- 1Chongqing Key Laboratory of Vector Insects, College of Life Sciences, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing, China

- 2Guangdong Laboratory for Lingnan Modern Agriculture, Guangzhou, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Bio-Pesticide Innovation and Application of Guangdong Province, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China

- 4Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Suez Canal University, Ismailia, Egypt

- 5Subtropical Insects and Horticulture Research Unit, Agricultural Research Service, Unite States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Fort Pierce, FL, United States

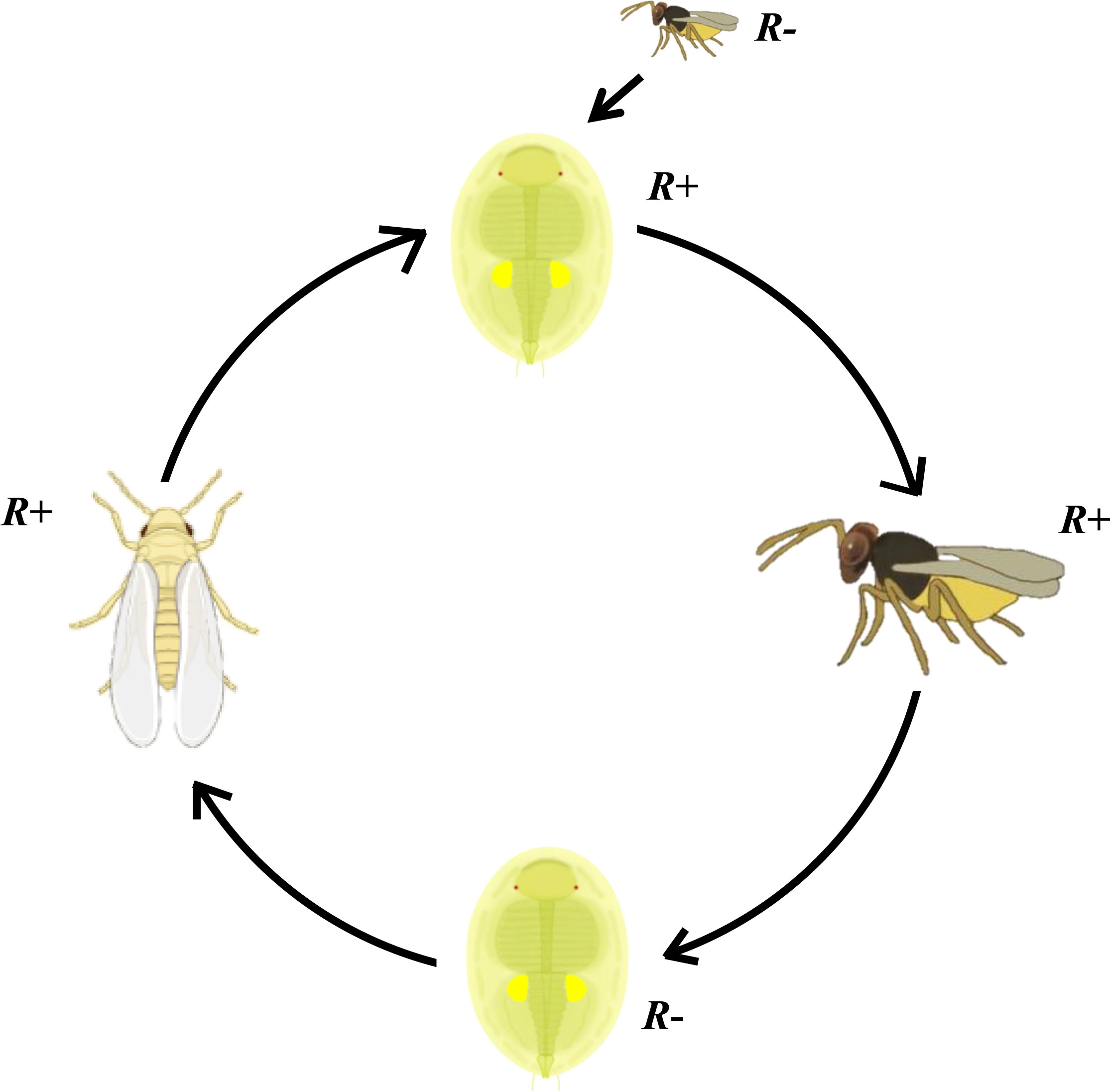

Intracellular bacterial endosymbionts of arthropods are mainly transmitted vertically from mother to offspring, but phylogenetically distant insect hosts often harbor identical endosymbionts, indicating that horizontal transmission from one species to another occurs in nature. Here, we investigated the parasitoid Encarsia formosa-mediated horizontal transmission of the endosymbiont Rickettsia between different populations of whitefly Bemisia tabaci MEAM1. Rickettsia was successfully transmitted from the positive MEAM1 nymphs (R+) into E. formosa and retained at least for 48 h in E. formosa adults. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) visualization results revealed that the ovipositors, mouthparts, and digestive tract of parasitoid adults get contaminated with Rickettsia. Random non-lethal probing of Rickettisia-negative (R−) MEAM1 nymphs by these Rickettsia-carrying E. formosa resulted in newly infected MEAM1 nymphs, and the vertical transmission of Rickettsia within the recipient females can remain at least up to F3 generation. Further phylogenetic analyses revealed that Rickettsia had high fidelity during the horizontal transmission in whiteflies and parasitoids. Our findings may help to explain why Rickettsia bacteria are so abundant in arthropods and suggest that, in some insect species that shared the same parasitoids, Rickettsia may be maintained in populations by horizontal transmission.

1. Introduction

Intracellular bacteria often live with innumerable species of arthropods including insects. Interaction between bacteria and their hosts may be parasitic, symbiotic, or neutral (Bourtzis and Miller, 2006). These endosymbionts can broadly be divided into primary (obligate) endosymbionts and secondary (facultative) endosymbionts (Bing et al., 2013a; Bing et al., 2013b; Gnankine et al., 2013). The primary endosymbionts (such as Portiera aleyrodidarum in whiteflies) can supply essential nutrients under limited or unbalanced hosts’ diets thus essential for host survival (Douglas, 1998; Baumann, 2005). Secondary endosymbionts on the other hand are not essential for host survival; however, recent studies have revealed that they play other important roles in ecological and evolutionary phenomena, such as manipulating reproduction of their hosts (Segoli et al., 2013; Baldini et al., 2014; Staudacher et al., 2017; Thongprem et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Candasamy et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022). Normally, many arthropod individuals harbor more than one species of endosymbionts, and they are mainly inherited vertically from mother to offspring with high fidelity, which is higher than 99.0% homology between the generations (Karut et al., 2020; Shan et al., 2020). However, their intra- or interspecifically horizontal transmission can also occur (Chiel et al., 2009; Oliver et al., 2010; Li et al., 2017a; Liu et al., 2020b).

The routes and mechanisms driving horizontal transmission of bacterial endosymbionts have been studied extensively in the last two decades (Woodbury et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Ilinsky et al., 2022). Several studies reported parasitoid-mediated horizontal transmission among phylogenetically distant species (Duron et al., 2010; Gehrer and Vorburger, 2012; Ahmed et al., 2015). For instance, Arsenophonus-uninfected parasitoids can acquire endosymbiont infection while developing inside an infected host (Duron et al., 2010). Similarly, the parasitoid Eretmocerus furuhashii may also serve as a phoretic vector, spreading Wolbachia from positive whitefly Bemisia tabaci AsiaII7 to its negative populations (Ahmed et al., 2015). Hamiltonella defensa and Regiella insecticola endosymbionts can be efficiently transmitted when a parasitoid sequentially stabs an infected and then an uninfected aphid (Gehrer and Vorburger, 2012). Here, we report, for the first time, the efficient phoretic transfer of Rickettsia from infected to uninfected members of whitefly B. tabaci MEAM1 cryptic species (Middle East Asia Minor 1), by one of the dominant parasitoid species, Encarsia formosa.

The whitefly B. tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) is a small sucking agricultural pest that consists of more than 30 morphologically indistinguishable cryptic species (Dinsdale et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2013). This whitefly pest can cause severe economic losses due to its ability to directly suck phloem sap from plants, indirectly secrete honeydew leading to sooty mold development, and, most importantly, transmit numerous plant viruses (Jones, 2003; Cuthbertson and Vänninen, 2015). B. tabaci harbors various bacterial endosymbionts, including Arsenophonus, Cardinium, Hamiltonella, Rickettsia, and Wolbachia, and among them (Lv et al., 2021), Rickettsia could modify host biology and manipulate the host’s reproduction to enhance its spread (Gottlieb et al., 2006; Moran et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2021). Recent reports revealed two localized distribution patterns of Rickettsia inside the whitefly body, “scattered” and “confined” (Gottlieb et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2018), with scattered patterns that might be contributing to the horizontal transmission of Rickettsia (Chiel et al., 2009; Caspi-Fluger et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2016). To date, biological control using parasitoids plays a vital role in the sustainable control of insect pests, including whitefly. E. formosa Gahan (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) is one of the most commonly used parasitoids in commercial whitefly control worldwide. It is a primary, solitary, thelytokous endoparasitoid that oviposits right inside the nymph of its host but penetrates whitefly nymphs with its ovipositor and mouth parts to examine them first before feeding or laying eggs (Lenteren et al., 1996; Gerling et al., 2001; Bacci et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011; Sugiyama et al., 2011).

In the current study, we used polymerase chain reaction (PCR), quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to demonstrate the intraspecific horizontal transmission of Rickettsia from infected to uninfected whitefly individuals through parasitoid E. formosa. We anticipate that Rickettsia, because of horizontal transmission, could modify the biology of the transinfected host individual and might enhance its pestiferous nature.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Whiteflies and parasitoids

Two populations of B. tabaci (MEAM1 cryptic species) were used for the study: Rickettsia-positive (R+) and Rickettsia-negative (R−) (Liu et al., 2020a). Both populations were then reared for at least 10 generations on cotton plants (Gossypium hirsutum L. var. Lumianyan no. 32) under standard laboratory conditions of 26 ± 2°C, 60% RH, and a photoperiod of 14:10 (L:D) h. Meanwhile, in order to ensure the purity of the two populations during experiments, approximately 100 adult whiteflies were selected to check the biotype and presence/absence of Rickettsia every month (Qiu et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2018).

Parasitoid E. formosa was initially collected from parasitized B. tabaci on tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) in the Institute of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences. The previous studies have revealed that this E. formosa strain is stably infected with Wolbachia (Fan, 2013). For further experimental study, two separate parasitoid cultures were established, one with Rickettsia-positive MEAM1 nymphs and the other with Rickettsia-negative MEAM1 nymphs fed on cotton plants. Both parasitoid cultures were then maintained on the different host species for many generations under ambient conditions [26 ± 2°C, 60% RH, and a 14:10 (L/D) h photoperiod].

2.2. PCR detection of endosymbionts in parasitoids

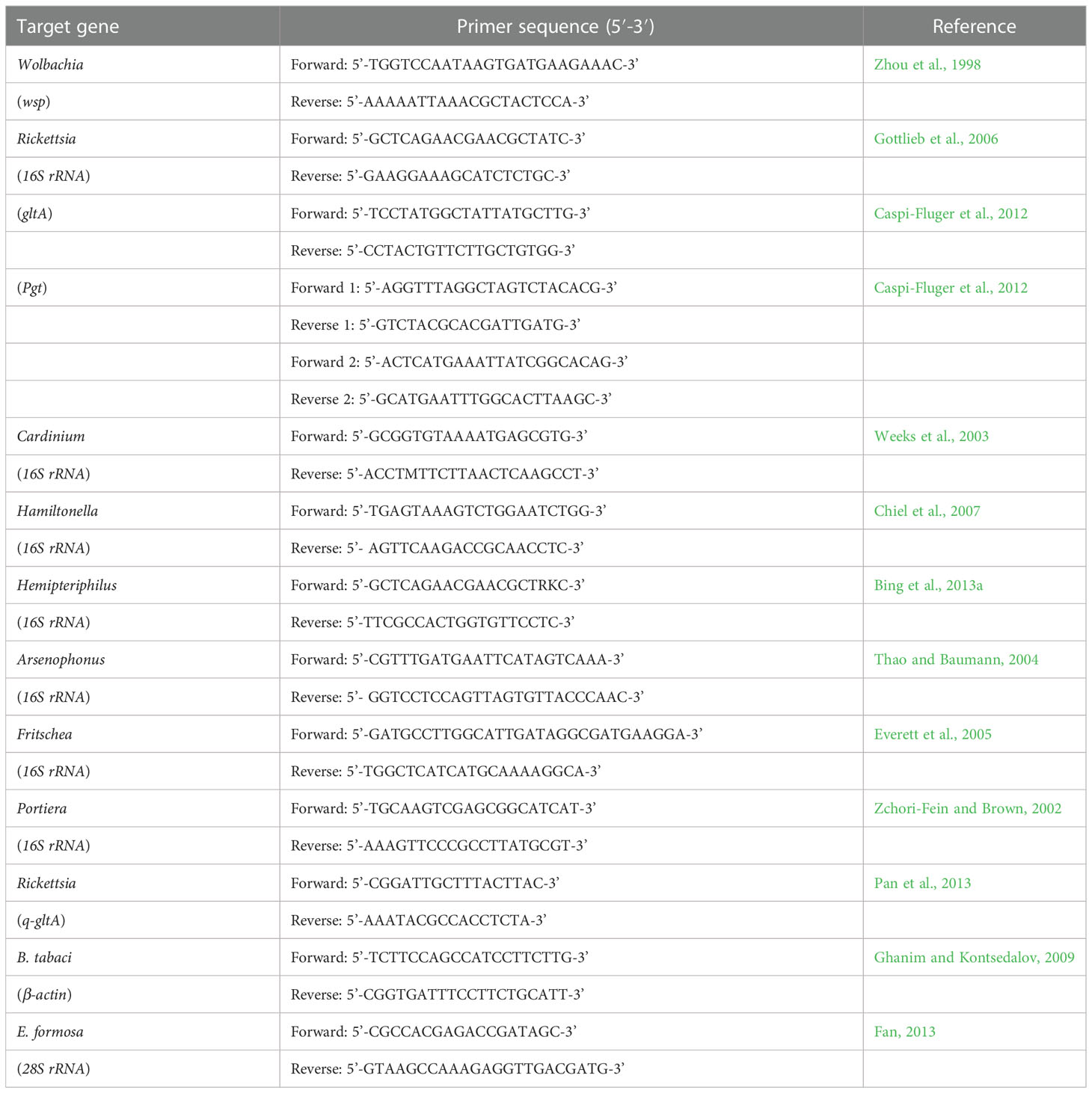

Approximately 90 parasitoid adults that emerged from Rickettsia-negative MEAM1 nymphs were randomly selected for the testing of endosymbionts (Wolbachia, Rickettsia, Cardinium, Hamiltonella, Hemipteriphilus, Arsenophonus, Fritschea, and Portiera). Total DNA was extracted from a single parasitoid following the method of Ahmed et al. (2010), which tested 90 individuals. All PCR reactions were run in a 25-μl buffer containing 1 μl of the template DNA lysate, 1 μl of each primer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 mM for each dNTP, and 1 unit of DNA Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Guangzhou, China) (Shi et al., 2018). The genus-specific primers used in this study are shown in Table 1. The remainder of amplified PCR products were then sent to the Beijing Institute (BGI) for sequencing after expected bands were visible on a 1.5% agarose gel containing Gold-View colorant. In order to confirm the specificity of the detection, the DNA of the endosymbiont Wolbachia was used as the positive control, and ddH2O was used as the negative control.

2.3. Rickettsia transmission from R+ whiteflies to parasitoids

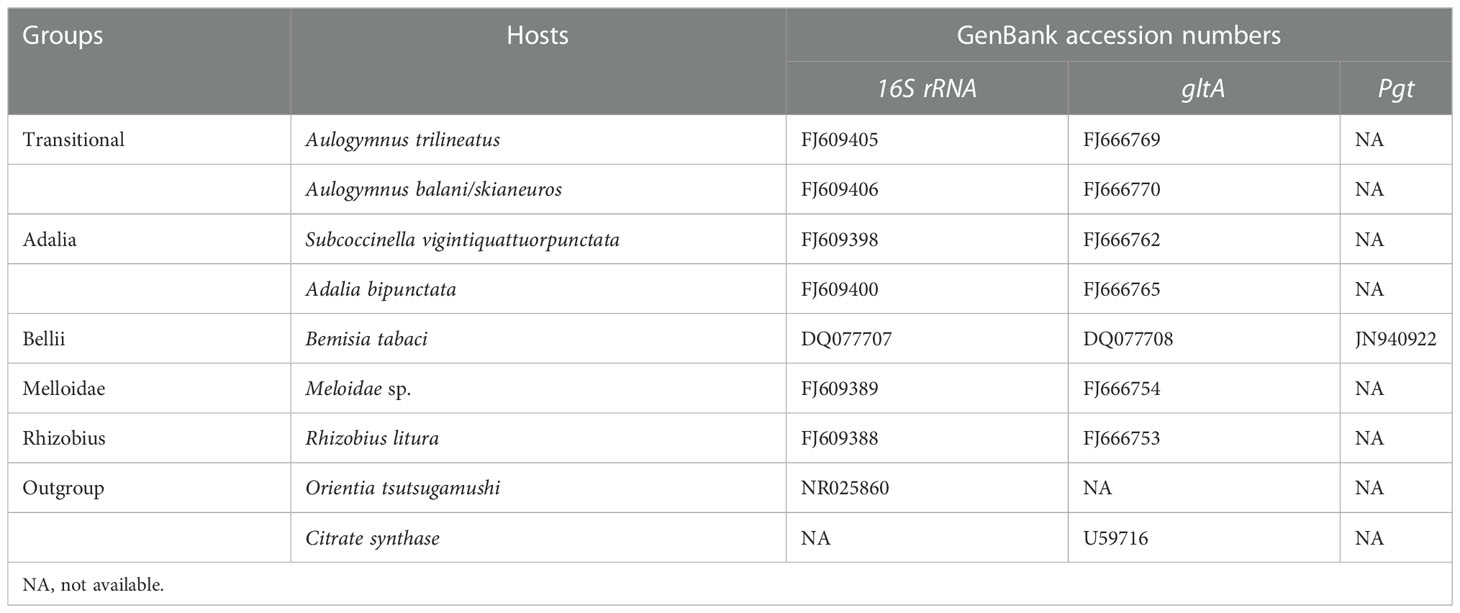

To study whether Rickettsia could be infected in the parasitoid E. formosa, 30 newly emerged parasitoid adults were collected from the R+ MEAM1 nymphs while the other 30 newly emerged parasitoids were collected from the R− MEAM1 hosts (this was treated as one experimental replicate), and three replicates were performed. They were examined for the presence of Rickettsia using the Rickettsia-specific primers listed in Table 1 (16S rRNA, gltA, and Pgt) (Gottlieb et al., 2006; Caspi-Fluger et al., 2012). The total DNA samples were extracted using a TIANamp Genomic DNA kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China), whereas the diagnostic PCR, and the sequencing of DNA fragments were performed with essentially the same methods as described above. The PCR detection included positive (Wolbachia) and negative (ddH2O) controls.

2.4. Quantitative and FISH detection of Rickettsia in parasitoids

qPCR was used to detect the relative titers of Rickettsia in the different tissues of E. formosa, and the 28S rRNA gene of E. formosa was used as the housekeeping gene. The q-gltA gene of Rickettsia and the 28S rRNA gene of E. formosa qPCR detection are shown in Table 1. Approximately 30 newly emerged parasitoid adults from R+ MEAM1 nymphs were dissected under the stereomicroscope, including head, thorax, and abdomen, and divided into three repeats for testing. Amplifications were performed using Thunderbird SYBR Green PCR mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). The cycling conditions were as follows: 5 min activation at 95°C, 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and finally 30 s at 72°C (Ghanim and Kontsedalov, 2009). A non-template negative control was included for each primer set to check for primer dimers and contamination.

To further determine the Rickettsia localization in E. formosa, parasitoid adults (age, 5–7 days) that developed from the R+ MEAM1 nymphs were randomly selected and put in Carnoy’s fixative (chloroform:ethanol:acetic acid = 6:3:1) for FISH. FISH detections were performed with the Rickettsia-specific 16S rRNA gene probe (Rb1-Cy3:5’-Cy3-TCCACGTCGCCGTCTTGC-3’), as the method described by Sakurai et al. (2005) and Gottlieb et al. (2006). Following this, stained parasitoid samples were mounted and observed under a Nikon eclipse Ti-U inverted microscope. The specificity of detection was confirmed using a no-probe control.

2.5. Persistence of Rickettsia in parasitoids

In order to monitor the persistence of Rickettsia in E. formosa, newly emerged parasitoid adults (considered F1 generation) that were collected from the R+ MEAM1 nymphs were put into a 5 cm × 1.5 cm (length × diameter) glass tube sealed with gauze. The parasitoids were then fed on 20% honey water using filter paper at 0, 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, and 48 h, respectively; 30 individuals were ground together in each replicate for qPCR; and each stage qPCR detection was repeated three times. Afterwards, all parasitoid adults were captured again and stored into a refrigerator at −80°C, and the total DNA samples were extracted using a TIANamp Genomic DNA kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The 28S rRNA gene of E. Formosa was used as the housekeeping gene, whereas Rickettsia qPCR detection was performed with essentially the same methods, as described previously.

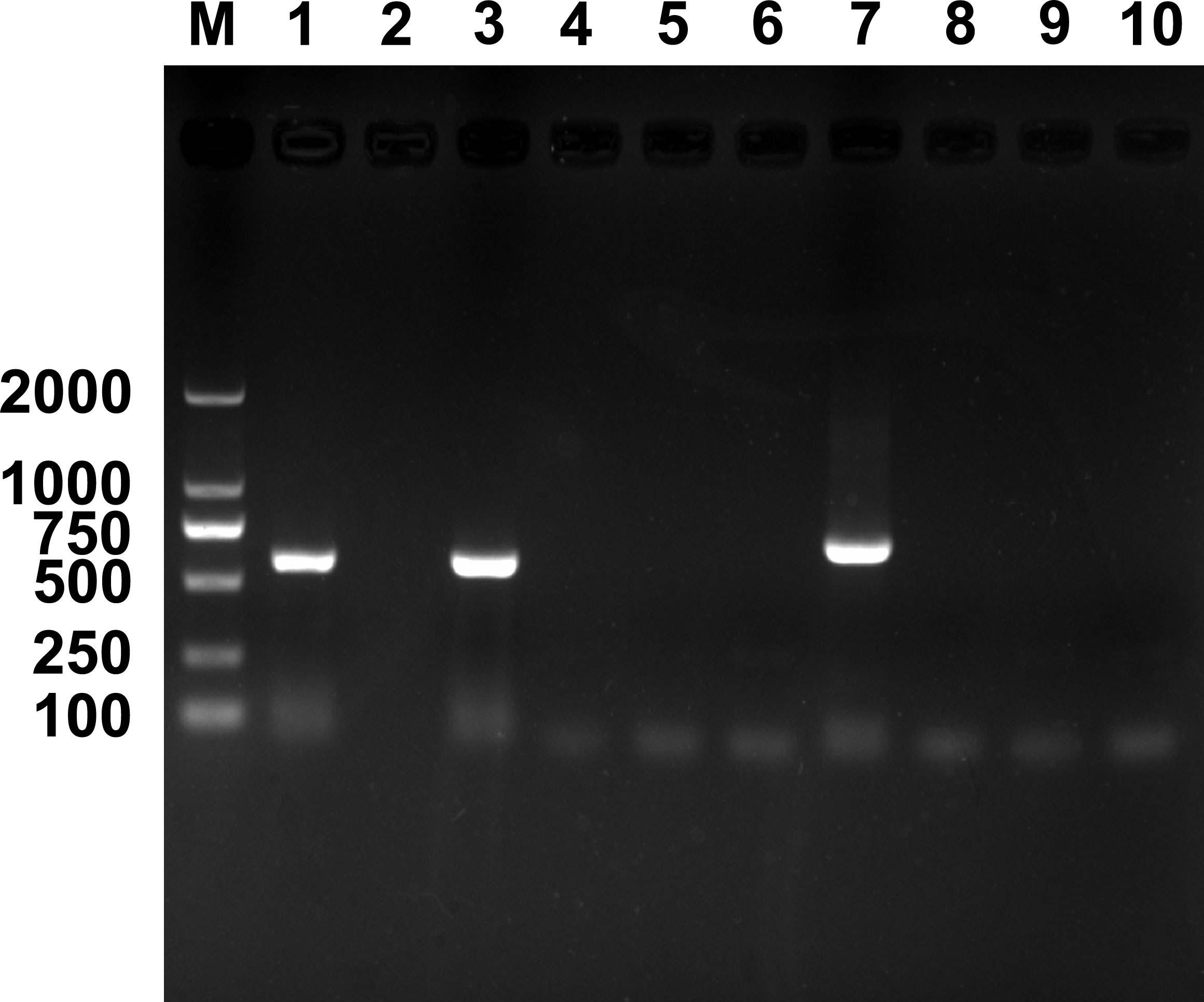

2.6. Rickettsia transmission from parasitoids to R− whiteflies and its vertical transmission in whiteflies

In the laboratory, approximately 50 pairs of R− MEAM1 adults were released into a separate leaf cage (6 cm diameter × 4 cm height) to reproduce on clean cotton leaves for 24 h, with clips subsequently fixed to them to prevent whiteflies from escaping. When the progeny from these adults developed to third instar nymphs, which is the stage preferred by E. formosa parasitoids, 160 nymphs were randomly selected and the remaining ones were removed. Afterwards, eight parasitoid adults (age, 2–3 days) that developed from R+ MEAM1 nymphs were introduced into the cages to probe and feed on these third instar R− MEAM1 nymphs for 8 h, and the probing behavior of the parasitoids was observed under a stereomicroscope, which was treated as one replicate and each experiment included 20 parallel replicates (20 × 160 = 3,200 whitefly nymphs). When the survivor R− MEAM1 nymphs developed to adults (the average proportion of such samples was 9.85 ± 0.47%), 30 newly emerged adults were collected into a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube for DNA extraction and Rickettsia PCR detection. The DNA of endosymbiont Portiera was used as a positive control and ddH2O was used as a negative control to eliminate possible confounding variables, and the experiment was repeated three times.

Another group of newly emerged whitefly adults, which developed from the nymphs of Rickettsia-carrying parasitoids that were non-lethally probed or fed on, was used to determine whether Rickettsia was vertically transmitted between whitefly generations. About 20 pairs of these whitefly adults were introduced into a leaf cage containing cotton leaves and were given 24 h to mate and oviposit before removal, and the newly emerged F1 adults were used to produce the F2 generation and then the F3 generation. The Rickettsia PCR detection procedure was the same as above. The β-actin gene of B. tabaci was used as the housekeeping gene (Ghanim and Kontsedalov, 2009); the experiment was repeated three times.

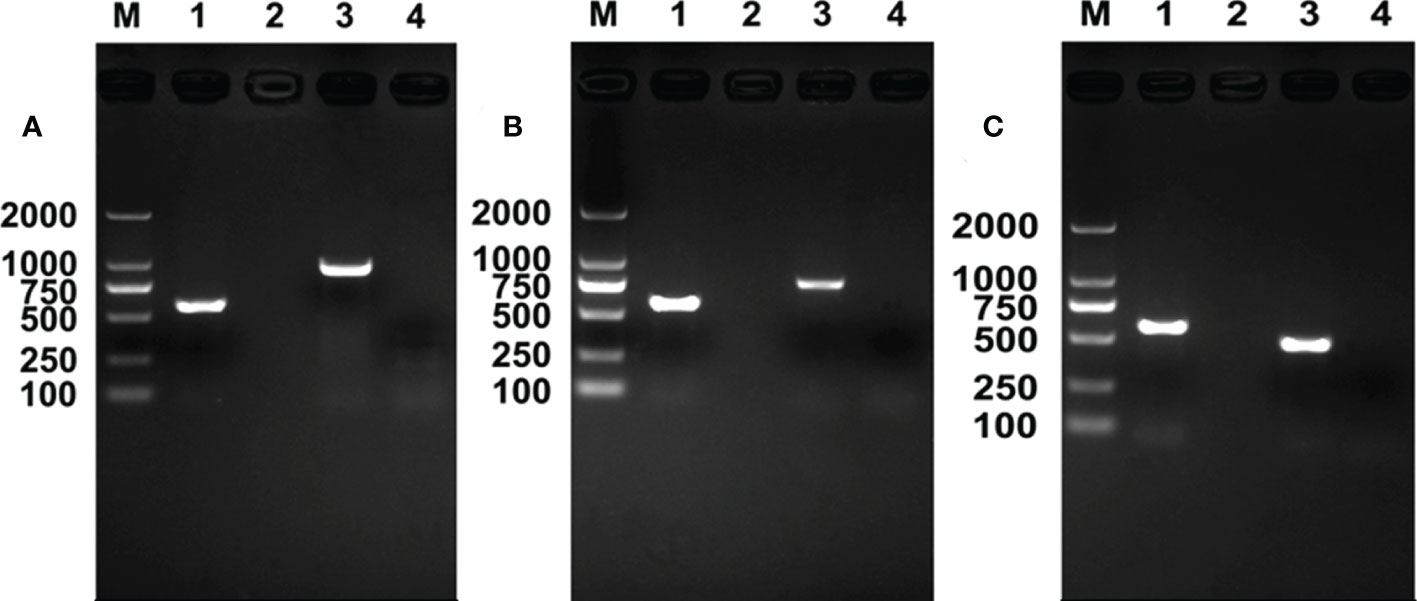

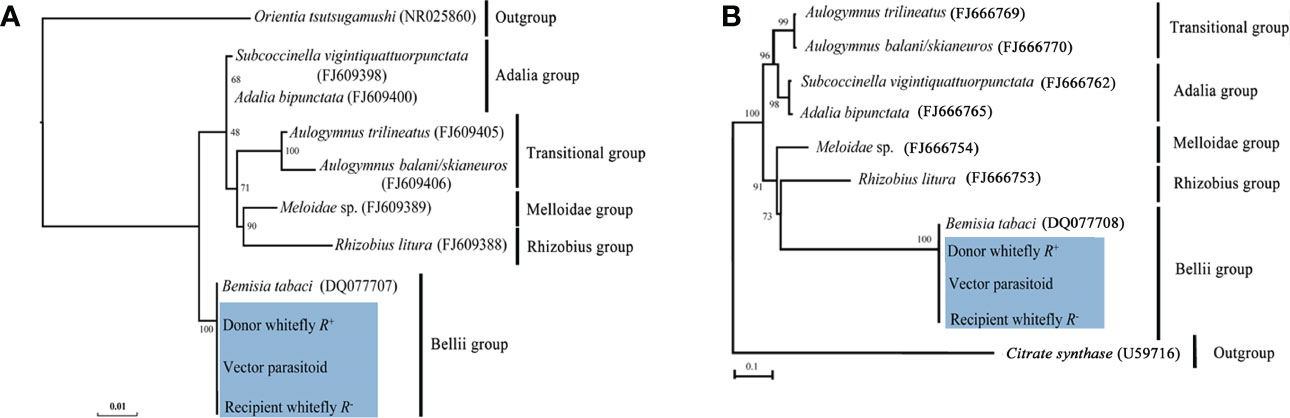

2.7. Phylogenetic analysis of Rickettsia in whiteflies and parasitoids

The homology of Rickettsia endosymbionts in positive donor MEAM1, negative recipient MEAM1, and the parasitoid vector E. formosa was phylogenetically analyzed. The 16S rRNA, gltA, and pgt gene sequences are listed in Table 2 and were edited and aligned using Lasergene v7.1 (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, WI). Two phylogenetic trees of Rickettsia were conducted based on the 16S RNA and gltA genes; meanwhile, eight 16S rRNA and eight gltA sequences of Rickettsia from different insect hosts were selected as reference for homologous analysis in the GenBank database using basic local alignment search tools. Bayesian information criterion was used to select the best model and partitioning scheme in PartitionFinder v. 1.0.1 (Lanfear et al., 2012). Finally, phylogenetic trees of Rickettsia were generated by IQ-TREE v1.6.8 using the TIM3e+I and K3Pu+F+R2 model based on the maximum likelihood (ML) method with 1,000 non-parametric bootstrap replications in RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006).

2.8. Statistical analyses

A Bio-Rad machine (American) and the accompanying software (Bio Rad CFX Manager) were used for qPCR data normalization, and the relative titers of Rickettsia in different treatments were calculated using the method of 2−ΔΔct. All dates, such as acquisition and persistence of Rickettsia in parasitoids, and vertical transmission of Rickettsia in recipient R− whiteflies, were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and means were compared using the Duncan’s test (SPSS 17.0) at p < 0.01. All figures were drawn with Sigmaplot 10.0.

3. Results

3.1. Detection of the endosymbionts in parasitoids

Results of PCR detection revealed that two endosymbionts, Hemipteriphilus (16S rRNA gene) and Wolbachia (wsp gene), were present in the parasitoid E. formosa (Figure 1), and their infection prevalence frequencies were 100% (90/90 in total). However, Rickettsia was absent in E. formosa (0/90 in total) (Figure S1).

Figure 1 PCR detection of endosymbionts in Encarsia formosa that emerged from Rickettsia-negative B tabaci MEAM1 nymphs. M, DNA marker, from top 2,000, 1,000, 750, 500, 250, and 100 bp; lanes 1–10 are positive control (Wolbachia, wsp gene), negative control (ddH2O), Wolbachia, Rickettsia, Cardinium, Hamiltonella, Hemipteriphilus, Arsenophonus, Fritschea, and Portiera.

3.2. Rickettsia transmission from R+ whiteflies to parasitoids

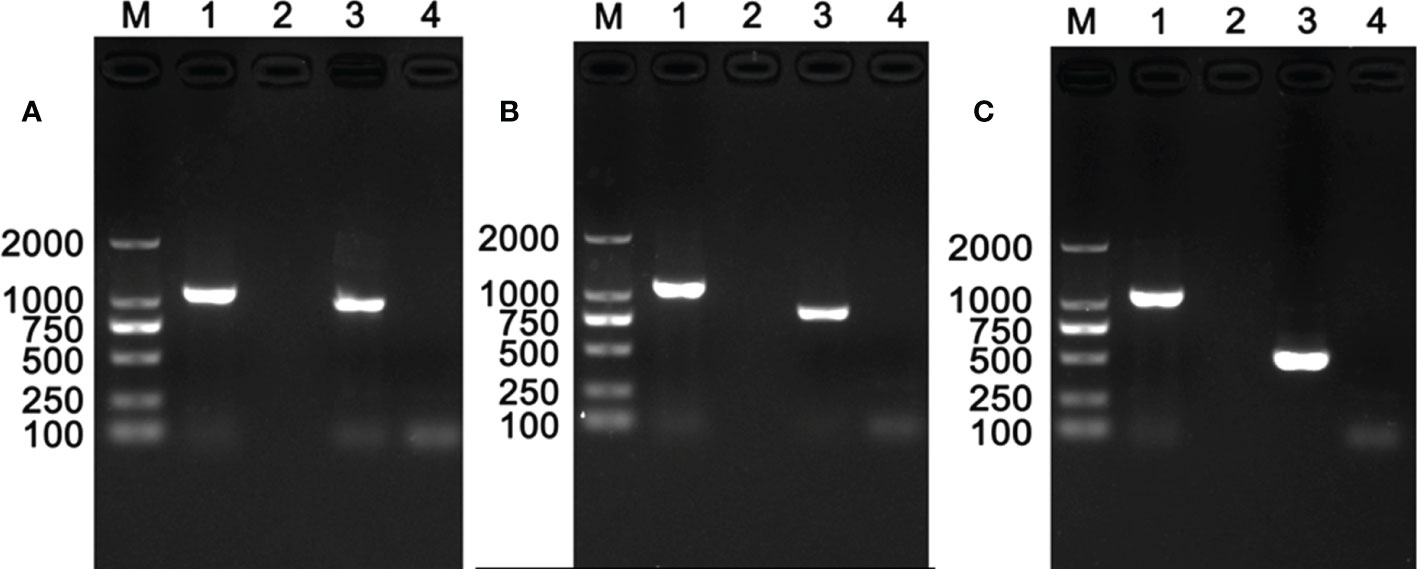

Using 16S rRNA gene, gltA gene, and Pgt gene, results of Rickettsia PCR detection revealed that, during the development of E. formosa in R+ MEAM1 nymphs, Rickettsia was successfully transmitted from the whitefly host into the parasitoid (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Rickettsia PCR detection in Encarsia formosa adults. M, DNA marker, from top 2,000, 1,000, 750, 500, 250, and 100 bp; lane 1, positive control (Wolbachia, wsp gene); lane 2, negative control (ddH2O); lane 3, E formosa that emerged from Rickettsia-positive populations; lane 4, E formosa that emerged from Rickettsia-negative populations. (A) Rickettsia 16S rRNA gene; (B) Rickettsia gltA gene; (C) Rickettsia Pgt gene.

3.3. Quantitative and FISH detection of Rickettsia in parasitoids

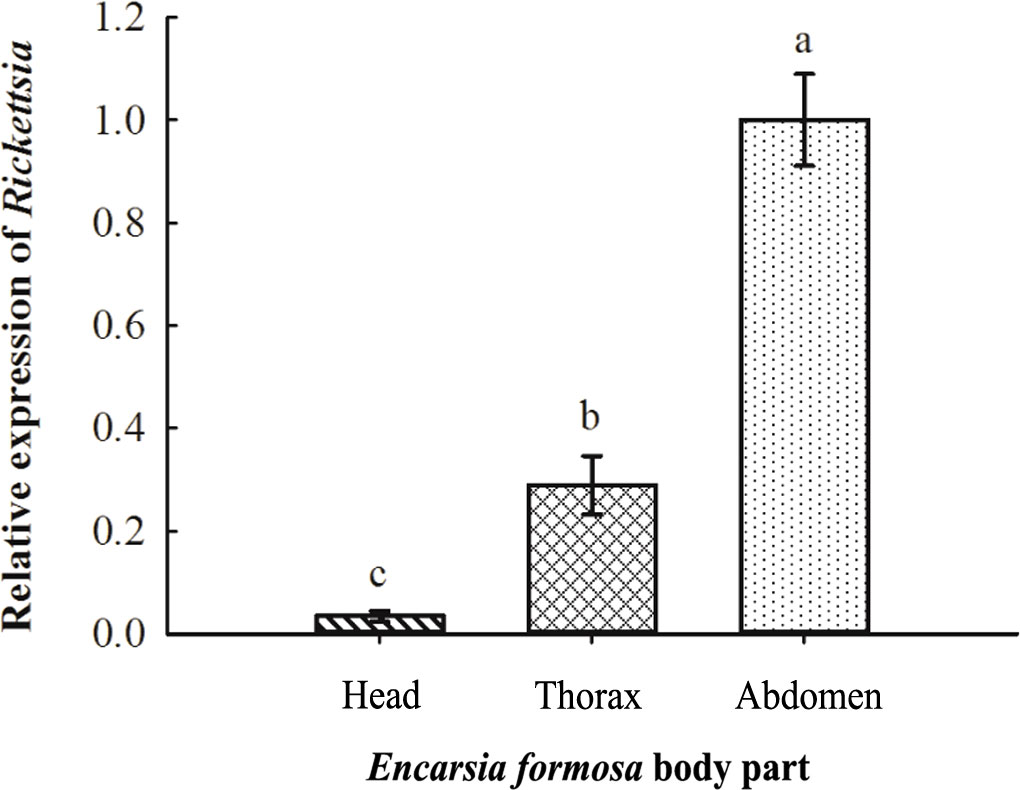

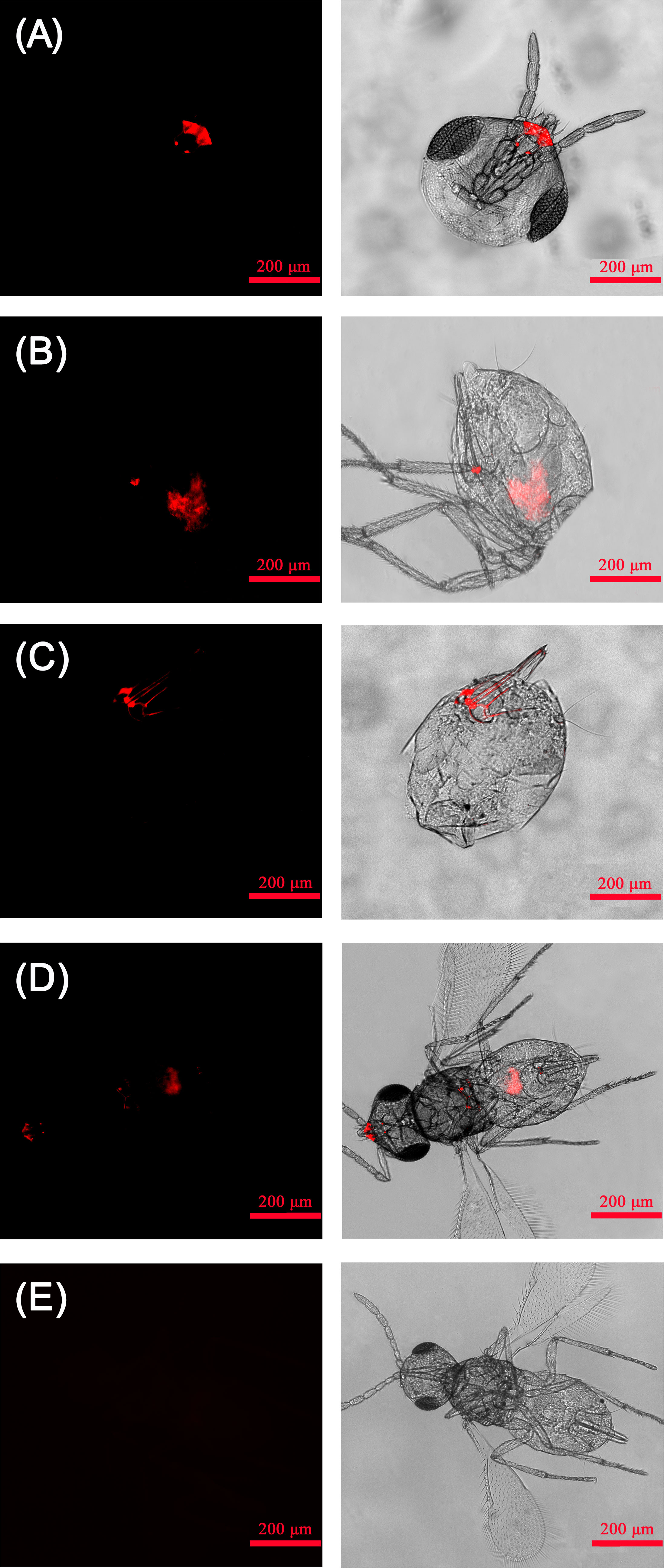

The relative titers of Rickettsia in different tissues of E. formosa were examined by using qPCR. Results showed that the parasitoid’s head, thorax, and abdomen were all infected with Rickettsia. Meanwhile, the titer of Rickettsia was highest in the abdomen (F2, 6 = 18.563, p < 0.01) (Figure 3). Results of FISH revealed that Rickettsia was mainly distributed in the mouthparts at the head, the ovipositor at the abdomen, the digestive tract of the abdomen, and the thorax. No specific FISH signal was observed in the head, thorax, and abdomen of negative control, i.e., the E. formosa individuals developed from R− whitefly hosts (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Acquisition of Rickettsia in the different tissues of Encarsia formosa. The column and error bars represent the fold change (titer) in mean ± SE (n = 3). The different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between different parts according to Duncan’s test (one-way ANOVA analysis, p < 0.01).

Figure 4 Localization of Rickettsia in adult Encarsia formosa parasitoids. (A) Rickettsia localized in the parasitoid mouthparts; (B) Rickettsia localized in the parasitoid digestive tract; (C) Rickettsia localized in the parasitoid ovipositors; (D) Rickettsia localized in the parasitoid head, thorax, and abdomen; (E) negative control-E. formosa parasitoid developed from Rickettsia-negative whitefly host. Left panels: fluorescence in dark field; right panels: fluorescence in bright field.

3.4. Persistence of Rickettsia in parasitoids

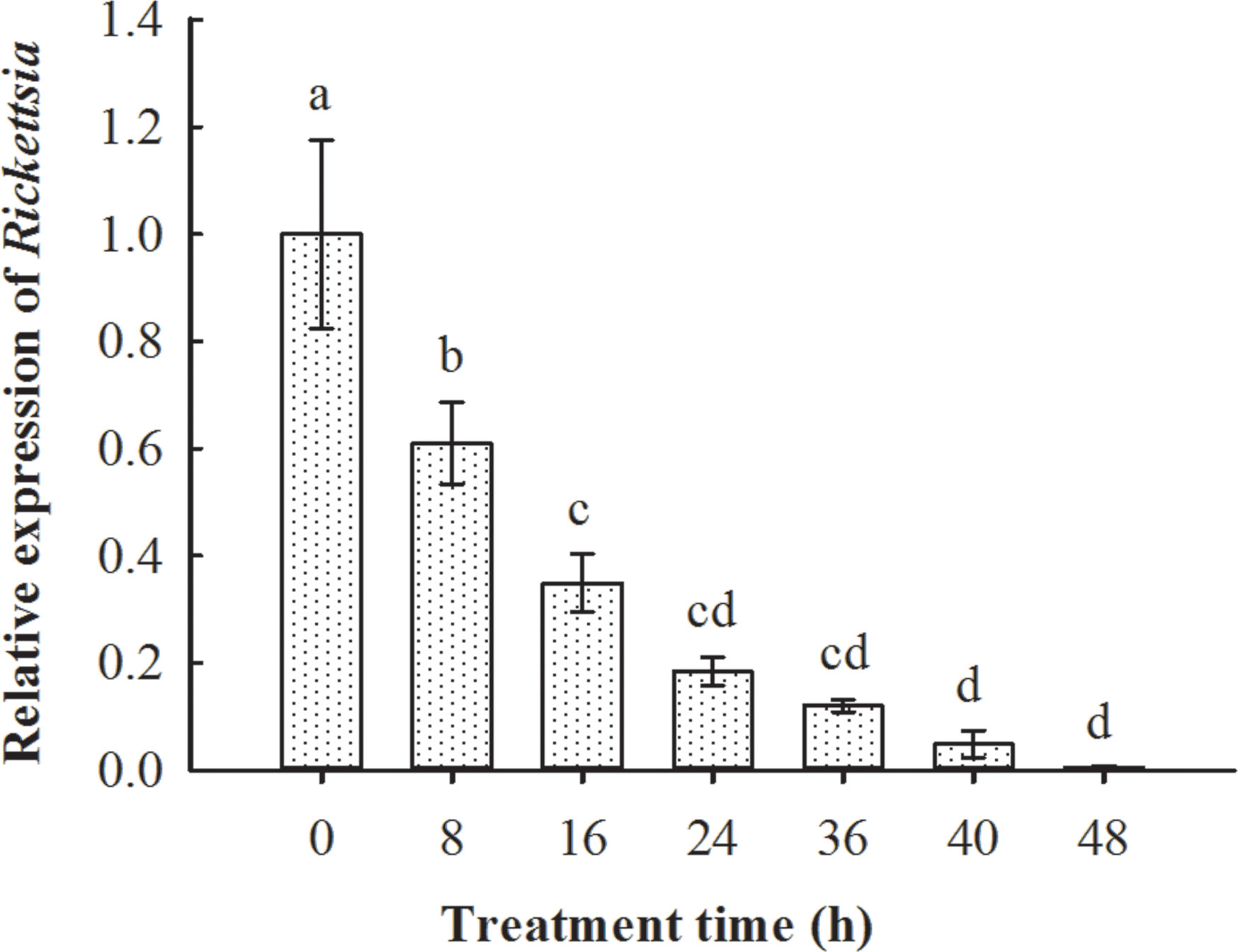

The qPCR results suggested that, after the emergence of parasitoid adults from whitefly hosts, they are infected with Rickettsia. Rickettsia was retained in the following 48 h, although the titer was gradually reduced (F6, 14 = 22.103, p < 0.01; Figure 5).

Figure 5 Persistence of Rickettsia in Encarsia formosa parasitoids that emerged from Rickettsia-positive B tabaci MEAM1 nymphs. The column and error bars represent the fold change (titer) in mean ± SE (n = 3). The different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between different treatment times according to Duncan’s test (one-way ANOVA analysis, p < 0.01).

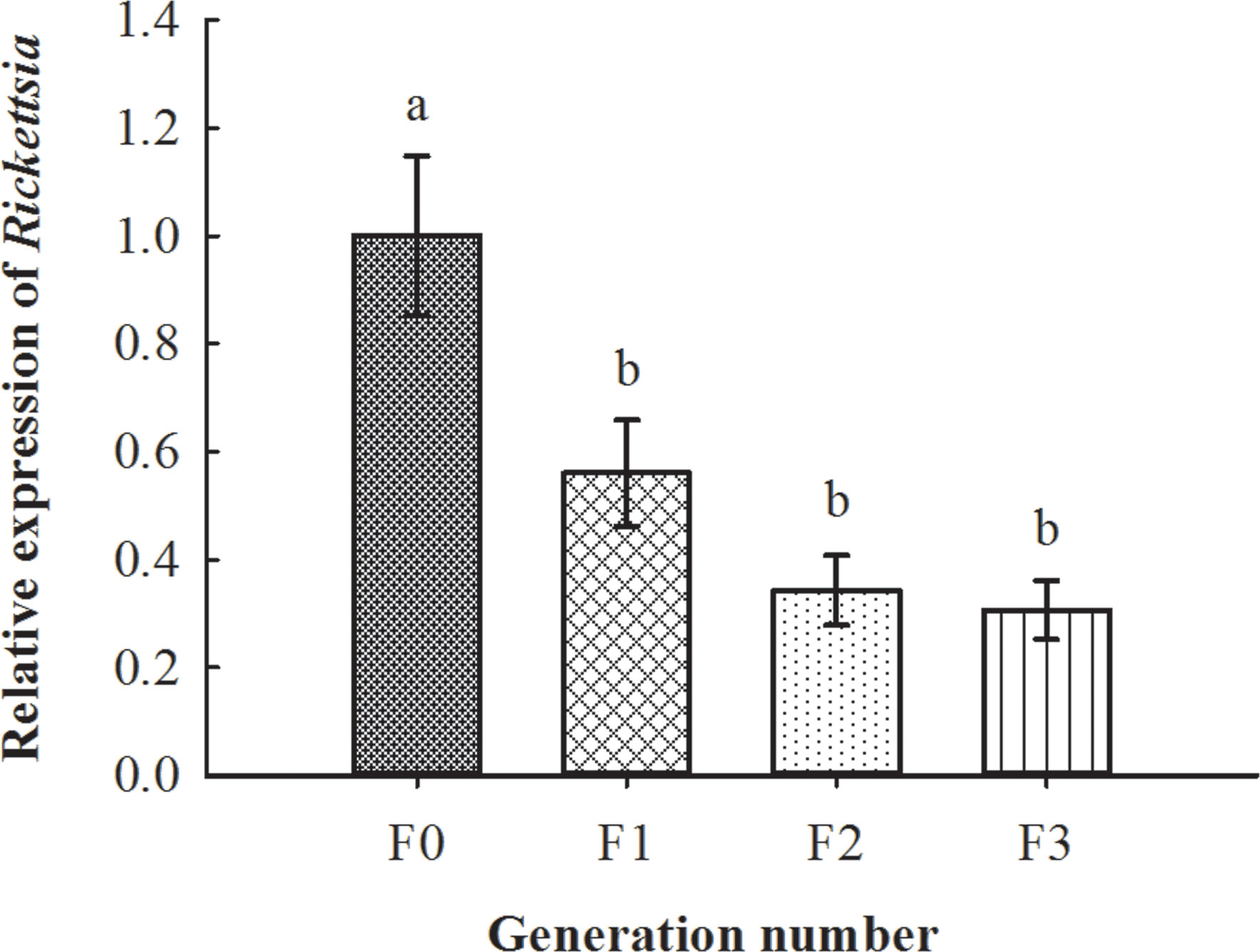

3.5. Rickettsia transmission from parasitoids to R− whiteflies and its vertical transmission

After the recipient MEAM1 nymphs (R−) were probed non-lethally and fed on by donor E. formosa (R+) (i.e., vector parasitoids that previously developed from R+ MEAM1 nymphs), PCR results demonstrated that the survived whitefly adults were infected with Rickettsia (Figure 6). Further qPCR detections showed that Rickettsia could vertically transmit up to F3 progenies of the recipient R− whiteflies (F3, 8 = 9.642, p < 0.01; Figure 7).

Figure 6 Rickettsia detection in recipient negative B tabaci MEAM1 nymphs. M, DNA marker, from top 2,000, 1,000, 750, 500, 250, and 100 bp; lane 1, positive control (Portiera, 16S rRNA gene); lane 2, negative control (ddH2O); lane 3, surviving recipient Rickettsia-negative populations by parasitoids’ non-lethal probing and feeding; lane 4, Rickettsia-negative populations. (A) Rickettsia 16S rRNA gene; (B) Rickettsia gltA gene; (C) Rickettsia Pgt gene.

Figure 7 Vertical transmission situation of Rickettsia in recipient negative B tabaci MEAM1 nymphs. The column and error bars represent the fold change (titer) in mean ± SE (n = 3). The different letters above the bars indicate significant differences between different generations according to Duncan’s test (one-way ANOVA analysis, p < 0.01).

3.6. Phylogenetic analysis of Rickettsia in whiteflies and parasitoids

Results of the phylogenetic analysis revealed that horizontal transmission of Rickettsia in our study had high fidelity (Figure S2) between the Rickettsia donor and recipient populations of MEAM1 and the vector parasitoid E. formosa, and all the Rickettsia were clustered into one branch belonging to the Bellii group based on their 16S rRNA and gltA gene sequences (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Phylogenetic analysis of Rickettsia in different B tabaci MEAM1 populations and Encarsia formosa parasitoids. (A) 16S rRNA gene: Orientia tsutsugamushi was used as an outgroup; (B) gltA gene: Citrate synthase was used as an outgroup. The phylogenetic tree was constructed and analyzed by maximum likelihood (ML) method using 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Numbers at the nodes indicate the percentages of reliability of each branch of the tree. Branch length is drawn proportional to the estimated sequence divergence. Blue shadow part showed the different MEAM1 populations and parasitoids. “Donor whitefly R+” represented donor Rickettsia-positive MEAM1; “Vector parasitoid” represented Encarsia formosa; “Recipient whitefly R−” represented recipient Rickettsia-negative MEAM1. They were all clustered into one branch within the Bellii group.

4. Discussion

There is growing evidence for the inter- and intra-specific horizontal transmission of endosymbionts among arthropod species revealing taxonomically far species carrying identical strains of endosymbionts (Ahmed et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2019; Karut et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020). Furthermore, transmission via parasitoids or other ecological interactions has long been proposed to mediate the horizontal transfer of endosymbionts from one species to another (Ahmed et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017a; Li et al., 2017b).

E. formosa is a dominant endoparasitoid of whitefly, and its endosymbionts have been widely studied (Zchori-Fein et al., 2001; Li et al., 2011; Xue et al., 2017). Previous studies have reported that the prevalence of the endosymbionts in insect hosts may vary, because it correlates with the host’s development, diet, temperature, and other abiotic factors (Toju and Fukatsu, 2011). For example, Fan (2013) found that E. formosa was infected with Wolbachia and the infection rate was 100%; Xue et al. (2017) revealed Rickettsia infection in E. formosa and Encarsia sophia, but infections of Wolbachia and Hamiltonella were only detected in E. formosa. In our current study, the infection status of Rickettisa differed within B. tabaci MEAM1 hosts; E. formosa wasps were Rickettsia infected when they were developed from R+ MEAM1 nymphs, while they were Rickettsia uninfected when they were developed from R− MEAM1 nymphs.

Our study reported transmission of endosymbionts between two trophic levels by demonstrating the efficient phoretic transfer of Rickettsia through the parasitoid E. formosa between infected and uninfected individuals of whitefly B. tabaci MEAM1. Before this study, parasitoids had been revealed to be able to vector the horizontal transmission of endosymbionts inter- and intra-specifically (Heath et al., 1999; Chiel et al., 2009; Ahmed et al., 2015). For instance, Heath et al. (1999) found that Wolbachia can be transmitted from an infected host, Drosophila simulans, to an attacking endoparasitoid, Leptopilina boulardi, and subsequently undergo diminishing vertical transmission in this new host population. Chiel et al. (2009) reported that adults of three parasitoid species, Eretmocerus emiratus, Eretmocerus eremicus, and Encarsia pergandiella, frequently acquired Rickettsia via contact with infected whiteflies, but the rate of infection declined sharply within a few days of wasps being removed from infected whiteflies. Our results are similar to the finding in a previous study by Ahmed et al. (2015) that the bacterial endosymbiont, Wolbachia, could be detected in the mouthparts and ovipositors of E. furuhashii.

Horizontal transmission of endosymbionts between hosts and parasitoids is mainly unidirectional, from the hosts to the parasitoids. However, it has been suggested that horizontal transmission from parasitoids to their hosts would be unlikely as parasitized hosts die. The mode of transmission we have described here relies on the fact that parasitoids do not always kill hosts with which they interact (Gehrer and Vorburger, 2012; Ahmed et al., 2015). As previously reported, two parasitoids, Lysiphlebus fabarum and Aphidius colemani, can transfer H. defensa and R. insecticola by sequentially stabbing infected and uninfected individuals of their host, Aphis fabae, then establishing new, heritable infections (Gehrer and Vorburger, 2012). Our previous study revealed that non-lethal probing of uninfected B. tabaci AsiaII7 nymphs by parasitoids carrying Wolbachia resulted in new stable infected B. tabaci individuals (Ahmed et al., 2015). In addition, our current study reported that Rickettsia was detected in the recipient R− MEAM1 adults, and the vertical transmission can occur up to F3 generations. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Rickettsia showed 100% fidelity in donor R+ MEAM1, vector E. formosa parasitoids, and recipient R− MEAM1, contrary to other studies, in which bacterial endosymbionts transmit horizontally with poor fidelity (Kang et al., 2003; Kikuchi and Fukatsu, 2003; Riegler et al., 2004) or failed to persist after horizontal transmisison (Chiel et al., 2009). On the other hand, our current study suggested that, when releasing E. formosa parasitoids to manage whitefly pests, the Rickettsia infection status of whitlefly should be determined. This is because E. formosa parasitoids, which have probed or fed upon the R+ MEAM1 nymphs, could change the biology of recipient R− MEAM1 nymphs and might enhance its pestiferous nature (Oliver et al., 2003; Himler et al., 2011).

The ecological dynamics of endosymbionts in their inter- and intra-specific horizontal transmission and their interactions with insect hosts and their parasitoids could be the focus of future research (Karut et al., 2020; Bao et al., 2021). In this study, we provided a novel evidence for the parasitoid-vectored horizontal transmission of bacterial endosymbiont Rickettsia between different whitefly hosts. Our current study will help understand why the endosymbionts are so ubiquitous in arthropod communities and why phylogenetically distinct arthropods often harbor closely related endosymbionts in nature (Ahmed et al., 2013; Ahmed et al., 2015; Weinert et al., 2015).

In conclusion, our current study reveals that Rickettsia endosymbionts can be picked up by the parasitoid E. formosa during their development in Rickettisia-infected (R+) MEAM1 nymphs and that it can persist in the parasitoid adult for at least 48 h following wasp emergence. During its persistence in the parasitoid, random non-lethal probing of Rickettisia uninfected (R−) MEAM1 nymphs by these Rickettsia-carrying E. formosa resulted in newly infected MEAM1 individuals (Figure 9). These findings may help to explain why Rickettsia is so abundant in arthropods and may have significant implications during parasitoid-based biological control of whitefly and for understanding the multifaceted interactions between endosymbionts, insects, and parasitoids.

Figure 9 Schematic overview of Rickettsia transmission vectored by Encarsia formosa parasitoid. Parasitoid Encarsia formosa can acquire Rickettsia from these Rickettsia-positive (R+) MEAM1 nymphs and carry it in their ovipositors. After probe checking Rickettsia-negative (R−) MEAM1 nymphs with ovipositor, if parasitized MEAM1 nymphs survive from the parasitizing check, Rickettsia can spread into the MEAM1 adults and remain at least up to F3 generation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

This article was originally designed by YL, NM, MZA, and B-LQ; YL, Z-QH, QW, JP, and Y-TZ carried out experiments; NM, CLM, and MZA also help to analyze the phenotype as well as the data; YL also participated in data analysis; YL, MZA and B-LQ wrote the paper. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Funding

The work was supported by the Guangdong Laboratory of Lingnan Modern Agriculture Project (NT2021003), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1401201), the NSFC project (31672028), and the National High-Level Talent Special Support Plan (2020) to B-LQ.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Andrew G. S. Cuthbertson (York, UK) for his critical comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Zhou, W., Rousset, F., and O'Neill, S. 1998. Phylogeny and PCR–based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 265, 509-515. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0324.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1077494/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | PCR detection of three endosymbionts, Hemipteriphilus, Wolbachia, and Rickettsia in Encarsia formosa parasitoids, related to . M, DNA marker, from top 2000, 1000, 750, 500, 250, 100bp; lane 1-90, 90 Encarsia formosa parasitoids. (A) Hemipteriphilus; (B) Wolbachia; (C) Rickettsia.

Supplementary Figure 2 | The sequence alignment of 16S rRNA and gltA genes of Rickettsia from donor, recipient B. tabaci MEAM1 and Encarsia formosa parasitoids, related to (A) 16S rRNA gene; (B) gltA gene.

References

Ahmed, M. Z., De Barro, P. J., Ren, S. X., Greeff, J. M., Qiu, B. L. (2013). Evidence for horizontal transmission of secondary endosymbionts in the Bemisia tabaci cryptic species complex. PLoS One 8, e53084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053084

Ahmed, M. Z., Li, S. J., Xue, X., Yin, X. J., Ren, S. X., Jiggins, F. M., et al. (2015). The intracellular bacterium Wolbachia uses parasitoid wasps as phoretic vectors for efficient horizontal transmission. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004672. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004672

Ahmed, M. Z., Ren, S. X., Xue, X., Li, X. X., Jin, G. H., Qiu, B. L. (2010). Prevalence of endosymbionts in Bemisia tabaci populations and their in vivo sensitivity to antibiotics. Curr. Microbiol. 61, 322–328. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9614-5

Bacci, L., Crespo, A. L., Galvan, T. L., Pereira, E. J., Picanco, M. C., Silva, G. A., et al. (2010). Toxicity of insecticides to the sweetpotato whitefly (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) and its natural enemies. Pest Manage. Sci. 63, 699–706. doi: 10.1002/ps.1393

Baldini, F., Segata, N., Pompon, J., Marcenac, P., Shaw, W. R., Dabire, R. K., et al. (2014). Evidence of natural Wolbachia infections in field populations of Anopheles gambiae. Nat. Commun. 5, 3985. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4985

Bao, X. Y., Yan, J. Y., Yao, Y. L., Wang, Y. B., Visendi, P., Seal, S., et al. (2021). Lysine provisioning by horizontally acquired genes promotes mutual dependence between whitefly and two intracellular symbionts. PloS Pathog. 17, e1010120. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010120

Baumann, P. (2005). Biology bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of plant sap-sucking insects. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59, 155–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121041

Bing, X. L., Ruan, Y. M., Rao, Q., Wang, X. W., Liu, S. S. (2013a). Diversity of secondary endosymbionts among different putative species of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Insect Sci. 20, 194–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01522.x

Bing, X. L., Yang, J., Zchori-Fein, E., Wang, X. W., Liu, S. S. (2013b). Characterization of a newly discovered symbiont of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Appl. Environ. Microb. 79, 569–575. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03030-12

Candasamy, S., Kasinathan, G., Devaraju, P., Subbarao, S. K., Rahi, M., Balakrishnan, V., et al. (2022). Studies on the fitness characteristics of wMel and wAlbB-introgressed Aedes aegypti (Pud) lines in comparison to wMel and wAlbB-transinfected Aedes aegypti (Aus) and wild type Aedes aegypti (Pud) lines. Front. Microbiol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.947857

Caspi-Fluger, A., Inbar, M., Mozes-Daube, N., Katzir, N., Portnoy, V., Belausov, E., et al. (2012). Horizontal transmission of the insect symbiont Rickettsia is plant-mediated. P. R. Soc B-Biol. Sci. 279, 1791–1796. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2095

Chiel, E., Gottlieb, Y., Zchori-Fein, E., Mozes-Daube, N., Katzir, N., Inbar, M., et al. (2007). Biotype-dependent secondary symbiont communities in sympatric populations of Bemisia tabaci. B. Entomol. Res. 97, 407–413. doi: 10.1017/S0007485307005159

Chiel, E., Zchori-Fein, E., Inbar, M., Gottlieb, Y., Adachi-Hagimori, T., Kelly, S. E., et al. (2009). Almost there: transmission routes of bacterial symbionts between trophic levels. PLoS One 4, e4767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004767

Cuthbertson, A. G. S., Vanninen, I. (2015). The importance of maintaining protected zone status against Bemisia tabaci. Insects. 6, 432–441. doi: 10.3390/insects6020432

Dinsdale, A., Cook, L., Riginos, C., Buckley, Y. M., De Barro, P. (2010). Refined global analysis of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aleyrodoidea: Aleyrodidae) mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase 1 to identify species level genetic boundaries. Ann. Entomol. Soc Am. 103, 196–208. doi: 10.1603/AN09061

Douglas, A. E. (1998). Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbioses: aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 43, 17–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.17

Duron, O., Wilkes, T. E., Hurst, G. D. D. (2010). Interspecific transmission of a male-killing bacterium on an ecological timescale. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1139–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01502.x

Everett, K. D. E., Thao, M., Horn, M., Dyszynski, G. E., Baumann, P. (2005). Novel chlamydiae in whiteflies and scale insects: endosymbionts 'Candidatus fritschea bemisiae' strain Falk and 'Candidatus fritschea eriococci' strain elm. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 55, 1581–1587. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63454-0

Fan, N. (2013). Characterization and effects of symbionts wolbachia in Encarsia Formosa (Nanjing Agricultural University).

Gehrer, L., Vorburger, C. (2012). Parasitoids as vectors of facultative bacterial endosymbionts in aphids. Biol. Lett. 8, 613–615. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0144

Gerling, D., Alomar, ,.ò., Arnò, ,. J. (2001). Biological control of Bemisia Tabaci using predators and parasitoids. Crop Prot. 20, 779–799. doi: 10.1002/ps.6958

Ghanim, M., Kontsedalov, S. (2009). Susceptibility to insecticides in the Q biotype of Bemisia tabaci is correlated with bacterial symbiont densities. Pest Manage. Sci. 65, 939–942. doi: 10.1002/ps.1795

Gnankine, O., Mouton, L., Henri, H., Terraz, G., Houndete, T., Martin, T., et al. (2013). Distribution of Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) biotypes and their associated symbiotic bacteria on host plants in West Africa. Insect Conserv. Diver. 6, 411–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4598.2012.00206.x

Gottlieb, Y., Ghanim, M., Chiel, E., Gerling, D., Portnoy, V., Steinberg, S., et al. (2006). Identification and localization of a Rickettsia sp. in Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). Appl. Environ. Microb. 72, 3646–3652. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3646-3652.2006

Gottlieb, Y., Ghanim, M., Gueguen, G., Kontsedalov, S., Vavre, F., Fleury, F., et al. (2008). Inherited intracellular ecosystem: symbiotic bacteria share bacteriocytes in whiteflies. FASEB J. 22, 2591–2599. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-101162

Heath, B. D., Butcher, R. D. J., Whitfield, W. G. F., Hubbard, S. F. (1999). Horizontal transfer of Wolbachia between phylogenetically distant insect species by a naturally occurring mechanism. Curr. Biol. 9, 313–316. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80139-0

Himler, A. G., Adachi-Hagimori, T., Bergen, J. E., Kozuch, A., Kelly, S. E., Tabashnik, B. E., et al. (2011). Rapid spread of a bacterial symbiont in an invasive whitefly is driven by fitness benefits and female bias. Science. 332, 254–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1199410

Hu, J., De Barro, P., Zhao, H., Wang, J., Nardi, F., Liu, S. S. (2011). An extensive field survey combined with a phylogenetic analysis reveals rapid and widespread invasion of two alien whiteflies in China. PLoS One 6, e16061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016061

Ilinsky, Y., Demenkova, M., Bykov, R., Bugrov, A. (2022). Narrow genetic diversity of Wolbachia symbionts in Acrididae grasshopper hosts (Insecta, orthoptera). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 853. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020853

Jones, D. R. (2003). Plant viruses transmitted by whiteflies. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 109, 195–219. doi: 10.1023/A:1022846630513

Kang, L., Ma, X., Cai, L., Liao, S., Sun, L., Zhu, H., et al. (2003). Superinfection of Laodelphax striatellus with Wolbachia from Drosophila simulans. Heredity. 90, 691–701. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800180

Karut, K., Castle, S. J., Karut, S. T., Karaca, M. M. (2020). Secondary endosymbiont diversity of Bemisia tabaci and its parasitoids. Infect. Genet. Evol. 78, 104104. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104104

Kikuchi, Y., Fukatsu, T. (2003). Diversity of Wolbachia endosymbionts in heteropteran bugs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 6082–6090. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.6082-6090.2003

Lanfear, R., Calcott, B., Ho, S. Y. W., Guindon, S. (2012). Partitionfinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1695–1701. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss020

Lee, W., Park, J., Lee, G. S., Lee, S., Akimoto, S. I. (2013). Taxonomic status of the Bemisia tabaci complex (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) and reassessment of the number of its constituent species. PLoS One 8, e63817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063817

Lenteren, J. C. V., Roermund, H. J. W. V., Sütterlin, S. (1996). Biological control of greenhouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum) with the parasitoid Encarsia formosa: how does it work? Biol. Control. 6, 1–10. doi: 10.1006/bcon.1996.0001

Li, Y. H., Ahmed, M. Z., Li, S. J., Lv, N., Shi, P. Q., Chen, X. S., et al. (2017b). Plant-mediated horizontal transmission of Rickettsia endosymbiont between different whitefly species. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93, fix138. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix138

Li, S. J., Ahmed, M. Z., Lv, N., Shi, P. Q., Wang, X. M., Huang, J. L., et al. (2017a). Plant-mediated horizontal transmission of Wolbachia between whiteflies. ISME J. 11, 1019–1028. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.164

Liu, Y., Fan, Z. Y., An, X., Shi, P. Q., Ahmed, M. Z., Qiu, B. L. (2020a). A single-pair method to screen Rickettsia-infected and uninfected whitefly Bemisia tabaci populations. J. Microbiol. Meth. 168, 105797. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.105797

Liu, Y., Fan, Z. Y., Li, Y., Peng, J., Chen, X. Y., Qiu, B. L. (2020b). Plant-mediated horizontal transmission of insect endosymbionts and their biological effects on recipients. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 57, 272–283. doi: 10.7679/j.issn.2095-1353.2020.031

Li, S. J., Xue, X., Ahmed, M. Z., Ren, S. X., Du, Y. Z., Wu, J. H., et al. (2011). Host plants and natural enemies of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in China. Insect Sci. 18, 101–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2010.01395.x

Li, T. P., Zhou, C. Y., Wang, M. K., Zha, S. S., Chen, J., Bing, X. L., et al. (2022). Endosymbionts reduce microbiome diversity and modify host metabolism and fecundity in the planthopper Sogatella furcifera. mSystems. 7, e0151621. doi: 10.1128/msystems.01516-21

Lv, N., Peng, J., Chen, X. Y., Guo, C. F., Sang, W., Wang, X. M., et al. (2021). Antagonistic interaction between male-killing and cytoplasmic incompatibility induced by Cardinium and Wolbachia in the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Insect Sci. 28, 330–346. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12793

Moran, N. A., Mccutcheon, J. P., Nakabachi, A. (2008). Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42, 165–190. doi: 10.1016/S0376-7388(00)00403-8

Oliver, K. M., Degnan, P. H., Burke, G. R., Moran, N. A. (2010). Facultative symbionts in aphids and the horizontal transfer of ecologically important traits. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 55, 247–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085305

Oliver, K. M., Russell, J. A., Moran, N. A., Hunter, M. S. (2003). Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1803–1807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0335320100

Pan, H. P., Chu, D., Liu, B. M., Xie, W., Wang, S. L., Wu, Q. J., et al. (2013). Relative amount of symbionts in insect hosts changes with host-plant adaptation and insecticide resistance. Environ. Entomol. 42, 74–78. doi: 10.1603/EN12114

Qi, L. D., Sun, J. T., Hong, X. Y., Li, Y. X. (2019). Diversity and phylogenetic analyses reveal horizontal transmission of endosymbionts between whiteflies and their parasitoids. J. Econ. Entomol. 112, 894–905. doi: 10.1093/jee/toy367

Qiu, B. L., Chen, Y. P., Liu, L., Peng, W. L., Li, X. X., Ahmed, M. Z., et al. (2009). Identification of three major Bemisia tabaci biotypes in China based on morphological and DNA polymorphisms. Prog. Nat. Sci. 19, 713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.08.013

Ren, F. R., Sun, X., Wang, T. Y., Yao, Y. L., Huang, Y. Z., Zhang, X., et al. (2020). Biotin provisioning by horizontally transferred genes from bacteria confers animal fitness benefits. ISME J. 14, 2542–2553. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-0704-5

Riegler, M., Charlat, S., Stauffer, C., Mercot, H. (2004). Wolbachia transfer from Rhagoletis cerasi to Drosophila simulans: investigating the outcomes of host-symbiont coevolution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 273–279. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.273-279.2004

Sakurai, M., Koga, R., Tsuchida, T., Meng, X. Y., Fukatsu, T. (2005). Rickettsia symbiont in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum: novel cellular tropism, effect on host fitness, and interaction with the essential symbiont Buchnera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 4069–4075. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.4069-4075.2005

Segoli, M., Stouthamer, R., Stouthamer, C. M., Rugman-Jones, P., Rosenheim, J. A. (2013). The effect of Wolbachia on the lifetime reproductive success of its insect host in the field. J. Evolution. Biol. 26, 2716–2720. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12264

Shan, H. W., Liu, Y. Q., Luan, J. B., Liu, S. S. (2020). New insights into the transovarial transmission of the symbiont Rickettsia in whiteflies. Sci. China Life Sci. 64, 1174–1186. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1801-7

Shi, P. Q., Chen, X. Y., Chen, X. S., Lv, N., Liu, Y., Qiu, B. L. (2021). Rickettsia increases its infection and spread in whitefly populations by manipulating the defense patterns of the host plant. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 97, fiab032. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiab032

Shi, P. Q., He, Z., Li, S. J., An, X., Lv, N., Ghanim, M., et al. (2016). Wolbachia has two different localization patterns in whitefly Bemisia tabaci AsiaII7 species. PloS One 11, e0162558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162558

Shi, P. Q., Wang, L., Liu, Y., An, X., Chen, X. S., Ahmed, M. Z., et al. (2018). Infection dynamics of endosymbionts reveal three novel localization patterns of Rickettsia during the development of whitefly Bemisia tabaci. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, fiy165. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy165

Stamatakis, A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 22, 2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446

Staudacher, H., Schimmel, B. C. J., Lamers, M. M., Wybouw, N., Groot, A. T., Kant, M. R. (2017). Independent effects of a herbivore's bacterial symbionts on its performance and induced plant defences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 182. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010182

Sugiyama, K., Katayama, H., Saito, T. (2011). Effect of insecticides on the mortalities of three whitefly parasitoid species Eretmocerus mundus, Eretmocerus eremicus and Encarsia formosa (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 46, 311–317. doi: 10.1007/s13355-011-0044-z

Thao, M. L., Baumann, P. (2004). Evolutionary relationships of primary prokaryotic endosymbionts of whiteflies and their hosts. Appl. Environ. Microb. 70, 3401–3406. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3401-3406.2004

Thongprem, P., Evison, S. E. F., Hurst, G. D. D., Otti, O. (2020). Transmission, tropism, and biological impacts of torix Rickettsia in the common bed bug Cimex lectularius (Hemiptera: Cimicidae). Front. Microbiol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.608763

Toju, H., Fukatsu, T. (2011). Diversity and infection prevalence of endosymbionts in natural populations of the chestnut weevil: relevance of local climate and host plants. Mol. Ecol. 20, 853–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04980.x

Wang, Q. Y., Yuan, E. L., Ling, X. Y., Zhu-Salzman, K., Guo, H. J., Ge, F., et al. (2020). An aphid facultative symbiont suppresses plant defense by manipulating aphid gene expression in salivary glands. Plant Cell Environ. 43, 2311–2322. doi: 10.1111/pce.13836

Weeks, A. R., Velten, R., Stouthamer, R. (2003). Incidence of a new sex-ratio-distorting endosymbiotic bacterium among arthropods. P. R. Soc B-Biol. Sci. 270, 1857–1865. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2425

Weinert, L. A., Araujo-Jnr, E. V., Ahmed, M. Z., Welch, J. J. (2015). The incidence of bacterial endosymbionts in terrestrial arthropods. P. R. Soc B-Biol. Sci. 282, 20150249. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0249

Woodbury, N., Moore, M., Gries, G. (2013). Horizontal transmission of the microbial symbionts Enterobacter cloacae and Mycotypha microspora to their firebrat host. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 147, 160–166. doi: 10.1111/eea.12057

Xue, Y. T., Zhang, Y. B., Zhang, Y., Zhang, G. F., Liu, H., Wan, F. H., et al. (2017). Diversity and phylogenetic affiliation of endosymbionts from Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera:Aleyrodidae) and its dominant parasitoids. Environ. Entomol. 39, 741–751. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-0858.2017.04.2

Zchori-Fein, E., Brown, J. K. (2002). Diversity of prokaryotes associated with Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius)(Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc Am. 95, 711–718. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70986-8

Zchori-Fein, E., Gottlieb, Y., Kelly, S. E., Brown, J. K., Wilson, J. M., Karr, T. L., et al. (2001). A newly discovered bacterium associated with parthenogenesis and a change in host selection behavior in parasitoid wasps. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12555–12560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221467498

Zhang, K. J., Han, X., Hong, X. Y. (2013). Various infection status and molecular evidence for horizontal transmission and recombination of Wolbachia and Cardinium among rice planthoppers and related species. Insect Sci. 20, 329–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01537.x

Keywords: Bemisia tabaci, endosymbionts, Rickettsia, Encarsia formosa, horizontal transmission

Citation: Liu Y, He Z-Q, Wen Q, Peng J, Zhou Y-T, Mandour N, McKenzie CL, Ahmed MZ and Qiu B-L (2023) Parasitoid-mediated horizontal transmission of Rickettsia between whiteflies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12:1077494. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1077494

Received: 23 October 2022; Accepted: 05 December 2022;

Published: 04 January 2023.

Edited by:

Li Zhang, University of New South Wales, AustraliaReviewed by:

Erich Loza Telleria, Charles University, CzechiaZhiqiang Lu, Northwest A&F University, China

Copyright © 2023 Liu, He, Wen, Peng, Zhou, Mandour, McKenzie, Ahmed and Qiu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bao-Li Qiu, YmFvbGlxaXVAY3FudS5lZHUuY24=

Yuan Liu1,2,3

Yuan Liu1,2,3 Jing Peng

Jing Peng Bao-Li Qiu

Bao-Li Qiu