- 1Department of Communication, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, United States

- 2Scripps College of Communication, Ohio University, Athens, OH, United States

- 3Cancer Justice Network, Cincinnati, OH, United States

In this study, we analyze data from an ongoing academic–community collaboration targeted at conceptualization and delivery of a patient navigation intervention for cancer prevention. Echoing overall United States trends, the region under study is earmarked by significant socioeconomic and racial disparities in cancer outcomes. While there is a large body of research on the use of patient navigation across the continuum of cancer care, the role of communication in shaping navigation is unclear in the literature. Responding to this gap, we use the culture-centered approach to document how community-based “lay” patient navigators’ local knowledge and cultural expertise shaped the scope and meanings of patient navigation for a predominantly African-American population. Qualitative data in the form of navigator interviews, participant observation of navigation, and research team members’ reflexive journals were used to document how the definition and scope of navigation were re-inscribed by community navigators. While navigation was initially equated with screening promotion, interaction with community members led to the development of more listening-focused and structural barrier-focused conceptualization of patient navigation. Finally, we discuss the implications and contributions and limitations of this study.

In this paper, we report initial results from a current academic–community collaborative research project geared toward the development of a community-based patient navigation program for cancer screening and treatment among underserved patients that reside in the southwestern Ohio, Greater Cincinnati region. Patient navigation has been advocated as an innovative, barrier-focused intervention addressing the significant socioeconomic and racial disparities in cancer mortality in the United States, by identifying (and reducing) patient-level barriers in access to care, tracking patients through the continuum of cancer care, and “reducing the number of patients lost to follow-up” (Wells et al., 2008, p. 2001). The term “patient navigation” was introduced by Harold Freeman in 1990 to describe his historic partnership with the American Cancer Society (ACS), wherein low-income women in Harlem, New York were provided assistance in obtaining preventative cancer services (Freeman, 2006a; Freeman and Rodriguez, 2011). Since then, the body of knowledge on patient navigation has grown steadily and the term has been operationalized to refer to “any type of service that assists individuals in overcoming obstacles from screening to treatment and in coping with challenges during survivorship” (Wells et al., 2008, p. 2001).

Residents of Hamilton county, including those that live in Greater Cincinnati experience some of the largest racial disparities in cancer outcomes in the state of Ohio, with racial disparities in (female) breast and colorectal cancer mortality being nearly twice as high for African-Americans as it is for Whites (National Cancer Institute, 2017). No existing patient navigation programs serve the urban metropolitan area under study; however, patient navigation programs exist elsewhere in the state (Paskett et al., 2012). Furthermore, within the robust literature on patient navigation, there is little to no research that explores the dynamics of patient navigation from a health communication perspective.

This paper responds to this gap in knowledge by outlining a fundamentally communicative vision of patient navigation. Responding to the call for designing community-based, culturally competent models for patient navigation (Braun et al., 2008; Jandorf et al., 2013), we draw from the conceptual model of the culture-centered approach (CCA) (Dutta, 2007) to investigate how local knowledge and cultural expertise can shape the scope of navigation programs. The primary scholarly contribution of this paper is the documentation of how a communication theory-based perspective can enrich the process of patient navigation for cancer. We begin by reviewing relevant literature on patient navigation, followed by a brief overview of the CCA. Next, we outline the key elements of the research design of our community-based project, which is then followed by reporting of our initial results and the practical application of our findings.

Patient Navigation: A Brief Overview

The concept of patient navigation emerged in the wake of the findings of the American Cancer Society National Hearings of Cancer in the Poor, which were conducted in seven American cities in 1989 (Freeman and Rodriguez, 2011), and published in the form of a landmark report titled Report to the Nation: Cancer in the Poor (Wells et al., 2008). The findings represented an early validation of what is now commonly known and understood about cancer care delivery: that poor Americans faced significant financial, logistical, and sociocultural barriers in accessing cancer care services (Dohan and Schrag, 2005; Wells et al., 2008).

As a response to the findings, Dr. Harold Freeman, then the President of the ACS, created the first patient navigation program in Harlem, New York in 1990, focusing on reducing breast cancer mortality among low-income, and predominantly African-American women in the community (Freeman, 2006b). Before this intervention, nearly half of the 606 patients treated at the Harlem Hospital Center presented with stage 3 and 4 disease, with a 5-year survival rate of 39%. Moreover, all these patients reported low economic status and half had no health insurance (Freeman and Rodriguez, 2011). Freeman’s intervention, which included the provision of free/low-cost mammograms to facilitate early screening, and guidance for patients through diagnosis and treatment procedures had remarkable success: the number of patients presenting with early stage cancer (0 and 1) increased from 6 to 41%, those that presented with stage 3 and 4 cancer reduced to 21% (from 49%), and the 5-year survival rate skyrocketed to 70%. The dramatic success of this intervention, and others following it, led to the widespread recognition of patient navigation as an effective intervention for reducing racial and socioeconomic disparities in cancer mortality, the establishment of a national model of patient navigation through the ACS, and eventually, a Congressional Act, the Patient Navigator Outreach and Chronic Disease Prevention Act of 2005, which authorized federal grants toward developing navigation programs nationwide (Wells et al., 2008).

Congressional endorsement of the patient navigation model has led to support from three separate federal governmental initiatives and several private foundations (Paskett et al., 2011). Patient navigation has emerged as a mainstream intervention approach to care across the cancer continuum, with some studies reporting between 60 and 80 independent patient navigation programs currently in operation in the United States and Canada, and nascent interventions beginning in Europe and Australia (Paskett et al., 2011). Moreover, the patient navigation model has been extended to other chronic conditions besides cancer, especially in disease conditions that have similar patterns of racial/socioeconomic disparities in outcomes (Dohan and Schrag, 2005; Fischer et al., 2007).

There is now considerable evidence attesting to the effectiveness of navigation. Paskett et al. (2011) reported that results from multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of navigation programs showed clear and significant impact of navigation in boosting screening rates for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancers. Several other descriptive and cohort studies have also found ample evidence for the efficacy of patient navigation in reducing negative health outcomes across the spectrum of care (Paskett et al., 2011). However, there still exists significant ambiguity in defining the scope of patient navigation.

Most, if not all of the systematic reviews of patient navigation programs report significant variations in how navigation is defined, conceptualized, and operationalized across interventions. This in itself is not surprising. One of the fundamental challenges in investigating the efficacy of navigation programs lies in the fact that a wide swath of caring, nursing, social work, community health work, and health education practices are often subsumed under the broad umbrella term “navigation” (Dohan and Schrag, 2005; Pedersen and Hack, 2011). While such variations make it harder to isolate the impact of navigation in a RCT, these differences attest that the scope and ambit of navigation is context dependent, and is likely to vary based on stage of cancer care, educational and institutional affiliations of navigators, and even individual patient preferences (Freeman, 2006a). These differences can also be to some extent attributed to the complex and fragmentary nature of healthcare delivery in the United States, the vagaries of which are compounded for patients that belong to racial and ethnic minorities and lower socioeconomic groups.

Furthermore, the biomedical literature on navigation is unanimous in its recommendation for standardizing “what navigators do” (Parker et al., 2010) even as, somewhat paradoxically, there is simultaneous consensus that models of navigation are shaped by the institutional, social, and cultural roles of the navigator (Pedersen and Hack, 2011): it goes without saying that a nurse-led navigation program will be significantly different, in terms of resources and training required, communication dynamics between navigator and patient, etc., than a program led by social workers, community health workers, or even community-based “lay” navigators (Calhoun et al., 2010). It would seem that the definition of patient navigation has fuzzy exclusion criteria, given the range of interventions that claim the title. This is particularly acute when considering how navigation has been variously indexed as a “community-centered approach” (Freeman, 2006b), a “community-based” strategy (Freeman, 2006a), and a “culturally competent strategy” (Fischer et al., 2007). We now explore claims around cultural competence and “community-centered” research in detail.

Navigation As a Culturally Competent, Community-Based Intervention Model

Patient navigation programs have been cast within the broader spectrum of community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Braun et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2009) and culturally tailored interventions (Percac-Lima et al., 2013) that have gained traction within policy and academic circles. Freeman’s original intervention upended the status quo in that it opened up oncological healthcare to sections of the population that had, up until that point (and to a large extent, even today) been systematically excluded from these services. While it is certainly true that the Harlem intervention, and some of the more current programs modeled around it are run in communities, that in itself does not necessarily mean the same thing as being “community-based” (Peterson and Gubrium, 2011).

It is not altogether surprising that biomedical research or research conducted at the behest of large medical institutions is opaque to the differences between doing medical/health research in communities and research with them—after all, none of the published research on navigation acknowledges the inherent power dynamics embedded in interactions between medical teams and low-income patients. Our research, grounded in the critical praxis of the CCA, builds on Freeman’s intervention in envisaging the possibilities of significant community ownership of patient navigation. Based on the observation that terms such as culture and community, when embedded into research projects, are often conflated (Peterson and Gubrium, 2011) or worse, deployed as academic dog-whistles for referencing the poor and/or ethnic minorities (Airhihenbuwa and Obregon, 2000), our project seeks to document the vigilance, reflexivity and commitment required in attempting authentic, empathetic collaborative research with marginalized populations. In the next section, we outline how we define the term culture, community, and participation within the culture-centered research framework.

The CCA

The CCA represents a radical departure from traditional health communication theorizing, in that it is fundamentally committed to working in solidarity with marginalized communities and their struggles with health, voice, access, and equity (Dutta, 2008). This praxis-oriented research tradition employs a dialogic, participatory framework to uncover how marginalized communities (a) define health problems through their lay/local etiologies (cultural dimension), (b) identify the structural barriers that impede health (structural dimension), and (c) challenge barriers to health through agentic acts (agency dimension). In this approach, solutions to health challenges are co-constructed with community members. A foundational premise of this approach is that in marginalized contexts, individual and communities’ health represents a complex interplay between structures (broad institutional landscapes that influence health) and individual agency (related to ability, or the inherent quality of acting with purpose). Structures—like the societal organization of healthcare, availability of medical facilities, etc., enable or constrain individual choices and motivations to enact healthy behaviors. Culture, the third pillar of the approach, is the via media into this double dialectic between structure and agency. Cultural articulations of health provide opportunities to witness how communities negotiate structural barriers to health through individual acts of agency. This non-interventionist conceptualization of culture as an entry point to understanding local meanings of health in communities represents the “centering” within the CCA. The principle of dialogic co-construction lies at the heart of culture-centered methodology, as researchers engage in reflexive co-construction of knowledge with communities, who for their part, are thought of as cultural experts that possess requisite expertise about their communities. It is important to note that this operationalization of culture is radically different (even though it is often confused) with the notion of “culturally sensitive” health interventions.

Cultural Sensitivity versus CCA

Although delivering healthcare services in a culturally competent fashion is now uniformly recognized as a benchmark of healthcare quality in general (Saha et al., 2008), there is an agreement that culturally competent care is an important step in addressing deep-set racial and ethnic disparities in health and healthcare (Betancourt et al., 2003). While the acceptance of the formative role of culture in shaping experiences with healthcare and public health interventions is heartening, it is important to note that not all “cultural” approaches are the same. Definitional issues, including how culture is to be defined within an intervention (Basu and Dutta, 2007), who gets to define it (Dutta, 2007), how to operationalize cultural sensitivity (Resnicow et al., 1999) and cultural competence (Betancourt et al., 2003) are important considerations that shape what interventions look like.

As Peterson and Gubrium (2011) point out, the terms “community” and “culture” are commonly conflated within CBPR projects, given that much of this brand of work is done in (as opposed to done “with”) communities that include racial and ethnic minorities.1 This conception of culture as an exotic collective (Airhihenbuwa and Obregon, 2000), as an adjective descriptor of individuals that share group membership based on (minority) ethnic and/or racial identification then opens the door for “culturally sensitive” health communication programs, key characteristics of the community (read: culture) are identified, and accordingly, health messages that are responsive to the identified characteristics are deployed within the community, often using methods of cultural tailoring and personalization (Bull et al., 1999; Kreuter and McClure, 2004; Kreuter et al., 2005). Such programs can be “participatory” to the extent that intervention targets are often incorporated within the research design. However, there seems to be little room for communities to challenge how they are characterized or how variables deemed “relevant” to their cultures are chosen.

In differentiating between this approach, labeled “cultural sensitivity,” Dutta (2007) offers systematic criteria that distinguish it from a “culture-centered” approach. One principal criterion of difference is the conceptualization of culture: in the former approach, the objective is to create targeted, or tailored solutions for communities based on the “most relevant cultural characteristics of communities identified by the researcher” (p. 309). The CCA differs on several counts: (a) culture is not pre-identified, but emerges through co-construction with participants and (b) this dynamic, ever-changing account of culture is considered in intersection with structural processes that surround the culture and individuals’ agency in fighting for health (Dutta, 2008). Contrary to the emphasis on variables, measurement, and behavior change in the cultural sensitivity paradigm, the CCA envisions a more radical, emancipatory view of culture in health communication, with an emphasis on writing “theory from below,” based on subaltern communities’ inherent agency to negotiate structural barriers to health.

Culture-Centered Methodology and Dialogic Co-Construction

The research problem at the heart of this study is exploring how community navigators negotiated tensions between the received view of patient navigation (i.e., Freeman’s highly successful model) and their indigenous or lived-experience based recommendations for successful patient navigation in their communities. In other words, the academic literature on patient navigation was introduced to the navigators with the express idea that this elite, academic knowledge would be locally tested, modified and when necessary, challenged. Within culture-centered methodology, such dialogic co-construction of expert knowledge is a starting point toward the establishment of truly participatory, reflexive, community-owned theory building. For instance, Dutta and Pal (2010) theorize the role of dialog with subaltern communities as providing “discursive openings for the interrogation of dominant sites of knowledge production” (p. 363). Similarly, Dutta and Basu (2008) provide a theoretical and methodological warrant for dialog with marginalized communities in highlighting how co-construction allows for local meanings of health to emerge, challenging elite knowledge and categories.

This paper addresses the ways that received academic knowledge about patient navigation was reshaped based on dialogic co-construction of the local relevance and meaning of navigation. This process highlights how co-construction, as a dialogical, participatory commitment creates communicative pathways for addressing the barriers that impinge on health within marginalized contexts (Dutta, 2014). This research begins the process of culturally centering oncological patient navigation by engaging with what navigation means for community navigators, and their conceptualization of the scope and reach of such an intervention.

RQ1: What local meanings of patient navigation emerged through the process of navigator training and community interaction?

RQ2: How did these localized, emergent understandings of navigation uniquely shape the early conceptualization and delivery of this navigation model?

Methods

The data reported here was obtained at the early stages of an ongoing academic–community collaboration with a community-based health organization called the Cancer Justice Network (CJN). Based in Cincinnati, OH, USA, CJN seeks to “[unite] agencies and people that serve the poor and minorities in Cincinnati, OH, USA…” (Cancer Justice Network, 2017). The director of the CJN, Author 4, articulated his vision for creating a patient navigation program targeting marginalized Cincinnati residents, and expressed need for assistance in establishing protocols and standards for the development of a program modeled on the pioneering work of Harold Freeman, who developed the patient navigation program in Harlem, NY, that has since become the national gold standard for community-based oncological patient assistance.

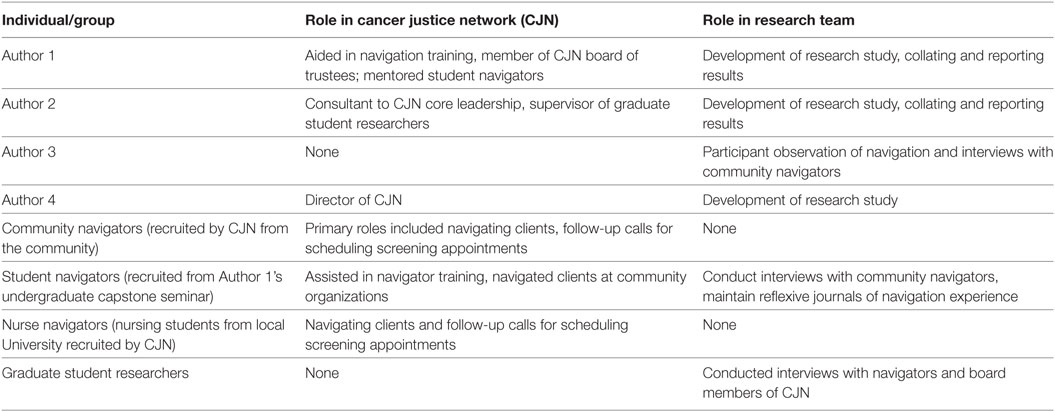

Responding to this community-articulated need, Authors 1 and 2 laid the groundwork for a collaborative research project through immersive ethnographic observation of the CJN. Author 3, a graduate student, also collected data in the form of participant observation and in-depth interviews with community members. The IRB at the University of Cincinnati exempted this study from the ethics review process. While the IRB at the University of Cincinnati deemed that the study did not require written consent, in the spirit of ethical research procedure, we informed participants about the voluntary nature of participation, as well as the confidentiality and privacy measures in place. In addition, no identifying data were collected during this process: all participant names reported have been changed. Oral, informed consent was obtained from all research participants. A team comprising professionals, academics, students, and volunteers was involved in the navigation process. The research team was assembled from of a subset of this larger group (see Table 1). In what follows, we outline the research design that guided this project, providing details about the community organization, data collection, and data analysis procedures.

The CJN

The academic–community collaboration in consideration here began in early 2016, when CJN was still a nascent organization concerned with the identification of key partners, agencies, physicians, volunteers, potential navigators, and other community resources required to develop a navigation program. The leadership group drew from years of personal experience with cancer—many of them were already informally “navigating” friends and family with cancer—that snowballed into the creation of this organization. By the end of the year, the CJN had established linkages between primary care physicians, oncologists, testing centers, federally qualified community health centers, privately owned cancer screening centers, local church-based and other charitable community organizations, insurance agencies, and a pool of potential patient navigators. A comprehensive list of the agencies involved in the network is available on the CJN website (http://www.cancerjusticenetwork.org).

In late 2016, the CJN began piloting its patient navigation program in conjunction with its affiliates. Each week, a CJN team comprising of navigators, a physician, an insurance representative, an employee of a community health center, a member of the research team, and the director of CJN gathered at a local charitable organization during the weekly meal service. Most partnering community organizations offer a weekly meal service for low-income and disenfranchised members of the community. These gatherings typically serve between 50 and 250 people, depending on the size of the organization. While this study’s scope did not include collecting demographic data about the community served, our personal observations confirmed that the majority of the community served was African-American. The rationale here was that this population was likely to “fall through the cracks” for cancer screening and prevention and represented the group that would most urgently benefit from patient navigation.

During (or occasionally after) the meal service, the CJN team came on to the “stage” to talk about the navigation program, which included an overview of the organization, and a short physician-led presentation about cancer and the life-saving potential of early screening and detection. Following this, patient navigators sat at assigned tables, explaining the program in detail, answering questions, and providing clients with resources for accessing free mammography and colorectal cancer screening opportunities in their community. Navigators offered assistance in making appointments for screening, traveling with clients to medical appointments, helping with Medicaid eligibility determination, and answering questions about the program.

This community-based approach required significant personnel coordination, logistical planning, and much frustration in the initial period, owing to low “success rates” of patients signing up for screening and navigation. However, this approach also represents the project’s commitment to being a truly community-based organization, not affiliated with a hospital or a healthcare institution. As we detail in our results section, our participants’ negative associations of and experiences with healthcare institutions meant that our community locus was important.

Data Collection

The leadership group of the CJN believed that health communication specialists could be of assistance to the group by observing the interactions between patient navigators and community members, with the goal of giving a systematic account of communication dynamics in the navigation encounter, and conceptualizing theoretically valid training to potential navigators. In an initial meeting, members of CJN leadership presciently observed that even in the wealth of literature on patient navigation, there was very little documentation on what communicative qualities made for an effective navigation relationship. This community-articulated agenda formed the basis of the research questions guiding this study (articulated earlier and repeated here).

RQ1: What local meanings of patient navigation emerged through the process of navigator training and community interaction?

RQ2: How did these localized, emergent understandings of navigation uniquely shape the conceptualization and delivery of our navigation model?

In responding to this prompt, a team of researchers (see Table 1) collected data in the form of interviews with patient navigators, summaries of participant observation of navigation, textual material (training documents produced by the CJN), and self-reflexive journals. Authors 1 and 2 also led service learning courses (undergraduate capstone and graduate seminar, respectively) that were dedicated to patient navigation. In these courses, CITI-trained students volunteered with the CJN, participated in the initial navigation meetings with community members, attended the navigation training sessions, created brochures and training materials, and did one-on-one interviews with navigators about their expectations and definitions of navigation. No identifying data were collected during this process: all participant names reported have been changed.

The research team conducted one-on-one interviews with community navigators [n = 6, four African-American (one male, three female) and two Caucasian (both female)], nurse navigators (n = 3, all three Caucasian women), and board members of the CJN (n = 2, both men, one African-American, and one Caucasian) (see Table 1 for details). Interviews were transcribed for analysis, resulting in approximately 60 pages of transcribed text.

Participant observation of navigation interactions was conducted exclusively by Author 3, and was guided by a participant-observation rubric developed by the research team. Author 3 divided her time observing each of the navigators interact with community members, and observed over 200 community–navigator interactions across 6 months. Of these, nearly 55 interactions resulted in engagement and discussion that could be recorded in the observation rubric. Initially, a significant number of community members declined to speak with navigators, or expressed disinterest. Over time, as navigators became familiar to community members, this happened less frequently.

Data Analysis

Our data analysis was informed by the tenets of the CCA, in that it borrowed from ethnographic/qualitative analysis methods (Zoller and Dutta, 2008), specifically constructivist grounded theory-based analysis (Charmaz, 2006) and iterative thematic analysis based on constant comparison of data (Tracy, 2012). Our corpus included 60 pages of interview transcripts, 55 summaries of participant observation, textual material, and self-reflexive journals. We cross-pollinated and triangulated across the different kinds of data, rather than analyzing them in isolation; the different data points informed each other (Cresswell, 2003). Our analysis documents the evolution in community-based navigators’ perceptions around patient navigation, in the process of establishing a new patient navigation program. Here, we elaborate on a temporal evolution in thinking about navigation: while our navigators initially were of the belief that (a) patient navigation [was] equated with screening promotion, over time, they broadened their conceptions in thinking of (b) patient navigation as invitation to dialog, and in time, even explored the possibilities of (c) patient navigation as a structural intervention.

Results

In this section, we document the emergence of a locally relevant, culturally centered, and community-specific notion of patient navigation within the CJN. Through their interactions with clients, recognition of existent barriers to care, and low success rates in scheduling preventive screenings with community members, navigators, organization leaders, volunteers, and academic partners sought to develop more dialogic modes of patient navigation. Our three themes describe this emergent view.

Patient Navigation Equated with Screening Promotion

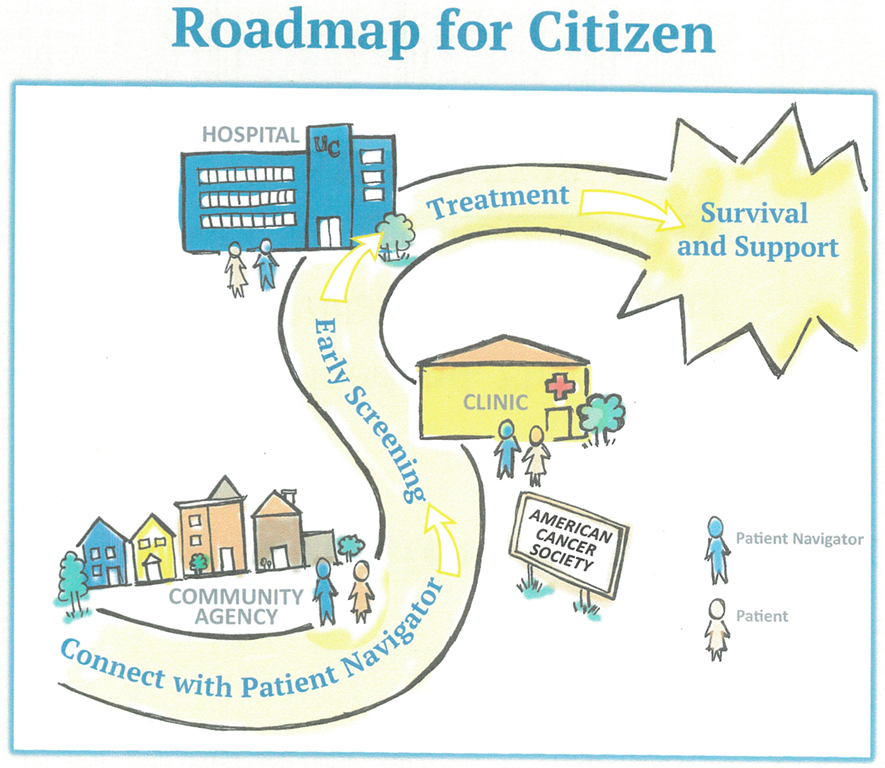

Early in the CJN process, many navigators seemed to equate navigation with promoting cancer screening and facilitating access to those screenings. The focus on screening was the most direct imprint of Freeman’s Harlem model, and was consciously imported into the training documents and mission statements of the CJN intervention. For instance, the training document packet distributed to the community navigators unequivocally stressed the importance of medical access. Clippings of training documents from the Harold Freeman Navigation Institute, included in the CJN packet, stated that one of the primary objectives of navigation outreach was to “identify barriers into the health system.” A diagrammatic representation (Figure 1) of the suggested patient navigation roadmap of the CJN established that navigation involved three steps (1) meeting community members at local agencies and non-profit organizations (where navigation/education was to be provided) and (2) scheduling screening services and transportation for interested community members, and (3) facilitating the subsequent transition to treatments, when needed.

Given the central focus on promoting screenings, early in the navigation process, navigators tended to start their interactions with community members by talking about cancer in a non-dialogic, even didactic manner. Initially, some novice navigators chose to not introduce themselves or their role as a navigator at all. These conversations often began with questions, such as, “have you been examined for cancer?” or “do you need a cancer screening?” One navigator began the conversation at the table with, “does anyone want to have a screening?” This opening line was met with confused looks from the community members and several members saying, “no” or “I’m not interested.” As noted previously, this screening-based approach did not lead to much dialog from the audience. Interviews with community-based and student volunteer navigators revealed how centrally to their purpose, they viewed screening promotion. Consider this interview excerpt by Camille,2 a community navigator, as she discussed her understanding of the navigator role:

I see my role as educating the community about screening services that are available for free. There may not be enough awareness about the fact that it comes at no cost to them. That’s my role as a navigator—to provide information about these services that they may not know about, and help them make appointment for screening at Crossroads [a federally qualified health center].

Here, Camille’s understanding centers around creating awareness about screening, and scheduling appointments at the local partnering health center that was meant to the first contact point for potential patients. This conception is consistent with the recommendations of the Freeman model (Freeman and Rodriguez, 2011), specifically the Harlem study, where patient navigation began with recruitment of patients. However, unlike that situation, where recruits were already in the hospital setting, the CJN starts by meeting community members within the community. Therefore, the navigator has additional work to do in convincing community members that it is important to think about cancer and to get screenings.

A majority of the navigators initially used a didactic stance to emphasize the importance of screening, and in turn, the role of the navigator. Here, there was little realization or focus on the need for dialog or listening to client perspectives. The central focus on promoting the need for screening proved challenging:

For me, navigation begins with a discussion about why cancer is serious and how to act to prevent it. For this, it is important to inform patients about available services in time. I felt that a lot of the community members listened to the presentations and my information with interest, and asked some questions, but when it came to scheduling the screenings, there were not too many takers. —Denise, nurse navigator.

When interviewed, many navigators expressed concerns about the awkwardness of the interactions. As several members of the research team reported, some nursing students who navigated patients mentioned that the “environment did not seem like the right place to discuss something as intimate as cancer at a nicer dinner. Cancer is very personal and the process can be emotional, so it can be a hard topic to discuss with someone you barely know over dinner.” The nursing student navigators described a navigator who was mistaken for a church volunteer serving dinner. Navigators often wondered if community members understood why navigators were sitting at the table or knew that their goal was to promote screening.

After a few of the early sessions, even the community navigators who had prior experience with navigation and cancer treatment had concerns that community members seemed resistant to talking about cancer. They noticed that it was uncomfortable to raise the topic of cancer at the dinners. They also mentioned that women may be uncomfortable talking to men about male-specific cancers and vice versa.

The use of community-based, “lay” navigators created another challenge, as navigators had to walk a fine line when it came to discussing medical procedures and concerns with potential patients. As opposed to navigation programs that are housed within healthcare institutions and staffed by healthcare professionals, community-based navigation programs often run up against technical and ethical limits to how much medical information they can share with potential patients. Navigators at CJN were trained to unequivocally refuse to offer medical opinions, to refrain from answering questions pertaining to risks, screening procedures, and specific cancer-based questions. Instead, they were supposed to use the opportunity to introduce clients to the CJN’s chief physician to answer questions. A physician affiliated with the CJN, open to taking on new patients, was present at every navigation session.

When confronted with a technical question about cancer, or a consultation about a skin growth, navigators had to communicate their lack of knowledge/inability to respond to the question, while maintaining the rapport with the individual with the question. Participant observation revealed that initially, some navigators would simply state, “I am not permitted to answer medical questions,” which, while technically accurate, had the tendency to shut down the conversation. Navigators who used this method to explain that they could not answer the community members question were often met with silence or disengagement.

The focus on a didactic approach emphasizing cancer screening promotion clearly met with resistance from community members at the dinners. In addition, the navigators’ “received view” that underprivileged community members just needed someone to guide them toward screening was challenged in a variety of other ways. Navigators such as Denise noticed that community members resisted scheduling screening appointments, even when community members were interested in the information/education she provided. Richie, a community navigator, reiterated that following through on the goal of providing a “bridge to access” was crucial to developing trust and rapport with community members because “it shows we’re authentic,” so he was very disappointed when a majority of the contact numbers provided to navigators were not in operation. Richie, a community navigator, found that:

I felt that people opened up to me easily; I filled out about ten intake forms with patients’ names, family history and phone numbers to follow up for screening appointments. We were hoping to follow up with the individuals by phone and help them schedule an appointment. For me, the follow up is crucial; it shows that we’re authentic and interested. I was surprised to find out later that most of the numbers were not functional. They put down fake numbers.

Among the individuals who were contacted for follow-up, there were also cases of no-shows, or situations where the communication between navigator and patient dropped off. Some navigators felt the fake numbers and no-shows were a sign of disinterest in screenings. Others speculated that this disinterest may be due to wanting to “save face,” the social desirability of getting screening (not wanting to seem like they “didn’t care” about their cancer), and being polite.

When confronted with these challenges, many navigators initially focused on improving information and providing technical solutions. For example, the student navigators recommended printing roadmaps or “critical path” advice that would help navigators know what to recommend in different situations. Nurse navigators recommended to researchers that navigators wear special shirts so everyone would know who they were. To increase screening compliance and follow-up, students on the research team recommended creating:

…a very simple takeaway card for navigators to give community members that includes the names and addresses of local screening centers; some quick facts related to cancer screenings; and the phone number to contact CJN. The purpose of this card would be to help community members overcome a lack of a way to easily get in touch with CJN to ask questions. This card should be brief, easy to read, and easily fit in a pocket or wallet; it should not be a pamphlet or include paragraphs of information. It should be designed to inform, not persuade.

These suggestions focused on technical fixes that would improve compliance with navigator messages about cancer screening, focusing primarily on communication as a one-way process. Slowly, however, some navigators began to emphasize changes in the interactions. For example, the nursing students recommended that the dinners should just be about introductions and relationship building, and the navigation itself should happen in a different meeting.

Navigation As Invitation to Dialog

Many of the navigators who had the opportunity to interact with community members over time began to re-think the navigation process. Patient navigators at CJN recognized the need to move away from a monolog-based understanding of navigation and to emphasize empathic listening.

Some changes were relatively simple ways to maintain openness. For example, rather than open the interactions at dinner by asking community members if they desire a cancer screening, one navigator broadened his introduction: “Hello, my name is James, and I am a patient navigator with the CJN. Does anyone have any questions about cancer or cancer prevention? Is there anything I can help you with as a community navigator?” This slight change emphasized eliciting responses and answering community members’ questions rather than cancer screening.

Instead of simply stating that a navigator could not give medical advice in a way that shut down conversation, some navigators gave a response like “I cannot answer medical questions or give medical advice, but I can help find someone who can. Would you like me to do that for you?” Another approach navigators developed was to open the conversation by seeking out personal and familial histories with cancer:

“How many of you have or know someone who has cancer? My name is Richie and I am a patient navigator with the Cancer Justice Network, and I would like to talk to you about preventing cancer in our community.”

In this version, the navigator emphasizes their role as listeners, in leading with the question about family history. While the differences in this approach versus the didactic may seem insignificant or superficial, navigators emphasized that this was a specific, strategic choice targeted toward improving rapport and engagement. As Camille explained to a research team member:

…[The biggest learning has been] that I need to meet them where they’re at. You cannot talk about colon cancer screening or mammograms from the get-go. It’s trust, and that takes time. People don’t know about screening, but everybody has a story about cancer. I spoke to a woman today who told me that everybody in her family—both her father and mother’s side—have had cancer, or died from it.

The research team noticed that over time, several navigators started sharing their personal journeys with cancer, and caring for others with cancer. Consider these snippets from our corpus of participant observation notes:

[We observed that] Rachel disclosed a personal story about her cancer journey during the navigation conversation. The cancer story involved being a caretaker for her mother as she went through treatment for her stage 4 cancer. Rachel spoke about being unaware about the effects of chemotherapy, and talked about how watching her mother go through the physical symptoms was very hard for her. At the end of the story, Rachel actively goes around the table to ask if others have had a personal experience with cancer or caretaking. Four people (out of six) responded with some sort of affirmation, with two sharing detailed family stories.

Today, Denise talked about being in cancer remission, explaining that she did not have cancer anymore. She began with “I am sure all of us have a story about cancer; today I am going to share mine.” Also spoke about how going through the experience has made her motivated to help and inform others. Sharing personal story has had a clear impact: people at the table are listening with active interest, and responding when she asks them to share their personal stories.

In these instances, navigators shared their personal cancer stories, allowing themselves to be vulnerable in the presence of patients, and thereby offering an invitation for patients to open up and be vulnerable in return. In this sense, patient navigation involves an invitation to dialog, and decenters the expert–novice dynamic within the navigation encounter. When asked about her decision to disclose her personal experiences, Denise stated:

You don’t really think about cancer until it becomes a part of your life—at least I never did. I decided to talk about my cancer experience because it opened a window into what life is like with cancer. If I talked about my chemo sessions, or the lifesaving difference of early detection for me, then I find that people will be okay asking me questions, or confiding in me about their cancer worries. That’s the first step.

Denise’s approach represents an orientation that looks at navigation as an opportunity to talk about cancer in a non-threatening, non-invasive manner. Notice that Denise does index the importance of detection and screening, but this is not a didactic strategy of “handing down” information, but rather, an engaged account of her experiences. We noticed this change in orientation—from didactic to dialogic—across several facets of navigation conversations. This dialogic mode was employed even in scenarios where community members put technical/medical questions to navigators.

Patient Navigation As a Structural Intervention

In an early review of the patient navigation literature, Dohan and Schrag (2005) distinguish between “service-focused” and “barrier-focused” navigation models, suggesting that eliminating barriers to care is always an important consideration. This spirit was evident among the leadership of CJN as well. For instance, a board member interviewed by the research team discussed his vision for developing specialized navigation teams. “This would look like assembling a team of three to four navigators each with a specialized area. One navigator may specialize in funding for treatment, another in the transportation process, while another may be more versed in explaining what the medical diagnosis and screenings mean.” This board member also emphasized the need to promote transportation as a primary mechanism to improve follow-up and access. Accordingly, CJN has since partnered with and obtained funding from several “mobility management” agencies committed to eliminating transportation barriers to care.

However, this transition was also apparent among how navigators understood their role, as they recognized that awareness about available healthcare was not the biggest barrier in the community. With time, navigators developed an appreciation for the idea that a complex set of circumstances, or structural determinants were responsible for community members’ resistance to screening services. It became evident that the barriers to effective oncological healthcare were not just lack of awareness about transportation, but barriers that were structurally determined.

For some navigators, consciousness of structural issues emerged as they began to consider the perspective of community members. A journal entry from a volunteer navigator makes this clear:

We were asked to reflect on why community members put fake numbers on their [intake] forms. In honesty, I must confess that I was frustrated when I found out, because it took a lot on my part to go out of my comfort zone and talk about cancer, the numbers and statistics and the services available. I guess putting myself in those shoes, I wouldn’t always want to give my number to someone who I just met. I know that a lot of people at the meeting were less financially fortunate, so perhaps phones without enough credit is a factor. We can’t just assume they wanted to blow us off.

Over time, the community navigators noted that the low-income and sometimes homeless population that the CJN was looking to serve often did not have phone numbers or email addresses, a fact that they may not have wanted to make public. Maria, a community navigator, observed that:

The first task was gaining trust among my table—to convince them that I am not here to sell something, but to inform them. On my first few interactions, I had several people tell me that they either had a doctor already, or that they knew about the free services available. At the time, I felt they were just trying to end the conversation, I’m not sure.

However, in expressing her frustration at the inability to “get through” to her audience, Maria spoke about an insight that she had while in the middle of a conversation with a community member:

I realized that no amount of information I could give this person would pique their interest about cancer. It was not on their radar at that point. And so, I decided it was important to be a person before a navigator. When I asked the gentleman about his current situation, he confided to me that his major concern at that point was that his housing situation was precarious. It struck me then that cancer may not be even a dot on his radar. I walked him over to introduce him to the folks at the homeless shelter table, and explained his situation.

In this particular case, a pressing life situation (uncertain housing) meant this individual was not in a position to focus on the cancer education/resources being presented to him. In attempting to address his immediate concern, Maria expands on the role of a navigator, or “being a person before a navigator.” Navigation, here, becomes the act of listening with empathy, an attempt to meet potential patients where they are, instead of assuming them to be empty slates to be filled with cancer knowledge. Our participation observation of navigator–community member interactions demonstrates an active transition from “screening” to “listening” as an opening for navigation.

This insight offered to the research team by a navigator validates the culture-centered principle of dialogic listening to localized articulations of health—in this case, the seeming inevitability and pervasiveness of cancer. For navigators at CJN, listening to community voices and experiences with cancer became an organizing principle for shaping the scope and purview of navigation. As Maria, who guided community members toward resources for addressing housing issues, said:

I met them again today… they’ve found a temporary place. Today, they asked me questions about the screening, the cost, and so on, and we were able to schedule a screening for the gentleman. They’re in a different space now. I listened to them earlier, now they are willing to talk to me. To trust me.

Here, Maria addressed how the act of listening with empathy toward clients’ articulations, regardless of whether they were about cancer—helped her play a small part in recognizing the broader structural barriers that may impede screening and prevention behaviors. In our reading, this is a powerful localized re-visioning of how patient navigation was understood.

Discussion

The research questions guiding this study sought to explore how community-based patient navigators re-inscribed the role of scope of patient navigation based on their interactions with community members. The three themes developed in our analysis document how lay navigators moved from equating navigation to screening promotion, to incorporating more dialogical, listening-based, and structural barrier-focused based on lived experience of “what works” and their interactions with community members. In this section, we highlight the scholarly and practical contributions of our study to the body of knowledge around patient navigation and the CCA.

Contributions to Theorizing and Practice of Patient Navigation Programs

Patient navigation, based on Freeman’s influential work in Harlem (Freeman, 2006a,b) was conceived as a model that attempted to offset some of the deep-set social, racial, and economic disparities in access to oncological healthcare in the United States. To our knowledge, our study is novel in that it explicitly casts patient navigation within the realm of communication theorizing, even as there is an implicit acknowledgment of the salience of communication as a central organizing principle in patient navigation in Freeman’s work. In our culture-centered vision for patient navigation, navigators and clients co-construct the agenda, scope, and delivery of a navigation intervention. This is an important move, in our view, in that it attempts to situate some of the decision-making and power in the hands of community members, and away from program planners, civil society elites or academic experts. This inversion of power, based on dialogic co-construction with marginalized communities is central to the philosophy of the CCA, and represents the most significant contribution of this study. While there is some acknowledgment that “what patient navigators do” (Fischer et al., 2007; Parker et al., 2010) is context dependent and subject to variation, the notion that navigators themselves shape the nature of the intervention is novel.

Our first research question explored the local meanings of navigation. In response, consider the evolution in CJN navigators’ conceptualization of their role, as documented in our themes. The move from screening-focused to listening-focused and, finally, structural barrier-focused approaches to navigation emerged organically. This is evidence that local cultural expertise is a valuable asset in shaping the agendas of community-based health interventions (Dutta, 2008). In a sense then, the CJN’s vision decouples the control of patient navigation interventions from biomedical institutions, and locates it within the agency of marginalized communities that are often only the recipients of such interventions. Theoretically, this is important as the radicalism of Freeman’s vision for patient navigation is increasingly appropriated toward interventions that seek to “culturally tailor” messages deemed to be salient for communities with little or no concern over what communities believe is salient to themselves (Jandorf et al., 2013). Our study is an attempt to move away from cultural tailoring of elite-driven intervention messages to the cultural negotiation of the shape and substance of community-based interventions.

Practically, and in response to our second research question, this study demonstrates the value of dialogic co-construction in the conceptualization and delivery of health interventions at the level of communities’ everyday lived experiences. Despite their sensitivity to the dynamics of power and marginalization that accompany academic–community interactions, CJN leaders, navigators, and some members of the research team alike initially focused on relatively technical fixes such as decision flowcharts to improve community member compliance with screening promotion. This tendency demonstrates the tenacity of conduit approaches to communication. Critical consciousness of the need for dialogic communication and attention to the structural contexts of healthcare decision-making occurred over time through interactions with community members. Providing organizational space for navigators to reflect on their interactions helped de-center our elite assumptions about “what works” with the community. Despite its relatively top-down start, the CJN was flexible and open enough to allow navigators’ emergent understandings to alter the organization’s approach to navigation. This stance facilitated a greater level of voice for community participants and greater attention to their lived needs, even as that somewhat significantly altered the organization’s mission and methods.

Contributions to Theorizing around the CCA

A secondary contribution of this paper is that it offers guidelines for extending the scope of culture-centered health communication. As is evident from this study, there exist several complementary features between the philosophy of patient navigation and the culture-centered principles of listening, co-construction and grassroots organizing with marginalized communities (Dutta, 2014). Conceptualizing patient navigation in terms of identifying local cultural expertise, structural barriers to health and community agency taps into the notion of health communication as activism (Zoller, 2005), while offering a heuristic theoretical model to be employed in health interventions.

Furthermore, this study extends the theorizing on dialog within the CCA (Dutta and Basu, 2008; Dutta and Pal, 2010), by focusing on how dialog with marginalized communities can be the entry point to developing bottom-up health solutions. This emphasis on dialogic co-construction differentiates our study from existent patient navigation interventions. While several existing patient navigation interventions claim to be “community-based,” the CCA offers a transparent rubric by which to evaluate the actual role and agency of marginalized communities in shaping patient navigation interventions addressing them. By introducing the idea of a culture-centered patient navigation model, our study offers a theoretical and practical approach to community-based research to practitioners and designers of patient navigation interventions.

Limitations

While the usual disclaimers about limited generalizability of qualitative data certainly apply to our study, there were other limitations as well. The data analyzed here were collected in the early stages of the academic–community collaboration, and provide little information about the later stages of the navigation relationship, as navigators coordinated with clients to provide transportation for medical appointments and attended screening appointments with them. Given that this is an ongoing project, we were unable to report on that data for this paper. Similarly, the perspectives and experiences of clients were not represented in this paper. We hope to document this important facet in a future study as we collect additional data.

Conclusion

In this paper, we analyzed initial data from an ongoing academic–community collaboration to document how the lived experiences and local cultural expertise of community-based patient navigators can inform the conceptualization and delivery of oncological patient navigation in a marginalized community. While navigators initially equated navigation with screening promotion, they incorporated listening-based orientations and acknowledged how patient navigation ought to address structural barriers to accessing preventive oncological services.

Ethics Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Review Board at the University of Cincinnati and the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center. This study was granted “exempt” status on the grounds that the investigator(s) were not involved in the recruitment of participants, and no identifying data were recorded in the study procedures.

Author Contributions

This is a multi-authored article. SS (Author 1) conceptualized the study and co-wrote the manuscript with HZ. HZ co-wrote the manuscript and analyzed the interview data. TW conducted the participant observation part of the study and reviewed literature. SS (Author 4) provided access to community organization and to participants.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ^In its participatory nature, concern with processes of marginalization, its emphasis on and listening to communities’ agentic struggles toward health, CCA shares many common features with CBPR (Wallerstein and Duran, 2006; Peterson, 2010). While CBPR has emerged as an interdisciplinary paradigm in health research, cited and used across numerous fields of study, CCA takes an inherently communicative stance to culture and health, and has emerged as a fast-growing critical approach to doing and evaluating health communication. The complementarities and differences between the two frameworks cannot be developed here for reasons of space (Dutta, 2007).

- ^All names have been changed to respect participant confidentiality.

References

Airhihenbuwa, C. O., and Obregon, R. (2000). A critical assessment of theories/models used in health communication for HIV/AIDS. J. Health Commun. 5, 5–15. doi: 10.1080/10810730050019528

Basu, A., and Dutta, M. J. (2007). Centralizing context and culture in the co-construction of health: localizing and vocalizing health meanings in rural India. Health Commun. 21, 187–196. doi:10.1080/10410230701305182

Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E., and Ananeh-Firempong, O. (2003). Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 118, 293–302. doi:10.1093/phr/118.4.293

Braun, K. L., Allison, A., and Tsark, J. U. (2008). Using community-based research methods to design cancer patient navigation training. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2, 329–340. doi:10.1353/cpr.0.0037

Bull, F. C., Kreuter, M. W., and Scharff, D. P. (1999). Effects of tailored, personalized and general health messages on physical activity. Patient Educ. Couns. 36, 181–192. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(98)00134-7

Calhoun, E. A., Whitley, E. M., Esparza, A., Ness, E., Greene, A., Garcia, R., et al. (2010). A national patient navigator training program. Health Promot. Pract. 11, 205–215. doi:10.1177/1524839908323521

Cancer Justice Network (2017) Available at: http://www.cancerjusticenetwork.org

Cresswell, J. W. (2003). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Dohan, D., and Schrag, D. (2005). Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer 104, 848–855. doi:10.1002/cncr.21214

Dutta, M. J. (2007). Communicating about culture and health: theorizing culture-centered and cultural-sensitivity approaches. Commun. Theory 17, 304–328. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00297.x

Dutta, M. J. (2014). A culture-centered approach to listening: voices of social change. Int. J. Listen. 28, 67–81. doi:10.1080/10904018.2014.876266

Dutta, M. J., and Basu, A. (2008). Meanings of health: interrogating structure and culture. Health Commun. 23, 560–572. doi:10.1080/10410230802465266

Dutta, M. J., and Pal, M. (2010). Dialog theory in marginalized settings: a subaltern studies approach. Commun. Theory 20, 363–386. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01367.x

Fischer, S. M., Sauaia, A., and Kutner, J. S. (2007). Patient navigation: a culturally competent strategy to address disparities in palliative care. J. Palliat. Med. 10, 1023–1028. doi:10.1089/jpm.2007.0070

Freeman, H. P. (2006a). Patient navigation: a community based strategy to reduce cancer disparities. J. Urban Health 83, 139–141. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9030-0

Freeman, H. P. (2006b). Patient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J. Cancer Educ. 21, S11–S14. doi:10.1207/s15430154jce2101s_4

Freeman, H. P., and Rodriguez, R. L. (2011). History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 117, 3539–3542. doi:10.1002/cncr.26262

Jandorf, L., Braschi, C., Ernstoff, E., Wong, C. R., Thelemaque, L., Winkel, G., et al. (2013). Culturally targeted patient navigation for increasing African Americans’ adherence to screening colonoscopy: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22, 1577–1587. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1275

Kreuter, M. W., and McClure, S. M. (2004). The role of culture in health communication. Annu. Rev. Public Health 25, 439–455. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000

Kreuter, M. W., Sugg-Skinner, C., Holt, C. L., Clark, E. M., Haire-Joshu, D., Fu, Q., et al. (2005). Cultural tailoring for mammography and fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African-American women in urban public health centers. Prev. Med. 41, 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.10.013

Ma, G. X., Shive, S., Tan, Y., Gao, W., Rhee, J., Park, M., et al. (2009). Community-based colorectal cancer intervention in underserved Korean Americans. Cancer Epidemiol. 33, 381–386. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2009.10.001

National Cancer Institute. (2017). State Cancer Profiles. Ohio. Available at: https://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/dataUseRestrictions.html

Parker, V. A., Clark, J. A., Leyson, J., Calhoun, E., Carroll, J. K., Freund, K. M., et al. (2010). Patient navigation: development of a protocol for describing what navigators do. Health Serv. Res. 45, 514–531. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01079.x

Paskett, E. D., Harrop, J. P., and Wells, K. J. (2011). Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J. Clin. 61, 237–249. doi:10.3322/caac.20111

Paskett, E. D., Katz, M. L., Post, D. M., Pennell, M. L., Young, G. S., Seiber, E. E., et al. (2012). The Ohio patient navigation research program: does the American Cancer Society patient navigation model improve time to resolution in patients with abnormal screening tests? Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 21, 1620–1628. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0523

Pedersen, A. E., and Hack, T. F. (2011). The British Columbia patient navigation model: a critical analysis. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 38, 200–206. doi:10.1188/11.ONF.200-206

Percac-Lima, S., Ashburner, J. M., Bond, B., Oo, S. A., and Atlas, S. J. (2013). Decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women using culturally tailored patient navigation. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 28, 1463–1468. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2491-4

Peterson, J. C. (2010). CBPR in Indian country: tensions and implications for health communication. Health Commun. 25, 50–60. doi:10.1080/10410230903473524

Peterson, J. C., and Gubrium, A. (2011). Old wine in new bottles? The positioning of participation in 17 NIH-funded CBPR projects. Health Commun. 26, 724–734. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.566828

Resnicow, K., Baranowski, T., Ahluwalia, J. S., and Braithwaite, R. L. (1999). Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn. Dis. 9, 10–21.

Saha, S., Beach, M. C., and Cooper, L. A. (2008). Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 100, 1275–1285. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31505-4

Tracy, S. J. (2012). Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Wallerstein, N. B., and Duran, B. (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot. Pract. 7, 312–323. doi:10.1177/1524839906289376

Wells, K. J., Battaglia, T. A., Dudley, D. J., Garcia, R., Greene, A., Calhoun, E., et al. (2008). Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer 113, 1999–2010. doi:10.1002/cncr.23815

Zoller, H. M. (2005). Health activism: communication theory and action for social change. Commun. Theory 15, 341–364. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00339.x

Keywords: patient navigation, culture-centered approach, community-based interventions, cancer disparities, racial disparities, low-income populations

Citation: Sastry S, Zoller HM, Walker T and Sunderland S (2017) From Patient Navigation to Cancer Justice: Toward a Culture-Centered, Community-Owned Intervention Addressing Disparities in Cancer Prevention. Front. Commun. 2:19. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2017.00019

Received: 09 September 2017; Accepted: 17 November 2017;

Published: 04 December 2017

Edited by:

Jeffery Chaichana Peterson, Washington State University, United StatesReviewed by:

James Olumide Olufowote, University of Oklahoma, United StatesNadine Yehya, American University of Beirut, Lebanon

Copyright: © 2017 Sastry, Zoller, Walker and Sunderland. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shaunak Sastry, c2FzdHJ5c2tAdWNtYWlsLnVjLmVkdQ==

Shaunak Sastry

Shaunak Sastry Heather M. Zoller

Heather M. Zoller Taylor Walker2

Taylor Walker2