95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. , 15 June 2022

Sec. Microbes and Innate Immunity

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.925746

This article is part of the Research Topic Understanding the Effects of Metabolites and Trace Minerals on Microbes During Infection View all 5 articles

Host and pathogen metabolism have a major impact on the outcome of infection. The microenvironment consisting of immune and stromal cells drives bacterial proliferation and adaptation, while also shaping the activity of the immune system. The abundant metabolites itaconate and adenosine are classified as anti-inflammatory, as they help to contain the local damage associated with inflammation, oxidants and proteases. A growing literature details the many roles of these immunometabolites in the pathogenesis of infection and their diverse functions in specific tissues. Some bacteria, notably P. aeruginosa, actively metabolize these compounds, others, such as S. aureus respond by altering their own metabolic programs selecting for optimal fitness. For most of the model systems studied to date, these immunometabolites promote a milieu of tolerance, limiting local immune clearance mechanisms, along with promoting bacterial adaptation. The generation of metabolites such as adenosine and itaconate can be host protective. In the setting of acute inflammation, these compounds also represent potential therapeutic targets to prevent infection.

Bacterial infections, especially those due to antimicrobial- resistant organisms, are a worldwide public health problem (Murray et al., 2022). While resistance has imposed treatment challenges, substantial mortality is nonetheless associated with pathogens that are entirely susceptible to available therapies. This suggests the influence of other factors enabling successful infection. The importance of host-and-pathogen-derived metabolites, which impact bacterial adaptation and shape the nature of the immune response, is increasingly recognized. Proinflammatory immunometabolites are critical in activating host defenses, and their anti-inflammatory counterparts function to prevent associated toxicities. As a consequence of effects on host immunity and bacterial survival, the fluctuation of pro and anti-inflammatory metabolites has profound effects in determining the outcome of infection.

The innate immune response to bacteria is initiated by ligand-receptor interactions to bacterial components or pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on macrophages, such as TLR4, activate the transcription of NF-κB to initiate expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Along with protein secretion, macrophages undergo metabolic reprogramming, shifting from their resting state of oxidative phosphorylation to use aerobic glycolysis (Peace and O’Neill, 2022). This process leads to the succinate-mediated activation of the transcription factor HIF1α and the production of IL-1β, which favor the differentiation of CD4+ Th17 and Th1 effector cells (Peace and O’Neill, 2022). Equally important are the proteins and metabolites that suppress inflammation and act to prevent the ensuing damage caused by neutrophil oxidants and proteases. A component of this regulatory process is HIF-1α, a transcription factor that drives the expression of acod1 or irg1 generating the anti-inflammatory product itaconate (Peace and O’Neill, 2022). The recruitment of regulatory lymphocytes also contributes by dampening inflammation via the ectonucleotidase-mediated synthesis of adenosine, a potent anti-inflammatory molecule. These metabolites, which we will discuss in detail, function to prevent tissue damage. However, metabolites countering the immune response to infection can have major roles in promoting bacterial persistence.

Upon infection, pathogens must rapidly adapt their metabolism to compete for and efficiently utilize available substrates. The release of anti-inflammatory metabolites at the site of infection can affect pathogenesis in two major ways: It can alter the function of host immune cells and it can drive changes in bacterial metabolic activity, selecting for the variants that are optimally fit to persist. This creates a setting of tissue tolerance, in which the host-adapted pathogen and the locally immunosuppressed host generate a state of persistent infection (Schneider and Ayres, 2008; Wong Fok Lung et al., 2022), as found in TB, COPD, cystic fibrosis and other common infections.

In this review we highlight two major immunometabolites, adenosine and itaconate, both of which promote bacterial metabolic responses and inactivate host immune effectors. We aim to highlight the substantial effects of these abundant metabolites on immune clearance mechanisms, reviewing the biochemical and immunological alteration of host defenses. We will also examine how different bacterial species respond to adenosine and itaconate, depending upon their ability to metabolize each potential substrate or exploit its immune effects.

Adenosine belongs to a class of molecules known as purines, which are heterocyclic aromatic compounds including nucleotides (adenine and guanine), deoxynucleotides (deoxyadenine and deoxyguanine) and ribonucleotides (adenosine and guanosine) required for the cellular processes of DNA and RNA replication. Adenosine can be synthesized intracellularly and extracellularly. Intracellular adenosine is generated through S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (SAHases). S-adenosylhomocysteine is converted to adenosine which is secreted to the extracellular space mainly through equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENT1-4) and concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNT1-3) (Dal Ben et al., 2018).

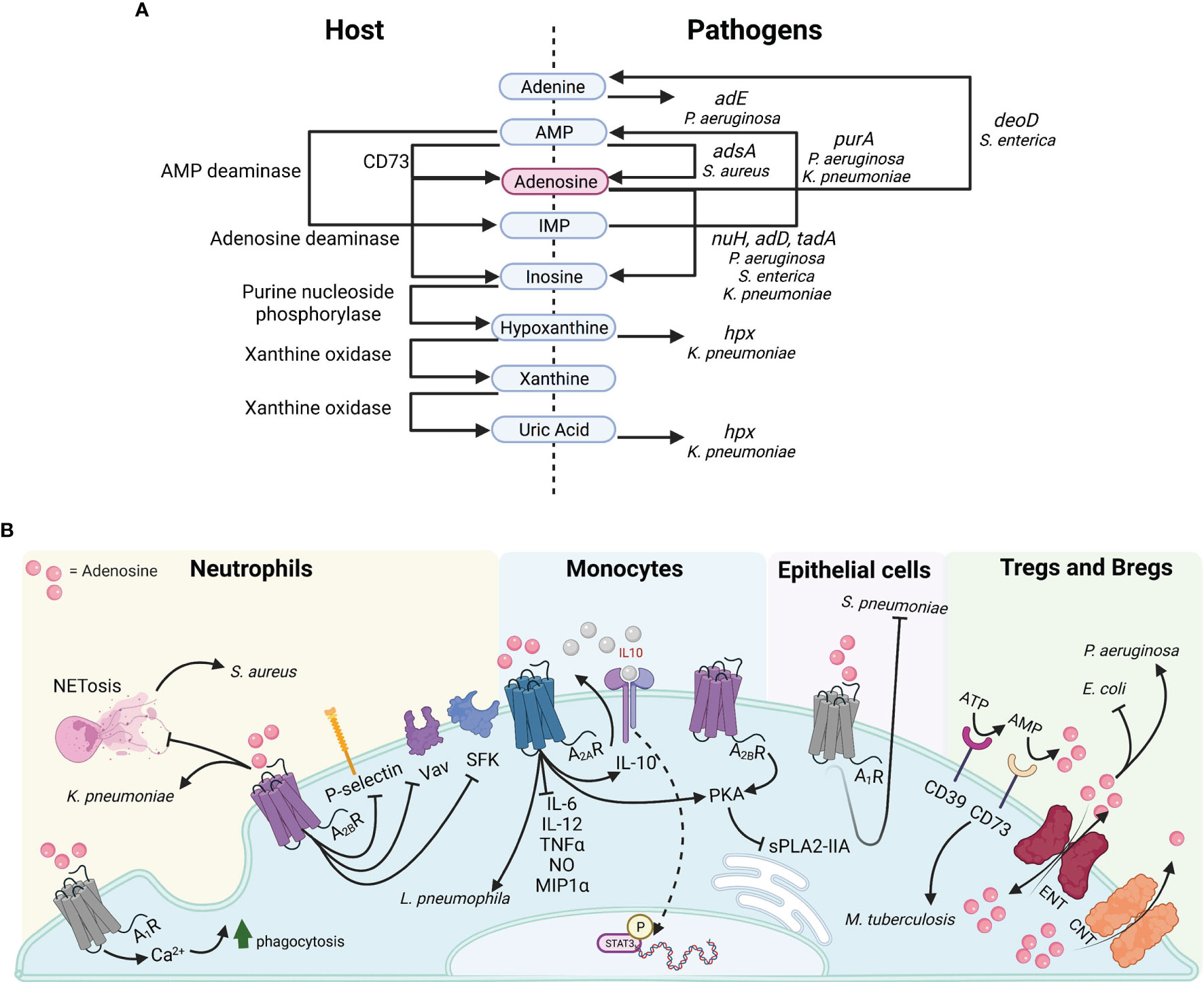

Extracellular adenosine is mainly synthesized through the ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 (Figures 1A, B). In the setting of infection, pro-inflammatory adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is dephosphorylated to adenosine monophosphate (AMP) via the ecto-nucleotide triphosphate hydrolase-1, or CD39, in a Ca2+ and Mg2+ dependent manner (Kaczmarek et al., 1996). The AMP product is then rapidly converted to adenosine via the ecto-5’-nucleotidase, or CD73 (Antonioli et al., 2013). Therefore, the anti-inflammatory role of adenosine is partly attributed to the reduction of extracellular ATP required for its synthesis (Silva-Vilches et al., 2018). CD73 and CD39 deficient mice are common mouse models in studies of the purinergic system as they show substantial decrease in adenosine levels. A non-canonical synthesis pathway involves the hydrolysis of extracellular nicotinamide adenine nucleotide (NAD+) to generate adenosine diphosphate ribose (ADPR) via the enzyme CD38. ADPR is next hydrolyzed to AMP by CD203a, after which CD73 mediates adenosine conversion (Ferretti et al., 2019).

Figure 1 Purine metabolism and adenosine signaling in bacterial pathogenesis. (A) Host proteins (left) and pathogen genes (right) illustrating the synthesis or catabolism of purinergic compounds. (B) Adenosine targets diverse receptors on multiple cell types.

Intracellular regulation of adenosine synthesis occurs through purinergic negative feedback loops. However, once secreted, extracellular concentration is regulated by either its conversion to inosine, xanthine and uric acid via adenosine deaminases (Ada) or xanthine oxidases (Xo), or by reuptake (Ferretti et al., 2019). Of note, both Gram positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, and Gram negatives like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Salmonella enterica produce enzymes facilitating purine degradation for nitrogen and carbon scavenging, as well as adenosine synthesis for immune evasion (Figure 1A).

Adenosinergic signaling occurs via four subtypes of G-protein coupled receptors A1, A2A, A2B, A3, which are all coupled to mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways such as ERK1, ERK2, c-JUN N-terminal kinase, and p38 MAPK (Antonioli et al., 2013). Despite their affinity for the same ligand, the four adenosine receptors are paired with distinct second messenger pathways, which promote a diverse array of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory phenotypes across tissues. The abundance and selectivity of these receptors are a major factor in mediating the downstream consequences of adenosine signaling (Figure 1B). The low affinity receptors A1 and A3 can be coupled to Gi, Go or Gq proteins, resulting in decreased cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and increased calcium ions. The A1 receptor is associated with both anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory effects. In the peripheral nervous system, adenosine binding to the A1 receptor can elicit analgesic effects in neuroinflammation. Conversely, in innate immune cells and solid organs chronic adenosine exposure mediates proinflammatory effects upon A1 receptor binding (i.e. bronchoconstriction in the lung; negative chronotropic effects in the heart atria; reduced insulin secretion in the pancreas; and reduced blood flow and renin release in the kidneys) (Borea et al., 2018; Le et al., 2019). The A3 receptor largely mediates anti-inflammatory effects in mucosal sites and immune cells (Borea et al., 2018). Analogously, the A2A and A2B receptors, which are high affinity receptors can be coupled to either Gs or Gq, resulting in increased cAMP levels. These serve primarily the role of inflammatory suppressors (Borea et al., 2018). These receptors are highly concentrated on innate and adaptive immune cells for their regulation. Among the two, only the A2B subtype has been linked to some pro-inflammatory outcomes. In the intestine and lung, adenosine binding to the A2B receptor contributed to inflammation in hypoxia. In microglia, A2B binding increased IL-6 production and hypersensitive nociception (Hu et al., 2016; Merighi et al., 2017; Bowser et al., 2018; Le et al., 2019).

Adenosine has potent immunoregulatory effects on inflamed tissues. Upon infection or injury, adenosine is synthesized to prevent excessive damage caused by effector cells of innate and adaptive origin. In monocytes, adenosine reduces inflammation through the activation of A2A, A2B, A3 receptors by modulating cytokine secretion, DNA binding and intracellular signaling pathways (Figure 1B). Adenosine restricts the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-12, TNFα, NO and MIP1α from macrophages and specifically promotes the conversion of M1 monocytes to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype (Ferrante et al., 2013). Intracellularly, it interferes with Akt signaling in monocytes by inhibiting IκB-α degradation, thus preventing NF-κB DNA binding and stimulating the anti-inflammatory IL-10-induced STAT3 signaling (Lee et al., 2011; Koscsó et al., 2013). High concentrations of adenosine occur in response to active inflammatory processes, which demand continuous supply of anti-inflammatory agents for their regulation. Indeed, the cAMP/CREB second messenger pathway, activated upon A2A and A2B binding, transcriptionally regulates CD39 expression, suggesting a positive feedback loop for adenosine synthesis. The increased adenosine concentration prolongs TLR inhibition and solidifies the M2 phenotype characterized by a decrease in glycolytic rate. In the context of bacterial infection, high adenosine concentrations inhibit macrophage phagocytosis, thus promoting colonization (Frasson et al., 2017).

Purinergic signaling affects neutrophils by both promoting their antibacterial functions, as well as by attenuating chemotaxis and adhesion (Figure 1B). Specifically, stimulation of the A1 receptor on neutrophils results in increased phagocytosis and reactive oxygen species production which contributes to their proinflammatory nature. In contrast, both adenosine and A2B receptor agonists inhibit P-selectin/β2 integrin-mediated neutrophil rolling, as well as the activation of SFKs and Vav guanine-nucleotide exchange proteins, which mediate neutrophil cytoskeletal rearrangement (Yago et al., 2015). These effects on neutrophil function limit the intensity of proinflammatory responses to injury and pathogens. Indeed, phagocytosis and ROS secretion are reduced upon A2B activation in neutrophils responding to bacterial infection (Frasson et al., 2017).

The impact of adenosine signaling in the pathogenesis of infection has been studied with a variety of pathogens and model systems yielding differing results. While adenosine is important to prevent tissue damage, it can contribute to bacterial pathogenesis by disrupting immune defenses. Inflammation in LPS-challenged tissues, such as the lung and vasculature, stimulates the protective release of adenosine to halt the damage induced by monocytes and granulocytes (Gonzales et al., 2014; Kutryb-Zajac et al., 2019). In this setting, pathogens can exploit the anti-inflammatory effects of adenosine on the innate and adaptive immune response (Figure 1B).

In a model of Myobacterium tuberculosis infection in CD73 deficient mice, which are severely restricted in their extracellular adenosine synthesis, bacterial clearance is enhanced (Petit-Jentreau et al., 2015). Of note, this effect was not dependent upon macrophage CD73 activity, as in vitro incubation with ATP and bacteria did not affect their function. Instead, in these mice M. tuberculosis infection led to increased TNFα, IL-6 and KC levels along with higher numbers of polymorphonuclear neutrophils in mouse lungs, which enhance clearance (Petit-Jentreau et al., 2015). These results illustrate the complexity of the adenosine-receptor interaction depending upon the specific immune cells involved in host defense.

In the pathogenesis of K. pneumoniae respiratory infection, adenosine binds to A2B receptors on neutrophils inhibiting phagocytic clearance and decreasing killing (Barletta et al., 2012). By disrupting the ligand-receptor interaction, A2B deficient mice were found to have improved clearance of K. pneumoniae compared to WT mice. Additional studies indicate that in WT mice adenosine binding prevents extracellular DNA accumulation and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation. These NETs are outgrowths of neutrophils, containing histones and DNA which contribute to bacterial capture and clearance (Barletta et al., 2012). The reduced NETosis mediated by adenosine signaling in the WT host benefits K. pneumoniae survival.

The Gram positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus exploits adenosine accumulation through several mechanisms. S. aureus expresses a surface protein adenosine synthase A (AdsA) that generates adenosine from ATP, ADP and deoxyadenosine, as well as the cytotoxic deoxyguanosine (Winstel et al., 2018; Tantawy et al., 2022). In a model of renal abscess and septicemia, the resulting NETosis provides S. aureus with a source of DNA and nucleosides for adenosine synthesis. The released adenosine then induces caspase-3-dependent macrophage apoptosis (Thammavongsa et al., 2009; Thammavongsa et al., 2011), furthering S. aureus proliferation. An additional response promoting S. aureus survival is blocking the activation of type IIA secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2-IIA) (Pernet et al., 2015). S. aureus generation of adenosine via AdsA enables the organism to escape sPLA2-IIA-mediated killing by impairing macrophage phagocytosis. In these model systems, S. aureus successfully escapes innate immune responses by contributing to the adenosine pool and preventing macrophage killing (Winstel et al., 2018). AdsA-generated adenosine also restrains protective Th1 and Th17 responses demonstrated in a model of intraperitoneal infection. In this situation adenosine reduces caspase-1-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion (Deng et al., 2021).

Besides phagocytes, other classes of immune cells participate in adenosine – mediated immune function in infection. The specialized adaptive sub-lineages of Regulatory T and B lymphocytes, which possess CD39/CD73 ectonucleotidase complexes, suppress effector cells by generating adenosine (Antonioli et al., 2013). Sepsis-survival models of Legionella pneumophila infection exhibited increased CD39-expressing B cells, elevated extracellular adenosine and impaired bacterial killing (Nascimento et al., 2021). In this model, adenosine-mediated inhibition of splenic macrophages relied on both CD39, for adenosine synthesis, and A2A for adenosine binding. In CD39 deficient (Ent-/-) mice or with the blockade or deletion of A2A there was both reduced bacterial burden and enhanced host resistance to L. pneumophila in spleen and lung (Nascimento et al., 2021).

In vivo studies of adenosine and ATP in the response to infection reflect considerable variability depending upon both the pathogen and the infected tissue. In the lung, injections of adenosine or ATP prior to or 3-hours-post-intratracheal inoculation with Escherichia coli protected the host from infection and stimulated proinflammatory recruitment (Gross et al., 2020). These protective effects are similar to the phenotype observed with Streptococcus pneumoniae infections, in which adenosine and ATP through the A1 receptor prevent pathogen adhesion to pulmonary epithelial cells (Bhalla et al., 2020). ATP release is a damage associated molecular pattern (DAMP), a signal of host damage to which the innate immune system promptly responds. However, in a systemic model of E. coli infection, LPS-induced ATP release served as substrate for adenosine synthesis, resulting in diminished proinflammatory recruitment and successful establishment of infection (Kondo et al., 2019). These results suggest that the anti-inflammatory effects of adenosine may be deleterious for the host, and enable bacterial infection in specific tissues.

One of the major explanations for the varied responses to adenosine in different bacterial infections is the ability of some pathogens to utilize it as a carbon and nitrogen source (Matsumoto et al., 1978). These metabolic degradative pathways are differentially expressed in specific organisms and their impact is not appreciated in studies using LPS as a surrogate for Gram negative bacteria. As a suitable nitrogen reservoir, adenine is generated through a network of purinergic enzymes in P. aeruginosa, which possesses enzymes for both inosine and adenosine monophosphate (IMP, AMP) synthesis (purA-D), as well as adenosine deamination and adenosine and inosine degradation (nuh, add) (Figure 1A) (Heurlier et al., 2005; Goble et al., 2011). In P. aeruginosa, the major quorum sensing regulator LasR modulates genes nuh and add, which are determinants of successful growth on adenosine and inosine (Heurlier et al., 2005). Thus, beyond its immunomodulatory effects, excess adenosine at infected host sites can promote pathogen growth. Indeed, profiling of P. aeruginosa clinical strains indicated that biofilm-forming isolates preferred amino acids such as L-threonine and L-serine, while non-biofilm-forming isolates utilized adenosine and inosine to proliferate (Ismail et al., 2020).

K. pneumonia readily metabolizes purines and utilizes the adenosine product hypoxanthine as a nitrogen source (de la Riva et al., 2008). To initiate this process, the phosphorylated nitrogen regulator NtrC-P binds to an enhancer activating the hpx gene cluster, associated with oxidation of nitrogenous compounds, specifically hypoxanthine and uric acid (Figure 1A) (de la Riva et al., 2008). During infection, one of the greatest stressors for pathogens is scarcity of preferred nutrients. The hpxDE operon system is activated in response to nitrogen limitation and to the presence of available purinergic compounds (de la Riva et al., 2008). The evolution of NMT1 motif xanthine riboswitches and adenosine deaminases (tada) to prevent purine toxicity is a known adaptive function of K. pneumoniae (Guzmán et al., 2011; Yu and Breaker, 2020). Exposure to adenosine precursors such as IMP enhances its hypermucoviscosity and production of capsular polysaccharide (CPS), both associated with infection of the alveolar epithelium (Mike et al., 2021). The ability to hydrolyze and synthesize purines has been associated with the intracellular persistence of both classical and hypervirulent strains of K. pneumoniae in lung infection (Bachman et al., 2015; Bruchmann et al., 2021). Mutations in the cytoplasmic protein adenylosuccinate synthase (purA) prevented K. pneumoniae from repurposing intracellular nucleosides for CPS biosynthesis and exhibited growth defects along with mutants purF, purL and purH (Mike et al., 2021). The release of ATP and its function as a host innate immune signal also fuels the adaptation of these common pathogens to the site of infection.

While adenosine catabolism is a shared property of several bacterial species, its metabolic cost is still poorly understood. In vitro and in vivo studies of Salmonella enterica in intestinal epithelial cells describe reduced bacterial colonization upon adenosine exposure due to inhibition of pathogen growth. S. enterica express the adenosine-converting enzymes adenosine deaminase (add) and purine nucleoside phosphorylase (deoD), which convert adenosine to inosine and adenine, respectively (Figure 1A) (Kao et al., 2017). While S. enterica enzymatic activity promoted bacteriostatic conditions when incubated with adenosine in vitro, deoD and add deficient strains were able to reach exponential growth (Kao et al., 2017). The selective pressure exerted by adenosine on S. enterica discourages its consumption and suppresses virulence. Similarly, in CD73 deficient mice lacking adenosine accumulation, there is increased transepithelial migration of the pathogen compared to WT mice, suggesting that adenosine has important protective effects on the host to the detriment of S. enterica (Kao et al., 2017).

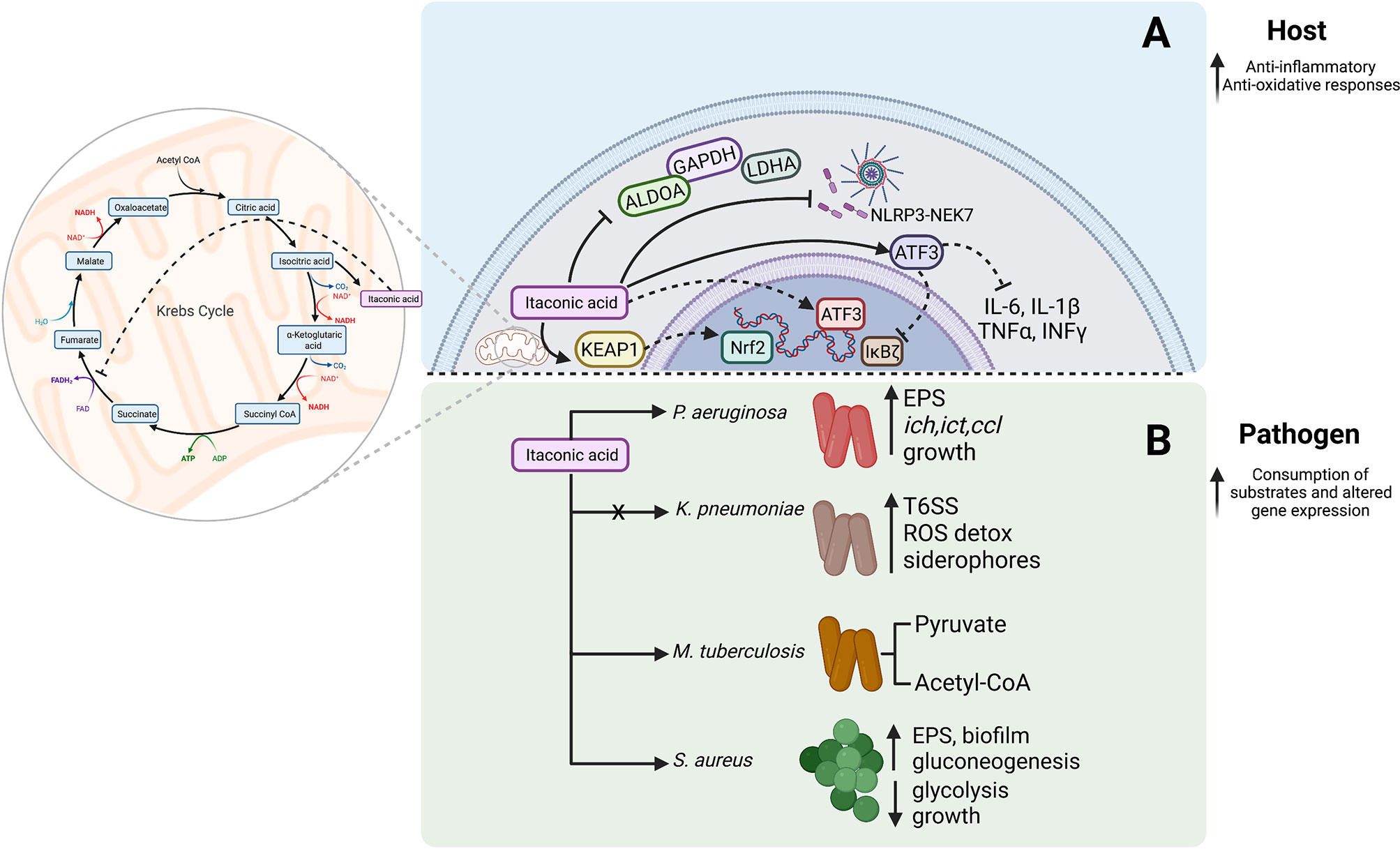

Itaconate is among the most abundant metabolites produced by macrophages. It is a TCA metabolite derived from the conversion of an intermediate of cis-aconitate by cis-aconitate decarboxylase (CAD), also known as aconitate decarboxylase 1 (ACOD1) or immunoregulatory gene 1 (IRG1) (Michelucci et al., 2013). Itaconate interrupts the TCA cycle in mitochondria at the enzymatic level of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) (Figure 2) (Cordes et al., 2016; Lampropoulou et al., 2016). The inhibition of complex-II oxidation is mediated by the structural similarity between itaconate and succinate, where itaconate accumulation is translated to a negative feedback signal (Lampropoulou et al., 2016). Upon loss of irg1, myeloid reliance on respiration in cell culture is restored potentially through anaplerosis and a functional succinate-Q oxidoreductase. In the context of infection, itaconate reduces the TLR-triggered secretion of inflammatory cytokines (Li et al., 2013). Specifically, in mouse models of pneumonia, itaconate was identified as a common molecule in the airway metabolome contributing to bacterial pathogenesis (Riquelme et al., 2020; Tomlinson et al., 2021; Wong Fok Lung et al., 2022).

Figure 2 Itaconate effects on host signaling and bacterial survival. (A) Itaconate targets host signaling and suppresses inflammation. (B) Itaconate fuels bacterial metabolism and adaptation.

The biochemical properties of itaconate contribute to the anti-inflammatory profile of macrophages (Figure 2A) (Strelko et al., 2011). The use of proteomic screens indicated that itaconate-mediated chemical alteration of cytosolic targets KEAP1, ATF3, NF-κB, and cysteine modifications in NLRP3 and glycolytic enzymes could be responsible for the immune effects that were observed. The unsaturated dicarboxylic acid structure of itaconate renders it slightly electrophilic and mediates an interaction with thiol functional groups through 2, 3-dicarboxypropylation in the cytosol (Hooftman et al., 2020; Peace and O’Neill, 2022). Itaconate has anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties that have been partly ascribed to itaconate-induced KEAP1 protein alkylation. This modification boosts Nrf2 and glutathione levels in myeloid cells promoting an anti-inflammatory phenotype (Mills et al., 2018). ATF3 is also targeted by itaconate, altering the inflammatory profile of macrophages by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokine release (IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, INFγ). ATF3 can be upregulated by exogenous and endogenous itaconate, which interferes with the NF-κB inhibitor zeta (IκBζ) axis thus reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (Bambouskova et al., 2018). This phenotype reversed in the atf3-knockout or irg1-knockout cell line which remained proinflammatory (Bambouskova et al., 2018).

Itaconate is also involved in amino acid modifications (Figure 2A). The itaconate-induced Cys548 modification interferes with the NLRP3-NEK7 interaction, inhibiting inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion in macrophages, thus promoting an anti-inflammatory phenotype (Hooftman et al., 2020). Additional targets for cysteine modifications include key glycolytic enzymes such as GAPDH, aldolase (ALDOA) and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), of which ALDOA holds the most upstream position converting β-D-fructose-1,6-phosphate to D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate (Qin et al., 2019). Among the targets Cys339 was found to be a functional residue leading to the instability of the protein after the itaconate modification. Overall, a substantial body of evidence in diverse systems confirms a role for itaconate as a major metabolic regulator of glycolysis and as such could be important in host immune responses and disease tolerance (Domínguez-Andrés et al., 2019; Qin et al., 2019)

Itaconate is a host-generated metabolite, initially thought to function as an antimicrobial agent due to its effects on isocitrate lyase-mediated glyoxylate shunt inhibition (McFadden et al., 1971; McFadden and Purohit, 1977; Nair et al., 2018). However, opportunistic pathogens exhibit diverse metabolic and transcriptional alterations in response to increased itaconate levels which extend beyond mammalian immunity. Accumulating evidence indicates that itaconate has major effects on both bacterial metabolic activity as well as the host immune function. For example, in specific disease settings, such as cystic fibrosis, limited activity of the phosphatase and tensin (PTEN) protein results in the accumulation of both succinate and itaconate in the airway which have profound effects on bacterial metabolism as well as on the host inflammatory response to infection (Riquelme et al., 2017).

Just as many Gram negative bacteria are able to utilize adenosine released by the host, P. aeruginosa clinical isolates catabolize itaconate via three devoted genes (ict, ich, and ccl) expressed to use itaconate as a major carbon source (Figure 2B) (Riquelme et al., 2020). In comparison to the laboratory strain PAO1, growth of P. aeruginosa clinical isolates is significantly boosted in irg1-competent mice compared to Irg1-/-, where adapted strains exhibit increased proficiency in establishing infection (Riquelme et al., 2020). In addition to using itaconate as a carbon source, this dicarboxylate also drives major adaptive changes in P. aeruginosa metabolism. Exposure to itaconate results in increased utilization of the Entner-Doudroff pathway and the glyoxylate shunt, fueling pathways that lead to increased production of extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) and decreased display of LPS (Riquelme et al., 2019; Riquelme et al., 2020). Such host adapted strains respond to itaconate with the upregulation of EPS genes such as algT, algA, algD, algQ and mucA (Riquelme et al., 2020) which promote biofilm formation. This lifestyle provides defense against antibiotics, antimicrobial peptides, oxidants and phagocytosis enhancing bacterial persistence. Furthermore, EPS itself stimulates myeloid cells to release additional itaconate, which is then exploited by P. aeruginosa as a carbon source (Riquelme et al., 2020).

Itaconate metabolism is also an important factor holding a multidimensional role in the success of the airway pathogens Aspergillus terreus and Myobacterium tuberculosis (Bonnarme et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2019). Itaconate was first identified as an inhibitor of methylmelonyl-CoA mutase in vitro preventing M. tuberculosis growth on permissive media (Ruetz et al., 2019). However, M. tuberculosis can also generate itaconyl-CoA, which is hydrated to form (S)-citramalyl-CoA and lysed into pyruvate and acetyl-CoA through Rv2498c, a stereospecific bifunctional β-hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase (Figure 2B). Through this common mechanism, M. tuberculosis and A. terreus are able to resist growth inhibition and itaconate toxicity, and proliferate by utilizing the generated byproducts (Sasikaran et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). Thus, itaconate, like adenosine, may promote infection by supporting bacterial proliferation and by suppressing immune activation.

Even organisms that do not metabolize itaconate can benefit from its presence by altering their own metabolic activity to thwart immune clearance. The expression of Irg1 by myeloid cells is also a major component of the anti-inflammatory milieu leading to infection tolerance (Wong Fok Lung et al., 2022). Metabolically active K. pneumoniae ST258 strains induce ROS-generating pathways, myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSCs) recruitment, and abundant itaconate release in the airway (Ahn et al., 2016; Wong Fok Lung et al., 2022). Itaconate helps to control K. pneumoniae infection, as there is a significantly increased bacterial burden in Irg1-/–mice (Wong Fok Lung et al., 2022). However, the presence of itaconate enables the infected mice to tolerate remarkably high levels of infection (Wong Fok Lung et al., 2022). Bulk RNA-sequencing of K. pneumoniae infected Irg1-/–lung reflects how itaconate creates a milieu that enables infection tolerance. In the Irg1-/- mice ST258 K. pneumoniae organisms increase the expression of glutathione-mediated ROS detoxification (peroxidases, S-transferases, gsiD, soxR, aphA), siderophore production (entS, fepA/D/G, fes), and type six secretion system (T6SS) gene transcription, reflecting the excess oxidant stress that is normally controlled by itaconate (Figure 2B) (Wong Fok Lung et al., 2022).

The Gram positive S. aureus cannot utilize itaconate as a carbon source. Exposure to itaconate imposes metabolic stress by suppressing aldolase activity and interfering with glycolysis, the preferred metabolic pathway in S. aureus (Tomlinson et al., 2021). Gluconeogenesis is upregulated in response to itaconate exposure which promotes the selection of strains shunting carbohydrates in EPS and biofilm (Figure 2, Pathogen) (Tomlinson et al., 2021). Thus, itaconate promotes a metabolic phenotype in S. aureus favoring persistent infection.

We have briefly highlighted some of the major consequences of two abundant immunometabolites, adenosine and itaconate, in the pathogenesis of bacterial infection (Figures 1 and 2). We illustrate how anti-inflammatory metabolites may have both beneficial and negative consequences on host health. Suppressing inflammation through both itaconate and adenosine is permissive of neoplastic diseases (Weiss et al., 2018; Churov and Zhulai, 2021). We learn from oncology that the efforts to interfere with tumor metabolism can be therapeutic and strategies modulating immune cell metabolic activity are being pursued (Stine et al., 2022).

Therapeutic approaches independently targeting host or bacterial gene products have been largely unsuccessful likely due to bacterial metabolic adaptation to the selective pressures imposed during infection (Opoku-Temeng et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021; Jahantigh et al., 2022). It is increasingly evident that upon infection, metabolically active bacteria rapidly alter gene expression and survival strategies (Wong Fok Lung et al., 2022). To prevent bacterial persistence, we could similarly identify conserved metabolic targets, such as the anti-oxidant and protective glyoxylate shunt, or catabolic targets, permitting substrate consumption. Anti-inflammatory metabolites and existing pharmacological agents could be combined to mitigate host damage and reduce bacterial colonization, as recently indicated in S. aureus bacterial pneumonia and endopthalamitis (Liu et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2021). A similar strategy has been shown in an in vitro model of P. aeruginosa treated with a combination of itaconic acid and tobramycin to penetrate biofilm (Ho et al., 2020). In this era of precision medicine, it should be possible to identify the antimicrobial susceptibility of infecting organisms along with critical metabolic pathways mediating their survival in vivo. As a step towards improving our understanding of persistent bacterial infection, it is necessary to simultaneously investigate both host and pathogen in their metabolic interactions, and how they shape the immune response and bacterial metabolic adaptation.

AU and AP conceived the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

NSF (AU) - DGE 2036197. NIH (ASP) - 5R35HL135800-06.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Diagrams present in this manuscript have been created and licensed on BioRender.

Ahn, D., Peñaloza, H., Wang, Z., Wickersham, M., Parker, D., Patel, P., et al (2016). Acquired Resistance to Innate Immune Clearance Promotes Klebsiella Pneumoniae ST258 Pulmonary Infection. JCI Insight 1 (17), e89704. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89704

Antonioli, L., Pacher, P., Vizi, E. S., Haskó, G. (2013). CD39 and CD73 in Immunity and Inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 19, 355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.03.005

Bachman, M. A., Breen, P., Deornellas, V., Mu, Q., Zhao, L., Wu, W., et al (2015). Genome-Wide Identification of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Fitness Genes During Lung Infection. mBio 6 (3), e00775. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00775-15

Bambouskova, M., Gorvel, L., Lampropoulou, V., Sergushichev, A., Loginicheva, E., Johnson, K., et al (2018). Electrophilic Properties of Itaconate and Derivatives Regulate the Iκbζ–ATF3 Inflammatory Axis. Nature 556, 501–504. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0052-z

Barletta, K. E., Cagnina, R. E., Burdick, M. D., Linden, J., Mehrad, B. (2012). Adenosine A 2b Receptor Deficiency Promotes Host Defenses Against Gram-Negative Bacterial Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 186, 1044–1050. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0622OC

Bhalla, M., Hui Yeoh, J., Lamneck, C., Herring, S. E., Tchalla, E. Y. I., Heinzinger, L. R., et al (2020). A1 Adenosine Receptor Signaling Reduces Streptococcus Pneumoniae Adherence to Pulmonary Epithelial Cells by Targeting Expression of Platelet-Activating Factor Receptor. Cell. Microbiol. 22 (2), e13141. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13141

Bonnarme, P., Gillet, B., Sepulchre, A. M., Role, C., Beloeil, J. C., Ducrocq, C. (1995). Itaconate Biosynthesis in Aspergillus Terreus. J. Bacteriol. 177, 3573–3578. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3573-3578.1995

Borea, P. A., Gessi, S., Merighi, S., Vincenzi, F., Varani, K. (2018). Pharmacology of Adenosine Receptors: The State of the Art. Physiol. Rev. 98, 1591–1625. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2017

Bowser, J. L., Phan, L. H., Eltzschig, H. K. (2018). The Hypoxia–Adenosine Link During Intestinal Inflammation. J. Immunol. 200, 897–907. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701414

Bruchmann, S., Feltwell, T., Parkhill, J., Short, F. L. (2021). Identifying Virulence Determinants of Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Galleria Mellonella. Pathog. Dis. 79 (3), ftab009. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftab009

Chen, M., Huang, X., Zhong, C., Li, J., Lu, X. (2016). Identification of an Itaconic Acid Degrading Pathway in Itaconic Acid Producing Aspergillus Terreus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 7541–7548. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7554-0

Churov, A., Zhulai, G. (2021). Targeting Adenosine and Regulatory T Cells in Cancer Immunotherapy. Hum. Immunol. 82, 270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2020.12.005

Cordes, T., Wallace, M., Michelucci, A., Divakaruni, A. S., Sapcariu, S. C., Sousa, C., et al (2016). Immunoresponsive Gene 1 and Itaconate Inhibit Succinate Dehydrogenase to Modulate Intracellular Succinate Levels. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 14274–14284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.685792

Dal Ben, D., Antonioli, L., Lambertucci, C., Fornai, M., Blandizzi, C., Volpini, R. (2018). Purinergic Ligands as Potential Therapeutic Tools for the Treatment of Inflammation-Related Intestinal Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 9. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00212

de la Riva, L., Badia, J., Aguilar, J., Bender, R. A., Baldoma, L. (2008). The Hpx Genetic System for Hypoxanthine Assimilation as a Nitrogen Source in Klebsiella Pneumoniae : Gene Organization and Transcriptional Regulation. J. Bacteriol. 190, 7892–7903. doi: 10.1128/JB.01022-08

Deng, J., Zhang, B., Chu, H., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Gong, H.-R., et al (2021). Adenosine Synthase A Contributes to Recurrent Staphylococcus Aureus Infection by Dampening Protective Immunity. EBioMedicine 70, 103505. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103505

Domínguez-Andrés, J., Novakovic, B., Li, Y., Scicluna, B. P., Gresnigt, M. S., Arts, R. J. W., et al (2019). The Itaconate Pathway Is a Central Regulatory Node Linking Innate Immune Tolerance and Trained Immunity. Cell Metab. 29, 211–220.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.09.003

Ferrante, C. J., Pinhal-Enfield, G., Elson, G., Cronstein, B. N., Hasko, G., Outram, S., et al (2013). The Adenosine-Dependent Angiogenic Switch of Macrophages to an M2-Like Phenotype is Independent of Interleukin-4 Receptor Alpha (IL-4rα) Signaling. Inflammation 36, 921–931. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9621-3

Ferretti, E., Horenstein, A. L., Canzonetta, C., Costa, F., Morandi, F. (2019). Canonical and non-Canonical Adenosinergic Pathways. Immunol. Lett. 205, 25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2018.03.007

Frasson, A. P., Menezes, C. B., Goelzer, G. K., Gnoatto, S. C. B., Garcia, S. C., Tasca, T. (2017). Adenosine Reduces Reactive Oxygen Species and Interleukin-8 Production by Trichomonas Vaginalis-Stimulated Neutrophils. Purinergic Signal. 13, 569–577. doi: 10.1007/s11302-017-9584-1

Goble, A. M., Zhang, Z., Sauder, J. M., Burley, S. K., Swaminathan, S., Raushel, F. M. (2011). Pa0148 From Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Catalyzes the Deamination of Adenine. Biochemistry 50, 6589–6597. doi: 10.1021/bi200868u

Gonzales, J. N., Gorshkov, B., Varn, M. N., Zemskova, M. A., Zemskov, E. A., Sridhar, S., et al (2014). Protective Effect of Adenosine Receptors Against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 306, L497–L507. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00086.2013

Gross, C. M., Kovacs-Kasa, A., Meadows, M. L., Cherian-Shaw, M., Fulton, D. J., Verin, A. D. (2020). Adenosine and Atpγs Protect Against Bacterial Pneumonia-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Sci. Rep. 10, 18078. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75224-0

Guzmán, K., Badia, J., Giménez, R., Aguilar, J., Baldoma, L. (2011). Transcriptional Regulation of the Gene Cluster Encoding Allantoinase and Guanine Deaminase in Klebsiella Pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 193, 2197–2207. doi: 10.1128/JB.01450-10

Heurlier, K., Deínervaud, V., Haenni, M., Guy, L., Krishnapillai, V., Haas, D. (2005). Quorum-Sensing-Negative ( lasR ) Mutants of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Avoid Cell Lysis and Death. J. Bacteriol. 187, 4875–4883. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4875-4883.2005

Ho, D.-K., de Rossi, C., Loretz, B., Murgia, X., Lehr, C.-M. (2020). Itaconic Acid Increases the Efficacy of Tobramycin Against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms. Pharmaceutics 12, 691. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12080691

Hooftman, A., Angiari, S., Hester, S., Corcoran, S. E., Runtsch, M. C., Ling, C., et al (2020). The Immunomodulatory Metabolite Itaconate Modifies NLRP3 and Inhibits Inflammasome Activation. Cell Metab. 32, 468–478.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.016

Hu, X., Adebiyi, M. G., Luo, J., Sun, K., Le, T.-T. T., Zhang, Y., et al (2016). Sustained Elevated Adenosine via ADORA2B Promotes Chronic Pain Through Neuro-Immune Interaction. Cell Rep. 16, 106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.080

Ismail, N. S., Subbiah, S. K., Taib, N. M. (2020). Application of Phenotype Microarray for Profiling Carbon Sources Utilization Between Biofilm and Non-Biofilm of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa From Clinical Isolates. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 21, 1539–1550. doi: 10.2174/1389201021666200629145217

Jahantigh, H. R., Faezi, S., Habibi, M., Mahdavi, M., Stufano, A., Lovreglio, P., et al (2022). The Candidate Antigens to Achieving an Effective Vaccine Against Staphylococcus Aureus. Vaccines (Basel) 10, 199. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020199

Kaczmarek, E., Koziak, K., Sévigny, J., Siegel, J. B., Anrather, J., Beaudoin, A. R., et al (1996). Identification and Characterization of CD39/Vascular ATP Diphosphohydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33116–33122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33116

Kao, D. J., Saeedi, B. J., Kitzenberg, D., Burney, K. M., Dobrinskikh, E., Battista, K. D., et al (2017). Intestinal Epithelial Ecto-5′-Nucleotidase (CD73) Regulates Intestinal Colonization and Infection by Nontyphoidal Salmonella. Infect. Immun. 85 (10), e01022–16. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01022-16

Kondo, Y., Ledderose, C., Slubowski, C. J., Fakhari, M., Sumi, Y., Sueyoshi, K., et al (2019). Frontline Science: Escherichia Coli Use LPS as Decoy to Impair Neutrophil Chemotaxis and Defeat Antimicrobial Host Defense. J. Leukoc. Biol. 106, 1211–1219. doi: 10.1002/JLB.4HI0319-109R

Koscsó, B., Csóka, B., Kókai, E., Németh, Z. H., Pacher, P., Virág, L., et al (2013). Adenosine Augments IL-10-Induced STAT3 Signaling in M2c Macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 94, 1309–1315. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0113043

Kutryb-Zajac, B., Mierzejewska, P., Sucajtys-Szulc, E., Bulinska, A., Zabielska, M. A., Jablonska, P., et al (2019). Inhibition of LPS-Stimulated Ecto-Adenosine Deaminase Attenuates Endothelial Cell Activation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 128, 62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.01.004

Lampropoulou, V., Sergushichev, A., Bambouskova, M., Nair, S., Vincent, E. E., Loginicheva, E., et al (2016). Itaconate Links Inhibition of Succinate Dehydrogenase With Macrophage Metabolic Remodeling and Regulation of Inflammation. Cell Metab. 24, 158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.004

Le, T.-T. T., Berg, N. K., Harting, M. T., Li, X., Eltzschig, H. K., Yuan, X. (2019). Purinergic Signaling in Pulmonary Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 10. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01633

Lee, H.-S., Chung, H.-J., Lee, H. W., Jeong, L. S., Lee, S. K. (2011). Suppression of Inflammation Response by a Novel A3 Adenosine Receptor Agonist Thio-Cl-IB-MECA Through Inhibition of Akt and NF-κb Signaling. Immunobiology 216, 997–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.03.008

Liu, G., Wu, Y., Jin, S., Sun, J., Wan, B.-B., Zhang, J., et al (2021). Itaconate Ameliorates Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus-Induced Acute Lung Injury Through the Nrf2/ARE Pathway. Ann. Trans. Med. 9, 712–712. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-1448

Li, Y., Zhang, P., Wang, C., Han, C., Meng, J., Liu, X., et al (2013). Immune Responsive Gene 1 (IRG1) Promotes Endotoxin Tolerance by Increasing A20 Expression in Macrophages Through Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 16225–16234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454538

Matsumoto, H., Ohta, S., Kobayashi, R., Terawaki, Y. (1978). Chromosomal Location of Genes Participating in the Degradation of Purines in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Mol. Gen. Genet. 167, 165–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00266910

McFadden, B. A., Purohit, S. (1977). Itaconate, an Isocitrate Lyase-Directed Inhibitor in Pseudomonas Indigofera. J. Bacteriol. 131, 136–144. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.1.136-144.1977

McFadden, B. A., Williams, J. O., Roche, T. E. (1971). Mechanism of Action of Isocitrate Lyase From Pseudomonas Indigofera. Biochemistry 10, 1384–1390. doi: 10.1021/bi00784a017

Merighi, S., Bencivenni, S., Vincenzi, F., Varani, K., Borea, P. A., Gessi, S. (2017). A 2B Adenosine Receptors Stimulate IL-6 Production in Primary Murine Microglia Through P38 MAPK Kinase Pathway. Pharmacol. Res. 117, 9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.024

Michelucci, A., Cordes, T., Ghelfi, J., Pailot, A., Reiling, N., Goldmann, O., et al (2013). Immune-Responsive Gene 1 Protein Links Metabolism to Immunity by Catalyzing Itaconic Acid Production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 7820–7825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218599110

Mike, L. A., Stark, A. J., Forsyth, V. S., Vornhagen, J., Smith, S. N., Bachman, M. A., et al (2021). A Systematic Analysis of Hypermucoviscosity and Capsule Reveals Distinct and Overlapping Genes That Impact Klebsiella Pneumoniae Fitness. PloS Pathog. 17, e1009376. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009376

Mills, E. L., Ryan, D. G., Prag, H. A., Dikovskaya, D., Menon, D., Zaslona, Z., et al (2018). Itaconate is an Anti-Inflammatory Metabolite That Activates Nrf2 via Alkylation of KEAP1. Nature 556, 113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature25986

Murray, C. J., Ikuta, K. S., Sharara, F., Swetschinski, L., Robles Aguilar, G., Gray, A., et al (2022). Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0

Nair, S., Huynh, J. P., Lampropoulou, V., Loginicheva, E., Esaulova, E., Gounder, A. P., et al (2018). Irg1 Expression in Myeloid Cells Prevents Immunopathology During M. Tuberculosis Infection. J. Exp. Med. 215, 1035–1045. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180118

Nascimento, D. C., Viacava, P. R., Ferreira, R. G., Damaceno, M. A., Piñeros, A. R., Melo, P. H., et al (2021). Sepsis Expands a CD39+ Plasmablast Population That Promotes Immunosuppression via Adenosine-Mediated Inhibition of Macrophage Antimicrobial Activity. Immunity 54, 2024–2041.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.005

Opoku-Temeng, C., Kobayashi, S. D., DeLeo, F. R. (2019). Klebsiella Pneumoniae Capsule Polysaccharide as a Target for Therapeutics and Vaccines. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 17, 1360–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.09.011

Peace, C. G., O’Neill, L. A. J. (2022). The Role of Itaconate in Host Defense and Inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 132 (2), e148548. doi: 10.1172/JCI148548

Pernet, E., Brunet, J., Guillemot, L., Chignard, M., Touqui, L., Wu, Y. (2015). Staphylococcus Aureus Adenosine Inhibits Spla2-IIA–Mediated Host Killing in the Airways. J. Immunol. 194, 5312–5319. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402665

Petit-Jentreau, L., Jouvion, G., Charles, P., Majlessi, L., Gicquel, B., Tailleux, L. (2015). Ecto-5′-Nucleotidase (CD73) Deficiency in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis-Infected Mice Enhances Neutrophil Recruitment. Infect. Immun. 83, 3666–3674. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00418-15

Qin, W., Qin, K., Zhang, Y., Jia, W., Chen, Y., Cheng, B., et al (2019). S-Glycosylation-Based Cysteine Profiling Reveals Regulation of Glycolysis by Itaconate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 983–991. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0323-5

Riquelme, S. A., Hopkins, B. D., Wolfe, A. L., DiMango, E., Kitur, K., Parsons, R., et al (2017). Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Attaches Tumor Suppressor PTEN to the Membrane and Promotes Anti Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Immunity. Immunity 47, 1169–1181.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.010

Riquelme, S. A., Liimatta, K., Wong Fok Lung, T., Fields, B., Ahn, D., Chen, D., et al (2020). Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Utilizes Host-Derived Itaconate to Redirect Its Metabolism to Promote Biofilm Formation. Cell Metab. 31, 1091–1106.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.017

Riquelme, S. A., Lozano, C., Moustafa, A. M., Liimatta, K., Tomlinson, K. L., Britto, C., et al (2019). CFTR-PTEN–dependent Mitochondrial Metabolic Dysfunction Promotes Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Airway Infection. Sci. Trans. Med. 11 (499), eaav4634. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav4634

Ruetz, M., Campanello, G. C., Purchal, M., Shen, H., McDevitt, L., Gouda, H., et al (2019). Itaconyl-CoA Forms a Stable Biradical in Methylmalonyl-CoA Mutase and Derails its Activity and Repair. Science 366, 589–593. doi: 10.1126/science.aay0934. (1979).

Sasikaran, J., Ziemski, M., Zadora, P. K., Fleig, A., Berg, I. A. (2014). Bacterial Itaconate Degradation Promotes Pathogenicity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 371–377. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1482

Schneider, D. S., Ayres, J. S. (2008). Two Ways to Survive Infection: What Resistance and Tolerance can Teach Us About Treating Infectious Diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 889–895. doi: 10.1038/nri2432

Silva-Vilches, C., Ring, S., Mahnke, K. (2018). ATP and Its Metabolite Adenosine as Regulators of Dendritic Cell Activity. Front. Immunol. 9. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02581

Singh, S., Singh, P. K., Jha, A., Naik, P., Joseph, J., Giri, S., et al (2021). Integrative Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Identifies Itaconate as an Adjunct Therapy to Treat Ocular Bacterial Infection. Cell Rep. Med. 2, 100277. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100277

Stine, Z. E., Schug, Z. T., Salvino, J. M., Dang, C. V. (2022). Targeting Cancer Metabolism in the Era of Precision Oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 141–162. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00339-6

Strelko, C. L., Lu, W., Dufort, F. J., Seyfried, T. N., Chiles, T. C., Rabinowitz, J. D., et al (2011). Itaconic Acid Is a Mammalian Metabolite Induced During Macrophage Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 16386–16389. doi: 10.1021/ja2070889

Tantawy, E., Schwermann, N., Ostermeier, T., Garbe, A., Bähre, H., Vital, M., et al (2022). Staphylococcus Aureus Multiplexes Death-Effector Deoxyribonucleosides to Neutralize Phagocytes. Front. Immunol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.847171

Thammavongsa, V., Kern, J. W., Missiakas, D. M., Schneewind, O. (2009). Staphylococcus Aureus Synthesizes Adenosine to Escape Host Immune Responses. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2417–2427. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090097

Thammavongsa, V., Schneewind, O., Missiakas, D. M. (2011). Enzymatic Properties of Staphylococcus Aureus Adenosine Synthase (AdsA). BMC Biochem. 12, 56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-12-56

Tomlinson, K. L., Lung, T. W. F., Dach, F., Annavajhala, M. K., Gabryszewski, S. J., Groves, R. A., et al (2021). Staphylococcus Aureus Induces an Itaconate-Dominated Immunometabolic Response That Drives Biofilm Formation. Nat. Commun. 12, 1399. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21718-y

Wang, Y., Cheng, X., Wan, C., Wei, J., Gao, C., Zhang, Y., et al (2021). Development of a Chimeric Vaccine Against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Based on the Th17-Stimulating Epitopes of PcrV and AmpC. Front. Immunol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.601601

Wang, H., Fedorov, A. A., Fedorov, E. V., Hunt, D. M., Rodgers, A., Douglas, H. L., et al (2019). An Essential Bifunctional Enzyme in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis for Itaconate Dissimilation and Leucine Catabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 15907–15913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906606116

Weiss, J. M., Davies, L. C., Karwan, M., Ileva, L., Ozaki, M. K., Cheng, R. Y. S., et al (2018). Itaconic Acid Mediates Crosstalk Between Macrophage Metabolism and Peritoneal Tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 3794–3805. doi: 10.1172/JCI99169

Winstel, V., Missiakas, D., Schneewind, O. (2018). Staphylococcus Aureus Targets the Purine Salvage Pathway to Kill Phagocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 6846–6851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805622115

Wong Fok Lung, T., Charytonowicz, D., Beaumont, K. G., Shah, S. S., Sridhar, S. H., Gorrie, C. L., et al (2022). Klebsiella Pneumoniae Induces Host Metabolic Stress That Promotes Tolerance to Pulmonary Infection. Cell Metab. 34 (5), 761–774.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.03.009

Yago, T., Tsukamoto, H., Liu, Z., Wang, Y., Thompson, L. F., McEver, R. P. (2015). Multi-Inhibitory Effects of A 2a Adenosine Receptor Signaling on Neutrophil Adhesion Under Flow. J. Immunol. 195, 3880–3889. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500775

Keywords: adenosine, itaconate, metabolism, anti-inflammatory, bacterial infections, infection tolerance

Citation: Urso A and Prince A (2022) Anti-Inflammatory Metabolites in the Pathogenesis of Bacterial Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12:925746. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.925746

Received: 21 April 2022; Accepted: 23 May 2022;

Published: 15 June 2022.

Edited by:

Thomas Naderer, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Jhih-Hang Jiang, Monash University, AustraliaCopyright © 2022 Urso and Prince. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alice Prince, YXNwN0BjdW1jLmNvbHVtYmlhLmVkdQ==; Andreacarola Urso, YXUyMjExQGN1bWMuY29sdW1iaWEuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.