- 1Department of Physical and Environmental Sciences, University of Toronto Scarborough, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Institute of Environmental and Interdisciplinary Science, Faculty of Science, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 4School of Public Policy and Administration, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 5Department of Geography and Planning, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

There is a growing body of literature that examines the role of affect and emotions in climate change risk perception and risk communication. Conceptions of affect and emotions have differed according to theoretical perspectives and disciplinary orientations (e.g., sociology of risk, psychology of risk, climate science communication), but little has been done to map these differences. This perspective article provides an in-depth analysis of the study of affect and emotions in climate change risk research through a literature review of studies published in the last 20 years. In this perspective, we examined how affect is conceived, what emotions have been considered, and their role in climate change risk perception and risk communication. Early studies in climate risk perception and risk communication included vaguely defined emotions (e.g., negative and positive) in climate risk perception and risk communication studies, more recently turning attention to how different affective dimensions interact with other factors, such as personal experience, knowledge, culture and worldviews, gender, and social norms. Using this review as a mapping exercise of the research landscape on affect and emotions in climate risk perception and communication, we suggest that future research could benefit from more interdisciplinary work that explores the role of different affective responses and their intensities before, during, and after climate-related events.

Introduction

Emotions and feelings—as affective responses to external stimuli or the imagination—reveal truths, create knowledge, and raise awareness about matters of concern to individuals (Furtak, 2018). A growing body of scholarship shows that affective responses—negative or positive—influence how risks are perceived (Finucane et al., 2000; Slovic, 2000, 2010; Mary Kate et al., 2018) as well as the effectiveness of the transmission and reception of the communication of risks (Slovic, 2010). Risk perception and risk communication are deeply connected to emotions and experience. Affective responses are increasingly recognized as an essential part of risk perception and risk communication by interacting with knowledge (Furtak, 2018), personal experience (Van Der Linden, 2014), social norms (Du Bray et al., 2019), and gender, among other factors; however, the specific role of affect in risk perception and risk communication is still not well-understood.

Studying affective responses in risk perception and risk communication is particularly important in climate change action. The impacts of climate change, which are distributed unequally across the planet, have become visible through floods, droughts, wildfires, heat waves, vector-borne diseases, and sea level rise, among other impacts. Scholarship on the role of emotions and feelings has shown that affective responses influence the judgment of risks and decision-making by individuals and communities, which may ultimately influence climate change actions (Slovic, 2000, 2010; Slovic et al., 2004; Finucane and Holup, 2006). The intensity and frequency of climate-related events are predicted to increase in the absence of substantial and transformative climate change mitigation (Mckenna et al., 2020), therefore, it is crucial to understand the role of affective dimensions in climate change risks perception and how to better communicate climate risks with different audiences.

Previous literature reviews have focused on single climate change impacts (e.g., floodings) (Bubeck et al., 2012) or on a single region (e.g., United Kingdom) (Taylor et al., 2014); however, no literature reviews have examined affect in risk perception and communication related to a broader range of climate change impacts. This perspective study presents the results of a review of forty-two articles from the last 20 years that study affective responses to climate change impacts in terms of risk perception and risk communication, guided by the following research questions: How are affective responses studied in climate change risk perception and risk communication research? And what role does affect play in risk perception before, during, and after a climate event? We identify trends, debates, and opportunities to better understand the role of affective responses in risk perception and communication of climate events1.

Literature Review

Meanings and Understandings of Affect

A variety of theoretical frameworks have been developed to understand the role of affective responses in risk perception and risk communication. We found that emotional responses were mostly studied following a “risk-as-feelings” interpretation (Zaalberg et al., 2009; Van Der Linden, 2014; Vasileiadou and Botzen, 2014). This perspective holds that, in low intensity situations, feelings play a minor role in risk perception, but in highly intense situations, emotions can take priority over cognitive responses to risk. The affect heuristic takes a different view–that emotional responses are immediate and automatic. In climate change research, the affect heuristic was used to explore how positive or negative emotions and feelings guide people when judging risks (Van Der Linden, 2014; Lefevre et al., 2015; Ekholm and Olofsson, 2017; Mol et al., 2020). Fewer studies used “risk information seeking and processing” (RISP) models to explore how affect influences information seeking behaviors in risk perception (Terpstra et al., 2014; Yang and Zhuang, 2020). Studies of affective dimensions in risk communication relied on affective imagery to investigate positive and negative emotions triggered by images, sounds, ideas, and stories which evoke judgment of a perceived risk (Lorenzoni et al., 2006; Smith and Leiserowitz, 2012; Thaker et al., 2020). It is notable that many studies did not explicitly follow a specific theory of affect despite the growing number, diversity and contrasts between different theories of affect (Furtak, 2018).

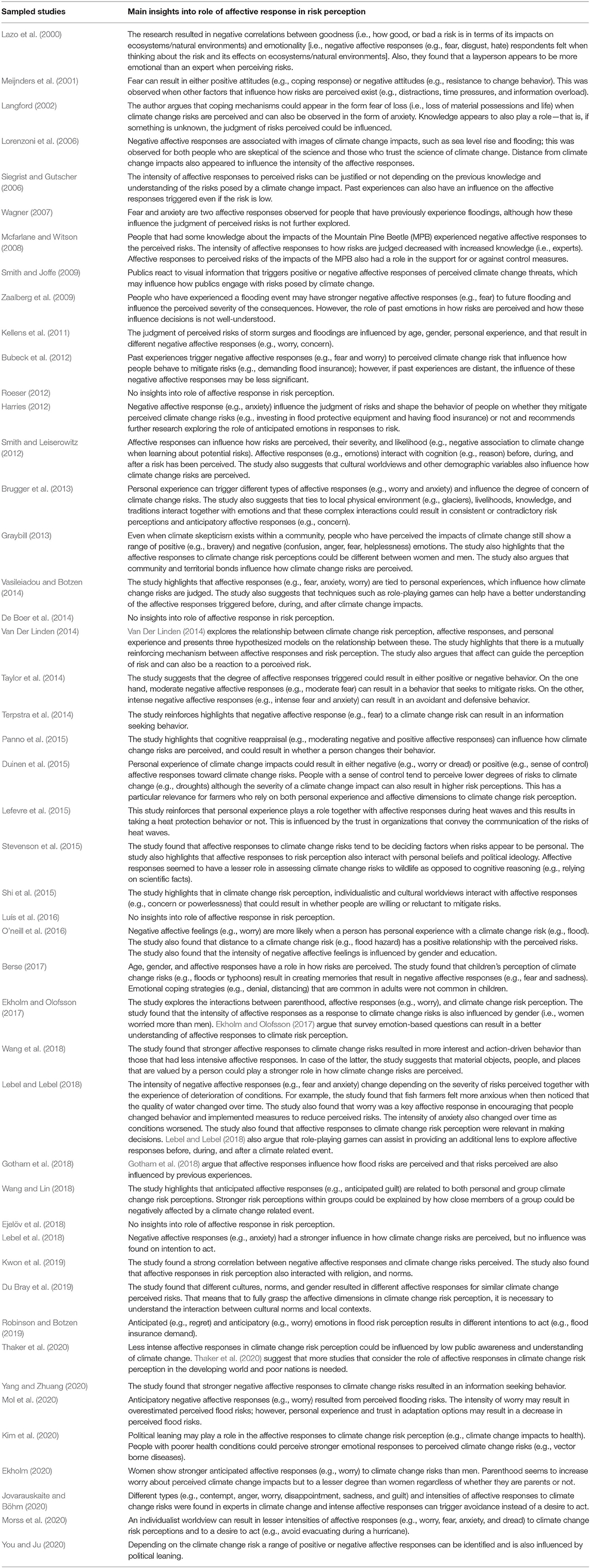

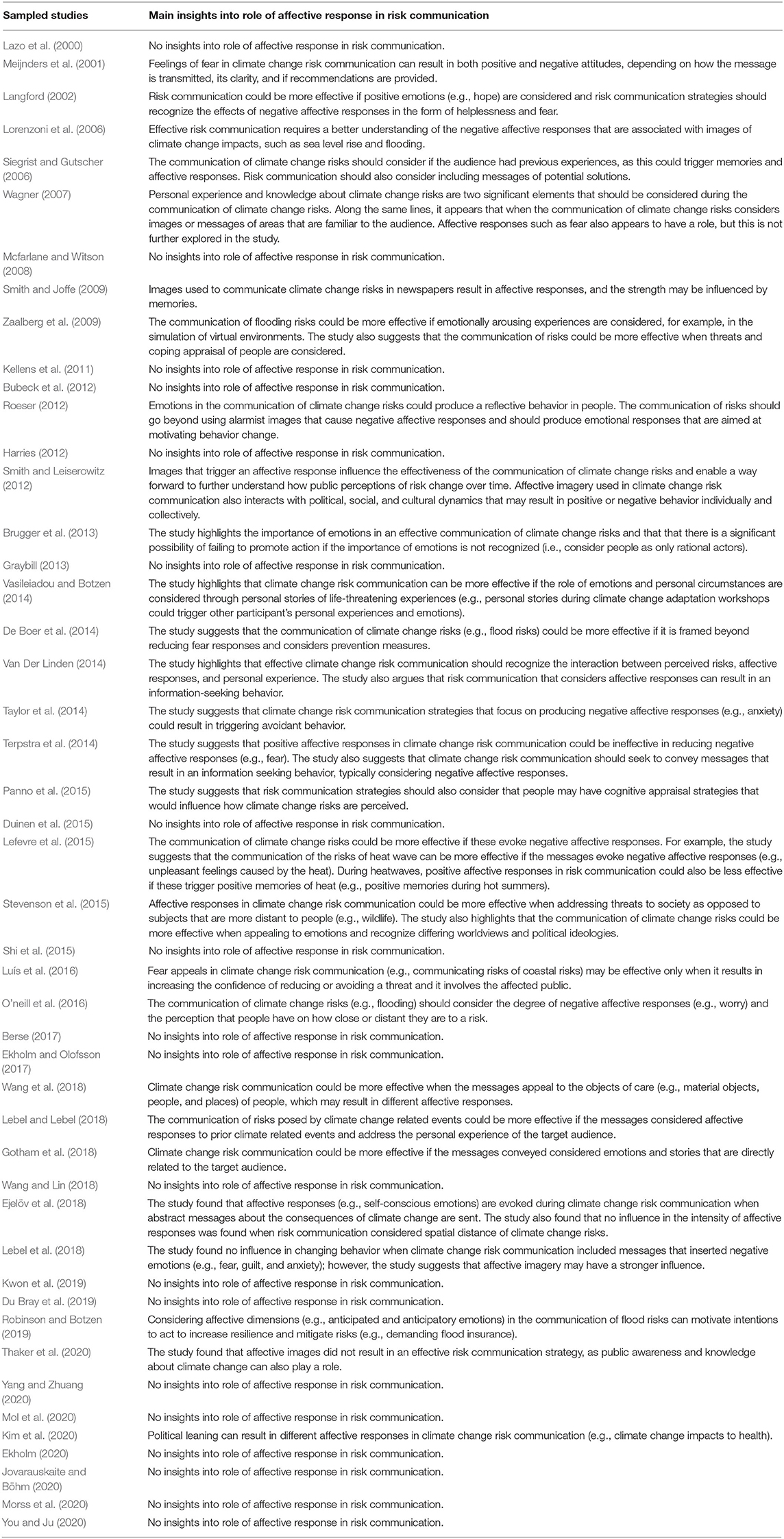

Table 2. Main insights into the role of affective responses in risk communication by sampled studies.

Polarity, Intensity, and Dimensions of Affect

In recent years, there has been a shift in how studies of climate risk perception have approached the subject of affect. Earlier studies tended to refer only to negative and positive affective responses. Over time, different positive and negative emotions, including fear and anxiety, started to be elicited in studies but were not typically a primary focus. More recently, a small but growing number of studies have focused on disaggregating negative and positive responses into specific emotions and feelings (Graybill, 2013; Jovarauskaite and Böhm, 2020). Fear, anger, worry, and anxiety were among the most studied affective responses in our review. For example, Graybill (2013) found that positive (e.g., bravery) and negative (e.g., confusion, anger, fear, helplessness) emotions were shown in response to climate change threats even when climate skepticism was a factor.

There were similar findings related to risk communication. Meijnders et al. (2001) found that affect can result in positive or negative attitudes toward climate risks, depending on how messages are delivered and what information is provided. Among different affective responses, fear has captured the greatest attention (Meijnders et al., 2001; Wagner, 2007; De Boer et al., 2014; Terpstra et al., 2014; Luís et al., 2016; Lebel et al., 2018). Using qualitative data from a case study of climate change in Norwich, U.K., Langford (2002) argued that risk managers should be aware of fear in individuals so that risk communication strategies allow individuals to understand existing risks and coping mechanisms, although the study does not say how this could be done. Appeals to fear appear to succeed in motivating people to protect themselves from climate risks only when they increase confidence that proposed actions can mitigate the risks of a threat (Luís et al., 2016). By contrast, positive emotions (e.g., hope) achieve better results in conveying clearer messages (Langford, 2002) but only when motivating information-seeking behavior (Terpstra et al., 2014; Van Der Linden, 2014) or providing clear actions to mitigate risks (De Boer et al., 2014).

The intensity of affective responses of perceived climate change risks can result in contradicting behaviors (Taylor et al., 2014). For example, Meijnders et al. (2001) found that fear in a lesser intensity can result in a positive attitude (e.g., a coping response) while more intense fear can produce negative attitudes (e.g., resistance or avoidance). However, others found that stronger negative affective responses could result in positive behavior (e.g., seek information to mitigate risks) (Yang and Zhuang, 2020). Similarly, Terpstra et al. (2014) found that negative affective responses (e.g., fear) can result in information seeking behavior. Other studies indicate that fear could have different forms (e.g., loss of life, loss of material possessions) and that different coping mechanisms can result from these affective responses (Langford, 2002).

A few studies disaggregated affective responses according to temporal characteristics (i.e., anticipatory and anticipated affective responses) (Robinson and Botzen, 2019; Mol et al., 2020). Robinson and Botzen (2019) argued that actions to mitigate risks (e.g., acquiring flood insurance) can be influenced by either anticipated (e.g., to avoid regretting future uninsured flood losses) or anticipatory (e.g., worrying about flooding) emotions. Similarly, Harries (2012) found that anticipatory affective responses to climate risks, such as worrying about flooding, influences intentions to mitigate perceived risks (e.g., investing in flood protective equipment).

Individual-Level Factors

Personal Experience With Climate Impacts

Experience appears to play a significant role in the intersection of risk perception and affect. Personal experience may result in negative (e.g., worry or dread) or positive (e.g., sense of control) affective responses toward climate change risks, which also influence the degree to which a risk is perceived (e.g., severity and chances of a flooding) (Duinen et al., 2015). Fear, worry, and anxiety were found to be common responses of people who have had personal experience with climate change impacts (e.g., flooding, heat waves) (e.g., Wagner, 2007; Zaalberg et al., 2009; Kellens et al., 2011; Vasileiadou and Botzen, 2014; Lefevre et al., 2015). Bubeck et al. (2012) review of flood risk literature highlighted that the amount of time passed since a climate event was an important factor in how affect relates to risk perception. The negative emotional influence of flooding events on risk perceptions diminishes over time, implying that emotional responses are likely to be less significant for events in the distant past.

Van Der Linden (2014) highlighted that there is a mutually reinforcing mechanism between personal experience, risk perception, and affective responses; affect can guide the perception of risks but can also be a reaction to risk. Only one study highlighted that personal experience of children with typhoons or floods created memories that shaped affective responses (e.g., fear, sadness) and guided risk perceptions (i.e., coping mechanisms) (Berse, 2017). However, most studies did not explore whether affective responses were guiding, or reacting to, the perception of climate change risks.

Lay People vs. Experts

The intensity of affective responses in risk perception have been observed to differ between climate change experts and laypeople. Lazo et al. (2000) found that laypeople showed more intense emotions than experts when perceiving climate change risks. Contrastingly, Jovarauskaite and Böhm (2020) found that experts tended to show more intense negative emotions (e.g., disappointment, sadness, guilt) to climate change impacts than laypeople. Experts experience diverse negative affective responses to perceived climate change risks including contempt, anger, worry, disappointment, guilt, and sadness (Jovarauskaite and Böhm, 2020). Negative affective responses (e.g., fear) were common in laypeople, who, in some cases, tended to overestimate the potential risks (e.g., flooding) (Siegrist et al., 2006). Siegrist et al. (2006) argued that lay risk perceptions depend on personal experiences, which could explain why affect plays a prominent role. Others found that personal experiences also interact with the affective responses to perceived risks, which could explain these contrasting findings (Van Der Linden, 2014). Mcfarlane and Witson (2008) suggested that increased knowledge may decrease the intensity of affective responses when judging risks, as knowledge reflects a better understanding of the risks.

Societal-Level Factors

Culture and Worldview

Affective responses to risk perception and communication can be shaped by different cultures and worldviews. For instance, belief in the inevitability of climate events, or about the role of individuals in addressing climate change result in different emotions: fear that harm will come to oneself, anxiety about the future, helplessness, or anger are tied to what individuals believe the situation to be and socially appropriate emotional responses are. Shi et al. (2015) found that individualistic and cultural worldviews interact with affective responses (e.g., concern or powerlessness). Similarly, Morss et al. (2020) found individualistic worldviews resulted in lower intensities of affective dimensions to climate change risks and decreased desire to act (e.g., evacuate during a hurricane). People who are close to a person or community (i.e., collectivist cultures) impacted by a climate change-related event tended to show stronger affective responses and risk perceptions (Wang and Lin, 2018). Territorial and community bonds have also been shown to influence people's affective responses to perceived climate change risks and their desire to act (i.e., social resilience) (Graybill, 2013). These studies show that individualistic and collectivist worldviews influence affective responses to the perceived climate change risks and intentions to act but do not articulate how findings can be applied to risk communication strategies.

Gender and Family Norms

Gender is a recurring focus in literature on affective dimensions of climate risk perception (e.g., Kellens et al., 2011; Berse, 2017; Ekholm and Olofsson, 2017; Lebel and Lebel, 2018; Du Bray et al., 2019). One study found that men tend to express different emotions than women (e.g., anger instead of sadness) (Du Bray et al., 2019). Du Bray et al. (2019) also found that cultural gender norms influence which affective responses are evoked against the same climate change risk (e.g., men from Cyprus tend to express emotions of anger whilst men in Fiji did not) as this can be driven by gendered expectations of what is acceptable for men and women. O'neill et al. (2016) found that women tend to show more negative anticipatory affective responses (e.g., worry) to floods than men. Gotham et al. (2018) argued that climate change risk communication strategies should consider gender dimensions as they may influence the transmission and reception of the information.

Two studies focused on exploring the role of parenthood in risk perception (Ekholm and Olofsson, 2017; Ekholm, 2020). Ekholm and Olofsson (2017) found a close tie between affective responses, parenthood, and risk perception. Ekholm (2020) added a gender lens to parenthood, finding that the intensity of negative affective responses (e.g., worry) in men, changed depending on whether they were parents or not; however, this difference was not observed in women. Studies that focused on gender, culture, and social expectations show that these can result in different affective responses to climate risk perception; however, most studies did not provide how this should be considered in risk communication strategies.

Communication Strategies

There was widespread recognition in the literature that better understanding the role of affect can improve communication about the risks of climate change impacts (Meijnders et al., 2001; Lorenzoni et al., 2006; Zaalberg et al., 2009; Smith and Leiserowitz, 2012; Brugger et al., 2013). Risk communication strategies could be more effective in educating the public on hazards when messages trigger memories of negative emotions from personal experiences of target audiences (e.g., communities, students, vulnerable groups) (Wagner, 2007; Vasileiadou and Botzen, 2014). Gotham et al. (2018) found including stories directly related to the target audience helps in spreading knowledge about climate risks. Similarly, Lebel and Lebel (2018) found that messages were more effective when personal experiences of target audiences were considered alongside affective responses to previous climate events.

Another body of scholarship has shown that using images to elicit emotional responses on climate change impacts could increase the influence of risk communication on behaviors (Lebel et al., 2018). Visual information can trigger both positive and negative responses to perceived climate threats by creating and prompting memory responses, which could be useful when studying decision-making and designing communication strategies (Smith and Joffe, 2009; Lebel et al., 2018). One study found that people had negative responses when shown images of flooding and sea level rise, regardless of whether they were skeptical about the causes of climate change (Lorenzoni et al., 2006). Another study found respondents in India had lesser negative emotional responses to climate change affective imagery; a lack of knowledge and awareness of climate change risks could potentially explain these findings (Thaker et al., 2020). Affective imagery used in climate change risk communication can also trigger memories that result in preventive behavior (Siegrist and Gutscher, 2006; Smith and Joffe, 2009; Lefevre et al., 2015).

Discussion

Two decades of research have shown that affective responses influence the judgment of risk perception to and communication of climate change risks. Our review suggests that a wide range of positive and negative affective responses play an important role in climate risks' perception and can enhance or hinder communication of climate risks. The research reviewed also shed light on the different dimensions of affect. For example, negative affective responses can take a wide variety of forms including fear, anger, anxiety, regret, guilt, sadness, helplessness, and each can result in different behaviors toward perceived climate risks and the communication of climate risks. Research in this area has also shown that beyond identifying the positive and negative affective responses, the intensity of emotional responses influences the judgment of risks and reception of climate risk communication.

There are complex interactions occurring between multiple factors influencing climate risk perception and risk communication, including personal experience, knowledge, gender, worldviews, social norms and time. Following the thoughts of Finucane et al. (2003), there is indeed a complex dance between affect, risk perception and risk communication, and these factors. Ignoring these complex interactions can impair efforts to protect people from climate change impacts. Given the importance of affective dimensions in risk perception and communication, future research should continue to develop more nuanced analyses of affective responses in how individuals and communities respond to climate risks.

There remain several critical gaps in the literature that warrant reflection and further research. That most of the studies we reviewed focus on the Global North is problematic in generating theory on affect and climate risk perception and communication. For example, Thaker et al. (2020) found that existing frameworks developed in the Global North could not adequately explain affective responses in India. This is particularly important, as people in the Global South are disproportionately experiencing the impacts of climate change. Studies of affect have shown emotions and feelings assist in the judgement of risks and in anticipatory action, thus, we suggest future research focus greater attention on the Global South.

Whilst studies recognize different emotions, the relative weight and intensity of these emotions in risk perception is still not well-understood, nor is it clear how factors such as gender and culture should be accounted for in risk communication. There is also some ambiguity in what it means for communication to be effective in the context of climate risk assessments. Future research could explore how different affective responses influence risk communication strategies and what happens when the intensity of positive and negative affective responses change.

The influence of time in affective responses for both risk perception and risk communication is also not well-understood. Individuals and communities that have had previous experiences with climate-related events could perceive different affective dimensions—and intensities of affective responses—at one point in time, but whether these change over time is not well-established. A valuable area for future research could involve exploring the role of affective responses in risk perception before, during, and after a climate-related event. Similarly, to what extent affect is mediated by proximity in social relations and geography to people and places that have experienced severe climate events is an open question.

The landscape of affective research on climate risk perception and communication is evolving, particularly as climate risks become a reality. We propose these preliminary research questions as important gaps to address in future studies of the affective dimensions of climate risk perception and communication.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

NK and RS contributed to conception and design of the study. RS performed the literature review, data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RS, NK, and VB wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to regular discussion of manuscript content and directions, analysis of findings, manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from Canadian Wood Fiber Centre - Forest Innovation Program with the grant number CWFC2023-002. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2021.751310/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The literature review methodology is described in the Supplementary Material of this perspective study, and the main insights of the review are presented in Tables 1, 2.

References

Berse, K. (2017). Climate change from the lens of Malolos children: perception, impact and adaptation. Disaster Prev. Manag. 26, 217–229. doi: 10.1108/DPM-10-2016-0214

Brugger, J., Dunbar, K. W., Jurt, C., and Orlove, B. (2013). Climates of anxiety: comparing experience of glacier retreat across three mountain regions. Emot. Space Soc. 6, 4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2012.05.001

Bubeck, P., Botzen, W. J. W., and Aerts, J. C. J. H. (2012). A review of risk perceptions and other factors that influence flood mitigation behavior. Risk Anal. 32, 1481–1495. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01783.x

De Boer, J., Wouter Botzen, W. J., and Terpstra, T. (2014). Improving flood risk communication by focusing on prevention-focused motivation. Risk Anal. 34, 309–322. doi: 10.1111/risa.12091

Du Bray, M., Wutich, A., Larson, K. L., White, D. D., and Brewis, A. (2019). Anger and sadness: gendered emotional responses to climate threats in four Island nations. Cross Cult. Res. 53, 58–86. doi: 10.1177/1069397118759252

Duinen, R. V., Filatova, T., Geurts, P., and Veen, A. V. D. (2015). Empirical analysis of farmers' drought risk perception: objective factors, personal circumstances, and social influence. Risk Anal. 35, 741–755. doi: 10.1111/risa.12299

Ejelöv, E., Hansla, A., Bergquist, M., and Nilsson, A. (2018). Regulating emotional responses to climate change–a construal level perspective. Front. Psychol. 9:629. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00629

Ekholm, S. (2020). Swedish mothers' and fathers' worries about climate change: a gendered story. J. Risk Res. 23, 288–296. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2019.1569091

Ekholm, S., and Olofsson, A. (2017). Parenthood and worrying about climate change: the limitations of previous approaches. Risk Anal. 37, 305–314. doi: 10.1111/risa.12626

Finucane, M., and Holup, J. (2006). Risk as value: combining affect and analysis in risk judgments. J. Risk Res. 9, 141–164. doi: 10.1080/13669870500166930

Finucane, M. L., Alhakami, A., Slovic, P., and Johnson, S. M. (2000). The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 13, 1–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0771(200001/03)13:1<1::aid-bdm333>3.0.co;2-s

Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., and Slovic, P. (2003). “Judgment and decision making: the dance of affect and reason,” in Emerging Perspectives on Judgment and Decision Research, eds J. Shanteau and S.L. Schneider (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 327–364.

Furtak, R. A. (2018). Knowing Emotions: Truthfulness and Recognition in Affective Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gotham, K. F., Campanella, R., Lauve-Moon, K., and Powers, B. (2018). Hazard experience, geophysical vulnerability, and flood risk perceptions in a Postdisaster City, the Case of New Orleans. Risk Anal. 38, 345–356. doi: 10.1111/risa.12830

Graybill, J. K. (2013). Imagining resilience: situating perceptions and emotions about climate change on Kamchatka, Russia. GeoJournal 78, 817–832. doi: 10.1007/s10708-012-9468-4

Harries, T. (2012). The anticipated emotional consequences of adaptive behaviour—impacts on the take-up of household flood-protection measures. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 44, 649–668. doi: 10.1068/a43612

Jovarauskaite, L., and Böhm, G. (2020). The emotional engagement of climate experts is related to their climate change perceptions and coping strategies. J. Risk Res. 24, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1779785

Kellens, W., Zaalberg, R., Neutens, T., Vanneuville, W., and De Maeyer, P. (2011). An analysis of the public perception of flood risk on the belgian coast. Risk Anal. 31, 1055–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01571.x

Kim, S. C., Pei, D., Kotcher, J. E., and Myers, T. A. (2020). Predicting responses to climate change health impact messages from political ideology and health status: cognitive appraisals and emotional reactions as mediators. Environ. Behav. 001391652094260. doi: 10.1177/0013916520942600. [Epub ahead of print].

Kwon, S.-A., Kim, S., and Lee, J. (2019). Analyzing the determinants of individual action on climate change by specifying the roles of six values in South Korea. Sustainability 11:1834. doi: 10.3390/su11071834

Langford, I. H. (2002). An existential approach to risk perception. Risk Anal. 22, 101–120. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.t01-1-00009

Lazo, J. K., Kinnell, J. C., and Fisher, A. (2000). Expert and layperson perceptions of ecosystem risk. Risk Anal. 20, 179–194. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.202019

Lebel, L., and Lebel, P. (2018). Emotions, attitudes, and appraisal in the management of climate-related risks by fish farmers in Northern Thailand. J. Risk Res. 21, 933–951. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2016.1264450

Lebel, L., Lebel, P., Lebel, B., Uppanunchai, A., and Duangsuwan, C. (2018). The effects of tactical message inserts on risk communication with fish farmers in Northern Thailand. Reg. Environ. Change 18, 2471–2481. doi: 10.1007/s10113-018-1367-x

Lefevre, C. E., Bruine De Bruin, W., Taylor, A. L., Dessai, S., Kovats, S., and Fischhoff, B. (2015). Heat protection behaviors and positive affect about heat during the 2013 heat wave in the United Kingdom. Soc. Sci. Med. 128, 282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.029

Lorenzoni, I., Leiserowitz, A., De Franca Doria, M., Poortinga, W., and Pidgeon, N. F. (2006). Cross-national comparisons of image associations with “global warming” and “climate change” among laypeople in the United States of America and Great Britain1. J. Risk Res. 9, 265–281. doi: 10.1080/13669870600613658

Luís, S., Pinho, L., Lima, M. L., Roseta-Palma, C., Martins, F. C., and Betâmio De Almeida, A. (2016). Is it all about awareness? the normalization of coastal risk. J. Risk Res. 19, 810–826. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2015.1042507

Mary Kate, T., Pär, B., and Peters, E. (2018). Emotional Aspects of Risk Perceptions. Cham: Springer.

Mcfarlane, B. L., and Witson, D. O. T. (2008). Perceptions of ecological risk associated with mountain pine beetle (dendroctonus ponderosae) infestations in banff and kootenay national parks of Canada. Risk Anal. 28, 203–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01013.x

Mckenna, C. M., Maycock, A. C., Forster, P. M., Smith, C. J., and Tokarska, K. B. (2020). Stringent mitigation substantially reduces risk of unprecedented near-term warming rates. Nat. Clim. Change 11:126–131 doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-00957-9

Meijnders, A. L., Midden, C. J. H., and Wilke, H. A. M. (2001). Role of negative emotion in communication about CO2 risks. Risk Anal. 21, 955–955. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.215164

Mol, J. M., Botzen, W. J. W., Blasch, J. E., and De Moel, H. (2020). Insights into flood risk misperceptions of homeowners in the dutch river delta. Risk Anal. 40, 1450–1468. doi: 10.1111/risa.13479

Morss, R. E., Lazrus, H., Bostrom, A., and Demuth, J. L. (2020). The influence of cultural worldviews on people's responses to hurricane risks and threat information. J. Risk Res. 23, 1620–1649. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1750456

O'neill, E., Brereton, F., Shahumyan, H., and Clinch, J. P. (2016). The impact of perceived flood exposure on flood-risk perception: the role of distance. Risk Anal. 36, 2158–2186. doi: 10.1111/risa.12597

Panno, A., Carrus, G., Maricchiolo, F., and Mannetti, L. (2015). Cognitive reappraisal and pro-environmental behavior: the role of global climate change perception. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 45, 858–867. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2162

Robinson, P. J., and Botzen, W. J. W. (2019). Determinants of probability neglect and risk attitudes for disaster risk: an online experimental study of flood insurance demand among homeowners. Risk Anal. 39, 2514–2527. doi: 10.1111/risa.13361

Roeser, S. (2012). Risk communication, public engagement, and climate change: a role for emotions. Risk Anal. 32, 1033–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01812.x

Shi, J., Visschers, V. H. M., and Siegrist, M. (2015). Public perception of climate change: the importance of knowledge and cultural worldviews. Risk Anal. 35, 2183–2201. doi: 10.1111/risa.12406

Siegrist, M., and Gutscher, H. (2006). Flooding risks: a comparison of lay people's perceptions and expert's assessments in switzerland. Risk Anal. 26, 971–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00792.x

Siegrist, M., Keller, C., and Cousin, M. (2006). Implicit attitudes toward nuclear power and mobile phone base stations: support for the affect heuristic. Risk Anal. Off. Publ. Soc. Risk Anal. 26:4. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00797.x

Slovic, P. (2010). The Feeling of Risk: New Perspectives on Risk Perception. https://www.google.com/search?sxsrf=AOaemvL4U2zvRAyDT3f_o1djD3LPtwcqPA:1633430781694&q=London&stick=H4sIAAAAAAAAAOPgE-LUz9U3ME4xzStW4gAxTbIKcrRUs5Ot9POL0hPzMqsSSzLz81A4Vmn5pXkpqSmLWNl88vNS8vN2sDICALPj_LVKAAAA&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi72Yfsi7PzAhX_zDgGHVPvCz4QmxMoAXoECEEQAwLondon:Routledge.

Slovic, P., Finucane, M., Peters, E., and Macgregor, D. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Anal. 24, 311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x

Smith, N., and Leiserowitz, A. (2012). The rise of global warming skepticism: exploring affective image associations in the united states over time. Risk Anal. 32, 1021–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01801.x

Smith, N. W., and Joffe, H. (2009). Climate change in the British press: the role of the visual. J. Risk Res. 12, 647–663. doi: 10.1080/13669870802586512

Stevenson, K. T., Lashley, M. A., Chitwood, M. C., Peterson, M. N., and Moorman, C. E. (2015). How emotion trumps logic in climate change risk perception: exploring the affective heuristic among wildlife science students. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 20, 501–513. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2015.1077538

Taylor, A. L., Dessai, S., and Bruine De Bruin, W. (2014). Public perception of climate risk and adaptation in the UK: a review of the literature. Clim. Risk Manag. 4–5, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2014.09.001

Terpstra, T., Zaalberg, R., De Boer, J., and Botzen, W. J. W. (2014). You have been framed! how antecedents of information need mediate the effects of risk communication messages. Risk Anal. 34, 1506–1520. doi: 10.1111/risa.12181

Thaker, J., Smith, N., and Leiserowitz, A. (2020). Global warming risk perceptions in India. Risk Anal. 40, 2481–2497. doi: 10.1111/risa.13574

Van Der Linden, S. (2014). On the relationship between personal experience, affect and risk perception: the case of climate change. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 44, 430–440. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2008

Vasileiadou, E., and Botzen, W. J. (2014). Communicating adaptation with emotions: the role of intense experiences in raising concern about extreme weather. Ecol. Soc. 19:36. doi: 10.5751/ES-06474-190236

Wagner, K. (2007). Mental models of flash floods and landslides. Risk Anal. 27, 671–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2007.00916.x

Wang, S., Leviston, Z., Hurlstone, M., Lawrence, C., and Walker, L. (2018). Emotions predict policy support: why it matters how people feel about climate change. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimens. 50, 25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.03.002

Wang, X., and Lin, L. (2018). How climate change risk perceptions are related to moral judgment and guilt in China. Clim. Risk Manag. 20, 155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2018.02.005

Yang, J. Z., and Zhuang, J. (2020). Information seeking and information sharing related to hurricane harvey. J. Mass Commun. Q. 97, 1054–1079. doi: 10.1177/1077699019887675

You, M., and Ju, Y. (2020). The outrage effect of personal stake, familiarity, effects on children, and fairness on climate change risk perception moderated by political orientation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:6722. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186722

Keywords: affect, climate change, risk communication, risk perception, emotions

Citation: Salas Reyes R, Nguyen VM, Schott S, Berseth V, Hutchen J, Taylor J and Klenk N (2021) A Research Agenda for Affective Dimensions in Climate Change Risk Perception and Risk Communication. Front. Clim. 3:751310. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2021.751310

Received: 31 July 2021; Accepted: 30 September 2021;

Published: 28 October 2021.

Edited by:

Tiffany Morrison, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, AustraliaReviewed by:

Anna Steynor, University of Cape Town, South AfricaHemen Mark Butu, Kyungpook National University, South Korea

Copyright © 2021 Salas Reyes, Nguyen, Schott, Berseth, Hutchen, Taylor and Klenk. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Raúl Salas Reyes, cmF1bC5zYWxhc3JleWVzQHV0b3JvbnRvLmNh

Raúl Salas Reyes

Raúl Salas Reyes Vivian M. Nguyen2,3

Vivian M. Nguyen2,3 Stephan Schott

Stephan Schott Nicole Klenk

Nicole Klenk