95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. , 20 April 2021

Sec. Parasite and Host

Volume 11 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.661830

This article is part of the Research Topic Systems Biology of Hosts, Parasites and Vectors View all 11 articles

Nathan R. Allen1

Nathan R. Allen1 Aspen R. Taylor-Mew1

Aspen R. Taylor-Mew1 Toby J. Wilkinson1

Toby J. Wilkinson1 Sharon Huws2

Sharon Huws2 Helen Phillips1

Helen Phillips1 Russell M. Morphew1*†

Russell M. Morphew1*† Peter M. Brophy1†

Peter M. Brophy1†Parasite derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been proposed to play key roles in the establishment and maintenance of infection. Calicophoron daubneyi is a newly emerging parasite of livestock with many aspects of its underpinning biology yet to be resolved. This research is the first in-depth investigation of EVs released by adult C. daubneyi. EVs were successfully isolated using both differential centrifugation and size exclusion chromatography (SEC), and morphologically characterized though transmission electron microscopy (TEM). EV protein components were characterized using a GeLC approach allowing the elucidation of comprehensive proteomic profiles for both their soluble protein cargo and surface membrane bound proteins yielding a total of 378 soluble proteins identified. Notably, EVs contained Sigma-class GST and cathepsin L and B proteases, which have previously been described in immune modulation and successful establishment of parasitic flatworm infections. SEC purified C. daubneyi EVs were observed to modulate rumen bacterial populations by likely increasing microbial species diversity via antimicrobial activity. This data indicates EVs released from adult C. daubneyi have a role in establishment within the rumen through the regulation of microbial populations offering new routes to control rumen fluke infection and to develop molecular strategies to improve rumen efficiency.

Paramphistomes, commonly known as rumen fluke, have been found to infect ruminant animals worldwide (Huson et al., 2017; Huson et al., 2018). Within tropical and sub-tropical regions, rumen fluke infections cause significant production losses; yet only in recent years have rumen fluke infections been observed throughout Europe with the major species responsible confirmed as Calicophoron daubneyi (Sanabria and Romero, 2008; Jones et al., 2017). Clinical disease via adult rumen fluke is rarely reported in temperate areas, but mortality to large burdens of immature parasites has been observed in adolescent sheep and cattle (Mason et al., 2012; Millar et al., 2012).

Parasitic helminths establish long-term infections by manipulating the immune system in order to create an anti-inflammatory environment within the host (Coakley et al., 2016; Maizels and McSorley, 2016). In recent years parasite extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been recognized as key components of this strategy by transporting immunomodulatory cargo molecules (Marcilla et al., 2012). To date, there is fragmented understanding of the mechanisms underpinning EV activity with respect to immune-modulation and successful establishment of infection (Coakley et al., 2016). EVs appear the major route for macromolecule exportation from parasitic helminths, with some EVs even containing host mimicking components (Marcilla et al., 2012). EVs released by several helminth parasites have been found to deliver bioactive molecules and miRNA to host cells where they modulate host gene expression and suppress cytokine formation (Buck et al., 2014). The packaged cargo is developmentally regulated likely allowing parasite migration and establishment within the definitive host (Marcilla et al., 2012; Montaner et al., 2014; Cwiklinski et al., 2015). EVs from parasitic flatworms contain a number of established immune modulating proteins, such as FhGST-S1, the Sigma class GST (Prostaglandin synthase) from F. hepatica (LaCourse et al., 2012; Davis et al., 2019).

EVs have been confirmed to be released from the rumen fluke C. daubneyi (Huson et al., 2018). However, these EVs are yet to be studied at a molecular level or in relation to their effects on rumenal microbes. Previous studies of helminth parasites have shown they interact with their hosts gut microbiota in order to successfully establish infection whilst interrupting the ‘healthy’ microbiome that ultimately promotes the hosts health (Jenkins et al., 2018). With this in mind it is notable that relationships between gut microbiota and parasites are not fully resolved. However, evidence suggests the microbiotas involvement in regulation of the immune system ensuring appropriate responses to pathogenic organisms. However, evidence suggests the microbiotas involvement in regulation of the immune system ensuring appropriate responses to pathogenic organisms (Gensollen et al., 2016). Currently, studies into domestic livestock’s microbiota in response to helminth infections remain limited and inconsistent (Peachey et al., 2019). Specifically, the rumen microbiota has been extensively studied due to the importance of rumen microbes in the nutrition and health of the animal (Petri et al., 2013; Chaucheyras-Durand and Ossa, 2014). Growing evidence suggest the rumen microbiome is involved in a complex and intimate dialogue with the immune and metabolic functions of the host (Zaiss and Harris, 2016). Owing to the links between rumen microbiota and animal health, disturbances in the rumen ecosystem may hinder rumen functionality and lead to disease in the host (Zaiss and Harris, 2016), with studies showing a causal link between natural and experimental infections of parasitic helminths with qualitative and quantitative alterations to the intestinal microbiota in a variety of animal species (Walk et al., 2010; Broadhurst et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Cantacessi et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014). Here we unravel the proteomic profile of adult C. daubneyi EVs and explore the EV impact on the complex microbial environment contributing to their successful establishment within the host.

Adult C. daubneyi were retrieved from naturally infected bovine rumens post-slaughter in a local abattoir (mid-Wales, UK). Following collection, C. daubneyi were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, at 39°C to remove contaminating materials. Flukes were divided into batches of 30 adults and placed in 1 ml/fluke DME culture media (supplemented with 2.2 mM Ca, 2.7 mM MgSO4, 61.1 mM glucose, 1 µM serotonin and gentamycin (5 µg/ml), 15 mM HEPES), 39°C for 6 hours. Subsequently, both flukes and DME media were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C.

Prior to differential centrifugation and size exclusion chromatography EV purification, media was submitted to centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 700 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove residual debris.

C. daubneyi maintenance media was utilized in order to purify EV populations through differential centrifugation (DC) as previously described (Davis et al., 2019). Media was centrifuged at 120,000 × g for 80 min at 4°C in an Optima L-100 XP ultracentrifuge (Beckmann Coulter, High Wycombe, UK). The resulting pellet was washed in 5 ml PBS, pH 7.4 and submitted to 0.2 µm syringe filtering before the centrifugation step being repeated. The resulting pellet was suspended in 500 µl PBS and stored at -20°C.

C. daubneyi maintenance media was utilized in order to purify EV populations through size exclusion chromatography (SEC) as previously described (Davis et al., 2019). Media was concentrated using Amicon ultra-15 centrifugal filters (Merk, Millipore), with a 10 kDa MW cut off. Samples were added to the centrifugal unit and centrifuged at 4000 × g for 20 min at 4°C until an approximately 500 µl EV enriched sample remained. EV enriched samples were 0.2 µm filtered and a maximum of 500 µl passed through qEVoriginal SEC columns (IZON science, U.K) following the manufacturers protocol. Briefly, columns were equilibrated with a minimum of 10 ml of PBS prior to addition of the sample. The initial 2.5 ml flow through was discarded with the following 2.5 ml EV enriched fraction retained and stored at -20°C.

A Nanopore NP200 (IZON Science) was utilized in the quantification of SEC purified EV samples. The Nanopore was calibrated using calibration particles (CPC200, 1:1000 filtered PBS). EV samples were measured at 47 mm nanopore stretch at a 100 nA voltage under 7 mbar pressure. Particles were detected through short pulses of current and the resulting data analyzed using qNano particle analysis software (IZON, version 3.2).

DC and SEC purified EVs were fixed onto formvar/carbon coated copper grids (Agar Scientific) for TEM analysis following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 10 µl of EV-enriched sample was added to each grid and incubated for 45 min on ice. Grids were placed on the meniscus of 4% w/v uranyl acetate for 5 min on ice. Grids were then stored for a minimum of 24 hours at room temperature prior to visualization on the TEM (Jeol JEM1010 microscope at 80 kV), with EV presence confirmed through size selective criteria (30 – 200nm).

EV proteins were determined through sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) following the method of Laemmli (1970). Protein concentration was first determined using a Qubit protein assay following the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific, UK). Loading concentrations of 10 µg were aliquoted and centrifuged at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 30 minutes (S55-S rotor, Sorval MX120 centrifuge, Thermo scientific) with the resulting supernatant discarded. The EV pellet was suspended in 10 µl loading buffer and heated for 10 min at 95°C before loading into hand-cast 7 cm x 7 cm 12.5% polyacrylamide Tris/glyceine gels and subject to electrophoresis on a Protean III system (Bio-Rad, UK). Tris/Glycine/SDS buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine, 0.1% w/v SDS pH 8.3) (BioRad, U.K) was utilized for electrophoresis, with gels run at 70 V through the stacking gel and 150 V until completion. Gels were fixed (40% v/v ethanol and 10% v/v acetic acid) for one hour prior to overnight staining with colloidal Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Sigma, UK) at room temperature with gentle agitation. De-staining was achieved using 30% (v/v) methanol, 10% v/v acetic acid and gels were subsequently visualized on a GS-800 calibrated densitometer (Bio-Rad, UK) and stored in 1% acetic acid prior to trypsin digestion for mass spectrometry analysis following the protocol of Davis et al. (2019).

SEC purified EVs were concentrated to a final concentration of 200 µg in 250 µl. Sequencing grade trypsin (Roche, U.K) was diluted to 100 µg/ml and added to the EVs resulting in a final concentration of 50 µg/ml. Samples were incubated for 5 minutes at 37°C followed by centrifugation for 1 hour at 100,000 × g at 4°C (S55-S rotor, Sorval MX120 centrifuge, Thermo Scientific). The resulting supernatant was divided into 20 µl fractions and subject to LC MSMS with an injection volume of 1 µl.

Trypsin digested protein samples were suspended in 20 µl 0.1% formic acid and loaded into an Agilent 6550 iFunnel Q-TOF mass spectrometer combined with a Dual AJS ESI source 1290 series HPLC system (Agilent, Cheshire, U.K). A Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (2.1 x 50 mm 1.8 micron) was utilized with each sample injected into an enrichment column within the system at a flow rate of 2.5 µl/min using an automated micro sampler with an injection volume of 2 µl in the resuspension buffer 0.1% v/v formic acid and allowed to separate at 300 nl/min. Enrichment and separation were carried out on a polaris chip (G4240-62030, Agilent Technologies, U.K). A system of solvents was utilized over the process, solvent A (milliQ water containing 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (90% v/v acetonitrile containing 0.1% v/v formic acid). Chromatography was achieved using a linear-gradient of 3-8% solvent B over 6 seconds, 8-35% solvent B over 15 minutes, 35-90% solvent B over five minutes and finally 90% solvent B for two minutes. Resulting peak spectra data was loaded onto Agilent Qualitative analysis software (Agilent technologies LDA UK Limited, UK). Each file had compounds found by molecular feature and were saved to MGF. MASCOT (www.matrixofscience.com) was used for analysis by carrying out an MS/MS ion search, settings were set for the enzyme trypsin – allowing 2 missed cleavages, with a fixed modification of carbamidomethyl (C) and a variable modification of oxidation (M) with a peptide charge of 2+, 3+ and 4+. Each sample was then searched against an in-house database composed of a transcript for C. daubneyi (Huson et al., 2018) available to search at https://sequenceserver.ibers.aber.ac.uk/. Each of the contigs returned were then searched within an in-house copy of the transcript and the nucleotide sequence recorded. All of the contigs were then translated using ExPasy (www.expasy.com) and the sequences submitted to BLASTp analysis and subsequently searched in the Interpro database.

Rumen contents were collected from rumen-fistulated steers at Trawsgoed experimental farm (Aberystwyth, Wales) complying with the authorities of the UK Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986). Rumen contents was squeezed through a sieve allowing retention of strained ruminal fluid (SRF) that was immediately incubated at 39°C. Rumen fluid was added to anaerobic incubation medium following the protocol of Goering and Van Soest (1970), to create a 10% v/v solution. PBS was removed from SEC purified EV samples (5.52E+10 particles/ml) through centrifugation using Amicon ultra-15 centrifugal filters (Merk, Millipore) 10 kDa MWCO, with EVs resuspended in an equal volume of modified Van Soest digestion buffer. 1 ml EV solution was added to 9 ml rumen fluid/anaerobic incubation medium (n =3) and allowed to incubate for 24 hrs. For controls, EV solution was replaced with modified Van Soest digestion buffer. Rumen fluid sampling was carried out at 5 time points during the incubation period (0 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, and 24 h) and stored for downstream qPCR analysis.

DNA extractions were carried out on 1 ml rumen fluid from each of the aforementioned time points (0 hrs, 2 hrs, 4 hrs, 6 hrs and 24 hrs). Extractions were carried out using a FastDNA spin kit for soil (MP Biomedicals, USA) according to the manufacturers protocol, as described by Huws et al. (2010). Extracted DNA was quantified using the Biotech Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (Biotek Instruments Inc, USA). The Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer was calibrated prior to quantification using 1.25 µl DNase/pyrogen free water. Following quantification samples were stored at -20°C for qPCR analysis.

qPCR of 16S rDNA was undertaken to determine the effects of incubation of EVs with rumen fluid on total bacteria population as well as specifically Ruminococcus albus, Fibrobacter succinogenes, and Prevotella spp. Extracted DNA was diluted 10-fold with ddH2O. The reaction mixture (1215 µl) for each qPCR run was prepared with 1 x SYBR Geen I master mix (Applied Biosystems), 5.4 µl of each primer (Table 1) and ddH20. 10 µl of reaction mixture was added to 1 µl of each DNA sample analyzed using a Roche lightcycler 480 II (Roche diagnostics Ltd.) on a 384 well qPCR plate. A bacterial standard was prepared with equal amounts of genomic DNA as outlined by Huws et al. (2010). For each qPCR, with the exception of Prevotella spp., amplification was performed at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 58°C for 15 seconds, and 72°C for 15 seconds, and then an extension step of 72°C for 5 minutes. For the Prevotella spp. qPCR amplification was performed at 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 15 seconds, and 72°C for 15 seconds, and then an extension step of 72°C for five minutes. All qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate and assay qPCR efficiency was calculated as: efficiency=10(- 1/slope) x100. The bacterial standards were used to create a standard curve to allow for quantification of the samples. Statistical analysis of the qPCR values was undertaken in Microsoft Excel, and using repeated measures ANOVA to test for significant differences in IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0.

Table 1 Forward and reverse primer sequences used to target 16S rDNA in qPCR analysis of total bacteria, Ruminococcus albus, Fibrobacter succinogenes and Prevotella spp. DNA concentrations.

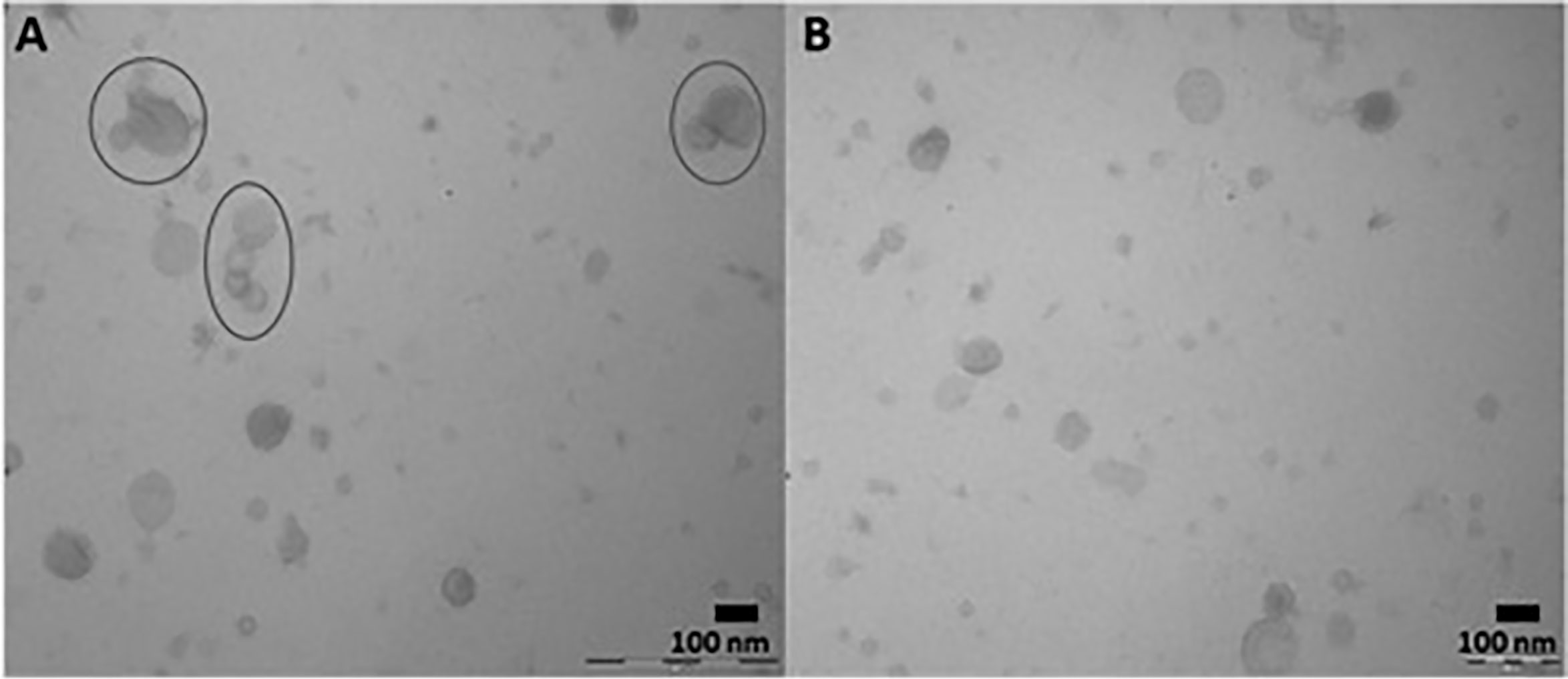

The presence of extracellular vesicles in both DC and SEC purified adult C. daubneyi samples was confirmed by the identification of membrane bound vesicles ~30-100 nm in size through transmission electron microscopy (TEM). TEM imaging demonstrated EVs present to have diverse morphologies with ruptured vesicles only identified in DC purified samples. A large number of aggregated vesicles were also observed in DC samples (Figure 1A) whilst reduced aggregation was observed in the samples isolated through SEC (Figure 1B) and, despite the inclusion of 0.2 µm filtering, background contamination was visibly present following both purification methods.

Figure 1 Representative developed TEM micrographs identifying extracellular vesicles secreted by C. daubneyi in vitro through DC and SEC isolation. (A) DC purified samples with visible aggregation of vesicles (circled) (B) SEC purified samples demonstrating a reduction in EV aggregation.

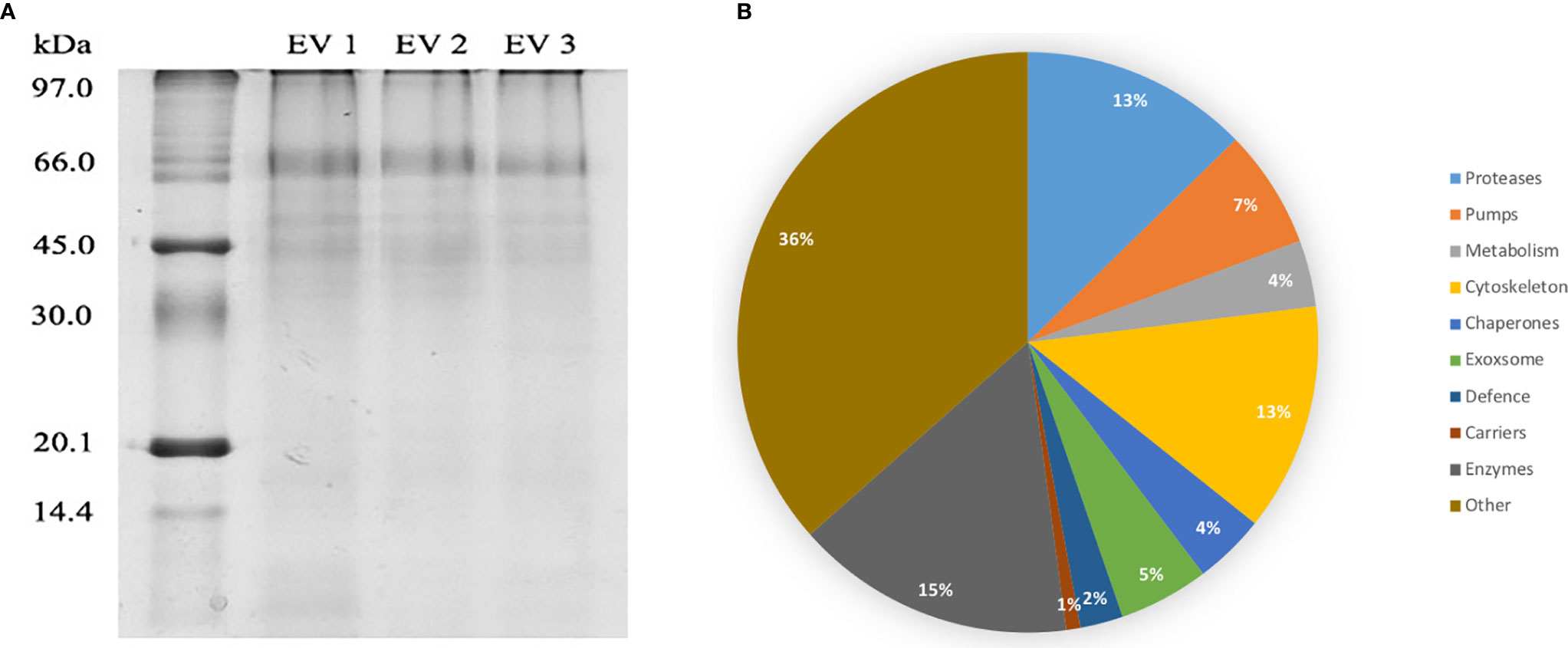

DC purified EVs were utilized to resolve the C. daubneyi whole lysed EV proteome. A GelC strategy was exploited to identify lysed EV proteins with proteins resolved on a 12.5% one-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) followed by LC-MSMS analysis with the mass spectrometry proteomics data deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD024182. Replication of lysed EV proteomic profiles confirmed reproducibility (Figure 2A). A total of 378 proteins were found to be consistent across three biological replicates (n = 3) following LC-MSMS analysis (Supplementary Material 1). EV protein abundance was quantified by the number of unique peptides present, with only protein hits above the significance threshold (>47) included as a positive identification. Quantification by the number of unique peptides elucidated the top 50 protein hits (Table 2). Further analysis of the returned proteome identified a number of common EV markers through comparison with the Exocarta database (http://exocarta.org). All 378 sequences resolved in the EV proteome were further characterized by their functionality through use of the Interpro database and sorted into 9 distinct categories: Cytoskeleton, Proteases, Enzymes, Chaperones, Metabolism, Transporters, Carrier, Exosome Biogenesis and Others as previously described by (Cwiklinski et al., 2015) (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the category with the greatest number of sequences assigned was ‘other’ encompassing all sequences with no BLAST result or a BLAST result to a hypothetical or unassigned protein accounting for 36% of the sequences. This was followed by cytoskeletal proteins accounting for 24% of proteins. The category representing the fewest number of proteins were carriers accounting for 1% of the total proteome.

Figure 2 (A) EV proteome arrays of lysed C. daubneyi EVs (n=3). EVs released in vitro were lysed and subjected to 12.5% 1D polyacrylamide gel analysis and colloidal Coomassie blue stained. All biological replicates produced a highly reproducible profile. (B) Categorization of all sequences returned from the C. daubneyi EV proteome. Proteins consistent across three replicates were submitted to Interpro and GeneOntology searches and assigned to 9 functional categories as defined by Cwiklinski et al. (2015). Proteins that did not fit any of the nine categories were placed into a final category classified as ‘other’. Cytoskeleton associated proteins accounted for 13% of the sequences resolved, Proteases 14%, Enzymes 8%, Chaperones 7%, Transporters 4%, Exosome biogenesis 3%, Metabolism 5%, Carriers 1% with Others filling the remaining 36%.

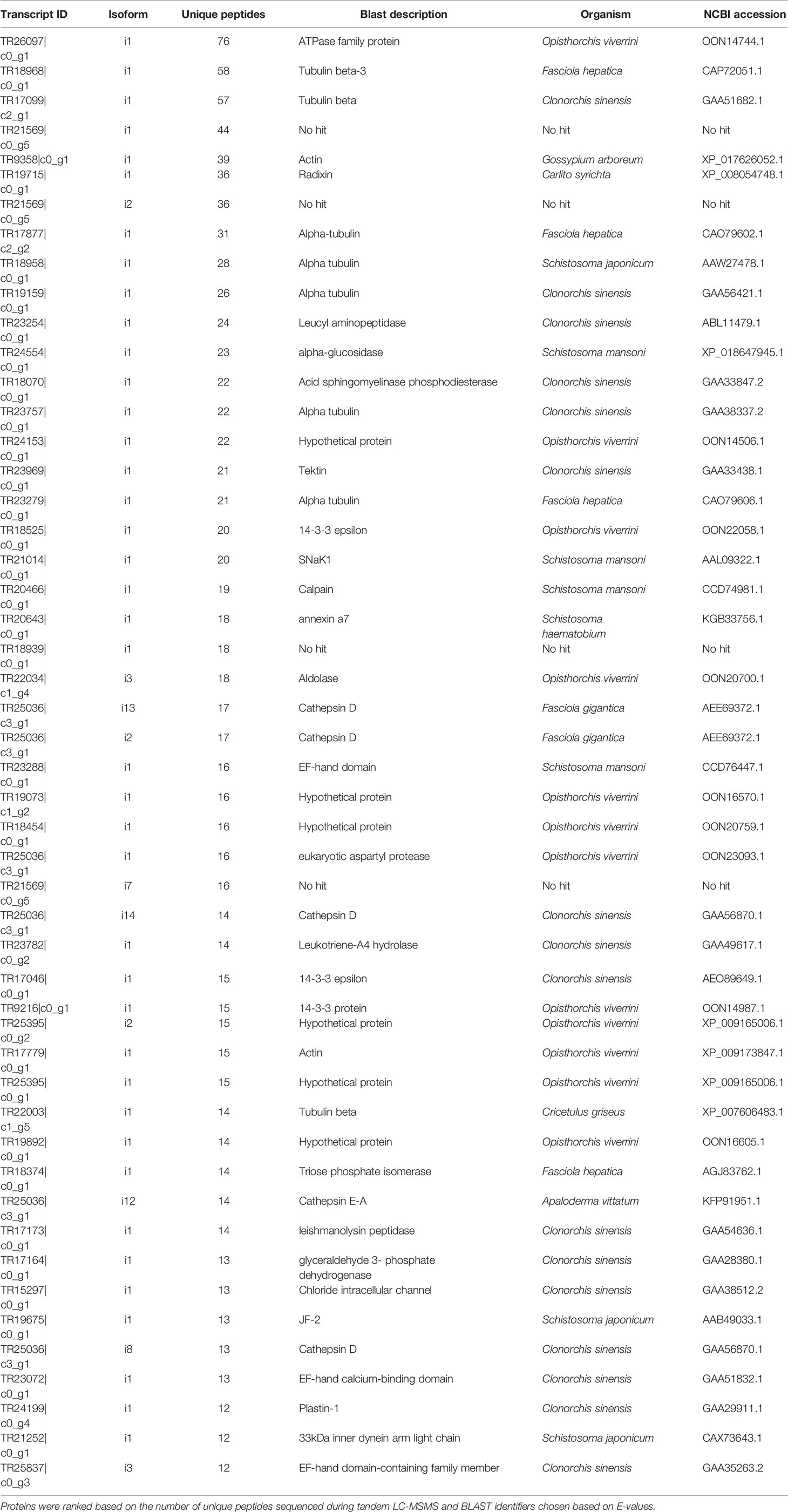

Table 2 Top 50 proteins resolved in C. daubneyi extracellular vesicles following BLAST analysis of transcript identifiers.

Following resolution of the whole EV proteomic profile, the proteins present on the external surface of EVs were investigated through trypsin cleavage from the membrane. Transcript IDs identified through LC-MSMS were translated before submission to BLASTp investigation allowing identification of protein IDs. In total, 89 proteins were identified as present upon the external surface of EVs release by adult C. daubneyi (Table 3), including a variety of well-known exosomal markers such as heat shock protein 70 and members of the tetraspanin family as defined by the Exocarta database (http://www.exocarta.com). Several membrane channel and transporter proteins were identified including ATPase, V-type H+- transporting ATPase, phospholipase and glucose transporters.

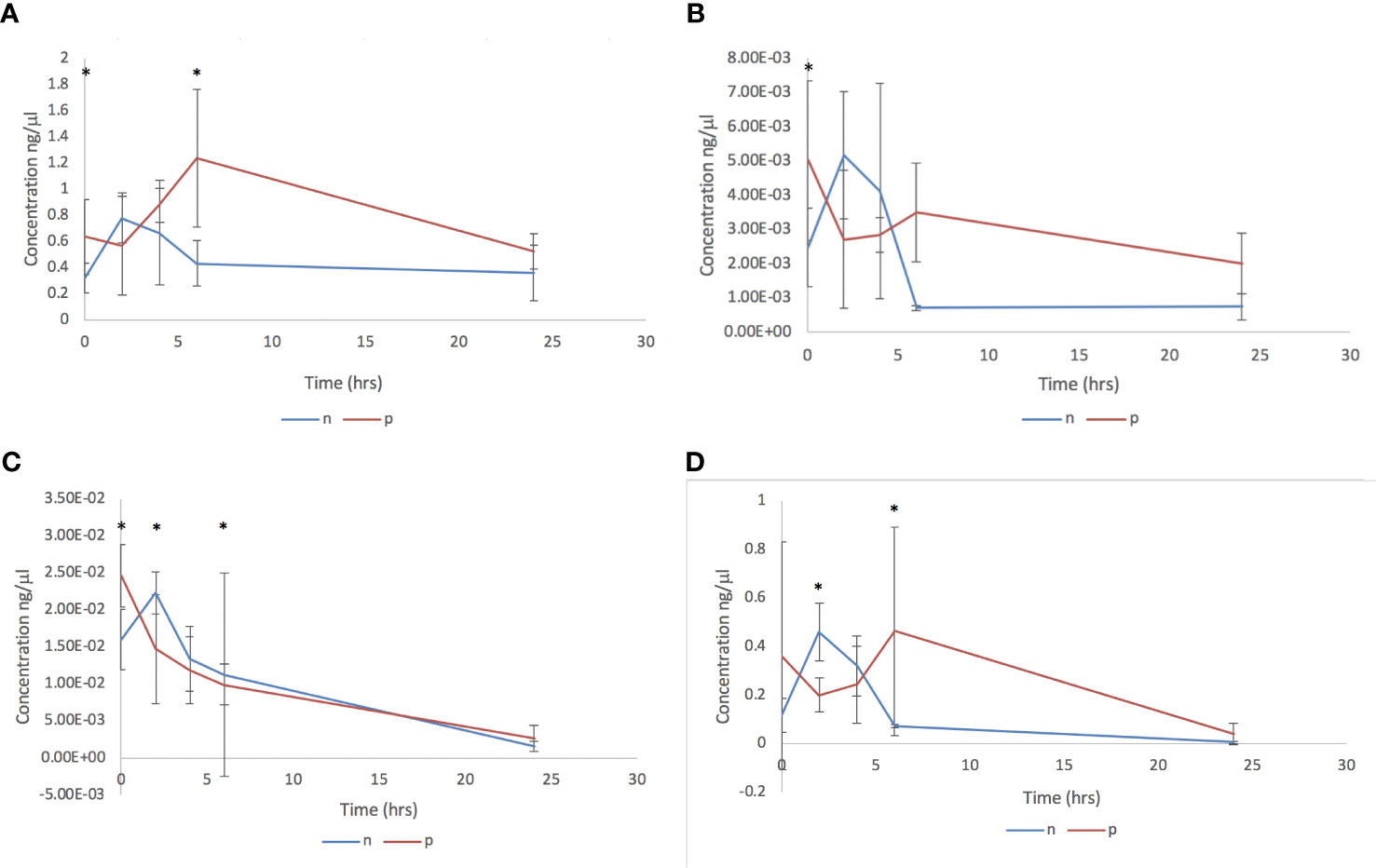

The impact of adult C. daubneyi EVs on rumen microbial populations was completed on three key ruminant bacterial species, Fibrobacter succinogenes, Ruminococcus albus and Prevotella spp, as well as on the total bacterial microbiome using 16S rDNA analysis. Quantitative PCR was undertaken on samples at five timepoints (0 hrs, 2 hrs, 4 hrs, 6 hrs and 24 hrs) to assess the impact of EVs on the rumen microbiome (Figure 3). Total Bacteria DNA concentrations ranged from 500.93 to 1236.95 ng/ml in cultures incubated in the presence of rumen fluke EVs, and from 229.93 to 656.22 ng/ml in cultures with absence of rumen fluke EVs. Fibrobacter succinogenes DNA concentration ranged from 0.471 to 7.871 ng/ml with EVs and from 0.207 to 5.384 ng/ml in the absence of EVs. Ruminococcus albus DNA concentrations ranged from 0.175 to 0.509 ng/ml with EVs, and from 0.049 to 0.526 ng/ml in the absence of rumen fluke EVs. Finally, the DNA concentrations for Prevotella spp. ranged from 70.60 to 298.03 ng/ml with EVs, and from 30.45 to 326.97 ng/ml in the absence of rumen fluke EVs.

Figure 3 Bacterial qPCR analysis following in vitro culture of rumen fluid incubated with C. daubneyi SEC purified EVs (p) and without EVs (n). Data shown for (A) Total bacteria, (B) Fibrobacter succinogenes, (C) Ruminococcus albus and (D) Prevotella spp. *indicates a significant difference between treatment means.

In terms of overall treatment, EV presence or absence, a significant effect of treatment with C. daubneyi EVs was only observed for total bacteria (P = 0.002). Whereby, the incubation of rumen fluid with EVs led to an increase in total bacterial concentration, with no significant overall effect of treatment on bacterial concentrations for F. succinogenes, R. albus, or Prevotella spp. Analysis of overall treatment between time points (0-24 hrs) showed significant interaction for total bacteria (P=0.008), R. albus (P<0.05), and Prevotella spp. (P<0.05). However, there was no significant interaction between timepoint and treatment for F. succinogenes (P>0.05). For total bacteria concentrations, there was a significant difference between treatment means at the zero hours and six-hour timepoints. For F. succinogenes, the only timepoint at which there was a significant difference between treatment means was at zero hours (P=0.001). There was a significant difference in the mean concentration of R. albus DNA between treatments at all except the four-hour timepoint. Prevotella spp. had a significant difference between treatment means at the two and six hour timepoints (P >0.01).

Utilization of the recently reported adult C. daubneyi transcriptome (Huson et al., 2018) has allowed a comprehensive proteomic characterization of the adult helminth’s membrane bound vesicle secretions, leading to identification of 378 proteins consistent across biological replicates. Comparison with resolved eukaryote EV proteomes highlighted a number of common proteins including, tetraspanins (TR20913|c0_g1_i1, TR22166|c0_g1_i1, TR22094|c0_g1_i1 and TR22869|c0_g1_i12), Heat shock proteins (TR17741|c0_g1_i1 and TR20530|c0_g1_i1) and Annexins (TR22803|c1_g1_i2, TR20643|c0_g1_i1 and TR17648|c0_g1_i1). This is in addition to EV associated cytoskeletal proteins such as Actin (TR9358|c0_g1_i1, TR17779|c0_g1_i1 and TR28482|c0_g1_i1) and Ezrin (TR19715|c0_g1_i1) as well as proteins involved in metabolic processes such as enolase (TR17367|c0_g1_i1, TR24268|c0_g1_i1, TR24268|c0_g2_i1 and TR19628|c0_g2_i1), Peroxidases (TR17193|c0_g1_i1 and TR12513|c0_g1_i1) and pyruvate kinases (TR21788|c0_g1_i1) (Choi et al., 2013; Nowacki et al., 2015). The consistency in proteins with established EV proteomes further supports the identification of the membrane bound vesicles by TEM imaging as EVs, suggesting the C. daubneyi secretome is more complex than previously demonstrated (Huson et al., 2018).

Protein cargo packaged into EVs prior to their release is dependent upon cellular source and release cell associated activity (Simons and Raposo, 2009). Similar to the closely related trematode F. hepatica and in contrast to several trematode species such as E. caproni, S. mansoni and D. dendriticum, rumen fluke EVs returned a large quantity of proteases and peptidases including Xaa-pro peptidase, cathepsins and metalloproteases (Marcilla et al., 2012; Bernal et al., 2014; Sotillo et al., 2016). Differences observed in protein cargo packaged between species could be due to their residency within the definitive host but could also be attributed to conditions during time of release (Nowacki et al., 2015). Hits to hypothetical proteins and proteins with ‘no confirmed identity’ highlighted the variability in proteins packaged and their likely roles in parasite establishment that are likely unique to the rumen fluke. In total, 14.2% of the proteins identified represented these undefined proteins and their further investigation could allow insight into infection, migration and successful establishment of infection (Dalton et al., 2003). Consistent to studies in F. hepatica a plethora of molecules including fatty-acid binding proteins, sigma-class glutathione transferases and cathepsin B were identified which are known to be internalized by host cells with their immunomodulation activity leading to a TH2-mediated environment that is favorable for parasite establishment (Dalton et al., 2003; Donnelly et al., 2010; Dowling et al., 2010). As with previous trematode studies, the presence of uncharacterized proteins allows the hypothesis that they could contain a plethora of novel sequences with potential roles in parasite pathogenesis. Investigation of uncharacterized proteins with no homology to resolved sequences provides an assortment of possible research avenues into future control and intervention of infection (Mulvenna et al., 2010).

Proteins present upon the surface of parasite derived EVs have been found critical to EV function as they interact directly with cells mediating cellular uptake and affecting immune recognition whilst also allowing identification, isolation and classification of EV subpopulations (Buzás et al., 2018). Trypsin hydrolysis of the surface of C. daubneyi EVs identified a total of 86 proteins including a variety of well-known exosomal markers such as heat shock protein 70 and members of the tetraspanin family as defined by the Exocarta database (http://www.exocarta.com). As expected, a trematode specific tetraspanin (CD63) was identified within the proteome, as common EV markers, members of the tetraspanin family have been widely investigated with studies on O. viverrini highlighting the potential use of EV derived tetraspanins as vaccine candidates due to their ability to prevent EV uptake and internalization into host cells (Chaiyadet et al., 2015). As with studies into closely related trematode F. hepatica EVs, many of the surface proteins resolved represented metabolic enzymes such as enolase, Glyceraldehyde-3-dehydrogenase and annexins with primary roles as adhesion molecules interacting directly with the surface of host cells and so represent possible targets in preventing C. daubneyi successful establishment through interruption of EVs internalization by target cells (Bernal et al., 2004; Lama et al., 2009; de la Torre-Escudero et al., 2012).

Following resolution of both the cargo and membrane bound proteome, the potential of C. daubneyi EVs to modulate the microbiome were investigated on a range of ruminant bacterial species. Both helminths and bacterial species residing within the gut have been found to have strong immunomodulatory effects on the mammalian host, with a variety of studies showing helminths effect on the microbiota correlating to the helminths successful establishment (Reynolds et al., 2015). Helminths ability to regulate gut microbiota is important due to the ability of certain species to elicit the host immune response favorable for survival (Reynolds et al., 2015), with several previous helminth studies highlighting their ability to regulate bacterial populations within the gut (Su et al., 2018). Here, the effect of EVs on bacterial species encompassed three bacterial species found within the rumen as well as the total bacterial counts within the rumen microbiome. F. succinogenes, R. albus, and Prevotella spp. were chosen for quantification using qPCR to investigate the effect of EVs on the rumen microbiome and any subsequent effects on metabolism. Of these three species, F. succinogenes and R. albus are considered to be the main cellulolytic bacteria in the rumen (Forsberg et al., 1997), with these species extensively studied using a combination of pure culture and molecular techniques (Minato and Suto, 1978; Mosoni et al., 1997; Koike et al., 2003; Shinkai and Kobayashi, 2007; Zeng et al., 2015). The third species utilized, Prevotella spp. represent non-cellulolytic bacteria that play a vital role in ruminal protein degradation (Wallace, 1996; Alauzet et al., 2010).

Exposure of C. daubneyi EVs to ruminant bacterial populations showed no significant effect between EV treatment and controls, suggesting there is no significant effect of C. daubneyi EVs on rumen microbial facilitated metabolism, or in particular fiber and protein digestion. As expected, given the absence of a feed source, a drop in bacterial DNA concentrations at the 24-hour time point was common across all samples, as feed associated bacteria comprise 70-80% of the ruminal microbial matter (McAllister et al., 1994). The only timepoint found to have a significant difference between treatment means for F. succinogenes was timepoint zero. This could be due to the use of rumen fluid inoculum which is deemed as the largest source of variation in in vitro rumen studies, due to variations that can occur due to its microbial activity, the preparation method, the concentration of the rumen fluid used, the donor animal from which it is derived and their diet, and even variances within the day have been reported (Cone et al., 1996; Jessop and Herrero, 1998; Rymer et al., 1999; Mould, 2003; Váradyová et al., 2005). For R. albus the only timepoint at which there was no significant difference between treatments was the 4-hour timepoint. Whilst, not large enough to be significant the inclusion of EVs appears to slow the decrease in the concentration of R. albus over time. A similar effect of EV inclusion was observed for Prevotella spp. although again this was not significant.

However, a significant difference was observed for total bacteria DNA concentrations between EV treatment and controls. An increase observed in total bacteria populations alongside no significant differences between treatment and controls for F. Succinogenes, R. albus, and Prevotella spp. may indicate that addition of EVs leads to an increase in total bacterial diversity. This increase in diversity could be due to rumen fluke EVs promoting the survival of several bacterial species in the rumen with previous whole parasite studies reporting increases in certain bacterial species in response to infection. Walk et al. (2010) and Reynolds et al. (2015) observed an increase in members of the lactobacillaceae family in the ileum of mice infected with H. polygyrus, despite the mice having different microbiotas present at the outset of the experiment. Similarly, the administration of a single dose of Trichuris suis led to a reduction in the abundance of Fibrobacter and Ruminococcus, accompanied by an increase of campylobacter in gastrointestinal microbiota of pigs (Wu et al., 2012). Alternatively, rumen fluke EVs could be promoting an increase in overall ruminal bacterial diversity as has been observed in gastrointestinal helminth infections in humans (Sepehri et al., 2007; Monira et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2014). Due to the absence of significant differences between treatments and the observed change in total bacteria concentrations the effects of C. daubneyi EVs on further ruminal bacterial species would allow a more in-depth understanding of C. daubneyi regulation of the microbiota.

Currently, studies into the effects of parasitic helminths on the gut microbiota of their ruminant hosts remain inconsistent, with investigations showing conflicting results (Li et al., 2011; Li et al., 2016). It is thought these inconsistencies are due to the composition and abundance of gut microbial taxa associated with the parasitic helminths being specific to each species (Kreisinger et al., 2015). A higher species richness may benefit the host, as higher species richness of the gut microbiota has been associated with ‘healthier’ gut homeostasis (Sepehri et al., 2007; Monira et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Kreisinger et al., 2015). However, this study was designed to simulate a high, close proximity infection of adult rumen fluke, and so the changes in the microbiome seen here may be indicative of a more local effect on the microbiome. It is likely the effects observed may not be seen across the whole rumen. Additionally, EVs derived from rumen fluke may have a greater effect on the bacterial species of the rumen associated with the epithelium and liquid phases, as rumen fluke affix themselves to the rumen epithelium via their posterior sucker (McCowan et al., 1978; Michalet-Doreau et al., 2001; Fuertes et al., 2015). EVs ability to regulate the hosts gut microbiota highlights the potential of utilizing EVs in order to promote survival of key bacterial species such as F. succinogenes that play a vital role in degradation of plant biomass and so could lead to improved rumen efficiency (Arntzen et al., 2017). A full antimicrobial analysis of all EV proteins characterized would be beneficial as EVs are known to bind to targets in order to become internalized and release their contents and so these may also be influencing the EVs themselves as well as elucidating mechanisms through which EVs released by C. daubneyi manipulate the host microbiota leading to conditions favorable for long term establishment.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD024182.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Aberystwyth University ethics committee.

NA: data collection, analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing—original draft. AL: experimental design, data collection, and analysis. TW: experimental design and formal analysis. SH: experimental design and technical expertise. HP: technical expertise—LC-MSMS. RM and PB—supervision, writing, review, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council through an IBERS PhD Scholarship award and through Innovate UK (Grant Number: 102108).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank Prof. Andrew Devitt (Aston University, England) and Dr. Ivana Milic (Aston University, England) for the use of qNano particulate analyzer (IZON science), and Randall Parker foods (Llanidloes, Wales) for allowing collection of C. daubneyi from infected cattle.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2021.661830/full#supplementary-material

Alauzet, C., Marchandin, H., Lozniewski, A. (2010). New insights into Prevotella diversity and medical microbiology. Future Microbiol. 5 (11), 1695–1718. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.126

Arntzen, M. Ø., Várnai, A., Mackie, R. I., Eijsink, V. G. H., Pope, P. B. (2017). Outer membrane vesicles from Fibrobacter succinogenes S85 contain an array of carbohydrate-active enzymes with versatile polysaccharide-degrading capacity. Environ. Microbiol. 19 (7), 2701–2714. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13770

Bernal, D., de la Rubia, J. E., Carrasco-Abad, A. M., Toledo, R., Mas-Coma, S., Marcilla, A. (2004). Identification of enolase as a plasminogen-binding protein in excretory-secretory products of Fasciola hepatica. FEBS Lett. 563 (1-3), 203–206. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00306-0

Bernal, D., Trelis, M., Montaner, S., Cantalapiedra, F., Galiano, A., Hackenberg, M., et al. (2014). Surface analysis of Dicrocoelium dendriticum. The molecular characterization of exosomes reveals the presence of miRNAs. J. Proteomics 105 (13), 232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.02.012

Broadhurst, M. J., Ardeshir, A., Kanwar, B., Mirpuri, J., Gundra, U. M., Leung, J. M., et al. (2012). Therapeutic helminth infection of macaques with idiopathic chronic diarrhea alters the inflammatory signature and mucosal microbiota of the colon. PloS Pathogens 8 (11), e1003000. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003000

Buck, A. H., Coakley, G., Simbari, F., McSorley, H. J., Quintana, J. F., Le Bihan, T., et al. (2014). Exosomes secreted by nematode parasites transfer small RNAs to mammalian cells and modulate innate immunity. Nat. Commun. 5 (1), 5488. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6488

Buzás, E. I., Tóth, E. Á., Sódar, B. W., Szabó-Taylor, K. É. (2018). Molecular interactions at the surface of extracellular vesicles. Semin. Immunopathol. 40 (5), 453–464. doi: 10.1007/s00281-018-0682-0

Cantacessi, C., Giacomin, P., Croese, J., Zakrzewski, M., Sotillo, J., McCann, L., et al. (2014). Impact of experimental hookworm infection on the human gut microbiota. J. Infect. Diseases 210 (9), 1431–1434. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu256

Chaiyadet, S., Sotillo, J., Smout, M., Cantacessi, C., Jones, M. K., Johnson, M. S., et al. (2015). Carcinogenic Liver Fluke Secretes Extracellular Vesicles That Promote Cholangiocytes to Adopt a Tumorigenic Phenotype. J. Infect. Diseases 212 (10), 1636–1645. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv291

Chaucheyras-Durand, F., Ossa, F. (2014). Review: The rumen microbiome: Composition, abundance, diversity, and new investigative tools. Prof. Anim. Scientist 30 (1), 1–12. doi: 10.15232/S1080-7446(15)30076-0

Choi, C. S., Kim, D. K., Kim, Y. K., Gho, Y. S. (2013). Proteomics, Transcriptomics and Lipidomics of exosomes and ectosomes. Proteomics 13 (10–11), 1554–1571. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200329

Coakley, G., Buck, A. H., Maizels, R. M. (2016). Host parasite communications-Messages from helminths for the immune system: Parasite communication and cell-cell interactions. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 208 (1), 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2016.06.003

Cone, J. W., Van Gelder, A. H., Visscher, G. J. W., Oudshoorn, L. (1996). Influence of rumen fluid and substrate concentration on fermentation kinetics measured with a fully automated time related gas production apparatus. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 61 (1–4), 113–128. doi: 10.1016/0377-8401(96)00950-9

Cwiklinski, K., Torre-Escudero, E., Trelis, M., Bernal, D., Dufresne, P. J., Brennan, G. P., et al. (2015). The Extracellular Vesicles of the Helminth Pathogen, Fasciola hepatica: Biogenesis Pathways and Cargo Molecules Involved in Parasite Pathogenesis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14 (12), 3258–3273. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.053934

Dalton, J. P., Brindley, P. J., Knox, D. P., Brady, C. P., Hotez, P. J., Donnelly, S., et al. (2003). Helminth vaccines: from mining genomic information for vaccine targets to systems used for protein expression. Int. J. Parasitol. 33 (5–6), 621–640. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00057-2

Davis, C. N., Phillips, H., Tomes, J. J., Swain, M. T., Wilkinson, T. J., Brophy, P. M., et al. (2019). The importance of extracellular vesicle purification for downstream analysis: A comparison of differential centrifugation and size exclusion chromatography for helminth pathogens. PloS Neglect. Trop. Diseases 13 (2), e0007191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007191

de la Torre-Escudero, E., Manzano-Román, R., Siles-Lucas, M., Pérez-Sánchez, R., Moyano, J. C., Barrera, I., et al. (2012). Molecular and functional characterization of a Schistosoma bovisannexin: fibrinolytic and anticoagulant activity. Vet. Parasitol. 184 (1), 25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.08.013

Donnelly, S., O’Neill, S. M., Stack, C. M., Robinson, M. W., Turnbull, L., Whitchurch, C., et al. (2010). Helminth cysteine proteases inhibit TRIF-dependent activation of macrophages via degradation of TLR3. J. Biol. Chem. 285 (5), 3383–3392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060368

Dowling, D. J., Hamilton, C. M., Donnelly, S., La Course, J., Brophy, P. M., Dalton, J., et al. (2010). Major secretory antigens of the helminth Fasciola hepatica active a suppressive dendritic cell phenotype that attenuates Th17 cells but fails to activate Th2 immune responses. Infect. Immunity 78 (2), 793–801. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00573-09

Forsberg, C. W., Cheng, K. J., White, B. A. (1997). “Polysaccharide degradation in the rumen and large intestine,” in Gastrointestinal Microbiology. Eds. Mackie, R. I., White, B. A. (New York: Chapman and Hall), 319–379.

Fuertes, M., Pérez, V., Benavides, J., González-Lanza, M. C., Mezo, M., González-Warleta, M., et al. (2015). Pathological changes in cattle naturally infected by Calicophoron daubneyi adult flukes. Vet. Parasitol. 209 (3-4), 188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.02.034

Gensollen, T., Iyer, S. S., Kasper, D. L., Blumberg, R. S. (2016). How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 352 (6285), 539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9378

Goering, H. K., Van Soest, P. J. (1970). Forage fiber analysisUSDA Agric. Handbook No. 379 (Washington, DC: USDA-ARS).

Huson, K. M., Oliver, N. A. M., Robinson, M. W. (2017). Paramphistomosis of Ruminants: An Emerging Parasitic Disease in Europe. Trends Parasitol. 33 (11), 836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.07.002

Huson, K. M., Morphew, R. M., Allen, N. R., Hegarty, M. J., Worgan, H. J., Girdwood, S. E., et al. (2018). Polyomic tools for an emerging livestock parasite, the rumen fluke Calicophoron daubneyi; identifying shifts in rumen functionality. Parasites Vectors 11 (1), 617. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3225-6

Huws, S. A., Lee, M. R., Muetzel, S. M., Scott, M. B., Wallace, R. J., Scollan, N. D. (2010). Forage type and fish oil cause shifts in rumen bacterial diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 73 (2), 396–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00892.x

Jenkins, T. P., Formenti, F., Castro, C., Piubelli, C., Perandin, F., Buofrate, D., et al. (2018). A comprehensive analysis of the faecal microbiome and metabolome of Strongyloides stercoralis infected volunteers from non-endemic area. Nat. Sci. Rep. 8, 15651. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33937-3

Jessop, N. S., Herrero, M. (1998). “Modelling fermentation in an in vitro gas production system: effects of microbial activity,” in In Vitro Techniques for Measuring Nutrient Supply to Ruminants, vol. 22. (Cambridge University Press: BSAS occasional publication), 81–84. doi: 10.1017/S0263967X00032304

Jones, R., Brophy, P., Mitchell, E., Williams, H. (2017). Rumen fluke (Calicophoron daubneyi) on Welsh farms: Prevalence, risk factors and observations on co-infection with Fasciola hepatica. Parasitology 144 (2), 237–247. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016001797

Koike, S., Pan, J., Kobayashi, Y., Tanaka, K. (2003). Kinetics of in sacco fiber-attachment of representative ruminal cellulolytic bacteria monitored by competitive PCR. J. Dairy Sci. 86 (4), 1429–1435. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73726-6

Kreisinger, J., Bastien, G., Hauffe, H. C., Marchesi, J., Perkins, S. E. (2015). Interactions between multiple helminths and the gut microbiota in wild rodents. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 370 (1675), 20140295. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0295

LaCourse, E. J., Perally, S., Morphew, R. M., Moxon, J. V., Prescott, M., Dowling, D. J., et al. (2012). The Sigma class glutathione transferase from the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica. PloS Neglect. Trop. Diseases 5 (6), e1666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001666

Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227 (5259), 680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0

Lama, A., Kucknoor, A., Mundodi, V., Alderete, J. F. (2009). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is a surface-associated, fibronectin-binding protein of Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect. Immunity 77 (7), 2703–2711. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00157-09

Lee, S. C., San Tang, M., Lim, Y. A., Choy, S. H., Kurtz, Z. D., Cox, L. M., et al. (2014). Helminth colonization is associated with increased diversity of the gut microbiota. PloS Neglect. Trop. Diseases 8 (5), e2880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002880

Li, R. W., Wu, S., Li, W., Huang, Y., Gasbarre, L. C. (2011). Metagenome plasticity of the bovine abomasal microbiota in immune animals in response to Ostertagia ostertagi infection. PloS One 6 (9), e24417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024417

Li, R. W., Wu, S., Li, W., Navarro, K., Couch, R. D., Hill, D., et al. (2012). Alterations in the porcine colon microbiota induced by the gastrointestinal nematode Trichuris suis. Infect. Immunity 80 (6), 2150–2157. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00141-12

Li, R. W., Li, W., Sun, J., Yu, P., Baldwin, R. L., Urban, J. F. (2016). The effect of helminth infection on the microbial composition and structure of the caprine abomasal microbiome. Sci. Rep. 6, 20606. doi: 10.1038/srep20606

Lin, A., Bik, E. M., Costello, E. K., Dethlefsen, L., Haque, R., Relman, D. A., et al. (2013). Distinct distal gut microbiome diversity and composition in healthy children from Bangladesh and the United States. PloS One 8 (1), e53838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053838

Maizles, R. M., McSorley, H. J. (2016). Regulation of the host immune system by helminth parasites. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138 (3), 666–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.007

Marcilla, A., Trelis, M., Cortes, A., Sotillo, J., Cantalapiedra, F., Minguez, M. T., et al. (2012). Extracellular Vesicles from Parasitic Helminths Contain Specific Excretory/Secretory Proteins and Are Internalized in Intestinal Host Cells. PloS One 7 (9), e45974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045974

Mason, C., Stevenson, H., Cox, A., Dick, I. (2012). Disease associated with immature paramphistome infection in sheep. Vet. Rec. 170 (13), 343–344. doi: 10.1136/vr.e2368

McAllister, T. A., Bae, H. D., Jones, G. A., Cheng, K. J. (1994). Microbial attachment and feed digestion in the rumen. J. Anim. Sci. 72 (11), 3004–3018. doi: 10.2527/1994.72113004x

McCowan, R. P., Cheng, K. J., Bailey, C. B., Costerton, J. W. (1978). Adhesion of bacteria to epithelial cell surfaces within the reticulo-rumen of cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 35 (1), 149–155. doi: 10.1128/AEM.35.1.149-155.1978

Michalet-Doreau, B., Fernandez, I., Peyron, C., Millet, L., Fonty, G. (2001). Fibrolytic activities and cellulolytic bacterial community structure in the solid and liquid phases of rumen contents. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 41 (2), 187–194. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2001122

Millar, M., Colloff, A., Scholes, S., Bovine, H. (2012). Disease associated with immature paramphistome infection. Vet. Rec. 171 (20), 509–511. doi: 10.1136/vr.e7738

Minato, H., Suto, T. (1978). Technique for fractionation of bacteria in rumen microbial ecosystem. II. Attachment of bacteria isolated from bovine rumen to cellulose powder in vitro and elution of bacteria attached therefrom. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 24 (1), 1–16. doi: 10.2323/jgam.24.1

Monira, S., Shabnam, S. A., Alam, N. H., Endtz, H. P., Cravioto, A., Alam, M. (2012). 16S rRNA gene- targeted TTGE in determining diversity of gut microbiota during acute diarrhoea and convalescence. J. Health Population Nutr. 30 (3), 250. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i3.12287

Montaner, S., Galiano, A., Trelis, M., Martin-Jaular, L., del Portillo, H. A., Bernal, D., et al. (2014). The role of extracellular vesicles in modulating the host immune response during parasitic infections. Front. Immunol. 5, 433. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00433

Mosoni, P., Fonty, G., Gouet, P. (1997). Competition between ruminal cellulolytic bacteria for adhesion to cellulose. Curr. Microbiol. 35 (1), 44–47. doi: 10.1007/s002849900209

Mould, F. L. (2003). Predicting feed quality—chemical analysis and in vitro evaluation. Field Crops Res. 84 (1–2), 31–44. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4290(03)00139-4

Mulvenna, J., Sripa, B., Brindley, P. J., Gorman, J., Jones, M. K., Colgrave, M. L., et al. (2010). The secreted and surface proteomes of the adult stage of the carcinogenic human liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini. Proteomics 10 (5), 1063–1078. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900393

Nowacki, F. C., Swain, M. T., Klychnikov, O. I., Niazi, U., Ivens, A., Quintana, J. F., et al. (2015). Protein and small non-coding RNA-enriched extracellular vesicles are released by the pathogenic blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. J. Extracell. Vesicles 5 (4), 28665. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.28665

Peachey, L. E., Castro, C., Molena, R. A., Jenkins, T. P., Griffin, J. L., Cantacessi, C. (2019). Dysbiosis associated with acute helminth infections in herbivorous youngstock – observations and implications. Nat. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 11121. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47204-6

Petri, R. M., Schwaiger, T., Penner, G. B., Beauchemin, K. A., Forster, R. J., McKinnon, J. J., et al. (2013). Characterization of the core rumen microbiome in cattle during transition from forage to concentrate as well as during and after an acidotic challenge. PloS One 8 (12), e83424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083424

Reynolds, L. A., Smith, K. A., Filbey, K. J., Harcus, Y., Hewitson, J. P., Redpath, S. A., et al. (2015). Commensal-pathogen interactions in the intestinal tract: lactobacilli promote infection with, and are promoted by, helminth parasites. Gut Microbes 5 (4), 522–532. doi: 10.4161/gmic.32155

Rymer, C., Huntington, J. A., Givens, D. I. (1999). Effects of inoculum preparation method and concentration, method of inoculation and pre-soaking the substrate on the gas production profile of high temperature dried grass. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 78 (3–4), 199–213. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(99)00006-1

Sanabria, R. E. F., Romero, J. R. (2008). Review and update of paramphistomosis. Helminthologia 45 (2), 64–68. doi: 10.2478/s11687-008-0012-5

Sepehri, S., Kotlowski, R., Bernstein, C. N., Krause, D. O. (2007). Microbial diversity of inflamed and noninflamed gut biopsy tissues in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Diseases 13 (6), 675–683. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20101

Shinkai, T., Kobayashi, Y. (2007). Localization of ruminal cellulolytic bacteria on plant fibrous materials as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization and real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 (5), 1646–1652. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01896-06

Simons, M., Raposo, G. (2009). Exosomes – vesicular carriers for intercellular communication. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21 (4), 575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.007

Sotillo, J., Pearson, M., Potriquet, J., Becker, L., Pickering, D., Mulvenna, J., et al. (2016). Extracellular vesicles secreted by Schistosoma mansoni contain protein vaccine candidates. Int. J. Parasitol. 46 (1), 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.09.002

Su, C., Su, L., Li, Y., Chang, J., Zhang, W., Walker, W. A., et al. (2018). Helminth-Induced Alterations Of The Gut Microbiota Exacerbate Bacterial Colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 11 (1), 144–157. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.20

Váradyová, Z., Baran, M., Zeleňák, I. (2005). Comparison of two in vitro fermentation gas production methods using both rumen fluid and faecal inoculum from sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 123 (1), 81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2005.04.030

Walk, S. T., Blum, A. M., Ewing, S. A. S., Weinstock, J. V., Young, V. B. (2010). Alteration of the murine gut microbiota during infection with the parasitic helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Inflamm. Bowel Diseases 16 (11), 1841–1849. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21299

Wallace, R. J. (1996). Ruminal microbial metabolism of peptides and amino acids. J. Nutr. 126 (4S), 1326S–1334S. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.suppl_4.1326S

Wu, S., Li, R. W., Li, W., Beshah, E., Dawson, H. D., Urban, J. F., Jr (2012). Worm burden-dependent disruption of the porcine colon microbiota by Trichuris suis infection. PloS One 4 (7), e35470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035470

Zaiss, M. M., Harris, N. L. (2016). Interactions between the intestinal microbiome and helminth parasites. Parasite Immunol. 38 (1), 5–11. doi: 10.1111/pim.12274

Zeng, Y., Zeng, D., Zhang, Y., Ni, X., Tang, Y., Zhu, H., et al. (2015). Characterization of the cellulolytic bacteria communities along the gastrointestinal tract of Chinese Mongolian sheep by using PCR-DGGE and real-time PCR analysis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31 (7), 1103–1113. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1860-z

Keywords: Calicophoron daubneyi, extracellular vesicle, proteomics, rumen microbiome, mass spectrometry

Citation: Allen NR, Taylor-Mew AR, Wilkinson TJ, Huws S, Phillips H, Morphew RM and Brophy PM (2021) Modulation of Rumen Microbes Through Extracellular Vesicle Released by the Rumen Fluke Calicophoron daubneyi. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11:661830. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.661830

Received: 31 January 2021; Accepted: 17 March 2021;

Published: 20 April 2021.

Edited by:

Luiz Gustavo Gardinassi, Universidade Federal de Goiás, BrazilReviewed by:

Liliana M. R. Silva, University of Giessen, GermanyCopyright © 2021 Allen, Taylor-Mew, Wilkinson, Huws, Phillips, Morphew and Brophy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Russell M. Morphew, cm9tQGFiZXIuYWMudWs=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.