- 1School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada

- 2Politics, School of Social Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 3School of Political Studies, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

This paper interrogates how the notion of hypocrisy is invoked in relation to climate change and offers two key findings. First, it demonstrates that invocations of hypocrisy are not only deployed by conservative opponents of climate action, but also by progressive proponents of such action. Second, this article shows that while hypocrisy discourse is used to support both anti- and pro-climate change perspectives, its nature and function fundamentally differs depending on who is using it. The article identifies four discrete types of climate hypocrisy discourse. Conservatives who reject climate change action tend to use two “modes” of hypocrisy discourse. The first is an “individual lifestyle outrage” mode that cultivates outrage about the hypocritical behavior and lifestyle choices of climate activists to undermine the urgency and moral need for climate change action. The second, an “institutional cynicism” mode, encourages a cynical fatalism about any proposed governmental action regarding climate change by suggesting that governments are necessarily climate hypocrites because of the economic and political impossibility of serious emissions reductions. In contrast, progressives use hypocrisy discourse in two different modes. The first involve an “institutional call to action” mode that uses charges of hypocrisy to attack government inaction on climate change and demand that effective action be taken in line with their public commitment to climate action. Secondly, they also employ a “reflexive” mode in which explorations of the ubiquity of climate change hypocrisy illuminate the dilemmas that virtually all responses to climate change necessarily grapple with in our current context. Overall, the article seeks to contribute to our understanding of climate change communications by (i) showing that hypocrisy discourse is not simply a sensationalist PR strategy of conservatives but is rather a broad, significant and multi-faceted form of climate change discourse; and (ii) suggesting that certain modes of hypocrisy discourse might not only represent genuine attempts to make sense of some of the fundamental tensions of climate change politics but also help us understand the challenge that the “entanglement” of personal agency/choice within broader political structures presents, and thus heighten positive affective commitments to climate change action.

Introduction

Less than a day after An Inconvenient Truth won an Academy award for best documentary, Al Gore was back in the headlines when a “free market” advocacy group—The Tennessee Center for Policy Research—revealed that the gas and electric bills for Gore's Nashville mansion were more than twenty times higher than the US average. “As the spokesman of choice for the global warming movement, Al Gore has to be willing to walk the walk, not just talk the talk, when it comes to home energy use,” explained the Center's president, Drew Johnson (Cited in Elsworth, 2007a). The exposure of Gore's energy hypocrisy was widely reported in news items, columns, op-eds and letters to the editor across the globe. “Truth indeed inconvenient for American activist” sneered The National Post (Elsworth, 2007b). Gore's well-known call to (individual) action at the close of his film–“are you ready to change the way you live?”–provided an ideal opening to drive home the attack. When Gore subsequently rejected US Senator James Inhofe's demand that he pledge to reduce his own energy consumption, British commentator Cazzullino (2007) heralded the refusal to “tak[e] the challenge thrown down by your very own documentary” as a “nod to the screaming hypocrisy of those who shout the loudest in the climate change debate.” A letter writer to the Washington Post leveraged Gore's Oscar win to assail the “irony and hypocrisy” of Hollywood glitterati championing the cause of climate change: “These people who own palatial, energy-eating estates in Malibu, fly private jets around the world and arrive at the red carpet in stretch limos, lecturing the rest of us about the size of our carbon footprint? Please! … their supposed concern for the planet is merely another “do as I say, not as I do” mandate from the Hollywood and Washington elites.” (Lyman, 2007)

A little more than a decade later, accusations of climate hypocrisy were again attracting international headlines. “Stop swooning over Justin Trudeau,” thundered U.S. environmental activist McKibben (2017) in a widely-circulated op-ed for The Guardian. “Donald Trump is a creep and unpleasant to look at,” explained McKibben, “but at least he's not a stunning hypocrite when it comes to climate change.” McKibben may hold a diametrically opposed perspective to many of Trudeau's opponents on the need to address climate change, yet similarly mobilized the charge of climate hypocrisy to expose and challenge the institutional “attitude-behavior” gap of the Trudeau government.

McKibben thus charged that the Canadian Prime Minister's climate rhetoric hit all the right notes, “but those words are meaningless if you keep digging up more carbon and selling it to people to burn”. He likewise castigated Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull as a climate hypocrite for committing to the Paris climate accords on the one hand and backing plans for the single largest coal mine on the planet on the other. While these accusations attracted considerable media attention and public debate (e.g., Leach, 2017), it was not the first time Trudeau had been attacked for climate hypocrisy. In the midst of the Canadian election campaign, conservative tabloid columnist Goldstein (2015) argued that “every criticism Trudeau makes about [Canadian Prime Minister] Harper for withdrawing from Kyoto reeks of duplicity and hypocrisy” given the Liberal Party's predilection for making commitments they had no intention or capacity to meet. A little over a year later, Goldstein (2016) again levied the hypocrisy charge: “If the Trudeau government believed its own rhetoric about man-made climate change, it would be leading us right now by setting an example of frugality and austerity. It would walk the walk, instead of just talking the talk.”

Understanding how hypocrisy discourse works is important analytically but also strategically in the pursuit of more adequate social and political responses to climate change. The most commonly recognized examples of climate change hypocrisy discourse employ a largely individualizing, moralizing register to undercut any collective, political response to climate change (a strategy, it should be noted, used by contemporary conservative perspectives on a variety of policy issues). In this version (largely used by those challenging the value of climate change policy), hypocrisy discourse plays up the moral value that contemporary culture places on the individual's responsibility to act while largely dismissing the idea that broad social, collective, and systemic practices may have any influence on those actions. Rather than understanding the high carbon world we inhabit as the product of large-scale systems (transport infrastructures, building construction, electricity grids, and so on) and routinized, embedded practices (driving, cooling, heating, flying), this type of hypocrisy discourse abstracts from these systems and routines and instead allocates moral responsibility to the individual for each specific action within these contexts. Understanding precisely how this type of hypocrisy discourse functions is thus an important task if we want to understand how contemporary climate change communications functions.

In reality, however, climate change hypocrisy discourse is much more complex. For example, even the hypocrisy discourse of what we call a conservative, anti-climate action perspective is more nuanced and layered than is often acknowledged. Moreover, the existing literature is almost entirely silent on the possibility that hypocrisy discourse might also be used to cut against the grain of individualized, neo-liberal political discourse, directing public attention and outrage to the stark contradiction between the climate-friendly rhetoric adopted by so many politicians, governments and other institutions and a “business-as-usual” approach that not only fails (or refuses) to tackle emissions reduction but continues to facilitate, support and subsidize carbon-intensive industries and infrastructure. The cynical displacement of personal responsibility to externalized structures has long been a feature of climate discourse in both the private and public sphere (Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Norgaard, 2011). Yet the constellation of such displacement with the moralized language of hypocrisy may open up novel conceptual and affective configurations in which to engage with the multiple entanglements of public and private that lie at the core of climate politics. Exploring the nature and function of these less obvious types of hypocrisy discourse is thus an important task for climate change communications.

Rather than assume that climate change hypocrisy discourse functions in a particular way, for particular ends, then, this article seeks to analyze current climate change hypocrisy discourse in detail to better understand its complexity, diversity and potential.

Hypocrisy and Climate Communication

While many scholars have, in passing, noted the rhetorical force of hypocrisy in discourse about climate change, there has been no systematic empirical study or robust theorization of the nature of hypocrisy discourse. Scholars have noted the hypocrisy intrinsic to much celebrity advocacy (Boykoff and Goodman, 2009; Anderson, 2011; Cooper et al., 2012); the utility of hypocrisy for attacks on the credibility of climate scientists and environmental activists (Gavin and Marshall, 2011; Knight and Greenberg, 2011; Mayer, 2012; Gunster and Saurette, 2014; Marshall, 2014); the existence of accusations of hypocrisy directed toward state actors and climate policy (Platt and Retallack, 2009; Webb, 2012; Eckersley, 2013; McGregor, 2015); the impact of hypocrisy accusations in shifting climate discourse into a moral register (Young, 2011; Dannenberg et al., 2012); representations of the general public as hypocritical (Höppner, 2010); and the hypocrisy of “green” consumerism (Barr, 2011; Laidley, 2013). Such references to climate hypocrisy, however, are largely cursory and under-developed, noting the idea's rhetorical significance without any sustained investigation.

Two recent exceptions to this context suggest scholars may be starting to devote greater attention to the proliferation of climate hypocrisy. Attari et al. (2016) conducted two experimental surveys that explored how the disclosure of a climate researcher's carbon footprint affected their public credibility as an advocate of lifestyle change. Unsurprisingly, the disclosure of emissions-intensive behavior (frequent flying and/or high energy use at home) of such researchers markedly reduced perceptions of their credibility as well as the likelihood they could persuade audiences to reduce their own energy consumption. The study attracted considerable attention in environmental media such as Grist (Song, 2016) and Inside Climate News (Yoder, 2016), and it was also featured prominently on the climate denial blog Watts Up With That? (Watts, 2016). Another recent study (Schneider et al., 2016) offered a critical reading of how the U.S. fossil fuel industries and their allies have mobilized accusations of hypocrisy to undermine the credibility of the divestment movement. Such rhetoric, they argue, is a perfect fit for an intensely neo-liberal, individualized conception of (depoliticized) agency in which market-based consumer lifestyle choices are normalized as the only means of social and economic change.

These two articles offer fascinating explorations into some specific ways that charges of hypocrisy can weaken the credibility of advocates for emissions reduction and divestment. Our goal in this paper, however, is different. We sought to conduct a much broader and wide-ranging exploration of how the idea of climate hypocrisy functions in the public sphere. We found that there are different types of climate hypocrisy discourse that have very different natures and very different effects.

Method

Using Factiva, we conducted keyword searches for “global warming” or “climate change” and “hypocrisy,” “hypocrite” and/or “hypocritical” in order to identify the top sources of “climate hypocrisy” discourse among English-language newspapers in Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States between January 1, 2005 and August 15, 2015. We selected the two newspapers with the most articles responding to these keyword searches in each country for inclusion in our sample: in Canada, The National Post (owned by Postmedia) and The Globe and Mail (Woodbridge Company); in Australia, The Australian (News Corp.) and The Telegraph (News Corp.); The Guardian (Guardian Media Group) and The Telegraph (Telegraph Media Group) in the United Kingdom; and The Wall Street Journal (News Corp.) and The New York Times (Ochs-Sulzberger family) in the United States. In addition, we added the newspaper in each country with the highest circulation as of 2015: in Canada, The Toronto Star (Torstar Corp.); The Herald-Sun (News Corp.) in Australia; The Sun (News Corp.) in the United Kingdom; and in the case of the United States, given that this paper—The Wall Street Journal—was already included, we instead added The Washington Post (Jeff Bezos) as it had the third highest number of climate hypocrisy items among US newspapers.

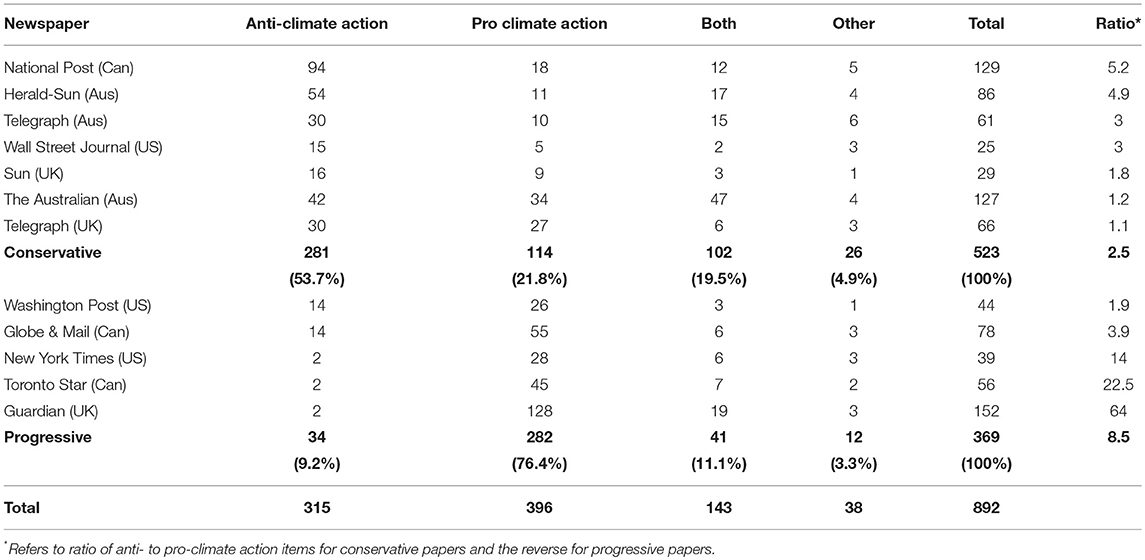

Our total sample, then, consists of twelve prominent daily newspapers which harbor a diversity of ideological perspectives on climate change both across and between countries, ranging from The Guardian's aggressive championing of pro-climate actions and policy to conservative papers such as The National Post, The Wall Street Journal and The Herald-Sun which are not only critical of climate policy but often marshal their editorial resources to promote skepticism about climate science. This comprehensive approach provides a good representation of how the language of hypocrisy has been mobilized around climate change in these four countries over a decade. We collected all items where climate change or global warming and hypocrisy were explicitly linked, generating a sample of 892 items.

We conduct a detailed quantitative analysis of these articles elsewhere (Gunster et al., 2018), mapping the distribution of key characteristics such as pro- vs. anti-climate action orientation, presence of climate science denial, targeted actors and behaviors, affective intensity and the prominence of three distinct types of hypocrisy discourse (personalized, institutional-analytic, reflexive). Among the most surprising findings of this analysis was the fact that references to hypocrisy were more frequently embedded within arguments supporting stronger climate action than opposing it. As Table 1 suggests, the distribution of these sentiments across newspapers, however, was quite uneven with different papers (and the authors within them) developing starkly different accounts of climate hypocrisy depending upon their broader orientation to climate change politics and policy. We have roughly divided the papers between two broad ideological clusters in relation to climate change: conservative (those papers in which the number of anti-climate action items outnumber the pro-climate action items) and progressive (those papers in which the opposite is true). We use this division to structure the qualitative analysis that follows, exploring how different variants of climate hypocrisy work politically as storylines.

Less surprising, perhaps, but nevertheless important for this analysis, was that we found that the most powerfully affective forms of climate hypocrisy discourse (especially, but not exclusively from conservatives opponents of action on climate change) was driven by columnists rather than news articles. The analysis that follows draws mostly on columnists, both for this reason and also because they express particular sorts of claims precisely and powerfully. The exception is in the discussion of reflexive hypocrisy discourse, where a good deal of this material comes from news articles, often extended interviews with climate activists for example. These observations obviously raise many more questions than we can explore here (including whether various political perspectives have distinctly identifiable rhetorical tendencies/preferences when debating contemporary climate change policy). Some of these questions are further discussed in Gunster et al. (2018). Others are the subject of ongoing research and will be explored in future publications.

In this article, however, we focus primarily on the task of uncovering, and analyzing the nature of, the four different types of hypocrisy discourse that exist in climate change discourse. We start with what we define as conservative use of hypocrisy as an attack against individuals that attempts to generate outrage because of the contradictions between climate advocacy and personal behavior, followed by conceptually distinct emphasis upon the inevitability of institutional hypocrisy to generate cynicism about the prospects for political action on climate change. “Conservative” here is meant to relate only to the function of the hypocrisy discourse itself to limit, stall, or remain ambivalent to climate change action. Often, but not always, “conservative” approaches overlap with publications that have politically conservative stances. We then examine the deployment of hypocrisy for “progressive” purposes, promoting action on climate change. This starts with the institutional charges, where the attack against governments and other institutions is deployed to put pressure on them for improved action on climate change. Again, “progressive” here refers to the operationalization of the discourse itself. We then discuss reflexive hypocrisy discourse, which shifts the focus back to individual lifestyles and practices, but in a way that brings back into focus the relationship between these practices and broader political systems and struggles. We conclude with a few thoughts about how climate hypocrisy intersect with recent calls for the (re)politicization of climate change.

Conservative Formations of Climate Hypocrisy: From Outrage to Cynicism

This section outlines the two key types of conservative hypocrisy discourse—both of which seek to undermine action on climate change, but in different ways. The first type–what we term the “individual lifestyle outrage” mode–cultivates outrage at the contradictions between the pronouncements on climate change of key climate advocates and their personal, individual lifestyles in terms of carbon emissions. Here, conservative “populist” invocations of class are foregrounded as climate advocates are portrayed as out of touch elitists. Such accusations are based upon three discursive moves: to shift climate change from a political to a moral, individual frame; to emphasize the importance of personal sacrifice in climate responses (so that individuals arguing for climate action can be judged by the extent to which they enact such sacrifice); and to argue that environmentalists are mostly engaged in self-promotion rather than serious politics, because if they were serious we'd see substantial changes in their action. The second type–what we call the “institutional cynicism” mode—generates and justifies cynicism around governmental action on climate change by portraying governments as inevitably and necessarily hypocritical on climate change, and thus fundamentally untrustworthy. In this story, politicians and political institutions are bound to be fundamentally hypocritical since although they are forced to address the issue (due to pressure from special interests), they cannot (and will not) do anything truly effective given the variety of political, economic and cultural constraints they face. Which, in turn, leads to the conclusion that even if we were so inclined, we should not count on government action as something that might actually make a difference.

Let us begin with the first type. Al Gore was the most vilified figure in our sample, a literal poster child for lifestyle hypocrisy. And yet, as the letter from the Washington Post highlighted to begin suggests, there was nothing particularly unique or compelling about the accusations levied against Gore, which could just as easily be marshaled against other symbols of environmental hypocrisy, such as the eco-celebrities of Hollywood. Irrespective of the particular details of any given instance of lifestyle hypocrisy, the basic formula animating such stories was almost always the same: inflate and individualize the lofty, moralizing, prescriptive rhetoric attributed to the target (to make it appear as if their primary intent is to prescribe personal, behavioral change rather than, for example, the need for institutional, political or policy-based change); dramatize transgressions by accenting their distance from the consumptive and behavioral norms of everyday life (so that the hypocritical act is framed primarily as a luxury that is beyond the reach of most people); and position the lifestyle or behavior as a consequence of personal preference or choice (and, preferably, a matter of leisure and pleasure, rather than necessity). These are the principal, constitutive ingredients of lifestyle hypocrisy.

Such attacks were primarily articulated with items that ridiculed the necessity or urgency of action to address climate change. News items documenting contradictions between climate advocacy and carbon-intensive lifestyles–aptly dubbed ‘gotcha environmentalism‘ by a Globe and Mail Editorial (2007)–appeared in all the newspapers, though with much greater frequency in those on the conservative end of the spectrum. As with the reporting about Gore's energy use, such news stories were often precipitated by accusations of hypocrisy from an external source such as opposition politicians or interest groups. The conservative British tabloid, The Sun, in particular, favored such “gotcha” stories, especially those that skewered politicians and bureaucrats, usually for lavish use of air travel in a government ostensibly committed to reducing emissions. Typical headlines included: “2 Flights A Day By Eco Staff” (Kay, 2010) – climate change civil servants using internal UK flights rather than trains; “Chris and Gwyn take Tube…so can Huhne” (Moore, 2011)–Energy Secretary running up chauffeur bills while celebrities take public transit; “£1.5M Air Fury” (The Sun, 2012)–excessive air travel by energy ministers and officials; “Ed In The Clouds” (Fawkes, 2013)–extensive reliance of Energy and Climate Change Secretary Ed Davey on flights while increasing costs of air travel for average consumers; and “What a Charlie” (The Sun, 2015)–Prince Charles flying by helicopter to attend a sporting event; with each item doing little more than reminding readers of the serial, omnipresent failures of the wealthy and powerful to practice what they preach. Such exposés were often followed up a few days later with chains of (nearly identical) letters from indignant readers, cultivating perceptions of mass outrage from “ordinary people”: “How dare Prince Charles fly to Brazil's rainforest, then preach to me about my carbon footprint?” or “The prince, right, has a nerve flying all the way to South America and then lecturing us about taking care of the environment. It is nothing short of total hypocrisy.” (Letters, 2009).

While most news items restricted themselves to pointing out a single transgression or event, conservative columnists played a critical role in knitting together such anecdotes into more coherent and compelling narratives of conservative populism which figure environmentalism as a conspiracy of liberal elites seeking to impose a puritanical program of ascetic sacrifice upon others that they are unwilling to accept for themselves. For Australian Herald columnist Tim Blair (2007), “Walk to Work Day”—a festival of “enviro-tokenism” in which cab drivers are deprived of their hard-earned livelihoods—provided an ideal opportunity to “take a walk through the year of the hypocrite” and ruminate on the ubiquity of “rich folk…demanding others reduce their quality of life while stomping around like emperors”. From “Canadian enviromonk David Suzuki…staining [the nation] black with diesel fumes from his gigantic rock star-style tour bus” to Gore's utility bill debacle to a “12-cylinder, 300km/h, Gaia-torturing Bentley Continental GTC” owned by one of the performers in Gore's Live Earth concert, Blair assembled anecdote after anecdote to illustrate that “if this year has a theme…it must be ‘sanctimonious wealthy people telling others how to live’.”

The most persistent chronicler and theorist of lifestyle hypocrisy was Andrew Bolt, the prolific and often vitriolic columnist for The Herald-Sun who routinely used such sins to anchor more substantive reflections on the environmental movement and climate change. “It can't be an accident,” Bolt (2007) reasoned, “that global warming attracts more hypocrites than most faiths,” piling up example after example of the carbon-intensive extravagance of those sounding the alarm about high levels of emissions. “So what,” he concludes, “is the moral in this carnival of hypocrisy?”

It's that global warming is an apocalyptic faith whose preachers demand sacrifices of others that they find far too painful for themselves. It's a faith whose prophets demand we close coal mines but who won't even turn off their own pool lights. Who demand the masses lose their cars, while they themselves keep their planes. It's the ultimate faith of the feckless rich, where a ticket to heaven can be bought with a check made out to Al Gore [to purchase offsets from a company he owns]. No further sacrifice is required. Except of course, from the poor. While Gore's lights burn brightly, for you the darkness is coming.

The dominance of religious metaphor–“faith,” “preachers,” “prophets,” “evangelists,” “sacrifice”–is striking and a persistent feature of Bolt's writing about climate hypocrisy. It is used to frame climate advocacy, first and foremost, as a moral crusade whose credibility and integrity is entirely dependent upon the personal virtues of its “preachers” and “prophets.” While Bolt himself is deeply skeptical of climate science, challenging the scientific or empirical veracity of anthropogenic climate change plays a minor role in his deconstruction of climate advocacy. Likewise, the economic frames often favored by those casting aspersions upon the merits of environmentalism, do not figure prominently in the logic of his arguments. Similar to Bolt, McCrann (2014)–a columnist for The Australian–invokes both ignorance and faith to delegitimize climate action via the perceived moral ambiguity of its adherents. “Has there ever been a more perfect union of stupidity, dishonesty, hypocrisy and hysteria, wrapped up in sheer bottomless lack of self-awareness, than the global warming cause and its legions of true unthinking believers?”

Beyond rhetorically savaging the reputation of particular climate advocates, conservative diatribes against lifestyle hypocrisy also function to assert three broader claims about climate change and environmentalism. The first, as already noted, is the shifting of environmental discourse into a moral register, a move that skillfully echoes the sentiments of those—like Gore and, more recently, the Pope—who insist that climate change is not simply a scientific or political issue but also, more fundamentally, a profoundly moral problem. As a consequence, the burden of proof shifts from the scientific evidence itself to the individual behavioral responses of those “who shout the loudest” about the problem: “When these folks give up their air conditioners, cars, Blackberrys, cellphones and oversized homes,” notes a Globe and Mail letter writer, “we can take them more seriously” (Van Velzen, 2007). Authentic, genuine commitment to environmentalism must necessarily involve individual sacrifice and (de)privation: it is only by “giving up” the comforts and conveniences of consumer society that one not only keeps faith with environmental ideals but attests to the reality and truth of climate change as a problem. This is the second key conservative claim: the emphasis upon lifestyle hypocrisy persuasively identifies personal sacrifice as the core feature of environmentalism, a demand freighted with both moral and epistemological significance. Sacrifice becomes not only a signifier of moral character but also scientific truth and, conversely, its absence serves as a convenient heuristic to dismiss climate science as an elite charade. This one-dimensional but compelling equation of environmentalism with sacrifice leaves climate advocates in a proverbial no-win situation when it comes to reconciling behavior with beliefs. As author Lynas (2007) wryly observed in a Guardian op-ed, “climate activists I know who do walk the walk (eschewing all flights, for example) look prim and obsessive, as if they are out of touch with the concerns and pressures faced by ordinary people.” Yet the views of those who do resemble “ordinary people,” and therefore fail to pay adequate behavioral homage to the gravity of the crisis, are likewise subject to ridicule and dismissal.

Ultimately, the seemingly endless accumulation of anecdotes about lifestyle hypocrisy hammers home the third major claim of conservatives that, for its advocates, environmentalism is first and foremost a symbolic project of self-fashioning and self-promotion, designed to make them feel better about themselves. Taking action that would actually lighten one's ecological footprint is beside the point. On this count, there is a striking convergence of conservative rhetoric about lifestyle hypocrisy with environmentalist criticism of corporate greenwashing. Much like corporations strive to burnish their image—and feel better about themselves in the process—through symbolic action which has little real impact, so too does environmentalism serve its predominantly upper-class constituencies as a gigantic vanity project through which to cultivate impressions of social conscience. Remarking upon the growing fetish for luxurious eco-mansions, Wall Street Journal features writer Akst (2006) observed “these houses aren't just ridiculous; they're monuments to sanctimony. If architecture is frozen music, these places are congealed piety, demonstrating with embarrassing concreteness the glaring hypocrisy of upper-class environmentalism.”

Many conservative commentators appeared reasonably confident that the accumulation of lifestyle hypocrisy—especially in its most spectacular, virulent manifestations—would eventually collapse the climate alarmists' house of cards. Washington Post columnist Rogers (2013) explained the decline in the number of Americans seeing global warming as a serious problem as an effect of climate hypocrisy: “People notice that those who preach the loudest seem disproportionately to fly in private jets, sleep in mansions, float on yachts and otherwise [have] lifestyles that produce high levels of carbon emissions.”

But the target of conservative attacks on climate hypocrisy was not solely on individuals. In fact, our analysis reveals the existence of a second, powerful type of conservative climate change hypocrisy discourse. This type—which we term the “institutional cynicism” mode–focuses on the vice of institutional hypocrisy, in which governments, corporations and other organizations make commitments which they are either unable or unwilling to fulfill. Surprisingly, this mode of conservative hypocrisy discourse was just as widespread as individual lifestyle outrage discourse. Where individual lifestyle hypocrisy was primarily driven by the narcissism of environmentalists, the origins of institutional hypocrisy lay in the ideological hegemony of environmentalism, combined with the impossibility of contemporary political systems responding to its ideological claims with anything other than superficial and contradictory responses. The inescapable result of such discourse is to magnify skepticism and cynicism about the prospects of institutional action on climate change as even those with the best intentions will, ultimately, find their efforts severely constrained.

The most conscientious exponent of this view was Peter Foster, a fiercely pro-market business columnist for Canada's The National Post, and the most prolific author in our sample. His most consistent and penetrating criticisms were reserved for the “suicidal hypocrisy” (Foster, 2009a) of “enlightened” corporate and government leaders who pay symbolic homage to the dictates of sustainable development and corporate social responsibility, blithely ignorant to how these toxic ideas not only threaten the profitability of their own companies and countries but threaten the normative and economic foundations of capitalism itself. Foster invokes hypocrisy as a convenient if unorthodox means of raising the alarm about the misanthropic ideology that so many were (unwittingly) endorsing in their embrace of the key tenets of environmentalism. In a lengthy and strident polemic against Ray Anderson—an outspoken CEO who attracted considerable attention for strong comments about the destructive ecological impacts of capitalism in the documentary The Corporation—Foster (2005) condemns the carpet manufacturer's hypocrisy in allying himself with environmentalists “who ultimately aim at not the reform but the destruction of the industrial system…Anderson's real sin may be that he has become what Lenin called a “useful idiot,” blithely peddling ideas whose dangerous or even disastrous implications he–like most people–simply doesn't understand.” Such contradictions were especially stark in the realm of climate and energy politics given that paying heed to “IPCC science would indeed demand the end of industrial civilization as we know it” (Foster, 2010). “Climate change policy hysteria,” he wrote in a 2009 column, “has led to a weird combination of schizophrenia and hypocrisy” (Foster, 2009b). US Energy Secretary Steven Chu, a “full blown climate alarmist who has supported draconian measures to enforce emissions reductions [is now calling] for moderation on oil prices, lest a continued spike harm economic recovery. Does he not grasp that the alleged threat of climate change cannot possibly be “addressed” without US $300-a-barrel oil …?”

As the focus shifts to the institutional level, the effect of this type of conservative hypocrisy discourse becomes less one of cultivating outrage, and much more one of engendering a cynical fatalism. On the one hand, this institutional hypocrisy arises out of the failure of political and corporate elites to attend to the true costs required to deliver on idealistic promises to address climate change. On the other hand, Foster simultaneously positioned hypocrisy as inevitable in an ideological landscape in which the tyranny of political correctness now forces all governments and many corporations to pay lip service to climate alarmism even as they (secretly) realize the impossibility of acting upon these commitments. By mid-2015; Foster (2015) was even counseling hypocrisy as a prudent and necessary strategy for politicians to adopt in global climate negotiations: “the main thing for skeptical governments (although they cannot admit being skeptical) is to continue playing the hypocritical game until it becomes glaringly obvious that the climate emperor has no clothes.” Likewise, in the final days of the John Howard government, columnist Kelly (2007) in The Australian, argued the necessity to sail with the climate change winds:

Howard's policy conversion is driven by his head, not his heart. This is not a road-to-Damascus conversion. Unlike St Paul, John has not become a believer. He accepts neither the moral crusade nor the apocalyptic science. “The world is not going to come to an end tomorrow because of climate change,” he said on Sunday, determined to distance himself from the believers. Howard knows the politics of climate change is riddled with hypocrisy.

The implication, of course, is that had Howard realized sooner, he may have saved his fortunes from the rise of climate-friendly Kevin Rudd. In a clever bit of discursive jujitsu, political hypocrisy is not only normalized but inverted as a signifier of smart leadership under difficult circumstances. The fault lies not with those faithless politicians who break their promises, but with the hysterical fearmongering of climate alarmists which has forced political leaders to serve up comforting but irrational platitudes about emissions reductions which any reasonable observer can see are impossible to deliver. Foster's about-face on the virtues of hypocrisy speaks to a broader trend within conservative commentary which, notwithstanding its bluster and outrage, accepted and even celebrated hypocrisy as incontrovertible evidence that considerations of (economic) self-interest will always trump considerations of virtue. And many political columnists took particular delight in documenting the institutional failures of progressive governments to act upon their climate change commitments. “We wear Senator Brown's [leader of Green Party] criticism with pride” boasts the editorial board of The Australian in 2010 (Editorial, 2010). “We believe that he and his Green colleagues are hypocrites … The Greens voted against the emissions trading scheme because they wanted a tougher regime, then used the government's lack of action on climate change to damage Labor at the August 21 election.”

In fact, there was a peculiar confluence in the analyses offered by both pro- and anti-climate commentators when taking stock of the dismal failures to achieve meaningful reductions in emissions. For conservatives, however, such political hypocrisy was marshaled as cynical proof of the ultimate impossibility of ever addressing climate change – not because it is a fabricated problem (though many do hold this view), but because people (and, therefore, governments) are fundamentally unwilling to sacrifice their material prosperity and comfort. In a column entitled “Hypocrisy, thy name is Ontario,” Globe and Mail pundit Murphy (2006)–an outspoken climate denier and vigorous defender of the Canadian fossil fuel industry—contrasted the provincial government's overwrought response to actor Sean Penn smoking a cigarette in a Toronto hotel with its strident opposition to fuel emission standards that might jeopardize local auto plants (and associated jobs).

Fine a hotel for one star-lit cigarette, but welcome the manufacture of thousands of environmentally retrograde muscle cars. And promise not to “abide” any effort to “unduly impose greenhouse gas reductions.” This is a parable of the entire global warming debate. Those who accept the science of the climate-change projects, who profess to be the most anxious over the “greatest crisis” of our times, will say every right word, and pursue the most trivial acts of symbolic environmentalism. But when it comes to action that has any real cost—political or personal—they are as hard-line an opponent to any change in the status-quo as the most relentless climate skeptic (Murphy, 2006).

Writing for the Washington Post, Samuelson (2005) was among the most ardent champions of cynical hypocrisy as the master-narrative for government inaction. “Almost a decade ago I suggested that global warming would become a “gushing” source of political hypocrisy. So it has. Politicians and scientists constantly warn of the grim outlook, and the subject is on the agenda of the upcoming Group of Eight summit…But all this sound and fury is mainly exhibitionism—politicians pretending to save the planet. The truth is that…they can't (and won't) do much about global warming.” Why? Because to lower emissions governments “would have to suppress driving and electricity use; that would depress economic growth and fan popular discontent. It won't happen.” (Samuelson, 2005).

Here, at last, we arrive at the prime (non) mover of institutionalized hypocrisy: voters, consumers, the middle-class, the public, ordinary people, you and I–we are all climate hypocrites in one form or another. The ocular and disciplinary valence of hypocrisy is reversed from spotlight (illuminating the sins of others) to mirror (revealing our own mass complicity). “The people on my street are conscientious and socially aware,” observes Wente (2005) in Canada's Globe and Mail. “They are proud to be Canadian and care a lot about the environment. Many of them even voted NDP.” And yet they are also utterly indifferent to “the one ton challenge,” a government campaign promoting behavioral change. “There's an SUV in almost every driveway. Nobody has given up her car to bike or walk to work…Sure, we all recycle…But give up our SUVs? Are you kidding? On Kyoto, we're all hypocrites. We think sacrifice is fine for everyone but us.”

Wente's collective admission of culpability is not intended to inspire deeper levels of reflexivity about how we might begin to address the contradictions between our values and our behavior. Instead, it aims to lift those contradictions beyond our reach, encasing them in the inescapable routines of everyday life, the unassailable common sense that humans are creatures of self-interest, and that that interest is expressed “naturally” via the carbon-producing actions of driving and flying, cooking, heating, and cooling. Consumer sovereignty (and market fundamentalism) begets climate fatalism: in a world in which governments, politicians, industries, and corporations have no choice but to dance to the tune of the market, hypocrisy ensures that the prospects for genuine action to address climate change are indeed thin. In the end, then, opponents of climate action have a love-hate relationship with hypocrisy: seemingly outraged with its ubiquity among liberal elites, they also confidently endorse it as evidence of the merits and reality of their worldview.

Progressive Formations of Climate Hypocrisy: From Politics to Lifestyle and Back Again

We turn now to the two distinct progressive formations of climate hypocrisy discourse. Much like conservative critics target individuals whose actions fail to live up to their commitments, the first version of progressive hypocrisy discourse attacks institutions and politicians that profess a desire to address climate change while cleaving to “business-as-usual” decisions and policies. Unlike smug conservative endorsements of institutional hypocrisy as realpolitik, however, progressive criticisms are generally leavened with constructive and often pragmatic accounts of how institutions and political actors could make different decisions–in an attempt to drive action rather than resignation or cynicism. We therefore conceptualize this type of hypocrisy discourse as a progressive “institutional call to action” mode.

A second type of progressive hypocrisy discourse–one we call a “reflexive” mode—goes beyond simply pointing out the failures of institutions to live up to their own rhetoric. Rather than reifying the divide between structural and personal agency (i.e., asserting that responsibility predominantly lies either with individuals or institutions), the most sophisticated progressive accounts trace their interdependence, exploring how collective political practice and individual behavioral change are necessarily entangled. Such accounts open up the possibility for a more reflexive relationship with climate hypocrisy, generating (rather than shutting down) conversations about how individuals and communities can take action to address climate change amidst recognition of the gap between ambition and action at the personal level.

We begin with the first “institutional call to action” mode. In much the same way that the lifestyle hypocrisy of Gore and other celebrities served as the dominant target for conservative discourse, the contradictions between political rhetoric and government policy dominated progressive accounts of climate hypocrisy. Such accusations often appeared in news items, attributed to environmental groups or opposition politicians trying to embarrass governments or mobilize opposition to particular policies and infrastructure.

Angry at what they say is government hypocrisy about climate change, groups like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth are framing the fight over the third runway [at Heathrow Airport] as a critical test of global efforts to stem the trend toward ever bigger airports and ever more flights.…“We want to highlight the inherent contradictions between having a supposedly progressive climate change program on the one hand, and on the other hand pushing forward plans to lock Britain into high emissions for decades to come' [a Greenpeace spokesperson] said (Lyall, 2008).

Guardian columnist Monbiot (2009) noted that public outrage over institutional hypocrisy is an emerging driver of political activism around climate change. “The Scottish government boasts of stringent targets to cut emissions while squeezing North Sea oil reserves and approving new opencast coal mines. No wonder people are taking into their hands to highlight this hypocrisy. It's the same everywhere. Governments are simultaneously seeking to minimize the demand for fossil fuels and maximize the supply.” Similar sentiments cropped up throughout our sample. The charged terrain of hypocrisy offered a convenient and newsworthy hook with which to publicize and indict government double-talk around climate and energy.

Governments were hardly the only targets of moral opprobrium. The Guardian, in particular, made ample use of the hypocrisy frame to draw attention to the hypocritical behavior of a number of prominent public agencies and institutions. Such targets included the World Bank for continuing to fund coal-fired power plants while stating that 4°C of global warming “simply must not be allowed to occur” (Sheppard, 2012), as well as the BBC and Oxford University, the former for its failure to adopt environmentally sensitive policies while cultivating a “high moral tone” around climate change (Deans, 2007) and the latter for accepting funding from Shell for an earth sciences laboratory (Adams, 2013).

At one level, there was a striking descriptive convergence of conservative and progressive accounts of institutional hypocrisy around the shared truism that most governments have been exaggerating their intent to tackle climate change while largely continuing with business-as-usual. But the diagnostic and normative implications of this assessment diverged sharply depending upon ideological worldview and orientation to climate change. Where conservative commentators cite institutional hypocrisy as evidence of the public's refusal to countenance real action, progressive accounts tend to use it in a much more targeted fashion, singling out particular politicians, and governments for specific decisions and policies: approving a third runway at Heathrow, subsidizing the Alberta oil sands, blocking the sale of uranium to India, expanding fossil fuel mining and infrastructure, and so on. In much the same way that conservative attacks on behavioral hypocrisy rest upon the assumption that individuals have real choices about their lifestyle, progressive accusations of institutional hypocrisy depend upon the belief that governments have real choices when it comes to climate and energy policies and regulatory decisions. As such, the analytic and rhetorical strength of progressive criticisms often depended less on highlighting the failures of institutional (in)action and more on making the case that a different course of action was indeed possible.

In the Guardian pieces described above on financing carbon-intensive infrastructure, for example, condemnation of the lending practices of specific institutions was paired with demands for simple, practical changes. “It is imperative that the EIB revises its energy policy in line with climate science, as well as with EU 2050 climate objectives,” said Anna Roggenbuck, Bankwatch EIB coordinator. “The EIB should immediately stop lending to coal … and develop and implement a plan to phase out lending to other fossil fuels and prioritize energy efficiency as the most important area of intervention.” (Cited in Carrington, 2011) Lamenting the Canadian government's hypocrisy on climate change, Globe and Mail business commentator Reguly (2007) similarly balanced criticism of institutional failure with a discussion of the regulatory, policy, and infrastructure levers which could be mobilized to achieve substantial emissions reductions. “No one said fighting climate change will be easy or cheap or non-threatening to cushy Canadian lifestyles. But a range of relatively easy and sensible programs could be put into place without ripping the economy apart. Adopting any one of them would make the politicians look like adults. And wouldn't that be nice for a change?” Tougher regulations around energy efficiency: “higher standards could be applied to fuels, building codes, manufacturing and autos.” Shift freight from truck to rail. Invest in mass transit rather than road-building. Subsidized retrofits for low-income households.

If emphasizing the autonomy of governments and other institutions to act more aggressively on climate change was a key theme of progressive accounts of climate hypocrisy, excavating the structural determinants which limit the capacity of individuals to change their own behavior was also a key feature of this discourse. Such explanations helped mitigate conservative accusations of lifestyle hypocrisy, but, more importantly, challenged cynical narratives which sought to naturalize hypocrisy as an inescapable feature of the human condition. Compare, for example, the Wente column discussed above with a lengthy op-ed from Canadian pollsters Michael Adams and Neuman, 2006. The latter piece begins by noting that environmental issues have become a priority for the Canadian public, describing it as akin to a “secular religion” which “asks people to suppress their egotism and say, “I will make this sacrifice.” “But, Adams and Neuman continue, “like religion, the imperatives of environmentalism can be sufficiently demanding that we sometimes believe in them more than we actually adhere to them”: rising levels of per-capita energy and resource consumption, the popularity of SUVs and large volumes of household waste all contradict the public's ostensible “eco-pieties.” For commentators such as Wente, this is the endpoint of their analysis: behavior always trumps values as an index of what people really think, feel and want. For the pollsters, however, the story is more complicated. “Are Canadians hypocrites who talk a good game but in the end do not really care about the Earth? We think not. Like righteous souls in a fallen world, Canadians are doing their best but encounter obstacles in their efforts to act green.” Suburban patterns of development lock individuals into energy-intensive lifestyles. Ad-driven media relentlessly promotes the virtues and pleasures of consumption. And, most important, there is an ongoing tension between our roles as citizens (with a “collective interest in a sustainable future”) and consumers (with “desires that our consumer society encourages us to see as needs”). Without excusing the role of individuals in pursuing behavioral change, Adams and Neuman posit civil and political society as essential partners in such a shift. The public “cannot walk the narrow path of ecological righteousness alone. Canadians will look to government, institutions and the private sector for active and visible leadership.”

This is not to say, however, that the principal thrust of such accounts was to deny, deflect or obfuscate personal culpability for environmentally irresponsible behavior. To the contrary, the most distinctive and visible contribution of progressive discussions of climate hypocrisy was a reflexive and often confessional account of the personal struggles that environmental advocates of all kinds experience in grappling with the contradiction between values and behavior in contemporary society. If the principal goal of conservative accusations of hypocrisy is the production of shame, guilt and, ultimately, silence (on the part of hypocrites), these highly reflexive accounts of hypocrisy have the opposite objective, namely, to open up new ways of discussing an issue that is generally difficult, awkward and uncomfortable to think and talk about.

This, then, is the second distinctive progressive type of hypocrisy discourse—the “reflexive” mode. Rather than denying or minimizing charges of hypocrisy, the most productive explorations of climate hypocrisy were often predicated upon a frank and honest acknowledgment of guilt on the part of those who were not only aware of the contradictions between their values and behavior but were willing to assume responsibility for them. For many of these pieces, the narrative arc followed a familiar trajectory starting with awareness, leading to responsibility and ultimately culminating in some form of behavioral change. Intent on generating discussion about the morality of flying, for example, The Telegraph (UK) profiled journalist Nicholas Crane: he “was a travel writer for 20 years, which meant he spent the better part of two decades jetting around the world. But following a particularly harrowing lecture at the Royal Geographical Society on global warming, he decided that his actions were damaging the environment. Wracked with guilt, he saw only one solution: give up flying.” While the devastating impacts of air travel are well established, “we're all flying more, thanks in no small part to the low-cost carriers…Perhaps we should be avoiding long-haul destinations and sticking instead to trains and cars and bikes.” (Kellett, 2006) While these types of stories often rehearsed well-worn stereotypes of environmentalism as (personal) sacrifice, they almost never adopted the moralizing, self-righteous, judgmental tone caricatured by conservative critics. Instead, items tended to privilege anxiety, introspection, and self-doubt, but also celebrated the genuine satisfaction that arises out of “walking the walk.”

Not unexpectedly, discussions of how to address and mitigate concern about hypocrisy often prioritized strategies of individual behavioral change with a focus upon adjusting one's lifestyle and consumer choices. The most interesting and provocative explorations of climate hypocrisy were those which simultaneously accepted the claim that individuals do bear (some) responsibility for their carbon-intensive behavior (rather than simply deflect such claims to structures and institutions) but then challenged the assumption that such responsibility is best (and solely) discharged through consumer action. In particular, such reflections troubled conventional distinctions between public and private—between consumer and citizen—that otherwise structure discourse about hypocrisy. Rather than privilege one sphere or subjectivity over another (for example thinking of ourselves primarily as either consumers or citizens), taking climate hypocrisy seriously both demands and enables novel conceptions of responsibility, efficacy and agency that cut through and across these distinctions.

“It's time to accept your inner hypocrite and take action all the same.” So ends a provocative Guardian op-ed from Fauset (2006) in a call for those concerned about climate change to become politically engaged and, more specifically, attend the annual “Camp for Climate Action,” an ecumenical gathering of UK activists to learn about climate change, discuss the transition to a low-carbon future and plan for direct action against major polluters. Her opening line: “Do you think you're doing enough about climate change? No, seriously, who genuinely believes they've managed to craft themselves a lifestyle which is sustainable? Even the most “eco” people I have ever met—people who grow their own food, generate their own energy and don't fly—harbor guilty secrets about eating out-of-season avocados or have wet dreams about SUVs.” (Fauset, 2006) Everyone is, indeed, a hypocrite at some level—but the personal moral burden that accompanies such awareness is better resolved through collective, political action that aims at structural transformation.

A year later, The Toronto Star featured a piece which interviewed Climate Camp activists protesting the expansion of Heathrow about their own use of air travel. The piece afforded the activists an opportunity to reflect upon the relationship between politics, lifestyle and hypocrisy. One Canadian student studying at East Anglia, for example, admitted returning to British Columbia to visit family she had not seen in several years. “It was really, really hard. I struggled with the decision of whether or not to make the trip,” says [Alex] Harvey…“I missed my family. I hadn't been home in three years. So I went home” (Cited in Potter, 2007). The activist initially challenged the individualism embedded within the decision to frame the protest through the lens of hypocrisy: “The thing about asking when we last flew—I understand why you want to know, but I worry that it gives the impression our protest is about attacking people at the level of individual guilt. Because it's not. Foremost this is about highlighting government policies that, on one hand, want people to change to energy-efficient bulbs and on the other hand is hypocritically in favor of doubling air traffic to facilitate the binge flying of the super-rich (Cited in Potter, 2007).” But she acknowledged that her “guilt for having flown to Vancouver” also played some role in her politics. “There are no simple answers…But surely at least one part of the answer is to question a culture that has persuaded us we have to fly in order to be happy. This issue needs special attention. And that's why we are here” (Cited in Potter, 2007).

For some progressive columnists, hypocrisy is the inevitable byproduct of a moral and political worldview animated by aspirational values and ideals that go beyond self-interest and the defense of the status-quo. In a critique of British journalist Julie Burchill's polemic Not in My Name: A Compendium of Modern Hypocrisy—which singled out “posh” environmentalists as especially worthy of ridicule—Guardian columnist and climate activist Monbiot (2008) reasoned that critics such as Burchill were largely immune to accusations of hypocrisy: “she cannot fail to live by her moral code, for the simple reason that she doesn't have one.” For Monbiot and others, hypocrisy is a discomfiting but generative signifier of the desire to narrow the gap between is and ought and, therefore, at the very least it both reflects and sustains the possibility of a personal and political agency based upon something other than self-interest. “Sure, we are hypocrites,” he writes. “Every one of us, almost by definition. Hypocrisy is the gap between your aspirations and your actions. Greens have high aspirations; they want to live more ethically; and they will always fall short. But the alternative to hypocrisy isn't moral purity (no one manages that), but cynicism. Give me hypocrisy any day.” (Monbiot, 2008) In a similar vein, Zoe Williams (2014)–also a Guardian columnist–used the “outing” of a senior Greenpeace official as a serial air commuter to discuss the implicit ideological bias that shadows an obsession with exposing and condemning (lifestyle) hypocrisy.

The best way to never be a hypocrite, and to always stay consistent, is to deny climate change, and have no agenda on anything beyond self-interest…Indeed, the more ardently you pursue your own interests, the more persuasively you live your own values. If, on the other hand, you have ambitions for large-scale change and believe things could be significantly better for vast numbers of people, you will always fail fully to embody your own hopes (Williams, 2014).

The point is not to excuse or justify hypocrisy—which Williams admits is both disappointing and depressing—but rather to lay bare the cynical political strategy that so often lurks beneath the schadenfreude that dominates “gotcha environmentalism.” “Each time a potential “green hero” is shot down in flames,” observes author Lynas (2007), “we all feel that little bit more cynical about politicians, leaders and society in general. Cynicism breeds selfishness and a de facto acceptance of the status-quo….” Such analysis interrogates the perceived rhetorical (and ideological) effects—unwitting or otherwise—of hypocrisy discourse, shifting our attention from the (occasional) violation of moral and political principles to the sobering prospect of a public sphere evacuated of such principles altogether.

While such commentary draws attention to how an individualized discourse of climate hypocrisy often shelters more sinister forms of climate cynicism, even nihilism, the dismissal of such discourse as ideological propaganda leaves little room to consider the generative potential of hypocrisy to open up new ways for people to think about the relationship between personal responsibility, political agency, and climate change.

With characteristic aplomb, Bolt (2010) boils down the conservative critique of climate hypocrisy to a simple proposition: “If the planet really is threatened with warming doom, why don't you act like you believe it? In truth…the real question we must calmly consider: would each sacrifice we're told to make in fact make so much difference that we should make it?” The emphasis upon sacrifice, as noted above, presumes a privatized form of agency in which the only way we can “act like we believe it” is to change our lifestyle. Yet many if not most climate advocates share Bolt's skepticism about the ultimate efficacy of consumptive acts to mitigate climate change. As such, the core challenge for a progressive discourse of climate hypocrisy may lie in offering the public more expansive, persuasive, compelling, and political visions of how we might “act like we believe it” and scripts of civic agency (and collective action) which hold open the slim prospects of making “so much difference that we should make it.”

Conclusion

A growing emphasis upon the necessarily agonistic dimensions of climate change politics offers an essential rejoinder to an otherwise dominant “post-political” worldview that positions climate change as a shared threat to the common interests of all humanity (e.g., Swyngedouw, 2010; Machin, 2013). Instead, stock must be taken of the contradictory and often competing visions, interests and discourses—and the relations of power, political economy and inequality that anchor them—that catalyze starkly different conceptual and affective responses to the climate crisis.

We have shown that climate hypocrisy discourse is an increasingly potent site through which such divisions are enacted and performed—and should be understood as such. Indeed, while acceptance or denial of climate science has attracted the lion's share of attention as the discursive fulcrum through which elites, media and individual citizens signify and reinforce their allegiance to warring climate tribes, we believe climate hypocrisy is increasingly performing a similar role—especially as the politics of climate migrates and diffuse into adjoining fields of energy, carbon, and extractivism (e.g., Schneider et al., 2016). A recent examination of “extractivist populism” in Canadian social media, for example, identified the dismissal of environmentalists as elitist hypocrites to be among the most common rhetorical strategies of those promoting the interests of the fossil fuel industry; climate denial, in contrast, was almost entirely absent from such discussions (Gunster et al., forthcoming). Even the most cursory review of online and offline debates about the myriad politics of carbon likewise finds a discursive field riddled with often passionate accusations of hypocrisy. And though such accusations continue to be most visibly (and fiercely) levied against advocates of climate action, the language of hypocrisy is also increasingly marshaled to indict politicians and governments that promise to act but deliver the status-quo. Talk of climate (and energy) hypocrisy, in other words, furnish competing heuristics that enable us to make sense of climate change (and our evolving relationship to it) in very different ways. More importantly perhaps, such talk simultaneously gathers and disperses the affective energies that lead individuals–again, in very different ways–to care deeply about some forms of climate morality and agency while marginalizing and dismissing others.

Talk of climate hypocrisy, then, is not simply cheap rhetorical spin burnished by industry shills and political hacks (although the role of such public relations strategies is an essential part of the picture). Overall, it is a sign of something more important. Calling for a (re)politicization of climate change, Pepermans and Maeseele (2014) advocate discursive strategies that reveal “competing sets of epistemic assumptions, policy choices, values, and interests underlying opposing responses to uncertainty, and relate these to underlying alternative visions of society, which are subsequently made the subject of public debate” (p. 224). Climate change, they argue, must become “an object of democratic debate between conflicting, yet legitimate, social actors, or more specifically, politico-ideological conflict between alternative futures” (p. 224). Such discussions of politicization and climate agonism invariably frame such conflict in melodramatic terms (Schwarze, 2006), that is, as social and political conflict between particular institutions, coalitions and forces (e.g., corporations vs. social movements; the fossil fuel industry vs. local communities; neo-liberals and the far right vs. social democrats and democratic socialists). Given the hegemonic thrust of what Mann and Wainwright (2018) have provocatively described as “Climate Leviathan”–a nominally ecological form of planetary sovereignty primarily designed to safeguard capitalist structures, institutions and elites—such melodramatic forms of polarization are more necessary than ever to inform and mobilize citizens around much broader, diverse and democratic visions of climate justice. Our analysis suggests that criticisms of institutional climate hypocrisy offer an important contribution to this rhetorical and political endeavor.

Attention to climate hypocrisy, however, reminds us that the agonistic dimensions of climate change also exist within individuals themselves. Competing values, practices and, above all perhaps, visions of a good and ethical life animate an inner conflict that pits a contemporary habitus founded upon cheap and accessible energy against the urgent need for decarbonization. As we have argued, the most interesting, provocative and generative accounts of climate hypocrisy challenge the comfortable but simplistic attribution of culpability and agency to one or the other side of the divide between public and private, that responsibility for action belongs only with institutions or individuals. In an era rife with fantasies of individualization (Maniates, 2001), sober reminders about the structural power of capitalism–as mediated through governments, corporations and other institutional actors–and its relentless cultivation of carbon intensive forms of social life offer a critical rebuttal to conservative accounts that inflate the political significance of behaviors and lifestyles that, for the most part, are not chosen in any meaningful sense of the word. And yet developing fuller and more resilient narratives of (re)politicization surely demands that such interventions serve as the beginning rather than the end of conversations about what we are to do (rather than what is to be done by others) about climate change. What studying climate hypocrisy ultimately helps underscore is how climate politics is not a matter of either focusing upon changing systems or lifestyles but instead involves understanding that system change and the transformation of individual subjectivity and collective practice are deeply intertwined and interdependent.

Talk of hypocrisy has become an inescapable, if often repressed, aspect of climate change discourse. We believe that it will only continue to grow in prominence and resonance as societies grapple with the possibility, necessity and impacts of transition. While it may be tempting to dismiss or ignore such talk as little more than rhetoric designed to shore up neo-liberal (de)formations of political subjectivity, we believe that a more substantive and robust engagement with climate hypocrisy is essential—if only to deal with the threat that conservative hypocrisy discourse poses to climate advocates' ability to build support for climate action. We believe, however, that the need to engage with climate hypocrisy discourse goes beyond this “defensive” justification. For as we have also shown, the affective resonance of climate hypocrisy can cut both ways: frank recognition of the hypocrisy of those who possess environmental sympathies can open up space for understanding the structural forces that generate the gaps between intention and action and thus promote a more complex understanding of the relations between social and political change and individual practices. Embedded within reflexive, sympathetic and dialogic venues of communication, the (often uncomfortable) feelings that attend such recognition can become a spur to reflection, conversation and, most importantly, modes of agency and action that dismantle (rather than enforce) conventional liberal distinctions between public and private, political and economic, citizen and consumer.

Engaging with hypocrisy discourse, in other words, might both help us to blunt the attack of those seeking to stall climate action and help us intensify positive affective commitments to climate action. While the affective terrain of climate hypocrisy may currently appear to be dominated by those seeking to foreclose climate action, their hold is not guaranteed. Bold, creative and honest engagements with climate hypocrisy that sustain (rather than abolish) the tension between individual agency and structural critique may help inaugurate and strengthen the imperfect yet innovative forms of climate politics the Anthropocene demands.

Author Contributions

All authors designed the study. DF collected the newspaper sample. SG analyzed the sample and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SG, MP, and DF drafted the introduction and conclusion. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, under a grant entitled the Cultural Politics of Climate Change, number 435-2014-1237.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adams, R. (2013, May 9). Universities protest at Shell funding for laboratory at Oxford. The Guardian.

Anderson, A. (2011). Sources, media, and modes of climate change communication: the role of celebrities. WIREs Clim. Change 2, 535–546. doi: 10.1002/wcc.119

Attari, S. Z., Krantz, D. H., and Weber, E. U. (2016). Statements about climate researchers' carbon footprints affect their credibility and the impact of their advice. Clim. Change 138, 325–338. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1713-2

Barr, S. (2011). Climate forums: virtual discourses on climate change and the sustainable lifestyle. Area 43, 14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2010.00958.x

Boykoff, M. T., and Goodman, M. K. (2009). Conspicuous redemption? Reflections on the promises and perils of the ‘Celebritization’ of climate change. Geoforum 40, 395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.04.006

Carrington, D. (2011, December 9). European Investment Bank criticized for ‘hypocrisy’ of fossil fuel lending. The Guardian.

Cooper, G., Green, N., Burningham, K., Evans, D., and Jackson, T. (2012). Unravelling the threads: discourses of sustainability and consumption in an online forum. Environ. Commun. 6, 101–118. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2011.642080

Dannenberg, C. J., Hausman, B. L., Lawrence, H. Y., and Powell, K. M. (2012). The moral appeal of environmental discourses: the implication of ethical rhetorics. Environ. Commun. 6, 212–232. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2012.668856

Eckersley, R. (2013). Poles apart?: the social construction of responsibility for climate change in Australia and Norway. Aust. J. Politics History 59, 382–396. doi: 10.1111/ajph.12022

Editorial (2010 September 9). Day one and confusion reigns already within Canberra's coalition of convenience. The Australian.

Elsworth, C. (2007a, February 28). Al Gore faces inconvenient truth about his own energy use. The Daily Telegraph [UK].

Elsworth, C. (2007b, February 28). Truth indeed inconvenient for American activist. The National Post.

Foster, P. (2005, July 2). Heaven can wait: U.S. industrialist Ray Anderson sees himself as a corporate saviour, but his impact on his own company, Interface, is questionable. The National Post, FP17.

Gavin, N. T., and Marshall, T. (2011). Mediated climate change in Britain: Scepticism on the web and on television around Copenhagen. Global Environ. Change 21, 1035–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.03.007

Gunster, S., Fleet, D., Paterson, M., and Saurette, P. (2018). Climate hypocrisies: a comparative study of news discourse. Environ. Commun. 12, 773–793. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2018.1474784

Gunster, S., Neubauer, R., Bermingham, J., and Massie, A. (forthcoming). “‘Our oil’: extractive populism in Canadian social media,” in Regime of Obstruction: How Corporate Power Blocks Energy Democracy, ed. W. Carroll (Athabasca, AB: Athabasca University Press).

Gunster, S., and Saurette, P. (2014). Storylines in the sands: news, narrative, and ideology in the calgary herald. Can. J. Commun. 39, 333–359. doi: 10.22230/cjc.2014v39n3a2830

Höppner, C. (2010). Rereading public opinion polls on climate change in the UK press. Int. J. Commun. 4, 977–1005.

Knight, G., and Greenberg, J. (2011). Talk of the enemy: adversarial framing and climate change discourse. Soc. Move. Stud. 10, 323–340. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2011.614102

Laidley, T. (2013). Climate, class and culture: political issues as cultural signifiers in the US. Sociol. Rev. 61, 153–171. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12008

Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S., and Whitmarsh, L. (2007). Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environ. Change 17, 445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.01.004

Machin, E. (2013). Negotiating Climate Change: Radical Democracy and the Illusion of Consensus. New York, NY: Zed Books.

Maniates, M. (2001). Individualization: plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Global Environ. Politics 1, 31–52. doi: 10.1162/152638001316881395

Mann, G., and Wainwright, J. (2018). Climate Leviathan: A Political Theory of Our Planetary Future. New York, NY: Verso.

Marshall, G. (2014). Don't Even Think About it: Why Our Brains are Wired to Ignore Climate Change. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Mayer, F. W. (2012). Stories of climate change: competing narratives, the Media, and U.S. public opinion, 2001–2010. Discussion Paper, Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, 47p.

McCrann, T. (2014, November 15). Earth to journalists: this climate deal is irrelevant. The Australian.

McGregor, C. (2015). Direct climate action as public pedagogy: the cultural politics of the camp for climate action. Env. Polit. 24, 343–362. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2015.1008230

Monbiot, G. (2008, August 6). I'd rather be a hypocrite than a cynic like Julie Burchill. The Guardian.

Monbiot, G. (2009, August 8). Scottish climate policy is hypocritical, contradictory and counter-productive. The Guardian.

Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262015448.001.0001

Pepermans, Y., and Maeseele, P. (2014). Democratic debate and mediated discourses on climate change: from consensus to de/politicization. Environ. Commun. 8, 216–232. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.906482

Platt, R., and Retallack, S. (2009). Consumer power: How the public thinks lower-carbon behavior could be made mainstream. Institute for Public Policy Research, 47p.

Reguly, E. (2007, February 3). My simple eco-list to make Canada a greener nation. The Globe and Mail.

Rogers, E. (2013, April 11). The Insiders: Democrats' lost momentum on climate change. The Washington Post.

Schneider, J., Schwarze, S., Peeples, J., and Bsumek, P. (2016). Under Pressure: Coal Industry Rhetoric and Neoliberalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schwarze, S. (2006). Environmental melodrama. Quart. J. Speech 92, 239–261. doi: 10.1080/00335630600938609

Song, L. (2016, June 23). Climate scientists' personal carbon footprints come under scrutiny. Inside Climate News. Available online at: https://insideclimatenews.org/news/23062016/climate-scientists-say-practicing-what-they-preach-helps-credibility-global-warming-carbon-footprint.

Swyngedouw, E. (2010). Apocalypse forever? Post-political populism and the spectre of climate change. Theor. Culture Soc. 27, 213–232. doi: 10.1177/0263276409358728

Van Velzen, A. (2007, December 6). Letter to the editor: Climate unmentionables. The Globe and Mail.

Watts, A. (2016, June 16). Study: ‘Climate scientists are more credible when they practice what they preach’ – but my aerial surveys show many don't. Watts Up With That. Available online at: https://wattsupwiththat.com/2016/06/16/study-climate-scientists-are-more-credible-when-they-practice-what-they-preach-but-my-aerial-surveys-show-many-dont/.

Webb, J. (2012). Climate change and society: the chimera of behavior change technologies. Sociology 46, 109–125. doi: 10.1177/0038038511419196

Williams, Z. (2014, June 25). To target Greenpeace's flying director is to miss the point. The Guardian.

Yoder, K. (2016, June 21). People don't trust hypocritical climate scientists, study finds. Grist. Available online at: http://grist.org/climate-energy/people-dont-trust-hypocritical-climate-scientists-study-finds/.

Keywords: hypocrisy, climate change, ideology, news media, discourse analysis, individualism, climate politics