94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 06 May 2020

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00021

This article is part of the Research TopicHarnessing Social Media and Digital Technologies to Improve Health CommunicationView all 7 articles

Jamie Guillory1

Jamie Guillory1 Alyssa Jordan2

Alyssa Jordan2 Ryan S. Paquin2*

Ryan S. Paquin2* Jessica Pikowski3

Jessica Pikowski3 Stephanie McInnis2

Stephanie McInnis2 Amarachi Anakaraonye2

Amarachi Anakaraonye2 Holly L. Peay4

Holly L. Peay4 Megan A. Lewis2

Megan A. Lewis2Social media platforms are becoming a key resource for health research and program delivery. These platforms offer multiple avenues to engage diverse populations using organic and paid content. Outreach to and recruitment of participants into population-based studies are important features of these platforms. We examine the potential benefit of social media for recruitment into Early Check, a statewide research program in North Carolina offering expanded newborn screening for two rare conditions that are not currently part of regular newborn screening in the state. In addition to using traditional outreach strategies—such as direct mail—we implemented social media strategies, including organic content posted to the Early Check Facebook and Twitter accounts and paid advertising on Facebook and Instagram between March and September 2019. During that time, we posted 95 organic posts on Facebook, which garnered 50,895 impressions and 373 link clicks to visit the sign-up portal and 94 posts on Twitter, with 46,638 impressions and 78 portal link clicks. We ran five paid social media ad campaigns using Facebook and Instagram, with 1,042,346 impressions total and 6,918 link clicks. The paid and organic strategies that resulted in the largest number of link clicks on ads featured images of pregnant women, relevant facts and content on key dates that might be motivating to pregnant women or new mothers, such as the first day of spring. In total, 3,298 women completed the study screener and were eligible to enroll (17.5% from paid social, 82.5% from other sources) and 2,375 enrolled (9.9% paid social, 90.1% other sources). A time series regression revealed that, on average, ~15 women enrolled in Early Check per day, excluding the effect of paid ads. On average, we observed 3.5 additional daily enrollments with paid social media ads, with 7 additional women enrolled in Early Check for every 2 days that we ran ads. Early Check is the first study to use paid and organic social media content to complement traditional outreach strategies in a recruitment effort focused on accelerating understanding of rare diseases and treatments for newborns.

Newborn screening (NBS) allows healthcare providers to identify conditions in newborns before symptoms emerge, which facilitates early treatment initiation to prevent morbidity and mortality. The Department of Health and Human Services Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) recommends that NBS programs use a uniform screening panel that includes 35 core and 26 secondary disorders (Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children, 2019). For a condition to be included in this screening panel for US states, it must be a significant public health concern, have an accurate and cost-effective test, have existing efficacious treatments, and be a condition that states are able to screen for and conduct follow-up. Although the uniform screening panel includes conditions that meet these criteria, some rare conditions may benefit from early screening. Because they are rare, researchers are unable to identify a sufficient sample of newborns to determine benefits of presymptomatic identification and generate evidence of effectiveness (Bailey and Gehtland, 2015).

Early Check is a research study that seeks to close gaps in the NBS evidence base so that rare conditions in newborns may meet the ACHDNC requirements. It offers voluntary and expanded NBS beyond what newborns typically receive from the North Carolina (NC) State Laboratory of Public Health. At the time of this study, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome are the two additional conditions offered under the Early Check protocol. The project seeks to address a core translational science challenge related to establishing the potential risks and benefits of early identification and presymptomatic treatment for babies with rare health conditions.

Obtaining parental permission for voluntary and expanded NBS research conducted on residual dried blood spots presents unique recruitment challenges. A majority of pregnant women or those who have recently given birth in the US receive little to no education about NBS (Davis et al., 2006; Tluczek et al., 2009; Botkin et al., 2016), despite evidence that public support for NBS programs is likely to be enhanced by increased transparency (Botkin et al., 2016). Parents prefer to learn about NBS and related research studies from their healthcare provider either in the third trimester or within the infant's first few days of life (Davis et al., 2006; Tluczek et al., 2009). However, healthcare providers expressed concerns about aligning NBS education with their current practice given competing demands and time constraints (Davis et al., 2006; Faulkner et al., 2006). Despite these issues, most parents are willing to permit the use of their children's NBS samples for research, provided their permission is obtained prior to such use (Davey et al., 2005; Tarini, 2011; Yeung et al., 2016). The challenge is how to reach and engage parents to gain permission for using their children's NBS samples to be used in research.

Early Check uses multiple strategies to maximize outreach and recruitment into the study (Bailey et al., 2019). Communication strategies include traditional outreach via mailings on NC Department of Public Health letterhead with an accompanying Early Check flier sent to women within 5 days of giving birth, emails containing the letter, and flier sent to women for whom an email address is available, participation in conferences that pregnant women or new mothers are likely to attend, and email blasts to professional organizations to raise awareness among professionals who serve pregnant women and new mothers.

Social media is also an important part of Early Check outreach and recruitment. Social media strategies include organic content posted to Early Check's Facebook and Twitter accounts, paid advertising on Facebook and Instagram, and engagement with social media influencers in NC who are popular among pregnant women and mothers. Influencers are asked to post organic content provided by the Early Check team to their social media accounts or to collaborate on a blog post.

Organic and paid social media content, primarily using Facebook, have been used successfully in areas related to NBS to raise awareness and engage and recruit participants for health research, indicating their use as a promising recruitment strategy. For example, Platt et al. (2013) used Facebook to raise awareness about a biobank of NBS dried blood spots. Over their 26-day ad campaign, nearly 780,000 Michigan residents saw ads an average of 25.8 times. Paid social media ads also have been used successfully to recruit pregnant women into a randomized trial (Adam et al., 2016) or online survey (Arcia, 2014), yielding a recruitment rate of 25 recruits over 26 days of social media ads (1.0 enrollment per day) and 230 recruits over 128 days of social media ads (1.8 enrollments per day), respectively. Additionally, parents of children with rare health conditions, such as pediatric cancer, also appear amendable to recruitment via social media ads, with 67 recruits over 73 social media ad days (0.9 enrollments per day; Akard et al., 2015). Moreover, these and other studies indicate that social media is a cost-effective recruitment strategy (Farina-Henry et al., 2015; Burke-Garcia and Mathew, 2017; Dyson et al., 2017).

Organic social media content has the advantage of being free; however, organic reach on Facebook has been steadily declining since 2012 because of changes in algorithms designed to prioritize posts from family and friends (Entis, 2014; Elder, 2016; Iqbal, 2018; Bernazzani, 2019). These changes make it increasingly difficult to reach key audiences with organic content. Although organic content may have lower reach, marketing experts suggest that organic content is key for developing a brand and recommend using paid and organic strategies to maximize campaign reach and engagement (Dane, 2018; The Manifest, 2018).

Early Check extends previous research because it is the first study to use paid and organic social media on multiple platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and other strategies to conduct outreach and recruitment for expanded and voluntary NBS. Additionally, our analytic approach uses time series regression analysis to demonstrate the impact of paid social media ads by modeling the temporal effect of ads on study enrollment. This approach extends the findings of previous studies that primarily used descriptive statistics to document the success of paid social media ads. Our key hypothesis is that the addition of paid social media advertisements to the Early Check recruitment channels will result in a significant increase in the number of study enrollments beyond those obtained through direct mail, email, conferences, influencer outreach, and all other outreach channels.

The aim of all Early Check outreach is to recruit prenatal and postnatal women to enroll their child in the study through a parental permission portal website. Residents of NC or South Carolina (SC) are eligible to provide permission for their infants if they are either (1) a woman who is at least 13 weeks pregnant and planning to give birth in NC, or (2) the mother of a newborn 4 weeks or younger who was born in NC. Pregnant women can enroll their child in the research study prenatally, but testing occurs after the baby is born using the same blood spot collected as part of the state's standard NBS program. All Early Check communication channels direct women to the online Early Check portal where they can learn more and provide permission. The present study focuses on Early Check's paid and organic Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter content, and subsequent Early Check enrollments over a 168-day period (March 20, 2019 through September 3, 2019).

Organic social media outreach facilitated the sharing and tagging of Early Check-branded social media content on Facebook and Twitter to (1) educate expectant and recent mothers about the significance of expanded NBS and Early Check's involvement in this mission, and (2) encourage women to learn more about the study and consider enrolling their newborns by visiting the Early Check portal. We developed an organic social media strategy using key insights from formative research conducted with English-speaking or Spanish-speaking women who recently gave birth in seven urban and rural NC counties. The organic social media content produced for Facebook and Twitter included a diversity of calls to action (e.g., “help spread the word,” “sign up”); emotional appeals (e.g., “anything for my baby,” “you can make a difference”); and engaging videos, graphics, and images displaying racially/ethnically diverse expectant mothers, expectant couples, and newborns to capture the attention of eligible expectant and new mothers. Some posts were translated into Spanish to appeal to Spanish-speaking mothers. Tagging and sharing of organic content represented a form of snowball sampling in which the tagged expectant or new mother would be notified when tagged, with the intent that once alerted, she would view the video and if interested visit the portal. We also leveraged Early Check partner networks through organic social media posts to increase reach and engagement.

Paid social media advertising included ads posted to Facebook and Instagram that featured similar text and image content as organic content, adapting content from organic posts with the greatest engagement, such as likes, shares, and comments. We designed paid advertising to direct pregnant women and new mothers to the Early Check portal with various calls to action, including “sign up,” “join,” and “learn more.” Paid ads featured giveaways in anticipation of key holidays, such as Mother's Day, posted to the organic social media outlets to encourage increased engagement with these strategies. Ads were delivered on Facebook and Instagram through four different ad sets, each targeting a different language based on user preference settings (English, Spanish) or platform (Facebook, Instagram). We used Facebook's campaign budget optimization tool, which meant that the total daily spend was distributed across all ad sets in a way that would provide the best results at the lowest cost. All ad sets were optimized in relation to Early Check eligibility using a Facebook pixel. This means a custom conversion event was placed in the back end of the Early Check portal to keep record of users who screened eligible, and Facebook used this information to distribute ads to similar users who were likely to be eligible. Over the 5 campaigns, 79.3% ($190.29 per day on average) of the budget was allocated to Facebook ads and the remaining 20.7% ($49.66 per day on average) went toward placing ads on Instagram. Aside from language and platform, all ad sets used the following targeting criteria on Facebook Ads Manager: location of residence (NC), age (18–49 years), gender (female), demographics (new parents [0–12 months]), and interests (pregnancy, Pregnancy & Birth [magazine]). Demographic and interest criteria were added to the targeting query with a Boolean OR operator, so that new moms who also had pregnancy-related interests were not excluded. Additionally, we selected the option to expand our targeting to reach more people, which allowed Facebook to extrapolate our targeting keywords to distribute ads to users who were likely to be interested and eligible based on similar interests or characteristics. Instagram ads appeared on Instagram feed and Facebook ads appeared on Facebook News Feed, Marketplace, Right Column, Messenger Inbox, Stories, Messenger Stories, Instant Articles, and Audience Network—third-party apps and sites where Facebook posts advertising content.

Individuals who clicked links on organic social media posts and paid social media ads proceeded directly to the Early Check portal, consistent with other Early Check recruitment strategies. Upon reaching the portal, the user began the consent process, which we termed “parental permission” because the parents grant permission on behalf of their newborns to enroll. Potential participants watched a short video about Early Check and then answered a series of questions to determine eligibility. Eligible users then proceeded through the Early Check consent information. Finally, users were asked if they wanted to enroll their infants in Early Check, which involved setting up an account and providing an electronic signature for their newborn's blood spot to be screened for spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome.

The primary outcome is the number of Early Check enrollments gathered from Early Check portal records. In addition to presenting overall enrollments, we aggregated the number of enrollments per day over the analysis period.

We also report the number of women who screened eligible by recruitment strategy, contrasting those who visited the portal by clicking on a paid social media ad with those who arrived at the portal through any other means, including direct mail, email outreach, organic social media, conference attendance, influencer outreach, word of mouth, or online search. The total number of women who screened eligible is an estimate based on Google Analytics data from the Early Check permissions portal. Specifically, we used unique visits to the page immediately following the eligibility screener as a metric. This estimate does not account for women who completed the screener and were eligible but closed their browsers without continuing to the next screen. The number of women who screened eligible from paid social media was calculated based on conversion tracking data collected from women who clicked through to the portal from an ad. The number of women who screened eligible and were recruited from all other sources was estimated by subtracting the number of women who screened eligible through paid social media from the total.

Secondary outcomes included the following key performance indicators to assess performance of and engagement with organic and paid social media content: number of impressions (the number of unique views of social media content), reach (the number of individual users reached by ads [metric is not provided by Twitter]), link clicks (clicks on social media content that directed participants to the permission portal), and link click-through rate (the ratio of link clicks to impressions). We used impressions and reach as indicators of performance of social media content and link clicks as an indicator of engagement with content. Organic and paid posts with the largest number of link clicks were considered “top posts” for driving the most traffic to the Early Check portal.

Demographics collected to describe the sample of women who enrolled their newborns in Early Check during the study period included permission timing, state of residence, preferred language, race, and ethnicity. These data were gathered through the Early Check portal during the eligibility screening process. Permission timing is a derived variable computed by comparing a newborn's date of birth to the date enrolled in Early Check as follows: enrollments on or after the newborn's date of birth were coded as postnatal; otherwise coded as prenatal. State of residence was gathered from the contact information that women provided when enrolling their newborns, and consistent with the study's eligibility criteria it was restricted to either NC or SC. Preferred language, race, and ethnicity were self-reported measures included in the portal.

We used descriptive statistics to describe the demographic characteristics of women who enrolled in Early Check during the study period (168 days) and the number of people who screened eligible and enrolled in Early Check via paid social media as compared with all other sources, including direct mail, email outreach, organic social media, conference attendance, influencer outreach, word of mouth, or online search (data for organic social media could not be separated out from other sources). We also report key performance indicators for organic and paid social media content overall and for top-performing posts based on posts with the largest number of link clicks.

To test the effect of our paid social media ads relative to all other recruitment strategies, we conducted a time series regression analysis predicting daily Early Check enrollment rates (Bhaskaran et al., 2013). Our model included parameters to test whether enrollment rates changed over time and the effect of running paid social media ads on the number of daily enrollments. We used a dummy-coded variable to indicate what days paid social media ads were in the field (i.e., 1 = paid ads, 0 = no paid ads). Combined, we ran social media ads for a total of 50 days distributed over the 168-day study period in five campaigns.

Because the outcome in this analysis is a count (enrollments per day), we used Poisson regression to avoid violating the normal distribution assumption characteristic of standard ordinary least squares (OLS) regression (Agresti, 2002; Ballinger, 2004; Bernal et al., 2017). Further, because our observations are a function of time, they are unlikely to be independent—with daily enrollments closer together in time likely to be more similar than enrollments farther apart (i.e., autocorrelation). Seasonal patterns in longitudinal data also can cause irregular error variance (i.e., heteroscedasticity). If present, autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity can produce biased results unless steps are taken to adjust for these in the modeling approach (Cohen et al., 2003).

We conducted diagnostic tests to determine whether such adjustments would be needed before fitting our final model, finding evidence of autocorrelation and inconclusive results concerning heteroscedasticity. To test for the presence of autocorrelation, we conducted Cumby-Huizinga tests (Cumby and Huizinga, 1992) and found evidence of lag-3 autocorrelation, χ2(1) = 7.243, p = 0.007. To test for heteroscedasticity, we conducted White-Koenker (W-K; White, 1980; Koenker, 1981) and Breusch-Pagan/Godfrey/Cook-Weisberg tests (BPG; Godfrey, 1978; Breusch and Pagan, 1979; Cook and Weisberg, 1983). Whereas, the W-K test was not statistically significant, χ2(1) = 3.42, p = 0.064, the BPG test provided evidence of heteroscedasticity, χ2(1) = 4.26, p = 0.039. Given the conflicting results from the heteroscedasticity diagnostics, we proceeded with the analysis as though the assumption of constant error variance had been violated. With this in mind, we used a combination of model specification and estimation methods that are robust against violations to the assumptions of independent errors and constant error variance.

To adjust for heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation, we fit the model with Newey-West standard errors assuming lag-3 autocorrelation. To control for seasonality, we included two sets of Fourier terms—pairs of sine and cosine functions—with a 7-day weekly periodicity in the final model (Yanovitzky and Vanlear, 2008; Bhaskaran et al., 2013). We also included dummy variables in the model to control for major holidays that fell within the analysis time period, such as Easter Sunday, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Mother's Day, and Father's Day.

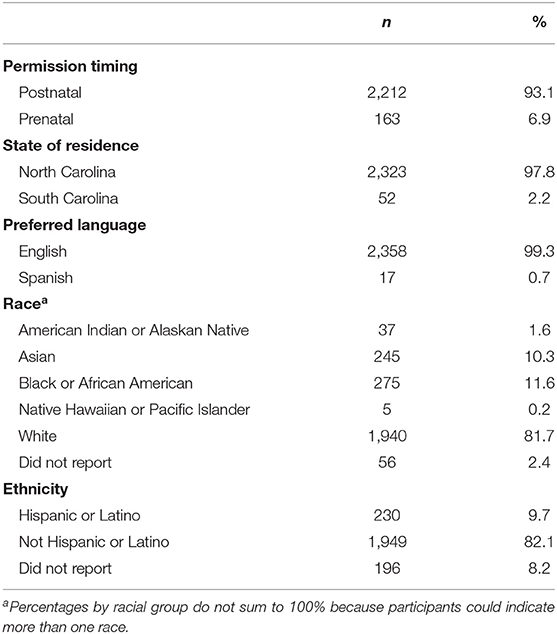

Demographic characteristics of women who enrolled their newborns in Early Check during the study period (168 days) are shown in Table 1. A large majority enrolled postnatally (93.1%), lived in NC (97.8%), and reported their preferred language as English (99.3%). The average age was 31.56 (SD = 5.50). The sample was primarily White (81.7%), followed by Black or African American (11.6%), Asian (10.3%), American Indian or Alaskan Native (1.6%), and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (0.2%). A majority of women who enrolled did not report educational attainment (86.0%). Of those who reported their education (n = 332), a majority reported having a bachelor's degree or higher educational attainment (69.6%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of women who enrolled newborns in Early Check from March 20, 2019 through September 3, 2019 (N = 2,375).

We used reach, impressions, and link clicks to assess performance and engagement with Early Check social media content, as shown in Table 2. Organic Facebook posts reached 31,136 users: 29,472 with Facebook English-language posts and 1,664 with Facebook Spanish-language posts. The organic Twitter English posts garnered a total of 46,638 impressions: 44,410 from Twitter English posts and 2,228 from Twitter Spanish posts. In terms of engagement, organic social media posts resulted in 451 total link clicks, with 364 clicks on Facebook English posts (1.2% of people who saw the posts clicked on the link), 9 clicks on Facebook Spanish posts (0.5% of people who saw the posts clicked on the link), 70 clicks on Twitter English posts, and 8 clicks on Twitter Spanish posts (percentages are not reported because Twitter does not provide reach data).

Top posts for organic social media were defined as those that had the most engagement in the form of link clicks, driving the most traffic to the Early Check portal, as shown in Figure 1. The top Facebook English-language post reached a total of 4,980 individual users and resulted in 58 link clicks (1.2% of people who saw the post clicked the link). The top Facebook Spanish-language post reached a total of 235 individual users and resulted in 1 link click (0.4% of people who saw the post clicked the link). The top Twitter English-language post garnered a total of 2,765 impressions and resulted in 16 link clicks.

The Facebook and Instagram ads used to recruit new and expectant mothers to sign up for Early Check reached 205,589 users total: 147,034 with Facebook English-language ads, 54,843 with Instagram English-language ads, 30,998 with Facebook Spanish-language ads and 9,788 with Instagram Spanish-language ads. In terms of engagement, ads resulted in 6,918 link clicks, with 4,948 clicks on Facebook English ads (3.4% of people exposed to ads clicked on links), 967 clicks on Instagram English ads (1.8% of people exposed to ads clicked on links), 954 clicks on Facebook Spanish ads (3.1% of people exposed to ads clicked on links), and 49 clicks on Instagram Spanish ads (0.5% of people exposed to ads clicked on links) (see Table 2 for full data).

Top-performing paid social media ads were defined as those with the most link clicks, driving the most traffic to the Early Check portal, as shown in Figure 2. The top Facebook English-language ad reached 49,552 users and resulted in 1,014 link clicks (2.0% of people exposed to ads clicked on link). The top Instagram English-language ad reached 10,553 users and resulted in 184 link clicks (1.7% of people exposed to ads clicked on the link). The top Facebook Spanish-language ad reached 17,448 users and resulted in 254 link clicks (1.5% of people exposed to ads clicked on the link). Because of the low overall performance of the Instagram Spanish-language campaign, a top post could not be determined.

During the study period, a total of 3,298 participants completed the Early Check screener and were eligible to enroll their infants in the study: 577 (17.5%) of the women who screened eligible had clicked through to the portal from paid social media ads and 2,721 (82.5%) arrived at the portal from all other sources. There were 2,375 enrollments (72.0% of those who screened eligible), with 234 (9.9% of enrollments) that can be traced directly back to paid social media and 2,141 (90.1%) from all other sources. A smaller proportion of women who clicked paid social media ads and screened eligible enrolled in Early Check (40.6%) than women who reached the portal and screened eligible from other sources (78.7%), suggesting a larger drop-off between the screening and enrollment process for women recruited via paid social media.

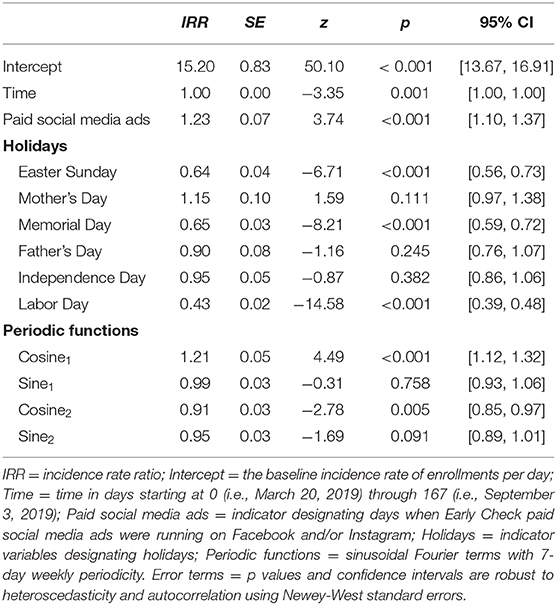

We hypothesized that the addition of paid social media ads as an Early Check outreach method would result in a significant increase in the number of study enrollments beyond enrollments obtained through direct mail, email, and other outreach approaches. We conducted a time series regression analysis to test this hypothesis, as shown in Table 3. The level of enrollments at the beginning of the series (March 20, 2019) was 15.20 enrollments per day (p < 0.001, 95% CI [13.67, 16.91]), assuming no paid social media ads were running and controlling for holidays and seasonality. We found evidence of a small reduction in this rate over time (IRRtime = 0.998, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.997, 0.999]), equivalent to a decrease of 1 enrollment from the incidence rate every 36 days. Additionally, enrollments were significantly lower than average on Easter Sunday, Memorial Day, and Labor Day.

Table 3. Final Poisson time series regression model predicting daily early check enrollments by time and paid social media ads.

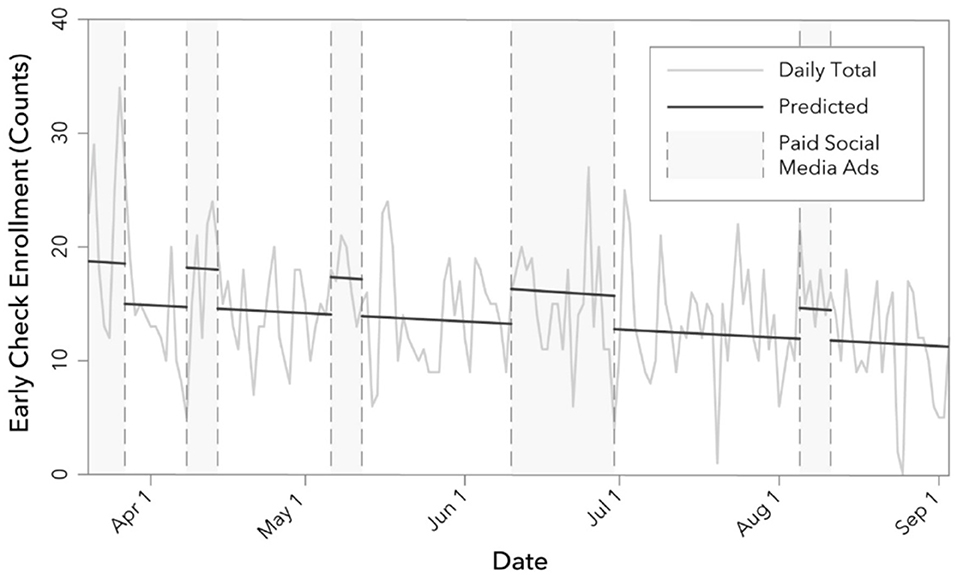

Importantly, Early Check enrollments significantly increased on days when we were in the field with paid social media ads (IRR = 1.23, p < 0.001, 95% CI [1.10, 1.37]), achieving an average of 3.5 additional enrollments per day when running ads; a 23% increase. The number of enrollments per day and the estimated trend lines on days when in the field with paid social media ads as compared with not is shown in Figure 3. This finding confirmed our hypothesis that Early Check enrollments would increase significantly with the addition of paid social media ads to other recruitment strategies. Additionally, we spent $11,997.88 on paid social media ads, which resulted in 577 eligible participants, for an average cost of $20.79 per eligible participant. The cost per eligible participant enrolled in the study via social media ads (n = 234) was $51.27.

Figure 3. A time series plot showing the daily number of Early Check enrollments from March 20, 2019, through September 3, 2019 and predicted values comparing days with or without paid social media ads. Predicted values control for seasonality and holiday effects.

Overall, the Early Check organic and paid social media outreach was able to reach, inform, engage, and motivate women to consider enrolling their newborns in the study. Our paid social media campaigns increased recruitment at a rate of 3.5 additional enrollments per day over 50 days when social media ads were running. This recruitment rate is higher than that achieved through social media ads by an online survey recruiting pregnant women (Arcia, 2014) and similar studies recruiting pregnant women and parents of children with rare health conditions (e.g., Akard et al., 2015; Adam et al., 2016). These results may be attributable to greater precision in the algorithms social media platforms use to target users, differences in the eligible populations prioritized in past studies, or the extensive user-centered formative work we conducted to understand pregnant women's and new mother's preferences and perceptions that fed into ad development (Mcinnis et al., 2019). This study supports previous research (Platt et al., 2013; Arcia, 2014; Akard et al., 2015; Farina-Henry et al., 2015; Adam et al., 2016; Frandsen et al., 2016; Burke-Garcia and Mathew, 2017) by showing that social media content is an effective strategy for engaging and recruiting study participants. We add to this body of research by comparing performance of paid and organic social media content on multiple platforms and by applying time series regression to estimate the added effect of paid social media advertising relative to other outreach methods on study enrollments in a complex, state-wide recruitment context.

On days when we ran paid social media ads, a 23% increase occurred in the number of Early Check enrollments. This finding confirmed our hypothesis that the addition of paid social media advertising to Early Check's other outreach strategies significantly increased Early Check enrollments. These findings, based on time series analysis, provide stronger evidence of the effect of paid social media ads on enrollment by controlling for temporal variables and data trends that previous studies have not accounted for.

At $51.27 per eligible participant enrolled, the cost of our social media ads was somewhat higher than similar studies that recruited pregnant women through Facebook ads (Arcia, 2014; Adam et al., 2016). A Canadian study recently recruited 39.1% of its sample of pregnant women through Facebook ads at CAD $20.28 per eligible participant recruited, compared with CAD $24.15 per eligible participant recruited through traditional approaches such as brochures, newspaper ads, local TV news, and advertisements in physicians' offices (Adam et al., 2016). A 2014 US study recruiting women within the first 20 weeks of pregnancy through Facebook ads achieved an even lower cost per eligible participant who completed the survey of $16.52 (Arcia, 2014). To date, no studies of social media ads recruiting pregnant women have provided a more direct point of comparison for the cost per recruit in an expanded NBS research study.

Despite the deprioritization of organic content on social media platforms (Entis, 2014; Elder, 2016; Iqbal, 2018; Bernazzani, 2019), Early Check organic Facebook content garnered over 50,000 impressions and Twitter content garnered almost 46,650 impressions. Our intention behind maintaining an active organic social media presence was to provide background information about Early Check and complementary outreach messaging, which is consistent with the idea that organic content is important for brand development (Dane, 2018; The Manifest, 2018).

Looking more closely at performance and engagement for paid and organic social media content by platform, we found that Facebook ads generated considerably more impressions and link clicks than Instagram ads, whereas organic Twitter posts generated fewer impressions and link clicks than Facebook posts. Given the qualitative differences among attributes represented in our paid social media ads and organic social media posts (e.g., calls to action, images, appeals), examining why certain ads and posts performed better than others is an avenue for future research.

A majority of eligible screeners and enrollments for Early Check came from sources other than paid social media. This was unsurprising given the comparatively small role that social media played in the study and the highly targeted reach of the direct mail campaign, in particular, through which recruitment letters were delivered to nearly all NC or SC residents who had given birth in NC within 4 weeks and had not yet enrolled in Early Check. We also saw that a smaller proportion of eligible women recruited directly from paid social media ads proceeded to enroll in Early Check compared with the proportion recruited from other sources. These findings suggest that although the addition of paid social media to the Early Check recruitment strategies improved the success of a statewide recruitment effort to accelerate understanding of rare diseases and treatments for newborns, other recruitment sources were responsible for the bulk of enrollments and resulted in a higher rate of screeners to enrollments. Future work is needed to examine how to increase the potential impact of social media ads and how to keep eligible women engaged to complete enrollment.

It is important to note that while Spanish-language versions of paid and organic social media content generated substantially lower reach and fewer impressions and link clicks than English-language versions, this is likely due to the fact that this subset of the North Carolina population is much smaller. Click-through rates were similar for Spanish and English ads on Facebook, but substantially lower for Spanish ads on Instagram, suggesting that Instagram may not be an ideal recruitment platform for Spanish speakers. For women who enrolled from all recruitment sources, <1% indicated Spanish as their preferred language. These findings suggest that women whose preferred language is Spanish are more challenging to reach for enrollment in expanded and voluntary newborn screening and that more concerted efforts may be needed to improve enrollment numbers among Latinas. This echoes previous research that shows language is a major barrier in NBS education and outreach among Spanish speakers (Davis et al., 2006).

This study has several limitations. First, we were unable to explore the independent effects of organic social media content on Early Check enrollment because of data limitations that prevented us from separating enrollments based on organic social media as compared with all other sources. Second, data limitations also prevented us from exploring how the characteristics of women who enrolled their newborns in Early Check differed by recruitment methods, which would shed light on how each method contributes to sample diversity. Third, social media played a comparatively small role in Early Check recruitment, making equitable comparisons difficult between social media and other more traditional outreach strategies used for Early Check.

Early Check is the first known study to use paid and organic social media content on multiple platforms, combined with other strategies, to conduct outreach and recruitment for expanded and voluntary NBS. The findings from this study add to the growing body of literature demonstrating the usefulness of paid social media content to engage and recruit pregnant women (Arcia, 2014; Adam et al., 2016) and organic and paid social media to improve engagement with NBS and biobank programs (Platt et al., 2013, 2016).

This study marks the first known research to incorporate Instagram ads in a study to recruit pregnant women and new mothers, as previous studies have focused primarily on Facebook (e.g., Arcia, 2014; Adam et al., 2016; Frandsen et al., 2016; Huesch et al., 2016). The inclusion of Instagram ads as a paid social media strategy for recruitment of pregnant women and new mothers for expanded and voluntary NBS is important because Instagram is particularly popular among young adults, a key age group of pregnant women and new mothers (Smith and Anderson, 2018). Specifically, Instagram use is higher among 18–29-year-olds (64%) than 30–49-year-olds (40%) (Smith and Anderson, 2018), suggesting that to optimize Instagram ads future studies should consider focusing Instagram recruitment on 18–29-year-old pregnant women and new mothers.

Early Check provides a unique case study for health communicators and newborn screening researchers seeking to maximize the potential of social media for study recruitment amid a rapidly evolving digital landscape. This study demonstrates the complementary use of organic and paid social media targeting prenatal and postnatal women to participate in voluntary and expanded NBS. With the noted decline in the organic reach of promotional Facebook posts (Entis, 2014; Elder, 2016; Iqbal, 2018; Bernazzani, 2019), similar studies may increasingly invest in paid social media advertising as an effective digital recruitment approach, with organic content playing a supportive role in engaging populations of interest.

Traditional recruitment methods, including direct mail and email, can be enhanced by organic and paid social media outreach for statewide population health studies like Early Check. This research supports the case for collaboration among researchers, communication specialists, designers, and digital strategists to fully harness social media outreach for study recruitment.

The raw social media analytics data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher; however, the enrollment datasets for this article derived from the Early Check permissions portal are not publicly available to protect participant privacy and confidentiality. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to RP: cnBhcXVpbkBydGkub3Jn.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JG, AJ, RP, JP, ML, and SM wrote sections of the article. RP conducted the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version. All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study.

The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (Award # U01TR001792 and UL1TR001111) provide core funding for Early Check and supports linkages with university partners. The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Award # HHSN27500003) provides support for laboratory testing, diagnostic confirmation, and short-term follow-up for infants who screen positive for spinal muscular atrophy. The John Merck Fund provides support for research activities related to fragile X syndrome, including a pilot early intervention program and a telegenetic counseling program. Asuragen provides reagents and equipment for fragile X screening and diagnostic confirmation. Cure SMA provided funds to purchase some of the equipment needed to screen for spinal muscular atrophy. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any of the other project funders. The funding bodies played no role in study collection, analyses, interpretation of results, or writing this manuscript. The awards from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences were peer reviewed by the funding body.

JG was employed by the company Prime Affect Research and working under contract for this project through RTI International, an independent, nonprofit research institute.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Early Check is supported in part by contributed reagents and equipment from Asuragen, but none of the authors has a personal or financial relationship with Asuragen.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of other Early Check team members: Don Bailey (Early Check, Principal Investigator), Lisa Gehtland, Blake Harper, Melissa Raspa, Anne Wheeler, and Martin Duparc as well as other Early Check partners including Cindy Powell at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Michael Cotten at Duke University, Nancy King at Wake Forest School of Medicine, and Scott Shone at the NC State Laboratory of Public Health.

Adam, L. M., Manca, D. P., and Bell, R. C. (2016). Can facebook be used for research? experiences using facebook to recruit pregnant women for a randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet 18:e250. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6404

Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns Children (2019). Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children Homepage. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Available online at: https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/index.html.

Akard, T. F., Wray, S., and Gilmer, M. (2015). Facebook ads recruit parents of children with cancer for an online survey of web-based research preferences. Cancer Nurs. 38, 155–161. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000146

Arcia, A. (2014). Facebook advertisements for inexpensive participant recruitment among women in early pregnancy. Health Educ. Behav. 41, 237–241. doi: 10.1177/1090198113504414

Bailey, D. B. Jr., and Gehtland, L. (2015). Newborn screening: evolving challenges in an era of rapid discovery. JAMA 313, 1511–1512. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17488

Bailey, D. B. Jr., Gehtland, L. M., Lewis, M. A., Peay, H., Raspa, M., Shone, S. M., et al. (2019). Early check: translational science at the intersection of public health and newborn screening. BMC Pediatr. 19:238. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1606-4

Ballinger, G. A. (2004). Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 7, 127–150. doi: 10.1177/1094428104263672

Bernal, J. L., Cummins, S., and Gasparrini, A. (2017). Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 348–355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098

Bernazzani, S. (2019). The Decline of Organic Facebook Reach & How to Adjust to the Algorithm. Cambridge, MA: HubSpot, Inc. Available online at: https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/facebook-organic-reach-declining (accessed October, 29 2019).

Bhaskaran, K., Gasparrini, A., Hajat, S., Smeeth, L., and Armstrong, B. (2013). Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 1187–1195. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt092

Botkin, J. R., Rothwell, E., Anderson, R. A., Rose, N. C., Dolan, S. M., Kuppermann, M., et al. (2016). Prenatal education of parents about newborn screening and residual dried blood spots: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 170, 543–549. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4850

Breusch, T. S., and Pagan, A. R. (1979). A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica 47, 1287–1294. doi: 10.2307/1911963

Burke-Garcia, A., and Mathew, S. (2017). Leveraging social and digital media for participant recruitment: a review of methods from the bayley short form formative study. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 1, 205–207. doi: 10.1017/cts.2017.9

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., and Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied Multiple Correlation/Regression Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cook, R. D., and Weisberg, S. (1983). Diagnostics for heteroscedasticity in regression. Biometrika 70, 1–10. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.1

Cumby, R. E., and Huizinga, J. (1992). Testing the autocorrelation structure of disturbances in ordinary least squares and instrumental variables regressions. Econometrica 60, 185–195. doi: 10.2307/2951684

Dane, J. (2018). How Paid and Organic Facebook Efforts Support Each Other. New York, NY: Adweek. Available online at: https://www.adweek.com/digital/how-paid-and-organic-facebook-efforts-support-each-other/ (accessed October 29, 2019).

Davey, A., French, D., Dawkins, H., and O'leary, P. (2005). New mothers' awareness of newborn screening, and their attitudes to the retention and use of screening samples for research purposes. Genomics Soc. Policy 1:41. doi: 10.1186/1746-5354-1-3-41

Davis, T. C., Humiston, S. G., Arnold, C. L., Bocchini, J. A. Jr., Bass, P. F. III., Kennen, E. M., et al. (2006). Recommendations for effective newborn screening communication: results of focus groups with parents, providers, and experts. Pediatrics 117, S326–S340. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2633M

Dyson, M. P., Shave, K., Fernandes, R. M., Scott, S. D., and Hartling, L. (2017). Outcomes in child health: exploring the use of social media to engage parents in patient-centered outcomes research. J. Med. Internet Res. 19:e78. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6655

Elder, R. (2016). Publishers' Organic Reach on Facebook Appears to have Dropped. New York, NY: Business Insider. Available online at: https://www.businessinsider.com/publishers-organic-reach-on-facebook-has-tanked-2016-8.

Entis, L. (2014). Facebook Explains Why Organic Reach is Dying. Irvine: Entrepreneur. Available online at: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/234594 (accessed October 29, 2019).

Farina-Henry, E., Waterston, L. B., and Blaisdell, L. L. (2015). Social media use in research: engaging communities in cohort studies to support recruitment and retention. JMIR Res. Protoc. 4:e90. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4260

Faulkner, L. A., Feuchtbaum, L. B., Graham, S., Bolstad, J. P., and Cunningham, G. C. (2006). The newborn screening educational gap: what prenatal care providers do compared with what is expected. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194, 131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.075

Frandsen, M., Thow, M., and Ferguson, S. G. (2016). The effectiveness of social media (facebook) compared with more traditional advertising methods for recruiting eligible participants to health research studies: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 5:e161. doi: 10.2196/resprot.5747

Godfrey, L. G. (1978). Testing for multiplicative heteroskedasticity. J. Econom. 8, 227–236. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(78)90031-3

Huesch, M. D., Galstyan, A., Ong, M. K., and Doctor, J. N. (2016). Using social media, online social networks, and internet search as platforms for public health interventions: a pilot study. Health Serv. Res. 51(Suppl. 2), 1273–1290. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12496

Iqbal, W. (2018). Facebook Marketing: Organic vs Paid Reach. A Medium Corporation. Available online at: https://medium.com/digital-realm/facebook-marketing-organic-vs-paid-reach-a53eed38b8b2 (accessed October, 29, 2019).

Koenker, R. (1981). A note on studentizing a test for heteroscedasticity. J. Econom. 17, 107–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(81)90062-2

Mcinnis, S., Guillory, J., Pikowski, J., Jordan, A., Paquin, R., Anakaraonye, A., et al. (2019). “Developing social media ads to recruit expectant and new moms in North Carolina,” in Annual Southern Association for Public Opinion Research Conference (Raleigh, NC).

Platt, J. E., Platt, T., Thiel, D., and Kardia, S. L. (2013). 'Born in Michigan? you're in the biobank': engaging population biobank participants through facebook advertisements. Public Health Genom. 16, 145–158. doi: 10.1159/000351451

Platt, T., Platt, J., Thiel, D. B., and Kardia, S. L. (2016). Facebook advertising across an engagement spectrum: a case example for public health communication. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2:e27. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5623

Smith, A., and Anderson, M. (2018). Social Media Use in 2018. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/.

Tarini, B. A. (2011). Storage and use of residual newborn screening blood spots: a public policy emergency. Genet. Med. 13, 619–620. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31822176df

The Manifest (2018). How to Create Strategies for Organic vs. Paid Social Media Marketing. Medium.com. Available online at: https://medium.com/@the_manifest/how-to-create-strategies-for-organic-vs-paid-social-media-marketing-ce4e754606f7 (accessed October 29, 2019).

Tluczek, A., Orland, K. M., Nick, S. W., and Brown, R. L. (2009). Newborn screening: an appeal for improved parent education. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 23, 326–334. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e3181a1bc1f

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 48, 817–838. doi: 10.2307/1912934

Yanovitzky, I., and Vanlear, A. (2008). “Time series analysis: traditional and contemporary approaches,” in The SAGE Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research, eds A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, and L. B. Snyder (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 89–124. doi: 10.4135/9781452272054.n4

Keywords: newborn screening, social media, Facebook advertising, recruitment, outreach, social media engagement

Citation: Guillory J, Jordan A, Paquin RS, Pikowski J, McInnis S, Anakaraonye A, Peay HL and Lewis MA (2020) Using Social Media to Conduct Outreach and Recruitment for Expanded Newborn Screening. Front. Commun. 5:21. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00021

Received: 31 October 2019; Accepted: 16 March 2020;

Published: 06 May 2020.

Edited by:

Sunny Jung Kim, Virginia Commonwealth University, United StatesReviewed by:

Chiara Rollero, University of Turin, ItalyCopyright © 2020 Guillory, Jordan, Paquin, Pikowski, McInnis, Anakaraonye, Peay and Lewis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ryan S. Paquin, cnBhcXVpbkBydGkub3Jn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.