph Hitler. The core argument by the group affiliates reflects on their interpretation of the normative basis of the individual rights and liberties as guaranteed by the US Constitution [Michigan Liberty Militia (MLM), 2020].

The Michigan Liberty Militia is a relatively small organization. However, its positions resonate with a broader subgroup of the American public, who are gathered in numerous organizations, including paramilitary types of groups (Southern Poverty Law Center., 2019). The one unifying sentiment is strong anti-government attitudes. For some of them, the popular normative argument is a strong adherence to libertarian oriented privileging of individual freedoms. This narrative was present in several protests against the COVID-19 measures across the US. The Lansing City Pulse (2020) documented that Robinson and other members of his group did personally know at least a few of the men who were arrested for suspected domestic terrorism conspiracy in October 2020. The charges against the obscure militia organization Wolverine Watchmen include alleged plans to kidnap Governor Whitmer, attack police officers, and bomb a bridge (Baldas and Egan, 2020).

Other extremely radical actions on behalf of the liberty stressing American movements, but also on behalf of extreme right-wing tendencies, are attributed to the online movement Boogaloo. This is a relatively new movement that has emerged on the darknet within the last decade, and later has grown to a social media meme of the regular internet, inspiring different groups of like-minded individuals across the web (Finkelstein et al., 2020). Boogaloo incorporates several different political lines of thinking, but the shared orientation embraces anti-government, anti-police, pro-gun, and pro-White supremacy ideology. The goal of the group is to start a civil unrest, even a civil war, to use the violence for advancing their demands and taking revenge on ideological enemies. Boogaloo sympathizers have been photographed at protests against stay-at-home orders and other COVID-19 containment-related measures. Some Boogaloo affiliates saw the COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity to spread fear and chaos. FBI has intercepted and killed a Boogaloo sympathizer, who was planning a bomb terror attack against a hospital in Missouri on the first day of the pandemic containment stay-at-home order (Pineda, 2020).

Hence, in the US, several ideologically motivated organizations find the securitization of COVID-19 as highly antagonistic to their value system, which they quickly pointed out—some by just reframing the crisis via social media, others by protests, and others by acts of violence. COVID-19 is also co-opted to advance a particular cause, as in the case of Boogaloo. Similarly, Boogaloo tried to exploit the Black Lives Matter protests to entice more violence. When Boogaloo sympathizers were arrested as main suspects in the ambush murders of a US Federal Officer and California Sherrif's Sergeant, the organization finally reached visibility in the mainstream US media coverage (Pineda, 2020; TASR., 2020). Perhaps due to a broader pressure of public attention, Facebook and Instagram blocked hundreds of social media groups and profiles affiliated with Boogaloo in late June (Collins and Zadrozny, 2020). The issue is that this will be unlikely to serve as a long term solution. While a specific set of networks and connections was severed (for now), the volatility of further problems continues to exist and is likely to continue to grow and find new ways to exploit contemporary technologies as well to manipulate situations such as securitization surrounding COVID-19. Finkelstein et al. (2020) warn:

“civil society should seek to enfranchise an effort to create trusted, systematic reporting on these kinds of emerging threats at scale…this approach has the promise to prove more effective and more consistent with First Amendment values than the approach of either excessive censorship—which has limited effectiveness—and over-reach in government surveillance, both of which carry risk of feeding into suspicion of totalitarianism that fuels the militia sphere itself.” (p. 12)

The above-cited concerns draw attention to the significance of the normative element within an extremist movement privileging a particular hierarchy of values. For Boogaloo the uppermost values reflect libertarianism with pronounced streaks of White supremacy. Their interpretations of the normative frameworks pose a direct opposition to the current nation-state of the US. Thus, securitization of COVID-19 represents an ideological issue for these factions, and the more extreme ones were apparently ready to go as far as terrorism to defy it.

Rogue actors have activated their pump-valves with fervor in the case of the US. Other countries with comparable extreme factions may need to pay attention to the case. Boogaloo groups were housing tens of thousands of users on Facebook (Finkelstein et al., 2020). It is important to highlight that this platform is an international site. Cross-contamination might have already happened. Unfortunately, the case of Slovenski Branci in Slovakia may not serve as a useful universal recipe to keep militias harmless or even useful, because the Slovak organization is fundamentally different and statist in its core normative values, and does not pledge an apocalyptic desire to provoke a civil war. Henceforth, the members of Branci prioritize the defense of the state against the microbiological enemy, while Boogaloo figuratively collaborates with the microbiological enemy to take down the despised state.

Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

The current analysis focuses primarily on breadth in terms of both theoretical grounding and analyzed cases. Consequently, deterministic in-depth conclusions cannot be made solely based on observations that are offered in this analysis. It is recommended that future researchers develop additional comparative and empirical studies of COVID-19 related securitized framing. New projects can build on descriptions provided in this piece and further explicate the situations in different countries and across diverse securitized and non-securitized responses to the pandemic. Also, new studies can deliver additional reflections on processes that happen along with various levels of the metaphorical framing cascade.

While this study offers some succinct remarks of comparison between the three illuminated cases, it should not be treated as a primarily comparative study. The selected cases have an extensive number of differences. Plus, the focus was shifted toward a different level of the cascading activation of framing in each case. Therefore, the analogies can and hopefully will inform further research inquiries, but should not be taken as a definite verdict on why particular things happened or failed to happen.

The COVID-19 crisis is still evolving as this article is written. All outcomes have not yet fully formed. Hence, the article should be taken as a useful cross-sectional insight into the stage of development of the securitized framing of the pandemic as of the time of the article's submission to the publisher. Follow-up research is paramount to grasp the events in an additionally precise way, specifically once the crisis ends, and researchers can enjoy the irreplaceable benefits of hindsight.

Conclusion

COVID-19 is met by political and media communication as well as by a range of response measures that can be described as securitization. The study presented in this article offers securitization process analysis, which utilizes the communication perspective of framing as the principal mode of exploration. Therefore, this study offers a systematic look into pandemic securitization, while also advancing the role that framing, and communication inquiry in general, should play in an examination of securitization processes. The argument for championing framing is not a mere “disciplinary chauvinism” as the author is a communication academic, but the fact that the securitization process is, as the key Copenhagen School's definition characterized it, a “speech act.” Thus, communication research must continue to play a role in illuminating the very phenomenon of securitization. Communication is a vital component behind securitization processes. Further comprehension of communication within securitization provides a more precise and profound description of the phenomenon. The development of knowledge brings benefits not just for knowledge's sake, but also for the work of practitioners. In the case of COVID-19, political administrators, strategic communication professionals, or journalists, among others, can find useful information for their work through a better understanding of securitized framing, as it offers an explanation for how certain types of persuasion work for certain persuaders and certain target segments of the public. For instance, successful counterstrategies might need to properly assess and incorporate a securitization related element in a campaign.

The first research question of this inquiry explores whether and how the frame element of moral evaluation factors into the conversations on the securitization of the pandemic. The normative aspects of the securitization are a growing subarea of the pertinent academic literature. This analysis is unique in exploring the actual framing process as it traverses through elite, media, and public levels of communication on the topic. The analysis demonstrates that morals and values were discussed in each case but to a varying degree. One prominently shared theme of the normative dimension that occurs in Slovakia, Russia, and the US involves discussion on the ethical tensions between individual's liberties and freedoms on the one hand vs. collective responsibility and loyalty to the government on the other hand. However, the interpretations, preferences, and conclusions significantly differ for various factions and each studied context. The previously existing sociopolitical idiosyncrasies and issues robustly impact how the responses to COVID-19 securitization advance. Therefore, the politicians, public health professionals, and other relevant professionals must be particularly well-educated and informed about deep-rooted characteristics of the specific culture and the state's situation.

The second main research question determined that the analysis focused on fairly controversial actors; rogue actors. The progress of digital media technologies has given numerous new opportunities to various actors to get involved in publicly visible conversations on critical issues such as the pandemic. As the analysis demonstrates, the studied rogue actors usually have at least something to say about COVID-19, and frequently make some evaluations of how moral or normatively appropriate is their respective government's “war” on COVID-19. Securitization research usually does not explore securitizing attempts of obscure or regular citizen actors as these types of actors were initially envisioned as not having enough social credit to be able to securitize. However, when it comes to enterprises such as terrorism, a rogue actor does not necessarily need a massive number of supporters or—for that matter—online subscribers. The ability of the persuasive message to radicalize a few specific individuals is more vital for extremist projects. Interestingly, COVID-19 has become a paramount trigger for some radically oriented groups and individuals, as well as for some outright violent extremists.

This study aspires to connect various bodies of literature by applying the intersecting areas as a lens of analysis to examine three different cases. In other words, it is a cross-disciplinary and cross-case analysis. This type of analysis is not common, but they are crucial for advancing connections between separated bodies of knowledge. Real phenomena in the world, like a pandemic, are not purely biological, nor purely political, nor purely discursive, etc. Phenomena have many different dimensions that are interconnected in many different ways. The ability of researchers and practitioners to embrace this diverse nature of world phenomena will predict the degree of understanding and consequently the level of effectiveness of the responses that societies can perform in reaction to new challenging situations.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author is immensely grateful to Deborrah Uecker (Professor Emerita at Wisconsin Lutheran College) for providing feedback on the draft. The author also deeply appreciates constructive feedback and suggestions from the reviewers and editors.

References

Allouche, J., Nicol, A., and Mehta, L. (2011). Water security: towards the human securitization of water? Whitehead J. Dipl. Int Rel. 12, 153–171.

Al-Sharafat, S. (2020). Securitization of the Coronavirus Crisis in Jordan: Successes and Limitations. Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/fikraforum/view/COVID-19-Jordan-Middle-East-Securitization

Aradau, C. (2004). Security and the democratic scene: desecuritization and emancipation. J. Int. Relat. Dev. 7, 388–413. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800030

Aruguete, N., and Calvo, E. (2018). Time to #protest: Selective exposure, cascading activation, and framing in social media. J. Commun. 68, 480–502. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqy007

Baele, S. J., and Thomson, C. P. (2017). An experimental agenda for securitization theory. Int. Stud. Rev. 19, 646–666. doi: 10.1093/isr/vix014

Baldas, T., and Egan, P. (2020). Feds Say Plot was Bigger Than Kidnapping Gov. Whitmer. It was a Civil war Attempt. Detroit Free Press. Retrieved from: https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/2020/10/08/whitmer-wolverine-watchmen-militia-michigan/5924617002/?fbclid=IwAR0FrjmQIoucNwXgDQK4pQwEgs-oex8OqPSdG8dp1M4IFxzazc03QyfN2FI

Barr, L. (2020). Boogaloo: The Movement behind Recent Violent Attacks. ABC News. Retrieved from: https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/boogaloo-movement-recent-violent-attacks/story?id=71295536

Beblavy, M. (2020). How Slovakia Flattened the Curve. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/06/slovakia-coronavirus-pandemic-public-trust-media/

Beckett, L. (2020). Armed Protesters Demonstrate Against Covid-19 Lockdown at Michigan Capitol. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/30/michigan-protests-coronavirus-lockdown-armed-capitol

Bengtsson, L., Borg, S., and Rhinard, M. (2019). Assembling European health security: Epidemic intelligence and the hunt for cross-border health threats. Sec. Dialog. 50, 115–130. doi: 10.1177/0967010618813063

Bengtsson, L., and Rhinard, M. (2019). Securitization across borders: the case of ‘health security’ cooperation in the European Union. West Eur. Polit. 42, 346–368. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1510198

Bennett, W. L., and Iyengar, S. (2010). The shifting foundations of political communication: responding to a defense of the media effects paradigm. J. Commun. 60, 35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01471.x

Bourbeau, P. (2014). Moving forward together: Logics of the securitization process. Millen. J. Int. Stud. 43, 187–206. doi: 10.1177/0305829814541504

Brooks, B. (2020). Like the Flu? Trump's Coronavirus Messaging Confuses Public, Pandemic Researchers Say. Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-mixed-messages/like-the-flu-trumps-coronavirus-messaging-confuses-public-pandemic-researchers-say-idUSKBN2102GY

Buzan, B., and Waever, O. (2009). Macrosecuritization and security constellations: reconsidering scale in securitization theory. Rev. Int. Stud. 35, 253–276. doi: 10.1017/S0260210509008511

Buzan, B., Waever, O., and de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Pub

Carnogursky, J. (2020). Slovenskí Branci 2020. O Súčasnosti; Ján Carnogurský Weblog. Retrieved from: http://www.jancarnogursky.sk/clanky/189/slovensk-branci-2020

Chouliaraki, L., and Georgiou, M. (2017). Hospitability: the communicative architecture of humanitarian securitization at Europe's borders. J. Commun. 67, 159–180. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12291

Christou, G. (2019). The collective securitization of cyberspace in the European union. West Eur. Polit. 42, 278–301. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1510195

Collins, B., and Zadrozny, B. (2020). Facebook to Remove Anti-Government ‘Boogaloo’ Groups. NBC News. Available online at: https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-remove-anti-government-boogaloo-groups-n1232579?fbclid=IwAR387b_Pk7DYc_NFJQSbH2ispOuUqrVUDVy7lBTtzTtMegyjRZMYsUv9pDo

D'Angelo, P. (2002). News framing as a multiparadigmatic research program: a response to Entman. J. Commun. 52, 870–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02578.x

Engelbert, J., and Awad, I. (2014). Securitizing cultural diversity: dutch public broadcasting in post-multicultural and de-pillarized times. Glob. Media Commun. 10, 261–274. doi: 10.1177/1742766514552352

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Entman, R. M. (2003). Cascading activation: contesting the white house's frame after 9/11. Polit. Commun. 20, 415–432. doi: 10.1080/10584600390244176

Entman, R. M., Matthes, J., and Pellicano, L. (2009). “Nature, sources, and effects of news framing,” in Handbook of Journalism Studies, eds K. Wahl-Jorgenson and T. Hanitzsch (New York, NY: Routledge), 175–190

Entman, R. M., and Usher, N. (2018). Framing in a fractured democracy: Impacts of digital technology on ideology, power and cascading network activation. J. Commun. 68, 298–308. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqx019

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2020). Coronavirus COVID-19 Outbreak in the EU Fundamental Rights Implications. Slovakia. Retrieved at https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/slovakia-report-covid-19-april-2020_en.pdf

Eves, L., and Thedham, J. (2020). Applying Securitization's Second Generation to COVID-19. E-International Relations. Retrieved from: https://www.e-ir.info/2020/05/14/applying-securitizations-second-generation-to-covid-19/

Finkelstein, J., Donohue, J. K., Goldenberg, A., Baumgartner, J., Farmer, J., Zannettou, S., et al. (2020). COVID-19, Conspiracy and Contagious Sedition: A Case Study of the Militia-Sphere. Network Contagion Research Institute. Retrieved from: https://ncri.io/reports/covid-19-conspiracy-and-contagious-sedition-a-case-study-on-the-militia-sphere/

Fischhendler, I., Boymel, D., and Boykoff, M. T. (2016). How competing securitized discourses over land appropriation are constructed: the promotion of solar energy in the Israeli desert. Environ. Commun. 10, 147–168. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.979214

Floyd, R. (2007). Towards a consequentialist evaluation of security: Bringing together the Copenhagen and the Welsh Schools of security studies. Rev. Int. Stud., 33, 327–350. doi: 10.1017/S026021050700753X

Floyd, R. (2011). Can securitization theory be used in normative analysis? towards a just securitization theory. Sec. Dialog. 42, 427–439. doi: 10.1177/0967010611418712

Floyd, R. (2016). Extraordinary or ordinary emergency measures: what, and who, defines the ‘success’ of securitization? Camb. Rev. Int. Affairs 29, 677–694. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2015.1077651

Floyd, R. (2019a). Collective securitization in the EU: normative dimensions. West. Eur. Polit. 42, 391–412. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1510200

Floyd, R. (2019b). Evidence of securitization in the economic sector of security in Europe? Russia's economic blackmail of Ukraine and the EU's conditional bailout of cyprus. Eur. Sec. 28, 173–192. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2019.1604509

Girkin, I. (2020). Игорь Стрелков по "обнулению" Путина и голосованиям по поправкам в Конституцию РФ [Igor Strelkov on “Zeroing” Putin and Voting on Amendments to the Constitution of the Russian Federation]. Игорь Стрелков. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lp9pSzjL038

Gitlin, T. (1980). The Whole World is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Habas, J. (2020). Prieskum; Ochota Ludí Nadalej Nosit Rúška Klesla [Poll; People's Willingness to Continue to Wear Facemasks Decreased]. SME. Retrieved from: https://domov.sme.sk/c/22487344/koronavirus-na-slovensku-nosenie-rusok-prieskum.html

Hansen, S. (2020). Trump Suggests China May Have Intentionally Allowed Coronavirus to Spread. Forbes. Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sarahhansen/2020/06/18/trump-suggests-china-may-have-intentionally-allowed-coronavirus-to-spread/#3a8080ea33f1

Harrington, C. N. (2020). Opinion: Poor, Older Black Americans are an Afterthought in the COVID-19 Crisis. PBS. Retrieved from: https://www.pbs.org/wnet/chasing-the-dream/stories/opinion-poor-older-black-americans-afterthought-covid-19/

Hart, C., Jin, D. Y., and Feenberg, A. (2014). The insecurity of innovation: a critical analysis of cybersecurity in the United States. Int. J. Commun. 8, 2860–2878.

Holbert, R. L., Garrett, R. K., and Gleason, L. S. (2010). A new era of minimal effects? A response to Bennett and Iyengar. J. Commun. 60, 15–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01470.x

Inouye, D. W. (2005). “Biodiversity and ecological security,” in From Resource Scarcity to Ecological Security: Exploring New Limits TO Growth, eds D. Pirages and K. Cousins (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 203–215.

Kelle, A. (2007). Securitization of international public health: Implications for global health governance and the biological weapons prohibition regime. Glob Govern. 13, 217–235. doi: 10.1163/19426720-01302006

Khrebtan-Horhager, J. (2016). Collages of memory: Remembering the second world war differently as the epistemology of crafting cultural conflicts between Russia and Ukraine. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 45, 282–303. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2016.1184705

Kotleba, M. (2020). M. Kotleba: Koronavírus ako Zámienka na Zotročenie Ludí (15. 4. 2020) [M. Kotleba; Coronavirus as a Means to Enslave People (4/15/2020)]. LS Naše Slovensko v NR SR. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbHOWit8wdE&fbclid=IwAR2QO8GWArhCwqb2ImoHb9Aheh4o19q5MwKrGFS1bo6xKHONbE_wKLWbP40

Krasna, J. (2020). Securitization and Politics in the Israeli COVID-19 Response. Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/04/securitization-and-politics-in-the-israeli-covid-19-response/

Kurginian, S. (2020). Кургинян о коронавирусе: почему врачи гибнут от covid 19, а Россия спит? Вставай, страна огромная [Kurginian About Coronavirus: Why Doctors Die of COVID-19, and Russia Sleeps? Arise, Vast Country!]. Суть времени. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFjGTvY-Cmo

Lansing City Pulse (2020). Alleged Whitmer Plotters had Interactions, Ties to Other Militias. Lansing City Pulse. Retrieved from: https://www.lansingcitypulse.com/stories/alleged-whitmer-plotters-had-interactions-ties-to-other-militias,15057

Laruelle, M. (2019). Back from utopia: how Donbas fighters reinvent themselves in a post-Novorossiya Russia. Natl. Pap. 47, 719–733. doi: 10.1017/nps.2019.18

Leonard, S. (2010). EU border security and migration into the European union: FRONTEX and securitization through practice. Eur. Sec. 19, 231–254. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2010.526937

Lichtenstein, D., Esau, K., Pavlova, L., Osipov, D., and Argylov, N. (2019). Framing the Ukraine crisis: a comparison between talk show debates in Russian and German television. Int. Commun. Gazette 81, 66–88. doi: 10.1177/1748048518755209

Lorenzo-Dus, N., and Marsh, S. (2012). Bridging the gap: interdisciplinary insights into the securitization of poverty. Discour. Soc. 23, 274–296. doi: 10.1177/0957926511433453

Maertens, L. (2019). From blue to green? Environmentalization and securitization in UN peacekeeping practices. Int. Peacekeeping 26, 302–326. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2019.1579648

Matthes, J., and Kohring, M. (2008). The content analysis of media frames: toward improving reliability and validity. J. Commun. 58, 258–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00384.x

Mazurek, M. (2020). Milan Uhrik: Takéto Opatrenie Môzu Nariadit Len Bezcitné Hyeny! [Sic Capitalization] [Milan Uhrik: This Type of Measures Can be Ordered Only by Heartless hyenas!] Milan Mazurek - Poslanec NR SR @MilanMazurek. NRSR Politician. Retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/MilanMazurek.NRSR/posts/826179748152254

Michigan Liberty Militia (MLM), (2020). Facebook Page. Retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/MLMmichiganlibertymilitia/ (accessed May 8, 2020).