- Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation, Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand

Drawing upon an ongoing ethnography with low-wage migrant workers in Singapore, this article builds on the theoretical framework of the culture-centered approach (CCA) to explore the experiences of the workers amid COVID-19 outbreaks in dormitories housing them. The CCA foregrounds the interplays of communicative and material inequalities, suggesting that the erasure of infrastructures of voices among the margins reproduces and circulates unhealthy structures that threaten the health and well-being of the working classes. The voices of the low-wage migrant workers who participated in this study document the challenges with poor housing, poor sanitation, and food insecurity that are compounded with the absence of information and voice infrastructures. Amid the everyday threats to health and well-being that are generated by neoliberal reforms across the globe, the hyper-precarious conditions of migrant work rendered visible by the trajectories of COVID-19 call for structurally transformative futures that are anchored in the voices of workers at the margins of neoliberal economies.

Introduction

Shameem had traveled to Bangladesh 11 years ago. He has lived in a wide range of accommodations in Singapore. He shares how when he first came, he lived in a container. He shares that life in the container was challenging. The conditions were unlivable. He shares that he shared the space in the container with rodents and cockroaches. When he compares life in the container with life in the dormitory he lives in now, not much has changed in the decade. He voices how workers are piled on “top of each other” in the room, with little room to move. He shares that he has felt all along that an outbreak such as the one we are witnessing now was waiting to happen. He shares anger and despair at the knowledge that the outbreak could have been prevented. But no one really cared, he points out. He also states that having decent housing is the right of the worker, and the worker does not need alms. The plight of the worker is not visible to anyone in Singapore (fieldnotes, April 25, interview).

Singapore's authoritarian techniques of disciplining labor form the infrastructures for propping up, circulating, and generating profits from the “Singapore model” of extreme neoliberalism. I define extreme neoliberalism as the free market ideology pushed beyond its organizing limits, with the structuring of the state as an authoritarian instrument of control that silences and co-opts worker collectivization, generating precarity while simultaneously deploying the logics of business-friendliness to enable the mobility of capital across spaces/borders1. Extreme neoliberalism is held up by the work of communicative infrastructures that simultaneously erase the symbolic registers for comprehending the deep inequalities produced by the neoliberal state through the combination of authoritarian control and accelerated propaganda. Singapore's authoritarian neoliberalism, as an assemblage of “coercive legal, institutional, and policy processes” (Bruff, 2014, p. 112) to govern by moralizing the individual, family, and community, draws upon a wide array of techniques of surveillance and violence incorporated into everyday life. Springer (2015) theorizes violent neoliberalism, referring to the “the kaleidoscope of violence that is intercalated within neoliberalism's broader rationality of power,” (p. 12) arguing that violence constitutes the deep inequalities produced by neoliberalism and is in turn, constituted by these inequalities. He suggests that this violence is both exceptional, appearing “to fall outside of the rule, usually by being so intense in its manifestation,” and “in a dialectic relationship with exemplary violence, or that violence which constitutes the rule” (p. 2).

This interplay of violence and authoritarianism is incessantly normalized in extreme neoliberalism through the everyday acts of “communicative inversions” (Dutta, 2015), reversals of materiality through symbolic productions, and strategic communicative erasures. As both a role model and pedagogue of extreme neoliberalism since the 1980s, Singapore has continually experimented with and perfected the techniques of authoritarian repression, exploitation of labor, and accumulation of primitive capital. It has invented the statecraft of disciplining labor and silencing dissent as model governmentality, while turning itself into the Asian gateway for transnational capital. The technologies and techniques of extreme neoliberalism are held up by a reputational economy that projects the account of a hyper-efficient state celebrated as the model of development, embodied in its “smart city” imaginary/propaganda leapfrogging from the “Third world to the first” at the frontiers of global capitalist expansion. This “smart city” template is circulated across nation states as a model for growth-driven development punctuated by profiteering across global networks of capital while simultaneously disseminating a pedagogy of authoritarian techniques of disciplining the margins (Tan, 2012; Dutta and Kaur-Gill, 2018; Dutta, 2019a,b). The extreme inequalities, alongside normative practices of disciplining workers, critics, and activists form a mobile infrastructure of the “Singapore model,” to be copied into state formations elsewhere, “rolling out” a police state to facilitate and catalyze accelerated capital accumulation (Tansel, 2017; Bruff and Tansel, 2019). Singapore's “smart” governance assembles a collection of laws, surveillance technologies, controls over institutions and civil society, and police interventions aimed at repression while simultaneously “rolling back” the welfare-based role of the state. At the heart of the “smart city” infrastructure of Singapore is the exploited labor of low-wage migrant workers, accompanied by the strategic deployment of a range of tactics of violence to erase migrant worker voices and invisibilize migrant worker bodies (see for instance Kaur et al., 2016; Yea, 2017).

Migrating from Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Malaysia, and China, low-wage migrant workers labor in precarious positions in Singapore, building the infrastructures of Singapore's neoliberal economy. Toiling in transient conditions without access to pathways of citizenship, without labor rights, and without the access to communication infrastructures for voicing the challenges to their health and well-being, low-wage migrant workers live in a climate of fear, amidst systemic threats to their employment, health, and well-being (Dutta, 2017a,b; Yea, 2017; Yea and Chok, 2018). The everyday struggles for migrant health in Singapore are constituted amidst a climate of authoritarian state management that produces worker precarity to facilitate capitalist extraction. Structural violence, reflected in the denial of the fundamental needs of everyday health and well-being, is constituted amidst the cultivated climate of fear and erasure (Dutta, 2017a,b).

The COVID-19 pandemic renders visible the deep inequalities entrenched in the political economy of Singapore, with the largest number of COVID-19 infections among low-wage male migrant workers. Singapore, celebrated as the “gold standard” and held up by World Health Organization (WHO) as a model response in the early part of the pandemic, emerged as the site of large-scale COVID-19 outbreaks in migrant worker dormitories. Why did a city-state paraded as an exemplar of efficient expertise-driven neoliberal management of the pandemic, replete with its methods of contact tracing, quarantining, and keeping borders open, turn into a site of large-scale pandemic outbreak, moving at the top of the chart of COVID-19 infections in Southeast Asia by early May? In this article, I apply the theoretical framework of the culture-centered approach (CCA) to argue that inherent in Singapore's model of authoritarian neoliberalism is the infrastructure of technocratic management that erases the voice of precarious migrant laborers. The management of migrant labor is carried out through repressive strategies of disciplining, and this constitutes the backdrop of the COVID-19 outbreaks in migrant worker dormitories in Singapore. Drawing on my ethnographic work with low-wage migrant workers in Singapore, I suggest that the initial control of the outbreak through technocratic techniques of generating efficiency exists in continuity with the systematic erasure of the voices of migrant workers and the vast power inequalities amidst which low-wage migrant workers live their lives. I explore the interplays between structural violence and communicative inequality amidst the outbreak in migrant worker dormitories based on my ethnographic fieldnotes, in-depth interviews, a digital ethnography, and a survey.

Culture-Centered Approach

The CCA locates health meanings at the intersections of culture, structure, and agency (Dutta, 2004a, 2008, 2017a,b; Dutta and Jamil, 2013). Culture reflects the dynamic interaction between shared meanings and contexts, drawing upon and shaping the shared values, beliefs and practices in everyday life. Structure taps into the patterns of distribution of social, material, political, and economic resources of health and well-being (Dutta and Basu, 2008; Sastry et al., 2019). Agency is the human capacity to make sense of and negotiate the everyday contexts of health and well-being (Dutta, 2004a, 2017a,b; Dutta and Jamil, 2013; Bates et al., 2019). Anchoring the meanings of COVID-19 constructed by low-wage migrant workers in Singapore amidst the interplays of culture, structure, and agency opens up the spaces of theorizing rooted in migrant worker voices, working in solidarity with these voices to co-create praxis (Dutta et al., 2017; Jamil and Kumar, 2020).

In the conceptual framework put for by the CCA, communicative inequalities (inequalities in the distribution of communicative resources for information and voice) are intricately intertwined with structural inequalities, or inequalities in the distribution of material resources (Dutta, 2004a, 2007, 2008). The erasure of the voices of low-wage migrant workers from discursive spaces is intertwined with the structural violence workers experience. Therefore, the work of co-creating infrastructures for voice is embedded in material inequalities, and simultaneously offers an anchor to transforming these material inequalities.

The interplays of communicative and structural inequalities constitute the inequalities in health outcomes (Newman et al., 2014; Dutta et al., 2017). These inequalities in health outcomes, produced by extreme neoliberal policies, are likely to be exacerbated in the context of COVID-19. Hegemonic health communication approaches erase these structural contexts of health, instead developing individualized behavior change solutions promoting changes in individual attitudes and beliefs. Even as structural determinants of health are offered lip service in hegemonic health communication interventions, the behavioral recommendations focus on the individual. Interventions addressing health disparities primarily take the forms of culturally sensitive campaigns incorporating relevant cultural characteristics into behavior change messages or technology-based solutions. Specifically in the context of COVID-19, hegemonic health communication solutions target individual behavior, locating the problem in the individual, placing the responsibility of mask wearing, social distancing, hand washing, eating healthy, and staying home on the individual2. The CCA inverts this individualized reductionism through the co-creation of communication infrastructures with community voices at the margins. The discursive registers put forth by the voices of those at the margins foreground the structural features of neoliberal societies as the sites of transformative organizing and social change.

Building on a growing line of existing research that connects health to the precarity of work in global processes of labor flow (Dutta and Jamil, 2013; Kaur et al., 2016; Dutta, 2017a,b; Yea, 2017), the CCA suggests that the structural contexts of immigrant health are rooted in the erasure of migrant voices. Voices of low-wage migrants at the margins of neoliberal economies foregrounds meanings amid these structures, suggesting strategies for health communication that responds to these overarching structures of health and migration. It seeks to co-create infrastructures of listening to the voices of migrant construction workers in Singapore, seeking to disrupt the ongoing forms of erasure that constitute the organizing of migrant spaces (Dutta, 2004a,b, 2008; Dutta and Jamil, 2013; Dutta and Kaur-Gill, 2018).

Neoliberal Singapore and Structures of Low-Wage Migration

Singapore, with its role as the frontier of transnational capital's cultivation of and investments into ever-expanding Asian markets, as well as the infrastructure of neoliberal pedagogies of the future (consider the powerful presence of Singapore elites as interlocutors and mediators in World Economic Forum conversations on elite responses), constitutes a key register of extreme neoliberalism. Singapore's extreme neoliberalism incorporates techniques of violence and disciplining into the authoritarian state as the organizing structure for capitalist accumulation. The model of state capitalism explicitly organizes the state not only as a “custodian of capital accumulation” (Tansel, 2017, p. 4), but also as a pivotal player in the processes of extraction and exploitation. The authoritarian state as the primary agent of “neoliberalizing violence” (Springer, 2015) incorporates into its structures mechanisms of surveilling, disciplining and policing the abandoned “other.” It thrives on the production and circulation of propaganda that props up its model of economic development, pitched as the “Singapore model” (see Dutta, 2018a,b; Dutta et al., 2019). Underlying the propaganda of the “Singapore model” is an entire infrastructure of communicative devices that project “hubs,” “knowledge centers,” “dialogues,” and “expos” that are continually at work, seeding, promoting, and circulating the model of free market economics, narrated in the language of Asian values (Dutta, 2018a,b, 2019a,b). The carefully crafted public relations infrastructure of Singapore continually manufactures the narrative of “from third world to first.” Singapore's communicative capital thrives on the erasure of the exploitation and extraction that constitute its global positioning as the frontiers of transnational capitalist expansion into Asia (Dutta, 2019a,b). This communicative capital, reflected in Singapore's positioning as a hub for the creative and digital industries accompanied by the numerous public relations campaigns run by the state positioning Singapore as the city of the futures, is sustained through the systematic deployment of techniques of disciplining that manage, surveil, and silence the poor and working classes.

The authoritarian techniques of control and discipline that form the backbone of Singapore's neoliberalism are packaged into the brand of “Asian values,” then sold as a destination solution to these othered elsewhere of Asia (Tan, 2012; Juego, 2018). The erasure of the exploitation of low-wage migrant workers from Bangladesh and India is necessary to crafting the seduction of the “Singapore model” as hyper-efficient governance for these backward Asia's. The seduction of the “Singapore model” is sold as a “smart city” imaginary of the future to these other Asia's, thus generating news sites of extraction of profiteering for Singapore-based corporations (consider for instance the market opportunities opened up for Singapore-based corporations in India's “Smart City” projects pursued aggressively). The narrative of lifting large parts of Asia's backward spaces out of poverty strategically obfuscates the poor working conditions, the absence of minimum wage, the lack of opportunities for collectivization, and the absence of worker rights for low-wage migrant workers in Singapore. The neoliberal narrative of the trickle-down effect works simultaneously through the inversion of materiality and the erasure of worker voices. The authoritarian strategies of controlling protest and organizing work hand-in-hand to erase opportunities for worker articulations of labor rights.

The narrative of the “Singapore model,” storying an account of a strong developmental state that actively fosters development through its strong interventions is manufactured as a seduction for urban development across Asia (Dutta, 2018a,b). The model promises a policy mix that combines authoritarian management with state-led development (Pow, 2014). The strong state-based interventionist model, evident in the state-run corporations and the climate of authoritarian repression of collective organizing form the architectures of Singapore's extreme neoliberalism. The model of “hybrid development” (Rahim and Barr, 2019) serving the frontiers of capitalist expansion strategically crafts an account of “Asian values” to render as Asian forms of repression and disciplining that serve the expansionary interests of transnational capital. The ideology of “Asian values” strategically manufactured, planted and circulated by Singapore's ruling elite, concocts a mixture of narratives of meritocracy, pragmatism, and communitarianism into brand Singapore that drives the nation state's political economy. In the latest iteration of techno-capitalist futures, the “Singapore model” punctuates the story of the “smart city,” with futuristic imaginaries of creative capital, digital participation, and sustainable technologies for growth (Kong, 2018; Kong and Woods, 2018). An array of policies of city making, projected as smart policies work together to craft this imaginary of futures. Underlying the mobility of the techno-futuristic appeal of the “Singapore model” lies the systemic exploitation of precarious workers that materializes the technologies of clean, urban planning. Voices of low-wage migrant workers are silenced with a legal framework that criminalizes migrant worker organizing, censors migrant worker protest, and strongly regulates migrant worker presence in spaces of public participation through technologies of surveillance and police control.

Migrant Health

Low-wage migrant workers working in the construction, shipping, building, and cleaning industries in Singapore, form the textures of global flow of labor amidst extreme neoliberal policies. Migrant workers negotiate their health amidst global structures of capitalist extraction (Dutta, 2017a,b). The theorizing of health of low-wage migrant workers in Singapore ought to be situated amidst its “smart city model” marketed globally as a model of labor extraction through techniques of authoritarian disciplining that enable capitalist expansion. That the material architecture of smart city Singapore is built on the extracted labor of low-wage migrant workers is communicatively erased, using the tools of “trickle down” narratives and erasing the bodies of low-wage migrant workers from Singapore's smart urbanisms. Low-wage migrant workers in Singapore often work in “dirty, dangerous, and difficult” jobs, supported on short-term work permits, without labor protections and without the pathways of mobility into citizenship (Baey and Yeoh, 2015; Bal, 2015).

Low-wage contract-based migrant workers in Singapore perform precarious work, work that has “limited social benefits and statutory entitlements, job insecurity, low wages, and high risks of ill health” (Vosko, 2006, p. 4). The everyday work experiences of low-wage migrant workers are constituted amidst vast imbalances in distribution of power, with the control over their short-term work permits held by the employer (Yea and Chok, 2018). Amidst restrictive migration laws that promote temporariness and preclude pathways of mobility into citizenship, complex, and interconnected webs of brokerage constitute the tenuous conditions of low-wage migrant labor in Singapore (Lindquist et al., 2012; Baey and Yeoh, 2015, 2018). Lewis et al. (2015) depict these conditions of low-wage migrant labor as “hyper precarious,” reflected in “deportability, risk of bodily injury coupled with restricted access to healthcare, and transactional relationships” (p. 593). Hyper precarious work is marked by the absence of protections, and a fundamental condition of “unfreedom” (Yea, 2017; Yea and Chok, 2018). The linkages of brokerage, materialized in the form of recruitment, training, and travel agencies, impose significant front-end investments on low-wage contract-based migrant workers, which are often secured by going into debt, selling the limited ancestral land, or selling household possessions The hyper-precarity of low-wage contract-based migrant work in Singapore is further exacerbated by the individualization of the risks on the worker, with the absence of systemic infrastructures for workers to address their labor-related needs, the absence of state-based infrastructures directly accessible to workers, and the absence of clear policy oversight that holds the employers, dormitories, and caterers accountable.

The systematic erasure of the voices of low-wage migrant workers is accompanied by communicative inversions, the turning-on-its-head of materiality through techniques of strategic communication (Dutta, 2016). For instance, the materiality of migrant worker precarity is inverted by communicative devices that project Singapore as the gateway for upward mobility for the dark-skinned masses of the Third World. This work of communicative inversion is propelled by a racist communicative architecture that needs the backwardness of neighboring Asia's (Bangladesh, India) to construct Singapore in the imagery of Whiteness. Low-wage migrant work is thus narrated as upward mobility, forming the rhetorical arsenal of trickle-down economics through migration that catalyzes economic mobility elsewhere in the Third World. In this ideology, the migration of low-wage migrant workers to Singapore as a hub of Asian capital uplifts individuals, households, communities, and nations that form Asia's other into the networks of mobility.

Method

This manuscript reports on two distinct phases of data gathering, nested within a broader ongoing culture-centered intervention seeking to co-create infrastructures for health and well-being among low-wage migrant workers in Singapore (Dutta, 2018a). Following an immersed 6 month ethnography with low-wage migrant workers in Singapore conducted in 2008, between 2012 and 2018, an advisory group of low-wage migrant workers that had been formed as part of the ongoing culture-centered intervention developed by the Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE) sought to co-create everyday solutions of health and well-being, resulting in a national-level health campaign, “Respect our rights” seeking to transform the unhealthy structures of migrant work (see https://www.facebook.com/Migrant-Workers-Rights-SG-1557463061204402/).

When the COVID-19 outbreaks emerged in migrant worker dormitories, the advisory group sought to co-create COVID-19-related health solutions addressing the outbreak in migrant worker dormitories. They shaped the design of the COVID-19-specific study, as well as the process of making sense of the emergent data. Given the longitudinal nature of the project, three separate human ethics approvals supported it. The latest round of data gathering reported here was deemed to be low-risk following university ethics procedures. Given the precarity of low-wage migrant workers amidst Singapore's authoritarian surveillance structures, multiple steps were taken to anonymize worker identity, including transcribing the interviews immediately, erasing the audio files immediately after transcription, and not attaching identifiers to narrative accounts.

The findings reported here draw on two phases of data gathering amidst COVID-19. In the first phase, the data were gathered from on an ongoing digital ethnography (87 h of participant observation) conducted in spaces where low-wage migrant workers participate online and 47 semi-structured interviews conducted with low-wage migrant workers between April 7, 2020 and April 30, 2020. The participant observation included making detailed notes of online interactions, coding issue-specific articulations, negotiations of power, as well as the strategies for communicative negotiations. The participants for the interviews were identified using snowball sampling, guided theoretically by the principle of co-creating the “margins of the margins” (Dutta, 2018a). The interviews were conducted in Bengali, mix of Bengali and English, or English, depending on the level of comfort and preference of the participant. Data analysis in the first phase was carried out through line-by-line coding of the 47 interviews, followed by the organizing of the codes into broader themes. The initial themes emergent from the analysis were shared with the advisory group, who made sense of the themes through their lived experiences amidst COVID-19. The advisory group determined the key findings to be reported based on the consideration of the immediate challenges they have been experiencing amidst COVID-193.

In the second phase, a survey was conducted. The advisory group of migrant workers, drawing upon the emergent themes in the interviews, co-constructed with the research team a survey exploring the challenges to health and well-being amidst COVID-19. This article incorporates descriptive statistics from the survey. The initial survey was pilot tested among 10 workers. Participants were recruited through snowball sampling, with the link to the survey circulated in networks of low-wage migrant workers. In addition, migrant workers were recruited through social networks and the survey was administered over phone. The sample (n = 101 usable responses, from 106 participants) comprises predominantly Bangladeshi migrant workers, with representation by a smaller number of Indian workers. The sample does not include Chinese workers. Workers from Bangladesh and India constitute some of the lowest rungs of low-wage migrant work in Singapore.

The phased three-pronged research approach combining digital ethnography, semi-structured interviews, and survey enabled validation, offering a framework for examining the convergence of the findings. Moreover, the longitudinal process of sense-making of the data conducted by the advisory group of migrant workers further strengthened the validity of the analysis. Throughout the process of making sense of the data, the advisory group members noted how their experiences with the challenges to health and well-being in the everyday contexts of life in Singapore pre-COVID-19 converged with the emergent challenges amidst COVID-19. Therefore, to further validate the findings, the data gathered from the participant interviews conducted in the context of COVID-19 were placed in conversation with 157 in-depth interviews that were conducted by CARE since 2012, anchored in the tenets of the CCA (although the narrative excerpts included here do not report from the 2012–2018 period). These earlier in-depth interviews, guided by a continually transforming advisory group, had identified the structural contexts of work and living that constitute the everyday challenges to health and well-being of low-wage migrant workers in Singapore. For instance, the challenges with housing and food as integral to the health and well-being of migrant workers.

Findings

This article specifically draws on findings that foreground the structural contexts of health, further exacerbated amidst COVID-19. The ethnography, interview, and survey data point to the structures of housing, the absence of sanitation infrastructures, and the experiences of food insecurity as the contexts within which health and well-being are negotiated. The structural violence that is exacerbated amidst COVID-19 is placed amidst symbolic violence, the absence of infrastructures of information and voice articulated by the low-wage migrant workers. These interactions between communicative and structural violence form the overarching infrastructures of poor health and well-being, within which low-wage migrant workers voice the everyday challenges to mental health amidst COVID-19.

Structures of Housing

The poor condition of housing is a key theme in the ongoing ethnographic work. In creating a framework for understanding the challenges to health and well-being, low-wage migrant workers had noted in the first round of advisory group meetings held by the CARE research team in 2013 that the cramped conditions within which they live their lives threaten their health and well-being, foregrounding the living conditions as an important anchor to worker health and well-being. This theme of poor housing conditions was narrated by participant 324, who noted “How can a worker be healthy when there are so many of us in one room? There is no space to breathe, and everyone is stacked together into the room.” For participant 67, “I just can't move around in the room.” Another participant suggests that the air circulation in the room is poor, “I feel I can't breathe. This is my biggest health challenge. There is a person on the bed above me.” Yet another participant noted, “The room leaves no space to stretch or even rest after a hard day at work. When I return home, I am tired. Then there are so many brothers all together. This makes me sick.” Another participant noted, “I can't breathe. The air is stale and there is smell in the room.” The participants in our research narrate the ways in which the overcrowding in the living arrangements turns into experiences of stress and anxiety. Notes a participant, “I have worked on so many buildings. Many of them are big hotels. But this is how we live. All crowded together in these rooms with nowhere to go.”

They also suggest that with many workers in a room, there are often conflicts, which further exacerbate the feelings of stress experienced by them. Notes participant 113, “the conflict is often about the space. There are so many challenges with space, about where to keep things, when to turn on the lights, when to speak with family. All of this has to be figured out.” Negotiating their work rhythms, participants suggest that their sleep patterns are affected because of different work schedules. This in turn significantly affects their health and well-being, and also contributes to accidents in the workplace. The participants in our research highlight ongoing challenges with privacy in the rooms. Notes a participant, “With so many people in the room, there is no privacy.” With 20 migrant workers in a room in many instances, participants note that they are unable to communicate on the phone, move freely in their rooms, and have a sense of peace. This lack of privacy results in conflicts among workers in the rooms, and adversely affects the mental health and well-being of workers. Noted a participant, “I can't sleep at night because some of the brothers in the room wake up early in the morning. This results in a sense of being tired all day.” Another participant voiced, “How can anyone rest when there are so many of us.” Another participant pointed out, “I have to go outside and walk around in the hallway if I want to talk to my wife. There are often money matters that we are discussing.” The sense of not having privacy, often with 20 workers in a room, adversely impacts the sense of health and well-being.

Amidst these everyday challenges to health and well-being constituted amidst the architecture of the rooms, participants point to the sense of feeling depressed, “I didn't think before coming here I will have to live like this. In (referring to home), we have open fields, and open air. When I came here and looked at how I have to live, I became sad.” Multiple participants refer to feelings of depression when discussing their living arrangements. This feeling of depression is constituted amidst articulations of not knowing how to change these conditions (more on this later).

Making sense of this condition of overcrowding, a participant observes, “The boss does not care. The dorm owner makes as much money from the worker as he can.” Although participants point to a wide range of living arrangements, for a large number of them, the usual living arrangement is in a dormitory, with between 15 and 20 workers in a room. For another participant, “The workers are put in like in a jail. There is no room to move.” Participants often wondered about the approval process for building these arrangements and what the regulatory guidelines were, “The answer for why, our dormitory authority, or dormitory approval authority only know, who give them the approval to arrange 20 person.” A participant pointed to absence of oversight, “Even the place where I am staying, some time they bring in even more workers.” These overcrowded arrangements affect the health and well-being of workers.

Housing and the Limits to Behavior Change

The concerns about over-crowded rooms becomes salient amidst the COVID-19 outbreaks in the dormitories housing the workers. The narratives locate the one-meter physical/social distancing policy amidst the crowded living conditions, suggesting that the recommendation to maintain one-meter distance does not make sense because of the very nature of worker housing. Noted one participant, “For me, I exactly don't know my room size, but I feel that 10 person also maximum in my room, but they keep 20 person.” Another noted, “They keep bringing in more workers into the room. There is no space to move even.” In the midst of the pandemic, participants point to workers being moved, often without clear communication, and often without addressing the crowded conditions. Referring specifically to the COVID-19 outbreak, a participant noted “How can a worker follow 1 m distance? The room has 20 people.” Here's another excerpt from an interview, “Now, there are many of us in the room all day every day. Because I cannot go outside, I am staying inside the room. Everyone is doing this. So compared to regular times, now there are even more workers in the room throughout the day.” Another participant noted, “They are saying you need to do those things, washing hand and not go outside together. How can we follow one meter distance when there are so many workers in a room.”

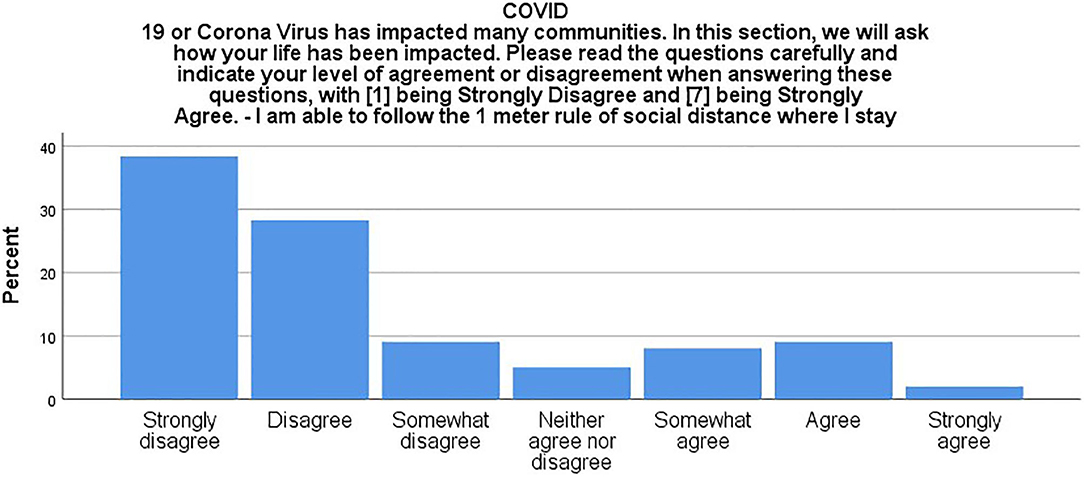

This structural limitation on following the one-meter social/physical distancing guideline is reiterated in the survey. For a large majority of low-wage migrant workers in Singapore, self-reported practice of one-meter distance in the dorms is unlikely within the housing infrastructures. In response to the statement, “I am able to follow one meter rule of social distance where I stay,” 38.4% “strongly disagreed,” 28.3% “disagreed,” and 9.1% “somewhat disagreed” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of participants reporting their ability to follow one meter social distance rule.

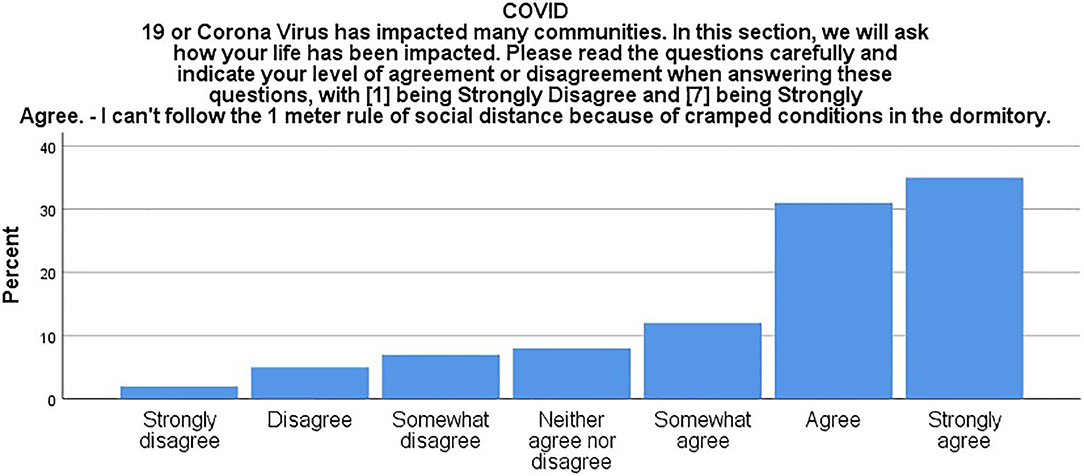

Most of the workers attributed this inability to follow the one-meter rule to the cramped conditions in the dormitory. In response to the statement, “I can't follow the one-meter rule of social distance because of cramped conditions in the dormitory,” 12% “somewhat agreed,” 31% “agreed,” and 35% “strongly agreed” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of participants reporting inability to follow the one meter rule because of cramped conditions.

Structures of Sanitation

Inadequate sanitation has consistently emerged as a theme in our ethnographic solidarities with low-wage migrant workers in Singapore. In advisory group meetings, workers have often narrated the poor toilet facilities in their spaces of living as well as at work sites across Singapore. Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak in dormitories, worker voices foregrounded the ways in which the unclean dormitory conditions posed risks to their health and well-being.

Unclean Dormitory Arrangements

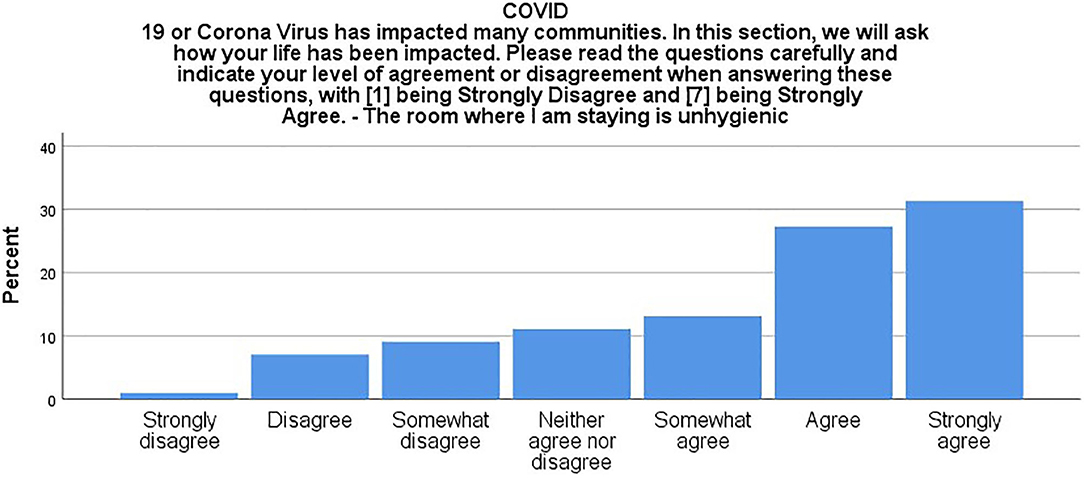

Tied to the concerns about overcrowding are the articulations of unclean dormitory arrangements. The participants note that overcrowding often leads to unclean dormitory arrangements, with the usage increasing because of the number of workers that are staying in their rooms. Throughout the period of ethnographic fieldwork, I received photos and videos taken by workers of the unclean rooms. For a number of them, the cleanliness of the dormitory is related to the design of the room and the wings, with the double bed system contributing to challenges with cleanliness. Without adequate space to put up their luggage and clothes, participants suggest that clothes and laundry are often left lying around. While walking through his room with a mobile camera, noted a participant, “How can the room be clean? How can the workers keep things clean when we are staying like this, you tell me.” The survey further points to this concern about the unclean dormitory conditions. To the statement “The room where I am staying is unhygienic,” 13.1% participants indicated they “somewhat agreed,” 27.3% “agreed,” and 31.3% “strongly agreed” (see Figure 3).

Lack of Toilet Facilities

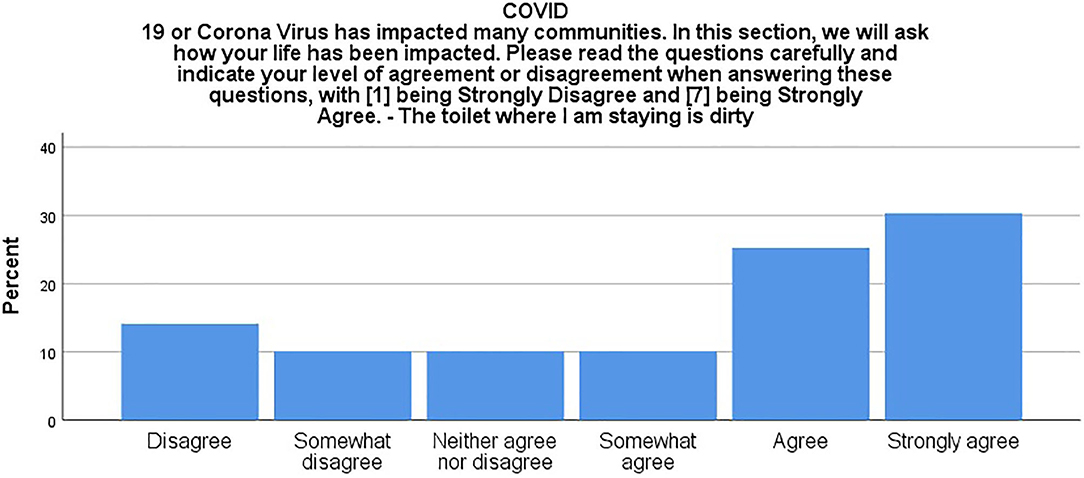

The participants in our research consistently note the absence of adequate toilet facilities in the dorms. Participants often pointed out that for a block of five rooms, with 20 workers in a room, there are five toilets and five shower spaces. These infrastructures are not adequate as there are often long queues, and the facilities remain unclean. One participant noted, “Toilet and shower facility is not enough, and there is always a long line. This is the problem in the morning. I have to wake up very early at 4 a.m. to use the toilet, and then I am tired the whole day.” Not having enough toilet translates into difficulties at the workplace, including difficulties in following workplace instructions and accidents at the workplace. This is noted by a participant, “How can a worker do the work in the site when he is tired because he wakes up very early in the morning to use the toilet?” This shortage of toilet facilities at places of accommodation is further exacerbated often by the lack of adequate toilet facilities and water at the workplace. Amidst COVID-19, participants express their anxiety about the toilets not being cleaned adequately amidst COVID-19. In the survey, in response to the statement, “The toilet where I am staying is dirty,” 10.1% respondents “somewhat agree,” 25.3% respondents “agree” and 30.3% respondents “strongly agree” (see Figure 4).

Lack of Soap and Water

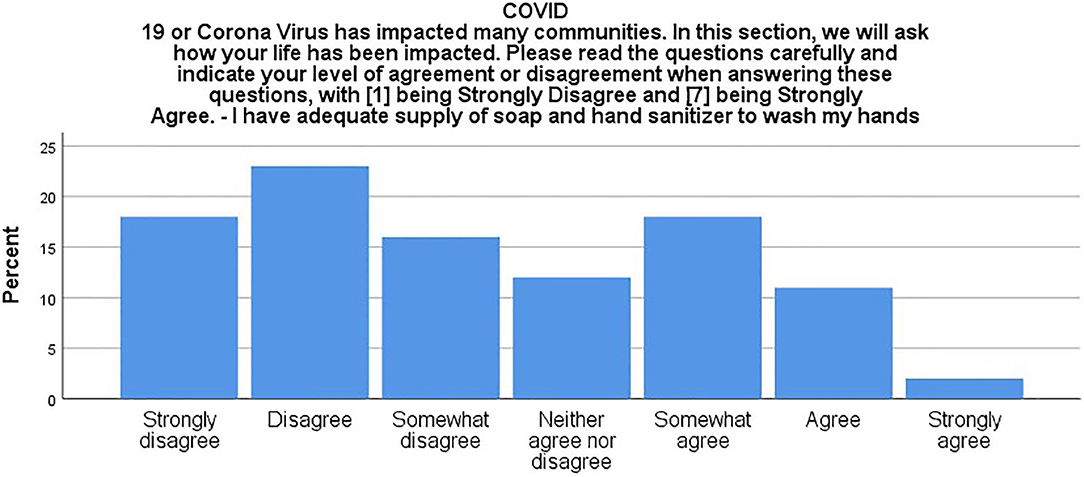

Participants in the interviews shared that they are unable to wash their hands with soap regularly because of the limited supplies of soap and water. Noted a participant, “There is often not enough water after everyone uses water.” In the articulations of another participant, “There is no soap. I have not received my salary yet. So I can't buy soap. The brothers (referring to NGO workers) came once and they have not returned yet.” When asked about the availability of soap and sanitizer in the survey, 18% of the participants indicated that they “strongly disagreed” with the statement, “I have adequate supply of soap and hand sanitizer to wash my hands.” Moreover, 23% stated that they “disagreed,” 16% “somewhat disagreed,” 12% “neither agreed nor disagreed,” 18% “somewhat agreed,” 11% “agreed,” and 2% “strongly agreed” (see Figure 5).

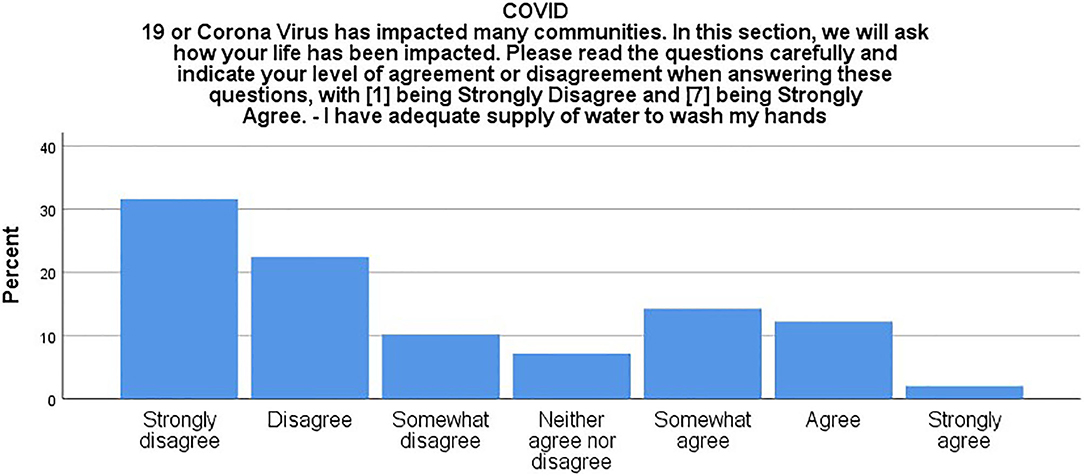

Similarly, 31.6% of the participants indicated that they “strongly disagreed” with the statement “I have adequate supply of water to wash my hands.” Moreover, 22.4% stated that they “disagreed,” 10.2% “somewhat disagreed,” 7.1% “neither agreed nor disagreed,” 14.3% “somewhat agreed,” 12.2% “agreed,” and 2% “strongly agreed” (see Figure 6).

Food Insecurity

The participants in our research have consistently noted the absence of adequate and quality food. Our advisory groups have often highlighted the lack of quality food since 2012, guiding a research study that was undertaken by CARE to examine the experiences of food insecurity among low-wage male migrant workers in Singapore, and resulting in the “Respect our food rights” campaign (Dutta, 2017a,b). For low-wage migrant workers (predominantly Bangladeshi workers that we have worked with), the lack of access to decent food is an everyday reality of life, emergent in worker narratives as a fundamental challenge to worker health and well-being. Workers struggle with the quality of food, often reporting that they are provided with low-quality food. This is exacerbated in the midst of COVID-19. During the lock-down, workers, including those who usually cooked their own food (majority of the workers we have interviewed between 2012 and 2018 noted that they had to rely on catered food of poor quality), were supplied food by caterers. The participants noted food is often stale, has been spoilt, and is of poor quality. They pointed out that food is often oily, with poor nutrition quality.

One participant noted, “The food in the middle of COVID-19 is really bad. How can I have a strong immune system to fight the virus if this is the food I am given.” In the voice of another participant, “The food is not what we eat. It is sour, and gives me heartburn. I have been sick with stomach upset two times already in the middle of the pandemic.” For a number of participants, throwing away or skip a meal was the way to avoid falling sick because of the poor quality of food, “I don't even eat the catering food. The breakfast food is really bad, very sour, and it makes me sick. So usually during the whole day, I will not have eaten anything. How can I survive like this I don't know. This makes me very sad, and I have been spending days going hungry.”

In the accounts offered by participants, the price of catered food had gone up amidst the pandemic, with workers having to pay larger sums of money from their meager wages. Here's a depiction of the rise in the amount of deduction for catered food, “only eating catering. Also very poor food. Deduct per month $140, which is $20 more also, already can said cruelty.” For this participant and many others, the rise in the amount of money deducted for the food catering amidst the pandemic was juxtaposed in the backdrop of uncertainty about the payment of wage. This rise in the deduction amount for catering food amidst COVID-19 was reiterated by a number of participants. Moreover, our advisory group members note that in spite of the media attention to food and the stories about improvement in the quality of food, they are continuing to be served poor quality food. Noted a participant, “You see on the government websites, the minister says that the food is now improved. But please ask a worker. What will a worker say if he is not scared? I am sending you some pictures (he send me images of the poor quality food over WhatsApp). This is how the food is. How can a worker survive on this in the middle of COVID-19?” Juxtapose these accounts offered by the low-wage migrant workers in the backdrop of the recommendations for healthy eating made by the Health Promotion Board (HPB) in the midst of the pandemic5. The structural contexts of poor food served by caterers disrupts the individualistic behavior change recommendations for healthy practices amidst COVID-19 put forth by the state.

Erasure of Voice

“Where to even go to talk about these issues? Who will listen to us?” notes one participant. Amidst the food challenges of low-wage migrant construction workers brought up by activists, social media in Singapore has emerged as a site of conversations on the working and living conditions of low-wage migrant workers. Referring to these conversations, voices a participant, “I just want decent food. Give me my dignity. There are so many Singaporeans that say on Facebook that workers shouldn't complain because we are lucky to be here.” Shares another participant, “I can't really talk about any of these problems. If my boss comes to know, he will take me out of the job and send me back.” Yet another participant shares, “I am scared to say anything. Saying anything will get me into trouble. My work pass will be taken away.” The erasure of spaces for voicing their everyday challenges to health and well-being is situated amidst the tremendous power differentials that constitute low-wage migrant labor in Singapore.

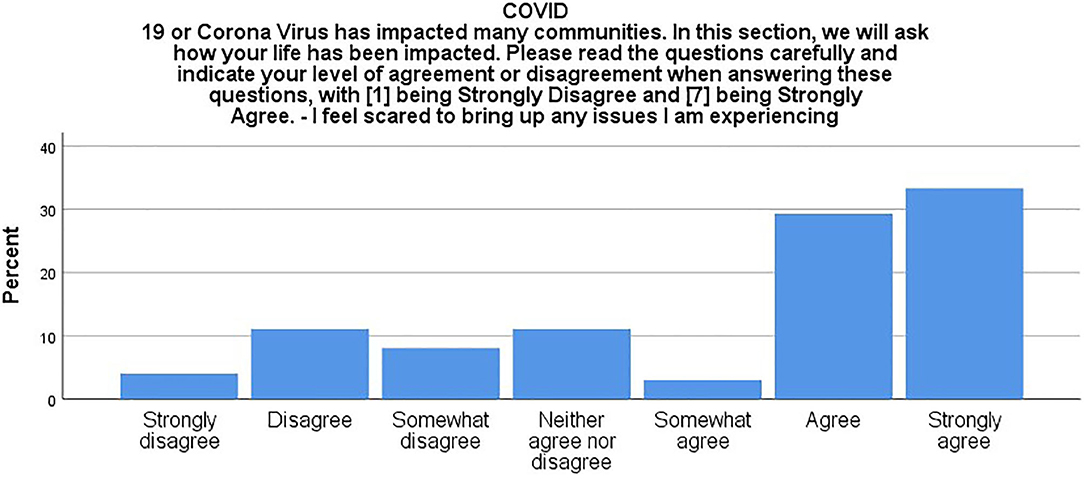

In the backdrop of the strong structural barriers and the lack of certainty regarding the payment of wages/salaries, 33.3% of the participants indicated that they “strongly agreed” with the statement “I feel scared to bring up any issues I am experiencing.” Moreover, 29.3% stated that they “agreed,” 3% “somewhat agreed,” 11.1% “neither agreed nor disagreed,” 8.1% “somewhat disagreed,” 11.1% “disagreed,” and 4% “strongly disagreed” (see Figure 7).

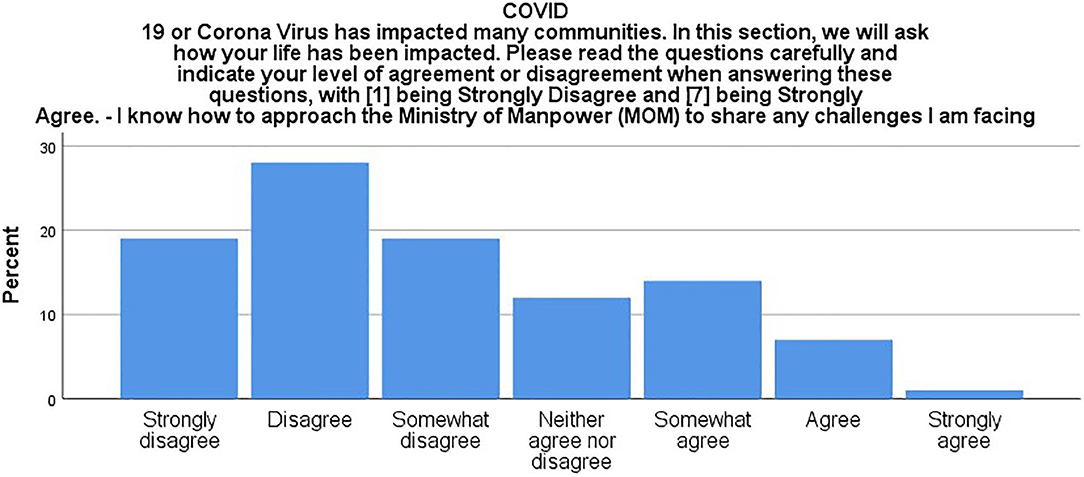

Participants reported their knowledge of how to approach the Ministry of Manpower to share any challenges they face. In response to the statement, “I know how to approach the Ministry of Manpower to share any challenges I am facing,” 19% “strongly disagreed,” 28% “disagreed,” and 19% “somewhat disagreed” while 14% “somewhat agreed” (see Figure 8).

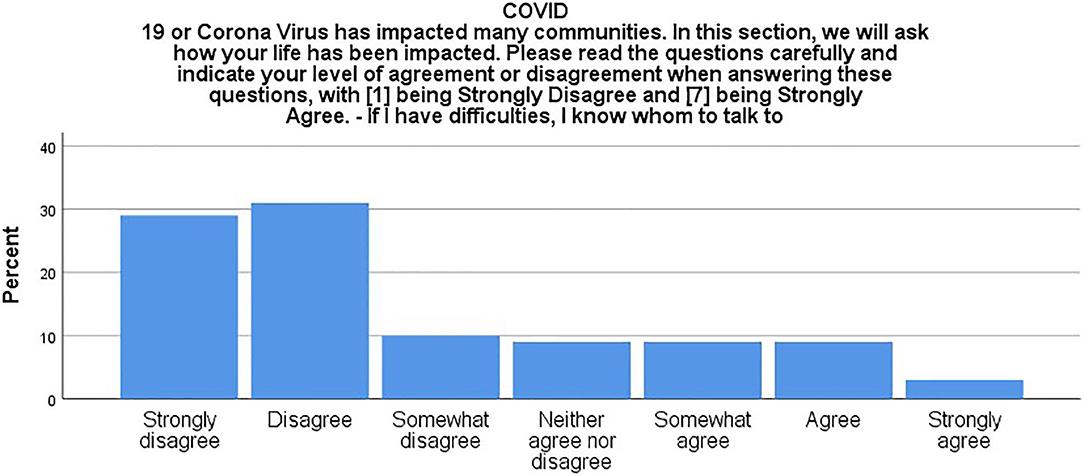

In response to the statement, “If I have difficulties, I know whom to talk to” 29% “strongly disagreed,” 31% “disagreed,” and 10% “somewhat disagreed” while 9% “somewhat agreed” and 9% “agreed” (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Distribution of participants reporting knowledge of whom to talk to when experiencing difficulties.

Mental Health

The participants share ongoing challenges to mental health and well-being, constituted by anxieties related to contracting COVID-19, anxieties about the inability to practice social distancing because of the crowded living arrangements and unclean toilets, anxieties about being fired or deported if they were to speak out, anxieties related to payment, and worries about their families back home. Centered in our conversations is the ongoing worry about not being able to support their families back home financially as well as a deep sense of fear over their future. For many participants, past and ongoing challenges with getting paid their salary constitute the sense of sadness they express, tied to their identities and roles as providers for their families. A participant expresses this: “I am here with all of this pain so my family can be taken care of. When my family is struggling because I can't take care of them, how can I be at peace?” This ongoing worry about the payment of salary is situated in the backdrop of state assurances of payment. One participant shares: “I don't trust anyone. I don't trust any Facebook video [referring to a message from the Minister of Manpower].” Another participant shared that he had been complaining about the non-payment of wages, and this resulted in him being fired by his employer amidst the lockdown. He shares, “the employer sent the termination letter. I was making posts on Facebook about the salary not being paid. Even if a worker speaks of what is rightfully his [referring to the salary], he can get fired.” Not having a voice, the overarching sense of anxiety, and various forms of disciplining the workers are subjected to result in the everyday challenges to mental health amidst COVID-19. Shares a participant, “I am scared. I worry I will not be able to see my family. I am scared I will not be able to send money home. Last month, I did not get the salary. Now, I am worried what will happen if I am infected.” Many workers in the digital spaces (such as Facebook groups run by workers) shared their worries about the non-payment of salary. In spite of the state's assurance about payment, workers shared that they worried whether the payment would actually reach them. This sense of worry about the payment of the salary is evident throughout the interviews. Noted a participant, “I haven't been able to send money home for 2 months. My family back home is really struggling. My mother said to me the other day when I spoke with her, she doesn't know what she will feed my family. I think about this and cry.”

In a Facebook group created and hosted by low-wage migrant workers, anxieties about infections are expressed amidst the fear of being separated from families at home. Many posts refer to the prison-like conditions of the dorm rooms. In a post, a participant points out that he feels depressed, being imprisoned with 15 other workers in a room and worried about the likelihood of infection because of the cramped condition in the rooms.

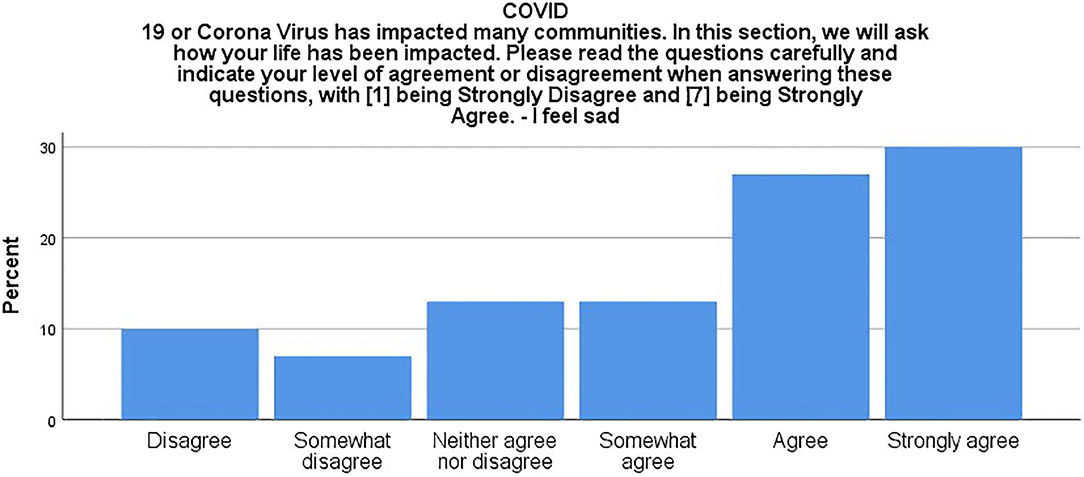

Another participant voices, “This room where I am staying, I only see the walls and stay inside. I don't know what is happening around me. We are moved from room to room and new people keep coming. I don't know what is happening in the dormitory and why the movement of the workers. This makes me worry.” Not having access to information about the steps being taken by the dormitory and the reasons behind the movement of workers from room to room emerge as challenges to mental health. Notes a participant, “I am scared. This corona virus, one brother in the room was infected. So I am scared. No one really explains anything. A few of us have been moved from one room to another. I am very scared.” This feeling of being scared is tied to the feeling of sadness many participants express. One participant shares: “I cry whenever I see my wife on the mobile. I don't know if I will see the children again, what will happen. With so many people (referring to the room), I am scared I will become infected. Worrying about it, I sometimes cry.” In response to the statement, “I feel sad,” 13% “somewhat agreed,” 27% “agreed,” and 30% “strongly agreed” (see Figure 10).

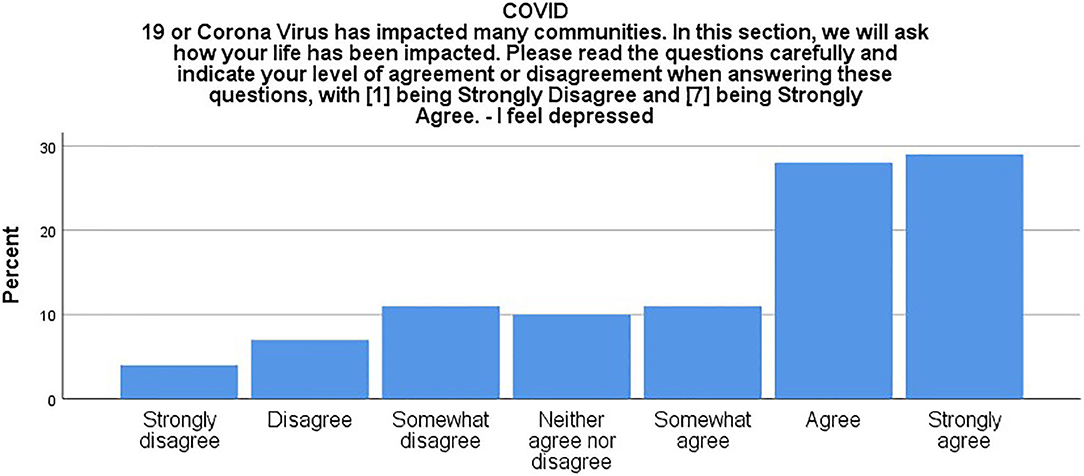

In response to the statement, “I feel depressed,” 11% “somewhat agreed,” 28% “agreed,” and 29% “strongly agreed” (see Figure 11).

Juxtapose these articulations of structurally constituted everyday experiences of health in the backdrop of the state's SG United campaign with recommendations of individual behaviors to upkeep mental health and well-being6. The individualized, behaviorally directed narrative of self-help propelled by the state is ruptured through the accounts of structural and communicative violence expressed by the low-wage migrant workers.

Discussion

This article, anchored in the CCA attends to the ongoing erasure of low-wage migrant workers in Singapore, amidst the active work of depoliticizing the exploitation of low-wage migrant workers and propping up the individualizing ideology of altruism. The meanings of health co-constructed by the low-wage migrant workers amidst the COVID-19 outbreak in dormitories housing them foregrounds the interplays of culture, structure, and agency, juxtaposed in the backdrop of the hegemonic ideology of service delivery that constitutes the state-civil society nexus. Activists pointing to the communicative erasures of earlier accounts documenting the poor housing and food conditions have been attacked in public and digital media discourses, supported by hegemonic structures (see for instance the targeted attack on the activist Kokila Annamalai)7. Salient amid the COVID-19 outbreaks in the dormitories, the instrument of Prevention of Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) created by the state to supposedly regulate “fake news” has been rhetorically mobilized8. This then serves as the backdrop of attacks on activists pointing to ongoing challenges with food experienced by low-wage migrant workers. Similarly, civil society organizations that have publicly interrogated state policies related to migration face a wide range of challenges amidst their COVID-19 responses. The authoritarian impulse of extreme neoliberalism seeds and circulates the rhetoric of the “anti-national” to suppress dissenting voices, thus legitimizing techniques of disciplining as necessary responses of good governance (Bruff and Tansel, 2019). Extreme neoliberalism sustains the free market ideology as an organizing framework even as its narrative has been thoroughly disrupted by the everyday empirical accounts of those struggling with its violent effects at the margins. As an extreme form of governmentality, it performs layers of communicative inversions amid techniques of disciplining and deployment of “communicative inversions” through state-controlled media infrastructures to project its failures as excellence in governmentality.

Constituted amidst these strategies of calibrating authoritarian control are the experience of communicative violence expressed by the low-wage migrant workers in Singapore, not knowing whom to go to raise their complaints, frightened to raise complaints because of the precarity of their work, and often living amidst structurally constituted communicative gaps. These forms of communicative violence are situated amidst structural violence that is magnified by the trajectories of COVID-19, and that forms the hegemonic organizing of “unfree labor” in Singapore (see Yea and Chok, 2018). Communicative inequality, inequality in distribution of information and voice infrastructures, is intricately tied to the material inequalities experienced by low-wage migrant workers (Dutta, 2008). The violence of extreme neoliberalism is worked into the various forms of disciplining that work actively to silence the voices of workers (Springer, 2012, 2015). The various forms of disciplining the workers experience, from being surveilled to being terminated for speaking up work together to perpetuate a fundamental form of violence ingrained in fear.

The health of low-wage migrant workers amidst the COVID-19 outbreaks attends to the interplays of authoritarian labor management and policy implementation failures that constitute the extreme neoliberal policies of Singapore. Paradoxically, the challenges to the health and well-being of low-wage migrant workers in Singapore exists alongside the claims to technocratic efficient management of the pandemic through tools of contact tracing and quarantining celebrated by global organizations such as the WHO and the World Economic Forum (WEF)9. The very technologies of authoritarian control that work on one hand in legitimizing efficient pandemic management while upholding the neoliberal ideology of “open borders” also have historically rendered invisible the structural violence within which low-wage migrant workers negotiate their lives through disciplining and control. The pandemic outbreak in low-wage migrant worker dormitories makes visible these poor conditions of health, work, and well-being (Dutta, 2020a,b). What this article demonstrates is that the everyday threats to health and well-being that are routinized into the routine management of low-wage migrant workers in Singapore are exacerbated by the pandemic. Inherent in the state's official narrative that articulates the impossibility of anticipating the outbreak is its systematic efforts of individualizing behavior and unseeing low-wage migrant workers in discursive spaces10. Responding to the outbreaks in the dormitories housing low-wage migrant workers, the state's reporting framework separates the migrant worker infections from the general population (Han, 2020). This framework of differentiation underlies a racist ideology that is also reflected in the state's spatial management of low-wage migrant workers, placing them on the invisible outskirts of the “smart city,” marking their bodies as targets of neoliberal management regimes, and targeting them through techniques of disciplining11.

Amidst their anxieties about the structural constraints that limit their ability to practice preventive behaviors, the low-wage migrant workers who participated in this study narrate accounts of everyday erasure. This erasure is constituted amid strict laws that prevent migrant worker organizing and silence the voices of migrant workers, the power over work and temporary visas held by employers, and the lack of structures of articulation. A political economy of mediation fosters communicative inequality (Dutta, 2016), with migrant workers living in fear amidst the temporariness of their migrant status and without the access to infrastructures for voicing their everyday challenges with poor working conditions, poor housing, poor food, and poor transportation. These structural features of work and livelihood constitute the crowded living conditions that shape the spread of COVID-19 among low-wage migrant workers in Singapore. The structural violence experienced by low-wage migrant workers in Singapore is situated amidst policies of surveillance and policing that mark migrant workers to be controlled. Paradoxically then, even as structural resources for health and well-being have been largely absent, various technologies of surveillance and containment have been put into place targeting the low-wage migrant worker. This coupling of technologies of surveillance and the absence of the fundamental structures of health depicts a racist-neoliberal ideology that sees the low-wage migrant worker as a disposable body in the circuits of accumulation of primitive capital. The specific context of extreme neoliberalism in Singapore and its failures further renders visible the failure of the behavior change paradigm of health communication that systematically erases structures while simultaneously putting forth recommendations for individual behavior change such as staying home, maintaining physical distance, washing hands, and wearing masks. The zeitgeist of the neoliberal behavior change framework, working to promote individualized responses that simultaneously erase questions of structural transformation, is confronted with its failures in Singapore and elsewhere across the globe. This suggests the urgency of radically transforming health communication, moving beyond its occasional lip service to structures under the hegemonic narrative of addressing health disparities while keeping the neoliberal structures intact, to revolutionary politics co-constructed in solidarity with the working classes locally, nationally, and globally, urgently building communicative registers for working class solidarity in disrupting and dismantling neoliberalism, and simultaneously building socialist political economies of health and well-being.

The essay wraps up by theorizing the work of co-creating communicative equality by building democratic infrastructures for migrant voices, which emerge as vital resources in addressing the pandemic, and offer the registers for post-pandemic transformations of politics, economics, and social organizing. Some of the key findings that are presented in this manuscript were earlier presented in the form of white papers designed to generate conversations in Singapore, having contributed to media advocacy driven by the advisory group (Dutta, 2020a,b). Drawing on the key tenets of the CCA, these conversations, driven by low-way migrant workers, sought to create registers for structural transformation. The erasure of voice, the absence of information infrastructures, and the absence of infrastructures for voice constitute the context of hyper-precarity of migrant work. The “interplay of neoliberal labor markets and highly restrictive immigration regimes” (Lewis et al., 2015) that depict hyper-precarity of low-wage migrant work in Singapore is rooted in communicative violence, the strategic erasure of communicative infrastructures for migrant worker voices. This communicative violence forms the “smart city” infrastructure of Singapore, deploying a wide array of strategies of erasure to render invisible the pain and poor health experienced by low-wage migrant workers. The erasure of the voices of low-wage migrant workers is a vital tool in legitimizing. Singapore's extreme neoliberalism, upholding its narrative of smart governance through projections of technology, participation, and sustainability. Communicative violence is a salient organizing feature of extreme neoliberalism. This communicative violence materializes in an overarching sense of fear and feelings of depression expressed by the workers, situated amidst fear of facing consequences of losing job or being deported if they speak up about the challenges being experienced (as evidenced in the findings, workers offer accounts of losing jobs for speaking up/out). Beyond the health challenges of COVID-19 infection, the participant observations, interviews and survey point to the challenges with mental health experienced by the low-wage migrant workers. These conditions of poor mental health make visible a vital site of health negotiation at the margins of extreme neoliberal societies amidst the pandemic.

Finally, the narratives offered by low-wage migrant workers foreground the structural violence that constitutes the infrastructure of preventive behaviors related to COVID-19. The everyday practices of recommended behaviors such as maintaining 1-meter physical distance and regularly washing hands with soap and water are situated amidst the infrastructures of poor housing, poor sanitation, limited supply of water, and lack of cleaning resources.

Moreover, the behavioral recommendation mandating the workers to stay in their rooms to prevent the spread of COVID-19 constitutes the paradox of over-crowded rooms that are rife with opportunities for the virus to transmit. Contrast the reality of poor, over-crowded housing with the cultural-behavioral hegemonic accounts of workers crowding in groups. The structural violence of poor housing, poor sanitation, and poor food that forms the everyday context of health of low-wage migrant workers is exacerbated by the pandemic, magnifying the effects on worker health and well-being. What the COVID-19 outbreak in migrant worker dormitories makes visible is the limit of the “Singapore model” as an exemplar of extreme neoliberalism in public health response, with gross inequalities normalized into its health and care infrastructures. The voices of the participants point to the lack of access to healthcare in the everyday contexts of health, the card-based security system used at the gates, and the lack of adequate conditions of housing as the reasons for the accelerated spread of the pandemic among low-wage migrant workers. The recognition of deeply unequal structures as the sites of the epidemic offer transformative registers for justice, communicative equality, and worker organizing, centering care as an organizing narrative for structural transformation. Note here that amidst the extensive global media coverage that documented the failures of Singapore's COVID-19 response and highlighted the poor treatment of low-wage migrant workers, the state responded with policy proposals for improving the housing conditions for the workers. However, any such response, in the absence of communicative equality and communicative justice, is episodic, performative, and not held accountable. In the absence of infrastructures for democracy, there are no existing democratic mechanisms to hold the ruling People's Action Party (PAP) accountable or actually measuring its effectiveness in delivering the policy proposals (Dutta, 2018b; Thompson, 2019). This is the inherent paradox of extreme neoliberalism, that its seductions of accounting to prop up the neoliberal structure exist alongside the absolute lack of infrastructures of accountability that exist outside of the purviews of the hegemonic PAP. Moreover, the authoritarian techniques of erasure that already erase voices of dissent perform violent erasures of migrant worker voices, who are left without access to structures of claims-making into the state. As reflected in the pandemic electoral conversations, the plight of the low-wage migrant workers which constituted the fundamental failure of the neoliberal state, are once again entirely erased from the conversation, missing from the articulations and debates. Even the opposition parties largely erase the everyday struggles and plight of low-wage migrant workers from the discursive space (there are some exceptions, such as the Singapore Democratic Party's platform that calls for a minimum wage framework for all workers and the SDP politician-public health expert Paul Ananth Tambyah who has highlighted consistently the public health failures in addressing the health of low-wage migrant workers). Culture-centered advocacy imagines an actual politics of resistance, fundamentally suggesting strategies for dismantling extreme neoliberalism by foregrounding an ethic of voice, solidarity and justice rooted in communicative equality. The ability to craft alliances between the essential rights of Singaporeans workers and migrant workers lies at the heart of building socially just futures (Dutta and Zapata, 2018; Falnikar et al., 2019).

Given the sense of anxiety expressed by the participants, this manuscript does not disclose the locations of the various living arrangements or compare the lived experiences of workers across the different forms of arrangements to protect the confidentiality of the participants. Also, the manuscript specifically reports on the key emergent themes that were of salience to the advisory group, suggesting that other issues related to the pandemic are not included here. For instance, although mask wearing is a key part of the pandemic response and did appear in the interviews, the advisory group noted that they largely had access to masks in the dormitories as well as at workplaces12. The excerpts from the interviews are truncated to protect the identity of the participants. Given the snowball method of recruitment for the survey by circulating the survey link in the second phase of the study, quality control is difficult. However, a large majority of the data gathering took place over the phone after making initial contact over Facebook messenger, Telegram, or WhatsApp, enabling verification. When the analysis was run with the phone-only sample, the same patterns were retained for the reported variables. Also, the current report of phase two of the study is based on a relatively small sample size. However, the triangulation of the survey data with the in-depth interviews and participant observations strengthens the validity of the study. This study demonstrates the robust data gathering infrastructures of the CCA in place amidst a crisis, anchored in an already existing sustained academic-community partnership in the form of an engaged advisory group of community members, advocates, and researchers involved on an ongoing basis in developing research frameworks and solutions for addressing the challenges to migrant worker health. As noted earlier, the emergent findings formed the basis of two white papers that served as registers for health advocacy amidst COVID-19 (Dutta, 2020a,b), leading to widespread local and international media coverage attending to the failures of the Singapore pandemic-response framework. Also, given the challenges with catered food voiced by the workers amidst the pandemic, the existing digital campaign infrastructure of “Respect our Rights” was utilized to disseminate already existing campaign messages on the quality of food, putting forth specific infrastructure-based demands that have been voiced by the workers on an ongoing basis (https://www.facebook.com/Migrant-Workers-Rights-SG-1557463061204402/). The CCA offers a register for both theoretically anchoring migrant health in transformative imaginaries and in co-creating an actual politics of structural transformation at the margins by seeding communicative infrastructures for voices of the margins.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because confidentiality of the participants need to be maintained. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bS5qLmR1dHRhQG1hc3NleS5hYy5ueg==.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Low Risk Human Ethics, Massey University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

MD has designed the study, conducted the fieldwork, analyzed the data, and wrote this report.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared co-authorships with the author.

Footnotes

1. ^Singapore is consistently ranked as one of the best places to do business by the World Bank's Doing Business Report. Simultaneously, consider the ranking of Singapore toward the bottom in the Oxfam Commitment to reducing inequality report. As a destination for transnational capital, Singapore continually works on the production of a disciplined workforce, low public sector spending, and low corporate taxes. Since the 1980s, Singapore's public sector spending has continually declined (Low, 2014). The state's expenditures on healthcare and social services are among the lowest in developed economies globally (Rahim and Barr, 2019).

2. ^Consider for instance the campaign run by the World Health Organization (WHO), #HealthyAtHome, with recommendations of preventive behaviors, putting forth and circulating the hegemony of behavior change (https://www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome?gclid$=$EAIaIQobChMIheHjP6M6gIVliQrCh2djwWDEAAYASAAEgJBfDBwE).

3. ^The findings reported in this manuscript formed the basis of two white papers reported by CARE, seeking to intervene into the COVID-19 state response. They were extensively covered in national and global media (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/singapore-million-migrant-workers-suffer- as-covid-19-surges-back), drawing attention to the poor living conditions experienced by low-wage migrant workers in Singapore. These findings along with advocacy work carried out by activists fostered a public opinion climate amidst which the state introduced fundamental transformations to the housing arrangements for low-wage migrant workers in Singapore (https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/new-dorms-better-standards-be-built-100000-foreign-workers-coming-years-lawrence-wong?fbclid$=$IwAR3T8JWaNW-~Vu33KBdnG71UrxHB85oVWeCC6InRgKfvd29LAdQBZg2EKmQA).

4. ^In this project, participants felt that their identities needed to be protected as they were voicing aspects of their livelihood that potentially could pose challenges to the tenability of their employment, work permit, and safety in Singapore. The co-constructive process with the advisory group resulted in.

5. ^The Health Promotion Board recommendations for coping with COVID-19, folded into the “Stay well” campaign, under the umbrella of the SG clean and SG United campaigns, encourage the target audience to eat healthy while in the lockdown (https://www.healthhub.sg/programmes/170/StayWell). The recommendations reflect the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for healthy eating during the lockdown (https://www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat- coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome—healthy-diet).

6. ^The “Stay well” campaign discussed earlier encourages the target audience to stay positive, suggesting guided imagery, mindfulness, progressive relaxation, and deep breathing (https://www.healthhub.sg/programmes/170/StayWell).

7. ^In the opinion piece published in The Online Citizen, the Singapore human rights activist Jolovan Wham outlines the ideology of authoritarian repression that targets activists, https://www.onlinecitizenasia.com/2020/05/04/advocacy-activist-harassment-and-solidarity/?fbclid$=$IwAR2-lHw-8z3pKy8ffHKaoVeWuc1KjdH2K6_t-IBa25n6yAvJYG6awR0le8s.

8. ^POFMA directive has been ordered to activists for making claims about worker payments (see https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/foreign-workers-dorms-pofma-alex-tan-singapore-states-times-12614908); POFMA has been referred to by the Minister of Home Affairs in relationship to the images of poor food circulating on social media (https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/some-people-spreading-fake-news-about-foreign-worker-dorms-to-incite-violence-shanmugam).

9. ^An entire infrastructure of think tanks, pundits, experts, and journalists are mobilized economically and politically to circulate the “Singapore model” as a miracle, as an exemplar of “exceptional political leadership.” Consider for instance, the ongoing work performed by the journalist Fareed Zakaria in holding up Singapore as a model of efficient governance driven by exceptional leadership (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hVUEoFyokqg).

10. ^Consider the claim that the outbreaks are connected to communal living of migrant workers, suggesting cultural-behavioral roots of the infections (https://www.cnbc.com/video/2020/05/06/coronavirus-singapore-minister-on-migrant-dormitories-during-outbreak.html).

11. ^In the backdrop of what is termed by the official state narrative as the “Little India riot” (Kaur, Tan, and Dutta, 2016), various technologies of surveillance and disciplining have been put in place in Little India, the space where large numbers of low-wage migrant workers tend to gather on Sundays, their weekly day-off. Large structured of flood lights have taken over Little India, with streets filled with auxiliary and police forces to observe, discipline, and control the workers.

12. ^At the time of conducting the interviews, various organized campaigns were being carried out to distribute masks to low-wage male migrant workers as well as foreign domestic workers. For instance, the community-grounded campaign, MaskForce, was organizing fundraising to donate masks. Several other community-grounded activities had started for organizing masks for the workers.

References

Baey, G., and Yeoh, B. S. (2018). “The lottery of my life”: migration trajectories and the production of precarity among Bangladeshi migrant workers in Singapore's construction industry. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 27, 249–272. doi: 10.1177/0117196818780087

Baey, G., and Yeoh, B. S. A. (2015). “Migration and precarious work: negotiating debt, employment, and livelihood strategies amongst Bangladeshi migrant men working in Singapore's construction industry,” in Migrating out of Poverty Working Paper 26 (Brighton: University of Sussex). Available online at: http://migratingoutofpoverty.dfid.~gov.uk/documents/wp26-baey-yeoh-2015-migration-and-precarious-work.pdf (accessed May 1, 2020).

Bal, C. S. (2015). Production politics and migrant labour advocacy in Singapore. J. Contemp. Asia. 45, 219–242. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2014.960880

Bates, B. R., Marvel, D. L., Nieto-Sanchez, C., and Grijalva, M. J. (2019). Painting a community-based definition of health: a culture-centered approach to listening to rural voice in Chaquizhca, Ecuador. Front. Commun. 4:37. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00037

Bruff, I. (2014). The rise of authoritarian neoliberalism. Rethink. Marx. 26, 113–129. doi: 10.1080/08935696.2013.843250

Bruff, I., and Tansel, C. B. (2019). Authoritarian neoliberalism: trajectories of knowledge production and praxis. Globalizations 16, 233–244. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2018.1502497

Dutta, M., Sastry, S., Dillard, S., Kumar, R., Anaele, A., Collins, W., and Spinetta, C. (2017). Narratives of stress in health meanings of African Americans in Lake County, Indiana. Health Commun. 32, 1241–1251. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1204583

Dutta, M. J. (2004a). Poverty, structural barriers, and health: a Santali narrative of health communication. Qual. Health Res. 14, 1107–1122. doi: 10.1177/1049732304267763

Dutta, M. J. (2004b). The unheard voices of Santalis: communicating about health from the margins of India. Commun. Theory. 14, 237–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00313.x

Dutta, M. J. (2007). Communicating about culture and health: theorizing culture-centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Commun. Theory 17, 304–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00297.x

Dutta, M. J. (2015). Decolonizing communication for social change: a culture-centered approach. Commun. Theory. 25, 123–143. doi: 10.1111/comt.12067

Dutta, M. J. (2016). Neoliberal Health Organizing: Communication, Meaning, and Politics, Vol. 2. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315423531

Dutta, M. J. (2017a). Migration and health in the construction industry: culturally centering voices of Bangladeshi workers in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:132. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020132

Dutta, M. J. (2017b). “Negotiating health on dirty jobs: culture-centered constructions of health among migrant construction workers in Singapore,” in Culture, Migration, and Health Communication in a Global Context, eds Y. Mao and R. Ahmed (New York, NY: Routledge), 45–59. doi: 10.4324/9781315401348-4

Dutta, M. J. (2018a). Culture-centered approach in addressing health disparities: communication infrastructures for subaltern voices. Commun. Methods Meas. 12, 239–259. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2018.1453057

Dutta, M. J. (2018b). Culturally centering social change communication: subaltern critiques of, resistance to, and re-imagination of development. J. Multicul. Discourses 13, 87–104. doi: 10.1080/17447143.2018.1446440

Dutta, M. J. (2019a). Digital transformations, smart cities, and displacements: tracing the margins of digital development. Int. J. Media Stud. 1, 1–21. Available online at: https://www.efluniversity.ac.in/Journals-Communication/IJMS1_Dutta.pdf

Dutta, M. J. (2019b). What is alternative modernity? Decolonizing culture as hybridity in the Asian turn. Asia Pac. Media Educ. 29, 178–194. doi: 10.1177/1326365X19881256

Dutta, M. J. (2020a). Infrastructures of Housing and Food for Low-Wage Migrant Workers in Singapore. Palmerston North: Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE).

Dutta, M. J. (2020b). Structural Constraints, Voice Infrastructures, and Mental Health Among Low-Wage Migrant Workers in Singapore: Solutions for Addressing COVID19. Palmerston North: Center for Culture-centered Approach to Research and Evaluation (CARE).

Dutta, M. J., and Basu, A. (2008). Meanings of health: interrogating structure and culture. Health Commun. 23, 560–572. doi: 10.1080/10410230802465266

Dutta, M. J., and Jamil, R. (2013). Health at the margins of migration: culture-centered co-constructions among Bangladeshi immigrants. Health commun. 28, 170–182. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.666956

Dutta, M. J., and Kaur-Gill, S. (2018). Precarities of migrant work in Singapore: migration, (im) mobility, and neoliberal governmentality. Int. J. Commun. 12, 4066–4084.

Dutta, M. J., Pandi, A. R., Mahtani, R., Falnikar, A., Thaker, J., Pitaloka, D., and Sun, K. (2019). Critical health communication method as embodied practice of resistance: culturally centering structural transformation through struggle for voice. Front. Commun. 4:67. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00067