94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 13 December 2023

Sec. Parasite and Host

Volume 13 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1278041

This article is part of the Research TopicFunctional Genomics for Understanding Arthropods and Arthropod-Borne DiseasesView all 4 articles

Eliana F. G. Cubillos1

Eliana F. G. Cubillos1 Pavla Snebergerova1,2

Pavla Snebergerova1,2 Sarka Borsodi1

Sarka Borsodi1 Dominika Reichensdorferova1

Dominika Reichensdorferova1 Viktoriya Levytska2

Viktoriya Levytska2 Masahito Asada3

Masahito Asada3 Daniel Sojka2*

Daniel Sojka2* Marie Jalovecka1,2*

Marie Jalovecka1,2*Babesia divergens is an emerging tick-borne pathogen considered as the principal causative agent of bovine babesiosis in Europe with a notable zoonotic risk to human health. Despite its increasing impact, considerable gaps persist in our understanding of the molecular interactions between this parasite and its hosts. In this study, we address the current limitation of functional genomic tools in B. divergens and introduce a stable transfection system specific to this parasite. We define the parameters for a drug selection system hdhfr-WR99210 and evaluate different transfection protocols for highly efficient generation of transgenic parasites expressing GFP. We proved that plasmid delivery into bovine erythrocytes prior to their infection is the most optimal transfection approach for B. divergens, providing novel evidence of Babesia parasites’ ability to spontaneously uptake external DNA from erythrocytes cytoplasm. Furthermore, we validated the bidirectional and symmetrical activity of ef-tgtp promoter, enabling simultaneous expression of external genes. Lastly, we generated a B. divergens knockout line by targeting a 6-cys-e gene locus. The observed dispensability of this gene in intraerythrocytic parasite development makes it a suitable recipient locus for further transgenic application. The platform for genetic manipulations presented herein serves as the initial step towards developing advanced functional genomic tools enabling the discovery of B. divergens molecules involved in host-vector-pathogen interactions.

Babesia divergens, is an intraerythrocytic apicomplexan parasite transmitted by the tick Ixodes ricinus and is the primary cause of bovine babesiosis in Europe having a significant impact on the cattle industry (Zintl et al., 2003). Notably, human babesiosis caused by B. divergens is associated with severe and fatal outcomes of the disease, making it a zoonosis of concern in Europe (Hildebrandt et al., 2021). In comparison to other bovine infecting Babesia species, there is limited knowledge about the biology of B. divergens, and many questions concerning crucial processes of this parasite remain unanswered. Further investigation of mechanisms responsible for host cell invasion, intracellular parasitism, and parasite-host interactions, is required to improve our understanding of B. divergens and to develop innovative strategies aimed at preventing its transmission (Jalovecka et al., 2019).

The identification of factors responsible for the virulence and pathogenesis of B. divergens faces obstacles, primarily due to the absence of genetic manipulation tools necessary to study individual function of encoded proteins and enzymes. Transfection protocols and reverse genetics techniques are well established in several apicomplexans, including the primary model species Plasmodium and Toxoplasma (Limenitakis and Soldati-Favre, 2011; Vieira et al., 2021), but also in Cryptosporidium (Vinayak et al., 2015) and Theileria (De Goeyse et al., 2015). These tools are key to functionally characterize proteins and enzymes and determine them as potential targets for intervention. Babesia-specific transfection systems, both transient and stable, have been successfully developed for various Babesia species, including Babesia bovis (Suarez and McElwain, 2009; Suarez and McElwain, 2010), Babesia ovata (Hakimi et al., 2016), Babesia bigemina (Silva et al., 2016), Babesia gibsoni (Liu et al., 2018a), Babesia ovis (Rosa et al., 2019), Babesia microti (Jaijyan et al., 2020) and Babesia duncani (Wang et al., 2022). Such systems have proven to be vital tools for conducting comparative functional genomic analyses, providing valuable insights into the parasite’s biology. These insights include understanding host-pathogen interactions during the blood cycle (Asada et al., 2012a), as well as interactions between the parasite and tick vectors (Hussein et al., 2017). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a reliable platform for B. divergens-specific transgenic techniques to study key steps of this parasite’s life cycle.

The introduction of a transfection system into a new model species requires a number of prerequisites, including continuous in vitro culture, the availability of the parasite’s genome, a reliable drug selection system and a highly-efficient transfection protocol (Suarez et al., 2017). In B. divergens, the continuous in vitro cultivation in human (Lobo, 2005) and bovine erythrocytes (Malandrin et al., 2004) is well-established. The B. divergens genome has been sequenced (Cuesta et al., 2014) and recent advances in comparative genomic data are also available (González et al., 2019; Rezvani et al., 2022). This knowledge, in combination with the described transfection parameters, selection drugs and electroporation protocols of related Babesia species, provide a background for the development of genetic tools specific to B. divergens. Thus, in this work, we define the parameters for a stable and highly efficient B. divergens-specific transfection system as the initial step for the establishment of a wider range of functional genomic tools for this parasite.

Babesia divergens strain 2210A G2 was cultivated in vitro in the suspension of commercially available bovine erythrocytes (BioTrading) under constant conditions of 37°C and 5% CO2 by a previously described procedure (Jalovecka et al., 2018). The cultivation media was composed of RPMI 1640 (Lonza), amphotericin B (Merck, c=250µg/ml), gentamicin sulfate (Merck, c=10mg/ml) and supplemented with heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Capricorn) in 20% volume. Culture growth was monitored on thin blood smears stained by Diff-Quik (Siemens, Germany) under the BX53F light microscope (Olympus) at a magnification of 1000×.

To introduce a large-scale parasitemia monitoring method, we employed nuclear staining followed by a flow cytometry analysis. Infected red blood cells were pelleted, washed with 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.025% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature (RT). The fixed cells were subsequently washed twice with PBS (600×g, 3 min) and stored at 4°C for up to three weeks. To analyze parasitemia, the cells were stained with 0.02mM Ethidium Homodimer 1 (EthD-1, Biotinum) diluted in PBS for 30 min at RT. Afterwards, the stained samples were washed twice (600×g, 3 min) with PBS and analyzed using a FACS CantoII flow cytometer and Diva software provided by BD Biosciences, including the determination of Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) values for the GFP signal. When needed, flow cytometry was utilized to determine the GFP signal from transgenic parasites. Fixed parasites samples stained with EthD-1 were incubated with an Anti-GFP Polyclonal Antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488 (Thermofisher), diluted 100× in PBS for 30 min. The samples were then washed twice with PBS (600×g, 3 min) and analyzed in the same manner as stated above.

The inhibitory effect of two standard selection drugs, WR99210 (selection marker hdhfr - human dihydrofolate reductase - gene, kindly provided by Jacobus Pharmaceutical) and blasticidin S (BSD, selection marker blasticidin S deaminase gene, Merck) was tested in B. divergens in vitro system. Inhibitory assays were conducted in 96-well plate format in biological triplicates for 8 consecutive days. Media supplemented either with WR99210 (concentration ranging from 20 nM to 0.019 nM) or BSD (concentration ranging from 16 µg/ml to 0.0156 µg/ml) were exchanged in an interval of 48 hours, DMSO diluted in cultivation media served as solvent control. Culture samples were collected at two-day intervals, fixed, and analyzed using flow cytometry as stated in chapter 2.1.

To construct B. divergens-specific plasmids for both episomal and intragenomic gfp expression, we first identified, PCR amplified, and sequenced B. divergens-specific untranslated regions (UTRs): the 5’ UTR of the actin gene (Bdiv_007890; length: 2002 bp), the 5’ UTR of the elongation factor tu gtp binding domain family protein (ef-tgtp) gene (Bdiv_030590; length: 696 bp), and the 3’ UTR of the chloroquine resistance transporter (CRT) gene (Bdiv_036760; length: 1496 bp). The coding sequences of gfp, hdhfr, and bsd genes were obtained from B. bovis-specific plasmids (Asada et al., 2015). The target locus for intragenomic insertion of the GFP-expressing cassette, the B. divergens 6-cys-e gene (6-cysteine (E), Bdiv_004560c), and its 5’ and 3’ UTRs, were PCR amplified and sequenced. The final plasmid included two homology regions (HRs): HR1 (length: 817 bp) spanning the 5’ UTR and the beginning of the gene CDS, and HR2 (length: 802 bp) spanning the end of the gene CDS and the 3’ UTR to allow homologous recombination.

The plasmids were assembled in several subsequent steps using NEBuilder® HiFi DNA Assembly Kit (New England BioLabs) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The procedure involved the linearization of the plasmid’s backbone using specific restriction enzymes and PCR amplification of the desired loci. Detailed information about individual plasmid parts and restriction sites are depicted in plasmid maps (Supplementary Data; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24433384.v1). After assembly, the plasmids were transformed into NEB 5-alpha Competent E. coli cells (New England Biolabs) and grown on LB agar plates supplemented with ampicillin, following the manufacturer’s protocols. Individual colonies obtained from the plates were grown in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin for 12-16 hours, and the plasmid DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin® Plasmid kit (Macherey-Nagel) and verified by sequencing. To isolate and purify plasmid DNA on a large scale for transfections, the NucleoBond® Xtra Midi kit (Macherey-Nagel) was employed.

The plasmids designed for episomal GFP expression were transfected in circular form, as detailed in the subsequent chapter. The plasmid intended for intragenomic gfp expression was linearized using the FseI restriction enzyme before the transfection.

Three different protocols were employed for the transfection of B. divergens parasites: electroporation of infected RBCs (iRBCs), electroporation of free merozoites, and electroporation of uninfected bovine RBCs (uRBCs). All transfection protocols included a “plasmid solution”: 10 µg of the plasmid that was precipitated in ethanol, resuspended in 20 µl of filtered milliQ water, and mixed with 100 µl of nucleofector solution from Basic Parasite Nucleofector® Kit 2 (Lonza). Transfections were performed in a device ‘Amaxa’ Nucleofector 2b (Lonza) and an electric pulse using the V-024 program was applied to the mixture of plasmid solution and iRBCs/free merozoites/uRBCs solution. Transfected samples were then transferred into a mixture of 2 ml cultivation media and 100 µl of uRBCs/uRBCs/iRBCs, respectively. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, the medium was replaced, and the 5 nM WR99210 selection drug was added. The medium containing the drug was changed daily during the experiments.

Transfection of B. divergens iRBCs was adapted from the previously described protocol for B. bovis (Suarez et al., 2007; Asada et al., 2012b): 100 µl of iRBCs with ~15% parasitemia were washed in pre-warmed PBS and mixed with the plasmid solution. Transfection of free merozoites included 100 μl of iRBCs with ~15% parasitemia that were washed in pre-warmed PBS and filtered twice with a 1.2 µm Acrodisc® syringe filter unit (Pall corporation) as described in (Hakimi et al., 2021a). The filtered suspension was then centrifuged (600×g, 3 min) to remove the residues of RBCs, and free merozoites resuspended in 100 μl of PBS were mixed with the plasmid solution. The transfection of uRBCs (also referred to as DNA or plasmid pre-loading of RBCs) was adapted from P. falciparum protocol (Deitsch et al., 2001). Briefly, 100 μl of uRBCs were washed with PBS and mixed with the plasmid solution. After the transfection, the mixture of DNA-loaded uRBCs was mixed with 2 ml cultivation media supplemented with 100 µl of iRBCs. Three independent experiments were conducted to evaluate the efficiency of the above presented different transfection protocols.

To obtain clonal populations with correctly integrated plasmid, the parasites transfected with the linearized plasmid were subjected to serial dilutions: 0.3 parasites were seeded per well in a 96-well plate and grown for 10 days with medium exchanges every second day. Obtained clones were expanded for DNA extraction and the correct integration of the plasmid was confirmed by PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 1.

To analyze the growth pattern of GFP-expressing and knockout (6-cys-e gene disruption) parasites, their intraerythrocytic development was monitored for 96 hours and compared to a wild-type parasite lineage. All experiments were conducted in biological triplicates, and parasitemia was determined every 12 hours through blood smears and flow cytometry.

B. divergens gDNA was isolated from iRBCs (~10% parasitemia) using the NucleoSpin® Blood DNA isolation kit (Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at -20°C. PCR reactions were performed in the T100 Thermal Cycler (BioRad) following the protocol for Q5® High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England BioLabs) and visualized on agarose gel using Gel logic 112 transilluminator (Merck).

Total RNA from B. divergens in vitro cultures was extracted using TRI Reagent® (Merck) followed by chloroform phase separation and isolation with the NucleoSpinRNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel). To eliminate gDNA residues, the RNA samples were treated with the TURBO DNA-free™ Kit (Invitrogen) and stored at -80°C. Reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg of RNA using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche), following the manufacturer’s protocol, and stored at -20°C. Transcript levels of gfp and hdhfr genes were quantified in biological as well as technical triplicates using LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche) with specific primers for each transcript (Supplementary Table 1) in CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad). The relative gfp and hdhfr genes expression was normalized to the B. divergens gapdh gene (Bdiv_010720) using the ΔΔCt method (Jalovecka et al., 2016).

GFP-expressing B. divergens in vitro cultures were smeared, air-dried and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.075% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 30 min at RT on Superfrost Plus™ Adhesion Microscope Slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After fixation, the samples were washed with PBS (3 × 5 min) and incubated with 0.01% Triton X-100 (Merck) diluted PBS for 30 min at RT to permeabilize cell membranes. Anti-GFP Polyclonal Antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488 (Thermofisher) was diluted 100× in 0.01% Triton X-100 and applied to samples for 1 hour at RT. Subsequently, the samples were washed in PBS (3 × 5 min) and stained with 300 nM DAPI diluted in PBS for 10 min at RT. After another round of washing with PBS (3 × 5 minutes), the samples were mounted in DABCO (Merck). GFP signal was examined by BX53F fluorescence microscope (Olympus) and processed in Fiji (ImageJ) software.

The statistical analyses, IC50 calculations, and graphs were created in GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0a). The inhibitory effect of selection drugs was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the Bartlett test passed. The expression of gfp and hdhfr genes was compared with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

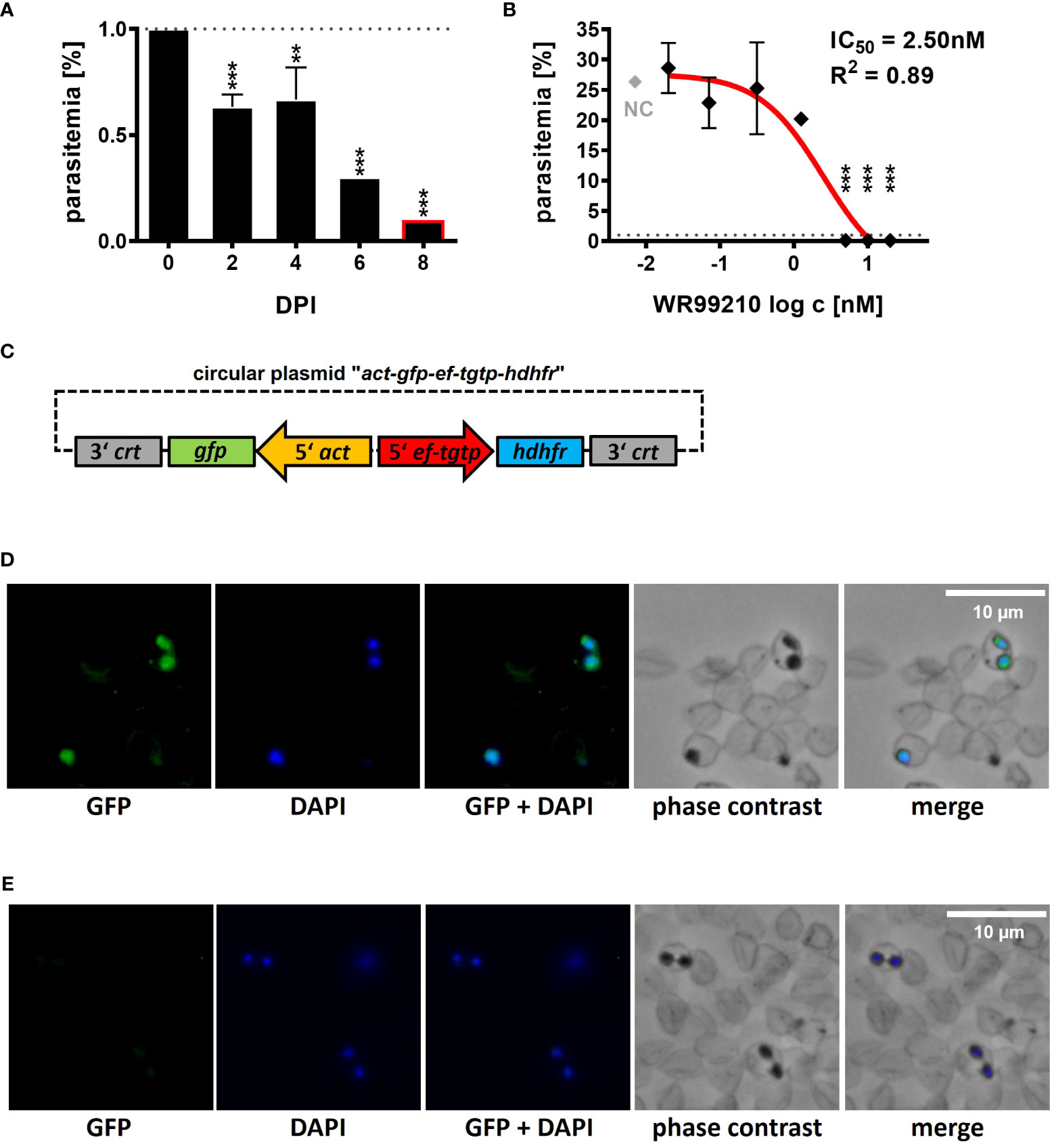

Since the establishment of stable transfection system requires a reliable drug selection, we conducted tests to assess the impact of two commonly used selection drugs, WR99210 and BSD, on the growth of B. divergens. Both drugs demonstrated inhibitory activity against B. divergens in our in vitro system. WR99210 was found to be effective at a concentration of 5 nM (Figure 1A), while BSD exhibited inhibitory effects at a concentration of 4 μg/ml (equivalent to 8.72 μM) (Supplementary Figure 1A).

Figure 1 Introduction of a B. divergens GFP-expressing reporter line. (A) Inhibition of B. divergens in vitro growth in bovine RBCs by 5nM WR99210. (B) Determination of IC50 value for WR99210 using non-linear regression with a dose-response curve and regression factor (R2) based on B. divergens parasitemia levels on 8 DPI. Individual concentrations were transformed (log c) prior to analysis. The result represents the mean of three independent replicates, with error bars indicating standard deviations. The grey dotted line represents the initial parasitemia (1%). NC, non-treated culture; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; DPI, days post infection; **,p < 0.01; ***,p < 0.001. One-way ANOVA was performed for statistical analysis. (C) Circular plasmid act-gfp-ef-tgtp-hdhfr used for the introduction of a GFP-expressing B. divergens reporter lineage from an extrachromosomal replicating episome. crt, chloroquine resistance transporter; gfp, green fluorescent protein; act, actin; ef-tgtp, Elongation Factor Tu GTP binding domain family protein; hdhfr, human dihydrofolate reductase. Detailed map is included in Supplementary Data and available online https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24433384.v1. (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy of episomally GFP-expressing parasites selected with WR99210. (E) Immunofluorescence microscopy of wild-type parasites. Fixed thin blood smears were stained with Anti-GFP Polyclonal Antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488, and nuclei were stained with DAPI. Dotted red circles indicate RBCs.

At 5 nM, WR99210 significantly inhibited parasite growth by 2 days post infection (DPI), reducing parasitemia to 0.1% by 8 DPI compared to the initial 1% (0 DPI, Figure 1A), whereas the non-treated culture (NC) grew up to a parasitemia of 25.35 ± 2.33% on 8 DPI (Figure 1B). Inhibitory effects were also observed at 10 and 20 nM concentrations, while concentrations of 1.25, 0.31, 0.07, and 0.02 nM did not exhibit significant growth inhibition. The IC50 of WR99210 in B. divergens bovine RBCs, determined from parasitemia values measured on 8 DPI, was calculated 2.50 nM with an R2 value of 0.89 (Figure 1B).

BSD at 4 μg/ml (8.72 μM) significantly decreased B. divergens growth: on 8 DPI, parasitemia decreased to 0.4% ± 0.1 from an initial 1% (0 DPI, Supplementary Figure 1A), while the NC group showed 23.85% ± 2.48% parasitemia (Supplementary Figure 1B). BSD also exhibited inhibitory effects at concentrations of 8 and 16 μg/ml (17.43 and 34.86 μM, respectively), but no impact on growth was observed with concentrations of 1, 0.25, 0.0625, and 0.015 μg/ml (equivalent to 2.18, 0.54, 0.14 and 0.03 μM, respectively). The IC50 of BSD in B. divergens in vitro system was calculated as 2.61 μg/ml (5.69 μM), with an R2 value of 0.90, based on parasitemia values measured on 8 DPI (Supplementary Figure 1B).

With a reliable selection system, we further proceeded to develop a B. divergens GFP-expressing reporter line. We designed and de novo constructed a circular plasmid “act-gfp-ef-tgtp-hdhfr” containing the GFP reporter cassette, where the gfp gene expression was driven by the actin gene promoter. The hdhfr gene, conferring resistance to the drug WR99210, was under the control of the promoter of the Elongation Factor Tu GTP binding domain family protein (ef-tgtp) (Figure 1C; Supplementary Data; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24433384.v1). The plasmid was delivered into B. divergens-infected bovine RBCs, and WR99210-resistant parasites emerged after 12 to 14 days post transfection (DPT). By 16 to 18 DPT, parasitemia reached 5%. Throughout this study, the GFP fluorescence signal was consistently detected (Figure 1D) under WR99210 pressure. No GFP signal was detected in wild-type parasites (Figure 1E).

Similarly, the BSD-resistant parasites appeared between 12 to 15 DPT after delivery of the modified plasmid in which the same promoter was used to drive the expression of the blasticidin S deaminase gene as in the above-mentioned validated hdhfr-WR99210 selection system. However, despite several attempts to stabilize the culture, the parasitemia remained low, and the parasites were no longer detectable after 24 DPT (data not shown). Due to the low parasitemia, the GFP signal could not be adequately confirmed. Consequently, in the following experiments, the hdhfr-WR99210 selection system was used.

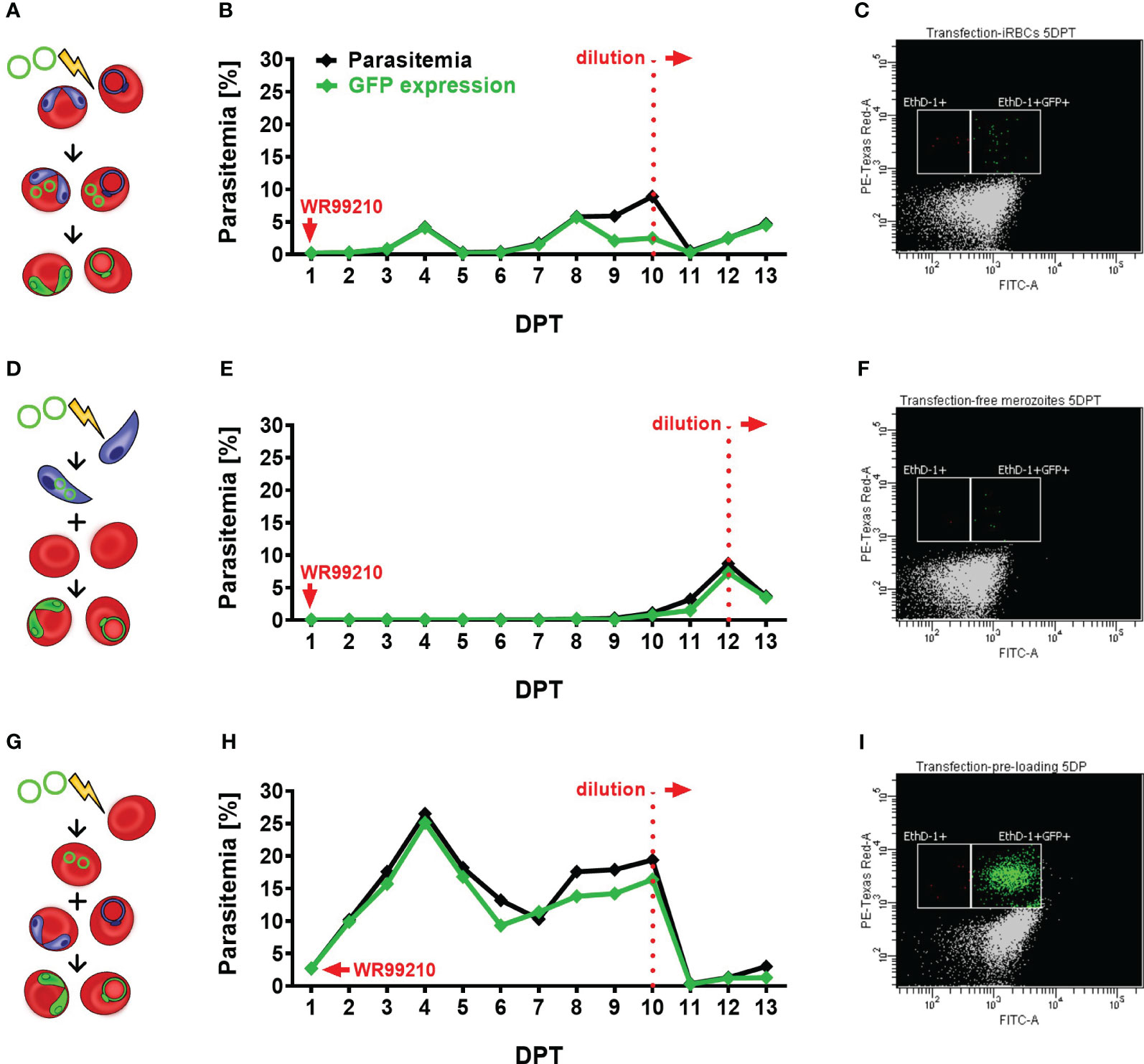

Since the GFP-hdhfr expression plasmid was verified, we proceeded to optimize the transfection protocol, with the aim of establishing a versatile platform for B. divergens-specific transgenic techniques. To achieve this, we explored three different methods for delivering the circular plasmid “act-gfp-ef-tgtp-hdhfr” into parasite cells: the widely used and well-established direct iRBCs transfection (Figure 2A) (Suarez and McElwain, 2010; Asada et al., 2012b), the less common but validated method of electroporation of Babesia free merozoites (Figure 2D) (Suarez and McElwain, 2008), and lastly, the plasmid delivery into uRBCs before their infection (Figure 2G), followed by their coculturing with wild-type (WT) parasites. The latter method of erythrocytes pre-loading has not been previously validated in any Babesia-transgenic system, but in P. falciparum, it has demonstrated higher efficiency when compared to other methods (Deitsch et al., 2001; Skinner-Adams et al., 2003; Hasenkamp et al., 2012).

Figure 2 Assessment of different transfection protocols in B. divergens in vitro system. (A–C) Direct transfection of iRBCs. (A) Schematic representation of the transfection protocol, (B) parasitemia and GFP fluorescence signal monitoring in transfected parasite culture, (C) parasitemia of GFP-expressed parasites on 5 DPT. (D–F) Electroporation of free merozoites: (D) Schematic representation of the transfection protocol, (E) parasitemia and GFP fluorescence signal monitoring in transfected parasite culture, (F) parasitemia of GFP-expressed parasites on 5 DPT. (G–I) Plasmid delivery into uRBCs prior to their infection: (G) Schematic representation of the transfection protocol, (H) parasitemia and GFP fluorescence signal monitoring in transfected parasite culture, (I) parasitemia of GFP-expressed parasites on 5 DPT. In all experiments, parasite growth and GFP expression were evaluated using flow cytometry. Culture samples were fixed on daily intervals, stained with EthD-1 to determine total parasitemia, and labeled with an Anti-GFP Polyclonal Antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488. The graphs represent the results of a single experiment, the observed outcome has been confirmed by two additional independent experiments. iRBCs, infected red blood cells; uRBCs, uninfected RBCs; GFP, green fluorescent protein; EthD-1, Ethidium Homodimer 1; DPT, days post transfection.

After comparing the three transfection methods (Figure 2), the plasmid pre-loading into uRBCs proved to be the most efficient transfection protocol in B. divergens in vitro system (Figures 2H, I) in all three independent experiments. The observed GFP signal from parasites confirmed the spontaneous uptake of plasmid DNA from the bovine host cell cytoplasm into B. divergens intraerythrocytic stages. Additionally, parasitemia of nearly 3% of GFP-expressing parasites was detected 1 DPT (Supplementary Figure 2C) and gradually increased up to 17%. However, the parasites showed signs of stress due to overgrowth, likely associated with the decreased ratio of GFP expression to total parasitemia observed from 8 DPT. Thus, the cultures were diluted on 10 DPT, when the MFI of GFP signal was measured as 1411, to avoid stressful conditions that could interfere with parasite growth. Following dilution, the parasites quickly re-emerged with MFI value on 11DPT 1419, and parasitemia exceeded 3% by 13 DPT. Throughout the experiment, when comparing total parasitemia with the number of GFP-expressing parasites, the same trend of growth was observed. This confirms the successful transfection and plasmid maintenance by the parasites. Moreover, this technique demonstrated the highest viability compared to the other tested methods, as evidenced by a blood smear taken on 1 DPT (Supplementary Figure 2F). After the direct electroporation of iRBCs, a harmful effect on parasites was observed, as evidenced by the presence of multiple dead parasites on 1 DPT and a high rate of RBC lysis (Supplementary Figures 2A, D). Despite this, the GFP-expressing parasite population gradually increased over time, reaching over 5% parasitemia by 8 DPT, but remained at lower levels compared to the pre-loaded transfectants (Figures 2D, E). Signs of overgrowth were detected from 9 DPT, necessitating dilution of the culture on 10 DPT, when MFI reached 626. Following dilution, the parasite population re-emerged with detected MFI 826 on 11 DPT and reached a stable parasitemia with sustained GFP expression. In contrast, the electroporation of B. divergens free merozoites displayed delayed appearance of transgenic parasites (Figures 2F, G). Despite a few viable parasites being detected on 1 DPT (Supplementary Figures 2B, E), the first GFP-expressing parasites only emerged around 10 DPT. This delay may be attributed to the fragility of the free merozoite population, resulting in reduced merozoite viability after electroporation, or a low efficiency of the transfection protocol, or a combination of both factors. By 12 DPT, the parasitemia of transgenic parasites exceeded 7% with MFI value 967, and the observed majority of GFP-expressing parasites indicates successful transformation. We then proceeded with culture dilution to observe whether parasites would be able to re-emerge. Indeed, after the dilution, GFP-expressing parasites exponentially multiplied with MFI value 1726 detected on 13 DPT, indicating the continuous growth of a successfully transfected population.

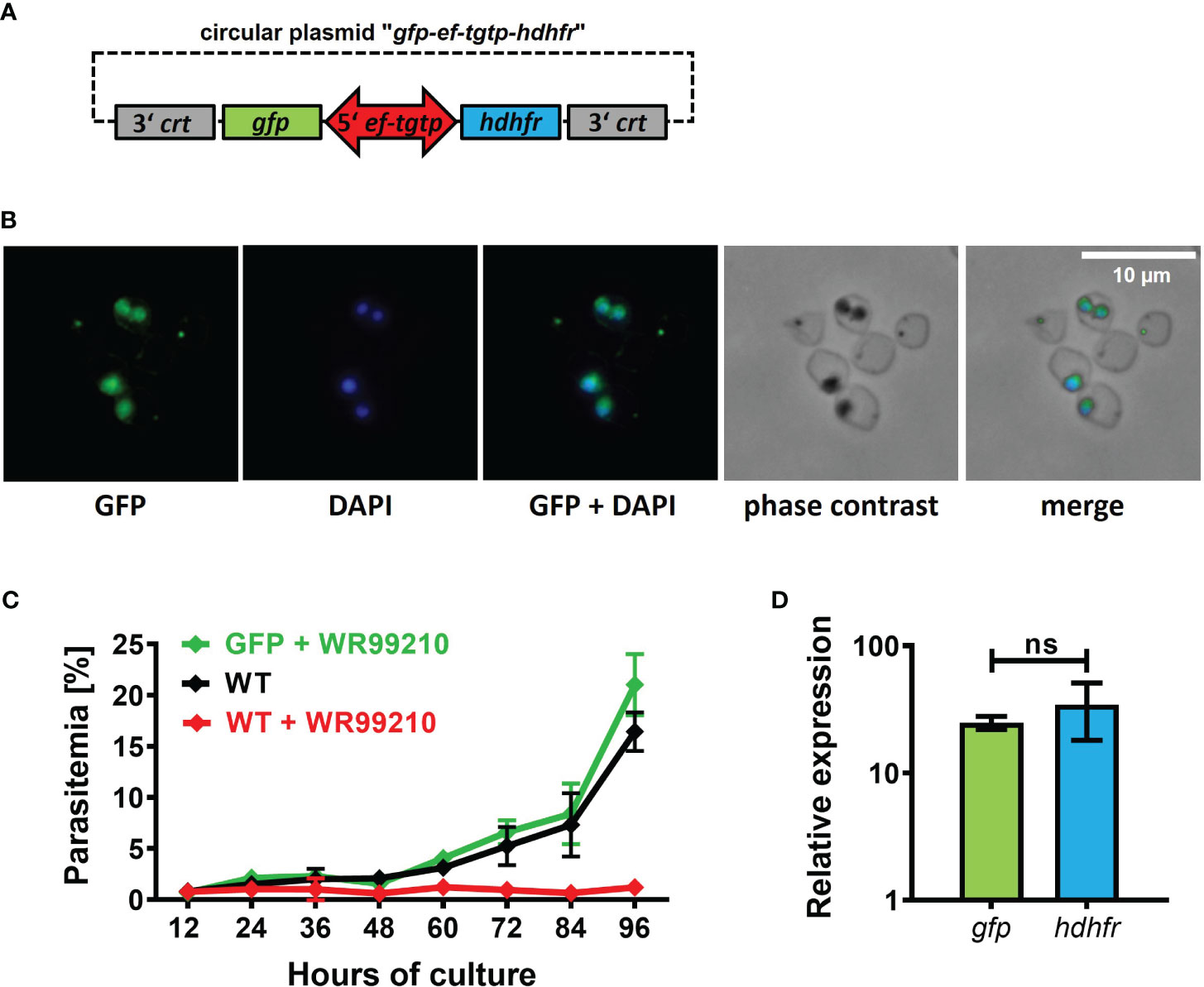

In most Babesia species, the promoters controlling the expression of elongation factor-1 alpha (ef1-α) exhibit robust, constitutive, and bidirectional activity in transgenic applications (Liu et al., 2018b). Consequently, when introducing transgenic applications into our B. divergens system, we selected the promoter of Bdiv_030590, a gene annotated in PiroplasmaDB as “the translation elongation factor EF-1, subunit alpha protein, putative”. However, a more comprehensive in silico analysis of the Bdiv_030590 gene revealed distinct differences from the typical structure of well characterized ef1-α promoters in other Babesia species (Suarez et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018b; Wang et al., 2022). Instead, the arrangement of Bdiv_030590 gene closely resembles the locus of syntenic gene BBOV_II000640, which codes for Elongation factor Tu GTP binding domain family protein (Dr. Carlos Suarez, personal communication). Therefore, we designated the promoter of Bdiv_030590 gene as the “ef-tgtp”. Based on its position between two genes (Bdiv_030590 and Bdiv_030580c) in opposite direction, we hypothesized that it might possess bidirectional activity, allowing us to reduce the size of the original plasmid “act-gfp-ef-tgtp-hdhfr” to enhance its versatility. By removing the actin promoter sequence from the original plasmid, we created a circular plasmid “gfp-ef-tgtp-hdhfr” which contained both the GFP reporter cassette and the hdhfr gene-based resistance cassette under the control of the ef-tgtp promoter in a head-to-head orientation (Figure 3A; Supplementary Data; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24433384.v1). The stable GFP expression in episomally transfected parasites and their continuous growth under drug selection pressure confirmed a bidirectional activity of the ef-tgtp promoter (Figures 3B, C). Moreover, the promoter activity was symmetrical, as both transcripts of the gfp and hdhfr genes exhibited expression levels with no significant difference (Figure 3D), which makes this promoter a widely adaptable tool for other transgenic applications.

Figure 3 Validation of novel bidirectional promoter with symmetrical activity. (A) Circular plasmid gfp-eftgtp-hdhfr employing bidirectional promoter of the elongation factor tu gtp binding domain family protein (eftgtp) gene. crt, chloroquine resistance transporter; gfp, green fluorescent protein; hdhfr, human dihydrofolate reductase. Detailed map is included in Supplementary Data and available online https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24433384.v1. (B) Episomally GFP-expressing parasites selected with WR99210. Fixed thin blood smears were stained with an Anti-GFP Polyclonal Antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Dotted red circles indicate RBCs. (C) The growth curve of GFP-expressing parasites under WR99210 selection pressure was compared to WT non-treated parasites and WR99210 treated. Stained blood smears were employed for growth monitoring. WT, wild-type (D) The relative quantification of gfp and dhfr gene transcripts driven by the eftgtp bidirectional promoter. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was performed for statistical analysis. ns, not significant.

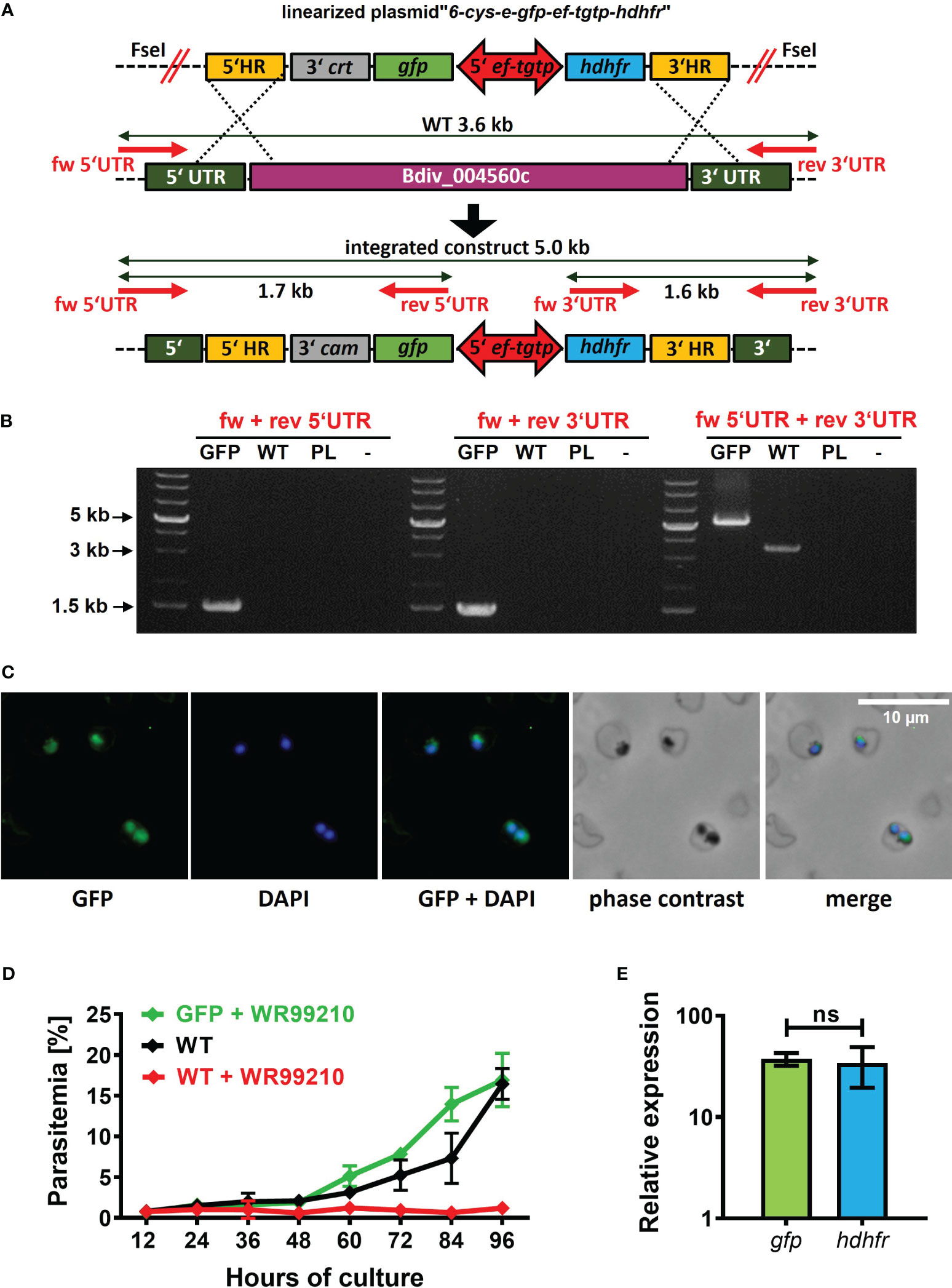

To complete the development of a B. divergens-specific transgenic platform, we proceeded with the direct insertion of a foreign gene into the parasite genome. In already established Babesia-transgenic systems, this process is commonly achieved through homologous recombination mechanisms (Suarez et al., 2017). To target a dispensable locus/gene for parasite blood stages, we chose the B. divergens 6-cys-e gene (Bdiv_004560c). The ortholog of this gene in B. bovis has been demonstrated to be dispensable for the intraerythrocytic life cycle of this parasite. To introduce the GFP reporter cassette into the selected locus, we designed the plasmid “6-cys-e-gfp-ef-tgtp-hdhfr” (Supplementary Data; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24433384.v1). This plasmid contains two homology regions (HRs) that are homologous to the 5’ and 3’ UTRs of 6-cys-e gene. Within these HRs, the GFP reporter cassette and the hdhfr gene-based resistance cassette were positioned in a head-to-head orientation, separated by the ef-tgtp promoter (Figure 4A). The pre-loading of the linearized plasmid into bovine uRBCs resulted in the emergence of WR99210-resistant parasites on 12 DPT that gradually increased, surpassing 5% parasitemia by 15 DPT. Following clonal selection, the successful intragenomic insertion was confirmed (Figure 4B), and GFP signal was detected (Figure 4C). Furthermore, the symmetrical activity of ef-tgtp bidirectional promoter was reconfirmed (Figure 4E). The continuous growth of the obtained clonal population under the drug pressure with no significant differences (Figure 4D) confirms that the expression of the 6-cys-e gene is not essential for B. divergens intraerythrocytic multiplication. The dispensability of the 6-cys-e gene makes it a suitable recipient locus for more advanced B. divergens-specific transgenic systems requiring target integration of the parasite genome. However, the inserted sequences should be driven by external and constitutive promoters to assure stable expression of the transgenes.

Figure 4 Targeted B. divergens intragenomic insertion. (A) Intragenomic insertion of GFP reporter cassette into B. divergens 6-cys-e gene (Bdiv_004560c) using linearized plasmid “6-cys-e-gfp-ef-tgtp-hdhfr.” HR, homology regions; crt, chloroquine resistance transporter; gfp, green fluorescent protein; ef-tgtp, Elongation Factor Tu GTP binding domain family protein; hdhfr, human dihydrofolate reductase; UTR, untranslated regions; WT, wild-type; red arrows represent positions of primers used for integration test. Detailed map is included in Supplementary Data and available online https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24433384.v1. (B) Integration test demonstrating the correct integration of both the GFP reporter cassette and the hdhfr gene-based resistance cassette into desired locus. PL, plasmid. (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy capturing GFP expression in clonal transgenic parasites. Fixed thin blood smears were stained with an Anti-GFP Polyclonal Antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Dotted red circles indicate RBCs. (D) The growth curve of clonal transgenic parasites under WR99210 selection pressure was compared to wild-type (WT) non-treated parasites and WR99210 treated. Growth curves were determined through blood smears. (E) The relative quantification of gfp and dhdfr gene transcripts driven by the ef-tgtp bidirectional promoter. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was performed for statistical analysis. ns, not significant.

In this study, we introduce a stable and highly efficient transfection protocol for B. divergens, an economically and medically important European tick-transmitted apicomplexan parasite. We established B. divergens-specific platform for genetic manipulations within the bovine RBCs cultivation system with the goal of advancing the development of functional genomic tools for this parasite.

The establishment of a reliable selection system is the primary step in developing transgenic techniques for novel model species. In Babesia species, the human dihydrofolate reductase (hdhfr) gene, which provides resistance to the drug WR99210 (Gaffar et al., 2004), serves as the widely used selectable marker. We confirmed B. divergens’s susceptibility to WR99210, resulting in complete growth inhibition at a concentration of 5nM, which corresponds to the standard dose in Babesia transgenic systems (e.g. (Asada et al., 2012b; Hakimi et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022). Consequently, we employed this dose for successful selection of GFP-expressing B. divergens transgenic populations (Figure 1). While B. divergens displayed sensitivity to Blasticidin S (BSD) (Supplementary Figure 1), another established selection drug in Babesia transgenic systems (Suarez and McElwain, 2010), our attempts to select and maintain transgenic parasites using a 4 μg/ml (8.72 μM) concentration were unsuccessful. A recent pre-print (Elsworth et al., 2023) demonstrated successful selection of transgenic B. divergens using 20 μg/ml (43.58 μM) of BSD, suggesting the need for higher concentrations. However, BSD selection varies widely in effectiveness among different Babesia species, ranging from 2 μg/ml (4.36 μM) in B. bovis (Suarez and McElwain, 2009) to no inhibitory effects, even at 100 μg/ml (217.91 μM) in B. duncani (Wang et al., 2022). This indicates that BSD selection may not be universally applicable, necessitating further investigations to confirm its suitability for individual Babesia species.

Babesia-specific transfection protocols typically involve electroporation of infected RBCs (iRCBs) or, less commonly, transfection of free (purified) merozoites (Hakimi et al., 2021b). While the alternative approach based on vector DNA electroporation of uninfected RBCs (uRBCs) cells has proven highly effective in P. falciparum (Deitsch et al., 2001; Skinner-Adams et al., 2003; Hasenkamp et al., 2012), its application in Babesia species is still unverified. In this study, we evaluated all three listed methods and found that each produced transgenic GFP-expressing B. divergens parasites. Notably, the ‘pre-loading’ of uRBCs method resulted in higher parasitemia compared to electroporation of iRBCs or purified merozoites (Figure 2), consistent with observations in P. falciparum (Skinner-Adams et al., 2003; Hasenkamp et al., 2012). We hypothesize that this observation may be attributed to the absence of direct exposure of parasites to the intense electrical currents experienced during electroporation of iRCBs or free merozoites. Previous attempts to establish a B. ovata transfection protocol using the ‘pre-loading of uRBCs’ method were unsuccessful (Hakimi et al., 2016), possibly due to voltage and capacitance settings variations between the BioRad and the herein used Lonza (Amaxa) electroporation systems. Overall, the ‘pre-loading of uRBCs appears to be a most promising method for advancing genetic tools in B. divergens. Additionally, our findings illuminate the ability of Babesia parasites to spontaneously uptake external DNA from RBC cytoplasm, shedding new light on their intraerythrocytic development linked to disease.

The availability of Babesia genomes and the PiroplasmaDB database (Amos et al., 2022) have facilitated the identification of regulatory regions controlling gene expression. The promoters controlling the expression of elongation factor-1 alpha (ef1-α) belong to the most used regulatory regions in transgenic applications of other Babesia species (Liu et al., 2018b). Therefore, we selected the promoter of Bdiv_030590 gene, referred to as B. divergens ef1-α, putative in PiroplasmaDB for our experiments. However, the arrangement of Bdiv_030590 gene locus mirrors the structure of the syntenic gene locus coding for B. bovis Elongation Factor Tu GTP binding domain family protein, rather than the validated canonical ef1-α promoters found in other Babesia species (Suarez et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018b; Wang et al., 2022) (Dr. Carlos Suarez, personal communication). Thus, we designated the promoter employed in our study as the “ef-tgtp” and experimentally validated its ability to control external gene expression. Notably, we confirmed its constitutive bidirectional activity as the ef-tgtp promoter exhibited symmetrical activity in controlling both GFP reporter and the hdhfr-WR99210 resistance cassettes. This novel promoter has demonstrated its versatility in regulating external gene expression for various B. divergens-specific transgenic applications (Figure 3). The observed elevated GFP expression can be attributed to a combination of factors, including the use of the eg-tgtp bi-directional promoter, drug pressure, and episomal gene transcription. While our study did not identify adverse effects resulting from GFP overexpression on parasite viability, it is important to acknowledge that potential issues may arise with other proteins. Addressing such concerns would necessitate further optimization, considering all relevant expression parameters, with particular attention to the concurrent use of the same promoter for drug resistance and protein expression.

In this study, we aimed to establish a stable transfection system for B. divergens, which necessitates continuous expression of the gene of interest. This can be achieved through extrachromosomal replicating episomes or nuclear genome integration (Limenitakis and Soldati-Favre, 2011). To achieve this, we first successfully introduced transgenic B. divergens parasites expressing GFP from a circular plasmid, as illustrated in Figures 1–3. Subsequently, we generated clonal transgenic parasites exhibiting a GFP fluorescence signal, as demonstrated in Figure 4. These parasites had the original 6-cys-e gene (Bdiv_004560c) locus replaced by both the GFP reporter and hdhfr-WR99210 resistance cassettes, driven by an external ef-tgtp promoter. This marks the first gene knockout in this species. Similar to observations in B. bovis (Alzan et al., 2017), the knockout of the B. divergens 6-cys-e gene displayed the same growth phenotype as the wild-type control, confirming the suitability of the locus for hosting transgenic cassettes. While exploring the role of the resulting 6-cys-E protein in sexual stages (Alzan et al., 2019), its necessity for completing the B. divergens life cycle within the I. ricinus tick vector was beyond this study’s scope, but the created lines serve as a valuable tool for such experiments that may lead to innovative transmission-blocking applications for Babesia.

In conclusion, we have established a highly efficient B. divergens-specific transfection protocol using plasmid delivery into uRBCs before infection and a reliable hdhfr-WR99210 drug selection system. We validated the bidirectional and symmetrical activity of the ef-tgtp promoter for the regulation of external gene expression. Additionally, we introduced B. divergens fluorescent reporter lineages through two distinct methods: extrachromosomal replicating episomes and nuclear genome targeting. Last but not least, we successfully generated a B. divergens 6-cys-e gene knockout line, confirming its non-essential role in blood stage replication. This transfection system has significant potential for advancing functional genomic tools in B. divergens, facilitating a deeper exploration of the crucial processes that govern parasitism within vertebrate host cells and transmission by tick vectors.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

EC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. SB: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. DR: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. VL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. MA: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. DS: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MJ: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was primarily supported by the grant Czech Science Foundation (GA CR) project No. 21-11299S. Additional funding was provided from the CAS/JSPS Mobility Plus Project No. JSPS-21-08; the NRCPDOUAVM Joint Research Grants of NRCPD, Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, project No. 2021-kyodo-18, 2022-kyodo-19; and the ERDF/ESF Centre for Research of Pathogenicity and Virulence of Parasites (No.CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000759). VL was supported by the MEMOVA project, EU Operational Programme Research, Development and Education No. CZ.02.2.69/0.0/0.0/18_053/0016982. PS was additionally supported by an internal grant from the University of South Bohemia GAJU No. 075/2023/P.

We would like to thank the members and head, Jan Perner, Ph.D., of the Laboratory of Molecular Biology of Ticks, Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre CAS, for sharing the laboratory facilities. Our thanks also go to Alexey Bondar, Ph.D., from the Laboratory of Microscopy and Histology, Institute of Entomology, Biology Centre CAS, for his assistance with fluorescence microscopy. Furthermore, we sincerely appreciate Dr. Carlos Suarez from the Animal Disease Research Unit, Washington State University, US, for notifying us about the misannotated gene Bdiv_030590 and subsequent discussion about the correct arrangement of the ef1-α and ef-tgtp genomic loci. We express our gratitude also to Mrs. Lubica Makusova for her technical support on this project.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1278041/full#supplementary-material

Alzan, H. F., Cooke, B. M., Suarez, C. E. (2019). Transgenic Babesia bovis lacking 6-Cys sexual-stage genes as the foundation for non-transmissible live vaccines against bovine babesiosis. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 10 (3), 722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.01.006

Alzan, H. F., Silva, M. G., Davis, W. C., Herndon, D. R., Schneider, D. A., Suarez, C. E. (2017). Geno- and phenotypic characteristics of a transfected Babesia bovis 6-Cys-E knockout clonal line. Parasit Vectors 10 (1), 214. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2143-3

Amos, B., Aurrecoechea, C., Barba, M., Barreto, A., Basenko, E. Y., Bażant, W., et al. (2022). VEuPathDB: the eukaryotic pathogen, vector and host bioinformatics resource center. Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (D1), D898–D911. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab929

Asada, M., Goto, Y., Yahata, K., Yokoyama, N., Kawai, S., Inoue, N., et al. (2012a). Gliding motility of Babesia bovis merozoites visualized by time-lapse video microscopy. PloS One 7 (4), e35227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035227

Asada, M., Tanaka, M., Goto, Y., Yokoyama, N., Inoue, N., Kawazu, S. (2012b). Stable expression of green fluorescent protein and targeted disruption of thioredoxin peroxidase-1 gene in Babesia bovis with the WR99210/dhfr selection system. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 181 (2), 162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.11.001

Asada, M., Yahata, K., Hakimi, H., Yokoyama, N., Igarashi, I., Kaneko, O., et al. (2015). Transfection of Babesia bovis by Double Selection with WR99210 and Blasticidin-S and Its Application for Functional Analysis of Thioredoxin Peroxidase-1. PloS One 10 (5), e0125993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125993

Cuesta, I., González, L. M., Estrada, K., Grande, R., Zaballos, A., Lobo, C. A., et al. (2014). High-quality draft genome sequence of babesia divergens, the etiological agent of cattle and human babesiosis. Genome Announc 2 (6), e01194-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01194-14

De Goeyse, I., Jansen, F., Madder, M., Hayashida, K., Berkvens, D., Dobbelaere, D., et al. (2015). Transfection of live, tick derived sporozoites of the protozoan Apicomplexan parasite Theileria parva. Vet. Parasitol. 208 (3-4), 238–241. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.01.013

Deitsch, K., Driskill, C., Wellems, T. (2001). Transformation of malaria parasites by the spontaneous uptake and expression of DNA from human erythrocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 (3), 850–853. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.3.850

Elsworth, B., Keroack, C., Rezvani, Y., Paul, A., Barazorda, K., Tennessen, J., et al. (2023). Babesia divergens egress from host cells is orchestrated by essential and druggable kinases and proteases. Res. Sq, rs.3.rs-2553721. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2553721/v1

Gaffar, F. R., Wilschut, K., Franssen, F. F., de Vries, E. (2004). An amino acid substitution in the Babesia bovis dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene is correlated to cross-resistance against pyrimethamine and WR99210. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 133 (2), 209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.08.013

González, L. M., Estrada, K., Grande, R., Jiménez-Jacinto, V., Vega-Alvarado, L., Sevilla, E., et al. (2019). Comparative and functional genomics of the protozoan parasite Babesia divergens highlighting the invasion and egress processes. PloS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13 (8), e0007680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007680

Hakimi, H., Asada, M., Ishizaki, T., Kawazu, S. (2021a). Isolation of viable Babesia bovis merozoites to study parasite invasion. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 16959. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96365-w

Hakimi, H., Asada, M., Kawazu, S. I. (2021b). Recent advances in molecular genetic tools for babesia. Vet. Sci. 8 (10), 222. doi: 10.3390/vetsci8100222

Hakimi, H., Yamagishi, J., Kegawa, Y., Kaneko, O., Kawazu, S., Asada, M. (2016). Establishment of transient and stable transfection systems for Babesia ovata. Parasit Vectors 9, 171. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1439-z

Hasenkamp, S., Russell, K. T., Horrocks, P. (2012). Comparison of the absolute and relative efficiencies of electroporation-based transfection protocols for Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 11, 210. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-210

Hildebrandt, A., Zintl, A., Montero, E., Hunfeld, K. P., Gray, J. (2021). Human babesiosis in europe. Pathogens 10 (9), 1165. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091165

Hussein, H. E., Bastos, R. G., Schneider, D. A., Johnson, W. C., Adham, F. K., Davis, W. C., et al. (2017). The Babesia bovis hap2 gene is not required for blood stage replication, but expressed upon in vitro sexual stage induction. PloS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11 (10), e0005965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005965

Jaijyan, D. K., Govindasamy, K., Singh, J., Bhattacharya, S., Singh, A. P. (2020). Establishment of a stable transfection method in Babesia microti and identification of a novel bidirectional promoter of Babesia microti. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 15614. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72489-3

Jalovecka, M., Bonsergent, C., Hajdusek, O., Kopacek, P., Malandrin, L. (2016). Stimulation and quantification of Babesia divergens gametocytogenesis. Parasit Vectors 9 (1), 439. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1731-y

Jalovecka, M., Hartmann, D., Miyamoto, Y., Eckmann, L., Hajdusek, O., O'Donoghue, A. J., et al. (2018). Validation of Babesia proteasome as a drug target. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 8 (3), 394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.08.001

Jalovecka, M., Sojka, D., Ascencio, M., Schnittger, L. (2019). Babesia life cycle - when phylogeny meets biology. Trends Parasitol. 35 (5), 356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.01.007

Limenitakis, J., Soldati-Favre, D. (2011). Functional genetics in Apicomplexa: potentials and limits. FEBS Lett. 585 (11), 1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.002

Liu, M., Adjou Moumouni, P. F., Asada, M., Hakimi, H., Masatani, T., Vudriko, P., et al. (2018a). Establishment of a stable transfection system for genetic manipulation of Babesia gibsoni. Parasit Vectors 11 (1), 260. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2853-1

Liu, M., Adjou Moumouni, P. F., Cao, S., Asada, M., Wang, G., Gao, Y., et al. (2018b). Identification and characterization of interchangeable cross-species functional promoters between Babesia gibsoni and Babesia bovis. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 9 (2), 330–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.11.008

Lobo, C. A. (2005). Babesia divergens and Plasmodium falciparum use common receptors, glycophorins A and B, to invade the human red blood cell. Infect. Immun. 73 (1), 649–651. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.649-651.2005

Malandrin, L., L'Hostis, M., Chauvin, A. (2004). Isolation of Babesia divergens from carrier cattle blood using in vitro culture. Vet. Res. 35 (1), 131–139. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2003047

Rezvani, Y., Keroack, C. D., Elsworth, B., Arriojas, A., Gubbels, M. J., Duraisingh, M. T., et al. (2022). Comparative single-cell transcriptional atlases of Babesia species reveal conserved and species-specific expression profiles. PloS Biol. 20 (9), e3001816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001816

Rosa, C., Asada, M., Hakimi, H., Domingos, A., Pimentel, M., Antunes, S. (2019). Transient transfection of Babesia ovis using heterologous promoters. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 10 (6), 101279. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.101279

Silva, M. G., Knowles, D. P., Suarez, C. E. (2016). Identification of interchangeable cross-species function of elongation factor-1 alpha promoters in Babesia bigemina and Babesia bovis. Parasit Vectors 9 (1), 576. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1859-9

Skinner-Adams, T. S., Lawrie, P. M., Hawthorne, P. L., Gardiner, D. L., Trenholme, K. R. (2003). Comparison of Plasmodium falciparum transfection methods. Malar J. 2, 19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-2-19

Suarez, C. E., Bishop, R. P., Alzan, H. F., Poole, W. A., Cooke, B. M. (2017). Advances in the application of genetic manipulation methods to apicomplexan parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. 47 (12), 701–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2017.08.002

Suarez, C. E., Lacy, P., Laughery, J., Gonzalez, M. G., McElwain, T. (2007). Optimization of Babesia bovis transfection methods. Parassitologia 49 Suppl 1, 67–70.

Suarez, C. E., McElwain, T. F. (2008). Transient transfection of purified Babesia bovis merozoites. Exp. Parasitol. 118 (4), 498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.10.013

Suarez, C. E., McElwain, T. F. (2009). Stable expression of a GFP-BSD fusion protein in Babesia bovis merozoites. Int. J. Parasitol. 39 (3), 289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.08.006

Suarez, C. E., McElwain, T. F. (2010). Transfection systems for Babesia bovis: a review of methods for the transient and stable expression of exogenous genes. Vet. Parasitol. 167 (2-4), 205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.022

Suarez, C. E., Norimine, J., Lacy, P., McElwain, T. F. (2006). Characterization and gene expression of Babesia bovis elongation factor-1alpha. Int. J. Parasitol. 36 (8), 965–973. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.02.022

Vieira, T. B., Astro, T. P., de Moraes Barros, R. R. (2021). Genetic manipulation of non-falciparum human malaria parasites. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 680460. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.680460

Vinayak, S., Pawlowic, M. C., Sateriale, A., Brooks, C. F., Studstill, C. J., Bar-Peled, Y., et al. (2015). Genetic modification of the diarrhoeal pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. Nature 523 (7561), 477–480. doi: 10.1038/nature14651

Wang, S., Li, D., Chen, F., Jiang, W., Luo, W., Zhu, G., et al. (2022). Establishment of a transient and stable transfection system for babesia duncani using a homologous recombination strategy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 844498. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.844498

Keywords: Babesia divergens, transfection system, erythrocytes pre-loading, GFP-expression, bidirectional promoter, gene targeting, 6-cys-e gene knockout

Citation: Cubillos EFG, Snebergerova P, Borsodi S, Reichensdorferova D, Levytska V, Asada M, Sojka D and Jalovecka M (2023) Establishment of a stable transfection and gene targeting system in Babesia divergens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13:1278041. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1278041

Received: 15 August 2023; Accepted: 29 November 2023;

Published: 13 December 2023.

Edited by:

Ladislav Simo, Institut National de recherche pour l’agriculture, l’alimentation et l’environnement (INRAE), FranceReviewed by:

David R. Allred, University of Florida, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Cubillos, Snebergerova, Borsodi, Reichensdorferova, Levytska, Asada, Sojka and Jalovecka. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marie Jalovecka, amFsb3ZlY2thQHByZi5qY3UuY3o=; Daniel Sojka, c29qa2FAcGFydS5jYXMuY3o=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.