- Center for Higher Amazonian Studies (NAEA), Federal University of Para, Belem, Brazil

This paper reviews, compares, and analyzes the legal and institutional framework of Latin American government insurance systems for disaster risk. Data and information are obtained through an intense examination of disasters database, the scientific literature and legal framework of administrative and operational procedures, and mainly sources of financial funds related to disaster risk management. The results demonstrate that all countries, with the exception of Ecuador and Chile, legally establish some form of fund by their own legislation and regulation, as a total or partial form of financing the management of natural disasters, particularly those classified as post-disaster recuperation and reconstruction practices. North and Central American countries have more complex and well-structured funds, presumably based on their history of natural disasters and high social vulnerability. The funds are composed of initial values defined by law, annual contributions of general budgets, donations, and the financial gains of resources deposited into bank accounts. The paper concludes that the unavailability of required resources in an emergency situation has led Latin American countries to choose disaster funds as a primary disaster risk management financing strategy. However, the uncertainty of natural disaster occurrence is one of the main obstacles to the use of public financial resources in prevention and preparedness strategies and actions, increasing even more with the inclusion of climate change uncertainties.

Introduction

Climate changes affect natural processes, increasing the magnitude and frequency of extreme events, and consequently the characteristics of disasters of natural origin (Banholzer et al., 2014; Hallegatte, 2014). A natural disaster can be defined as a temporary event, triggered by a biophysical hazard that overwhelms local response capacity and seriously affects social and economic development (Xu et al., 2016).

Adaptation is one of the main strategies adopted by the population, various economic sectors, urban areas, and governments in the face of climate change (extreme events) risk scenarios and natural disasters (Solecki et al., 2011; Burke and Emerick, 2016). It involves a wide range of behavioral adjustments (involuntary or planned) that households and institutions make—including practices, processes, legislation, regulations, and incentives—to mandate or facilitate changes in socio-economic systems, with the aim of reducing vulnerability to extreme events and disasters (Smit et al., 1999; Füssel, 2007).

One of these, the protection and civil defense system, acts in different phases of disaster management (Lixin et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2015). In all cases, before or after the occurrence of a natural disaster, governments worldwide are forced to use many of their own public resources. Sometimes, this can be for pre-disaster actions such as prevention and preparedness activities (particularly in more unequal societies), and always for emergency relief, reconstruction of dwellings, and the restoration of vital structures (Cavallo and Noy, 2011; Neumayer et al., 2014). When local governments exceed their response capabilities, they request help from the central government (e.g., city/province, province/nation). In large-scale disaster cases, countries that lack sufficient resources are forced to request aid from other countries and international or non-governmental organizations (Becerra et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2019).

At a local level, some countries' capital cities and larger municipalities have enough financial resources to provide infrastructure and services following a disaster. However, the immense majority of small and poor regions and municipalities are largely dependent on national government resource transfers.

Government assistance can take different forms, considering the type of disaster, the magnitude of the impact, the logistical infrastructure, or the vulnerability characteristics of the affected population, among other things. It can be channeled through direct donations of materials (e.g., food and medicine), cash distribution, or financial loans with little or no interest rate and a wide term payment (Jayasuriya and McCawley, 2010), all in addition to sharing the costs of the impacts through insurance systems (Paudel, 2012; Kousky and Kunreuther, 2018).

Insurance coverage is one of the disaster management instruments (Smolka, 2006; Crichton, 2008). Each country tries to have a catastrophe insurance system according to its own circumstances and characteristics—development level, history of disasters, most common hazards, etc. Therefore, a wide variety of consolidated and disseminated private and public insurance coverage systems against natural disasters could be described and analyzed, particularly in socio-economically developed countries (Ibañez, 2000; Tsubokawa, 2004; Aakre et al., 2010; Schwarze et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2019; Paleari, 2019). Less is known with regard to developing countries and regions (Cummins and Mahul, 2009; Surminski and Oramas-Dorta, 2014).

In the context of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, UN members outline targets and priorities for action to prevent new and reduce existing disaster risks, such as (i) understanding disaster risk; (ii) strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk; (iii) investing in disaster reduction for resilience; and (iv) enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response, and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction (UNISDR, 2015).

In Latin America, while an important part of these actions, programs, and measures to achieve goals and priorities are implemented with resources from regular national budgets, considerable sums are allocated to the National Disaster Funds, a name given to the financial reserves destined to be used in case of states of abnormality.

Thus, the objective of this paper is to review, compare, and analyze the legal and institutional framework of Latin American government insurance systems (generally called “funds”) for disaster risk, in order to increase knowledge of financing strategies and instruments used to address the challenges associated with the disaster risk following extreme natural events, in scenarios of climate change.

Natural Disasters and Impacts in Latin America

The devastation caused by calamities In Latin America and the Caribbean due to natural hazards and conditions of socioeconomic vulnerability is very well-known (Maynard-ford et al., 2008, Stillwell, 1992).

Latin America and the Caribbean form one of the regions of the world most susceptible to natural disasters (Caruso, 2017). Intense seismic and volcanic activities are explained due to the region sitting atop the South American, Caribbean, Cocos, and Nazca tectonic plates. Landslides, mudslides, and lahars are moderately common due to the nature of soils and topography. There are several climate zones in the region, with different rainfall patterns and associated propensity to floods, hurricanes, and droughts. Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean are in the pathways of both western Atlantic and eastern Pacific hurricanes and tropical storms. Floods are the most common natural hazard in the region and are a function of the climate (e.g., hurricanes, tropical storms, El Niño phenomenon), hydrology (e.g., flash floods in very steep areas, lower parts of largest drainage systems), and soil characteristics. Seasonal droughts occur in climates that have well-defined annual rainy and dry seasons, such as the climatic zones that are both arid and cold. In these areas, the risk of desertification is also high. Forest fires are associated with the dry season, drought conditions, and human intervention (Charvériat, 2000).

Several different projections suggest that extreme events due to climate change could exacerbate and/or modify the frequency and spatial distribution of many of the hazards in Latin America. The number of extremely hot days is likely to increase, while the quantity of very cold days is likely to decrease. Average precipitation and so too the intensity and frequency of extreme precipitation are projected to rise in the coming decades, increasing the risk of flooding and landslides. However, mid-continental areas such as the inner Amazon basin and northern Mexico are projected to become dryer during the summer months (Magrin et al., 2014; Leal Filho, 2018).

In Latin America, conditions of vulnerability of the population and their socio-economic activities are associated, among other things, with the historical processes of territorial occupation, cities with high population densities and disorderly growth, and poverty and social inequalities. Political corruption and low degrees of legal framework implementation should also be mentioned (Rebotier, 2012; Rubin and Rossing, 2012; Nagy et al., 2018).

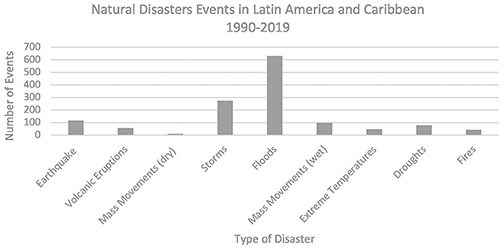

According to the CEPALSTAT database (https://estadisticas.cepal.org/), referring to the impact of disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean in the period 1990–2019, 1,350 events of geophysical origin [earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and mass movements (dry)] and climate change origin [storms, floods, mass movements (wet), extreme temperatures, droughts, and fires] have been quantified. The largest number of entries focus on flood and storm events (Figure 1). Recent natural or socio-natural events account for around 91,464 deaths and ~188 million people directly affected (injured, homeless, and affected people requiring immediate basic assistance, including food, water, shelter, sanitation, and medical assistance in an emergency period caused by a natural disaster).

Figure 1. Number of natural disaster events in Latin America and Caribbean (1990–2019) classified by type of the origin. Source of data: CEPALSTAT database (https://estadisticas.cepal.org).

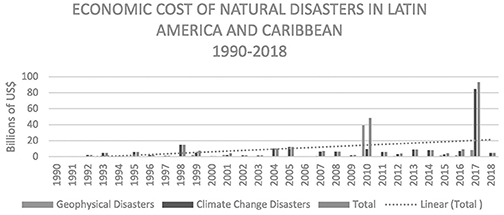

The economic cost of natural disasters (value of total economic damages and losses directly or indirectly related to extreme natural events and disasters) totaled around 273 billion U.S. dollars (79% associated with climate change). These costs are increasing over time, probably due to a variety of factors, including the growing concentration of population and assets exposed to risky areas and disasters. Particular attention should be paid to the highest values in 2010 (e.g., earthquakes in Chile in February and in Haiti in January, major floods in February and August in Mexico, heavy winter rains in Colombia and in December in Venezuela) and 2017 (e.g., earthquake in Mexico in September, hurricanes Maria in Puerto Rico and Irma in the Caribbean, heavy rains and flooding in Peru) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Economic costs of natural disasters in Latin America and Caribbean (1990–2018) expressed in billions of US$. Source of data: CEPALSTAT database (https://estadisticas.cepal.org).

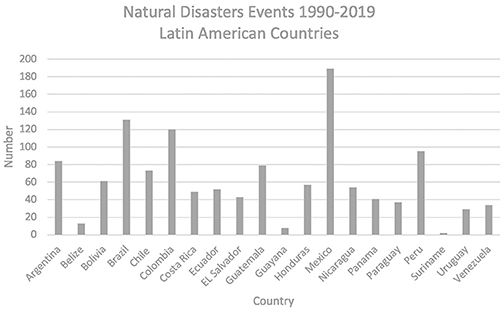

Natural disasters and their effects are not evenly distributed among the countries of the region. Between 1990 and 2019, according to the CEPALSTAT database (https://estadisticas.cepal.org/), Latin American countries registered 1,220 events (90% of the total). Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia stand out, perhaps due to their locations, extensive territories, diversity of natural landscapes, large population contingents, and the concentration of the largest economies and goods in the region being in these countries (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Number of natural disaster events in Latin America (1990–2019) classified by country. Source of data: CEPALSTAT database (https://estadisticas.cepal.org).

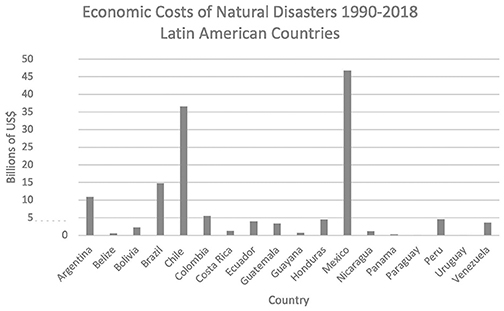

The impacts of natural disasters are increasing and becoming more spatially distributed as the world becomes more populated, with lower equality, and as people continue to damage the environment (Shen and Hwang, 2019). Although, in absolute terms, the costliest disasters mainly occur in developed countries, or particularly in Latin America in the larger economies (Mexico, Chile, Brazil, and Argentina), the less developed economies suffer the most when loss of life, injuries, and effects on GDP are considered (Zorn, 2018) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Economic costs of natural disasters by countries of Latin America (1990–2018) expressed in billions of US$. Source of data: CEPALSTAT database (https://estadisticas.cepal.org).

Financing Disaster Risk Management

Disaster risk management requires actions that work to minimize the creation of new risks and reduce any that already exist, as well as to prepare for and respond to disasters (IPCC, 2012). Among the actions that minimize and reduce risks are emergency preparedness (e.g., planning and exercises, communication systems, public awareness, and technical response capacity) and investments in both soft and hard infrastructure (e.g., strengthening and enforcing building codes, and constructing defenses). During and after the occurrence of a disaster, strategies and actions are directed to the emergency response (e.g., programs to cope with damages) and the reconstruction and rehabilitation of damaged goods and economical chains (e.g., housing, transport, and industrial reconstruction; economic and social recovery) (Miller and Keipi, 2005). Institutional structures, population engagement, and scientific and technical knowledge among others are important factors for the implementation of these actions. Financial instruments and aspects are particularly highlighted.

Even with different characteristics, most governments, particularly those less developed or in development countries, are generally clearly unaware of the financial risks they face in the event of natural disasters (Mu and Chen, 2016). However, or perhaps for that reason, they use a portfolio of sources, strategies, and instruments of economic support in the different stages of disaster risk management. The financing of disaster relief is associated with actions to be taken before, during, and after a disaster, trying to reduce or avoid any major disruption or impacts to the objectives of their development.

This finance may come from international donations or private or public domestic funding structures and instruments. International funding from general resources or specific contingents (countries, international or multilateral governments, or institutions) supports many different aspects of disaster management, including humanitarian aid, development processes, and reducing the impacts of climate change. Some aspects of the international contributions to disaster management in Latin American countries were studied by Fagen (2008). Private-sector finance is diverse and involves foreign direct investment, insurance markets on various scales, and civil society and philanthropic organization remittances (Kunreuther and Michel-Kerjan, 2014; Kapucu, 2016; Mbaye and Drabo, 2017; Benali and Feki, 2018).

In the region, assistance from donors, often generous, is highly dependent on the visibility of a given event and usually arrives long after the event. Disaster insurance coverage is limited, due to the non-insurability of many assets (e.g., irregular settlements without property title or valuation and dwellings built without solid materials), high insurance premiums, regulatory obstacles to the development of insurance, and disinterest in insurance fostered by the availability of national and international assistance in times of crises (Miller and Keipi, 2005).

Considering the existing domestic public financing structures in disaster risk reduction, each country allocates resources to (i) broader development policies (e.g., land use and water planning and management, infrastructure reforms, retrofitting schools and hospitals, and environmental and risk-driven social protection), (ii) specific risk management projects in the national budget (e.g., climate and risk monitoring, early warning systems), and (iii) special calamity funds (Kellett and Peters, 2014).

The Civil Defense Systems and Special Calamity Funds in Latin America

After understanding the importance of the impacts of natural disasters on the economy and security of the population, as well as their close relationship with socio-economic development conditions, Latin American countries established and improved various levels of civil defense systems. This included the organization of emergency and reconstruction aid and, subsequently, with a more integrated vision of risk management, preparation and prevention activities.

National institutions, policies, and plans are critical for effective disaster risk management. For this to happen, countries must find ways to ensure sufficient liquidity of resources before the disaster, but mainly during the periods of emergency as soon as the disaster strikes, shortly after, and during the recovery phase. Due to the unavailability of insurance, and considering the problems of economic resource scarcity, mandatory priorities in periods of “normality,” and sometimes poor government management of resources with annual general budgets, the countries of Latin America have put their own calamity funds into place.

The present research methodology, adapted from Vatsa et al. (2003), consists of an intense examination and analysis of the scientific literature and legal framework of administrative and operational procedures, and mainly sources of financial funds related to disaster risk management in Latin American countries. All countries (14), with the exception of Ecuador and Chile, legally establish some form of fund as a total or partial form of financing.

Mexico

The General Law on Civil Protection, 2012 (last reform in 2018), establishes the basis for coordination between the three government levels in the field of civil protection, through the National System of Civil Protection. The system is an articulated set of structures, functional relationships, methods, standards, instruments, policies, procedures, and services, which determine the co-responsibility between voluntary groups and organizations; the public sector; legislative, executive, and judicial powers; autonomous constitutional bodies; and municipalities. Its purpose is to carry out coordinated actions for civil protection in case of disaster risk in the short, medium, or long term, caused by anthropogenic or natural phenomena, through comprehensive risk management and the development of relief.

The Federal Executive, through the Secretary of Finance and Public Credit, in terms of the Federal Law on Budget and Responsibility, provides the financial resources for the timely attention of emergencies. When impacts of natural disasters are unpredictable and the local response capacity is exceeded, complementary support can be requested for the national government's Natural Disaster Fund (FONDEN). FONDEN was established in 1996. Each federal entity can create and manage its own civil protection fund.

In order to access the resources of FONDEN, a request must be submitted to the Secretary of the National Civil Protection System expressly stating that circumstances have exceeded the operational and financial capacity of a particular region to deal with the disaster on its own, stating the disruptive natural phenomenon, the specific period of occurrence, as well as the municipalities and the population concerned. Therefore, the Secretary issues the “Emergency Declaration” (recognition of the imminence, high probability, or presence of an abnormal situation generated by a disruptive natural agent that causes immediate assistance for the population at risk to be required) and the “Declaration of Natural Disaster” (identification of the presence of disaster damage that exceeds the local financial and operational aid capacity).

Once the declaration of emergency is issued, the federal entity may be supported by FONDEN, to which it must submit an application for the urgent needs of the affected or potentially affected population, such as (i) consumable and durable supplies sufficient to meet urgent needs, or according to the estimated population that will be vulnerable or susceptible to impact; (ii) medicines, healing materials, and others related to the care and health protection of the population [application made through the National Center for Preventive Programs and Disease Control of the Ministry of Health (CENAPRECE)]; and (iii) reagents and insecticides used to control vector-borne diseases that must meet the sensitivity and specificity characteristics required for epidemiological and health surveillance.

The appropriate requests are sent by FONDEN to the Directorate-General for Material Resources and General Services of the Federal Government (DGRMSG) that, within its competence, makes the respective purchases and delivery in the province or municipality affected.

Considering the possibility of processual delays or in the case where the local authority does not submit any request, FONDEN authorizes a minimum package of care inputs for the vulnerable population affected or susceptible to effects, comprising the following products: food, drinking water, and bedding. FONDEN may immediately authorize mobilization of the remnants of inputs from other national or international (prior to the opinion of the Secretariat for Foreign Affairs) emergencies.

Republic of Guatemala

The National Security System law (Decree 18/2008—https://mingob.gob.gt/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ley_marco_d018-2008.pdf) establishes the legal rules for the coordinated realization of activities by the State of Guatemala, so that in an integrated, systematized, efficient, and effective way, it is able to anticipate and give effective response in case of risks, and be prepared to prevent, confront, and counter them. The law is also the basis of the National Security System.

The purpose of the system, developed by the Internal and Foreign Security departments; State Intelligence, Risk Management, and Civil Defense areas, is to strengthen state institutions, prevent risks, control hazards, and reduce vulnerabilities that prevent the State from fulfilling its purposes. The system is composed of the Presidency of the Republic, ministers (foreign relations, government, and national defense), the Attorney General's Office, the National Disaster Reduction Coordinator (CONRED), the Secretariat of Strategic Intelligence of the State, and the Secretariat of Administrative and Security Affairs of the Presidency of the Republic.

When disasters occurred, budget reallocations of the different institutions were carried out. Since 2019, the State General Revenue and Egress Budget Act (Law 5610—https://www.congreso.gob.gt/detalle_pdf/iniciativas/5609) has been providing a budget forecast for an emergency fund as part of the financial resilience mechanisms in the face of a possible need to pay attention to the occurrence of natural disasters, in order to address any contingency more expeditiously, and does not directly impact public finances, affecting the development of the implementation of the various programs contained in the public budget. These resources are activated only at the time of decreeing a state of calamity by the President of the Republic and ratified by the Congress.

Republic of El Salvador

The National System of Civil Protection, Prevention, and Mitigation of Disasters (Decree 777/2005—https://www.asamblea.gob.sv/decretos/details/476) is an interrelated and decentralized set of public and private bodies responsible for formulating and implementing the respective work plans for civil protection, disaster risk prevention, and mitigation of disaster impacts. The system consists of the national departmental and municipal commissions for civil protection, disaster prevention, and mitigation. A fund for civil protection, disaster prevention, and mitigation has been created for the sustainability of the system.

The Fund for Civil Protection, Prevention, and Disaster Mitigation (FOPROMID) (Decree 778/2005—https://www.asamblea.gob.sv/decretos/details/39) is an entity of public law, with legal personality and its own assets, also enjoying administrative and financial autonomy. The administration of FOPROMID is the responsibility of the Minister of Finance.

FOPROMID's balance is made up of an initial contribution from the General Budget of the State and donations from any national or foreign entity. It is subsequently added to funds allocated annually in the General Budget of the State and contributions from any other source. The financial resources with which FOPROMID is constituted, as well as others that will be perceived in the future, must be deposited into a special bank account.

FOPROMID resources may only be used for disaster prevention or in cases where timely and effective disaster emergency attention is required. In the event of a disaster of great proportion, FOPROMID may request an emergency budget from the Council of Ministers.

Republic of Nicaragua

The National System for Disaster Prevention, Mitigation, and Response (SINAPRED) was created as part of Law 337/2000 (http://ocu.ucr.ac.cr/images/ArchivosOCU/Normativa/NormativaExterna/Ley_Contratacion_Administrativa.pdf). It is responsible for performing actions aimed at reducing the risk of natural and man-made disasters, as well as protecting society, such as with the development and execution of disaster prevention, mitigation, and response plans, the promotion of scientific and technical research, the reduction of population vulnerability, and helping the affected population. The guarantee of public financing for these activities is established through the National Fund for Disaster that is regulated by Decree 88/2007 (http://legislacion.asamblea.gob.ni/Normaweb.nsf/fb812bd5a06244ba062568a30051ce81/2436a8e1d0fdd1b60625736e0061389e?OpenDocument).

The fund's resources are available to SINAPRED to act in the case of imminent risks or disaster situations and are deposited into a bank account, to which only the chairman of the board of directors of the fund has access to, to manage and withdraw. The fund is made up of financial resources—the General Budget of the Republic; financial contributions, donations, legacies, and inheritances or grants made by natural or legal persons, national or foreign; and any other returns from the resources mentioned above originating from interest accrued in the bank accounts—and non-financial resources. After the presentation of the expense report, the resources of the fund are subject to all control and audit procedures established by the laws of the Republic and are the responsibility of the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit.

Republic of Costa Rica

The National Emergency and Risk Prevention Law (Law 8488/2005—https://www.ucr.ac.cr/medios/documentos/2015/LEY-8488.pdf) established the National Risk Management System, understood as the integral, organized, coordinated, and harmonious articulation of state institutions, seeking the participation of the private sector and organized civil society, with the purpose of planning and executing public policy guidelines that enable incorporation of the concept of risk management as a cross-cutting axis of planning and development practices. The National Risk Management System was designed for risk prevention and preparations to deal with emergencies through the National Commission for Risk Prevention and Emergency Assistance. The commission is a body of the Presidency of the Republic, with its own assets and budget. The commission has the following sources of funding for the performance of its functions: transfers from the national budget, the amount provided for in Article 46 of the law for the financing of the National Risk Management System, and the resources of the National Emergency Fund.

The National Emergency Fund is administered by a commission, which is authorized to invest in securities of public-sector institutions and companies. All resources must be used to address emergency, prevention, and mitigation situations. The fund consists of the following resources: the regular and extraordinary national budgets; contributions, donations, and transfers from natural or legal persons, national or international, state, or non-governmental bodies; the transfer of resources from all central government institutions, the decentralized public administration, public enterprises to the value of 3% of the profits and budget surpluses that each of them report; contributions from financial instruments; and interest generated by the transitional investment of resources. State institutions, local governments, state-owned enterprises, and any other persons, natural or legal, public or private, are authorized to donate sums for the formation of the National Emergency Fund.

The acquisition of goods and services with the resources of the fund to attend to the declared emergency events is governed by the principles set out in the law on administrative procurement (Law 7494/1995—http://ocu.ucr.ac.cr/images/ArchivosOCU/Normativa/NormativaExterna/Ley_Contratacion_Administrativa.pdf). The administration, use, and disposal of resources deposited to the fund are subject to audit by the Controller General of the Republic and the Internal Audit of the Commission. The costs required for the administration, management, control, and audit of the National Emergency Fund are covered by up to 3% of the amount that makes up the fund.

Republic of Panama

The National System of Civil Protection (SINAPROC), established by Law 22/1982 (https://docs.panama.justia.com/federales/leyes/22-de-1982-nov-22-1982.pdf) and Organic Law 7/2007 (https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.pa/pdfTemp/25727/GacetaNo_25727_20070207.pdf), is responsible for helping to protect the population from damage caused by disasters of any origin. To this end, it coordinates measures to prevent and reduce the impact of disasters, mitigate or neutralize the damage that such cataclysms could cause to people and property, and carry out emergency response actions. The administration, direction, and operation of SINAPROC is managed by a director-general appointed by the President of the Republic, with the participation of the Minister of Government and ratified by the National Assembly.

Part of SINAPROC's activities are financed by the Panama Savings Fund (FAP). FAP was established by Law 38/2012 and amended by laws 87/2012 and 51/2018 (https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.pa/pdfTemp/27050_A/GacetaNo_27050a_20120606.pdf). FAP aims to establish a long-term savings and stabilization mechanism for cases of emergency status and economic slowdown, as well as to reduce the need for debt instruments to address the circumstances described above. Administration of FAP is carried out by the National Bank of Panama. FAP is constituted by all the assets of the Trust Fund for the Development of Panama and was authorized to accumulate assets of 50% of any contribution by the Panama Canal Authority to the National Treasury of more than 2.5% of nominal GDP for the 2018 and 2019 fiscal year, reduced to 2.25% from fiscal 2020; FAP yields from FY 2018, which were capitalized in FAP for the following fiscal term, until its assets were more than 5% of the previous year's nominal GDP; funds from the sale of shares of state-owned joint ventures; and the inheritances, legacies, and donations that are made to FAP. Withdrawals may only be associated with situations of state of emergency as declared by the Cabinet Council, provided that the related cost is equal to or >0.5% of GDP. The Ministry of Economy and Finance (Trustee) may take out catastrophe insurance (an insurance policy covering material or consequential losses suffered by the insured) as a tool for forecasting potential natural disasters.

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela

Act 1557/2001 aims to organize, integrate, coordinate, and operate the activities of the Civil Protection and Disaster Management Organization at the national, provincial, and municipal level (https://www.eird.org/wikiesp/images/Ley_Proteccion_Civil_y_administarcion_de_desastres_Venezuela.pdf). This organization is a member of the National System of Risk Management and the National Coordination of Citizenship Security. Its objectives are to plan and establish national disaster preparedness policies and measures, to develop training and education programs to promote the population participation in emergency and disaster responses, to strengthen care and emergency management agencies, and to ensure that the government provides the necessary resources and operational support for civil protection and disaster management.

The Disaster Prevention and Management Fund was created to develop these activities, linked to the Ministry of the Interior and Justice. The objective of the fund is to manage the extraordinary budget allocations and resources from the contributions made to any title by natural or legal persons, national or foreign, foreign governments, and international organizations, for financing disaster preparedness and aid activities, and rehabilitation and reconstruction.

Republic of Colombia

The Colombian Civil Defense is an entity of the Ministry of Defense for preventing and controlling disasters, and driving the operational part of the National System for the Prevention and Care of Disasters. All governmental agencies must include special resources for prevention and disaster response in their budgets. However, at the national level, there is a special account, characterized by its patrimonial and administrative independence called the National Calamities Fund. The fund is established by Decree 1547/84 (https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=66925). According to Decree 919/89 (https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=13549), the fund's resources are designated to (a) financially supporting aid for disasters and calamities; and prioritizing the production, conservation, and distribution of food, medicines, and provisional accommodation; (b) controlling the impact of disasters and calamities; (c) maintaining environmental sanitation conditions during the rehabilitation and reconstruction phases; (d) financing installation and operation of information systems suitable for prevention, diagnosis, and aid for disasters (e.g., the national seismograph network); and (e) encouraging the use of private insurance coverage taken with legally established companies in the Colombian territory. Decree 919/89 is regulated by national decrees 976/1997, 2015/2001, and 4550/2009.

For disaster management purposes, central administration institutions' and agencies' resources rely on trusteeship, such as through the “La Previsora” trustees, an industrial and commercial state-owned company, linked to the Ministry of Economy. This fiduciary society has an advisory board with responsibilities to direct the general policies of management and investment of the fund's resources, as well as destination and priority for their usage. Requests from the states and municipalities in crisis reach this board after their own budgets for aid to the affected population are exceeded.

Republic of Peru

The National Disaster Risk Management System of Peru (SINAGERD) (Law 29664/2011, regulated by Supreme Decree 48/2011) was created with the aim of identifying and reducing disaster risks or minimizing their effects, avoiding the generation of new risks, and contributing to the preparedness for and attention to disaster situations (http://www.leyes.congreso.gob.pe/Documentos/Leyes/29664.pdf). SINAGERD consists of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers; the National Disaster Risk Management Council; the National Center for Disaster Risk Estimation, Prevention, and Reduction (CENEPRED); regional and local governments; the National Center for Strategic Planning; as well as public entities, the armed forces, the Peruvian National Police, private entities, and civil society.

SINAGERD's instruments are the National Disaster Risk Management Plan, the National Disaster Risk Management Information System, the National Radio for Civil Defense and the Environment, and the Disaster Risk Financial Management Strategy. This strategy considers the budget programs linked to disaster risk management, organized by processes of estimation, prevention, and risk reduction, as well as preparedness, response, and rehabilitation. The resources of the strategy are those existing in the Contingency Reserve and the Fiscal Stabilization Fund, credits, donations, and other market instruments for disaster care that were contracted by the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

In this sense, Law 30458/2016 established the Fund for Interventions in the Event of Natural Disasters (FONDES), for the Ministry of Economy and Finance, with the aim of financing public investment projects for mitigation, rehabilitation, and reconstruction in the event of natural phenomena (http://www.leyes.congreso.gob.pe/Documentos/Leyes/30458.pdf).

The national, regional, or municipal governments can access FONDES to finance interventions for the following reasons: (i) mitigation and responsiveness to the occurrence of natural phenomena, aimed at reducing existing risk, and preparing for emergency and/or disaster response; (ii) imminent risk response and rehabilitation, aiming to reduce the likely damage that the impact of an imminent natural or anthropic phenomenon may cause; actions in the event of disasters; and the rehabilitation of damaged infrastructure and/or public services, once the disaster has occurred. Such interventions pre-require the Declaration of State of Emergency for Disaster or Imminent Risk; and (iii) reconstruction, carried out to establish sustainable development conditions in the affected areas.

Plurinational State of Bolivia

Law 602/2014 (regulated by Supreme Decree 2342/2015) is the legal basis for the National System of Risk Reduction, Disaster Prevention, and Emergencies (SISRADE) (http://www.silep.gob.bo/norma/13365/ley_actualizada), establishing a framework for risk management, which includes risk reduction through prevention, mitigation, and recovery actions; disaster and/or emergency care by means of activities to prepare, respond to, and rehabilitate after disasters caused by natural, socio-natural, technological, and anthropic hazards; and the resolution of social, economic, physical, and environmental vulnerabilities.

SISRADE is made up of central and local (department and municipal) level government entities, social organizations, and people, who interact with each other in a coordinated and articulated manner. The system is formed by the National Council for Risk Reduction and Disaster and Emergency Aid (CONARADE) and the departmental and municipal committees for risk reduction and disaster aid. The system's funding is associated with the budgets of national entities, as well as local and autonomous territorial units, as set out in their development, emergency, and contingency plans. Another source of resources is the Fund for Risk Reduction and Care for Disasters and/or Emergencies (FORADE), established by the Ministry of Defense for a period of 10 years with the aim of capturing and administrating resources to finance risk management at the national, departmental, municipal, and autonomous indigenous levels.

FORADE's funding sources are the National General Budget (0.15%), monetary donations, credits, specific resources for multilateral or bilateral cooperation for risk management, and revenues generated by FORADE itself, among others. In order to ensure the sustainability of the trust, the resources may be invested under principles of security and liquidity and its administration is subject to an annual external audit as a minimum.

One of CONARADE's functions is to approve the distribution of FORADE resources, considering the efficiency criteria, the balance between risk management components, and existing priorities according to the different scenarios of risk and disaster. CONARADE authorizes the allocation of resources to entities at the central and/or autonomous territorial level of the State, providing they meet the following minimum conditions: the submission of a request for funding on a particular technical proposal or project (in case of preparation), the respective declaration of disaster with the assessment of the level of impact of disasters and estimation of rehabilitation costs (in case of emergency care and rehabilitation), and the request for funding on a given project previously technically and financially assessed (in case of projects focused on knowledge or risk reduction).

The Vice-Ministry of Civil Defense is able to access FORADE's resources through authorization from CONARADE, in exceptional cases, and exclusively to finance humanitarian aid activities requiring immediate assistance, in order to provide urgent support necessary to safeguard the life, health, and physical integrity of the affected population.

Republic of Paraguay

The Secretariat of National Emergency (SEN), responsibility of the Presidency of the Republic, was established by Law 2.615/2005 (https://www.bacn.gov.py/archivos/2410/20151016083211.pdf) with the objective of preventing and counteracting the effects of emergencies and disasters caused by agents of nature or any other origin, as well as promoting, coordinating, and guiding the activities of public and private institutions with the aim of preventing, mitigating, and responding to emergencies or disasters, and the rehabilitation and reconstruction of communities affected by them. In this sense, SEN may collect information, identify risks, record statistics of disasters and their impacts, coordinate assistance to affected communities, encourage the creation and organization of emergency-risk reduction, develop and implement education programs in communities, seek international cooperation on risk reduction and mutual assistance in civil protection, and conduct outreach campaigns related to civil protection systems and methods.

The resources necessary for the operation of SEN are provided by the general budget of the nation, by the ministries that must carry out specific assistance in cases of emergency, and those existing in the National Emergency Fund.

The National Emergency Fund functions as a special account of the nation with economic, administrative, accounting, and statistical independence. Half of the resources are designated to finance disaster prevention and/or mitigation projects. The remaining 50% is earmarked for preparedness and response measures. If the budgeted resource is not used in a fiscal year, it will return to the Nation's General Income Account.

The origins of the resources of the National Emergency Fund are (i) 10% of the tax collections from sales of cigarettes and alcoholic beverages, (ii) the General Direction of the Treasury when an emergency or disaster is declared, (iii) the Social Assistance Institution (DIBEN) that provides specific resources to support emerging preparedness and response programs, and (iv) donations received from domestic or foreign persons or institutions. The administration of the National Emergency Fund is managed by SEN.

The resources of the National Emergency Fund can be applied to the financing of one-off actions aimed at the prevention and mitigation of events capable of causing disasters, and the preparation, response, and rehabilitation of communities affected by disaster situations when at least one of the following occur:

(a) There are plans and programs submitted to the SEN council. Where the plan or program corresponds to actions projected by states or municipalities, the allocation of finance resources from the National Emergency Fund is subject to the contribution of a counterparty of the state or municipality. The proportion of the counterparty will be determined in each case.

(b) There is an emergency situation or declaration of disaster.

(c) The institutions have replenished duly documented and authorized operating expenses that have been committed to the care of an emergency of significant magnitude.

Federative Republic of Brazil

Law 12608/2012 provides for the National Policy for Protection and Civil Defense (PNPDEC) and the National System of Protection and Civil Defense (SINPDEC) (http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2012/Lei/L12608.htm). PNPDEC covers prevention, mitigation, preparation, response, and recovery actions focused on protection and civil defense, integrating the policies of territorial planning, urban development, health, environment, climate change, water resource management, geology, infrastructure, education, science and technology, and other sectoral policies, with a view to promoting sustainable development. SINPDEC is composed of the organs and entities of the Federal Public Administration, the states, the Federal District and the municipalities, and the public and private entities of significant performance in the area of protection and civil defense. SINPDEC aims to contribute to the process of planning, articulation, coordination, and execution of protection and civil defense programs, projects, and actions.

Transfers from the Union to the states, the Federal District, and municipalities are mandatory for the development of SINPDEC activities. In the case of recovery actions, the beneficiary must submit a work plan to the body responsible for the transfer of resources within 90 days of the occurrence of the disaster. In the case of response actions, exclusively providing help and assistance to victims, the Federal Government can provide prior support for federal recognition of the emergency situation or state of public calamity, and the beneficiary is responsible for the presentation of the necessary documents and information.

The transfer of financial resources can be done by (i) depositing money in a specific account maintained by the beneficiary entity in an official federal financial institution; or (ii) withdrawing from the National Fund for Public Calamities, Protection, and Civil Defense (FUNCAP) to funds constituted by states, the Federal District, and municipalities with specific purpose. The body responsible for transferring the resource must follow and monitor the application of the resources transferred.

FUNCAP, linked to the Ministry of National Integration and established in 1969 (Decree 950/1969—http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Decreto-Lei/1965-1988/Del0950.htm), has the purpose of funding, in whole or in part, prevention actions in disaster risk areas dispensing with the conclusion of an agreement or other legal instruments. It also funds actions to recover disaster-stricken areas in federal entities that have the emergency situation or state of public calamity recognized and approved. FUNCAP resources are appropriations included in the Annual Budget Law of the Union, and its additional credits, donations, and other sources of income are kept in the National Treasury Single Account and managed by a board of directors, who should establish the criteria for prioritization and approval of work plans, monitoring, supervision, and approval of accountability. Social control over the allocations of FUNCAP's resources is exercised by councils linked to the benefited entities, ensuring the participation of civil society.

Oriental Republic of Uruguay

The National Emergency System (SINAE), created by Law 18621/2009 (https://legislativo.parlamento.gub.uy/temporales/leytemp8156395.htm), is a permanent public system, whose purpose is the protection of persons, goods, and the environment, in the eventual or actual occurrence of disaster situations, through the coordination of the National Government with the appropriate use of available public and private resources, in order to promote the conditions for sustainable national development.

The functioning of the system is embodied in the package of governmental actions aimed at the prevention of risks linked to natural or human disasters, foreseeable or unforeseeable, periodic or sporadic; mitigation and attention to disasters; and the immediate rehabilitation and recovery tasks that are necessary. SINAE is integrated by the Presidency, the National Emergency Directorate, the National Advisory Commission for Risk Reduction and Disaster Care, autonomous institutions and decentralized services, as well as local emergency committees.

SINAE is financed by budget and non-budget resources that integrate the National Fund for Disaster Prevention and Care. The fund consists of donations and legacies to the system or to the performance of its specific or coordinated activities, and transfers from other public entities. Any kind of donations, legacies, and transfers addressed to SINAE are exempt from any type of national taxes. SINAE has ownership and availability of the entire fund. Resources not affected or executed at the end of each financial year continue to integrate the fund and may be used in the following years.

Argentine Republic

The National System for Integral Management of Risk and Civil Protection, established by Law 27287/2016 (http://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/265000-269999/266631/norma.htm), aims to integrate and articulate the actions and the functioning of the agencies of the national and provincial governments, the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and its municipalities, non-governmental organizations, and civil society, to strengthen and optimize actions aimed at risk reduction, crisis management, and recovery. The system is composed of the National Council for Integral Risk Management and Civil Protection, and the Federal Council for Integral Risk Management and Civil Protection. The National Council is the highest body for decision, articulation, and coordination of the resources and is intended to design, propose, and implement public policies for comprehensive risk management.

The National Fund for Integral Risk Management was created to finance the prevention and response actions managed by the Executive Secretariat of the National Council for Integral Risk Management and Civil Protection. The fund is a trustee, and its economic resources come from the nation's, the provinces', and the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires' resources; donations and legacies; gains from financial investments; national and international loans, and others provided by the State when dealing with emergencies; taxes that are created with specifically for the fund; and any other resource assigned to it. The national fund resources come from the General Budget of the Nation of the corresponding year.

Contributions to the fund may be made in cash or bonds from the contributing jurisdiction so as not to affect the liquidity of the budgets during their constitution or their possible recapitalization after a large event has occurred. The resources of the National Emergency Fund originating from revenues of financial assets may be applied to prevention actions only with authorization from the National Council for Integral Risk Management and Civil Protection.

The National Emergency Fund is drawn from in an emergency or disaster, established by the National Council for Integral Risk Management and Civil Protection to provide liquidity by selling its assets or applying them as a warranty in term banking operations aimed at obtaining short-term liquidity.

Discussion

The analysis of the funds associated with financing disaster risk management in Latin America presents some commonalities.

Protection and civil defense systems are in some cases associated with more far-reaching security systems and almost always integrating broader concepts of sustainable development. These systems are composed of public-sector departments, with the participation of the private sector and the population, and can be replicated in subnational instances. With well-defined organization, they all present a broad portfolio of forms of financing, including emergency funds.

Most of the funds, established in civil protection and defense system laws or by their own legislation and regulation, mainly relate to the management of natural disasters, with very few references to other types, as well as not clearly differentiating events by the magnitude of the hazard or the impact generated.

Prevention and preparedness activities, such as monitoring and early warning or climate extreme events, are clearly central to the analysis and reduction of climate-associated disaster risks. As a result, they are also fundamental in reducing the expenditure allocated in mitigation and recovery stages. Therefore, some mechanisms that financially support prevention and preparedness activities to cope with the imminence of a public calamity are identified. However, the vast majority of these arrangements can be classified as post-disaster recuperation and reconstruction practices. In this sense, the official declaration of states of calamity and emergency, approved by the fund managers, are the fundamental instruments for initiating and legalizing the processes.

Among the 16 countries analyzed, only Ecuador and Chile do not present a fund as a financial strategy for management of natural disasters. North and Central American countries have more complex and well-structured funds, presumably based on their history of natural disasters and high social vulnerability; however, the Brazilian FUNCAP is the oldest, established in 1969.

Either the funds are the only sources of resources, or they complement other previously existing resources for disaster risk management such as money destined for different development-related programs in ministries or autonomous institutions' budgets. Regardless of the type of fund, they are composed of a varied range of possibilities, which are mainly concentrated in initial values defined by law, annual contributions of general budgets, donations (national and international, private and public), and the financial gains of resources deposited into bank accounts.

Resources are used by all levels of government management (national, provincial, municipal, those of autonomous territories) and can be distributed to areas affected by the central government as money or as necessary materials purchased after formal orders.

Considering the scarce resources, but mainly the historical problems with the proper use of public money, the resources are earmarked for a single-purpose account for the needs set out in the legislation related to the formation of the funds, often in an official bank and with only one person responsible for withdrawals. In the same sense, the processes of auditing expenditures are described in detail, as well as the destination of resources not used in the year, which remain in the next year's budget or are available for another affected area or disastrous event.

Conclusions

All Latin American countries have established disaster risk management systems, which are being updated frequently, due to the need to adapt to new environmental realities, but mainly new political–administrative and fiscal scenarios. Frequent changes in legal frameworks are a common reality in the region. Experiences of calamities with large and diverse impacts, however, have shown that financial preparedness is much less developed in the region.

In this sense, a broad portfolio of possibilities for financial strategies and instruments have recently been established, although, in countries with few resources and low levels of development, there is still a high reliance on resources from international disaster-fighting assistance. The unavailability of required resources in an emergency situation has led Latin American countries to choose disaster funds as a primary disaster risk management financing strategy.

The present work compares the different existing funds; however, the fact that many of them were recently established and the absence of clear and available information for all countries do not allow an assessment of their effectiveness. Some articles evaluate in different ways the funds in Colombia (Méndez et al., 2013) and Mexico (Rodríguez Esteves, 2004).

Likewise, it is possible to mention as important elements for the wide adoption of disaster funds by almost all countries of the region the facts that the funds (i) are free of conditions imposed by the international donor or the private sector (this has important implications on the domestic policy of some countries); (ii) greatly reduce the impact of a disruption to planned fiscal and macroeconomic development; (iii) represent an opportunity to include resources in a larger and general plan for sustainable development and integrated disaster management (particularly pre-disasters actions) than in simple humanitarian aid actions; and (iv) reduce financial pressures following a disaster, as they have no obligation to be repaid.

While many resources used in the implementation of prevention and disaster preparation measures are distributed budgets of social policy or public infrastructure, the probability or uncertainty of natural disaster occurrence and strict control of public expenditure in the context of anticorruption measures are some of the main obstacles to the use of public financial resources (e.g., Funds) in prevention and preparedness strategies and actions. This obstacle is increased even more with the inclusion of climate change uncertainties.

In this sense, the resources of permanent and exclusive disaster management funds take importance. However, the funds do not explicitly mention climate change or variability, and/or extreme events issues in addition to their close relationship with natural disasters. In a context of climate change scenarios, it is possible to indicate the need to allocate greater resources to funds for speed and flexibility in resource distribution through less bureaucracy and the creation or distribution of greater autonomy, and the responsibility for funds at local levels, closest to the affected populations and regions.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: The data are available at the different and several websites of the governments of Latin America countries, and are included in the “reference” chapter of the document.

Author Contributions

CS was responsible for the conception of the work, research data and information, and the drafting of the document.

Funding

The author thanks Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) Universal project 406168/2016 for funding the research.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aakre, S., Banaszak, I., Mechler, R., Rübbelke, D., Wreford, A., and Kalirai, H. (2010). Financial adaptation to disaster risk in the European Union–identifying roles for the public sector. Mitigat. Adaptat. Strateg. Glob. Change 15, 721–736. doi: 10.1007/s11027-010-9232-3

Banholzer, S., Kossin, J, and Donner, S. (2014). “The impact of climate change on natural disasters” in Reducing Disaster: Early Warning Systems for Climate Change, eds A. Singh, and Z. Zommers (Dordrecht: Springer), 21–49. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-8598-3_2

Becerra, O., Cavallo, E., and Noy, I. (2014). Foreign aid in the aftermath of large natural disasters. Rev. Dev. Econ. 18, 445–460. doi: 10.1111/rode.12095

Benali, N., and Feki, R. (2018). Natural disasters, information/communication technologies, foreign direct investment and economic growth in developed countries. Environ. Econ. 9, 80–87. doi: 10.21511/ee.09(2).2018.06

Burke, M., and Emerick, K. (2016). Adaptation to climate change: evidence from US agriculture. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 8, 106–140. doi: 10.1257/pol.20130025

Caruso, G. (2017). The legacy of natural disasters: the intergenerational impact of 100 years of disasters in Latin America. J. Dev. Econ. 127, 209–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.03.007

Cavallo, E., and Noy, I. (2011). Natural disasters and the economy-a survey. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 5, 63–102. doi: 10.1561/101.00000039

Charvériat, C. (2000). Natural Disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Overview of Risk. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1817233

Crichton, D. (2008). Role of insurance in reducing flood risk. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 33, 117–132. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.gpp.2510151

Cummins, J., and Mahul, O. (2009). Catastrophe Risk Financing in Developing Countries Principles for Public Intervention. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-7736-9

Fagen, P. (2008). Natural Disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean: National, Regional and International Interactions-A Regional Case Study on the Role of the Affected State in Humanitarian Action. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Füssel, H. (2007). Adaptation planning for climate change: concepts, assessment approaches, and key lessons. Sustain. Sci. 2, 265–275. doi: 10.1007/s11625-007-0032-y

Hallegatte, S. (2014). “Climate change impact on natural disaster losses,” in Natural Disasters and Climate Change, eds S. Hallegatte (Cham: Springer), 99–129. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-08933-1_5

Ibañez, A. (2000). “Los Peligros Naturales: Heterogeneidad de Sistemas de Cobertura Aseguradora en el Mundo,” in Gerencia de riesgos, eds A. Ibañez (Madrid: Fundación Mapfre), 13–28.

IPCC (2012). Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jayasuriya, S., and McCawley, P. (2010). The Asian Tsunami: Aid and Reconstruction After a Disaster. Cheltenham: Asian Development Bank Institute. doi: 10.4337/9781849806831

Jiang, Y., Luo, Y., and Xu, X. (2019). Flood insurance in China: recommendations based on a comparative analysis of flood insurance in developed countries. Environ. Earth Sci. 78:93. doi: 10.1007/s12665-019-8059-9

Jones, S., Manyena, B., and Walsh, S. (2015). “Chapter 4-Disaster Risk governance: evolution and influences,” in Hazards, Risks and Disasters in Society, eds J. Shroder, A. Collins, S. Jones, B. Manyena, and J. Jayawickrama (Oxford: Academic Press), 45–61. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396451-9.00004-4

Kapucu, N. (2016). “The Role of philanthropy in disaster relief,” in The Routledge Companion to Philanthropy, eds T. Jung, S. Phillips, and J. Harrow (New York, NY: Routdlege), 178–192.

Kellett, J., and Peters, K. (2014). Dare to Prepare: Taking Risk Seriously: Financing Emergency Preparedness-From Fighting Crisis to Managing Risk. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Kousky, C., and Kunreuther, H. (2018). Risk management roles of the public and private sector. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 21, 181–204. doi: 10.1111/rmir.12096

Kunreuther, H., and Michel-Kerjan, E. (2014). Chapter 11-Economics of natural catastrophe risk insurance. Handb. Econ. Risk Uncertain. 1, 651–699. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53685-3.00011-8

Leal Filho, W. (2018). “Climate change in latin america: an overview of current and future trends,” in Climate Change Adaptation in Latin America, eds W. Leal Filho, and L. Esteves de Freitas (Cham, Springer), 529–535. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56946-8_31

Lixin, Y., Lingling, G., Dong, Z., Junxue, Z., and Zhanwu, G. (2012). An analysis on disasters management system in China. Nat. Hazards 60, 295–309. doi: 10.1007/s11069-011-0011-6

Méndez, J., Hurtado-Caycedo, C., PÃiez, F., Bateman, A., PinzÃ3n, C., Gutiérrez, C., et al. (2013). EvaluaciÃ3n de los Programas Para la AtenciÃ3n del FenÃ3meno de la Niña 2010-2011. Bogota: Fedesarrollo.

Magrin, G., Marengo, J., Boulanger, J.-P., Buckeridge, M., Castellanos, E., Poveda, G., et al. (2014). “Central and South America,” in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maynard-ford, M., Phillips, E., and Chirico, P. (2008). Mapping Vulnerability to Disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1900-2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Geological. doi: 10.3133/ofr20081294

Mbaye, L., and Drabo, A. (2017). Natural disasters and poverty reduction: do remittances matter? CESifo Econ. Stud. 63, 481–499. doi: 10.1093/cesifo/ifx016

Miller, S., and Keipi, K. (2005). Strategies and Financial Instruments for Disaster Risk Management in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Mu, J., and Chen, Y. (2016). Impacts of large natural disasters on regional income. Nat. Hazards 83, 1485–1503. doi: 10.1007/s11069-016-2372-3

Nagy, G., Filho, W., Azeiteiro, U., Heimfarth, J., Verocai, J., and Li, C. (2018). An assessment of the relationships between extreme weather events, vulnerability, and the impacts on human wellbeing in Latin America. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:1802. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091802

Neumayer, E., Plumper, T., and Barthel, F. (2014). The political economy of natural disaster damage. Glob. Environ. Change 24, 8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.011

Paleari, S. (2019). Disaster risk insurance: a comparison of national schemes in the EU-28. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 35:101059. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.12.021

Paudel, Y. (2012). A comparative study of public—private catastrophe insurance systems: lessons from current practices. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 37, 257–285. doi: 10.1057/gpp.2012.16

Rebotier, J. (2012). Vulnerability conditions and risk representations in Latin-America: framing the territorializing urban risk. Glob. Environ. Change 22, 391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.12.002

Rodríguez Esteves, J. (2004). Desastres de origen natural en México: el papel del FONDEN. Estud. Soc. 12, 74–96.

Rubin, O., and Rossing, T. (2012). National and local vulnerability to climate-related disasters in Latin America: the role of social asset-based adaptation. Bull. Lat. Am. Res. 31, 19–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9856.2011.00607.x

Schwarze, R., Schwindt, M., Weck-Hannemann, H., Raschky, P., Zahn, F., and Wagner, G. (2011). Natural Hazard Insurance in Europe: tailored responses to climate change are needed. Environ. Policy Govern. 21, 14–30. doi: 10.1002/eet.554

Shen, G., and Hwang, S. (2019). Spatial–temporal snapshots of global natural disaster impacts revealed from EM-DAT for 1900-2015. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk 10, 912–934. doi: 10.1080/19475705.2018.1552630

Smit, B., Burton, I., Klein, R., and Street, R. (1999). The Science of adaptation: a framework for assessment. Mitigat. Adaptat. Strateg. Glob. Change 4, 199–213. doi: 10.1023/A:1009652531101

Smolka, A. (2006). Natural disasters and the challenge of extreme events: risk management from an insurance perspective. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 364, 2147–2165. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2006.1818

Solecki, W., Leichenko, R., and O'Brien, K. (2011). Climate change adaptation strategies and disaster risk reduction in cities: connections, contentions, and synergies. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 3, 135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2011.03.001

Stillwell, H. (1992). Natural hazards and disasters in Latin America. Nat. Hazards 6, 131–159. doi: 10.1007/BF00124620

Surminski, S., and Oramas-Dorta, D. (2014). Flood insurance schemes and climate adaptation in developing countries. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 7, 154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2013.10.005

Tsubokawa, H. (2004). Japan's earthquake insurance system. J. Jpn. Assoc. Earthquake Eng. 4, 154–160. doi: 10.5610/jaee.4.3_154

UNISDR (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Geneva: United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction.

Vatsa, K., Rodríguez, M., Terrazas, V., Maldonado, A., Weichselgartner, J., and Mechler, R. (2003). Manejo Integral de Riesgos por Comunidades y Gobiernos Locales: Componente IV: Consideraciones Financieras Para las Capacidades Locales en el Manejo de Desastres Naturales. Washington, DC: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo/Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH.

Wei, J., Wang, A., and Wang, F. (2019). Humanitarian organizations in international disaster relief: understanding the linkage between donors and recipient countries. Voluntas 30, 1212–1228. doi: 10.1007/s11266-019-00172-x

Xu, J., Wang, Z., Shen, F., Ouyang, C. H., and Tu, Y. (2016). Natural disasters and social conflict: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 17, 38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.04.001

Keywords: risk disaster reduction, public insurance, adaptation, financial instruments, disaster mitigation

Citation: Szlafsztein CF (2020) Extreme Natural Events Mitigation: An Analysis of the National Disaster Funds in Latin America. Front. Clim. 2:603176. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2020.603176

Received: 05 September 2020; Accepted: 27 October 2020;

Published: 23 November 2020.

Edited by:

Chris C. Funk, United States Geological Survey (USGS), United StatesReviewed by:

Jose A. Marengo, Centro Nacional de Monitoramento e Alertas de Desastres Naturais (CEMADEN), BrazilJuan Antonio Rivera, CONICET Argentine Institute of Nivology, Glaciology and Environmental Sciences (IANIGLA), Argentina

Copyright © 2020 Szlafsztein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claudio Fabian Szlafsztein, aW9zZWxlQHVmcGEuYnI=

Claudio Fabian Szlafsztein

Claudio Fabian Szlafsztein