- 1Pentland Centre for Sustainability in Business, Lancaster University, Lancaster, United Kingdom

- 2Scottish Government, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

In facing up to the reality of the climate crisis and the risks it poses, people encounter powerful emotions that can be difficult to bear. Consequently, various defences and coping strategies may be used to suppress or avoid feeling these emotions. The way in which emotions are regulated has important implications for wellbeing and decision-making. In recent years there has been growing interest in using citizens' assemblies to inform government climate policy. Assembly members learn about and discuss the subject, and produce recommendations for action. Given this element of learning about climate change, it is likely that difficult emotions will come up for assembly members. This paper investigates the emotional experience of members of Scotland's Climate Assembly to explore which, if any, emotions are experienced and how they are regulated. The findings are compared to a population survey, and discussed in relation to the assembly process including the evidence presented to members, and the assembly outputs. Assembly members appear to have had quite a different emotional experience compared to the general population, with higher levels of hopefulness and optimism, lower levels of worry and overwhelm, and a lower proportion reporting that their emotions about climate change were having a negative impact on their mental health. It is proposed that these differences in experience may in part be due to a focussed sense of purpose and agency that being an assembly member brings, along with exposure to evidence that may have underplayed the severity of the climate crisis and that was framed in ways that reassured the members that climate change can be tackled in an effective and fair way. However, after receiving the Scottish Government response to their recommendations, there are indications that levels of optimism and hopefulness dropped and levels of worry increased, with members expressing overall disappointment with the response. The findings enhance our understanding of how people perceive climate risk and how they experience that emotionally, and can be used to inform the design of future deliberative processes, and for supporting people to regulate their emotions about climate change and climate policy in an adaptive way.

Introduction

Climate Psychology and Emotions About Climate Change

Within the field of climate psychology, the climate crisis is understood to pose profound threat in a variety of ways including threat to life and sense of safety, to life plans and expectations about the future, to who we think we are as individuals and as a society, and threat to our sense of worth by challenging the morality of our destructive behaviours (American Psychological Association, 2009; Crompton and Kasser, 2009; Reser and Swim, 2011).

Perceptions of climate threat create stress, including pre-traumatic stress (Kaplan, 2020). The normal human tendency is to attempt to alleviate stress and reduce associated emotions through a variety of defences and coping strategies (Cramer, 1998). This is because prolonged toxic stress can create major health problems including exhaustion and illness, ultimately leading to death. Threat responses have outcomes that can be adaptive or maladaptive on a personal and/or ecological level, depending on the context and the extent to which the defence or coping strategy is used over time (Cramer, 1998). Adaptive coping helps to acknowledge and adjust to the reality of the situation, overcome the stress associated with it, and take direct action to deal with the situation. Examples are seeking information, engaging with and regulating emotions, and collaborative problem solving. Maladaptive coping, on the other hand, inhibits our ability to deal with the reality of the situation and to take appropriate and proportional actions. Examples are denial and distortion of facts, emotional avoidance or suppression, wishful thinking or unrealistic optimism, and self-enhancement (Crompton and Kasser, 2009; Weinstein et al., 2009; Andrews and Hoggett, 2019).

As a person learns about the reality of the climate crisis and the severity of its current, anticipated and potential impacts, it likely that this information will be perceived (consciously or unconsciously) as threatening, creating stress and triggering emotions such as anxiety, fear, worry, sadness, grief, despair, anger, shame, or guilt (Hoggett and Randall, 2018). In this paper, such emotions are collectively referred to as “climate distress” following other climate psychology studies (Randall, 2019; Lawrance et al., 2021; Marks et al., 2021). Anxiety and other distressing or disturbing emotions are often termed “negative” emotions. However, whilst such emotions may be painful and difficult to bear, they are not in themselves “bad.” Emotions are cues and therefore produce knowledge, serving a vital function in self-regulation, directing attention and guiding behaviour (Brown and Ryan, 2003; Deci et al., 2015).

Narratives around climate science often categorise conclusions as either “doom” or “positive” (Chapman et al., 2017; Graves, 2018). This binary is not just false but unhelpful because it simplifies the nuanced and conflicted nature of human experience, and discourages engagement with the “negative” thoughts and feelings that naturally arise when we confront the implications of climate science data. There is a belief that telling truths will lead people to get stuck in despair, resignation and inaction (e.g., Mann et al., 2017). However, the evidence supporting this position is thin and more research is needed to understand the impacts of different framings (Chapman et al., 2017; Roberts, 2017).

Experiencing climate distress can be interpreted as a positive sign that the person is in touch with the reality of the climate crisis, which is needed for motivating appropriate responses (Rust, 2008; Macy and Brown, 2014; Clayton, 2020). Indeed, such emotions have been described as a “rational” response (e.g., Verplanken and Roy, 2013; Marks et al., 2021). The key issue is not so much which particular distressing emotions are experienced, as people may experience a mix of these emotions at the same time or fluctuating over time (Pikhala, 2020), but how the emotions are regulated over the longer term—whether suppressed, avoided or otherwise dysregulated (maladaptive coping), or contained, engaged with and worked through (adaptive coping). A distinction can therefore be been made between anxiety and worry that is constructive and part of an adaptive coping response, which has been found to be associated with pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours (Verplanken and Roy, 2013), and anxiety and worry that is pathological, and which could lead to or exacerbate mental health problems. It is already well-established that the way in which emotions are regulated has implications for wellbeing, decision-making and to our ability to retain and act on information (Rogelberg, 2006; Brown and Cordon, 2009; Ray, 2010).

There have been several population surveys in the UK on climate anxiety in recent years. Whilst the questions vary, the results indicate that a large proportion of the public feel worried or anxious about climate change. For example, one survey in 2019 with 2000 adults found 34% felt anxious because of climate change (Triodos, 2019). Another survey in 2020 with 1,000 adults found 73% reported moderate, high or very high levels of stress/anxiety (Truverra, 2020), and one with 5,527 adults in 2020 found 55% felt climate change had impacted on their wellbeing to some degree (BACP, 2020). A survey with 1,667 UK adults in 2021 found 68% of the UK population fairly or very worried about climate change and its effects (YouGov, 2021). Other surveys with children and young people also find a large majority are worried (BBC Newsround, 2020; Marks et al., 2021).

There is a growing body of literature on the impacts of climate change on mental health, particularly in relation to extreme weather events. For example, the journal Nature Climate Change featured a special issue on mental health in 2018. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on 1.5 degrees only covered morbidity and mortality and not mental health (IPCC, 2018), but the final draught Sixth Assessment Report on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability includes for the first time a section on mental health and wellbeing, including discussion of emotions such as anxiety and grief (IPCC, 2022).

Despite progress in this area, research specifically on climate emotions is nascent, and there are few empirical studies into the factors that contribute to such feelings in particular contexts, how emotions may change over time or by context, or how emotions are regulated. Understanding these dimensions is important for therapeutic practitioners and organisations, and policy makers, for developing context-specific interventions and resources that support people to regulate their emotions about climate change in an adaptive way.

This paper contributes to this new field of research on climate emotions with an initial attempt to investigate the emotional experience of members of a citizens' assembly on climate change in Scotland. Whilst there have been several national citizens' assemblies on climate change, which have or are in the process of being researched and evaluated (e.g., see https://knoca.eu) there has been no other research to date that has looked at climate emotions in the particular context of a citizens' assembly. The research presented in this paper sought to answer the following research questions:

• What is the emotional experience of assembly members as they learn about climate change?

• How does that compare with the general population?

• Are members' emotional experiences influenced by contextual factors?

The data was collected as part of a wider research programme to: support continuous improvement in the design and delivery of the assembly whilst it was in process; evaluate the success of the assembly as a deliberative process; assess support for the assembly and its recommendations by the assembly members and the general public; assess the impact of the assembly on climate policy and debate in Scotland, and to identify key outcomes for members—including psycho-social outcomes and emotional experience (Andrews et al., 2022). The findings relating to the members' emotional experience were used to inform wellbeing resources and support whilst the Assembly was in process thus aiding the organisers in meeting their duty of care obligations, and contributing to meeting the research objective of supporting continuous improvement.

Contextual factors discussed in this paper include the assembly process and the evidence presented to members.

As there is no published literature on this specific topic to date, this paper presents original research that can support organisers of future climate assemblies or other deliberative processes in ensuring that members' emotional wellbeing is considered as part of their duty of care. The findings can also be used by climate policy makers to inform their public engagement strategies. In enhancing our understanding of contextual factors that may affect a person's perception of climate risk and their emotional wellbeing, the findings may also be of practical use to the therapeutic community and health and wellbeing practitioners in supporting people to regulate their emotions about climate change and climate policy in an adaptive way. Finally, the findings contribute to our understanding of the affective dimensions of climate risk, as they provide insight into the meaning that people make of the risk that climate change poses, how they experience that emotionally, and how emotional experiences change, in the situated context of a deliberative democratic process involving dialogue between government and members of the public.

Scotland's Climate Assembly

Some background information on citizens' assemblies in general and Scotland's Climate Assembly specifically is now provided.

Citizens' assemblies bring together a group of individuals (referred to as members) through random and stratified selection to broadly represent the wider population with respect to key demographics. The assembly is tasked with deliberating on information provided by experts (referred to as “evidence”) and produces of a set of recommendations with the aim to inform policy and decision-making (Curato et al., 2021). Deliberation refers to the consideration of a range of perspectives in an inclusive, reasoned and respectful manner (Andrews et al., 2022).

The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 required Scottish Ministers to establish a citizens' assembly on climate change.1 The Assembly met online over seven weekends from November 2020 to March 2021, and was tasked with addressing the question “How should Scotland change to tackle the climate emergency in an effective and fair way?” The 105 members were presented with evidence from experts, which they discussed in facilitated small groups. Over the course of the sessions, they developed their proposals and finalised their recommendations for change. The assembly report, which was laid before the Scottish Parliament on 23 June 2021 contains the outputs of the assembly process: a statement of ambition, 16 goals and 81 associated policy recommendations with supporting statements.2 The Scottish Government, as required by the Climate Change Act, produced a response to the assembly recommendations. This response was published on 16 December 2021.3 The assembly then met for a final eighth weekend in February 2022 to discuss the government response and to produce their own Statement of Response back.

In Weekend 2, members viewed a video presentation on climate anxiety. Forty-six percentage of respondents to the survey following Weekend 2 reported that they found the video helpful. There were no sessions that explicitly invited members to talk about their feelings about climate change and the evidence presented to them.

Materials and Methods

This study took a mixed methods approach to investigate the emotional experience of Assembly members, integrating several data sources: member surveys, audio recordings of small group sessions, evidence presentations and the Assembly report.

Member Survey

Assembly members were asked to complete an online survey using Questback software after each weekend. These surveys covered a range of topics (e.g., satisfaction with Assembly organisation, support, communication, and facilitation; views on evidence presented; knowledge and learning about climate change) and were designed as part of a wider research programme on the Assembly, as explained earlier.

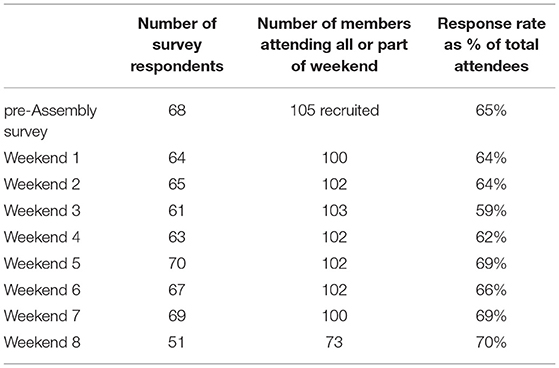

Across the weekends, around two thirds of the 105 members recruited to the Assembly completed the survey (see Table 1). The findings should be therefore be interpreted as being indicative of the experience of all members, not as a full reflection of the views of all members.

Seven statements relating to emotional experience were included in the Weekend 2–8 surveys4:

• I am feeling excited/hopeful about what we can do to tackle climate

• I am feeling worried/upset by what I am learning about climate change

• I am feeling overwhelmed by the information on climate change that is being presented

• I feel optimistic that things will work out fine in relation to climate change

• I push emotions away so I do not feel distressed about climate change

• My feelings about climate change are having a negative impact on my mental health

• I am not aware of feeling any negative or distressing emotions about climate change

Response options were: strongly agree, tend to agree, neither agree nor disagree, tend to disagree, strongly disagree, and do not know.

These questions were chosen to reflect common climate emotions (hopeful, excited, optimistic, worried, upset, upset, overwhelmed) and to gain some insight into emotion regulation and impact on mental health. As the questions were part of a wider study, only a small number of questions could be included to keep the survey length within around 20 min response time. The questions were validated by checking with climate psychology experts from the Climate Psychology Alliance,5 who were not involved with the study, that these questions could effectively capture the topic under investigation. Data from Questback was exported as Excel and SPSS files. Members were assigned IDs and the data cleaned (duplicate entries removed) and anonymised. Quantitative data was analysed using SPSS 24 descriptive statistics. Due to the small sample sizes, breakdown of results by group has been treated with caution.

The surveys also included a small number of open questions, for example:

• Do you have any comments about your ability to participate in the Assembly this weekend?

• Do you have any comments about your experience with your facilitator this weekend/across the Assembly weekends?

• What have you learned this weekend that really stood out for you?

• Do you have any comments about the psychological or emotional impact of participating in the Assembly?

• Are there any other comments you'd like to make about your experience of participating this weekend?

For most of these questions only a small proportion of respondents provided answers. In this paper, quotes from this qualitative data have been included for illustrative purposes and to provide nuance and insight into the quantitative results.

Small Group Sessions

Assembly members were split into small groups of around seven people, across a mix of age groups and genders. Each group was led by one facilitator. The purpose of the groups was to deliberate upon the evidence provided, and to develop and finalise their recommendations for policy action. For Weekends 3–5, the groups were separated into three topic streams: Diet, Lifestyle, and Land use; Homes and Communities; and Work and Travel, reflecting key areas for reducing carbon emissions. Members remained in these streams for the duration, before coming together in mixed stream groups for Weekends 6 and 7.

Across the seven weekends of the main Assembly period, 48 small group sessions were audio recorded and transcribed to intelligent verbatim standard6 by an external company. A sample of 26 sessions totalling 23 h and 38 min were analysed for use of emotional language. The sample is spread across the small groups and weekends, however it is not fully representative in all respects and should be regarded as indicative only.

Emotional expressions were clustered into two groups:

• climate change, current, and proposed measures for tackling it

• the Assembly process.

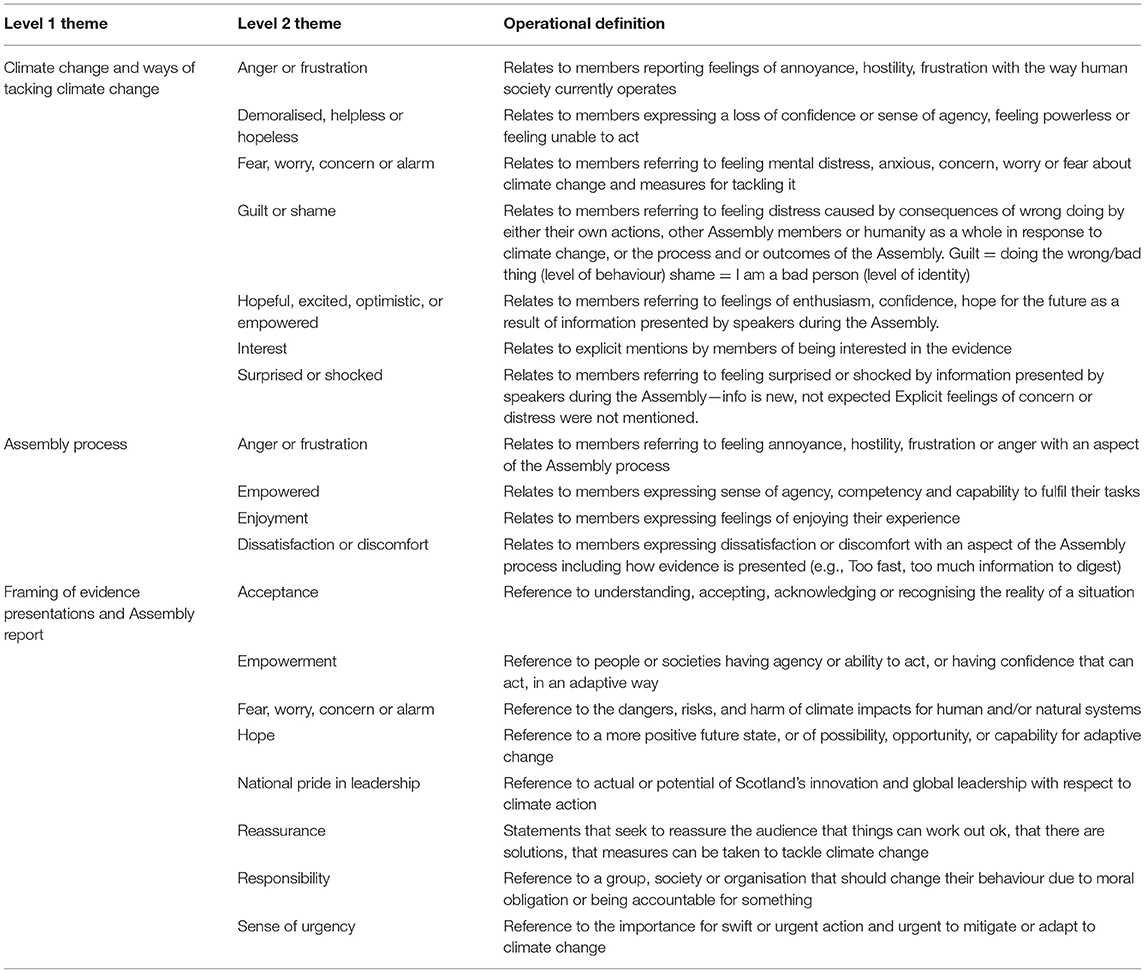

The data was analysed thematically using NVivo 1.4(4). Table 2 outlines the coding framework that was developed together with operational definitions used in coding. Data was coded into emerging themes, and then clustered into higher order themes, in an iterative process to cheque that coding was consistent across the sample.

Evidence Presentations

Assembly members watched video presentations about climate change by the Evidence Group and other experts, referred to in the Assembly as “informants,” whose role was to provide “objective” information. There were also some presentations by “advocates” who were mostly from third sector environmental organisations and offered their opinions and proposals for change. There were also some presentations giving examples of community climate action. The Assembly website contains links to the video presentations with transcripts publicly available to download for the majority of these presentations.7 The videos and plenary sessions are also available on YouTube.8 These presentations were referred to as “evidence” in the Assembly, as they contained information and research data for the members to deliberate.

Presentations covered a range of topics. Some aimed to help members in their learning generally for example with presentations on how to approach evidence, thinking about change, how change happens, and different levels of action. Most were on topics directly related to climate change, including introductory presentations on what tackling climate change means, what factors need to be considered, where emissions come from, how and why we set climate targets, and what is fair; as well as presentations providing evidence on the topic streams and on mitigation and adaptation. Members were provided with some information on impacts as part of the introduction to climate change, but not in-depth on global or Scotland-specific impacts. In Weekend 2, members viewed a presentation on climate anxiety. Presentations varied in length between 5 and 15 min.

A sample of 63 presentations was selected for analysis out of a total of 102 presentations that (a) directly related to climate change, and (b) had publicly available transcripts. The transcripts were coded by presenter type (Evidence Group member, informant or advocate), presenter gender, topic of presentation (mitigation, adaptation, topic streams), and weekend (Weekend 7 did not have any evidence presentations). A stratified random sampling method was then used to ensure a mix across these features, broadly reflecting the total.

This data source was included to address the research question on the influence of contextual factors, as the members' emotional experiences were likely to have been influenced by the framing of the evidence that they engaged with (Nisbet, 2009; Lakoff, 2010; Shaw et al., 2021).

The transcripts were analysed thematically for their emotional content and framing using NVivo 1.4(4), using the coding framework outlined in Table 2.

Assembly Report

The Assembly is tasked with producing a report of their recommendations for policy action. As an expression of members' views, the report was included as a data source. The report included 10 statements of ambition, 16 goals, and 81 recommendations with supporting statements. These were analysed thematically using NVivo 1.4(4), using the coding framework outlined in Table 2.

Population Survey

A survey with a sample of 1,917 adults (aged 16 and over) in Scotland was conducted by market research company Deltapoll. This included 1,650 online surveys and 250 telephone surveys with non-internet users. Online participants were recruited via the Dynata panel with 75,000 panel members in Scotland. An active sampling technique was used to recruit panellists, with potential participants selected using random start, fixed interval techniques to generate enough invites (combined with expected response rates—typically 50%) to meet the desired sample size. Online participants received points for completing the survey, which could be converted into a financial incentive. The telephone survey used random digit dial techniques and no incentives were offered. Under the quasi-random sampling method, Deltapoll used a two-stage method to ensure a representative sample. The first involved setting quotas by age, gender, ethnicity and geography. The second stage was weighting the data to Census 2011 data to correct for under or over-achieved quotas.

The survey was commissioned as part of the wider research programme on Scotland's Climate Assembly. The survey took place after the Assembly report was published, from 29 July to 14 August 2021.

The survey included the same closed climate emotions questions as the member survey:

• I am feeling worried/upset by what I am learning about climate change

• I feel optimistic that things will work out fine in relation to climate change

• I push emotions away so I do not feel distressed about climate change

• My feelings about climate change are having a negative impact on my mental health

• I am not aware of feeling any negative or distressing emotions about climate change.

There were small adjustments in phrasing to the remaining two questions to fit the different context:

• I am feeling excited/hopeful about what Scotland can do to tackle climate change

• I am feeling overwhelmed by what I am finding out about climate change.

The data was analysed using SPSS 24 descriptive statistics (frequency, crosstab). The data is correct to within ±2.2% at the 95% confidence interval.

Results

Member Survey

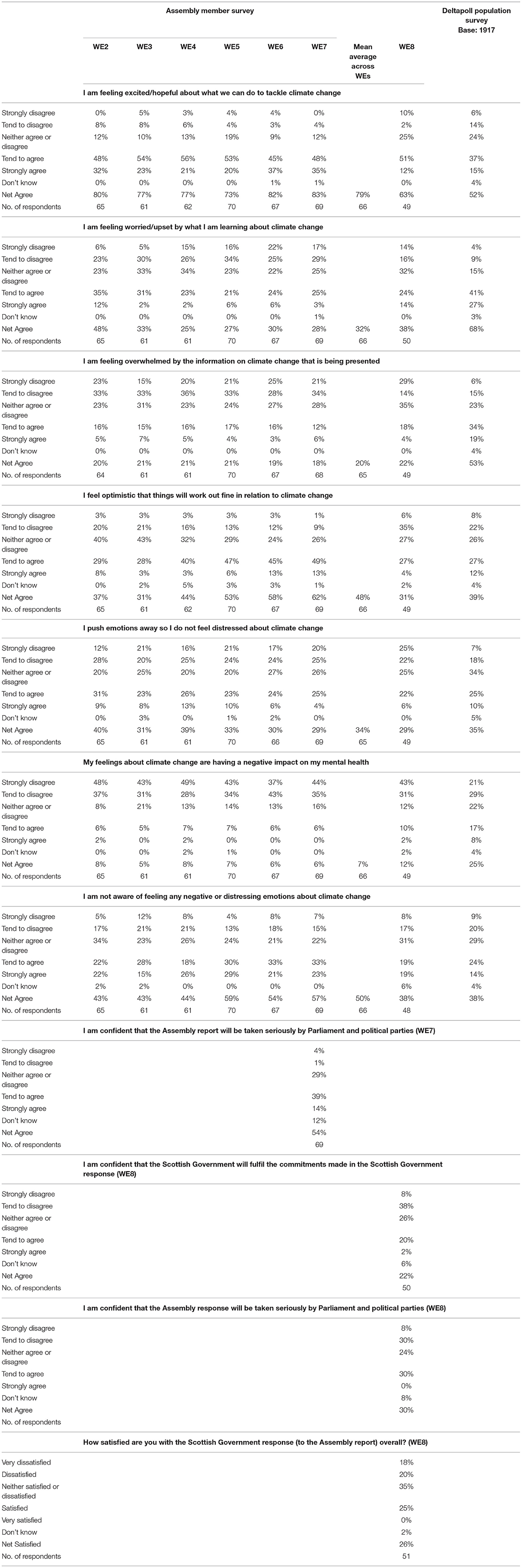

Table 3 shows the results for each weekend survey, as well as the mean percentage across the main Assembly period (Weekends 2–7) of respondents who “tended to agree” or “strongly agreed” with the emotion statements. Other relevant data has also been included.

Summary of Key Findings

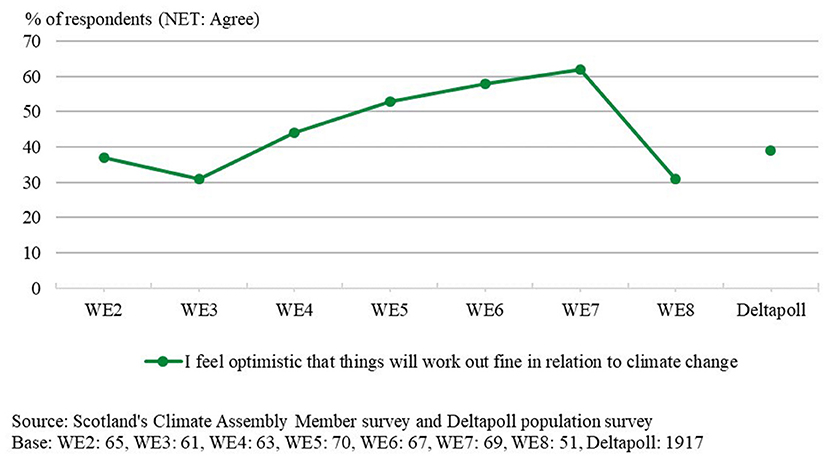

Whilst the proportion of respondents feeling excitement/hopefulness and overwhelm fluctuated slightly over the main Assembly weekends, the proportion feeling “optimistic that things will work out fine in relation to climate change” increased, ending on a high after Weekend 7 with twice as many as the lowest point after Weekend 3. Conversely, the proportion of respondents feeling of worry or upset declined after Weekend 2.

The quotes below describe two different emotional journeys, the first quote following the general trend from worry to excitement, and the second quote going the opposite direction:

“There were moments that it was quite demoralising thinking there is no way we can change but as the weeks progressed, more evidence and a wee bit of research turned a worry into excitement of what will happen next.” (Assembly member, WE7)

“It's been a bit of a rollercoaster. I found the Assembly to be such a positive group - everyone including the organisers, the conveners, the other Assembly members, that at the start it was really exciting to be taking part and I would finish the weekend on a real high. However, as time progressed and we heard more and more presentations, and I gathered more information from websites and BBC programmes, I started to feel a bit overwhelmed and less positive. I'm not sure if I would say that it has impacted on my mental health directly, but it has really affected my sleep pattern. I am often awake in the night thinking about climate change.” (Assembly member, WE7)

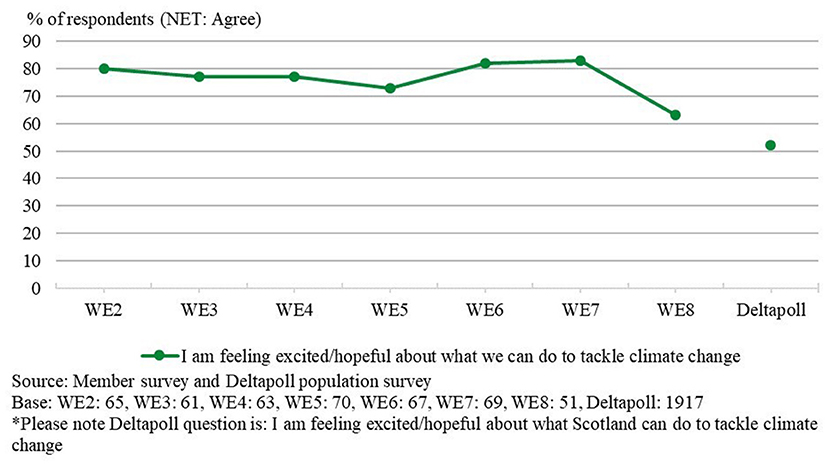

Comparing results of the member survey with the Deltapoll population survey suggests that the overall emotional experience of Assembly members' was quite different to that of the general Scottish public, which indicates that the Assembly context is an influencing factor.

Results

As shown in Figure 1, respondents to the member surveys in the main Assembly period had much higher levels of excitement/hopefulness throughout the Assembly: a mean average of around eight in 10 members (79%), compared to five in 10 of the general Scottish public (52%).

Figure 2 shows that members' optimism after Weekend 2 was similar to the general Scottish public (37 and 39%, respectively) but increased much higher as the Assembly progressed (to 62% after Weekend 6). Analysis of the Deltapoll survey data shows that those earning more than £5200 a month were more likely to agree (52%) than those earning <£1800 (36%), and those who thought climate change was a future problem or not really a problem (50%) more likely to agree than those who thought climate change is an immediate and urgent problem (39%).

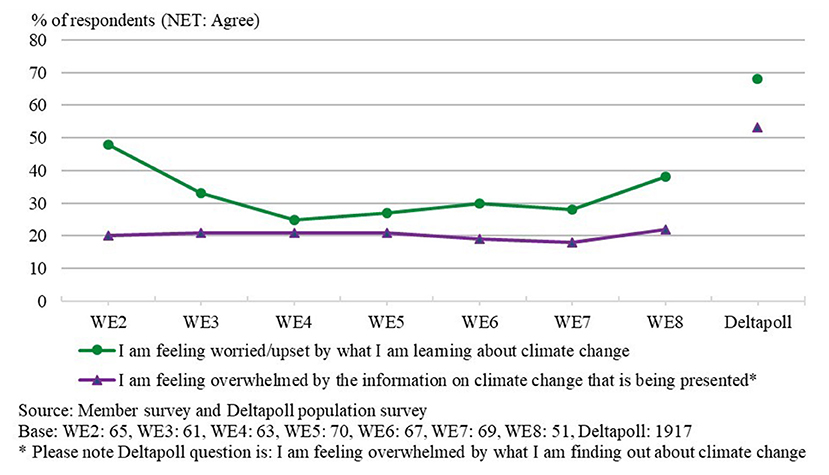

Members' levels of worry over the course of the main Assembly period reduced from 48% after Weekend 2–28% after Weekend 6, compared with 68% of the general Scottish public, as shown in Figure 3. A UK survey conducted around the same time found 68% of the UK population fairly or very worried about climate change and its effects, with 72% of the Scottish sample giving this response (YouGov, 2021). Both the Deltapoll and YouGov surveys found that females were slightly more likely than males to feel worried (Deltapoll: 71% females, 63% males; YouGov: 71% females, 64% males). Whilst the member survey data does not show any links between worry and climate attitudes, the Deltapoll population survey data finds that those who think climate change is an “immediate and urgent problem” are more likely to be worried (78%) than those who think it is a “future problem” (52%), and those who are concerned are more likely (76%) than those who are unconcerned (21%). The sample sizes for other categories of climate attitudes are too small for analysis.

As shown in Figure 3, around one in five respondents agreed that they felt “overwhelmed by the information on climate change that is being presented.” The proportion remained fairly constant throughout (mean average 20%), with many of the same respondents giving this response across the weekends. In the Deltapoll population survey, 53% agreed that they felt “overwhelmed by what I am finding out about climate change.” Several respondents commented on feeling overwhelmed by the volume of evidence and the limited amount of time to digest it and to discuss it in their small groups. Comments included:

“The only negatives I can think of are that I did at times feel overwhelmed and lost with the sheer amount of information / tasks and that being terrified of speaking in front of groups I did not participate as much as I would have liked to.” (Assembly member WE7)

“We've been given such a lot of information, in a very short space of time … The amount that has been presented to us has been quite overwhelming. I like to take a step back, I don't like to feel rushed.” (Assembly member WE6)

In the population survey, a higher proportion of those who voted for Scottish Green Party felt overwhelmed (64%) than those who voted for Scottish Conservatives in the May 2021 Scottish Parliament elections (38%), and a higher proportion of those with long-term health conditions (63%) felt overwhelmed than those without (49%).

The analysis did not find any pattern in the Weekends 2–7 member survey data between worry and overwhelm. However, in the population survey 89% of those who felt overwhelmed also felt worried or upset. The opposite was true though to a lesser extent, with 67% of those who felt worried/upset also feeling overwhelmed. Eight hundred and fifty four out of 1,917 respondents (45%) felt both worried and overwhelmed.

Each weekend in the main Assembly period, three to five respondents “tended to agree” or “strongly agree” (net agree mean of 7% of respondents across the surveys) that their feelings about climate change were having a negative impact on their mental health. Six respondents gave this response in one survey only, and five gave this response in more than one survey. These 11 respondents were a mix of genders (five women, four men, two defined their gender in another way), across all age groups and net income bands, with around half reporting a long term limiting physical or mental health condition. There was no clear overall pattern of response of this group to the other climate emotion questions, with some agreeing and some disagreeing that they felt excited/hopeful or worried/upset. One of the respondents who reported negative impact commented:

“It's had a big impact psychologically as I am more aware the impact of day to day activities had on the environment. It's hard to know that if we don't make changes then we may struggle to survive. It's also positive though that a lot of people are becoming more aware of the issue and that the reason the Assembly was put together was to try to contact this. I'm hopeful that things change.” (Assembly member, WE7)

The population survey finds that 25% of the general Scottish public agree that their feelings about climate change are having a negative impact on their mental health, which is considerably higher than the member survey. People below 45 years old were more likely to agree (up to 43%) than those who were older (up to 16%), as were those with a long term physical or mental health condition (37%) than without (21%), and those voted for Scottish Green Party in the May 2021 Scottish Parliament elections (46%) than other parties (up to 33%). The population survey results were also analysed by climate attitudes: a third of those who think climate change is a “problem for the future” and a fifth of those who think it is “not really a problem at all”9 agree that their feelings about climate change are having a negative impact on their mental health.

As shown in Figure 4, across the weekends in the main Assembly period, around a third of respondents appeared to use emotional avoidance or suppression coping strategies (mean average of 34% agree “I push emotions away so I do not feel distressed about climate change”), whilst half the respondents agreed that they had no awareness of feeling distressing emotions (mean average of 50% agree). This compares with 35 and 38% in the Deltapoll population survey, respectively. One respondent in the Weekend 7 survey who “tended to agree” that they pushed emotions away so as not to feel distressed, and also “tended to agree” that they were not aware of feeling negative or distressing emotions about climate change, commented:

“I have been aware about Climate Change for many decades, having seen the vandalism, through ignorance or vested interest, of large organisations and national bodies. Any impact was felt a long time ago.” (Assembly member, WE7)

This comment suggests a defence of numbing.

Some members also expressed frustration in their comments. The following examples are about the Assembly itself and factors affecting their participation:

“The time allocated to review the goals/recommendations from the previous week wasn't enough and we had to rush which was frustrating and I don't think it serves its purpose.” (Assembly member WE4)

“I've struggled at times during this process. As a victim of technological obsolescence I found my inability to download anything due to not having the latest version of software greatly impacted my ability to participate in the proceedings. The level of frustration this caused me was unlike anything I've experienced before. Perhaps 3 months of isolation compounded this emotional response.” (Assembly member WE7)

The following comments highlight the complexity of experience, and convey the value attached to personal development and learning:

“At times, stressful, at times confusing and at times frustrating. However also informative, participatory, well run over all, developmental and at times fun. A worthy Assembly to be a part of, both for the future of Scotland, and for my own education on urgent matters.” (Assembly Member, WE7)

“I have loved and loathed the process. I have felt challenged both mentally and emotionally. I have learnt so much about myself in the process. I have a valid point of view. I have life experience that has given me perspective on all the challenges we face. I feel shattered and exhilarated at the same time that I have been a part of this journey. I have met and shared ideas with the most diverse group of people. And I have loved the fact that I still have the capacity to learn. And I am grateful that I was chosen.” (Assembly member WE7)

Quantitative member survey data also reveals that many members were feeling mixed emotions. For example, in the Weekend 2 survey, 24 of the 31 respondents (77%) who agreed that they were feeling worried or upset also agreed that they felt excited or hopeful about what Scotland can do to tackle climate change.

Mixed emotions were also a feature of the population survey, with 831 of the 1,274 who agreed feeling worried or upset also reporting feeling excited or hopeful (65%). Forty three percentage of all respondents were both worried/upset and excited/hopeful.

Examples of comments in the member survey expressing both worry and hope or optimism:

“I have a lot of anger that this issue has been ignored and not acted on for decades, but also a lot of optimism that we as a species CAN solve this. I'm also worried that not everyone else will accept that Climate change is happening and won't therefore do anything about it. I'm also worried that big business will still be allowed to act with seeming impunity without being held to account by politicians.” (Assembly member, WE7)

“I did find some of the information worrying, we all live on this planet but there are so many people who do not accept that climate change is happening. I did worry how people could be brought round without methods of force which I strongly oppose. But as I continued with the Assembly I believe it can be brought about in a fair way leaving no one behind. If we do what we can and the government and all political parties are compelled to meet deadlines it's achievable. I came away from the Assembly feeling optimistic that everything we have suggested would greatly benefit the have nots encouraging everyone to get on board.” (Assembly Member, WE7)

Comments in the member surveys indicate that decreasing levels of worry and increasing levels of optimism coincided with a growing sense of personal and collective responsibility, and for some also a sense of pride as Assembly members tasked with producing recommendations for the Scottish Government. Comments were also made that related to a sense of agency and empowerment in changing their behaviour and taking urgent climate action. For example:

“It has been a privilege to be a part of the Assembly. Very challenging and a big responsibility to produce these recommendations for the Scottish Government. I have looked at the Interim Report today and it is impressive and I am proud to have contributed to it in even a small way. I know that all I have learned about climate change will affect my lifestyle in the future.” (Assembly member WE7)

“I have been moved and upset at the level of devastation we have inflicted on the planet. I feel proud that I can in some small way make a difference. I feel empowered by the knowledge I now have. I am hopeful that we can meet the challenges and be victorious in our endeavour to be net zero by 2040.” (Assembly member, WE7)

“Scary but empowering. It's given me hope that things can be done and that maybe it's not all doom and gloom.” (Assembly member, WE7)

However, the Weekend 8 surveys results indicate a change in emotional experience. The Weekend 8 meeting was held 11 months after the end of the main Assembly period, and following publication of the Scottish Government response, which members discussed. Member also heard from two government ministers.

Levels of optimism dropped back down to just under a third of respondents. Levels of excitement/hopefulness dropped to six in 10, and worry/upset increased to almost four in 10. Comments from two respondents shed some light on reasons for this change:

“I feel like there was a good intention and the process was very thorough but I'm not convinced that the results will be used effectively by SG (Scottish Government), I have been left with a feeling of deep disappointment and despair with all the knowledge I have gained and the lack of urgency taken on board by our leaders.” (Assembly member WE8)

“I feeling a sense of anger to the Scottish government for exposing us to the harsh reality of the situation with the stark evidence presented to us, given us hope and urged us to work hard at our recommendations to then disappoint us in their response by not acting in the urgent way needed. I feel wounded by the process.” (Assembly member WE8)

After Weekend 7, just over half (54%) of respondents to the member survey agreed with the statement “I am confident that the Assembly report will be taken seriously by Parliament and political parties.” But after Weekend 8, only around a fifth of respondents to the Weekend 8 survey (22%) agreed “I am confident that the Scottish Government will fulfil the commitments made in the Scottish Government response.” Members also produced a Statement of Response in reply to the Scottish Government response. Just under a third of respondents (30%) agreed “I am confident that the Assembly response will be taken seriously by Parliament and political parties.” Whilst these results should be treated with caution due to the lower numbers of members attending Weekend 8 and the smaller survey sample size (see Table 1), the results indicate a decline in confidence in the Scottish Government taking the Assembly seriously.

In the Weekend 8 survey, members were also asked about their satisfaction with the government response. Results were mixed with just over a third of respondents (38%) dissatisfied, around a third neither satisfied nor dissatisfied (35%), and a quarter satisfied (25%). The Statement of Response produced by members during Weekend 8 states: “Members of the Assembly overall are disappointed with the Government's response to many areas of our recommendations, as it does not appear to recognise the urgency behind the Assembly's recommendations for action10.”

Small Group Sessions

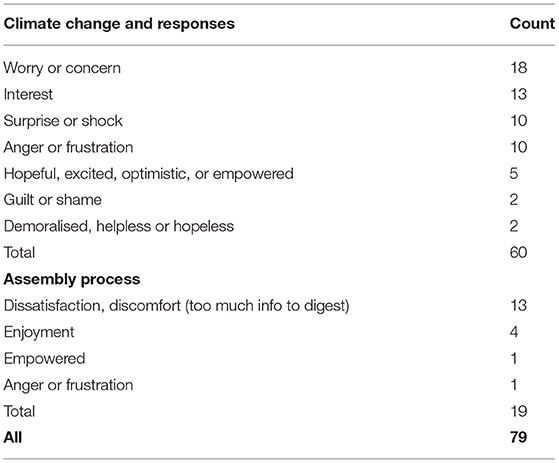

Across the 26 small group sessions, there were 79 instances of emotional expression by members coded in almost 24 h of audio recordings. As shown in Table 4, three quarters were to do with climate change including the evidence presented and measures for tackling climate change, with the remainder relating to the Assembly process.

Climate Change and Measures for Tackling It

Across the sessions, the most common expression related to worry or concern followed by interest, surprise or shock, and anger or frustration. For example:

Worry/concern:

I had worried about the fact that we still have gas boiler grants being offered. (Assembly member WE4)

Interest:

“Yeah, I found it interesting when they were talking about poverty and making sure that transition is fair with regards to income. And it was interesting, one of the presenters said that it can't be put on the individual to make responsible choices when the decision is given to them, because some of those options aren't available to people who can't afford the more expensive but perhaps more ecologically produced products or things that are grown locally but are as a result more expensive than cheaper imported products. That was something to be aware of.” (Assembly member, WE2)

Surprise/shock:

“Yeah, just something stronger to push some pressure on suppliers. Because this is quite a big issue, as the lady who was presenting it just now said, it's actually surprising how much of a difference it would make if people stopped choosing meat and dairy.” (Assembly member WE6)

Anger or Frustration:

“Well I think that always seems unfair if somebody had a holiday house, so they travelled back and forward four and five times a year, and I've subsidised their fuel to go there, I get quite miffed about that.” (Assembly Member, WE2)

Assembly Process

The most common expressions related to dissatisfaction or discomfort with some aspect of the Assembly process. For example:

“I think, all the way through, my concern is that we don't follow through. We set out these grand principles, and then because there's a lack of time, we rush, and we don't actually have a quality output from this process … people don't have enough time to look at things properly. And the recommendations that come out of the end of this are going to be flawed, or diluted, or not as strong as they might have been, without that opportunity.” (Assembly member WE3)

Assembly Report

Through the medium of the Assembly report, the members communicated the outputs of their deliberations to the wider world, and to the Scottish Government and Parliament.

Statements of Ambition

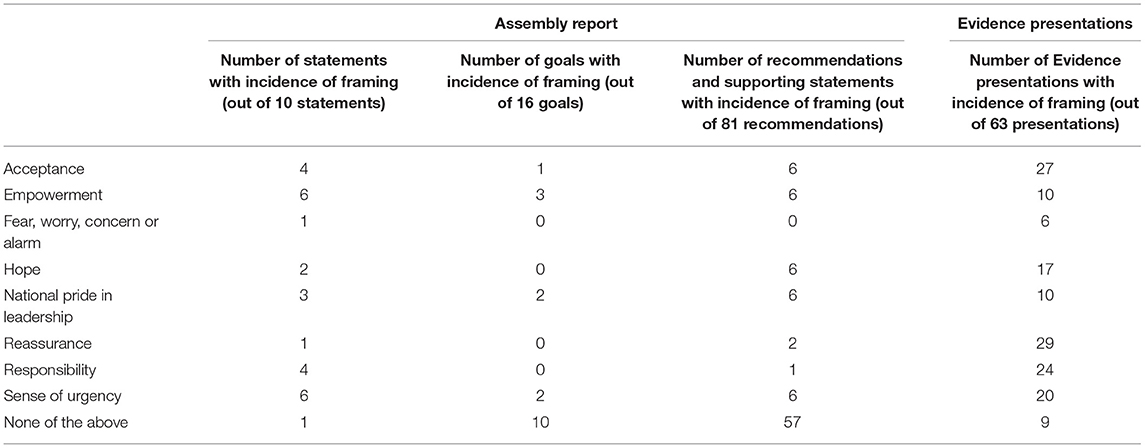

Table 5 shows that 9 of the 10 Statements of Ambition contained frames included in the analysis as potentially having an emotional impact on the reader. Most common were references to urgency and empowerment (6 statements), followed by acceptance and responsibility (4 statements). Three statements had frames relating to sense of national pride in Scotland as a global leader, and one or two statements expressed concern, hope and/or reassurance.

For example, on urgency and empowerment:

Good quality information and knowledge about the urgency required, and things that need to be done, will empower people to take action themselves and drive collective and systemic action across Scottish society.

Acceptance:

As a society we will need to change and adapt to meet the challenges, and recognise that there will be costs.

Responsibility:

Climate change affects every one of us, and no one should evade responsibility.

Goals and Recommendations

The members' goals and recommendations contained relatively fewer frames included in the analysis: just 6 of the 16 goals and 24 of the 81 recommendations and supporting statements (around a third each). With regards to the goals, frames related to empowerment, national pride, acceptance and urgency. The most common frames in the recommendations related to empowerment, acceptance, hope and urgency. Example are included below.

Empowerment:

Empower communities to be able develop localised solutions to tackle climate change. (Goal 10)

National pride:

Lead the way in minimising the carbon emissions caused by necessary travel and transport by investing in the exploration and early adoption of alternative fuel sources across all travel modes. (Goal 6)

Acceptance:

Reduce consumption and waste by embracing society wide resource management and reuse practises. (Goal 1)

Urgency:

Empower local communities to manage underused, unproductive, and/or unoccupied land around them in ways that address the climate emergency through rapid and decisive movement on land ownership reform. (Goal 10 Recommendation 49)

Hope:

This recommendation builds on the principle of the 20-minute community. We believe it is important as it will support people to understand that travelling less, shopping locally and creating more time for leisure can help us in living more sustainably. People will be better informed that change is possible as we embrace localised living, promote wellbeing over Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and share examples as they are trialled and implemented, such as the 4-day week trial in Spain. (Goal 8 Recommendation 41 Supporting Statement).

Evidence Presentations

As noted earlier, the framing of evidence in the presentations may have influenced how the Assembly members interpreted the information, including how threatening they perceived the information to be.

Of the 63 presentations analysed, 54 were coded as containing frames included in the analysis. As shown in Table 5, key messages related to: reassurance, acceptance of the reality of the situation, and responsibility. Around a third of presentations analysed conveyed a sense of urgency.

Reassurance:

“And it will involve of course, a lot of change, but we are more and more reassured that there are really good, really strong and especially cost effective routes to achieving the necessary emissions reductions in every part of society.” (WE5)

Acceptance:

In global terms, Scotland is already starting from a good position, but we need to recognise that more can be done. (WE3)

Responsibility:

So, it is possible and things are happening, and through citizens' assemblies, through yourselves, through governments, through businesses, through communities -we all have a role to play. (WE1)

Urgency:

But the real challenge is to significantly accelerate progress, to bring emissions down as rapidly as possible. We've seen this year that people are able to adapt quickly in a crisis. We now need to ensure that our legislation and policymaking is able to react with the appropriate speed to this climate crisis. (WE4).

Discussion

In recent years there has been growing interest in citizens' assemblies as a way to inform local and national government climate policy. Given that an integral feature of climate assemblies is learning about climate change, this study started with the assumption that difficult emotions would come up for Assembly members.

With regards to Scotland's Climate Assembly, comparing the member survey results with the population survey indicates that Assembly members as a whole had quite a different emotional experience compared to people in general in Scotland.

During the main Assembly period, a higher proportion of members felt hopeful than the population as a whole, with lower proportions feeling worry and overwhelm. Overwhelm can be seen as an important component of anxiety (Pikhala, 2020). Whilst there were no discernible patterns in the member survey data, the population survey data provides support for this claim, with nine in 10 of those who felt overwhelmed also reporting feeling worried or upset. People with existing health conditions were more likely to feel overwhelm than those without.

Levels of optimism that “things will work out fine” were similar to the Scottish population after Assembly Weekend 2 when the study began, and increased considerably over the course of the Assembly. In the population survey, people on high incomes were more likely to feel optimistic than those on low incomes, which suggests that wealth provides a buffer for concern. There was also an association between distortion of facts and increased levels of optimism, as those who thought climate change was a “problem for the future” or “not really a problem” were more likely to feel optimistic than those who considered it an “immediate and urgent problem.” Re-interpreting the threat by reducing its size or putting it into the future is a defence—the emotional impact of the threat is tempered by reducing its power and importance (Hamilton and Kasser, 2009; Andrews, 2017a). Feeling optimistic that “things will work out fine” may serve to absolve the person of taking responsibility for significant action—this is discussed further below.

Impact on mental health also appears to be much lower than is indicated for the Scottish population as whole. The emotion regulation results suggest that many members used emotional avoidance or suppression coping strategies. Whilst the proportion of members who agreed they pushed emotions away to not feel distressed about climate change was similar to the general population, a higher proportion of members agreed they were not aware of feeling any negative or distressing emotions about climate change. Avoidance or suppression coping strategies may be adaptive in the short term if a situation or context makes it unsafe for a person to engage with or express their feelings, but over the longer term this is a form of maladaptive coping with implications for both personal health and for climate action (Rogelberg, 2006; Rust, 2008; Brown and Cordon, 2009; Ray, 2010; Clayton, 2020).

There was not a lot of emotional content in the 26 small group discussions analysed (79 references in 1,418 min—an average of one emotional expression every 30 min in groups of seven people). This could be due to the way in which these sessions were facilitated and the tasks members were set. Where expressions did occur, these tended to be interest, surprise, worry/concern or frustration about what they were learning about climate change and how to tackle it. Whilst this paper has focussed on emotions about climate change, other studies have found that these cannot easily be separated from feelings to do with the context, and that phenomenologically they are interlinked (Andrews, 2017b). There were few expressions about the Assembly process in the small group discussions, but the most common were dissatisfaction or discomfort with some aspect of it. It should be noted, however, that other data indicates that on the whole, members were satisfied with the Assembly process (Andrews et al., 2022).

These results can be considered in the context of the framing of the evidence presented to the members as part of the Assembly process. Concern or worry was conveyed in just one in 10 presentations analysed, and urgency in one in three presentations analysed. Other research into Scotland's Climate Assembly finds that the evidence provided to members may have, on the whole, underplayed the severity of the climate crisis, with some interviewees wondering whether the evidence, particularly in the first two weekends, had sufficiently conveyed the severity and “emergency” of climate change (Andrews et al., 2022). The evidence presentations analysed in this study tended to be framed in relation to: reassurance that solutions can be found and implemented, acceptance of the reality of the situation, and responsibility to act. The limits to adaptation discussed in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report from Working Group II (IPCC, 2022), are not explained to members.

It is common for climate science and evidence on mitigation and adaptation to be communicated without emotion. For example, the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report on impacts, vulnerability and adaptation (Working Group II contribution) acknowledges the important role of emotion in risk perception, decision-making and in communication (IPCC, 2014), yet the report itself is unemotional. Similarly in the Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report, a dire picture is presented in a stark language of facts and figures. Scientists are not generally encouraged to bring emotions into their research reports, and to do so threatens their status as a credible, rational and objective scholar (Corner et al., 2018; Hoggett and Randall, 2018). This denigration of emotion has a long history: moral philosopher Mary Midgley explains that in the seventeenth century when Descartes disembodied the mind in a “violent separation” of mind from body (2003, p. 39), emotion came to be seen as soft and “beneath the dignity of scientists” (2003, p. 18). The Scientific Revolution gave reason primacy and diminished emotion, creating a dualism that has persisted over the centuries. A study by climate psychologists Paul Hoggett and Rosemary Randall discusses how social defences against anxiety enable climate scientists to do their work relatively undisturbed by the implications of climate change, and to provide abstracted information that is free of personal meaning (Hoggett and Randall, 2018).

Eco-anxiety is reported to be associated with strong feelings of helplessness or powerlessness (Pikhala, 2020), whilst taking action can reduce eco-anxiety and benefit mental wellbeing by providing a greater sense of agency and control, increase feelings of meaning and empowerment, and provide social support through connexion with like-minded communities (Lawrance et al., 2021). Participating in the Assembly provided the members with a focussed sense of purpose and agency, as well as some sense of being part of a community, even if temporary (Andrews et al., 2022). The Assembly report balances urgency with expressions of empowerment.

It is proposed that this sense of purpose and agency, along with exposure to evidence that on the whole may have underplayed the severity of the climate crisis and that was framed in ways that reassured the members that climate change can be tackled in an effective and fair way, helps explain the difference in emotional experience between the Assembly members and the general population of Scotland.

However, after receiving the Scottish Government's response to their recommendations almost a year after the last Assembly meeting, there are indications that levels of optimism and hopefulness dropped and levels of worry increased, with members expressing overall disappointed with the response.

It is out with the scope of this study to assess whether the optimism felt by members was unrealistic or whether their deliberations involved wishful thinking. However, as emotions play a vital role in guiding behaviour and in decision making, it is important to consider the implications for the outputs of deliberative processes such as climate assemblies, if members do hold such perspectives. Unrealistic optimism and wishful thinking are forms of defence against facing difficult truths, and are considered maladaptive if maintained over the longer term because they serve to absolve the person from having to take radical action (Crompton and Kasser, 2009; Foster, 2015; Andrews and Hoggett, 2019). Indeed, analysis of the Assembly Report finds that only half the recommendations involve, or could involve (depending on how the recommendation is implemented including the scale and speed of change) transformational change,11 with the remainder involving incremental change (Andrews et al., 2022).

These findings provide insight and enhance our understanding of how people perceive climate risk and how they experience that emotionally in the particular context of a climate Assembly. The emotions members experienced also created knowledge, although this was not explored in this study.

The findings can make a practical contribution in informing the design of future deliberative processes in ensuring that members' emotional wellbeing is considered as part of their duty of care, and can be used by climate policy makers in inform their public engagement strategies on climate policy. The findings can also be used by the therapeutic community and health and wellbeing practitioners in their work to support people in regulating their emotions about climate change and climate policy in an adaptive way.

However, the results presented in this paper are just an initial attempt to investigate the emotional experience of people participating in citizens' assemblies on climate change. Further research is required to determine if and how members' emotional experience changes over the longer term, whether their sense of purpose and agency in their role as Assembly members changes, and how members continue to engage with the Scottish Government on their response to the Assembly recommendations. Such research with other climate assemblies would also be useful.

It is interesting that in the population survey, some of those who think climate change is a “problem for the future” or “not really a problem at all” agree that their feelings about climate change are having a negative impact on their mental health. Further research is required to understand the reasons why.

The IPCC sixth assessment report on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability concludes that a significant adaptation gap exists for human health and wellbeing, and that there is not yet robust evidence on the prevalence or severity of climate anxiety (IPCC, 2022). Research on climate emotions and climate distress is nascent, and would benefit from more situated research that brings insight into contextual factors influencing emotional experience, as well as research on factors influencing psychological resilience, the efficacy of interventions to support adaptive emotion regulation and enhance resilience, and on the relationship between types of optimism (realistic, unrealistic) and types of climate action.

Limitations of the study include use of non-standardised measures to investigate the emotional experience of Assembly members as such measures do not currently exist. The member and population surveys upon which this study was based were not designed specifically or solely for the purpose of investigating emotional experience. Therefore, the number of questions related to emotional experience that could be included was limited, in order to keep survey length within a reasonable length to maximise response rates. As the member survey was completed by around two thirds of Assembly members, these results are indicative only of the experience of the members as a whole. Correlational analysis on the population survey data was not conducted. Lastly, the population study is weighted to 2011 Census data and may not reflect recent demographic changes in Scotland.

Author's Note

Data analysed for this paper was collected as part of a wider research programme on Scotland's Climate Assembly funded by the Scottish Government and conducted independently of the Assembly.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Scottish Government Social Research. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Study design and conceptualisation and literature searches by NA. Member survey data used in this study was designed, collected, verified, and analysed by NA. Population survey data collected, verified, and topline analysis by Deltapoll, with further population survey analysis by NA. Group discussion transcript analysis, evidence presentation transcripts analysis, and Assembly report analysis by NA and Alexa Green. This article was drafted and finalised by NA with input from no other persons.

Funding

Data analysed for this paper was collected as part of a wider research programme on Scotland's Climate Assembly funded by the Scottish Government and conducted independently of the Assembly. The funders and Assembly organisers had no role in the design of the study presented in this paper; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of Alexa Green who worked on analysis of the group discussion transcripts, the evidence presentation transcripts and the Assembly report, Deltapoll who conducted the population survey and provided the data analysed in this paper, and the contributions of Scott McVean and Gemma Sandie in quality assurance of the member survey topline analysis and for producing the charts.

Footnotes

1. ^See https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2019/15/section/9/enacted.

2. ^See https://www.climateassembly.scot/full-report.

3. ^See https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-response-scotlands-climate-assembly-recommendations-action/.

4. ^Weekend 1 survey did not include emotion questions.

5. ^The Climate Psychology Alliance is a membership organization comprising therapeutic practitioners, academics, and researchers. See https://climatepsychologyalliance.org.

6. ^Intelligent verbatim standard: captures what was said but without every “um,” repeated filler words such as “you know,” stutters or stammers.

7. ^https://www.climateassembly.scot/meetings

8. ^https://www.youtube.com/c/ScotlandsClimateAssembly/videos

9. ^It should be noted that the weighted sample size for the “not really a problem” group is only 59.

10. ^https://www.climateassembly.scot/statement-of-response

11. ^Transformational change is defined in this research as fundamental changes to the attributes of existing systems or that create new systems, likely to involve reassessing values, identities, beliefs and assumptions; and challenging or disrupting existing structures including power structures.

References

American Psychological Association (2009). Psychology & Global Climate Change: Addressing a Multi-Faceted Phenomenon and Set of Challenges. Report of the American Psychological Association Task Force on the Interface Between Psychology and Global Climate Change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Andrews, N. (2017a). Psychosocial factors affecting enactment of pro-environmental values by individuals in their work to influence organisational practices (phd thesis). Lancaster, PA: Lancaster University.

Andrews, N. (2017b). Psychosocial factors influencing the experience of sustainability professionals. Sustain. Account. Manage. Policy 8, 445–469. doi: 10.1108/SAMPJ-09-2015-0080

Andrews, N., Elstub, S., McVean, S., and Sandie, G. (2022) Scotland's Climate Assembly: Research Report. Scottish Government Social Research. Edinburgh: Scottish Government Social Research.

Andrews, N., and Hoggett, P. (2019). “Facing up to ecological crisis: a psychosocial perspective from climate psychology,” in Facing Up to Climate Reality: Honesty, Disaster and Hope, ed J. Foster (London: Green House; London Publishing Partnership), 155–171.

BACP (2020). Mental health impact of climate change. BACP.co.uk. Available online at: https://www.bacp.co.uk/news/news-from-bacp/2020/15-october-mental-health-impact-of-climate-change/ (accessed January 21, 2021).

BBC Newsround (2020). Climate anxiety: survey for BBC Newsround shows children losing sleep over climate change and the environment. BBC.co.uk. Available online at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/51451737 (accessed April 6, 2020).

Brown, K. W., and Cordon, S. (2009). “Toward a phenomenology of mindfulness: subjective experience and emotional correlates,” in Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness, ed F. Didonna (New York, NY: Springer), Ch4.

Brown, K. W., and Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 84, 822–848.

Chapman, D. A., Lickel, B., and Markowitz, E. M. (2017). Reassessing emotion in climate change communication. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 850–852 doi: 10.1038/s41558-017-0021-9

Clayton, S. (2020). Climate anxiety: psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 74, 102263. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263

Corner, A., Shaw, C., and Clarke, J. (2018). Principles for Effective Communication and Public Engagement on Climate Change: A Handbook for IPCC Authors. Oxford: Climate Outreach.

Crompton, T., and Kasser, T. (2009). Meeting Environmental Challenges: The Role of Human Identity. Godalming: WWF-UK.

Curato, N., Farrell, D., Geißel, B., Grönlund, K., Mockler, P., and Pilet, J. B. (2021) Deliberative Mini-Publics: Core Design Features, Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Schultz, P. P., and Niemiec, C. P. (2015). “Being aware and functioning fully,” in Handbook of Mindfulness; Theory, Research and Practice, eds K. W. Brown, J. D. Creswell, and R. M. Ryan (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 112–129.

Graves, L. (2018). Which works better: climate fear, or climate hope? Well, it's complicated. TheGuardian.com. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jan/04/climate-fear-or-hope-change-debate

Hamilton, C., and Kasser, T. (2009). Psychological Adaptation to the Threats and Stresses of a Four Degree World [Conference Paper] Four Degrees and Beyond Conference, Oxford University 28-30 Sept (Oxford).

Hoggett, P., and Randall, R. (2018). Engaging with climate change: comparing the cultures of science and activism. Environ. Values 27, 223–243.

IPCC (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

IPCC (2018). “Global warming of 1.5°C,” in An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, eds V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P. R. Shukla, et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 49–91.

IPCC (2022). “Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability,” in Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 1–181.

Kaplan, E. A. (2020). Is climate-related pre-traumatic stress syndrome a real condition? Am. Imago 77, 81–104.

Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environ. Commun. 4:70–81 doi: 10.1080/17524030903529749

Lawrance, E., Thompson, R., Fontana, G., and Jennings, N. (2021). The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing: Current Evidence and Implications for Policy and Practice. London: Grantham Institute and the Institute of Global Health Innovation, Imperial College London.

Macy, J., and Brown, M. (2014). Coming Back to Life. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island.

Mann, M. E., Hassol, S. J., and Toles, T. (2017). Doomsday scenarios are as harmful as climate change denial. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/doomsday-scenarios-are-as-harmful-as-climate-change-denial/2017/07/12/880ed002-6714-11e7-a1d7-9a32c91c6f40_story.html?utm_term=.67b847342ebd

Marks, E., Hickman, C., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, E. R., Mayall, E. E., et al (2021). Young People's Voices on Climate Anxiety, Government Betrayal and Moral Injury: A Global Phenomenon. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3918955

Nisbet, M. C. (2009) Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environ. Sci. Pol. Sustain. Develop. 51, 12–23. doi: 10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23.

Pikhala, P. (2020). Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability 12, 10149. doi: 10.3390/su122310149

Randall, R. (2019). Climate Anxiety or Climate Distress? Coping with the Pain of the Climate Emergency. Available online at: https://rorandall.org/2019/10/19/climate-anxiety-or-climate-distress-coping-with-the-pain-of-the-climate-emergency/ (accessed November 7, 2021).

Ray, S. J. (2010). A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Reser, J., and Swim, J. K. (2011). Adapting to and coping with the threat and impacts of climate change. Am. Psychol. 66, 277–289.

Roberts, D. (2017). Does hope inspire more action on climate change than fear? We don't know. Vox.com. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2017/12/5/16732772/emotion-climate-change-communication

Rogelberg, S. G., (ed.). (2006). Encyclopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. London: Sage.

Shaw, C., Wang, S., and Latter, B. (2021). How Does the Framing of Climate Change Affect the Conclusions Reached in Climate Assemblies? Draft Research Briefing for Knowledge Network on Climate Assemblies. Available online at: https://climateoutreach.org/reports/knoca-climate-assemblies-framing/

Triodos (2019). How is the climate emergency making us feel? Triodos.co.uk. Available online at: https://www.triodos.co.uk/articles/2019/how-is-the-environmental-crisis-making-us-feel (accessed April 6, 2020).

Truverra (2020). Does the UK suffer from eco-anxiety? Truverra.com Available online at: https://truverra.com/en/learn/does-the-uk-suffer-from-eco-anxiety/ (accessed April 6, 2020).

Verplanken, B., and Roy, D. (2013) “My worries are rational, climate change is not”: Habitual ecological is an adaptive response. PLoS ONE 8, e74708s. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074708

Weinstein, N., Brown, K. W., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). A multi-method examination of the effects of mindfulness on stress attribution, coping, and emotional well-being. J. Res. Personal. 43, 374–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.12.00

YouGov (2021). Environment Tracker survey results. YouGov.com Available online at: https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/o7gbkrno79/Internal_EnvironmentTracker_210829_Wave1_W.pdf (accessed September 15, 2021).

Keywords: emotion regulation, eco-anxiety, climate anxiety, deliberative democracy, participatory democracy, citizens' assembly, climate psychology, climate science framing

Citation: Andrews N (2022) The Emotional Experience of Members of Scotland's Citizens' Assembly on Climate Change. Front. Clim. 4:817166. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2022.817166

Received: 17 November 2021; Accepted: 30 March 2022;

Published: 25 April 2022.

Edited by:

Scott Bremer, University of Bergen, NorwayReviewed by:

John Malcolm Gowdy, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, United StatesRaul Salas Reyes, University of Toronto Scarborough, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Andrews. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nadine Andrews, bi5hbmRyZXdzQGxhbmNhc3Rlci5hYy51aw==

Nadine Andrews

Nadine Andrews