- 1Laboratory of Tropical Diseases, Department of Genetics, Evolution, Microbiology and Immunology, University of Campinas - UNICAMP, Campinas, Brazil

- 2Laboratory of Regulation of Gene Expression, Instituto Carlos Chagas, Curitiba, Brazil

- 3Department of Chemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

During the last decade, the vast omics field has revolutionized biological research, especially the genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics branches, as technological tools become available to the field researcher and allow difficult question-driven studies to be addressed. Parasitology has greatly benefited from next generation sequencing (NGS) projects, which have resulted in a broadened comprehension of basic parasite molecular biology, ecology and epidemiology. Malariology is one example where application of this technology has greatly contributed to a better understanding of Plasmodium spp. biology and host-parasite interactions. Among the several parasite species that cause human malaria, the neglected Plasmodium vivax presents great research challenges, as in vitro culturing is not yet feasible and functional assays are heavily limited. Therefore, there are gaps in our P. vivax biology knowledge that affect decisions for control policies aiming to eradicate vivax malaria in the near future. In this review, we provide a snapshot of key discoveries already achieved in P. vivax sequencing projects, focusing on developments, hurdles, and limitations currently faced by the research community, as well as perspectives on future vivax malaria research.

Introduction

The last 10 years brought breakthroughs in biological research with the emergence of and improved accessibility to sequencing technology (Margulies et al., 2005). Nowadays, the increasingly available, user-friendly and less costly next generation sequencing (NGS) (Metzker, 2010) platforms are major technological contributions. Genomic exploration of organisms in greater detail through whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a reality. Additional valuable insights are coming from whole transcriptome (WTS) and proteome sequencing projects within the wider “omics” field, which start to shed light on multiple aspects of biology. Data integration within the “omics,” quantitative, functional and regulatory analysis - systems biology - is revolutionizing our understanding of the mechanisms of life. All these interconnected genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic platforms bring a new world of possibilities for hypothesis-driven research.

Genome sequencing projects revealed Plasmodium spp. genetic diversity and contributed to a better knowledge of parasite biology and host-parasite interaction (Hemingway et al., 2016). A significant number of fully sequenced and high quality Plasmodium spp. reference genomes are available (Carlton et al., 2008a; Dharia et al., 2010; Menard et al., 2010, 2013; Westenberger et al., 2010; Bright et al., 2012; Chan et al., 2012; Neafsey et al., 2012; Flannery et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016), and sequence curation efforts should continue. Today, the malaria research community ventures more and more into transcriptomics (Bozdech et al., 2008; Hoo et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016) and proteomics (Ray et al., 2016, 2017), areas to capitalize on for understanding Plasmodium spp. biology, especially the dynamics of RNA and protein expression and regulation through its complex multi-staged life cycle, in host and vector interaction contexts, and under different environmental selective pressures. Hence, the expertise provided by in-depth sequencing projects with clear data integration for understanding metabolic pathways in a systematic way is welcome by the parasite research community. Not only does it provide important pieces of information to understand different immune evasion and host invasion strategies, it is also a way to monitor and find new means to combat the rapidly increasing transmission of drug resistant parasites, and to identify molecular targets as starting points for effective vaccine development.

Plasmodium vivax malaria research has historically faced numerous technical adversities and has been largely neglected. This situation has led to a general lack of knowledge of P. vivax biology, and consequently impaired our capacity for making the best decisions on transmission control measures, and in the long run, for vivax malaria eradication. Currently vivax malaria is acknowledged as a disease that should no longer be neglected as it has been shown to result in considerable morbidity and mortality (Alexandre et al., 2010; Andrade et al., 2010; Lacerda et al., 2012a; Quispe et al., 2014; Rodriguez-Morales et al., 2015; Siqueira et al., 2015).

In this review, we show the main achievements on P. vivax biology accomplished based on the published genome, transcriptome and proteome sequencing projects. In particular, (1) the genome-wide comparative studies showing evolutionary relationships between parasites of the same genus, (2) the broad genetic diversity landscape within the P. vivax populations reported as to understand specific selection pressures (environmental and host/vector related) acting presently on parasite populations, (3) the more recent expression profile datasets and regulation mechanisms emerging from sensitive high-throughput WTS (RNA-seq) of P. vivax in different stages, and (4) the attempts to identify parasite metabolic pathways and antigens as possible diagnosis biomarkers through mass spectrometry (MS) based proteomics analysis of parasites and human host profiling from vivax malaria patient samples. Also, we present the main challenges encountered, remaining gaps and possible research avenues being explored and developed by the vivax malaria community.

Vivax Malaria: An Overview

Human malaria infections can be caused by five different Plasmodium species. P. falciparum is considered the deadliest parasite, causing the most severe clinical outcomes, whereas P. vivax is the most geographically spread within densely populated regions, thus accentuating the socio-economic burden caused by the disease (Gething et al., 2012; WHO, 2015). Recently, vivax malaria has re-emerged in regions formerly considered malaria free (Severini et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2009; Bitoh et al., 2011). Worldwide, about 2.85 billion people have been estimated to be at risk of infection by P. vivax (Price et al., 2007; Guerra et al., 2010; Battle et al., 2012; Gething et al., 2012). Following the decline of P. falciparum infections, P. vivax is now the dominant malaria species in several endemic regions (Coura et al., 2006; Gething et al., 2012; Hussain et al., 2013; WHO, 2015), where reports show a higher incidence, especially in young children (Marsh et al., 1995; Williams et al., 1997; Price et al., 2007; Genton et al., 2008; Tjitra et al., 2008). Several clinical complications that were normally associated with P. falciparum infections have been reported for vivax malaria (Kochar et al., 2005, 2009a; Hutchinson and Lindsay, 2006; Baird, 2007; Barcus et al., 2007; Alexandre et al., 2010; Rahimi et al., 2014). The most observed include anemia (Haldar and Mohandas, 2009; Quintero et al., 2011), haemolytic, coagulation disorders, jaundice (Sharma et al., 1993; Erhart et al., 2004; Lacerda et al., 2004; Saharan et al., 2009) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (Anstey et al., 2002, 2007; Suratt and Parsons, 2006; Tan et al., 2008; Lacerda et al., 2012b; Lanca et al., 2012), followed by nephropathology (Chung et al., 2008), porphyria (Kochar et al., 2009b), rhabdomyolysis (Siqueira et al., 2010), splenic rupture (de Lacerda et al., 2007; Gupta, 2010), and cerebral malaria (Lampah et al., 2011; Tanwar et al., 2011). Vivax malaria during pregnancy causing spontaneous abortions, premature and low weight new-borns (McGready et al., 2004; Poespoprodjo et al., 2008) is another major health concern, challenging the pre-established view of P. vivax as a “benign” parasite (Mendis et al., 2001; Baird, 2007; Anstey et al., 2009; Mueller et al., 2009; Gething et al., 2012; Naing et al., 2014).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines (WHO, 2015), the first line P. vivax chemotherapy is chloroquine (CQ) plus primaquine (PQ), the only approved drug targeting the latent parasite form (Beutler et al., 2007). In high transmission areas presenting cases of drug resistance, an artemisinin based combination therapy (ACT) is recommended (WHO, 2010). The constant increase and spread of anti-malarial drug resistance remains of great concern (Baird, 2004; de Santana Filho et al., 2007; Suwanarusk et al., 2007; Poespoprodjo et al., 2008; Russell et al., 2008; Tjitra et al., 2008; Price et al., 2009, 2014).

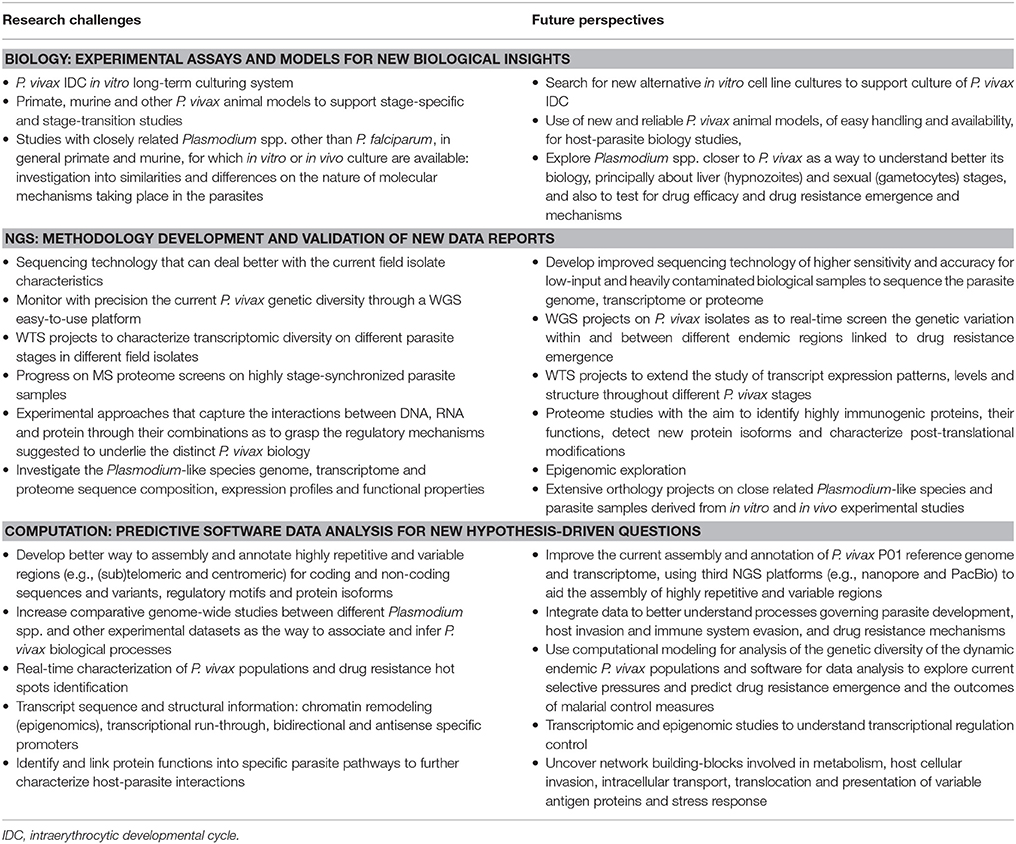

P. vivax had an evolutionary path distinct from P. falciparum, being more closely related to P. cynomolgi, a sister taxon that infects Asian macaque monkeys (Duval et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2015). Probably as a consequence of such a unique evolutionary path, P. vivax shows unique biological features (Baird, 2007; Mueller et al., 2009; Gething et al., 2012) that distinguish it from P. falciparum (Figure 1):

(1) Preference for invading reticulocytes (RTs) (Field and Shute, 1956), increasing their deformability, size, fragility and permeability (Kitchen, 1938; Suwanarusk et al., 2004; Handayani et al., 2009; Desai, 2014), which would allow P. vivax to evade the host immune system (del Portillo et al., 2004; Suwanarusk et al., 2004; Handayani et al., 2009) and maintain its characteristic low biomass parasitemia (Mueller et al., 2009).

(2) Earlier production of sexual stages during the infection (Boyd and Kitchen, 1937), with a characteristic spherical shape seen in peripheral blood circulation even before the beginning of clinical symptoms, which might function as a reservoir to promote successful transmission to the mosquitoes (Boyd and Kitchen, 1937; Bousema and Drakeley, 2011).

(3) Formation of hypnozoites, which remain in the liver in a latent state (Krotoski et al., 1982; Baird et al., 2007), and for which the reactivation mechanisms are still unknown (Mueller et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum life cycle comparison. (A) Anopheles blood meal infection: Malaria infection occurs once a female Anopheles spp. mosquito inoculates Plasmodium sporozoites into the skin of the human host during its feeding (Kiszewski et al., 2004). The sporozoites eventually reach the bloodstream. (B) Pre-erythrocytic stage infection: The sporozoites are transported through the vascular system to the liver, where they migrate across Kupffer or endothelial cells and enter hepatocytes. When a hepatocyte is found and within a period of 10–12 days, sporozoites from both Plasmodium species form a parasitophorous vacuole membrane and differentiate into schizonts. The schizogony process involves thousands of mitotic replications giving rise to a high number of merozoites packed into merosomes, which are then released into the bloodstream. P. vivax sporozoites can also differentiate into dormant long lasting liver forms called hypnozoites that upon activation start schizogony with consequent release of merozoites into the vasculature, and consequently causing clinical relapses (Krotoski, 1985). (C) Asexual erythrocytic stage: During this 48 h stage, P. vivax merozoites have a preference for reticulocyte invasion, whereas P. falciparum invade normocytes. Upon invasion, the parasite promotes several alterations in these blood cells, enlarging and deforming them (Suwanarusk et al., 2004) and promoting the formation of caveola-vesicle like complexes (CVC) and cytoplasmic cleft structures (Barnwell et al., 1990), resulting in an appropriate environment for asexual schizogony in the bloodstream. The species-specific set of surface proteins produced by the parasites influences the proportion of different parasite stages observed in the patient's peripheral blood and are suggested to be linked to the different pyrogenic capacity, biomass and parasitemia levels presented by vivax or falciparum malaria patients. RBC, Red Blood Cell. (D) Intra-erythrocytic gametocyte development: A proportion of asexual parasites are known to undergo gametocytogenesis into round-shaped sexual micro- and macrogametocytes, quite early (4 days) after P. vivax infection compared to P. falciparum (15 days post-infection) (Pelle et al., 2015), before detection of any clinical symptoms. (E) Mosquito Stage: Gametocytes circulating in the bloodstream can be taken up by the next Anopheles blood meal and engage in the sexual cycle with release of male and female mature gametes, fertilization (zygote) and formation of motile ookinetes that cross the mosquito midgut epithelium and further mature into oocysts. The oocyst, a new asexual sporogonic replicative entity, generates and releases thousands of sporozoites. These sporozoites migrate and invade the salivary glands of the mosquito vector and can then be transmitted to a new human host, completing the complex life cycle of the parasite (Mueller et al., 2009).

P. vivax research has been greatly restricted by lack of a reliable and reproducible in vitro system for long term culture (culturing efforts reviewed by Udomsangpetch et al., 2008; Noulin et al., 2013). This limitations are reflected both in the quantity and quality of functional assays performed in ex vivo short term cultures (Noulin et al., 2013). Furthermore, the alternative use of monkey-based studies with adapted strains of P. vivax (Beeson and Crabb, 2007; Panichakul et al., 2007) is of no easy access. Nevertheless, the available molecular tools (reviewed in Escalante et al., 2015) emerge as a valuable option to better estimate the prevalence and incidence of vivax malaria, its dynamics and differential contributions between host and vectors.

Plasmodium Vivax Genomics

Genome Sequencing Breakthroughs and Projects

In 2008, Carlton and colleagues achieved the complete generation, assembly and analysis of the first P. vivax WGS (Carlton, 2003; Feng et al., 2003; Carlton et al., 2008a), 6 years after the publication of P. falciparum reference genome (Gardner et al., 2002; Figure 2). The sequenced P. vivax Salvador-1 (Sal-1) strain came from a patient isolate from La Paz, close to El Salvador, and was passed to human volunteers, Aotus owl monkeys, and subsequently adapted to growth in Saimiri squirrel monkeys by mosquito and blood infection during the 1970s (Collins et al., 1972). Only later, it was possible to extract enough genomic DNA (gDNA) for whole genome shotgun sequencing (WGSS) and de novo assembly (Carlton et al., 2008a). Some technical hurdles were overcome, notably that the genome GC content of the parasite and laboratory host were similar and little information was available for the squirrel monkey gDNA sequence to exclude possible contamination (Carlton, 2003).

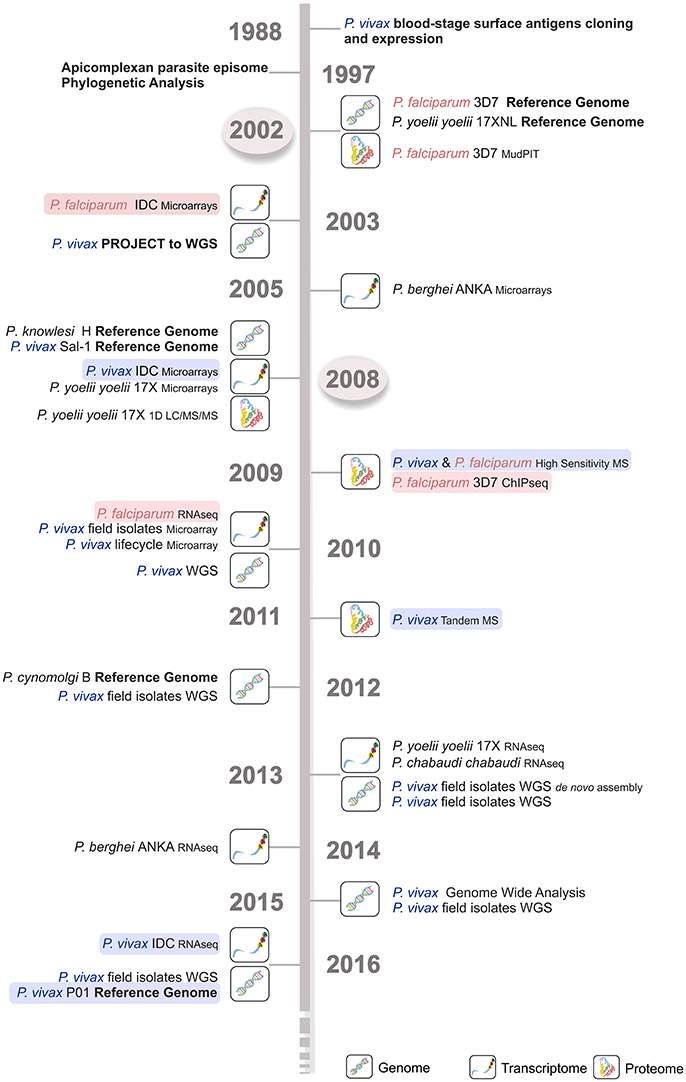

Figure 2. Time line of the major Plasmodium spp. sequencing projects. Genome, transcriptome, and proteome sequencing projects in the last four decades have contributed to our current parasite biology knowledge. P. falciparum (light red) and P. vivax (light blue) sequencing projects are shown, emphasizing the delay in time of around 5–6 years for the latter species. The first P. falciparum reference genome became available much earlier in 2002 (circled in light gray), then the corresponding P. vivax Sal-1 reference genome in 2008 (circled in light gray). WGS, whole genome sequencing; IDC, intraerythrocytic developmental cycle; MudPIT, multidimensional protein identification technology; MS, mass spectrometry; 1D LC-MS/MS, one-dimension liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; ChIP-seq, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) DNA sequencing.

The constraints initially faced by these studies to acquire sufficient gDNA of acceptable quality for WGS were alleviated by the use of NGS platforms. These allowed direct sequencing of the first patient ex vivo isolate in 2010 (Dharia et al., 2010) without the need for in vitro propagation (Figure 2) or use the of more traditional and laborious cloning and expression approaches (del Portillo et al., 1988). Since then, sequencing technology sensitivity has increased while required genetic material amounts have decreased, leading to lower costs. As a result, NGS is now a portable benchtop technology much closer to endemic areas. Parasite DNA can be enriched in low parasitemia blood samples and human contamination eliminated (Auburn et al., 2013). To achieve an effective preparation of P. vivax field isolates for WGS, a technique combining a CF11-based human lymphocyte filtration and the short-term ex vivo culture for schizont maturation was optimized and is currently applied with success in several labs set in endemic areas. An alternative approach to preventing host contamination and enriching samples in P. vivax DNA is the direct sequencing of parasite gDNA by hybrid selection (Melnikov et al., 2011). This sequencing methodology has allowed the first worldwide characterization of P. vivax isolates (Dharia et al., 2010; Menard et al., 2013).

Recently, several patient isolates from Peru, Madagascar, Malagasy, Cambodia, and a Belem monkey adapted strain were sequenced coupled with the resequencing of the Sal-1 strain (Carlton et al., 2008a) using whole genome capture (WGC), WGS and NGS techniques (Dharia et al., 2010; Bright et al., 2012; Chan et al., 2012; Neafsey et al., 2012; Winter et al., 2015; Figure 2). In 2016, major WGS analysis studies were published, including one sequencing 195 P. vivax genomes including 182 new high depth and quality sequences from clinical isolates from 11 different countries worldwide (Hupalo et al., 2016) and 13 already published sequences from both clinical isolates and monkey-adapted laboratory lines. In addition, 70 Cambodian P. vivax isolates, further compared to 80 P. falciparum isolates from the same region (Parobek et al., 2016) were sequenced, considerably augmenting the genomic data available to the malaria community (Luo et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Parobek et al., 2016; Figure 2). Expectations are that these data will bring great advances in population genetics at a genome scale and that comparative genomic analysis (CGA) will function as a powerful method for parasite evolution hypothesis generation and testing (Feng et al., 2003).

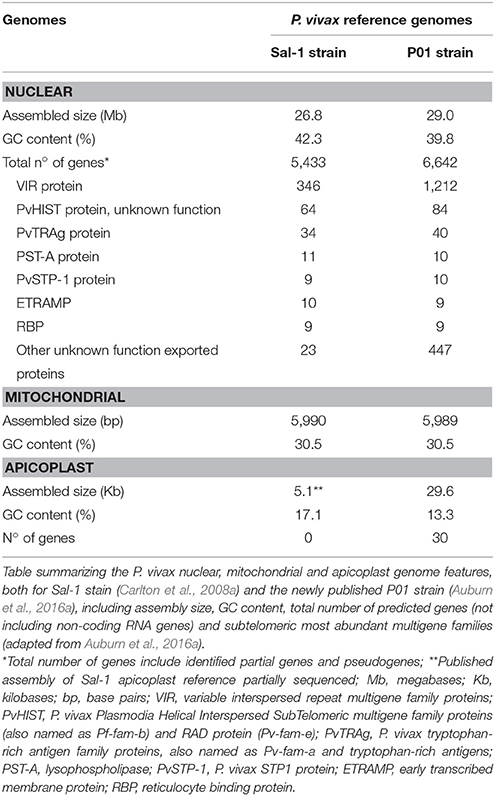

Recently, a newly assembled and annotated reference genome named P. vivax P01 was published (Auburn et al., 2016a; Figure 2). The data was generated by using high-depth Illumina® sequencing from a Papua Indonesia patient isolate (Auburn et al., 2016a). For assembly, manual curation and comparison between data sets, the draft assemblies for the P. vivax isolates C01 (China) and T01 (Thailand) were used (Auburn et al., 2016a). The higher degree of assembly of these three genomes (~11 times) largely exceeds the Sal-1 reference genome (Carlton et al., 2008b; Auburn et al., 2016a). Not only was there an enhancement on scaffolds assembly with reduction from 2,500 unassembled scaffolds in Sal-1 to 226 in P01 reference genomes, as an improvement of the subtelomeric regions scaffold assembly. Therefore, annotation was also improved with the attribution of functions to 58% against the 38% in Sal-1 in a total of 4,465 core genes, defined as genes 1:1 orthologous between P. vivax P01 and P. falciparum 3D7 strains (Auburn et al., 2016a; Figure 3 and Table 1). The improvements in assembly and annotation quality in this sequencing project contributed to the generation of this very important new resource to study vivax malaria.

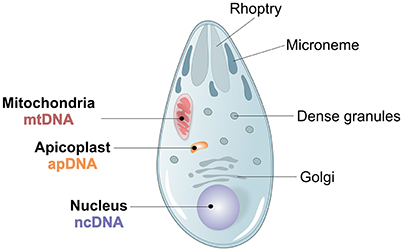

Figure 3. Plasmodium spp. morphology and genome architecture. Illustration showing the principal characteristics of Apicomplexan Plasmodium spp. parasite morphology, with its 3 parasite genomes, nuclear (ncDNA), mitochondrial (mtDNA) and apicoplast (apDNA).

Genome Architecture and Evolution

The biggest landmark achieved with the WGS of Plasmodium spp. was data acquisition to perform alignments and construct synteny maps with improved annotation, i.e., identifying conserved order of genetic loci along chromosomes (Ureta-Vidal et al., 2003). Through CGA one can now understand how the key forces that shape the evolutionary processes of organisms (mutation, selection, and genetic drift) came into play, by assuming that the genomes analyzed share a common ancestor (Frazer et al., 2003). For instance, CGA has allowed us to understand the integration of the apicoplast into apicomplexan species (Kohler et al., 1997) and to identify genes and their target signals transferred from the second endosymbiotic event into Plasmodium (Foth et al., 2003). Furthermore, CGA based on the P. falciparum and P. yoelii yoelii WGSs was the first such comparison between tropical pathogens of the same genus (Carlton et al., 2002; Feng et al., 2003), suggesting that chromosomal reshuffling might have been involved in speciation inside the Plasmodium genus.

Three different genomes, one nuclear, one mitochondrial and one apicoplast, characterize P. vivax (Figure 3). The ~26.8 megabases (Mb) nuclear genome is distributed among 14 chromosomes and has 42.3% GC average content, although presenting an isochore structure with high GC content in most internal chromosome regions, interspersed by high AT stretches mainly in subtelomeric regions (Carlton, 2003; Carlton et al., 2008a; Taylor et al., 2013; Table 1). The significance of Plasmodium spp. isochore structure remains unknown (Eyre-Walker and Hurst, 2001), however GC-rich genes evolve faster than AT-rich subtelomeric genes (Carlton, 2003; Carlton et al., 2008a). The codon usage in P. vivax is balanced (Nc~54.2), with less biased use of the 61 codons (Carlton et al., 2008b; Yadav and Swati, 2012; Cornejo et al., 2015). In particular, gene location in telomeric, centromeric or chromosome interstitial regions was recently shown to present different codon biased compositions (Cornejo et al., 2015). Genes showing the highest codon usage bias encode housekeeping proteins, the most highly expressed. Interestingly, genes in this category also include the Pf/Pv-fam family putatively responsible for antigenic variation and associated with early gametocyte formation (Cornejo et al., 2015). These patterns have led to speculation regarding the strong influence of the mutation rate on local nucleotide (nt) composition. This may indicate dramatic variance in gene expression potential and profiles, and that genes encoded in such regions could intervene in the specific pathophysiology of P. vivax malaria (McCutchan et al., 1984; Carlton et al., 2008b; Cornejo et al., 2015). As previously observed for other organisms, P. vivax DNA enriched in CpG motifs stimulates the Toll-like Receptor 9 (TLR9) increasing the host inflammatory response (Parroche et al., 2007), previously thought to be mainly caused by hemozoin toxicity alone. Given that P. vivax has a higher GC content, a greater TLR9 activation upon parasite DNA uptake by the host has been hypothesized (Anstey et al., 2009), potentially contributing to the increased pyrogenicity of this parasite (Karunaweera et al., 1992; Hemmer et al., 2006).

With reservations for sequence misassembly, it was estimated that the P. vivax parasite has around 5,400 genes (Carlton et al., 2008a; Table 1), of which a large majority was found to be orthologous between several Plasmodium spp. (CGA on human parasites P. vivax and P. falciparum, primate parasites P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi and the rodent parasites P. yoelii. yoelii, P. chabaudi, and P. berghei; Carlton et al., 2008a). Orthologous genes identified had conserved genome positions with no genome breakage hot spots (Carlton et al., 2008a). Specifically, the more closely related primate species P. cynomolgi and P. knowlesi (Glazko and Nei, 2003) showed a higher degree of conservation throughout the 14 chromosomes (Cornejo et al., 2015) with exception for multigenic regions, where frequent microsyntenic breaks were identified (Carlton et al., 2008b). Calculation of substitution rates at synonymous (dS) vs. non-synonymous (dN) sites has allowed estimation of the relative importance of selection and genetic drift (dN/dS) throughout P. vivax evolution. Although a great difference between average dS and dN values was observed in ~3,300 high-confidence P. vivax/P. knowlesi orthologous gene pairs, these values correlate within and between syntenic regions of chromosomes of the two species. Carlton and colleagues have suggested heterogeneous mutation rates across the genome (Carlton, 2003). In Plasmodium, genes encoding membrane-anchored, transmembrane, cell adhesion, exported proteins or extracellular proteins with signal peptide motifs, most of them in direct contact with the host defense system, evolve relatively faster than the ones encoding housekeeping proteins (Carlton et al., 2008a). Selective constraint analysis between the highly conserved P. vivax/P. cynomolgi genomes reported a minority of genes (<2%) as positively selected and consequently evolving quicker than others with heavily constrained functions (Carlton et al., 2008a). Therefore, it appears that evolutionary rates have been greatly influenced by host-parasite interactions leading to a high degree of variation between different gene classes in Plasmodium (Carlton et al., 2008a; Joy et al., 2008).

It has been suggested that P. vivax had an African origin (Koepfli et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2015) and subsequently spread through the world (Culleton et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2014). The recently analyzed P. vivax samples were gathered in two main groups, Old and New World (Hupalo et al., 2016). Today the diversity between Old World P. vivax and P. falciparum samples is significantly higher. This is indicative of a large effective population size in P. vivax that shows signs of population specific natural selection, where P. vivax is constantly adapting to human host and mosquito vector regional differences, and more recently, to antimalarial drug pressures (Neafsey et al., 2012; Winter et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Parobek et al., 2016). These results were also seen at the local level for a high number of P. vivax samples from the Asian-Pacific region (Brazeau et al., 2016; Parobek et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016) and, in a smaller scale, in South American samples (Winter et al., 2015). The non-uniform distribution of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in P. vivax, clearly enriched at subtelomeric regions, is being interpreted as a result of local high recombination rates. This leads to the hypothesis that selection not only acts on genes, but also has been shaping the P. vivax genomic architecture. Natural selection can thus act faster on these regions where the generation of antigenic variation occurs and also have a direct influence on genome architecture and consequently, impact P. vivax adaptation (Cornejo et al., 2015). Further, genome-wide analysis of P. vivax genetic diversity points at interesting evolutionary implications. For instance, the P. vivax genome is generally under very strong constraint with negative selection, and only very few genes are being positively selected (Cornejo et al., 2015; Parobek et al., 2016). Such results suggest a longer evolutionary history of primate infection (Liu et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2015), clearly closer to other monkey-infecting Plasmodium spp. (Carlton et al., 2013) than to P. falciparum, making it more adapted to survive and replicate in primate hosts.

These results have supported the use of monkey malaria Plasmodium spp. as models for the adaptation of P. vivax parasite populations (Chan et al., 2015), Moreover, amplification in monkey hosts of patient isolates from several endemic areas (Brazil, North Korea, India, and Mauritania) (Galinski and Barnwell, 2012) was crucial to collect enough high-quality gDNA for WGS (Neafsey et al., 2012; Carlton et al., 2013). However, analysis of these sequences should take into account that the parasites isolated from vivax malaria patients were passed through multiple infection cycles and were adapted to grow in Saimiri boliviensis monkeys (Carlton et al., 2008b). Host switching and adaptation to a new in vivo immune environment could affect mutation rates, and consequently the degree of P. vivax sequence variation, expression profiles and multiclonal complexity of parasite populations (Hester et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the study of Chan and colleagues proved that research using P. vivax monkey-adapted strains resulted in useful data, however data interpretation should be done with caution, given that these strains are not always genetically homogeneous (Chan et al., 2015). Overall, WGS reveals specific differences within human malaria Plasmodium spp. which should be taken into account in future interventions (Carlton et al., 2008a; Pain et al., 2008; Frech and Chen, 2011; Tachibana et al., 2012; Hester et al., 2013; Cornejo et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Parobek et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016).

Plasmodium Vivax Transcriptomics

Whole Transcriptome Sequencing Projects

The first great effort into this parasite's transcriptome profile immediately followed the publication of P. vivax Sal-1 reference genome (Figure 2). By using a customized microarray platform of their own design, Bozdech et al. directly accessed P. vivax mRNA levels throughout 48 h intraerythrocytic developmental cycle (IDC) of three distinct isolates (Bozdech et al., 2008). Expression data analysis identified stage-specific differential expression of certain groups of genes. These genes were predicted to encode proteins with a role in parasitic development, virulence capacity and/or host-parasite interaction. In the following years, several microarray platform studies were published (Bozdech et al., 2008; Westenberger et al., 2010; Boopathi et al., 2013, 2014; Figure 2). Supporting the previous findings of Bozdech et al. on transcript levels at different lifecycle stages, Westenberger and colleagues described dramatic changes in messenger RNA (mRNA) co-expression of various genes predicted to be involved in developmental processes, suggesting that they could modulate parasitic progress through its different stages (Westenberger et al., 2010). In the 5′ region of co-expressed genes conserved motifs across Plasmodium spp. were identified as possible sites for regulatory protein binding with important roles in stage specific transcriptional regulation. Several multigene families and genes predicted to encode exported proteins displayed synchronized transcription in P. vivax sporozoites, but no difference (different gene set or mRNA levels) was observed between parasites showing capacity for hepatocyte invasion or hypnozoite development (Westenberger et al., 2010). Boopathi et al. reported a positive correlation of Natural Antisense Transcripts (NATs) with sense transcripts level, indicating that differing sense/antisense transcript ratios are involved in differential regulation of gene expression in diverse clinical conditions (Bozdech et al., 2008; Westenberger et al., 2010; Boopathi et al., 2013, 2014).

Very recently, RNA-seq was successfully applied to re-sequence two P. vivax isolates (Bozdech et al., 2008) throughout their IDC (Zhu et al., 2016; Figure 2). RNA-seq is more sensitive than gene expression microarrays as it detects expression nuances. In addition, RNA-seq includes all transcripts and not only the ones previously characterized present on microarray slides. The IDC transcriptome map produced by the high-resolution Illumina® HiSeq platform allows a better comprehension of the regulation behind the parasite gene expression profiles for specific biological functions. Strand-specific RNA-seq was just published for three isolates from Cambodian vivax malaria patient before anti-malarial treatment, and transcripts were assembled de novo revealing homogenous parasite gene expression profile regardless of the proportion of different stages (Kim et al., 2017). These results contrast with the gene expression pattern reported before (Bozdech et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2016) and with data for sporozoites isolated from salivary glands of infected Colombian mosquitos (Kim et al., 2017). The authors recognize the fact that the patient isolates have multi-staged parasites, where one asexual stage might be transcriptionally more active than the others and, irrespective of its proportion, will deliver most transcripts, homogenizing the final expression patterns observed (Kim et al., 2017).

Differential Expression and Regulation

Plasmodium parasites do not have the typical eukaryotic transcriptional apparatus, presenting a poor repertoire of transcription associated proteins (TAP) somewhat similar among P. falciparum, P. vivax, and P. knowlesi, but with a significant range of putative regulatory sequences in the genome. This raises the idea of a dynamic, complex and non-standard gene expression regulation system (Carlton et al., 2008a; Boopathi et al., 2013, 2014; Adjalley et al., 2016). From the microarray and RNA-seq studies, some of the P. vivax transcriptome architecture characteristics have emerged. Throughout IDC of P. vivax (and other Plasmodium spp.), the overall timing of gene expression profiles does not differ significantly between strains and isolates. Hence, transcriptional differences or variations observed between species might reflect distinct evolution paths (Bozdech et al., 2008). Species-specific gene expression patterns in members of multigene families may mirror separate environmental challenges and multiple and varied host-parasite interactions faced by the parasites (Bozdech et al., 2008; Westenberger et al., 2010; Boopathi et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2016). Considerable changes were found on orthologous genes (30% divergence) between P. falciparum (Bozdech et al., 2003; Le Roch et al., 2003) and P. vivax (Bozdech et al., 2008; Westenberger et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2016). Expression of these genes peaks at different moments and possibly contributes to a specific timing reflecting species-specific biological functions. Among these genes are those related to host-parasite interactions, red blood cells (RBC) invasion, early intraerythrocytic development and antigenic variation. P. vivax antigen-presenting gene families (e.g., vir and trag genes) are activated mainly at the schizont-ring stage transition, indicative of different transcriptional control between the two species and, once more, underscoring the marked biological distinctions between the two most important human malaria parasites (Bozdech et al., 2003, 2008). In addition, contrary to what was seen for P. falciparum (Bozdech et al., 2003), P. vivax seems to have an enhanced capacity to adapt to its host and modify its virulence factors, as shown by its extensive intra-isolate gene expression diversity (Bozdech et al., 2008). RNA-seq data analysis revealed a transcriptional hotspot of vir genes on chromosome 2, suggesting them as important for immune evasion mechanisms. Structurally, P. vivax genes present unusually long 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) and multiple transcription start sites (TSSs) (Zhu et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2017). Supporting previous observations, Hoo et al. published the first integrated transcriptome analysis for six Plasmodium spp. showing that conserved syntenic orthologs present early parasitic stage transcriptional divergence, where expression patterns follow the corresponding mammalian hosts (Hoo et al., 2016) and changes in important putative transcriptional regulators might explain the observed transcriptional diversity. Conversely, orthologs presenting similar transcriptional profiles across all Plasmodium spp. might be responsible for conserved and crucial functions (Hoo et al., 2016).

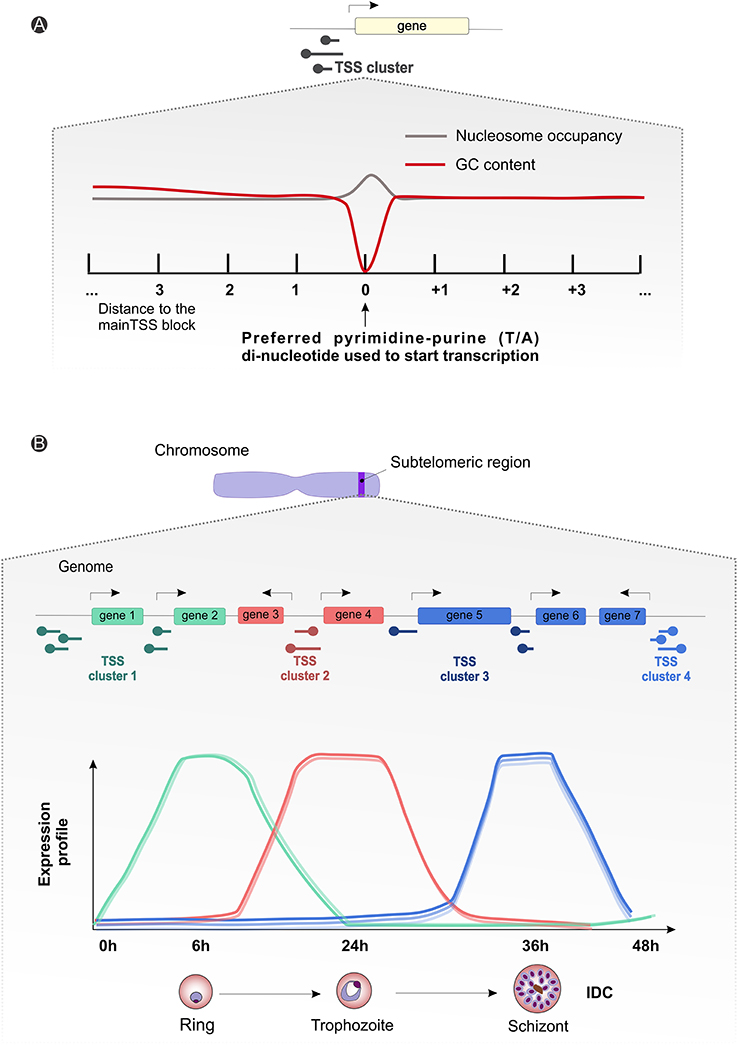

The importance of clusters of TSSs, the significance of long 5′ vs. shorter 3′ UTRs, alternative splicing events and the profusion of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), in a context of genome-wide different GC content, is starting to be characterized (Zhu et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2017). Different sequence motifs have already been associated with stage specific expression regulation (Westenberger et al., 2010), and recently Zhu and colleagues observed a substantial variation of the 5′ UTR owing to differential selection of TSS, although these phenomena do not seem to be involved in regulation of the asexual parasite cycle. P. falciparum transcriptome analyses reveal uniform usage of several clusters of TTSs, but in a differentiated way (Figure 4A; Watanabe et al., 2002; Lenhard et al., 2012; Adjalley et al., 2016). Such sites are spaced along the genome, indicative of dispersed patterns of transcription both in coding and intergenic regions (Watanabe et al., 2002; Lenhard et al., 2012; Adjalley et al., 2016). With a broad bidirectional promoter sequence possibly controlled by multiple regulatory elements, also characteristic of other eukaryotic species, the architecture and sequence properties of Plasmodium spp. chromosomes can play an important role in transcription initiation and regulation by means of chromatin remodeling (Watanabe et al., 2002; Lenhard et al., 2012; Adjalley et al., 2016). Moreover, as for P. falciparum, P. vivax shows a cycling transcription pattern throughout the IDC (Bozdech et al., 2003; Le Roch et al., 2003), with stage-specific regulation of transcription initiation events, well correlated with gene expression levels (Figure 4B; Siegel et al., 2014; Adjalley et al., 2016).

Figure 4. Plasmodium spp. gene expression and regulation dynamics. (A) Scheme illustrating the average observed nucleotide content and nucleosome occupancy surrounding the transcriptional start site blocks (black round tip arrow) controlling gene expression, with a preferential pyrimidine-purine (T/A) di-nucleotide usage (gray line) and a drop-in guanine-cytosine (GC) content (red line) around the starting site. (B) Generic representation showing an amplification of the suggested subtelomeric (blue strip on the chromosome drawing) transcriptional start site clusters (round tip arrows) dynamics for differential gene expression during parasitic intraerythrocytic developmental cycle (~48 h). The graph displays arbitrary subtelomeric gene expression profiles under different TSS clusters control, during ring (green, peak at 6 h), trophozoite (red, peak at 24 h) and schizont (blue, peak at 36 h) stages. IDC, intraerythrocytic developmental cycle; TSS, transcriptional start site.

Alternative splicing as a mechanism of producing transcriptome variability was reported for P. falciparum with a role in parasite sexual development (Iriko et al., 2009; Otto et al., 2010; Sorber et al., 2011), contrasting with the scarcity reported until now for P. vivax (Zhu et al., 2016). However, the few splicing events identified are linked to a late schizont stage, suggesting its significance at the gene function level (Zhu et al., 2016). Recently, Kim and colleagues described a high percentage of P. vivax genes encoding multiple, often uncharacterized, protein-coding sequences (Kim et al., 2017). In addition to long 5′ UTRs, many of the isoforms significantly differ in their 5′- or 3′-UTRs, possibly as a result of differential exon splicing. P. vivax may use such protein isoforms in transcription and/or translation regulation mechanisms. Importantly, examples of such cases support the idea that even for well-described genes conferring drug resistance, novel isoforms can be revealed through transcriptomic data analysis, which could aid in decoding molecular mechanisms responsible for antimalarial drug resistance (Hoo et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2017).

All P. vivax transcriptomic data allowing for ncRNAs identification reveal the presence of these RNAs at high levels, notably in the antisense direction (Zhu et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2017). In 2013, the NATs identified in P. vivax directly isolated from infected patients with different malaria complications by genome-wide transcriptome analysis using customized high density tiling microarray sequencing technology (Boopathi et al., 2014), suggested a possible role in differential regulation of P. vivax gene expression. The involvement of distinct types of transcriptional machinery and different mechanisms, such as transcriptional run-through, bidirectional and antisense-specific promoters, produces a varied landscape of differential regulation observed for P. vivax from malaria patients in diverse clinical conditions (Boopathi et al., 2013). Surprisingly, the extensively investigated micro RNAs (miRNAs) class of ncRNAs appears to be absent in some Apicomplexan species including Plasmodium. However, an increasing number of studies have described a role of host miRNAs in host-parasite interactions (reviewed by Judice et al., 2016), as host miRNA expression can change after parasite infection and, within this context, suggesting a crucial role for the host immune system signaling.

The incorporation of RNA sequencing data will be extremely important to further work on annotated genes and continue the curation and further characterization of putative genes sets that are being identified in new P. vivax isolates under WGS projects. On the other hand, transcript data will indicate the significance of SNPs and increase of copy number variation (CNV) during the hypothesized recent population expansion in P. vivax (Mu et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2013; Cornejo et al., 2015; Parobek et al., 2016). Furthermore, genome-wide transcriptome analysis already contributes to a better understanding of the dynamics of P. vivax gene expression by annotating new coding and non-coding transcripts, determining absolute levels of some transcripts, and characterizing the biological importance of UTRs, TSSs and alternative splicing sites (Zhu et al., 2016). Most importantly, it gives an understanding of the role of the transcriptional regulatory machinery and fine-tuned mechanisms that promote the large and diverse population upkeep of P. vivax, ability to stand up to selective sweeps, including those pressures caused by malaria control measures (Parobek et al., 2016). Even though only few studies into P. vivax transcriptional regulation have been published (Bozdech et al., 2008; Hoo et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016), some results suggest that specific biological processes that have enabled the parasite to avoid the traditional malaria control measures might be under tight transcriptional control. For example, early gametogenesis (Bousema and Drakeley, 2011) along with the asexual cycle seems to be achieved by transcriptional repression of an AP2 transcription factor (Yuda et al., 2015; Hoo et al., 2016). Another example is the biological process underlying hypnozoite latent stage formation and activation, suggested to be under epigenetic regulation. Studies using simian hepatocyte cultures report an acceleration of hypnozoite activation when histone methylation is inhibited. Thus, methylation of histones promotes suppression of transcription, and ultimately, maintain hypnozoite dormancy (Barnwell and Galinski, 2014; Dembele et al., 2014). Other example of P. vivax transcriptional regulation are related to mechanisms of drug resistance emergence, has shown for differential expression of CRT protein, rather than pvcrt gene coding sequence alteration, mediating CQ resistance (Fernandez-Becerra et al., 2009; Melo et al., 2014; Pava et al., 2015).

Plasmodium Vivax Proteomics and Metabolomics

Parasite and Patient Serum Proteome Analysis

In spite of all advances mentioned above, the functions of half of the predicted proteins in P. vivax remain unknown. Unsurprisingly, P. vivax and P. falciparum share a similar metabolic potential with key housekeeping pathways and functions and a range of putative membrane transporters, including the important apicoplast metabolism, essential for the parasite (Carlton et al., 2008a). The apicoplast proteome plays an important role in several major parasite metabolic processes, including some described for P. falciparum (Ralph et al., 2004) including isopentenyl diphosphate and iron sulfur cluster assembly, type II fatty acid synthesis and haem synthesis pathways, the latter subdivided between the apicoplast and mitochondria. The localization of several other central pathways is being clarified. For example, it was confirmed that the glyoxalase pathway occurs in the apicoplast, although in P. vivax, thiamine pyrophosphate biosynthesis takes place in the cytosol (Baird, 2010).

Although P. falciparum studies gave us some indications on the principal features of the P. vivax proteome, parasite-specific biology probably involves expression of different gene families. Thus, alternative invasion and host escape pathways still remain largely unknown. Stage-specific analysis of P. vivax IDC from natural isolates is extremely challenging due to low parasitemias, characteristically asynchronous parasite populations, and frequent polyclonal infections. In order to overcome the low parasitemia data challenge, some studies have pooled samples from different patients. However, such procedures can potentially increase the assortment of proteins detected, render their identification and association with disease pathogenesis more difficult, and affect the reproducibility of vivax proteomic data and follow up validation studies. Proteome studies are expected to contribute greatly by disclosing proteins expressed in clinical isolates and reveal new unique parasite pathways involved in malaria pathophysiology, leading to identification of new targets for drug and vaccine development.

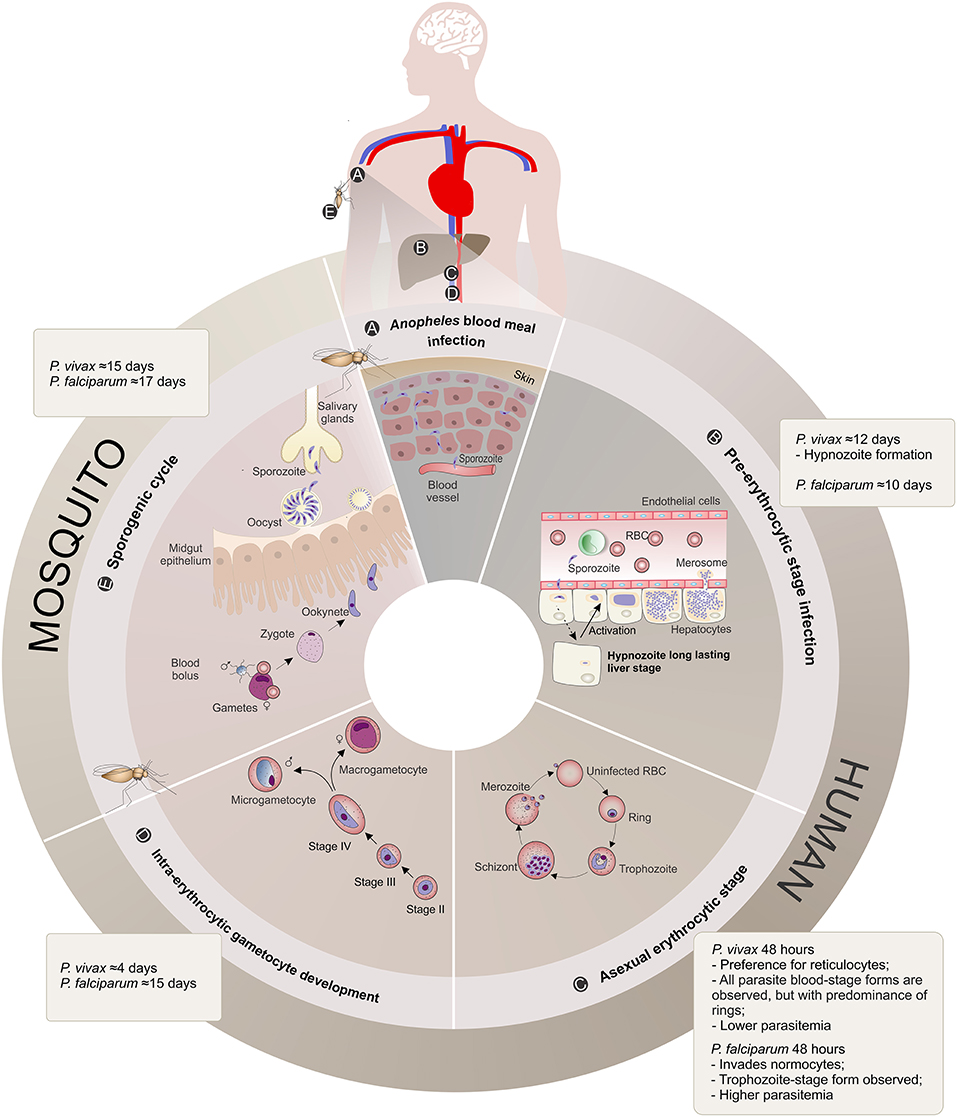

Efforts are being made to identify potential vivax malaria biomarkers to understand host responses. The earliest proteome study, published in 2009 (Acharya et al., 2009), identified 16 proteins from a single patient infected with P. vivax blood-stage parasites (Figure 2). In 2011, the same authors were the first to examine the P. vivax proteome directly from a pool of clinical isolates, identifying a total of 153 P. vivax proteins, most of them with unknown homology to expressed genes (Acharya et al., 2011). That same year Roobsoong et al. (2011) published the P. vivax schizont proteome from multi-patient schizont cultures and enriched samples, where they reported 316 proteins of which 36 were unique to this parasite, and half of these were unique hypothetical proteins. Such proteins could be P. vivax-specific targets for diagnosis and treatment, as the four novel P. vivax antigens described (Roobsoong et al., 2011). More recently, 238 trophozoite proteins were identified in P. vivax strain VCG-1 together with 485 from the Aotus host (Moreno-Perez et al., 2014). The in-depth analysis of two P. vivax Sal-1 proteomes (S. boliviensis monkey iRBCs at the trophozoite stage) allowed the identification of 1375 parasite and 3209 host proteins and their post-translational modifications, mostly N-terminal acetylation (Anderson et al., 2015).

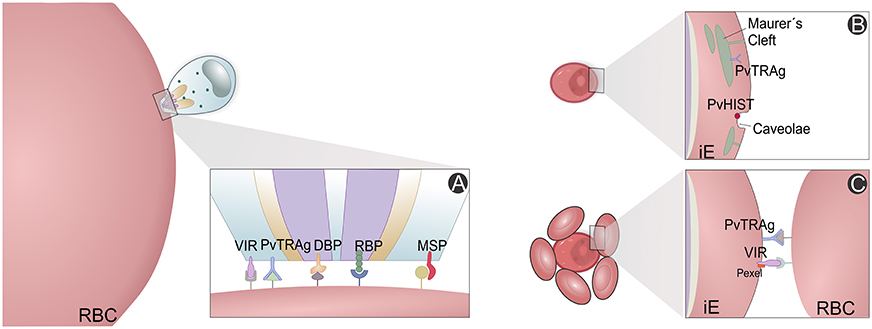

High-throughput screening has been used to study P. vivax immune proteomes, leading to identification of 44 antigens from a total of 152 protein putative candidates, and characterization and confirmation of rhoptry-associated membrane antigens (PvRAMA) as relevant serological markers of recent exposure to infections (Lu et al., 2014). Furthermore, differences between P. vivax and P. falciparum antigenic genes were revealed. Most of these highly immunoreactive proteins are hypothetical, but there have been suggestions of their importance for P. vivax invasion and evasion mechanisms (Figure 5). For instance, reticulocyte binding protein 2 and RAMA maybe involved in selectivity for invasion of RTs and/or exported protein 1 and 2, histidine-rich knob protein homolog and aspartic protease PM5 for host immune evasion (Lu et al., 2014).

Figure 5. P. vivax variant proteins. Slices of the P. vivax infected erythrocyte (Pv-iE) are shown with known variant proteins (VIR, PvTRAg, DBP, RBP, PvHIST, MSP) involved in P. vivax merozoite invasion (A), transport structures mediating the export of parasite ligands on the surface that promote changes in the host erythrocyte (B) and proteins associated with host evasion mechanisms, e.g., the rosetting phenotype (C). RBC, red blood cell; iE, infected erythrocyte; VIR, variable interspersed repeat multigene family proteins; PvTRAg, P. vivax tryptophan-rich antigen family proteins; PvHIST, P. vivax Plasmodia Helical Interspersed SubTelomeric multigene family proteins; DBP, Duffy binding protein; RBP, reticulocyte binding proteins; MSP, Merozoite surface proteins; Pexel, Plasmodium export element protein motif.

Humoral immunity of vivax malaria patients has also been interrogated. Chen and co-authors cloned and expressed 89 proteins that were screened against sera from vivax malaria patients using protein arrays to show 18 highly immunogenic of which 7 had been already characterized as vaccine candidates and the remaining were uncharacterized (Chen et al., 2010). Later, Ray and colleagues (Ray et al., 2012a,b) identified proteins such as apolipoprotein A1 and E, serum amyloid A and P, haptoglobin, ceruloplasmin, and hemopexin as differentially expressed in uncomplicated malaria patients by serum proteome analysis. Collectively, these results indicate that several physiologically important host pathways have been modulated during parasitic infection including vitamin D metabolism, hemostasis and the coagulation cascade, acute phase response and interleukin signaling, and the complement pathway (Ray et al., 2012a).

Host-Parasite Metabolic Pathways

To uncover pathway modulation occurring during uncomplicated (Ray et al., 2012a,b) vs. severe vivax malaria (Ray et al., 2016), researchers are going further into clinicopathological analysis and proteomic profiling. Recently, human serum proteome comparative studies were published (Ray et al., 2016) showing different levels of parasitemia for severe and non-severe infections, as well as during the acute and convalescent phases of the infection (Ray et al., 2017). The involvement of the acute phase response was confirmed, including acute phase reactants or proteins, cytokine signaling, oxidative stress and anti-oxidative pathways, muscle contraction and cytoskeletal regulation, lipid metabolism and transport, complement cascades, and several coagulation and hemostasis associated proteins in malaria pathophysiology (Ray et al., 2016, 2017). However, alterations in the blood coagulation cascade, as reported for severe falciparum malaria, were not identified for severe vivax malaria (Ray et al., 2016). Moreover, these proteomic studies allowed the identification of prospective new host markers, such as the differentially expressed proteins superoxide dismutase, ceruloplasmin, vitronectin, titin, and nebulin. Furthermore, they confirmed the already investigated apolipoprotein A1 and E, serum amyloid A and haptoglobin markers. Those are important for future improved diagnosis, discrimination of other infections, as well as disease progression and shift toward severe clinical manifestations, response to new therapies and outcome prediction (Ray et al., 2016). Analysis of a recent longitudinal cohort of vivax malaria patients revealed that some serum levels of proteins such as haptoglobin, apolipoprotein E, apolipoprotein A1, carbonic anhydrase 1, and hemoglobin subunit alpha, revert to baseline levels under treatment, but others did not show the same behavior in the convalescent phase of the infection (Ray et al., 2017), which might reflect the effect on the host of different parasitemias present. Serum proteome results also prompt the malaria community for a clearer definition of severity parameters for P. vivax malaria and show a marked difference between the pathogenesis of infection caused by different Plasmodium parasites (Ray et al., 2016).

The panorama emerging from all malaria proteome studies is that a great fraction of proteins identified until now are uncharacterized and of unknown functions, alongside with several housekeeping proteins. However, other proteins of major metabolic pathways for parasite survival show us that we are in a good position to better understand immune evasion and host cell invasion mechanisms within the pathophysiology of vivax malaria. These pathways comprise metabolism (glycolysis, hemoglobin digestion, nucleic acid synthesis) and cellular invasion (binding proteins, protein synthesis, modification, and degradation) (Figure 5A). Intracellular transport, translocation and presentation of variable antigen proteins (Figure 5B), which promote erythrocyte modification (Figure 5C), have been carefully analyzed, in particular proteins directly related to drug resistance. All chaperonin complexes, some involved in heat shock, oxidative stress and other counteractive responses, have been identified (Acharya et al., 2009, 2011; Chen et al., 2010; Roobsoong et al., 2011; Ray et al., 2012a,b, 2016; Lu et al., 2014; Moreno-Perez et al., 2014; Anderson et al., 2015).

Although there was evidence of transcription for genes encoding almost all P. vivax proteins identified, no correlation was seen between levels of mRNA transcripts and the corresponding protein expression (Bozdech et al., 2008; Westenberger et al., 2010; Bautista et al., 2014; Moreno-Perez et al., 2014; Anderson et al., 2015; Parobek et al., 2016). Integrating genomic and transcriptomic information is paving the way for systems biology approaches. For instance, chokepoint analysis has the potential to uncover enzymes predicted to have only one substrate or product, thus pushing the way to new drug target discoveries. Lists of compounds that could target each chokepoint are being generated using bioinformatics tools from “omics” data analysis.

Analysis of the hypnozoites proteome faces great experimental hurdles. A list of candidate genes includes all homologs of other dormancy genes previously discovered in other organisms (Carlton et al., 2008a). An in vitro system for culturing liver stages of this parasite (Mazier et al., 1984; Hollingdale et al., 1985; Sattabongkot et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2009) and in vivo experimental models are currently under development and will be of importance to approach hypnozoite proteomics. Taken together, blood proteome studies shed light on vivax malaria pathogenesis and pave the way for future integrated multi-omics investigations. However, such an approach has to be interpreted in light of host-parasite interaction, where some reported alterations might be host or parasite related and/or the result of cumulative effects between both parties. Ex vivo specific functional assays may provide further insights.

Plasmodium vivax Genetic and Transcriptomic Diversity, Host-Parasite Dynamics, and Disease Control

The first P. vivax genetic diversity reports were based on a few loci. Researchers relied on the amplification of a small set of polymorphic antigens to assess the genetic diversity of P. vivax. In general, the circumsporozoite protein (CSP), the merozoite surface proteins (MSP), the apical membrane antigen (AMA-1) (Mueller et al., 2002; Cui et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2006; Aresha et al., 2008; Moon et al., 2009; Zakeri et al., 2010), Duffy binding protein (DBP) (Cole-Tobian and King, 2003) and mitochondrial DNA were analyzed (Jongwutiwes et al., 2005; Cornejo and Escalante, 2006) and brought forward the polyclonal nature of P. vivax natural infections. Feng et al. published the first comparative population genomics study between P. falciparum and P. vivax, revealing shared macroscale conserved genetic patterns, but with P. vivax populations showing a highly polymorphic genome for which the degree of diversity depends on the gene context. Thus, coding regions are more conserved than intergenic ones, and central chromosomal regions more than (sub)telomeric, indicative of a purifying selection. This implies an ancient evolutionary history shaped by distinct selection pressures (Feng et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2012). Genes encoding transcription factors (type AP2) and ABC transporters associated with multidrug resistance showed higher dN/dS rate (Dharia et al., 2010; Parobek et al., 2016). The genetic variability seen for P. vivax transcription factors (Hoo et al., 2016) could indicate that malaria parasites evolve by changing and/or expanding their transcription factor DNA binding domains in response to drug administration and host immune challenges (Dharia et al., 2010; Parobek et al., 2016).

Several studies have highlighted the great degree of diversity, which is shared between P. vivax samples of different geographic locations at the population level, strongly suggesting that recent evolutionary selective pressures are currently acting upon some genes at a few loci, mainly those related with drug resistance (Mu et al., 2005; Imwong et al., 2007a; Gunawardena et al., 2010; Neafsey et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2013). Compared to P. falciparum natural isolates from similar geographical regions (Cheeseman et al., 2016), results exposed a greater genetic diversity in P. vivax natural isolates, both for SNP and microsatellites (Karunaweera et al., 2008; Neafsey et al., 2012; Orjuela-Sanchez et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2013; Barry et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2015; Brazeau et al., 2016; Friedrich et al., 2016; Hupalo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016). While microsatellite marker analysis has revealed the genetic diversity of P. vivax infections, they may provide over- or underestimates. This can be attributed to their unstable nature in comparison to SNPs, especially because of the smaller number and/or less informative use of these markers. Therefore, P. vivax high density tiling microarrays (Dharia et al., 2010), WGC sequencing (Bright et al., 2012) and WGS (Bright et al., 2012; Chan et al., 2012; Neafsey et al., 2012; Hester et al., 2013; Winter et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016) are being used to find informative SNPs. Whole genome analysis of genetic diversity between five P. vivax natural isolates (Neafsey et al., 2012) and the Sal-1 strain (Carlton et al., 2008b) has revealed shared gene diversity, but also significant numbers of unique SNPs for each isolate (Hester et al., 2013; Cornejo et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016). Genomic and transcriptomic sequencing of several patient P. vivax isolates resulted in drug resistance phenotype identification (Bright et al., 2012; Mideo et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2015), emergence detection, transmission rates follow-up, as well as the identification (also through proteomics) of rapidly evolving antigens (Boyd and Kitchen, 1937; Cornejo et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Parobek et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016). Genomics data suggest that evolutionary pressures acted upon and currently shape several P. vivax loci associated with invasion of RBC (Figures 5A,B), host and vector immune evasion mechanisms (Figures 5B,C) and antifolate drug resistance, among others (Imwong et al., 2003; Korsinczky et al., 2004; Dharia et al., 2010; Flannery et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016), which could support target discovery (Carlton et al., 2013; Cornejo et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016). For instance, WGS of two patient isolates from Madagascar allowed the identification of recently arisen SNPs present in the DBP region II (Chan et al., 2012). The detection of pvdbp gene duplication (Menard et al., 2013; Hupalo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016) suggests that this gene is under strong positive selection through influence of the human host, and is rapidly evolving in response to the Duffy- allele present in most of sub-Sharan African population, where P. vivax is believed to have originated (Miller et al., 1976; Culleton et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2014). Surprisingly, similar duplications at high frequency have been recently seen in other geographic locations where almost all individuals are Duffy+ (Howes et al., 2011; Pearson et al., 2016). More recently, Auburn and colleagues reported amplification breakpoints for the multidrug resistance 1 gene (pvmdr1) (Auburn et al., 2016b). Thus, P. vivax is considered within an evolutionary neutral model, possibly the outcome of repeated gene duplications (population size expansion) of the ancestral lineage during the course of evolution, or that several sub-populations are present (Parobek et al., 2016). Multi-species WTS data suggests that variability in non-coding sequences of genes but other features such as transcription factors, upstream bidirectional promoter regions, post-transcriptional control including epigenetic regulation, chromatin remodeling events or ncRNAs may have a greater impact on transcription modulation across the Plasmodium spp. (Hoo et al., 2016).

With few exceptions verified in small-scale studies (Winter et al., 2015), P. vivax natural infections are almost always polyclonal (Parobek et al., 2016). However, some haplotype reconstruction studies have reported that 2–4 strains account for the majority of P. vivax gDNA, set against a situation of several different strains equally abundant in one patient (Chan et al., 2012; Neafsey et al., 2012; Winter et al., 2015; Friedrich et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016). For instance, deep genome sequencing of more than 200 clinical Asian-Pacific samples confirmed the complex genetic structure of P. vivax populations showing variations both in the number of dominant clones in individual infection, but also in their degree of relatedness and inbreeding (Pearson et al., 2016). Still, this remarkable polyclonality can have several origins: parasite infection could originate from a single meiosis event, from multiple infections with unrelated parasites as a consequence of several mosquito bites, or from a combination of a relapse and a new infection event, all of them having implications on parasite population diversity (Lin et al., 2015). Microsatellite marker identification and WGS have allowed the characterization of relapse infections as the result of heterologous hypnozoite activation (Imwong et al., 2007b; Carlton et al., 2008a; Restrepo et al., 2011; de Araujo et al., 2012; Bright et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2015). Furthermore, hypnozoites present hidden in the hosts function as a reservoir and a dynamic and continuous source and flow of genetic diversity in the present P. vivax population (White, 2011; Neafsey et al., 2012; Menard et al., 2013; White et al., 2016).

Even though WGS allows determination of informative SNPs, it lacks sensitivity to detect low frequency CNVs present within a polyclonal infection context. The tailored and more affordable P. vivax SNPs barcode project (Baniecki et al., 2015), transcriptome profiling microarrays (Boopathi et al., 2016) and other breakpoint-specific PCR approaches (Auburn and Barry, 2017) can be used as important tools to not only discriminate P. vivax infections and their origin, but also to deliver information of its population dynamics of transmission (Friedrich et al., 2016). Additionally, they are helping to characterize and discern between recrudescence, relapses (Lin et al., 2015), de novo infections (Friedrich et al., 2016) and monitoring drug resistance emergence (Auburn et al., 2016b; Brazeau et al., 2016). As for P. falciparum (Cheeseman et al., 2016), this greater genetic/expression diversity may provide P. vivax with a wide range of alternative paths for successful host erythrocyte invasion (Figures 5A,B) and immune system evasion (Figure 5C), thus enhancing its capacity of adaptation and survival (Cornejo et al., 2015). In addition, the production of an effective vivax malaria vaccine is hampered by the existence of such huge diversity of antigens concentrated in invasion and immune evasion related genes (Neafsey et al., 2012; Winter et al., 2015; Hupalo et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016) in combination with the absence of allelic exclusion and clonal interference mechanisms (Fernandez-Becerra et al., 2005).

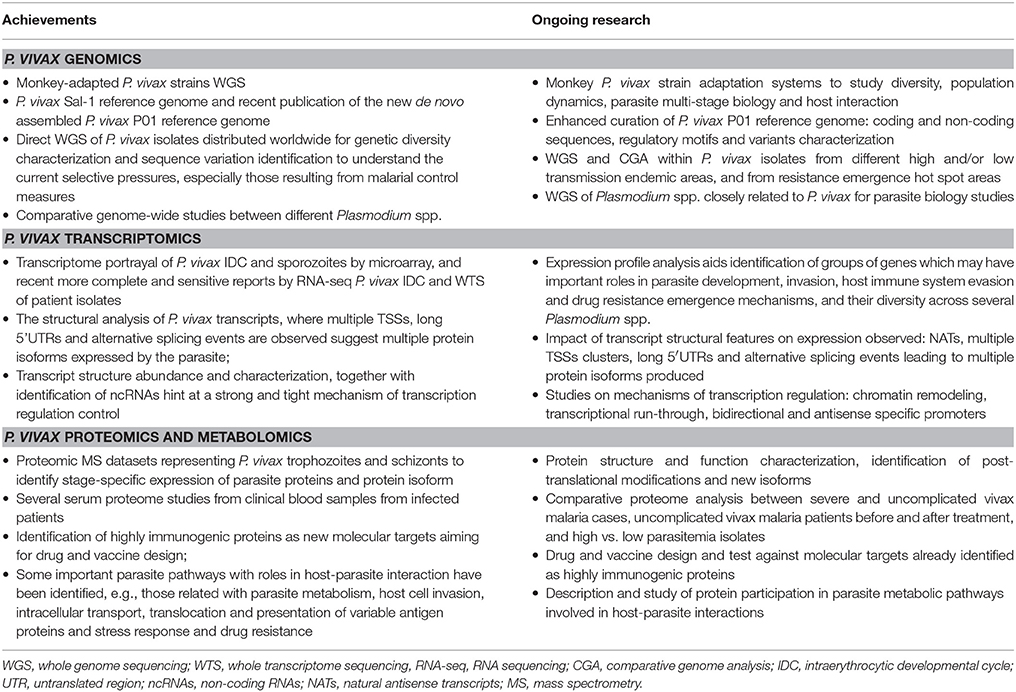

Plasmodium vivax Omics Outlook: Achievements, Gaps, and Future Prospects

During the last 10 years, several P. vivax sequencing projects within the three big omics branches, genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics, have greatly contributed with insights into the parasite's biology (Table 2). The lack of a P. vivax in vitro long-term culturing system is the root of all limitations for its study. Nevertheless, we are living in times of rapid development, expansion and application of high-throughput and highly sensitive technology tools that were absurdly expensive only a few years ago. Exciting progress is being made in single-cell (Nair et al., 2014) and single-molecule sequencing, bringing prospects of complex problem-solving capacity that were previously unthinkable. The development of methodologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing opens new possibilities to understand and further explore gene expression and regulation of malaria parasites. The application of such tools to in vitro cell or animal experimental models may help us explore further some aspects of P. vivax biology and the pathophysiology of disease (Table 3). Specifically, the development, establishment and validation of in vitro cell culture and animal experimental models (as the published Mazier et al., 1984; Hollingdale et al., 1985; Sattabongkot et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2009; Mikolajczak et al., 2015; Mehlotra et al., 2017 reports) to support P. vivax growth would overcome the current number of parasites available for projects in all omics branches. Clearly, this would positively impact on our understanding of several molecular mechanisms taking place in the parasite during cell invasion, development, stage transition, host immune system evasion and environmental stress responses (Table 3).

The extensive and detailed omics datasets that are continuously made available by several research groups, under which technical and experimental progress has and is being achieved brings forward an old problem: how to analyze and integrate large and complex information within and between datasets in a standard and easy-to-share platform, accessible by all. Several initiatives, such as the comparative databases PlasmoDB (Bahl et al., 2003), support malaria research communities by offering computational biology training courses. Such platforms should be continuously developed with the most recent powerful bioinformatics tools and information combined with suitable mathematical modeling and epidemiologic analysis. Mainstream bioinformatics institutes around the world are providing expert support to the Plasmodium research community, critically needed given the extraordinary challenges posed by the complex nature of the P. vivax genome and population genetics. Worldwide, major efforts must be taken by the entire community in order to establish some criteria for dealing with data collection, analysis and annotation, so that it can be easily accessed and fully explored in order to design adequate interventions to ever changing conditions, focusing on the control, elimination and prevention of malaria.

Author Contributions

CB and LA contributed to literature review and writing of the manuscript. CB and AK were responsible for the original figure concept and design. LA, PS, and FC helped with critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2012/16525-2), the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and the Swedish Research Council (2014-4234). CB was supported by a FAPESP fellowship (FAPESP 2013/20509-5). FC is a CNPq research fellow and AK was supported by a CNPq fellowship (150030/2017-7).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ACT, Artemisinin based Combination Therapy; AMA, Apical Membrane Antigen; apDNA, apicoplast DNA; bp, base pairs; CGA, Comparative Genome Analysis; ChIP-seq, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) DNA sequencing; CQ, Chloroquine; CNV, Copy Number Variation; CSP, Circumsporozoite Protein; CVC, caveola-vesicle like complexes; DBP, Duffy Binding Protein; dN, non-synonymous substitution rate; dS, synonymous substitution rate; ETRAMP, Early Transcribed Membrane Protein; gDNA, genomic DNA; IDC, Intraerythrocytic Development Cycle; iRBC, infected Red Blood Cell; Kb, kilobases; Mb, megabases; miRNA, micro RNA; mRNA, messenger RNA; MS, Mass Spectrometry; MSP, Merozoite Surface Protein; MudPIT, multidimensional protein identification technology; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; NAT, Natural Antisense Transcript; ncDNA, nuclear DNA; ncRNA, non-coding RNA; NGS, Next Generation Sequensing; nt, nucleotide; Pexel, Plasmodium export element protein motif; PQ, Primaquine; PST-A, lysophospholipase; PvHIST, P. vivax Plasmodia Helical Interspersed SubTelomeric multigene family proteins (also named as Pf-fam-b) and RAD protein (Pv-fam-e); PvTRAg, P. vivax tryptophan-rich antigen family proteins, also named as Pv-fam-a and tryptophan-rich antigens; PvSTP-1, P. vivax STP1 protein; RBC, Red Blood Cell; RBP, Reticulocyte Binding Protein; RAMA, Rhoptry-Associated Membrane Antigen; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; RT, Reticulocytes; SNP, Single Nucleotide Polymorphism; TAP, Transcriptional Associated Protein; TLR, Toll-like Receptor; TSS, Transcription Starting Site; UTR, Untranslated Regions; VIR, Variable Interspersed Repeat; WGC, Whole Genome Capture; WGS, Whole Genome Sequencing; WGSS, Whole Genome Shotgun Sequencing; WHO, World Health Organization; WTS, Whole Transcriptome Sequencing; 1D LC-MS/MS, one-dimension liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry.

References

Acharya, P., Pallavi, R., Chandran, S., Chakravarti, H., Middha, S., Acharya, J., et al. (2009). A glimpse into the clinical proteome of human malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 3, 1314–1325. doi: 10.1002/prca.200900090

Acharya, P., Pallavi, R., Chandran, S., Dandavate, V., Sayeed, S. K., Rochani, A., et al. (2011). Clinical proteomics of the neglected human malarial parasite Plasmodium vivax. PLoS ONE 6:e26623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026623

Adjalley, S. H., Chabbert, C. D., Klaus, B., Pelechano, V., and Steinmetz, L. M. (2016). Landscape and dynamics of transcription initiation in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Cell Rep. 14, 2463–2475. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.025

Alexandre, M. A., Ferreira, C. O., Siqueira, A. M., Magalhaes, B. L., Mourao, M. P., Lacerda, M. V., et al. (2010). Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria, Brazilian Amazon. Emerging Infect. Dis. 16, 1611–1614. doi: 10.3201/eid1610.100685

Anderson, D. C., Lapp, S. A., Akinyi, S., Meyer, E. V., Barnwell, J. W., Korir-Morrison, C., et al. (2015). Plasmodium vivax trophozoite-stage proteomes. J. Proteomics 115, 157–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.12.010

Andrade, B. B., Reis-Filho, A., Souza-Neto, S. M., Clarencio, J., Camargo, L. M., Barral, A., et al. (2010). Severe Plasmodium vivax malaria exhibits marked inflammatory imbalance. Malar. J. 9:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-13

Anstey, N. M., Handojo, T., Pain, M. C., Kenangalem, E., Tjitra, E., Price, R. N., et al. (2007). Lung injury in vivax malaria: pathophysiological evidence for pulmonary vascular sequestration and posttreatment alveolar-capillary inflammation. J. Infect. Dis. 195, 589–596. doi: 10.1086/510756

Anstey, N. M., Jacups, S. P., Cain, T., Pearson, T., Ziesing, P. J., Fisher, D. A., et al. (2002). Pulmonary manifestations of uncomplicated falciparum and vivax malaria: cough, small airways obstruction, impaired gas transfer, and increased pulmonary phagocytic activity. J. Infect. Dis. 185, 1326–1334. doi: 10.1086/339885

Anstey, N. M., Russell, B., Yeo, T. W., and Price, R. N. (2009). The pathophysiology of vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 25, 220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.02.003

Aresha, M., Sanath, M., Deepika, F., Renu, W., Anura, B., Chanditha, H., et al. (2008). Genotyping of Plasmodium vivax infections in Sri Lanka using Pvmsp-3alpha and Pvcs genes as markers: a preliminary report. Trop. Biomed. 25, 100–106. Available online at: http://www.msptm.org/files/100_-_106_Aresha_Manamperi.pdf

Auburn, S., and Barry, A. E. (2017). Dissecting malaria biology and epidemiology using population genetics and genomics. Int. J. Parasitol. 47, 77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.08.006

Auburn, S., Bohme, U., Steinbiss, S., Trimarsanto, H., Hostetler, J., Sanders, M., et al. (2016a). A new Plasmodium vivax reference sequence with improved assembly of the subtelomeres reveals an abundance of pir genes. Wellcome Open Res 1, 4. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.9876.1

Auburn, S., Marfurt, J., Maslen, G., Campino, S., Ruano Rubio, V., Manske, M., et al. (2013). Effective preparation of Plasmodium vivax field isolates for high-throughput whole genome sequencing. PLoS ONE 8:e53160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053160

Auburn, S., Serre, D., Pearson, R. D., Amato, R., Sriprawat, K., To, S., et al. (2016b). Genomic analysis reveals a common breakpoint in amplifications of the Plasmodium vivax multidrug resistance 1 locus in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 1235–1242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw323

Bahl, A., Brunk, B., Crabtree, J., Fraunholz, M. J., Gajria, B., Grant, G. R., et al. (2003). PlasmoDB: the Plasmodium genome resource. A database integrating experimental and computational data. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 212–215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg081

Baird, J. K. (2004). Chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium vivax. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 4075–4083. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4075-4083.2004

Baird, J. K. (2007). Neglect of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 23, 533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.08.011

Baird, J. K. (2010). Eliminating malaria–all of them. Lancet 376, 1883–1885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61494-8

Baird, J. K., Schwartz, E., and Hoffman, S. L. (2007). Prevention and treatment of vivax malaria. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 9, 39–46. doi: 10.1007/s11908-007-0021-4

Baniecki, M. L., Faust, A. L., Schaffner, S. F., Park, D. J., Galinsky, K., Daniels, R. F., et al. (2015). Development of a single nucleotide polymorphism barcode to genotype Plasmodium vivax infections. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9:e0003539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003539

Barcus, M. J., Basri, H., Picarima, H., Manyakori, C., Sekartuti, Elyazar, I., et al. (2007). Demographic risk factors for severe and fatal vivax and falciparum malaria among hospital admissions in northeastern Indonesian Papua. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77, 984–991. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.984

Barnwell, J. W., and Galinski, M. R. (2014). Malarial liver parasites awaken in culture. Nat. Med. 20, 237–239. doi: 10.1038/nm.3498

Barnwell, J. W., Ingravallo, P., Galinski, M. R., Matsumoto, Y., and Aikawa, M. (1990). Plasmodium vivax: malarial proteins associated with the membrane-bound caveola-vesicle complexes and cytoplasmic cleft structures of infected erythrocytes. Exp. Parasitol. 70, 85–99. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90088-T

Barry, A. E., Waltmann, A., Koepfli, C., Barnadas, C., and Mueller, I. (2015). Uncovering the transmission dynamics of Plasmodium vivax using population genetics. Pathog. Glob. Health 109, 142–152. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000012

Battle, K. E., Gething, P. W., Elyazar, I. R., Moyes, C. L., Sinka, M. E., Howes, R. E., et al. (2012). The global public health significance of Plasmodium vivax. Adv. Parasitol. 80, 1–111. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397900-1.00001-3

Bautista, J. M., Marin-Garcia, P., Diez, A., Azcarate, I. G., and Puyet, A. (2014). Malaria proteomics: insights into the parasite-host interactions in the pathogenic space. J. Proteomics 97, 107–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.10.011

Beeson, J. G., and Crabb, B. S. (2007). Towards a vaccine against Plasmodium vivax malaria. PLoS Med. 4:e350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040350

Beutler, E., Duparc, S., and Group, G. P. D. W. (2007). Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and antimalarial drug development. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77, 779–789. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.779

Bitoh, T., Fueda, K., Ohmae, H., Watanabe, M., and Ishikawa, H. (2011). Risk analysis of the re-emergence of Plasmodium vivax malaria in Japan using a stochastic transmission model. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 16, 171–177. doi: 10.1007/s12199-010-0184-8

Boopathi, P. A., Subudhi, A. K., Garg, S., Middha, S., Acharya, J., Pakalapati, D., et al. (2013). Revealing natural antisense transcripts from Plasmodium vivax isolates: evidence of genome regulation in complicated malaria. Infect. Genet. Evol. 20, 428–443. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.09.026

Boopathi, P. A., Subudhi, A. K., Garg, S., Middha, S., Acharya, J., Pakalapati, D., et al. (2014). Dataset of natural antisense transcripts in P. vivax clinical isolates derived using custom designed strand-specific microarray. Genom Data 2, 199–201. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2014.06.024

Boopathi, P. A., Subudhi, A. K., Middha, S., Acharya, J., Mugasimangalam, R. C., Kochar, S. K., et al. (2016). Design, construction and validation of a Plasmodium vivax microarray for the transcriptome profiling of clinical isolates. Acta Trop. 164, 438–447. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.10.002

Bousema, T., and Drakeley, C. (2011). Epidemiology and infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax gametocytes in relation to malaria control and elimination. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24, 377–410. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00051-10

Boyd, M. F., and Kitchen, S. F. (1937). On the infectiousness of patients infected with Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 17, 253–262. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1937.s1-17.253

Bozdech, Z., Llinas, M., Pulliam, B. L., Wong, E. D., Zhu, J., and DeRisi, J. L. (2003). The transcriptome of the intraerythrocytic developmental cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 1:E5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000005

Bozdech, Z., Mok, S., Hu, G., Imwong, M., Jaidee, A., Russell, B., et al. (2008). The transcriptome of Plasmodium vivax reveals divergence and diversity of transcriptional regulation in malaria parasites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16290–16295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807404105

Brazeau, N. F., Hathaway, N., Parobek, C. M., Lin, J. T., Bailey, J. A., Lon, C., et al. (2016). Longitudinal pooled deep sequencing of the Plasmodium vivax K12 kelch gene in cambodia reveals a lack of selection by artemisinin. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95, 1409–1412. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0566

Bright, A. T., Manary, M. J., Tewhey, R., Arango, E. M., Wang, T., Schork, N. J., et al. (2014). A high resolution case study of a patient with recurrent Plasmodium vivax infections shows that relapses were caused by meiotic siblings. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8:e2882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002882