- 1The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, School of Public Health, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China

- 2Department of Medical Microbiology, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China

- 3School of Public Health, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China

- 4Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Preventive Medicine, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China

Background: Candida albicans is a commensal yeast that may cause life-threatening infections. Studies have shown that the cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 7 gene (QCR7) of C. albicans encodes a protein that forms a component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain complex III, making it an important target for studying the virulence of this yeast. However, to the best of our knowledge, the functions of QCR7 have not yet been characterized.

Methods: A QCR7 knockout strain was constructed using SN152, and BALb/c mice were used as model animals to determine the role of QCR7 in the virulence of C. albicans. Subsequently, the effects of QCR7 on mitochondrial functions and use of carbon sources were investigated. Next, its mutant biofilm formation and hyphal growth maintenance were compared with those of the wild type. Furthermore, the transcriptome of the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant was compared with that of the WT strain to explore pathogenic mechanisms.

Results: Defective QCR7 reduced recruitment of inflammatory cells and attenuated the virulence of C. albicans infection in vivo. Furthermore, the mutant influenced the use of multiple alternative carbon sources that exist in several host niches (GlcNAc, lactic acid, and amino acid, etc.). Moreover, it led to mitochondrial dysfunction. Furthermore, the QCR7 knockout strain showed defects in biofilm formation or the maintenance of filamentous growth. The overexpression of cell-surface-associated genes (HWP1, YWP1, XOG1, and SAP6) can restore defective virulence phenotypes and the carbon-source utilization of qcr7Δ/Δ.

Conclusion: This study provides new insights into the mitochondria-based metabolism of C. albicans, accounting for its virulence and the use of variable carbon sources that promote C. albicans to colonize host niches.

Introduction

Candida albicans is one of the most important opportunistic pathogens worldwide. Its effects range from superficial to invasive infections and even death. The mortality rate of C. albicans during nosocomial infection can be as high as 50% (Gow and Yadav, 2017). The use of various carbon sources is a key factor that influences the virulence of C. albicans (Williams and Lorenz, 2020). Although glucose is the preferred carbon source of C. albicans, this organism inhabits host environments with limited glucose but rich alternative-carbon sources. Hence, several cellular complexes have evolved in C. albicans to use multiple sources of carbon, contributing to its growth and virulence (Brown et al., 2007).

The mitochondrial electron transport chain (METC) is the primary site of carbon metabolism and is involved in the energy supply during respiration. The link between respiratory activity and virulence has been well demonstrated in the pathogen’s response to morphological transformation and stimuli by obtaining nutrients from the host and remodeling the cell wall through carbon source assimilation (Pradhan et al., 2018; Williams and Lorenz, 2020), and high ATP levels under respiratory activity have also been shown to be essential for Candida albicans to regulate hyphal growth through the Ras1/cAMP/PKA signaling pathway (Grahl et al., 2015). The respiratory chain has been proposed as an attractive target for the development of antifungal agents to alleviate fungal infections and prevent the evolution of drug resistance. There is a practical need for a deeper understanding of the mitochondrial biology of invasive fungal pathogens such as Candida albicans. METC comprises five complexes: Complexes I- V, and a cyanide-insensitive alternative oxidase (AOX); most studies only focused on the function of complexes I and V (Huang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). However, limited studies have explored complex III. We selected this complex because of its importance in electron transport. Complex III, also known as cytochrome bc1 complex, is a component of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Tzagoloff, 1995). In complex III, electrons pass from one cytochrome to the other cytochrome through an iron–sulfur protein. These electrons eventually reach cytochrome C. This process results in the transfer of protons from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space, which then generates electrochemical potential in the inner mitochondrial membrane through the free energy gained from the electron transfer. This electrochemical potential is used by mitochondrial ATP synthase to synthesize ATP (Nolfi-Donegan et al., 2020). The complex III consists of ten subunits in S. cerevisiae, including three catalytic subunits, Cob (Cytochrome b), Rip1 (iron–sulfur protein), Cyt1 (Cytochrome c1), and seven additional subunits: Cor1, Qcr2, Qcr6, Qcr7, Qcr8, Qcr9, and Qcr10 (Brandt et al., 1994; Hunte et al., 2003). A previous study showed that complex III inhibition impaired the virulence and drug resistance of C. albicans in mice, and that the inhibition of cytochrome B significantly restricted the use of carbon sources, while the deletion of RIP1 was found to have an effect on a range of virulence phenotypes of C. albicans (Vincent et al., 2016). In this study, we knocked out eight viable subunits, experimented with each mutant strain on the utilization of multiple carbon sources and found that the RIP1/COR1/QCR2/QCR7/QCR8 knockout strains all differed to varying degrees from the wild type in carbon-source utilization. However, in our study of the effect of complex III on the virulence factor of C. albicans was found that Qcr7 had a greater impact on biofilm formation and the maintenance hyphal growth on solid media than the other subunits. In addition, Qcr7 is a protein that is directly and earliest interacts with fully hemimethylated cytochrome B in the assembly sites of the S. cerevisiae mitochondrial complex III and is involved in the conduction of protons from the matrix to the cytochrome b redox center (Lorusso et al., 1989). Although C. albicans is a significant pathogen, the function of QCR7 in the virulence of C. albicans remains unknown.

This study, therefore, sought to explore the effects of Qcr7 on the virulence of C. albicans, including its possible mechanism(s). We demonstrate the crucial involvement of QCR7 in systemic infections due to C. albicans, in addition to its essential functions in the use of amino acids, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), and nonfermentable carbon sources. We used a qcr7Δ/Δ mutant that showed evident mitochondrial dysfunction. The qcr7Δ/Δ mutant exhibited significantly impaired biofilm formation and hyphal development. Furthermore, RNA-sequencing analysis identified several downregulated genes involved in carbohydrate transport and cell-surface functions, and that restore the corresponding pathogenic phenotype in case of the overexpression of the cell-surface-associated genes (HWP1, YWP1, XOG1, SAP6) in the qcr7Δ/Δ background. These data suggest that Qcr7 regulates the cell-surface integrity to affect the use of carbon sources and pathogenic phenotypes, promoting host interaction.

Materials and methods

Strains and growth conditions

Table S1 presents information on the strains, and Table S2 shows the primers used in this study. For general growth and propagation, C. albicans strains were cultured at 30°C in yeast-extract–peptone–dextrose (YPD) medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, and 2% agar). First, C. albicans mutants and complement strains were created following previous studies (Noble and Johnson, 2005; Nobile et al., 2009; Noble et al., 2010), and the overexpression strain was examined as previously described (Gerami-Nejad et al., 2013). In brief, the gene-knockout strategy of the present study involved gene knockout using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based homologous recombination. This strategy uses C. albicans SN152 with defective histidine (HIS), leucine (LEU), and arginine (ARG) genes as the parent strain and HIS1 (Cd. HIS1) from C. dubliniensis, LEU2 (C. maltose LEU2, Cm.LEU2) from C. maltose, and ARG4 (C. dubliniensis ARG4, Cd. ARG4) from C. dubliniensis as the target genes to replace nutritional-marker genes for selection. This method typically knocks out the target genes one after the other, and two screening markers can be arbitrarily selected to knock out the target gene. In this study, the LEU2 cassette from plasmid pSN40 was amplified, and the strain SN152 was transformed with the fusion PCR products of LEU2 flanked by QCR7 5′ and 3′ fragments. The plasmid pSN52 was used as a PCR template to amplify the HIS1 cassette, and the second QCR7 allele was deleted using fusion PCR products of the HIS1 marker flanked by QCR7 5′- and 3′-fragments (Figure S1). A copy of QCR7 was returned to the QCR7 locus to construct the gene-reconstituted strain. The entire QCR7 open-reading frame, including 743 bp of the 5′end, was amplified. Next, the entire QCR7 open-reading frame with upstream and the ARG4 cassette from plasmid pSN69 and downstream flanks (approximately 400 bp) were amplified using fusion PCR assays. The PCR products were transformed into the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant to construct the qcr7/QCR7 gene-reconstituted strain (Noble and Johnson, 2005) (Figure S2). The qcr7Δ/Δ mutant and reconstituted strain (qcr7/QCR7) were confirmed through PCR with the primer pairs shown in Supplementary Figure S3. However, the gene-overexpression strategy of the present study involved the amplification of the coding region of the corresponding genes by PCR and downstream cloning of the S. cerevisiae ADH1 promoter to integrate inserts into a large intergenic region, NEUT5L which facilitates the integration and expression of ectopic genes (Gerami-Nejad et al., 2013) (Figure S4).

Susceptibility assays

To evaluate the growth of C. albicans strains cultured with different carbon sources, strains were cultured overnight in YPD. Strains diluted to varying concentrations (5 μl of 107 cells/ml to 103 cells/ml) were spotted on yeast-extract–peptone solid medium (YEP; 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone). Next, washing and serial dilution with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were performed. This medium contained 2% glucose, 2% glycerol, 2% citrate, 2% acetate, 2% maltose, 2% ethanol, 2% lactate, and 50 mM GlcNAc. Subsequently, the sensitivity of C. albicans to cell-wall stress was assessed by spotting on YPD containing cell-wall stressors, such as Congo red (CR, 300 µg/ml), calcofluor white (CFW, 50 µg/ml), 0.04%SDS and caspofungin (0.25 µg/ml).

Biofilm formation assay

We evaluated the biofilm-formation mass of C. albicans using crystal-violet staining as described previously (Silva et al., 2009; Abbes et al., 2017; Neji et al., 2017). First, strains were cultured overnight in liquid YPD at 30°C and 220 rpm and then harvested via centrifugation at 3,000 rpm after washing twice with sterile PBS. Subsequently, the mixture was resuspended in Spider liquid medium. Next, supplementation was performed using appropriate carbon sources and 2-mililiter C. albicans-strain suspensions (1 ml containing 5 × 106 cells) and the suspensions were incubated overnight in 12-well flat-bottomed plates containing fetal bovine serum (FBS) before the final incubation for 90 min at 37°C. Next, the nonattached cells were removed from the wells by washing once with 2 ml PBS, after which 2 ml of fresh corresponding induction medium was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Following the removal of medium, each well was washed once with PBS and treated with equivalent concentrations of methanol for 30 min. Next, equivalent concentrations of 1% crystal violet (Solarbio, China) were added to the wells for drying, and staining was performed for 1 h. Washing was performed under a gentle water flow until a colorless mixture was obtained, followed by incubation with equivalent amounts of acetic acid for 30 min to decolorize the mixture. Measurements were performed at 620 nm using a microplate reader.

Filamentous growth assays

The wild-type (WT) strain was cultured overnight in YPD, followed by washing and dilution with PBS to achieve a suspension with OD600 = 0.1Abs. Next, the mixture was aliquoted in Spider liquid medium using appropriate carbon sources such as fermentable sugars (e.g., 2% glucose, 2% maltose, and 2% sucrose) or alternative carbon sources (e.g., 2% mannitol and 50mM GlcNAc) for hyphal induction at 37°C (Huang et al., 2017). The cells were harvested, and hyphal morphologies were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) at indicated time points. Subsequently, each cell type (1 × 105 cells in 5 µl of PBS) was spotted on Spider solid medium with appropriate carbon sources. The cultures were then incubated at 37°C, and photographs were taken after 7 days.

Immunofluorescence analysis of mouse kidney tissues

Kidney tissues were paraffin-embedded sectioned, Each slide was dewaxed by xylene, ethanol treatment, and antigen repair with citric acid as the repair solution, after which it was closed with a serum of the same source as the secondary antibody (usually 10% goat serum was used) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C (Henkels et al., 2016; Sasaki et al., 2021). Then treated slides with anti-Ly-6G (Servicebio; GB11229), anti-F4/80 antibodies (28463-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) overnight at 4°C. All slides were washed with PBS before incubation with FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody and CY3-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (Pinuofei Biotechnology Co, China). After PBS rinsing, the slides were exposed to DAPI for 5 min to stain cell nuclei. Then, the slides were analyzed under a fluorescence microscope.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

To determine the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), the MMP assay kit with JC-1 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used. MMP decreases can be easily detected through JC-1’s transition from red to green fluorescence (She et al., 2015). Cells were collected when strains subcultured in fresh medium reached the log phase of growth and incubated with equal volumes of JC-1 dyeing solution at 37°C for 15 min in the dark. Cells were washed twice and resuspended in JC-1 dyeing solution. Next, we explored the emission spectra at 488 nm and excitation spectra at 595 nm using the Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter); the red/green mean fluorescence intensities (FIs) were recorded for each sample.

Measurement of intracellular-reactive-oxygen-species levels

All strains were cultured overnight in YPD at 30°C and 220 rpm, followed by washing and resuspension in PBS. Subsequently, 2 × 106 cells were stained using fluorescent dichlorodihydro fluorescein diacetate dye (20 µg/ml) (Guo et al., 2014). Next, these cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 min in the dark. Subsequently, FIs were recorded using a multifunctional enzyme-mark instrument (SpectraMax Paradigm) with an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and emission wavelength of 530 nm. Finally, the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were determined by evaluating each strain thrice.

Measurement of intracellular ATP contents

All strains were cultured overnight in YPD at 30°C. Cells were then subcultured in fresh medium until the log phase of growth was reached. Next, 2 × 106 cells of each strain were mixed completely with equal volumes of the BacTiter-Glo reagent (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) (Lin et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021), followed by incubation at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. Finally, luminescent signals were detected using the full-wavelength multifunctional enzyme-mark instrument (SpectraMax Paradigm).

Sap-activity-testing assays

Secreted aspartyl protease (Sap) activity assays were performed using 0.17% yeast-nitrogen-base (YNB) medium (without aa or AS) + 0.1% BSA, containing 2% glucose as the carbon source and bovine serum albumin (BSA])as the sole nitrogen source (Crandall and Edwards, 1987). Water was used to suspend 1 × 105 cells, after which they were spotted on YNB–BSA agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 5 days. The size of the white halo rings indicated the activity level. This experiment was repeated thrice.

RNA isolation, cDNA library preparation, and sequencing

Through transcriptome sequencing, we evaluated the global transcriptional response of C. albicans in RPMI 1640. All strains were cultured overnight in YPD at 30°C and subcultured in fresh YPD (buffered) at 30°C. Subsequently, C. albicans cells at the log phase of growth were resuspended in RPMI 1640, followed by incubation at 37°C for 4h according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Next, RNA extraction was performed using TRIzol (TIANGEN). In brief, 5 × 106 cells were isolated and added to a precooled mortar. The cells were then grounded to powder with liquid nitrogen, after which the sample was stirred in 1 ml TRIzol for 10 min. Subsequently, chloroform (200 µl) was added to separate the aqueous RNA-containing solution from the intermediate and organic layers, which was followed by RNA precipitation using isopropyl alcohol (equal volume) and the addition of 1 ml ethanol (75%) to each RNA pellet. Finally, the samples were centrifuged (12,000 rpm/5 min/4°C), and the RNA was resuspended in 20 μL nuclease-free water and then stored at −80°C. Furthermore, the RNA samples were assessed using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and NanoPhotometer spectrophotometer (Implen). Triplicate samples used in all assays were used to construct an independent library, and the sequencing and analysis were performed. The libraries for sequencing were constructed using the NEB Next Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB). The poly (A)-tailed mRNA was enriched using the NEB Next Poly (A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module kit. The mRNA was fragmented into segments of nearly 200 bp. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from the mRNA fragments through reverse transcription using random hexamer primers. Next, second-strand cDNA was synthesized using DNA polymerase I and RNaseH. The end of the cDNA fragment was subjected to an end repair that included adding a single “A” base, followed by adapter ligation. PCR was used to purify and enrich the products to construct a DNA library. The final libraries were quantified using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. After performing validation through quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, libraries were subjected to paired-end sequencing with a reading length of 150 bp using Illumina Novaseq 6000 (Illumina).

Quantitative real-time PCR

All the strains were cultured overnight in YPD at 30°C and subcultured in fresh YPD (buffered) at 30°C until growth at the log phase. Subsequently, cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640, followed by incubation at 37°C for 4h. The methods for RNA extraction were those described above. Extracted RNA was treated with DNase I (Takara) to remove contaminating DNA, and cDNA was synthesized with a PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was used as template for RT–qPCR using a SYBR Green mix kit (Mei5 Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) on a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System. The 18S rRNA genes were used as endogenous controls as specified. The results were analyzed using the 2-ΔΔCT method. The primers for the genes used in the RT-qPCR are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were biologically replicated thrice. Data were presented as means ± standard errors of the means. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Significant differences were calculated using two-way analyses of variance and Student’s t-tests.

Results

Qcr7 is a new essential subunit of bc1 complex in maintaining Candida albicans virulence phenotype

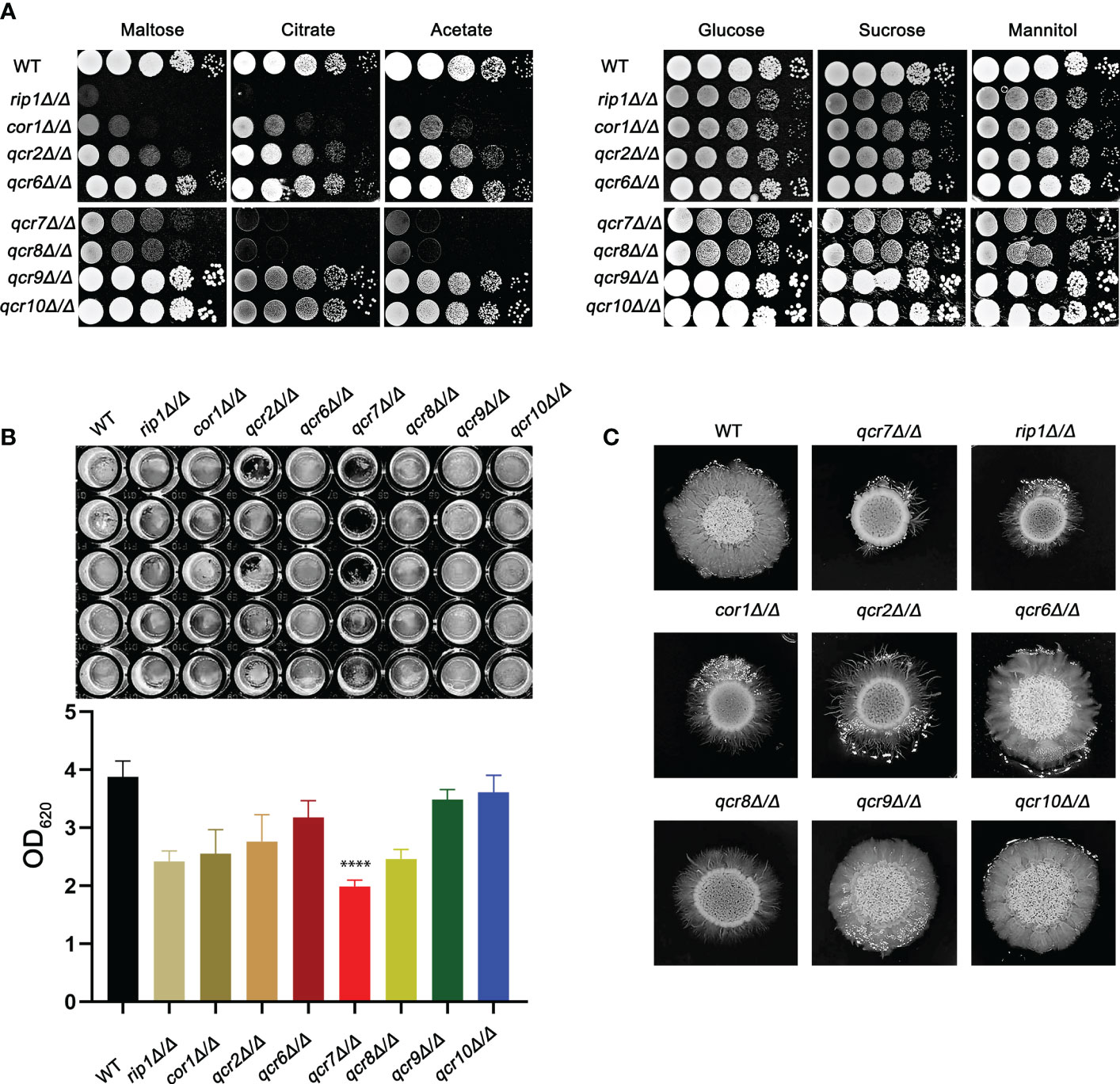

Previous studies identified that disabling Complex III can prevent fungal adaptation to nutrient deprivation, sensitize C. albicans to attack by macrophages, and curtail virulence in mice (Vincent et al., 2016). However, in these studies, the catalytic subunit RIP1 was chosen as a representative and used in the remaining experiments. It is unclear whether other subunits are equally important for the functional performance of mitochondrial Complex III (CIII) and the maintenance of C. albicans virulence. In this study, we identified ten genes (COB, RIP1, CYR1, COR1, QCR2, QCR6, QCR7, QCR8, QCR9, and QCR10) encoding the subunit of mitochondrial Complex III using the Candida Genome Database (CGD, http://www.candidagenome.org/). Among them, apart from cobΔ/Δ and cyr1Δ/Δ mutants, which were inviable, we successfully knocked out the other eight subunits and tested the utilization of several carbon sources as energy sources for the pathogens. As shown in Figure 1A, in the right panel, in media with glucose, sucrose, and mannitol as carbon sources, rip1Δ/Δ, cor1Δ/Δ, qcr2Δ/Δ, qcr7Δ/Δ, and qcr8Δ/Δ showed a similar lag phase. However, the above mutant displayed remarkable growth defects compared to that of the WT in media with other host-relevant carbohydrates (e.g., maltose, citrate, acetate) as carbon sources. To examine the effect of Complex III mutants on the major virulence factors associated with C. albicans, the panel of mutants was examined for their biofilm-formation ability, hyphal growth, etc. Consistent with an alteration in carbon assimilation, the corresponding mutants also displayed defects in hyphal growth on solid media and were unable to form the dense matrix of the biofilm (Figures 1B, C). The remaining subunit formed Complex III; these coding gene mutants showed a similar phenotype to the wild-type strain. Surprisingly, we found that the absence of QCR7 had a more evident phenotypic impact on the ability of C. albicans to maintain hyphal growth on solid media and biofilm formation than the other subunit knockout strains. The results indicate that Qcr7 is critical to virulence in C. albicans. Thus, a series of experimental studies were conducted on QCR7, as described below.

Figure 1 Complex III plays an important role in the virulence of Candida albicans. (A) Strains were cultured overnight in YPD, followed by washing and serial dilution with PBS. Different rip1Δ/Δ, cor1Δ/Δ, qcr2Δ/Δ, qcr6Δ/Δ, qcr7Δ/Δ, qcr8Δ/Δ, qcr9Δ/Δ, and qcr10Δ/Δ concentrations (5 μl of 107 cells/ml to 103 cells/ml) were spotted on solid YEP media containing 2% glucose and several alternative carbon sources. Plates were then photographed after incubation at 30°C for 2 days. (B) C albicans suspension of 5 × 106 cells in Spider medium were incubated in 12-well flat-bottom plates at 37°C for 90 min, after which nonattached cells were removed from the wells by washing once with PBS. Fresh corresponding induction medium was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 48h. Next, the well was washed with PBS and stained with crystal violet; after decolorization, measurements were taken using a microplate reader at 620 nm. “****” represents p < 0.0001 for the WT vs. mutant strains. (C) Cells of each type (1 × 105 cells in 5 µl PBS) were spotted on regular indicated filament-inducing agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 7 days before taking photographs.

QCR7 mutants attenuated the virulence of Candida albicans infection in vivo

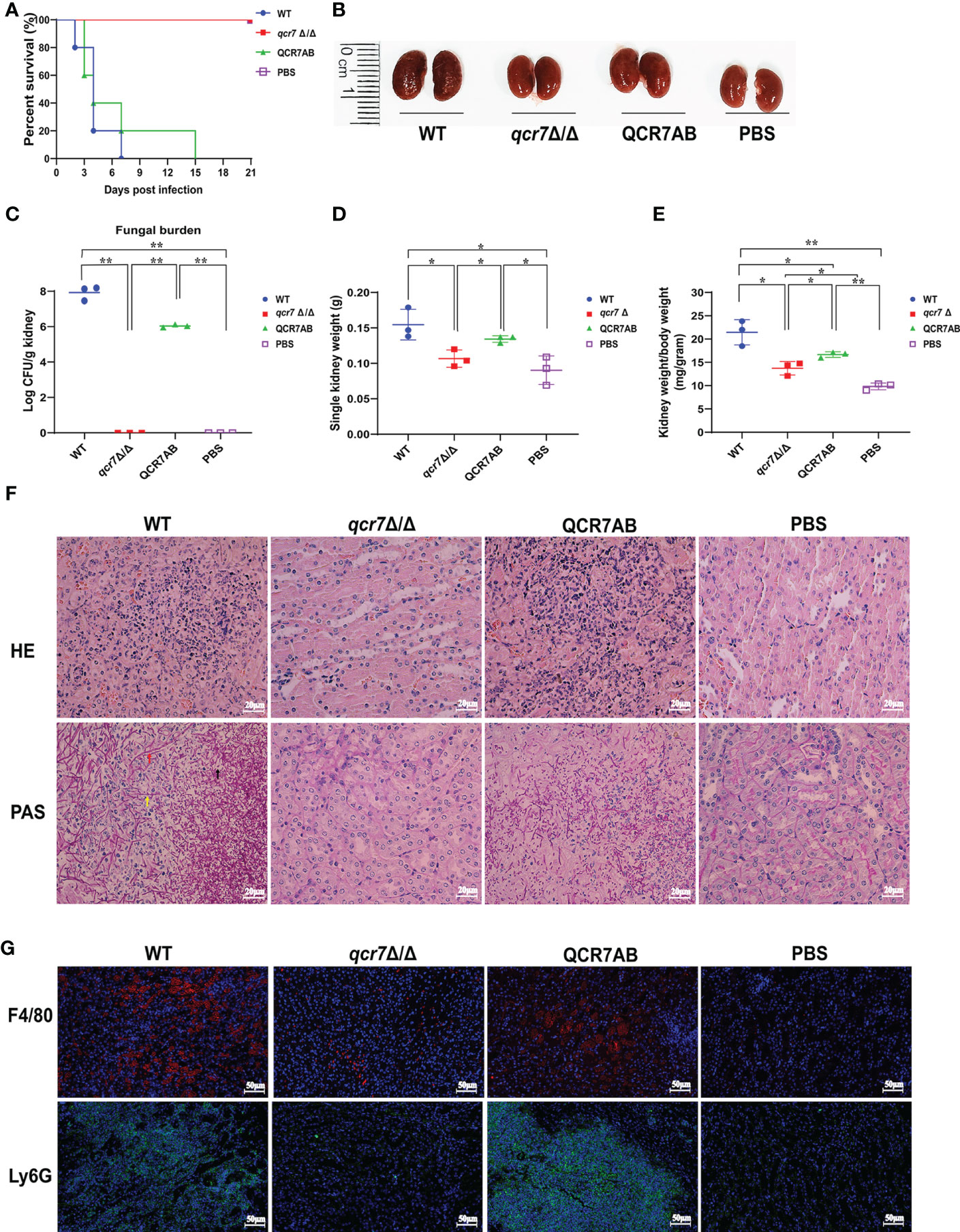

Based on the above findings, it is reasonable to assume that QCR7 mutant could influence the fatal infections of C. albicans. Previous study showed the inhibition of Complex III was effective in attenuating the virulence of C. albicans in mice (Vincent et al., 2016). Therefore, we performed relevant experiments and analyzed in a mouse model of systemic candidiasis to investigate the effect of Qcr7 on C.albicans-infected hosts. The survival rate of the mice injected with the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant was much higher than that of those injected with the WT and QCR7 complement strains (QCR7 AB). Furthermore, no mice died within 3 weeks of infection with the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant (Figure 2A). During pathological characterization, the kidneys, the main target organ, of the infected mice served as the key indicators of host infection (Leunk and Moon, 1979). Regarding the kidney anatomy, the mice injected with the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant had smaller kidneys than those injected with the WT strain (Figure 2B). To quantitatively evaluate the invasive effects of C. albicans on the kidney, we investigated the fungal loads that correlated with the severity of kidney failure. By calculating the total number of colony-forming units (CFU) in the kidneys on day 2, we observed that the fungal burden in the kidneys injected with the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant significantly reduced (Figure 2C). Single kidney weight and kidney weigh/body weigh were also significantly reduce compared to wild type (Figures 2D, E). A histological analysis of the kidney-tissue samples obtained from the mice infected with the WT strain also revealed large areas with inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 2F).

Figure 2 QCR7 mutant attenuates the virulence of C albicans infection in vivo. (A) Mice survival following illness initiation with the injection of 5 × 105 C albicans cells. (B) Comparison of mouse kidneys was conducted by injection with WT, qcr7Δ/Δ, and QCR7AB. Mice were sacrificed 48h after the C albicans infection. (C–E) Fungal burden in the kidneys of mice injected with WT, qcr7Δ/Δ, and QCR7AB (p<0.0001 WT vs mutant). The mice were sacrificed 2 days after an intravenous injection with 5 × 105 CFU C albicans. Kidney weights were calculated as each mouse’s weight per gram of body weight (p=0.0122 WT vs mutant). “*” represents p < 0.05 and “**” represents p < 0.01 for the WT vs. mutant strains. (F) Representative hematoxylin–eosin- or periodic acid-Schiff-base-stained sections of kidney-tissue samples from three experiments. (G) Immunofluorescence image showing the biodistribution of F4/80 (red) and Ly6G (green) in the renal of mice infected with Candida albicans. The nuclei were stained blue by DAPI. Scale bar = 50μm. Hyphae (red arrow), pseudo-hyphae (yellow arrow), and spores (black arrow).

The kidney tissues obtained from the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant-infected mice showed significantly less inflammatory cells. Periodic acid-Schiff-base staining consistently revealed more tissue damage in the kidney, which differed between the WT-strain-infected mice with several C. albicans hyphae (red arrow), pseudo-hyphae(yellow arrow), and spores(black arrow), and the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant-infected mice (Figure 2F). Therefore, these results suggest that the absence of lethal injury in mice by the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant results from defective tissue invasion and colonization ability. To further clarify the spatial and temporal distribution of immune cells infiltrating the kidneys of mice during systemic infection, we observed the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages in the kidney tissue of mice infected with the wild-type, mutant and complement strains for two days. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using Ly6G antibody for neutrophils and F4/80 antibody for macrophages. It can be visually seen that the number of both immune cells recruited in the kidneys of qcr7Δ/Δ infected mice was significantly reduced (p<0.0001), while their immune cells infiltration increased significantly after qcr7 was reconstituted (p<0.0001) (Figures 2G, S5). Once again, it was well demonstrated that qcr7 is important for C. albicans to invade the attack of host immune system.

Qcr7 is a key subunit that maintain the normal function of mitochondrial and carbon-source-usage pattern of Candida albicans

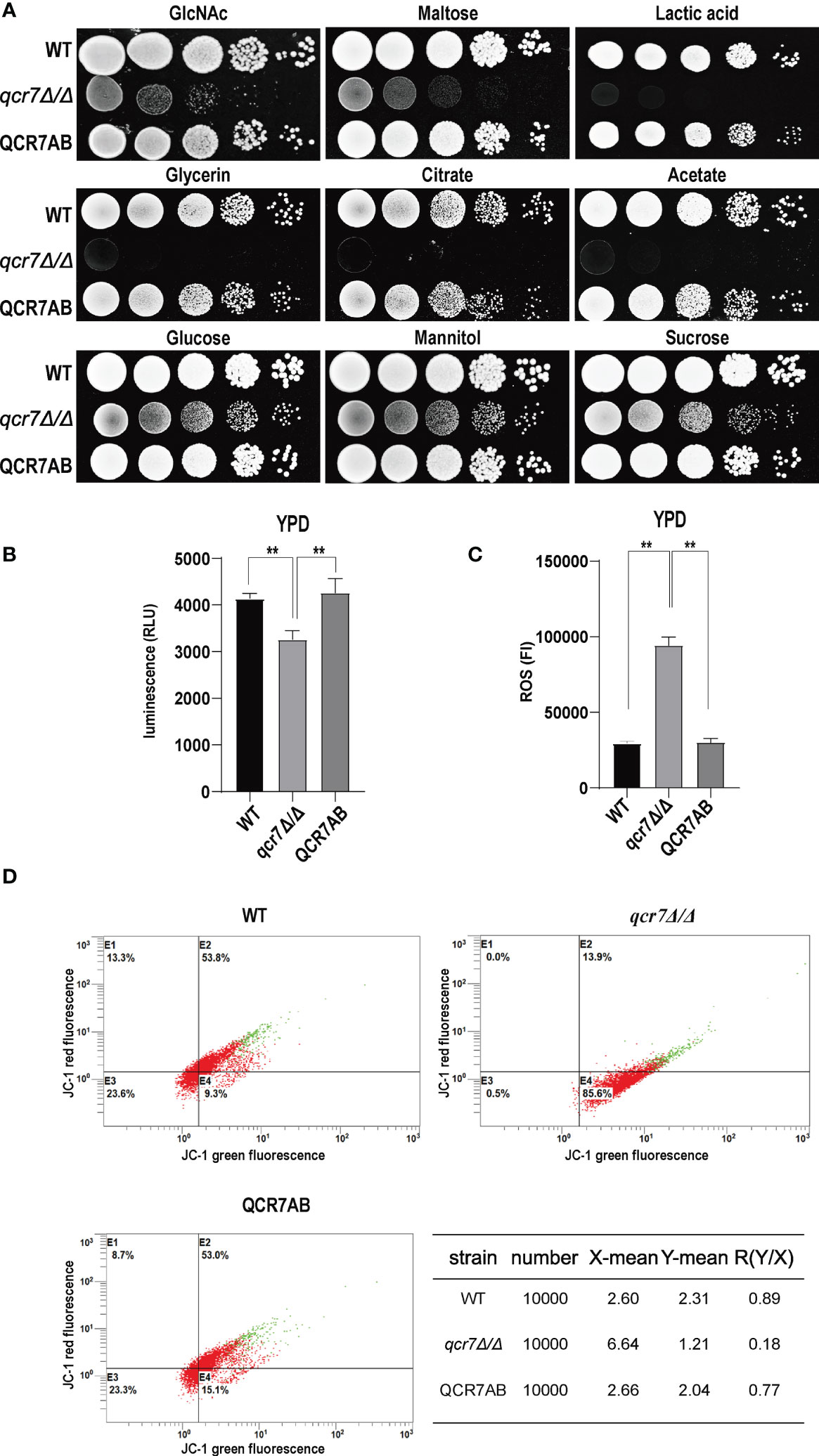

Fungi can use carbon sources to obtain energy for anabolic metabolism through glycolysis and aerobic respiration. The energy generated through the electronic transport chain is the primary source of energy for fungal growth. Therefore, if mitochondrial dysfunction affects aerobic respiration, the glycolytic pathway becomes the main metabolic pathway for energy metabolism. In addition, glycolysis is crucial for carbon assimilation, and this pathway also influences the invasiveness and virulence of C. albicans (Barelle et al., 2006). C. albicans uses multiple carbon sources in vitro, including glucose, GlcNAc, carboxylic acids (e.g., lactate), and amino acids (Williams and Lorenz, 2020). Compared with the WT strain, the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant grew slightly slower in the glucose-, sucrose-, and mannitol-only media. However, the growth of the mutant in the media containing GlcNAc or other non-glucose carbon sources was more significant than that of the WT strain (Figure 3A). The qcr7Δ/Δ mutant did not use amino acids as carbon sources (Figure S6). The results indicate that the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant has a defective respiratory metabolism, which may affect ATP production during carbon metabolism. Furthermore, this implies that qcr7Δ/Δ does not substantially regulate the in vitro growth of C. albicans in the presence of alternative carbon sources.

Figure 3 QCR7 is required for maintaining mitochondrial functions and carbon-source use. (A) Strains were cultured overnight in YPD, followed by washing and serial dilution with PBS. Different WT, qcr7Δ/Δ, and QCR7AB concentrations (5 μl of 107 cells/ml to 103 cells/ml) were spotted on solid YEP media containing 2% glucose and several alternative carbon sources. Plates were then photographed after incubation at 30°C for 2 days. (B) The intracellular ATP content was measured using a microplate reader. “**” represents p < 0.01 for the WT vs. mutant strains. (C) ROS levels were measured using the dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate dye and a multifunctional enzyme-mark instrument. (D) Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was evaluated using the JC-1 assay kit and Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer (Ex/Em of 595/488 nm), and the red/green mean fluorescent intensities were recorded for each sample. The transition of JC-1 dye from red to green fluorescence was used to easily detect the decrease in MMP, after which MMP was determined as the ratio of red to green fluorescence.

Because Qcr7 is a component of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, we also examined the intracellular ATP content, endogenous ROS production, and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) of qcr7Δ/Δ mutants during logarithmic growth phase to determine their effect on mitochondrial functions. As expected, a significant decrease in intracellular ATP contents was observed in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant among logarithmic growth phase (Figure 3B). Moreover, after evaluating the MMP using the JC-1 assay kit, we observed that the MMP of the mutant was significantly decreased compared with that of the WT strain (Figure 3D). In addition, the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant produced a higher level of ROS (Figure 3C). These data suggest the important function of Qcr7 in maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis.

QCR7 deletion resulted in impaired biofilm formation and hyphal-growth maintenance after the exposure of Candida albicans to various carbon sources

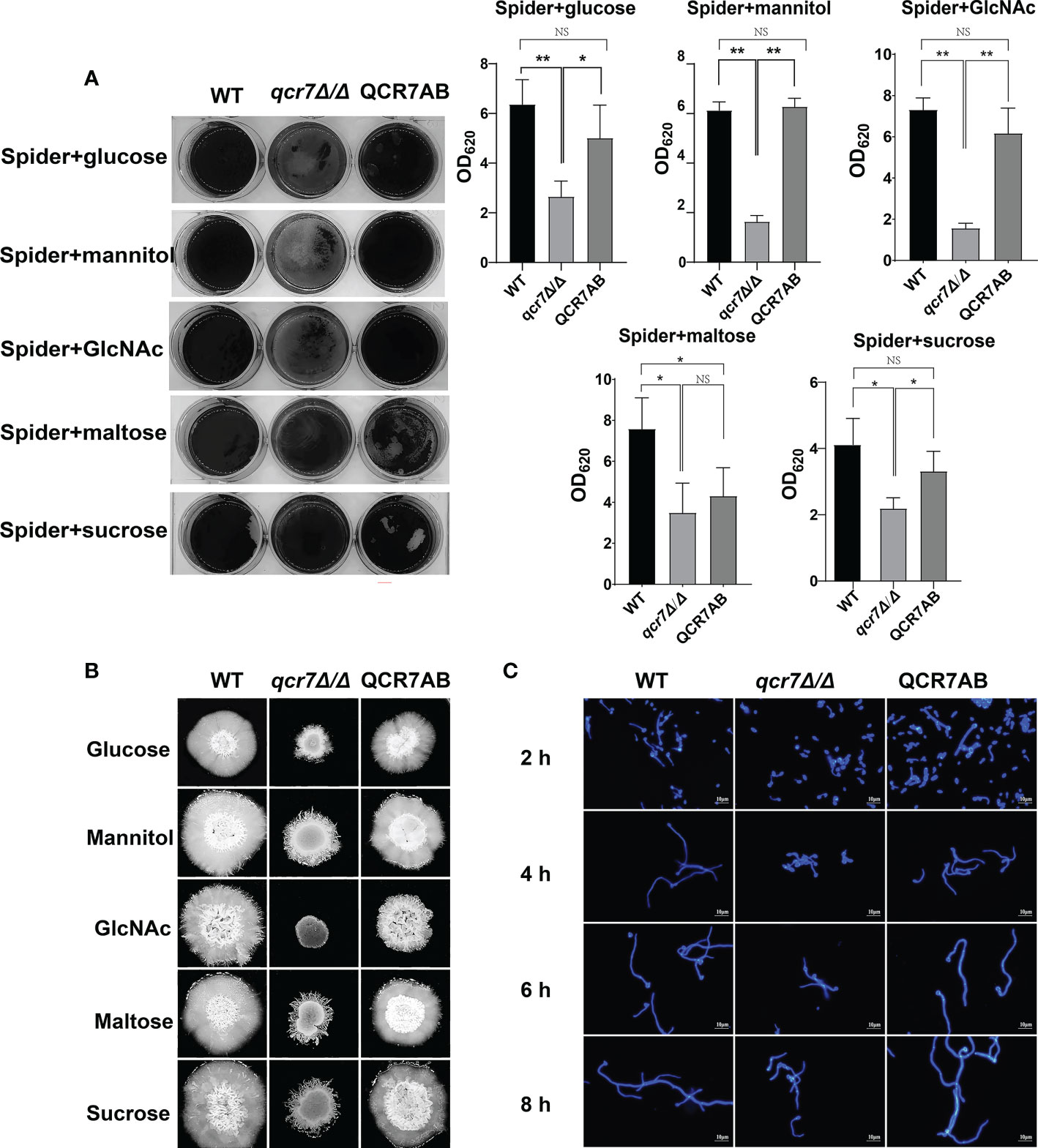

Biofilms are defined as an association of microorganisms attached to a biotic or abiotic surface, the formation of which is considered a potential cause of antifungal drug failure and is associated with 65%-80% of microbial infections (Jamal et al., 2018). C.albicans biofilms, which often colonizes implanted medical devices and mucosal surfaces, and aggressive systemic infections of tissues and organs caused by dissemination into the bloodstream as a reservoir of pathogenic cells (Nobile and Johnson, 2015), which leads to inflammation and lethality. Thus, to understand the importance of QCR7 in biofilm formation, we performed an additional biofilm analysis under multiple conditions. Defective biofilm formation was evident in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant when incubated in the Spider medium supplemented with glucose, mannitol, GlcNAc, maltose, and sucrose (Figure 4A). Therefore, these results indicate the importance of QCR7 in appropriate carbon-induced biofilm formation by C. albicans.

Figure 4 Deletion of QCR7 affects biofilm formation and hyphal growth maintenance in Candida albicans under various carbon sources, with the most significant effect under GlcNAc conditions. (A) C albicans suspensions of 5 × 106 cells in Spider medium supplemented with mannitol, glucose, sucrose, maltose, and GlcNAc as sole carbon sources were incubated in 12-well flat-bottom plates at 37°C for 90 min, after which nonattached cells were removed from the wells by washing once with PBS. Fresh corresponding induction medium was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 48h. Next, each well was washed with PBS and stained with crystal violet; after decolorization, measurements were taken using a microplate reader at 620 nm. “*” represents p < 0.05 and “**” represents p < 0.01 for the WT vs. mutant strains. (B) Each cell type (1 × 105 cells in 5 µl of PBS) was spotted on the Spider medium, containing 2% glucose, 2% mannitol, 2% maltose, 2% sucrose, and 2% GlcNAc at 37°C. Photographs were then taken after 7 days of growth. (C) The wild type, qcr7Δ/Δ, and QCR7AB were cultured overnight in liquid YPD at 30°C, followed by washing and dilution to OD600 nm = 0.1 of PBS, after which resuspension in Spider medium supplemented with GlcNAc as the sole carbon source was conducted, and incubation continued at 37°C. The hyphal morphology was finally visualized through fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan). Scale bars are 10 μm. “NS” represents not significant.

C. albicans can form hyphal cells both in planktonic cultures and during the maturation step of biofilm formation (Sudbery, 2011). In this study, we assessed the influence of QCR7 on the hyphal induction of C. albicans cultured in media containing various carbon sources. As expected, the results showed that the differences in hyphal morphology were more evident on the solid media. After culturing at 37°C, although the WT formed significant wrinkled colonies and hyphal extensions, the mutant formed only smooth colonies and slight hyphae. Particularly under GlcNAc, the colony derived from the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant was smooth (Figure 4B). Accordingly, the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant showed shorter and sparser hyphae when incubated in a liquid-induced medium with GlcNAc as the sole source of carbon (Figure 4C). However, no significant differences were observed in the hyphal length of the fungi cultured in liquid media with other carbon sources except maltose media (Figures S7, Figure S8) compared with the colony formed by the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant, where the WT strain developed wrinkled macro-colonies and extended the hyphae on solid media more evidently. In addition, this was accompanied by the loss of hyphal-related hydrolase activity (Figure S9). Therefore, the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant might have affected the hyphal growth because of its impaired use of carbon sources.

Comparative transcriptome analysis provided information on the QCR7-associated virulence mechanisms of Candida albicans

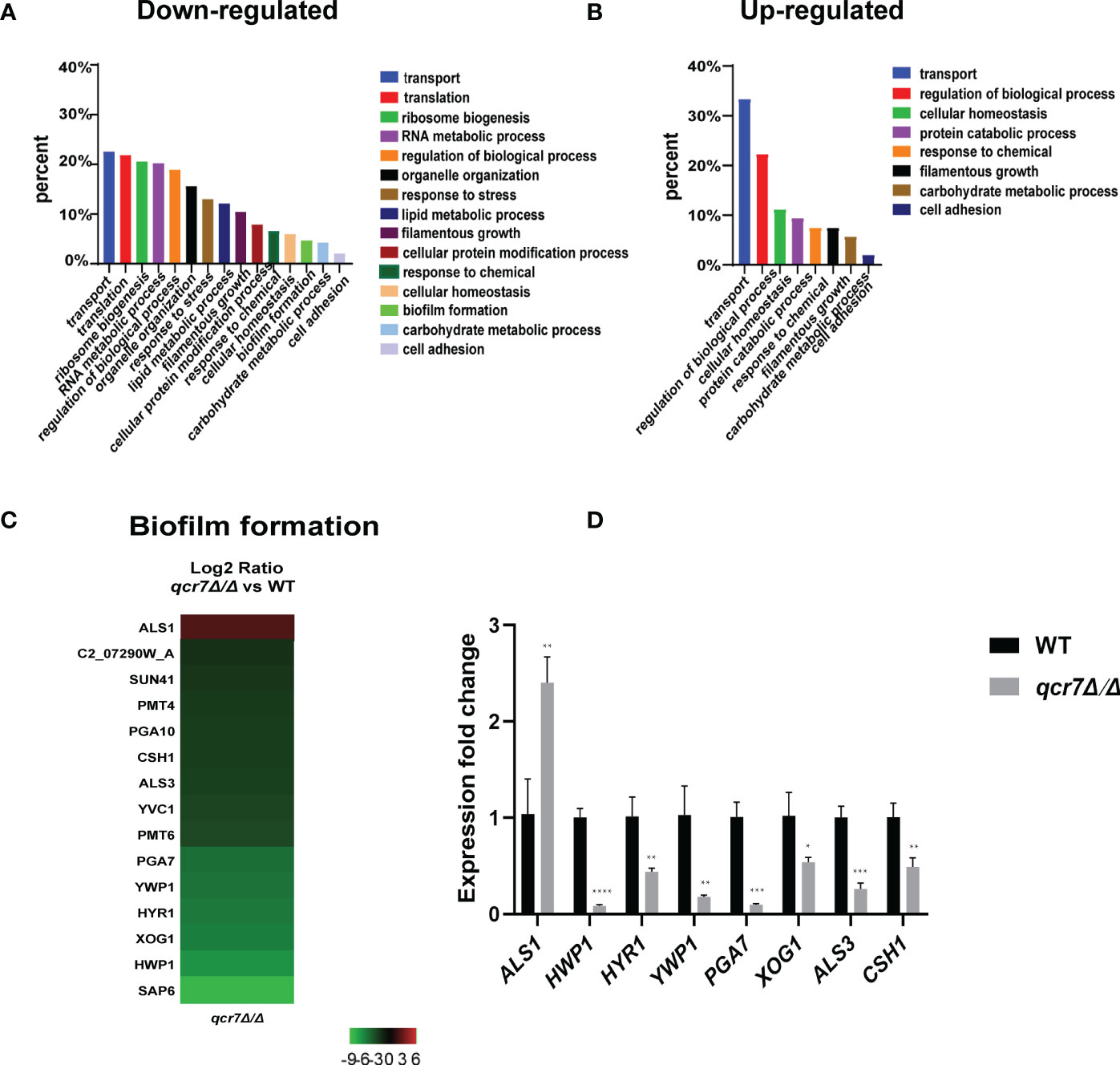

The transcriptome of the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant was compared with that of the WT strain in media mimicking the in vivo conditions (RPMI 1640 medium). The results indicated that 307 genes were downregulated and 54 genes were upregulated with expression-fold changes of >2.0 and <−2.0 (P ≤ 0.05), respectively, in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant compared with the WT strain. Therefore, we subjected these gene sets to pathway analysis using Gene Ontology (GO). Among the 307 downregulated genes, the most enriched GO term was transport (22.5%). The enriched terms also included processes such as translation (21.8%), ribosome biogenesis (20.5%), RNA metabolic processes (20.2%), the regulation of biological processes (18.9%), organelle organization (15.6%), response to stress (13.0%), and lipid metabolic processes (12.1%), followed by those related to filamentous growth (10.4%), cellular protein modification processes, response to chemicals, cellular homeostasis, biofilm formation (4.6%), carbohydrate metabolic processes (4.2%), and cell adhesion (2%) (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the list of the 54 upregulated genes list comprised 26 genes with unknown functions. The eight highest gene categories that were downregulated included those related to transport (33.3%), the regulation of biological processes (22.2%), cellular homeostasis (11.1%), protein catabolic process (9.3%), and responses to chemicals, including those related to filamentous growth, carbohydrate metabolic process, and cell adhesion (1.9%) (Figure 5B). An analysis of the GO category “cellular components” also found GO terms associated with the membrane and cell wall to be significantly (P ≤ 0.05) enriched in the downregulated gene sets (Figure S10). Regarding the process related to sugar transportation through the plasma membrane, it can be proposed that membrane downregulation by some genes can affect the use of sugar. Previous evidence showed that mitochondrial function directly influences the cell wall (Duvenage et al., 2019). In addition, the absence of the Complex I regulator Goa1 (She et al., 2016) or the mitochondrial sorting and assembly machinery subunit Sam37 (Qu et al., 2012) results in defective cell-wall integrity (CWI), suggesting that the mitochondrial gene defects affecting the cell wall also apply to the Complex III regulator Qcr7. Intriguingly, an analysis of the downregulated gene sets related to filamentous growth and biofilm formation revealed that significantly downregulated genes were involved in regulating biofilm formation (SAP6, HWP1, XOG1, HYR1, YWP1, ALS3, CSH1, PGA10, and SUN41) and filamentous growth (ENO1, SSB1, DDR48, ALS3, and SUN41); these genes were also identified as cell-wall-related genes, indicating that impaired filamentous growth and biofilm formation were partly affected by the downregulation of cell-wall-associated genes. Moreover, several genes encoding glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored cell-wall proteins that influenced the cross-linking of cell-wall components were also downregulated (PGA3, PGA6, PGA7, PGA10, PGA34, PGA35, PGA53, PGA54, PGA56, PGA59, and PGA63) (Figure S10). To verify whether QCR7 deletion negatively affects CWI, we spotted it on a medium containing cell-wall stressors, such as CFW, CR, caspofungin, and SDS. We observed that disrupting Qcr7 led to damaged cell-wall biosynthesis (Figure S10).

Figure 5 Comparative transcriptomic analysis of QCR7 mutants of C albicans. The distribution of significantly downregulated (A) or upregulated (B) genes in the GO category “molecular process” following qcr7Δ/Δ, compared with the wild type. (C) A heatmap displaying the upregulated and downregulated genes that associate partly with the GO category “biofilm formation”. Fold enrichment of these genes is shown in Table S3. (D) Validation of the genome-wide transcriptional data by qPCR in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant strain. “*” represents p < 0.05, “**” represents p < 0.01, “***” represents p < 0.001 and “****” represents p < 0.0001 for the WT vs. mutant strains.

Furthermore, our RNA-sequencing data revealed the most significant downregulation of several genes of biofilm formation, and we confirmed the reliability of the results by RT-qPCR (Figures 5C, D). In C. albicans, biofilm development requires six master transcriptional regulators (Bcr1, Brg1, Ndt80, Rob1, Tec1, Efg1) (Nobile et al., 2012). We further investigated whether six core biofilm regulatory factors in C. albicans regulate QCR7 expression. As shown in Figure S11, the deletion of these master regulator significantly affects QCR7 expression. In addition, we overexpressed QCR7 in these transcription-factor-encoding knockout strains and performed biofilm formation assays, showing that QCR7 could partially restore the biofilm deficiency caused by NDT80 deletion (Figure S12). These data can demonstrate that Qcr7 is regulated by Ndt80 to influence biofilm formation.

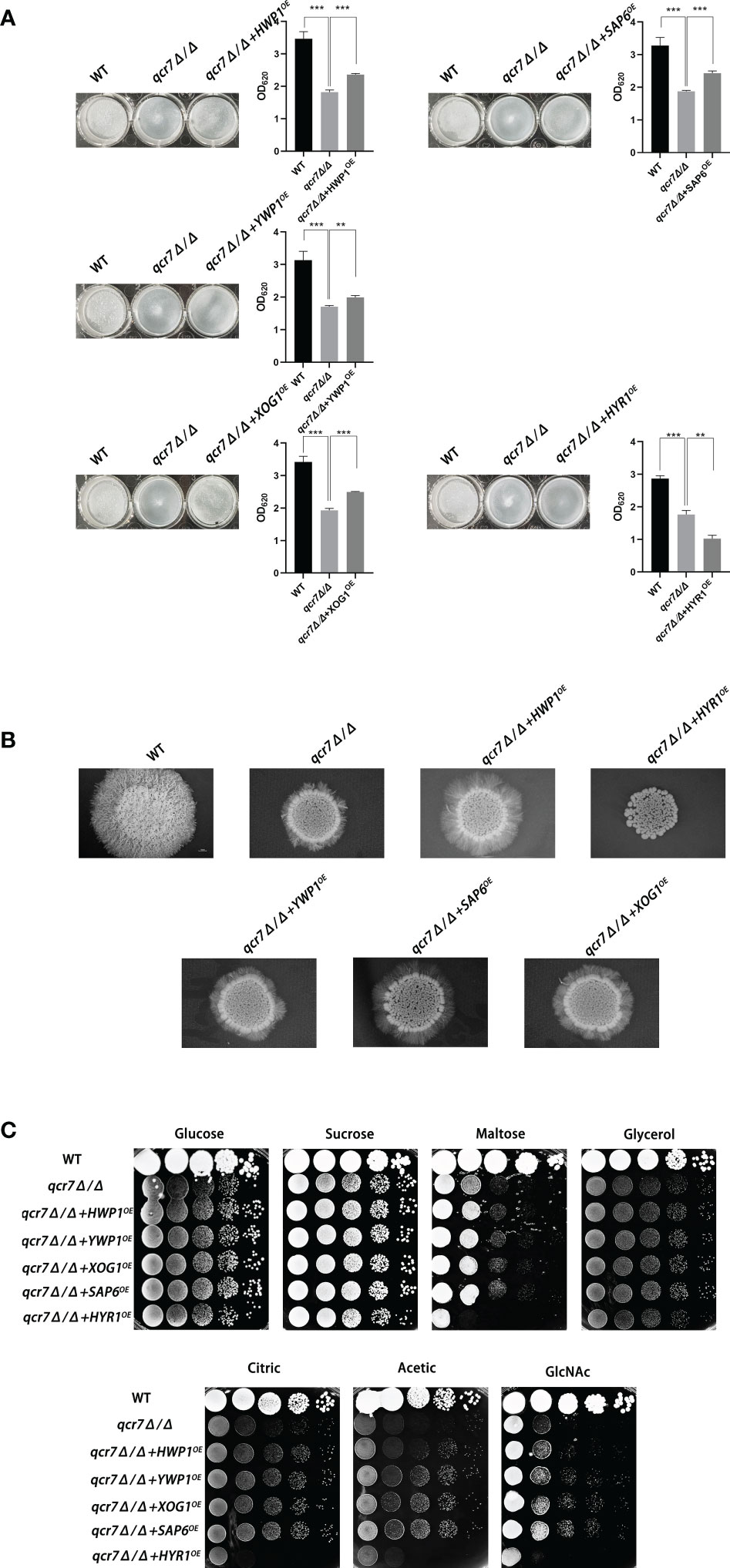

Qcr7-regulated genes in cell surfaces play a significant role in biofilm formation, hyphal growth on solids, and the use of carbon sources

To further identify downstream biofilm-formation-related genes regulated by QCR7 and the probable mechanisms involved, we selected five genes (HWP1, YWP1, XOG1, HYR1, and SAP6) known to play an important role in biofilm formation and that were downregulated with an expression-fold change of < -5.0 (P ≤ 0.05) in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant compared with the WT strain based on the transcriptome and overexpression of theses gene in the qcr7Δ/Δ background. We found that the overexpression of four genes (HWP1, YWP1, XOG1, and SAP6) partly but significantly rescued the qcr7Δ/Δ biofilm phenotype, but that HYR1 overexpression in this genetic background suppressed the biofilm phenotype of the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant even more (Figure 6A). Furthermore, the partial restoration of the phenotype also occurred in hyphal growth in solid medium. The increased expression levels of HWP1, YWP1, XOG1, and SAP6 in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant formed a halo of more abundant and longer agar-invading hyphae around the colony center than those seen with the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant, whereas the overexpression of HYR1 showed no formation of a halo of agar-invading hyphae (Figure 6B). Considering whether the same mechanism regulates the reduction of each virulence phenotype, and restricted carbon source utilization, we tested for growth on several carbon sources to examine the utilization of the carbon sources by these strains. The results showed that carbon use was consistent with the virulence phenotype, with four genes (HWP1, YWP1, XOG1, SAP6) overexpressed in the qcr7Δ/Δ background showing a partial reversal of the use of these carbon sources, while the overexpression of HYR1 inhibited the use of the carbon source even more (Figure 6C). The mechanism behind this is not yet clear.

Figure 6 Biofilm formation, hyphal growth on solid, and spot assay on cell-wall stressors or multiple alternative carbon sources with WT, qcr7Δ/Δ, HWP1, YWP1, XOG1, SAP6, and HYR1 overexpressing strains in the qcr7Δ/Δ background. (A) Biofilm formation (48h, 37°C) of strains was profiled and statistically compared to reference strain C albicans SN250. (B) Each cell type (1 × 105 cells in 5 µl of PBS) was spotted on the Spider medium at 37°C. Photographs were then taken after 7 days of growth. (C) The sensitivities of wild-type strain, qcr7Δ/Δ strain, and overexpression strain to different carbon-source conditions were observed by spot assay and incubation was conducted at 30°C for 2 days before photographs were taken. “**” represents p < 0.01 and “***” represents p < 0.001 for the WT or overexpressing strains vs. mutant strains.

Altogether, the above results confirm that the restricted carbon utilization caused by the deletion of QCR7 is related to the impairment of the virulence phenotype and cell-surface changes.

Discussion

In this study, we constructed eight subunit-encoding genes mutant that are viable in Complex III and investigated the effects of the deletion of these genes on the ability of carbon-source utilization and on key virulence phenotypes of C. albicans. We found that the deletion of RIP1, a catalytic subunit of Complex III, had a significant effect on both the carbon-source utilization and virulence of C. albicans, which was consistent with a previous study (Vincent et al., 2016). While we were surprised to find that the deletion of Qcr7, one of the seven non-catalytic subunits of Complex III, had a phenotypic deficiency in the ability of C. albicans to maintain hyphal growth on solid media and biofilm formation compared to the other subunit knockout strains, we first considered this in terms of the constitutive structure of Qcr7 as a direct effect. Qcr7, the earliest protein to interact with the fully hemylated Cytb (Hildenbeutel et al., 2014), is present in all bc1 Complex assembly intermediates containing nuclear coding subunits and therefore plays an important role in the assembly of Complex III. In order to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of the QCR7 knockout on the biological and pathogenic functions of C. albicans, we then carried out a series of studies. Because the preliminary results based on evident phenotypic changes, which relate to virulence factors, suggested that QCR7 deletion reduces the invasive infection of C. albicans, we used mice as the host systems to assess the effects of QCR7 deletion on the virulence of C. albicans in vivo. Although all the mice infected with the mutant survived beyond 3 weeks after infection, those infected with the WT strain died within a week. A histological analysis and fungal-kidney-tissue loads revealed the lack of Candida cells in the kidneys of the mice infected with the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant, showing significantly less necrosis and less-severe tissue damage. Therefore, the ability of the mutants to invade and colonize the host tissues might have been weakened.

Carbon sources are extremely diverse in different host environments, making it important for C. albicans to use alternative carbon sources. Although it inhabits niches with limited glucose availability, it is also found in environments rich in alternative carbon sources. Therefore, this fungus uses nonfermentable carbon sources, such as acetate or lactate, to adapt to host environments (Piekarska et al., 2006). Alternatively, the efficient assimilation of multiple nonfermentable carbon sources enhances its virulence (Ramírez and Lorenz, 2007).

GlcNAc, an alternative carbon source, can be easily found in the mucosal membranes of human hosts (Sengupta and Datta, 2003), and it can strongly induce hyphal morphogenesis (Williams and Lorenz, 2020). In addition, studies have reported that C. albicans can use amino acids as carbon sources, which is crucial for its virulence (Vylkova et al., 2011). To further determine the effect of QCR7 deletion on carbon-source utilization, a wild-type allele was restored to the QCR7 knockout strain and tested in a more diverse-carbon-source medium. It was found that QCR7 complementation can compensate for QCR7 deficiency, resulting in growth-lag phase on glucose, mannitol, and sucrose as carbon sources and growth defects on non-fermentable carbon sources (glycerin, citrate, and acetate), GlcNAc, lactate and amino acids as carbon sources. The reduced ability to utilize carbon sources raised the question of whether the energy supply within the strain is affected by the deletion of QCR7. The mitochondria are the primary sources of energy for cell growth, apoptosis, proliferation, and other cellular processes. Therefore, mitochondrial function is crucial in regulating the morphology and virulence of C. albicans. The assay of mitochondrial function suggested that QCR7 deletion affected intracellular ATP content, which may be related to Qcr7 as a subunit in the electron transport chain, affecting the level of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), and the elevated intracellular ROS levels also further confirmed the dysfunctions in the mitochondria.

The biofilms of C. albicans are highly structured; they contain yeast forms of cells, pseudohyphal cells, and hyphal cells surrounded by an extracellular matrix (Fox and Nobile, 2012). Furthermore, C. albicans biofilms functions as a reservoir of drug-resistant cells that can isolate, multiply, and cause bloodstream infections (Lohse et al., 2018). In addition to forming biofilms on implanted medical devices, the surface of the host is also a major location for the formation of C. albicans biofilms. The transition from commensal to pathogenic C. albicans requires effective adaptation to the host environment. It has been observed that carbon plays a central role in metabolism and is key to host-surface colonization during infection (Brown et al., 2014). Glucose and other sugars influence the ability of C. albicans to form biofilms (Ng et al., 2016; Pemmaraju et al., 2016). Moreover, the biofilm’s thickness and structure vary with different carbon sources (Pemmaraju et al., 2016). We further observed that the mitochondrial dysfunction induced by the QCR7 knockout impaired the biofilm formation of the C. albicans. Compared with the WT strain, the QCR7 deletion diminished biofilm formation in the Spider medium supplemented with mannitol, glucose, GlcNAc, maltose, and sucrose as the sole carbon source. Robust hyphal formation is necessary for C. albicans-biofilm maturation. As reported previously, the yeast accounting for the hyphal transformation of C. albicans is key to causing invasive infections by invading epithelial cells and causing tissue damage. Therefore, the ability of fungi to form hyphae is evaluated through their filamentous growth abilities in liquid cultures or colonial morphology on solid media (Sudbery, 2011). Furthermore, the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant showed significantly different hyphal morphologies when stimulated by multiple alternative carbons. Similar phenotypic differences in biofilm formation were also observed in the hyphal growth on solid media, particularly when GlcNAc was used as the sole source of carbon. The hyphal-growth inhibition was also significant in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant under liquid-induced medium with GlcNAc as the sole carbon source, but not with other carbon sources. In addition, the activity of hyphae-related hydrolases decreased.

A global transcriptional approach was adopted to investigate which genes influence these phenotypic changes. Within the GO category “biological processes”, selected pathways associated with crucial virulence factors, such as those gene involved in filamentous growth, biofilm formation, hyphal growth, and cell adhesion, were downregulated, as well as genes assigned to transport, carbohydrate metabolic processes, and lipid-metabolic processes.

Those with significant differential changes were found to be involved in carbohydrate transport on the basis of the functional analysis of the downregulated genes. Although partially related genes were upregulated to compensate for the effect, the effect was insignificant, which indicated that QCR7 deletion weakened the carbohydrate-use ability of the C. albicans. For the C. albicans, it was necessary to coordinate the use of sugars as energy sources with the production of active sugars (uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucose, guanosine diphosphate-mannose, and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine), which combine to synthesize major cell-wall polysaccharides (glucan, mannose, and chitin) for the biosynthesis of new cell walls (Piškur and Compagno, 2014). However, as expected, the QCR7 deletion affected the integrity of the cell wall, which was consistent with the transcriptional response of the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant. Alternatively, for the GO cellular components, the GO terms associated with the membrane and cell wall were significantly enriched in the downregulated gene sets. Notably, the mutant exhibited hypersensitivity to various cell-wall stressors, such as CFW, caspofungin, CR and SDS.

According to the comparative transcriptome analysis and several pathogenic phenotypes of the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant, these data revealed that the QCR7 deletion had the most significant effect on biofilm formation. In C. albicans, a core complex regulatory network is critical for biofilm formation. Here, we showed that the six core biofilm-regulatory-factor (BCR1, BRG1, NDT80, ROB1, TEC1, EFG1) mutants exhibited significantly downregulated expression of QCR7.We then increased the expression level of QCR7 in these mutants and performed a comparison of the biofilm-forming ability, showing that increased expression levels of QCR7 partially restored the biofilm defects caused by the NDT80 knockdown. Our findings provide additional support for the role of QCR7 in biofilm formation regulated by NDT80. In addition, to better understand whether the significant downregulation of biofilm-formation-related genes in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant was the key factor affecting the virulence factors, we overexpressed five significantly downregulated biofilm-formation-related genes in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant background, showing that the biofilm phenotype of the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant was partially reversed after the overexpression of four genes, while the overexpression of one gene further attenuated the biofilm phenotype of the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant. Intriguingly, Ywp1 is a yeast-forming cell-wall protein, which is known to inhibit biofilm formation (Granger et al., 2005). Hyr1 is a GPI-anchored cell-wall protein, which is expressed during hyphal development. There are studies that prove that this mutant may have a moderately attenuated biofilm phenotype (Dwivedi et al., 2011). However, the biofilm-mass formation of qcr7Δ/Δ mutant was increased by the overexpression of YWP1, while the biofilm-deficient phenotype of the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant was more pronounced through the overexpression of HYR1. Previous studies identified HWP1, XOG1, and SAP6 as biofilm-association genes for managing C. albicans virulence (Nobile et al., 2006; Taff et al., 2012; Winter et al., 2016). The increased expression of these three genes in the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant background could partially rescue the biofilm phenotype. The hyphal growth on solids of these five overexpressing strains agrees with observations on biofilm formation, according to which HWP1, YWP1, XOG1, and SAP6 overexpression partly but significantly reversed the qcr7Δ/Δ mutant phenotype, and yet HYR1 overexpression additively attenuated pathogenic phenotypes. A similar phenomenon was also observed in the experiment on carbon-source utilization. Taking into account all these factors, we may reasonably conclude that the deletion of QCR7 had the most significant effect on the cell surface, thus affecting a variety of virulence factors. The increase in the expression level of a series of gene-encoding cell-surface proteins resulted in the restoration of the corresponding virulence phenotype and carbon-source utilization.

In summary, we confirmed the key role of Qcr7 in the involvement of complex III in the virulence exertion of Candida albicans, and reported the importance of Qcr7 for maintaining mitochondrial function and coping with the complex carbon-derived environment in the host. The effect of Qcr7 on the biofunctional structure of Candida albicans and the related mechanism on biofilm were explored in depth, suggesting that Qcr7 may be expected to be an active and effective antifungal drug target.

The respiratory chain has now been proposed as an attractive target to be developed as a target against fungal infections (Duvenage et al., 2019). As an adaptation to changes in the host microenvironment and in response to host immune cell attack, the way in which C.albicans reprograms its metabolism by altering its central carbon metabolism to take advantage of alternative carbon sources is important for the maintenance of its virulence (Han et al., 2011). And the in-depth study of the respiratory chain, the main site of carbon metabolism, has not only identified respiration itself as a key condition for virulence, but also identified specific genes in the CTG branch involving the respiratory chain, offering the possibility of developing new therapeutic targets against Candida species infection (Murante and Hogan, 2019; Sun et al., 2019). The successful development of complex III inhibitors and the mature application of complex III as a drug target in the field of pesticides have provided us with the prerequisite ideas to explore the function of the auxiliary subunits in C.albicans complex III. The completion of this study will also provide a scientific basis for further screening of more active and effective antifungal drugs.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, PRJNA802957.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Nanchang University (approval number: NCUSYDWFL-201035).

Author contributions

LZ, YH, JT, and XH designed the study. LZ, YH, JT, NH, YZ, JC, QL, and YC performed the experiments data analyses and wrote the original draft. LZ and XH edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32060040 and 31760261), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20192ACBL21042, 20202BAB216045 and 20204BCJL23054).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nanchang University Medical School for providing the space and equipment necessary to conduct this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1136698/full#supplementary-material

References

Abbes, S., Amouri, I., Trabelsi, H., Neji, S., Sellami, H., Rahmouni, F., et al. (2017). Analysis of virulence factors and in vivo biofilm-forming capacity of yarrowia lipolytica isolated from patients with fungemia. Med. Mycol. 55, 193–202. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myw028

Barelle, C. J., Priest, C. L., Maccallum, D. M., Gow, N., Odds, F. C., Brown, A. J. P. (2006). Niche-specific regulation of central metabolic pathways in a fungal pathogen. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 961–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00676.x

Brandt, U., Uribe, S., Schägger, H., Trumpower, B. L. (1994). Isolation and characterization of QCR10, the nuclear gene encoding the 8.5-kDa subunit 10 of the saccharomyces cerevisiae cytochrome bc1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 12947–12953. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)99967-9

Brown, A. J. P., Brown, G. D., Netea, M. G., Gow, N. (2014). Metabolism impacts upon candida immunogenicity and pathogenicity at multiple levels. Trends In Microbiol. 22, 614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.07.001

Brown, A. J. P., Odds, F. C., Gow, N. (2007). Infection-related gene expression in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.04.001

Crandall, M., Edwards, J. E. (1987). Segregation of proteinase-negative mutants from heterozygous Candida albicans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133, 2817–2824. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-10-2817

Duvenage, L., Munro, C. A., Gourlay, C. W. (2019). The potential of respiration inhibition as a new approach to combat human fungal pathogens. Curr. Genet. 65, 1347–1353. doi: 10.1007/s00294-019-01001-w

Dwivedi, P., Thompson, A., Xie, Z., Kashleva, H., Ganguly, S., Mitchell, A. P., et al. (2011). Role of Bcr1-activated genes Hwp1 and Hyr1 in Candida albicans oral mucosal biofilms and neutrophil evasion. PLoS One 6, e16218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016218

Fox, E. P., Nobile, C. J. (2012). A sticky situation: untangling the transcriptional network controlling biofilm development in Candida albicans. Transcription 3, 315–322. doi: 10.4161/trns.22281

Gerami-Nejad, M., Zacchi, L. F., Mcclellan, M., Matter, K., Berman, J. (2013). Shuttle vectors for facile gap repair cloning and integration into a neutral locus in Candida albicans. Microbiol. (Reading England) 159, 565–579. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.064097-0

Gow, N., Yadav, B. (2017). Microbe profile: Candida albicans: a shape-changing, opportunistic pathogenic fungus of humans. Microbiol. (Reading England) 163, 1145–1147. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000499

Grahl, N., Demers, E. G., Lindsay, A. K., Harty, C. E., Willger, S. D., Piispanen, A. E., et al. (2015). Mitochondrial activity and Cyr1 are key regulators of Ras1 activation of c. albicans virulence pathways. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005133. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005133

Granger, B. L., Flenniken, M. L., Davis, D. A., Mitchell, A. P., Cutler, J. E. (2005). Yeast wall protein 1 of Candida albicans. Microbiol. (Reading England) 151, 1631–1644. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27663-0

Guo, H., Xie, S. M., Li, S. X., Song, Y. J., Lv, X. L., Zhang, H. (2014). Synergistic mechanism for tetrandrine on fluconazole against Candida albicans through the mitochondrial aerobic respiratory metabolism pathway. J. Med. Microbiol. 63, 988–996. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.073890-0

Han, T.-L., Cannon, R. D., Villas-Bôas, S. G. (2011). The metabolic basis of Candida albicans morphogenesis and quorum sensing. Fungal Genet. Biol. 48, 747–763. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.04.002

Henkels, K. M., Muppani, N. R., Gomez-Cambronero, J. (2016). PLD-specific small-molecule inhibitors decrease tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils infiltration in breast tumors and lung and liver metastases. PloS One 11, e0166553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166553

Hildenbeutel, M., Hegg, E. L., Stephan, K., Gruschke, S., Meunier, B., Ott, M. (2014). Assembly factors monitor sequential hemylation of cytochrome b to regulate mitochondrial translation. J. Cell Biol. 205, 511–524. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401009

Huang, X., Chen, X., He, Y., Yu, X., Li, S., Gao, N., et al. (2017). Mitochondrial complex I bridges a connection between regulation of carbon flexibility and gastrointestinal commensalism in the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006414. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006414

Hunte, C., Palsdottir, H., Trumpower, B. L. (2003). Protonmotive pathways and mechanisms in the cytochrome bc1 complex. FEBS Lett. 545, 39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00391-0

Jamal, M., Ahmad, W., Andleeb, S., Jalil, F., Imran, M., Nawaz, M. A., et al. (2018). Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. JCMA 81 (1), 7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2017.07.012

Leunk, R. D., Moon, R. J. (1979). Physiological and metabolic alterations accompanying systemic candidiasis in mice. Infection Immun. 26, 1035–1041. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.3.1035-1041.1979

Li, S.-X., Song, Y.-J., Zhang, Y.-S., Wu, H.-T., Guo, H., Zhu, K.-J., et al. (2017). Mitochondrial complex V α subunit is critical for pathogenicity through modulating multiple virulence properties. Front. Microbiol. 8, 285. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00285

Li, S.-X., Wu, H.-T., Liu, Y.-T., Jiang, Y.-Y., Zhang, Y.-S., Liu, W.-D., et al. (2018). The FF-ATP synthase β subunit is required for pathogenicity due to its role in carbon flexibility. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1025. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01025

Li, S., Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z., Tang, C., et al. (2021). The δ subunit of F1Fo-ATP synthase is required for pathogenicity of Candida albicans. Nat. Commun. 12, 6041. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26313-9

Lin, W., Yuan, D., Deng, Z., Niu, B., Chen, Q. (2019). The cellular and molecular mechanism of glutaraldehyde-didecyldimethylammonium bromide as a disinfectant against Candida albicans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 126, 102–112. doi: 10.1111/jam.14142

Lohse, M. B., Gulati, M., Johnson, A. D., Nobile, C. J. (2018). Development and regulation of single- and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.107

Lorusso, M., Cocco, T., Boffoli, D., Gatti, D., Meinhardt, S., Ohnishi, T., et al. (1989). Effect of papain digestion on polypeptide subunits and electron-transfer pathways in mitochondrial b-c1 complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 179, 535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14580.x

Murante, D., Hogan, D. A. (2019). New mitochondrial targets in fungal pathogens. MBio 10 (5), e02258–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02258-19

Neji, S., Hadrich, I., Trabelsi, H., Abbes, S., Cheikhrouhou, F., Sellami, H., et al. (2017). Virulence factors, antifungal susceptibility and molecular mechanisms of azole resistance among Candida parapsilosis complex isolates recovered from clinical specimens. J. Biomed. Sci. 24, 67. doi: 10.1186/s12929-017-0376-2

Ng, T. S., Desa, M. N. M., Sandai, D., Chong, P. P., Than, L. T. L. (2016). Growth, biofilm formation, antifungal susceptibility and oxidative stress resistance of Candida glabrata are affected by different glucose concentrations. Infection Genet. Evol. 40, 331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.09.004

Nobile, C. J., Fox, E. P., Nett, J. E., Sorrells, T. R., Mitrovich, Q. M., Hernday, A. D., et al. (2012). A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell 148, 126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048

Nobile, C. J., Johnson, A. D. (2015). Candida albicans biofilms and human disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330

Nobile, C. J., Nett, J. E., Andes, D. R., Mitchell, A. P. (2006). Function of Candida albicans adhesin Hwp1 in biofilm formation. Eukaryotic Cell 5, 1604–1610. doi: 10.1128/EC.00194-06

Nobile, C. J., Nett, J. E., Hernday, A. D., Homann, O. R., Deneault, J.-S., Nantel, A., et al. (2009). Biofilm matrix regulation by Candida albicans Zap1. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000133

Noble, S. M., French, S., Kohn, L. A., Chen, V., Johnson, A. D. (2010). Systematic screens of a Candida albicans homozygous deletion library decouple morphogenetic switching and pathogenicity. Nat. Genet. 42, 590–598. doi: 10.1038/ng.605

Noble, S. M., Johnson, A. D. (2005). Strains and strategies for large-scale gene deletion studies of the diploid human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryotic Cell 4, 298–309. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.298-309.2005

Nolfi-Donegan, D., Braganza, A., Shiva, S. (2020). Mitochondrial electron transport chain: Oxidative phosphorylation, oxidant production, and methods of measurement. Redox Biol. 37, 101674. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101674

Pemmaraju, S. C., Pruthi, P. A., Prasad, R., Pruthi, V. (2016). Modulation of Candida albicans biofilm by different carbon sources. Mycopathologia 181, 341–352. doi: 10.1007/s11046-016-9992-8

Piekarska, K., Mol, E., Van Den Berg, M., Hardy, G., Van Den Burg, J., Van Roermund, C., et al. (2006). Peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation is not essential for virulence of Candida albicans. Eukaryotic Cell 5, 1847–1856. doi: 10.1128/EC.00093-06

Pradhan, A., Avelar, G. M., Bain, J. M., Childers, D. S., Larcombe, D. E., Netea, M. G., et al. (2018). Hypoxia promotes immune evasion by triggering β-glucan masking on the Candida albicans cell surface via mitochondrial and cAMP-protein kinase a signaling. MBio 9 (6), e01318–18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01318-18

Qu, Y., Jelicic, B., Pettolino, F., Perry, A., Lo, T. L., Hewitt, V. L., et al (2012). Mitochondrial sorting and assembly machinery subunit Sam37 in Candida albicans: Insight into the roles of mitochondria in fitness, cell wall integrity, and virulence. Eukaryotic cell 11, 532–544.

Ramírez, M. A., Lorenz, M. C. (2007). Mutations in alternative carbon utilization pathways in Candida albicans attenuate virulence and confer pleiotropic phenotypes. Eukaryotic cell 6, 280–290.

Sasaki, K., Terker, A. S., Pan, Y., Li, Z., Cao, S., Wang, Y., et al. (2021). Deletion of myeloid interferon regulatory factor 4 (Irf4) in mouse model protects against kidney fibrosis after ischemic injury by decreased macrophage recruitment and activation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 1037–1052. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020071010

Sengupta, M., Datta, A. (2003). Two membrane proteins located in the nag regulon of Candida albicans confer multidrug resistance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301, 1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00094-9

She, X., Khamooshi, K., Gao, Y., Shen, Y., Lv, Y., Calderone, R., et al. (2015). Fungal-specific subunits of the Candida albicans mitochondrial complex I drive diverse cell functions including cell wall synthesis. Cell. Microbiol. 17, 1350–1364. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12438

She, X., Calderone, R., Kruppa, M., Lowman, D., Williams, D., Zhang, L., et al (2016). Cell wall N-linked mannoprotein biosynthesis requires Goa1p, a putative regulator of mitochondrial complex I in candida albicans. PloS one 11, e0147175.

Silva, S., Henriques, M., Martins, A., Oliveira, R., Williams, D., Azeredo, J. (2009). Biofilms of non-Candida albicans candida species: quantification, structure and matrix composition. Med. Mycol. 47, 681–689. doi: 10.3109/13693780802549594

Sudbery, P. E. (2011). Growth of Candida albicans hyphae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 737–748. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2636

Sun, N., Parrish, R. S., Calderone, R. A., Fonzi, W. A. (2019). Unique, diverged, and conserved mitochondrial functions influencing Candida albicans respiration. MBio 10 (3), e00300–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00300-19

Taff, H. T., Nett, J. E., Zarnowski, R., Ross, K. M., Sanchez, H., Cain, M. T., et al. (2012). A Candida biofilm-induced pathway for matrix glucan delivery: implications for drug resistance. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002848. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002848

Tzagoloff, A. (1995). Ubiquinol-cytochrome-c oxidoreductase from saccharomyces cerevisiae. Meth. Enzymol. 260, 51–63. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60129-5

Vincent, B. M., Langlois, J.-B., Srinivas, R., Lancaster, A. K., Scherz-Shouval, R., Whitesell, L., et al. (2016). A fungal-selective cytochrome bc inhibitor impairs virulence and prevents the evolution of drug resistance. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 978–991. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.06.016

Vylkova, S., Carman, A. J., Danhof, H. A., Collette, J. R., Zhou, H., Lorenz, M. C. (2011). The fungal pathogen Candida albicans autoinduces hyphal morphogenesis by raising extracellular pH. mBio 2, e00055–e00011. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00055-11

Williams, R. B., Lorenz, M. C. (2020). Multiple alternative carbon pathways combine to promote Candida albicans stress resistance, immune interactions, and virulence. mBio 11 (1), e03070–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03070-19

Keywords: Candida albicans, virulence, biofilm, hyphae, mitochondrial disorder

Citation: Zeng L, Huang Y, Tan J, Peng J, Hu N, Liu Q, Cao Y, Zhang Y, Chen J and Huang X (2023) QCR7 affects the virulence of Candida albicans and the uptake of multiple carbon sources present in different host niches. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13:1136698. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1136698

Received: 03 January 2023; Accepted: 09 February 2023;

Published: 27 February 2023.

Edited by:

Donglei Sun, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Mohammed Yosri Mohammed, Al-Azhar University, EgyptYanli Chen, University of Maryland, College Park, United States

Copyright © 2023 Zeng, Huang, Tan, Peng, Hu, Liu, Cao, Zhang, Chen and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaotian Huang, eHRodWFuZ0BuY3UuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Lingbing Zeng

Lingbing Zeng Yongcheng Huang

Yongcheng Huang Junjun Tan

Junjun Tan Jun Peng2

Jun Peng2 Niya Hu

Niya Hu Qiong Liu

Qiong Liu Yuping Zhang

Yuping Zhang Junzhu Chen

Junzhu Chen Xiaotian Huang

Xiaotian Huang