94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 19 November 2020

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.583294

This article is part of the Research Topic Team and Leader Communication in the Healthcare Context: Building and Maintaining Optimal Transdisciplinary Teams View all 5 articles

Tayana Soukup1*

Tayana Soukup1* Benjamin W. Lamb2

Benjamin W. Lamb2 Nisha J. Shah3

Nisha J. Shah3 Abigail Morbi4

Abigail Morbi4 Anish Bali5

Anish Bali5 Viren Asher5

Viren Asher5 Tasha Gandamihardja6

Tasha Gandamihardja6 Pasquale Giordano7

Pasquale Giordano7 Ara Darzi4

Ara Darzi4 James S. A. Green5†

James S. A. Green5† Nick Sevdalis1†

Nick Sevdalis1†Introduction: Functional perspective of team decision-making highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between team interaction/communication during a given task, the internal factors that emanate from within a group (e.g., team composition), and the external circumstances (e.g., workload and time pressures). As an underexplored area, we explored these relationships in the context of multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings (aka tumor boards).

Materials and methods: Three cancer MDTs with 44 team members were recruited from three teaching hospitals in the United Kingdom. Thirty of their weekly meetings encompassing 822 case reviews were filmed. Validated instruments were used to assess each case: Bales' Interaction Process Analysis that captures frequency of task-oriented and socio-emotional interactions/communication; and Measure of case-Discussion Complexity that captures clinical and logistic complexities. We also measured team size, disciplinary diversity, gender, time-workload pressure, and time-on-task. Partial correlation analysis controlling for team/tumor type and case complexity was used for analysis.

Results: Clinical complexity positively correlated with task-oriented communication, e.g., gives opinion (r = 0.51, p < 0.001), and logistical issues with negative socio-emotional interactions, e.g., antagonism (r = 0.14, p < 0.01). Time-workload pressure correlated with reduced task-oriented communication, e.g., gives opinion (r = −0.15, p < 0.01), and positive socio-emotional interactions, e.g., solidarity (r = −0.17, p < 0.001). Time-on-task negatively correlated with task-oriented communication, e.g., asks for orientation (r = −0.16, p < 0.001), and positive socio-emotional interactions, e.g., agrees (r = −0.21, p < 0.001). Team size and disciplinary diversity positively correlated with task-oriented communication, e.g., asks for orientation (r = 0.13, p < 0.001; r = 0.09, p < 0.05), and negative socio-emotional interactions, e.g., antagonism (r = 0.10, p < 0.01; r = 0.08, p < 0.05). Gender balance had no significant relationships (all p > 0.05), however, case reviews with more males present were associated with more tension (r = 0.09, p < 0.01) and less disagreements (r = −0.11, p < 0.01), while when more females present there were more disagreements (r = 0.10, p < 0.01) and less tension (r = −0.11, p < 0.01).

Discussion: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the relationship between MDT interaction/communication and the external/internal factors. Smaller size, gender balanced teams with core disciplines present, and streamlining workload to reduce time-workload pressure, time-on-task effects, and logistical issues appear more conducive to building and maintain optimal MDTs. Our methodology could be applied to other MDT-driven areas of healthcare.

A transdisciplinary or multidisciplinary model of care is accepted as the gold-standard in addressing the complex needs of patients with cancer (Department of Health, 2004; Cancer Research UK, 2017; Soukup et al., 2018; National Institute for Health Care Excellence, 2020). In the United Kingdom (UK), such care planning is routinely (and mandatorily) carried out by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) generally consisting of histopathologists, radiologists, surgeons, specialist cancer nurses, and oncologists, in typically weekly or fortnightly meetings (aka tumor boards). There, cases are reviewed, treatment options discussed, and recommendations agreed upon. This process is conducted in a sequential manner, usually for several hours at a time, until all patients put forward for MDT review have been discussed (Department of Health, 2004; Cancer Research UK, 2017; Soukup et al., 2018; National Institute for Health Care Excellence, 2020).

While the MDT model in cancer care is endorsed widely and has been extended to many other areas of complex care (Raine et al., 2014; Imes et al., 2020; National Institute for Health Care Excellence, 2020), such as palliative for example (Imes et al., 2020), evidence of its effectiveness remains unclear (Lamb et al., 2011, 2013; Raine et al., 2014; Soukup et al., 2016a,b, 2020a). The pattern of decision-making generally observed in MDT meetings is that of unequal participation across attending team-members and suboptimal sharing of information; this directly affects teams' ability to reach a recommendation, and subsequently implement it (Lamb et al., 2011, 2013; Raine et al., 2014; Soukup et al., 2016a,b, 2020a). MDTs are also affected by the changing economic and political landscape surrounding healthcare, i.e., increasing financial pressures (NHS England, 2014; World Health Organization, 2014), the rise in cancer incidence (Mistry et al., 2011; World Health Organization, 2014), time pressures, staff shortages (NHS Improvement, 2016), and increasing workload, especially for large teaching hospitals, leading to a rise in frequency and duration of their meetings (Aragon, 2017). In light of such pressures, safety concerns have also been raised, as sometimes dozens of patients have been reported to be discussed in one sitting by a MDT (Cancer Research UK, 2017). The evidence from studies of cancer MDMs suggests that the prolonged reviewing of sequential cases has a negative impact on the quality of treatment recommendations for patients; better quality decisions were associated with discussing patients at the beginning of the meeting (Lamb et al., 2013; Soukup et al., 2019a,b, 2020a).

Cancer MDTs are an instance of expert team decision-making. Team science has demonstrated that teams make decisions that are systematically different to those made by individuals and often better (Orlitzky and Hirokawa, 2001; Hollingshead et al., 2005; Kugler et al., 2012; Forsyth, 2014; Kettner-Polley, 2016). Interaction is an important ingredient of teams decision-making, which reduces the overconfidence bias (Sniezek and Henry, 1989), and error rate (Davies et al., 2006; Charness et al., 2007). This advantage arises as the information is processed both on an individual-person level and interactively with other team members. Within cancer care, to achieve high level of task efficiency, effective interaction and communication is critical to move the team across the different stages of decision-making - from problem identification, information sharing and critical evaluation, to formulating the decision, and implementing it (Orlitzky and Hirokawa, 2001; Hollingshead et al., 2005; Kugler et al., 2012; Forsyth, 2014; Kettner-Polley, 2016).

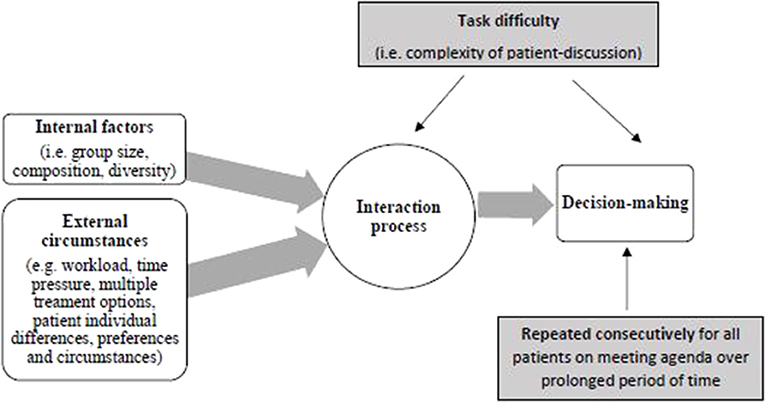

From the perspective of patient safety (Leonard et al., 2004; Vincent, 2010; Francis, 2015; Gluyas, 2015), optimal healthcare teams (Weller et al., 2014; Soukup et al., 2020b), and team decision-making (Orlitzky and Hirokawa, 2001; Hollingshead et al., 2005; Kugler et al., 2012; Forsyth, 2014; Kettner-Polley, 2016), effective interaction and communication are at the center of effective teamwork. The most influential theory of group decision-making, namely the functional perspective (Figure 1), and the associated research evidence, suggest that variability in team performance is attributable to human factors. Specifically, internal factors that come from within the group (e.g., team size, member composition, gender), and external circumstances (e.g., time pressure, workload, logistical issues). These impact on group outcomes, such as decision-making, through team interaction and communication process, and are moderated by the task difficulty or complexity. Hence, the interaction and communication process can be regulated to achieve better outcomes (Orlitzky and Hirokawa, 2001; Hollingshead et al., 2005; Forsyth, 2014; Kettner-Polley, 2016).

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the functional perspective of group decision-making as applied to cancer multidisciplinary team meetings.

A recent study (Soukup et al., 2020a) tested the functional perspective with cancer MDTs. It found that certain aspects of task-oriented communication (e.g., asking questions and providing answers to these questions), external circumstances such as clinical complexity of the cases under the discussion, and internal factors, such as bigger team size and gender balance, facilitated MDT decision-making. Barriers to team decision-making were identified as negative socio-emotional interactions (e.g., antagonism and tension), external circumstances, such as time-workload pressure, time spent making decisions, and logistical issues (e.g., administrative and process issues), as well as internal factors such as gender imbalance. The same study also unraveled time-on-task effects in relation to team interaction and communication, in particular, a reduction in the frequency of task-oriented communication and positive socio-emotional interactions (e.g., solidarity), and an increase in the negative socio-emotional responses in the second half of the meeting (when team-members are getting tired).

A question that remains unanswered in relation to the functional perspective applied to cancer MDTs is precisely how external circumstances and internal factors affect team interaction and communication. The aim of the current study was to explore, for the first time, this question, operationalized as two sets of hypotheses:

[H1: external circumstances and MDT interaction/communication]

H1a: Case complexity will relate positively to the task-orientated communication, such as asking questions and providing answers.

H1b: Logistical issues, time-workload pressure, and time spent on making decisions will relate negatively to the task-orientated communication and positive socio-emotional interactions (e.g., solidarity).

H1c: Logistical issues, time-workload pressure, and time spent on making decisions will relate positively to the negative socio-emotional responses (e.g., antagonism and tension).

[H2: internal factors and MDT communication/interaction]

H2a: Bigger team size, disciplinary diversity and gender balance will relate positively to the task-oriented communication, such as asking questions and providing answers.

H2b: Gender imbalance will relate negatively to the task-oriented communication and positive socio-emotional interactions.

H2c: Gender imbalance will relate positively to the negative socio-emotional responses.

To ensure reporting rigor in our study, we followed the STROBE checklist (Supplementary Material).

This was a prospective cross-sectional observational study.

The study took place across three university hospitals in the Greater London and Derbyshire areas in the UK between September 2015 and July 2016. Three cancer teams took part, including breast, colorectal and gynecological cancer MDTs. Their meetings were video recorded for a period of 3 months each.

The study was granted ethical and regulatory approvals by the North West London Research Ethics Committee (JRCO REF. 157441), and also locally by the R&D departments of the participating NHS Trusts. Informed consent was sought from MDT members. Consent from patients was not required because patient identifiable information was preserved during the study. This study was part of a larger MDT study (Soukup, 2017a) adopted by the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network Portfolio.

Participants were 44 MDT members: breast MDT = 15, colorectal MDT = 15, gynecological MDT = 14. The MDTs had the same composition: surgeons (n = 12), oncologists (n = 6), CNSs (n = 12), radiologists (n = 6), histopathologists (n = 5) and coordinators (who play an administrative role; n = 3). Medical students occasionally attended the meetings for educational purposes. Participants were at consultant-level during the study period with on average 9 years of experience (min = 2, max = 22). There were no overlaps between teams i.e., members were not participants of more than one team. Detailed breakdown of team composition has been reported elsewhere (Soukup et al., 2020b). The data on team interaction and the analyses reported here are novel and have not been published previously.

All case discussions on the MDT agenda were video recorded; these included suspected or confirmed cancer, and in breast and gynecological cancer teams also included benign cases. In total, the MDTs discussed 822 patients with cancer across 30 meetings during the study. Sample size in terms of the number of MDT meetings observed per team (n = 10) was determined based on prior studies (e.g., Lamb et al., 2011; Soukup et al., 2016a,b). Sample size in terms of the observed cases (N = 822) exceeded the minimum needed to detect significance, which for Pearson correlations (continuous variables) would be 396, and for point-biserial correlations (categorical variables) 79 observational units (calculated using G*Power 3 for a priori power analysis with d = 0.50; α = 0.05; and 1-β = 0.95).

Availability sampling was used to identify the teams with a criterion for the study being a cancer MDT from the UK National Health Service (NHS) that represents the commonest type of cancer.

Quantitative observational assessments were conducted for each of the 822 case discussions using two validated observational instruments. All assessments were conducted from video recordings. What follows is a description of the instruments and variables used for each case discussion, while the copies of the tools can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Between team members during case discussions was assessed using Bales Interaction Process Analysis (Bales, 1950, 1970; Soukup, 2017a). This is an observational coding system initially developed with small health care teams engaged in weekly diagnostic meetings at Harvard Psychological Clinical, and further refined in simulated team meetings. It is based on a principle that a small group represents 2–20 individuals engaged in a face-to-face interaction, within a meeting or series of such meetings, where basic formal similarities irrespective of the context and inherent values exist, i.e., “certain types of action tend to have certain types of effects on subsequent action” (Bales, 1950). As such, it is particularly suitable for cancer MDT meetings: while it was developed and validated within a very similar setting, it can be used in groups that are diverse in composition, character and purpose (e.g., diagnostic and policy forming committees, boards and panels, group therapy and training, work groups, doctor-patient dyads). For every patient discussed in the meeting, four aspects of MDT interaction (verbal and nonverbal) were captured exclusively quantitatively using frequency counts by marking the originator and target of each interaction while following the specific rules and the framework (more information on the rules and scoring it can be found here Bales (1950, 1970) and Soukup (2017a); this is as follows:

1. Shows solidarity, cooperation, gives help, raises others status, friendly (e.g., “May I proceed?” “I can see how you feel.” “You covered a lot of ground.”);

2. Tension release, jokes, laughs, shows satisfaction (e.g., laughing, cheerfulness);

3. Agrees, shows passive acceptance, understands, complies, concurs (e.g., “Then I guess we all agree on that.” “Let's do that.” “Correct.” “Yes, that's it.”).

4. Disagrees, shows passive rejection, un-acknowledging (e.g., doing something other than the task such as whispering), hesitant, critical, withholds help (e.g., “I don't think so.” “I don't think that's right.”);

5. Shows tension, fear of provoking opposition, frustrated, concerned, asks for help (e.g., quiet speaking, stammering, appearing startled);

6. Shows antagonism, deflates other's status, asserts self, autocratic (e.g., “Hurry up.” “Stop that.” “Write it on the MDT”).

1. Asks for orientation, information, repetition, confirmation, clarification (e.g., “What was that?” “I don't quite get what you mean?” “Where are we?” “What is her performance status?”);

2. Asks for opinion, evaluation, interpretation, decision-making, reasoning (e.g., “What do you think we ought to do here?” “What else could it be?” “What do you think?” “Has she got some other malignancy going on?”);

3. Asks for suggestion, direction, instruction, solution, way to achieve goal (e.g., “I don't know what else we could do here?” “The question here is…” “Can we send her to you Anna?” “What do you suggest?”).

4. Gives suggestion, direction, instruction, solution, way to achieve goal (e.g., “And the next one…” “She can go to virtual clinic.” “She will need staging etc.” “We need to bring her back.”);

5. Gives opinion, evaluation, interpretation, decision-making, reasoning (e.g., “I think we need to discuss…” “I am a little be concerned…” “In the literature they do describe main papilloma but this is not the case in this case.” “Because…”);

6. Gives orientation, information, repeats, confirms, clarifies (e.g., “This seems to finish our agenda,” “It would take 2 days to reach him.” “We are just discussing” “In summary, this is someone…”).

Complexity of each case discussion in the meeting was assessed using a psychometrically valid and reliable tool, namely, Measure of case-Discussion Complexity (MeDiC; Soukup, 2017a; Soukup et al., 2020c). MeDiC has been developed following a multiphase research process over 18 months with input from cancer specialists. MeDiC captures clinical complexity (incl. pathology, patient factors and treatment factors), and logistical complexity (administrative and process of care issues) for each patient discussed in the MDT meeting; the former is scored using a checklist principle (with added weight for certain items), while the latter is scored as frequency (tally for every occurrence).

Internal factors emanating from within the group were assessed as follows:

1. Team size as an overall number of members present at any one case discussion;

2. Disciplinary composition as a counter that increases for each additional discipline present during any one case discussion;

3. Disciplinary distribution as a categorical variable denoting whether equal number of people within each discipline was present for any one case discussion (0 = unequal disciplinary distribution, 1 = equal disciplinary distribution); and

4. Gender composition as 3 separate categorical variables denoting (1) more males, (2) more females, and (3) gender balance for any one discussion.

External circumstances coming from outside the team were assessed as follows:

5. Time-workload pressure as a time-workload ratio, calculated as the time left to discuss the patients from the MDT list divided by the number of patients left to be discussed; higher scores indicate decreased time-workload pressure, while the lower values denote increased time-workload pressure.

6. Time-on-task/Decision counter was captured as a serial/ordinal counter that increases for each decision made in the meeting denoting an act of making repeated decisions (i.e., a decision count).

7. Case complexity was captured via the MeDiC tool.

8. Logistical complexity was captured via the MeDiC tool.

Training in the use of the two observational tools was undertaken by all evaluators prior to the formal scoring during the study. Training is essential to be able to use correctly instruments assessing human factors in clinical environments (Hull et al., 2013). Training involved: (1) explanation of the domains, scales and their anchors, (2) background reading of peer-reviewed literature on the tool, (3) practicing scoring on MDT videos, and (4) calibration of scoring against an expert evaluator (TS). Proficiency in scoring was set as an achievement of inter-assessor reliability of 0.70 or higher between the trainee and expert assessor (Hull et al., 2013) across both observational instruments; this was met. Second assessor rated 15–20% of case discussions for each tool respectively with their scores were calibrated against the main assessor (TS). For Bales' IPA, scores were calibrated with a social scientist (NJS), and for MeDiC with an academic physician (AM). Each evaluator was blind to the other evaluators' observations. The case selection was driven predominantly by the pragmatic considerations and the availability of the second assessor who was not a member of the participating MDT and was blinded to the patient list for the meetings and the first assessor's scores.

Observer bias was addressed and reliability of evaluations on the two instruments was ensured by having a subset of cases scored by the evaluators in pairs (TS and NJS for Bales' IPA; TS and AB for MeDiC) who were all trained in the use of the instruments. During the data collection, each evaluator was blind to the other evaluators' observations. To reduce the Hawthorne effect, i.e., teams changing their usual behavior due to being observed, we adopted a long-term approach by filming each team for a prolonged period of time i.e., 3 months/12 consecutive weekly meetings respectively, and we excluded the first two meetings in each team from the analysis as they were designed to allow the members to get used to the camera and induce habituation. The meetings for each team/hospital were weekly for the duration of 3 months. Since these were three distinct teams across three different hospitals, we filmed their weekly meetings in parallel during this period. We also ensured that filming was done discretely by addressing any factors that could serve as a constant reminder to the team that they are being filmed thus allowing the members to “forget” about the camera and continue their working practices as usual. We did this by using a small recording camera, namely, GoPro, with sound settings and recording light switched off, and using a remote control to start and stop recording. The camera was positioned in the area where it blended in with the background equipment and cables and was out of immediate view of the team.

Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis was used to assess reliability of evaluations between assessors for each tool. A single measure ICC with the two-way mixed effects model and an absolute agreement definition was used. ICCs can range between 0 and 1 with higher values indicating better agreement.

Partial correlation analysis controlling for team/tumor type (i.e., breast, colorectal, and gynecological MDTs) and case complexity (using MeDiC) was used to explore the relationship between internal and external factors and team interactions. For the categorical variables, such as disciplinary distribution and gender, point-biserial correlations were run with bootstrapping and tumor type as a stratified variable. Scoring and analysis was conducted for each individual cancer case (N = 822) which means that each case received a score on all the variables/dimensions.

All analyses were carried out using SPSS® version 20.0 on a dataset available on Zenodo (Soukup, 2017b).

Table 1 presents data on the composition of participating teams. Table 2 provides an overview of the MDT meeting characteristics. The gynecological MDT had the highest caseload and longest meetings, while the colorectal team had the least number of cases for MDT discussion and shortest meeting duration. The colorectal team spent the most time discussing each patient, followed closely by the gynecological and breast teams. Time-workload pressure was the highest for the breast team, followed closely by the gynecological and colorectal teams. In terms of team composition, breast and colorectal teams on average had the same number of disciplines present, with the gynecological team having a slightly lower average disciplinary attendance. In terms of team size, breast and colorectal teams had similar number of members attending the meetings with the gynecological team being the smallest. There were more female members in attendance in breast and colorectal teams, while in the gynecological team there were more male attendees. Gender balance was achieved on a quarter of cases discussed during the study period in the breast and colorectal MDT meetings, while in the gynecological meetings a substantially lower percentage is evident.

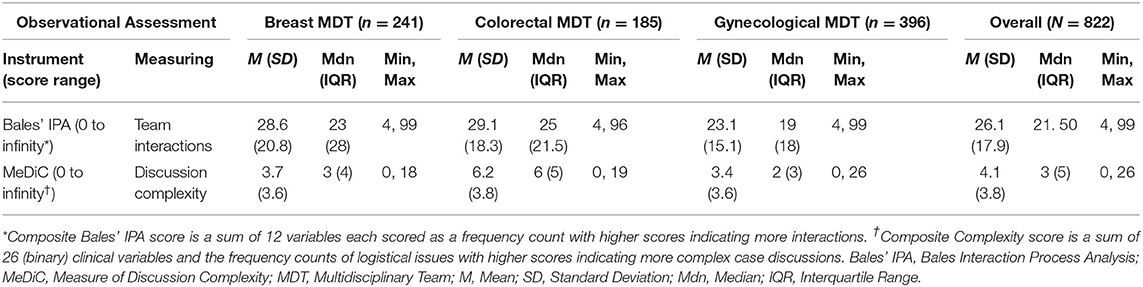

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics for the composite score for Bales' IPA (interaction process) and MeDiC (case complexity). The colorectal team had the highest mean scores on both measures, indicating the most intense interaction process, and most complex case discussions. Breast team closely followed with the scores on the interaction process. Both breast and gynecological teams had similar mean scores on case complexity.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for the composite scores of the Measure of case-Discussion Complexity (MeDiC) and Bales Interaction Process Analysis (Bales' IPA).

Inter-assessor agreement was examined using ICCs on a subset of cases: 15% (N = 117) for Bales' IPA, and 17% (N = 136) for MeDiC. Disagreements were resolved by the two assessors discussing the observations. For the composite values for both tools, reliability was as follows: ICC = 0.993 (95% CI = 0.989–0.996) for Bales' IPA, and ICC = 0.995 (95% CI = 0.994–0.997) for MeDiC.

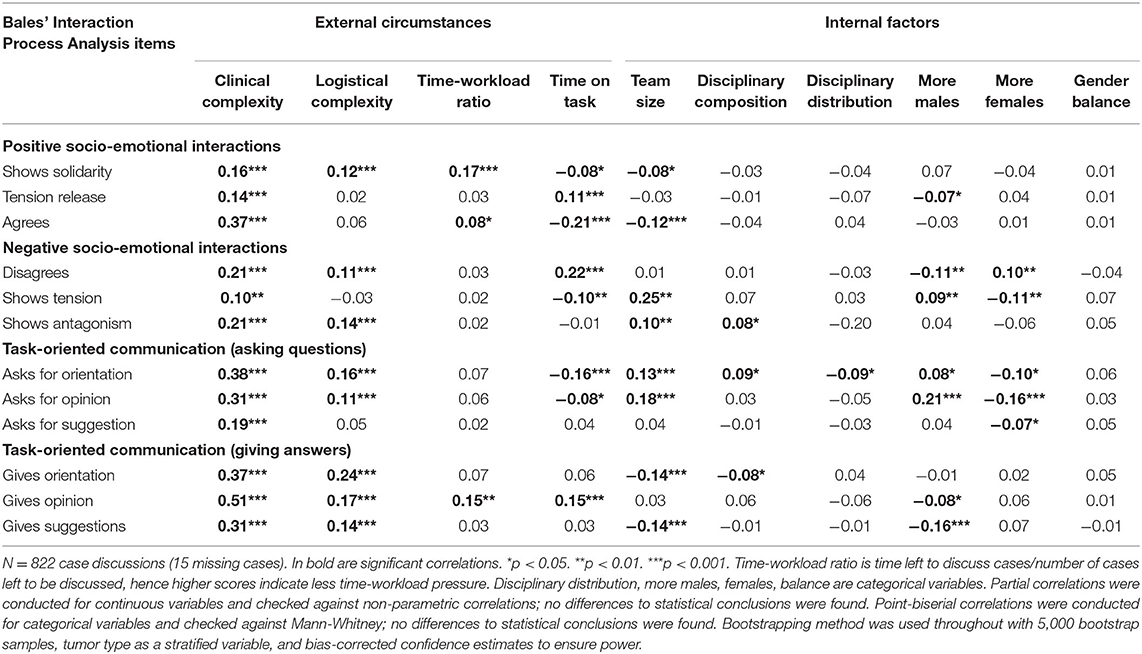

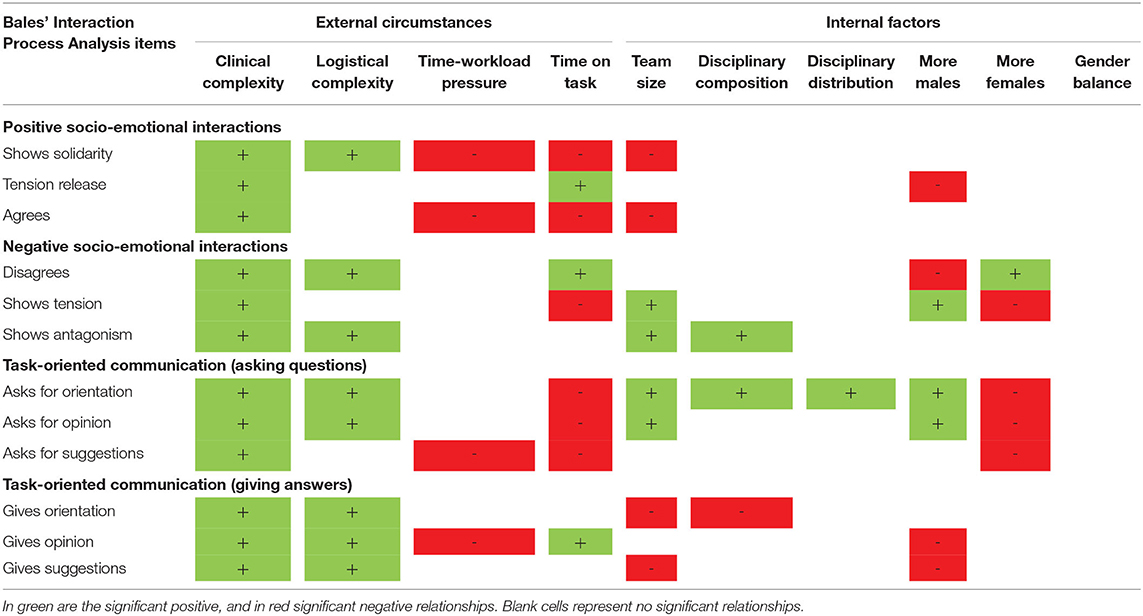

To assess our hypotheses and explore the relationship between the internal and external factors, and the team interaction/communication process, we conducted partial correlation analysis controlling for tumor type and case complexity. The correlation coefficients are presented in Table 4; the pattern of relationships between variables is shown visually in Table 5.

Table 4. Partial correlations between Bales' Interaction Process Analysis (Bales' IPA) and external circumstances and internal factors.

Table 5. Overview of the relationship between Bales' Interaction Process Analysis and external circumstances and internal factors.

Case complexity was positively correlated with the task-oriented communication, which is in line with the H1a. In addition, however, a positive relationship was also observed in relation to the negative and positive socio-emotional interactions between the team members.

Logistical issues were positively related to the negative socio-emotional interactions, such as disagrees and antagonism, which is in line with the H1b. Contrary to H1b and H1c however, logistical issues positively correlated with the task-oriented communication, such as asking questions and providing answers, as well as with the positive socio-emotional responses, especially solidarity.

Time-workload pressure was negatively related to the task-oriented communication, such as gives opinion, as well as the positive socio-emotional interactions, such as solidarity and agreeableness; as per the H1b. However, contrary to H1c, no association was evident with the negative socio-emotional aspects.

Time-on-task/decision counter was negatively correlated with the task-oriented communication, such as asks for orientation and opinion, as well as the positive socio-emotional interactions, such as solidarity and agrees. Positive association was evident with the negative socio-emotional interactions, such as disagrees and tension release, providing further support to the H1b and H1c.

Increased team size was positively related to task-oriented communication, such as asking questions, which partly supports the H2a; however, a negative association was evident with providing answers, which partly contradicts the H2a. In addition, a positive relationship was evident with the negative socio-emotional interactions, in particular, tension and antagonism, and a negative one with the positive socio-emotional interactions, such as solidarity and agrees.

Disciplinary diversity positively correlated with the task-oriented communication, such as asking questions, which partly supports H2a, but negatively with providing answers, which partly contradicts H2a. In addition, a positive relationship was evident with the negative socio-emotional interactions, in particular, antagonism.

Contrary to H2b, gender balance had no relationship with task-oriented communication. However, in line with H2b and H2c, gender imbalance was negatively associated with the task-oriented communication and positive socio-emotional interactions, and positively with the negative socio-emotional responses. In particular, case discussions with more male members present were associated with less tension release and disagreements, but with more showing tension. They were also associated with more asking questions, but with less providing answers. In contrast, case discussions with more female members were associated with more disagreements, but with less showing tension, and asking questions.

The aim of this study was to explore, for the first time to our knowledge, the relationship between cancer MDT interaction/communication and the external circumstances and internal factors of the team in line with the recent study (Soukup et al., 2020a)This is important to explore since, as per the functional perspective, external circumstances and internal factors affect team decision-making via the interaction processes, hence understanding the relationships between them is important for better understanding of team processes (Orlitzky and Hirokawa, 2001; Hollingshead et al., 2005; Forsyth, 2014; Kettner-Polley, 2016).

Our data largely supported the H1a (i.e., case complexity will relate positively to the task-oriented communication, such as asking questions and providing answers), H1b (i.e., logistical issues, time-workload pressure, and time spent on making decisions will relate negatively to the task-orientated communication and positive socio-emotional interactions), and H1c (i.e., logistical issues, time-workload pressure, and time spent on making decisions will relate positively to the negative socio-emotional responses. More specifically, we found that as the clinical complexity increased, the frequency of task-oriented communication increased, which is expected given that it facilitates team decision-making (a task-focused activity; Lamb et al., 2013). However, clinical complexity also seems to intensify socio-emotional interactions among team members during case reviews with an increase evident in both, acts of solidarity, as well as tension and antagonism. Similarly, logistical issues experienced in the meeting (previously identified as a barrier to MDT decision-making; Lamb et al., 2013) intensified socio-emotional interactions between team members in the same manner. However, contrary to H1b, they also intensified MDT communication with more questioning and answering, arguably in the attempt to rectify errors and compensate for process issues such as technical failures or lack of attendance of key members (for a full list of logistical issues see Soukup et al., 2020a).

Time-workload pressure and time spent making decisions were both associated with reduced frequency of task-oriented communication (i.e., asking questions and providing answers), and acts of solidarity, which is expected given that they are both barriers to team decision-making (Soukup et al., 2020a). However, despite no association with negative socio-emotional interactions (contrary to H1c), we found that the more cases the team reviews in a meeting, the higher the frequency of tension and disagreeing; a finding that is in line with the previous study showing an increase in negative and decrease in positive socio-emotional interactions in the meeting (Soukup et al., 2020a), other work in the field focused on time-workload pressure (Kane and Luz, 2013), and the time-on-task effects previously recorded in MDT meetings including also other clinical settings (Soukup et al., 2019b).

Our data also largely supported the H2a (i.e., Bigger team size, disciplinary diversity and gender balance will relate positively to the task-oriented communication, such as asking questions and providing answers), H2b (i.e., gender imbalance will relate negatively to the task-oriented communication and positive socio-emotional interactions), and H2c (i.e., gender imbalance will relate positively to the negative socio-emotional responses). More specifically, increased team size and disciplinary diversity were related to increased frequency of task-oriented communication, in particular, asking questions, which is as expected given that they both facilitate team decision-making process (Soukup et al., 2020a). However, in part contrary to H2a, they were also associated with the reduced frequency of providing answers to these questions with an unexpected finding being their association with tension and antagonism (and for increased team size also with reduced acts of solidarity and agreeableness). This finding highlights the importance of finding the optimal balance in MDT size and diversity to preserve its beneficial effects on decision-making without compromising the quality whereby the team is excessively large.

Contrary to H2a, gender balance was not associated with the task-oriented communication (or socio-emotional interaction), despite it being a facilitator to team decision-making (Soukup et al., 2020a). However, gender imbalance (a barrier to team decision-making; Lamb et al., 2013) showed associations largely in line with our H2b. It appeared that case reviews with more male members present were associated with more task-oriented communication, such as asking questions, but with less providing of answers to these questions. They were also associated with higher frequency of tension, but less disagreements and tension release (joking, laughing, self-revealing). A reverse pattern was seen for case reviews with more female members present: more disagreements, but less tension and questioning.

It is evident from the current and previous study (Soukup et al., 2020a) that effective interaction and communication are critical in facilitating decision-making for patients discussed at MDT meetings. Given these findings, efforts need to be channeled into determining optimal size of an MDT to preserve its beneficial effects on decision-making for patients, while mitigating its negative impact on team interaction and communication (Soukup et al., 2020a). Further work is also needed to explore effectiveness and implementation of a trained, clinically noncontributing meeting chair or alternatively in up-skilling meeting chair in managing “multidisciplinarity” in these teams to preserve its beneficial effect on decision-making, while mitigating the negative impact on team interaction and communication, ensuring optimal quality of care for patients. This is in line with the functional perspective whereby interaction and communication in teams can be regulated with appropriate strategies to achieve better outcomes (Hollingshead et al., 2005; Forsyth, 2014). In addition, international testing and calibration of the MeDiC tool (NHS England NHS Improvement, 2020; Soukup et al., 2020c,d) is needed to explore implementation of a case selection for MDT meetings in a reliable and valid manner. This could help facilitate effective MDT interaction and decision-making for patients. Lastly, scientific efforts are needed to test the functional perspective in its entirety using a mediator-moderator modeling of MDT decision-making, interactions, internal factors, and external circumstances to build a comprehensive picture of their functioning, and how this differs across teams and settings.

The study we report here was inspired by social science frameworks (e.g., functional perspective) and behavioral science methodologies (e.g., behavioral observation). We believe that application of such approaches to a core clinical care, such as cancer care delivery, carries significant implication for what is arguably the most important ingredient in high-quality care: the expert healthcare providers who care for these patients. We propose that our study finding offer practical directions for improving the way cancer teams meet and work together. Firstly, with minimal additional resource, a cancer team could reduce the size of meeting attendees and implement staff selection to ensure gender balance, while preserving the professional diversity necessary for clinical decision-making. A cancer team with particularly long meetings and high workload could introduce a short break with refreshments (Soukup et al., 2019b). Secondly, with some additional resource, a cancer team could appoint a trained, clinically non-contributing meeting chair to help effectively navigate interaction and communication process between disciplines, ensuring a uniformly better decision-making process for all patients reviewed by the MDT (Soukup et al., 2018). Alternatively, a specific training program could be designed to up-skill meeting chairs in negotiation and communication. There are some aspects of the context in which cancer MDTs work that require policy-level changes; for example, reducing time-workload pressure through streamlining workload, and addressing logistical issues ahead of the meeting. This could be achieved as part of preparation for the meeting by using a checklist (e.g., MDT-QuIC) to ensure that all essential information is adequately available for the meeting (Lamb et al., 2012; Soukup et al., 2020d), and by implementing a case selection rule for MDTs (e.g., selecting the most complex cases for review based on their MDT-MeDiC scores; NHS England NHS Improvement, 2020; Soukup et al., 2020c,d).

Our findings need to be interpreted within certain limitations. First is the Hawthorne effect. In line with the ethical and regulatory approvals of participating NHS organizations in the UK, we sought informed consent from team members which meant that they knew that they were going to be filmed (i.e., there was no deception). To minimize this effect, we: (1) adopted a long-term approach by filming each team for a prolonged period of time, (2) excluded the first two meetings in each team from the analysis as they were designed to allow the members to get used to the camera and induce habituation, (3) ensured that filming was done discretely by using a small recording camera (with light and sound switched off, and using a remote control) out of immediate view of the team, and (4) used validated observational assessment tools scored by trained evaluators in pairs blind to one another's observations. Secondly, while the current study is focused on MDT meetings, we have not linked these processes to clinical, patient-related outcomes. As a result, the safety and clinical implications of this analysis remain exploratory. Moreover, while the sample size is adequately large (N = 822) for an observational study, it represents the most common cancers within the English NHS. Replication of the study on other cancer, teams and healthcare systems may be needed to determine generalizability of the findings. Lastly, we scored Bales' IPA by strictly following the instructions provided in the literature (Bales, 1950, 1970), which are focused exclusively on coding the behaviors in a quantitative manner. While such approach had enabled us to score a large number of cases (N = 822), it meant that we did not capture qualitative examples underpinning each Bales' IPA domain. We recognize that capturing such examples would have been uniquely useful in improving readability of the findings, helping researchers relate more closely to the setting being analyzed, and facilitating subsequent training in the use of the tool. Hence future research should aim to capture such examples.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to attempt to assess the relationship between MDT interaction/communication and the external circumstances internal factors, as proposed by the functional perspective. We found that the smaller size, gender balanced teams with only core disciplines present and streamlining workload to reduce time-workload pressure, time on task effects and logistical issues may be a more conducive set-up for building and maintain optimal MDTs. Our methodological approach could be profitably applied to other MDT-driven areas of healthcare to inform teams and provide guidance for them to optimize MDT working across specialties.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://zenodo.org/record/582272#.XntHvoj7Q2w.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by North West London Research Ethics Committee (JRCO REF. 157441). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

TS had made substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study. All authors have made substantial contribution to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content, have given final approval of the version to be published, and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by the UK's National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) via the Imperial Patient Safety Translational Research Center. NS research is funded by the NIHR via the Applied Research Collaboration: South London at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. NS is also a member of King's Improvement Science, which offers co-funding to the NIHR ARC South London and comprises a specialist team of improvement scientists and senior researchers based at King's College London. Its work is funded by King's Health Partners (Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, King's College London and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust), Guy's and St Thomas' Charity and the Maudsley Charity. The funding agreement ensured the authors' independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

BL and TS received funding for training MDTs in assessment and quality improvement methods in the United Kingdom. TS served as a consultant to F. Hoffmann-La Roche Diagnostics providing advisory research services in relation to innovations for multidisciplinary teams and their meetings in the United States. NS was the Director of London Safety and Training Solutions Ltd, which provides patient safety and quality improvement training and advisory services on a consultancy basis to hospitals and training programs in the UK and internationally. JG was the Director of Green Cross Medical Ltd that developed MDT FIT for use by National Health Service Cancer Teams in the UK.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors thank the cancer MDTs and their members for their time and commitment to the project. Infrastructure support for this research was provided by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2020.583294/full#supplementary-material

Aragon, N. (2017). Hospital trusts productivity in the English NHS. PLoS ONE 12:e0182253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182253

Cancer Research UK (2017). Improving the Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Team Meetings in Cancer Services. London: Cancer Research UK.

Charness, G., Karni, E., and Levin, D. (2007). Individual and group decision making under risk: an experimental study of Bayesian updating and violations of first-order stochastic dominance. J. Risk Uncertain. 35, 129–148. doi: 10.1007/s11166-007-9020-y

Davies, A. R., Deans, D. A., Penman, I., Plevris, J. N., Fletcher, J., Wall, L., et al. (2006). The multidisciplinary team meeting improves staging accuracy and treatment selection for gastro-esophageal cancer. Dis. Esophagus. 19, 496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00629.x

Gluyas, H. (2015). Effective communication and teamwork promotes patient safety. Nurs. Stan. 29, 50–57. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.49.50.e10042

Hollingshead, A. B., Wittenbaum, G. M., Paulus, P. B., Hirokawa, R. Y., Ancona, D. G., Peterson, R. S., et al. (2005). “A look at groups from the functional perspective,”. in Theories of Small Groups: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, eds A. B. Hollingshead, and M. S. Pool (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 21–62. doi: 10.4135/9781483328935.n2

Hull, L., Arora, S., Symons, N. R., Jalil, R., Darzi, A., and Vincent, C. (2013). Delphi expert consensus panel. Training faculty in nontechnical skill assessment: national guidelines on program requirements. Ann. Surg. 258, 370–375. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318279560b

Imes, R. S., Omilion-Hodges, L. M., and Hester, J. D. B. (2020). Communication and Care Coordination for the Palliative Care Team: A Handbook for Building and Maintaining Optimal Teams. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company LLC. doi: 10.1891/9780826158062

Kane, B., and Luz, S. (2013). “Do no harm”: Fortifying MDT collaboration in changing technological times. Int. J. Med. Inform. 82, 613–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.03.003

Kettner-Polley, R. (2016). A brief history of interdisciplinary cooperation in the study of small groups. Small Group Res. 47, 115–133. doi: 10.1177/1046496415626514

Kugler, T., Kausel, E. E., and Kocher, M. G. (2012). Are groups more rational than individuals? A review of interactive decision making in groups. Cog. Sci. 3, 471–482. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1184

Lamb, B. W., Brown, K., Nagpal, K., Vincent, C., Green, J. S. A., and Sevdalis, N. (2011). Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 18, 2116–2125. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1675-6

Lamb, B. W., Green, J. S., Benn, J., Brown, K. F., Vincent, C., and Sevdalis, N. (2013). Improving decision making in multidisciplinary tumor boards: prospective longitudinal evaluation of a multicomponent intervention for 1,421 patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 217, 412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.04.035

Lamb, B. W., Sevdalis, N., Vincent, C., and Green, J. S. A. (2012). Development and evaluation of a checklist to support decision making in cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: MDT-QuIC. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19, 1759–1765. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2187-0

Leonard, M., Graham, S., and Bonacum, D. (2004). The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual. Saf. Health C. 13, 85–i90. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010033

Mistry, M., Parkin, D. M., Ahmad, A. S., and Sasieni, P. (2011). Cancer incidence in the UK: projections to the year 2030. Br. J. Cancer 105, 1795–1803. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.430

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020). Improving Outcomes in Urological Cancers. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

NHS England (2014). Everyone Counts: Planning for Patients 2014/2015 to 2018/2019. London: NHS England.

NHS England and NHS Improvement (2020). Streamlining Multi-Disciplinary Team Meetings: Guidance for Cancer Alliances. London: NHS England and NHS Improvement.

NHS Improvement (2016). Evidence From NHS Improvement on Clinical Staff Shortages: A Workforce Analysis. London: NHS Improvement.

Orlitzky, M., and Hirokawa, R. Y. (2001). To err is human, to correct for it divine: A meta-analysis of research testing the functional theory of group decision-making effectiveness. Small Group Res. 32, 313–341. doi: 10.1177/104649640103200303

Raine, R., Xanthopoulou, P., and Wallace, I. (2014). Determinants of treatment plan implementation in multidisciplinary team meetings for patients with chronic diseases: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 23, 867–876. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-002818

Sniezek, J. A., and Henry, R. A. (1989). Accuracy and confidence in group judgment. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 43, 1–28. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(89)90055-1

Soukup, T. (2017a). Socio-cognitive factors that affect decision-making in cancer multidisciplinary team meetings (PhD Thesis; Clinical Medicine Research). London: Imperial College London.

Soukup, T. (2017b). Decision-Making, Interactions and Complexity Across Three Cancer Teams [Data set]. Zenodo.

Soukup, T., Gandamihardja, T., McInerney, S., Green, J. S. A., and Sevdalis, N. (2019a). Do multidisciplinary cancer care teams suffer decision-making fatigue: an observational, longitudinal team improvement study. BMJ Open. 9:e027303. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027303

Soukup, T., Lamb, B. W., Arora, S., Darzi, A., Sevdalis, N., and Green, J. S. A. (2018). Successful strategies in implementing multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: an overview and synthesis of the available literature. J. Mult. Health. 11, 49–61. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S117945

Soukup, T., Lamb, B. W., Morbi, A., Shah, J. N., Bali, A., Asher, V., et al. (2020a). A multicentre cross-sectional observational study of cancer multidisciplinary teams: analysis of team decision-making. Cancer Med. 00, 1–17. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3366

Soukup, T., Lamb, B. W., Sarkar, S., Arora, S., Shah, S., Darzi, A., et al. (2016a). Predictors of treatment decision in multidisciplinary oncology meetings: a quantitative observational study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 23, 4410–4417. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5347-4

Soukup, T., Lamb, B. W., Sevdalis, N., and Green, J. S. A. (2020d). Streamlining cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: challenges and solutions. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 81, 1–6. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2020.0024

Soukup, T., Lamb, B. W., Weigl, M., Green, J. S. A., and Sevdalis, N. (2019b). An integrated literature review of time-on-task effects with a pragmatic framework for understanding and improving decision-making in multidisciplinary oncology team meetings. Front. Psychol. 10:1245. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01245

Soukup, T., Morbi, M. A., Lamb, B. W., Gandamihardja, T., Hogben, K., Noyes, K., et al. (2020c). A measure of case complexity for streamlining workflow in cancer multidisciplinary tumor boards: mixed methods development and early validation of the MeDiC tool. Ca Med. 00, 1–12. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/qzwf8

Soukup, T., Murtagh, G., Bali, A., Gandamihardja, T., Darzi, A., Green, J. S. A., et al. (2020b). Gaps and overlaps in healthcare team communication: feasibility analysis of speech patterns in cancer multidisciplinary meetings. Small Group Res. 1–31. doi: 10.1177/1046496420948498

Soukup, T., Petrides, K. V., Lamb, B. W., Sarkar, S., Arora, S., Shah, S., et al. (2016b). The anatomy of clinical decision-making in multidisciplinary cancer meetings: a cross-sectional observational study of teams in a natural context. Medicine 95:e3885. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003885

Weller, J., Boyd, M., and Cumin, D. (2014). Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamworking in healthcare. Br. Med. J. 90, 149–154. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168

Keywords: transdisciplinary teams, multidisciplinary tumor boards, team communication, team interaction, workload

Citation: Soukup T, Lamb BW, Shah NJ, Morbi A, Bali A, Asher V, Gandamihardja T, Giordano P, Darzi A, Green JSA and Sevdalis N (2020) Relationships Between Communication, Time Pressure, Workload, Task Complexity, Logistical Issues and Group Composition in Transdisciplinary Teams: A Prospective Observational Study Across 822 Cancer Cases. Front. Commun. 5:583294. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.583294

Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 23 October 2020;

Published: 19 November 2020.

Edited by:

Leah M. Omilion-Hodges, Western Michigan University, United StatesReviewed by:

Bridget T. Kane, Karlstad University, SwedenCopyright © 2020 Soukup, Lamb, Shah, Morbi, Bali, Asher, Gandamihardja, Giordano, Darzi, Green and Sevdalis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tayana Soukup, VGF5YW5hLnNvdWt1cEBrY2wuYWMudWs=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.