95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. , 06 January 2023

Sec. Antibiotic Resistance and New Antimicrobial drugs

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1068840

This article is part of the Research Topic Multidrug Gram-Negative Bacilli : Current Situation and Future Perspective View all 10 articles

Background: The rapid emergence of carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) has resulted in an alarming situation worldwide. Realizing the dearth of literature on susceptibility of CRAB in genetic context in the developing region, this study was performed to determine the susceptibility profile against standard drugs/combinations and the association of in-vitro drug synergy with the prevalent molecular determinants.

Methods and findings: A total of 356 clinical isolates of A. baumannii were studied. Confirmation of the isolates was done by amplifying recA and ITS region genes. Susceptibility against standard drugs was tested by Kirby Bauer disc diffusion. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), MIC50 and MIC90 values against imipenem, meropenem, doripenem, ampicillin/sulbactam, minocycline, amikacin, polymyxin B, colistin and tigecycline was tested as per guidelines. Genes encoding enzymes classes A (blaGES, blaIMI/NMC-A, blaSME, blaKPC), B (blaIMP, blaVIM, blaNDM) and D (blaOXA-51, blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-58) were detected by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Synergy against meropenem-sulbactam and meropenem-colistin combinations was done by checkerboard MIC method. Correlation of drug synergy and carbapenemase encoding genes was statistically analyzed.

Results: Of the total, resistance above 90% was noted against gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ceftazidime, cefepime, ceftriaxone, cotrimoxazole and piperacillin/tazobactam. By MIC, resistance rates from highest to lowest was seen against imipenem 89.04% (n=317), amikacin 80.33% (n=286), meropenem 79.49% (n=283), doripenem 77.80% (n=277), ampicillin/sulbactam 71.62% (n=255), tigecycline 55.61% (n=198), minocycline 14.04% (n=50), polymyxin B 10.11% (n=36), and colistin 2.52% (n=9). CRAB was 317 (89.04%), 81.46% (n=290) were multidrug resistant and 13.48% (n=48) were extensively drug resistant. All the CRAB isolates harboured blaOXA-51 gene (100%) and 94% (n=298) blaOXA-23 gene. The blaIMP gene was most prevalent 70.03% (n=222) followed by blaNDM, 59.62% (n=189). Majority (87.69%, 278) were co-producers of classes D and B carbapenemases, blaOXA-23 with blaIMP and blaNDM being the commonest. Synergy with meropenem-sulbactam and meropenem-colistin was 47% and 57% respectively. Reduced synergy (p= <0.0001) was noted for those harbouring blaOXA-51+blaOXA-23with blaNDM gene alone or co-producers.

Conclusion: Presence of blaNDM gene was a significant cause of synergy loss in meropenem-sulbactam and meropenem-colistin. In blaNDM endemic regions, tigecycline, minocycline and polymyxins could be viable options against CRAB isolates with more than one carbapenemase encoding genes.

The rapid emergence and widespread dissemination of carbapenem resistance in Gram negative bacilli has posed real challenges in the management of infection caused by them. In this regard, the emergence of carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) has been very significant not only because of the carbapenem resistance acquired by these organisms but also due to the fact that acquisition of this resistance has made the otherwise ‘insignificant colonizers’, a potential pathogen. The impact has been so severe that both the World Health Organization (WHO) in its global priority pathogen list and India in its Indian Pathogen Priority List has labelled CRAB as ‘critical priority pathogen’ for further research (World Health Organization Press [WHO], 2017; WHO and DBT, Indian Priority Pathogen List [IPPL], 2021). According to Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) report 2019, 68-82% percentage of CRAB isolates have been reported from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, South Africa, Argentina, Brazil, Iran, Pakistan, and Italy (GLASS, 2019). Moreover, the data from Central Asian and Eastern European surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (CAESAR) 2019, showed 80%-91% of CRAB isolates in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus (CAESAR, 2019). Similarly, the China Antimicrobial Surveillance network (CHINET) 2017 reported 82% CRAB isolates (CHINET, 2017) (OneHealth Trust).

Carbapenem group of drugs are the last resort therapeutic option in many low resource settings especially, in developing regions. However, as has been the case in India or for that matter most of the developing countries, the broad-spectrum property of this important group of drugs has encouraged excessive inappropriate use in form of over-the-counter scale or those without valid prescriptions (Laxminarayan and Chaudhury, 2016). Among the different enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in CRAB like Ambler classes A/B/D, porin channels, and efflux pumps, Ambler class B metallo-beta lactamases (MBLs) like blaNDM-1, has been reported as most worrisome (López et al., 2019). In addition to this, in Indian scenario, CRAB is very different from other parts of the world. Not only the molecular determinants of carbapenem resistance varies, the combination of resistance genes and availability of alternative therapeutic options also pose huge challenge in deciding for their appropriate management (Bartal et al., 2022). Several studies, though limited by heterogeneity in methods and sample size, have reported synergistic effect of antibiotics combinations (Ayoub Moubareck and Hammoudi Halat, 2020; Mohd Sazlly Lim et al., 2021). Despite there is lack of epidemiological data and experimental studies on susceptibility to alternative options in Indian context which indirectly promotes empirical use of antibiotics and hence emergence of carbapenem resistant organisms.

We have previously identified and studied the endemicity of CRAB in the intensive care unit (ICU) of the present study center against a background of high empirical carbapenem use (Banerjee et al., 2018). We have also studied sustained outbreak of CRAB wherein, it was shown that intense carbapenem use within the ICU facilitated the persistence of the CRAB isolates in the hospital environment causing repeated outbreaks (Sharma et al., 2021a). We then studied colistin resistance in CRAB isolates wherein all the resistant isolates were reported in patients with prior carbapenem therapy (Sharma et al., 2021b). To meet the heavy empirical carbapenem use we also tried to restrict the empirical therapy by detecting biomass through a low-cost hand-held microscope (Foldscope) (Sharma et al., 2022). However, even though the challenge of CRAB infection was elucidated through this series of related studies, no consensus could be reached on the therapeutic options of these resistance strains. Realizing the scarcity of data in Indian context, the present study was conducted to determine the susceptibility profile of CRAB against available standard drugs and their combinations and to determine association of in-vitro drug synergy with the widely prevalent molecular determinants of carbapenem resistance. To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the data on drug synergy and epidemiology on the largest number of CRAB isolates.

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, and the associated 2000 bedded tertiary care hospital, Varanasi. The work was approved by Institute ethical committee (Dean/2017/EC/186) and prior to sample collection an informed consent was taken from each subject or their guardian.

Isolates of A. baumannii from different clinical specimens were included in the study. The isolates were collected from various samples from the patients admitted to different wards and ICUs of the hospital over a period of 15 months (January 2018-March 2019). The sample size was calculated by the formula ‘n=Z2pq/d2’ (n=minimum sample size, Z= standard score based on given confidence level, p=prevalence rate, q=1-p, d= standard error), considering the previous prevalence data of A. baumannii in the study center (Banerjee et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2022). More than required isolates were included to increase the power of study and to eliminate any bias. The detailed demographic data of the patients were also noted.

Only those isolates were considered which were collected from patients with clinical suspicion of infections like pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infection, sepsis, and urinary tract infection. Only the first isolate from the samples were included. A. baumannii isolated from mixed infections and those suggesting colonization were excluded.

All the isolates were phenotypically characterized by standard microbiological methods as culture on MacConkey agar and Leeds Acinetobacter agar base media (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt Ltd, India), Gram staining and biochemical reactions. The molecular identification as A. baumannii was done by multiplex PCR, targeting recA gene and species specific ITS-region gene (Fallon and Young, 1996; Chen et al., 2014).

Susceptibility towards gentamicin (10 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), cefepime (30 µg) ceftriaxone (30 µg), cotrimoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg), piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10 µg), ampicillin/sulbactam (10/10 µg), imipenem (10 µg), meropenem (10 µg) and amikacin (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd, India) was tested by Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method.

MIC for imipenem, meropenem, doripenem, ampicillin, sulbactam, tigecycline, colistin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals Pvt. Ltd, India), polymyxin B (Bharat serums & vaccines Ltd, India), amikacin (Aristo Pharmaceuticals Ltd. India) and minocycline (Gufic Biosciences Ltd, India) was performed by agar dilution or broth microbroth dilution methods as per recommendation by Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (CLSI, 2020). The bacterial inoculum was prepared by inoculating, 2-3 pure isolated colonies from overnight growth into Luria Bertani (LB) broth medium (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt Ltd, India) and incubated at 37°C with constant shaking at 180 rpm for 2 hours. The turbidity was adjusted according to 0.5 McFarland standards and 0.01 mL suspension was used as inoculum. The test was performed in cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton broth and agar medium (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt Ltd, India). The drug potency was calculated as described elsewhere and antibiotic stock solution was prepared by dissolving antibiotic powders into appropriate solvent (Biswas and Rather, 2019). Escherichia coli ATCC® 25922, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC® 27853 and Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC® 19606 were used as quality controls. The results were interpreted according to CLSI guidelines 2020 (CLSI, 2020). For tigecycline, isolates with ≥4 µg/ml MIC were considered as resistant isolates (Marchaim et al., 2014).

For each tested antibiotic the MIC50 and MIC90 value was calculated. The MIC50 is equivalent to median MIC value and calculated as n x 0.5 (n=no. of test isolates). The MIC90 is the 90th percentile of the MIC value and calculated as n x 0.9, if the resulting number wasn’t an integer, therefore the subsequent integer next to the respective value represented the MIC90 (Biswas and Rather, 2019).

CRAB was defined as, an isolate resistant to anyone carbapenem (imipenem or meropenem). Multi-drug resistant A. baumannii (MDRAb) and extensively-drug resistant A. baumannii (XDRAb) was defined as an isolate showing non-susceptibility to at least 1 agent in ≥3 antimicrobial categories and at least 1 agent in all but <2 or fewer antimicrobial categories, respectively including penicillins, ß-lactam combination agents, cephems, carbapenems, lipopeptides, aminoglycoside, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and folate pathway antagonists (Magiorakos et al., 2012). The result of disc diffusion method was used for the above classification except for lipopeptides and tetracyclines which were not tested by disc diffusion method.

The MAR index was determined by using the formula MAR = a/b, where ‘a’ is the number of antibiotics to which the test isolate showed resistance and ‘b’ is the total number of antibiotics to which the test isolate was exposed. Values >0.2 MAR index represents high risk source of contamination is where antibiotics are frequently used (Sandhu et al., 2016).

The phenotypically carbapenem resistant isolates as detected by their MICs were subjected to genotypic characterization of carbapenemases encoding genes. Four different multiplex PCR was performed for detection of class A (blaGES, blaIMI/NMC-A, blaSME, blaKPC), class B (blaIMP, blaVIM, blaNDM) and class D (blaOXA-51, blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-58) genes. Each single reaction mixture (25 µL) contained 2.5 µL Taq DNA buffer, 2 µL of dNTP, and 1 µL of each primer (10 picomole; Eurofins Scientific India Pvt. Ltd.), 0.3 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (Genei Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India). To maintain volume, 5 µL of template DNA (100 ng/mL) and nuclease free water was added. The reactions were run under the following conditions: For blaGES, blaIMI/NMC-A, blaSME, and blaKPC genes, initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, 25 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 60 sec, and final extension at 72°C for 7 min (Hong et al., 2012). For blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaNDM genes, initial denaturation at 94°C for 10 min, 36 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 52°C for 40 sec, 72°C for 50 sec, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min (Poirel et al., 2011). For blaOXA-51, and blaOXA-23 genes, initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 45 sec, 57°C for 45 sec, 72°C for 60 sec, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min (Turton et al., 2006). For blaOXA-58 gene, initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 25 sec, 52°C for 40 sec, 72°C for 50 sec, and final extension at 72°C for 6 min (Woodford et al., 2006). The primer pairs used in the study have been shown in Table 1.

For 100 selected CRAB isolates with different genetic profile, synergy testing was performed in 96-well microtiter plate by checkerboard MIC method. The selection of antibiotics for synergy testing was done after reviewing the antibiogram of the tertiary care center and literature on potentially potent antibiotic combinations for CRAB isolates (Laishram et al., 2017; Banerjee et al., 2018; Ayoub Moubareck and Hammoudi Halat, 2020). The synergy was investigated for combination of meropenem with sulbactam and meropenem with colistin. The concentration used for meropenem-sulbactam combination ranged from 2-256 µg/ml for meropenem and 2-128 µg/ml for sulbactam. For meropenem-colistin combination, the concentration for meropenem used was same as above and for colistin the concentration ranged from 0.5-2 µg/ml. Single agent MIC was also determined during the checkerboard assay. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) was calculated and interpreted as described earlier (Biswas and Rather, 2019).

The clonal relationship of 100 CRAB isolates included for combination testing was studied by repetitive extragenic palindromic polymerase chain reaction (Rep-PCR) as described earlier (Fitzpatrick et al., 2016). The primer pair Rep1and Rep2 was used for the amplification. The reaction was run under the following condition, initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 60 sec, 40°C for 60 sec, 65°C for 8 min, and final extension at 72°C for 16 min. Each single reaction mixture (25 µl) contained 2.5 µl Taq DNA buffer, 2 µl of dNTP, and 2µl of each primer (10 picomole; Eurofins Scientific, India), 0.3 µl of Taq DNA polymerase (Genei, Bangalore, India). To maintain volume, 5 µl of template DNA (100 ng/mL) and nuclease free water was added. The amplified PCR products were run on 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis (BioRad Laboratories India Pvt. Ltd, India). Further the isolates showing similar band pattern were considered as one Rep cluster while isolates with inconsistent bands were grouped into different Rep cluster based on the dendrogram.

Fisher’s exact test was employed with the help of MedCalc® statistical software version 19.6.3.0., to compare the synergistic effect of drug combination with the phenotypic resistance profile and molecular determinants of carbapenem resistance in the CRAB isolates respectively.

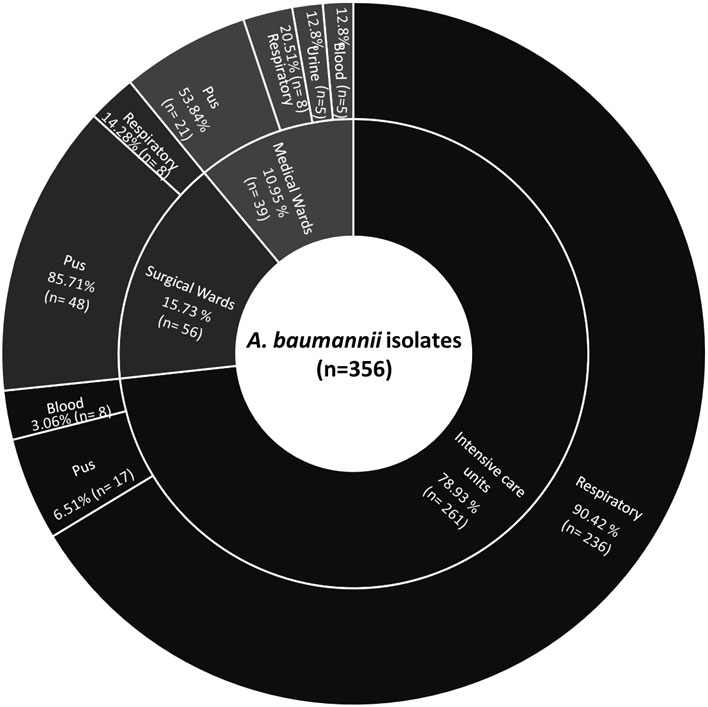

A total of 356 A. baumannii isolates confirmed by recA and ITS gene amplification were studied, among which majority were from the ICU 71.91% (n=256) followed by surgical wards 14.60% (n=52), and medical wards 13.48% (n=48). The most frequent site of infection was the lower respiratory tract. The demographic details of the patients showed, 71.1% (n=253) were males and 28.9% (n=103) were female with the mean age of 35.6 and 40.4 years respectively. The distribution of isolates among different clinical specimens and department has been shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Sunburst chart showing distribution of A. baumannii isolates among different departments and clinical specimen.

Among the 356 isolates, resistance was noted against gentamicin 93.25% (n=332), ciprofloxacin 96.06% (n=342), levofloxacin 92.13% (n=328), ceftazidime 94.66% (n=337), cefepime 96.34% (n=343), ceftriaxone 97.75% (n=348), cotrimoxazole 91.85% (n= 327), piperacillin/tazobactam 93.25% (n=332), ampicillin/sulbactam 76.93% (n=274), imipenem 92.41% (n=329), meropenem 87.35% (n=311) and amikacin 85.67% (n=305) by disc diffusion assay.

By MIC, highest resistance was seen against imipenem 89.04% (n=317) followed by amikacin 80.33% (n=286), meropenem 79.49% (n=283), doripenem 77.80% (n=277), ampicillin/sulbactam 71.62% (n=255), tigecycline 55.61% (n=198), minocycline 14.04% (n=50), polymyxin B 10.11% (n=36), and colistin 2.52% (n=9). The MIC results were considered for those drugs that were tested by both the methods, in case of discrepancy. The total number of isolates that were classified as CRAB were 317 (89.04%). Among 356 isolates, 81.46% (n=290) were reported as MDRAb, and 13.48% (n=48) as XDRAb. The exact MIC range, MIC50 and MIC90 values for each antimicrobial agent has been summarized in Table 2.

MAR index revealed 36 drug resistance patterns against 9 antimicrobial agents and >2 MAR index in 54.77% isolates (Supplementary Table 1). All of them were isolated from the ICU.

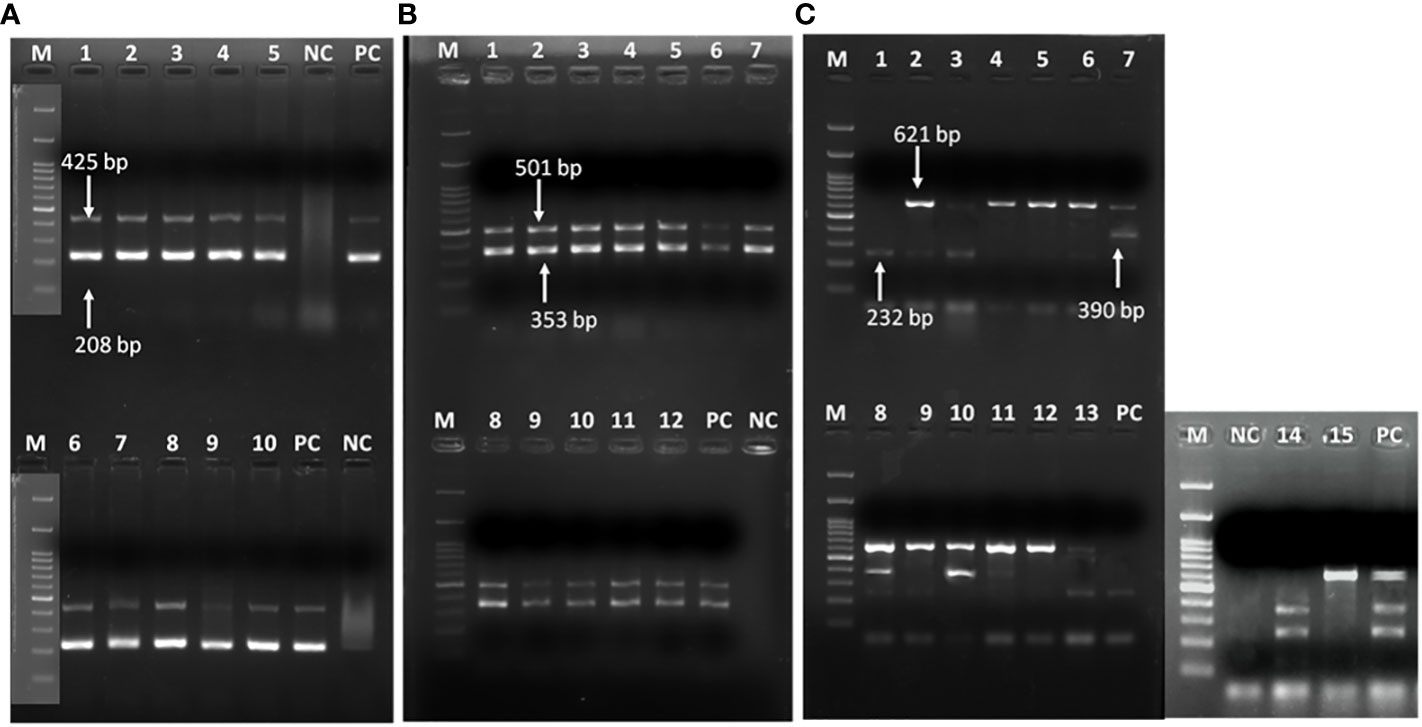

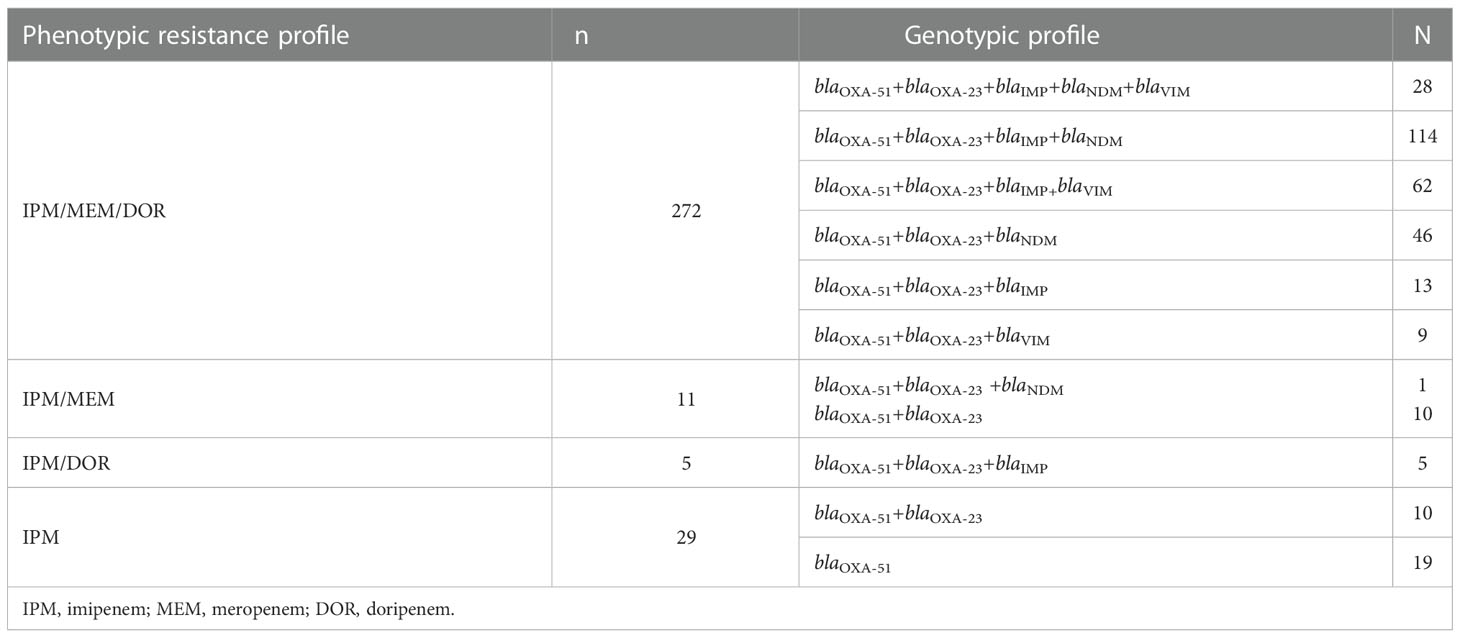

The genotypic characterization of 317 CRAB isolates showed that all were carrying blaOXA-51 gene (100%) and 94% (n=298) of the isolates were harbouring blaOXA-23 gene. Among class B carbapenemases, blaIMPgene was most prevalent 70.03% (n=222) in the CRAB isolates followed by blaNDM, 59.62% (n=189) and blaVIM, 31.23% (n=99) genes. Majority of isolates, 87.69% (n=278) were co-producers of class D and class B carbapenemases in multiple combinations (Figure 2). The most common combination was blaOXA-23 with blaIMP and blaNDM gene. None of the isolate was found positive for class A carbapenemases genes and blaOXA-58. The association between phenotypic carbapenem resistance profile and genotypic resistance profile of CRAB isolates has been shown in Table 3.

Figure 2 Representative gel image showing (A) recA and ITS genes in A baumannii; (B) blaOXA-51 and blaOXA-23 genes; (C) multiple class B carbapenemases. (A) Lane M: Marker 100 bp; Lane 1-5,6-10: recA (425bp) & ITS gene (208bp); NC: negative control PCR-grade water; PC: positive control A. baumannii ATCC 19606. (B) class D carbapenemase genes; Lane M: Marker 100 bp; Lane 1-12: blaOXA-51 (353 bp) & Lane 1-12: blaOXA-23 (501 bp); NC: negative control PCR-grade water; PC: previously confirmed & published isolate positive for blaOXA-51 & blaOXA-23 genes (C) class B carbapenamse genes; Lane M: Marker 100 bp; Lane 1-3,6,8, 13, 14: blaIMP (232 bp), Lane 7-8,10-11, 14: blaIMP (390 bp) & Lane 2-13, 15: blaNDM (621 bp); PC: previously confirmed & published isolate positive for blaIMP, blaVIM and blaNDM genes.

Table 3 The comparison of the phenotypic carbapenem resistance profile and genotypic resistance profile of CRAB isolates.

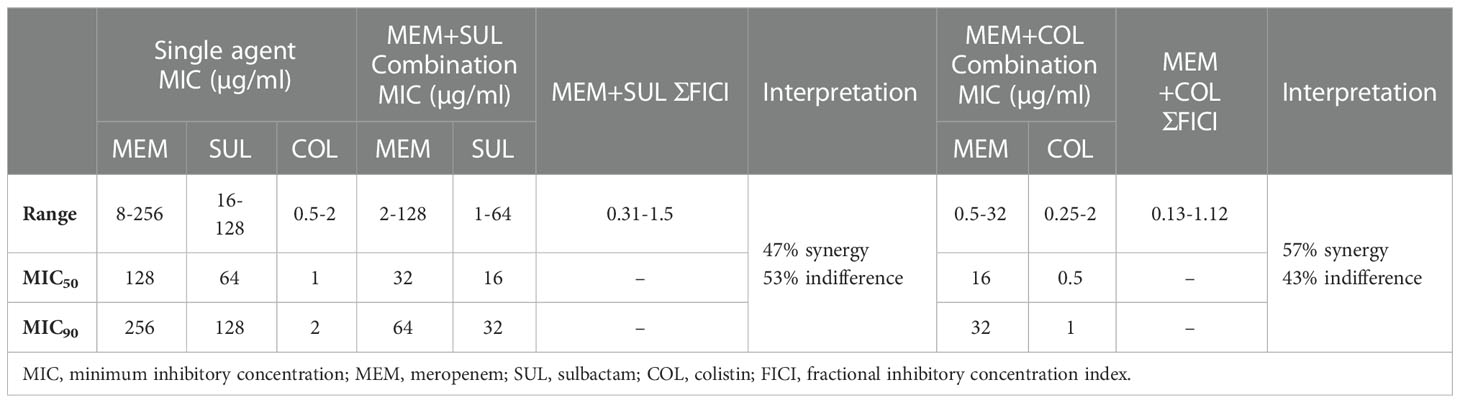

The reduction in MIC range, MIC50 and MIC90 was noted against the antibiotics in combination as compared to antibiotics as single agent (Table 4).The MIC50 and MIC90 of meropenem and sulbactam was reduced four-fold when tested in combination. The combination of meropenem-sulbactam was synergistic against 47% CRAB isolates and indifference against 53% CRAB isolates. When meropenem was combined with colistin, eight-fold and four-fold reduction in MIC50 and MIC90 of meropenem and colistin was noted respectively. The meropenem-colistin combination showed 57% synergy and 43% indifference against CRAB isolates. None of the combination showed antagonistic effect (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 4 Summarized results for drug combinations tested by checkerboard method against 100 CRAB isolates.

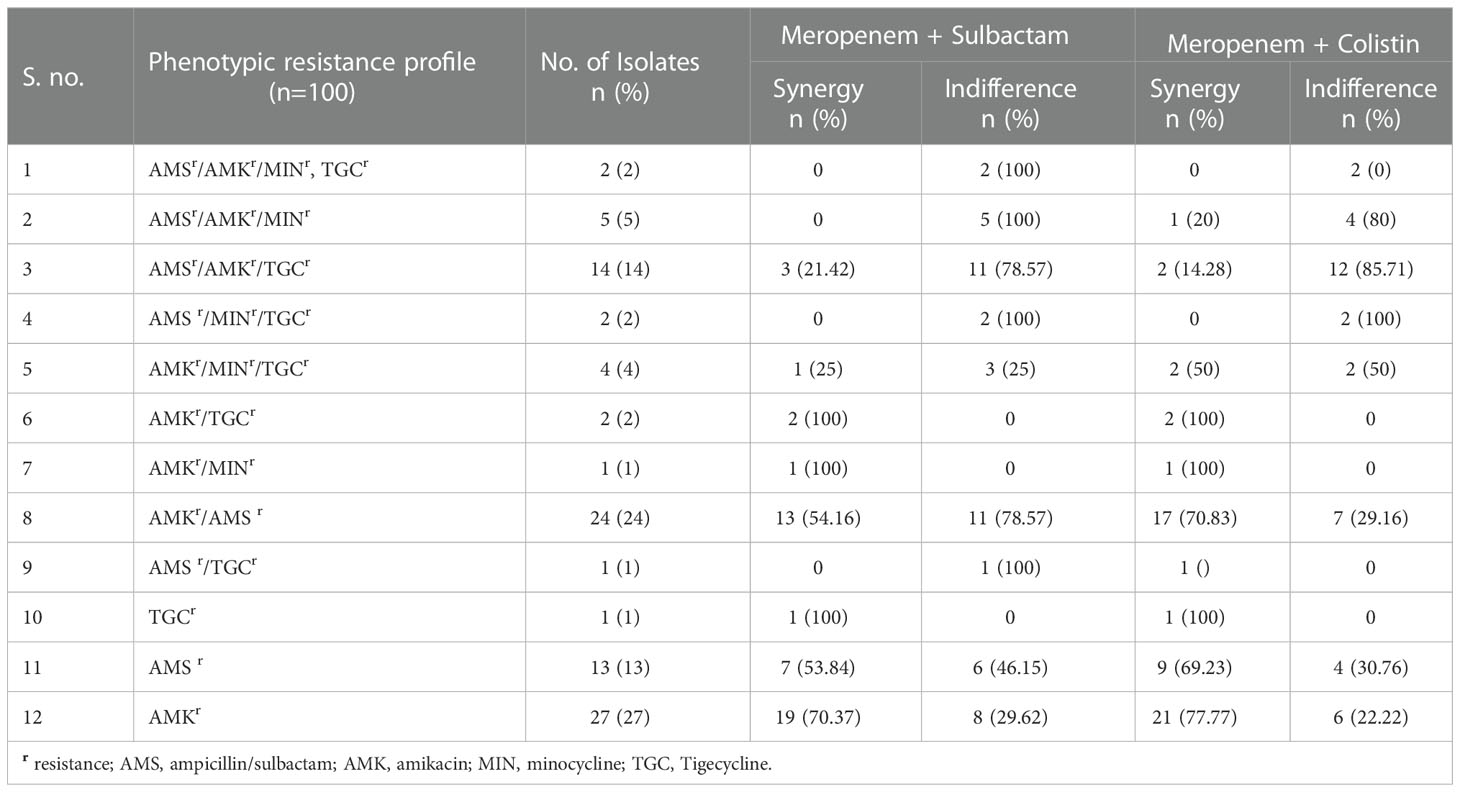

The synergistic effect of drug combinations was compared with the molecular mechanism of carbapenem resistance in CRAB isolates (Table 5). For both the combinations meropenem-sulbactam and meropenem-colistin 90-100% synergy was observed for isolates carrying blaOXA-51+blaOXA-23 and blaOXA-51+blaOXA-23with blaVIM or blaIMP genes. However, significantly lower synergy (p= <0.0001) was noted for the isolates harbouring blaOXA-51+blaOXA-23 with blaNDM gene alone or co-producing other metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs). When the association of synergism with various phenotypic resistance patterns to other drug classes were compared, no significant association was seen with any profile (Table 6).

Table 6 Comparison of drug synergy and phenotypic non-carbapenem resistance profile of 100 CRAB isolates.

Based on Rep-PCR, 18 different clusters consisting of 2 to 5 isolates with 100% similarity were detected in the 100 CRAB isolates. Besides, 57 singletons were detected with 50-90% similarity as shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

The study highlights the extent of antimicrobial resistance in A. baumannii, dissemination of carbapenem resistance determinants and more importantly the synergistic effect of drug combinations on molecular determinants of carbapenem resistance. The study is significant as it is the first extensive study on in-vitro susceptibility of alternative drugs and their combinations on a large number of CRAB isolates from this part of the globe. The most striking finding is the existence of multiple carbapenemase encoding genes in these isolates with presence of blaNDM significantly accounting for the loss of synergy in the combination therapies against these isolates.

Both, intrinsic and acquired class D carbapenemases like blaOXA-51 and blaOXA-23, are the most prevalent enzymes in CRAB worldwide. A recent study on population structure of CRAB circulating in the US hospital systems under the Study Network of Acinetobacter as a Carbapenem-Resistant Pathogen (SNAP) study has revealed the predominance of blaOXA-23 followed by other class D enzymes. In these isolates, MBLs were rare (Iovleva et al., 2022). The situation is in contrast in South and Southeast Asia where MBLs, with comparatively broader spectrum of activity, are quite prevalent (Hsu et al., 2017). This study showed that not only blaNDM, others like blaIMP, which was considered rare in CRAB almost 10 years back, has emerged rapidly (Viehman and Nguyen, 2014).

The endemic burden of CRAB has become a major cause of healthcare associated infections (HAIs) in large referral hospitals worldwide. In this study considerable resistance (70% - >90%) against cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, cotrimoxazoles, piperacillin/tazobactam, carbapenems, amikacin and ampicillin/sulbactam was revealed. Currently the therapeutic options for CRAB might be cefiderocol or colistin in combination with carbapenems or minocycline or tigecycline (Monnheimer et al., 2021). The study showed appreciable in-vitro activity of tigecycline (44.39%), minocycline (85.96%), polymyxin B (89.89%) and colistin (97.48%) against CRAB isolates, the use of which could be rationalized for the most effective management of these isolates. In this regard minocycline, as a non-polymyxin based therapeutic agent, has been promising for treatment of CRAB infections. Two large surveillance-based studies on minocycline activity have shown similarly high susceptibility towards A. baumannii isolates. However, both these studies were from developed nations where molecular epidemiology of the isolates were different from the present study (Lashinsky et al., 2017). Nevertheless, minocycline was effective in the CRAB isolates with multiple carbapenemase genes. A systematic review of effectiveness of minocycline treatment reported clinical and microbiological success rates of 72.6% and 60.2% respectively. Most of the infections treated were of pneumonia (Fragkou et al., 2019). Susceptibility against tigecycline, another non-polymyxin therapeutic agent, was also tested, as according to clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Disease Society of America and the American Thoracic Society (ATS-IDSA), the use of tigecycline for the treatment of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) in adult patients is recommended (Kalil et al., 2016). Clinical trials to measure the efficacy of tigecycline with comparators are scarce in literature, though one of the largest case series have shown the utility of early initiation of tigecycline in reducing severity of infections due to XDRAb (Lee et al., 2013). However, there has been concern regarding development of resistance with the use of tigecycline as monotherapy. The present study showed more than 50% resistance against tigecycline, though a similar study conducted in an adjacent country (Nepal) showed 100% susceptibility (Joshi et al., 2017). However, smaller sample size in the latter study could be the reason for the difference.

Comparable rates of polymyxin B and colistin resistance ranging from 0%-4% from a multicenter study in European countries has been reported (Wang et al., 2022). Besides, surveillance data from countries of US and Europe have also documented lower rate of polymyxins resistance even in XDR CRAB (Piperaki et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022). Similarly, in polymyxin based therapies, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated better clinical response as compared to non-polymyxin based therapies (61.7% vs. 39.3%). However, polymyxins being nephrotoxic, showed more adverse events (Lyu et al., 2020).

It should be emphasized that, besides activity, the most important consideration in the above-mentioned antibiotics is the cost. Most of these drugs (minocycline and polymyxins) are not affordable by the people of the developing countries. Access to antibiotics, availability or purchasing power of the population, burden of secondary infection, inadequate healthcare facilities often are the decisive factors for the choice of treatment of CRAB infections (Joshi et al., 2017).

The increasing carbapenem resistance has restricted the antibiotic armamentarium and so combination therapies are frequently being used to increase the antibiotic coverage against MDRAb and XDRAb. The most appropriate combinations suggested against MDRAb and XDRAb in a handful of reports till date is based on testing on a smaller number of isolates than the present study (Laishram et al., 2017). The combinations are of meropenem, imipenem, amikacin or cefepime with sulbactam as it has an intrinsic affinity for penicillin-binding proteins of A. baumannii. The other most suggested combination is colistin with carbapenem or colistin-tigecycline (Ayoub Moubareck and Hammoudi Halat, 2020). Based on the hospital setup in this study where meropenem is made available for the treatment free of cost as a part of government supply, synergistic effect for meropenem-sulbactam and meropenem-colistin combinations was studied. The latter showed 57% synergistic effect against the CRAB isolates. Additionally, the colistin combination therapy in comparison with colistin monotherapy has also been found beneficial for reduction in risk of nephrotoxicity (Ayoub Moubareck and Hammoudi Halat, 2020).

All the four Ambler classes have been described in A. baumannii and among them the OXA-type carbapenemases followed by MBLs have been reported as dominant mechanism of resistance around the South and Southeast Asian countries (Hsu et al., 2017). Presence of blaOXA-23 is one of the common causes of resistance conferring the high level of resistance. Usually, MBLs are less frequently detected in developed regions in contrast to the developing regions like India where multiple carabapenemase encoding genes are found in the CRAB isolates without any compensation in fitness (Sharma et al., 2021). Among the genes, blaOXA-23 is highly endemic and the most common carbapenemase encoding gene found in India followed by blaNDM (Vijayakumar et al., 2020). The blaOXA-51 gene is known to be a native chromosomal oxacillinase and was present in all the study isolates. The widespread burden of blaOXA-23 (94%) as seen this study indicates the probable relocation of the gene in chromosome or plasmid (Vijayakumar et al., 2022). The prevalence of blaIMP, gene has already been reported from this study center previously, though infrequent reports have been found from other countries (Alkasaby and Zaki El Sayed, 2017; Banerjee et al., 2018; Fallah et al., 2014). The blaNDM genes was also found in a high percentage (59.62%) of the isolates and are known to be widely disseminated around the globe (Fallah et al., 2014; Alkasaby and Zaki El Sayed, 2017; Vijayakumar et al., 2020). The isolates were found negative for class A beta-lactamases and blaOXA-58 gene, probably because they are the common mechanism of resistance in European or western countries (Vijayakumar et al., 2022). Additionally, it was interesting to note that the predominance of blaOXA-58 was replaced by blaOXA-23 since 2009 in the Mediterranean region, probably due to selective advantage of the latter with higher carbapenemase activity (Djahmi et al., 2014). A more recent study has reported isolates producing blaOXA-23 alone or coproducing blaOXA-23, andblaNDM mostly belonged to international clone (IC) IC1 and IC2 among which IC2 is highly transmissible (Vijayakumar et al., 2022).

The correlation of molecular mechanism of resistance with synergy rate is an important aspect which has been less studied. The study noted high rate of synergy against both meropenem-sulbactam and meropenem-colistin combinations when there is absence of blaNDM gene. The blaNDM gene is known to be most concerning gene among the MBLs because the expression of blaNDM genes not only helps in production of high-level beta-lactamases but also favours fitness cost for bacterial growth (López et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2021). While the blaNDM gene was first reported from India more than 10 years back, its widespread dissemination is a serious cause of concern (Kumarasamy et al., 2010). Based on this study it can be inferred that in blaNDM endemic regions such combinations might not be appropriate strategy for the management of the CRAB isolates.

The study was not without limitations. It was a single center study though a large number of CRAB isolates were included. In addition, the molecular epidemiology of the isolates was representative of the nation at large as per previous reports. Secondly, this was an in-vitro study without any data on the course of actual management of the infections with these isolates. Nevertheless, the study clearly reveals the burden of CRAB with more than one carbapenemase encoding genes, role of blaNDM in failure of combination therapy and possible therapeutic options against the resistant isolates.

The study revealed susceptibility of minocycline (85.96%), polymyxin B (89.89%) and colistin (97.48%) against the CRAB isolates with more than one carbapenemase encoding genes from India. Combinations of meropenem-sulbactam and meropenem-colistin showed 47% and 57% synergy respectively. However, presence of blaNDM gene in the CRAB isolates was a significant cause of loss of synergy. Therefore, the blaNDM endemic regions must review the treatment options against CRAB infections with alternatives like tigecycline, minocycline and polymyxins. Despite being limited to in-vitro data, the study involves one of the largest data on synergy testing against CRAB isolates harbouring multiple classes of carbapenemases and their alternative therapeutic options.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institute Ethical committee, Institute of Medical Sciences, BHU. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

SS performed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. TB conceptualized, designed the study and revised the manuscript. GY and AK supervised the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1068840/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Dendrogram by Rep-PCR of 100 CRAB isolates included in drug synergism testing.

Alkasaby, N. M., Zaki El Sayed, M. (2017). Molecular study of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates for metallo-β-lactamases and extended-spectrum-β-lactamases genes in intensive care unit, mansoura university hospital, Egypt. Int. J. Microbiol., 2017, 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2017/3925868

Ayoub Moubareck, C., Hammoudi Halat, D. (2020). Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii: a review of microbiological, virulence, and resistance traits in a threatening nosocomial pathogen. Antibiotics 9, 119 1–8. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9030119

Banerjee, T., Mishra, A., Das, A., Sharma, S., Barman, H., Yadav, G. (2018). High prevalence and endemicity of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter spp. in intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital, varanasi, India. J. Pathog. 2018, 1–8. doi: 10.1155/2018/9129083

Bartal, C., Rolston, K. V. I., Nesher, L. (2022). Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Colonization, infection and current treatment options. Infect. Dis. Ther. 11, 683–694. doi: 10.1007/s40121-022-00597-w

Biswas, I., Rather, P. N. Acinetobacter baumannii: Methods and Protocols. New York: Springer Humana New York, NY Publisher (2019). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9118-1

Chen, T. L., Lee, Y. T., Kuo, S. C., Yang, S. P., Fung, C. P., Lee, S. D. (2014). Rapid identification of Acinetobacter baumannii, Acinetobacter nosocomialis and Acinetobacter pittii with a multiplex PCR assay. J. Med. Microbiol. 63 (9), 1154–1159. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.071712-0

CLSI (2020). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 30th ed CLSI supplement M100 (Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute).

Djahmi, N., Dunyach-Remy, C., Pantel, A., Dekhil, M., Sotto, A., Lavigne, J. P. (20142014). Epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii in Mediterranean countries. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014, 305784. doi: 10.1155/2014/305784

Fallah, F., Noori, M., Hashemi, A., Goudarzi, H., Karimi, A., Erfanimanesh, S., et al. (2014). Prevalence of blaNDM, blaPER, blaVEB, blaIMP, and blaVIM genes among Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from two hospitals of Tehran, Iran. Scientifica 2014, 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2014/245162

Fallon, R. J., Young, H. (1996). “Neisseria, moraxella, acinetobacter,” in Mackie & McCartney practical medical microbiology, 14th edition. Eds. Collee, J. G., Fraser, A. G., Marmion, B. P., Simmons, A. (London, UK: Churchill Livingstone), 283–361.

Fitzpatrick, M. A., Ozer, E. A., Hauser, A. R. (2016). Utility of whole-genome sequencing in characterizing Acinetobacter epidemiology and analyzing hospital outbreaks. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 593–612. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01818-15

Fragkou, P. C., Poulakou, G., Blizou, A., Blizou, M., Rapti, V., Karageorgopoulos, D. E., et al. (2019). The role of minocycline in the treatment of nosocomial infections caused by multidrug, extensively drug and pandrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a systematic review of clinical evidence. Microorganisms 7, 159. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7060159

WHO Country Office for India, Department of Biotechnology Government of India. Indian Priority pathogen list: to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics in India. (World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland) (2021), 1–22. Available at: https://dbtindia.gov.in/sites/default/files/IPPL_final.pdf.

Hong, S. S., Kim, K., Huh, J. Y., Jung, B., Kang, M. S., Hong, S. G. (2012). Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding class a carbapenemases. Ann. Lab. Med. 32, 359–361. doi: 10.3343/alm.2012.32.5.359

Hsu, L. Y., Apisarnthanarak, A., Khan, E., Suwantarat, N., Ghafur, A., Tambyah, P. A. (2017). Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Enterobacteriaceae in south and southeast Asia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 30, 1–22. doi: 10.1128/CMR.masthead.30-1

Iovleva, A., Mustapha, M. M., Griffith, M. P., Komarow, L., Luterbach, C., Evans, D. R., et al. (2022). Carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii in US hospitals: diversification of circulating lineages and antimicrobial resistance. mBio 13, e0275921. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02759-21

Joshi, P. R., Acharya, M., Kakshapati, T., Leungtongkam, U., Thummeepak, R., Sitthisak, S. (2017). Co-Existence of blaOXA-23 and blaNDM-1 genes of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from Nepal: antimicrobial resistance and clinical significance. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 6, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0180-5

Kalil, A. C., Metersky, M. L., Klompas, M., Muscedere, J., Sweeney, D. A., Palmer, L. B. (2016). Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of America and the American thoracic society. Clin. Infect. Dis. 63, e61–111. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw353

Kumarasamy, K. K., Toleman, M. A., Walsh, T. R., Bagaria, J., Butt, F., Balakrishnan, R. (2010). Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10, 597–602. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70143-2

Laishram, S., Pragasam, A. K., Bakthavatchalam, Y. D., Veeraraghavan, B. (2017). An update on technical, interpretative and clinical relevance of antimicrobial synergy testing methodologies. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 35, 445–468. doi: 10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_17_189

Lashinsky, J. N., Henig, O., Pogue, J. M., Kaye, K. S. (2017). Minocycline for the treatment of multidrug and extensively drug-resistant A. baumannii: a review. Infect. Dis. Ther. 6, 199–211. doi: 10.1007/s40121-017-0153-2

Laxminarayan, R., Chaudhury, R. R. (2016). Antibiotic resistance in India: drivers and opportunities for action. PloS Med. 13, e1001974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001974

Lee, Y. T., Tsao, S. M., Hsueh, P. R. (2013). Clinical outcomes of tigecycline alone or in combination with other antimicrobial agents for the treatment of patients with healthcare-associated multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32, 1211–1220. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1870-4

López, C., Ayala, J. A., Bonomo, R. A., González, L. J., Vila, A. J. (2019). Protein determinants of dissemination and host specificity of metallo-β-lactamases. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11615-w

Lyu, C., Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Wu, J., Zhang, J. (2020). Clinical efficacy and safety of polymyxins based versus non-polymyxins based therapies in the infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 296. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05026-2

Magiorakos, A. P., Srinivasan, A., Carey, R. B., Carmeli, Y., Falagas, M. E., Giske, C. G., et al. (2012). Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x

Marchaim, D., Pogue, J. M., Tzuman, O., Hayakawa, K., Lephart, P. R., Salimnia, H., et al. (2014). Major variation in MICs of tigecycline in gram-negative bacilli as a function of testing method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 1617–1621. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00001-14

Mohd Sazlly Lim, S., Heffernan, A. J., Zowawi, H. M., Roberts, J. A., Sime, F. B. (2021). Semi-mechanistic PK/PD modelling of meropenem and sulbactam combination against carbapenem-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 40, 1943–1952. doi: 10.1007/s10096-021-04252-z

Monnheimer, M., Cooper, P., Amegbletor, H. K., Pellio, T., Groß, U., Pfeifer, Y., et al. (2021). High prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in wound infections, Ghana 2017/2018. Microorganisms 9, 537. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9030537

One Health Trust (2022) Resistance map: Antibiotic resistance. Available at: https://resistancemap.onehealthtrust.org/AntibioticResistance.php/CountryPageSub.php (Accessed November 28, 2022).

Piperaki, E. T., Tzouvelekis, L. S., Miriagou, V., Daikos, G. L. (2019). Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: in pursuit of an effective treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 25, 951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.014

Poirel, L., Walsh, T. R., Cuvillier, V., Nordmann, P. (2011). Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 70, 119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002

Sandhu, R., Dahiya, S., Sayal, P. (2016). Evaluation of multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index and doxycycline susceptibility of Acinetobacter species among inpatients. Indian J. Microbiol. Res. 3 (3), 299. doi: 10.5958/2394-5478.2016.00064.9

Sharma, S., Banerjee, T., Yadav, G., Chaurasia, R. C. (2022). Role of early foldscopy (microscopy) of endotracheal tube aspirates in deciding restricted empirical therapy in ventilated patients. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 40, 96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmmb.2021.08.004

Sharma, S., Banerjee, T., Yadav, G., Palandurkar, K. (2021b). Mutations at novel sites in pmrA/B and lpxA/D genes and absence of reduced fitness in colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from a tertiary care hospital, India. Microb. Drug Resist. 27, 628–636. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2020.0023

Sharma, S., Das, A., Banerjee, T., Barman, H., Yadav, G., Kumar, A. (2021a). Adaptations of carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) in the hospital environment causing sustained outbreak. J. Med. Microbiol. 70, 1–8. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001345

Turton, J. F., Woodford, N., Glover, J., Yarde, S., Kaufmann, M. E., Pitt, T. L. (2006). Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii by detection of the blaOXA-51-like carbapenemase gene intrinsic to this species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 2974–2976. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01021-06

Viehman, J. A., Nguyen, M. H. (2014). Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Drugs 74, 1315–1333. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0267-8

Vijayakumar, S., Jacob, J. J., Vasudevan, K., Mathur, P., Ray, P., Neeravi, A., et al. (2022). Genomic characterization of mobile genetic elements associated with carbapenem resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii from India. Front. Microbiol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.869653

Vijayakumar, S., Wattal, C., Oberoi, J. K., Bhattacharya, S., Vasudevan, K., Anandan, S., et al. (2020). Insights into the complete genomes of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii harbouring blaOXA-23, blaOXA-420 and blaNDM-1 genes using a hybrid-assembly approach. Access Microbiol. 2, 1–7. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000140

Wang, Y., Luo, Q., Xiao, T., Zhu, Y., Xiao, Y. (2022). Impact of polymyxin resistance on virulence and fitness among clinically important gram-negative bacteria. Engineering 13, 178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2020.11.005

Woodford, N., Ellington, M. J., Coelho, J. M., Turton, J. F., Ward, M. E., Brown, S., et al. (2006). Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 27, 351–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.004

World Health Organization Press (2017) Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed.

Keywords: blaNDM, minocycline, meropenem, synergy, endemic

Citation: Sharma S, Banerjee T, Yadav G and Kumar A (2023) Susceptibility profile of blaOXA-23 and metallo-β-lactamases co-harbouring isolates of carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) against standard drugs and combinations. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12:1068840. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1068840

Received: 13 October 2022; Accepted: 20 December 2022;

Published: 06 January 2023.

Edited by:

Luis Esau Lopez Jacome, Instituto Nacional de Rehabilitación, MexicoReviewed by:

Luis Fernando Espinosa-Camacho, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, MexicoCopyright © 2023 Sharma, Banerjee, Yadav and Kumar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tuhina Banerjee, ZHJ0dWhpbmFAeWFob28uY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.