94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Clim., 17 May 2022

Sec. Carbon Dioxide Removal

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.869456

This article is part of the Research TopicEnhanced Weathering and Synergistic Combinations with Other CDR MethodsView all 12 articles

Arthur Vienne1*

Arthur Vienne1* Silvia Poblador1

Silvia Poblador1 Miguel Portillo-Estrada1

Miguel Portillo-Estrada1 Jens Hartmann2

Jens Hartmann2 Samuel Ijiehon1

Samuel Ijiehon1 Peter Wade3

Peter Wade3 Sara Vicca1

Sara Vicca1Enhanced weathering (EW) of silicate rocks can remove CO2 from the atmosphere, while potentially delivering co-benefits for agriculture (e.g., reduced nitrogen losses, increased yields). However, quantification of inorganic carbon sequestration through EW and potential risks in terms of heavy metal contamination have rarely been assessed. Here, we investigate EW in a mesocosm experiment with Solanum tuberosum growing on alkaline soil. Amendment with 50 t basalt/ha significantly increased alkalinity in soil pore water and in the leachate losses, indicating significant basalt weathering. We did not find a significant change in TIC, which was likely because the duration of the experiment (99 days) was too short for carbonate precipitation to become detectable. A 1D reactive transport model (PHREEQC) predicted 0.77 t CO2/ha sequestered over the 99 days of the experiment and 1.83 and 4.48 t CO2/ha after 1 and 5 years, respectively. Comparison of experimental and modeled cation pore water Mg concentrations at the onset of this experiment showed a factor three underestimation of Mg concentrations by the model and hence indicates an underestimation of modeled CO2 sequestration. Moreover, pore water Ca concentrations were underestimated, indicating that the calcite precipitation rate was overestimated by this model. Importantly, basalt amendment did not negatively affect potato growth and yield (which even tended to increase), despite increased Al availability in this alkaline soil. Soil and pore water Ni increased upon basalt addition, but Ni levels remained below regulatory environmental quality standards and Ni concentrations in leachates and plant tissues did not increase. Last, basalt amendment significantly decreased nitrogen leaching, indicating the potential for EW to provide benefits for agriculture and for the environment.

In order to limit global warming to well below 2°C, model projections indicate that both rapid decarbonisation and negative emission technologies (NETs) will be required (Gasser et al., 2015). Hence, in addition to conventional mitigation there is an urgent need for development of scalable NETs that safely remove CO2 from the atmosphere. A promising, yet poorly studied NET, is enhanced weathering (EW) of silicate minerals, which is particularly of interest due to its application potential in agriculture (van Straaten, 2002; Hartmann et al., 2013; Haque et al., 2019; Beerling et al., 2020). This technique aims to accelerate natural weathering, a process that has been responsible for stabilizing climate over geological timescales, which naturally captures 1.1 Gt of CO2 per year (or ca. 3% of current global CO2-emissions; Strefler et al., 2018; Roser and Ritchie, 2020). The idea behind EW is to speed up this natural process by grinding silicate rocks to powder, hence increasing the surface area (Schuiling and Krijgsman, 2006; Hartmann et al., 2013) and bringing these in a moisture-retaining environment favorable to weathering, e.g., agricultural soils.

Agricultural enhanced weathering is considered a promising NET because co-utilization of surface area with agricultural land is possible and competition with food production is avoided (in contrast to some other NETs such as afforestation). Furthermore, the cost of terrestrial EW was recently estimated to be competitive to those of other NETs, such as Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage (DACCS) (Strefler et al., 2018; Beerling et al., 2020). As the original focus of agricultural silicate rock amendment was delivering agricultural benefits rather than CO2 sequestration (van Straaten, 2002), only few studies have quantified the associated CO2 sequestration.

Silicate weathering involves the reaction of silicate minerals with CO2 and water to form bicarbonate (HCO) and carbonate (CO) ions and cations (mainly Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and K+). Ca2+ and Mg2+ may either precipitate in the soil (degassing one mole of CO2 per mole of divalent cation) to form solid carbonates or are transported to streams and ultimately the ocean. Hence, in order to quantify total inorganic CO2 sequestration through EW, both changes in total inorganic carbon (TIC) in the soil (solid phase) and the exported dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) through runoff should be considered. The few studies that estimated CO2 sequestration thus far, usually calculated CO2 sequestration based on cation changes in leachates or soil exchangeable pools (ten Berge et al., 2012; Dietzen et al., 2018; Amann et al., 2020). However, changes in soil cations are confounded by plant uptake, soil adsorption, and cation exchange. Others considered soil TIC changes but did not account for DIC leaching (Manning et al., 2013). Quantification of DIC leaching losses is difficult in the field, but may be estimated using a reactive transport model such as PHREEQC. This model can account for the carbonate and cation flows through the soil and estimate CO2 sequestration through EW, but these estimates have not yet been verified with experimental data.

A key abiotic factor influencing weathering rates (and therefore carbon sequestration) is pH. Weathering rates are typically assumed to increase with decreasing pH, but this relationship differs between silicate minerals. According to Brantley et al. (2008), mineral dissolution of the silicate minerals contained in basalt (mainly olivine, augite, plagioclase) proceeds via an acidic and via an alkaline pathway and is lowest around pH five. While olivine and augite dissolution increase with decreasing pH, weathering of Al-containing Ca-plagioclases increases at alkaline pH (Qian and Schoenau, 2002) (Supplementary Figure SF1). Not only dissolution of ions into the liquid phase is a pH dependent process. Reprecipitation of these ions is also influenced by pH. In alkaline soils, precipitation of HCO in carbonates is promoted, which can stimulate weathering rates in the longer term by removing weathering products from soil solutions (Bose and Satyanarayana, 2017). For example, Fe can be removed from solution at alkaline pH through precipitation of Fe(OH)3 and Fe-bearing carbonates such as siderite, ankerite and ferroan calcite. Likewise, Al can precipitate as Al(OH)3 at alkaline pH. Alkaline pH can thus increase both dissolution of Al-bearing plagioclases and Al hydroxide precipitation, indicating that, in contrast to what has been suggested in some studies (Beerling et al., 2018), EW application should not necessarily be focused on acidic soils.

Although research on the drivers of EW has mostly focused on abiotic factors, several biotic processes can also strongly influence mineral weathering, and some of these effects may be stronger in alkaline soils (Vicca et al., 2022). For example, enzymes of the group carbonic anhydrases (CAs) (which catalyse HCO formation and are found in all domains of life) were found to be most efficient at pH above seven and may support the silicate dissolution process in alkaline soils (Demir et al., 2001). Xiao et al. (2015) observed promoted wollastonite (CaSiO3) weathering (Ca-release) upon addition of CA from Bacillus mucilaginosus.

Apart from potential enhancement of mineral dissolution through (a)biotic mechanisms, a considerable share of land area is alkaline. According to the Harmonized World Soil Database (FAO), about 23% of all soils have an alkaline pH (>7) (Fischer et al., 2008). Although EW is currently considered to be most effective for CO2 removal in tropical areas (Hartmann et al., 2013), alkaline soils clearly hold considerable potential for CO2 removal through EW, but their CO2 sequestration potential, as well as potential side-effects require experimental verification.

Silicate rock dust have been previously applied to agricultural soil because of its potential benefits for agriculture. These include increased cation exchange capacity (CEC) and crop yields, increased plant nutrient concentrations and countered soil acidification. Moreover, silicate addition can also increase plant pest- and drought resistance (Hartmann et al., 2013; Blanc-Betes et al., 2021) and reduce N-losses (N2O and NO emissions). Similarly to agricultural liming, EW induces a pH increase in acid soils, which is hypothesized to reduce nitrogen losses because the activity of denitrifying enzymes was found to increase at neutral pH (Bakken et al., 2012; Qu et al., 2014; Kantola et al., 2017).

On the other hand, large-scale EW adoption may hold the risk of heavy metal (especially Ni) contamination, particularly when fast-weathering ultramafic minerals are used (Haque et al., 2020a). In this context, basalt rock is proposed as an alternative for the ultramafic mineral olivine, as basalt contains less Ni (Amann and Hartmann, 2019). Interestingly, alkaline soils may reduce the risk of Ni leaching to surface waters, as more Ni can be adsorbed in soils at alkaline pH. Ni can form insoluble hydroxides and the presence of carbonates may also lead to an increase in the retention of Ni as carbonate salt in soil (Sathya and Mahimairaja, 2015). Although terrestrial EW focus shifted to basalt and less problems in Ni contamination are expected with this rock in alkaline soils, a comparison with regulatory environmental quality standards (EQSs) remains necessary to ensure environmental safety. As aforementioned, Al release by weathering of Al-bearing plagioclases is stimulated in alkaline soils, as well as Al(OH)3 precipitation. The resulting effect may increase Al concentration (Al toxicity) in alkaline soil pore water, in contrast with EW in acid soils, where pH increase decreases Al availability.

We set up a mesocosm experiment to investigate carbon sequestration, risks and co-benefits of EW using basalt rock powder with potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) as this is the world's third most important crop in terms of human consumption, after wheat and rice (FAOSTAT, 2013). In addition, from a sustainable development goals (SDGs) perspective, it is also a highly relevant crop as potatoes are grown in regions that are experiencing high poverty and malnutrition (Campos and Ortiz, 2019). We quantified CO2 sequestration through EW based on experimental data and using the PHREEQC 1D reactive transport model. Further, we hypothesized that potato tuber yield would benefit from the increase in base cations (released from the basalt), while we expected Ni leaching to remain within the safe range according to environmental quality standards. In addition, we expected that basalt addition would reduce N leaching.

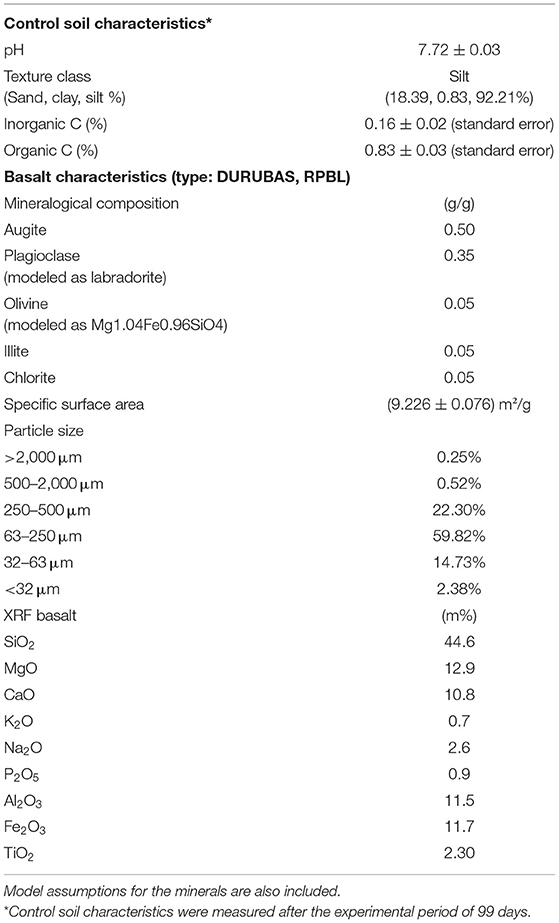

A mesocosm experiment with 10 mesocosms (five Control and five basalt-amended) was constructed at the experimental site at the Drie Eiken Campus of the University of Antwerp (Belgium, 51°09′ N, 04°24′ E). The mesocosms (1 m height, radius = 0.25 m) were placed under a transparent shelter, hence excluding natural rainfall. In April 2019, the mesocosms were filled with loamy soil (Table 1). In the basalt amended mesocosms, a mass equivalent to 50 t basalt ha-1 was homogeneously mixed into the upper 20 cm. On 21 May 2019, three potatoes (Solanum tuberosum “Nicola,” purchased at AVESTA, Belgium) were planted in each mesocosm and all pots received 60 g of NPK fertilizers (5 – 4 – 15 + Bacillus). All mesocosms were watered regularly with tap water (composition: see Supplementary Table ST7). Soil pore water was sampled from two rhizon samplers (Rhizon Flex, Rhizosphere Research Products B.V., Wageningen, NL) installed at five cm depth in each mesocosm. To allow leachate collection, mesocosms had a two cm diameter hole at the bottom. On the inside, the bottom of the pot was covered with a root exclusion math to prevent soil export through leaching. A glass collector (one liter volume) was placed under the mesocosm to collect the leachates. Leachate volumes were determined throughout the experiment and samples for chemical analyses were collected on six occasions (23/5; 28/5; 6/6; 16/6; 7/8; 13/8; 20/8 in 2019). Nitrogen in leachates was analyzed on the last three dates.

Table 1. Characterization of soil (pH, texture, and organic C) and basalt (composition, specific surface area, particle size distribution, and XRF data).

Basalt characteristics are given in Table 1. Surface area was measured in triplicate with Kr using a Quantachrome surface area analyser. Basalt (type: DURUBAS) composition was determined by the supplier [Rheinischen Provinzial-Basalt- und Lavawerke (RPBL)]. Basalt particle size distribution was determined by sieve separation.

On the 27th of August 2019, all plants were harvested and separated into aboveground and belowground parts. After drying (48 h at 70°C, potatoes were cut to speed up the drying process), above- and belowground (potato tuber) biomass was determined. Potato tubers were analyzed for Mg, Ca, K, Si, Al, and Ni by ICP-OES (iCAP 6300 duo, Thermo Scientific). Ni and Al were determined after a destruction of 0.2 g sample with 20 mL HNO3. For Ca, Mg and K, 0.3 g of sample was destructed with a H2SO4/Se/salicylic acid mixture according to the protocol of Walinga et al. (1989). For Si, 30 mg sample was destructed with 20 mL of 0.5 N NaOH, this was done in triplicate.

Soil cores (5 cm length) were taken across the depth of the mesocosm (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, 20–30 cm, 30–50 cm, 50–75 cm, and 75–100 cm). Immediately after collection, the cores were dried at 105°C for 3 days to determine water content (g H2O/g soil) and bulk density. Water-filled porosity was calculated by multiplying water content with bulk density. The soil samples were ground to pass a 0.2 mm sieve with an ultra-centrifugal mill (Model ZM 200, Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany).

Soil Total Carbon (TC) was determined with an elemental analyzer (Flash 2000 CN Soil Analyser, Interscience, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium). Total Organic Carbon (TOC) of each 20 cm across mesocosms was determined in the elemental analyser after acid hydrolysis of the original sample: 1 g of soil was digested with excess of 6N HCl at 80°C to and the residue dried. The remaining sample was analyzed giving TOC as a result, and TIC was calculated as the difference between TC and TOC.

Other soil elements (Mg, Ca, K, Al, and Ni) for samples taken at 10, 25, and 40 cm depth were determined using ICP-OES. In this way, concentrations in the topsoil, the basalt-soil mixing layer and deeper layers were measured. Brown's procedures (1943) were used for CEC and total exchangeable bases (TEB), for which 1M NH4Acetate at pH seven served as the extractant (Brown, 1943). CEC and TEB were also measured in soils sampled at 10, 25, and 40 cm depth.

Leachate and pore water samples for Ca, Mg, K, Fe, Al analyses were filtered over a 0.45 μm PET filter and were conserved adding 1.5 mL 15.8 N HNO3 (69%) to 30 mL of sample until analysis with ICP-OES (iCAP 6300 duo, Thermo Scientific). Nitrogen (NH-N, NO-N) and alkalinity were determined using a Skalar (SAN++) continuous flow analyzer. Nitrogen samples were conserved in tubes with 20 μL 10 N HCl before analysis. pH was determined using a HI3220 pH/ORP meter. For monitoring soil nutrient availability, we used commercially available PRS™ probes (Western Ag Global, Saskatoon, SK, Canada), which provide proxies for plant available ions in soil solution while in contact with the soil (Gudbrandsson et al., 2011). Eight PRS probes (four for cation and four for anion, Figure 1) were installed in each mesocosm twice during the growing season, on 7th of June and 6th of August, and were retrieved 7 days after burial. Total N leaching was calculated as the sum of NH4-N and NO3-N leaching.

Figure 1. A mesocosm containing three potato plants, a stainless steel collar, PRS probes and rhizon samplers.

Soil CO2 efflux was measured on three occasions on a shallow stainless steel collar (8 cm high, 10 cm diameter) which was installed at four cm depth in each mesocosm (Figure 1). Measurements were made using a custom-built soil chamber (0.98 L), which was connected to a portable EGM-5 infrared gas analyzer (PP Systems, Hitchin, UK). We measured the increase in soil CO2 concentration until a CO2 concentration difference of 50 ppm was reached, or during 120 s in case of lower increases.

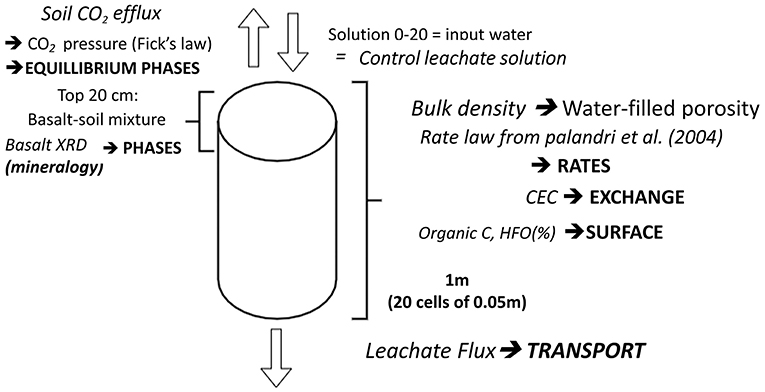

Carbon sequestration was modeled using the PHREEQC geochemical platform (Parkhurst and Appelo, 2013). We followed the approach of Kelland et al. (2020), an overview of the model's required inputs is given in Figure 2. The model details and calculation of the model's inputs can be found in Supplementary Material 2. The model includes different PHREEQC functionalities (phases, dissolution rates, solutions, transport, equilibrium phases, cation exchange, and surface adsorption) which are indicated in bold. The 1 m long mesocosms were divided into 20 cells of 5 cm height. Basalt was added to the four top layers (20 cm topsoil). Hence, in the phases block, basalt mineralogy and thermodynamic data of mineral dissolution (log k and enthalpy) are entered for the first four cells. The possibility of inclusion of minerals within other mineral phases may occur but was not included in our model. Basalt mineral dissolution according to the rate law of Palandri and Kharaka (2004) is inserted in the Rates functionality. The selection of parameters for this rate law is discussed in Section 1.1 of Supplementary Material 1. For the mineral augite (50 m% of the utilized DURUBAS basalt), two different rate laws were considered in different simulations (the first rate law utilizes parameters as in Palandri and Kharaka (2004), while the second follows the approach of Knauss et al. (1993) at 25°C with an Arrhenius temperature correction to the experimental temperature (Supplementary Table ST1). Plagioclase was simulated as labradorite because labradorite is intermediate in the Na-Ca plagioclase series and the Ca content of the plagioclase in the durubas basalt is unknown. For labradorite, alkaline dissolution kinetic parameters were considered (Supplementary Figure SF1). In order to simulate mineral weathering in the control soil, the input solution (that is added on the top layer of all simulated columns) equals the composition of the efflux soil solution in the control treatment. Cations (e.g., Ca or Mg) are added to this control solution according to the abovementioned rate law. This solution is in equilibrium with equilibrium phases (gases and minerals, e.g., CO2, calcite and Al(OH)3).

Figure 2. Overview of the PHREEQC reactive transport model. PHREEQC functions are indicated in bold, model inputs are written in italics.

CO2 partial pressure was entered in the equilibrium phases functionality and was calculated using Fick's law (as in Roland et al., 2015), using the average experimental soil CO2 efflux (F in Equation 1). The difference between the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere and soil (C) increases with depth (z). Assuming a constant atmospheric CO2 concentration of 414 ppm, soil CO2 concentration at each soil depth was calculated and converted to pressure by multiplying with the universal gas constant and the average experimental soil temperature (285 K). Water-filled porosity was calculated from the soil bulk density (1.40 kg soil.l-1 soil) and equaled 0.14 l H2O/l soil (Equation 3). The diffusion coefficient, Ds (Equation 4), was calculated from the total and water-filled porosity (Equations 2, 3) as in Roland et al. (2015).

Cations can complex on surfaces such as organic matter or ferrihydrite (HFO). Surface complexation of species on organic matter is included by implementing the WHAM model using the organic carbon content of the soil (control group) (Lawlor, 1998). Exchange of cations with soils is also included as the measured cation exchange capacity (CEC) is inserted in the “Exchange” functionality. Finally, in the transport functionality, the average observed leachate flux (7.61L/99 days/mesocosm) was inserted.

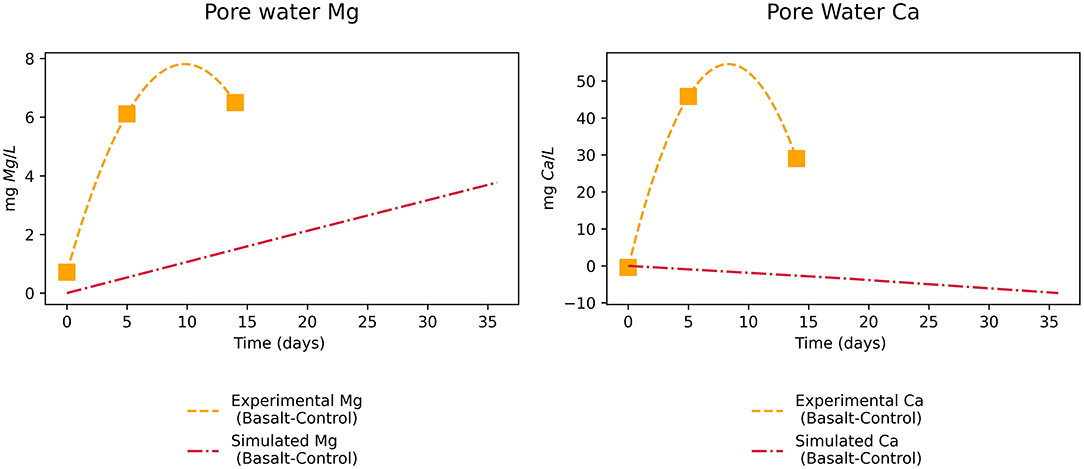

The 1D reactive transport model was run for a scenario with and without basalt amendment. Simulated results of weathering products (Ca, Mg) in the first cells were compared with experimental concentrations of Mg and Ca in the topsoil pore water (Figure 6).

One-way Anova was used for detecting statistical differences in biomass and soil composition among treatments. For analyses that were repeated in time (leachate and pore water chemistry measurements), a repeated measures one-way Anova was used using the lmer package in R studio Version 1.4.1106. Normality and homoscedasticity assumptions underlying statistical tests were evaluated with the Shapiro-Wilk test. If residuals were not normally distributed a log10 transformation on the variable was performed. Total mesocosm TIC was calculated using Equation 5 (with n = number of depths).

In order to calculate total inorganic CO2 (IC) sequestration, the total sequestered mass of carbon as DIC in leachates and as TIC changes are summed. The CO2 sequestration through DIC leaching losses was calculated by multiplying the observed leachate flow (7.61 L/mesocosm/99 days) with the difference in average DIC concentration among treatments. DIC was calculated from the experimentally measured alkalinity with a slope of 6.70 gDIC/Equivalent (Supplementary Figure SF5).

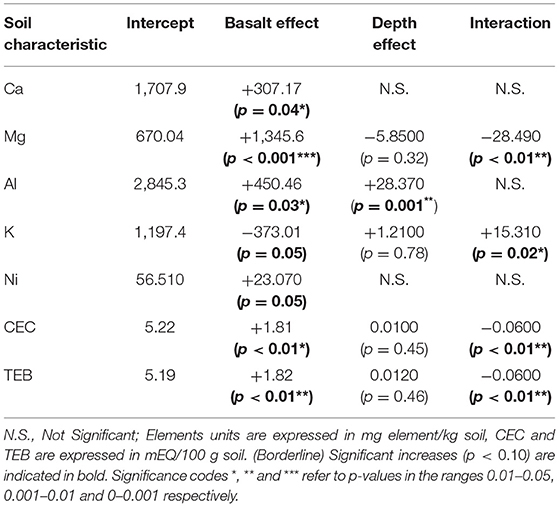

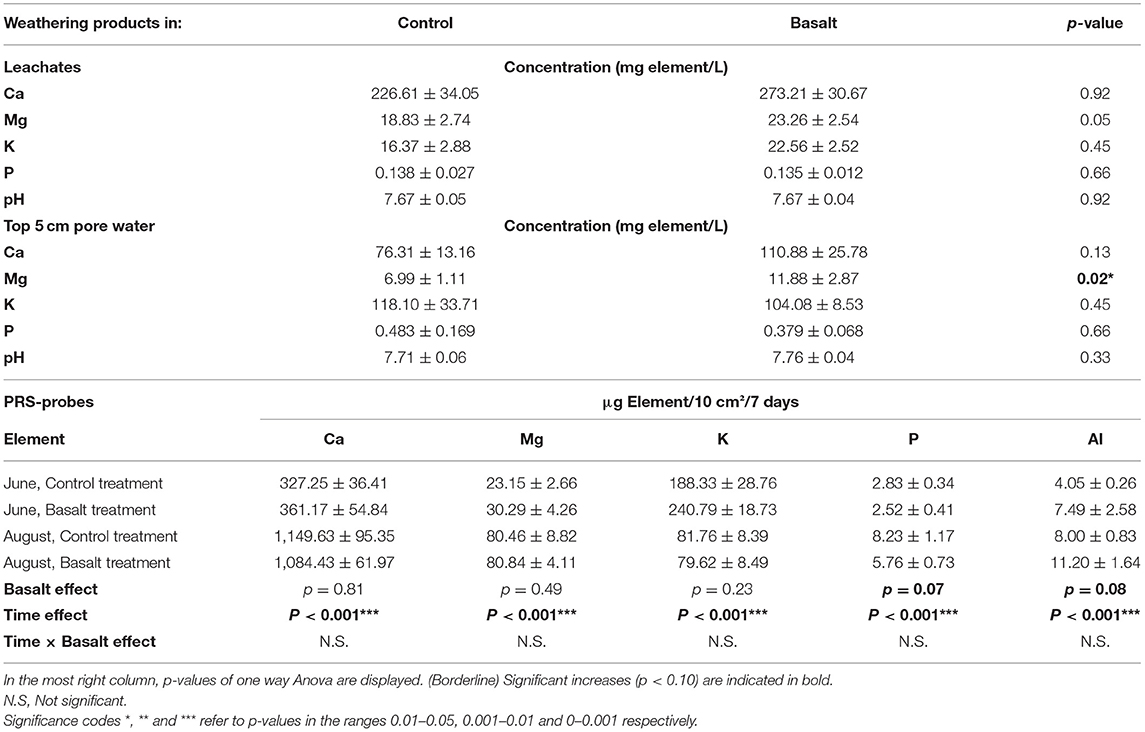

Basalt addition significantly altered soil and soil pore water chemistry. The strongest changes of basalt amendment were observed for Mg, for which the basalt effect increased the topsoil Mg concentration with about 200% (Table 2). A clear negative basalt x depth interaction effect was found: the basalt effect on soil Mg decreased with depth. Likewise, basalt amendment increased soil CEC (and TEB), especially in the topsoil (a significantly negative basalt x depth interaction effect was found for CEC and TEB). Soil pore water Mg concentration also increased significantly, and the Ca concentration tended to increase (Table 3). On the other hand, the PRS probes indicated no significant basalt effect on Mg and Ca availability, although we observed a tendency for an increase at the start of the experiment. These PRS probe data also revealed a strong decline in availability of Ca, Mg and other cations over the course of the experiment.

Table 2. Multiple regression parameters of different soil elements analysed (Ca, Mg, Al, K, Ni), cation exchange capacity (CEC) and total exchangable bases (TEB).

Table 3. Overview of weathering products (Ca, Mg, K, and P) concentrations ± standard error observed in leachates and pore water samples over the entire season and in PRS probes at two occasions (June and August).

Topsoil K decreased with basalt addition, and increased at lower depths in the basalt treatment (i.e., a significantly positive depth × basalt interaction was found). This decrease in topsoil K is not due to a soil dilution effect because this basalt contains more K than background soil (Table 4). PRS probes in the topsoil showed an increase in topsoil K in June, but not in August. Al increased significantly in the soil (p = 0.03*). The PRS probes revealed a borderline significant increase in Al (Table 3; p = 0.08), indicating weathering of Al-bearing silicate minerals Ca-plagioclase and/or augite. Basalt did not increase Fe in PRS probes (p = 0.99). We observe a decrease of P in PRS probes of the basalt treatment, leading to a borderline significant negative basalt effect (p = 0.07). pH in the pore water and leachates did not significantly change upon basalt amendment, and the system was buffered at pH 7.7 (Table 3).

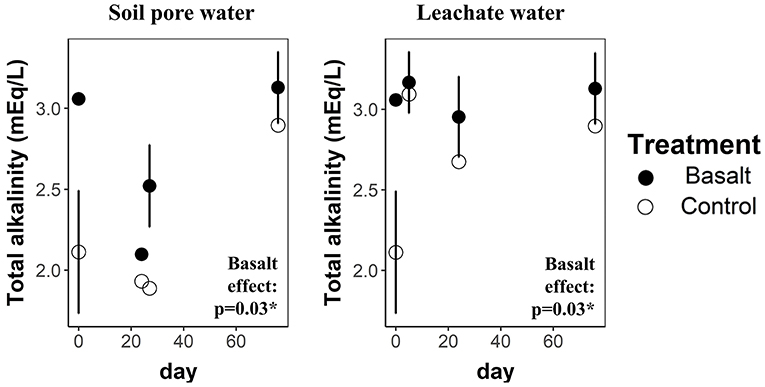

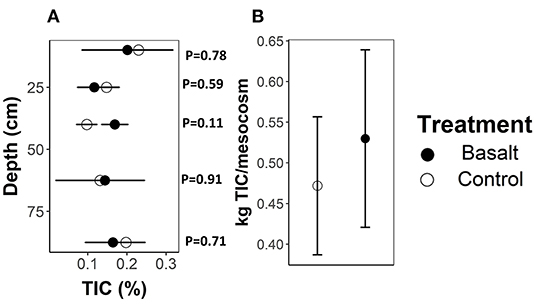

On average, basalt weathering increased leachate and topsoil pore water (0–5 cm) alkalinity with 8 and 29%, respectively (Figure 3). After 99 days of experiment, a higher amount of DIC (calculated from TA), equivalent to only 4.77 kgCO2/ha, had leached from the basalt amended system compared to the control system (Table 4). We found no significant basalt effect on soil TIC content (Figure 4). Note that the large uncertainity on TIC resulted in a large uncertainty on the estimate of ΔIC.

Figure 3. Total alkalinity (mEq L-1) in pore water and leachates in function of time (days) for basalt and control treatments. Error bars represent averages ± standard errors. Significance codes *, ** and *** refer to p-values in the ranges 0.01–0.05, 0.001–0.01 and 0–0.001 respectively.

Figure 4. (A) TIC (%) for different soil depths (cm) and (B) total kg TIC mesocosm-1 for basalt and control treatments. Error bars represent averages ± standard errors.

During the timespan of the experiment, the PHREEQC model predicts a difference of 4.39 gTIC/mesocosm formation between basalt and control treatment in the top 20 cm mesocosm. Given the mass of soil in the column (54.9 kg in the top 20 cm column), this results in an increase of about only 0.01% inorganic carbon (Supplementary Table ST3; Supplementary Figure SF9). Hence, given the variation in measured TIC percentages (Figure 4A), this indicates that the uncertainty on the measurements is larger than the modeled differences in TIC. Indeed, although TIC tended to be higher in the basalt amended soils, this increase was not statistically significant (Figure 4B).

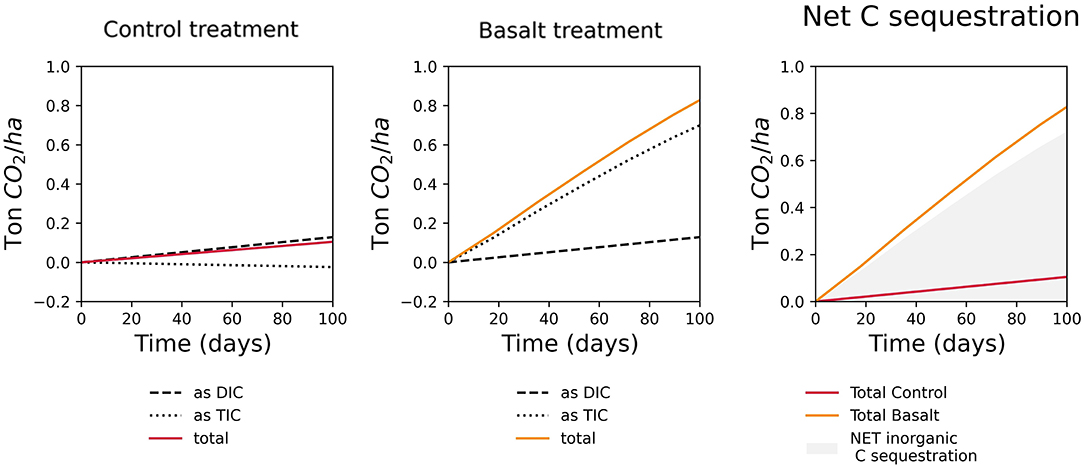

Modeled IC sequestration during the duration of the experiment was 0.77 t CO2/ha (Figure 5). A model run beyond the experimental period indicated a CO2 sequestration of 1.83 and 4.48 t CO2/ha after 1 and 5 years, respectively (Supplementary Table ST3). The evolution of olivine, labradorite and augite dissolution is shown in Supplementary Figure SF8.

Figure 5. Simulated inorganic carbon sequestration (ton CO2 ha-1) in function of time (days), for 100 days of experiment in the control and basalt treatment. Net inorganic C sequestration (in grey) results from the difference between the basalt and control treatment.

We calculated the difference in Mg and Ca pore water concentration between the basalt and control treatment and compared this delta for experimental data and simulated values (Figure 6). This indicated that the model underestimated initial increases of Mg in the pore water by a factor 3. For Ca, simulated concentrations were lower in the basalt treatment than in the control treatment, while experimental results showed the opposite pattern.

Figure 6. Experimental and simulated Mg and Ca increase in pore water (mg L-1) after basalt amendment in function of time (days).

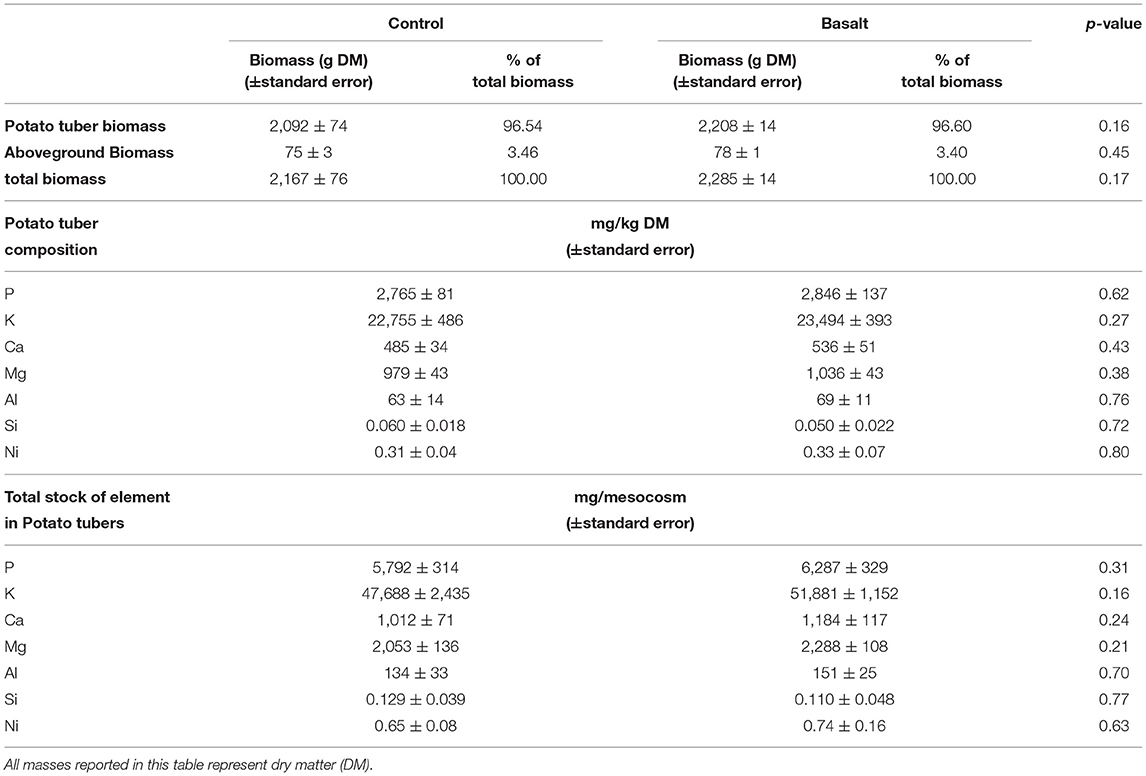

Basalt addition tended to increase aboveground biomass and potato tuber yield (albeit not statistically significantly; p = 0.16, p = 0.45). No significant changes in potato tuber Mg, Ca, P, Si, and Ni concentrations were detected upon basalt amendment (Table 5). However, basalt induced a positive trend in potato stocks of K (p = 0.16), Mg (p = 0.21), Ca (p = 0.24), and P (p = 0.31).

Table 5. Overview of (aboveground, potato tuber or total) biomass and element stocks in potato tuber (96 m% of the total biomass).

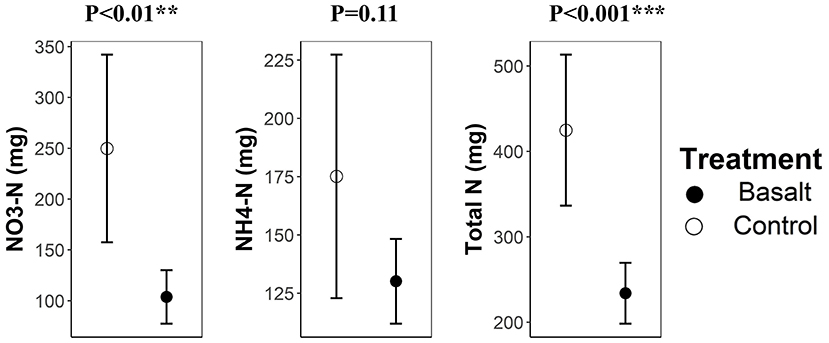

Nitrogen leaching was significantly lower in the basalt treatment than in the control (Figure 7). This reduction in nitrogen leaching was mainly due to the decrease in NO-N leaching. Average N leaching decreased with about 45% upon basalt amendment.

Figure 7. Nitrogen leaching (mg N mesocosm-1) among treatments. Error bars represent averages ± standard errors. Significance codes *, ** and *** refer to p-values in the ranges 0.01–0.05, 0.001–0.01, and 0–0.001 respectively.

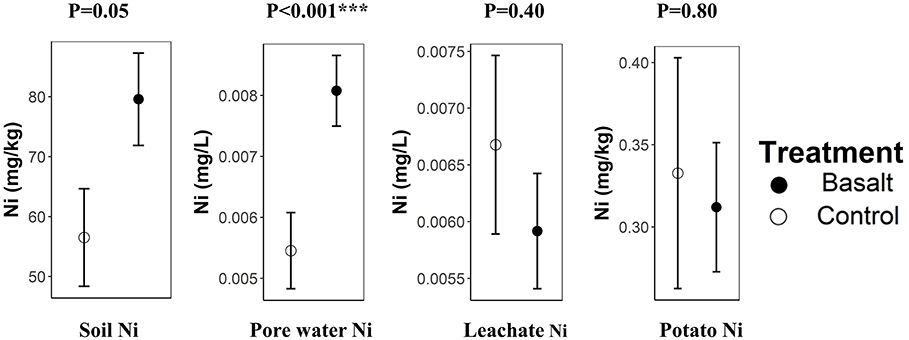

In the soil (0–50 cm), a 41% increase of Ni was observed (p = 0.05). Ni also increased significantly in the topsoil (0–5 cm) pore water (Figure 8). In contrast, leached Ni tended to decrease upon basalt addition (p = 0.40). Hence, the added Ni was retained in the soil system. Potato tuber Ni content did not significantly differ among treatments (p = 0.80). Despite the borderline significant Al increase observed in PRS probes, potato tuber Al was not significantly increased in the basalt treatment (p = 0.70; Table 5).

Figure 8. Nickel differences among treatments in the soil (mg Ni kg-1 soil), pore water (mg Ni L-1), leachates (mg Ni L-1), and potato tubers (mg Ni kg-1 tuber). Error bars represent averages ± standard errors. Significance codes *, ** and *** refer to p-values in the ranges 0.01–0.05, 0.001–0.01, and 0–0.001 respectively.

Based on the XRF data of our, we estimate a maximum CO2 sequestration of 223 and 416 kg CO2/t basalt, after complete dissolution and reaction via mineral carbonation (MC; all inorganic carbon precipitates) or enhanced weathering (EW; all inorganic carbon is rinsed out of the system as dissolved C), respectively (Renforth, 2019) (see also Section 1.11 in Supplementary Material 1). Hence, applying 50 t of our basalt per ha corresponds with a theoretical maximum of 20.8 and 11.2 t CO2/ha through EW and MC, respectively. It may take several decades for this to be reached. We recognize that applying several tens of tonnes basalt ha−1 in practice would result in substantial transportation costs and that this application rate is higher than for conventional fertilizers. However, costs of C sequestration through enhanced weathering of basalt are estimated at about US$80–180 t−1 CO2 (Beerling et al., 2020), which corresponds roughly to the world bank estimate of the carbon price in 2050 (100–150$ t−1CO2) and current EU-ETS carbon price, which already exceeded 100 US$ t−1 CO2 in 2022.

We investigated inorganic CO2 sequestration by experimentally quantifying changes in both DIC and TIC. Over the short duration of our experiment, only a small amount of DIC (4.77 kgCO2-eq/ha) had leached out. The experiment was conducted during summer season, when evapotranspiration was high and leaching losses were small. More DIC might leach out during winter, when evapotranspiration is low. Our PHREEQC simulations predicted carbonates to precipitate only in the basalt amended topsoil and not in deeper layers, indicating that in our experiment sequestered inorganic carbon should be retained in the top soil. Large uncertainty on TIC measurements, resulting from heterogeneity in background soil TIC complicated exact determination of IC sequestration. This result is in line with Kelland et al. (2020), who found no significant TIC changes in a similar short-term mesocosm experiment with basalt rock powder. In contrast, Haque et al. (2019) did detect a significant CO2 sequestration of 39.3 t CO2/ha through TIC changes in a mesocosm experiment of 55 days. Also in some field studies with smaller application rates, TIC changes were detectable after 5 months (Haque et al., 2020b). The latter experiments used the faster weathering silicate mineral wollastonite. Besides addition of large amounts of fast-weathering silicates, long-term monitoring also increases the potential to detect TIC changes upon basalt amendment. In a field experiment in which soil was amended with basaltic quarry fines, Manning et al. (2013) detected a significant increase of TIC after 4 years and estimated CO2 sequestration at 17.6 t CO2/ha/y.

For detection of significant TIC changes with rocks and minerals that have weathering rates similar to basalt, our results indicate that multi-year experiments are required. PHREEQC simulations show that the standard error on TIC measurements (ranging from 0.03 to 0.12% across the different depths) was larger than the modeled differences in TIC (of about 0.01%) obtained for the experimental duration. Based on our simulations, we estimate that, in our experiment, a TIC increase of ~0.05% would have occurred after about 5 years, which we assume would be detectable (given the standard error on TIC ranged between 0.03 and 0.12). In reality, weathering was likely underestimated by the model (see below), and hence, TIC might become detectable earlier.

We used the 1D reactive transport model to estimate CO2 sequestration after 1 and 5 years. Predicted CO2 sequestration was 1.83 and 4.48 t CO2/ha sequestration after 1 and 5 years, respectively, which corresponds to about 13 and 35% of the maximum MC potential. Kelland et al. (2020) modeled a similar system that captured a similar 3 t CO2/ha despite applying twice as much (100 t/ha) basalt and columns were watered more intensely. This can be explained as in their simulation, net inorganic CO2 sequestration did not further increase after year one, when olivine and diopside were fully dissolved. In the model, the dissolution of Al-containing minerals diopside, plagioclases and basaltic glass were inhibited through precipitation of amorphous Al(OH)3, which was included as an equilibrium phase in the work of Kelland et al. (2020). As in Kelland et al. (2020), the latter mechanism inhibited dissolution of the Al-bearing labradorite (a Ca-plagioclase) also in our model simulations (Supplementary Figure SF8). Model assumptions are further discussed in Section 1.2 of Supplementary Material 1.

Comparison of pore water Mg revealed that the rate law parameters for weathering of the pyroxene mineral augite by Knauss et al. (1993) provide a better estimate than the parameters used by Palandri and Kharaka (2004) (Supplementary Figure SF2). Given the abundance of pyroxene minerals in basalt and mine tailings (Bullock et al., 2022), the latter is relevant for improving modeling CO2 sequestration of these rocks near neutral pH conditions. Still, a factor three difference in Mg in pore water remains with this rate law. This discrepancy between measured and modeled Mg concentration cannot result from overestimation of carbonate precipitation as the model did not predict precipitation of Mg-carbonates. Furthermore, only small changes of surface adsorbed Mg are simulated (Supplementary Table ST6). This suggests that the difference between measured and modeled Mg concentration in pore water is likely due to an underestimation of Mg mineral dissolution and/or an overestimation of Mg cation exchange. As PHREEQC is a geochemical model, the influence of biologically synthesized substances (e.g., siderophores, CAs, protons) is not taken into account. Biological substances can enhance weathering rates and may (partly) explain why the model underestimated the release of cations and hence weathering rates (Vicca et al., 2022). Moreover, also pore water Ca concentrations were underestimated by the model, indicating that the calcite precipitation rate (and hence degassing rate) was overestimated, leading to an underestimation of modeled CO2 sequestration.

To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to assess model predictions of CO2 sequestration through EW based on experimental pore water cation composition in real soils (Figure 6). Our study builds on the work of Kelland et al. (2020), who implemented this model, but did not compare experimental pore water data with simulated values. Additional research is needed to determine long-term weathering dynamics as well as to improve model simulations. Long-term studies are needed in which soil pore water chemistry is monitored. Our results demonstrate that in short-term EW-experiments with basalt, measurements of soil pore water chemistry are critical for monitoring weathering rates and for estimating CO2 sequestration. Future studies could consider specific elements (e.g., Ti, Al, and Na; depending on the mineral composition) that can provide insights in the weathering behavior of mineral phases containing these atoms. This would also allow verification of the modeled Al-silicate weathering inhibition by amorphous Al(OH)3.

A trade-off of utilizing fast-weathering ultramafic minerals for EW is Ni contamination; Ni leaching is expected to be smaller using mafic basalt rocks (which contain relatively little olivine) in alkaline soils where Ni precipitation is higher. Nonetheless, a comparison with EQSs is necessary for EW adoption in practice. Ni increased significantly in the soil and topsoil pore water. The addition of 50 t basalt/ha resulted in a topsoil (0–50 cm) Ni increase of 23 ppm, which is well below the Flemish threshold of 48 ppm for soil quality (VLAREBO, 2008). The pore water Ni concentration was increased with 2.5 μg/L. The EQSs for Ni in freshwater in the EU, Australia, the US and Canada, respectively, range from 4, over 8, 52, and 200 μg/L, respectively. Hence pore water Ni concentration remained below legislative freshwater thresholds of all of the above countries/regions. As Ni is associated with the fast weathering mineral olivine within basalt, we expect Ni in pore water to decrease over time. Information about initial soil Ni content and legal limits could provide a theoretical maximum on the amount of basalt that can be applied. In our experiment, the Flemish threshold would be reached after amendment with 104 t basalt/ha (if initial soil Ni equals zero). However, Ni would gradually leach out to surface waters, and might be taken up by plants, increasing the possible amount of application. Despite the increased Ni in soil and soil pore water, Ni concentrations in edible plant parts did not significantly increase with basalt amendment. This is in correspondance with results from Stasinos and Zabetakis (2013), who grew potatoes on soils irrigated with Ni-contaminated (0–250 μgNi/L) wastewater and found no increase in tuber Ni content. In fact, they even found tuber Ni concentration to decrease with increasing irrigation Ni levels.

In our experiment, basalt weathering increased Al availability, which induces Al toxicity and may reduce plant growth. Hence, during this experiment the alkaline catalyzed dissolution of Al by Ca plagioclase and Al-release by augite weathering was higher than the sum of Al precipitation and Al uptake. Dorneles et al. (2016) investigated Al toxicity in Solanum tuberosum and found that Si can ameliorate Al toxicity through formation of alumino silicate compounds in the walls of root cortex cells that inhibit uptake of Al into the protoplast. Hence, EW can influence Al toxicity in contrasting ways through release of Si and Al. In our alkaline soil, the weathering-induced increase in Al availability did not result in significantly higher potato tuber Al and Si stocks. Most importantly, the increased Al availability in the aqueous phase did not result in a decrease in tuber biomass, lifting concerns of reduced yield for EW with Solanum tuberosum in alkaline soils.

A risk that was not evaluated here concerns the potential health issues due to spreading fine silicate particles (Webb, 2020). To overcome this, basalt can be applied in a pelletized form to disintegrate again when applied in soils. Avoiding additional grinding of basalt quarry fines, which may not be warranted in terms of additional carbon sequestration gains (Lewis et al., 2021) can also reduce dust formation.

In our experiment with potatoes growing on alkaline soil, basalt amendment significantly increased soil CEC and Ca and Mg and tended to increase average potato tuber yield by 6%. This potato yield increase is lower than that in some studies on acid soil. Lafond and Simard (1999) amended an acid Canadian soil (low in Ca and K) with cement kiln dust (a silicate by-product from the cement industry) for growing Solanum tuberosum, which resulted in a tuber yield increases of over 50% at several locations. These yield gains were correlated with soil extractable K and Mg (Lafond and Simard, 1999). It is likely that potato tuber yield is increased more in agricultural systems where cations are more depleted than in our experimental soil. Still, positive trends in Ca, Mg, and K potato stocks were observed. The K decrease in the top soil of the basalt treatment presumably resulted from the high mobility of K and higher uptake by potato plants.

Interestingly, silicate amendment reduced potato harvest losses due to stem lodging and increased potato tuber yield in drought stress experiments (Crusciol et al., 2009). Silicate amendment may thus be even more attractive for potato cultivation in dry regions such as Africa or India (the third largest potato producing country globally) (FAO, 2008) and in future, when droughts increase in frequency and intensity with negative consequences for potato yield (Hijmans, 2003; IPCC, 2021).

Another co-benefit that we observed was the effect of basalt amendment on nitrogen leaching. Nitrogen leaching significantly decreased upon basalt amendment. In acid soils, the latter is hypothesized to result from pH increases. However, pH was buffered at 7.7 in both control and basalt amended soil. Hence, other mechanisms were likely at play in our experiment. Mechanistically, basalt amendment may have increased the trace element molybdenum (Mo) (which is present in rhyolite basalt in concentrations up to 4 ppm) (Arnórsson and Óskarsson, 2007). Soil and freshwater environments often contain Mo at concentrations that naturally limit denitrification. Mo is a cofactor of the enzyme nitrate reductase, which catalyzes the conversion of nitrate into nitrite (Vaccaro et al., 2016). Possibly, Mo released by basalt stimulated denitrifying microbial communities, but further research is needed to verify this.

Simulated CO2 sequestration was 0.77 t CO2/ha in the experimental timeframe (99 days) and 1.83 and 4.48 t CO2/ha after 1 and 5 years, respectively. This first study comparing experimental and modeled pore water chemistry in an EW mesocosm experiment indicated an underestimation of modeled CO2 sequestration, as simulated Ca and Mg pore water concentration were substantially lower than measured concentrations. Nonetheless, we did not detect a significant increase in TIC, probably because TIC increases were too small compared to soil heterogeneity. More detailed, long term assessments in future mesocosm and field experiments can help to further improve experimental and modeled estimates of CO2 sequestration through EW. As a co-benefit, nitrogen leaching significantly decreased with basalt addition, despite the fact that pH was not affected, suggesting that other processes were at play. In order to draw conclusions about the basalt effect on total soil nitrogen losses, future analyses should also consider gaseous N losses such as NH3 and N2O.

Plant Ni did not significantly increase, and increases in soil and pore water Ni were below allowed environmental quality standards. Importantly, in our alkaline soil, the weathering-induced risk of increased Al availability did not result in lower potato biomass. Despite the positive trends in Ca, Mg and K potato stocks, potato biomass was not significantly increased.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Raw data can be consulted at https://zenodo.org/record/6477990#.YmLAPNpBw2x.

SV designed the research. SI, SP, and SV conducted the experimental work. MP-E did the CN analysis. AV did the data analyses and PHREEQC modeling with help from PW and JH and AV drafted the paper. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and the writing of the paper, and contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO), and by the Research Council of the University of Antwerp.

PW was employed by (GLOBAL) Future Forest Company Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Sebastian Wieneke and Cristina Ariza Carricondo for help during the experimental setup.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2022.869456/full#supplementary-material

Amann, T., and Hartmann, J. (2019). Ideas and perspectives: synergies from co-deployment of negative emission technologies. Biogeosciences 16, 2949–2960. doi: 10.5194/bg-16-2949-2019

Amann, T., Hartmann, J., Struyf, E., De Oliveira Garcia, W., Fischer, E. K., Janssens, I., et al. (2020). Enhanced Weathering and related element fluxes - A cropland mesocosm approach. Biogeosciences 17, 103–119. doi: 10.5194/bg-17-103-2020

Arnórsson, S., and Óskarsson, N. (2007). Molybdenum and tungsten in volcanic rocks and in surface and <100 °C ground waters in Iceland. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 284–304. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2006.09.030

Bakken, L. R., Bergaust, L., Liu, B., and Frostegård, Å. (2012). Regulation of denitrification at the cellular level: a clue to the understanding of N2O emissions from soils. Philosop. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 367, 1226–1234. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0321

Beerling, D. J., Kantzas, E. P., Lomas, M. R., Wade, P., Eufrasio, R. M., Renforth, P., et al. (2020). Potential for large-scale CO2 removal via enhanced rock weathering with croplands. Nature 583, 242–248. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2448-9

Beerling, D. J., Leake, J. R., Long, S. P., Scholes, J. D., Ton, J., Nelson, P. N., et al. (2018). Farming with crops and rocks to address global climate, food and soil security /631/449 /706/1143 /704/47 /704/106 perspective. Nature Plants 4, 138–147. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0108-y

Blanc-Betes, E., Kantola, I. B., Gomez-Casanovas, N., Hartman, M. D., Parton, W. J., Lewis, A. L., et al. (2021). In silico assessment of the potential of basalt amendments to reduce N2O emissions from bioenergy crops. GCB Bioenergy 13, 224–241. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12757

Bose, H., and Satyanarayana, T. (2017). Microbial carbonic anhydrases in biomimetic carbon sequestration for mitigating global warming: prospects and perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1–20. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01615

Brantley, S. L., White, A. F., and Kubicki, J. D. (2008). Kinetics of Water-Rock Interaction. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73563-4

Brown, I. C. (1943). A rapid method of determining exchangeable hydrogen and total exchangeable bases of soils. Soil Sci. 56, 353–357. doi: 10.1097/00010694-194311000-00004

Bullock, L. A., Yang, A., and Darton, R. C. (2022). Kinetics-informed global assessment of mine tailings for CO2 removal. Sci. Total Environ. 808, 152111. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152111

Campos, H., and Ortiz, O. (2019). The potato crop: its agricultural, nutritional and social contribution to humankind. In: The Potato Crop: Its Agricultural, Nutritional and Social Contribution to Humankind. (Cham: Springer Nature), 518. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-28683-5

Crusciol, C. A. C., Pulz, A. L., Lemos, L. B., Soratto, R. P., and Lima, G. P. P. (2009). Effects of silicon and drought stress on tuber yield and leaf biochemical characteristics in potato. Crop Sci. 49, 949–954. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2008.04.0233

Demir, N., Demir, Y., and Coşkun, F. (2001). Purification and characterization of carbonic anhydrase from human erythrocyte plasma membrane. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 31, 477–482. doi: 10.1080/10826060008544944

Dietzen, C., Harrison, R., and Michelsen-Correa, S. (2018). Effectiveness of enhanced mineral weathering as a carbon sequestration tool and alternative to agricultural lime: an incubation experiment. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 74, 251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijggc.2018.05.007

Dorneles, A. O. S., Pereira, A. S., Rossato, L. V., Possebom, G., Sasso, V. M., Bernardy, K., et al. (2016). Silício reduz o conteúdo de alumínio em tecidos e ameniza seus efeitos tóxicos sobre o crescimento de plantas de batata. Ciencia Rural 46, 506–512. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20150585

FAO (2008). Potato World. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/potato-2008/en/world/index.html (accessed December 20, 2021).

FAOSTAT (2013). Food Balances 2010. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS (accessed March 16, 2022).

Fischer, G., Nachtergaele, F., Prieler, S., van Velthuizen, H. T., Verelst, L., and Wiberg, D. (2008). Global Agro-ecological Zones Assessment for Agriculture (GAEZ 2008). Rome: IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria and FAO.

Gasser, T., Guivarch, C., Tachiiri, K., Jones, C. D., and Ciais, P. (2015). Negative emissions physically needed to keep global warming below 2°C. Nat Commun. 6, 958. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8958

Gudbrandsson, S., Wolff-Boenisch, D., Gislason, S. R., and Oelkers, E. H. (2011). An experimental study of crystalline basalt dissolution from 2pH11 and temperatures from 5 to 75 °C. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 75, 5496–5509. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.06.035

Haque, F., Chiang, Y. W., and Santos, R. M. (2020a). Risk assessment of Ni, Cr, and Si release from alkaline minerals during enhanced weathering. Open Agric. 5, 166–175. doi: 10.1515/opag-2020-0016

Haque, F., Santos, R. M., and Chiang, Y. W. (2020b). CO2 sequestration by wollastonite-amended agricultural soils – An Ontario field study. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control (2019) 97:103017. doi: 10.1016/j.ijggc.2020.103017

Haque, F., Santos, R. M., Dutta, A., Thimmanagari, M., and Chiang, Y. W. (2019). Co-benefits of wollastonite weathering in agriculture: CO2 sequestration and promoted plant growth [research-article]. ACS Omega 4, 1425–1433. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b02477

Hartmann, J., West, A. J., Renforth, P., Köhler, P., De La Rocha, C. L., Wolf-Gladrow, D. A., et al. (2013). Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification. Rev. Geophys. 51, 113–149. doi: 10.1002/rog.20004

Hijmans, R. J. (2003). The effect of climate change on global potato production. Am. J. Potato Res. 80, 8–280. doi: 10.1007/BF02855363

IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (Cambridge University Press).

Kantola, I. B., Masters, M. D., Beerling, D. J., Long, S. P., and DeLucia, E. H. (2017). Potential of global croplands and bioenergy crops for climate change mitigation through deployment for enhanced weathering. Biol. Lett. 13, 20160714. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0714

Kelland, M. E., Wade, P. W., Lewis, A. L., Taylor, L. L., Sarkar, B., Andrews, M. G., et al. (2020). Increased yield and CO2 sequestration potential with the C4 cereal Sorghum bicolor cultivated in basaltic rock dust-amended agricultural soil. Global Change Biol. 26, 3658–3676. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15089

Knauss, K. G., Nguyen, S. N., and Weed, H. C. (1993). Diopside dissolution kinetics as a function of pH, CO2, temperature, and time. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 285–294. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(93)90431-U

Lafond, J., and Simard, R. R. (1999). Effects of cement kiln dust on soil and potato crop quality. Am. J. Potato Res. 76, 83–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02855204

Lawlor, E. T. S. L. A. (1998). Modelling the Chemical Speciation of Trace Metals in the Surface Waters of the Humber System.

Lewis, A. L., Sarkar, B., Wade, P., Kemp, S. J., Hodson, M. E., Taylor, L. L., et al. (2021). Effects of mineralogy, chemistry and physical properties of basalts on carbon capture potential and plant-nutrient element release via enhanced weathering. Appl. Geochem. 132, 105023. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2021.105023

Manning, D. A. C., Renforth, P., Lopez-Capel, E., Robertson, S., and Ghazireh, N. (2013). Carbonate precipitation in artificial soils produced from basaltic quarry fines and composts: an opportunity for passive carbon sequestration. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 17, 309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijggc.2013.05.012

Palandri, J. L., and Kharaka, Y. K. (2004). A compilation of rate parameters of water-mineral interaction kinetics for application to geochemical modeling. USGS Open File Report 2004–1068, 71. doi: 10.3133/ofr20041068

Parkhurst, D. L., and Appelo, C. A. J. (2013). “Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3—A Computer Program for Speciation, Batch-Reaction, One-Dimensional Transport, and Inverse Geochemical Calculations,” in U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods. (Denver, Colorado), Book 6, Chapter A43, 497 p. 6–43A. Available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/06/a43/

Qian, P., and Schoenau, J. J. (2002). Practical applications of ion exchange resins in agricultural and environmental soil research. Canadian Journal of Soil Science. 82(1), 9–21.

Qu, Z., Wang, J., Almøy, T., and Bakken, L. R. (2014). Excessive use of nitrogen in Chinese agriculture results in high N2O/(N2O+N2) product ratio of denitrification, primarily due to acidification of the soils. Global Change Biol. 20, 1685–1698. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12461

Renforth, P. (2019). The negative emission potential of alkaline materials_Supplementary information. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09475-5

Roland, M., Vicca, S., Bahn, M., Ladreiter-Knauss, T., Schmitt, M., and Janssens, I. A. (2015). Importance of nondiffusive transport for soil CO2 efflux in a temperate mountain grassland. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 120, 502–512. doi: 10.1002/2014JG002788

Roser, M., and Ritchie, H. (2020). CO2 Emissions. Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions (accessed April 23, 2021).

Sathya, V., and Mahimairaja, S. (2015). Adsorption of nickel on vertisol: effect of pH of soil organic matter and co-contaminants. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 19, 1–8. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340933868_Adsorption_of_Nickel_on_Vertisol_Effect_of_pH_of_soil_Organic_Matter_and_Co-contaminants

Schuiling, R. D., and Krijgsman, P. (2006). Enhanced weathering: an effective and cheap tool to sequester CO2. Clim. Change 74, 349–54. doi: 10.1007/s10584-005-3485-y

Stasinos, S., and Zabetakis, I. (2013). The uptake of nickel and chromium from irrigation water by potatoes, carrots and onions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 91, 122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.01.023

Strefler, J., Amann, T., Bauer, N., Kriegler, E., and Hartmann, J. (2018). Potential and costs of carbon dioxide removal by enhanced weathering of rocks. Environ. Res. Letters 13:034010. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaa9c4

ten Berge, H. F. M., van der Meer, H. G., Steenhuizen, J. W., Goedhart, P. W., Knops, P., and Verhagen, J. (2012). Olivine weathering in soil, and its effects on growth and nutrient uptake in ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.): a pot experiment. PLoS ONE 7, e004298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042098

Vaccaro, B. J., Thorgersen, M. P., Lancaster, W. A., Price, M. N., Wetmore, K. M., Poole, F. L., et al. (2016). Determining roles of accessory genes in denitrification by mutant fitness analyses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 51–61. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02602-15

Vicca, S., Goll, D., Hagens, M., Hartmann, J., Janssens, I. A., Neubeck, A., et al. (2022). Is the climate change mitigation effect of enhanced silicate weathering governed by biological processes? Global Change Biol. 28, 711–26. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15993

VLAREBO (2008). VLAREBO 2008 14 DECEMBER 2007 - Besluit van de Vlaamse Regering houdende vaststelling van het Vlaams reglement betreffende de bodemsanering en de bodembescherming. 1–115. Available online at: https://navigator.emis.vito.be/mijn-navigator?woId=23569andwoLang=nl (accessed November 13, 2021).

Walinga, I., van Vark, W., Houba, V. J. G., and van der Lee, J. J. (1989). Plant Analysis Procedures. Soil and Plant Analysis, Part 7. Wageningen: Agricultural University, p. 13–16.

Webb, R. M. (2020). The Law of Enhanced Weathering for Carbon Dioxide Removal. New York: Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Columbia Law School. Available online at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3698944 (accessed September 22, 2020).

Keywords: enhanced weathering, basalt, carbon sequestration, DIC, TIC, nitrate, nickel, PHREEQC

Citation: Vienne A, Poblador S, Portillo-Estrada M, Hartmann J, Ijiehon S, Wade P and Vicca S (2022) Enhanced Weathering Using Basalt Rock Powder: Carbon Sequestration, Co-benefits and Risks in a Mesocosm Study With Solanum tuberosum. Front. Clim. 4:869456. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2022.869456

Received: 04 February 2022; Accepted: 04 April 2022;

Published: 17 May 2022.

Edited by:

Ben W. Kolosz, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesReviewed by:

Rafael Mattos Dos Santos, University of Guelph, CanadaCopyright © 2022 Vienne, Poblador, Portillo-Estrada, Hartmann, Ijiehon, Wade and Vicca. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arthur Vienne, YXJ0aHVyLnZpZW5uZUB1YW50d2VycGVuLmJl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.