95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. , 22 July 2022

Sec. Bacteria and Host

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.898794

This article is part of the Research Topic Unconventional Animal Models in Infectious Disease Research - Vol II View all 6 articles

The formation of persister cells is associated with recalcitrance and infections. In this study, we examined the antimicrobial property of alpha mangostin, a natural xanthone molecule, against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) persisters and biofilm. The MIC of alpha mangostin against MRSA persisters was 2 µg/ml, and activity was mediated by causing membrane permeabilization within 30 min of exposure. The membrane activity of alpha mangostin was further studied by fast-killing kinetics of MRSA persiste r cells and found that the compound exhibited 99.99% bactericidal activity within 30 min. Furthermore, alpha mangostin disrupted established MRSA biofilms and inhibited bacterial attachment as biofilm formation. Alpha mangostin down-regulated genes associated with the formation of persister cells and biofilms, such as norA, norB, dnaK, groE, and mepR, ranging from 2 to 4-folds. Alpha mangostin at 16 μg/ml was non-toxic (> 95% cell survival) to liver-derived HepG2 and lung-derived A549 cells, similarly. Still, alpha mangostin exhibited 50% cell lysis of human RBC at 16 μg/ml. Interestingly, alpha mangostin was effective in vivo at increasing the survival up to 75% (p<0.0001) of Galleria mellonella larvae infected with MRSA persister for 120 h. In conclusion, we report that alpha mangostin is active against MRSA persisters and biofilms, and these data further our understanding of the antistaphylococcal activity and toxicity of this natural compound.

Staphylococcus aureus is a major human pathogen associated with hospital and community-acquired infections and can cause bacteremia and sepsis (Tong et al., 2015; Poolman and Anderson, 2018). The rise in antibiotic resistance has severely repressed the treatment options for S. aureus infection (Andersson et al., 2021). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is one of the most common drug-resistant bacteria, responsible for over 60% of S. aureus infections in the United States (Okwu et al., 2019). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported more than 90,000 severe cases of MRSA, causing 35,000 deaths each year in the USA (Okwu et al., 2019). Vancomycin is considered the antibiotic of last resort against MRSA. Still, its increased usage has resulted in the emergence of vancomycin-resistant (VRSA) or intermediate S. aureus (VISA) strains (Ahmed and Baptiste, 2018).

In addition to the ongoing drug-resistance issue, a significant setback for the failure of antimicrobial therapy is the formation of bacterial persister cells (Chang et al., 2020). Bacteria adapt to a phenotypic dormant transient state with high antibiotic tolerance (Lechner et al., 2012). Persister cells are not genetically inherited but develop when a small group of bacteria subjected to a lethal concentration of antibiotics withstands the antibiotic exposure (Balaban et al., 2004; Brauner et al., 2016; Peyrusson et al., 2020). S. aureus tends to develop persisters in the stationary phase of growth (Conlon et al., 2015), and persister S. aureus cells tolerate major classes of antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin (DNA replication inhibitor), gentamicin (protein synthesis inhibitor) and vancomycin (cell wall synthesis inhibitor) (Simões et al., 2018).

In a further complex antibiotic tolerant state, S. aureus forms biofilms comprised of bacteria inside an extracellular polymeric substance made of polysaccharides, proteins, and e-DNA (Craft et al., 2019). Standard antibiotic treatments are ineffective against biofilm formed by S. aureus persisters, leading to complexities, including recurrence of severe infections, such as endocarditis and osteomyelitis (Conlon, 2014). Small molecules targeting the bacterial membrane and cell wall provide a promising strategy to overcome the severe concern of S. aureus persister and biofilms (Fisher et al., 2017) and, in previous reports, our group reported that molecules that permeabilize the cell membrane are effective against S. aureus persister and biofilms (Kim et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018a; Kim et al., 2018b).

In this study, we explored the therapeutic potential of alpha mangostin, a natural xanthone molecule from mangostin fruit (Garcinia mangostana) (Koh et al., 2013). While alpha mangostin is known to demonstrate bactericidal activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus (Koh et al., 2013), the potential to target S. aureus persisters and persister regulating gene is unexplored. In this study, we conducted a series of experiments exploring the in vitro and in vivo activity of alpha mangostin against MRSA persisters.

Community-acquired methicillin-resistance S. aureus (CA-MRSA) strain MW2 BAA-170 was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). To isolate persister cells, overnight cultures of S. aureus MW2 (OD600nm) grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (BD) at 37°C were treated with 10X MIC (20 μg/ml) of gentamicin for 4 h as described (Allison et al., 2011).

Unless specified, alpha mangostin and other antimicrobial agents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (MO, USA), and the antibiotics stock solutions were made in DMSO or ddH2O, as indicated.

We performed a standard micro-dilution method (CLSI, 2018) to determine the MIC of alpha mangostin against S. aureus MW2 persister cells (CLSI, 2018). In short, serial dilution (50 μl) of alpha mangostinwere made in 96-well plates (Cat No. 3595, Corning, NY, USA) containing Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB) in triplicates. Then, overnight culture of S. aureus MW2 was grown to stationary phase and treated with 20 μg/ml of gentamicin for 4 h. We washed the bacterial cells thrice using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, we added 50 μl of S. aureus persister cell (1x105 CFU/ml) to wells containing the dilution of alpha mangostin. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 18 h. After incubation, the plate was read spectrophotometrically at OD600 using SpectraMax M3, Molecular Devices (San Jose, CA, USA). The MIC is the drug concentration devoid of any bacterial growth.

We prepared S. aureus MW2 persister cells by adding 20 μg/ml of gentamicin to an overnight bacterial culture and incubating for an additional 4 h (Kim et al., 2015). After incubation, we washed the bacterial cells thrice with an equal volume of PBS and set OD600 ~ 0.4 (~2 x 108CFU/ml). We added 1 ml of S. aureus MW2 persister cells with alpha mangostin (2 μg/ml) and vancomycin (4 μg/ml) inside a 2 ml deep well assay block (Corning Costar 3960). Then, we incubated the plate at 37°C with shaking at 225 rpm. At specific time points (0, 30, 60 and 120 mins), we removed 50 μl of the samples and serially diluted, and spot-plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA, BD) plates enumerating the number of persister cells. All the experiments were done in triplicate.

We performed a fluorescence-based cell membrane permeability assay using the protocol established in (Kim et al., 2015). In brief, we cultured overnight cultures of S. aureus MW2 to stationary phase and treated them with 20 μg/ml of gentamicin for 4 h. After 4 h, we washed the bacteria thrice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and set OD600 ~ 0.4 (~2 x 108 CFU/ml). Then, we added 5 μM of SYTOX Green dye to 10 ml of bacterial cells and incubated the mixture at room temperature for 30 min. In a 96-well plate (Corning catalog no. 3904), we added 50 μl of SYTOX Green/persister cells mixture to50 μl of alpha mangostin (2 μg/ml). Bithionol (2 μg/ml) and vancomycin (4 μg/ml) were used as controls. We measured the fluorescence intensity for 240 min at room temperature using a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M3, Molecular devices) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 525 nm, respectively. All the experiments were done in triplicate.

We performed a checkerboard assay to evaluate the synergy between alpha mangostin and antibiotics (Iluz et al., 2018). In a 96-well microtiter plate, we formed an 8x8 matrix with two-fold serial dilution of alpha mangostin and conventional antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, rifampicin, norfloxacin, gentamicin, and vancomycin). We prepared S. aureus MW2 bacteria as described in the MIC experiments and added them to the corresponding wells. Then incubated, the plates at 37°C for 18 h.

After incubation, we read the plates spectrophotometrically at OD600 using SpectraMax M3, Molecular Devices (San Jose, CA, USA). We calculated the fractional inhibition concentration index (FICI using the formula FICI=MIC of compound A in combination/MIC of compound A alone + MIC of compound B/MIC of compound B alone. The FICI value is categorized by Synergy – FICI < 0.5, additive – 0.5- 4, and antagonism, FICI > 4 (Iluz et al., 2018).

We cultivated an overnight culture of S. aureus MW2 in TSB (supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 3% NaCl) media. In a 96-well plate (Cat No. 3903, Corning, NY, USA), we serially diluted 50 μl of alpha mangostin solution (64 -1 μg/ml). To this plate, we added a high density (1.5 OD600nm) of overnight culture (S. aureus MW2) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation, we discarded the media and washed the wells carefully with PBS to remove any loosely attached or free-floating planktonic cells (Mishra et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2021). We added 20% of XTT to the wells after discarding the planktonic cells and incubated the plate for another 2 h at 37°C. We quantified the inhibition of initial biofilm adhesion using XTT [2,3- bis(2-methyloxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tertazolium-5-carboxanilide following manufacture instructions with minor adjustments (ATCC, VA, USA). We recorded the absorbance at 450 nm using SpectraMax M2 Multi-mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). We calculate the percentage of biofilm growth assuming 100% biofilm attachment is achieved in the bacterial wells without alpha mangostin treatment.

In addition, to quantitate the effect of alpha mangostin on biomass reduction of initial biofilm adhesion, we performed crystal violet (CV) staining. S. aureus initial biofilm adhesion plates were set as described above for the XTT assay. In brief, we incubated the 96-well plates for 1 h at 37°C, discarded the media, and gently washed the wells with phosphate-buffered saline to remove any loosely attached or floating cells. We then added 100 μl of 0.4% CV stain to all the well-containing biofilms and let them stand for 15 min at room temperature. We removed the excess dye by washing twice with sterile water after 15 min. Finally, we added 100 μl of 95% ethanol to dissolve the CV stain and visualized the S. aureus biofilm adhesion (LewisOscar et al., 2017).

We tested the efficacy of alpha mangostin in inhibiting biofilm formation by S. aureus using the assay described in (Mishra et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2021). We cultivated an overnight culture of S. aureus MW2 in TSB (supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 3% NaCl) media. The next day, an exponential phase of bacterial culture was done in the same TSB media and diluted to OD600 ~0.03. In a 96-well plate (Cat No. 3903, Corning, NY, USA), we serially diluted 50 μl of alpha mangostin solution (64 -1 μg/ml). To this plate, we added 50 μl of the bacterial culture and incubated the plate at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, we discarded the media and washed the wells carefully with PBS to remove any loosely attached or free-floating planktonic cells (Mishra et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2021). We added, 20% of XTT to the wells after discarding the planktonic cells and incubated the plate for another 2 h at 37°C. We quantified the inhibition of biofilm formation using XTT [2,3- bis(2-methyloxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tertazolium-5-carboxanilide] following manufacture instructions with minor adjustments (ATCC, VA, USA). We recorded the absorbance at 450 nm using SpectraMax M2 Multi-mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). We calculate the percentage of biofilm growth assuming 100% biofilm attachment is achieved in the bacterial wells without alpha mangostin treatment.

We performed the S. aureus biofilm inhibition assay in the presence of alpha mangostin as described in the initial S. aureus biofilm adhesion section. We incubated the 96-well plates at 37°C for 24 h, discarded the media, and washed the wells carefully with PBS to remove any loosely attached or free-floating cells. We then added 100 μl of 0.4% CV stain to all the well-containing biofilms and left them for 15 min at room temperature. After 15 min, we removed the excess dye by washing twice with sterile water. We added 95% ethanol to the 96-well plates to release the fixed CV stain and visualized the inhibition of S. aureus biofilm formation (LewisOscar et al., 2017).

We cultured overnight culture of S. aureus MW2 in TSB media (supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 3% NaCl). The next day, we cultured an exponential phase of bacterial cells in the same TSB media and diluted to OD600 ~0.03. In a flat bottomed 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate (Cat No. 3903, Corning, NY, USA), we added 100 μl of the adjusted bacterial culture and incubated the plates at 37°C for 24 h in static conditions to allow robust biofilm formation. After incubation, we discarded the media and washed the wells carefully with PBS to remove any loosely attached or free-floating planktonic cells (Mishra et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2021). To the established S.aureus MW2 biofilms in 96-well plates, we added serially diluted alpha mangostin (64 -1 μg/ml) in fresh TSB media and incubated the plates for another 24 h. After discarding the media containing planktonic cells and washing the wells with PBS to remove loosely attached or free-floating cells, we added 20% XTT in TSB media to the established S. aureus MW2 biofilms in 96-well plates. We incubated the plates for another 2 h at 37°C. We performed colorimetric quantification of the disruption of mature biofilm using XTT [2,3- bis(2-methyloxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tertazolium-5-carboxanilide] following manufacture instructions with minor adjustments (ATCC, VA, USA) and measured the absorbance at 450 nm using SpectraMax M2 Multi-mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). The percentage of biofilm growth was plotted, assuming 100% biofilm growth is achieved in the bacterial wells without alpha mangostin treatment.

We pre-formed S. aureus mature biofilm for 24 h and treated the established biofilm with alpha mangostin as mentioned in the initial S. aureus biofilm adhesion section. We incubated the 96-well plates for another 24 h at 37°C, discarded the media, and washed the wells carefully with PBS to remove any loosely attached or free-floating cells. We then added 100 μl of 0.4% CV stain to all the well-containing biofilms and left them for 15 min at room temperature. We removed the excess dye by washing twice with sterile water after 15 min. We added 95% ethanol to the 96-well plates to release the fixed CV stain and visualized the disruption of preformed S. aureus biofilms (LewisOscar et al., 2017).

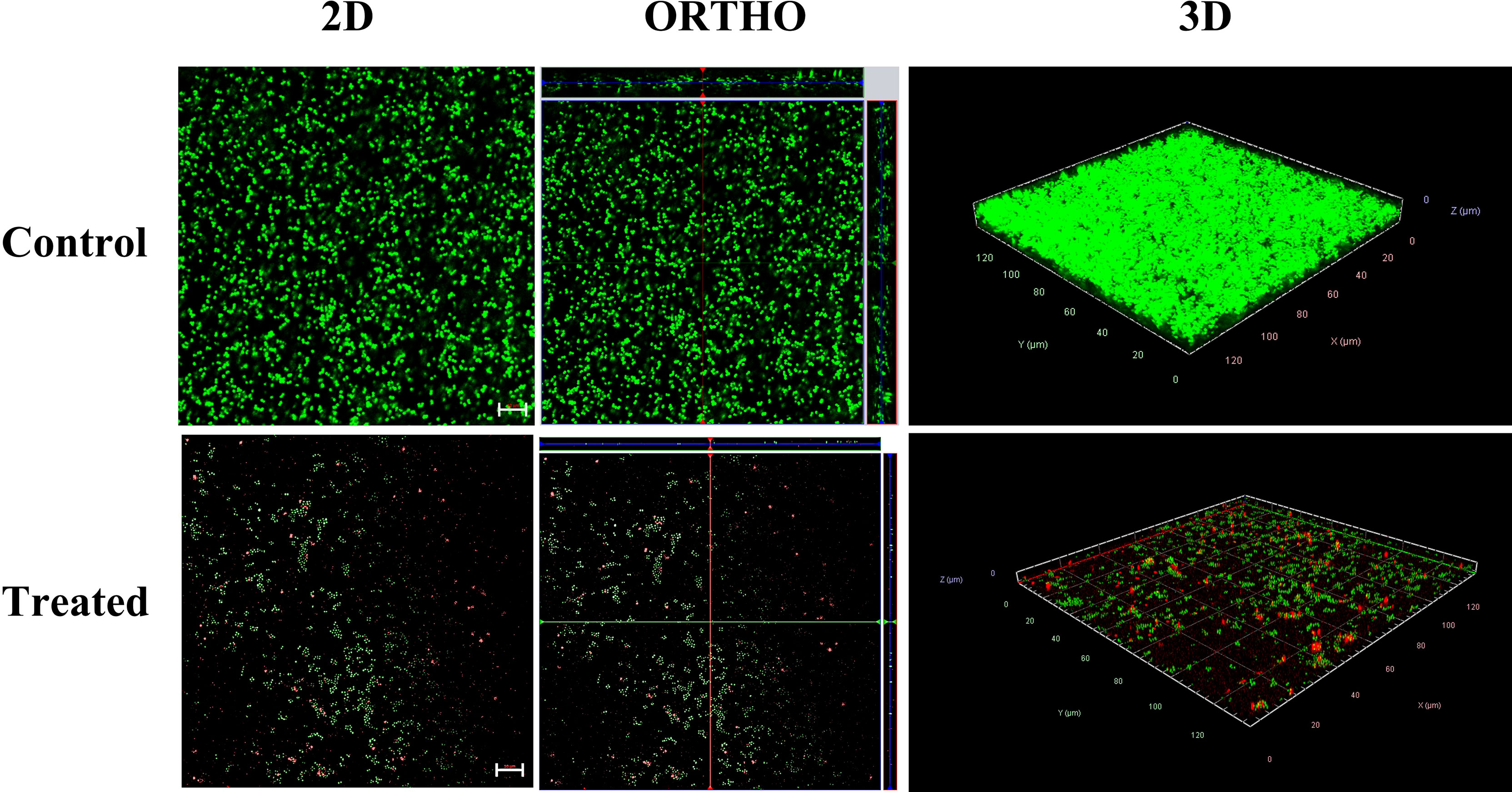

We performed a confocal microscopic analysis of alpha mangostin treated and untreated S. aureus biofilms at two different stages (biofilm formation and established biofilm). To visualize the effect of alpha mangostin on inhibition of biofilm formation, we inoculated 1 ml of exponential phase culture of S. aureus MW2 (106 CFU/ml) in TSB media (supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 3% NaCl) along with alpha mangostin (2 μg/ml final concentration) inside a chamber cuvette (Borosilicate cover glass system, Nunc Cat No:155380). After incubation for 24 h at 37°C, we discarded the media and washed the chambers carefully with PBS to remove any loosely attached or free-floating cells (Mishra et al., 2016). We processed the control biofilm similarly except for the addition of alpha mangostin.

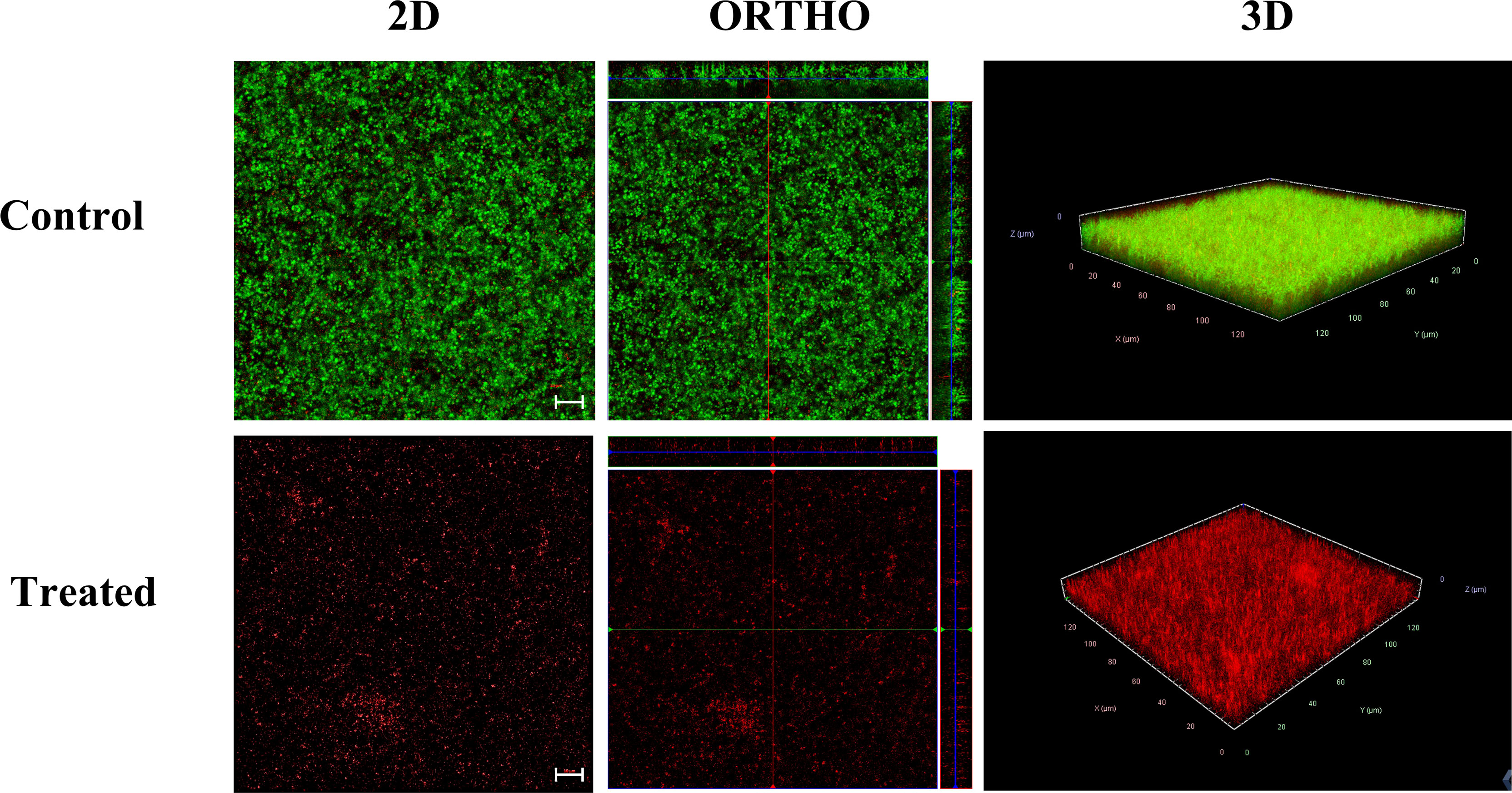

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, we stained S. aureus MW2 biofilms using a LIVE/DEAD staining kit (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, USA). The biofilm was observed using a 63X oil immersion objective (63X/1.2 W) in a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) (Model: Zeiss 880) (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The excitation/emission was set at 555 nm/>550 nm for propidium iodide and 488 nm/<550 nm for SYTO9. The 2D, ortho, and 3D images for 24 and 48 h of alpha mangostin treated and untreated S. aureus MW2 biofilms were acquired using Zen black software (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The acquired Z-stack images were processed using Zen Blue lite software (Carl Zeiss, Germany) (Mishra et al., 2016).

Similarly, to visualize the effect of alpha mangostin on disruption of established biofilms, we inoculated 1 ml of exponential phase culture of S. aureus MW2 (106 CFU/ml) in TSB media (supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 3% NaCl) inside a chamber cuvette (Borosilicate cover glass system, Nunc Cat No:155380). We incubated the chambers for 24 h at 37°C to allow biofilm formation. After incubation, we discarded the media and washed the chambers carefully with PBS to remove any loosely attached or free-floating cells. We added 1 ml fresh TSB to this pre-formed biofilm with 4 μg/ml of alpha mangostin and incubated the cuvette for another 24 h. We processed the control biofilm similarly except for the addition of alpha mangostin. After the incubation, we stained the biofilms like the biofilm formation assay and visualized them under the confocal microscope (Mishra et al., 2016).

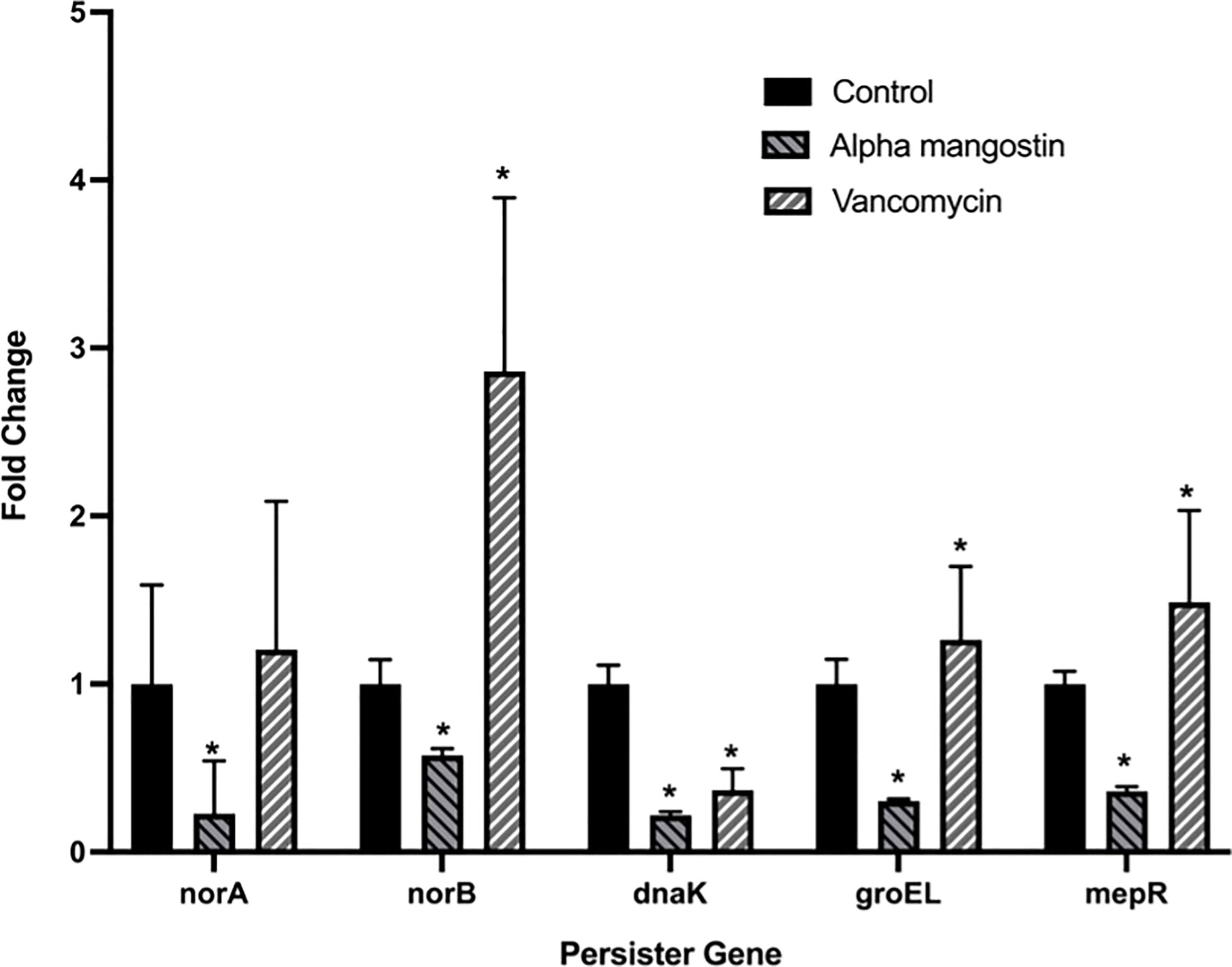

We performed RT-PCR-based transcription to quantitate the impact of alpha mangostin on the MRSA persister genes (Khader et al., 2020). In brief, we prepared S. aureus MW2 persister cells by adding 20 μg/ml of gentamicin to an overnight bacterial culture and incubating for an additional 4 h. After incubation, we washed the bacterial cells thrice with an equal volume of PBS and diluted the bacterial cells to OD600 ~ 0.4. Cells were treated with 1/2X MIC (Sub-MIC) of alpha mangostin and equimolar vancomycin concentration for 1 h. After incubation, we centrifuged the bacterial cell and washed the cells with PBS. Then, we performed RNA isolation and purification using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Using the Verso cDNA synthesis kit, we used the purified RNA for cDNA synthesis using the Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). We used the primers reported by (Dawan et al., 2020) (Table S1) for RT-PCR. Further, we performed the RT-PCR (iCycler iQ real-time detection system, Bio-Rad) by adding 5 μl of cDNA, 12.5 μl SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad), 2 μl of primers (5 mM), and 3.5 μl RNase free water (Ambion, St. Austin, TX, United States). The conditions for RT-PCR cycles were 95◦C for 30 s; 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 s; 55°C for 30 s; finishing with a melt curve analysis from 65 to 95°C (Khader et al., 2020). We calculated the relative expression ratio using the calculation as follows: n-fold expression = 2-ΔΔCt, ΔΔCt = ΔCt (drug-treated)/ΔCt (untreated), where ΔCt represents the difference between the cycle threshold (Ct) of the gene studied and the Ct of housekeeping 16S rRNA gene (internal control) (Mitchell et al., 2012).

Liver-derived HepG2 and lung-derived A549 cells were used to assess the mammalian cell cytotoxicity of alpha mangostin using previously described methods (Kim et al., 2018b; Peng et al., 2021). The cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, MD, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, MD, USA) and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were harvested and resuspended in a fresh medium, and 100 μl were distributed in a 96-well plate at 1 × 106 cells/well. Alpha mangostin were serially diluted in serum, antibiotic-free DMEM added to the monolayer of the cells, and the plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. At 4 h, before the end of the incubation period, 10 μl of 2-(4-iodophenyl)-3- (4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2, 4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (WST-1) solution (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was added to each well. WST-1 reduction was monitored at 450 nm using a using SpectraMax M2 Multi-mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Assays were performed in triplicate, and the percentage of cell survival was calculated. The lethal dose (LD50) is considered the concentration of compounds responsible for killing 50% of cells (Musa et al., 2010).

The hemolytic activity of alpha mangostin was tested towards haemoglobin based on a modified method (Lin et al., 2020). Human erythrocytes were purchased from Rockland Immuno- chemicals (Limerick, PA, USA), washed thrice with equal volume PBS and made 4% hRBCs. In 96-well microtiter well plate, 100 μl of RBCs were added to 100 μl of alpha mangostin serially diluted in PBS from 128-4 μg/ml. 1% of Triton-X 100 was used as the positive control, and PBS alone was used as a negative control. The plate was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, centrifuged at 500x g for 5 min. One hundred microlitres of supernatant were transferred to a fresh 96 well microtiter well plate, and the OD was measured at 540 nm. The percentage of hemolysis was calculated using 100% hemolysis caused by 1% Triton X-100. The values were represented as the mean of duplicates. The following formula calculated the percentage of hemolysis: (A540 nm in the peptide solution − A540 nm in PBS)/(A540 nm of 1% Triton X-100 treated sample − A540 nm in PBS) × 100 (Peng et al., 2021). Zero and 100% percentage hemolysis were determined in PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100, respectively.

The value of the Therapeutic index (TI) represents the property of cell selectivity of a drug molecule. TI is a measurement of the capability of distinctions between any pathogen and its host cells. The TI is calculated as the ratio of MHC (minimum hemolytic activity) and MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) (Chen et al., 2005). We did not observe any detectable hemolysis at 8 μg/mL of alpha mangostin. So, we used the MHC value of 16 μg/ml to calculate the TI.

To study the protective effects of the alpha mangostin in an in vivo model, we used an established wax moth model system (Peleg et al., 2009; Desbois and Coote, 2011). G. mellonella larvae (Vanderhorst Wholesale, St. Mary’s, OH, USA) were distributed in a different group with randomly selected larvae (n = 16/group). S. aureus MW2 persister cells were prepared by adding 20 μg/ml of gentamicin to an overnight bacterial culture and incubated for an additional 4 h. After incubation, the bacterial cells were washed thrice with an equal volume of PBS and were diluted to OD600 ~ 0.3. Experimental groups consisted of untouched (no injection), PBS (vehicle), bacterial infection, and treatment groups. Each group was injected with 10 μl (2 × 106 cells/ml) of the prepared bacteria, followed by alpha mangostin treatment (32-4 mg/kg doses) after 1 h. Vancomycin (25 mg/kg) was used as a positive control. All injections were performed using a Hamilton syringe (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) on the last left proleg. The larvae were incubated at 37°C for 5 days, with live and dead counts performed every 24 h.

We used the Student t-test for statistical analysis of biofilms and cell cytotoxicity. One-way ANOVA for qPCR analysis. p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference. For the G. mellonella survival experiment, we plotted the Kaplan–Meier curves using GraphPad Prism Version 6.04 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). We used the same program to perform statistical analysis and plotting of p < 0.05 value.

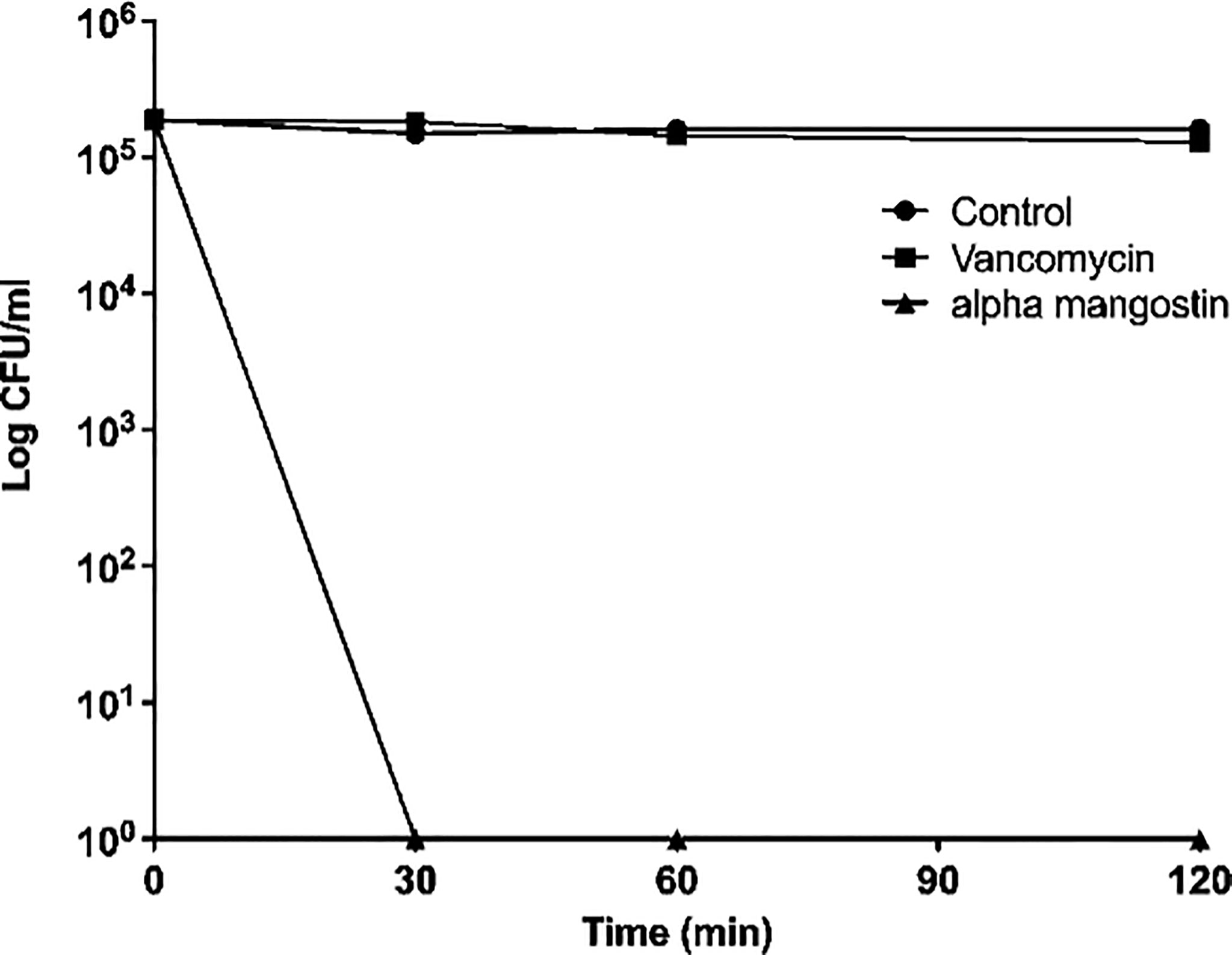

We first tested the antibacterial activity of alpha mangostin against S. aureus MW2 persisters and found that the MIC of alpha mangostin against S. aureus MW2 persisters was 2 μg/ml. Also, we performed time-kill kinetics of alpha mangostin against MRSA persisters at 1X MIC. Alpha mangostin exhibited rapid bactericidal activity and, within 30 mins of exposure. We assigned the 99.99% elimination of MRSA to denote no colonies of S. aureus MW2 persister on TSB plates upon exposure of 2 µg/ml of alpha mangostin for 30 mins (Figure 1). In contrast, vancomycin (at 4 μg/ml) was ineffective in decreasing the bacteria counts up to 120 mins.

Figure 1 Killing kinetics. Growth curves were generated using S. aureus MW2 persister cells. Colony-forming units were measured by plating the treated and untreated bacterial cells on a TSA plate after serial dilution. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

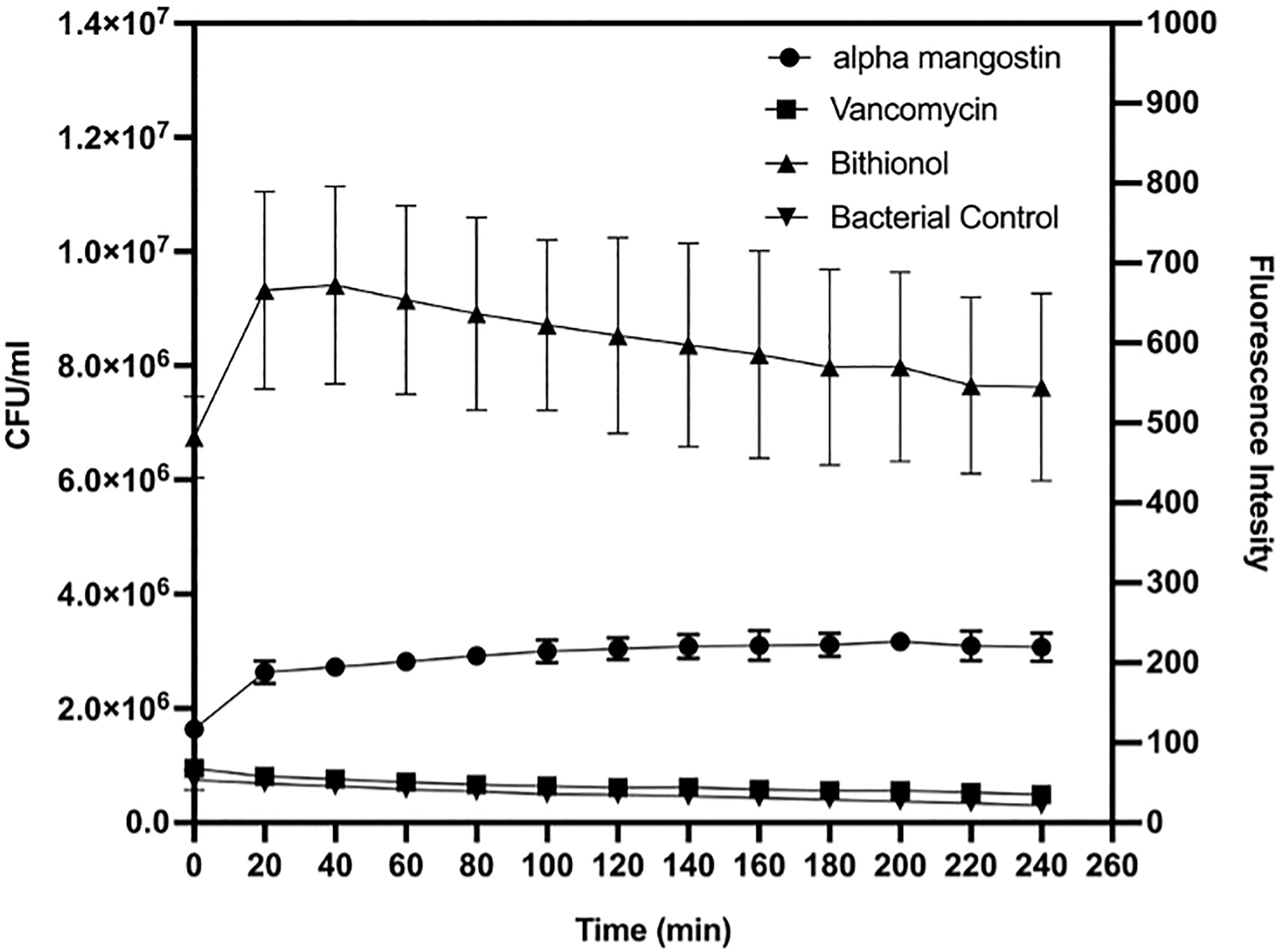

As shown in Figure 2, alpha mangostin induced rapid membrane permeabilization at the MIC concentration (2 μg/ml). The relative fluorescence for persister cells was 220 units and 540 units for alpha mangostin and bithionol, respectively. Notably, the relative fluorescence for normal cells (non-persister cell) was 600 units and 900 units for alpha mangostin and bithionol, respectively (Figure S1).

Figure 2 Time course membrane permeabilization by alpha mangostin (2 μg/ml), vancomycin (4μg/ml), and bithionol (2 μg/ml) against S. aureus MW2 persisters. Membrane permeabilization was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the SYTOX green dye uptake (excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm). Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

We performed a checkerboard titration assay to evaluate the interaction of alpha mangostin with conventional antibiotics (Table S2). The FICI index of mupirocin (0.5), rifampicin (1.03), ciprofloxacin (2.1), gentamicin (2.5), and vancomycin (3.0) suggests exerting an additive effect. In contrast, norfloxacin was an antagonist with a FICI index of > 5. The results of the checkerboard assay gave an insight into using alpha mangostin in combination with antibiotics to improve the efficacy against MRSA persister and biofilm.

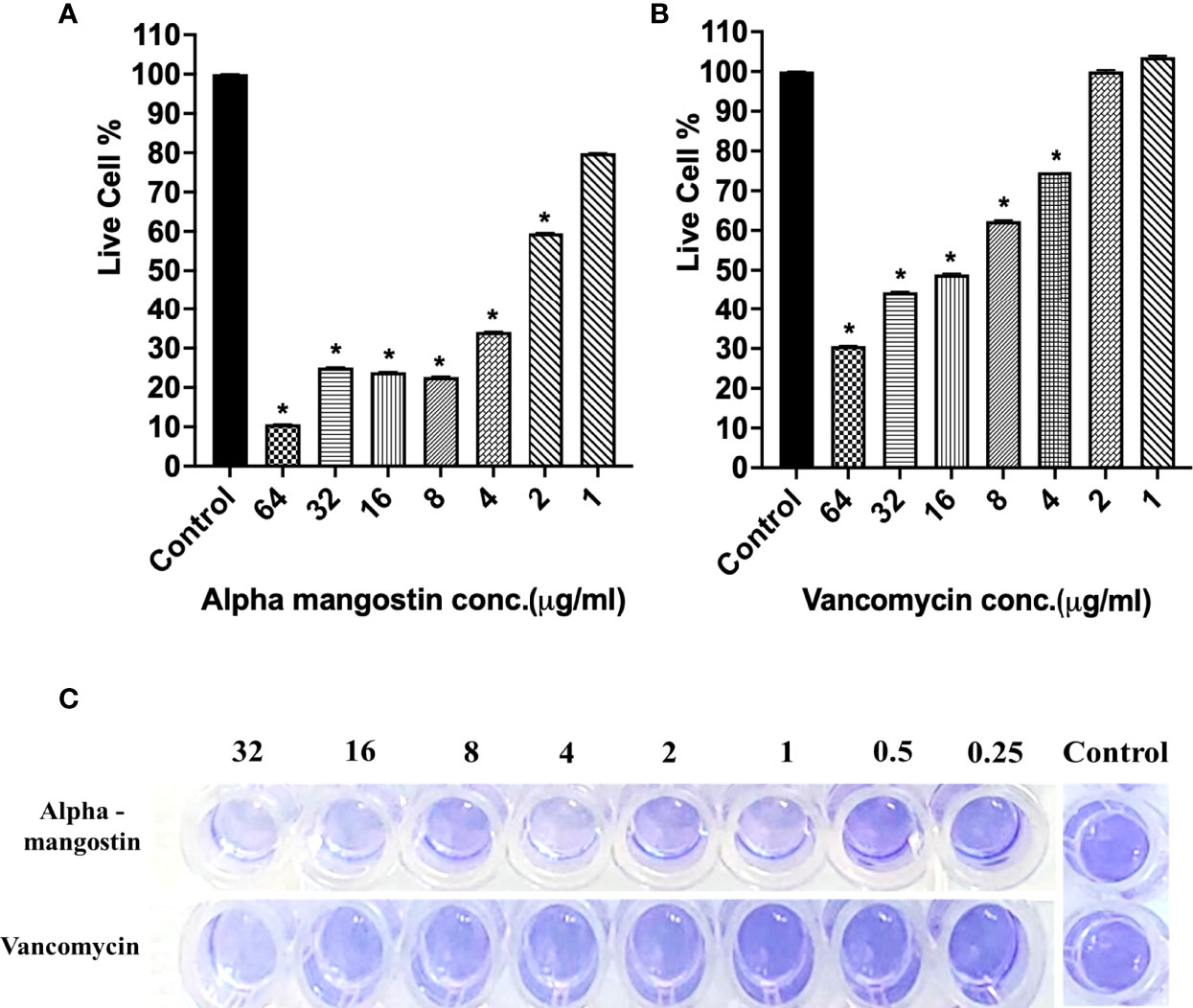

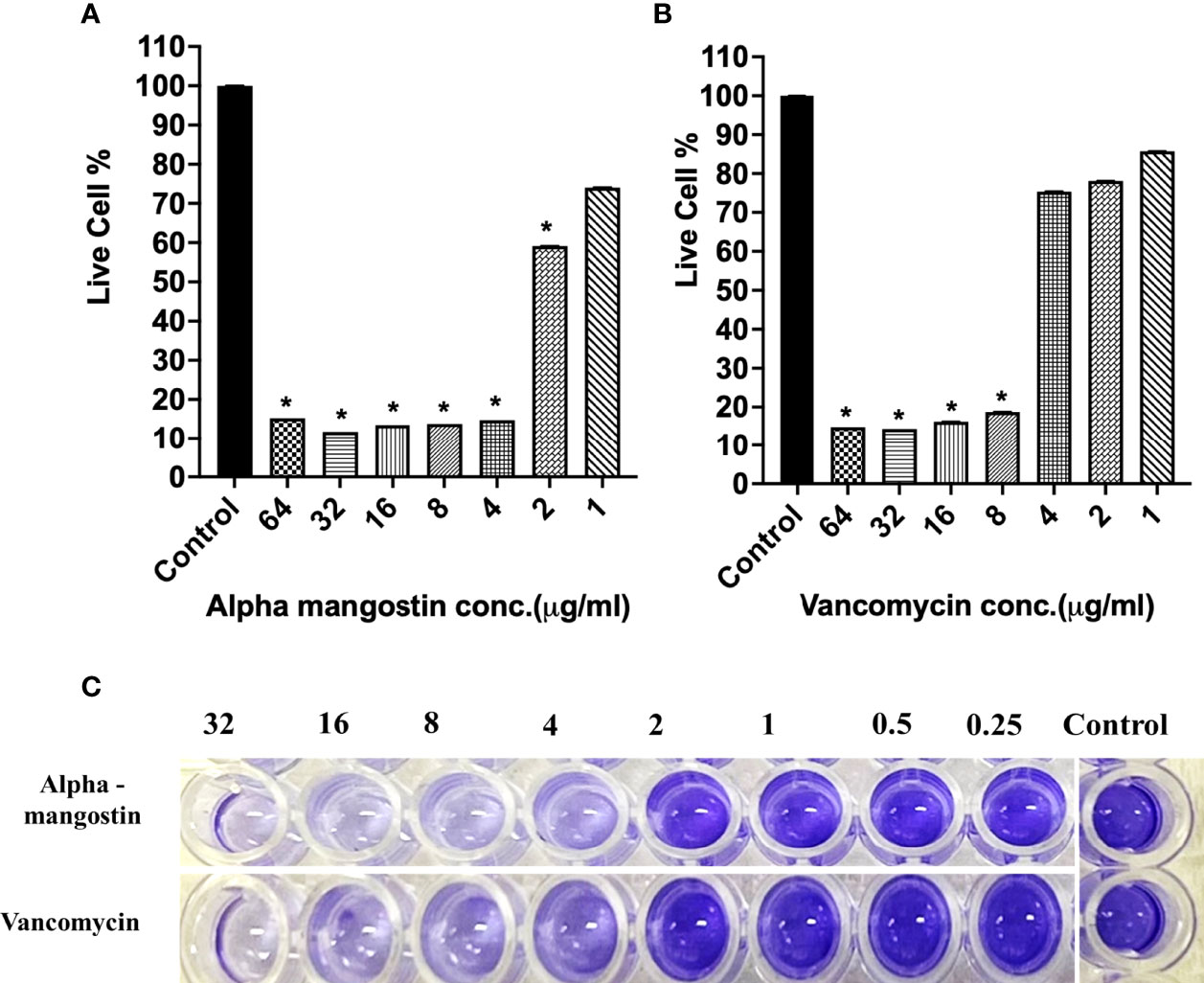

To check the antibiofilm efficacy of alpha mangostin, we conducted antibiofilm assays evaluating the inhibition of the three different stages of S. aureus MW2 biofilms (initial attachment, formation, and disruption of established biofilm) (Figure 3). We tested the effects of alpha mangostin from concentrations ranging from 64-1 μg/ml against all three biofilm stages (initial adhesion, biofilm formation, and established biofilms of S. aureus MW2). We included vancomycin as antibiotic control for comparison at a similar concentration range. At 64 μg/ml concentration, alpha mangostin reduced the initial bacteria attachment by 90% (Figures 3A, B). Live cell quantification of biofilm adhesion using XTT showed that alpha mangostin at 4 μg/ml inhibited more than 75% of the S. aureus MW2 initial bacterial adhesion. Further, CV staining provided visual confirmation of the efficacy of alpha mangostin in preventing initial adhesion of S. aureus MW2 biofilms in 96-well plates (Figure 3C).

Figure 3 (A, B) S. aureus MW2 initial biofilm adhesion in 96-well microtiter plate for 1 h treated with alpha mangostin and vancomycin at concentrations ranging from 64-1 µg/ml. Live cells % in the treated and non-treated initial biofilm adhesion quantified using XTT at OD450. Results are shown as means ± s.d.; n=3 (*p < 0.05). (C) Visual depiction of the initial biofilm adhesion with CV staining in 96-well microtiter plate after treatment with alpha mangostin and vancomycin at comparable concentrations.

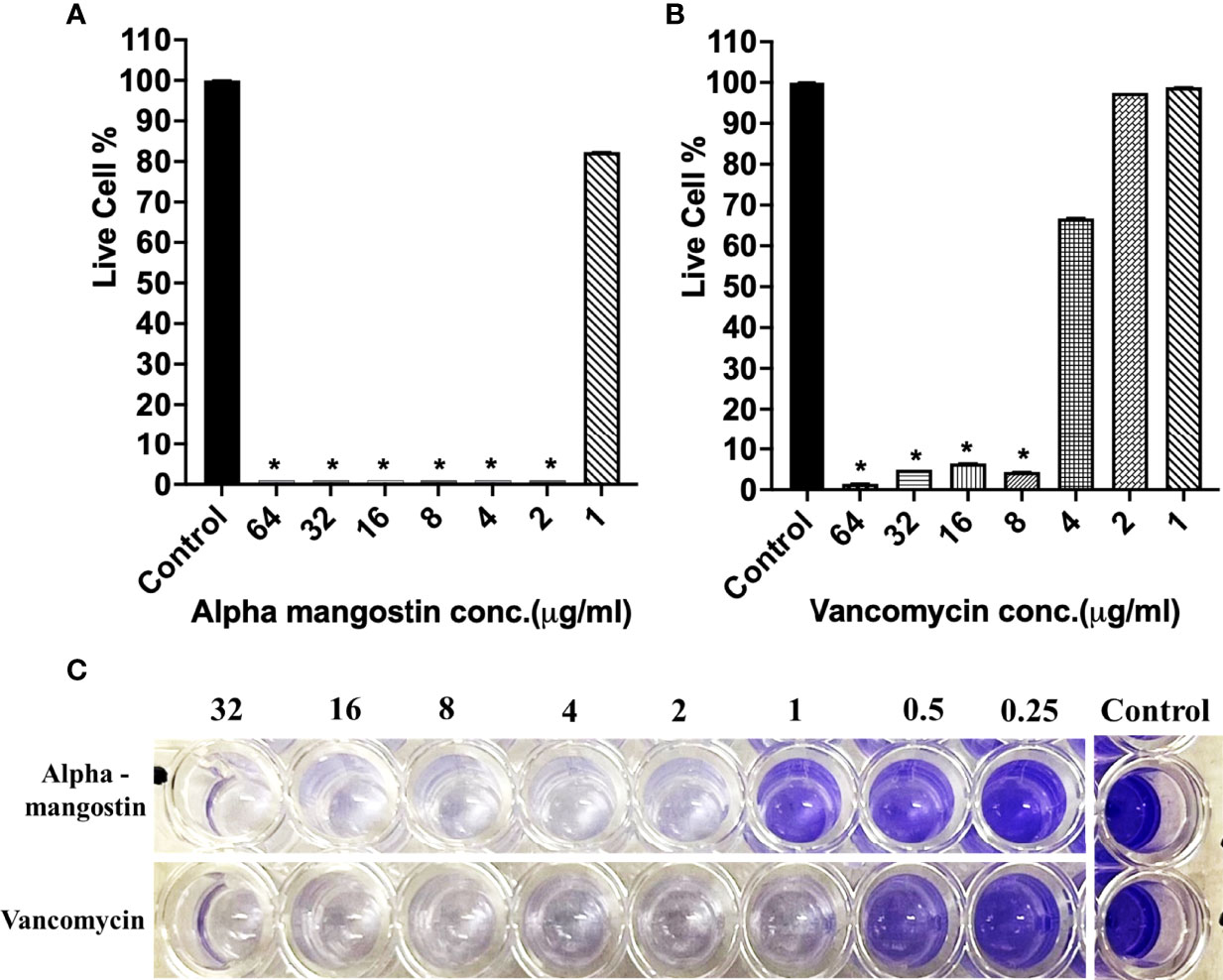

In the case of inhibiting S. aureus MW2 biofilm formation, alpha mangostin at 2 μg/ml reduced the percentage of live cells to less than 15%, while vancomycin was effective at 1 μg/ml concentration (Figures 4A, B). The lowest concentration of any test compound required to inhibit maximum (>50%) biofilm formation is considered as minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) (Cruz et al., 2018). Using live-cell quantification by XTT, we found that alpha mangostin at 2 μg/ml inhibited more than >50% of the S. aureus MW2 biofilms at its formation stage (Figure 4A). In agreement, CV staining also showed a gradual increase of violet color depicting more biomass in wells treated with lower concentrations of alpha mangostin (up to 1 μg/ml) (Figure 4C). Therefore, we determined the MBIC value for alpha mangostin as 2 μg/ml against S. aureus MW2 biofilm formation.

Figure 4 (A, B) S. aureus MW2 biofilm formation in 96-well microtiter plate for 24 h treated with alpha mangostin and vancomycin at concentrations ranging from 64-1 µg/ml. Live cells % in the treated and non-treated biofilm formation were quantified using XTT at OD450. Results are shown as means ± s.d.; n=3 (*p < 0.05). (C) Visual depiction of the biofilm formation with CV staining in 96-well microtiter plate after treatment with alpha mangostin and vancomycin at comparable concentrations.

Using XTT quantification, we determined the minimum biofilm eradicating concentration (MBEC) of alpha mangostin against 24 h established biofilms of S. aureus MW2. The MBEC value is determined as the lowest concentration of any test compound required to eradicate maximum (>50%) established biofilms (Cruz et al., 2018). Alpha mangostin at twice its MIC (4 μg/ml) eradicated 96% of established S. aureus biofilms, while at 4 μg/ml, it only reduced 40% of the biofilms (Figures 5A). In comparison, at a similar concentration of 4 μg/ml, vancomycin only reduced 18% of the established biofilms (Figures 5B). Thus, we determined the MBEC value of alpha mangostin as 4 μg/ml against S. aureus MW2 biofilm formation. Further, we used CV staining to confirm the disruption of S. aureus mature biofilm at 4 μg/ml of alpha mangostin (Figure 5C).

Figure 5 (A, B) S. aureus MW2 mature biofilm in a 96-well microtiter plate for 24 h treated with alpha mangostin and vancomycin at concentrations ranging from 64-1 µg/ml. Live cells % in the treated and non-treated S. aureus MW2 mature were quantified using XTT at OD450. Results are shown as means ± s.d.; n=3 (*p < 0.05). (C) Visual depiction of the S. aureus MW2 mature with CV staining in 96-well microtiter plate after treatment with alpha mangostin and vancomycin at comparable concentrations.

To visualize the effect of alpha mangostin on biofilm formation and mature biofilm stages of S. aureus MW2, we performed confocal microscopic analysis. We treated the biofilms with 2 μg/ml of alpha mangostin corresponding to its MBIC value to inhibit biofilm formation. Similarly, for established S. aureus MW2 biofilms, we used 4 μg/ml of alpha mangostin corresponding to its MBEC concentration. In a LIVE/DEAD staining, most cells, including live cells, uptakes SYTO9 and fluoresce green, while PI penetrates the dead cells and fluoresce red. Interestingly, the 2D, Ortho, and 3D images of alpha mangostin for treated MRSA biofilms at both stages showed; reduced bacterial biomass in the biofilm matrix, less biofilm thickness, and the presence of red color indicative of dead cells in the S. aureus MW2 biofilm (Figures 6, 7).

Figure 6 Confocal microscopic images of the S. aureus MW2 biofilm formation treated with alpha mangostin (2 μg/ml). S. aureus MW2 biofilm treated and untreated with alpha mangostin was stained with SYTO-9 dye that stains live cells green and propidium iodide (PI) that stains dead cells red. Scale bars correspond to 10 µm.

Figure 7 Confocal microscopic images of the S. aureus MW2 mature biofilm treated with alpha mangostin (2 μg/ml). S. aureus MW2 mature biofilm treated and untreated with alpha mangostin was stained with SYTO-9 dye that stains live cells green and propidium iodide (PI) that stains dead cells red. Scale bars correspond to 10 µm.

We tested the efficacy effect of alpha mangostin to down-regulate the gene involved in S. aureus persister formation (Figure 8). Four important genes, including norA, norB, dnaK, groEL and mepR were tested at the transcriptional level. We treated the MRSA persister with sub- MIC concentration (1 μg/ml) of alpha mangostin. As control, we used vancomycin at equimolar concentrations. Interestingly, alpha mangostin down-regulated all tested genes and significantly down-regulated norA and dnaK by 4-fold, groEL, and mepR by 3-fold, and norB by 2-fold (p<0.0001). On the other hand, vancomycin upregulated norB, groEL, and mepR and down-regulated dnaK.

Figure 8 Alpha mangostin down-regulates genes associated with the formation of MRSA persister and biofilms. S. aureus MW2 persister treated with a sub-MIC concentration of alpha mangostin for 4h. Exposure of alpha mangostin was associated with the down-regulation of persister and biofilm-forming genes. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05 analyzed by One-way ANOVA.

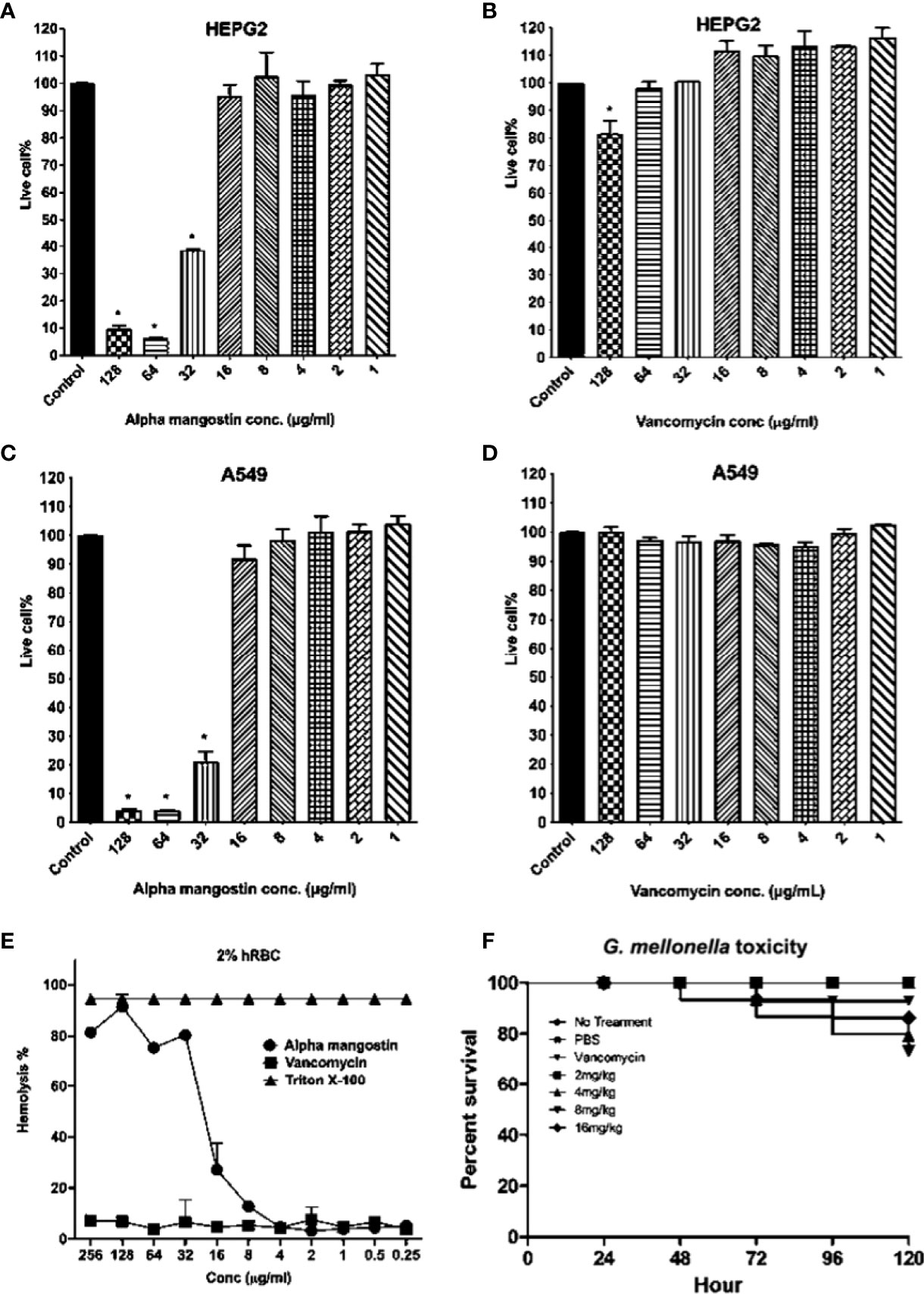

We tested the toxicity of alpha mangostin to human cell lines, red blood cells and a whole-body Galleria mellonella wax moth model (Figure 9). The LD50 value of alpha mangostin and vancomycin against HEPG2 cells was found to be < 32 μg/ml (only 40% of cells survived at this concentration) and >128 μg/ml, respectively (Figures 9A, B). For A549 cell lines, only 22% of cells survived at 32 μg/ml of alpha mangostin, while 100% of cells survived up after exposure to vancomycin at 128 μg/ml of vancomycin (Figures 9C, D). We further evaluated the toxicity of alpha mangostin to human red blood cells (Figure 9E). The alpha mangostin was found to cause 50% human red blood lysis (HL50) at a concentration of 16 μg/ml, which is higher than 5 times the MIC values against S. aureus persister. We also tested the toxicity of alpha mangostin in a live wax moth larvae model (Figure 9F). We found that 80% of G. mellonella larvae survived alpha mangostin up to 120 h (p=0.001). But at the higher concentration of 16 mg/Kg of alpha mangostin, only 20% of G. mellonella larvae died.

Figure 9 Cytotoxicity, hemolytic, and in vivo G. mellonella toxicity of alpha mangostin. (A–D) Cellular toxicity of alpha mangostin against liver-derived HEPG2 and lung-derived A549 cell lines showed that the LD50 values (p < 0.05) as16 μg/ml. (E) Hemolysis of human blood red cells (hRBCs) showed the HL50 of alpha mangostin was 16 μg/ml. Vancomycin was used as a negative control and Triton-X (0.0025-1%) was used as a positive control (F) The toxicity of alpha mangostin tested in G. mellonella model showed that >70% of larvae survived at the higher concentration of 16 mg/kg until 120 h (p<0.05). Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3) for 5 A-E and n=16 larvae per group for 5F.

The therapeutic index is commonly used to identify the specificity of antimicrobial agents. A higher therapeutic index value indicates greater antimicrobial specificity. In our study, the MHC of alpha mangostin against mammalian erythrocytes was 16 μg/ml, while the MIC against S. aureus MW2 was 2 μg/ml. Thus, calculating the ratio of MHC and MIC gives the TI value of alpha mangostin as 8 (Table 1).

Table 1 Minimum inhibitory concentration, Minimal hemolytic concentration and therapeutic index of alpha mangostin against S.aureus MW2.

Because of toxicity, alpha mangostin may need to be evaluated in combination with other antibiotics and we performed a checkerboard titration assay to evaluate the interaction of alpha mangostin with conventional antibiotics (Table S2). The FICI index of mupirocin (0.5), rifampicin (1.03), ciprofloxacin (2.1), gentamicin (2.5) and vancomycin (3.0) suggests exerting an additive effect.

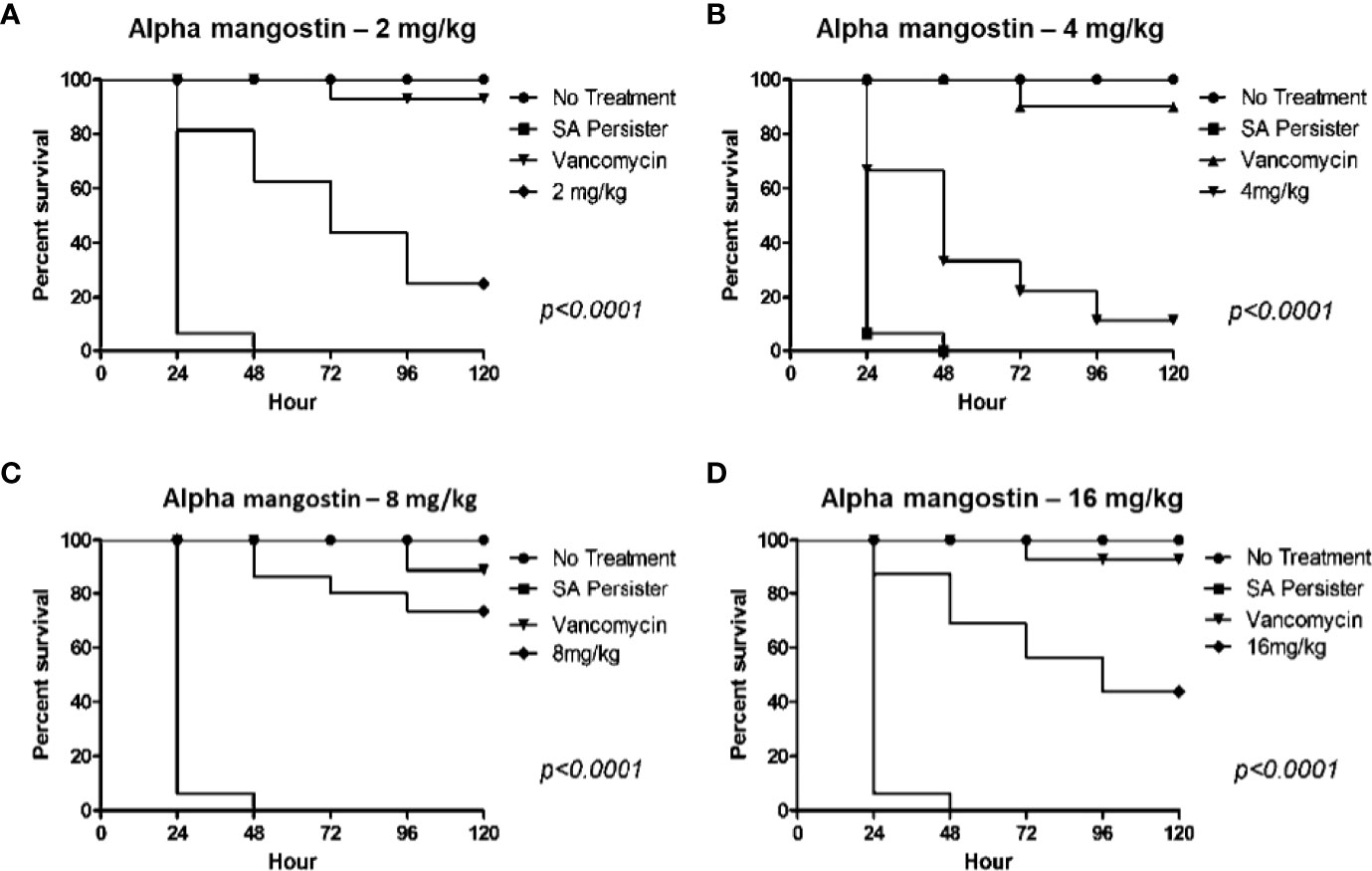

We also evaluated the in vivo efficacy of alpha mangostin in preventing the killing of G. mellonella by MRSA persisters (Figure 10). In order to confirm that injected MRSA cells were in a persister state, we isolated the MRSA from the larva after incubation for 24 h and tested the MIC of the isolated MRSA against vancomycin. The MIC of vancomycin was > 64 μg/ml, validating the persister state. Interestingly, alpha mangostin improved the survival of G. mellonella larvae infected with MRSA persister cells up to 16 mg/kg. A dose of 8 mg/kg rescued 75% of larvae (p<0.0001). The lower concentrations of alpha mangostin (2 and 4 mg/kg) were less effective, while the reduced survival of G. mellonella larva at 16 mg/kg was attributed to probable toxicity induced by alpha mangostin.

Figure 10 In vivo activity of alpha mangostin against S. aureus MW2 persisters in the G. mellonella wax moth model. (A–D). Sixteen S. aureus persister infected G. mellonella were treated with control (PBS), 25 mg/kg vancomycin and 2, 4, 8, 16 mg/kg alpha mangostin at 1 h of post infection. Seventy five percentage of larvae survived with treatment of 8 mg/kg of alpha mangostin was significant compared to PBS treatment (p<0.0001).

S. aureus causes acute and recalcitrant infections due to the emergence of antibiotic tolerant and metabolically dormant persister cells (Chambers and DeLeo, 2009; Tong et al., 2015; Poolman and Anderson, 2018; Kim et al., 2019). The treatment of S. aureus infections is often complicated due to the ability of the bacteria to form persister cells (Conlon, 2014). Key strategies to eradicate S. aureus persister cells include metabolic stimuli that enable the killing of bacteria by antibacterial agents such as aminoglycosides (Allison et al., 2011), and the use of compounds that target the bacterial membrane (Kim et al., 2019). In this context, our findings demonstrated that alpha mangostin penetrates MRSA persister cell membranes (Figure 2) and interferes with the development of MRSA biofilms. Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana) is a common tropical fruit in Southeast Asia, India, and Sri Lanka that is used in traditional medicine for the treatment of skin infections, chronic wounds, and dysentery (Pedraza-Chaverri et al., 2008). Xanthones derivatives are the major bioactive molecules of mangostin that display potential antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, and anti-allergy properties (Pedraza-Chaverri et al., 2008; Obolskiy et al., 2009). A specific xanthone derivative that exhibits antibacterial properties is alpha mangostin (1,3,6-trihydroxy-7-methoxy-2,8-bis(3-methylbut-2-enyl)xanthen-9-one) derived from mangostin pericarp extracts (Nguyen and Marquis, 2011). Koh et al. (2013) used fluorescent dyes to demonstrate that alpha mangostin causes membrane disruptions leading to leakage of intracellular contents in S. aureus and MRSA. Interestingly, this work demonstrated that the hydrophobic association of alpha mangostin with the lipid membrane of S. aureus causes membrane deformation and diffusion of water molecules (Koh et al., 2013). Later, Phuong et al. (2017) provided additional evidence on the alteration of the staphylococcal membrane by alpha mangostin. However, these reports did not study the effects of this compound against staphylococcal persister cells, and our findings expand these previous reports by demonstrating the rapid bactericidal activity of alpha mangostin against S. aureus persister cells (Figures 1, 2) and we found that alpha mangostin effectively down-regulates the gene involved in S. aureus persister formation (Figure 8). Furthermore, previous studies reported that alpha mangostin works only against the preformed biofilms of S. aureus (Phuong et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2021). Then, we use the G. mellonella model to demonstrate that alpha mangostin is effective against S. aureus persister cells during infection (Figure 10). To our knowledge, this is the first report on the effects of alpha mangostin on S. aureus persister cells under in vitro and in vivo conditions. In this report, we report that alpha mangostin inhibits and disrupts the formation of S. aureus biofilms at all three stages (initial adhesion, formation, and maturation) (Figures 3–5). According to Phuong et al. (2017), alpha mangostin inhibited MRSA biofilm formation but did not affect the mature biofilms of MRSA. Our study expands this finding by demonstrating the effects of alpha mangostin in various stages of S. aureus biofilm formation (Figures 3–5). Confocal microscopic evidence revealed that alpha mangostin reduces the thickness of S. aureus biofilm at various stages (biofilm formation and mature biofilm).

MRSA persister and biofilm are tolerant to antimicrobial agents and show reduced metabolic activity (Waters et al., 2016). In S. aureus, the formation of both persister cells and biofilm is mediated by genes such as norA, norB, dnaK, groEL, and mepR (Arita-Morioka et al., 2015; abd El-Baky, 2016; Dawan et al., 2020). More specifically, norA and norB are associated with antimicrobial resistance and tolerance in biofilm (Soto, 2013) and norA is associated with resistance against hydrophilic fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin), while norB regulates efflux pumps induced by both hydrophobic and hydrophilic fluoroquinolones (Costa et al., 2013). Additionally, both dnaK and groEL encode molecular chaperones that regulate persister cell and biofilm formation (Arita-Morioka et al., 2015; abd El-Baky, 2016; Dawan et al., 2020), while mepR belongs to the multidrug and toxic compound transporter family and is associated with repression of the multidrug transporter (MepA) (Schindler and Kaatz, 2016; Dawan et al., 2020).

Toxicity analysis is an important step in drug discovery for determining the drug concentration, controlled exposure, and duration of exposure to both animals and humans. We tested the toxicity of alpha mangostin in the mammalian cell membrane, sheep red blood cells (RBCs), and a G. mellonella model. Alpha mangostin exhibited dose-dependent toxicity to the mammalian cell membrane and sheep RBCs, suggesting that the therapeutic window is relatively narrow. Nevertheless, alpha mangostin was active in the G. mellonella model which is widely used to evaluate drug toxicity and efficacy of antibacterial agents (Cutuli et al., 2019). We opted to use the wax moth model since it is well established in determining the survival rate of larva after infection with S. aureus (Khader et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020). The G. mellonella model is widely used to determine the pathogenicity and virulence of multiple pathogens, including MRSA and S. aureus (Peleg et al., 2009; Desbois and Coote, 2011). We also tested alpha mangostin in G. mellonella larva after infecting them with MRSA persister cells.

In conclusion, we report that alpha mangostin is effective against MRSA persister cells and biofilm. The high antimicrobial efficacy, fast killing kinetics, membrane targeting, anti-persister, and anti-biofilm characteristics of alpha mangostin suggest that the compound merits further study for the management of topical infections caused by MRSA. Importantly, the toxicity profile of alpha mangostin must be further assessed before this agent can be evaluated for systemic administration.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

LF, BM, RK and NG designed and carried out experiments. EM directed research, provided insightful discussions and contributed to the writing. All authors analyzed results, revised the manuscript, and approved of the final version

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 AI083214 to EM. This work was supported by P20GM121344 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which funds the Center for Antimicrobial Resistance and Therapeutic Discovery to BM.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2022.898794/full#supplementary-material

abd El-Baky, R.M. (2016). The Future Challenges Facing Antimicrobial Therapy: Resistance and Persistence. Am. J. Microbiol. Res, 4 (1), 1–15.

Ahmed, M. O., Baptiste, K. E. (2018). Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci: A Review of Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms and Perspectives of Human and Animal Health. Microb Drug Resistance 24, 590–606. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0147

Allison, K. R., Brynildsen, M. P., Collins, J. J. (2011). Metabolite-Enabled Eradication of Bacterial Persisters by Aminoglycosides. Nature 473, 216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature10069

Andersson, D. I., Balaban, N. Q., Baquero, F., Courvalin, P., Glaser, P., Gophna, U., et al. (2021). Antibiotic Resistance: Turning Evolutionary Principles Into Clinical Reality. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44, 171–188. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuaa001

Arita-Morioka, K. I., Yamanaka, K., Mizunoe, Y., Ogura, T., Sugimoto, S. (2015). Novel Strategy for Biofilm Inhibition by Using Small Molecules Targeting Molecular Chaperone DnaK. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 (1), 633–641.

Balaban, N. Q., Merrin, J., Chait, R., Kowalik, L., Leibler, S. (2004). Bacterial Persistence as a Phenotypic Switch. Sci. (1979) 305, 1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390

Brauner, A., Fridman, O., Gefen, O., Balaban, N. Q. (2016). Distinguishing Between Resistance, Tolerance and Persistence to Antibiotic Treatment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 320–330. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.34

Chambers, H. F., DeLeo, F. R. (2009). Waves of Resistance: Staphylococcus Aureus in the Antibiotic Era. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 7 (9), 629–641.

Chang, J. O., Lee, R. E., Lee, W. (2020). A Pursuit of Staphylococcus Aureus Continues: A Role of Persister Cells. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 43, 630–638. doi: 10.1007/s12272-020-01246-x

Chen, Y., Mant, C. T., Farmer, S. W., Hancock, R. E. W., Vasil, M. L., Hodges, R. S. (2005) Rational Design of α-Helical Antimicrobial Peptides With Enhanced Activities and Specificity/Therapeutic Index J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12316–12329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413406200

CLSI (2018). “Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically,” in CLSI Standards M07, 11th ed (Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute).

Conlon, B. P. (2014). Staphylococcus Aureus Chronic and Relapsing Infections: Evidence of a Role for Persister Cells: An Investigation of Persister Cells, Their Formation and Their Role in S. Aureus Disease. BioEssays 36, 991–996. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400080

Conlon, B. P., Rowe, S. E., Lewis, K. (2015). Persister Cells in Biofilm Associated Infections. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 831, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09782-4_1

Costa, S. S., Viveiros, M., Amaral, L., Couto, I. (2013). Multidrug Efflux Pumps in Staphylococcus Aureus: An Update. The Open Microbiol. J. 7, 59.

Craft, K. M., Nguyen, J. M., Berg, L. J., Townsend, S. D. (2019). Methicillin-Resistant: Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA): Antibiotic-Resistance and the Biofilm Phenotype. Medchemcomm 10, 1231–1241. doi: 10.1039/c9md00044e

Cruz, C. D., Shah, S., Tammela, P. (2018). Defining Conditions for Biofilm Inhibition and Eradication Assays for Gram-Positive Clinical Reference Strains. BMC Microbiol. 18, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1321-6

Cutuli, M. A., Petronio Petronio, G., Vergalito, F., Magnifico, I., Pietrangelo, L., Venditti, N., et al. (2019). Galleria Mellonella as a Consolidated in Vivo Model Hosts: New Developments in Antibacterial Strategies and Novel Drug Testing. Virulence 10 (1), 527–541.

Dawan, J., Wei, S., Ahn, J. (2020). Role of Antibiotic Stress in Phenotypic Switching to Persister Cells of Antibiotic-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Ann. Microbiol. 70, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13213-020-01552-1

Desbois, A. P., Coote, P. J. (2011). Wax Moth Larva (Galleria Mellonella): An In Vivo Model for Assessing the Efficacy of Antistaphylococcal Agents. J. Antimicrob ChemotheR 66, 1785–1790. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr198

Fisher, R. A., Gollan, B., Helaine, S. (2017). Persistent Bacterial Infections and Persister Cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 453–464. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.42

Iluz, N., Maor, Y., Keller, N., Malik, Z. (2018). The Synergistic Effect of PDT and Oxacillin on Clinical Isolates of Staphylococcus Aureus. Lasers Surg. Med. 50, 535–551. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22785

Khader, R., Tharmalingam, N., Mishra, B., Felix, L., Ausubel, F. M., Kelso, M. J., et al. (2020). Characterization of Five Novel Anti-MRSA Compounds Identified Using a Whole-Animal Caenorhabditis Elegans/Galleria Mellonella Sequential-Screening Approach. Antibiotics 9, 449. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9080449

Kim, W., Conery, A. L., Rajamuthiah, R., Fuchs, B. B., Ausubel, F. M., Mylonakis, E. (2015). Identification of an Antimicrobial Agent Effective Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Persisters Using a Fluorescence-Based Screening Strategy. PloS One 10, 1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127640

Kim, W., Fricke, N., Conery, A. L., Fuchs, B. B., Rajamuthiah, R., Jayamani, E., et al. (2016). NH125 Kills Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Persisters by Lipid Bilayer Disruption. Future Med Chem. 8, 257–269. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.189

Kim, W., Steele, A. D., Zhu, W., Csatary, E. E., Fricke, N., Dekarske, M. M., et al. (2018a). Discovery and Optimization of Ntzdpa as an Antibiotic Effective Against Bacterial Persisters. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 1540–1545. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00161

Kim, W., Zhu, W., Hendricks, G. L., Van Tyne, D., Steele, A. D., Keohane, C. E., et al. (2018b). A New Class of Synthetic Retinoid Antibiotics Effective Against Bacterial Persisters. Nature 556, 103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature26157

Kim, W., Zou, G., Hari, T. P., Wilt, I. K., Zhu, W., Galle, N., et al. (2019). A Selective Membrane-Targeting Repurposed Antibiotic With Activity Against Persistent Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116 (33), 16529–16534.

Kim, W., Zou, G., Pan, W., Fricke, N., Faizi, H. A., Kim, S. M., et al. (2020). The Neutrally Charged Diarylurea Compound PQ401 Kills Antibiotic-Resistant and Antibiotic-Tolerant Staphylococcus Aureus. MBio. 11 (3), e01140-20.

Koh, J. J., Qiu, S., Zou, H., Lakshminarayanan, R., Li, J., Zhou, X., et al. (2013). Rapid Bactericidal Action of Alpha-Mangostin Against MRSA as an Outcome of Membrane Targeting. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 1828, 834–844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.09.004

Lechner, S., Lewis, K., Bertram, R. (2012). Staphylococcus Aureus Persisters Tolerant to Bactericidal Antibiotics. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 22, 235–244. doi: 10.1159/000342449

LewisOscar, F., Nithya, C., Bakkiyaraj, D., Arunkumar, M., Alharbi, N. S., Thajuddin, N. (2017). Biofilm Inhibitory Effect of Spirulina Platensis Extracts on Bacteria of Clinical Significance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect B - Biol. Sci. 87, 537–544. doi: 10.1007/s40011-015-0623-9

Lin, S., Zhu, C., Li, H., Chen, Y., Liu, S. (2020). Potent In Vitro and In Vivo Antimicrobial Activity of Semisynthetic Amphiphilic γ-Mangostin Derivative LS02 Against Gram-Positive Bacteria With Destructive Effect on Bacterial Membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr 1862, 183353. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183353

Mishra, B., Golla, R. M., Lau, K., Lushnikova, T., Wang, G. (2016). Anti-Staphylococcal Biofilm Effects of Human Cathelicidin Peptides. ACS Med Chem. Lett. 7, 117–121. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00433

Mitchell, G., Lafrance, M., Boulanger, S., Séguin, D. L., Guay, I., Gattuso, M., et al. (2012). Tomatidine Acts in Synergy With Aminoglycoside Antibiotics Against Multiresistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Prevents Virulence Gene Expression. J. Antimicrob Chemother 67, 559–568. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr510

Musa, M. A., Badisa, V. L. D., Latinwo, L. M., Waryoba, C., Ugochukwu, N. (2010). In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Benzopyranone Derivatives With Basic Side Chain Against Human Lung Cell Lines. Anticancer Res. 30, 4613–4617.

Nguyen, P. T., Marquis, R. E. (2011). Antimicrobial Actions of α-Mangostin Against Oral Streptococci. Can. J. Microbiol. 57 (3), 217–225.

Nguyen, P. T. M., Nguyen, M. T. H., Bolhuis, A. (2021). Inhibition of Biofilm Formation by Alpha-Mangostin Loaded Nanoparticles Against Staphylococcus Aureus. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.061

Obolskiy, D., Pischel, I., Siriwatanametanon, N., Heinrich, M. (2009). Garcinia Mangostana L.: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Review. Phytother Res. 23, 110–118. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2730

Okwu, M. U., Olley, M., Akpoka, A. O., Izevbuwa, O. E. (2019). Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) and Anti-MRSA Activities of Extracts of Some Medicinal Plants: A Brief Review. AIMS Microbiol. 5, 117. doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2019.2.117

Pedraza-Chaverri, J., Cárdenas-Rodríguez, N., Orozco-Ibarra, M., Pérez-Rojas, J. M. (2008). Medicinal Properties of Mangosteen (Garcinia Mangostana). Food Chem. Toxicol. 46, 3227–3239. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.07.024

Peleg, A. Y., Jara, S., Monga, D., Eliopoulos, G. M., Moellering, R. C., Mylonakis, E. (2009). Galleria Mellonella as a Model System to Study Acinetobacter Baumannii Pathogenesis and Therapeutics. Antimicrob Agents ChemotheR 53, 2605–2609. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01533-08

Peng, J., Mishra, B., Khader, R., Felix, L. O., Mylonakis, E. (2021). Novel Cecropin-4 Derived Peptides Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Antibiotics 10, 36. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10010036

Peyrusson, F., Varet, H., Nguyen, T. K., Legendre, R., Sismeiro, O., Coppée, J. Y., et al. (2020). Intracellular Staphylococcus Aureus Persisters Upon Antibiotic Exposure. Nat. Commun., 11 (1), 1–14.

Phuong, N. T. M., van Quang, N., Mai, T. T., Anh, N. V., Kuhakarn, C., Reutrakul, V., et al. (2017). Antibiofilm Activity of α-Mangostin Extracted From Garcinia Mangostana L. Against Staphylococcus Aureus. Asian Pacific J. Trop. Med. 10, 1154–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.10.022

Poolman, J. T., Anderson, A. S. (2018). Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus: Leading Bacterial Pathogens of Healthcare Associated Infections and Bacteremia in Older-Age Populations. Expert Rev. Vaccines 17, 1154–1160. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1488590

Schindler, B. D., Kaatz, G. W. (2016). Multidrug Efflux Pumps of Gram-Positive Bacteria. Drug Resistance Updates 27, 1–13.

Simões, D., Miguel, S. P., Ribeiro, M. P., Coutinho, P., Mendonça, A. G., Correia, I. J. (2018). Recent Advances on Antimicrobial Wound Dressing: A Review. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 127, 130–141.

Soto, S.M. (2013). Role of Efflux Pumps in the Antibiotic Resistance of Bacteria Embedded in a Biofilm. Virulence 4 (3), 223–229.

Tong, S. Y. C., Davis, J. S., Eichenberger, E., Holland, T. L., Fowler, V. G. (2015). Staphylococcus Aureus Infections: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14

Keywords: alpha mangostin, biofilm, persisters, Staphylococcus aureus, Galleria mellonella

Citation: Felix L, Mishra B, Khader R, Ganesan N and Mylonakis E (2022) In Vitro and In Vivo Bactericidal and Antibiofilm Efficacy of Alpha Mangostin Against Staphylococcus aureus Persister Cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12:898794. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.898794

Received: 17 March 2022; Accepted: 23 June 2022;

Published: 22 July 2022.

Edited by:

Gheyath Khaled Nasrallah, Qatar University, QatarReviewed by:

Maribasappa Karched, Kuwait University, KuwaitCopyright © 2022 Felix, Mishra, Khader, Ganesan and Mylonakis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eleftherios Mylonakis, ZW15bG9uYWtpc0BsaWZlc3Bhbi5vcmc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.