- 1School of Environment and Natural Resources, College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

- 2Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, NSW, Australia

- 3Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, College of Forestry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, United States

Natural resource management (NRM) is conducted within a complex context. This is particularly true at the interface of public and private interests where policy and management actions are often closely scrutinized by stakeholders. In these settings, natural resource managers often seek to achieve multiple objectives including ecosystem restoration, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and the provision of recreation opportunities. While some objectives may be complementary, in many cases they involve tradeoffs that are contested by stakeholders. Substantial prior work has identified concepts related to trust as critical to the success of natural resource management particularly in cases of high complexity and uncertainty with high stakes for those involved. However, although regularly identified as a central variable of influence, trust appears to be conceptualized differently or entangled with related constructs across this prior research. Moreover, much of the research in NRM considers trust as an independent variable and considers the influence of trust on other variables of interest (e.g., acceptance of a particular management practices, willingness to adopt a best management practice). In this paper, we develop a conceptualization of trust drawing on different literature areas and consider how trust is related to constructs such as trustworthiness and confidence. We then consider trust in the context of natural resource management drawing on examples from the U.S. and Australia. We then consider implications of these findings for building trust in natural resource management.

Introduction

Given the centrality of natural resources to well-being, societies have developed a variety of institutions to govern how decisions are made. In the United States (US) and Australia, where we have primarily focused our research, responsibility for the management of natural resources typically rests with government agencies. While their specific missions differ, these natural resource management (NRM) agencies are charged with managing resources in the public interest to provide for both current and future generations. In practice, NRM often consists of balancing diverse and sometimes competing interests. In this paper, we consider the role of trust in NRM organizations and practitioners as they seek to accomplish agency objectives while navigating tradeoffs and competing interests.

A substantial body of research has identified trust as a key contributor to successful stakeholder engagement in NRM decision-making (e.g., Shindler et al., 2002; Davenport et al., 2007; Beunen and de Vries 2011; Cooke et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2012; Toman et al., 2014). In particular, public trust in agencies and staff is considered a key influence on public support for management actions (Stankey and Shindler 2006; Leahy and Anderson 2008; ter Mors et al., 2010; Absher and Vaske 2011; Toman et al., 2011). Despite considerable research examining trust, several gaps in our understanding of this key concept remain. While prior work provides substantial evidence of the importance of trust in public and stakeholder acceptance of NRM practices, less is known about how trust is developed and maintained in NRM settings. This gap is addressed in this paper.

What Is Trust? Descriptions From Prior Literature

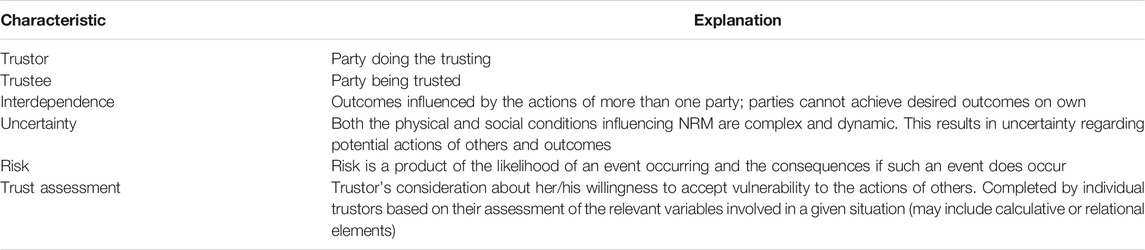

Research across a broad range of disciplines has examined trust (Stern and Coleman, 2015). It is not surprising then that there is some variation in how trust has been conceptualized. In some cases, trust appears to be conflated with related concepts including confidence (e.g., Mayer et al., 1995) and trustworthiness (e.g., Sharp et al. 2013b). In this paper, we specifically define trust as a willingness to rely upon another person or organization based upon positive expectations of their intentions or behavior (Sharp et al., 2013a; adapted from; Mayer et al., 1995; Rousseau et al., 1998). Several important elements of trust embedded in this definition merit additional consideration (see Table 1 for description of key elements).

This approach views trust as involving a relationship between two parties where a trustor (party doing the trusting) is dependent on the actions of the trustee (party being trusted) to achieve some desired outcome. This relationship includes interdependence as the interests of the trustor depend to some degree on the actions of the trustee. This interdependence contributes to a degree of uncertainty about the outcomes of decisions. This uncertainty creates some risk about the whether the trustor’s interests will be realized. To the extent there is uncertainty, participants will also experience vulnerability, a key element of relationships based on trust. The degree of trust held by a trustor is determined by their assessment regarding their willingness to accept the vulnerability that may result from the trustee’s actions.

In the subsequent sections, we briefly elaborate on characteristics of the trustor, characteristics of the trustee, and additional contextual characteristics relevant to understanding trust dynamics in NRM contexts.

Characteristics of the Trustor

Individual trustors have personal attributes (e.g., values, beliefs, attitudes, risk tolerance) and prior experiences that influence their trust assessments. It is difficult to tease out the influence of personal attributes and context. Researchers have suggested that individuals vary in the degree they are predisposed to trust others (Stern and Coleman, 2015). Mayer et al. (1995), (p.716) refer to this as a “propensity to trust” and describe it as a general willingness to trust others. Stern and Coleman (2015) go further and note that while dispositional trust may be context-independent (i.e., a personality trait towards generally trusting others), in other cases, it may result from attributes of the specific situation (e.g., trusting particular individuals in a particular position or institutions that hold authority).

Characteristics of the Trustee

Trustors evaluate characteristics of the trustee to determine if trust is warranted. Mayer et al. (1995) identified three antecedents of trust: ability (i.e. trustor’s perception of the trustee’s knowledge, skills and competencies); benevolence (i.e. the extent to which a trustor believes that a trustee will act in the best interest of the trustor); and, integrity (i.e. the extent to which the trustor perceives the trustee as acting in accord with a set of values and norms shared with, or acceptable to, the trustor). Evaluation of these factors influences an individual’s perceived trustworthiness. A recent review found evidence of the importance of these characteristics to stakeholder trust assessments in an NRM context (Shindler et al., 2014).

Parties in NRM Cases

There are typically three different types of parties involved in NRM cases: NRM agencies (typically government organizations with legal jurisdiction over particular resources), natural resource practitioners (i.e., personnel employed by NRM agencies), and other stakeholders (all others with an interest in the outcome of a decision, often including some combination of local residents, property owners, private businesses, etc.). The research literature highlights the importance of distinguishing between these parties because trustors often hold different levels of trust in local practitioners and the larger, government organizations within which they work (Mazur and Curtis 2006; Davenport et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2012; Sharp and Curtis 2014).

Despite the multi-party nature of NRM, prior research has often conceptualized trust as a dyadic relationship between an individual stakeholder and the management agency or specific practitioners. However, NRM decision contexts are typically characterized by a range of practitioners representing one or more agencies, a potentially diverse set of stakeholders, and a complex web of relationships developed over time. The result is that a stakeholder’s willingness to accept vulnerability is influenced by both their trust in the NRM agency and/or specific NRM practitioners as well as their relationships with the larger group of participants involved in that process (e.g., Cvetkovich and Nakayachi, 2007).

Ongoing Interactions

NRM often involves repeated interactions among parties over time. The legacy of past interactions and decisions will influence the trust stakeholders may bring to any particular NRM decision (Davenport et al., 2007). An example from our research includes the removal of willows (an introduced species) in southeast Australia where willows can outcompete native species (see Mendham and Curtis, 2015; Mendham and Curtis, 2018 for additional explanation of this topic). The regional Catchment Management Authority (CMA) removed willows and replanted native species along rivers and streams on both public and private land. However, in some instances the CMA did not seek permission from private land owners before completing this work. Willows are valued by property owners as they help stabilize banks and provide shade for livestock. In many cases, the willows were planted by the relatives of current property owners creating an emotional attachment. Ultimately, these actions of the CMA led to a loss of trust that subsequently influenced judgments about the social acceptability of other NRM programs and practices (Mendham and Curtis 2015; Mendham and Curtis, 2018). As this example illustrates, trust is dynamic and past actions may influence the trust held by stakeholders as they engage in future decisions and in different contexts.

Developing Trust Through Demonstrating Trustworthiness

Successfully building trust may seem an impossible challenge given the complex nature of NRM, however, we have found that emphasizing the trust antecedent of trustworthiness provides an effective framework for practitioners to monitor, reflect on, and adapt how they engage with stakeholders to develop and maintain trust. While there are multiple factors that may influence the trust any given NRM decision, by emphasizing the trustees’ attributes (ability, benevolence, and integrity of the relevant NRM practitioners and the agencies they represent), trustworthiness can help NRM practitioners and agencies focus on those actions largely within their control that can influence the degree of trust held by stakeholders. Accordingly, we have found that an emphasis on trustworthiness resonates with NRM practitioners and agencies and can be readily applied as they consider how to contribute to the development and maintenance of trust.

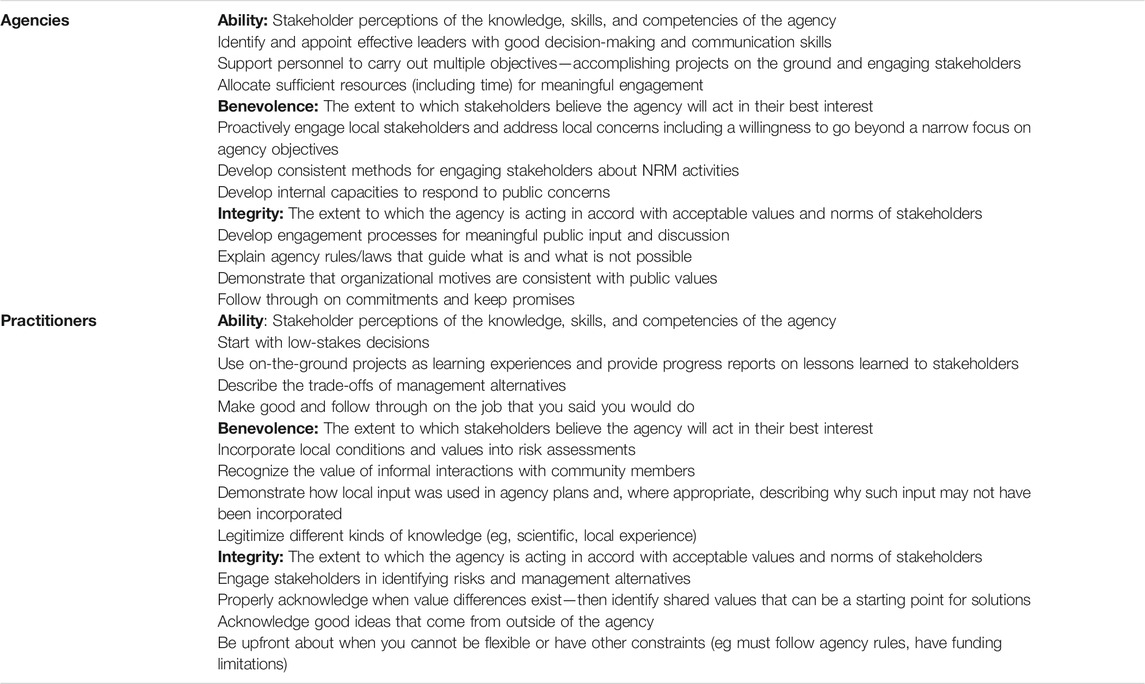

Drawing on prior research, we consider how NRM agencies and practitioners can demonstrate ability, benevolence, and integrity (Table 2, adapted from Shindler et al., 2014). At the agency level, agency leaders can contribute to trustworthiness by developing an organizational culture that values and promotes trustworthy characteristics, supports the efforts of staff to engage in genuine interactions with stakeholders, demonstrates that organizational motives are consistent with public expectations (ter Mors et al., 2010), and ensures that decision-making processes are open and transparent. To demonstrate the agency’s ability, NRM agencies should be thoughtful about who they appoint to lead planning and public engagement efforts. Appointed personnel should be supported by emphasizing the value of public engagement efforts as not simply a means to an end but as providing meaningful contributions in and of themselves. Additionally, agencies can demonstrate a real commitment to public engagement by providing sufficient time and resources to allow these activities to be undertaken effectively and being open to modifying plans based on ideas and suggestions generated through these efforts. There may also be the need to provide some foundational training to participants so they can effectively contribute to discussions and decision-making. There should also be sufficient time taken so that concerns and suggestions that arise can be addressed or explored.

TABLE 2. Developing and demonstrating trustworthiness (adapted from Shindler et al., 2014).

NRM agencies can demonstrate their integrity by setting realistic expectations of the actions that can be taken based on existing constraints (e.g., budgets, personnel available, expertise) and relevant laws and legal guidance. Agencies can also explain the values that drive the their efforts and describe how these values are proposed decisions align with these larger values. Lastly, agency leaders should ensure that any commitments are fulfilled.

Ultimately, the starting point for building trust is often at the local level between agency practitioners and individual stakeholders. To demonstrate trustworthiness, we recommend practitioners begin by engaging stakeholders on low-stakes decisions where there is less conflict about overall goals or potential risks of harm to stakeholder values (Antuma et al., 2014; DuPraw 2014; Toman et al., 2019). Practitioners can further demonstrate their ability by completing a thorough assessment of alternative approaches to achieve desired outcomes including describing potential tradeoffs that may occur between different approaches. Perhaps of greatest influence on perceived integrity, is the extent local practitioners “walk-the talk” and follow through on proposed activities. To demonstrate benevolence, practitioners can illustrate the genuine value placed on stakeholder views by describing how such input is incorporated into management plans or, if not, providing the rationale for such decisions. And while doing so may feel counter-intuitive, practitioners can help illustrate their integrity by acknowledging that real value differences may exist between stakeholders and between stakeholders and the agency on some topics. Such differences should not be minimized but they also do not need to prevent all work from moving forward as practitioners invest in identifying areas of common ground about the need for action. In engaging in such discussions, it is important to avoid over promising with the goal of making everyone happy but, instead to be clear about rules, restrictions, or limited resources that may constrain desired actions or outcomes.

We conclude by highlighting three specific contexts where NRM agencies and practitioners can demonstrate trustworthiness.

Engage Stakeholders in Meaningful Interactions

There is no substitute for directly engaging stakeholders to demonstrate trustworthiness; meaningful interactions offer a means to contribute to perceptions of ability, benevolence, and integrity. While decision-making rules often include a formalized process for stakeholders to provide input into a particular decision (e.g., public review mandated through the National Environmental Policy Act in the US; NEPA), on their own, these processes should not be viewed as a description of best practice for engaging stakeholders (e.g., Shindler et al., 2002). Indeed, the review and consultation practices commonly employed to comply with NEPA guidelines provide limited opportunities for meaningful interactions between different stakeholders or between stakeholders and agency managers. Rather than contributing to the development of trust, such approaches may suggest a lack of concern for stakeholder values and ideas (potentially reducing perceived benevolence) and are likely to reinforce adversarial relationships. Thus, at an agency level, it is important to demonstrate a commitment to meaningful public engagement that goes beyond the minimum level of involvement mandated by regulations. Such support can be demonstrated by providing training for personnel to effectively facilitate these activities, emphasizing early engagement of stakeholders, and demonstrating how participant feedback will be integrated into strategies and plans.

Substantial research has illustrated the importance of providing opportunities for meaningful interactions at the local level. By this we mean, providing venues where stakeholders can engage one another and managers in back-and-forth discussions to search for common ground (contributing to perceived integrity of practitioners and other stakeholders through identifying shared values). Such interactions also allow stakeholders to explore the rationale of proposed actions by asking questions that allow them to consider the proposed actions in light of their existing knowledge, beliefs and prior experiences. In addition, these interactive experiences allow resource management personnel to learn of and consider different approaches to accomplish agency objectives based on suggestions provided by local stakeholders. We have found that providing opportunities for these discussions on the ground, including through field trips and demonstration sites, can be particularly effective as these processes allow participants to improve their understanding of the issue at hand and provide opportunity for them to talk through the broader goals agencies are seeking to achieve, potential actions to do so, and likely outcomes (including tradeoffs) of these actions (e.g., Toman et al., 2006; Toman et al., 2008). Such interactive approaches align with our understanding of how adults learn and incorporate new information (e.g., Toman et al., 2006). Moreover, engaging stakeholders in this way provides opportunities for managers to demonstrate the trustworthiness attributes of ability, benevolence, integrity.

One additional key point to consider, is the importance of providing opportunities for meaningful interaction during the early stages of the decision-making process so stakeholders can contribute to setting project objectives and deciding among alternative management strategies (e.g., Wondolleck and Yaffee, 2000). Some of our recent work provides evidence that engaging in high-level discussions of this nature can build trust as participants begin to recognize alignment between their values and contemporary NRM policies and practices (e.g., restoring ecological function, improving habitat for native wildlife, reducing the risk of unnatural and catastrophic disturbances, etc.) even if they disagree about how to manage specific tradeoffs likely to arise as things move towards implementation (e.g., preferences for specific management practices) (Toman et al., 2015).

Identifying Values, Threats and Ways Forward at the Local Level

Actions perceived as associated with national-level NRM issues can lead to stakeholders adopting entrenched positions, with little likelihood of compromise and therefore, little progress towards action. In such cases, the perceived trustworthiness of local NRM practitioners is unlikely to overcome concerns about the trustworthiness of the management agencies or other stakeholder groups without considerable effort. If this is the case, agencies are encouraged to focus on identifying the values local stakeholders attach to a specific resource or environmental asset and gathering their ideas about the threat(s) to that resource or asset, and how both the agency and local stakeholders can work together to protect those values. Some of these tasks can be one-off or stand-alone activities (e.g., a workshop to identify values). We have seen particular progress establishing platforms and processes that are ongoing and embrace a range of tasks and are therefore, more likely to lead to a shared understanding of where we are heading and how to proceed. Doing so will contribute to perceptions of benevolence by demonstrating genuine interest in stakeholder values.

In our experience, engaging in such efforts can help participants shift their focus from a dogmatic response “for” or “against” activities depending on alignment with their previously help positions to consider how proposed actions align with their larger values. For example, in some work in communities adjacent to public forests with high tree densities, we found that environmental groups were more willing to accept timber harvesting with the aim of reducing the threat of fire after engaging in discussions of this nature at the local level. Indeed, in one recent study we found that despite substantial past conflict about timber harvesting, a collaborative group with membership from environmental and extractive interests agreed to amend the local forest plan to allow the removal of larger diameter trees (up to 21 inches from a previous cap of 16 inches) when doing so would contribute to achieving forest restoration goals, including the reduction of risks posed by wildfires (Walpole et al., 2017; Toman et al., 2019).

Perceived Risks of Inaction May Provide an Opportunity to Bring Groups Together to Develop Trust

While conflict in NRM is often focused on the risks of negative impacts from proposed management activities, it is important to recognize that there are also risks associated with inaction. Highlighting such risks may provide an impetus to bring stakeholders with different attitudes together. We have seen substantial evidence of this in our work on wildland fire and fuel management. While some individuals or groups may oppose timber harvesting or the use of prescribed fire, local practitioners can illustrate the likely threat to a shared value if no action is taken. For example, without thinning or planned burns, forest density is likely to increase and raise the potential for a catastrophic fire (e.g., Toman et al., 2019). Highlighting the potential risks associated with wildfires that may be particularly damaging when occurring in these altered systems has enabled local NRM practitioners to effectively engage stakeholders with different attitudes recognize shared values and engage in discussions about management options.

Conclusion

In the complex modern era of NRM, trust is increasingly important but increasingly difficult to build and maintain. Trust is an important element of the social capital of an individual or organization. When trust is strong, this enables individuals and organizations to operate more effectively, including by reducing the time and effort required to engage stakeholders who will be more willing to provide advice based on their local knowledge, forgive mistakes, and consider suggestions that may appear at odds with their existing beliefs or attitudes.

Some managers may feel that dedicating time and resources to building trust pulls them away from the “real work” of NRM. While we recognize such deliberate efforts to engage stakeholders will likely increase planning times and reduce the pace of implementation of management projects in the near-term, ultimately, doing so can provide a foundation for future success. In recent work, stakeholders in two ecological restoration efforts described how initial investments in building relationships and addressing low-stakes decisions contributed to a shift away from the adversarial relationships that had characterized NRM in their areas and contributed to broader success than would have been possible otherwise (Toman et al., 2019). Ultimately, we argue that trust is critical to successful NRM and should be viewed as a central component of all NRM activities. This is particularly true today as past conflict regarding NRM decisions has, in many cases, resulted in a deficit of trust among stakeholders. Navigating this situation can feel overwhelming to managers who may feel they have limited expertise to facilitate trust building activities while still being held accountable for implementing agency directives.

Despite these challenges, prior research has illustrated multiple cases where local resource management personnel have succeeded in their efforts to develop trust with local stakeholders. From our perspective, the key has been for these practitioners to focus their efforts on demonstrating their trustworthiness (through demonstrating ability, benevolence, and integrity).

Much of the onus falls to agency leaders to provide the support and resources to build on such successes. This includes demonstrating a commitment by investing in building the skills of staff to effectively engage stakeholders and rewarding those who do so. Moreover, planning should include sufficient time to undertake meaningful public engagement and to consider the most appropriate approach in each context. Such commitment will contribute to creating conditions conducive to demonstrating trustworthiness and developing trust.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this article are not publicly available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ET, dG9tYW4uMTBAb3N1LmVkdQ==.

Author Contributions

ET took the lead on developing the manuscript. AC and BS reviewed drafts and provided feedback and suggestions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Absher, J., and Vaske, J. (2011). The role of trust in residents’ fire wise actions. Int. J. Wildland Fire 20 (2), 318–325. doi:10.1071/WF09049

Antuma, J., Esch, B., Hall, B., Munn, E., and Sturges, F. (2014). Restoring forests and communities: lessons from the collaborative forest landscape restoration program. Missoula, Montana: The National Forest Foundation.

Beunen, R., and de Vries, J. R. (2011). The governance of Natura 2000 sites: the importance of initial choices in the organisation of planning processes. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 54 (8), 1041–1059. doi:10.1080/09640568.2010.549034

Cooke, B., Langford, W. T., Gordon, A., and Bekessy, S. (2012). Social context and the role of collaborative policy making for private land conservation. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 55 (4), 469–485. doi:10.1080/09640568.2011.608549

Cvetkovich, G., and Nakayachi, K. (2007). Trust in a high-concern risk controversy: a comparison of three concepts. J. Risk Res. 10 (2), 223–237. doi:10.1080/13669870601122519

Davenport, M. A., Leahy, J. E., Anderson, D. H., and Jakes, P. J. (2007). Building trust in natural resource management within local communities: a case study of the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie. Environ. Manag. 39 (3), 353–368. doi:10.1007/s00267-006-0016-1

Dirks, K. T., and Ferrin, D. L. (2001). The role of trust in organizational settings. Organ. Sci. 12 (4), 450–467. doi:10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640

DuPraw, M. E. (2014). Illuminating capacity-building strategies for landscape-scale collaborative forest management through constructivist grounded theory. PhD dissertation. Fort Lauderdale, Florida: Nova Southeastern University.

Krannich, R. S., and Smith, M. D. (1998). Local perceptions of public lands natural resource management in the rural west: toward improved understanding of the “revolt in the west”. Soc. Nat. Resour. 11, 677–695. doi:10.1080/08941929809381111

Leahy, J. E., and Anderson, D. H. (2008). Trust factors in community-water resource management agency relationships. Landsc. Urban Plann. 87, 100–107. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.05.004

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20 (3), 709–734. doi:10.2307/258792

Mazur, N., and Curtis, A. (2006). Risk perceptions, aquaculture, and issues of trust: lessons from Australia. Soc. Nat. Resour. 19, 791–808. doi:10.1080/08941920600835551

Mendham, E., and Curtis, A. (2015). Social benchmarking of north central catchment authority gunbower island project. Report to the north central catchment management authority. Albury, NSW: Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, Technical report 81.

Mendham, E., and Curtis, A. (2018). Local stakeholder judgements of the social acceptability of applying environmental water in the Gunbower Island forest on the Murray River, Australia. Water Pol. 20, 218–234. doi:10.2166/wp.2018.170

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., and Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 393–404. doi:10.5465/amr.1998.926617

Sharp, E. A., Thwaites, E. R., Curtis, A., and Millar, J. (2013a). Factors affecting community-agency trust before, during and after a wildfire: an Australian case study. J. Environ. Manag. 130, 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.08.037

Sharp, E. A., Thwaites, E. R., Curtis, A., and Millar, J. (2013b). Trust and trustworthiness: conceptual distinctions and their implications for natural resources management. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 56 (8), 1246–1265. doi:10.1080/09640568.2012.717052

Sharp, E., and Curtis, A. (2014). Can NRM agencies rely on capable and effective staff to build trust in the agency? Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 21 (3), 268–280. doi:10.1080/14486563.2014.881306

Shindler, B. A., Brunson, M., and Stankey, G. H. (2002). Social acceptability of forest conditions and management practices: a problem analysis. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW‐GTR‐537. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 68 p. Available at: https://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr537.pdf.

Shindler, B., Olsen, C., McCaffrey, S., McFarlane, B., Christianson, A., McGee, T., et al. (2014). Trust: a planning guide for wildfire agencies and practitioners – an international collaboration drawing on research and management experience in Australia, Canada, and the United States. A joint fire science program research publication. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University.

Smith, J., Leahy, J., Anderson, D., and Davenport, D. (2012). Community/agency trust and public involvement in resource planning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 26 (4), 452–471. doi:10.1080/08941920.2012.678465

Stankey, G. H., and Shindler, B. (2006). Formation of social acceptability judgments and their implications for management of rare and little-known species. Conserv. Biol. 20 (1), 28–37. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00298.x

Stern, M. J., and Coleman, K. J. (2015). The multidimensionality of trust: applications in collaborative natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 28 (2), 117–132. doi:10.1080/08941920.2014.945062

ter Mors, E., Weenig, M. W. H., Ellemers, N., and Daamen, D. D. L. (2010). Effective communication about complex issues: perceived quality of information about carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS) depends on stakeholder collaboration. J. Environ. Psychol. 30 (4), 347–357. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.06.001

Toman, E., Brenkert-Smith, H., Curtis, A., Rogers, M., and Stidham, M. (2015). Managing multi-functional landscapes at the interface of public forests and private land: advancing understanding through a comparison of experience in U.S. and Australia. Final Project Report. Joint Fire Science Program. Project ID: 12-2-01-59 https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/21103030/1000006261_published_report.pdf (Accessed January 15, 2021).

Toman, E., Shindler, B., Absher, J., and McCaffrey, S. (2008). Post-fire communications: the influence of site visits on public support. J. For. 106 (1), 25–30, doi:10.1093/jof/106.1.25

Toman, E., Shindler, B., and Brunson, M. (2006). Fire and fuel management communication strategies: citizen evaluations of agency outreach programs. Soc. Nat. Resour. 19, 321–336. doi:10.1080/08941920500519206

Toman, E., Shindler, B., McCaffrey, S., and Bennett, J. (2014). Public acceptance of wildland fire and fuel management: panel responses in seven locations. Environ. Manag. 54, 557–570. doi:10.1007/s00267-014-0327-6

Toman, E., Stidham, M., Shindler, B., and McCaffrey, S. (2011). Reducing fuels in the Wildland Urban Interface: community perceptions of agency fuels treatments. Int. J. Wildland Fire 20 (3), 340–349.

Walpole, E. G., Toman, E., Wilson, R. S., and Stidham, M. (2017). Shared visions, future challenges: a case study of three collaborative forest landscape restoration program locations. Environ. Soc. 22 (2), 35. doi:10.5751/ES-09248-220235

Keywords: trust, public involvement and engagement, natural resource management, conflict, stakeholder acceptability

Citation: Toman EL, Curtis AL and Shindler B (2021) What’s Trust Got to do With it? Lessons From Cross-Sectoral Research on Natural Resource Management in Australia and the U.S.. Front. Commun. 5:527945. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.527945

Received: 18 January 2020; Accepted: 23 December 2020;

Published: 29 January 2021.

Edited by:

Joseph A. Hamm, Michigan State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Grand Ann, The Open University, United KingdomKaren M. Taylor, University of Alaska Fairbanks, United States

Copyright © 2021 Toman, Curtis and Shindler. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eric Lee Toman, dG9tYW4uMTBAb3N1LmVkdQ==

Eric Lee Toman

Eric Lee Toman Allan Lindsay Curtis

Allan Lindsay Curtis Bruce Shindler

Bruce Shindler