- Department of Geography and Environmental Science, School of Archaeology, Geography and Environmental Science University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom

There are a range of emotions and affects related to climate change, which are experienced by different publics at different times. These include grief, fear, hope, hopelessness, guilt, anxiety and anger. When unacknowledged or unprocessed, these emotions and affects can contribute to emotional paralysis and systems of socially organized denial, which can inhibit climate change engagement at individual and collective scales. Emotional reflexivity describes an awareness of the ways that people engage with and feel about issues, how this influences the actions they take and their perceptions of possible change. Emotional reflexivity could be developed through approaches that incorporate psychological and social engagements with climate change. In this paper I highlight knowledge gaps concerning how practices of emotional reflexivity relate to people becoming and remaining engaged with climate change and how emotions move and change through the questions of: what is the role of emotional reflexivity in engaging with climate change? and how do emotions associated with climate move and change?, responding to the gap, and associated question of what approaches could help develop emotional reflexivity around climate change?, in this paper I present a summary of research conducted in the UK during 2018–2020 with participants of two such approaches: the “Work That Reconnects”/“Active Hope” and the “Carbon Literacy Project”. I demonstrate how emotional reflexivity was developed through: 1. Awareness and acknowledgment of emotions, which helped to facilitate feedback between the dimensions of engagement and contributed to becoming engaged with climate change, and 2. Expression and movement of emotions, which enabled a changed relationship to, or transformation of emotions, which contributed to a more balanced and sustained engagement. Key findings included the relationship between ongoing practices of emotional reflexivity and engaging and sustaining engagement with climate change, and that some approaches helped to cultivate an emotional reflexivity which contributed to a “deep determination” and ongoing resource to act for environmental and social justice, and to live the future worth fighting for in the present. However, without ongoing practices, my research evidenced forms of defensive coping, ambivalence and vacillation, which impeded active engagement over time. These findings attest to the importance of attention to the dynamics and movement of emotions and affects relating to climate change.

Introduction

Introduction and Literature Review

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports (IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018, 2021) reinforce the need for deep and urgent action on climate change mitigation and adaptation. Such mitigation and adaptation action is not happening at the pace, depth and scale needed (IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018). Climate change is still primarily framed as an exterior problem, understood through science, and addressed through politics, infrastructures, technology and behaviors (Ives et al., 2020). The IPCC statement of the need for “rapid and far-reaching transitions” and “deep emissions reductions in all sectors” (IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018, p.21) focused primarily on technical, physical and political challenges.

There is increasing evidence that inner dimensions play important roles in how people respond to and engage with climate change and the associated risks. Inner dimensions include emotions, affects, value systems, mindsets (Munshi et al., 2020; Wamsler et al., 2020; Woiwode et al., 2021); spirituality and religion (Rothberg and Coder, 2013; Veldman et al., 2013; Jenkins et al., 2018; Fredericks, 2021); relational cultures (Whyte, 2019); psychological aspects such as defenses against disturbing information (Norgaard, 2011; Lertzman, 2015; Moser, 2016; Clayton et al., 2017); the relationships between mental health and climate change (Clayton et al., 2015; Lawrance et al., 2021); and the disjunct between climate change being framed as future dystopia, as opposed to the past, current and ongoing impacts of colonialism and impacts of systemic oppressions that climate change exacerbates (Whyte, 2018). Inner dimensions are increasingly recognized as “deep leverage points” for change and transformation at individual, cultural and political scales (Meadows, 1999; Berzonsky and Moser, 2017; O'Brien, 2018; Wamsler et al., 2020; Woiwode et al., 2021).

Addressing climate change alongside other socio-ecological problems requires approaches that link inner and outer dimensions of change, and which encourage attention to the interplay between the “practical, political and personal” spheres of transformation (O'Brien, 2018, p.153). Whilst the broader field of research on inner dimensions of sustainability highlights some approaches that connect such spheres of transformation - such as mindfulness (Wamsler, 2018) - there is a demonstrated need to learn from individuals and communities already harnessing such approaches (Lawrance et al., 2021, p.181; Moser, 2015).

This literature review explores the following themes: Emotions Relating To Climate Change, Emotional Dimensions Of Climate Change Engagement, Defense And Denial, and Emotional Reflexivity. This is followed by a section on defining the research area, which contains a description and literature review of the two case studies used. The research gaps are highlighted, corresponding to the three research questions which this paper orients around: how do emotions associated with climate change move and change?; what is the role of emotional reflexivity in engaging with climate change?; and what approaches could help develop emotional reflexivity around climate change?

Emotions Relating to Climate Change

There are a range of emotions (conscious feelings that can be named and have an object), and affects (bodily sensations, and conscious or subconscious feelings without a specific object) related to climate change2. These emotions and affects are experienced by different publics at different times, and interconnected. Emotions relating to climate change are influenced by the risk and proximity to the causes or impacts of climate change, and whether the impacts are direct or indirect (Albrecht et al., 2007; Doppelt, 2016; Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018; Helm et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Lawrance et al., 2021).

The range of emotions and affects include overarching clusters such as climate or eco-anxiety (Uchendu, 2020; Lawrance et al., 2021; Marks et al., 2021), alongside emotions and affects such as: grief and processes of anticipatory mourning for loss of futures, ecosystems, cultures, and current lifestyles (Randall, 2009; Norgaard, 2011; Lertzman, 2015; Head, 2016; Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018; Marks et al., 2021); fear (O'Neill and Nicholson-Cole, 2009; Norgaard, 2011; Weintrobe, 2012); guilt (Kleres and Wettergren, 2017; Fredericks, 2021); and hope and hopelessness (Head, 2016; Moser, 2016; Kleres and Wettergren, 2017; Ford and Norgaard, 2019). Emotional and affective responses to climate change are also apparent through numbness and ambivalence (Lertzman, 2015); and through pre- and post-traumatic stress with its attendant implications for mental health (Doppelt, 2016; Clayton et al., 2017; Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018; Woodbury, 2019; Lawrance et al., 2021). Alongside these largely pessimistic or negative emotions, emotions such as hope (Moser, 2015; Head, 2016), love (Prentice, 2003); wonder (Ryan, 2016) are evident, and seen as important components of climate change engagement.

Emotions are not static: they move, change, transform and can be transformative. Randall (2009) draws on grief theories to underline the importance of acknowledging and working through anticipated losses of lifestyle connected to climate change mitigation, and Osborne (2018) describes the hope that can emerge when depression and grief is acknowledged. Emotions are connected to other emotions, ideas, values and objects (Bondi, 2005; Ahmed, 2014; Gould, 2015; Lertzman, 2015; Head, 2016), are influenced by context, culture, history and biography (Cox, 2009; Pain, 2009).

Whilst emotions and affects relating to climate change have been documented, how emotions move and change and the impact that this has on climate change engagement has received less attention. Head poses the question of “what is the performative, generative role of such emotions?” (Head, 2016, p. 77). This question highlights a research gap, and is the focus of the research question (RQ) “how do emotions connected to climate change move and change?” It also encourages a deeper investigation into the emotional dimensions of climate change engagement, which I turn to next.

Emotional Dimensions of Climate Change Engagement

Climate change engagement refers to forms of communication about climate change to different audiences. Within the Global North, climate change engagement usually has the aim of strengthening the capacities of different actors to contribute to mitigation and adaptation action (IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018).

Widely used definitions of climate change engagement describe it as a “personal state of connection with the issue of climate change” (Lorenzoni et al., 2007, p. 446), a dynamic process encompassing three inter-dependent aspects of “cognition” (thinking), “emotion and affect” (feeling), and “behaviours” (doing) (Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Whitmarsh and O'Neill, 2011; Moser, 2016). Climate change engagement literature attests to the importance of the connection between all three dimensions of engagement, yet in practice the emotional dimensions are frequently glossed over, and engagement has primarily focused on information and action (Burke et al., 2018). Those who are concerned, have a desire to be engaged and a degree of agency can feel overwhelmed or despondent, which can lead to a withdrawal of active engagement (Büchs et al., 2015).

The more negative or pessimistic emotions such as grief have impeded engagement. Ecological grief has contributed to feelings of overwhelm and despondency (Randall, 2009; Lertzman, 2015; Head, 2016; Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018). This includes: grief for current and future losses of people, places and ecosystems, losses of environmental knowledge and identity (Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018); anticipated grief for losses of existential safety and a “future characterized by hope” (Head, 2016, p. 168); and threats or implied losses to current lifestyles (Randall, 2009). Correspondingly, processes to acknowledge and work through griefs need to be integrated within climate change engagement (Randall, 2009; Lertzman, 2015; Head, 2016).

Emotions related to climate change engagement are influenced by perceptions and experiences of governments, political systems, perceived sense of security and trust in authorities (Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Brugger et al., 2013; Marks et al., 2021); the social and cultural context (Norgaard, 2011; Munshi et al., 2020); the type of change desired (Hulme, 2009); perceptions and experiences of individual and collective agency, and connection to groups who are actively engaged (Howell, 2013). Emotional responses vary over time. Those who have been engaged long term can experience frustration and burn-out due to the slow pace of change, prompting the need to consider engagement strategies for the long term (Moser, 2016).

Some emotions connected to climate change can be uncomfortable or painful. Emotional suffering is connected to both experiencing the impacts (Doppelt, 2016; Lawrance et al., 2021) and knowing and caring about the causes and impacts of climate change (Randall, 2009; Wapner, 2014). Defending against such responses can contribute to coping strategies and psychological defenses that operate at individual and cultural levels (Moser, 2016; Ford and Norgaard, 2019). Thus, Lertzman (2015) highlights the need for dynamic models of engagement which pay attention to how people experience anxieties, dilemmas (e.g. wanting to use low-carbon travel, but flying due to time or financial pressures) and forms of defense and denial, alongside attention to the cultural context. Lertzman asserts that “much of what presents as barriers may be viewed alternately as expressions of profoundly complex affective-laden and unconscious dilemmas that impede more coherent forms of alignment between what we value and what we practice” (Lertzman, 2015, p. 20). The next section explores forms of denial at individual and cultural levels.

Defense and Denial

Denial is a form of defense against powerful feelings and threats to identity. Forms of denial such as disavowal (Weintrobe, 2012) and the social organization of denial (Norgaard, 2011), can contribute to the maintenance of forms of privilege (e.g. maintaining high-carbon lifestyles). Disavowal is akin to implicatory denial (Cohen, 2012; Weintrobe, 2012), where the facts are not disputed, but their significance is minimized.

Disavowal operates as a defense against feeling pain, anxiety or grief, and is evident through holding contradictory stories apart, of knowing and not knowing. Known as splitting3, this prevents stories being examined together, and the working through of the attendant anxiety (Lertzman, 2015). What starts as an adaptive coping strategy against unbearable thoughts and feelings becomes a maladaptive coping strategy if used to systematically block painful information (Andrews, 2017). This can lead to numbing and apathy (Lifton, 2017), and contribute to states of ambivalence, of vacillating, competing and opposing feelings and values (e.g. feeling grief for climate impacts and mitigation implications of lifestyle changes), which can undermine engagement and agency (Lertzman, 2015).

The social organization of denial (Norgaard, 2011) involves cultural norms and practices which demarcate inclusion or exclusion of subjects of conversation and discourse and contributes to cultural climate silences (Stoll-Kleemann et al., 2001; Norgaard, 2011; Marshall, 2014; Doppelt, 2016; Moser, 2016; Corner and Clarke, 2017; Helm et al., 2018). Such practices have affected climate scientists, who have been undermined and challenged when speaking about their findings (Hoggett and Randall, 2018) or accused of being alarmist when conveying “alarming” data (Risbey, 2008; Brysse et al., 2013). Whilst these climate “silences” are changing through coverage of scientific reports (IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018, 2021) and increasing civic campaigning of recent years (e.g. Extinction Rebellion, Pipeline protests, the Fridays for Future movements), silences still exist around discussing the severity, implications and impacts of climate change, and acknowledging the associated feelings and emotions (Head, 2016; Head and Harada, 2017; Hoggett and Randall, 2018). Discussing climate change and associated feelings is perceived as socially risky.

Lertzman argues that climate change engagement approaches which start with an understanding of how such inner conflicts, dilemmas or ambivalence are acknowledged, negotiated and worked with enables such states to be seen “as achievements … [to be] integrated for more authentic modes of engagement with a dynamic, uncertain world” (Lertzman, 2015, p.4). Thus, engagement approaches need to account for such psychological dimensions.

This and the previous section have highlighted the importance of engagement approaches to acknowledge, articulate and work through the emotional and affective dimensions of climate change, such as defenses and anxieties in a safe or contained way (Lertzman, 2015; Head, 2016; Moser, 2016; Wamsler et al., 2020; Lawrance et al., 2021; Woiwode et al., 2021). One way of exploring emotions related to climate change is through the development of emotional reflexivity, which I turn to next.

Emotional Reflexivity

Emotional reflexivity describes an embodied and relational awareness of - and attention to - the ways that people engage with and feel about issues, how this influences their responses, the actions they take, the stories and worldviews they inhabit and their perceptions of individual and collective agency (King, 2005; Brown and Pickerill, 2009; Holmes, 2010; Burkitt, 2012; Adams, 2016). It encourages an awareness of how emotions inform processes of change (Pain, 2009). For example Holmes describes emotional reflexivity as “the practices of altering one's life as a response to feelings, and to interpretations of one's own and other's feelings about one's circumstances” (Holmes, 2015, p.61). This approach to emotional reflexivity acknowledges the moving, changing and transformative potential of emotions (Ahmed, 2014), and that awareness can contribute to changes of emotions and relationship to emotions.

Developing emotional reflexivity is influenced by the emotional habitus: the space afforded within contexts and social groups to acknowledge or explore emotions, and the cultural “ways of emoting” (Gould, 2009; p.32–33). Norgaard (2011) highlighted how forms of emotion management and the avoidance of emotions has worked against participation in social movements, and suggests that practices of emotional reflexivity could encourage climate change engagement. Maintaining emotional reflexivity is influenced by one's “post-reflexive choices” (Adams, 2006), the habitus within which to enact new awareness and insight.

Research on emotional reflexivity in the context of socio-ecological action has focused on its role in sustaining those already involved (King, 2005; Brown and Pickerill, 2009). While Brown and Pickerill (2009) and King (2005) conclude that emotionally reflexive practices can help to sustain activism, they both urge further research into the relationship between participating in “practices of emotional reflexivity” and “becoming and remaining activists” (King, 2005, p. 166 in Brown and Pickerill, 2009, p. 33).

This paper responds to the knowledge and research gaps identified by King (2005), Norgaard (2011) and Brown and Pickerill (2009), with the main RQ of “what is the role of emotional reflexivity in engaging with climate change?”, and sub-questions of “how do emotions connected to climate change move and change?” and “what approaches could help develop emotional reflexivity around climate change?” To answer these questions, this paper discusses how emotional reflexivity was developed through two engagement approaches in the U.K., the movement of emotions connected to climate that occurred, and the impact in relation to climate change engagement.

Defining the Research Area

A range of approaches and practices exist which encourage the acknowledgment, expression and/or working through of emotions around socio-ecological issues including climate change (Hamilton, 2019, 2020; Mark and Lewis, 2020)4. These approaches are positioned at the interface of psychological and social engagements with climate change, the spaces between private therapeutic practices and the more public workplaces and civil society organizations (CSOs). They vary in depth, timescale, scale and accessibility, include group workshops, exercises or individual practices, and draw on a range of lineages including western psychotherapeutic, spiritual practices such as Buddhist meditation, and indigenous wisdom traditions (Prentice, 2003). They are part of a growing field of praxis and research relating to inner transformations, involving approaches, competencies and practices (Wamsler et al., 2020; Woiwode et al., 2021).

The existing literature on the variety of approaches highlights that participation can enable a more resilient and sustained engagement with socio-ecological issues like climate change (e.g. Randall, 2009; Hollis-Walker, 2012; Büchs et al., 2015; Lilley et al., 2016). However, there are gaps in both academic and practitioner literatures concerning the impact of such approaches in relation to climate change engagement. To address these gaps, this paper focuses on research involving participants in two approaches: the Carbon Literacy Project (CLP), and the Work that Reconnects (WTR) and related Active Hope (AH). Below, I briefly review the context and existing research of these approaches.

Carbon Literacy Project

The Carbon Literacy Project (CLP) “offers everyone a day's worth of Carbon Literacy learning” (Carbon Literacy Project., 2020). The CLP learning assumes no prior knowledge of climate change and is delivered through one day-long workshop by trained facilitators, tailored to the organization and participants. Using presentations, games and discussions, the workshops guide participants through the science and impacts of climate change, explore the relative carbon footprints of individual behaviors (e.g. diet, transport options, domestic energy), encourage reflection on individual and collective action, and highlight relevant organizations taking climate change action. Participants are encouraged to make action pledges. The workshops give space to acknowledge and reflect on the participants' emotional responses to climate change, but do not focus on exploring emotions in more depth.

Research on CLP participation demonstrates increased motivation, agency and engagement (Richards, 2017); a range of political engagement (Moore, 2017), and the connections between participating and individual and collective climate action (Chapple et al., 2020).

The Work That Reconnects and Active Hope

The WTR is an evolving body of experiential group work practices developed in the USA, Europe and Australia in the 1970s onwards by Joanna Macy and colleagues (Macy and Brown, 2015), drawing on systems theory, Buddhist philosophy and deep ecology. The WTR is primarily – but not exclusively - aimed at those with an existing degree of interest and engagement with socio-ecological issues. It aims to empower participants to actively contribute to a life sustaining society, through opening to emotions and developing holistic connections to self, others and the more-than-human world.

The WTR follows a four-part spiral structure of “coming from gratitude”, “honoring our pain for the world”, “seeing with new/ancient eyes”, and “going forth” (Macy and Brown, 2015). Depending on the context, participants and workshop length (typically ranging from 1–2 h, a day or weekend), the practices involve a mixture of solo contemplations, active listening exercises, movement, guided meditations, nature connection, games, ritual and ceremony. Rituals and ceremonies form a container to explore parts of the spiral in greater depth. For example, in honoring pain, ceremonial exercises such as the “Truth Mandala” “bowl of tears” and “despair ritual” (Macy and Brown, 2015; Work that Reconnects, 2021) all create a strong container to hold and enable the expression and witnessing of emotions in groups.

Active Hope (AH) (Macy and Johnstone, 2012) is a book form of the WTR to enable broader involvement. AH groups encourage participants to work through the book and come together to discuss, reflect and explore exercises. As they draw from the same source, I use the abbreviation WTR/AH to refer to both the WTR and AH and distinguish when necessary. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the WTR and AH was primarily offered in face-to-face workshop formats. Since COVID-19, both have increasingly been offered through online workshops, which have enabled a wider uptake.

The WTR/AH has been integrated into and used in many community-focused approaches to climate change engagement. Examples include Inner Transition (I.T.) of the Transition movement of geographically based community initiatives taking action on climate and wider social and environmental issues (Hopkins, 2011; Feola and Nunes, 2014; Transition Network, 2021), and Deep Adaptation (Bendell, 2018; Deep Adaptation Forum., 2020).

Research into the impacts of participation in WTR and AH has primarily been conducted by those who also facilitate the WTR (Johnstone, 2002; Prentice, 2003; Hollis-Walker, 2012; Hathaway, 2017)5. The key findings are that: connections to self, others and the more-than-human world were strengthened in participants; the workshops engendered a renewed commitment to action (Johnstone, 2002; Hollis-Walker, 2012; Hathaway, 2017); and most participants found workshops “personally healing” (Johnstone, 2002). These pro-social and ecological benefits were most common for those with pre-existing active engagement in socio-ecological action. Hathaway (2017) highlighted that further opportunities to reflect on the workshop insights could help to integrate intentions into practice.

Methodology

This paper draws on doctoral research in the UK which involved exploring a range of engagement approaches to climate change that incorporated acknowledgment and/or expression of emotions. Semi-structured interviews and conversations were conducted with 27 facilitators from a range of approaches (Hamilton, 2019).

Two approaches were chosen for in-depth participant interviews, which represented contrasting forms of engagement with climate change: the Carbon Literacy Project (CLP), and the Work that Reconnects and Active Hope (WTR/AH). These approaches contrasted in: the contexts they were offered (within workplace for CLP, and voluntary participation outside workplace for WTR/AH); degree of emotional acknowledgment or expression (acknowledging emotion in CLP/acknowledging and expressing emotion in the WTR/AH); and focus on climate change (encouraging active engagement in CLP, and encouraging and exploring emotional aspects of climate change engagement in the WTR/AH).

Participant interviewees (“participants” in this paper) were contacted through a range of facilitators of the WTR/AH and the CLP (some of whom I had interviewed), who forwarded my research requests by email or postcard. My purposive sampling criteria included participants who had experienced a WTR/AH or CLP workshop/s within 18 months. Distributing requests through facilitators ensured participant recruitment from a variety of contexts (the workplace, workshops at festivals or events, in connection to CSOs), over different timescales, those with differing familiarity of emotional exploration, and with differing degrees of engagement with climate change.

Emotional Reflexivity and Psycho-Social Approaches

An emotionally reflexive research methodology was used, drawing on emotional geography (Bondi, 2005; Brown and Pickerill, 2009; Pain, 2009; Head, 2016; Maddrell, 2016) and psycho-social methods. This included attention to the affective and embodied experiences of both the research interview encounter and the process of interpretation and analysis (Dewsbury, 2010; Bondi, 2014). Psycho-social methods are informed by the interplay between psychotherapeutic approaches and the social and cultural context. They aid the exploration and reflexivity of the dynamic relationships between degrees of conscious, subconscious and unconscious states (Hollway and Jefferson, 2000; Weintrobe, 2012; Adams, 2016; Hoggett, 2019).

Psycho-social methods aim to explore the “dilemmas and conflicts that may inform practices and behaviours” (Lertzman, 2015, p.3), and not assume that research participants—or researchers—will always be cognisant of what or why they think and feel, or that these will be rational (Stenning, 2020). Within the interview and analysis, emotional reflexivity was developed through exploring the representation and expression of feelings (Bondi, 2005), with attention to what was beyond words such as pauses, intonation, changes of subject and laughter (Lertzman, 2015). My own emotional reflexivity was developed through using reflexive research questions and a research journal to bring attention to my feeling states and expectations before and after interviews, and my emotions connected to climate change during the period of research and analysis. This illuminated how my emotions changed over time (Gould, 2009), their influence on my climate change engagement, and helped identify potential interpretation biases.

Blending psycho-social and human geography methods enabled an exploration of participants' dynamic emotional relationships with climate change in the contexts of their lives, and in workshops, CSOs and workplaces. To acknowledge my role in the research, I have used the first-person perspective.

The psycho-social interview focused on the participants' motivations to participate in the WTR/AH or CLP, their experiences of the workshop/s, their emotions – and movement of emotions - relating to climate change, and their climate change engagement. It involved uncovering how climate change featured in their lives, and how participating in the CLP or WTR/AH influenced this. This required attention to the told, and untold, narrative of their biography, often revealed through the minor details and specific examples (Stenning, 2020). An appropriate psycho-social interview method was Biographic Narrative Interpretive Method, or “BNIM” (Wengraf, 2017).

The BNIM interview consists of two consecutive parts. In the first part a “single question aimed at inducing narrative” (or “SQUIN”)6 (Wengraf, 2017) was asked which focused on their participation in the WTR/AH or CLP. The participant responded in their own time without interruption, typically taking between 20 to 40 min (ranging between 5 to 90 min). They indicated the conclusion of their narrative and were invited to add anything further if they wished. The second part explored themes and narrative events they raised, according to my research priorities. The whole interview typically took between 1 ½ to 3 h.

Selection of Participants and Interview Methods

Research ethics were adhered to throughout. The informed choice to participate included an initial invitation, an explanation of how the research would be conducted, and a participant information sheet prior to the interview. Participants were reminded at the interview that they could choose not to answer or withdraw from the research, signed a consent form and were offered the opportunity to review the interview transcript and the summary of my interpretations.

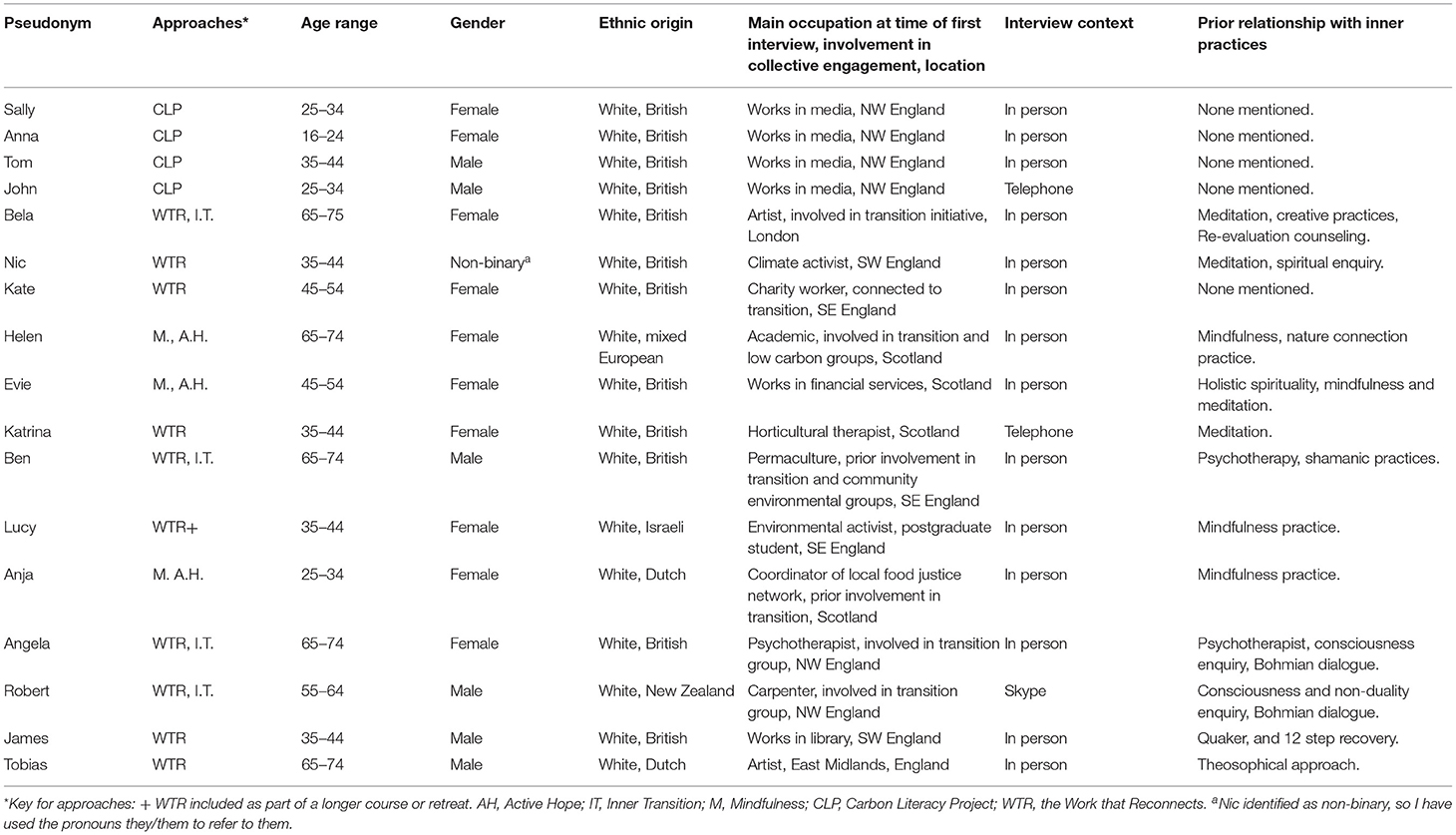

Seventeen participant interviews took place between November 2017–August 2018. Table 1 shows the biographical details of the participants and their locations. There was a large degree of homogeneity between the participants. All were racialised white and lived in England or Scotland. Three were born and raised in continental Europe, one in Israel, and one in New Zealand. All others were born and raised in the UK. All were able-bodied, and one was partially deaf. All but three participants were university educated, half of those to postgraduate level, and others had professional or vocational qualifications. The participants ages ranged from one in her early twenties to five who were over 65. Most WTR/AH participants had some form of contemplative or inner practice/enquiry, such as mindfulness.

Interpretation and Analysis

My interpretation and analysis drew from BNIM (Wengraf, 2017) and Free Association Narrative Interview methods (Hollway and Jefferson, 2000). I focused on the participant's relationship to climate change through their life narrative, emotions relating to climate change, experiences of participation in the WTR/AH and CLP, movement of emotions during and after the workshop/s, and climate change engagement. Common to psycho-social analysis (Hollway and Jefferson, 2000), I transcribed the interviews verbatim to include pauses, laughter, expressed emotions, verbal fillers such as “um”, and noted changes in the tone, pace, volume and expression of voice. My feelings and associations were noted during the interview and transcription.

I used thematic coding and clustering to analyse the participants' prior engagement with climate change, emotions related to climate change, push factors/motivations to attend workshops, workshop experiences, movement of emotions and impact on climate change engagement. I compiled 650–1,500 word summaries of the participant's biographical details, my key research themes (relationship with climate change and socio-ecological issues; motivations for attending and experience of participating in WTR/AH or CLP, impacts they attributed to participation, emotions connected to climate change and/or their workshop experience). I included areas of tensions or ambivalence, patterns of speech or non-verbal behavior, and aspects of their narrative with an emotional or affective charge. To aid my reflexivity, I noted my interpretations, reflections, any synergies with my own feelings, and questions to check my interpretation with participants.

I updated participants about my research around a year after their first interview, and invited them to review their transcription, check my interpretations, and reflect on changes relating to their engagement with climate change since I interviewed them. Nine participants responded, resulting in seven follow-up interviews and one email exchange. Those who responded offered reflections and feedback on their transcript, summary and my interpretations. I triangulated the participant analysis with my literature review and primary interview data with facilitators.

Results

Here I present the results of the participant research. I provide the context of the Carbon Literacy Project and Work that Reconnects, followed by Participants' prior engagement with climate change, and an overview summary of my key results which responds to the key RQ of “What is the role of emotional reflexivity in engaging with climate change”. I unpack this summary through the sections: Motivations and push factors to attend workshops; Workshop experiences, acknowledging and expressing emotions; and Movement of emotions and development of emotional reflexivity. This is followed by sections on Defenses and ambivalence; Relationship between emotional reflexivity and active engagement, and Resourcing and sustaining active engagement.

The results reflect the themes that emerged from the full analysis of all 17 participants, a summary of which is provided in Supplementary Table 1. In this paper I focus on grief and fear which appeared as key impediments to active engagement with climate change for the participants, and use longer excerpts from three participants to illustrate the themes. The participants are: Sally who participated in the CLP; Evie who participated in an ongoing Active Hope group; and Nic who participated in a series of WTR workshops at a festival.

Context of the Carbon Literacy Project and Work That Reconnects

The Carbon Literacy Project

The CLP was experienced through a day-long workshop for staff in a media broadcasting organization in north-west England. The organization had provided regular events, talks and themed weeks on climate change for staff. It uses a certification scheme to measure and reduce carbon emissions from production. In the six months prior to interviews, carbon reduction behaviors were included in the content of television and radio programmes.

The CLP learning day involved presentations and discussions delivered by a trained CLP facilitator, who also worked with the media organization. Tailored components focused on reducing the organization's carbon footprint and the opportunities for climate change engagement through programme content and accompanying websites. The CLP appeared to be the first opportunity within the workplace where participants had experienced sustained reflection and deliberation on climate change and considered personal and collective engagement within their team.

The four CLP participants all lived in the north west of England and all worked in the same team. Participant interviews took place in early 2018, around three months after participation in the CLP, during a period of heightened awareness of single-use plastics following a popular natural history television series.

The Work That Reconnects and Active Hope

Participants experienced the WTR and AH in a variety of voluntary contexts. These included: a series of workshops at a festival or conference; stand-alone workshops (which varied from a day or weekend workshop to WTR practices included in a two-week course to support and sustain forms of socio-ecological activism); and an ongoing AH and mindfulness book group. Eight participants had previous or ongoing involvement with their local Transition group. Of these, four were involved in Inner Transition groups.

Participants' Prior Engagement With Climate Change

All interviewees were concerned about climate change. My analysis, summarized in Supplementary Table 1, shows participants' engagement with climate change. I clustered the stages of engagement prior to participation in CLP or WTR/AH as initial – to denote those in the early stages of active engagement7, and ongoing – to denote those who referred to their participation in the WTR/AH or CLP within the context of ongoing individual (such as switching to more plant-based diets and reducing flying), and/or collective action through social-ecological CSOs.

The participants had varied experiences of the WTR/AH. At the first interview, these ranged from attending one workshop, to those who had participated in the WTR/AH in various ways for over 5 years. Most had ongoing forms of inner practices such as meditation and mindfulness, some of which were developed through involvement in WTR/AH.

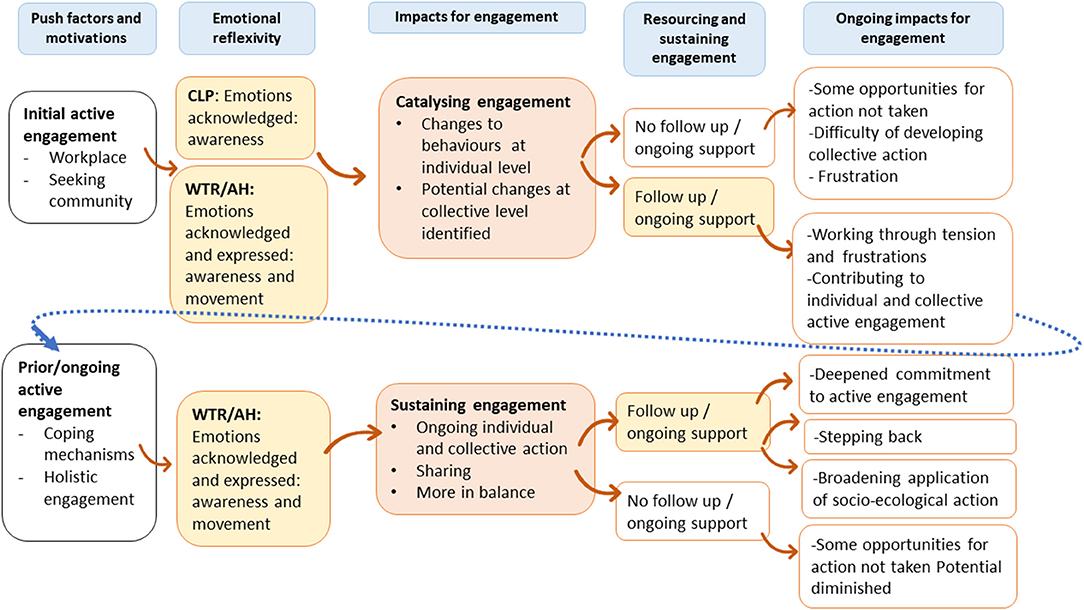

Summary of Results

To summarize the results, I present an overall schematic in Figure 1. This gives a simplified overview to highlight the relationships between the motivations/push factors to attend the CLP or WTR/AH, how emotional reflexivity was developed through acknowledgment and/or expression of emotions, the impacts for engagement, the implications of follow up support, and ongoing impacts on engagement. These stages are shown in the blue boxes at the top of the figure. The yellow shaded boxes demonstrate the spaces where emotional reflexivity was developed, and how this contributed to catalyzing or sustaining engaging with climate change. The orange arrows show the links between the different stages. This is not a linear or one-way process, as the right-hand dotted blue from the right to left hand side arrow suggests the movement from initial active engagement to ongoing active engagement.

Figure 1. Schematic showing how emotional reflexivity was developed through participating in the CLP or WTR/AH and the impact on active engagement.

Motivations and Push Factors to Attend Workshops

The range of motivations and push factors to participate in the CLP and the WTR/AH provide insight into how participants experienced climate change engagement prior to involvement. The workplace training was the key “push factor” for CLP participants. Sally reflected that she had:

“always been conscious of climate change … [but] had not had the science explained to me properly before”.

The motivations for voluntary participation in the WTR/AH, shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1, were:

1. A seeking of community as a route into active climate change engagement;

2. A coping mechanism for existing engagement with climate change and socio-ecological issues. Nic reflected they had “few skills around emotional stuff” (prior to participation), and needed a way to cope with information, the emotional toll, and remain actively engaged; and

3. A holistic engagement which combined socio-ecological engagement and inner enquiry.

For some, such as Evie, mindfulness was the foundation and her route-in to both the AH group and active climate change engagement:

“an exploration of my inner world … led to this feeling of connection, in terms of global problems and issues [laugh], it sort of was the catalyst … my engagement in climate issues has been completely colored by that aspect”.

These motivations illustrated what was missing or lacking in some CSOs: the opportunity to acknowledge the emotional dynamics of initial/ongoing climate change engagement. This included emotions connected to climate change, burnout arising from unsustainable active engagement, and the emotional dynamics of group processes such as conflict.

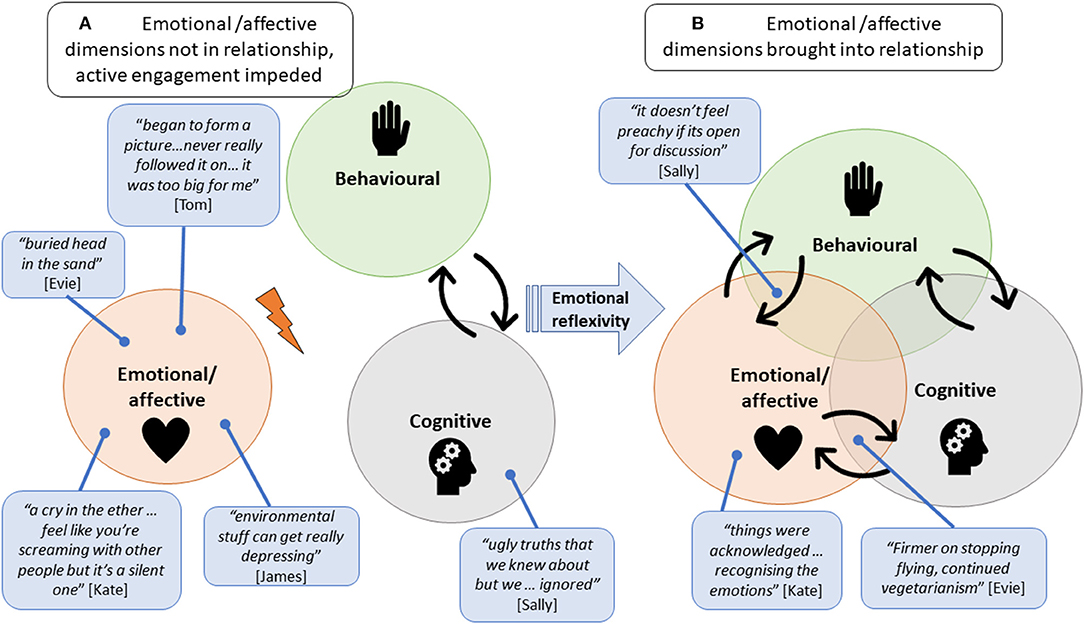

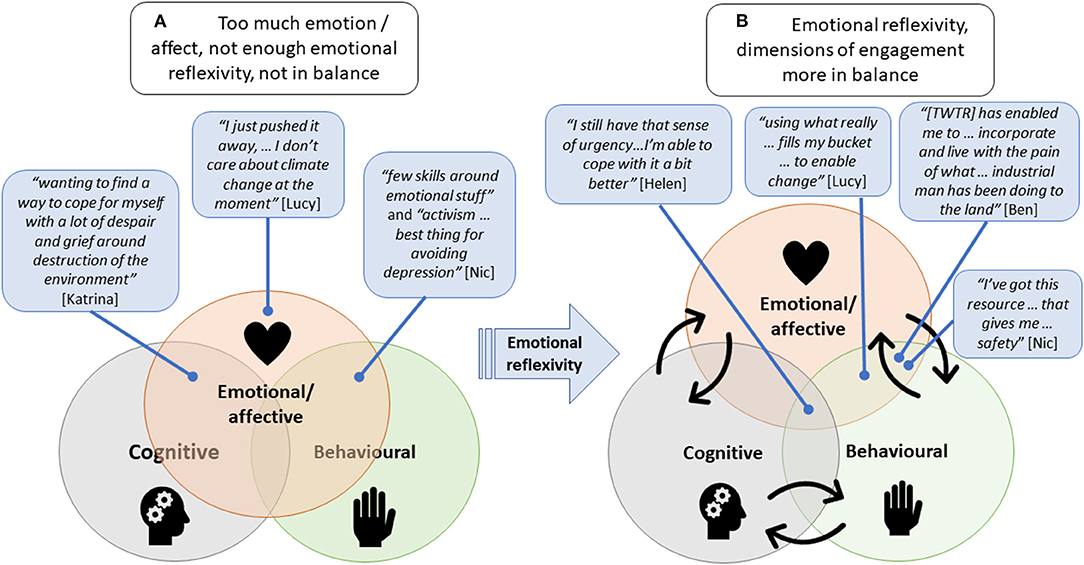

For most participants at initial stages of active engagement (CLP and the WTR/AH participants seeking community), a blockage or lack of connection was evident between the emotional/affective and the cognitive and behavioral dimensions of engagement (see Figure 2A). For those who were involved in ongoing active engagement and motivated to attend the WTR/AH as a coping mechanism, there appeared to be an insufficient capacity to process and work with an excess of emotion, which was dominating their cognitive and behavioral dimensions of engagement (see Figure 3A).

Figure 2. (A,B) Development of emotional reflexivity for push factors of workplace and those motivated by seeking community. Symbols: Heart: emotional/affective dimensions; Head: cognitive dimensions; Hands: behavioral dimensions; Arrows: feedback between the dimensions; Blue speech bubbles: quotes from participants;  Tension between the dimensions;

Tension between the dimensions;  Process of participation in the CLP or WTR/AH.

Process of participation in the CLP or WTR/AH.

Figure 3. (A,B) Development of emotional reflexivity for those motivated by coping mechanisms. Symbols: Heart: emotional/affective dimensions. Head: cognitive dimensions; Hands: behavioral dimensions; Arrows: feedback between the dimensions; Blue speech bubbles: quotes from participants;  Tension between the dimensions;

Tension between the dimensions;  Process of participation in the CLP or WTR/AH.

Process of participation in the CLP or WTR/AH.

Workshop Experiences, Acknowledging and Expressing Emotions

This and the following section present results relating to the RQ “How do emotions connected to climate change move and change”. I focus on the participant's overall experiences and how fear and grief related to climate change, followed by the movement of fear and grief in the Section Movement of emotions and development of emotional reflexivity.

Participating in the WTR/AH and CLP was a mainly positive experience for most participants. This does not mean the workshops were necessarily easy or comfortable. Analysis from all participants demonstrated their emotions connected to climate change. In the CLP, emotions were acknowledged, but not necessarily expressed or worked through as the CLP operated within a workplace context. In the WTR/AH, the focus and structure of workshops, combined with voluntary participation away from work and family enabled the acknowledgment and expression of emotions, and the movement of emotions was more evident.

The majority of emotions evident for all participants connected to the more negative/pessimistic emotions associated with eco-anxiety, such as grief, fear, anger, depression, hopelessness, sorrow, and guilt. When positive emotions such as hope, love and passion were mentioned, they referred more to the hopefulness and feelings of connection that emerged through becoming actively engaged, the love for the world having worked through grief, or the difficulty of sustaining passion. My analysis illustrates how the themes of grief and fear related to the degree of active engagement with climate change.

Fear

The main fear themes were fear about climate impacts, social disintegration and social isolation.

Sally's reflection of the “big scary nature” of climate change prior to the workshop related to her fear of the impacts of climate change: “it should be scary … the bigger picture stuff, I find it really depressing”. Related to this was her fear of the disintegration of social infrastructure and of losing a sense of common humanity:

“I have no question that humans will survive into the future … but, er, I hope it's not at the cost of our humanity. I hope that to survive, I hope that people do not start to see each other as different … it would be incredibly sad if, to get through the challenges ahead, people started to see each other as “the other” again… but I can see that happening already in how we treated Syrian refugees … who have every right to come and seek asylum, [laughs], but we wo not let them in. Um, [laughs], yeah, that's hard. And I think um, the, oh I can not remember what I was going to say”.

Her sudden stop of narrative flow in the excerpt alludes to fears that may be unbearable to consider or name. Toward the end of the interview she became aware of the frequency of her laughter, which appeared connected to overwhelming and unbearable thoughts and feelings. She reflected that “I'm laughing because it's terrible”.

Fears about the disintegration of social infrastructure were echoed by Evie, who – prior to participation in AH - wanted to distract herself from engaging with climate change. She recalled:

“it was not so much the climate change stuff that stays scary [laughs], but more about the, [pause] just sort of looking at human nature”.

The theme of risking social isolation when talking about climate change engagement - of seeming preachy, losing friends and changing social identity – emerged for those at initial active engagement. Evie expressed:

“there's that fear that if you change too fast, the people currently in your life will get confused … you do not want to lose those relationships … and you do not want to rock the boat by appearing too [pause], too different to how they have known you”.

Many of the reflections of fear recounted by participants contained fears of not feeling resourced enough to process the painful emotions of fear and grief prior to participation. For example, Helen reflected that “the Active Hope group was the first time I really felt I could combine my mindfulness practice with a work that really connected me to this pain and difficulties that … I had experienced”.

Grief

Grief appeared as a referent emotion. Love was enfolded within it; fear of loss or experiencing grief derived from it; and anger was one outward expression of it. Two of the grief themes that emerged in the analysis were the loss of lifestyle and expectations, and the loss of ecosystems, peoples and cultures, which connected to personal griefs from the participant's life stories.

The acknowledgment and expression of grief was positive for most participants. It involved a surfacing of feelings which had been hidden to them or had not been expressed with others. Griefs for loss of lifestyle and expectations were connected to behavior changes for climate mitigation. For those at initial stage of engagement, anticipatory grief concerning loss of lifestyle was apparent when considering giving up - or losing a guilt-free enjoyment of - aspects of their lifestyles they cared about and valued, such as foreign travel. For example, Sally reflected that:

“if someone were to say you can't, you can not go to the far East ever again … that would make me feel like, pfff, I would feel sad about that. I would grieve for that, because I like going to new places and doing new things”.

Alongside the anticipated grief connected to a loss of lifestyle, grief around the loss of expectations was articulated by two participants through considering whether or not to become parents in the light of climate change.

The acknowledgment and expression of grief for the loss of ecosystems, peoples and cultures was expressed by Nic, who reflected: “I just broke down in tears … talking about ecocide and the loss of biodiversity”.

The group context of the CLP and the WTR/AH enabled participants to recognize - and experience - the connections between themselves, their emotions, other participants and the more-than-human world. It counteracted the silence experienced when grief was felt in isolation.

Movement of Emotions and Development of Emotional Reflexivity

In this section I focus on how emotions connected to climate change moved and changed in the CLP and WTR/AH, and how this movement contributed to emotional reflexivity. Emotional reflexivity was developed in three ways across all the participants: (1) through a movement of emotions into consciousness; (2) through a changed relationship to painful emotions; and (3) through the transformation of emotions. These contributed to feedback between the dimensions of engagement, and influenced the carbon reduction actions of the participants. I present these in turn.

Reflexive Awareness of Emotions

A movement into consciousness enabled a reflexive awareness of emotions in the CLP and WTR/AH. Participants became aware of their emotions, their reactions – including defenses - to emotions, and how emotions influenced their individual and collective engagement.

For example, in Sally's reflection of the CLP she acknowledged her defenses of knowing about climate change, as the implications involved losing something she cared about, and her awareness of climate change being both absent (“you do not see enough”) and present (“you see so much”):

“I think there were definitely ugly truths that we knew about but we kind of ignored. Stuff like we like traveling a lot”, and “it's weird because you kind of don't see enough, but also you see so much that you kind of become a bit, um, blind to it”.

She also reflected on the difficulty of taking action in isolation, and staying with positive emotions, alongside the potential for collective action that emerged in the workshop:

“it's hard to envision any change in the future … it's hard to stay passionate or inspired to make change when you feel you can not make a big difference on your own. And you're not really aware of what other people are doing to make a difference” and “I had not really thought about the power that we have here”.

Sally's awareness of her grief, her defenses to knowing, and reconsidering her potential for action contributed to her making changes and taking action, as she reported that “me and my partner make a lot of active changes now… to reduce our footprint as much as we can” (Supplementary Table 1).

Evie reflected that her involvement in the AH group developed her awareness of her defenses against knowing and feeling about climate change:

“Before all this [mindfulness and AH] I was you know, [pause] sort of head, burying your head in the sand approach to things. Um, and to some extent that is still true … it feels [pause] very hard sometimes to hold that [laughs] … to not put it back in its little drawer. And, just say you know … life will go on … I don't want to think about it”.

Evie's awareness of wanting to compartmentalize her active engagement with climate change is evident with her phrase “to not put it back in its little drawer”. Her emotional reflexivity is apparent through her awareness of her ambivalences of wanting to know and not know about climate change, and her fears, yet is continuing with active engagement. For example: “I have gone vegetarian probably as a direct result of all of this” and “I would think twice now about going on holidays where I need to fly anywhere … I have not really gone … traveling by plane”.

For both Sally and Evie, emotional reflexivity was developed through awareness about emotions, and their defenses to the emotional implications of knowing about climate change. They are both aware of parallel stories (of knowing and not knowing), both acknowledge this is an ongoing tension, and this awareness has contributed to changes in their lives.

A Changed Relationship to Emotions

Emotional reflexivity that emerged through a changed relationship to painful emotions was evident through participants' descriptions of movement and turning toward emotions. Participant's phrases included dance-like qualities of “turning toward”, “turning to face”, “embracing” and “navigating”.

For example, Evie reflected how turning toward her fears made them more manageable and reduced fear:

“that sort of paradox of … opening up to the problems … lost a bit of their scariness when … turning to face them … That to me made things feel less, less scary … just the fact that if we do not talk about any of this stuff, it's not that it's not there … It's just that we are just shutting them away. You're sort of thinking that they're not affecting me … but they're there in your subconscious … the only way to um, logically sort of not let them, sort of, inveigle their way into your persona, in some sort of unconscious way, is to sort of somehow turn to them”.

Exploring emotions relating to climate change in a group context enabled participants to acknowledge the connections between how they and other participants felt about climate change. Participants became aware that many others knew, cared and were suffering with knowing about climate change. The realization that emotions were something that connected them to others, instead of being hidden away, decreased social isolation. Evie recounted “feeling that connection with those people”, and Nic reflected that they were,

“not alone in this time of converging crises, there's a whole bunch of people … they're all waking up each day knowing about the state of the world … and are wanting to do something about it. That felt really exciting … like “ah yeah, there's people, there's connection, it's like, we're not alone”.

The group context and connection with others provided a resource within which to acknowledge and develop a changed relationship to painful emotions, and develop capacities for being and working with grief and fear. The reflexivity developed influenced engagement through having greater capacity to be with and bear the painful emotions, both within themselves and collectively.

Transformation of Emotions

Emotional reflexivity through the transformation of emotions was apparent in the WTR, particularly through the more ceremonial exercises, where a strong container was held for the expression of emotions such as grief. This is illustrated in Nic's reflections of a WTR exercise for honoring pain and grief. Through expressing their emotions, the emotions were transformed, (in Nic's terms, “alchemized”), into a resource and catalyst to sustain their active engagement:

“Honoring our Pain. Um, probably one of the more powerful experiences … like in my life that I have had, was that workshop … there were bowls of water in the middle, and it was just half an hour or something, for people to go into the center, and express their, [chuckle] ah it's the tears coming now, um … so it was really helpful and really powerful for me to be able to go up and have space to express that … I mean I just broke down in tears, and I was talking about ecocide and the loss of biodiversity … but yeah, embracing that sorrow, but also being able to alchemize that into that sense of loss, and into that sense of passion and deep determination… in this space, I'd connected to a deep determination and passion to continue the work”.

Nic's tears that arose in the interview when recounting their experience gave insights into the depth and power of their experience, and how it impacted their subsequent actions. Nic later reflected that the deep determination and passion was their:

“resource, this tool… that gives me that feeling of safety” and “Yeah, feeling of safety that it's ok to feel the grief, it's OK to connect to that, because I know the way out of that, I know what to do with that, I can alchemize that now”.

Nic's term of alchemy serves as an example of the transformation - of loss and sorrow into passion - and a changed relationship to painful emotions as they had the resources to bear them, and they would not get stuck: they “knew the way out”.

Examples from other WTR participants (see Supplementary Table 1) illustrate how transformation of emotions was expressed in terms of movement. For example, anger was “turned around” (Bela), and “let out”, to enable a “moving on” (Ben).

Defenses and Ambivalence

Whilst becoming aware of defenses against climate change knowledge and feelings led to some emotional reflexivity, unresolved defenses and ambivalence were revealed which limited the degree of emotional reflexivity and active engagement. The conflicting polarities of being an “eco warrior” or “enemy of the state” (Tom, Supplementary Table 1) were apparent with three CLP participants at initial stages of active engagement. This demonstrates the internal vacillation and movement between the binary splits of good person/bad person, or all/nothing, which were unresolved after the workshop.

Sally reflected that behavior changes were “all or nothing, so it's kind of “right you have to kind of give up your car, and never fly again, and um become a vegan and make your own clothes, or you're just a bad person” and “it's odd because you find yourself being … such a hypocrite”.

These examples provide insight into the associations, conflicts and tensions associated with active engagement with climate change. Many participants at initial active engagement cited the “miserable” associations of low carbon lifestyles. They expressed this in muted, resigned or defensive ways, which illustrates how guilt or an unrealistically high standard of what active engagement involves impeded their active engagement.

For participants who were actively engaged in an ongoing way, the splits and tensions focused on how they engaged, typified by the polarities of doing (taking action) or being (practices to explore individual and collective emotions and group culture). For example, Nic reflected that in their life “activism, being active, feeling like I had a sense of meaning purpose and agency, and also an outlet for my creative energy, was the best thing I've found for avoiding depression”. Opportunities to explore emotions – and develop emotional reflexivity - and active engagement were held as opposites, even by people who had experienced the value and impact of emotional work, with an assumption of having to choose between them. This provides insights into the splits within socio-ecological movements, and the lack of spaces for integrating the inner and outer dimensions of socio-ecological engagement.

Relationship Between Emotional Reflexivity and Active Engagement

In this section I summarize how emotional reflexivity contributed to active engagement, in response to the RQ “What is the role of emotional reflexivity in engaging with climate change?

Alongside the examples provided in Sections Movement of emotions and development of emotional reflexivity and Defenses and ambivalence, Supplementary Table 1 illustrates the reported actions that participants attributed to the CLP or the WTR/AH, to show how movement of emotions enabled the development of emotional reflexivity and contributed to the participants making changes in their lives relating to active engagement with climate change. This is summarized in Figure 1 as catalyzing or sustaining engagement.

As illustrated in a simplified way in Figure 2, for those at initial active engagement, with the push factors of workplace or motivations of seeking community, the CLP and the WTR/AH provided an opportunity to become aware of blocks and tensions in the relationships between the emotional/affective and the cognitive and behavioral dimensions of engagement (Figure 2A). Participation in the CLP and the WTR/AH helped develop emotional reflexivity, by bringing the emotional/affective dimensions of engagement into relationship with the cognitive and behavioral dimensions through acknowledging how emotions impacted engagement (Figure 2B). The relationship between emotional reflexivity developed in the CLP and WTR/AH and engagement was to catalyze engagement.

For participants motivated to attend the WTR/AH as a coping mechanism, the development of emotional reflexivity enabled them to sustain engagement. As shown in Figure 3A, participants” emotional/affective dimensions were overwhelming their cognitive and behavioral dimensions of engagement. Through acknowledging and expressing emotions the WTR/AH enabled emotional reflexivity through developing awareness of how emotions and affects were impeding their engagement, creating different relationships to emotions, and transforming emotions, which brought the dimensions of engagement into balance. In Figure 3B, space and feedback was created between the dimensions of engagement. For some, this involved stepping back from the brink of burnout and stopping to rest, reflect and resource themselves.

For those who were motivated to attend the WTR/AH as a form of holistic engagement, the WTR/AH helped sustain their active engagement through acknowledging and expressing emotions. The development of emotional reflexivity provided ways to continue and support a balanced engagement.

By demonstrating how the motivations, experiences and development of emotional reflexivity related to active engagement the findings provide examples of the plurality of engagement pathways and opportunities for emotional reflexivity to influence active engagement. Using the examples of the WTR/AH and CLP, the role of emotional reflexivity has been to bring the dimensions of engagement into relationship, which has resulted in catalyzing or sustaining engagement. However, limits to maintaining emotional reflexivity and active engagement were apparent, which I address in the next Section Resourcing and sustaining active engagement.

Resourcing and Sustaining Active Engagement

Whilst the CLP workshop catalyzed an initial increase in active engagement, unresolved splits, ambivalences and tensions (discussed in Section Defenses and ambivalence) were revealed in participants, which impeded deeper engagement. CLP participants reported difficulties in taking collective action within the organization, that little time was given to revisit and follow up on intentions. In a follow-up interview, Sally reflected:

“I do not think anything's been fully followed up … That's why I joined XR [Extinction Rebellion], cos … I feel really angry, and this needs to happen now”.

She then reflected on a particular block to action she was experiencing within the organization:

“but then maybe actually it's been in front of me this whole time that actually I might be able to ask or push … or maybe I can just be persistent with it [laughs]”.

For the CLP and some WTR participants who were not connected to CSOs, the lack of opportunities to reflect on the workshops and forms of active engagement limited the post-reflexive choices available, when there was motivation to take both individual and collective action. Follow up interviews provided evidence that some had since got involved with CSOs. This illustrates the importance of providing follow-up opportunities, which include acknowledging the frustrations of wanting to act and reaching a limit or tension within an organization. For example, Sally's realization of her next steps occurred when reflecting on her intentions (in the research interview), which indicates spaces for reflecting and exploring could be done through peer-to-peer conversations.

The value of ongoing opportunities and practices was evident for participants who had integrated mindfulness and WTR/AH practices into their ongoing active engagement as a way of sustaining and deepening their engagement. In her follow-up interview, Evie described:

“I'm hoping there's a wiser part of me that's realizing that this is just part of this spiral of … uncovering layers and opening up to more, that it's not an easy process … I feel the need for some sort of recharge … to spin the plates a little bit again, to recharge some batteries, reminding myself of some deeper… if it was not for Mindfulness…I think I would be going crazy, really despondent about the world at the moment … Would I just have buried myself into the old business as usual and not let myself think about it? But I think that would have made me ill…” and

“the feeling of connection you get with a group in these sorts of situations … from my own personal experience, it buoys me up … in my normal life, I can engineer it that I retreat a little bit into a separateness, and I think that's a pattern I'm starting to notice. And it's so helpful for me to re-engage in a group”.

Nic reflected on the ongoing opportunities through the psychotherapy course they were currently pursuing, and through offering workshops to CSOs they were involved with that incorporated forms of the WTR.

These results suggest that for methods to develop emotional reflexivity to have maximum impact on resourcing and sustaining active engagement, they could be seen as gateways or entry points to ongoing emotionally reflexive practices and competencies to help sustain and deepen the practical and emotional aspects of engagement over time, at individual and collective scales.

In this section, using examples of the CLP and the WTR/AH, I have shown how emotional reflexivity was developed through the movement of emotions, and how this movement contributed to the development of emotional reflexivity through participants using their new-found awareness to make changes in their life, and/or sustain their active engagement. I have demonstrated the role of emotional reflexivity in climate change engagement by bringing the dimensions of engagement into relationship. In the next section, I discuss these results in relation to the literature.

Discussion

In this discussion I address the RQs of “how do emotions connected with climate change move and change?” by exploring the movement of emotions in Section on Awareness and movement of emotions, and the development of emotional reflexivity in Section on Grief and fear. This is followed by discussion of RQ “what is the role of emotional reflexivity in climate change engagement?” in the Section on Emotional Reflexivity. In the Section Impact of denial on reflexivity the case study approaches of the CLP and WTR/AH used in this paper are discussed in relation to the broader research field of inner transformations. Limitations and potential for future research are discussed in Sections Climate change engagement and emotional reflexivity and Relationship to inner transformations.

Awareness and Movement of Emotions

Acknowledging emotions enabled participants to develop awareness of the contours and shapes of their emotions, the impact their emotions had on their engagement, and that some emotions were shared and felt collectively. Acknowledging emotions in the workplace also countered – at least momentarily - the fear and risk of social isolation (Moser, 2016) that for some accompanied discussing climate change.

Workshops helped participants to disaggregate the emotional saturation of climate change, to explore how emotions connected to climate change and other aspects of their life. The CLP and the WTR/AH are examples of safe-enough spaces for participants to acknowledge their emotions and respond to Head's appeal of how to “articulate rather than suppress our emotions about climate change” (Head, 2020, p. 2), and the need for accessible safe spaces to explore emotional reactions (Lawrance et al., 2021, p.18). In particular, WTR/AH participants referred to such spaces helping them to develop the resources to hold and process emotions connected to climate change.

Grief and Fear

The participant examples illustrate how forms of “disenfranchised grief” (Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018, p. 275) were recognized and experienced. The acknowledgment of grief connected to the anticipated loss of lifestyle and expectations for CLP participants reinforces the need (highlighted by Lertzman, 2015, and Randall, 2009) to attend to how forms of grief influence becoming and sustaining engagement with climate change.

Whilst Cunsolo and Ellis (2018) suggest that ecological grief is more likely to be experienced by people living in areas at high risk of climate impacts, these results demonstrate that grief (for peoples, ecosystems and cultures) was also experienced by those with a relatively low risk of physically suffering severe climate impacts. The movement of grief – into consciousness by Sally and alchemized by Nic – enabled the participants to explore what their grief was connected to, to develop different relationships to it, and to transform grief into a resource.

This furthers the extant research (Randall, 2009; Lertzman, 2015; Head, 2016, 2020; Cunsolo and Ellis, 2018; Osborne, 2018) and provides examples that show how the generative and reparative potential of grief has been realized through the WTR/AH. The example of the WTR/AH provide evidence of how one-off or ongoing practices of grief - identified as needs by Cunsolo and Ellis (2018) and Head (2016) – supported participants to develop capacities to sustain engagement over time.

My analysis shows the participants' fears connected to a fear of loss, directly from the impacts of climate change, and indirectly through social disintegration or social isolation. Evident in both the CLP and WTR/AH, fears and risks of social isolation were addressed through providing spaces to talk about climate change with others.

For WTR/AH participants, fears about climate change moved through turning to face them. Whilst fear in the absence of a means to process it can inhibit engagement (O'Neill and Nicholson-Cole, 2009), acknowledging fears that were present contributed to a reflexive exploration. My research responds to Pain's question of “how do self-conscious and self-critical experiences of fear inform ground-up processes of change” (Pain, 2009, p.480) by giving examples of how participants acknowledged and explored their fears and became actively engaged. For some, fears about climate change were descaled to fears about society – which could be at least partially addressed through participating in the WTR/AH and CLP.

These examples of grief and fear show how the movement of turning toward and expressing these painful emotions enabled a changed relationship, and provides some answers to the research question of how do emotions connected to climate change move and change? The grief or fear did not necessarily disappear but was not defended against as participants had more resource to work with their feelings (e.g. mindfulness practices and group resources), and they no longer impeded active engagement with climate change.

This evidence shows that the approaches of the WTR/AH and CLP helped participants develop emotional reflexivity, in response to the RQ “what approaches could help develop emotional reflexivity around climate change?” It provides valuable insights into how particular emotions – and what they relate to - influence engagement. It highlights the importance of disaggregating more general terms such as “eco anxiety” and reinforces the need to attend to how these emotions are experienced in different contexts, at different stages of engagement and how they relate to life stories.

Emotional Reflexivity

These findings show how emotional reflexivity was developed by participants in the CLP and the WTR/AH, and its relationship to participants becoming and remaining actively engaged with climate change. How the movement of emotions – and relationship to emotions – contributed to emotional reflexivity has added a spatial dimension to King (2005) and Brown and Pickerill (2009) conceptualization of emotional reflexivity. My findings have responded to King (2005) and Brown and Pickerill (2009) questions to show how development of emotional reflexivity relates to both initial active engagement and sustaining ongoing engagement with climate change.

Burkitt's assertion of emotional reflexivity that includes “practices of the self that reflect on habit or habitual emotional patterns and responses” (Burkitt, 2012, p.470), is illustrated by the full findings, and demonstrated by Evie, Sally and Nic's reflections and changes to their behaviors, practices and emotional responses. These findings provide examples of how reflexivity enabled participants to ““look at” rather than “look through” one's beliefs and to question what is socially or culturally given, rather than to consciously or unconsciously accept them as filters through which the world is viewed” (O'Brien, 2018, p.156), and enact a deep leverage point for change (Meadows, 1999).

The results show how the group and relational contexts of the CLP and WTR/AH contributed to the development of emotional reflexivity through participants interpreting both their “own and other's feelings about [their] circumstances” (Holmes, 2015, p. 61). The results illustrate how “externally mediated knowledge” (Burkitt, 2012, p. 469) from the groups influenced the participants to both acknowledge their own and others emotions, and for some to experience connection to a larger collective.

The results also illustrate that reflexivity on its own is insufficient to develop and sustain active engagement if the context and/or habitus does not support opportunities to put intentions into action. This reinforces Norgaard (2011), Adams (2006) and Gould (2009) who urge attention to how social contexts and habitus influence both the development – and maintenance - of reflexivity, and post-reflexive choice. This has important implication for CSOs to attend to the emotional dimensions of climate change engagement, and to provide ongoing opportunities to work through cultural, emotional, institutional, or technical challenges to engagement over time.

Impact of Denial on Reflexivity

With regard to the productive potential of working through emotions, Head asks “what are the constraints on that potential being realized?” (Head, 2016, p. 77). Such constraints are evidenced in the results through forms of denial such as disavowal (as discussed in relation to Weintrobe, 2012; Lertzman, 2015; Adams, 2016). Processes of splitting and unconscious defenses were evident, to protect the participants from uncomfortable information and a protection to the identity threats of being a “bad person” (Weintrobe, 2012; Lertzman, 2015), trying to retain a “good conscience” (Norgaard, 2011), or an unrealistically high standard of activism (Bobel, 2007).

By showing how unacknowledged and/or unprocessed emotions associated with loss of lifestyle, expectations and possibility have blocked more ambitious carbon reduction, these findings add a UK perspective to further Lertzman (2015) emphasis on attention to how people experience tensions, double binds and ambivalences. This research illustrates how the vacillation between polarities contributed to defense and denial. It also shows how defenses prevented the participants from exploring these uncomfortable paradoxes of privilege (Norgaard, 2011) which might result in changes to lifestyles (such as foreign holidays) that they were attached to. It implies that loss of lifestyles and expectations need to be acknowledged and grieved, alongside opportunities to explore and reflect on what constitutes a “good life” (Randall, 2009). It evidences that the lack of opportunities to acknowledge such dilemmas within organizations can be seen as forms of “defensive routines” that undermine collective effort (Mnguni, 2010, p. 118).

Climate Change Engagement and Emotional Reflexivity

My research and analysis illustrates how emotional aspects of engagement differed according to the degree of pre-existing engagement. It reinforces Randall (2009), Lertzman (2015), Moser (2016) and Head (2016) by illustrating how active engagement – at all stages - was impeded by a lack of opportunity to acknowledge and work through the attendant emotions, dilemmas and unconscious processes connected to climate change.

Responding to the RQ of the role of emotional reflexivity in climate change engagement, by exploring how emotions connected with climate change move and change, I have shown how emotional reflexivity helped bring dimensions of engagement into a generative relationship, and added a dynamic perspective to the complex relationships between dimensions of engagement (Lorenzoni et al., 2007; Whitmarsh and O'Neill, 2011; Moser, 2016). However, this engagement model does not include contextual influences such as political and socio-technical constraints to potential changes, and organizational cultures which influence if and how emotional and affective dimensions are acknowledged, denied or processed. This suggests the need to expand engagement models to include and explore such interactions, such as the four-quadrant framework from Wilber's integral theory (Wilber, 2000 in Ballard et al., 2010; Ives et al., 2020), and to examine the movement and interactions between the dimensions of engagement over time.

The research attests to the importance of critical reflection on dominant modes of climate change engagement and reinforces the need for a plurality of engagement modes and routes into active engagement with climate change (Lertzman, 2015; Moser, 2016). It responds to the research gap of how to acknowledge and work through the emotional and affective tangles, dilemmas and anxieties connected to climate change (e.g. Hobson, 2008; Lertzman, 2015; Head, 2016; Moser, 2016), and the generative potential of doing so. It suggests that the emotional/affective aspect of engagement is not just a “nice to have”, but a core component of active engagement for some. It reinforces a need to attend to practices and opportunities to develop emotional reflexivity within social change movements and organizations (King, 2005; Brown and Pickerill, 2009; reinforcing Andrews, 2017), and to pay attention to emotional habitus (Gould, 2009). Examples of such approaches exist [e.g. the psycho-social informed engagement of Project Inside-Out (2021)]. The research underscores the importance of the context and emotional habitus of workplaces and CSOs as places where collective active engagement can occur. This need not be limited to citizen engagement though, as Wamsler et al. (2020) evidence opportunities to explore inner dimensions of climate change with policy makers.

In coming years, the urgency of mitigating against even more dangerous emissions scenarios alongside responding and adapting to impacts already locked into the climate system in just and equitable ways will increase, and engagement approaches for the long haul (Buzzell and Chalquist, 2015; Moser, 2016) will be tested to the full. The research provides evidence of the important role that emotional reflexivity has in bringing the dimensions of engagement into greater balance.

Through the case studies of the CLP and WTR/AH, this research provides evidence how emotional reflexivity contributes to climate change engagement for the long haul that integrates and explores the painfully present impacts and contributes to equitable responses.

Relationship to Inner Transformations