- 1University of the West of England, Bristol, United Kingdom

- 2Science Communication Unit, Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences, University of the West of England (UWE), Bristol, United Kingdom

Recent years have seen an upsurge in the digital environment and the reliance placed upon it by society. This case study reports on a project which sought to examine how the digital environment can be utilized for science communication, exploring the role of social media and particularly short online videos, as an effective means through which to engage the public with science, environment and conservation messages. Using as its focus a 300-mile trek around the coast of Cornwall (Sophie's Wild Cornwall) we examine how science was communicated real-time using online videos and social media over a 5-week period, as well as data from an online public opinion survey (n = 129). The observations gleaned identify a number of key themes for others wishing to adopt digital approaches within their science communication activities, including the role of web-based presenter-led narratives, the value of accessibility and interaction on social media platforms, and online videos potential for stimulating proactive, participatory engagement, and interest in an environmental context. Effective online video use requires a balance between crafting an informative yet entertaining narrative without compromising scientific accuracy; yet ultimately, social media platforms may represent a potential “stepping-stone” for practitioners to consider implementing in a journey toward “upstream engagement”.

Introduction

At a time when environmental health and biodiversity feature on many public agendas, encouraging public uptake and action for pro-environmental behaviors requires both an awareness of conservation issues, alongside opportunities for productive collaboration between science and society. Online videos, shared via social media offer the potential to create such a relationship (Hacker and Harris, 1992; Ballard et al., 2017). It is estimated that over 1.4 billion people use Facebook daily (Facebook, 2018). Whilst 800 million people use Instagram (Statista, 2018a) and 330 million people use Twitter on a monthly basis (Statista, 2018b). The explosion of digital landscapes has promoted a marked increase in the time allocated to online activity (Brossard, 2013; Andreassen et al., 2017; Marketing Magazin, 2017), and using online sources, including videos, for science information has also increased, particularly amongst 18–25 years olds (Mangold and Faulds, 2009; Bernhardt et al., 2011; Brossard, 2013; IPSOS Mori, 2014; Koohy and Koohy, 2014; Liang et al., 2014; Peters et al., 2014; Hargittai et al., 2018; León and Bourk, 2018; Huber et al., 2019). Whilst some may argue this creates a potential disconnect with the natural world it may in fact offer pertinent opportunities to “mobilize biodiversity conservation and environmentalism” (Fletcher, 2017, p. 226).

Extensive research into this “new realm” (Wilkinson and Weitkamp, 2016, p. 123) remains emerging (Brossard, 2013; Davies and Hara, 2017; Hargittai et al., 2018), with researchers who might use social media for communication activities, admitting a continued “limited understanding” about what it really is (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010). Online videos have an increasingly important influence on science and environmental communication, particularly amongst young people, but research on such sources, and the potential of their role, is also still emerging (León and Bourk, 2018; Allgaier, 2019).

Social media has facilitated large scale science-focused initiatives, notably health campaigns (Koohy and Koohy, 2014) and some environmental projects (Aldred, 2016; Ballard et al., 2017; Plastic Patrol, 2017) highlighting the far-reaching influence social media can have on actions, attitudes, and behaviors (Centola, 2010, Korda and Itani, 2013). Despite such potential, and many corporate businesses regarding social media presence as, “top of the agenda” (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010, p. 59), academic institutions are said to fall behind in their online activity (Peters et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2014; Jarreau and Yammine, 2017; Howell et al., 2019; Koivumäki and Wilkinson, 2020), despite the value it can bring for public engagement (Bernhardt et al., 2011; Wilkinson and Weitkamp, 2016). Engagement is often considered effective if it results in behavioral or attitudinal change, particularly around issues such as climate change, health, and the environment (Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Corner and Randall, 2011) and sites such as Twitter are known to facilitate such interaction outcomes (Simis-Wilkinson et al., 2018).

Social media addresses a “ready-made” audience, an integral feature of science communication practice (Holliman et al., 2009; Wilkinson and Weitkamp, 2013; Peters et al., 2014). Given the challenges often associated with reaching a target audience (Groffman et al., 2010; Ballard et al., 2017), communicators can “take advantage of where people already habitually and routinely gather, share and communicate” online (Metzger and Flanagin, 2011, p. 55). This can also allow users to see science “in the making” (Ballard et al., 2017), spurring positive change and uptake of science in society, as science happens, in real time (Peters et al., 2014; León and Bourk, 2018; Simis-Wilkinson et al., 2018).

However, identifying and evaluating the impacts of online engagement is a common obstacle for conservation organizations (Miller et al., 2004), leaving a “serious communication gap” (Spooner et al., 2015, p. 2) between conservation research and practice. This neglects to understand the motivations to participate in online endeavors (Collins et al., 2010; Kuss and Griffiths, 2011; Schou Andreassen and Pallesen, 2014; Andreassen et al., 2017) and maintains a recurring narrative in environmental science disciplines of the prevalence of one-way mass communication (Collins et al., 2010), missing opportunities to “restart” of the conversation between ecology and society (Groffman et al., 2010).

With this in mind, this case study explored how, “high-quality meaningful engagement” (Collins et al., 2010, p. 1181) can be obtained digitally. At its heart was a 300-mile science-focused trek around the coastline of Cornwall in the UK, entitled “Sophie's Wild Cornwall”, which allowed us to directly observe how an audience engages with online videos on social media, including a 22-part online YouTube series.

A Case Study: Sophie's Wild Cornwall

Cornwall is one of the most environmentally significant counties in Great Britain, hosting over 60 nature reserves, 160 Sites of Special Scientific Interest and giving rise to unique habitats and wildlife (Cornwall Wildlife Trust, 2017). Cornwall's geographical isolation can restrict its involvement with science communication (Smallcombe, 2017), meaning the content was also well-suited for online videos shared via social and digital media, engaging with audiences who are otherwise “underserved” (Wilkinson and Weitkamp, 2016).

Over the 22-day trek, clips were filmed and edited daily on an iPhone 7-Plus into a 5–7-min video blog (vlog), using iPhone's pre-installed iMovie software. Short vlogs have been shown to provide influential digital interaction, contributing to cultural citizenship (Ruedlinger, 2012; Papadima-Sophocleous et al., 2016). Vlogs were a mixture of landscape and wildlife “cutaway” shots, presenter-led sections and spontaneous wildlife encounters. These were uploaded the same day onto YouTube and shared via dedicated social media accounts to be followed online in near real-time, enabling rapid engagement (Lessard et al., 2017).

Two months prior to Sophie's Wild Cornwall, information on the trek was disseminated via frequent online posts. The Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Surfers Against Sewage, The Wildlife Trusts, Ordnance Survey, BBC Countryfile Magazine and the university at which the work was based, also shared the trek via their social media accounts, before, during, and after the event.

Engagement trends were measured 1 week before, during the 3 weeks of the trek and 1 week after using analytical tools available on the social media platforms, offering insights into the online landscape of public engagement (Fan and Gordon, 2014), including audience demographics, length of engagement and the types of content eliciting the most response.

An online survey consisted of questions determining user demographic data, including education level and whether the respondent had a science background, as well as motivations for following and engagement outcomes. The survey was shared 1 week after completion of the trek across the same social media channels, as well as distribution across mailing lists consisting of science communication professionals, academics and members of scientific organizations. All participants remained anonymous and under 18 s were excluded. The survey followed the ethical procedures for Postgraduate Taught Masters projects at UWE, Bristol, including written consent to participate.

Results

Sophie's Wild Cornwall Analytics

Over the 5-week period, total engagement increased across all platforms. Total followers increased by 75% on Facebook to ~400 individuals, while Twitter saw a ~300% rise, and YouTube subscriptions rose by > 1,000%. Instagram experienced the greatest overall following, growing 3-fold to 1,000 individuals over the duration of the project. Most users were 18–24 years old, with YouTube attracting a slightly older audience (Table 1). Each platform hosted near-equal male: female participation, however Facebook entertained a noticeable female majority.

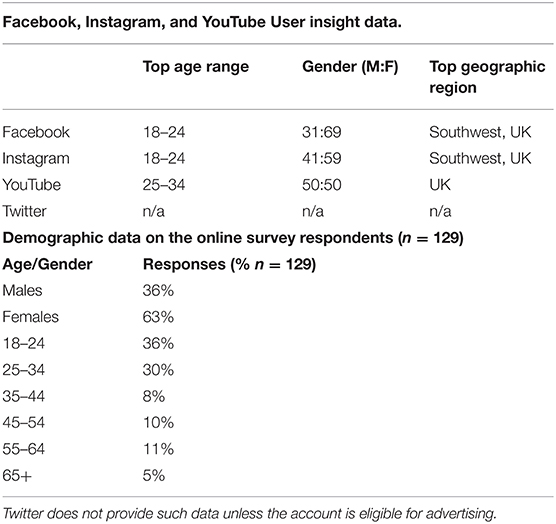

Table 1. Key user insight data generated from imbedded social media analytic tools and online survey respondents.

Nearly all participants were from the south of the UK, suggesting an element of relatability as the area was familiar or nearby. Despite a strong “local” reach, posts also experienced interaction from followers in Russia, the USA, Australia and Europe.

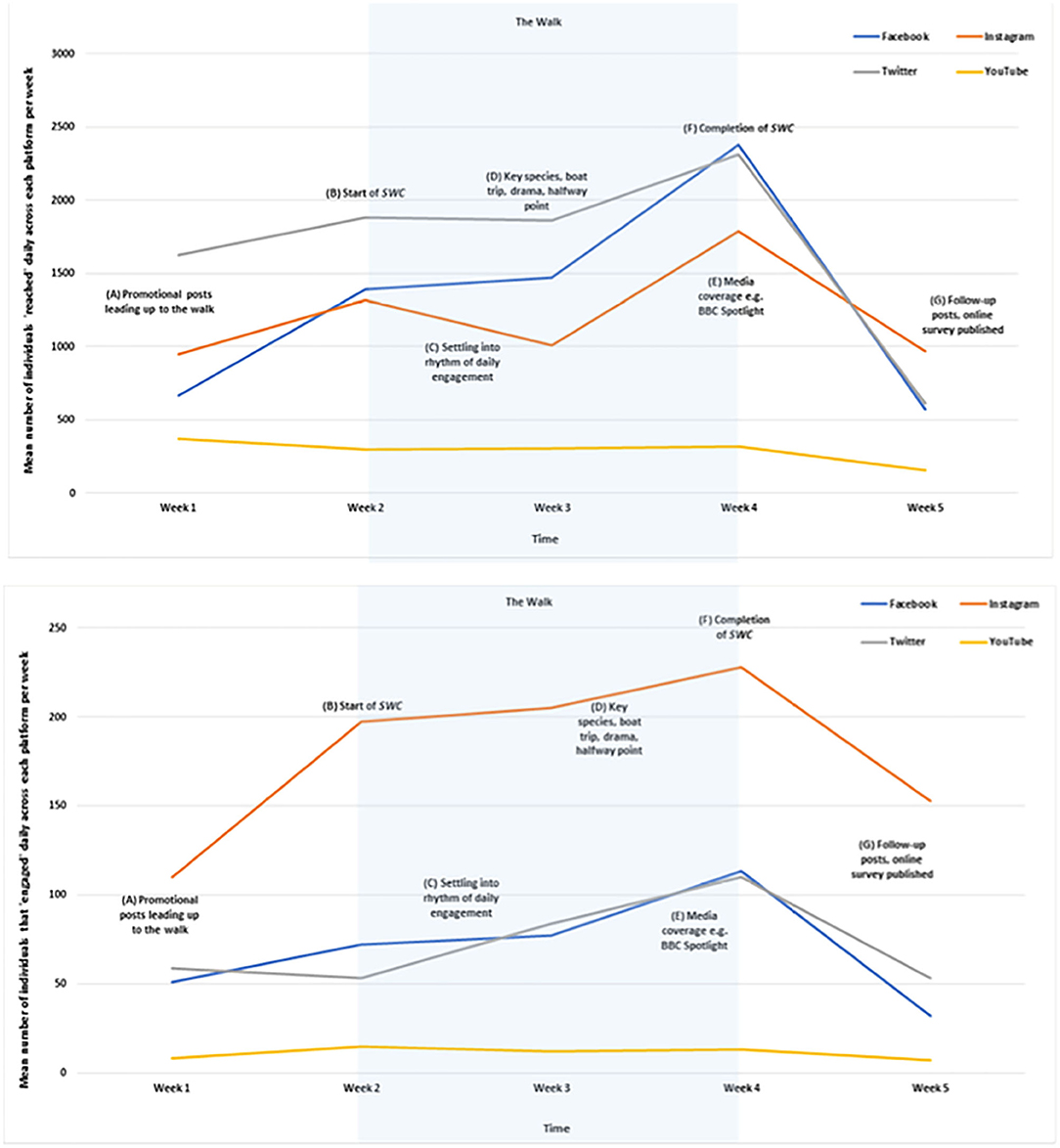

A closer examination of user interaction with the posts determined overall “reach” and active “engagement” across each platform (Figure 1). “Reach,” quantifies the number of individual accounts that “see” a post and “engagement” measures, “social involvement,” the number of times a post was liked, saved or commented on. Twitter only offers data on social media “impressions” vs. “reach,” quantifying the times people saw a particular “tweet,” instead of how many individual accounts saw it.

Figure 1. The mean number of individuals “reached” and “engaged” across each social media platform used during Sophie's Wild Cornwall throughout the 5-week measurement period. Labels indicate key chronological events during the walk that likely influenced noticeable changes in audience reach and overall engagement trend.

Figure 1 illustrates increased reach over time across each platform. Each post reached an average of 1,000 individuals per day. Facebook experienced the greatest growth, similarly, Instagram grew by 89%, yet maintained a more stable reach. Despite being unable to quantify “reach” on Twitter, the overall trend quantifying Twitter “impressions” matches that of the other platforms. YouTube had the lowest overall activity, experiencing a small decrease in reach across the 5 weeks, despite a 63% relative growth in audience engagement between week 1 and 4.

Fluctuations with engagement and reach appeared to coincide with key events. For example, the prelude to Sophie's Wild Cornwall involved external support and “sharing” with an average ~74% increase in reach between Facebook and Instagram during week 1. Two relevant online videos at the outset, explaining the purpose of the initiative, may explain the estimated 88% relative growth in YouTube engagement given the suitability of such content for that platform.

Reaching the “halfway” point of the trek promoted an increase in reach and engagement across all platforms. The most popular posts and online videos were those that presented breadth of content, such as multiple encounters with wildlife, depth of scientific information or striking landscapes. All platforms bar YouTube, exhibited a growth in reach and engagement during such moments, especially Facebook and Instagram. Similarly, moments captured in online videos such as physical injury or emotive scenes, contributed to increased follower interaction. This was especially noticed toward the end of the initiative and the trek's successful completion, where all channels except YouTube, experienced a peak in both audience reach and engagement.

Public Opinion Survey

Table 1 illustrates that there were a higher proportion of female: male respondents among a largely young audience. Academic qualifications offered insight into potential incentives for following, 43% (n = 55) selected a university undergraduate degree as their highest academic qualification, followed by a postgraduate degree (34%). Whilst half had studied a science or environmental area at university (50%), the remaining respondents had received no scientific/environmental degree training. Fifty two percentage of people had not previously worked in a science or environmental area.

Respondents stated engaging in a similar use of Facebook (26%), Twitter (18%), Instagram (22%) and YouTube (19%) (n = 27), supporting the decision to use a combination of these platforms to share the online videos. Eighty three percentage of (n = 107) of participants cited a smartphone as the preferred device for access. When asked about engagement with STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) content online, “environment and nature” had the highest level of daily engagement (43%, n = 55) compared to “health and medicine” (19%) and “technology and engineering” (27%).

Nearly 90% (n = 116) of respondents used Facebook, Instagram and YouTube to follow, leaving under 10% of people using Twitter alone. A range of motives, were selected, in regard to why they followed. “Information” and “entertainment” comprised around 75% (n = 97) of responses. Other motivations included social engagement, interest in Cornwall and the overall project. To determine success as a science communication initiative, respondents were asked what they “gained” from following. “New information,” “entertainment,” “on the go” science communication and “an appreciation of local nature” comprised 94% (n = 121) of responses. Vlogs, online videos produced during Sophie's Wild Cornwall were the most popular medium with which users could engage; 86% (n = 111) of respondents liked them “a lot.” Photographs with an informative caption also proved popular (72%, n = 93 liking them “a lot”).

Open comments provided a number of additional motivations for following online, including that it's “easier to access the content you want” (User E), to follow/unfollow your interests, the accessible nature, checking throughout the day, as part of daily routines, “anytime, anywhere” (User H). The ability to follow events in near real-time also seems to make content, “more relevant” (User J). The use of presenter-led vlogs was very popular, with users developing “a kind of relationship with the presenter” (User O), learning along with them, and liking the ability to interact.

Users could, “speak directly to the presenter” and appreciated this both in making the content “feel more personal and approachable” (User T).

Discussion

There are inherent elements of subjectivity in the interpretation of this case study, however it presents insight into how an audience engaged with one science communication endeavor using online videos via digital platforms. However, the role of the authors in the intervention must be acknowledged and this may have influenced the interpretation of some findings. In examining the results, the “AEIOU” criteria (Burns et al., 2003) were used as a means of considering whether online video use via social media, can be used for public engagement.

Online videos, shared via social media, can be used as a modern, “gateway” raising awareness of a scientific topic to motivate a users' curiosity and potential behavioral change (Burns et al., 2003; Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Corner and Randall, 2011; Liang et al., 2014; Allgaier, 2019). Awareness is difficult to quantify especially on social media (Hanna et al., 2011), however the physical growth in both “reach” and active “engagement” across each platform indicated a likely growing consciousness of the expedition and environmental content. External support from organizations and media groups, raised awareness of the project, amplifying Sophie's Wild Cornwall organically.

The integration of online “sharing” tools to promote the online videos, introduced the initiative to a broader audience. Facebook, Twitter and Instagram epitomize “interactive media” through which users can comment, share, tag friends or “like” a post (Hanna et al., 2011). In contrast, YouTube is limited to video content (Zuckerberg et al., 2012), meaning subscribers to Sophie's Wild Cornwall only received one notification per day. This minimized the opportunity for non-subscribers to become aware of the initiative, supporting research detailing YouTube's low “posting” rates (Moran et al., 2011) and inadequacy as a tool to spread “awareness” (Steinberg et al., 2010). It also supports the growing popularity of Instagram especially among young people (Groffman et al., 2010). Young adults are adept at navigating digital spaces (Lee and Ma, 2012; Ofcom, 2015) and therefore using social media in crafting impactful content, appears a beneficial way, to mobilize this cohort to participate in science (Deboer, 2000; Hargittai et al., 2018).

Active engagement during Sophie's Wild Cornwall also indicated user enjoyment, as followers felt sufficiently engaged to maintain involvement. To be “entertained” by social media content was expected by a quarter of survey respondents, and users appeared particularly eager to connect directly with the presenter, supporting the value of “presenter-led” real-time engagement (Young et al., 2017). The physically demanding nature of the trek produced “emotion” and “drama,” as users admitted that the, “informal but informative” mode of delivery contributed to a participatory experience, building upon previous research suggesting establishing an emotional connection with an audience improves relatability and directly affects the duration of engagement (Durkin et al., 2012; Jarreau and Yammine, 2017; Lessard et al., 2017).

The increasing acceptance of social media as a source of information (Brossard, 2013; Liang et al., 2014; Fletcher, 2017) provides opportunities to integrate science communication, including in the form of online videos (Davies et al., 2020), in daily lives. Seeking “new information” was a primary motivator and engagement outcome from following Sophie's Wild Cornwall and social media offered opportunities to reach more diverse audiences, with only 50% of respondents holding an environmental or science-related degree. Embedded algorithms tailor content to reflect users' interests (Zuckerberg et al., 2012) a barrier to reaching new audiences. This re-iterates the immense power of “social sharing,” offering the potential to spread content beyond a user's network (Hanna et al., 2011; Huber et al., 2019). As half of respondents had no previous involvement in a science or environmental area, social media can succeed in stimulating interest in topics that a user, “might not usually think about” (User N). Engagement with the trek also contrasted some previous studies which found that online science users tend to be tend to be “more knowledgeable about science, more educated, and primarily male” (Brossard, 2013, p. 14097).

Opinions are complex, subjective and difficult to measure. A person's current knowledge, beliefs and personality can influence opinions (Burns et al., 2003) and even predict future behavior (Kelman, 1961). Successful science communication can occur when a participant reflects upon new ideas, to inform or review previously held opinions (Burns et al., 2003; Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Corner and Randall, 2011). Social networks can therefore “guide opinion” (Susarla et al., 2011) and followers of Sophie's Wild Cornwall and survey respondents commented on the rich learning experience provided by being able to view responses from the presenter and collaborate with other users.

Achieving understanding following a science communication endeavor arguably remains the “end-goal” for many and a, “prerequisite for higher levels of scientific literacy” (Burns et al., 2003, p. 198). The transferability of the vlogs into classrooms, which was reported in some comments and survey responses, demonstrates their suitability for learning in a similar way to sites such as YouTube as teaching aides (Tess, 2013). Online videos, shared via social media may offer a modern solution to upstream engagement, by presenting science content in an appealing, digestible format that users can “understand” (Lovejoy et al., 2012; Duggan, 2015; Garcia-Aviles and de Lara, 2018) while it is in process.

Via a 300-mile trek around Cornwall, this case study has highlighted implications for the use of social media, and online videos, in science communication and engagement, including on social media platforms beyond YouTube. The global audience, but also local audience, were motivated by the visual, concise and interactive features of social media. Nearly all survey respondents indicated that they would like to engage with science in this way again and the vlogs were particularly effective at sharing the adventure with a young audience. Effective social media and online video use then requires a balance between crafting an informative yet entertaining narrative without compromising scientific accuracy; yet ultimately, these platforms may represent a pertinent and exciting “stepping-stone” for practitioners to consider implementing in a journey toward “upstream engagement.”

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the (SP and CW) acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content (SP and CW), final approval of the version to be published (SP and CW), agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that (SP and CW), and questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all those who participated in following the trek and the online survey for generously contributing their time to this research. Thanks to The Wildlife Trusts, Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Surfers Against Sewage, UWE Bristol, and BBC Countryfile Magazine for promoting Sophie's Wild Cornwall.

References

Aldred, J. (2016). Woman Sets Out to Paddleboard Length of England to Highlight Plastic Pollution. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/may/11/woman-sets-out-to-paddleboard-length-of-england-to-highlight-plastic-pollution. (accessed March 18, 2017).

Allgaier, J. (2019). Science and environmental communication on youtube: strategically distorted communications in online videos on climate change and climate engineering. Front. Commun. 4:36. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00036

Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., and Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 1, 287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006

Ballard, H. L., Robinson, L. D., Young, A. N., Pauly, G. B., Higgins, L. M., Johnson, R. F., et al. (2017). Contributions to conservation outcomes by natural history museum-led citizen science: examining evidence and next steps. Biol. Conserv. 1, 87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.08.040

Bernhardt, J. M., Mays, D., and Kreuter, M. W. (2011) Dissemination 2.0: closing the gap between knowledge practice with new media marketing. J. Health Commun. 16, 32–44. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.593608

Brossard, D. (2013) New media landscapes and the science information consumer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 14096–14101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212744110.

Burns, T. W., O'Connor, D. J., and Stocklmayer, S. M. (2003) Science communication: a contemporary definition. Public Understand. Sci. 12, 183–202. doi: 10.1177/09636625030122004

Centola, D. (2010) The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science 329, 1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.1185231.

Collins, K., Tapp, A., and Pressley, A. (2010) Social marketing social influences: Using social ecology as a theoretical framework. J. Market. Manage. 26, 1181–1200. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2010.522529

Corner, A., and Randall, A. (2011) Selling climate change? The limitations of social marketing as a strategy for climate change public engagement. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.05.002

Cornwall Wildlife Trust (2017). Find a Nature Reserve. Cornwall Wildlife Trust. Available online at: http://www.cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk/wildlife/reserves (accessed September 19, 2017).

Davies, S. R., and Hara, N. (2017) Public science in a wired world: how online media are shaping science communication. Sci. Commun. 39, 563–568. doi: 10.1177/1075547017736892

Davies, L., León, B., and Bourk, M. (2020). Transformation of the media landscape: Infotainment versus expository narrations for communicating science in online videos. Public Underst. Sci. 963662520945136. doi: 10.1177/0963662520945136. [Epub ahead of print].

Deboer, G. E. (2000) Scientific literacy: another look at its historical and contemporary meanings and its relationship to science education reform. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 37, 582–601. doi: 10.1002/1098-2736(200008)37:6<582::AID-TEA5>3.0.CO.

Duggan, M. (2015). Mobile Messaging and Social Media 2015. Pew Research Center. Available online at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/19/mobile-messaging-and-social-media-2015-main-findings/ (accessed September 14, 2017).

Durkin, M., McKenna, S., and Cummins, D. (2012) Emotional connections in higher education marketing. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 26, 153–161. doi: 10.1108/09513541211201960

Facebook. (2018). Company Info. Available online at: https://newsroom.fb.com/company-info/ (accessed March 2, 2018).

Fan, W., and Gordon, M. D. (2014). The power of social media analytics. Commun. ACM 57, 74–81. doi: 10.1145/2602574

Fletcher, R. (2017) Connection with nature is an oxymoron: a political ecology of “nature-deficit disorder”. J. Environ. Educ. 48, 226–233. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2016.1139534.

Garcia-Aviles, J. A., and de Lara, A. (2018). “overview of science online videos: designing a classification of formats,” in Communicating Science and Technology Through Online Video, eds B. León and M. Bourk (London: Routledge) 15–27. doi: 10.4324/9781351054584-2

Groffman, P. M., Stylinski, C., Nisbet, M. C., Duarte, C. M., Jordan, R., Burgin, A., et al. (2010). Restarting the conversation: challenges at the interface between ecology and society. Front. Ecol. Environ. 8, 284–291. doi: 10.1890/090160

Hacker, R. G., and Harris, M. (1992). Adult learning of science for scientific literacy: some theoretical and methodological perspectives. Stud. Educ. Adults 24, 217–224. doi: 10.1080/02660830.1992.11730574

Hanna, R., Rohm, A., and Crittenden, V. L. (2011). We're all connected: The power of the social media ecosystem. Bus. Horiz. 54, 265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.007

Hargittai, E., Füchslin, T., and Schäfer, M. S. (2018). How do young adults engage with science and research on social media? Some preliminary findings and agenda for future research. Soc. Media Soc. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/2056305118797720

Holliman, R., Whitelegg, E., Scanlon, E., Smidt, S., and Thomas, J. (2009). Investigating Science Communication in the Information Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Howell, E. L., Nepper, J., Brossard, D., Xenos, M. A., and Scheufele, D. A. (2019) Engagement present future: graduate student faculty perceptions of social media the role of the public in science engagement. PLoS ONE 14:e0216274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216274

Huber, B., Barndige, M., and Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2019). Fostering public trust in science: the role of social media. Public Underst. Sci. 28, 759–777. doi: 10.1177/0963662519869097

IPSOS Mori (2014). Public Attitudes to Science 2014. Available online at: https://www.britishscienceassociation.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF276d302a-5fe8-4fc9-a9a3-26abfab35222 (accessed March 2, 2018).

Jarreau, P., and Yammine, S. (2017). Scientist Selfies – Instagramming to Change Public Perceptions of Scientists. LSE Impact Blog. Available online at: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2017/08/21/scientist-selfies-instagramming-to-change-public-perceptions-of-scientists/ (accessed September 14, 2017).

Kaplan, A. M., and Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horiz. 53, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Koivumäki, K., and Wilkinson, C. (2020). Exploring the intersections: researchers and communication professionals' perspectives on the organizational role of science communication. J. Commun. Manage. 24, 207–226. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-05-2019-0072

Koohy, H., and Koohy, B. (2014). A lesson from the ice bucket challenge: using social networks to publicize science. Front. Genet. 15:430. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00430

Korda, H., and Itani, Z. (2013) Harnessing social media for health promotion behavior change. Health Promot. Pract. 14, 15–23. doi: 10.1177/1524839911405850

Kuss, D. J., and Griffiths, M. D. (2011) Online social networking addiction—a review of the psychological literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8, 3528–3552. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8093528

Lee, C. S., and Ma, L. (2012) News sharing in social media: the effect of gratifications prior experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28, 331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.002

León, B., and Bourk, M. (2018). “Investigating science-related online video,” in Communicating Science and Technology Through Online Video, eds B. León and M. Bourk (London: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781351054584

Lessard, B. D., Whiffin, A. L., and Wild, A. L. (2017) A guide to public engagement for entomological collections natural history museums in the age of social media. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 110, 467–479. doi: 10.1093/aesa/sax058

Liang, X., Leona, Y. S., Yeo, S. K., Scheufele, D. A., Brossard, D., Xenos, M., et al. (2014). Building buzz: (Scientists) communicating science in new media environments. J. Mass Commun. Q. 91, 772–791. doi: 10.1177/1077699014550092

Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S., and Whitmarsh, L. (2007) Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Change 17, 445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.01.004

Lovejoy, K., Waters, R. D., and Saxton, G. D. (2012) Engaging stakeholders through Twitter: How nonprofit organizations are getting more out of 140 characters or less. Public Relat. Rev. 38, 313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.01.005

Mangold, W. G., and Faulds, D. J. (2009) Social media: the new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 52, 357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.03.002

Marketing Magazin (2017). How Much Time Do People Spend on Social Media? A Lot! Marketing Magazin. Available online at: http://marketingmagazin.eu/2017/01/05/infographic-much-time-people-spend-social-media/ (accessed August 4, 2017).

Metzger, M. J., and Flanagin, A. J. (2011) Using Web 2.0 technologies to enhance evidence-based medical information. J. Health Commun. 16(Suppl. 1), 45–58. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.589881

Miller, B., Conway, W., Reading, R. P., Wemmer, C., Wildt, D., Kleiman, D., et al. (2004). Evaluating the conservation mission of zoos, aquariums, botanical gardens, and natural history museums. Conserv. Biol. 18, 86–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00181.x

Moran, M., Seaman, J., and Tinti-Kane, H. (2011) Teaching, Learning, and Sharing: How Today's Higher Education Faculty Use Social Media. Wellesley, MA: Babson Survey Research Group.

Ofcom (2015). Children and Parents: Media Use and Attitudes Report. Ofcom. Available online at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/_data/assets/pdf_file/0024/78513/childrens_parents_nov2015.pdf (accessed November 1, 2017).

Papadima-Sophocleous, S., Bradley, L., and Thouësny, S. (2016). CALL Communities and Culture–Short Papers From EUROCALL Research-publishing. Limassol. doi: 10.14705/rpnet.2016.EUROCALL2016.9781908416445

Peters, H. P., Brossard, D., de Cheveigné, S., Dunwoody, S., Kallfass, M., and Miller, S. (2008) Interactions with the mass media. Science 321, 204–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1157780

Peters, H. P., Dunwoody, S., Allgaier, J., Lo, Y. Y., and Brossard, D. (2014). Public communication of science 2.0. Is the communication of science via the “new media” online a genuine transformation or old wine in new bottles? MBO Rep. 15, 749–753. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438979

Plastic Patrol (2017). Plastic Patrol. Available online at: http://www.plasticpatrol.co.uk (accessed September 7, 2017).

Ruedlinger, B. (2012). Does Video Length Matter? Wistia.com. Available online at: https://wistia.com/blog/does-length-matter-it-does-for-video-2k12-edition (accessed September 25, 2017).

Schou Andreassen, C., and Pallesen, S. (2014). Social network site addiction-an overview. Curr. Pharm. Design 20, 4053–61. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990616

Simis-Wilkinson, M. J., Madden, H., Lassen, D. S., Su, L. Y. F., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., et al. (2018). Scientists joking on social media: an empirical analysis of #overlyhonestmethods. Sci. Commun. 40, 314–339. doi: 10.1177/1075547018766557

Smallcombe, M. (2017). Cornwall is the Second-Poorest Region in Northern Europe and a Quarter of Children Live in Poverty – so What Are the Problems and What Can Be Done? Cornwall Live. Available online at: http://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/cornwall-second-poorest-region-northern-617199 (accessed November 4, 2017).

Spooner, F., Smith, R. K., and Sutherland, W. J. (2015). Trends, biases and effectiveness in reported conservation interventions. Conserv. Evid. 12, 2–7.

Statista (2018a). Number of Monthly Active Instagram users from January 2013 to September 2017 (in Millions). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/253577/number-of-monthly-active-instagram-users/ (accessed March 2, 2018).

Statista (2018b). Number of Monthly Active Twitter Users Worldwide from 1st quarter 2010 to 4th quarter 2017 (in Millions). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/282087/number-of-monthly-active-twitter-users/ (accessed March 2, 2018).

Steinberg, P. L., Wason, S., Stern, J. M., Deters, L., Kowal, B., and Seigne, J. (2010) YouTube as source of prostate cancer information. Urology 75, 619–22. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.07.059

Susarla, A., Oh, J. H., and Tan, Y. (2011). Social networks and the diffusion of user-generated content: evidence from YouTube. Inform. Syst. Res. 23, 23–41. doi: 10.1287/isre.1100.0339

Tess, P. A. (2013) The role of social media in higher education classes (real and virtual)–a literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, A60–A68. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.032.

Wilkinson, C., and Weitkamp, E. (2013) A case study in serendipity: environmental researchers use of traditional social media for dissemination. PLoS ONE. 8:e84339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084339

Wilkinson, C., and Weitkamp, E. (2016) Creative Research Communication: Theory Practice. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Young, W., Russell, S. V., Robinson, C. A., and Barkemeyer, R. (2017) Can social media be a tool for reducing consumers' food waste? A behaviour change experiment by a UK retailer. Resour. Conserv. Recycle. 117, 195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.10.016

Keywords: online videos, science communication, environmental communication, conservation, upstream engagement

Citation: Pavelle S and Wilkinson C (2020) Into the Digital Wild: Utilizing Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and Facebook for Effective Science and Environmental Communication. Front. Commun. 5:575122. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.575122

Received: 22 June 2020; Accepted: 07 September 2020;

Published: 16 October 2020.

Edited by:

Joachim Allgaier, RWTH Aachen University, GermanyReviewed by:

Brigitte Huber, University of Vienna, AustriaSarah Kohler, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Germany

Copyright © 2020 Pavelle and Wilkinson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Clare Wilkinson, Y2xhcmUud2lsa2luc29uQHV3ZS5hYy51aw==

Sophie Pavelle

Sophie Pavelle Clare Wilkinson

Clare Wilkinson