94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 24 May 2018

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 3 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00021

Ralph Van den Bosch

Ralph Van den Bosch Toon Taris*

Toon Taris*Drawing on Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci et al., 2017), this study examines the associations between authenticity at work, motivation and well-being, assuming that motivation would at least partly mediate the association between authenticty and well-being. Since authentic behavior refers to the degree to which a person acts in agreement with their true self (i.e., one's own core values), high levels of authenticity at work should relate positively to more intrinsic types of motivation regulation and negatively to more extrinsic types of motivation regulation. Moreover, high levels of authenticity should be associated with higher well-being at work (i.e., higher work engagement and lower burnout). Structural equation modeling using cross-sectional data from 546 participants revealed that self-determined motivation (i.e., autonomous motivation) showed positive associations with authenticity at work and that non-self-determined motivation (i.e., controlled motivation and amotivation) showed negative associations with authenticity at work. The positive associations increased in strength with increasing self-determined motivation. A similar—but reversed—pattern was found for the negative associations. Parallel mediation analysis revealed that self-determined motivation partially mediated the relationship between authenticity and well-being at work.

The associations among authenticity, self-determined motivation and well-being at work have gained considerable interest over the past few years. One line of research has successfully related authenticity—i.e., the degree to which someone acts in agreement with their true self (van den Bosch and Taris, 2014a)—to various aspects of well-being. For example, Toor and Ofori (2009) found a positive association between experienced authenticity and leaders' well-being. Kernis and Goldman (2006) reported positive associations between self-reported authenticity on the one hand and eudaimonic well-being, hedonic well-being, and life satisfaction on the other. Finally, Emmerich and Rigotti (2017) examined the associations among authenticity on the one hand and depression, work ability and intrinsic motivation on the other.

In a different line of research, a series of studies focused on the associations between well-being on the one hand and various types of motivation on the other. In this research a major distinction is made between self-determined vs. non-self-determined motivation and behavior (Deci et al., 2017), arguing that—since they stem from the self—especially self-determined behaviors are “authentic” and should therefore be associated with positive well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000). For example, van Beek et al. (2012) showed that self-determined forms of motivation were associated with favorable scores on burnout and work engagement. Similarly, Van den Broeck et al. (2011) found that autonomous motivation was associated with favorable scores on emotional exhaustion and work engagement.

Interestingly, both lines of research employ different conceptualizations of authenticity. Whereas research focusing on the associations between different types of motivation and well-being tends to construe authenticity as an inherent property of behaviors driven by self-determined motivation and that does not need separate assessment (e.g., Ryan and Deci, 2000), studies examining the direct associations between authenticity and well-being focus on authenticity as an affective-cognitive phenomenon that can (and must) be assessed separately from particular behaviors and/or motivations (e.g., van den Bosch and Taris, 2014a; Emmerich and Rigotti, 2017). This raises the question as to the interrelations of these two lines of research: although both speak of “authenticity” and construe this concept at the meta-level as relating to behaviors that reflect one's true self, in terms of their specific conceptualization and measurement both approaches differ strongly. The present study addresses this issue, examining the relationships among these two conceptualizations of authenticity in the context of well-being at work.

Studies focusing on authenticity as a construct that is measured as a distinct concept, independently from particular underlying motivations, tend to differ in the way they construe and measure authenticity. Trait-based conceptualizations of authenticity (such as that of Wood et al., 2008) construe authenticity as a personal characteristic that is relatively stable across time or situations. Conversely, state-based conceptualizations of authenticity assume that the feeling of being authentic is contingent upon the degree to which a person and the environment in which they operate are in agreement (Barrett-Lennard, 1998; van den Bosch and Taris, 2014a). Since the features of this environment are subject to change, the degree of agreement between this environment and the person (i.e., their experienced authenticity) will also be subject to change. Therefore, this approach considers authenticity as a state, not a trait. In the work context, this reasoning suggests that if a work environment fits better with a worker's “core” (i.e., authentic) self, this worker will feel more authentic. Based on this principle, van den Bosch and Taris (2014a) developed an instrument tapping state authenticity in the work environment, with its items referring to transitory feelings of authenticity. This study adopted this measure to investigate the associations between state authenticity at work, self-determined motivation, and well-being.

Based on the work of Wood et al. (2008) and van den Bosch and Taris (2014a) conceptualized authenticity in terms of three central dimensions: authentic living, self-alienation, and accepting external influence, respectively. Authentic living refers to the degree to which employees' actions at work agree with their personal values, feelings and beliefs. For example, a flight attendant smiling at passengers may well just be doing “emotion work,” rather than to act authentic in agreement with their feelings (Chang and Chiu, 2009). Self-alienation is the experience of “knowing who one is” at work. For example, employees may feel “out of touch” with their core self at work, may wonder who they are at work and might feel “cut off” from who they really are. High levels of self-alienation are associated with psychopathology. The final dimension of authenticity concerns the degree to which workers accept external influence of others as well as the belief that they are actually meeting the expectations of others, rather than doing what they themselves consider important and worthwhile. According to Schmid (2005), especially self-alienation and authentic living are continuously influenced by the social environment. Accepting external influences (i.e., being subjected to situational forces; e.g., an employee who must take orders from his or her superiors, et cetera, will probably report high scores on this dimension) is therefore likely to lead to subjective feelings of self-alienation and of living inauthentically. Overall, low levels of self-alienation and accepting external influence and a high levels of authentic living signify high levels of authenticity.

As indicated above, within Self-Determination Theory (SDT) authenticity is considered as an inherent property of behaviors driven by self-determined motivation. If the motivation for that particular property is self-determined, that action is “authentic” and no separate assessment of a worker's feelings of authenticity is required. SDT focuses on the motivation behind the choices that people make, assuming that these choices are either self-motivated and self-determined or instigated by external influences (Deci et al., 2017). Organismic Integration Theory (OIT; Deci and Ryan, 1985) differentiates among six forms of self-determined behavior, describing these behaviors in terms of the extent to which they are self-determined or due to other, non-self-determined (or external) reasons. For example, employees might participate in activities because of social pressure, rewards, or the fear of punishment. OIT distinguishes among six types of regulatory styles that vary from being non-self-determined (i.e., amotivation), via external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, and integrated regulation, to being completely self-determined (intrinsic regulation, Ryan and Deci, 2000). Amotivation is a general lack of the intention to engage into action. Amotivated workers do not act, or if they do, they act very passively. External regulation is considered the least self-determined form of external motivation. It contains elements of rewards and punishments. Introjected regulation is to some degree—but only superficially—internalized, and is therefore not integrated with the self. Work activities led by introjected regulation are to some degree internally driven but still have a primarily external locus. Therefore, they are not considered to be part of the self.

Both external and introjected regulation are forms of controlled motivation, constituting qualitatively inferior types of motivation (Gagné and Deci, 2005). Conversely, identified regulation, integrated regulation, and intrinsic regulation are relatively autonomous and therefore qualitatively superior forms of motivation (Deci et al., 2017). Identified regulation reflects a conscious evaluation of a goal in such a manner that the behavior toward achieving this goal is adopted as personally important. Behavior that derives from identification, for example with a work task, is relatively autonomous and self-determined. When identified regulations are completely incorporated in the self and are therefore congruent with one's other values and beliefs, integration has taken place, leading to integrated regulation (Deci and Ryan, 2000). The main difference between integrated regulation and intrinsic motivation concerns the degree to which behavior is experienced as enjoyable. Whereas integrated regulation occurs when one considers the outcome of a particular behavior important, this does not necessarily mean that one enjoys engaging in this behavior. Conversely, intrinsically motivated employees primarily engage in work activities because they find these enjoyable, challenging, interesting, or pleasing (Deci et al., 2017).

These six regulation types can be ordered on the basis of the level to which employees have internalized the reasons to engage in certain activities. Whereas amotivation for a particular behavior is a fully non-self-determined type of regulation, its opposite (intrinsically regulated behavior) is completely self-determined (Ryan and Deci, 2000). SDT states that intrinsically motivated behaviors are the “prototype” of self-determined actions (Deci and Ryan, 1985). These prototypical actions emerge directly from the core self. These prototype actions are unalienated and “authentic” in their fullest sense. However, externally motivated behavior can also be self-determined. Therefore, individuals must identify with their work in order to let their behavior be self-determined (Deci et al., 2017). OIT proposes that the level of self-determined motivation increases with more autonomous forms of motivation, and that motivation is the most self-determined at the intrinsic level (Deci and Ryan, 1985). This implies that if employees feel more authentic at work, the ratio between self-determined and non-self-determined behavior will shift toward the first and derives therefore more from the self (Deci and Ryan, 2000).

If this reasoning is correct, the association between authenticity at work and motivation should be positive for autonomous/self-determined motivation, gradually decreasing in strength and ultimately becoming negative as the behavior becomes less autonomous/less self-determined. Basically, workers who experience high levels of authenticity will more often engage in work activities because they really enjoy these activities, that is, they are intrinsically motivated for these activities. As Emmerich and Rigotti (2017) state, “As authentic behavior has its source in the true self of an individual, authentic behavior is self-determined by nature and … leads to improved intrinsic motivation.” Conversely, workers who experience low levels of authenticity are likely to engage in work activities because they earn money with these activities rather than for the joy or pleasure they derive from their work, i.e., they are more extrinsically motivated for these activities. These activities are not self-determined and do therefore not have their source in the true self of a worker, i.e., engagement in such activities is likely to be associated with low, rather than high levels of authenticity (cf. Emmerich and Rigotti, 2017).

Based on this reasoning, we expect a positive association between authenticity at work on the one hand and both intrinsic regulation (Hypothesis 1a) and identified regulation (Hypothesis 1b) as forms of autonomous motivation on the other. These regulation types are both forms of autonomous motivation, are largely self-determined, and originate from the core authentic self (Emmerich and Rigotti, 2017). Conversely, we expect negative associations between on the one hand authenticity at work, and controlled motivation and amotivation (Hypothesis 1e) on the other. These types of motivation are not or only to a minor degree self-determined and do not originate from employees' core (or authentic) self. Consequently, these types of motivation will be reported by employees who experience lower levels of authenticity at work. Thus, high levels of authenticity are expected to be negatively associated with introjected regulation (Hypothesis 1c), external regulation (Hypothesis 1d), and amotivation (Hypothesis 1e), respectively.

Work engagement is “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2010, p. 13). Vigor involves experiencing high levels of energy and mental resilience while working, as well as the willingness to invest effort in one's work. Dedication is characterized by feelings of enthusiasm, challenge, and pride. Lastly, absorption refers to being concentrated and engrossed in one's work. Engaged workers are “pulled” to their work and show high levels of self-esteem (Taris et al., 2010). The pulling in particular, may be the result of high identification with their job, which implies that one also feels authentic at work. Therefore, we expect authenticity and work engagement to be positively associated (Hypothesis 2).

Burnout is characterized by three subdimensions, emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and (lack of) personal accomplishment, respectively (Schaufeli et al., 1996). Emotional exhaustion refers to high levels of fatigue and lack of mental resources. Cynicism involves holding a distant and indifferent attitude to one's work, while (lack of) personal accomplishment refers to a low level of professional efficacy and the tendency to assess one's own functioning at work in negative terms. In practice, the exhaustion and cynicism dimensions are considered the core of the burnout concept (Taris et al., 2017). Regarding the associations between burnout and authenticity, we expect people who feel more authentic at work to feel less detached from their own values and beliefs, and they will therefore report lower levels of cynicism. Moreover, since employees who feel authentic will have a better fit with their jobs, they should experience relatively low levels of emotional exhaustion. The process of not staying in touch with one self and struggling with the daily causes a misfit between the person and job, which will deplete one's energy and will reduce their level of pride and identification with their job. Therefore, authenticity at work and burnout should be associated negatively (Hypothesis 3).

It would seem intuitively plausible that engaging in personally meaningful and pleasurable activities at work that are congruent with one's own goals, interests and values (that is, in self-determined and autonomous activities, Deci et al., 2017) will lead workers to experience high levels of dedication to their work, to be absorbed by their jobs, and even to feel energized. That is, workers who have the opportunity to participate in such activities at work are likely to experience high levels of work engagement (cf. Schaufeli and Bakker, 2010; van Beek et al., 2012). However, engaging in work activities that are clearly not self-determined or that are instigated by others are not likely to result in such positive outcomes. This reasoning was confirmed by van Beek et al. (2012) who found that more autonomous forms of motivation were positively and more controlled forms of motivation were negatively related to work engagement. Therefore, we expect that the two autonomous forms of motivation (i.e., intrinsic and identified regulation) will be positively related to engagement (Hypotheses 4a,b, respectively). Conversely, the controlled and non-self-determined forms of motivation (introjected motivation, external regulation, and amotivation) will relate negatively to engagement (Hypotheses 4c–e, respectively).

In a similar vein, van Beek et al. (2012) found that burnout was positively related to introjected regulation and negatively to intrinsic and identified regulation, respectively. Since burnout involves a process of mental distancing from work, workers reporting high scores on burnout are unlikely to identify with their jobs. However, they must still perform their work duties. Thus, their motivation to engage in these duties will predominantly originate from external factors rather than from their core self (Deci et al., 2017). We expect that persistence of this situation—in which workers must engage in non-self-determined and controlled regulation—will eventually result in depletion of workers' mental resources and in a loss of energy. Therefore, we expect that workers who report high levels of autonomous motivation for their jobs (i.e., intrinsic and identified motivation) will report relatively low levels of burnout (Hypotheses 5a,b), and that controlled motivation (introjected and external regulation) and amotivation will relate positively to burnout (Hypotheses 5c–e, respectively).

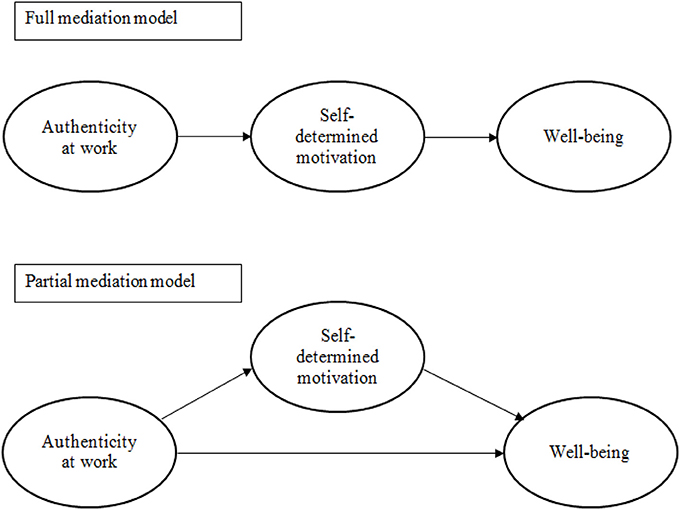

Figure 1 presents a heuristic model for the expected relations between authenticity at work, motivation, and well-being. Essentially, this model proposes that authenticity and well-being are both directly (cf. Hypotheses 2, 3) and indirectly related (Hypotheses 1a–e, 4a–e, 5a–e). This implies that we assume that the associations between authenticity on the one hand and well-being (work engagement and burnout) on the other are at least partly mediated by motivation (Hypothesis 6).

Figure 1. Heuristic model of the full and partial mediation model between authenticity at work, self-determined motivation, and well-being.

The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association and our local ethical review board. Specifically, although studies using standardized self-report surveys, in which participants are not deceived and in which no intervention is implemented or evaluated, are formally exempted from the approval of an institutional ethics committee, participants were a priori informed about the aims and design of the study. Moreover, they were informed that participation was completely voluntary and anonymous. Participants did not receive any monetary compensation for their contribution and could withdraw from the study whenever they wanted. The invitation to participate in the study led the participants to an online survey. Informed consent to use their data was given by clicking the “finish”-button on the last page of the survey.

Twenty-two Dutch organizations providing financial services to their customers participated in the present study. All employees of these organizations (N = 912; the average number of employees per organization was 41) received an e-mail at their work e-mail address with a request to complete an online survey. One week after the first e-mail a reminder was sent. Both messages first explained the purpose and relevance of the study, then offered a link to the first page of the survey. The introductory screen emphasized that participation was voluntary and completely anonymous. Participants were informed that the questionnaire could be taken during work time, and that completing the questionnaire would take about 10 min. In total 564 participants fully completed the online survey, yielding a 62% response rate. In two organizations (with response rates of 22 and 23%) the lower threshold for acceptable response of 26.2% proposed by Baruch and Holtom (2008) was not met, and these organizations were excluded from further analysis. This did not result in a substantial drop in the number of participants, since only 18 participants were omitted.

The response rate for the remaining 20 organizations varied from 33 to 100%, yielding an average response rate of 71.3% and an overall sample size of 546 participants (53.7% female; Mage was 37 years, SD = 9.9). A third (35%) had completed an intermediate level of vocational education, 50% held a bachelor's degree, and 15% held a master's degree. The 20 organizations included in the present study provided a broad spectrum of services to their customers. Examples of the services provided are financial audits, accounting and financial advice in general. Approximately 80% of the employees in these organizations provided such services. The remaining 20% worked in support and management jobs such as personal assistant, human resources officer or IT specialist.

Authenticity was measured with the Individual Authenticity Measure at Work (IAM Work; van den Bosch and Taris, 2014a). This measure taps the three authenticity dimensions (self-alienation, authentic living, and accepting external influence, respectively) with four items each. Participants were asked to focus on their work experiences of the past 4 weeks. They were then asked to indicate the degree to which each statement applied to them. Typical items are: “I behave in accordance with my values and beliefs in the workplace” (authentic living, alpha = 0.75); “At work, I feel out of touch with the ‘real me”' (self-alienation, alpha = 0.85); and “At work, I behave in the manner that people expect me to behave” (accepting external influence, alpha = 0.65) (1 = “does not describe me at all, 7 = “describes me very well”).

Work engagement was measured with the nine-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli and Bakker, 2010). Vigor was measured with three items, including “At my work, I feel bursting with energy” (alpha = 0.87). Three other items tapped dedication, such as “My job inspires me” (alpha = 0.88). The remaining three items tapped absorption, including “I feel happy when I am working intensely” (alpha = 0.77). All items were answered on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = “never”, 6 = “always”).

Burnout was measured with two scales (emotional exhaustion and cynicism) of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS; Schaufeli et al., 1996). Typical items are “I feel tired when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job” (emotional exhaustion, 5 items, alpha = 0.88) and “I have become less enthusiastic about my work” (cynicism, 4 items, alpha = 0.84) (0 = “never,” 6 = “every day”).

Motivation was assessed with the Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale (Gagné et al., 2015). This scale contains 19 items that cover six dimensions of motivation: amotivation, external materialistic regulation, external social regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, and intrinsic regulation. Note that external regulation is divided in two forms, external social and external material regulation. According to Gagné et al. (2015), both are important in the work context and are therefore included separately. Furthermore, integrated regulation is not included in Gagné et al.'s measure. Therefore, integrated regulation was not included in the current study. Amotivation was measured with four items, including “I don't know why I work: this work is meaningless to me” (alpha = 0.93). Three items measured external material regulation, including “I work because others (e.g. employer, supervisor) will reward me financially” (alpha = 0.89). Three other items tapped External social regulation, such as “I work to get the other's approval (e.g. supervisor, colleagues, family, clients)” (alpha = 0.92). Introjected regulation was measured with three items, such as “I work because otherwise I feel bad about myself” (alpha = 0.93). Identified regulation was measured with three items, including “I work because what I do in this job has a lot of personal meaning to me” (alpha = 0.88). Finally, intrinsic regulation was measured with four items. An example item is: “I work because I enjoy this job very much” (alpha = 0.88). All items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Finally, three control variables were included: gender, age, and level of education. As regards the latter concepts, participants could choose from six response options ranging from 1 (primary school only) to 6 (academic degree).

In order to examine whether a six-factor model of motivation would fit the data better than a simpler three-factor model (Gagné and Deci, 2005), we performed two confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). The three-factor model with the items of amotivation loading on the first factor, the items of external materialistic regulation, external social regulation and introjected regulation loading on a second factor (controlled motivation), and the items tapping identified regulation and intrinsic regulation loading on the third factor (autonomous motivation) did not fit the data, χ2(df = 149) = 3,153.25; GFI = 0.62; RMSEA = 0.19 (90% CI = 0.19–0.20); NFI = 0.60; CFI = 0.61. The six-factor model performed considerably better, χ2(df = 137) = 297.81; GFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.05 (90% CI = 0.04–0.05); NFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.98. According to Byrne (2010), these values indicate acceptable to good fit. The fit of the two models differed significantly, Δχ2(df = 12) = 2,855.44, p < 0.001, thus the six-factor model was accepted as the best model.

As individual observations were nested within organizations, the data possessed a multilevel structure. In order to check whether the organizational level accounted for a practically relevant part of the individual-level variance ICC-1 values were computed for all study variables (McGraw and Wong, 1996). Low ICC-1 values (ICC < 0.1) imply that the variables included in the present study do not differ meaningfully across organizations (Chen et al., 2012). In the present study ICC-1 scores ranged from −0.02 to 0.05. Apparently, multilevel analysis of the current data set was neither warranted nor required.

The research model examined in the present study was estimated using structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 21.0 (Arbuckle, 2012). Two models were tested and compared using maximum likelihood estimation procedures. In order to test these models we calculated the mean scores for the subscales of the concepts in the present study. These subscales served as observed indicators of the higher-order latent variables in the model. Model fit was evaluated using the χ2-statistic, the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). The first model to be tested is the full mediation model (cf. Figure 1). In this model the relationships between authenticity at work and the well-being outcomes are fully mediated by the six dimensions of motivation. The second model is the partial mediation model (cf. Figure 1). This model extends the full mediation model with direct relationships between authenticity at work and well-being. For the mediation analysis we applied Preacher and Hayes (2008) bootstrapping procedure. The bootstrap analyses were performed with 2,000 bootstrap samples and the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals were computed. The residuals related to the mediators were allowed to covary (Preacher and Hayes, 2008).

To test our hypotheses we examined the regression paths of the model fitting our data best. Moreover, we employed the Product-of-Coefficient approach (Preacher and Hayes, 2008) to examine the total indirect effect and the specific indirect effects of the possible mediation of motivation on authenticity at work and its relationship with work engagement and burnout.

The means, standard deviations, and correlations for the study variables are presented in Table 1. Two competing models were compared. The first model (the full mediation model) showed marginal fit to the data, χ2(df = 49) = 355.30; GFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.11 (90% CI = 0.10–0.12); CFI = 0.90, with some fit indexes being acceptable fit but others not (Byrne, 2010). The second model (the partial mediation model) performed better, χ2(df = 47) = 257.04; GFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.09 (90% CI = 0.08–0.10); CFI = 0.93, with all indexes meeting their criterion for good fit (Byrne, 2010). The χ2-difference between the two models was significant, Δχ2(df = 2) = 98.26, p < 0.001. Thus, the partial mediation model was preferred to the full mediation model. Finally, all non-significant regression paths were omitted from the partial mediation model. This final model fitted the data well, χ2(df = 52) = 255.60; GFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.09 (90% CI = 0.08–0.10); CFI = 0.93.

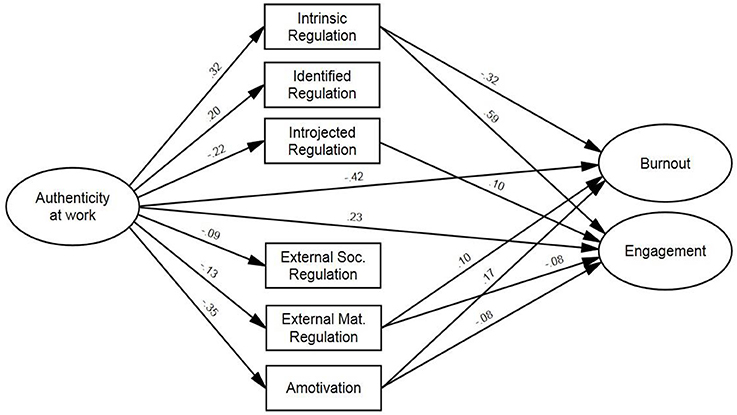

Hypotheses 1a–e stated that the association between authenticity at work and motivational regulation would be contingent on the type of motivational regulation. Specifically, the association between authenticity and motivational regulation should vary with the degree of identification with one's work activities, i.e., this association should be positive for intrinsic and identified regulation (Hypotheses 1a,b), but negative for introjected and external regulation and amotivation (Hypotheses 1c–e). Figure 2 presents the standardized regression paths, showing that authenticity at work was positively associated with intrinsic regulation (b = 0.32, p < 0.01, Hypothesis 1a supported) and identified regulation (b = 0.20, p < 0.01, Hypothesis 1b supported). As expected, authenticity at work was negatively related with introjected regulation (b = −0.22, p < 0.01), external social regulation (b = −0.09, p < 0.05), external material regulation (b = −0.13, p < 0.01), and amotivation (b = −0.35, p < 0.01) (Hypotheses 1c–e supported).

Figure 2. Structural paths of the partial mediation model. Coefficients represent standardized estimates. Non-significant effects are omitted for clarity.

Hypothesis 2 stated that the experienced level of authenticity at work would be positively related to work engagement. In line with the expectations, experienced authenticity was positively associated with engagement (b = 0.23, p < 0.01, Hypothesis 2 supported). Hypothesis 3 stated that authenticity at work would be negatively related to burnout. As expected, low levels of authenticity were associated with higher levels of burnout (b = −0.42, p < 0.01). Thus, not knowing who one is at work and not working in accordance with one own values and beliefs is indeed associated with higher levels of exhaustion and a larger mental distance from work.

We expected that work engagement would be positively associated with intrinsic regulation (Hypothesis 4a) and identified regulation (Hypothesis 4b), and negatively with introjected regulation (Hypothesis 4c), external regulation (Hypothesis 4d), and amotivation (Hypothesis 4e), respectively. Consistent with these notions, intrinsic regulation was indeed positively associated with engagement (b = 0.59, p < 0.01), whereas was engagement was negatively related to amotivation (b = −0.08, p < 0.01) (Hypotheses 4a,e supported, respectively). Contrary to our expectations, introjected regulation was positively rather than negatively associated with work engagement (b = 0.10, p < 0.01; Hypothesis 4c not supported). Furthermore, identified regulation was not significantly related to work engagement (Hypotheses 4b not supported). Finally, Hypothesis 4d stated that external regulation would be negatively related to engagement. This hypothesis was supported for external material regulation (b = −0.08, p < 0.01) but not for external social regulation (b = ns).

We expected negative associations between burnout and autonomous motivation (intrinsic regulation, Hypothesis 5a, and identified regulation, Hypothesis 5b), and positive associations between burnout and controlled motivation (introjected regulation, Hypothesis 5c, and external social and material regulation, Hypothesis 5d) and amotivation (Hypothesis 5e). As expected, intrinsic regulation was negatively related to burnout (b = −0.32, p < 0.01, Hypothesis 5a supported). Amotivation (b = 0.17, p < 0.01) was positively associated with burnout (Hypothesis 5e supported). However, although the associations between identified and introjected regulation and burnout were in the expected directions, these relationships were not significant (Hypotheses 5b,c not supported). Finally, Hypothesis 5d stated that external regulation would be positively related to burnout. Although external material regulation was indeed positively related to burnout (b = 0.10, p < 0.01), this effect was not significant for external social regulation (Hypothesis 5d partly supported).

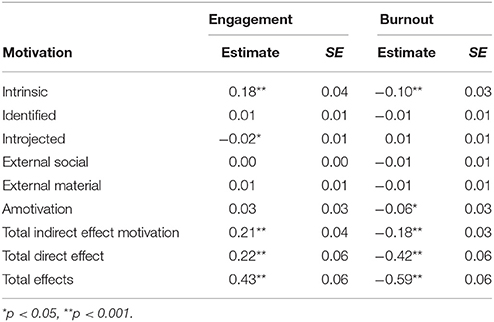

Hypothesis 6 stated that the associations between authenticity on the one hand and well-being (work engagement and burnout) on the other would be at least partly mediated by motivation. Relevant to this hypothesis, Table 2 presents the indirect effects of the six factors of motivation on well-being (engagement and burnout), the total indirect effect of these factors, and the direct effects of authenticity at work on well-being. Partial mediation occurs when the direct, indirect and total effects are all significant. Our results indicate that motivation partially mediated the effect of authenticity at work on work engagement (b = 0.21, p < 0.01) and burnout (b = −0.18, p < 0.01). Table 2 shows that for engagement, the indirect effects of intrinsic regulation (b = 0.18, p < 0.01) and introjected regulation (b = −0.02, p < 0.05) were significant. For burnout, the indirect effects of intrinsic regulation (b = −0.10, p < 0.01) and amotivation (b = −0.06, p < 0.05) were significant. Since not all mediational paths were significant, these findings partly support Hypothesis 6.

Table 2. Indirect standardized effects after conducting bootstrapping for work engagement and burnout.

Drawing on data from 546 financial services professionals and building on OIT (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Deci et al., 2017), this study focused on the association between state authenticity at work and motivation. Moreover, the mediating role of motivation in the relationship between authenticity at work and well-being (that is, work engagement and burnout) was investigated. Using structural equation modeling, our results indicated that self-determined (or “authentic”) motivation indeed partially mediated the relationship between self-reported authenticity at work and well-being. We believe that the four most interesting results of this study are the following:

Firstly, our results revealed that authenticity at work and the six regulation styles as introduced by OIT were significantly related. As expected, the level of experienced authenticity at work was associated positively with two types of autonomous motivation, showing a strong association with intrinsic motivation and a weaker association with identified regulation. This suggests that subjectively experienced authenticity is indeed positively associated with performing “authentic,” self-determined actions, as implied in SDT (Deci et al., 2017; but see Emmerich and Rigotti, 2017). Note that the effects presented in Figure 2 for the associations between authenticity and these two regulation styles are not strong enough to argue that both approaches to examining authenticity yield the same results. Apparently, acting upon self-determined motivations and subjective feelings of authenticity do not necessarily occur simultaneously. Further, authenticity at work was negatively associated with the regulation styles that are part of controlled motivation. Low levels of experienced authenticity were associated with high levels of introjected regulation, external social regulation, external materialistic regulation, and amotivation, with the association between authenticity at work and amotivation being the strongest.

Secondly, self-determined, controlled and amotivation acted as partial mediators of the relationship between authenticity at work and well-being. Our analyses revealed that the indirect effects of these motivational styles accounted for 48.8% of their total joint effects on work engagement. Similarly, for the burnout construct, the indirect effects of the six motivational styles on the association between authenticity at work and burnout accounted for 30.5% of their total joint effects on burnout. Although these results mean that a substantial part of the total effect of authenticity on burnout and engagement is accounted for by motivational regulation, the largest part of the effect of authenticity on well-being is direct. Interestingly, the six motivational factors were more important in predicting work engagement than in burnout. Apparently, the motivational aspect is more relevant for engaged workers than for burned-out workers.

Thirdly, the multiple mediator models used in this study can be used to investigate the relative importance of the included mediators. Comparison of the indirect effects of different mediators reveals which mediator or theory should be considered as the most important (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Our results show that motivational regulation partially mediates the relationship between authenticity at work and well-being. However, closer inspection of the six motivational factors revealed that intrinsic regulation had the largest indirect effects on well-being, affecting both work engagement and burnout (cf. Table 2). These findings suggest that of the six types of motivational regulation examined here, intrinsic regulation is the most important in predicting well-being. Intrinsic regulation is characterized by feelings of joy and a pleasant experience; employees participate in work activities because they really enjoy it. Experiencing these feelings of joy is related to experiencing higher levels of work engagement, whereas lack of these pleasurable experiences is associated with higher levels of burnout. Apparently, employees who perceive high levels of authenticity at work are strongly intrinsically motivated to carry out their work activities. Conversely, employees who feel less authentic are more often amotivated.

Lastly, van Beek et al. (2012) investigated the relationships between self-determined motivation and well-being, reporting findings that were similar to those presented in the current study. In both cases, the associations between motivation and well-being (work engagement and burnout) showed similar patterns, including the positive association between introjected regulation and work engagement. Introjected regulated employees relate their self-worth to their performance at work. They want to avoid negative feelings such guilt and shame, or want to experience feelings such as pride (Assor et al., 2009). Thus, this finding adds further credence to the notion that engaged workers are not exclusively intrinsically motivated, but are also sensitive to external influences.

Four limitations require further discussion. First, this study employed a cross-sectional design, meaning that the causal direction of the associations among authenticity at work, self-determined motivation, and well-being could not be established. However, the present study is among the first to examine the possible associations between authenticity at work and self-determined motivation as described by Deci and Ryan (1985), and in this sense it provides a solid base for longitudinal research designs to build upon in examining authenticity at work as possible antecedent of self-determined motivation.

Second, the present study used self-report measures. This implies that common method variance (CMV) might have biased our findings. However, Spector and Brannick (2009) argued that this bias should not be overemphasized, as CMV among mono-method measures does certainly not always occur. Further, if present, CMV would have led to inflated correlations among all study variables. However, Table 1 shows that the associations among the correlations follow a variable pattern and that—in spite of having a large sample size of 546 participants—still several null correlations were present. Thus, all in all there are no indications that CMV has biased our findings substantially.

Thirdly, it is worth noting that of the three authenticity dimensions, the reliability of the accepting external influence dimension was the lowest (alpha was 0.65). In other studies drawing on this measure of authenticity (e.g., van den Bosch and Taris, 2014a; Metin et al., 2016), accepting external influence was the least reliable of the three dimensions as well. This may be due to the somewhat ambiguous nature of this concept. On the one hand, being subject to (and accepting) the influence of others at work may signify problems in terms of authenticity. On the other hand, accepting such influences is also a sign of being well-adjusted to the job, since working virtually always means that one must accept that others—such as bosses, colleagues, and customers—will affect one's behavior. In this sense, the conceptual status of this dimension (while at work, is it bad or good to accept the influence of others?) is unclear, which may be reflected in the relatively low reliability of this dimension. Indeed, this reasoning suggests that the other two authenticity dimensions (self-alienation and authentic living) may be stronger indicators of authenticity at work (cf. van den Bosch and Taris, 2014a).

Finally, our data were collected among a relatively homogenous group of workers. All participants worked in the financial services industry. Since all participants shared a very similar occupational background, it is possible that this has led to restriction-of-range effects in the study variables. This implies that effects will be conservatively estimated, and that in more heterogeneous samples stronger effects might be found.

We believe that this study has several important theoretical and practical implications. First, the present findings extend the scarce theoretical knowledge on the concept of state authenticity at work in relation to SDT. Two recent studies on authenticity at work (van den Bosch and Taris, 2014b; Metin et al., 2016) examined the nomological network of this concept in the context of work. This study confirms the importance of authenticity in the work context, showing that subjectively experienced authenticity at work can be related to the six different regulation styles proposed by SDT (Deci et al., 2017), supporting the assumption that authenticity at work is a possible antecedent of motivation.

Self-Determination Theory states that intrinsically motivated behaviors are the prototype of self-determined actions. These fully self-determined actions emerge directly from the self (Ryan and Deci, 2000), suggesting that employees who can be fully themselves at work—i.e., who are authentic—will show higher levels of intrinsically motivated behavior. The present findings support this notion. This means that workers who stay in touch with their self, work in accordance with their own values and beliefs, and do not accept external influence against their will show higher levels of intrinsic motivation behavior. If employees feel less authentic the level of intrinsically motivated behavior will decrease. Less authentic employees show higher levels of non-self-determined behavior.

As for the practical implications of this study, our results indicate that low levels of experienced authenticity at work show adverse effects on well-being and are positively associated with qualitatively lower forms of motivation (cf. Gagné and Deci, 2005). Therefore, it seems important for organizations to screen their staff for employees who act on the basis of controlled motivation. Since we believe that state authenticity at work results from the congruence between a person and his or her environment, lack of authenticity might be the result of a bad employee-job fit. To improve this fit, organizations could either adjust the content of the jobs of inauthentic employees or transfer the employee to another job—either within or outside the organization.

Since intrinsically motivated workers experience pleasure in their jobs, it can be argued that authentic workers are happy workers. On the other hand, inauthentic workers show signs of amotivation, relatively high levels of burnout, and relatively low levels of work engagement. These findings stress the relevance for employees of finding or shaping a job in such a way that they feel authentic at work. One way of accomplishing this could be to engage in job crafting behaviors. This is “a form of proactive work behavior that involves employees actively changing the (perceived) characteristics of their jobs” (Rudolph et al., 2017, p. 112). This sort of behavior need not result in major changes in the job content. For example, workers may suggest changes to optimize the workflow (which could reduce the effort needed to conduct their tasks), may take on additional responsibilities (which could make their job more interesting and challenging), or even just reinterpret the characteristics of their jobs without making any objective changes (cognitive reappraisal; e.g., a worker may realize that the job is important and that its results may significantly affect the lives of others). Since job crafting is initiated by a worker themselves, job crafting is likely to improve the match between the job and the worker—i.e., this should result in higher levels of experienced authenticity.

Alternatively, workers may attempt to negotiate personal, “idiosyncratic” deals (I-deals) with their employer about their career development (Kroon et al., 2016). By openly communicating with their manager about their mutual wishes for career development, employees may be able to steer their career toward jobs that fit their “true selves” better. The importance of improving authenticity in organizations is underlined by findings of an earlier study by van den Bosch and Taris (2014b). This study provided some evidence that lack of authenticity is related to poor in-role performance. These findings stress the importance of developing interventions to promote authenticity in the organization; at the very least they underline the importance of not ignoring employees who feel inauthentic. Note that lack of authenticity is not only salient for the organization (due to the lower performance of inauthentic workers), but also for individual workers, since lack of authenticity at work is related to lower well-being. Therefore, such interventions should benefit both the organization and their employees.

The present study examined the relations among authenticity at work, various types of motivation and well-being, revealing that authenticity is positively related to more intrinsic forms of motivation and negatively to more extrinsic forms of motivation. Moreover, authenticity and more intrinsic forms of motivation were associated with better well-being (burnout and work engagement). Since motivation, burnout and engagement are all associated with work performance, organizations are well-advised to monitor the level of experienced authenticity among their employees.

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed about the goal of the study before actually participating. Participation was voluntary and anonymous and participants could withdraw from the study whenever they wanted. No particularly sensitive topics were involved, participants were not subjected to deception and completed a non-invasive questionnaire. According to our university's research policy, this sort of research is exempted from approval from our faculty's Ethical Research Committee.

TT and RVdB were both involved in conceptualizing the study, the data analysis, and writing the report. RVdB was further responsible for the data collection.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Assor, A., Vansteenkiste, M., and Kaplan, A. (2009). Identified and introjection approach and introjection avoidance motivations in school and in sports: the limited benefits of self worth strivings. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 482–497. doi: 10.1037/a0014236

Baruch, Y., and Holtom, B. C. (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 61, 1139–1160. doi: 10.1177/0018726708094863

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Chang, C., and Chiu, J. (2009). Flight attendants' emotional labor and exhaustion in the Taiwanese airline industry. J. Serv. Sci. Manage. 2, 305–311. doi: 10.4236/jssm.2009.24036

Chen, Q., Kwok, O., Luo, W., and Willson, V. L. (2012). The impact of ignoring a level of nesting structure in multilevel mixture model: a Monte Carlo study. Struct. Equ. Model. 17, 570–589. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2010.510046

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., and Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 4, 19–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

Emmerich, A. I., and Rigotti, T. (2017). Reciprocal relations between work-related authenticity and intrinsic motivation, work ability and depressivity: a two-wave study. Front. Psychol. 8:307. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00307

Gagné, M., and Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 26, 331–362. doi: 10.1002/job.322

Gagné, M., Forest, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Crevier-Braud, L., Van den Broeck, A., Aspeli, A. K., et al. (2015). The multidimensional work motivation scale: validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 24, 178–196. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.877892

Kernis, M. H., and Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: theory and research. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 283–357. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38006-9

Kroon, B., Freese, C., and Schalk, R. (2016). “A strategic HRM perspective on i-deals.” in Idiosyncratic Deals between Employees and Organizations: Conceptual Issues, Applications and the Role of Co-workers, eds M. Bal and D. M. Rousseau (New York, NY: Routledge), 73–91.

McGraw, K. O., and Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlations coefficients. Psychol. Methods 1, 30–46. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30

Metin, U. B., Taris, T. W., Peeters, M. C. W., van Beek, I., and van den Bosch, R. (2016). Authenticity at work: a job-demands resources perspective. J. Manage. Psychol. 31, 483–499. doi: 10.1108/JMP-03-2014-0087

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., and Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: a meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Voc. Behav. 102, 112–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Schaufeli, W. B., and Bakker, A. B. (2010). “The conceptualization and measurement of work engagement,” in Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research, eds A. B. Bakker and M. P. Leiter (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 10–24.

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., and Jackson, S. E. (1996). “Maslach burnout inventory – general survey,” in The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Test Manual, 3rd Edn,.eds C. Maslach, S. E. Jackson, and M. P. Leiter (Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press), 22–26.

Schmid, P. F. (2005). “Authenticity and alienation: towards an understanding of the person beyond the categories of order and disorder,” in Person-Centred Psychopathology, eds S. Joseph and R. Worsley (Ross-on-Wye: PCCS), 75–90.

Spector, P. E., and Brannick, M. T. (2009). “Common method variance or measurement bias? The problem and possible solutions,” in The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, eds D. A. Buchanan and A. Bryman (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 346–362.

Taris, T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., and Shimazu, A. (2010). “The push and pull of work: the differences between workaholism and work engagement,” in Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research, eds A. B. Bakker and M. P. Leiter (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 39–53.

Taris, T. W., Ybema, J. F., and van Beek, I. (2017). Burnout and engagement: Identical twins or just close relatives? Burnout Res. 5, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2017.05.002

Toor, S., and Ofori, G. (2009). Authenticity and its influence on psychological well-being and contingent self-esteem of leaders in Singapore construction sector. Construct. Manage. Econ. 27, 299–313. doi: 10.1080/01446190902729721

van Beek, I., Hu, Q., Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., and Schreurs, B. H. J. (2012). For fun, love, or money: what drives workaholic, engaged, and burned-out employees at work? Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 61, 30–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00454.x

van den Bosch, R., and Taris, T. W. (2014a). Authenticity at work: The development and validation of an individual authenticity measure at work. J. Happiness Stud. 15, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10902-013-9413-3

van den Bosch, R., and Taris, T. W. (2014b). The authentic worker's well-being and performance: the relationship between authenticity at work, well-being, and work outcomes. J. Psychol. 148, 659–681. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2013.820684

Van den Broeck, A., Schreurs, B., De Witte, H., Vansteenkiste, M., Germeys, F., and Schaufeli, W. (2011). Understanding workaholics' motivations: a self-determination perspective. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 60, 600–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00449.x

Keywords: Authenticity, burnout, SDT, work motivation, work engagement

Citation: Van den Bosch R and Taris T (2018) Authenticity at Work: Its Relations With Worker Motivation and Well-being. Front. Commun. 3:21. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00021

Received: 01 January 2018; Accepted: 08 May 2018;

Published: 24 May 2018.

Edited by:

Annamaria Di Fabio, Università degli Studi di Firenze, ItalyReviewed by:

Emanuela Ingusci, University of Salento, ItalyCopyright © 2018 Van den Bosch and Taris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Toon Taris, t.taris@uu.nl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.