- School of Media, Communication and Sociology, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom

It is now recognized that industry representatives influence the news reporting of climate change. Still, debate continues over the form and the extent of their influence particularly in the absence of detailed analysis of their presence across time. This paper places industry in the frame by analyzing their perspectives within a period of rapid politicization of the issue in the UK (2000–2010). Mapped across elite reporting, industry presence appears to be fluid, not static, and to respond to the politicization of the issue and to the journalistic logic that shapes elite coverage. Perhaps as expected, industry is pro-active in providing a perspective on climate change as an economic problem and projecting its “green credentials” in prime positions across the reporting. Mostly, however, this reporting uses its reactions to comment on other industry or elite activities, practices and policy. The findings show that interactions between the media and the political context underpin the observed outcomes of the pro-active and the re-active public relations by industry, in addition to shaping the presence of other speakers that contribute to the complex issue of climate change.

Introduction

This paper addresses the important issue of climate change. For a long time there has been scientific agreement on the human causes of—anthropogenic—climate change, observations of changes in the climate, together with their ongoing impacts (e.g., storms and floods) and their future risks. At the same time there has been different levels of attention given to the issue at the national and international political levels and subsequent levels of action recorded in response to it. Revealed similarly are the different stakeholders and their attempts to influence the direction of climate policy alongside the publics' understanding of the wider issue. As part of this effort, stakeholders are observed to direct views, counter definitions or challenges to others' positions to the mass media with the intention to gain them greater visibility and to influence others. Representatives from industry (including the fossil fuel industries) are a group that have attracted the attention of media researchers in this regard.

Studies discuss how representatives from industry (i.e., corporations, think tanks etc.) maintain an important place within media discussions of climate change. Industry is seen to obtain privileged opportunities to shape news discussions and to defend their actions (see Hansen, 2011). Often pro-active public relations are used in this effort to neutralize potential criticisms that would prove harmful to their interests (Lester, 2010) for instance. Tactics include the promoting of a perception of industry activities as environmentally friendly (Lyon and Montgomery, 2015) and a disguising of their views as those emerging either from grassroots organizations or those from other (pseudo) companies. The most disturbing outcomes from the latter activities have been the use of disguised platforms, by oil companies, to launch attacks on environmental concerns, environmentalists and most recently on climate scientists (Monbiot, 2007; Gaither and Gaither, 2016). Reaffirmed here is a view of pro-active industry representatives who wield the authority to define how the media report their views (Hall et al., 1978) or, at the least, to maintain a discursive advantage within relevant media discussions.

Elsewhere industry is observed to perform more fluid, less static, roles in news coverage however and to be more re-active than pro-active. Participation in reporting is less rigidly prescribed in the first instance (Carpenter, 2001) and industry performances, like those of other elite voices, are understood to be shaped within the context of the developing issue (see Ihlen, 2009). Differences emerge in the reactions to climate change from industry. Included are more positive responses observed from those spaced in different geographical zones (i.e., European vs. US companies—Levy and Newell, 2000), and within sectors (i.e., Texaco-chevron vs. Exxonmobile in the oil industry sector—Skjærseth and Skodvin, 2003), for example. Industry representatives also respond to the evolving politicized issue found within specific national regulatory regimes (Schlichting, 2013), in addition to pro-actively offering frames that reflect their perspectives within them (Wilkins and Patterson, 1991; Carpenter, 2001). As a result, their participation in the issue is more varied than the explicit or the implicit critic of anthropogenic climate change or one that champions their interests and advantages that has been observed previously (Ihlen, 2009; Zehr, 2010). In responding to this discussion, and being mindful of the accelerated growth of this reporting through the 2000s in the UK, this paper asks how does industry perform in UK reporting and what factors shape those performances?

Industry, Frames, and Climate Change

The reporting of an issue and the voices used within it emerge, in part, from a process of issue politicization. Through interaction, different stakeholder groups develop the politicization process, and in the case of climate change, one that is characterized by discussion of risks and outcomes (Strydom, 2002). In reality, climate change has become an object of governmental efforts to publicly manage the issue in addition to other political reaction to it (Beck, 2009; Olsson, 2009) including reactions from interest groups (Cox and Schwarze, 2015), industry and other stakeholders (Ihlen, 2009; Zehr, 2010). These observations are pertinent to the UK as this paper will later demonstrate. As a consequence, news reporting reflects the outcomes from these activities and in the process takes a measure of the importance (i.e., newsworthiness) that can be ascribed to the issue. Within stories, the patterning of prominent issue frames is made visible together with the positions from which the issue is being discussed or what Hallin (1985) describes as either a sphere of “consensus,” or “legitimacy controversy” or “deviance.” Exploring the positioning of the issue can help to understand the role played by industry commentary.

Studies of the evolving coverage of climate change have located the performance of industry within it. In the 1980s, for example, industry featured between the dominating frames of science and politics that defined the problem and offered justifications, and remedies, for it (Trumbo, 1996). From this position, they offered insight into potential “technological fixes” to the then “global warming” problem (Wilkins and Patterson, 1991). Later their presence evolved with the issue as it gained an international dimension. For example, industry has been described as benefiting from a change in the legitimate presentation of climate science in reporting. Coverage, particularly in the US, included an increased presence of skeptical positions on anthropogenic climate change in the 1990s (Antilla, 2005) which reflected the agenda of the fossil fuel industry. While some legitimate and important “maverick type” scientists (Tøsse, 2013) expressed these positions, others were suggested to be in the “indirect” employ of industry.

Monbiot (2007) has been particularly outspoken on the use of front-organizations as part of the activities of oil industries to shape debate. Indeed, these claims follow an established academic interest in industry public relations on green subject matters. Research has not only explored industry attempts to make connections between their activities and environmental images and ideas (or “greenwashing”—Walker and Wan, 2012) but this has also recognized the measures untaken to deal with presumed “crises.” This is revealed in industry's reactive stance to environmental disasters (Wickman, 2014) and their more recent proactive engagement in relevant public debates. Monbiot (2007) charts the latter, and the industry efforts from what he terms, “Exxon-sponsored deniers,” to question the evidence for climate change and more importantly from their perspective to reinforce the sense of a lack of scientific certainty in the minds of citizens. Likewise, Gaither and Gaither (2016) have studied how industry communications mobilize specific cultural values and mores to convince others that climate policy would hurt industry operations and, in turn, the everyday finances of the US citizen. Further, the spread of skeptical voices on climate change science to reporting outside of the US, is attributed to the increasing reliance of news organizations on news material produced by public relations activities (Beder, 2002; see also Lewis et al., 2008) and the operation of newsroom practices underpinned by established journalistic norms. Journalists desire to include scientific controversy as newsworthy (Nelkin, 1995) is recognized alongside their desire to “balance” voices in coverage as explaining the common presence of climate science skeptics (Boykoff and Rajan, 2007). However, the presence of explicit skepticism, despite the impression created by Monbiot, was on the retreat in the early 2000s (see Cottle, 2009) and developments in political framing have filled this space.

Thus, industry commentary has been recognized to follow the discussion of climate change as it has moved to an international level. It has reacted to the reported thoughts of intergovernmental scientific panels (e.g., IPPC) and those of other leaders speaking at international conferences (McManus, 2000; Gunster, 2011). Industry has voiced concerns about the social and the economic consequences of adopting mandatory polices to reduce greenhouses gases (Schlichting, 2013) in addition to commenting on international meetings that are framed by the contest and conflict between countries (Lockwood, 2010; Christensen and Wormbs, 2017). At the same time, it has been observed to inhabit different “imaginaries” on climate change rather than constructing objections or uncertainty over the issue in the media (Levy and Spicer, 2013). Elsewhere and domestically, climate change policy has been redefined by industry as an opportunity (Carpenter, 2001) within stories on carbon markets, environment/business coalitions and investment in green policy/technology (see Zehr, 2010). Often reproduced here is the position of the “economisation” of climate change and one that contrasts with previous offerings of straightforward “technological solutions” or criticisms (Carvalho et al., 2017). Inga Schlichting, in one of the most recent analyses of industry responses, argues that this approach can be defined as an “industry leadership frame” where “corporations acknowledge that they are (also) responsible for protecting the climate” (2013, p. 502). Furthermore, this response is more likely to be observed in environments where political elites are expressing similar sentiments. In the UK, for example, the Labour government has been forthright in addressing the climate change issue over the period 2000–2010. From 2006 onwards specifically, it engaged “in a radical transformation of climate policy” (Carter, 2018), including “the Climate Change Act, Low Carbon Transition Plan and other “progressive” policy measures on renewable energy, Carbon Capture and Storage, infrastructure planning, domestic energy efficiency and support for a renaissance of nuclear power” (ibid). Still, we know little about how the voices of industry contribute to discussions shaped in the UK political environment and by others' perspectives on the issue. “What contribution does industry make to a rapidly developing issue?” is a question that will be of direct interest to this paper, therefore.

In addition to recognizing the importance of the politicization of the issue for the place of industry in reporting, further insights for this emerge from examining the institutional processes and structures that shape journalists' efforts to mediate this “raw material” into news stories (see Anderson, 2014). Research describes how working to a 24 hour news cycle attunes journalists' attention to the announcements and the reports on climate change offered by significant institutions (Curtin and Rhodenbaugh, 2001). Similarly, the preference for event-led or unusual events or announcements serves often to deselect, rather than select, the “slow evolving” issue like climate change for the news agenda (Anderson, 2014). In addition, the geography of news outlets (regional vs. national) shapes what is reported and the types of news they produce. Climate change features in regional papers when it impacts on an identified “local” audience (for example Wakefield and Elliott, 2003). Distinctions are found also in national newspapers and these reveal that tabloid newspapers eschew political stories, like climate change, unless there are observable impacts on their readership (Matthews and Brown, 2012) and others adopt positions on the issue in their editorial columns (see Painter and Gavin, 2016).

Hence, news organizations select and present news on the basis of different news making ideas and practices, all of which demands then that we recognize their mediating properties (Hansen, 2010). Described recently as “journalistic logics,” these unique news identities explain the observed similarities and differences we find in the reporting of climate change (Matthews, 2016). Journalistic logic contains instructions on the preferred news agenda, stance and style of a news outlet and thus the differentiated news delivery it produces (Berglez, 2011). Logics reflect also the different market positions of news institutions (i.e., upper; middle; lower) and in application bring much needed complexity to a view of those formats assumed often to be shaping news reporting (see Altheide and Snow, 1991, for example). Those newspapers that reflect elite journalistic logic report the political and the economic dimensions of an issue and those voices pertinent to it, including industry. The use of an objectivist stance (rather than subjectivist, and at times partisan, stance enacted by lower market journalism) complements these elite news interests when reporting news and including voices. Elite journalists use objectivity and impartiality to bring a sense of credibility to their news writing and in turn to remove traces of their positions as authors. These practices lead often to reproducing the definitions and thoughts of prominent institutions on issues in their news coverage (Hall et al., 1978). Within stories that include perceived conflict there are attempts made to implement the journalistic norm of balance to reflect the different voices in the perceived “debate” (Boykoff and Boykoff, 2007). Such newspapers provide then ideal examples to explore how elite journalism reports the wider discussion of climate change and therein configures space for the perspectives and the voices of industry. In light of the specifics of the UK political context between 2000 and 2010 outlined above, this paper asks the following questions:

- How do the elite UK newspapers frame the climate change issue in their coverage (2000–2010)?

- What opportunities do industry voices receive to enter and speak in the framed coverage?

- What discursive roles do industry voices play in news stories of climate change and to which voices are they observed to engage?

Methods

The research on which this paper is based examined the construction of the issue of climate change in UK elite newspaper reporting and the opportunities it provided for industry voices. The research selected four UK elite newspapers (the Times, the Telegraph, the Guardian, and the Independent and their Sunday equivalents) for analysis. To ensure the research captured the continuities and differences across this reporting, it collected news outputs across a 10-year period. The dates (1st January 2000 to 31st December 2010) were selected to correspond with an appropriately large period and one flanked by changes including reported skepticism (before, 2000) and the onset of reporting of “austerity” in the aftermath of the financial crisis (after, 2010). The process to locate individual stories involved the use of Lexis-Nexis database and the search terms: (i) “climate change” and/or “global warming” as (ii) appearing in the headline and/or the main body of relevant stories. Thereafter, the study selected every tenth article from this amount to produce a workable representative sample of news content (for example see Boykoff and Boykoff, 2007). After cleaning for duplicates and non-relevant stories (including editorials, as these exclude voices that are external to news organizations), a sample of 1,379 stories were taken forward for analysis.

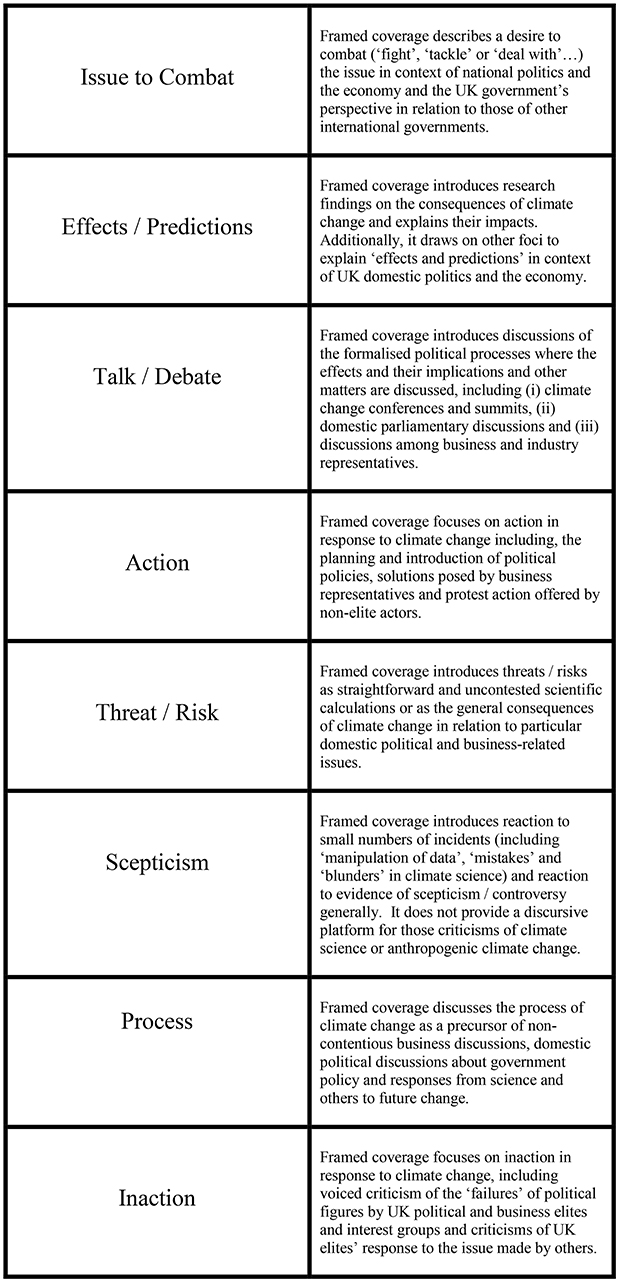

In response to the research questions, the study used content analysis to explore the frequencies of frames, voices and speaking opportunities (i.e., news entry and news roles) in the stories. The process to identify frames in the coverage involved a technique that explored relationships between language in the coverage (see Baker and McEnery, 2005) to capture how climate change was being discussed. To locate the individual frames in the coverage, the coder scanned the articles for the words “climate change” or equivalent (in the headline and/ or the main story) and the words proximate to it. These word patterns uncovered eight frames as prominent across the sampled coverage and a description of the eight frame categories is provided in Figure 1.

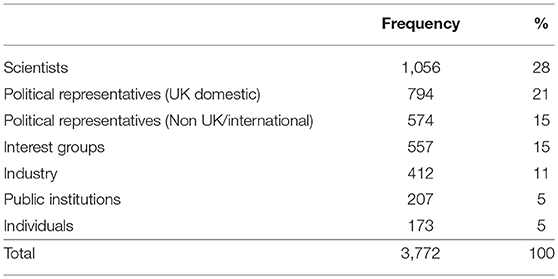

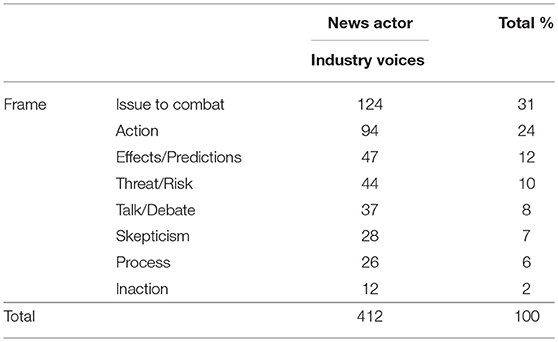

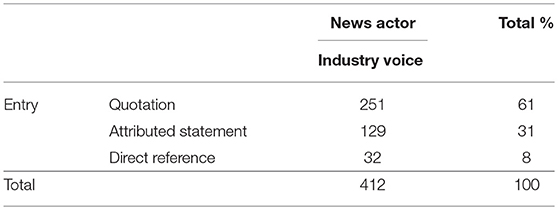

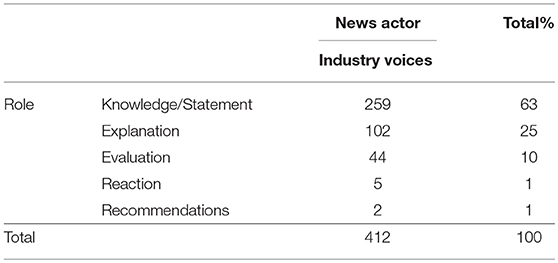

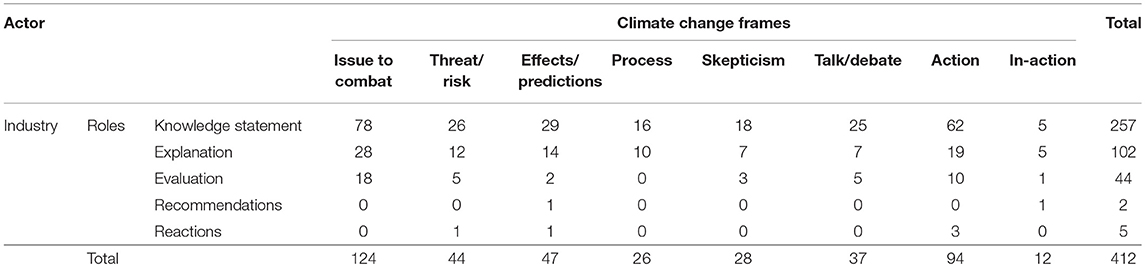

In addition to exploring the frames, the study used content analysis to examine the frequencies of speaking opportunities in the sampled stories. Having identified 3,772 voices in the first instance, the study placed voices within categories that later become seven identified groupings and included the category of industry (n = 412—see Table 1). The “industry” category included representatives from different forms of industry (include the fossil fuel industry) and the other positions linked to industry including: advisors, lobbyists, experts, think tanks, and interest groups. Analyzing the stories that featured the voices of industry, showed their development over time and the frames in which these performed. The analysis also explored the character of their performances. It analyzed the mode in which they accessed the story (i.e., news entry—see Table 3) in addition to the particular discursive roles they performed in the news stories (i.e., news roles—see Table 4). With the general activity of industry voices established, the study moved to explore the dynamics of voices within the coverage. First, a comparison between the framed coverage and the performed news roles was conducted to gain an insight into the industry performances in relation to news coverage (see Table 5).

Second, the study selected examples of coverage to explore the industry activity in greater depth. The purpose of the analysis was to provide answers to the question about the relationship between industry speakers and other voices in the coverage, in addition to a desire to illustrate the discussion of industry voices in the coverage generally. This process involving selecting and analyzing representative examples of industry activity within news stories, in particular forms in which their voices entered the news coverage as either: (i) news references, (ii) attributed statements or (iii) quotations. Additionally, the study analyzed the discursive roles that the voices performed in stories. Four possible performances were identified including, voices: (i) providing “reactions” in addition to the more legitimate news roles of (ii) providing “statements,” (iii) providing “explanations,” (iv) providing “evaluations” and (v) providing “recommendations” (see Cottle, 2000). What is more, a pilot study was conducted before the main period of the content analysis. This involved the activities of two coders and the analysis of 20 random articles. The pilot study confirmed the usefulness of the codes, the code book and the reliability of the coders' selections. Thereafter, the data was entered into a statistical package (SPSS) for further analysis of the relationship between news frames, news voices, news entry, and news roles. What follows will discuss the study's findings on the relationship between framing of climate change and the performance of industry speakers in elite newspaper coverage.

How Do the Elite UK Newspapers Frame the Climate Change Issue in Their Coverage (2000–2010)?

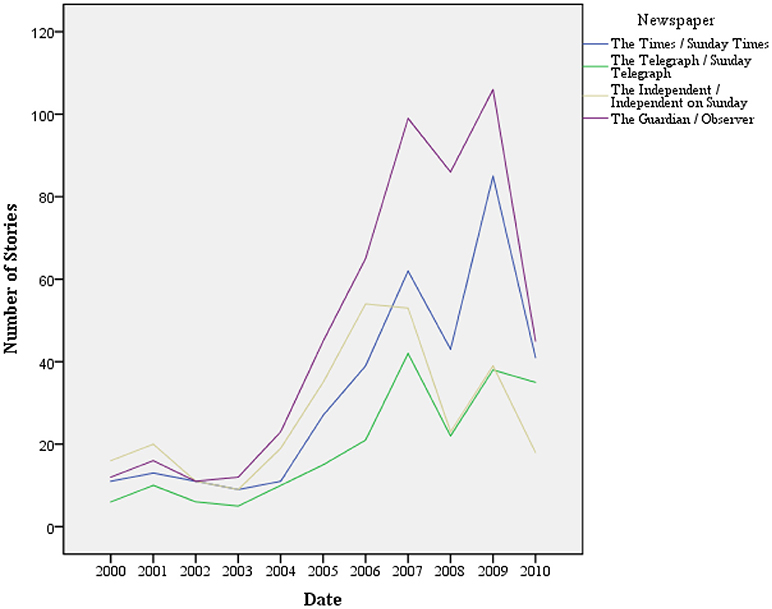

As has been explained, the performance of industry voices will be dependent on the reporting of climate change. The amount of attention this issue receives for example reveals its significance for the selected newspapers and in turn the space they offer for discussion of, and comment on, it. In illustrating the overall measurements of the coverage of the four chosen newspapers, Figure 2 shows that amounts of coverage vary in the Guardian and the Telegraph newspapers. Such differences reveal the wider mediation process that underpins reporting and, perhaps, the newspaper's political stance that determines story selection (Carvalho and Burgess, 2005) but does not necessarily inform the reproduction of reported skepticism (see Schmid-Petri, 2017). Differences in numbers of coverage aside, the analysis recognizes the relative patterns of growth and decline in the newspapers' overall reporting. As studies of journalism help to explain (see Anderson, 2014), these stories have met the threshold criteria to be included in the newspapers. As such, they are likely to be event based (hence to exist within the 24 hour news cycle), to be initiated by credible institutions, to potentially involve conflict between recognized stakeholders or to reflect a form of unusualness or oddity. Of these, while significant newsworthy events (climate change conferences or moments of scandal or controversy, for instance) help to explain newspaper attention at some points (see Shehata and Hopmann, 2012), elite institutions' efforts to frame and speak about climate change provide a more satisfactory and routine explanation for the observed peaks and troughs.

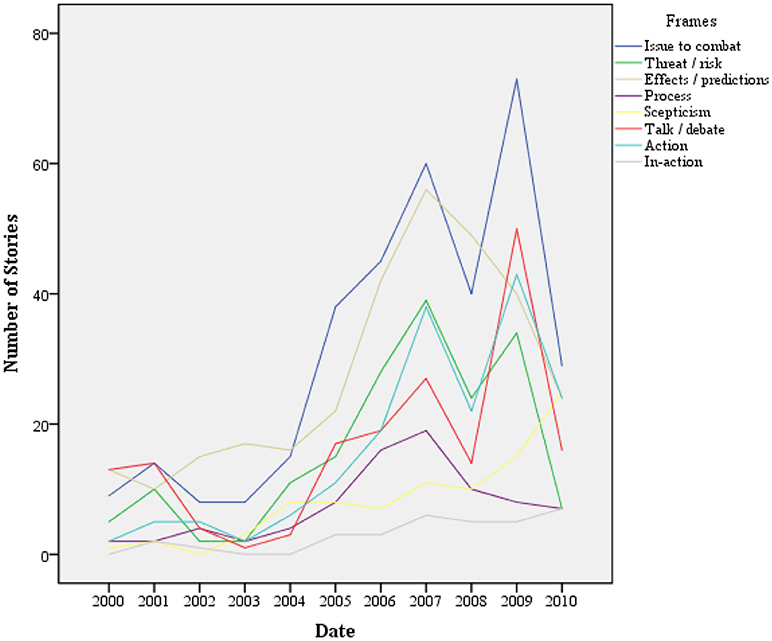

An indication of what is produced from these efforts comes from analyzing the frameworks of meaning reproduced by the newspapers. Eight recognizable “frames” materialize in relatively similar amounts across these newspapers' coverage (see Figure 3). Of interest is how these express important aspects of the claims making over the issue. As is outlined in Figure 1, climate change is introduced here specifically as (i) an actual process and one that has present (ii) “effects” and (iii) potential future “risks” and “threats.” The frames also outline the wider political reactions to climate change. An aspect of coverage reflects the position that it must be (iv) combated and joins other coverage that focuses on a process of (v) discussion [and reaction to (vi) skepticism within that]. Finally, the coverage focuses on practical measures and is divided between reports on (vii) action and (viii) inaction in response to the issue. Having now outlined the politicized context reproduced in this reporting, this paper can examine the industry performances that fit within it.

What Opportunities Do Industry Voices Receive to Enter and Speak in Framed Coverage?

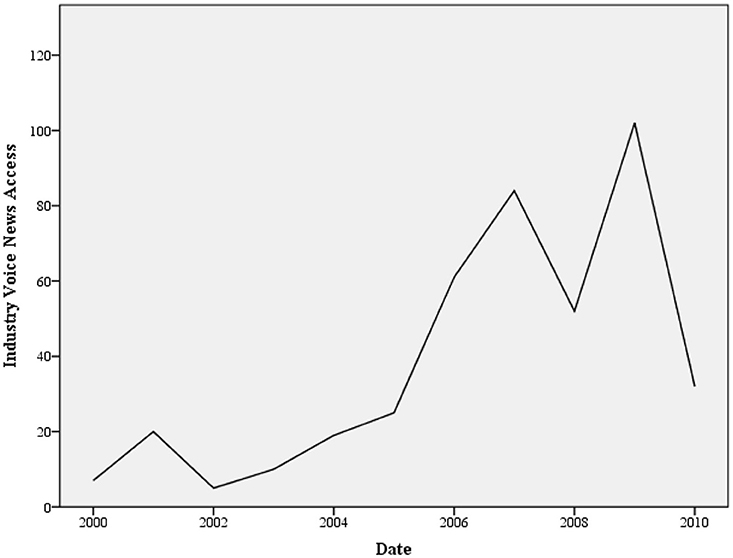

It is often said that industry voices maintain a presence in reporting. In this case, their contributions are observed to be relative in number to the attention given to the issue (see Figures 2, 4). For example, the rise in their number from 2002 to the initial peek in 2006 and the subsequent drop and further peek in 2009 mirrors the overall amount of coverage devoted to the issue over this time (as is represented in Figure 2). This provides a tentative nod to their importance in these news discussions.

Nonetheless, exploring the contributions of industry in context of other voices in the coverage provides a first insight into their presence (see Table 1). Acknowledged is how a greater position for industry in overall number would indicate success from a strong pro-active effort to lead news discussions, for example. As this is not the case, it is fair to assume that industry is likely to be responding/reacting to, and negotiating with, the mediated issue. Recognizing this reality reinforces our sense that industry is playing a more complex role in climate change here (e.g., Levy and Spicer, 2013) than before and one that is being shaped by elite news discussions.

A view that industry's voice is being mediated gains further support from evidence of their position adopted behind the traditionally “less authoritative” voices of interest groups in coverage. This insight together with the sustained presence of orthodox scientists over national politicians signals the types of discussion to be found in this coverage. Less clear is whether industry perspectives and actions are “adapting” in thought and action to this new context (e.g., Levy and Spicer, 2013) or whether these are simply being shaped by journalists. A partial answer lies in the broad picture outlined in Table 2, where industry contributes to frames based around politics (e.g., talk/debate) to science (e.g., effects/predictions) to civil society (e.g., inaction). However, of most interest are their performances in frames of “issue to combat” and “action.” Taken at face value these appear to show industry engaging positively with the issue and perhaps pro-actively in the “leadership” role that Schlichting (2013) describes.

Looking closely at their speaking opportunities in coverage develops this picture. Their voices enter the news in three ways (see Table 3). The first is to have their thoughts referred to in a “direct reference.” This form of entry is illustrated in the following example from the Guardian newspaper: “Shell chairman Sir Philip Watts risks stirring up a controversy in America today when he calls for global warming skeptics to get off the fence and accept that action needs to be taken” (Guardian 12 March 2003). The second opportunity comes through having the speaker's thought paraphrased by journalists in the form of a “attributed statement.” This form can be observed in the following exert from a story example about climate change targets: “A senior executive who spoke to the Sunday Telegraph said there was a large degree of wishful political thinking about the changes targeted by the global summit” (25 October 2009). Finally, voices enter news stories through the form of the “quotation.” In a story that explores the reactions of business to the Stern review, the Independent newspaper includes the following exert that provides an example of this form of entry: “The EEF, which represents manufacturers, said that ‘all sectors of society must now share an equal burden for tackling climate change and, the review must not be used an excuse for the introduction of more punitive taxes on industry”' (Independent 30 October 2006). The amounts of each form of entry reveal that industry voices are being ascribed with discursive authority. More specifically, significant to understanding their performances here is the number of statements and quotations industry representatives provide in coverage and their presence in the most discursively open of these forms, the quotation, most often (354–61%).

What Discursive Roles Do Industry Voices Play in News Stories of Climate Change and to Which Voices Are They Observed to Engage?

In addition to the above insights, we can pinpoint the discursive engagement of industry voices within these mediated discussions of the climate change issue by reviewing evidence of their news role performances. Uncovered in Table 4 is an outline of the performance of their knowledge/statements (251–63%), explanations (102–25%), and evaluations (44–10%) etc. in coverage. When these performances are assessed in context of the framed coverage (see Table 5), we see that industry representatives are outlining their positions most often within stories that contain other voices and that these gain some other opportunities to explain their positions or to evaluate others' positions at these times. Further, we can examine these contributions (i.e., statements, explanations, and evaluations) in context of the specifics of coverage and begin this exploration with the recorded episodes where industry make statements about its “green credentials.”

Performing Green Credentials

This section examines the content of the statements made by industry in the news coverage. As is recognized in the literature, industry actively seek to perform their green credentials in coverage of environmental issues (Lyon and Montgomery, 2015). In this case, these moments occur in stories that are built around topics such as alternative energies and carbon markets, and ones that are clearly positioned as solutions to the problem of climate change (Zehr, 2010). More frequently however, they voice contributions inside stories without these foci and within those reflecting a political focus (e.g., issue to combat, n = 78; action, n = 62; talk/debate, n = 25—see Table 5). Performing in these political discussions, industry outlines its “green credentials” in the form of (i) proposals for change and comments on (ii) progress and (iii) challenges to government positions on climate change.

Predominantly, industry voices enter the story to speak about “combating the issue” from an industry perspective and their contributions reflect Schlichting's (2013) view of industry offering a leadership frame on the issue. Many of their statements reveal or explain their actions, for example. It is on the basis of industry's definitional work that journalists build these types of story as is shown in the following representative example, “Tesco turns its back on landfill” that includes an Executive Director stating: “Climate change is the biggest challenge facing us today and businesses such as Tesco have a responsibility to provide leadership” (the Telegraph 3 July 2009). Forged in these moments are connections between industry actions and the wider political framing of the issue (e.g., the issue to combat and action frames). Elsewhere, as Walker and Wan (2012) have discussed, industry speakers make clear connections between the discourse of environmentalism and mainstream “business thinking” to perpetuate waves of positive engagement with the issue. Following a pledge to slash Wal-Mart's carbon footprint, its CEO (Lee Scott) announces in coverage: “Forgive the jargon, but we think sustainability is cool…And perhaps more than anything else, we see sustainability as mainstream” (the Independent 2 February 2007). Often coverage reflects these newsworthy announcements about CEOs and their environmental concerns. Rarely, however, does this coverage subject industry thoughts and actions to the same journalistic scrutiny or performed criticism that politicians often receive when making similar positive announcements. Uncovered then is how this economized view of climate change is rehearsed, but rarely challenged, in the news which leads to the production of “depoliticized” coverage of the issue (see Carvalho et al., 2017).

Prominent also are industry announcements on their future engagement with the issue. As has been recognized of industry performances before (e.g., Ihlen, 2009), they make statements here on an appropriate course of action for environmentally friendly development in context of the changes in climate temperature (found in the action frame, in particular). Yet mediated according to elite journalistic logic and the presence of other voices, these comments appear in a form that provokes reaction. The presence of the UK entrepreneur, Richard Branson and discussion of his interests in the airline industry provides a useful case in this regard. Reported repeatedly across coverage is Richard Branson's “plea for airlines to take greater responsibility for global warming.” This type of future based statement is made newsworthy by the industry reaction that follows. In this case this is summarized by a journalist as “but his plan to slash fuel emissions by a quarter received a lukewarm response from some corners of the green lobby and the aviation industry” (the Guardian 28 September 2006). When industry representatives move from the “safe ground” of explaining their present practice to suggesting practices to be adopted by others, the conflict story underpinning coverage encourages the sourcing of opinion and reaction to the controversial statement as is referenced above (also see evaluations below).

In other instances, industry voices offer considered and direct comments on ways to “fight climate change” (found in the issue to combat frame). Some of these commentaries shape story content and these, we can observe, fit neatly within previously discussed framework of the “solution story” found elsewhere (Wilkins and Patterson, 1991; Zehr, 2010) and as part of the effects/predications frame recorded here. Presented are concerns with energy use and production. In response to these, likeminded industry representatives voice a form of expertise on the changes required in the organization of the energy market, consumption and consumer behavior. For example, representatives often explain ways to reduce energy consumption in the face of climate change: An energy company (SSE) describes how “about 10% of its consumers are eager to cut down” on energy consumption in its view in addition to introducing itself as central to plans to assist this group to consume less (the Guardian 1 June 2007). In addition to consumer behavior, industry speaks of the need to lower the production of CO2 and presents the thoughts and actions of energy companies as being integral to the process of reduction. Appearing in the Guardian, a representative story explains industry musing on potential solutions, including their preferred fix of “at least 15% of all gas consumed could be made from sewage slurry, old sandwiches and other food thrown away by supermarkets, as well as organic waste created by businesses such as breweries” (the Guardian 5 October 2010).

So far, this analysis has revealed that industry presents itself not simply as a leader but as a knowledge partner, with other stakeholders, on the climate change issue and one that is integral to any solution. Another significant contribution comes in their direct engagement with other elites in news discussions (observed in the talk/debate frame, n = 25). Industry appears to “fall into step” with a general political framing that ascribes an importance to the issue found in the UK coverage. Still, this starting position does not constrain them from voicing their different interests in comparison to the interests of government, for instance, on occasion. The following example is typical of how industry (the airline industry in this case) directs comments on present policy and government positions, attempting to induce concessions from them. Although the BAA chief's comments appear to reassure the reader that the airline strongly agrees with government recommended charges to address their contribution to climate change, these argue also that the rules should be offset by “the abolition of air passenger duty” (the Independent 13 July 2003). A clear sense of an industry perspective on climate policy in particular is illustrated here and this view becomes more evident within their performed explanations.

Clarifying Industry Engagement

The explanations that industry perform received less attention than their pro-active public relations (e.g., Hansen, 2011). Still, these make a significant contribution in this coverage and are observed to fall into distinct sub themes. This section examines the content of these explanations and the other voices to which they engage. Industry explanations reveal efforts to clarify their position on climate change (i) impacts (ii) solutions and (iii) policy in addition to (iv) the actions of politicians and (v) instances where criticism of climate skepticism is leveled at them.

In terms of their place in news content, most explanations contribute to stories that describe the impact of climate change (located in the frames of effects/predications, n = 14 and threat/risk, n = 12). Often these originate from industry reports and explain potential changes to the environment as significant for the operation and the future prosperity of an industry (e.g., fruit, travel, transport etc.). Most of these explanations voice levels of concern over change, despite a few stories that celebrate opportunities for industry that will arrive as colder climates warm (a theme that some call “impact skepticism”—see Schmid-Petri, 2017). An illustrative explanation that is offered in a story called “Feeling the heat” (the Telegraph 26 August 2006) and one that is reproduced across the coverage, states “over 25 years, temperatures will be up two degrees, sea levels will rise and destinations such as Majorca, Crete, and Ibiza will be too hot for many people.” It reveals a process to claim knowledge of future outcomes and to offer insights that traverse countries on behalf of industry. Reproduced reports from powerful consortia introduce links between the global transport systems and climate change, as is the case with the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (“a group of leading international oil and motor industry representatives”). Wider commentaries that lend a sense of authority to these reports' findings appear also as the following comments from CEO of the petroleum company—Shell, demonstrate: “It may seem surprising that we are publishing such a frank analysis, but we are well placed to be a part of the solution to these issues” (the Independent 12 October 2001).

These explanations address industry's configured solutions to climate change, as the above comments reveal. With much of the reporting based around the impact of using fossil fuel resources, industry voices enter these stories to explain solutions to the “present predicament” from their perspective (these are often found in the action framed coverage, n = 19). These are not explanations based on one off technological solutions as was offered by industry and recorded previously in the work of Wilkins and Patterson (1991). Rather these concern existing industry practices and include accounts of carbon offsetting/markets as observed elsewhere (see Zehr, 2010). The voices of the energy industry feature prominently in these accounts. Similar to the following example, outlined here is the importance of policy for industry and the issue. Across the coverage in 2001, nuclear power becomes a preferred solution for example and one that is described to meet the dual needs of industry and climate change. Senior industry figures enter the news to explain that “nuclear power will play a major part in meeting future global energy needs as fossil fuel use is heavily cut under the Kyoto Protocol on climate change” (the Telegraph 16 September 2001).

In addition to commenting on impacts and solutions, other explanations engage with politically focused content (issue to combat, n = 28; action, n = 19). Emerging as stakeholders in these mediated discussions at such times, industry outlines their position in relation to political actors and policy. Referenced often as industry explanations to political or policy announcements, their comments in reporting offer antagonistic explanations of others' conduct. Industry voices single out individuals for comment when appearing in coverage that is framed around instances of “inaction” in the face of climate change, such as is illustrated here. Dominating the story “Shell chief delivers global warming warning to Bush in his own back yard” (the Guardian 17 February 2003), are the words of Shell's chairman Sir Philip Watts that explain that global warming skeptics “should get off the fence and accept that action needs to be taken, before it is too late.” Whereas, the journalist reflects on the future controversy in America that such comments are likely to produce in this case, elsewhere industry surfaces to comment on the controversies that it faces in reporting. Industry voices appear alongside the criticisms of climate change skepticism offered by other elites to explain it and defend their own behavior (found in the inaction and skepticism frames, n = 5 and n = 7, respectively). Revelations about industry connections to a website that questioned orthodox climate science for example are countered by ExxonMobil representatives who appeared in reporting to explain, as the journalists paraphrases here, “it originally paid for the website, has since ceased funding it, and was never responsible for its content” (the Guardian 7 June 2008). Certainly, the latter reflects the concerns over the PR activities of industry (see Monbiot, 2007).

Enacting Criticism

Although industry's evaluations are less significant in comparison to their other enacted roles (statements and explanations), these play a constituent part in the overall media performance that is willed for by industry and shaped by journalists. Revealed in these moments is a clear sense of the positions that industry voices hold as stakeholders and how these positions contrast with others', many of whom appear as the object of their evaluations in coverage. This section examines the detail of their performed evaluations and how these address the following: (i) targets, (ii) policy, (iii) political claims, and finally (iv) claims made by industry.

The study of these evaluations shows that there are points of contest alongside common ground that complete a more complex mediated relationship between the positions held by industry and those by government. The discussion of political targets provides a particular fissure in this regard as is found in the issue to combat frame (n = 18) and action frame (n = 10). Often appearing in coverage of climate talks, industry evaluations respond to the verbalized—positive—responses to tackle climate change performed by political elites. Sometimes these comments emerge within wider stories on political action. At other times, industry comments help to form the story as is represented in the case of their response to government's climate change targets, as “targets are delusional.” Reporting on a “private” and collective response to government from the energy companies, the Telegraph in this instance allows a “senior executive” from one of the companies in the story to suggest “there was a large degree of wishful political thinking about the changes targeted by the global summit” (the Telegraph 23 October 2009).

Besides these cases, the “talk/debate” frame (n = 5) includes industry evaluations positioned through the process of the reported talks, including commentary on their outcomes. Either journalists use industry commentary to provide additional comment in a story, like the use of green pressure groups in this case, or form new reporting based on it. A story focused on industry's involvement in green energy solutions to climate change, includes the following evaluation: “any post-Kyoto objectives set in Copenhagen will alter the sector's near-term prospects” (the Times 3 October 2009). Other evaluations offer a far more abrasive tone and, when analyzed, these depict industry as an uneasy bedfellow of political elites. For example, in adopting a more critical position, industry speakers address climate agreement from their perspective in 2009 as a “political fudge” and far removed from a desired—“‘clear and simple' climate deal to help the financial markets plan for the future” (the Times 19 December 2009).

It is perhaps no surprise that coverage formed according to the logic of the conflict story will reproduce canvassed and conflicting opinions. In operating in this reporting, this function explains the place and the timings of the observed evaluations. Nonetheless, such commentaries appear elsewhere and in more subtle forms, including the sophisticated activity of “megaphone diplomacy.” Elites, as Davis (2003) explains, use the media to stake their claims and engage with others on these issues. Industry evaluations of government thinking are presented in this way for instance and appear to stress unpleasant outcomes from the present direction in government policy. In an example that discusses investment in wind technology, imaginatively entitled “Blown away” (the Times 15 February 2009), two UK companies—British Telecomm and Tesco—speak jointly and suggest that they “may abandon huge new eco-projects following a last-minute rule change by the government.” In addition to the subtle nudging of political decision-making, other more forceful evaluative comments on policy appear from time to time. Although unusual, these commentaries place the established position of government far from that of industry and as—“‘doom-mongering” over global warming and ignoring the realities of modern economics” as the CEO of British Airways stresses here (the Telegraph 5 December 2006).

Further, occasional attacks on political and industry actors replace traditional discussion on the objectives of targets and policy. Although significantly fewer in number, these critical commentaries focus mostly on the leadership of political elites, including the activities of the then UK Prime Minister and the then President of the USA. The focus of criticism varies, and examples show some comments holding these politicians to account over their over-exuberance in terms of “repeatedly claiming that Britain must be a world leader on global warming” in the case of the British PM (the Telegraph 14 October 2007) and others claiming noticeable uninterested on the part of other leaders. In the story “Boot boss kicks out at Obama,” Nathan Swartz, the chief of the company Timberland, is given space to suggest the US President would not show support for the climate summit with the words: “He flew to Copenhagen to pitch for the Olympics but apparently the climate is not as important” (the Times 22 November 2009). In an equally low number in coverage, industry leaders appear to reflect on the intentions and the schemes of other representatives from industry. In the following example, an individual's activities are suggested by another CEO to be simply self-interested public relations: “Richard Branson's promotion of biofuels is a PR stunt and green taxes on aviation are pure opportunism” (the Guardian 15 March 2008).

Discussion and Conclusion

This study has examined the relationship between framed media content and the performances of industry. The reproduced news frames reflect the wider claims making over climate change in the UK. Studying the coverage shows that it fluctuates and some of which can be explained by prominent events, but most by the activities of stakeholders (research question 1). The UK context, and a Labour government proactive on the climate policy specifically, appears to inform the framed coverage around “political reaction,” “actions” and outcomes. Situating industry voices within these frames (research question 2), reveals their interactions with others. In featuring in lesser numbers than other stakeholders (e.g., politicians, scientists, and interest groups), they respond/react to, and negotiate with, the mediated issue in addition to proactively shaping it. Measuring their entry to these stories confirms that this coverage provides opportunities to have their views reproduced there (i.e., in the quotation or recorded statement) than be simply referenced by journalists. This discursive authority is reflected in the roles that industry voices play and the other voices in which they engage (research question 3). Here industry is revealed to be claiming “green credentials” or directing others to their actions in the face of climate change. But more so, industry is attempting to play the role of “a leader” and “knowledge partner” in these discussions especially those framed around the effects of, or predictions of changes in, the climate. Attempts to proactively lead on the issue whether through announcements or reports are part of a more complex role. The results show that industry provides explanations within coverage framed around climate change as an “issue to combat” or one to be discussed (i.e., “talk/debate”) and they engage courteously but critically with government policy likely to affect their interests elsewhere.

Hence these results confirm the general claim that the participation of stakeholders in news reporting is diverse, rather than fixed and static and this is underpinned by the developing issue (see Schlesinger, 1990; Ihlen, 2009). As is evidenced here, industry performances are varied, rather than assured in their position, and appear to do more than simply express opposition to climate change. Absent from their recorded commentaries is the role of the staunch critic of climate change for instance. Geared to the larger and evolving politicization of the issue, their performances respond to the discursive nature of this reporting.

Of course, the voices of industry do play a part in shaping the discussion of climate change. Recently, it is argued, these reduce its focus to the economy with their narratives of economization (Carvalho et al., 2017). The study provides support for this view, but it also notes that their power to shape media discussion is somewhat limited. In contrast to those stories in which their commentaries feature to define a response, most stories require them to engage with the wider framing of climate change in some way. Specifically, they perform within frames that emphasize the presence of climate change, its effects and the need for action and, in the process, influence the voices and discussions that appear in UK reporting. The reduced space for conflict and overt skepticism in the coverage reflects the balance of frames focusing around politics, science and civil society and the absence of outright criticism in industry performances. Industry performs alongside other elites and in response to their commentaries and, as part of the process adopts, or at least mimics, the “imaginaries of climate change” (Levy and Spicer, 2013) held by other elite stakeholders. Still, as is reflected elsewhere, these performances are limited to discussing the mitigating of climate change rather than to discussing the need to reform structures, processes or behaviors in the coverage on the whole (Schmid-Petri, 2017). Analyzed in this context, these performances appear as sophisticated efforts to stage-manage an impression of elite thoughtfulness and action in the face of the serious issue on the part of many sectors. Recognizing these reactions as a response to the changing political circumstances is a chief contribution of this paper.

A related and additional contribution of this analysis are the insights it provides into the ordering and the positioning proprieties of news stories. As has been discussed, it is the application of elite journalism logic that shapes the ordered news performances observed here. In underpinning the presentation of the observed speaking opportunities, elite newspapers have assisted in the reproduction of industry speakers on the climate change issue based on the newsworthiness they ascribe to economic aspects in their stories. Industry appears to discuss solutions based on the normal business logics of the market, which differ from the technological panaceas observed previously (Zehr, 2010). Contributing to the narrowing of the discussion of the issue to economization, elite newspapers also encourage the reproduction of discussion and voices on other topics and, in so doing, they position speakers to reflect their assumed “stakeholder positions.” Following these story types, their reporting traces stakeholder interests and produce accounts that comment on the traditional interests of industry—crudely defined—as contrasting, or clashing with political targets and/or goals, for instance. The tone and the strategy that industry uses to criticize targets, policies, and political figures appear at these moments as reminiscent of their position taking/performances observed previously. Nevertheless, these instances (and the evaluations they include) appear infrequently when assessed in context of their performances as a whole. This insight suggests there has been break from, and not a simple continuing of, industry's, previously observed, performances.

As a result, we are reminded that industry adopts a complex participatory role in this reporting and one that involves “performing” moments of leadership, agreement and moments of tension in relation to other elites and the evolving issue. This observation allows us to think about how reporting will likely develop. At present, the combination of issues (austerity and Brexit following 2010) and a change in political leadership (i.e., governments) has displaced climate change as a priority for UK political discussion and the elite coverage that is attuned to it. In the future however, where discussions will move from the mitigating of the issue, to taking forms of action on it on account of the witnessing of the effects of climate change, industry performances may involve more displays of tension rather than agreement and leadership. If this is the case, then elite news stories may provide space to scrutinize the spoken actions and the outcomes of the approach to climate change that industry representatives and other elite actors have performed thus far.

However, these suggested outcomes perhaps overlook the constraints that face elite journalism and have shaped climate change reporting to date. Irrespective of the importance of the climate change issue, the gatekeeping function of journalistic logics remain. For example, stories on the issue will continue to be selected according to the criteria of being event-led, containing received conflict or reflecting oddity. With elite journalism being attuned to, and largely reproducing the political discussion on climate change, its reporting will continue to narrow the parameters of discussion of the issue to the forms of economization that have been observed. Hence, there will be greater emphasis placed on journalism to recognize its responsibility to counteract these outcomes and therein maintain the spotlight on this important issue. At the same time, journalists will be required to enact their “watchdog” roles in terms of assessing that elites, from both politics and business, are meeting their obligation and fulfilling their promises in terms of tackling the issue. While there is also the possibility of a growing adversarial press performance on the issue in what Hallin (1985) recognizes as journalists move into a sphere of deviance (where they are forthright in outlining “deviant perspectives” on an issue), this may well reflect politically entrenched positions already established in newspaper editorial writing and in turn assist in delaying, rather than encouraging, the calls for action.

As a consequence, it is important to explore how reporting of elite journalism develops in the future and to widen this partial view of the news ecology to incorporate the activities of other media outlets and mediums. Research on television and online journalism and outlets situated at different market positions (and thus those enacting different journalistic logics) is needed. A widened research agenda, sensitive to claims making and news making processes, will help to monitor a differentiated reporting of these outcomes and the openings for performances. Whatever emerges in the future nonetheless, the robust and rigorous theoretical and methodological template offered here is well equipped to further explore the ongoing performances of industry set against these interesting developments.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Altheide, D., and Snow, R. P. (1991). Media Worlds in the Postjournalism Era. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Antilla, L. (2005). Climate of scepticism: US newspaper coverage of the science of climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 15, 338–352. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.08.003

Baker, P., and McEnery, A. (2005). A corpos-based approach to discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in UN and newspaper texts. Lang. Polit. 4, 197–226. doi: 10.1075/jlp.4.2.04bak

Berglez, P. (2011). Inside, outside, and beyond media logic: journalistic creativity in climate reporting. Media Culture Soc. 33, 449–465. doi: 10.1177/0163443710394903

Boykoff, M., and Boykoff, J. (2007). Climate change and journalistic norms: a case study of US mass media coverage. Geoforum 38, 1190–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.008

Boykoff, M. T., and Rajan, S. R. (2007). Signals and noise: mass-media coverage of climate change in the USA and UK. EMBO Rep. 8, 207–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400924

Carpenter, C. (2001). Businesses, green groups and the media: the role of non-government organizations in the climate change debate. Int. Affairs 77, 313–328. doi: 10.1111/1468-2346.00194

Carter, N. (2018). Blowing Hot and Cold: A Critical Analysis of Labour's Climate Policy. London: Leverhulme Trust.

Carvalho, A., and Burgess, J. (2005). Cultural circuits of climate change in the UK broadsheet newspapers. Risk Anal. 25, 1457–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00692.x

Carvalho, A., van Wessel, M., and Maeseele, P. (2017). Communication practices and political engagement with climate change: a research agenda. Environ. Commun. 11, 122–135. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2016.1241815

Christensen, M., and Wormbs, N. (2017). Global climate talks from failure to cooperation and hope: swedish news framings of COP15 and COP21. Environ. Commun. 11, 682–699. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2017.1333964

Cottle, S. (2000). “TV news, lay voices and the visualization of environmental risk,” in Environmental Risks and the Media, eds S. Allan, C. Carter, and B. Adam (London: Routledge), 29–44.

Cottle, S. (2009). “Ecology and climate change: From science and sceptics to spectacle,” in Global Crisis Reporting: Journalism in the Global Age, ed S. Cottle (Maidenhead: OU Press), 71–84.

Cox, R., and Schwarze, S. (2015). “The Media/Communication Strategies of Environmental Pressure Groups and NGOs,” in The Routledge Handbook of Environment and Communication, eds A. Hansen and R. Cox (London: Routledge), 73–85.

Curtin, P. A., and Rhodenbaugh, E. (2001). Building the news media agenda on the environment: a comparison of public relations and journalistic sources. Public Relations Rev. 27, 179–195. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(01)00079-0

Davis, A. (2003). Wither the mass media and power? Evidence for a critical elite theory alternative. Media Culture Soc. 25, 669–690. doi: 10.1177/01634437030255006

Gaither, B. M., and Gaither, T. L. (2016). Marketplace advocacy by the U.S. fossil fuel industries: issues of representation and environmental discourse. Mass Commun. Soc. 19, 585–603. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2016.1203953

Hall, S., Critcher C., Jefferson, T, Clarke, J. and Roberts, B. (1978). Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. London: MacMillan.

Hansen, A. (2011). Communication, media and environment: towards reconnecting research on the production, content and social implications of environmental communication. Int. Commun. Gazette 73, 7–25. doi: 10.1177/1748048510386739

Ihlen, Ø. (2009). Business and climate change: the climate response of the world's 30 largest corporations. Environ. Commun. 3, 244–262. doi: 10.1080/17524030902916632

Levy, D., and Newell, P. (2000). Oceans apart? Business responses to the environment in Europe and North America. Environment 42, 8–20. doi: 10.1080/00139150009605761

Levy, D. L., and Spicer, A. (2013). Contested imaginaries and the cultural political economy of climate change. Organization 20, 659–678. doi: 10.1177/1350508413489816

Lewis, J., Williams, A., and Franklin, R. (2008). A compromised Fourth Estate? UK news journalism, public relations and news sources. J. Stud. 9, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/14616700701767974

Lockwood, A. (2010). “Preparations for a post-Kyoto media coverage of UK climate policy,” in Climate Change and the Media, eds T. Boyce and J. Lewis (Oxford: Peter Lang), 186–199.

Lyon, T. P., and Montgomery, A. W. (2015). The means and ends of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 28, 223–249. doi: 10.1177/1086026615575332

Matthews, J. (2016). Maintaining a politicized climate of opinion? Examining how political framing and journalistic logic combine to shape speaking opportunities in UK elite newspaper reporting of climate change. Public Understand. Sci. 26, 467–480. doi: 10.1177/0963662515599909

Matthews, J., and Brown, A. (2012). Negatively shaping the asylum agenda? The representational strategy and impact of a tabloid news campaign. J. Criticism Theor. Pract. 13, 802–817. doi: 10.1177/1464884911431386

McManus, P. A. (2000). Beyond Kyoto? Media representation of an environmental Issue. Austral. Geogr. Stud. 38, 306–319. doi: 10.1111/1467-8470.00118

Nelkin, D. (1995). Selling Science: How the Press covers Science and Technology, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

Olsson, E. K. (2009). Responsibility framing in a ‘climate change induced' compounded crisis: facing tragic choices in the Murray—Darling Basin. Environ. Hazards 8, 226–240. doi: 10.3763/ehaz.2009.0019

Painter, J., and Gavin, N. T. (2016). Climate skepticism in British newspapers, 2007–2011. Environ. Commun. 10, 432–452. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.995193

Schlesinger, P. (1990). “Rethinking the sociology of journalism: source strategies and the limits of media-centrism,” in Public Communication: The New Imperatives, ed M. Ferguson (London: Sage), 61–83.

Schlichting, I. (2013). Strategic framing of climate change by industry actors: a meta-analysis. Environ. Commun. 7, 493–511. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2013.812974

Schmid-Petri, H. (2017). Do conservative media provide a forum for sceptical voices? The link between ideology and the coverage of climate change in British, German and Swiss newspapers. Environ. Commun. 11, 554–567. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2017.1280518

Shehata, A., and Hopmann, D. (2012). Framing climate change. J. Stud. 13, 175–192. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0174-1

Skjærseth, J. B., and Skodvin, T. (2003). Climate Change and the Oil Industry. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Tøsse, S. (2013). Aiming for social or political robustness? Media strategies among climate scientists. Sci. Commun. 35, 32–55. doi: 10.1177/1075547012438465

Trumbo, C. (1996). Constructing climate change: claims and frames in US news coverage of an environmental issue. Public Understand. Sci. 5:269–283. doi: 10.1088/0963-6625/5/3/006

Wakefield, S. E. L., and Elliott, S. L. (2003). Constructing the news: the role of local newspapers in environmental risk communication. Profess. Geogr. 55, 216–226.

Walker, K., and Wan, F. (2012). The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. Emerald Manage. Rev. 109, 227–239. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1122-4

Wickman, C. (2014). Rhetorical framing in corporate press releases: the case of British petroleum and the gulf oil spill. Environ. Commun. J. Nat. Culture 8, 3–20. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2013.816329

Keywords: climate change, industry, journalistic logics, politicization, mediation, elite media

Citation: Matthews J (2018) Placing Industry in the Frame: Exploring the Mediated Performance of Industry Voices in Climate Change Reporting. Front. Commun. 3:48. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00048

Received: 05 March 2018; Accepted: 04 October 2018;

Published: 05 November 2018.

Edited by:

Tracylee Clarke, California State University, Channel Islands, United StatesReviewed by:

Laura Rickard, University of Maine, United StatesAntonio Perianes-Rodriguez, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2018 Matthews. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julian Matthews, jpm29@leicester.ac.uk

Julian Matthews

Julian Matthews