95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Clim. , 08 December 2022

Sec. Climate Mobility

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.990558

Disaster displacement is an increasing challenge in the context of climate change. However, there is a lack of research focusing on Europe as a destination area, including on the question how the normative protection gap with regard to cross-border disaster displacement is addressed from a European perspective. Against this background this article provides evidence from a European case study focusing on the role of disaster, such as droughts or floods, in asylum procedures in Austria. Based on a qualitative content analysis of 646 asylum decisions rendered by the Austrian appellate court (supplemented by qualitative interviews with relevant Austrian stakeholders), it is demonstrated that disasters are—to a certain extent—already taken into consideration in Austrian asylum procedures: impacts of disasters are not only brought forward by applicants for either leaving the country of origin or for not wanting or not being able to return. They are also increasingly discussed in the legal reasoning of judgments of the Austrian appellate court. The analysis shows that impacts of disasters play an important role mainly in decisions concerning persons from Somalia, and here primarily in the assessment of the non-refoulement principle under Article 3 ECHR and subsidiary protection. This can be regarded as a response to the protection gap—even though not necessarily applied consistently.

Disaster displacement1 is gaining in importance against the backdrop of a further increase in the quantity and intensity of environmental climate hazards (IPCC, 2022, p. 13). Research suggests that “[m]ost climate-related displacement and migration occur within national boundaries, with international movements occurring primarily between countries with contiguous borders” (IPCC, 2022, p. 52). Available data show that the largest number of people annually displaced by extreme weather events are recorded in East and South Asia and the Pacific, followed by sub-Saharan Africa2. However, research has pointed out that there is an “uneven geography of research on ‘environmental migration'” (Piguet et al., 2018). While most research on “climate migration” focuses on Asia and Oceania, Europe and South America receive only little attention (Ghosh and Orchiston, 2022). Although meanwhile a few studies on climate mobility to Europe are available (Afifi, 2011; Geddes, 2015; Missirian and Schlenker, 2017; Cottier and Salehyan, 2021), the relevance of climate mobility dynamics for Europe is still not well understood and data in this context is insufficient and conflicting. In 2017, a study showed that increases in temperature in countries of origin corresponded to increasing asylum applications in Europe (Missirian and Schlenker, 2017). Yet, another study found no evidence that a drought in the sending country increases “unauthorized migration to the EU” (Cottier and Salehyan, 2021). There is a common understanding that migration will predominantly occur within the countries of origin and that the consequences for mobility toward Europe are highly unsecure (see also IPCC, 2022, p. 1867).

At the political level, the issue of climate mobility toward Europe is either addressed only very defensively or is absent altogether. Already in 2013, the European Commission wrote in a Commission Staff Working Document on climate change, environmental degradation, and migration that “the impact of climate change and environmental degradation on migration flows to the EU is unlikely to be substantial” (Commission Staff Working Document, 2013, p. 11)3. Also on a global policy level, for example in the context of the Nansen Initiative/Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) or of the UNFCCC Taskforce on Displacement (TFD)4, there is a lack of engagement with the topic of climate mobility toward or within Europe. In relation to the Nansen Initiative, Scott points out, that “[w]ith regional consultations focusing predominantly on “South-South” mobility, the legal situation of people who are displaced in the global North in the context of disasters and climate change remains under-explored” (Scott, 2016, p. 29).

Thus, there is a lack of - in particular qualitative - research on the topic of climate mobility towards and within Europe and the studies available are conflicting in their results. There is no political focus on European countries as a destination area—neither on the European nor on the international level. However, there is ample evidence that disasters are brought forward in asylum procedures in the Global North (see, for example, Fornalé, 2020; Schloss, 2021; Ammer et al., 2022a; Scott and Garner, 2022) and—at the same time—little research on how authorities in European countries deal with such claims. Against this background this article provides evidence from a European case study focusing on the role of disaster in asylum procedures in Austria. Austria is a suitable example for such a case study as, compared to other EU countries, it receives a high number of asylum seekers every year5, ranking second with regard to asylum applications per 100,000 inhabitants (Bundesministerium Inneres, 2022, p. III). Furthermore, Austria receives a high number of asylum seekers from countries affected by disaster impacts (for example, asylum seekers from Syria, Afghanistan, Morocco, Somalia, Pakistan, Iraq, Bangladesh, India).

In addition, this article responds to the so-called normative protection gap with regard to cross-border disaster displacement (Kälin and Schrepfer, 2012; McAdam, 2012, p. 5, McAdam, 2016, p. 1523, McAdam, 2021) from a European perspective. None of the international legally binding instruments in the areas of migration, refugee protection or environment/climate change deals adequately with the legal status of persons displaced across international borders in the wake of a disaster. International law does not regulate, for instance, entry, access to basic services during stay, or conditions for return (Nansen Initiative, 2015, p. 28). Movements in the context of slow-onset environmental degradation pose a particular challenge in this context (Human Rights Council, 2018)6. While some scholars have proposed new legal and/or institutional frameworks to address the gap (e.g., Williams, 2008; Hodgkinson et al., 2009; Warren, 2016; Biermann, 2018; Prieur, 2018; Schloss, 2018), others have argued that there “is not a complete void” (McAdam, 2021, p. 847) and that the scope of existing norms needed to be clarified. In this context, international human rights law, and here the non-refoulement principle derived from the right to life or the prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment, which has a broader personal scope of application than under international refugee law (McAdam, 2012, p. 103ff), is regarded to have the greatest potential to offer protection (McAdam, 2016, p. 1537; Human Rights Council, 2018, p. 67; Goodwin-Gill and McAdam, 2021, p. 645)7. Still, “substantial progressive development of the principle of non-refoulement under human rights law would be required before this could be considered an effective remedy” (Goodwin-Gill and McAdam, 2021, p. 648). The development of jurisprudence is on its way—the Teitiota case of the UN Human Rights Committee constituting a prominent example8. On a European level, however, so far the ECtHR has not ruled on an expulsion case in which the impacts of a disaster were the main reason not to return a person under the ECHR. On a policy level, the Nansen Initiative Protection Agenda (Nansen Initiative, 2015), endorsed by 109 delegations including those of the European Union and Austria, offers a toolbox of effective practices, including to protect persons displaced across borders in the context of disasters. It asks states to address this gap by using different tools, from the granting of visas; prioritizing the processing of regular migration categories; granting humanitarian visas to the granting of international protection.

Academic literature has so far contributed little to the question how to address the protection gap from a European perspective (see above). This article addresses this research gap by analyzing whether and how disasters such as droughts or floods,—some of them can be attributed climate change (Marjanac and Patton, 2018; Funk et al., 2019; Burger et al., 2020; Sippel et al., 2020)9—are already considered in the Austrian asylum procedure. Based on a mainly qualitative analysis of case law on international and humanitarian forms of protection decided by the Austrian appellate court [Federal Administrative Court (BVwG) and its predecessor, the former Asylum Court (AsylGH, 2008–2013)], we show that disasters are already considered in asylum procedures in Austria. The analysis was supplemented with qualitative interviews with relevant Austrian stakeholders. Our results demonstrate that disasters are not only brought forward by claimants but are also increasingly mentioned in the findings and, importantly, in the legal reasoning—first and foremost in the context of the assessment of the non-refoulement-principle under Article 3 ECHR and therefore of subsidiary protection status.

In the following, we will introduce the methodology applied in the study and give an overview of the case law (Section Methodology and overview of case law). In Section Analysis of disasters in decisions on international protection in Austria, we will firstly [Section Disasters brought forward by claimants and/or their legal representatives (C/LR)] present which disasters are brought forward by the claimants and/or their legal representatives as reasons to leave the country of origin or for not wanting or not being able to return and how they are brought forward. Subsequently in Section Disaster in country of origin information, we will shortly elaborate on whether and how disasters are included in so-called country of origin information (COI) which is used in asylum procedures to assess the situation in the country of origin of the claimant. In Section Outcome: Disaster in legal reasoning we will discuss what role disasters play concerning the outcome of the procedures. We will analyze whether and how they are considered in the legal assessment of refugee status, followed by an analysis how disasters are taken into account with regard to the granting of a subsidiary protection status. We will conclude in Section Discussion and conclusion with a discussion of the results.

For this research a mixture of research methods was applied: the main methodological approach chosen for the research was a qualitative content analysis of Austrian decisions of the appellate court in the asylum procedure, i.e., the Federal Administrative Court (BVwG) and its predecessor, the Asylum Court. Decisions assessed concerned the granting of international and humanitarian forms of protection. In addition, some quantitative data on the case law was also collected during the sampling process and the phase of qualitative analysis. Furthermore, the case law analysis was supplemented by semi-structured interviews with relevant Austrian stakeholders. Both, the case law as well as the interview partners were sampled purposefully, on the basis of being particularly relevant and informative concerning the research question (Flick, 2014, p. 170–174; Rapley, 2014, p. 54; Patton, 2015). As the primary objective of the research was to analyze the role of disasters in Austrian case law on international and humanitarian forms of protection and how these factors are addressed, we wanted to select the most “information-rich cases for in-depth study” (Patton, 2015, p. 401) from which we could learn most about the purpose of the study. In the following, we will present the most important methodological steps in the research process.

As a first step, keywords such as drought, flood, disaster, cyclone, hurricane, sea level-rise, which are mainly related to hazards and disasters that are projected to further increase in the context of climate change (with the exception of “earthquake” which was also used as a keyword), were selected and used for a first search in the database “Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes” (RIS) together with the relevant Austrian legal norms “AsylG 2005 §3” and “AsylG 2005 §8”. The RIS is a legal database of the Republic of Austria providing Austrian law and case law, which contains also decisions on international and humanitarian protection of the Austrian appellate court, the former AsylGH (2008–2013) and the BVwG (since 2014). The database is publicly accessible (https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Judikatur/). The search only captures decisions which were delivered in writing including the fully written versions of the orally pronounced verdicts. The database does neither contain decisions on international protection and humanitarian forms of protection issued by first-instance authorities nor decisions by appellate courts which are pronounced orally and where only a short, written version of the verdict is uploaded to the database.

Concerning the selection of keywords used for the search, the following considerations were important: decisions on international and humanitarian forms of protection deal with forced displacement across international borders. They discuss reasons why a person left and why he or she cannot go back to his or her country of origin. As climate change already leads and will lead to an increase in the quantity and intensity of disasters, we decided to choose keywords that directly indicate that such disasters are to be found in the decisions: the keywords are (the original German search words are in parentheses): “drought” (“Dürre”), “flood”, “flooding” (“Flut”, “Überflutung”, “Überschwemmung” and “Hochwasser”), “hurricane”, “typhoon” and “cyclone” (“Hurrikan”, “Wirbelsturm”, “Orkan”), “land slide” (“Erdrutsch”), “sea-level rise” (“Anstieg des Meeresspiegels”), “forest fire” and “wildfire” (“Waldbrand” and “Buschfeuer”). In addition, we searched for keywords directly relating to climate change, such as “climate change” and “global warming” (“Klimawandel” and “Erderwärmung”), as well as the keyword “disaster” (“Katastrophe,” “Desaster”) and a keyword we thought might indicate the impact of a disaster, that is “famine” or “hunger” (“Hunger”). We also decided to use the keywords “earthquake” (“Erdbeben”) as from a juridical point of view, the legal evaluation of the impact of an earthquake in asylum procedures might be similar to weather-related disasters.

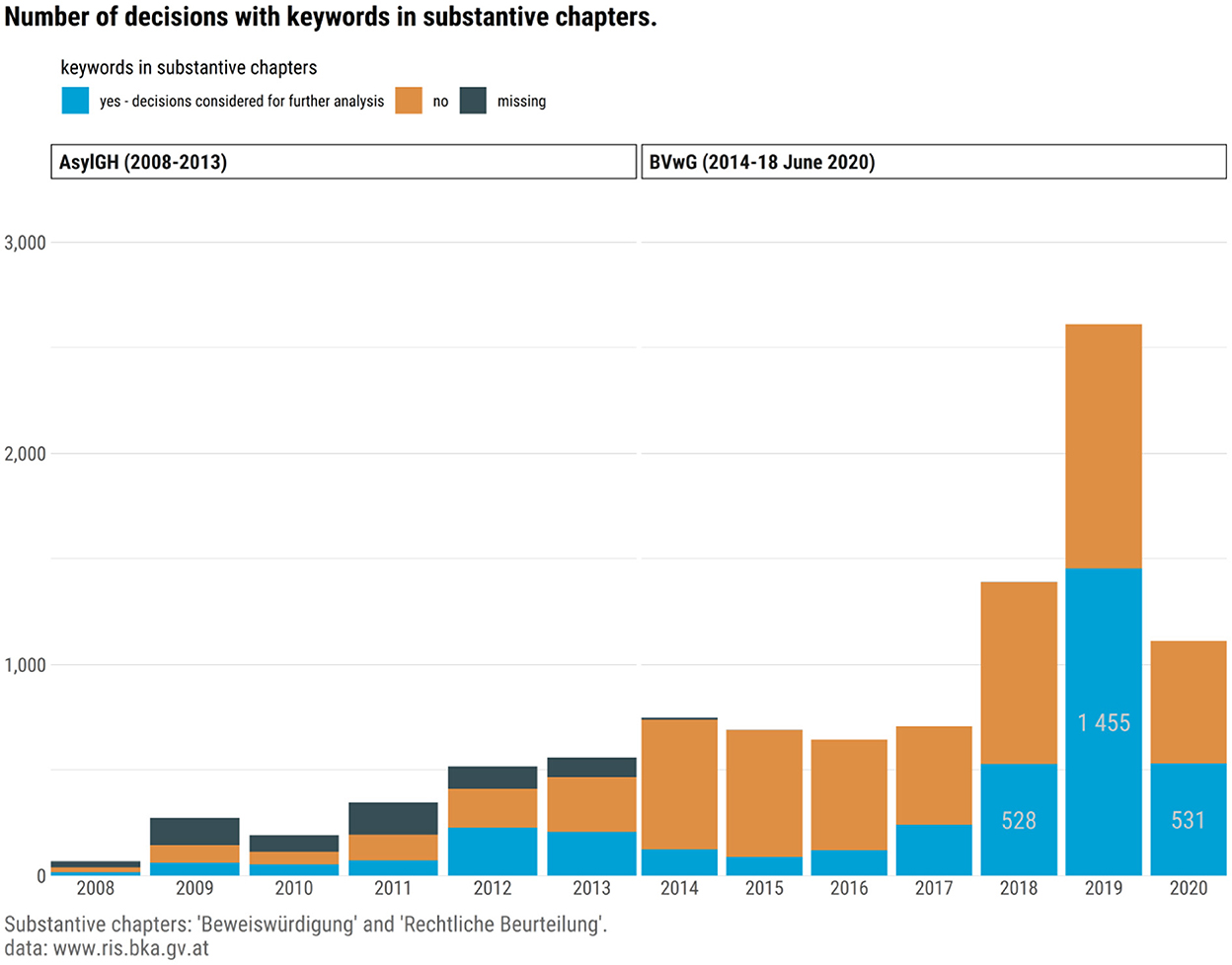

The search showed that 9,860 decisions on international and humanitarian forms of protection of the Austrian appellate court, the former AsylGH and the BVwG, between 1 January 2008 and 18 June 2020 contain one or more of the selected keywords. To put this number into perspective, the result of searching only for “AsylG 2005 §3” and “AsylG 2005 §8” in the respective time period is 39,832 decisions (AsylGH: 13,163, BVwG: 26,669)10. Only those decisions which contained at least one disaster-related keyword in chapters on evaluation of evidence or legal reasoning—the substantive parts of the judgment—were retrieved from the database. These two chapters give insight into which factors have an impact on the outcome of the decision and how different aspects are legally assessed and evaluated. The cases containing keywords in these two substantive chapters were extracted by using R programming language, resulting in 635 decisions of the AsylGH between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2013 and 3,087 decisions of the BVwG between 1 January 2014 and 18 June 2020 (in total 3,722 cases), which formed the basis of the further purposive sampling process.

Figure 1 shows the number of keywords per year until 18 June 2020. There is a considerable increase in decisions containing keywords in substantive chapters from the year 2017 to the year 2018 and from the year 2018 to 2019.

Figure 1. Keywords in substantive chapters per year until 18 June 202011.

In cases decided by the AsylGH, the keywords mentioned most frequently in substantive chapters were floods, disaster, famine, earthquake, drought and storm, and in cases decided by the BVwG the keywords used most often in substantive chapters were drought, followed by famine, disaster, earthquake, floods, climate change, storm and landslide (see Figure 2).

The distribution of keywords over the years indicates that there is an increase in the keywords drought and disaster. The distribution of keywords such as floods, famine, earthquakes and storms varies of the years (see Figure 3).

Droughts were most frequently mentioned in decisions concerning claimants from Afghanistan and Somalia, the keyword of disaster shows the most hits in decisions relating to claimants from Pakistan and Afghanistan, the keyword famine is found most often in decisions by claimants from Pakistan and Somalia, the keyword flood in decisions by claimants from Pakistan.

The sampling process contained further steps to narrow down the size of the sample used for qualitative analysis. Factors taken into consideration for selecting the sample were the following:

• Gender/Family: the distribution of cases according to gender and/or family status (decisions not only refer to individual persons but also to families) of the 3,722 cases was 74.5 percent male, 18.2 percent group/family, 4.2 percent female and 3.2 percent, where this information was missing after the search process. In the final sample, we tried to increase the cases with female claimants. As the significance of the disaster played an important role also in the selection of the sampling (see below), the gender/family distribution in the final sample is 86.1 percent adult male, 6.7 percent adult female, 4.8 percent parent(s) with minor child(ren), 0.6 percent minor male, 0.6 percent minor female, 0.5 percent couples, 0. 5 percent parent(s) with adult child(ren), 0.3 percent siblings.

• Distribution of keywords: some decisions had up to 37 hits of a specific keyword in the core part of the decision. We preferred decisions with many hits of keywords.

• Countries of origin: we reviewed decisions relating to all countries of origin which showed keywords in substantive parts of the decisions. However, we only selected decisions which were significant for the purpose of this study without aiming for a representative distribution of countries of origin.

• Year of decision: we took the temporal distribution of the decisions into account and selected, if available, at least some cases for each year. The distribution of the cases selected for analysis is depicted in Table 1.

• The significance of the disaster for the decision was a particular important sampling criterion, as the objective was, to select “information-rich cases for in-depth study” (Patton, 2015, p. 401).

In total, 646 decisions were selected for a more detailed analysis. The sample contains 346 decisions referring to claimants from Somalia, 200 decisions concerning claimants from Afghanistan, 81 decisions concerning claimants from Pakistan, five decisions from India and 14 from Nepal. The uneven distribution of countries of origin reflects the significance of the disaster in the judgment concerning the respective countries. This was also confirmed by the qualitative interviews where stakeholders of the Austrian legal system emphasized that disasters played a role mainly in decisions referring to asylum seekers from Somalia, to a lesser degree to asylum seekers from Afghanistan and only a minor role in decisions concerning claimants from other countries.

Semi-structured interviews with relevant stakeholders (n = 17) were carried out. The interviews aimed at supplementing and validating the results of the case law analysis. The interview partners were selected purposefully. Five interview partners were judges from BVwG, who decide on complaints against first-instance authority decisions in asylum cases and who could provide us with information what role disasters play in their work as judges. One judge was from the Austrian Supreme Administrative Court. In addition, interviews were carried out with six legal counselors from the Federal Agency for Reception and Support Services, which is an entity owned by the Republic of Austria and entrusted with the task of supporting and counseling asylum seekers in Austria. Further interviews were conducted with three private lawyers with a focus on asylum law, with one representative of the organization, which provides COI, and one expert from a non-governmental organization. The semi-structured interview guidelines contained questions on what role disasters play in the work of the interviewee and how they address them in the legal procedures.

The selected case law was uploaded into a Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) program (MAXQDA), coded according to a specific framework (which was developed during a pilot phase and refined for the main analysis), and qualitatively analyzed concerning their insights with regard to the research questions. Thus, a list of categories (codes) was developed, that allowed to “annotate and label the data,” which “involves applying labels to chunks of data judged by the research to be ‘about the same thing' so that similarly labeled data extracts can be further analyzed” (Ritchie et al., 2014, p. 282). An initial coding framework was developed based on the research questions and extended by additional codes derived by a sub-sample of 30 decisions taken from the whole sample of case law, which was analyzed in the pilot phase. MAXQDA was used as it allowed not only for coding case law and preparing the material for the qualitative analysis but also for collecting some quantitative data such as the outcome of the decision, the gender or family status, the type of procedure, bringing forward of the disaster by claimants and/or their legal representatives, in which part of the decision the disaster was mentioned or whether it was the only factor or one amongst other factors relevant for the decision.

The results of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and uploaded in MAXQDA, coded and analyzed. The coding framework for the interviews was developed on basis of the coding framework for the case law. The analysis included the comparative interpretation of codes of the analyzed decisions and interviews, understanding and carving out the internal logic of the excerpts and getting insights by comparing the excerpts with the same code in light of the research questions (Olsen, 2011, p. 56–64; Flick, 2014, p. 375).

Asylum seekers who are admitted to the Austrian asylum procedure must be questioned in detail about the reasons for fleeing their country. In 36.5 percent of the sample, disasters were brought forward by the C/RL as a factor for either leaving the country or for not wanting or not being able to return. There were differences between claimants of different countries of origin concerning the bringing forward of disasters. Concerning Somalia, in 40.2 percent of the cases (139 decisions) a disaster was brought forward by the C/LR. In the case of Afghanistan, 33 percent (66 decisions) out of the 200 analyzed decisions mentioned that the C/LR referred to a disaster. With regard to decisions from Pakistan, 22.2 percent of the 81 decisions analyzed (18 decisions) stated that the C/LR brought forward the disaster situation during the procedure. In ten (71.4%) out of 14 decisions relating to the country of origin Nepal, the C/LR mentioned the earthquake and in three (60%) out of five Indian cases, the C/LR referred to a disaster in the country of origin.

The disasters mentioned by C/RL were drought (65.41%), flood (17.29%), famine (11.65%), earthquakes (3.76%), “natural disasters” (0.75%), landslide (0.38%), hurricane/cyclone (0.38%) and locust plague (0.38%) (see Figure 4). For example, in a hearing before the BVwG a claimant stated:

“Judge: Are your family members affected by the effects of the reported drought? If so, what exactly did they tell you?

Claimant: When my family needs water, there is no running water. The food has become very expensive. We mostly ate corn and beans and because it hasn't rained for long now, there are shortages. You can't buy that much food now.

J: Do you know about the current situation in XXXX? It is currently the rainy season and it is raining a little. Do you have any up-to-date information?

C: I don't know. Yesterday I saw a message that it was raining in Mogadishu. I don't have any news about the current situation in XXXX.

J: You just mentioned Mogadishu. Is your aunt somehow indirectly affected by the drought or not?

C: I think so. Mogadishu cannot be compared to XXXX. There are more possibilities to survive in Mogadishu. For example, the food sold at a high price in XXXX comes from Mogadishu and the surrounding area.” (W125 2010495-2, 2017)12

Only in very rare cases, disasters were indicated as the only or the main reason for leaving the country of origin or for fearing return. This was, for example, the case concerning a claimant from Pakistan. The passage in the decision reads as follows:

“As a reason for leaving the country of origin, the complainant (…) essentially argued that he and his family had lost everything due to the floods. So far, they had been supported by relatives, but this was not permanent. In order to be able to support his family, he had made his way to Europe to work here. He hopes that he will get asylum in Austria and that the state will support him for a while.” (E11 422862-1/2011, 2012, I.1.1.1)

In most cases, disasters were brought forward in addition to other reasons such as the security situation, persecution for political or religious reasons or for belonging to a certain (minority) group. They were implied when recounting the living conditions in the home country. Disasters were reported to have an impact on the supply situation, agriculture, families and other social support systems (such as clans), gender, occupation and economic opportunities, housing, property and possessions, the conflict situation, and internal or external displacement:

The disaster situation was frequently reported to have adverse effects on agriculture. In particular, complainants who were directly dependent on farming brought forward this issue during the asylum procedures. They described the adverse consequences of disasters on their livestock as well as on other agricultural areas (e.g., A5 422794-1/2011, 2012; W211 2144925-1, 2017; W103 2148233-1, 2018; W103 2155449-1, 2018; W161 2179007-1, 2018; W161 2179265-1, 2018; W237 2176062-1, 2018; W261 2190990-1, 2018). In particular drought, but also in some cases floods, were claimed to have a serious impact on agriculture. Claimants recounted that “many animals died in the wake of the ongoing drought” (W211 2169981-1, 2017), that “there was an indescribable drought in the country and that the harvest had practically failed” (W211 2144925-1, 2017), that “due to the drought, the fields had dried up and the animals had perished” (W161 2179265-1, 2018) and that “there were no longer many opportunities to do agriculture” (W159 2157583-1, 2017). Concerning the devastating impact of floods on agriculture, a claimant from Somalia stated that the “rain brings flooding, causing great damage to agriculture and infrastructure” (W103 2155449-1, 2018) or a claimant from Pakistan who had taken out a loan in order to build fish ponds reported that due to considerable rainfalls he “lost many fish and was unable to repay the loan and interest” (E13 424190-1/2012, 2012).

Closely related to the impact on agriculture, the supply situation was claimed to be severely affected by the disaster, leading to under- and malnourishment of the population and famine. For example, referring to his country of origin Afghanistan, a claimant said that “there is a drought in Herat and Mazar-e Sharif, which has a negative impact on agriculture and thus on the supply situation in these cities” (W261 2190990-1, 2018). Another claimant from Afghanistan submitted a newspaper article indicating that “many children are malnourished” (W264 2167964-1, 2018) due to the drought. Concerning cases from Pakistan claimants reported that “due to the floods he also no longer has a livelihood” (E12 217603-2/2011, 2012) or that “the supply situation would also be precarious due to the flood disasters in the last few years” (E11 422324-2/2013, 2013). Claimants from Somalia repeatedly mentioned the supply situation as a problematic aspect due to recurring droughts “which would result in very high food prices” (W159 2161606-1, 2017) and lead to “food shortages” (W103 2159484-1, 2018) and “famine” (W196 2138677-1, 2017). In the case of Somalia, it was also reported that “above-average rainfall did not have a positive effect on the food situation due to flooding” (W159 2144647-1, 2018).

Disasters, in particular earthquakes and floods, also had a problematic impact on housing and property. Claimants reported that their “house was affected by the floods in Pakistan in 2014 and was destroyed” (L508 1434790-6, 2019) or—in the case of Nepal—that the “house had been destroyed by the earthquake and that they had lost everything there” (W220 2191761-1, 2019). A claimant from Afghanistan stated that “he had lost everything in a flood and therefore had to flee” (W201 2118203-1, 2019) and another complainant from India said that “his father's grocery shop had been destroyed due to a flood” (W220 2227288-1, 2020).

Claimants repeatedly described how the disaster situation was adversely affecting their families. They mentioned a lack of food and water supply for family members, failing economic opportunities, the loss of family property, housing, livestock and possessions, deteriorating health conditions or even deaths of family members and displacement due to drought, earthquakes and floods. For example, a Somalian claimant whose family lived from farming indicated that “his father committed suicide after the animals died as a consequence of the drought” (W159 2159490-1, 2018) or that the family farm cannot support the family any longer due to the fact that the harvest failed (W211 2144925-1, 2017). A claimant from Pakistan reported that “he and his family had lost everything due to the flood” (E11 422862-1/2011, 2012) and in order to be able to support the family came to Europe. Another claimant stated that “his entire family (parents, sister, wife, children) had died in the great earthquake in Kashmir” (C7 3150671/2008, 2008).

A recurring issue brought forward by claimants was the dynamics between violent conflict and disaster, the so-called “nexus dynamics,” which is defined by “situations where conflict and/or violence and disaster and/or adverse effects of climate change exist in a country of origin” (Weerasinghe, 2018, p. 19). Claimants frequently reported about the disaster situation in the context of, in addition to and/or in interrelation with conditions of violent conflicts. For example, claimants from Pakistan reported that “[t]he Taliban were particularly active in the flooded areas through aid organizations they had infiltrated” (Biermann, 2018) or claimants from Somalia reported that the drought situation was exacerbating the conflict situation (W159 2162252-1, 2018).

Claimants also repeatedly reported that disasters led to internal and/or cross-border displacement of family members or other people. For example, in the case of Afghanistan, a claimant “argued that the ACCORD report showed that many people affected by the drought had fled to Herat” (W242 2125884-1, 2018). In Somali cases, claimants, for example, stated that “the family moved to a camp near Mogadishu because of the drought” (W211 2144925-1, 2017), or that due to the drought the wife and children “are living in a refugee camp in Kenya” (W103 2148233-1, 2018) or that the family of a complainant consisting of a mother, three sisters, a brother and a grandmother “had left their home because of the drought and would live in a camp near XXX” (W161 2179265-1, 2018). Concerning Somalia, it was also reported that people repatriated from Kenya or Yemen would exacerbate the already precarious food supply situation (W159 2146501-1, 2017).

Frequently, C/LR argued that the dire situation due to the disaster in their country of origin would be a violation of their rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), in case the claimant would have to return or would be deported. In addition, there were cases, where the C/LR argued that the disaster was an obstacle for the claimant to seek a relocation alternative elsewhere in the country of origin (W159 2157583-1, 2017).

In one case, referring to the country of origin Somalia, the legal representative argued that his client would even qualify for refugee status “for reasons of belonging to a certain social group, namely to the group of poor people affected by the drought and its consequences” (W240 2187484-1, 2019) and in another case referring to the country of origin Pakistan, the applicant argued that he belonged to the social group of “socially weak persons who were not able to rebuild their livelihoods on their own after the total destruction of their livelihoods by the flood” (E11 422862-1/2011, 2012), which was threatened by persecution.

The authorities are obliged to investigate ex officio all relevant country of origin information (COI), including information on disasters, if this is necessary for assessing whether a claimant qualifies for international protection. Most analyzed decisions contained disaster- and environment-specific COI. The most detailed and extensive coverage of disasters in COI could be found in decisions concerning Somali claimants with reference to a broad variety of sources13. In almost all Somali decisions, the Court used comprehensive COI containing information on droughts, rainfalls and floods, a cyclone and locust plagues and their impact on agriculture and farming, the supply situation in general, national economy, health care, conflict and security situation, displacement, poverty, women, children, minorities and other issues. COI also discussed the long-term impact of the drought on the supply situation, the dependence of the population on food aid, and the slow recovery after the rain had come back. COI stated that there was a humanitarian crisis in Somalia and mentioned that droughts were occurring more often than in former times. COI also explicitly referred to the fact that Somalia was particularly affected by the impacts of climate change. The COI used in Somali decisions was regularly updated and, thus, reflected the development of the disaster situation over time. For example, the following extract of a text module was used in a case decided in November 2017, which contains, next to other (older) text modules on the development of the drought as well as the rain, the following updated information:

“With both rainy seasons (Deyr and Gu) having failed for over 2 years, a humanitarian disaster has unfolded in Somalia. The subsistence farming system in the Shabelle and Juba river basins has partially collapsed; staple food prices have doubled; and millions of head of livestock have died (ICG 9.5.2017). Somaliland authorities speak of 80% livestock losses (BBC 11.5.2017; cf. TG 24.5.2017), other estimates speak of 50%. Somaliland's Foreign Minister states: There have always been droughts here, but only every 10 years. Now we have them every 2 years. And the drought this year is the worst drought we have ever had in East Africa (TG 24.5.2017).

(…) The risk of famine persists. 6.2 million people are acutely affected by food shortages, 3 million need life-sustaining support (UNSC 9.5.2017). Since November 2016, over 740,000 people have left their homes due to the drought, including 480,000 under 18 years old (UNHCR 31.5.2017). Famine deaths have been reported in some regions—such as Bay (BBC 4.3.2017).

Some difficulties that were already prevalent in 2011 persist. Insecurity and lack of access to aid are problematic (ICG 9.5.2017). Especially in South/Central Somalia, the poor security situation sometimes prevents people from accessing humanitarian aid (UNSC 9.5.2017). South/Central Somalia is again the epicenter of the humanitarian crisis. This is exacerbated there by local clan conflicts and al Shabaab (ICG 9.5.2017).

In contrast, parts (‘pockets') of Somaliland and Puntland were also severely affected by the drought. However, the situation there is far less bad than in the south (ICG 9.5.2017).” (W159 2148065-1, 2017)

In several decisions concerning claimants from Afghanistan, COI stated that the country was regularly affected by recurring droughts, but also floods, extreme cold spells or earthquakes leading to challenges in the daily basic supply situation. In some decisions, COI pointed out the connection between climate change, natural hazards and poverty. In decisions relating to Pakistan, COI referred to different floods and their impacts. All 14 Nepali decisions analyzed contained COI on the major earthquake in 2015.

In decisions mainly concerning claimants from Somalia and Afghanistan, COI comprehensively elaborated on the interrelation between violent conflict and disaster. In the Somali cases the drought and its implicated food and water shortages were often mentioned in relation to the security situation (e.g., difficult access to humanitarian aid because of the security situation and Al Shabaab activities). Very comprehensive text modules were included about the impact of war, drought and flood disaster on the supply and medical situation in Somalia. COI indicated in particular that the drought disaster intensified resource conflicts, would likely contribute to the escalation of conflicts and that resource and food shortage due to the drought was a breeding ground for new recruits as the militant group Al Shabaab promised to provide for the (young) recruits and their families. COI also showed that drought and conflict both had an impact on displacement in Somalia (displacement because Al Shabaab obstructing humanitarian assistance), as is the case in the following text module taken from a decision of February 2018:

“The total number of IDPs in Somalia is estimated at 1.56 million as of November 2017. During Jan-Nov 2017, 874,000 people were displaced within Somalia due to drought; another 188,000 due to conflict or insecurity (UNHCR 30/11/2017b). Between November 2016 and April 2017 alone, more than 570,000 people left their homes due to the drought, becoming IDPs (UNSC 9.5.2017). Another source puts the number of people displaced by the drought between November 2016 and July 2017 at 859,000 (SEMG 8.11.2017). Of these, around 7,000 sought refuge in Ethiopia and Kenya (UNSC 5.9.2017). The Al Shabaab is partly responsible for people affected by the drought having to flee their homes, as the group obstructs humanitarian aid and runs blockades. In addition, around 87,000 people have been displaced in the wake of the conflict and insecurity in Lower Shabelle (SEMG 8.11.2017). Thereby, the reception capacity of the refuge areas is limited (ÖB 9.2016).” (W234 2145460-1, 2018)

COI also stated that IDPs were severely affected by the drought since they could not afford rising food prices. In addition, COI reported about the increase of gender-based violence in IDP camps due to the growing number of drought-related IDPs. COI frequently referred to the impact of the drought not only on IDPs but also on children and women or on minorities. Also in decisions referring to the country of origin Afghanistan, the conflict-disaster nexus was emphasized when COI stated that war and recurrent droughts had led to widespread malnutrition and outbreaks of diseases or when COI indicated that the key drivers of food insecurity were armed conflicts, a precarious security situation and recurrent disasters. The connection between disasters and internal displacement was highlighted in many decisions (main reasons for internal displacement prolonged drought and fighting between Taliban insurgents and ISAF). COI also reported about internal displacement solely due to the drought in 2018. In COI on Pakistan information was provided about internal displacement due to conflict and disasters.

During the asylum procedure it is firstly examined whether the applicant qualifies as refugee as defined in the Refugee Convention. When the eligibility criteria of the Convention are not met it will be examined if the person concerned is eligible for subsidiary protection, which is a form of complementary protection based on the principle of non-refoulement. Subsidiary protection status is defined by EU law and granted to a person who does not qualify for refugee status but “in respect of whom substantial grounds have been shown for believing that the person concerned, if returned to his or her country of origin (…) would face a real risk of suffering serious harm” [Directive 2011/95/EU Article 2(f)]14. In Austria, the eligibility criteria for subsidiary protection in Section 8 Asylum Act refer to inter alia Articles 2 or 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)15 and are therefore broader than the definition of serious harm in Article 15(b) Qualification Directive16. When subsidiary protection status is denied, it is evaluated whether an asylum seeker qualifies for humanitarian forms of protection which are not regulated by EU law. In case the application is dismissed by the first-instance authority, the asylum seeker has the right to lodge a complaint before the BVwG.

Of the 646 analyzed decisions of the appellate court, 343 (53.1%) dismissed the appeal. In 268 decisions (41.5%) a subsidiary protection status, in 18 cases (2.8%) a humanitarian protection status and in two cases a refugee status was granted. 15 cases (2.3%) were remitted to a lower instance. These figures do not indicate whether the disaster was the reason for granting protection.

Disasters were sometimes mentioned in the legal reasoning concerning refugee status and played an important role in many decisions concerning the granting of a subsidiary protection status. Even though disasters can be considered in the assessment whether a humanitarian form of protection is to be granted, in none of the decisions analyzed these factors were taken into consideration. Thus, in the following, we will focus on the role of disaster concerning the assessment of a refugee status and a subsidiary protection status.

Disasters played only a marginal role in the assessment relating to refugee status. When disaster situations were considered, they were framed as economic issues, which the court regarded as being not relevant for granting asylum: the court usually argued that the harm would not qualify as persecution since a general situation such as a “desolate economic and social situation” in the context of a disaster could only lead to the granting of refugee status if it deprived of any livelihood. In addition, the court asserted that it would lack a connection to a persecution ground (as stipulated by the Refugee Convention). This was pointed out in the following two examples, the first referring to a claimant from Afghanistan, the second to a claimant from Somalia:

“As a further reason for flight, the applicant argued that he had lost everything in a flood and therefore had to flee. This allegation refers to a natural disaster that had economic consequences for the applicant. Based on this argument, it cannot be determined that the applicant was subjected to persecution in Afghanistan on the grounds of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. (…) In general, economic reasons under Article 1(A) of the Refugee Convention do not, in principle, justify being considered a refugee. They could only be relevant if the complainant was threatened with the complete loss of his livelihood (VwGH 28.6.2005, 2002/01/0414). The loss of the house rented by the complainant due to a flood concerns a natural disaster, which, although it had an economic impact on the complainant, did not amount to a total loss of his livelihood. It would not have been impossible for the complainant to find other accommodation.” (W201 2118203-1, 2019)

“There is therefore no current risk of persecution for a reason given in the Geneva Refugee Convention in the case to be assessed. The generally prevailing precarious security situation in conjunction with the currently prevailing drought and the associated precarious supply situation are adequately taken into account by granting subsidiary protection in the present case (…).” (W103 2148563-1, 2017)

The second quote indicates that subsidiary protection was granted in this case. Disasters primarily played a role in the granting of subsidiary protection, as will be analyzed in the next section.

Disasters were mainly addressed when the court assessed whether the claimant was eligible for subsidiary protection status. They were considered when the court reviewed whether there was a “real risk” of inhuman or degrading treatment upon return to the country of origin (Article 3 ECHR17, Section 8 Asylum Act). In this respect, the court is obliged to assess the individual circumstances of the claimant “in light of the general situation in the receiving country [id est country of origin]” (Blöndal and Arnardóttir, 2019, p. 148; see also e.g., ECtHR, F.G. v Sweden, para 113). Disasters were also considered in the assessment of the availability and reasonableness of an internal protection alternative (IPA) where it is examined whether the claimant can reasonably be expected to relocate to another part of the country of origin.

The disasters considered in the real risk assessment were droughts (Afghanistan, Somalia), floods (Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Somalia), earthquake (Nepal), cyclone (Somalia) and locust plague (Somalia). It depended very much on the country of origin and also on the judge how and to what extent disasters were taken into account.

Disaster was an important factor in the real risk assessment in many Somali cases and a few Nepali cases. In cases relating to Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, disasters only played a minor role and almost exclusively when discussing the general supply and economic situation in the country. With regard to claimants from Afghanistan, only in some exceptional cases the disaster was an important factor in the legal reasoning. For instance, in the following decision of August 2014 the Court saw a “real risk” of an Article 3 ECHR violation as the home region and family of the claimant were severely impacted by the floods so that he could not reach his home and his family would not be able to support him:

“In the specific case of the complainant, this [the problematic security situation (note by the authors)] is compounded by the partial destruction of the infrastructure and probably also the livelihoods of residents of flooded areas due to the devastating rainfall and flooding. The home village and the nearest town are located near a river and it could not be established that this is, firstly, safely accessible and, secondly, habitable, so that in case of doubt—as stated by the complainant—a threat to existence had to be assumed. (…) It is true that the applicant is a healthy young man who is fit for work and (…) grew up in the district of K. and, according to his own statements, has a social or family network there. On the other hand, however, it cannot be determined that he can reach his home village safely and, in addition, it must be assumed that the infrastructure and livelihoods were at least partially destroyed by the floods, which in all probability also had a massive impact on his relatives who are still there. In the event of a return to AFGHANISTAN, the applicant would therefore be left on his own for the time being and would be forced to look for a place to live in KABUL or MAZAR-E SHARIF, even if only temporarily, without having sufficient financial means and family support.” (W208 1434972-1, 2014)

In most of the cases relating to Afghanistan, the Court evaluated the impact of the disaster situation as not severe enough in order to create the “extraordinary, exceptional circumstances” that would be required to create a real risk of violating Article 3 ECHR. For example, concerning the drought disaster in Afghanistan, decisions from the years 2018 and 2019 pointed out that “the reference to a general drought situation is too vague to constitute a real threat situation” (W156 2222474-1, 2019), that although the realization of basic social and economic needs, such as access to work, food, housing and health care, was only possible to a very limited extent due to the drought, the basic supply was “at least fundamentally secure” (W252 2157090-1, 2018), or that the drought in Afghanistan was merely a “unique event” (W242 2125884-1, 2018).

With regard to claimants from Pakistan, the Court argued in most decisions that the home city or home region of the claimant was not or only slightly affected by the floods and that therefore there was not a serious threat to the rights protected by Article 3 ECHR. One decision, in which the claimant had brought forward to have been affected by the floods in 2010, stated:

“In the case at hand, it must be admitted that the complainant comes from an area that was affected by the floods in 2010 (…), but it can be seen from the report (…) that the floods have receded and that the complainant and his family were also able—albeit from a difficult material situation—to cope with their lives to the extent that they were able to provide themselves with the most basic means and make a living.” (E10 425339-1/2012, 2012)

With regard to Somalia, the spectrum of judicial scrutiny concerning the disaster situation ranged from short paragraphs or sentences to detailed, in-depth and extensive analyses of the temporal development of the disaster and its various impacts laid down in several paragraphs of the legal reasoning. Drought was the disaster which was most frequently discussed in the real risk assessments of Somali cases. The following text passage, which emphasizes that the impact of the recurring drought is of “major importance” for the respective case, was repeatedly used in decisions:

“In the present case, the persistently poor supply situation in the entire country, which can be attributed to periodically recurring periods of drought with hunger crises, to the extremely inadequate health care as well as inadequate access to clean drinking water and the lack of a functioning sewage system, is also of major importance. This deteriorated in 2015 due to the food shortage. It can therefore be assumed that the complainant would get into serious difficulties not only for security reasons, but also due to the supply situation.” (W189 2119453-1, 2016; W189 2130153-1, 2017; W189 2127289-1, 2018

In many cases of the Somali sample, the impact of the disaster (in particular drought and floods) was a decisive factor in the legal reasoning concerning the granting of subsidiary protection. This means that the consideration of the disaster and its impact was an important element—if not the most important element—in the legal reasoning. In some cases, the judge held that the drought had led to such a precarious supply situation that “there is no need to deal with other reasons for granting the status of beneficiary of subsidiary protection, because the notorious supply crises already leads to this” (W211 2172503-1, 2018). In another case decided in June 2017, which concerned a claimant who had lived from farming in Southern Somalia, which was among “the worst affected areas by the drought and food insecurity” in Somalia, the Court held:

“Due to the prevailing and established drought disaster and the very precarious supply situation, especially in southern and central Somalia, it must be assumed that the complainant's life and physical integrity would be threatened if he were to return to his home state of Somalia, so that the preconditions for granting subsidiary protection are met.” (W251 2137996-1, 2017)

The last example indicates that the impact of the drought was assessed differently depending on the affectedness of the region of origin. Claimants from the countryside were frequently held to be more affected by the drought and the subsequent famine, as these phenomena “primarily” affected “the inhabitants of the barren regions, who live on their own cattle and agriculture” (W149 1416847-1, 2016).

From mid-2018 onwards, the decisions concerning Somalia reflected a change in the weather conditions. Whereas, until mid-2018 most claimants from Somalia were successful with their appeals, afterwards most decisions reflected the easing of the drought by the rain in spring 2018 which constituted one reason for an increase in the dismissal of appeals. The easing of the drought as a result of the rainfall is indicated in the following example, taken from a decision of July 2018:

“The findings also indicate that Somalia has recently experienced a prolonged drought and a resulting food shortage. (…) For the period June to September 2018, according to recent country reports, an easing of the food supply situation has been forecast in almost all parts of the country as a result of medium to heavy rainfall. There is no indication from the available reporting material that the drought situation in XXXX is currently having an impact that would give rise to a real risk for any resident or returnee there to face a livelihood-threatening emergency situation. The complainant also does not belong to a vulnerable group of people who would be affected by the tense supply situation to a potentially higher extent than the average population of XXXX.” (W111 2150759-1, 2018)

The change in the weather situation was reflected in most decisions. However, not all judges evaluated the onset of the rain in the same way. Some assessed the development more cautiously—for instance, a decision rendered in September 2018 stated that although a “better security of supply is predicted by precipitation” it “has not yet materialized” (W103 2155449-1, 2018). Some judges acknowledged new challenges in the form of floods. For example, one judge pointed out that after “the devastating drought (…), Somalia's two main rivers have overflowed their banks and caused severe flooding” (W240 2189309-1, 2018).

A cyclone was mentioned only once in a real risk assessment in a Somali decision of December 2019. The court held that the cyclone was not relevant as the claimant came from a location not affected by the cyclone (W215 2147286-1, 2019). From September 2019 onwards, the recurrence of the drought in Somalia was indicated in several decisions and in 2020 the locust plague was a new disaster assessed in the legal reasoning of four Somali cases (W159 2117946-2, 2020; W211 2211662-1, 2020; W211 2217305-1, 2020).

The tense supply situation due to the disaster was discussed in the legal reasoning as a factor regarding the general situation in Somalia, usually together or interrelated with other contextual factors such as the general economic or security situation. In most cases, the disaster situation was taken into consideration in addition to the security situation, as is the case in the following rather short text module:

“In addition to this still precarious security situation in the complainant's region of origin, the currently extremely tense general basic supply situation (drought, food shortage) must also be included in the assessment.” (W189 2119453-1, 2016)

In some Somali decisions, the relation between the disaster and the security situation was presented as being interdependent. The Court pointed out that the precarious security situation led to difficulties concerning the supply situation of persons affected by the drought (W149 1432367-1, 2015; W236 2166107-1, 2018), that the supply of humanitarian aid to people affected by the drought was hampered by conflict (W159 2162252-1, 2018; W234 2174194-1, 2018), that conflict parties purposively hampered the provision of humanitarian aid (W252 2160243-1, 2019) and that the drought had fueled clan conflicts (W254 2161633-1, 2018).

The disaster, in particular the drought, was taken into account when reviewing the specific individual situation. The BVwG stressed that not “all people in Somalia are equally affected by the drought and the food shortage and it must be reviewed in each individual case whether the asylum seeker is affected” (W251 2158856-2, 2018, 2.3; W251 2163052-1, 2018, 2.3; W251 2163775-1, 2018, 2.3). The family situation, gender, age, clan membership, profession, education, but also the existence of family and other social networks in the country of origin played an important role in this assessment. In the following, two examples are presented, the first case was decided in July 2018 led to the granting of subsidiary protection, the second case, which was decided in August 2018, was dismissed.

“(…) the general basic supply situation, especially with regard to the prevailing drought and food shortages, must also be included in the assessment in this case. In general, it should be mentioned that periodically recurring droughts with hunger crises, the extremely inadequate health care, the lack of access to clean drinking water and the lack of a functioning sewage system have made Somalia the country with the greatest need for international emergency aid for decades. The applicant, who has spent almost her entire life in Ethiopia, no longer has any upright family and/or social contacts in Somalia. Due to this and in view of the general basic supply situation and the supply crisis in Somalia, it cannot be assumed that the applicant will be able to provide for her livelihood on her own upon her return. Considering the fact that the applicant is a woman who has no school education or is illiterate and has no social and/or family contacts in Somalia and the precarious supply situation in the entire national territory, it can be assumed that it is not sufficiently probable that the applicant will be able to earn a subsistence living upon her return to Somalia.” (W196 2161921-1, 2018)

“The findings also indicate that Somalia has recently experienced a prolonged drought and a resulting food shortage. In many towns in South/Central Somalia, food is barely affordable for IDPs and the very poor population. For the period June to September 2018, according to recent country reports, an easing of the food supply situation has been forecast in almost all parts of the country as a result of medium to heavy rainfall. There is no indication from the available reporting material that the drought situation in Mogadishu is currently having an impact that would give rise to a real risk for any resident or returnee there to face a livelihood-threatening emergency. The complainant also does not belong to a vulnerable group of persons who would be affected by the tense supply situation to a potentially greater extent than the average population of Mogadishu:

The complainant is a young man of working age who is capable of working and whose basic ability to participate in working life can be assumed. (…) It is also not to be assumed that the complainant would show a particular vulnerability in connection with his membership of the Madhiban clan (…). The complainant claimed to be in good health, which is why it cannot be assumed in the present case that any health aspects would prevent the complainant from returning to his home country. (…)” (W196 2139782-1, 2018)

In the first case subsidiary protection was granted. The gender of the claimant, the lack of family and other social support network in the country of origin as well as her educational status played a role with regard to the assessment whether she would be able to provide for herself in the context of the difficult supply situation due to the drought. The second decision dismissed the appeal since, inter alia, the gender of the claimant, his clan membership, his age and employability and his health status did not qualify him for belonging to a “vulnerable group of persons” so that he would not exceptionally be affected by the (easing) disaster situation.

Authorities are obliged to assess the situation after a disaster profoundly and to clarify whether the claimant can reasonably be expected to settle in those parts of the country of origin not affected by the disaster. In 44.3 percent of the decisions, disaster was discussed as a factor in the IPA assessment, in particular concerning the countries of origin Afghanistan and Somalia.

In 81 percent of decisions concerning claimants from Afghanistan the drought situation was discussed in the assessment whether an IPA was available. While in most of these decisions the Court saw in the dangerous security situation an obstacle to the return to the home region, it regarded an IPA in either Mazar-e-Sharif, Herat or Kabul as available and reasonable. It argued, for instance, that the drought was affecting the basic supply of goods in Mazar-e-Sharif and Herat, but “not to an extent that would make it unreasonable or even impossible (…) to rebuild his livelihood there” (W271 2170952-1, 2018, 3.2.4). In some Afghanistan cases, the Court acknowledged the “tense” drought situation but argued that it was not severe enough, as is demonstrated in the following example, taken from a decision rendered in November 2018:

“The situation, especially in Herat, is tense due to the number of IDPs and the notorious current drought in Herat province, but also in Balkh. With regard to the country reports mentioned above, access to shelter, basic services such as sanitary infrastructure, health services and education as well as employment opportunities are basically given in Mazar-e-Sharif as well as in Herat. Nor does the current report indicate that the basic supply of the population (with food and drinking water) is generally no longer guaranteed or that the health care system has collapsed. Neither an existing (or imminent) famine nor an (approaching) humanitarian disaster is described in the reports introduced in the proceedings.” (W265 2174323-1, 2018)

In decisions concerning claimants from Somalia, in 35.8 percent of the sample disaster was discussed in the context of an IPA. In contrast to the Afghanistan cases, disaster and its impacts on the supply situation were seen as an obstacle for an IPA in Somalia, as is demonstrated in the following passage, taken from a decision rendered in August 2019:

“The complainant cannot reasonably be referred to relocating to other parts of Somalia: […] In the case at hand, the currently tense basic supply situation must also be included in the assessment. Even if the new brief information from the LIB [country information sheet (note of the authors)] speaks of an easing of the situation with regard to general food insecurity, it must be taken into account that large parts of Somalia were affected by massive food insecurity in the past year due to the drought. Approximately six and a half million people are dependent on humanitarian aid, with 3.2 million people in need of acute life-saving assistance. Acute malnutrition among children (at least 900,000 affected) and water-borne diseases are widespread, with 874,000 people displaced within Somalia due to the drought in the period January to November 2017.” (W254 2182986-2, 2019, 3.2)

Only in rare cases disaster was discussed as the only reason why an IPA was not available and reasonable in Somalia as is the case in the following example:

“In the light of the ongoing drought and the precarious supply situation which is affecting all of Somalia, an internal protection alternative can neither be expected nor is it reasonable.” (W159 2161606-1, 2017, 3)

In most Somali decisions where disasters, such as drought, floods, rainfalls, “natural events” or locust plagues, were considered in the IPA assessment, they were discussed in addition or in relation to, for example, the (in)availability of support by family members or other relatives and social contacts, clan membership and the security situation. From 2018 onwards, the evaluation of the IPA in Somali cases became more and more detailed. Factors such as health situation and health provision, accessibility of the region where the claimant might be relocated, the situation of IDPs, discrimination, minority status, gender, family status, age, employability, local knowledge, school education and other “individual” qualifications and characteristics were increasingly addressed in the assessment of the IPA. The following example shows that not only the precarious security situation, but also the poor supply situation due to the drought and floods, a lack of family support and a lack of local knowledge concerning the potential relocation place Mogadishu played a role in the assessment:

“An internal protection alternative cannot be expected because of the precarious security situation that still prevails in Somalia and the poor food supply across the country in connection with the drought and meanwhile floods, furthermore, the complainant has never lived in Mogadishu (where the supply situation would be a little better) and has no social or family safety net there that would be able to support him.” (W159 2166202-1, 2018)

However, not in all Somali decisions, a disaster was evaluated to be an obstacle to an IPA. Some decisions stated that the relocation site—in many of these cases the capital Mogadishu—was not affected by the dire supply situation due to the drought to such an extent that relocation was not acceptable and unreasonable (see, for example, W254 2161150-1, 2018).

In the Pakistan cases, the existence of an IPA was used as additional argument for dismissing the appeal after having already argued that no real risk of an Article 3 ECHR violation existed in case of return because the home province was not or only slightly affected by the flood disaster:

“Moreover, the complainant has the option to settle elsewhere in Pakistan. For example, the neighboring province of Punjab is only slightly affected [by the flood (note by the authors)], for example south of the city of Lahore, so that he can settle again in Lahore or Gujranwala. In addition, international aid has already started in the aftermath of the 2010 floods, so it can be assumed that it will be possible to provide supplies.” (L508 2107136-1, 2015)

Disasters did not play a role in relation to assessment of IPA in cases referring to claimants from India or Nepal.

In this case study focusing on the role of disasters in Austrian asylum procedures we provided evidence that disasters are indeed already a factor with regard to mobility towards Europe. We found that in decisions of the appellate court, disasters were relevant in the assessment whether a person is eligible for a subsidiary protection status in relation to some countries of origin, but not in the assessment relating to refugee status or humanitarian forms of protection.

Disasters have an impact on many areas which influence whether a person decides or is forced to move (Black et al., 2011). The analyzed court decisions reflect this aspect. The Austrian appellate court did not look upon the disaster itself but evaluated the impact of the disaster in particular on the supply situation but also on other general (mainly the security situation) and on individual aspects (such as family support, gender, wealth, health or professional situation) when assessing the eligibility for subsidiary protection. We also found that the quality and quantity of COI on disaster-related aspects—which are the basis of the judicial engagement with the impacts of disasters on the living conditions in the country of origin—varies considerably. While the COI relating to the droughts and impacts in Somalia was very detailed and based on a variety of sources, the COI regarding the other countries of origin did not show this level of detail and comprehensiveness.

The results of this case law analysis are important in several ways: Firstly, the results provide information on how the above-mentioned normative protection gap can be addressed from a European perspective (see Section Introduction). The Austrian appellate court's consideration of disasters when assessing the non-refoulement principle under Article 3 ECHR confirms that the latter principle certainly has the potential to do so. Helpful in this context is the particularity of Austrian law that a legal status (subsidiary protection) is linked to the violation of the prohibition of refoulement. However, the Austrian case study also reveals that the non-refoulement principle is not always consistently applied to cases of disaster displacement and that detailed COI on the impacts of disasters is a necessary precondition for the assessment of such claims.

Secondly, the findings of our case study also contribute to rebalance the “uneven geography of research on ‘environmental migration”' (Piguet et al., 2018) that was pointed out at the beginning of this article. The results clearly show that disasters already play a role with regard to mobility towards Europe. Although this is an important result in itself, the findings are also limited and highlight the central importance for further research. On the one hand, the analyzed judgements were restricted to decisions of the appellate court in the Austrian asylum procedure. First instance decisions in the asylum procedure or decisions relating to other immigration categories were not considered in this study. However, since—as also demanded by the Protection Agenda—it is necessary to approach the normative gap from different angles, in particular research on other immigration categories would deserve closer scrutiny in order to get a more comprehensive picture of diverse forms of climate mobility patterns towards Austria.

On the other hand, the results of this study are restricted to Austrian responses concerning the protection gap. Although the case study makes a considerable contribution to the previously scarce research on EU Member States' approaches to dealing with the legal status of third country nationals who are unable to return to their countries of origin due to the impacts of disasters (see e.g., Fornalé, 2020; Schloss, 2021; Scott and Garner, 2022) further research is needed concentrating also on other European countries. As indicated, there is evidence that disasters are already an issue concerning mobility towards other European countries as well. Further—qualitative and quantitative—research on different forms of climate mobility to other European countries as well as on different European legal and policy responses to the phenomenon is necessary to get a better understanding of climate mobility dynamics in Europe.

Thirdly, the findings of this case study also demonstrate that there is a need on a political level to engage more pro-actively with climate mobility in general and disaster displacement in particular towards Europe as this kind of movement is already taking place. There is not only a need on EU level to acknowledge this fact and work towards the development of adequate legal and policy responses, there is also a need for global initiatives such as the PDD or the TFD to engage with hitherto neglected regions such as Europe. Yet, providing more accurate and comprehensive data on this issue is also an important precondition for designing adequate legal and policy responses not only on a national level but also on an EU and on a global level.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This article was based on research conducted in the context of the project - ClimMobil - Judicial and Policy Responses to Climate Change-Related Mobility in the European Union with a Focus on Austria and Sweden (KR18AC0K14747) funded by the Austrian Climate and Energy Fund, ACRP 11th Call. The project was implemented between October 2019 and May 2022 by the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Fundamental and Human Rights (Austria) and the Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (Sweden). The publication of this paper was funded by the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Fundamental and Human Rights, Vienna, Austria.

We thank Roland Schmidt who supported us as a data analyst and provided the graphs. We also thank Florian Hasel for supporting us as an intern during the research project. Finally we acknowledge and thank our research partners, Matthew Scott and Russell Garner (both Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law in Sweden) for intellectual contribution during discussions of our work in the course of the research.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^We understand disaster displacement as one form of climate mobility. According to the Nansen Initiative Protection Agenda vol I, para. 16, ‘[t]he term “disaster displacement” refers to situations where people are forced or obliged to leave their homes or places of habitual residence as a result of a disaster or in order to avoid the impact of an immediate and foreseeable natural hazard.' In the following, this notion of disaster displacement will be used. When referring in general to all potential forms of movements in the context of climate change, we refer to climate mobility or climate-mobile persons.

2. ^See data provided by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) in its annual reports, available on https://www.internal-displacement.org/ (accessed on 13 October 2022).

3. ^Since then, no document has been published by the European Commission that would indicate a fundamental shift away from this assessment. This was also confirmed during interviews carried out with members of the European Commission in 2021. For a detailed analysis, see also Mayrhofer and Ammer (2014).

4. ^See, for example, PDD strategies and workplans available on https://disasterdisplacement.org/resources/page/2 (accessed on 12 October 2022) or 5-year TFD workplan available on https://unfccc.int/process/bodies/constituted-bodies/WIMExCom/TFD (accessed on 12 October 2022).

5. ^According to Eurostat, in 2021 Austria accounted for 6.9% of all first-time asylum applications in the EU, ranking fifth among the main countries of destination in the EU with regard to the total number of first-time asylum applications in the EU.

6. ^As a consequence, the International Law Commission has included challenges relating to the status of persons affected by sea level rise in its work program, see https://legal.un.org/ilc/guide/8_9.shtml.

7. ^While international refugee law is also applicable in the context of disasters (UNHCR, 2020, p. 6; Goodwin-Gill and McAdam, 2021, p. 643–644), it will be of “limited utility in situations of disaster displacement” (McAdam, 2021, p. 836), since “[o]n their own […] the impacts of climate change or disasters will generally not satisfy the meaning of ‘persecution' under the Refugee Convention” given the requirement of human agency and of a nexus to a persecution ground (Goodwin-Gill and McAdam, 2021, p. 644). Still, some scholars point to the unequal impacts of climate change reinforcing existing patterns of discrimination (Scott, 2020).

8. ^In Teitiota v New Zealand the UN Human Rights Committee stated that “the effects of climate change … may expose individuals to a violation of their rights under articles 6 or 7 of the Covenant [right to life and prohibition of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment], thereby triggering the non-refoulement obligations of sending states” (para 9.11). However, it based its decision on the right to life. Thus, there is no detailed reasoning in relation to Article 7 ICCPR. For a detailed analysis see (McAdam, 2020).

9. ^For example, the 2017 extensive drought in Somalia which resulted in the failing of both rainy seasons in that year, was demonstrated to be influenced by climate change. Global warming doubled the probability of the drought in 2017 in East Africa and contributed to widespread food insecurity (Funk et al., 2019, p. S55). This drought plays an important role in a substantial part of the Somali decisions, which were analyzed in this study.

10. ^The date of the search of the database for the data presented in this article is 3 May 2022 (Figures 1–4).

11. ^Figures 1–3 were designed by Roland Schmidt.

12. ^All quotations cited in this article from the decisions analyzed have been translated from German into English by the authors.

13. ^E.g., Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC); different UN sources [UN OCHA, UN OHCHR, UNHCR, UNSOM, UNSC, Somalia and Eritrea Monitoring Group (SEMG), FAO, World Bank], Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET); FAO-administered Department of Nutrition Analysis (FSNAU—Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit); Amnesty International and other NGOs; different news channels and papers; different national sources.

14. ^Serious harm is defined in Article 15 of Directive 2011/95/EU in the following way: “Serious harm consists of: (a) the death penalty or execution; or (b) torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment of an applicant in the country of origin; or (c) serious and individual threat to a civilian's life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in situations of international or internal armed conflict.” Of relevance for disaster displacement is Article 15b.

15. ^“Article 2 ECHR, Right to life: 1. Everyone's right to life shall be protected by law. […]; Article 3 ECHR, Prohibition of torture: No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”.