- Center for Translational Immunology, Institute for Biomedical Sciences, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, United States

Transition metals are essential for metalloprotein function among all domains of life. Humans utilize nutritional immunity to limit bacterial infections, employing metalloproteins such as hemoglobin, transferrin, and lactoferrin across a variety of physiological niches to sequester iron from invading bacteria. Consequently, some bacteria have evolved mechanisms to pirate the sequestered metals and thrive in these metal-restricted environments. Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the causative agent of the sexually transmitted infection gonorrhea, causes devastating disease worldwide and is an example of a bacterium capable of circumventing human nutritional immunity. Via production of specific outer-membrane metallotransporters, N. gonorrhoeae is capable of extracting iron directly from human innate immunity metalloproteins. This review focuses on the function and expression of each metalloprotein at gonococcal infection sites, as well as what is known about how the gonococcus accesses bound iron.

Introduction

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Ngo) is an obligate human pathogen responsible for the sexually-transmitted disease, gonorrhea (Unemo et al., 2019). Gonococcal infections are on the rise; in 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates an approximate 82.4 million people were newly infected with Ngo and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 677,769 new cases in the United States (WHO, 2021; CDC, 2021). As antibiotic resistance increases, Ngo is a high priority for many agencies to monitor as an urgent threat pathogen (Ohnishi et al., 2011; WHO, 2021; Fifer et al., 2021). In December 2020 the CDC modified the recommended treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infection, from dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin, to a higher dose of monotherapy ceftriaxone (Sancta St. Cyr et al., 2020). Prior infection does not provide protective immunity against reinfection and currently there is no effective vaccine, so at-risk individuals are often reinfected (Schmidt et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2011).

Ngo colonizes mucosal sites including the genital tract, rectum, conjunctiva, or oropharynx; genital infections often begin as urethritis in men and cervicitis in women (Schmidt et al., 2001; Walker and Sweet, 2011; Unemo et al., 2019). An estimated 80% of cases in women are asymptomatic, thus delaying treatment. Belated treatment may allow the infection to ascend the reproductive tract causing severe secondary sequalae in men and women (Portnoy et al., 1974; Walker and Sweet, 2011). Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) occurs when Ngo invades the bloodstream, sometimes due to delayed treatment; DGIs historically occur in less than 3% of cases, are more common in individuals less than 40, and occur more frequently in women than men (Rice, 2005; Walker and Sweet, 2011; Unemo et al., 2019; Li and Hatcher, 2020; Springer and Salen, 2020). In recent years, the numbers of DGI infections, particularly in men, have increased with no known link among cases (Belkacem et al., 2013).

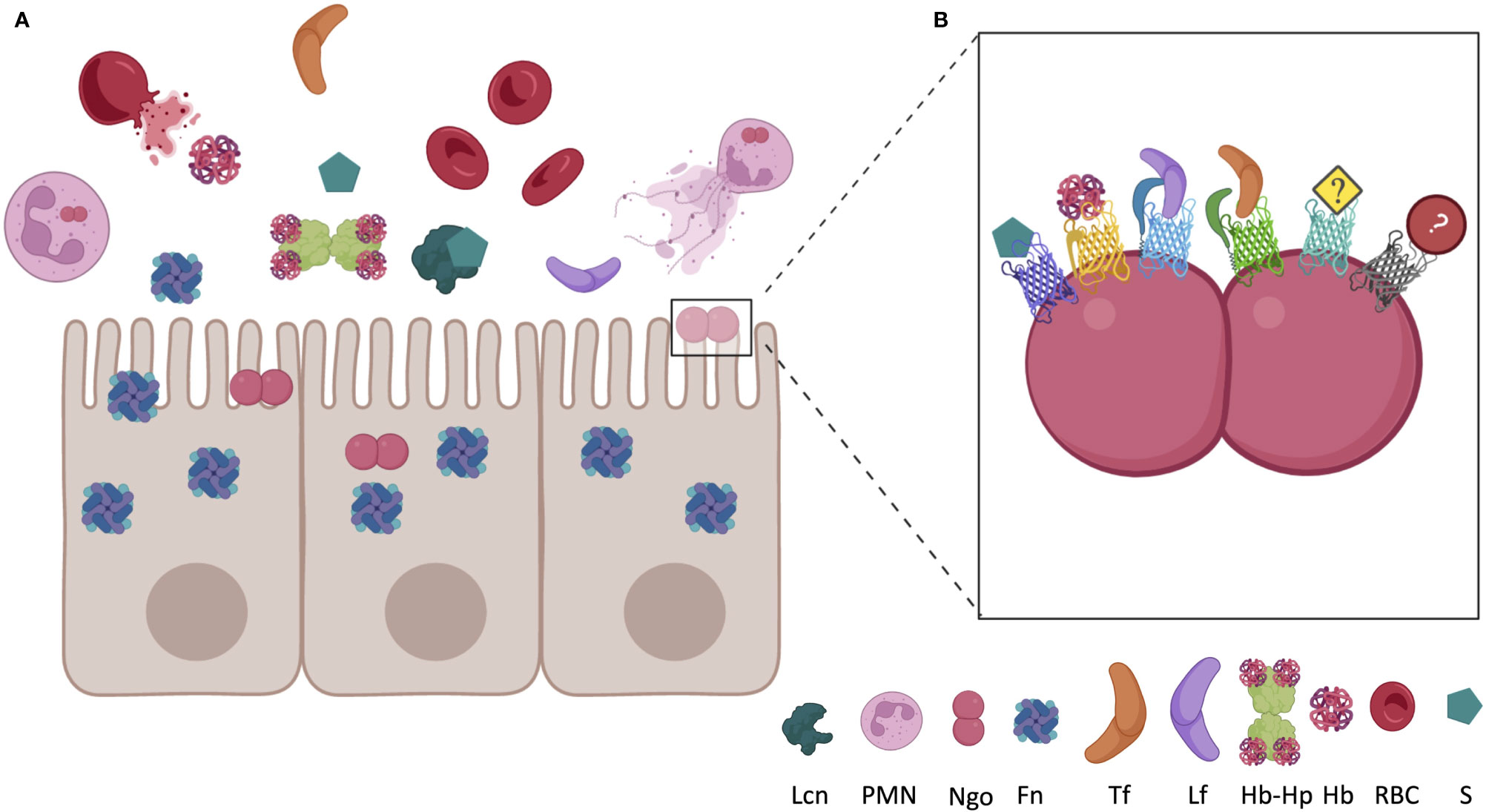

Pathogens require metals for metabolism; therefore, there is a constant tug-of-war between host sequestration and pathogen acquisition for essential metals. Nutritional immunity is a host defense against infection where metalloproteins sequester essential nutrients away from pathogens (Figure 1A) (Hood and Skaar, 2012). Upon infection by Ngo, PMNs (Polymorphonuclear monocytes) are recruited to the site of infection, often forming NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps), whereby the bacteria are exposed to the intracellular contents of the neutrophil, including several metal sequestration proteins [reviewed in (Criss and Seifert, 2012)]. Some Gram-negative pathogens have evolved ways to acquire iron directly from host metalloproteins, including transferrin (Tf), lactoferrin (Lf), and hemoglobin (Hb), using dedicated outer-membrane transporters [for a recent review see (Yadav et al., 2019)].

Figure 1 Localization of host nutritional immunity proteins near epithelial cell surface during inflammation and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Ngo) infection. (A) In a healthy environment, iron is almost entirely bound to intracellular ferritin (Fn), erythrocyte bound haptoglobin, or sequestered in circulating transferrin (Tf). Under inflammatory conditions, Fn may be released from epithelial cells and hemoglobin (Hb) may be released from red blood cells (RBC). Haptoglobin (Hp) almost immediately binds to the newly circulating Hb, forming the Hb-Hp complex. Infection by Ngo recruits PMNs, which can expel their cellular contents in an innate immune response, which includes lactoferrin (Lf). Coinfection with other bacteria, or presence of commensals, may lead to circulation of siderophores (S). Siderophores produced by bacteria, or the mammalian siderophore 2,5-DHBA, may also be present at the site of infection bound to circulating lipocalin (Lcn). (B) Ngo has evolved mechanisms to cope with the nutritional immunity evoked by the host. TonB-dependent proteins bind many of the host Fe-chelating proteins, permitting Ngo to grow in these metal-restricted environments. FetA binds to S, HpuAB bind to Hb or Hb-Hp, TbpA binds to Tf, LbpA binds to Lf, and TdfF and TdfG are both iron regulated, but the host ligand has yet to be identified. Utilization of iron from ferritin and lipocalin should be investigated due to the close proximity to Ngo during infection. Figure not to scale and generated with BioRender.com.

Access to, and availability of, metals in biological niches dictates the success and extent of infection by a pathogen. This review focuses on the roles of metalloproteins in regulating iron homeostasis in key gonococcal infection sites and how the gonococcus obtains the required iron for successful infection.

Iron requirements and sequestration proteins in the human host

Iron is the most abundant metal in humans and is essential for metabolism in most aerobic organisms (Brock, 1999; Pantopoulos et al., 2012; Nairz et al., 2014; Golonka et al., 2019). During metabolism, iron acts as a cofactor in iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster proteins and heme-containing proteins, aiding in heme synthesis, oxygen transport, and DNA synthesis (Pantopoulos et al., 2012; Ganz and Nemeth, 2015). Iron is also important for proliferation of immune cells including T-lymphocytes and neutrophils (Brock, 1999; Weiss, 1999). Iron levels are stringently regulated in humans; iron overload is cytotoxic due to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress (Brock, 1999; Golonka et al., 2019). Hemochromatosis, or iron overload, can be caused by inherited genetic mutations, blood transfusions, or excessive dietary intake of iron, and may lead to increased susceptibility to infections and accelerated death (Khan et al., 2007; McDowell et al., 2022).

To prevent the toxic effects of free iron, over 99.9% of excess mammalian iron is sequestered intracellularly, either via ferritin or heme, and extracellular iron is bound to metalloproteins including Hb, Lf, and Tf (Pantopoulos et al., 2012; Andreini et al., 2018). Approximately 2% of the human genome encodes iron-containing proteins, of which, more than half of the proteins have a catalytic function (Andreini et al., 2018). Upon inflammation or infection by a pathogen, the liver secretes a peptide hormone, hepcidin, which modifies an iron exporter ferroportin, thereby trapping iron intracellularly (Nemeth et al., 2004b). By solubilizing iron, making iron bioavailable, chelating iron, and protecting the host from ROS, Fe-containing metalloproteins play essential roles in humans.

Hb, found within erythrocytes, is the most abundant protein in blood; Hb sequesters heme, which is a heterocyclic porphyrin ring that binds centrally-coordinated ferrous iron (Fe2+) (Baldwin, 1975). Hb is a globular protein consisting of α- and β-globulin chains, and inside erythrocytes, Hb stores approximately 75% of all the iron in the body and the remaining 25% is stored by ferritin in liver, spleen, and bone marrow (Brock, 1999; Delaby et al., 2005; Ganz and Nemeth, 2015). Hemoproteins, including hemopexin, Hb, and Hb complexed with haptoglobin (Hp), each bind heme strongly at one or two of the free iron-coordination sites located perpendicularly to the porphyrin ring (Hare, 2017). Erythrocytes spontaneously lyse, releasing up to 3 µM free Hb in healthy patients (Na et al., 2005). In serum, tetrameric Hb dissociates into dimers, which are rapidly sequestered by Hp, and the Hb-Hp complex is recycled by macrophages (Kristiansen et al., 2001). Hb may release heme spontaneously, particularly after oxidation to ferric Hb, or because of bacterial proteases (Na et al., 2005; Kassa et al., 2016; Hare, 2017).

Tf and Lf are glycoproteins of similar structure and function, sharing 60% sequence identity (Baker et al., 2002). Tf and Lf both contain a C-lobe and an N-lobe, with one Fe3+ ion bound to coordinating residues on each lobe (Aisen et al., 1978; Baker et al., 2002). Both Tf and Lf bind iron with nM affinity, and, notably, Lf maintains high affinity iron binding at low pH, down to pH 3.0, whereas Tf releases bound iron below pH 6.5 (Aisen et al., 1978; Baker and Baker, 2004).

Tf, at 80 kDa, is synthesized by hepatocytes and secreted into the serum where it solubilizes ferric iron, sequesters iron to prevent toxicity, and delivers iron into cells (Andrews and Ganz, 2019). Tf is naturally found at approximately 30% iron-saturation in serum (Ganz and Nemeth, 2015; Andrews and Ganz, 2019). While inflammation increases hepcidin concentrations, serum Tf concentrations decrease due to the decreased iron in circulation, causing a syndrome called anemia of infection (Ganz and Nemeth, 2009).

Lf, at 82 kDa is synthesized by neutrophils and exocrine glands and is primarily located in human milk and mucosal secretions (Masson and Heremans, 1968; Cohen et al., 1987; Kruzel et al., 2000; Rageh et al., 2016). Lf is antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory (Broekhuyse, 1974; Flanagan and Willcox, 2009; Okubo et al., 2016; Lepanto et al., 2019). Lf has been implicated as a regulator of inflammation (Baker and Baker, 2004; Alexander et al., 2012; Valenti et al., 2018). Lf is secreted by cervical and epithelial cells and found in secondary granules of human neutrophils (Lewis-Jones et al., 1985; Nuijens et al., 1992; Alexander et al., 2012; Valenti et al., 2018). Lf levels change in mucosal secretions at different stages of the menstrual cycle; Lf levels are lowest in the days before menstruation and highest proceeding menstruation when the cervix is more open, to prevent pathogenesis (Cohen et al., 1987). The fluctuation of Lf levels is likely hormone driven, as women taking oral contraceptives do not demonstrate an increase in Lf levels during menses, which could lead to higher infection rates (Cohen et al., 1987).

Humans produce siderocalins of the lipocalin family that chelate siderophores (Correnti and Strong, 2012; Sia et al., 2013; Page, 2019). Most Gram-negative bacteria produce siderophores, which scavenge environmental iron (Guerinot, 1994; Rohde and Dyer, 2003; Wandersman and Delepelaire, 2004; Miethke and Marahiel, 2007). Siderophores have such a high affinity and specificity for iron that they can pirate iron directly from Tf, Lf, but not heme (Raymond et al., 2003). By sequestering the bacterially produced siderophores, siderocalins can inhibit bacterial growth.

Lipocalin 2 (Lcn2) was first discovered as a neutrophil granule component and tightly binds bacterial catecholate ferric siderophores, including enterobactin; however, Lcn2 can also sequester some carboxylates (Kjeldsen et al., 2000; Goetz et al., 2002; Chakraborty et al., 2012). Mammalian catechols, often secreted in the urine, and the mammalian siderophore 2, 5-DHBA also bind to Lcn2; mammalian catechols may be derived from foods and 2,5-DHBA is produced from a gene with a bacterial homolog for the production of enterobactin (Bao et al., 2010; Devireddy et al., 2010). Lcn2 is produced by neutrophils, macrophages, hepatocytes, epithelial cells and adipocytes; therefore, it is present at mucosal sites at the initial stages of gonococcal infection and colonization (Kjeldsen et al., 2000; Chakraborty et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2017).

Acquisition of iron by Neisseria

TonB-dependent transporters (TDTs) are important for iron acquisition by Ngo and Neisseria meningitidis. TDTs are produced by most Neisseria strains and are highly conserved, suggesting TDTs play a significant survival role (Cornelissen et al., 1997a; Cornelissen et al., 2000; Cornelissen, 2008; Cornelissen and Hollander, 2011; Yadav et al., 2019). In Gram-negative bacteria, TDTs pirate iron, zinc, and other metals directly from host metalloproteins (Schryvers and Stojiljkovic, 1999; Cornelissen, 2018; Maurakis et al., 2019; Kammerman et al., 2020). TDTs are beta-barrels embedded in the outer membrane of the bacterium (Noinaj et al., 2013; Noinaj and Buchanan, 2014; Noinaj and Buchanan, 2018). With the help of TonB, TDTs extract metals, including iron and zinc, from host metalloproteins (Noinaj et al., 2012b; Cash et al., 2015; Maurakis et al., 2019; Kammerman et al., 2020).

The mechanism of metal import through TDTs is still being characterized. However, studies on TbpA suggest that a helical structure in the extracellular loops of the TDT may physically force the metal out upon binding of the ligand (Cash et al., 2015; Duran and Özbil, 2021). The extracted metal is immediately exposed to the plug domain of the TDT located in the pore of the beta-barrel, which may have a higher affinity for the metal than the ligand; thus, the metal ion relocates to the plug domain (Noto and Cornelissen, 2008). TonB is hypothesized to move the plug domain out of the barrel towards the periplasm, the metal ion is then exposed to a periplasmic binding protein that will ferry it to an ABC transporter, upon which the metal is imported into the cytoplasm, where it can then be used for essential metabolic processes, including replication within humans (Cornelissen et al., 1997b; Noinaj et al., 2010; Noinaj et al., 2012a; Noinaj et al., 2012b; Noinaj and Buchanan, 2014; Cash et al., 2015; Noinaj et al., 2017).

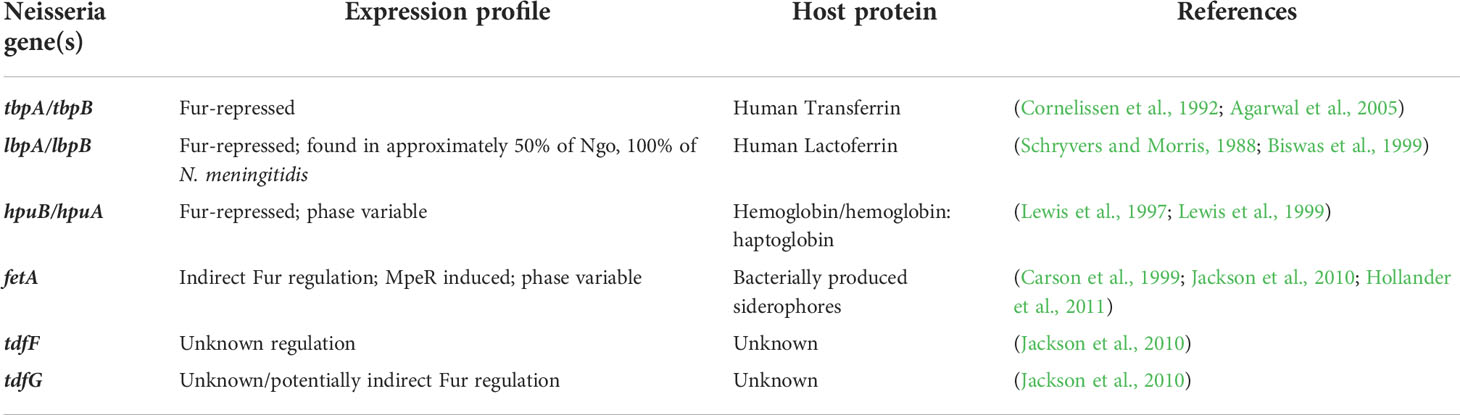

Several TDTs have been identified for their role in iron acquisition (Table 1; Figure 1B). Transferrin binding protein A (TbpA) is repressed by the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) under iron replete conditions (Agarwal et al., 2005). TbpA binds to hTf with an affinity of ~10 nM and is required for iron utilization from hTf (Cornelissen et al., 1992; Cornelissen and Sparling, 1996; Gray-Owen and Schryvers, 1996; Renauld-Mongénie et al., 2004; Noto and Cornelissen, 2008). Utilizing the human male model of gonococcal infection, a TbpAB knockout mutant was unable to establish an infection, suggesting essentiality of the system (Cornelissen et al., 1998). TbpA is a highly conserved 100 kDa, 22-stranded β-barrel outer-membrane receptor and TbpB is a more variable 85 kDa lipoprotein, which facilitates TbpA binding to iron loaded host Tf (Cornelissen and Sparling, 1996; Noinaj and Buchanan, 2014; Cash et al., 2015; Noinaj et al., 2017; Yadav et al., 2019). In Ngo, or N. meningitidis strains containing the type 2 variants of tbpB, TbpB is not essential for iron acquisition from Tf, but instead increases the rate iron uptake from hTf (Anderson et al., 1994; Renauld-Mongénie et al., 2004). N. meningitidis strains containing type 1 variants of tbpB, however, do require both proteins to bind hTf (Irwin et al., 1993). TbpA binds iron-saturated Tf or apo-Tf at similar rates (Tsai et al., 1988; Blanton et al., 1990; Anderson et al., 1994; Retzer et al., 1998).

Table 1 Neisseria express TonB-dependent transporters in response to iron limitation, which allow for the utilization of host nutritional immunity proteins as metal sources.

Lactoferrin-binding protein A (LbpA) binds to and extracts iron from human Lf (Schryvers and Morris, 1988; Pettersson et al., 1994; Biswas and Sparling, 1995; Anderson et al., 2003). LbpA is present in approximately 50% of gonococcal strains and all meningococcal strains and is Fur-repressed in high-iron environments and subjected to phase variation (Mickelsen and Sparling, 1981; Biswas and Sparling, 1995; Biswas et al., 1999; Anderson et al., 2003). Among the Ngo LbpA producers, only 30% express the lipoprotein LbpB, suggesting that LbpB is not required for Lf utilization (Bonnah and Schryvers, 1998; Biswas et al., 1999; Anderson et al., 2003; Cornelissen and Hollander, 2011). Similar to TbpB, LbpB binds primarily to holo-Lf (Yadav et al., 2021). While the presence of LbpAB increases competitive fitness over strains expressing the Tbp system alone, LbpAB is not essential for infection (Anderson et al., 2003).

Both TDTs TbpA and LbpA are capable of binding to, and extracting iron from, their human ligand in the absence of their respective lipoprotein partner; however, the TDT HpuB requires the lipoprotein HpuA to utilize the iron or heme from Hb and Hb-Hp complexes (Lewis et al., 1997; Lewis et al., 1998; Lewis et al., 1999; Rohde et al., 2002; Rohde and Dyer, 2004). HpuB (85 kDa) is the outer-membrane receptor (Postle, 1993; Klebba et al., 1993) and HpuA (35 kDa) is the lipoprotein partner (Lewis et al., 1997; Lewis et al., 1999; Rohde et al., 2002; Anzaldi and Skaar, 2010). In N. meningitidis, HpuAB binds to Hb, Hb-Hp, and apo-haptoglobin (Lewis et al., 1999). hpuAB undergoes phase variation due to slipped-strand mispairing, resulting in a frameshifted non-functional protein (Lewis et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1998; Lewis et al., 1999). Further, hpuAB is Fur repressed under iron replete conditions. (Lewis et al., 1997). Gonococcal isolates collected from women in the first two weeks of their menstrual cycle are more likely to express HpuAB, suggesting that when Hb and Hp are abundant, Ngo producing HpuAB is under selective pressure to be expressed (Chen et al., 1998; Anderson et al., 2001).

Ngo is unable to synthesize siderophores; however, the gonococcus can use siderophores produced by other bacteria, including salmochelin, enterobactin, and dihydroxybenzoylserine acid through the TDT FetA (West and Sparling, 1987; Carson et al., 1999; Strange et al., 2011). FetA is an 80 kDa outer membrane transporter that is iron repressed and induced by MpeR, an AraC-like regulator, under iron-deplete conditions (Hollander et al., 2011). FetA is phase variable via slipped-strand mispairing (Carson et al., 1999). Additionally, MpeR is regulated by Fur and is pathogen specific, suggesting FetA is potentially upregulated as a virulence factor under iron limiting conditions (Snyder and Saunders, 2006; Marri et al., 2010; Jackson et al., 2010).

Repressed under iron replete conditions, both TDTs, TdfF and TdfG, have been implicated in iron acquisition by Ngo. TdfF, an 80 kDa outer membrane protein, is produced exclusively by the pathogenic Neisseria, which could suggest importance as a virulence factor (Turner et al., 2001). While no ligand has been identified to interact with TdfF, in some strains of Ngo, TdfF does contribute to intracellular survival in a TonB-dependent way (Hagen and Cornelissen, 2006). Utilizing the FA1090 Ngo sequence for bioinformatic analysis, the largest of the TDTs at 136 kDa, TdfG is exclusive to Ngo and Neisseria elongota (Turner et al., 2001; Marri et al., 2010). Like TdfF, no ligand has been identified for TdfG and little more is known about how TdfG contributes to Ngo growth or survival in humans. Thus far, little is known about the regulation of gene expression for either TdfF or TdfG, though a Fur-independent mechanism has been proposed for TdfG regulation (Jackson et al., 2010).

Host iron cycling: Infection and inflammation

Bacterial infection and inflammation act as signals for the host to deplete iron by activating an acute phase response and/or upregulating nutrient sequestration mechanisms (Weinberg, 1975; Ganz and Nemeth, 2015; Cornelissen, 2018; Golonka et al., 2019). Low blood iron during the first 24 hours of infection in patients was first described in the 1940s (Cartwright et al., 1946). Cytokines and tissue damage from inflammation are known to induce hepcidin production in the liver, promoting iron, heme, and Hb sequestration by macrophages and other iron-storage cells (Nemeth et al., 2004a; Armitage et al., 2011; Ganz and Nemeth, 2015; Ross, 2017). As serum iron levels dip below physiological levels of 10 to 30 µM, erythropoiesis, or the synthesis of erythrocytes, is inhibited freeing the iron for other processes (Ganz and Nemeth, 2015).

Ngo can invade cells, including macrophages and neutrophils which are the first immune cells to arrive at the site of infection (Zughaier et al., 2014). Iron retention in macrophages could be particularly beneficial for gonococcal infection, as iron retention in macrophages inhibits nitric oxide formation which aids in killing of intracellular bacteria (Nairz et al., 2014). Interestingly, upon infection of monocytes and macrophages, Ngo can upregulate hepcidin and downregulate ferroportin, resulting in an overall increase of iron retention (Zughaier et al., 2014). Ngo and N. meningitidis reduce expression of the host transferrin receptor in infected epithelial cells (Bonnah et al., 2000; Bonnah et al., 2004). The gene expression profiles of gonococcal or meningococcal infected cells mimic cells propagated in a low-iron environment, suggesting infection of these cells either shuttles all available iron to the infecting pathogens, generating a low-iron environment for the eukaryotic cells, or a signal from the pathogens may alter the regulatory network (Bonnah et al., 2004).

Perspectives: Potential pathways for treatment and prevention

TDTs have been suggested as vaccine candidates because they are highly conserved, present in pathogenic Neisseria, and most are not subject to high-frequency antigenic variation (Cornelissen et al., 2000; Cornelissen, 2008; Martinez-Martinez et al., 2011; Noinaj et al., 2012a; Cash et al., 2015; Frandoloso et al., 2015; Martínez-Martínez et al., 2016; Martinez-Martinez et al., 2016; Rice et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2018; Russell et al., 2019). This review summarizes the important iron metalloproteins and tissue specialization involved in neisserial pathogenesis. TbpA is essential for infection; LbpA, aids in pathogenesis; HpuAB is upregulated in females during the first half of their menstrual cycle; and TdfF is essential for intracellular survival. Consequently, these iron-regulated TDTs are also attractive targets for future therapeutics.

Neisseria species have the ability to capitalize on many mammalian nutritional immunity tactics by utilizing the iron from these chelating proteins. TbpA and LbpA bind only the human versions of transferrin and lactoferrin, respectively, suggesting a tightly co-evolved system of nutrient acquisition. Some potential iron sinks have not been assessed for their ability to support neisserial growth. For example, no evidence is available on whether Neisseria are capable of exploiting Lcn2, ferritin, or NRAMP-1, all of which are upregulated at infection sites in response to infection/inflammation. Human calprotectin is found in high concentrations in PMNs, and recently, calprotectin has been described as binding iron with high affinity (Urban et al., 2009; Nakashige et al., 2015). Further, the TDT, TdfH, binds to and utilizes the Zn bound to calprotectin (Jean et al., 2016). Thus, calprotectin is in close proximity to Ngo during infection and the interaction between calprotectin and Ngo has been described; however, calprotectin binds Fe(II) with high affinity, whereas all known Ngo iron sources are Fe(III), making calprotectin an unlikely source of iron for Ngo (Nakashige et al., 2015). It is possible that TDTs can bind to and utilize metals from multiple iron sources, thus it is important to assess potential metal sources in an unbiased way.

Author contributions

JS and AG completed the literature review and manuscript drafting. JS edited based on comments by CC. CC reviewed and proofread the manuscript and acquired funding. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, award numbers U19AI144182, R01AI127793, and R01AI125421 to CC. The funder had no role in data collection, synthesis, analysis, interpretation, or management of the data presented in this review. The funder had no role in review generation and revision, or in the decision to submit this review for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the support from the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agarwal, S., King, C. A., Klein, E. K., Soper, D. E., Rice, P. A., Wetzler, L. M., et al. (2005). The gonococcal fur-regulated tbpA and tbpB genes are expressed during natural mucosal gonococcal infection. Infect. Immun. 73, 4281–4287. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4281-4287.2005

Aisen, P., Leibman, A., Zweier, J. (1978). Stoichiometric and site characteristics of the binding of iron to human transferrin. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 1930–1937. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)62337-9

Alexander, D. B., Iigo, M., Yamauchi, K., Suzui, M., Tsuda, H. (2012). Lactoferrin: An alternative view of its role in human biological fluids. Biochem. Cell Biol. 90, 279–306. doi: 10.1139/o2012-013

Anderson, J. E., Hobbs, M. M., Biswas, G. D., Sparling, P. F. (2003). Opposing selective forces for expression of the gonococcal lactoferrin receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 1325–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03496.x

Anderson, J. E., Leone, P. A., Miller, W. C., Chen, C., Hobbs, M. M., Sparling, P. F. (2001). Selection for expression of the gonococcal hemoglobin receptor during menses. J. Infect. Dis. 184, 1621–1623. doi: 10.1086/324564

Anderson, J. E., Sparling, P. F., Cornelissen, C. N. (1994). Gonococcal transferrin-binding protein 2 facilitates but is not essential for transferrin utilization. J. Bacteriol. 176, 3162–3170. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3162-3170.1994

Andreini, C., Putignano, V., Rosato, A., Banci, L. (2018). The human iron-proteome. Metallomics 10, 1223–1231. doi: 10.1039/c8mt00146d

Andrews, N. C., Ganz, T. (2019). The molecular basis of iron metabolism (Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd).

Anzaldi, L. L., Skaar, E. P. (2010). Overcoming the heme paradox: Heme toxicity and tolerance in bacterial pathogens. Infect. Immun. 78, 4977–4989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00613-10

Armitage, A. E., Eddowes, L. A., Gileadi, U., Cole, S., Spottiswoode, N., Selvakumar, T. A., et al. (2011). Hepcidin regulation by innate immune and infectious stimuli. Blood 118, 4129–4139. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-351957

Baker, H. M., Baker, E. N. (2004). Lactoferrin and iron: Structural and dynamic aspects of binding and release. Biometals 17, 209–216. doi: 10.1023/B:BIOM.0000027694.40260.70

Baker, E. N., Baker, H. M., Kidd, R. D. (2002). Lactoferrin and transferrin: Functional variations on a common structural framework. Biochem. Cell Biol. 80, 27–34. doi: 10.1139/o01-153

Baldwin, J. M. (1975). Structure and function of haemoglobin. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 29, 225–320. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(76)90024-9

Bao, G., Clifton, M., Hoette, T. M., Mori, K., Deng, S.-X., Qiu, A., et al. (2010). Iron traffics in circulation bound to a siderocalin (Ngal)-catechol complex. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 602–609. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.402

Belkacem, A., Caumes, E., Ouanich, J., Jarlier, V., Dellion, S., Cazenave, B., et al. (2013). Changing patterns of disseminated gonococcal infection in France: cross-sectional data 2009-2011. Sex Transm. Infect. 89, 613–615. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051119

Biswas, G. D., Anderson, J. E., Chen, C. J., Cornelissen, C. N., Sparling, P. F. (1999). Identification and functional characterization of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae lbpB gene product. Infect. Immun. 67, 455–459. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.1.455-459.1999

Biswas, G. D., Sparling, P. F. (1995). Characterization of lbpA, the structural gene for a lactoferrin receptor in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 63, 2958–2967. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2958-2967.1995

Blanton, K. J., Biswas, G. D., Tsai, J., Adams, J., Dyer, D. W., Davis, S. M., et al. (1990). Genetic evidence that Neisseria gonorrhoeae produces specific receptors for transferrin and lactoferrin. J. Bacteriol. 172, 5225–5235. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5225-5235.1990

Bonnah, R. A., Lee, S. W., Vasquez, B. L., Enns, C. A., So, M. (2000). Alteration of epithelial cell transferrin-iron homeostasis by Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Cell Microbiol. 2, 207–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00042.x

Bonnah, R. A., Muckenthaler, M. U., Carlson, H., Minana, B., Enns, C. A., Hentze, M. W., et al. (2004). Expression of epithelial cell iron-related genes upon infection by Neisseria meningitidis. Cell Microbiol. 6, 473–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00376.x

Bonnah, R. A., Schryvers, A. B. (1998). Preparation and characterization of Neisseria meningitidis mutants deficient in production of the human lactoferrin-binding proteins LbpA and LbpB. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3080–3090. doi: 10.1128/JB.180.12.3080-3090.1998

Brock, J. H. (1999). Benefits and dangers of iron during infection. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2, 507–510. doi: 10.1097/00075197-199911000-00013

Broekhuyse, R. M. (1974). Tear lactoferrin: A bacteriostatic and complexing protein. Invest. Ophthalmol. 13, 550–554.

Carson, S. D., Klebba, P. E., Newton, S. M., Sparling, P. F. (1999). Ferric enterobactin binding and utilization by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 181, 2895–2901. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.9.2895-2901.1999

Cartwright, G. E., Lauritsen, M. A., Jones, P. J., Merrill, I. M., Wintrobe, M. M. (1946). The anemia of infection, hypoferremia, hypercupremia, and alterations in porphyrin metabolism in patients. J. Clin. Invest. 25, 65–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI101690

Cash, D. R., Noinaj, N., Buchanan, S. K., Cornelissen, C. N. (2015). Beyond the crystal structure: Insight into the function and vaccine potential of TbpA expressed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 83, 4438–4449. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00762-15

Chakraborty, S., Kaur, S., Guha, S., Batra, S. K. (2012). The multifaceted roles of neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL) in inflammation and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1826, 129–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.03.008

Chan, C., Andisi, V. F., Ng, D., Ostan, N., Yunker, W. K., Schryvers, A. B. (2018). Are lactoferrin receptors in gram-negative bacteria viable vaccine targets? Biometals 31, 381–398. doi: 10.1007/s10534-018-0105-7

Chen, C. J., Elkins, C., Sparling, P. F. (1998). Phase variation of hemoglobin utilization in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 66, 987–993. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.3.987-993.1998

Cohen, M. S., Britigan, B. E., French, M., Bean, K. (1987). Preliminary observations on lactoferrin secretion in human vaginal mucus: Variation during the menstrual cycle, evidence of hormonal regulation, and implications for infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 157, 1122–1125. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(87)80274-0

Cornelissen, C. N. (2008). Identification and characterization of gonococcal iron transport systems as potential vaccine antigens. Future Microbiol. 3, 287–298. doi: 10.2217/17460913.3.3.287

Cornelissen, C. N. (2018). Subversion of nutritional immunity by the pathogenic Neisseriae. Pathog. Dis. 76. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx112

Cornelissen, C. N., Anderson, J. E., Boulton, I. C., Sparling, P. F. (2000). Antigenic and sequence diversity in gonococcal transferrin-binding protein a. Infect. Immun. 68, 4725–4735. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.8.4725-4735.2000

Cornelissen, C. N., Anderson, J. E., Sparling, P. F. (1997a). Characterization of the diversity and the transferrin-binding domain of gonococcal transferrin-binding protein 2. Infect. Immun. 65, 822–828. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.822-828.1997

Cornelissen, C. N., Anderson, J. E., Sparling, P. F. (1997b). Energy-dependent changes in the gonococcal transferrin receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 26, 25–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5381914.x

Cornelissen, C. N., Biswas, G. D., Tsai, J., Paruchuri, D. K., Thompson, S. A., Sparling, P. F. (1992). Gonococcal transferrin-binding protein 1 is required for transferrin utilization and is homologous to TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors. J. Bacteriol. 174, 5788–5797. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5788-5797.1992

Cornelissen, C. N., Hollander, A. (2011). TonB-dependent transporters expressed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Front. Microbiol. 2, 117. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00117

Cornelissen, C. N., Kelley, M., Hobbs, M. M., Anderson, J. E., Cannon, J. G., Cohen, M. S., et al. (1998). The transferrin receptor expressed by gonococcal strain FA1090 is required for the experimental infection of human male volunteers. Mol. Microbiol. 27, 611–616. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00710.x

Cornelissen, C. N., Sparling, P. F. (1996). Binding and surface exposure characteristics of the gonococcal transferrin receptor are dependent on both transferrin-binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1437–1444. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1437-1444.1996

Correnti, C., Strong, R. K. (2012). Mammalian siderophores, siderophore-binding lipocalins, and the labile iron pool. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13524–13531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.311829

Criss, A. K., Seifert, H. S. (2012). A bacterial siren song: Intimate interactions between Neisseria and neutrophils. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 178–190. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2713

Cyr, S. St., Barbee, L., Workowski, K. A., Bachmann, L. H., Pham, C., Schlanger, K., et al. (2020). Update to CDC's treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. Morb. Mortality Weekly Rep. 69, 1911–6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a6

Delaby, C., Pilard, N., Hetet, G., Driss, F., Grandchamp, B., Beaumont, C., et al. (2005). A physiological model to study iron recycling in macrophages. Exp. Cell Res. 310, 43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.002

Devireddy, L. R., Hart, D. O., Goetz, D. H., Green, M. R. (2010). A mammalian siderophore synthesized by an enzyme with a bacterial homolog involved in enterobactin production. Cell 141, 1006–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.040

Duran, G. N., Özbil, M. (2021). Structural rearrangement of Neisseria meningitidis transferrin binding protein a (TbpA) prior to human transferrin protein (hTf) binding. Turkish J. Chem. 45, 1146–1154. doi: 10.3906/kim-2102-25

Fifer, H., Livermore, D. M., Uthayakumaran, T., Woodford, N., Cole, M. J. (2021). What’s left in the cupboard? Older antimicrobials for treating gonorrhoea. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76, 1215–20. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa559

Flanagan, J. L., Willcox, M. D. (2009). Role of lactoferrin in the tear film. Biochimie 91, 35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.07.007

Frandoloso, R., Martinez-Martinez, S., Calmettes, C., Fegan, J., Costa, E., Curran, D., et al. (2015). Nonbinding site-directed mutants of transferrin binding protein b exhibit enhanced immunogenicity and protective capabilities. Infect. Immun. 83, 1030–1038. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02572-14

Ganz, T., Nemeth, E. (2009). Iron sequestration and anemia of inflammation. Semin. Hematol. 46, 387–393. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2009.06.001

Ganz, T., Nemeth, E. (2015). Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 500–510. doi: 10.1038/nri3863

Goetz, D. H., Holmes, M. A., Borregaard, N., Bluhm, M. E., Raymond, K. N., Strong, R. K. (2002). The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol. Cell 10, 1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00708-6

Golonka, R., Yeoh, B. S., Vijay-Kumar, M. (2019). The iron tug-of-War between bacterial siderophores and innate immunity. J. Innate Immun. 11, 249–262. doi: 10.1159/000494627

Gray-Owen, S. D., Schryvers, A. B. (1996). Bacterial transferrin and lactoferrin receptors. Trends Microbiol. 4, 185–191. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10025-1

Guerinot, M. L. (1994). Microbial iron transport. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48, 743–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003523

Hagen, T. A., Cornelissen, C. N. (2006). Neisseria gonorrhoeae requires expression of TonB and the putative transporter TdfF to replicate within cervical epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 1144–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05429.x

Hare, S. A. (2017). Diverse structural approaches to haem appropriation by pathogenic bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1865, 422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.01.006

Hollander, A., Mercante, A. D., Shafer, W. M., Cornelissen, C. N. (2011). The iron-repressed, AraC-like regulator MpeR activates expression of fetA in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 79, 4764–4776. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05806-11

Hood, M. I., Skaar, E. P. (2012). Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 525–537. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2836

Irwin, S. W., Averil, N., Cheng, C. Y., Schryvers, A. B. (1993). Preparation and analysis of isogenic mutants in the transferrin receptor protein genes, tbpA and tbpB, from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 8, 1125–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01657.x

Jackson, L. A., Ducey, T. F., Day, M. W., Zaitshik, J. B., Orvis, J., Dyer, D. W. (2010). Transcriptional and functional analysis of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae fur regulon. J. Bacteriol. 192, 77–85. doi: 10.1128/JB.00741-09

Jean, S., Juneau, R. A., Criss, A. K., Cornelissen, C. N. (2016). Neisseria gonorrhoeae evades calprotectin-mediated nutritional immunity and survives neutrophil extracellular traps by production of TdfH. Infect. Immun. 84, 2982–2994. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00319-16

Kammerman, M. T., Bera, A., Wu, R., Harrison, S. A., Maxwell, C. N., Lundquist, K., et al. (2020). Molecular insight into TdfH-mediated zinc piracy from human calprotectin by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. mBio 11, 00949-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00949-20

Kassa, T., Jana, S., Meng, F., Alayash, A. I. (2016). Differential heme release from various hemoglobin redox states and the upregulation of cellular heme oxygenase-1. FEBS Open Bio 6, 876–884. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12103

Khan, F. A., Fisher, M. A., Khakoo, R. A. (2007). Association of hemochromatosis with infectious diseases: Expanding spectrum. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 11, 482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.04.007

Kjeldsen, L., Cowland, J. B., Borregaard, N. (2000). Human neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and homologous proteins in rat and mouse. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1482, 272–283. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(00)00152-7

Klebba, P. E., Rutz, J. M., Liu, J., Murphy, C. K. (1993). Mechanisms of TonB-catalyzed iron transport through the enteric bacterial cell envelope. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25, 603–611. doi: 10.1007/bf00770247

Kristiansen, M., Graversen, J. H., Jacobsen, C., Sonne, O., Hoffman, H. J., Law, S. K., et al. (2001). Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature 409, 198–201. doi: 10.1038/35051594

Kruzel, M. L., Harari, Y., Chen, C. Y., Castro, G. A. (2000). Lactoferrin protects gut mucosal integrity during endotoxemia induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Inflammation 24, 33–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1006935908960

Lepanto, M. S., Rosa, L., Paesano, R., Valenti, P., Cutone, A. (2019). Lactoferrin in aseptic and septic inflammation. Molecules 24. doi: 10.3390/molecules24071323

Lewis, L. A., Gipson, M., Hartman, K., Ownbey, T., Vaughn, J., Dyer, D. W. (1999). Phase variation of HpuAB and HmbR, two distinct haemoglobin receptors of Neisseria meningitidis DNM2. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 977–989. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01409.x

Lewis, L. A., Gray, E., Wang, Y. P., Roe, B. A., Dyer, D. W. (1997). Molecular characterization of hpuAB, the haemoglobin-haptoglobin-utilization operon of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 23, 737–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2501619.x

Lewis-Jones, D. I., Lewis-Jones, M. S., Connolly, R. C., Lloyd, D. C., West, C. R. (1985). Sequential changes in the antimicrobial protein concentrations in human milk during lactation and its relevance to banked human milk. Pediatr. Res. 19, 5. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198506000-00012

Lewis, L. A., Sung, M. H., Gipson, M., Hartman, K., Dyer, D. W. (1998). Transport of intact porphyrin by HpuAB, the hemoglobin-haptoglobin utilization system of Neisseria meningitidis. J. Bacteriol. 180, 6043–6047. doi: 10.1128/JB.180.22.6043-6047.1998

Li, R., Hatcher, J. D. (2020). Gonococcal arthritis (Treasure Island (FL: StatPearls Publishing). Copyright © 2020, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Liu, Y., Feinen, B., Russell, M. W. (2011). New concepts in immunity to Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Innate responses and suppression of adaptive immunity favor the pathogen, not the host. Front. Microbiol. 2, 52. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00052

Marri, P. R., Paniscus, M., Weyand, N. J., Rendón, M. A., Calton, C. M., Hernández, D. R., et al. (2010). Genome sequencing reveals widespread virulence gene exchange among human Neisseria species. PloS One 5, e11835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011835

Martinez-Martinez, S., Frandoloso, R., Gutierrez-Martin, C. B., Lampreave, F., Garcia-Iglesias, M. J., Perez-Martinez, C., et al. (2011). Acute phase protein concentrations in colostrum-deprived pigs immunized with subunit and commercial vaccines against glässer’s disease. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 144, 61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.07.002

Martínez-Martínez, S., Frandoloso, R., Rodríguez-Ferri, E.-F., García-Iglesias, M.-J., Pérez-Martínez, C., Álvarez-Estrada, Á., et al. (2016). A vaccine based on a mutant transferrin binding protein b of Haemophilus parasuis induces a strong T-helper 2 response and bacterial clearance after experimental infection. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 179, 18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2016.07.011

Martinez-Martinez, S., Rodriguez-Ferri, E. F., Frandoloso, R., Garrido-Pavon, J. J., Zaldivar-Lopez, S., Barreiro, C., et al. (2016). Molecular analysis of lungs from pigs immunized with a mutant transferrin binding protein b-based vaccine and challenged with Haemophilus parasuis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 48, 69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2016.08.005

Masson, P. L., Heremans, J. F. (1968). Metal-combining properties of human lactoferrin (red milk protein). Eur. J. Biochem. 6, 579–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00484.x

Maurakis, S., Keller, K., Maxwell, C. N., Pereira, K., Chazin, W. J., Criss, A. K., et al. (2019). The novel interaction between Neisseria gonorrhoeae TdfJ and human S100A7 allows gonococci to subvert host zinc restriction. PloS Pathog. 15, e1007937. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007937

Mickelsen, P. A., Sparling, P. F. (1981). Ability of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and commensal Neisseria species to obtain iron from transferrin and iron compounds. Infect. Immun. 33, 555–564. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.2.555-564.1981

Miethke, M., Marahiel, M. A. (2007). Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71, 413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07

Nairz, M., Haschka, D., Demetz, E., Weiss, G. (2014). Iron at the interface of immunity and infection. Front. Pharmacol. 5, 152. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00152

Nakashige, T. G., Zhang, B., Krebs, C., Nolan, E. M. (2015). Human calprotectin is an iron-sequestering host-defense protein. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 765–771. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1891

Na, N., Ouyang, J., Taes, Y. E., Delanghe, J. R. (2005). Serum free hemoglobin concentrations in healthy individuals are related to haptoglobin type. Clin. Chem. 51, 1754–1755. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.055657

Nemeth, E., Rivera, S., Gabayan, V., Keller, C., Taudorf, S., Pedersen, B. K., et al. (2004a). IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1271–1276. doi: 10.1172/JCI200420945

Nemeth, E., Tuttle, M. S., Powelson, J., Vaughn, M. B., Donovan, A., Ward, D. M., et al. (2004b). Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 306, 2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742

Noinaj, N., Buchanan, S. K. (2014). Structural insights into the transport of small molecules across membranes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 27, 8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.02.007

Noinaj, N., Buchanan, S. (2018). Editorial overview: Membranes and their embedded molecular machines. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 51, vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.10.005

Noinaj, N., Buchanan, S. K., Cornelissen, C. N. (2012a). The transferrin-iron import system from pathogenic Neisseria species. Mol. Microbiol. 86, 246–257. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12002

Noinaj, N., Cornelissen, C. N., Buchanan, S. K. (2013). Structural insight into the lactoferrin receptors from pathogenic Neisseria. J. Struct. Biol. 184, 83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.02.009

Noinaj, N., Easley, N. C., Oke, M., Mizuno, N., Gumbart, J., Boura, E., et al. (2012b). Structural basis for iron piracy by pathogenic Neisseria. Nature 483, 53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10823

Noinaj, N., Guillier, M., Barnard, T. J., Buchanan, S. K. (2010). TonB-dependent transporters: regulation, structure, and function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134247

Noinaj, N., Gumbart, J. C., Buchanan, S. K. (2017). The beta-barrel assembly machinery in motion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 197–204. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.191

Noto, J. M., Cornelissen, C. N. (2008). Identification of TbpA residues required for transferrin-iron utilization by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 76, 1960–1969. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00020-08

Nuijens, J. H., Abbink, J. J., Wachtfogel, Y. T., Colman, R. W., Eerenberg, A. J., Dors, D., et al. (1992). Plasma elastase alpha 1-antitrypsin and lactoferrin in sepsis: evidence for neutrophils as mediators in fatal sepsis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 119, 159–168.

Ohnishi, M., Golparian, D., Shimuta, K., Saika, T., Hoshina, S., Iwasaku, K., et al. (2011). Is Neisseria gonorrhoeae initiating a future era of untreatable gonorrhea?: Detailed characterization of the first strain with high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 3538–3545. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00325-11

Okubo, K., Kamiya, M., Urano, Y., Nishi, H., Herter, J. M., Mayadas, T., et al. (2016). Lactoferrin suppresses neutrophil extracellular traps release in inflammation. EBioMedicine 10, 204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.012

Page, M. G. P. (2019). The role of iron and siderophores in infection, and the development of siderophore antibiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 69, S529–s537. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz825

Pantopoulos, K., Porwal, S. K., Tartakoff, A., Devireddy, L. (2012). Mechanisms of mammalian iron homeostasis. Biochemistry 51, 5705–5724. doi: 10.1021/bi300752r

Pettersson, A., Maas, A., Tommassen, J. (1994). Identification of the iroA gene product of Neisseria meningitidis as a lactoferrin receptor. J. Bacteriol. 176, 1764–1766. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1764-1766.1994

Portnoy, J., Mendelson, J., Clecner, B., Heisler, L. (1974). Asymptomatic gonorrhea in the male. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 110, 169.

Postle, K. (1993). TonB protein and energy transduction between membranes. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25, 591–601. doi: 10.1007/bf00770246

Rageh, A. A., Ferrington, D. A., Roehrich, H., Yuan, C., Terluk, M. R., Nelson, E. F., et al. (2016). Lactoferrin expression in human and murine ocular tissue. Curr. Eye Res. 41, 883–889. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2015.1075220

Raymond, K. N., Dertz, E. A., Kim, S. S. (2003). Enterobactin: An archetype for microbial iron transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 3584–3588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630018100

Renauld-Mongénie, G., Poncet, D., Mignon, M., Fraysse, S., Chabanel, C., Danve, B., et al. (2004). Role of transferrin receptor from a Neisseria meningitidis tbpB isotype II strain in human transferrin binding and virulence. Infect. Immun. 72, 3461–3470. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3461-3470.2004

Retzer, M. D., Yu, R., Zhang, Y., Gonzalez, G. C., Schryvers, A. B. (1998). Discrimination between apo and iron-loaded forms of transferrin by transferrin binding protein b and its n-terminal subfragment. Microb. Pathog. 25, 175–180. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0226

Rice, P. A. (2005). Gonococcal arthritis (disseminated gonococcal infection). Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 19, 853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2005.07.003

Rice, P. A., Shafer, W. M., Ram, S., Jerse, A. E. (2017). Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Drug resistance, mouse models, and vaccine development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 71, 665–686. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093530

Rohde, K. H., Dyer, D. W. (2003). Mechanisms of iron acquisition by the human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Front. Biosci. 33. doi: 10.2741/1133

Rohde, K. H., Dyer, D. W. (2004). Analysis of haptoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin interactions with the Neisseria meningitidis TonB-dependent receptor HpuAB by flow cytometry. Infect. Immun. 72, 2494–2506. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2494-2506.2004

Rohde, K. H., Gillaspy, A. F., Hatfield, M. D., Lewis, L. A., Dyer, D. W. (2002). Interactions of haemoglobin with the Neisseria meningitidis receptor HpuAB: The role of TonB and an intact proton motive force. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 335–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02745.x

Ross, A. C. (2017). Impact of chronic and acute inflammation on extra- and intracellular iron homeostasis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 106, 1581s–1587s. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.155838

Russell, M. W., Jerse, A. E., Gray-Owen, S. D. (2019). Progress toward a gonococcal vaccine: The way forward. Front. Immunol. 10, 2417. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02417

Schmidt, K. A., Schneider, H., Lindstrom, J. A., Boslego, J. W., Warren, R. A., Van De Verg, L., et al. (2001). Experimental gonococcal urethritis and reinfection with homologous gonococci in male volunteers. Sex Transm. Dis. 28, 555–564. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200110000-00001

Schryvers, A. B., Morris, L. J. (1988). Identification and characterization of the human lactoferrin-binding protein from Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 56, 1144–1149. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1144-1149.1988

Schryvers, A. B., Stojiljkovic, I. (1999). Iron acquisition systems in the pathogenic Neisseria. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 1117–1123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01411.x

Sia, A. K., Allred, B. E., Raymond, K. N. (2013). Siderocalins: Siderophore binding proteins evolved for primary pathogen host defense. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.11.014

Snyder, L. A., Saunders, N. J. (2006). The majority of genes in the pathogenic Neisseria species are present in non-pathogenic Neisseria lactamica, including those designated as ‘virulence genes’. BMC Genomics 7, 128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-128

Springer, C., Salen, P. (2020). Gonorrhea (Treasure Island (FL: StatPearls Publishing). Copyright © 2020, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Strange, H. R., Zola, T. A., Cornelissen, C. N. (2011). The fbpABC operon is required for ton-independent utilization of xenosiderophores by Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain FA19. Infect. Immun. 79, 267–278. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00807-10

Tsai, J., Dyer, D. W., Sparling, P. F. (1988). Loss of transferrin receptor activity in Neisseria meningitidis correlates with inability to use transferrin as an iron source. Infect. Immun. 56, 3132–3138. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3132-3138.1988

Turner, P. C., Thomas, C. E., Stojiljkovic, I., Elkins, C., Kizel, G., Ala’aldeen, D. A. A., et al. (2001). Neisserial TonB-dependent outer-membrane proteins: Detection, regulation and distribution of three putative candidates identified from the genome sequences. Microbiol. (Reading) 147, 1277–1290. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-5-1277

Unemo, M., Seifert, H. S., Hook, E. W., Hawkes, S., Ndowa, F., Dillon, J. R. (2019). Gonorrhoea. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 5, 79. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0128-6

Urban, C. F., Ermert, D., Schmid, M., Abu-Abed, U., Goosmann, C., Nacken, W., et al. (2009). Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PloS Pathog. 5, e1000639. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639

Valenti, P., Rosa, L., Capobianco, D., Lepanto, M. S., Schiavi, E., Cutone, A., et al. (2018). Role of lactobacilli and lactoferrin in the mucosal cervicovaginal defense. Front. Immunol. 9, 376. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00376

Walker, C. K., Sweet, R. L. (2011). Gonorrhea infection in women: Prevalence, effects, screening, and management. Int. J. Womens Health 3, 197–206. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.S13427

Wandersman, C., Delepelaire, P. (2004). Bacterial iron sources: from siderophores to hemophores. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58, 611–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123811

Weinberg, E. D. (1975). Nutritional immunity. host’s attempt to withold iron from microbial invaders. Jama 231, 39–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.1975.03240130021018

Weiss, G. (1999). Iron and anemia of chronic disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 69, S12–S17. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055Suppl.69012.x

West, S. E., Sparling, P. F. (1987). Aerobactin utilization by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and cloning of a genomic DNA fragment that complements Escherichia coli fhuB mutations. J. Bacteriol. 169, 3414–3421. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3414-3421.1987

Xiao, X., Yeoh, B. S., Vijay-Kumar, M. (2017). Lipocalin 2: An emerging player in iron homeostasis and inflammation. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 37, 103–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064559

Yadav, R., Govindan, S., Daczkowski, C., Mesecar, A., Chakravarthy, S., Noinaj, N. (2021). Structural insight into the dual function of LbpB in mediating neisserial pathogenesis. Elife 10, e71683. doi: 10.7554/eLife.71683.sa2

Yadav, R., Noinaj, N., Ostan, N., Moraes, T., Stoudenmire, J., Maurakis, S., et al. (2019). Structural basis for evasion of nutritional immunity by the pathogenic Neisseriae. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2981. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02981

Keywords: transferrin, hemoglobin, lactoferrin, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, iron, nutritional immunity, siderophore

Citation: Stoudenmire JL, Greenawalt AN and Cornelissen CN (2022) Stealthy microbes: How Neisseria gonorrhoeae hijacks bulwarked iron during infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12:1017348. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1017348

Received: 11 August 2022; Accepted: 30 August 2022;

Published: 15 September 2022.

Edited by:

Mauricio H Pontes, College of Medicine, The Pennsylvania State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jennifer Angeline Gaddy, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Stoudenmire, Greenawalt and Cornelissen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cynthia Nau Cornelissen, Y2Nvcm5lbGlzc2VuQGdzdS5lZHU=

Julie Lynn Stoudenmire

Julie Lynn Stoudenmire Ashley Nicole Greenawalt

Ashley Nicole Greenawalt Cynthia Nau Cornelissen

Cynthia Nau Cornelissen