94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Commun., 23 October 2020

Sec. Media Governance and the Public Sphere

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.557561

This article is part of the Research TopicMedia Populism: How Media Populism and Inflating Fear Empowers Populist PoliticiansView all 5 articles

Populist radical-right parties (PRRPs) were once considered “fringe parties” condemned to permanent opposition. Their electoral success, so it was argued, would be short-lived, especially once in office, when the party would face complex policy challenges and become accused of overpromising. However, PRRPs have now joined coalition governments in many countries, without suffering voter losses. This raises the question of how PRRPs managed to break through this “glass ceiling.” In this conceptual paper we review research seeking to identify a “winning formula.” We argue that in order to make progress we need to avoid unhelpful “either-or” thinking, and capture the interplay between demand-side factors (reasons why voters become attracted to PRRPs) and supply-side factors (the things PRRPs do to increase their electoral appeal). More specifically, we propose a new integrative analytical framework, one that enables us to study the way in which supply- and demand-side factors interact and reinforce each other. We conclude this paper by emphasizing the importance of accounting for the interaction between supply and demand. It is only in this way that we can enhance our capacity to account for the powerful ways in which PRRP leaders persuade voters that they alone can solve society's most pressing problems.

Populist Radical Right Parties1 (PRRPs) made a remarkable comeback in Western Europe in the mid-1980s. Many of these parties managed to “shake off” their old thuggish far-right image, and became regarded as a more acceptable alternative to mainstream parties. Once rebranded, parties like France's Rassemblement National, previously known as Front National (FN), began to attract a larger share of the vote in local and national elections. However, the gains typically fell short to warrant a place in (coalition) government, and commentators could thus continue to describe these parties as “too radical” and therefore “destined to permanent opposition.”

All this changed more recently, when PRRPs suddenly proved capable of securing significant electoral gains. For example, the Dutch Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) secured a major victory in 2010, securing 24 seats in national parliament with 15.4% of the vote, and becoming the third largest party in the country. Indeed, the party was deemed a serious contender for a place in coalition government. However, the Christian Democrats (CDA) refused to grant PVV cabinet membership, and the party ended up supporting the newly formed government via a “confidence and supply” pact, thereby remaining in spirit in opposition. Likewise, in 2015, Denmark's Dansk Folkeparti (DP) won 37 of the 179 seats in national parliament, securing 21.1% of votes, and becoming the second-largest party in the country. Like the PVV, DP ended up agreeing to a confidence and supply pact instead of a place in government. In fact it was the fourth time DP entered into a confidence and supply agreement (2001, 2005, 2007, 2015), and although the party lost significant ground in the 2019 national elections, the party is one of many examples of PRRPs securing significant electoral gains in recent years.

Even clearer examples of PRRPs securing major electoral gains are Hungary's Fidesz, which won 49.3% of votes in the 2018 elections, and Poland's Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PIS), which secured 43.6% in the 2019 elections. A further case in point is Marine Le Pen's strong showing in France's 2017 Presidential elections. Le Pen secured 21.3% of the vote in the first round, and 33.9% in the second round as leader of Front National, the forerunner of today's Rassemblement National (RN). Once we consider the steady rise of populist parties with a nativist anti-immigration agenda, and the current level of support these parties enjoy in many Western countries, it is hardly surprising that many mainstream right-wing parties have begun to adopt a more nativist rhetoric and policy stance, in the hope of retaining voters who might otherwise switch to more radical populist alternatives (Meguid, 2008; see also Wagner and Meyer, 2017; Abou-Chadi and Krause, 2020). As Wear (2008) has shown, this pattern was witnessed in Australia, where the Liberal Party of Australia (LPA) took over many of the themes first popularized by Pauline Hanson's more radical One Nation party.

Australia is not the only country to have witnessed the mainstreaming of nativist narratives. A similar process occurred in the UK in the lead-up to the 2016 Brexit referendum, when the Conservative-backed “Leave” campaign resorted to scare tactics to instill fear of immigration, thus framing the referendum effectively as a vote on immigration. Although campaign “Remain” and campaign “Leave” both used scare tactics to persuade voters (Schmidt, 2017), it was “fear for immigration” that decided the result (Goodwin and Milazzo, 2017). Likewise, in the U.S., it was Donald Trump who, during his successful bid for the U.S. presidency, showed the world that nativism and anti-establishment rhetoric continue to have electoral appeal.

As researchers have shown, not all right-wing mainstream parties fall victim to nativist “contagion” (Rooduijn et al., 2014; van Spanje, 2018). However, in our view there are nonetheless some preliminary conclusions that can be drawn from these cases, namely: (a) that PRRPs have gained significant ground in many countries that were once regarded stable democracies, (b) that right-wing mainstream parties often (though not always) react to the rise of PRRPs by adopting a similar stance, and (c) that, if left unchallenged, this can lead to a gradual shift to the right in all mainstream parties' stance on immigration, multiculturalism and international cooperation.

When PRRPs rise in popularity, more mainstream right-wing parties typically respond by hardening their own stance on issues like immigration and multiculturalism (Williams, 2006; Meguid, 2008; Wagner and Meyer, 2017; Abou-Chadi, 2018). However, this convergence strategy does not necessarily diminish the appeal of radical-right movements and anti-immigration parties. For instance, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) increased its share of the overall vote in general elections significantly (from 3.1% in 2010 to 12.6% in 2015), this despite Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron aligning his party with UKIP in 2013, by promising an in-out referendum after renegotiating the UK's relationship with the EU. It thus seems far from guaranteed that this convergence strategy will have its intended effect and reduce the electoral appeal of PRRPs.

There is another process that does not seem to hinder the success of PRRPs, which is PRRPs tendency to overpromise (Papadopoulos, 2000). While overpromising may help newly established PRRPs in opposition, as it will help to attract media attention and increase the party's popularity among disgruntled voters keen to cast a protest vote, one would expect the strategy to no longer work once in office, when the party is expected to help find policy solutions that will work, and can be implemented. The idea of “success in opposition, failure in government” makes perfect logical sense, and it underpinned the so-called “inclusion-moderation thesis” (Heinisch, 2003). However, here too there is mounting evidence to the contrary, with research showing PRRPs remain popular and do not soften their stance once in office (Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2015; see also Akkerman et al., 2016). Indeed, as several authors have noted, it is PRRPs' willingness to resort to radical scare tactics that gives these parties a competitive advantage and considerable control over their own popularity and electoral destiny (Ignazi, 2003; Carter, 2005; Goodwin, 2006). Why then does a convergence strategy by mainstream parties not take the wind out of the sails of PRRPs? And why are PRRPs that suddenly find themselves in power not “pulled up” on not delivering on their ambitious promises?

The existing literature provides partial answers to such questions. For example, researchers found that PRRPs radicalize further when mainstream parties align themselves (Wagner and Meyer, 2017). Such studies serve as a useful reminder that PRRPs simultaneously “read” and “shape” public sentiments (by repositioning the party vis-à-vis competitor parties, and by adopting counter narratives), and that PRRP support is more dynamic and context-dependent than often assumed. Research to date has tended to focus on disentangling factors mediating PRRP support in relation to either demand-side (i.e., why the public is attracted to PRRPs) or supply-side factors (i.e., how PRRP parties and their leaders position themselves to attract votes). While useful, in our view it is time to step up efforts to integrate insights and avoid unhelpful “either-or” thinking, and capture both demand-side and supply-side factors.

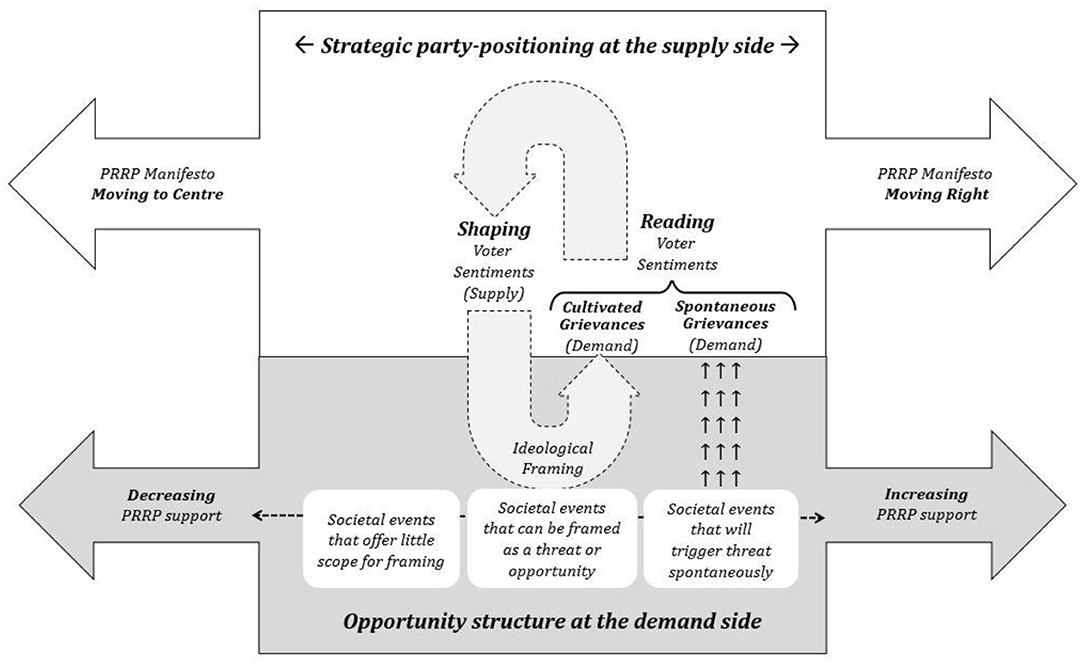

As Golder (2016, p. 477) notes, PRRP researchers “must recognize the interaction between demand-side and supply-side factors in their empirical analyses.” We agree wholeheartedly. However, without a conceptual roadmap, there will remain considerable risk of researchers gradually slipping back into either-or thinking. We propose a new model (“roadmap”) in the hope that this will help to remedy this tendency (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An integrative model of PRRP support: Capturing the interplay between supply (i.e., how PRRPs and their leaders position themselves vis-à-vis the electorate) and demand (i.e., public interest in PRRPs).

In the remainder of this article, we will review existing knowledge of demand-side and supply side research, and consider ways in which the two interact. Before doing so, a few pointers that will help to understand the logic of the below model. As a starting point to the model is the proposition that strategic party positioning at the supply side (top part of Figure 1) involves PRRPs (like mainstream parties) simultaneously “reading” and “shaping” voter sentiment. We then propose that some societal events will trigger fear and/or anger and increase the appeal of PRRPs automatically (e.g., Jihadist terrorist attacks), while other events can be framed as representing an outgroup threat and subsequently increase the appeal of PRRPs (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic). Once we accept that PRRPs can induce demand by framing all kinds of societal issues as outgroup threats or opportunities, and that PRRPs will read the public mood to identify issues that are increasing the appeal of PRRPs automatically and issues that can be framed as a threat or opportunity (and as a reason to vote PRRP), then it becomes clear (a) that there is a feedback loop between “supply” and “demand,” (b) that PRRPs use supply techniques (e.g., ideological framing, alarmist narratives) to induce demand, and (c) that “demand” is therefore best regarded as a mixture of spontaneous and cultivated grievances. What is more, once we accept this feedback loop exists, it becomes clear that we also need to treat PRRP manifestos with caution, and recognize that they are both, attempts to read voter sentiments and attempts to shape the public discourse and voter sentiments.

In sum, there is now a large body of research examining either demand- or supply-side factors, but a problematic shortage in research exploring the link between the two (Golder, 2016). Indeed, most scholars will agree that we should avoid “either-or” thinking, that demand and supply are two sides of the same coin, and that the two sides should be studied in conjunction. However, this is not what happens in actual practice. Before providing specific suggestions with regards to how the interplay between demand- and supply can be studied, it might be good to begin with a more detailed overview of demand-side explanations, so as to appreciate the rather limited explanatory and predictive power of “pure” demand-side explanations to explain PRRP success.

What underpins demand-side research is the (tacit) idea of an automatic, unmediated link between objective living and working conditions (e.g., unemployment level, immigration intake, disposable household income, level of education) and the electoral appeal of PRRPs. As Rydgren (2007, p. 247) points out, the explanations on offer in this line of research are almost all based on the idea that PRRP voting is fuelled by “grievances,” such as declining wages, increased competition for jobs or housing, or fear of cultural dilution due to immigration. Demand-side researchers will typically attribute any changes in PRRP popularity as reflecting changes in objective socio-economic conditions. That is, if those grievances remain unchanged because economic conditions do not improve, and mainstream parties seem unable to turn things around, the electorate will gravitate toward those parties that promise a better future, regardless of whether these parties deliver on those promises or not.

Broadly speaking, demand-side research focuses on voter “grievances,” and the grievances that have so far been identified as providing “fertile soil” for PRRP support are (a) economic deprivation, (b) rising economic inequality, (c) resistance to immigration, (d) cultural anxiety, and (e) cultural backlash. Although demand-side researchers will acknowledge that these explanations are not mutually exclusive, in practice research tends to be motivated by eagerness to identify which of these “competing variables” best explains PRRP voting, i.e., carries most causal weight on PRRP voting.

There appears widespread consensus among lay commentators that economic downturns heighten working-class deprivation, frustration, aggression, eagerness to “lash out” to minorities and immigrants, and likelihood of PRRP voting. Indeed, the catchphrase “losers of globalization in rust-belt states” conveys this logic, and it was used time and again as shorthand by journalists trying to offer a plausible explanation for PRRP election success, for Donald Trump's popularity during the 2016 Presidential election campaign, and for the surprise 2016 UK Brexit “Leave” referendum result.

What is remarkable, though, is that there is in fact relatively little empirical evidence to back up the “losers of globalization” thesis. To be sure, some studies found (partial) evidence for economic anxieties driving PRRP voting (e.g., Niedermayer, 1990; see also Betz, 1994; Jackman and Volpert, 1996). However, there are many more studies that do not find a clear relationship between such indicators and PRRP voting (Lubbers et al., 2002; Mols and Jetten, 2017). Once we consider the entire body of research examining this link, it not only becomes clear that the evidence for the economic anxiety thesis is rather mixed and inconclusive (Mudde, 2007), but also that we have reasons to doubt the more mechanical versions of the economic anxiety thesis (Inglehart and Norris, 2016), according to which there would be an automatic link between socio-economic downturns and surges in PRRP voting.

This raises the question of why, despite so much evidence to the contrary, we remain so wedded to the idea of a link between deteriorating socio-economic conditions and PRRP voting. We suspect this may be due to the rather strong influence of Marxian social theory on social movement studies, manifesting in a preoccupation with those at the bottom of the social ladder and the question of how they will respond to growing economic hardship. Indeed, the same (materialist) logic also underpins how popular textbooks about Nazi Germany explain the rise of Adolf Hitler and the NSDAP party. Here too, we are often presented with popular accounts suggesting it was those at the bottom of the social ladder who supported the NSDAP because they were most affected by the fallout of the Great Depression (e.g., mass-unemployment, hyperinflation) and experienced most economic hardship. Perhaps this widespread belief that it was blue-collar workers in Germany who were most attracted to the NSDAP should not surprise us. After all, Hitler's party was named the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (the National Socialist Workers Party), and it is hence easy to jump to conclusions and to interpret the party's success as evidence of popularity among deprived workers (Geary, 2002).

We may buy into this assumption and hold working class voters responsible for Hitler's rise to power. However, it is clear from analyses of NSDAP voting patterns in 1930s Weimar Germany that this would be the wrong conclusion. In fact, what analyses of voting patterns revealed was that Hitler's NSDAP attracted large proportions of voters in regions with healthy economies (O'Loughlin et al., 1995; Geary, 2002), in wealthy city precincts (Hamilton, 1983), and among middle-class voters (Lipset, 1960; Childers, 1976; Fritz, 1987, p. 394; Madden, 1987). Indeed, what these analyses showed is that the NSDAP was remarkably popular among relatively well-to-do “farmers, shopkeepers and artisans” (Falter, 1981; Fritz, 1987), also referred to as the “petite bourgeoisie” (Kleibürgertum). These findings formed the basis of the “Middle-Class Thesis” (Mittelstand Thesis), with subsequent analyses revealing the NSDAP is best regarded as a classless party, able to attract support from all social strata (Mühlberger, 1980; Childers, 1983; Hamilton, 1983).

It would of course be a stretch to liken the NSDAP, with its outright fascist agenda, with a contemporary PRRP. However, in our view it is nonetheless important to recall the findings of research into NSDAP support, this is because the Nazi experience continues to color the lens through which lay commentators tend to view the rising popularity of PRRPs.

The same idea, or rather myth, of poor working-class voters flocking to radical right wing politicians during economic downturns can also be found in many popular accounts of the recent rise in support for PRRPs, as well as in the way journalists typically describe “the typical” Trump voter or Brexit supporter. Here too we see a clear mismatch between lay understandings of PRRP success and support, and research evidence obtained through systematic analyses. Indeed, as recent “Wealth Paradox” research showed, PRRPs tend to attract disproportionate numbers of well-to-do middle-class voters (Mols and Jetten, 2017). The findings of this research align well with earlier studies into support for PRRPs, which revealed that personal and household income are indeed poor predictors for PRRP voting (Norris, 2005; Mudde, 2007). A similar “jumping to conclusions” pattern could be witnessed in the aftermath of the 2016 UK Brexit referendum, when commentators were quick to attribute the result (a win for “Leave”) to “deprived workers” and “white van drivers” in deprived midlands areas. However, subsequent analyses revealed that support for leaving the European Union (EU) was in actual fact stronger among middle-class voters than working-class voters (Dorling, 2016; Antonucci et al., 2017).

These findings have also been found in empirical studies. Researchers examining xenophobia and outgroup hostility experimentally found that both relative deprivation and relative gratification can enhance outgroup hostility. This effect became known in intergroup relations research as the V-Curve (Grofman and Muller, 1973; Guimond and Dambrun, 2002). This V-Curve effect was replicated in more recent experimental research into support for support of anti-immigration messages, and the findings of this work suggest that PRRPs will be able to attract two kinds of voters simultaneously, namely relatively deprived voters who experience economic hardship and/or anxiety, and relatively gratified voters in more fortunate socio-economic circumstances (Jetten et al., 2015).

Of relevance here too is mounting evidence from different fields of study (e.g., research into charitable giving, pro-social behavior) suggesting that acquiring greater wealth does not automatically translate into more relaxed attitudes, generosity or pro-social behavior. On the contrary, the findings of this research suggest that the privileged tend to become harsher toward the less fortunate (Postmes and Smith, 2009), donate less generously to philanthropic causes (Wiepking and Breeze, 2012), and feel less inclined to comply with social norms and rules (Piff et al., 2012).

There are several studies that can help us shed light on this seemingly paradoxical effect. For example, researchers studying the psychology of wealth have found that the wealthy often experience a fear of falling (Ehrenreich, 2020; Jetten et al., 2020), that they adjust their expectations as they move up the social ladder and start making different wealth comparisons (Frank, 2013), and that they continue to worry about their future wealth (Lloyd and Lloyd, 2004). This ‘fear of falling’ (e.g., Ehrenreich, 2020) has been found to be more pronounced in times when the economy is perceived as a bubble about to burst (Jetten et al., 2017), or when other groups appear to climb the social ladder more rapidly (Jetten et al., 2020).

In sum, while the idea of PRRPs predominantly attracting relatively deprived “losers of globalization in rustbelt areas” may have captivated our collective imagination, there is robust evidence showing that PRRPs are capable of attracting voters experiencing relative deprivation as well as voters experiencing relative gratification (Mols and Jetten, 2017; Jetten, 2019). From that perspective, PRRPS may well have broken through electorally, not because of a growing underclass of relatively deprived voters, or because of a coherent party manifesto that caters for those experiencing economic hardship (Mudde, 2007, p. 119–137), but because of PRRPs' remarkable ability to unite “strange socio-economic bedfellows” (Evans, 2005; Ivarsflaten, 2005; Lefkofridi and Michel, 2014).

A closely related explanation for the recent surge and breakthrough of PRRPs is growing frustration about rising inequality, in particular among voters who were once relatively well-off, and part of the middle-class. According to this explanation, large numbers of once relatively well-to-do, middle-class voters started to slide into poverty and job precariousness in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), when the economy slowed down under the weight of austerity measures, and many stable jobs disappeared as a result of automation and the rise of the “gig-economy” (Antonucci et al., 2017; Kurer and Palier, 2019). This view gained ground as evidence began to emerge of rapidly increasing wealth and income inequality in many Western countries, including in countries where governments introduced far-reaching austerity measures (Cingano, 2014). It is hence hardly surprising if many middle-class voters may have felt they had become the victim of a rigged economic system, one that granted tax breaks to the super-rich whilst imposing austerity measures on ordinary hard-working, middle-class citizens (OECD, 2019, p. 28).

There is some evidence that economic inequality is associated with voting for leaders who promise to fix a country's problems, even if the leader in question proposes to resort to undemocratic means to do so. For instance, in a study among 28 countries Sprong et al. (2019) found that higher economic inequality (as indexed by the Gini coefficient) enhanced the wish for a strong leader. Furthermore, this research provided evidence that societal inequality enhances the perception that society is breaking down, and that a strong leader is needed to restore order (even when this leader is willing to challenge democratic values). Even though the link between inequality and attraction to a populist radical right leader was significant in this study, it was also clear that the effect size of this relationship was rather modest, suggesting that economic inequality is just one of the factors that might drive support for PRRPs.

A third demand-side factor to be considered when trying to explain the electoral breakthrough of PRRPs is anxiety over recent surges in immigration and asylum-seeker arrivals. For example, the Syrian refugee crisis seems to have heightened anxiety over the number of new arrivals from non-Western countries in European countries like Hungary, Austria, and Germany, leaving mainstream governing parties with the difficult task of having to allay fears and to find practical solutions. Likewise, in the U.S., refugee arrivals were on the increase from 2011 onwards, and peaked in 2017 with ~85,000 arrivals being recorded that year (Blizzard and Batalova, 2019), and this may well explain why Donald Trump's nativist “America First” campaign message resonated with many voters.

Once again, the idea that peaks in immigration and asylum-seeking increase grievances makes sense. After all, peaks in immigration/asylum-seeking not only increase competition for scarce resources (so-called realistic conflict threat), but also fears that the host community's culture and identity might become overshadowed (so-called symbolic threat). There is also good evidence showing that PRRPs attract voters who favor stricter immigration policy, and whose vote for a PRRP reflects rational/pragmatic policy preferences rather than ideology (Van der Brug et al., 2000). The problem, though, is that concern about immigration (and ensuing PRRP voting) often peaks in times in which the levels of immigration and asylum-seeking is not a cause for concern. Conversely, concern about immigration (and corresponding PRRP voting) has been found to subside in times in which immigration and asylum-seeking are an actual challenge for policymakers (Mols and Jetten, 2017). The broader lesson to emerge from research is that PRRP successes and failures cannot simply be attributed to levels of immigration or asylum-seeking.

One final demand-side analysis focuses on the extent to which voters feel attracted toward PRRPs because they feel that these parties are understanding of the cultural alienation they have experienced over time. According to the cultural backlash thesis, those with little education in particular have not been socialized into adopting changing ideas about society and they feel left out and left behind culturally. As Norris and Inglehart (2019) show in their recent book “Cultural Backlash,” in many Western countries a new intergenerational fault line has emerged. It is one involving a rift between younger, better-educated, progressive populations (concentrated in urban centers) who support progressive causes (e.g., gender equality, action on climate change, refugee protection), and older, less well-educated, conservative populations living in regional cities and rural areas who resist such causes and gravitate toward PRRPs (or mainstream party leaders using populist rhetoric) because they feel excluded culturally.

Inglehart and Norris (2016) tested support for the cultural backlash hypothesis and found in their analysis of different surveys (e.g., European Social Survey) strongest support for PRRPs among the older generation, men, those lacking college education, and people with traditional values. This confirms that the rise of PRRPs reflects to some extent a reaction against a wide range of rapid cultural changes that seem to be eroding the basic values and customs of Western society (Inglehart and Norris, 2016).

It is important to note that opposition to immigration can be fuelled by economic anxieties (and perceived realistic conflict threat) or by cultural anxiety (and perceived symbolic threat) and that the two tend to interact (Golder, 2016; Gidron and Hall, 2017; Halikiopoulou and Vlandas, 2020). It is hence not all that useful to treat economic anxiety and cultural anxiety in a binary “either-or” way, as alternative explanations, and more useful to consider the many additional dimensions already identified in the literature. For example, as Golder (2016) points out, there is a temporal dimension (e.g., stages in PRRP success, current vs. anticipated grievances), a geographical dimension (e.g., center-periphery tension) a self-categorization dimension (e.g., egoistic vs. socio-tropic concerns). Once we appreciate that, we can begin to see that PRRP support is more dynamic and multifaceted than typically assumed, and, more importantly here, that voters can be attracted to PRRPs for a combination of different reasons.

Nevertheless, despite evidence that economic conditions, economic inequality, immigration levels, cultural anxiety, and cultural backlash all matter when it comes to understanding support for PRRPs, it is also clear that such demand-side factors can only provide a partial account of the rise in popularity of PRRPs in many Western countries. Moreover, it becomes clear from this review that the popularity of PRRPs cannot be attributed in a mechanistic way to objective social and/or macro-economic trends. At times, relationships between support for PRRPs and macro-economic trends are more complex, non-linear, or absent altogether.

Indeed, if there were a direct/automatic link between “objective trends and events” and “voter preferences” then it would seem feasible to develop sophisticated statistical models to predict election results with great precision. After all, the challenge would then merely be to improve our modeling of the way in which societal developments impact different groups of voters. However, it is clear from the contrast between the large volume of studies that try to do exactly that, and the many surprise election result in recent years, that we are no closer to predicting election results now than, say, a decade ago.

Therefore, rather than continue searching for an automatic link between objective social and/or macro-economic trends and PRRP voting (focusing on who votes when for PRRPs), it makes more sense to broaden our analyses and to also examine the supply-side factors. What do PRRPs and their leaders do to make their party look like the solution to grievances? We will explore these supply-side factors in greater detail in the next section, and link them to our proposed model to help us integrate the findings of demand- and supply-side research.

Supply-side researchers focus their attention on strategies used by PRRPs to actively increase their electoral appeal (e.g., strategic party positioning, party organization, leadership style, media messaging). As we will discuss in more detail below, a large proportion of supply-side research studies strategic party positioning using party manifestos, and is geared toward identifying PRRPs' “winning formula.” Supply-side researchers will typically agree in principle that suboptimal socio-economic conditions will provide “fertile soil” for PRRPs, but treat this as a background condition, and focus instead on the way in which PRRPs position themselves vis-à-vis other parties seeking to capitalize on dissatisfaction about worsening socio-economic conditions. Some supply-side research goes a step further and focuses on the ability of PRRP leaders to shape the way in which voters interpret socio-economic events and trends. However, such interpretative supply-side studies are few and far between, and form a minority within the much larger body of supply-side research studying strategic party positioning using party manifestos. From this supply point of view, PRRPs' success can be explained by creative reframing of the economic context whereby the message of the PRRP is salient and in the public eye, precisely because they do not shy away from overpromising and are not held back by such reality constraints as more mainstream parties are.

Above we explored what can be described as “pure demand-side” explanations, namely explanations that view “voter preferences” as shaped by political and socio-economic developments “out there” in society. We also considered the kinds of psychological effects these developments may have on voter preferences, thereby focusing on different kinds of grievances, and conceiving these grievances as the spontaneous (rather than induced or cultivated) reactions to these developments. However, what should not be forgotten is a second strand of PRRP supply-side research, which focuses on the things PRRPs actively do to influence voter perceptions.

Supply-side PRRP researchers not only examine what PRRPs and PRRP leaders do to influence voter perceptions, but also whether such attempts have an effect on voter preferences. However, it is of course easier to document what PRRPs do to influence voter preferences, than to ascertain the effect such efforts have on voter preferences, and this is because voter preferences are subject to all kinds of pressures, not just party positioning and party messaging. Nonetheless, thanks to a growing body of supply-side research, we now have considerable knowledge about the ways in which PRRPs seek to enhance their electoral appeal.

Supply-side research can be subdivided into two sub-strands. The first, which appears most well-known, is research into strategic party positioning. As scholars working in this tradition have shown, PRRPs will scan the horizon for “vacant electoral space” and position themselves strategically vis-à-vis competitors (using their party manifesto). A second strand of supply-side research goes a step further and argues that PRRPs and their leaders use creative narratives to create “new electoral space.” According to this more radical second strand, radical right leaders have a remarkable capacity to turn relatively mundane policy issues into perceived existential threats (Mols, 2012; Hogan and Haltinner, 2015; Moffitt, 2015; Cramer, 2016; Stoica, 2017; Wodak, 2017, 2019; Hochschild, 2018).

In our view, both supply-side strands have merit. After all, PRRPs will indeed have to position themselves vis-à-vis competitors and make strategic decisions in the process, and it is at the same time clear that PRRPs will not hesitate to create or perpetuate fake news and conspiracy theories if they feel this might benefit them electorally. Leaders have an important role to play in this process. Nonetheless, what is lacking in this research is acknowledgment that (as shown in Figure 1) supply affects demand, but that demand also further influences supply, as PRRPs will play into existing fears by framing issues as outgroup threats. Before elaborating that point, we will discuss the various supply-side perspectives in more detail.

Like their more mainstream counterparts, PRRPs will try their best to position themselves strategically vis-à-vis competitors and adopt a manifesto that will offer the party the best chance to win over voters (Akkerman et al., 2016). As Downs (1957) showed in his seminal work on the “Median Voter Theorem” (MVT), in majoritarian systems, mainstream left- and right-wing parties will be inclined to move to the center in the lead up to elections, as this increases their chances of securing a winning majority. This will in turn create vacant space at the radical (left- and right-) fringes, which PRRPs will be able to fill (Figueira, 2018).

This reasoning fits well with one of the more commonly heard explanations for the recent surge and breakthrough of PRRPs. Here, the reasoning is that PRRPs have been able to fill the “vacant elector space” that started to open up in the 1980s, when many left-wing parties started to move to the center and embrace a more centrist “third-way” socio-economic stance. This, so the argument typically goes, enabled PRRPs to attract large numbers of disappointed former Labor/Social Democrat voters, who felt their party had “sold out” and/or betrayed them. Mainstream conservative parties, on the other hand, are said to have responded by shifting right, in order to differentiate their policy program from the ones offered by more centrist left-wing competitors, and to have adopted a harsher stance on immigration and multiculturalism in order to prevent voters exiting and switching to hard-line PRRPs.

Of particular interest here, given our interest in explaining electoral breakthrough, is supply-side research proposing PRRPs may have found a “winning formula.” The term “winning formula” was coined by Kitschelt in his research into the growing popularity of PRRPs in German speaking European countries (Kitschelt, 1995). The winning formula, so Kitschelt argued at the time, was a party manifesto that combined neoliberal and culturally exclusionist authoritarian appeals. Kitschelt's winning formula was well-suited to explain the growing appeal of PRRPs in the 1980s, when it enabled PRRPs to distinguish themselves clearly from mainstream parties. However, Kitschelt would later revise his original winning formula (Kitschelt, 2004), when it turned out to be less suited to explain the surge in support for PRRPs in the 1990s as they began to adopt a more centrist socio-economic policy stance. Kitschelt's revised formula may not be without flaws (De Lange, 2007). However, his work nonetheless continues to spur PRRP researchers to search for a magic PRRP success formula.

The main difference between Kitschelt's original and new winning formula was a more dynamic understanding of party positioning and party competition, in which PRRPs were seen to move into “vacant electoral space,” abandoned or neglected by mainstream parties. According to Kitschelt's new thesis, it was a conscious strategic decision on the part of PRRPs to abandon their neoliberal stance, and to move to the center on socio-economic issues so the party could woo disappointed (left- and right-wing) mainstream party voters with exclusionist authoritarian appeals. Others have since explored this proposition further, and there is mounting evidence that PRRPs have discovered creative ways to unite strange socio-economic bedfellows. We already pointed to nativist “opposition to immigration” as a likely binding factor, and it seems plausible that “authoritarian appeals” could also count on the support of groups with diverging socio-economic interests. There may be additional means by which PRRPs can try to preserve unity among strange bedfellows. For example, as Rovny (2013) points out, it is not inconceivable that these parties deliberately engage in “position blurring” as a means to avoid scrutiny, and if that were to be the case, the unity among strange bedfellows could be said to be illusory and based on false consensus.

Several PRRP researchers have examined the role of “charismatic leadership” in the appeal of PRRPs (Van der Brug and Mughan, 2007; Weyland, 2017). PRRPs are often portrayed in the media as owing their success to charismatic leadership, and although PRRPs often attract disproportionate media attention, it remains unclear to what extent PRRP successes can be attributed to charismatic leadership (Mudde, 2007, p. 260–263). The effect of charismatic leadership on voter preferences is difficult to ascertain for a number reasons. First, the label “charismatic” is rather rubbery, and often used with the benefit of hindsight to describe leaders we know became remembered as having exceptional win over followers. Second, those looking from the outside may view a leader as exceptionally charismatic, but the leader in question may be exceptionally destructive and divisive within the organization. It is not uncommon for PRRP leaders to have remarkable external appeal, and to simultaneously wreak havoc in their own party. For example, in the late 1990s, Australia's One Nation experienced an internal power struggle (Ben-Moshe, 2001), as did France's Front National (Mudde, 2010), and the same fate later befell Belgium's Vlaams Belang (Pauwels and Haute, 2017).

PRRP scholars seem to agree that it is important to differentiate between internal and external leadership styles, and to pay due attention to PRRPs' capacity to avoid infighting and to retain internal cohesion. It will be important for all parties to avoid internal power struggles and ensuing public relations disasters. However, this is arguably even more important for PRRPs, this because they rely so heavily on binary us-them narratives (the virtuous people vs. the malicious power-hungry elite), and because signs of internal power struggles will undermine the credibility of messages portraying the party as merely giving voice to “the people.” Indeed, PRRPs set high expectations by portraying themselves as “the people's savior” and leaders of mainstream parties as not caring about the fate of ordinary people, and only being in politics to advance their personal interests.

To summarize, there is a large body of supply-side research examining strategic party positioning. The underlying idea in strategic positioning research is that voter preferences change first (as a spontaneous reaction to events and trends “out there” in society), and that PRRPs follow suit, by reading public sentiment, and by positioning themselves strategically to woo disgruntled voters who no longer feel catered for by mainstream parties. Although there has been growing recognition among scholars studying party manifestos that PRRPs not only read but also shape public sentiment, researchers following in this research tradition tend to show little interest in taking this into account in their analyses. Moreover, while leaders are seen as important to secure electoral success for PRRPs, the analysis focuses perhaps too much on individual level characteristics of the leader and not enough on how leaders play an active role in defining, shaping, and creating narratives that arouse demand-side grievances (Moffitt, 2015; Mols and Jetten, 2017; Wodak, 2019).

As we have shown elsewhere, PRRPs not only seek to “tap into” existing grievances, they also foment new grievances (Mols and Jetten, 2014). In our view, this has been a major challenge in research seeking to explain the appeal of PRRPs, where it manifests in a tendency to resort to unhelpful “either-or” thinking. As we will explain in more detail below, in order to make progress we will need to avoid either-or thinking, and step up efforts to integrate our knowledge of demand-side and supply-side factors.

As we saw, scholarly debate currently focuses heavily on five demand-side explanations relating to economic deprivation, rising inequality, fear of immigration, cultural anxiety, and cultural backlash. However, it should be clear from the above that there is room for improvement with regards to how we conceptualize voter preference formation. Whereas, authors studying strategic party positioning tend to view voter preference formation as the outcome of a shopping exercise, with voters latching onto parties that deal with most of their grievances, to enhance our understanding of why PRRPs have managed to break through in recent years, more dynamic models are needed. More specifically, what remains underappreciated is that voter attitudes and preferences are in large measure shaped by identity leadership and persuasive messaging that actively engages with the socio-structural context as it is experienced by the electorate.

It is clear that voter attitudes and preferences reflect a mixture of spontaneous and cultivated sentiments and policy preferences. This challenge is well-documented in the PRRP literature, and populism researchers are hence well aware that PRRP leaders both read and shape public sentiment (Rydgren, 2007; Mols, 2012). Indeed, the key question here is whether party leaders cue voters, or whether voters cue party leaders, and this is of course an unanswerable “chicken and egg” problem.

In our view, a number of lessons need to be heeded if we want to understand the way politicians can sway public opinion and subsequently harness these sentiments to secure election wins. First, as others have noted, we need to avoid “either-or” thinking, and focus our attention away from isolating variables toward studying the relationship between variables. Second, as shown in Figure 1, we propose using a more refined conceptual framework for thinking about supply-side factors. In our thinking, we distinguish between PRRPs' efforts to adjust to changes in voter demand “out there in society” (i.e., reading spontaneous grievances), and PRRPs' efforts to influence voter sentiment and induce demand by framing societal challenges in particular ways (cultivating grievances to increase demand). In addition, PRRPs will try to gauge whether their efforts to shape public sentiment have been successful, and use this assessment to decide whether to abandon or increase attention for the issue in question. In other words, PRRPs may be flexible in how they position themselves, and they might move either to the left or right of the political spectrum in their attempt to capture as many voters as possible. However, what should not be overlooked is that these parties play an active role in shaping public sentiment and inducing demand. To do so would be to overlook an important supply-side factor (ideological framing) and to underestimate the normative influence successful PRRPs can exert.

Rather than to review the state of the art in the PRRP literature, the aim of this paper is to advance a more refined conceptual understanding of PRRP support. More specifically, what remains poorly integrated is PRRPs capacity to induce/cultivate demand. In this section we will provide concrete examples of research into threat narratives and their effect on the electoral appeal of PRRPs. As we will see, the problem facing us is not so much a shortage in research findings, but limited progress integrating these specific (supply-side) insights into the broader field of populism and nativism research, which until now has remained divided into two more or less separate fields, namely demand- and supply research.

Our analysis proposes a more dynamic account of the way that supply- and demand-side factors interact and jointly determine the electoral success of the PRRP. How then does this work? There is some evidence for the interplay of these processes in previous research whereby PRRP researchers analyzed the narratives PRRPs use to increase their electoral appeal. As several scholars have shown, such narratives follow a familiar pattern, and pit “the virtuous people” against “the malicious elite” (Mudde, 2007; Moffitt, 2016). It is also widely accepted that PRRPs tend to scapegoat minorities, and that they use scare tactics in their narratives, blaming them for economic downturn and culture change in society. The overall picture that emerges from this body of research is one that depicts PRRPs and PRRP leaders as effective “scaremongers” capable of fuelling demand (Pisoiu and Ahmed, 2016).

Interestingly, by focusing on shared grievances, PRRP leaders read the social context and frame issues, creating a sense of shared victimhood, and use this sense of shared victimhood to unite strange socio-economic bedfellows. For example, it has become clear from analyses of PRRP leader speeches that PRRP leaders in different countries use the same narrative, a narrative that portrays society as embroiled in a conflict involving not two, but three groups, namely (1) the virtuous people, (2) the malicious leftist urban elite, and (3) migrants, refugees and other minorities, which are being portrayed as the malicious elite's clientele (Mols and Jetten, 2014). More specifically, what these analyses revealed was that immigrants and asylum-seekers are portrayed as benefiting from a rigged system and as a group that enjoys protection and privileges (granted by the malicious urban leftist elite). By framing society in this way, and by portraying minorities as “well-looked after,” PRRP leaders are able to frame “ordinary hard-working families” as the real victims, rather than immigrants, refugees, and other minorities. Indeed, the end conclusion of this standard narrative can be summarized as “the elite gain credit for constantly showing generosity, but it is ordinary hard-working families who are footing the bill.”

Likewise, research examining PRRP leader speeches revealed how PRRP leaders use nationalist nostalgia, speaking to collective grievances to promote the hardening of social norms. More specifically, this research showed that PRRP leaders use a remarkably similar sequential “no-guts- no glory” narrative, according to which (a) “the nation's glory has been lost,” (b) “the urban leftist elite is to blame,” (c) “restauration of the nation's glory will require matching previous generations' ability to be tough and unflinching,” (d) “the only leader capable of securing old glory is the person standing before you, and (e) “vote for me, and follow me into battle” (Mols and Jetten, 2014). The main advantage of analyzing speeches in this more detailed way is that it becomes clear that PRRP leaders do more than merely exaggerate or scaremonger. Rather, they carefully choose the way in which they categorize potential voters (“working families”), and rather than focus exclusively on the economic anxieties of blue-collar workers, they use narratives that enable large sections of the electorate (including relatively well-off middle class voters) to feel as though they are the victims of a rigged society and economy.

As we saw, it is now widely accepted that PRRPs have a remarkable ability to unite strange socio-economic bedfellows. Researches examining strategic party positioning have explored whether this ability to cater for different constituencies can be attributed to strategic choices in party manifesto. In our view, this is a pertinent question worth investigating further. However, our hunch is that PRRPs' ability to unite strange bedfellows does not stem from such choices, but from PRRP leaders' remarkably crafty “identity entrepreneurship” (Reicher and Hopkins, 2000) and “identity leadership” (Steffens et al., 2014). As many studies have shown, empathy and shared social identification are a prerequisite for persuasion, and from that perspective one would expect voters to only take an interest in a party's manifesto once they have embraced this party as “their” party (Turner, 1991).

In an ongoing search for a “winning formula,” PRRP leaders use carefully crafted narratives in which ordinary working families (rather than working class people) are being framed as the real victims of an allegedly rigged society. By using the categorization “working families” rather than “working class families,” and by portraying “the elite” as passionate advocates of immigration and multiculturalism who are (financially and culturally) out of touch with ordinary working families, PRRP leaders cast the net widely, and enable both low- and middle-income earners to feel as though they have all been left behind financially and culturally. This may explain why their narrative may appeal to such a diverse range of voters. After all, the claim that ordinary working families have been forgotten will have appeal among those already suffering economic hardship as well as those who fear that their privileged position will be lost in future (because they fear for their wealth, because of increasing societal inequality, or because of culture change due to rising numbers of immigrants).

This is perhaps the reason why PRRPs use “opposition to immigration” as a rallying cry to unite groups with opposing socio-economic interests. More specifically, research has shown that “immigration” is the overarching policy issue for PRRPs (Ivarsflaten, 2008, p. 18), that PRRPs have come to “own” the issue of “immigration” (Van der Brug and Fennema, 2003, p. 69), and that PRRPs know that voters will evaluate the party on their performance in this particular policy domain (Akkerman and de Lange, 2012, p. 579).

Finally, it would be useful to examine the extent and ways in which PRRPs use social media to simultaneously gauge how voters react to certain issues/events (spontaneous public sentiments) and how voters respond to different ways in which the issue/event can be framed (attempts to cultivate grievances and induce demand). Although obtaining evidence of such practices may not be straightforward (since PRRPs may prefer keep their campaign strategies secret), it would be highly informative to witness and document such practices, since it would provide us with direct evidence of the above-mentioned feedback loop, and of “demand” being partly spontaneous and partly induced/cultivated.

It is clear from research examining PRRP party manifestos that PRRPs have no coherent socio-economic program, and that socio-economic matters are secondary for these parties (Mudde, 2007, p. 119–137). This finding might surprise those who view PRRPs in a stereotypical way, as parties primarily attracting uneducated blue-collar workers, but it becomes less surprising once we consider the important role that the media plays in helping PRRPs with their messaging.

Although PRRPs may raise valid concerns, it is clear from this line of supply-side research that, by using alarmist narratives, PRRPs are able to attract disproportionate media attention and shape the public discourse. A case in point here is PRRPs' sustained attack on “political correctness.” Even if we accept that there are instances that can be described as “political correctness gone crazy,” and that such instances merit further investigation or correcting, it is an example of a rather mundane issue ending up attracting disproportionate attention and triggering “public outcry.” Indeed, PRRP leaders are not only notorious “merchants of doubt” (e.g., undermining faith in research evidence) but also remarkable “merchants of phantom problems,” and what helps these parties to attract attention to phantom problems is the fact that the mass media are often more than happy to give such narratives airtime, amplifying the message in the process.

Moreover, PRRPs go to great lengths gauging how voters might interpret societal developments (i.e., spontaneous grievances that emerge from events that trigger threat), and the fact that they too hire media advisors (or “spin doctors”) to help frame issues and craft messages (see feedback loop from “reading” to “shaping” voter sentiment in Figure 1) suggests that they are well aware that voters' preferences can be influenced, and that the media have considerable control over how voters will view their party. The question, though, is what impact carefully crafted messages have on actual voting behavior. We know from controlled laboratory experiments examining individual-level determinants that populist messages increase cynicism, in particular among those already sympathetic to a PRRP (Rooduijn et al., 2017), and that messages conveying symbolic threat exerts a stronger effect on anti-immigration attitudes than those conveying economic threats (Schmuck and Matthes, 2017). However, such experiments do not fully capture collective meaning-making processes, and this is why the findings of such experiments often have limited ecological validity.

Those studying the effect of the media (and media messages) on populist radical right attitudes seem well-aware of the need to account for collective-level factors. For example, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart (2007) studied the effects of news reports on immigration on PRRP voting in the Netherlands, thereby controlling for real-world events, and the findings of this study suggest that such news reports do indeed increase PRRP voting. Although this study has been criticized on methodological grounds (Pauwels, 2010), in our view it is encouraging that media and communication researchers are moving beyond (overly reductionist) single-cause explanations, and are looking for ways to integrate insights. We hope that the model we have presented in this paper will serve as a roadmap for such efforts.

As several authors noted, the populist and/or nativist “radical-right” has attracted disproportionate scholarly attention, and there is hence no shortage of articles and books about “right-wing populism.” A Google Scholar search for publications on the topic will reveal there are now ~265,000 sources mentioning the term “populism,” and although this number needs to be treated with caution (as the number may be inflated by the inclusion of sources on other topics merely mentioning the term populism, and deflated by missed sources using the terms “far-right” or “radical right” instead of “populism”), it nonetheless gives us a rough indication of just how much PRRPs have been studied.

It has become clear in recent years that PRRPs can no longer be dismissed as “fringe parties” condemned to permanent opposition. On the contrary, many PRRPs have broken through electorally, and are now represented in Parliament or in coalition government in many countries. Not surprisingly, this has reinvigorated 1990s debate about whether PRRPs have discovered “a winning formula,” and the question now presenting itself is whether these parties can be said to have discovered “a new winning formula.”

From the mid-1980s onwards, when European PRRPs suddenly began to attract a larger share of the votes in local and national elections, political scientists stepped up efforts to explain the growing electoral appeal of this likeminded party family. Broadly speaking, early research into the rising appeal of PRRPs focused on three factors, namely (a) the socio-economic conditions under which PRRPs thrive, (b) the composition of PRRPs' voter base, and (c) the appeal of PRRPs' messages and party manifestos. Although there is now a large body of literature examining each of these factors, the overall results are mixed, and many old assumptions and hunches have proven incorrect.

To conclude, we fully expect the search for the PRRP voter to continue, as well as the search for the independent variable best predicting PRRP support. We already noted there is growing consensus in PRRP research about the need to avoid either-or thinking in demand-side vs. supply-side research. Unfortunately, all too often populism research focuses on one or the other, but not both. As several authors have noted, there appears to be a “strict division of labour” between the two strands (Rydgren, 2007, p. 257; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018, p. 1671), and we agree this is unhelpful and needs to be rectified (Golder, 2016). We hope the model we are putting forward will help researchers looking for ways to integrate supply- and demand-side research.

We also expect the search for a (new) winning formula to continue, and we hope that our paper will enrich this particular search. In our view, PRRPs have indeed discovered a new winning formula, one that derives its strength from a combination of being able to read and shape grievances and public sentiments.

FM drafted the first version of this paper, the task of revising and strengthening the paper was undertaken by all authors equally, using a ca. 50/50 workload distribution. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the Australian Research Council's Discovery Project funding scheme (DP170101008).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^There is lively ongoing debate, in the populism literature, about definitions. In this paper, we use the term “populism” to refer to a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, namely “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite” (Mudde, 2007, p. 23), and the term “Populist Radical Right Parties” (PRRP) to refer to a family of parties that share a core ideology that includes (at least) a combination of nativism, authoritarianism, and populism (Mudde, 2014, p. 218).

Abou-Chadi, T. (2018). Electoral competition, political risks, and parties' responsiveness to voters' issue priorities. Elect. Stud. 55, 99–108.

Abou-Chadi, T., and Krause, W. (2020). The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties' policy positions: a regression discontinuity approach. Br. J. Political Sci. 50, 829–847. doi: 10.1017/S0007123418000029

Akkerman, T., and de Lange, S. L. (2012). Radical right parties in office: incumbency records and the electoral cost of governing. Gov. Opposition 47, 574–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2012.01375.x

Akkerman, T., de Lange, S. L., and Rooduijn, M. (2016). “Inclusion and mainstreaming? Radical right-wing populist parties in the new millennium,” in Radical right-wing populist parties in Western Europe, eds T. Akkerman, S. L. de Lange, and L. Rooduijn (London: Routledge), 19–46. doi: 10.4324/9781315687988

Albertazzi, D., and McDonnell, D. (2015). Populists in power. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315725789

Antonucci, L., Horvath, L., Kutiyski, Y., and Krouwel, A. (2017). The malaise of the squeezed middle: challenging the narrative of the ‘left behind’ brexiter. Competition Change, 21, 211–229. doi: 10.1177/1024529417704135

Ben-Moshe, D. (2001). One nation and the Australian far right. Patterns Prejudice 35, 24–40. doi: 10.1080/003132201128811205

Betz, H. G. (1994). Radical right-wing populism in Western Europe. London: Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-23547-6

Blizzard, B., and Batalova, J. (2019). Refugees and Asylees in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/refugees-and-asylees-united-states

Boomgaarden, H. G., and Vliegenthart, R. (2007). Explaining the rise of anti-immigrant parties: the role of news media content. Elect. stud. 26, 404–417. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2006.10.018

Carter, E. (2005). The Extreme Right in Western Europe: Success or Failure? Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Childers, T. (1976). The social bases of the national socialist vote. J. Contemp. Hist. 11, 17–42. doi: 10.1177/002200947601100404

Cingano, F. (2014). “Trends in income inequality and its impact on economic growth,” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 163 (Paris: OECD Publishing).

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226349251.001.0001

De Lange, S. L. (2007). A new winning formula? The programmatic appeal of the radical right. Party Polit. 13, 411–435. doi: 10.1177/1354068807075943

Dorling, D. (2016). Brexit: the decision of a divided country. Br. Med. J. 354:i3697. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3697

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. J. polit. econ. 65, 135–150. doi: 10.1086/257897

Evans, J. A. (2005). The dynamics of social change in radical right-wing populist party support. Comp. Eur. Polit. 3, 76–101. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110050

Falter, J. W. (1981). Radicalization of the middle classes or mobilization of the unpolitical? The theories of Seymour M. Lipset and Reinhard Bendix on the electoral support of the NSDAP in the light of recent research. Information 20, 389–430. doi: 10.1177/053901848102000207

Figueira, F. (2018). Why the current peak in populism in the US and Europe? Populism as a deviation in the median voter theorem. Eur. J. Gov. Econ. 7, 154−170.

Frank, R. (2013). Falling Behind: How Rising Inequality Harms the Middle Class. Vol. 4. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/9780520957435

Fritz, S. G. (1987). The NSDAP as volkspartei? A look at the social basis of the nazi voter. Hist. Teach. 20, 379–399. doi: 10.2307/493126

Geary, D. (2002). Nazis and workers before 1933. Aust. J. Polit. Hist. 48, 40–51. doi: 10.1111/1467-8497.00250

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: economic and cultural roots of the populist right. Br. j. sociol. 68, S57–S84. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12319

Golder, M. (2016). Far right parties in Europe. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 19, 477–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042814-012441

Goodwin, M., and Milazzo, C. (2017). Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for Brexit. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 19, 450–464. doi: 10.1177/1369148117710799

Goodwin, M. J. (2006). The rise and faults of the internalist perspective in extreme right studies. Representation 42, 347–364. doi: 10.1080/00344890600951924

Grofman, B. N., and Muller, E. N. (1973). The strange case of relative gratification and potential for political violence: the V-curve hypothesis. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 67, 514–539. doi: 10.2307/1958781

Guimond, S., and Dambrun, M. (2002). When prosperity breeds intergroup hostility: the effects of relative deprivation and relative gratification on prejudice. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 900–912. doi: 10.1177/014616720202800704

Halikiopoulou, D., and Vlandas, T. (2020). When economic and cultural interests align: the anti-immigration voter coalitions driving far right party success in Europe. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 17, 1–22. doi: 10.1017/S175577392000020X

Hamilton, R. F. (1983). Who Voted for Hitler? New Jeresy, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400855346

Heinisch, R. (2003). Success in opposition–failure in government: explaining the performance of right-wing populist parties in public office. West Eur. Polit. 26, 91–130. doi: 10.1080/01402380312331280608

Hochschild, A. R. (2018). Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York, NY: The New Press.

Hogan, J., and Haltinner, K. (2015). Floods, invaders, and parasites: immigration threat narratives and right-wing populism in the USA, UK and Australia. J. Intercult. Stud. 36, 520–543. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2015.1072907

Ignazi, P. (2003). Extreme right parties in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/0198293259.001.0001

Inglehart, R. F., and Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash. Harvard Kennedy School Working Paper No. RWP16–026. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2818659

Ivarsflaten, E. (2005). The vulnerable populist right parties: no economic realignment fuelling their electoral success. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 44, 465–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00235.x

Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comp. Polit. Stud. 41, 3–23. doi: 10.1177/0010414006294168

Jackman, R. W., and Volpert, K. (1996). Conditions favouring parties of the extreme right in Western Europe. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 26, 501–521. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400007584

Jetten, J. (2019). The wealth paradox: prosperity and opposition to immigration. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 49, 1097–1113. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2552

Jetten, J., Mols, F., Healy, N., and Spears, R. (2017). “Fear of falling”: economic instability enhances collective angst among societies' wealthy class. J. Soc. Issues 73, 61–79. doi: 10.1111/josi.12204

Jetten, J., Mols, F., and Postmes, T. (2015). Relative deprivation and relative wealth enhances anti-immigrant sentiments: the v-curve re-examined. PloS one 10:e0139156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139156

Jetten, J., Mols, F., and Steffens, N. K. (2020). Prosperous But Fearful of Falling: The Wealth Paradox, Collective Angst, and Opposition to Immigration. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. doi: 10.1177/0146167220944112. [Epub ahead of print].

Kitschelt, H. (1995). The Radical Right in Western Europe: a Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.14501

Kitschelt, H. (2004). Diversification and Reconfiguration of Party Systems in Postindustrial Democracies. Bonn: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Europäische Politik 3, 1–23.

Kurer, T., and Palier, B. (2019). Shrinking and shouting: the political revolt of the declining middle in times of employment polarization. Res. Polit. 6:053168019831164. doi: 10.1177/2053168019831164

Lefkofridi, Z., and Michel, E. (2014). Exclusive solidarity? Radical right parties and the welfare state. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Paper No. 2014/120. European University Institute. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2539503

Lloyd, T., and Lloyd, T. (2004). Why Rich People Give. London: Association of Charitable Foundations.

Lubbers, M., Gijsberts, M., and Scheepers, P. (2002). Extreme right-wing voting in Western Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 41, 345–378. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00015

Madden, P. (1987). The social class origins of Nazi party members as determined by occupations, 1919–1933. Soc. Sci. Q. 68:263.

Meguid, B. M. (2008). Party Competition Between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511510298

Moffitt, B. (2015). How to perform crisis: a model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Gov. Opposition 50, 189–217. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.13

Moffitt, B. (2016). The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Cambridge: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.11126/stanford/9780804796132.001.0001

Mols, F. (2012). What makes a frame persuasive? Lessons from social identity theory. Evid. Policy J. Res. Debate Pract. 8, 329–345. doi: 10.1332/174426412X654059

Mols, F., and Jetten, J. (2014). No guts, no glory: how framing the collective past paves the way for anti-immigrant sentiments. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 43, 74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.08.014

Mols, F., and Jetten, J. (2017). The Wealth Paradox: Economic Prosperity and the Hardening of Attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781139942171

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511492037

Mudde, C. (2010). The populist radical right: a pathological normalcy. West Eur. Polit. 33, 1167–1186. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2010.508901

Mudde, C. (2014). Fighting the system? Populist radical right parties and party system change. Party Polit. 20, 217–226. doi: 10.1177/1354068813519968

Mudde, C., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comp. Polit. Stud. 51, 1667–1693. doi: 10.1177/0010414018789490

Mühlberger, D. (1980). The sociology of the NSDAP: the question of working-class membership. J. Contemp. Hist. 15, 493–511. doi: 10.1177/002200948001500306

Niedermayer, O. (1990). Sozialstruktur, politische orientierungen und die unterstützung extrem rechter parteien in Westeuropa. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen, 21, 564–582.

Norris, P. (2005). Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511615955

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108595841

OECD (2019). Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/689afed1-en

O'Loughlin, J., Flint, C., and Shin, M. (1995). Regions and milieux in weimar Germany: the nazi party vote of 1930 in geographic perspective (Regionen und Milieus in der Weimarer Republik: Wählerstimmen im Jahr 1930 für die NSDAP aus geographischer Sicht). Erdkunde 305–314. doi: 10.3112/erdkunde.1995.04.03

Papadopoulos, Y. (2000). National Populism in Western Europe: An Ambivalent Phenomenon. Lausanne: Institut d'Etudes Politiques et Internationales, Université de Lausanne.

Pauwels, T. (2010). Reassessing conceptualization, data and causality: a critique of Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart's study on the relationship between media and the rise of anti-immigrant parties. Elect. stud. 29, 269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2010.02.006

Pauwels, T., and Haute, E. V. (2017). Caught Between Mainstreaming and Radicalisation: Tensions Inside the Populist Vlaams Belang in Belgium. London: LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog. Available online at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/69378

Piff, P. K., Stancato, D. M., Côté, S., Mendoza-Denton, R., and Keltner, D. (2012). Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 4086–4091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118373109

Pisoiu, D., and Ahmed, R. (2016). “Capitalizing on fear: the rise of right-wing populist movements in Western Europe,” in OSCE Yearbook 2015, (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG), 165−176. doi: 10.5771/9783845273655-165

Postmes, T., and Smith, L. G. (2009). Why do the privileged resort to oppression? A look at some intragroup factors. J. Soc. Issues 65, 769–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01624.x

Rooduijn, M., De Lange, S. L., and Van der Brug, W. (2014). A populist Zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe. Party polit. 20, 563–575. doi: 10.1177/1354068811436065

Rooduijn, M., Van der Brug, W., De Lange, S. L., and Parlevliet, J. (2017). Persuasive populism? Estimating the effect of populist messages on political cynicism. Polit. Gov. 5, 136–145. doi: 10.17645/pag.v5i4.1124

Rovny, J. (2013). Where do radical right parties stand? Position blurring in multidimensional competition. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 5, 1–26. doi: 10.1017/S1755773911000282

Rydgren, J. (2007). The sociology of the radical right. Annu. Rev. Soc. 33, 241–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752

Schmidt, V. A. (2017). Britain-out and Trump-in: a discursive institutionalist analysis of the British referendum on the EU and the US presidential election. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 24, 248–269. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2017.1304974

Schmuck, D., and Matthes, J. (2017). Effects of economic and symbolic threat appeals in right-wing populist advertising on anti-immigrant attitudes: the impact of textual and visual appeals. Polit. Commun. 34, 607–626. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2017.1316807

Sprong, S., Jetten, J., Wang, Z., Peters, K., Mols, F., Verkuyten, M., et al. (2019). “Our country needs a strong leader right now”: economic inequality enhances the wish for a strong leader. Psychol. Sci. 30, 1625–1637. doi: 10.1177/0956797619875472

Steffens, N. K., Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., Platow, M. J., Fransen, K., Yang, J., et al. (2014). Leadership as social identity management: Introducing the Identity Leadership Inventory (ILI) to assess and validate a four-dimensional model. leadersh. q. 25, 1001–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.05.002

Stoica, M. S. (2017). Political myths of the populist discourse. J. Study Relig. Ideolog. 16, 63–76.

Van der Brug, W., and Fennema, M. (2003). Protest or mainstream? How the European anti-immigrant parties have developed into two separate groups by 1999. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 42, 55–76. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00074

Van der Brug, W., Fennema, M., and Tillie, J. (2000). Anti-immigrant parties in Europe: Ideological or protest vote? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 37, 77–102.

Van der Brug, W., and Mughan, A. (2007). Charisma, leader effects and support for right-wing populist parties. Party Polit. 13, 29–51. doi: 10.1177/1354068806071260

van Spanje, J. (2018). “Parrot Parties: established parties' co-optation of other parties' policy proposals,” in Controlling the Electoral Marketplace (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 17–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-58202-3_2

Wagner, M., and Meyer, T. M. (2017). The radical right as niche parties? The ideological landscape of party systems in Western Europe, 1980–2014. Polit. Stud. 65, 84–107. doi: 10.1177/0032321716639065

Wear, R. (2008). Permanent populism: The Howard government 1996–2007. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 43, 617–634. doi: 10.1080/10361140802429247

Weyland, K. (2017). “Populism: a political-strategic approach,” in The Oxford Handbook of Populism, eds C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. A. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 48–72. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.2

Wiepking, P., and Breeze, B. (2012). Feeling poor, acting stingy: the effect of money perceptions on charitable giving. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 17, 13–24. doi: 10.1002/nvsm.415

Williams, M. H. (2006). The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Parties in West European Democracies. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781403983466

Wodak, R. (2017). The “Establishment,” the “Élites,” and the “People”: who's who? J. Lang. Polit. 16, 551–565. doi: 10.1075/jlp.17030.wod

Keywords: populism, nativism, elections, voting, journalism

Citation: Mols F and Jetten J (2020) Understanding Support for Populist Radical Right Parties: Toward a Model That Captures Both Demand-and Supply-Side Factors. Front. Commun. 5:557561. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.557561

Received: 30 April 2020; Accepted: 07 September 2020;

Published: 23 October 2020.

Edited by:

Rasha El-Ibiary, Future University in Egypt, EgyptReviewed by:

Gijs Schumacher, University of Amsterdam, NetherlandsCopyright © 2020 Mols and Jetten. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Frank Mols, Zi5tb2xzQHVxLmVkdS5hdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.