- 1Department of Media and Communications, University of Klagenfurt, Klagenfurt, Austria

- 2Communication Studies Department, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 3Institute for Social Medicine and Epidemiology, University of Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany

- 4School of Communication and Arts, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

In this paper, we analyze public discourses in 2018 about water-scarce Cape Town, SA. We investigated the discursive implications of apocalyptic rhetoric such as “Day Zero” by analyzing local and international news media talk (n = 111 newspaper articles) surrounding the Cape Town water crisis during pre-, height of, and post-crisis moments, complemented by 12 narrative problem-centered interviews in the height of the water crisis. The analysis led to a focus on the relationship between environmental and communicative developments with a high local impact, and mainly on examples of local engagement, social movements, or resistance as response to changing environmental scenarios and the evaluation of the role of (news) media in raising community concern and commitment. The findings show that the communication around the (twice-postponed) “Day Zero” in Cape Town is a very fruitful example of the digital disrupted, post-truth communication that happens with environmental issues today.

Introduction

Today's societies are dependent on access to clean water. Despite that, one-fifth of the world's population, which corresponds to around two billion people, live in areas facing water scarcity. In total, two-thirds of the entire global population experiences water scarcity at least one month a year (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2016), while another 1.6 billion human beings encounter economic water shortages (UN, 2018). An estimated two-thirds of the world's population is expected to face water shortages in the next five years, thus making water supply and water scarcity crucial issues and increasingly urgent problems (UNPD, 2006; UNEP, 2016; European Commission, 2018). As a consequence, communication on water as a risk is considered to be the key element in optimizing water resource management (IWA International Water Association, 2019), and plays a major role in the UN's Sustainability Development Goals framework for meeting Climate Change related challenges on an international, national, regional and local level (UN, 2020).

Various meaning making processes focus on water as a resource that is profitable, polluted, threatened, or scarce—again on an interpersonal and community but as well national and international level. Water resources and supply, water politics, and water management are sensitive issues and covering these issues on those levels is a multifaceted challenge—for all kind of organizations and institutions but the media in particular. This is chiefly due to understandings of water as a “transversal resource,” meaning that both water management and water communication are subject to many influences and interests, and the mentioned meaning making has often a certain political or corporate spin (Hervé-Bazin, 2014). Literature shows that water resource management is linked to issues of power and politics, especially in water stressed areas (Trumbo and O'Keefe, 2001; Jöborn et al., 2005; Dolnicar and Hurlimann, 2010; Spinks et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2018). Inadequate or inappropriate water governance—including management practices, institutional arrangements, and intransparent socio-political conditions—as well as economic interests influence mainly the public debate on water as a resource and the risk of scarcity, the degree of problematization of water issues, and the use and abuse of environmental issues like water in political discourses.

Based on this background and with a focus on narratives, frames and metaphors used to express hegemonic frames and the abovementioned spin in public meaning making processes around risks, we analyzed the discourse about water scarcity in Cape Town in 2017/2018 with a specific interest in the communicative dynamic of the announced “Day Zero.” Therefore, the focus of the paper is centered on water resource management policy; examples of local engagement, social movements, or resistance as responses to changing environmental scenarios; and the evaluation of the role of (news) media.

Introducing “Day Zero”: The Case of Cape Town

On January 18, 2018, the mayor of Cape Town Patricia de Lille announced in a press conference that the city of Cape Town had reached “a point of no return” and set an arrival of “Day Zero” —the day when Capetonians taps would be turned off—on April 21, 2018.

However, Cape Town did not run out of water on April 21, 2018. Instead, preventive measures were adopted and “Day Zero” was postponed to June 4, 2018. When June 4 was reached, Capetonians' taps still were not switched off, nor were taps turned off on any of the other predicted “Day Zero” dates (Ma, 2018). Moreover, although “Day Zero” was later pushed to sometime in 2019 (Chutel, 2019), the year concluded with taps still flowing.

Previous research has identified the impact media coverage of drought can have on public understanding of environmental issues (O'Donnell and Rice, 2008). Since the public often uses mass media to gain information on environmental issues and assess risks before enacting policies (Dearing, 1995), it is essential to understand how media communication on environmental crises like “Day Zero” is framed and what kind of public response it seeks to evoke. Indeed, the strategic communication of a “Day Zero” frame with a strong metaphorical character had an impact on how the situation and risk was interpreted locally, nationally and globally. To this purpose, Part 1 of our study traces back and analyses the media discourse on “Day Zero,” while Part 2 investigates the meaning making process the water crisis aroused in the local community and analyses the role of (news) media in the framing process.

Materials and Methods

Understanding Water as a Transformative Environmental Issue

Although “water communication” is not recognized as a specific field of research, communication about water is widely regarded as a sub-discourse of environmental communication and natural resource management (Bennett, 2003; Mäki, 2010; Hervé-Bazin, 2014; Liang et al., 2018; Mitra, 2018). Environmental communication is useful in that it “helps us construct or compose representations of nature and environmental problems as subjects for our understanding” (Cox, 2013, p. 19). The constitutive component of communication implies that when communicating about the environment, specific values and references as well as images and contexts are associated with particular issues. If public discourses are perceived as scripts assembled from the mentioned structural elements (Dryzek, 1997), then frames (Entman, 1993) can be understood as embracing these elements, making them “invaluable tools for presenting relatively complex issues” (Scheufele and Tewksbury, 2007, p. 12). Thus, frames serve as specific interpretative tools that help us understand discourses on complex topics, such as water as a resource and the risk of water scarcity or (mis-)management.

Framing research from an environmental communication perspective mostly focuses on specific topics, such as climate change (Nisbet, 2009, 2010; O'Neill et al., 2015; Brüggemann and Engesser, 2017), and usually involves analyzing news or social media content (Boykoff, 2011; Schäfer and Schlichting, 2014; Newman and Nisbet, 2015). Additionally, some studies have examined sustainability as a master frame in climate change related discourses (Atanasova, 2019; Weder, 2021) and its strategic use by corporations (Schlichting, 2013; Schäfer, 2015; Diprose et al., 2018), political institutions (O'Neill et al., 2015), or organizations in general (Miller, 2012). When viewing water scarcity as a climate change-related problem, issue-specific framing approaches (de Vreese, 2005) appear applicable. However, our focus on communicative problematization processes (in the media or interpersonally) suggests that existing framing research in environmental communication is best complemented by the concept of problematization, which Weder et al. (2019a) has previously introduced as part of sense making processes.

Our paper's use of problematization is rooted in a view of discourse as constitutive processes and the definition provided by Sandberg and Alvesson (2011). We understand problematization to be showing how certain beliefs and opinions about a topic or field are problematic. Following Foucault (1988), problematization means to investigate how an issue is constructed as an issue, as well as how it is classified and contextualized (Deacon, 2000; Bacchi, 2012); in other words, an issue becomes “an issue” due to how it is constructed and/or contextualized by a process that we conceptualize as problematic. Problematization thus offers a deeper understanding of framing as a process of deconstruction (problematization) and (re)construction [remedy promotion, solution orientation, normativity, with a reference to Entman (1993)].

Problematization involves analyzing the factors that constitute both issue and context (Akor, 2015). Additionally, problematization is discussed as the constitutive part of framing processes, mainly in Entman's concept of framing as problematization and moral evaluation, referring to causal relationships between arguments as well as promoting remedy (1993). Thus, in our paper, framing is considered the process of organizing public communication. As long as frames are considered organizing ideas (Gamson and Modigliani, 1989) they “are contested by journalists and the audience, new ones are selected and others may disappear without the frames themselves undergoing any change” (van Gorp, 2007, p. 64). Using problematization, a certain degree of morality, and different ways of argumentation with a solution at hand, the amount of attention an issue receives and the legitimation or exclusion of its related arguments can be influenced (Newman and Nisbet, 2015).

Water issues are communicated through different interpretive patterns (Shah et al., 2002). If communicative problematization can be characterized as a process, it can also be considered an action that starts by recognizing a situation or idea as problematic and then increasing the level of involvement using various patterns and frames (Crable and Vibbert, 1985). The 2018 Cape Town water crisis stimulated framing processes in political, economic and environmental discourses. Water as a natural resource was problematized and had a relatively high degree of morality in the sense of who or what might be responsible for the drought and which political options or actions should be considered over others (Nisbet, 2009).

In our paper, we trace back the problematization of water as a scarce natural resource and identify the “over-moralization” of the issue with the apocalyptic frame of “Day Zero” in public discourses. Specifically, we aim to identify the exact patterns lying behind the discourse on water scarcity by analyzing the public discourse of the water crisis in Cape Town, SA from a media perspective (Study Part 1), as well as the problematization of “Day Zero” and related framing processes from an individual perspective, i.e. the local community's meaning making processes of this crisis (Study Part 2). Ultimately, our analytical focus on framing of the water crisis in Cape Town in 2018 offers new insights as to the regularities and irregularities of water communication as a future topic in environmental communication research.

Apocalyptic Rhetoric

Zamora (1982) explains that the term “apocalypse” is used in traditional Judeo-Christian religion to forecast, reveal, or envision the world's annihilation. Apocalyptic rhetoric thus describes a narrative telos, or end-point, that implicitly or explicitly predicts when the current world order will be dramatically destroyed and replaced with a new world order (Brummett, 1984, 1991). The common narrative is of a tragic ending, which assumes that the oncoming experience is determined and decided by uncontrolled external forces (Wojcik, 1996). Foust and Murphy (2009) explain this outcome by saying, “Like God's wrath or nuclear war, the apocalyptic scenario is so much greater than humanity (let alone individual human effort), that there seems little hope for intervention” (p. 154).

Following Burke (1984), our paper views apocalyptic frames through two lenses: comic and tragic. A tragic apocalypse is illustrated through humanity's acceptance of a prophesied ending (Burke, 1984) in which the telos is catastrophic and unavoidable (Foust and Murphy, 2009). By contrast, a comic apocalypse is ill-defined and considered avoidable if the right human actions are taken (Foust and Murphy, 2009). Importantly, a comic apocalypse is more forgiving and perceives humanity as having made a mistake (Burke, 1984). O'Leary (1993) also differentiates tragic and comic apocalypses as having closed and open-ended interpretations of time, respectively. In environmental communication scholarship, apocalyptic framing has largely been applied to environmental films (Foust and Murphy, 2009; Salvador and Norton, 2011), but these media explorations open the door for other environmental applications, such as the media discourse analyzed in this paper.

Problematization of Water Scarcity in the Media

The effectiveness of news reporting on environmental and resource management issues has led media to play an increasingly key part in the environmental communication field (Jurin et al., 2010). Most importantly, the media informs the public about events and reports information, influences the public's perceived salience or importance of issues, shapes public opinions, and initiates and encourages civic engagement (Moon, 2013).

Previous research on drought around the world—e.g., in Athens (Kaika, 2003, 2006), in California (Nevarez, 1996), and in Sydney and London (Bell, 2009)—reinforces the assumption that media coverage of drought contributes to public awareness and sense-making of not only droughts specifically, but also climate change and environmental issues in general (O'Donnell and Rice, 2008; Bell, 2009). In South Africa, water issues are more commonly assessed from a global perspective, such as Bond and Ruiters (2001) examination of post-apartheid drought and flood discourse. Even though environmental issues are infrequently approached from a local perspective (Marvin and Guy, 1997; Lawhon and Patel, 2013), water discourses in the media specifically present a strong local reference (Weder et al., 2019b) since “the local scale [is] a site of action where change can happen and where ordinary people feel empowered to contribute” (Lawhon and Makina, 2017, p. 240).

In Study Part 1 we therefore aim to combine these narrow and broad media perspectives by comparing and contrasting local and international discourse(s) of the Capetonians' water crisis. To do so, we conducted a discourse analysis through which different criteria, structural patterns, rules and resources of the meaning making process of water discourses can be identified and analyzed.

Study Part 1

Research Design

In order to understand how public discourse about the 2018 water shortage in Cape Town was constructed, Study Part 1 explores media discourses surrounding “Day Zero” to gain insight into rhetorical turning points during the Cape Town water crisis. To this purpose we ran a media analysis of n = 111 news articles during three different stages of the water crisis: pre-, height of, and post-crisis.

For this study, the term “Day Zero” was considered to have apocalyptic potential due to its reference to a day when Capetonian taps would be turned off and everyday life in Cape Town would cease to exist in its current state. This consideration is supported by the previously mentioned explanation that apocalyptic rhetoric is a useful tool to describe narrative telos, or endpoints, and to predict either implicitly or explicitly that the current world order will be dramatically destroyed and replaced by a new one (Brummett, 1984, 1991). This approach to apocalyptic rhetoric is also echoed by O'Leary (1994), who explains: “The tragic and comic frames are interpretative devices for lending meaning to personal and collective human experience by arranging events into a coherent system of signs. As such, they serve as resources for the invention of arguments that enable people to explain otherwise terrifying or anomalous events and incorporate them into a structure of meaning. The comic assumption that human being are free actors and the tragic assumption of divinely ordained fate do not only determine the shape of historical narratives; they also serve as elements of self-definition that constrain and enable arguments for different audiences” (p. 92).

The use of apocalyptic frames is used here to analyze the public discourses on “Day Zero.”

Data Collection

Our analysis of the public discourse on Cape Town's water crisis focused on media discourses in newspapers. Newspaper articles referring to “Day Zero” were collected between June 1, 2017 to June 1, 2018. This time frame was selected in order to allow for an analysis of the three stages (pre-, height of, and post-) of the water crisis. A NewsBank search for the keyword “Day Zero” in the headline and “water” in the lead/first paragraph resulted in 251 newspaper results worldwide. In order to allow a comparison between local and international media discourses, results from non-Capetonian South African newspapers were excluded from the final data sample. After data cleansing, i.e., removing newspaper articles duplicated across outlets, n = 83 articles in Cape Town-located newspapers and n = 28 articles in international and/or non-South African newspaper were included in the final data sample (n = 111).

Both data groups (local vs. international news articles) were organized chronologically and divided into three stages: pre-, height of, and post-crisis. The pre-crisis stage was defined as the time frame between June 1, 2017 and January 17, 2018, i.e., any news that occurred before Mayor de Lille's January 18, 2018 press announcement of “Day Zero” as April 21, 2018. The height of crisis stage was defined as the period between January 18, 2018 and February 13, 2018. The post-crisis stage was defined as the lapse of time between February 14, 2018 and June 1, 2018, when data collection ceased.

Data Analysis

After data collection and organization, the newspaper articles included in the final sample (n = 111) were analyzed by one researcher and the results compared between local and international newspapers. Following recommendations provided by Strauss and Corbin (1990), data were first analyzed using open coding, or “the process of breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualizing, and categorizing data” (p. 61). In order to understand and analyze public discourse on news media about Cape Town's water crisis, each data set was first read thoroughly for coherency and understanding. Data sets were reviewed a second time with specific attention being devoted to the identification of recurring apocalyptic concepts and themes present in each of the three crisis stages. Special consideration was given to mention of apocalyptic tropes, including disease, violence, and religion, as well as common crisis descriptions such as “avoid” and “denial.” By doing so, we were able to identify the interpretative patterns lying behind the water discourses, i.e., how they were framed, and understand how public discourses about Cape Town's water crisis were constructed.

Study Part 2—Day Zero Meaning Making Processes in Relation to Media Frames

People mainly acquire information about environmental issues from media and news reporting (Schäfer, 2015), which shapes their perceptions of the issues themselves (Adger et al., 2012). Thus, knowledge of environmental issues and related problems is predominantly media-based and can be perceived as a result of mediated debates. Media (debates) shape and construct the public's perception of environmental problems and can therefore enable or inhibit engagement (Lester, 2010; Cox, 2013; Hackett et al., 2017). This assumption led us to investigate what kind of meaning making processes were evoked in the local community by the reporting and framing of “Day Zero” discourse analyzed in Study Part 1.

Guimelli (1993) argues that meaning-making processes can work as instructions for individual behavior and direct social practices. As mentioned earlier, we understand problematization as a social construction process that starts with the recognition of an issue as problematic and increases the level of social and/or individual involvement (Crable and Vibbert, 1985). Following Weder, Lemke and Tungarat's (2019a) argumentation, we also understand problematization as a fundamental concept in sustainability and environmental research, because without the problematization of an issue, there is no engagement in finding a solution. Furthermore, problematization—as a core process of permanent stimulation of dissent and legitimization of dominant arguments—allows for the reflection of common knowledge or common-sense issues (Weder, 2017), as well as the development of new viewpoints and critical thinking (Crotty, 1998).

As in Study 1, our Study 2 also applies Entman's (1993) framing approach from a communication perspective, complementing the previously mentioned concepts of problematization. In doing so, we are able to detect the frames, i.e., the interpretative patterns through which issues about the water crisis in Cape Town is communicated. In order to analyze and understand how Cape Town's water crisis and meaning-making process is framed by the local community, we ran a case study in Cape Town in May 2018, just before “Day Zero” was postponed for the second time, addressing the following questions:

• RQ1: Which interpretative patterns construct the local community's meaning making processes of “Day Zero”?

• RQ2: How does the local community respond to the changing environmental scenarios?

• RQ3: What role do the media play?

Research Design

The purpose of qualitative research is to gain a deeper understanding of a phenomena rather than achieve generalizable results. Therefore, to answer RQ1, RQ2 and RQ3, we ran a case study in Cape Town. In May 2018, just before “Day Zero” was rescheduled for the second time, we conducted 12 semi-structured and problem-centered interviews with exponents of the local, urban community (Spinks et al., 2017). We chose semi-structured, guided interviews, since the guidelines serve as a thread in order to structure the conversation. The use of guidelines assures that certain topics are addressed and allows comparability between different cases, as they provide a thematic framework. In addition, semi-structured interviews are suitable to identify and highlight previously unknown qualitative issues and trends, as well as to explore new areas within the scope of the research interest.

The interview partners for our case study were chosen using a system called “critical snowballing,” which means finding suitable interviewees based on recommendations from former interview partners (Brodschöll, 2003). In order for the snowball sampling system to work, the identification of the first informant is crucial (Penrod et al., 2003). For our case study in Cape Town, the first interviewee was selected due to the strong local and international media presence of her non-profit organization during the water crisis, which established her as a key actor with a strong and far-reaching network related to our research interest1. This way, we were able to conduct 12 interviews with exponents of Cape Town's local community, namely four activists, two journalists, two environmental scholars, and four everyday people directly affected by the water shortage. We concluded the snowballing sample system with the 12th interview, as we had reached data saturation and no new information could be attained (Guest et al., 2006). The 12 semi-structured interviews were fully transcribed and analyzed using the qualitative content analysis by Mayring (2014), following an inductive approach. This type of qualitative content analysis was selected because it allows a systematic, rule- and theory-based analysis of communication, instead of a “free” interpretation of the material. The inductive approach enabled the forming of categories directly from the research material so as not to distort the essence of the written and/or spoken material and its content. In this procedure, the categories were developed inductively based on the text material along a selection criterion determined by theoretical grounds. In addition to the selection criterion, the content analytical rules for inductive category formation required the specification of a level of abstraction, on which categories were phrased (Mayring, 2014). Looking at RQ1, we categorized all text passages in which “interviewees reported on their personal perception of Day Zero and the reasons for it” (selection criterion). Whenever the selection criterion applied to a text passage, a new category was formulated or an existing inductive category was assigned to the text passage. The names of the categories were formulated as “concrete aspects and reasons for Day Zero” (level of abstraction). Using this process, the material was organized into categories and made generalizable, which allowed for its analysis on a higher abstraction level and for a connection to be made between interviews and the building of issue clusters.

The inductive content analysis was performed using the online analysis tool QCAmap. This tool offers the ability to share the project with a second coder through a so-called “inter- coder-agreement” that allows coding processes and results to be compared. The comparison of two analysts coding the same material actually gives a measure of objectivity, since research results are independent from the researching persons (Mayring, 2014).

Results

Results Study Part 1—Public Discourses on “Day Zero”

In Capetonian newspapers, discourses related to “Day Zero” were most prominent during the height of crisis stage and least prominent during the pre-crisis stage, peaking in February 2018. In international and non-Capetonian newspapers, the “Day Zero” issue was most prominent during the post-crisis stage, while no articles could be found during the set pre-crisis stage.

Pre-crisis

During the pre-crisis stage, Capetonian discourses on the water crisis were framed as a comic apocalypse. Here, “Day Zero” was framed as a worst-case scenario that could be avoided: for example, Premier Helen Zille was quoted as saying, “Although the drought in the Western Cape is serious, there is no need to panic because the provincial government is doing everything it can to avoid ‘Day Zero' and not run out of water” (Measures in place to avoid water doomsday, 2017). Other outlets described Day Zero with potentiality overshadowed by uncertainty that would merely result in a “close call” (Day Zero delayed 2 months, 2017) as long as residents followed prescriptions. Later in the pre-crisis stage, mentions of avoidance were accompanied by clarifying language that explained means of solving the problem, communicated as “whole-of-society” efforts such as “Day Zero can only be avoided if we work together in partnership” (Attempting to push back Day Zero, 2017). Here, media discourses on “Day Zero” were firmly associated with an air of collective responsibility and teamwork.

Height of Crisis

As the water crisis in Cape Town escalated, so too did the media discourse about “Day Zero.” During the transition from the pre-crisis to the height of crisis stage, “Day Zero” took on a more concrete meaning, both locally and internationally, and became defined as the day when city taps would be turned off.

News coverage in Capetonian newspapers became more detailed, supported by shared extractions from FAQ documents and concrete explanations of what “Day Zero” would entail, such as water queuing and military oversight of water collection sites, that demonstrated Capetonian media's firm acknowledgment of the crisis. On an international level, the discourse around “Day Zero” consisted of storytelling about Cape Town's daily life, with articles detailing city mandates of two-minute showers, drained swimming pools, or minimal toilet flushing, as well as criticism about the city's ability to transition if “Day Zero” was reached and needed to be enacted.

During the same time that international news coverage about Cape Town's water crisis began, local newspapers reported on Capetonians' confusion related to communication about “Day Zero”: “The city has no plans to avoid Day Zero,” an op-ed in The Cape Times stated, “and they are clueless of what will happen then” (Water Crisis Coalition protest, 2018). This confusion in the reported meaning making process of the local population coincides with a twofold apocalyptic framing narrative in which “Day Zero” was communicated simultaneously as both a comic and tragic apocalypse. As in the pre-crisis stage, some local newspapers continued to frame “Day Zero” as a comic apocalypse that could be avoided through teamwork and commitment, with one article quoting Cape Town's Deputy Mayor Ian Neilson as saying, “[…] it is still possible to push back Day Zero if we all stand together now and change our current path” (Day Zero April 12, 2018). This corresponds with the local community view, which saw Day Zero as something that could still be averted.

Comparatively, others communicated “Day Zero” as a tragic apocalypse. This apocalyptic framing was supported by a narrative climate of fear or anxiety related to potential or existing dangers of “Day Zero's” arrival. In one case, the Daily Voice published an article in which a city resident expressed panic at the realization that Day Zero was truly coming: “The worst case scenario is unthinkable. To prevent outbreaks of diseases, schools and businesses will have to close, prices of everything will skyrocket as a result, and desperate people will attack anyone even just suspected of having water. Forget about cash van robberies. There will be water tanker heists and armed robbers will leave cell phones and TVs behind, while making off with bottles of water” (Live as if it's Day Zero already, 2018). Taken together, this kind of news reporting suggests a paralyzing acceptance of an inevitable “Day Zero” disaster scenario.

Our analysis also shows a small but significant local meaning making process related to the framing of “Day Zero”: some local news framed Cape Town's water crisis as a hoax and presented conspiracy theories to explain it away, giving “Day Zero” a positive meaning or rejecting “Day Zero's” apocalyptic potential entirely.

Post-crisis

In the post-crisis stage, the framing of “Day Zero” as both a comic and tragic apocalypse continued. On the one hand, local news coverage continued to communicate the need for persistent community commitment in order to avoid and/or overcome “Day Zero,” as well as communicate a more general need for environmental changes to avert future crises. On the other hand, even after “Day Zero” was repeatedly postponed, local newspaper coverage continued to mention tragic apocalyptic themes of inevitability and disaster. Some were apocalyptic stereotypes, such as theft, vandalism of water supplies, or mentions of diseases and illness. Still, others persisted with framing “Day Zero” as a hoax “conjured up by the City of Cape Town to intimidate residents into saving water and to cause fear and panic” (Day Zero a Big Con, 2018).

Results show that the post-crisis news coverage of Cape Town's water crisis led to two opposite meaning making processes in the local community: one in which Capetonians were totally aware of and educated about the effects and harms of “Day Zero,” and another in which Capetonians were confused about “Day Zero's” origin and shifting temporality. The first group is best identified in a Cape Argus article in which school children were interviewed about their awareness of the water crisis—and they clearly were aware: “I know we [sic] running out of water and it makes me scared because water is life and we can't live without it,” one of them said fearfully, with another saying, “I get tired when people tell me I must save water every time because I know I must” (Schools produce Day Zero ‘water heroes', 2018). By contrast, a separate Cape Argus article interviewed ANC Western Cape spokesperson Yonela Diko, who stated frustratedly, “Many people in the Western Cape remain in the dark as to the cause, how did we get here, and who's responsible. Was Day Zero even real?” (No tariff drop, 2018).

Whereas Capetonian post-crisis public discourses were Cape Town-focused, international and non-Capetonian post-crisis news reporting was mostly nation-specific, full of self-comparisons and predictions of which country would and/or could be the next one to face such a water crisis. Although it is impossible to know the specific reason for international media's propagation of the “Day Zero” metaphor, some discourse expressed that using the term “Day Zero” was helpful in visualizing the gravity of water crises: “Cape Town is a really good example of what might happen in the future in many other places,” explained University of Cape Town hydrologist and climatologist Piotr Wolski when speaking to The Australian, “I hope that other cities will learn a lesson from us” (Steinhauser, 2018). Among many, a sentiment was expressed that water security and accessibility could impact any area, and that little separated their own locations from the Day Zero fate that Cape Town faced. In fact, Australia, Pakistan, Egypt, India, Zimbabwe, the Middle East, and countries of North Africa all disseminated articles contemplating their position and relationship to global water security.

This apocalyptic framing of “Day Zero” was mostly comical and critical of the term “Day Zero” itself due to its sense of finality: “Zero has the connotation that this is the end. It doesn't give us hope. But we are responsible. We can do something. We can avert it” (Pellot, 2018). Nevertheless, the minor conspiracy narratives shared by local news coverage also appeared in some international media reporting.

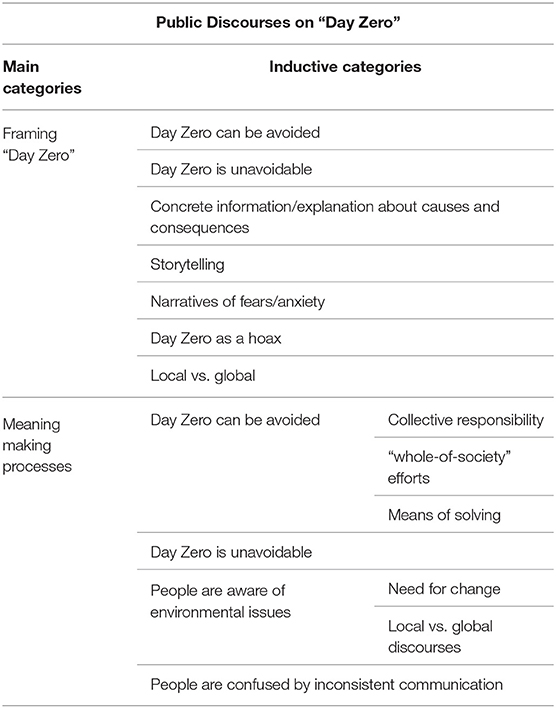

In sum, our analysis of local and international news coverage of “Day Zero” not only shows multiple and at times conflicting rhetorical narratives and frames of the water crisis, but also a multitude of meaning making processes in the local community (see Table 1). Results of Study Part 2 address the latter more thoroughly.

Results Study Part 2—Meaning Making Processes

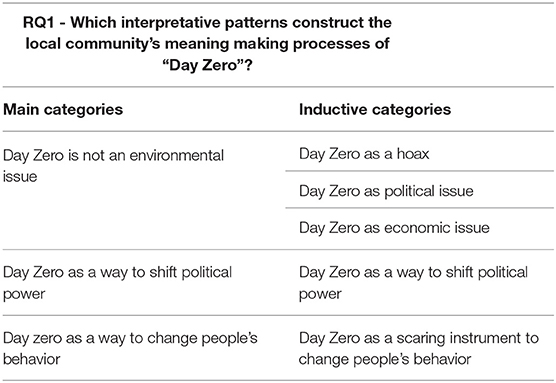

RQ1 aimed to identify the interpretative patterns that constituted the local community's meaning making process of Cape Town's “Day Zero.” The qualitative content analysis of the 12 semi-structured interviews revealed that “Day Zero” is not perceived as an environmental issue, but rather as a vehicle to serve multiple purposes (see Table 2).

The first framing of “Day Zero” conforms to the confusion in the meaning making process of Cape Town's water crisis due to controversial and opposite news reporting, as shown by Study Part 1, especially in the height of and post-crisis stages. In particular, the framing of “Day Zero” as not an environmental issue is more present in the narratives of the interviewed everyday people, who seem to adopt the framing of “Day Zero” as a hoax, as found in Study Part 1.

Hence, interviewees argue that “There IS water in Cape Town” (Local Resident 1); “We HAVE [water] resources here. If we look about why the city was founded, it was founded because we have water here” (Activist 3), and explain their water crisis as a result of economic and/or political decisions: “One dam is almost empty, but others are full. Those dams that are full don't belong to Cape Town anymore, because they were sold [to multinational corporations]” (Capetonian Tourist Guide 1); “We've got a complete mismanagement of the water source. […] There isn't even knowledge of what water sources we have” (Environmental Journalist 1); “Day Zero was more a political threat, you know, more than anything else” (Activist 2).

Framing the Capetonian water crisis as a political issue is also evident from the perception of “Day Zero” as a vehicle to serve diverse purposes. Here, our results show how “Day Zero” is perceived as an instrument to (1) shift political power, as well as to (2) change people's behavior. The former meaning making process is related to the double framing of water as something powerful and as a political issue, which in turn is able to shift political power: “It's a bit cynical but it is actually the ANC interest to see the DA fail, because they don't control this [water scarcity] problem” (Local Resident 2); “Water is powerful. [.] the water could be a political thing to gain power because now the ANC [.] can be like ‘ok, if you vote for us, we will bring you water'” (Capetonian Tourist Guide 2).

Water scarcity and Cape Town's water crisis is therefore problematized and framed as a political issue that is used by political parties to change people's political orientation: “In the City of Cape Town there was the extra thing [.] province is run by the official opposition party whereas the country is run by the ANC, and it became [.] let's say a political construction. So, national government owns all the water and provincial, local government has to get that water to people. So, in the case of Cape Town [.] municipal government were saying ‘well, national government needs to help us more'[.] you know, if one party fails it makes the other party look better or they can use it as an excuse”(Environmental Journalist).

The perception of “Day Zero” as a vehicle to political propaganda and to shift political power in turn reflects the framing of “Day Zero” as a comic apocalypse in the news media, since it is perceived as being constructed by political parties and therefore resolvable.

The understanding of “Day Zero” as a comic apocalypse is also supported by the second meaning making process of “Day Zero,” where it is used as an instrument to (2) change people's behavior. The use of the “Day Zero” scenario is therefore seen as a scaring instrument in order to change Capetonian's water wastage behavior, as mentioned by our interview partners:

“I agree with the'Day Zero Method', because it's an immovable, irrefutable position to say'we will run out of water, you have to cut back to 50 liters a day”' (Environmental activist 1). This, in turn, supports the view of “Day Zero” as being something avoidable through teamwork and commitment: “I think they were just scaring people, so that they start save water. [.] There has never been a Day Zero” (Local resident 1); “They said [.] if we don't start using water sparingly, [.] they would switch your area off, and there would be designated water stations, where you will have to go and full up. This is quite scary, imagine went to line up for water” (Capetonian Tourist Guide 2).

In sum, related to RQ1, we can assert that the local community's meaning making processes of “Day Zero” is constituted by framing water as powerful and a vehicle to serve multiple purposes, especially political ones, revealing a strong politicization of the “Day Zero” frame. Our results furthermore support the results of Study 1, framing “Day Zero” as a comic apocalypse, i.e., constructed and therefore avoidable.

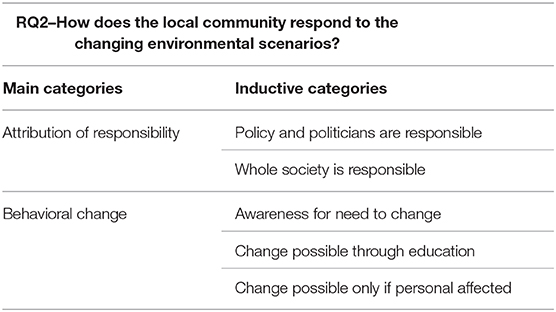

In a second step, we wanted to understand how the local community responds to the changing environmental scenarios (RQ2) caused by the water crisis. Our results (see Table 3) show that Capetonians' response consisted primarily in trying to find who's responsible for the situation. Furthermore, our analysis shows a split in the attribution of responsibility between less-educated and highly-educated people. The former, which are also the most affected by the water shortage, mostly blame policy: “Who do you think is responsible for it? The government. No one else” (Local resident 2); “So, they're not building new dams and not building storage capacity. So, you're creating a crisis, a water shortage crisis” (Capetonian Tourist Guide 1); “There is no deny here—you know we are in the shit. But still nor, the politicians haven't embrace it” (Local resident 1). This responsibility attribution to the political system is consistent with the framing of the water crisis as a political issue. The latter recognize policy's role in the crisis, but see responsibility as a whole of society issue: “It's political AND that's with the people as well. I feel that, in a way, South Africans we are wasteful as a culture. […] we are wasteful people and also with education, I'm guessing, in school. We don't learn how to use things SPARINGLY. You know?” (Environmental scholar 1);

“This perception that government [.] are responsible. I think that's wrong. I think it's time that we realize that we have highly complex social structures and cities and outland areas and we need business, and civil society and government, and equal parts to play roles on how we can modify and live our modern life” (Activist 1); “There are water sources here. Maybe not enough for the kind of quantity that is needed but we have / If we were living more sustainably and more conscious of the fact that we have to […] collect our rain water, recycle our water, not flush our toilets with pure sweet water, those kind of things. […] It's about how do we influence society enough to remember how to live more sustainably, especially with water” (Activist 3).

This understanding of responsibility attribution additionally supports the framing of “Day Zero” as a comic apocalypse, which can be avoided through collective commitment. This perception is further confirmed by our analysis. Capetonians respond to the changing environmental scenarios not only by trying to identify who's responsible for the crisis, but also trying to change community behavior through (peer to peer) education: “I have a lot of friend that came down and they were like: ‘I will take like 5 minute shower' And I was like ‘NO you can't, you CAN'T do that', so explain them where we are and how we managed with that” (Activist 2).

“You get to the school and you talk to the children [.] and say: [.] This is your future. [.] If you brush your teeth in a certain way, flush your loo in a certain way, shower in a certain way [.] If you just do that for yourselves and you monitor the people in your house, that would make a massive impact already. They go home into their community and they talk to their parents and their siblings […] Your goal is community-based solutions” (Environmental scholar 2).

In this context we have to mention another important finding: our interviews have emphasized that behavioral change is only possible if people are directly affected in their everyday life by a situation: “People don't act unless it actually affects their pocket” (Local resident 4); “But it's not personal if the water is drying and you're not feeling it” (Activist 3); “People wait until the taps run dry before they care about it” (Environmental Journalist 2).

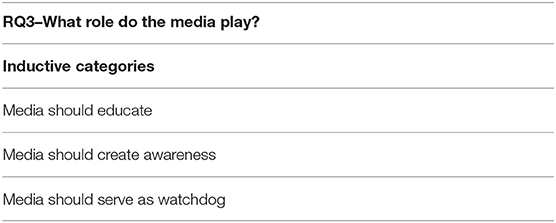

In the last part of our analysis, we wanted to refer again to Study 1, by investigating how Capetonians perceive the role of the media in the water crisis (RQ3). Results show how local communities perceive media's role as threefold (see Table 4): media should educate people to water saving behavior, create awareness related to water scarcity and other environmental issues, and serve as watchdog, especially when it comes to political misbehavior: “There are so many roles, which can be played by media. They can criticize, they can build and destroy at the same time”(Local resident 3); “Look at Facebook! I mean we had an incredible spread of knowledge […] for the most part it is an incredible tool to get messages out” (Activist 1); “I mean the question is: social media companies are so powerful […]. So get a deeper level on, what's behind what is posted and get more, deeper explanations of what, what the dynamics of the situation are. I think social media is great. […] I think it's an example of a healthy society, when your media can report deeply and truly on an ACTUAL state of affairs” (Environmental Journalist 1); “I think that they should take the gloves off and I think that they should name and shame” (Environmental Activist 2).

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to identify and analyze discourses about Cape Town's water crisis. For this purpose, we ran two case studies in order to focus on both public as well as local community discourses and framing. In Part 1 of our study, we analyzed media discourses in local and international newspaper during three stages of the crisis (pre-, height of, and post-crisis). In Part 2 of our study, we focused on the local community ‘s meaning making process of “Day Zero.”

Our results show that local and international reporting of “Day Zero” relies on different rhetorical narratives. Especially in the height of crisis stage, news reporting produced both comic and tragic apocalyptic narratives. This clearly showcases the apocalyptic rhetorical power of the “Day Zero” term in alignment with previous research (Burke, 1984; O'Leary, 1993; Foust and Murphy, 2009). Unfortunately, the apocalyptic power encased in the term “Day Zero” was strongest during the transition from the height of crisis stage into the post-crisis stage at a local level, and in international discourse during the post-crisis stage itself. In particular, communicating “Day Zero” as a tragic apocalypse in the post-crisis stage led to different interpretive processes of the water crisis that often linked to conspiracy theories. This created confusion for the local community and caused two different meaning making processes. On one side, there were the “aware Capetonians” who perceived “Day Zero” as real and were aware of and scared by its effects; on the other side, there were the “skeptic Capetonians” who perceived “Day Zero” to be a hoax (these two sides can also be seen in the results of Study Part 2). In particular, the “skeptic Capetonians” framed “Day Zero” as a hoax and as a crisis constructed by policy in order to serve their own purposes, thus positioning it as a resolvable problem. This shows how environmental issues are used as a vehicle for political communication, or in other words, how environmental discourses are drawn to the political field and abused, i.e. how politicization (Roper et al., 2016) of environmental issues happens.

The communication around the (twice-postponed) “Day Zero” in Cape Town is also a very fruitful example of the digital disrupted, post-truth communication that happens with environmental issues today. The metaphor “Day Zero” as well as the degree of water scarcity behind the concept, is calculated by the amount of water stored in dams and by the daily rate of usage: in other words, the problem of “Day Zero” necessitates public acceptance of variability based on changing environmental facts. Our study shows that even though environmental variance should be expected on a factual level, the use of a term or metaphor of “Day Zero” is operationalized in too many different ways, not all of which are related to the factual situation.

However, it has to be acknowledged that remedial actions taken by the national government, City Council, and citizens to curb water usage ultimately led to the postponement of “Day Zero.” Examples of these actions include the limiting of consumption by the agricultural sector by the national government, the reduction in main pressure by the Council, and citizen water saving efforts via a series of well-communicated stages, leading up to Level 6 water restrictions. Since the interviews were conducted after “Day Zero” was postponed for the second time, it is conceivable to assume that these (governmental) measures have influenced the perception of the water crisis as a comic—i.e. resolvable—apocalypse. In fact, the “aware Capetonians” did frame “Day Zero” as a comic apocalypse that could be avoided through community engagement, which can be supported by education mostly spread by the media. Here, however, the use of “Day Zero” as a comic apocalypse, or as an avoidable situation, should be emphasized. The results of Study Part 2 show that people are willing to change their (water related) behavior only if a certain situation directly affects their everyday life, i.e. in this case, only if they really run out of water. This is particularly true for “skeptic Capetonians” who already doubt the reality of “Day Zero.”

Communicating “Day Zero” as a comic apocalypse thus creates a dilemma. On the one hand, this framing can enable the media to do what it does best: act as a warning, create more awareness, and show misconduct so that catastrophe can be avoided. On the other hand, if the catastrophe is avoidable, it means it is not (yet) real. Using this kind of narrative makes early intervention on non-aware people difficult and behavioral effects will probably not be achievable. This problem can also be recognized in the tragic framing of “Day Zero,” as communicating an event or a catastrophe as unavoidable may also cause resignation in aware people.

Limitations

The presented analysis does incur some limitations, mostly due to the nature of our two studies as case studies. Related to Part 1 of the study, we want to address the sample especially related to the data collection. The three analyzed stages —pre-, height of, and post-crisis— were self-defined by the authors and determined independently to the crisis' development. Self-defining these time lapses of course affects the way discourses are viewed and interpreted, and it is possible that differently defined turning points and time periods would lead to slightly different findings. This is particularly true for the pre-crisis stage, where no comparison between international and local news was possible. A different definition of time periods may also lead to a different sample size. Further researchers are therefore encouraged to amplify time periods and sample size.

The same limitation is also present in Part 2. As a case study, the sample size is rather limited. Therefore, further research should address a larger group of interviewees. As for this second part of the research project, conducting the interviews at a different time could lead to different results. Running additional qualitative studies could provide interesting comparable data to identify changes and/or similarities in the water crisis' framing.

Nonetheless, our analysis of communication, narratives, and framing of “Day Zero” can be seen as a useful example to point out challenges, dilemmas and difficulties of environmental communication that undoubtedly require further and deeper analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethic committee at the Department of Media and Communications, University of Klagenfurt. Contact: DV. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CB coordinated part 1 of the study. DV coordinated part 2 of the study and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors have contributed to the conception of the paper, its underlying theories, the methodological approach as well as the discussion and implications of results.

Funding

The author acknowledges the financial support by the University of Klagenfurt.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^Due to the anonymization commitment, no further details about the organization and/or the interviewee(s) can be disclosed.

References

Adger, W. N., Barnett, J., Brown, K., Marshall, N., and O'Brien, K. (2012). Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 112–117. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1666

Akor, O. (2015). “Problematization: the foundation of sustainable development,” in International Conference on African Development Issues (CU-CADI) 2015: Information and Communication Technology Track (Igbara Odo: Covenant University), 77–83.

Atanasova, D. (2019). Moving society to a sustainable future: the framing of sustainability in a constructive media outlet. Environ. Commun. 13, 700–711. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2019.1583262

Bacchi, C. (2012). Why study problematization? Making politics visible. Open J. Polit. Sci. 2, 1–8. doi: 10.4236/ojps.2012.21001

Bell, S. (2009). The driest continent and the greediest water company: newspaper reporting of drought in Sydney and London. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 66, 581–589. doi: 10.1080/00207230903239220

Bennett, J. (2003). Environmental values and water policy. Aust. Geogr. Stud. 41, 237–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8470.2003.00232.x

Bond, P., and Ruiters, G. (2001). “Drought and floods in post-apartheid South Africa,” in Empowerment through Economic Transformation, South Africa ed M. M. Khosa (Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council), 329–375.

Boykoff, M. T. (2011). Who Speaks for the Climate? Making Sense of Media Reporting on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511978586

Brodschöll, P. C. (2003). Negotiating sustainability in the media: critical perspectives on the popularisation of environmental concerns. (MA Thesis). Curtin University of Technology, Faculty of Media, Society and Culture, Perth, Australia.

Brüggemann, M., and Engesser, S. (2017). Beyond false balance: how interpretive journalism shapes media coverage of climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.11.004

Brummett, B. (1984). Perennial apocalyptic as a rhetorical genre. Cent. States Speech J. 35, 84–93. doi: 10.1080/10510978409368168

Chutel, L. (2019). How Cape Town Delayed its Water-Shortage Disaster—at Least Until 2019. Quartz. Available online at: https://qz.com/1272589/how-cape-town-delayed-its-water-disaster-at-least-until-2019/(accessed May 9, 2018).

Cox, R. (2013). Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere, 3rd Edn. Los Angeles; London; New Delhi; Singapore; Washington DC; Boston, MA: SAGE.

Crable, R. E., and Vibbert, S. L. (1985). Managing issues and influencing public policy. Public Relat. Rev. 11, 3–15. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(82)80114-8

Crotty, M. J. (1998). Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. London: SAGE Publications.

Day Zero a Big Con (2018). Day Zero a Big Con, Says Activist Group. Weekend Argus. Retrieved from NewsBank. (accessed February 18, 2019).

Day Zero April 12 (2018). City Steps Up Water Saving Plans as Maimane Will Manage Crisis. Daily Voice. Retrieved from NewsBank. (accessed January 24, 2018).

Day Zero delayed 2 months (2017). The Cape Times. Retrieved from NewsBank. (accessed November 17, (2017).

de Vreese, C. (2005). News framing: theory and typology. Inform. Design J. 13, 51–62. doi: 10.1075/idjdd.13.1.06vre

Dearing, J. (1995). Newspaper coverage of maverick science: creating controversy through balancing. Public Understand. Sci. 4, 341–361. doi: 10.1088/0963-6625/4/4/002

Diprose, K., Fern, R., vanderbeck, R. M., Chen, L., Valentine, G., Liu, C., et al. (2018). Corporations, consumerism and culpability: sustainability in the British Press. Environ. Commun. 12, 672–685. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2017.1400455

Dolnicar, S., and Hurlimann, A. (2010). Australians' water conservation and attitudes. Austr. J. Water Resour. 14, 43–53. doi: 10.1080/13241583.2010.11465373

Dryzek, J. S. (1997). The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

European Commission (2018). Water Scarcity and Droughts in the European Union. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/quantity/scarcity_en.htm (accessed September 5, 2019).

Foucault, M. (1988). Politics, Philosophy, Culture: Interviews and other Writings, 1977–1984. New York, NY: Routledge

Foust, C. R., and Murphy, W. O. (2009). Revealing and reframing apocalyptic tragedy in global warming discourse. Environ. Commun. 3, 151–167. doi: 10.1080/17524030902916624

Gamson, W. A., and Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. Am. J. Sociol. 95, 1–37. doi: 10.1086/229213

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Guimelli, C. (1993). Locating the central core of social representations: towards a method. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 23, 555–559. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420230511

Hackett, R. A., Forde, S., Gunster, S., and Foxwell-Norton, K. (2017). “Introduction,” in Journalism and Climate Crisis: Public Engagement, Media Alternatives, eds R.A. Hackett, S. Forde, S. Gunster, and K. Foxwell-Norton (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 1–19. doi: 10.4324/9781315668734-1

Hervé-Bazin, C. (2014). Water Communication. Analysis on Strategies and Campaigns from the Water Sector. London, UK: IWA Publishing. doi: 10.2166/9781780405223

IWA International Water Association (2019). Public and Customer Communications. Available online at: https://iwa-network.org/groups/public-and-customer-communications/ (accessed September 5, 2019).

Jöborn, A., Danielsson, I., Arheimer, B., Jonsson, A., Larsson, M. H., Lundqvist, L. J., et al. (2005). Integrated water management for eutrophication control: public participation, pricing policy, and catchment modeling. Ambio 34, 481–488. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-34.7.482

Jurin, R. R., Rousch, D., and Danter, J. (2010). Environmental Communication. Skills and Principles for Natural Resource Managers, Scientists, and Engineers. 2nd Edn. Heidelberg: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3987-3

Kaika, M. (2003). Constructing scarcity and sensationalizing water politics: 170 days that shook athens. Antipode 35, 919–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2003.00365.x

Kaika, M. (2006). “The political ecology of water scarcity: the 1989-1991 Athenian drought,” in The Nature of Cities: Urban Political Ecology and the Politics of Urban Metabolism, eds N. Heynen, M. Kaika, and E. Swyngedouw (London, UK: Routledge), 157–172.

Lawhon, M., and Makina, A. (2017). Assessing local discourses on water in a South African newspaper. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 22, 240–255. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2016.1188064

Lawhon, M., and Patel, Z. (2013). Scalar politics and local sustainability: rethinking governance and justice in an era of political and environmental change. Environ. Plann. C Govern. Policy 31, 10488–11062. doi: 10.1068/c12273

Liang, Y., Kee, K. F., and Henderson, L. K. (2018). Towards an integrated model of strategic environmental communication: advancing theories of reactance and planned behavior in a water conservation context. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 46, 134–154. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2018.1437924

Live as if it's Day Zero already (2018). Stop moaning and band together. Daily Voice. Retrieved from NewsBank. (accessed January 23, (2018).

Ma, A. (2018). People in Cape Town have Massively Delayed the Day they Run out of Water by using Dirty Shower Water to Flush their Toilets. Business Insider. Available online at: http://www.businessinsider.com/cape-town-postpones-day-zero-when-it-runs-out-of-water-to-2019-2018-3 (accessed March 7, 2018).

Mäki, H. (2010). Comparing developments in water supply, sanitation and environmental health in four South African cities, 1840-1920. Historia 55, 90–109.

Marvin, S., and Guy, S. (1997). Creating myths rather than sustainability: the transition fallacies of the new localism. Local Environ. 2, 313–318. doi: 10.1080/13549839708725536

Mayring, P. H. (2014). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. 12th Edn. Weinheim: Beltz. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-18939-0_38

Measures in place to avoid water doomsday, (2017, September 1). Team Western Cape working flat out to avoid ‘Day Zero,' says premier. Cape Argus. Retrieved from NewsBank.

Mekonnen, M. M., and Hoekstra, A. Y. (2016). Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2:e1500323. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500323

Mitra, R. (2018). Natural Resource Management in the U.S. Arctic: Sustainable Organizing Through Communicative Practices. Management Communication Quarterly, 32, 398–430. doi: 10.1177/0893318918755971

Moon, S. J. (2013). “From what the public thinks about to what the public does: agenda- setting effects as a mediator of media use and civic engagement,” in Agenda Setting in a 2.0 World: New Agendas in Communication, ed T.J. Johnson (Austin: Routledge), 158–189.

Nevarez, L. (1996). Just wait until there's a drought: mediating environmental crises for urban growth. Antipode 28, 246–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.1996.tb00462.x

Newman, T., and Nisbet, M. (2015). “Framing, the media, and environmental communication,” in The Routledge Handbook of Environment and Communication, eds A. Hansen, and R. Cox (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 325–338.

Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 51, 12–23. doi: 10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23

Nisbet, M. C. (2010). “Knowledge into action: framing the debates over climate change and poverty,” in Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives, eds P. D'Angelo, and J. A. Kuypers (New York, NY: Routledge), 43–83.

No tariff drop (2018). Despite Day Zero deferment—Capetonians. need to keep paying more for water explained. Cape Argus. Retrieved from NewsBank. (accessed March 13, 2018).

O'Donnell, C., and Rice, R. E. (2008). Coverage of environmental events in US and UK newspapers: frequency, hazard, specificity, and placement. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 65, 637–654. doi: 10.1080/00207230802233548

O'Leary, S. D. (1993). A dramatistic theory of apocalyptic rhetoric. Quart. J. Speech 79, 385–426. doi: 10.1080/00335639309384044

O'Leary, S. D. (1994). Arguing the Apocalypse. A Theory of Millennial Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O'Neill, S., Williams, H. T. P., Kurz, T., Wiersma, B., and Boykoff, M. (2015). Dominant frames in legacy and social media coverage of the IPCC fifth assessment report. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 380–385. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2535

Pellot, B. (2018). As Cape Town's Water Crisis Nears ‘Day Zero,' Faith Groups Spring into Action. The Morning Sun. Retrieved from NewsBank.

Penrod, J., Preston, D. B., Clain, R. E., and Starks, M. T. (2003). A discussion of chain referral as a method of sampling hard-to-reach populations. J. Transcult. Nurs. 14, 100–107. doi: 10.1177/1043659602250614

Roper, J., Ganesh, S., and Zorn, T. E. (2016). Doubt, delay, and discourse. Skeptics' strategies to politicize climate change. Sci. Commun. 38, 776–799. doi: 10.1177/1075547016677043

Salvador, M., and Norton, T. (2011). The flood myth in the age of global climate change. Environ. Commun. 5, 45–61. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2010.544749

Sandberg, J., and Alvesson, M. (2011). Ways of constructing research questions: gap- spotting or problematization? Organization 18, 23–44. doi: 10.1177/1350508410372151

Schäfer, M. S. (2015). “Climate change and the media,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, ed J. D. Wright (Oxford: Elsevier), 853–859. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.91079-1

Schäfer, M. S., and Schlichting, I. (2014). Media representations of climate change. A meta-analysis of the research field. Environ. Commun. A J. Nat. Cult. 8, 142–160. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.914050

Scheufele, D. A., and Tewksbury, T. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: the evolution of three media effects models. J. Commun. 57, 9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9916.2007.00326.x

Schlichting, I. (2013). Strategic framing of climate change by industry actors. A meta-analysis. Environ. Commun. 7, 493–511. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2013.812974

Schools produce Day Zero ‘water heroes' (2018). Cape Argus. Retrieved from NewsBank. (accessed February 22, 2018).

Shah, D. V., Watts, M. D., Domke, D., and Fan, D. P. (2002). News framing and cueing of issue regimes. explaining clinton's public approval in spite of scandal. Public Opin. Q 66, 339–370. doi: 10.1086/341396

Spinks, A., Fielding, K., Mankad, A., Leonard, R., Leviston, Z., and Gardner, J. (2017). “Dipping in the well: how behaviours and attitudes influence urban water security,” in Social Science and Sustainability, eds H. Schandl, and I. Walkers (Australia: CSIRO Publishing), (145–159.

Steinhauser, G. (2018). Dry Cape Town strains to avoid Day Zero. The Australian. Retrieved from NewsBank (accessed March 5, 2018).

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Trumbo, C. W., and O'Keefe, G. J. (2001). Intention to conserve water: environmental values, planned behavior, and information effects. Soc. Nat. Resour. 14, 889–899. doi: 10.1080/089419201753242797

UN (2018). UN Water. Water Scarcity. Available online at: https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/scarcity/ (accessed September 5, 2019).

UN (2020). About the Sustainability Development Goals. Available online at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed September 6, 2020).

UNEP (2016). Options for Decoupling Economic Growth from Water Use and Water Pollution. Report of the International Resource Panel Working Group on Sustainable Water Management, Paris.

UNPD (2006). Beyond Scarcity: Power, Poverty and the Global Water Crisis. Avilable online at: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/HDR/2006%20Global%20HDR/H DR-2006-Beyond%20scarcity-Power-poverty-and-the-global-water-crisis.pdf (accessed September 5, 2019).

van Gorp, B. (2007). The constructionist approach to framing: bringing culture back in. J. Commun. 57, 60–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00329_4.x

Water Crisis Coalition protest (2018). Water Crisis Coalition protest against clueless City's Day Zero plans. The Cape Times. Retrieved from NewsBank.

Weder, F. (2017). “CSR as common sense issue? A theoretical exploration of public discourses, common sense and framing of corporate social responsibility,” in Handbook of Integrated CSR Communication, eds S. Diehl, M. Karmasin, B. Mueller, R. Terlutter, and F. Weder (Cham: Springer), 23–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-44700-1_2

Weder, F. (2021). “Sustainability as Master Frame of the Future? Potency and limits of sustainability as normative framework in corporate, political and NGO communication,” in The Sustainability Communication Reader: A Reflective Compendium. eds F. Weder, L. Krainer, and M. Karmasin (Spinger VS).

Weder, F., Lemke, S., and Tungarat, A. (2019a). (Re)storying sustainability: the use of story cubes in narrative inquiries to understand individual perceptions of sustainability. Sustainability 11:5264. doi: 10.3390/su11195264

Weder, F., Voci, D., and Vogl, N. C. (2019b). (Lack of) problematization of water supply use and abuse of environmental discourses and natural resource related claims in German, Austrian, Slovenian and Italian Media. J. Sustain. Dev. 12, 39–54. doi: 10.5539/jsd.v12n1p39

Wojcik, D. (1996). Embracing doomsday: faith, fatalism, and apocalyptic beliefs in the nuclear age. West. Folk 55, 297–330. doi: 10.2307/1500138

Keywords: water scarcity, water crisis, framing analysis, transformative environmental issues, rhetoric analysis, Day Zero, Cape Town

Citation: Voci D, Bruns CJ, Lemke S and Weder F (2020) Framing the End: Analyzing Media and Meaning Making During Cape Town's Day Zero. Front. Commun. 5:576199. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.576199

Received: 25 June 2020; Accepted: 14 September 2020;

Published: 20 October 2020.

Edited by:

Emma Weitkamp, University of the West of England, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sibo Chen, Ryerson University, CanadaNevil Wyndham Quinn, University of the West of England, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Voci, Bruns, Lemke and Weder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Denise Voci, RGVuaXNlLlZvY2lAYWF1LmF0

Denise Voci

Denise Voci Catherine J. Bruns

Catherine J. Bruns Stella Lemke

Stella Lemke Franzisca Weder

Franzisca Weder