- CNRS UMR 7278, IRD198, INSERM U1095, Aix-Marseille Université, Marseille, France

Pediculus humanus humanus is an human ectoparasite which represents a serious public health threat because it is vector for pathogenic bacteria. It is important to understand and identify where bacteria reside in human body lice to define new strategies to counterstroke the capacity of vectorization of the bacterial pathogens by body lice. It is known that phagocytes from vertebrates can be hosts or reservoirs for several microbes. Therefore, we wondered if Pediculus humanus humanus phagocytes could hide pathogens. In this study, we characterized the phagocytes from Pediculus humanus humanus and evaluated their contribution as hosts for human pathogens such as Rickettsia prowazekii, Bartonella Quintana, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Introduction

Pediculus humanus humanus is a strictly human ectoparasite with a worldwide distribution (Brouqui and Raoult, 2006) and represents a serious public health threat because it acts as a vector for pathogenic bacteria (Raoult and Roux, 1999). Human body lice may transmit epidemic typhus, which is caused by Rickettsia prowazekii (Bechah et al., 2008), the louse-borne relapsing fever, which is caused by Borrelia recurrentis (Houhamdi and Raoult, 2005), and trench fever, which is caused by Bartonella quintana (Badiaga and Brouqui, 2012). It has also been described that body lice can vectorize Acinetobacter baumannii (La Scola and Raoult, 2004). Because body lice are vectors of several human diseases, it is important to understand and identify the compartments (organs, tissue, cells) in which these bacteria reside to define new strategies to counterstroke the capacity of vectorization of the bacterial pathogens by body lice.

Whereas the immune systems of several invertebrates, such as mosquitos (Blandin and Levashina, 2007; Hillyer, 2009), shrimps (Tassanakajon et al., 2013), fruit flies (Kounatidis and Ligoxygakis, 2012), Caenorhabditis elegans (Pukkila-Worley and Ausubel, 2012), and more recently, Mytilus galloprovincialis (Koutsogiannaki et al., 2014), have been investigated, there is a crucial lack of knowledge concerning the immune system of body lice.

In 2012, evidence suggesting that the immune system of Pediculus humanus humanus relies on phagocytosis was reported (Kim et al., 2012), which implied the existence and function of phagocytic cells in these organisms. It is known that phagocytes from vertebrates can be hosts or reservoirs for several microbes. Therefore, we wondered if Pediculus humanus humanus phagocytes could hide pathogens.

In this study, we characterized the phagocytes from Pediculus humanus humanus and evaluated their contribution as hosts for human pathogens such as Rickettsia prowazekii, Bartonella quintana and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Results

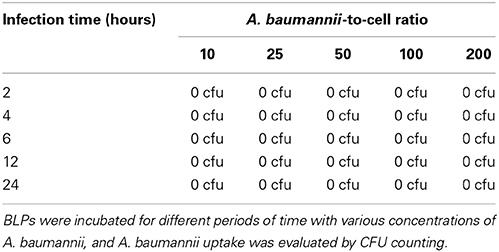

Body Lice Hemocyte Preparation and Culture

To purify hemolymph phagocytes, we took advantage of the phagocytes' adherence to coated dishes. Hemolymphs in the abdomen of the body louse (Figure 1A) was collected and incubated at either 28 or 37°C in different culture media (EMEM, RPMI, L-15, Schneider) in the presence or absence of CO2 (Figures 1B–D), and the percentage of adherent cells was measured after 16 h of incubation. At 37°C or 28°C and in the presence of CO2, approximately 10% of cells were adherent, independent of the type of culture medium used (Figure 1B). Similar results were obtained at 37°C in the absence of CO2 (Figure 1C). At 28°C and in the absence of CO2, approximately 70% of cells were adherent when grown in Schneider medium (Figures 1C,D), whereas less than 55% of cells were adherent in the other medium conditions (Figures 1C,D). Furthermore, 7-day-old hemocytes could be maintained in Schneider medium without extensive cell death. Indeed, after 4 days of culture, cell viability of 72% was observed (Figure 1E), and after 7 days of culture, the cell viability decreased to 46%. Beyond 7 days, the cell viability decreased more rapidly, reaching 6% on the 15th day in culture (Figure 1E). Therefore, the subsequent experiments were performed in Schneider medium for no more than 7 days.

Figure 1. Body lice hemocyte preparation and culture. (A) Hemolymph was collected from the abdomen of Pediculus humanus humanus (black arrow) using an insulin syringe equipped with a 29G needle. Scale bar, 400 μm. (B,C) The collected hemolymph was added to various culture media in the (B) presence or (C) absence of CO2. After 16 h, the number of adherent cells in each condition was evaluated, and the percentage of adherent cells was calculated. The results are expressed as the means ± SDs (n = 5) (*p < 0.05). (D) Representative image of adherent cells observed under phase contrast microscopy after incubation at 28°C without CO2 in (a) EMEM, (b) RPMI, (c) L-15 medium, or (d) Schneider medium. Scale bar, 25 μm. (E) Hemocytes from Pediculus humanus humanus were cultivated in Schneider medium at 28°C without CO2 for 15 days, and their viability was evaluated each day by counting cells. The results are expressed as the mean percentages of viable cells ± SDs (n = 3).

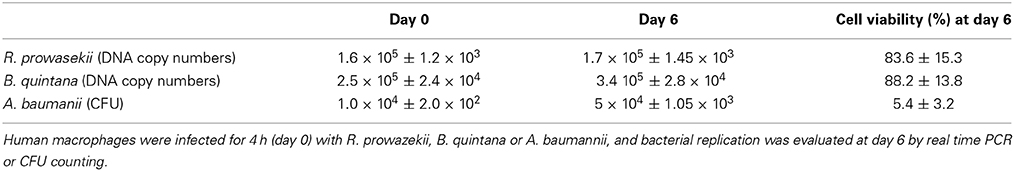

Characterization of the Phagocytic Properties of Body Lice Hemocytes

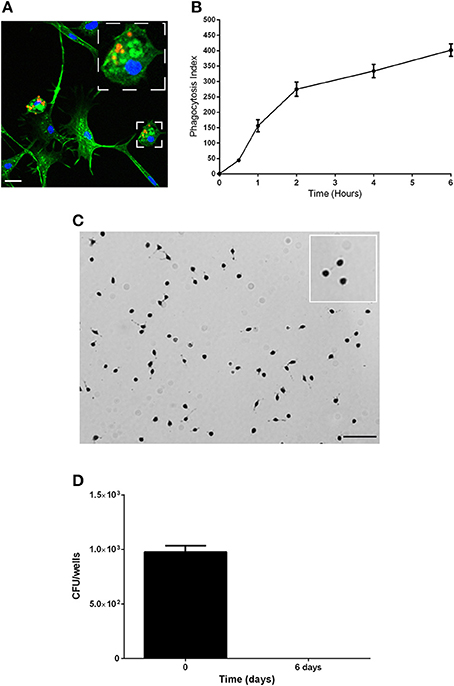

We then analyzed the functional properties of the isolated adherent cells to define their phagocytic and microbicidal activities. Mammalian cells that are able to ingest particles, generate ROS and clear bacteria are often considered phagocytes (Aderem and Underhill, 1999; Underhill and Ozinsky, 2002; Puertollano et al., 2011; Underhill and Goodridge, 2012). First, the capacity of the cells to phagocytose was evaluated (Figures 2A,B). The cells were incubated with latex beads at 28°C, and the number of beads captured per cell (Figure 2A) (phagocytosis index) was evaluated at various time points (Figure 2B). The adherent cells internalized latex beads in a time-dependent manner, and after 30 min, 17% of the cells had phagocytosed 2–3 latex beads; thus, the phagocytosis index was 44.2 ± 5.40 (Figure 2B). The percentage of cells that phagocytosed beads and the number of beads per cell increased over time. After 6 h, the phagocytosis index reached 401.6 ± 20.1, with 80% of cells having internalized at least 5 beads/cell (Figures 2A,B).

Figure 2. Characterization of the phagocytic properties of the body lice hemocytes. (A,B) The phagocytic capacity of the hemocytes was assessed based on their capacity to internalize latex beads (1/5000 dilution) over time at 28°C. (A) Representative image of actin-labeled cells (green) that had internalized latex beads (red). Scale bar, 10 μM. (B) The number of beads per cell and the percentage of cells containing engulfed beads were evaluated by microscopy, and these results were used to calculate the phagocytosis index. The mean ± SD is shown (n = 3). (C) The production of reactive oxygen species was evaluated using a NBT test. Cells were incubated with latex beads in Schneider medium at 28°C to stimulate the production of ROS, and the cells were observed by microscopy. Nearly more than 85% of cells were blue, indicating that they all produced ROS. Images representative of 3 experiments are shown. (D) The microbicidal activity of the hemocytes was evaluated by measuring their capacity to eliminate the non-pathogenic bacterial strain E. coli K12. Replication was evaluated by cfu counting. The results are shown as the means ± SDs (n = 2).

Second, the capacity of the isolated adherent cells to possess microbicidal activities was assessed by analyzing the ability of the adherent cells to produce ROS and to eliminate non-pathogenic bacteria. To evaluate ROS production, we used Nitro blue tetrazolium assays (NBT). We observed the formation of formazan precipitates in more than 85% of cells, which demonstrated that adherent cells produce ROS (Figure 2C). To evaluate the microbicidal capacity of the isolated hemocytes, cells were incubated with the non-pathogenic bacterial strain E. coli K12, and the behaviors of the bacteria were followed by cfu counting (Figure 2D). We found that E. coli were phagocyted by the hemocytes and then eliminated. Indeed, after 4 h (day 0) of incubation 976 ± 58 cfu were detected, and after 6 days, bacteria were not detected (no cfu). Taken together, these data show that hemocytes are able to phagocytose and that they have microbicidal activities; therefore, we named these adherent cells from the body louse hemolymph as body louse phagocytes (BLPs).

BLPs are Reservoirs for Human Pathogens

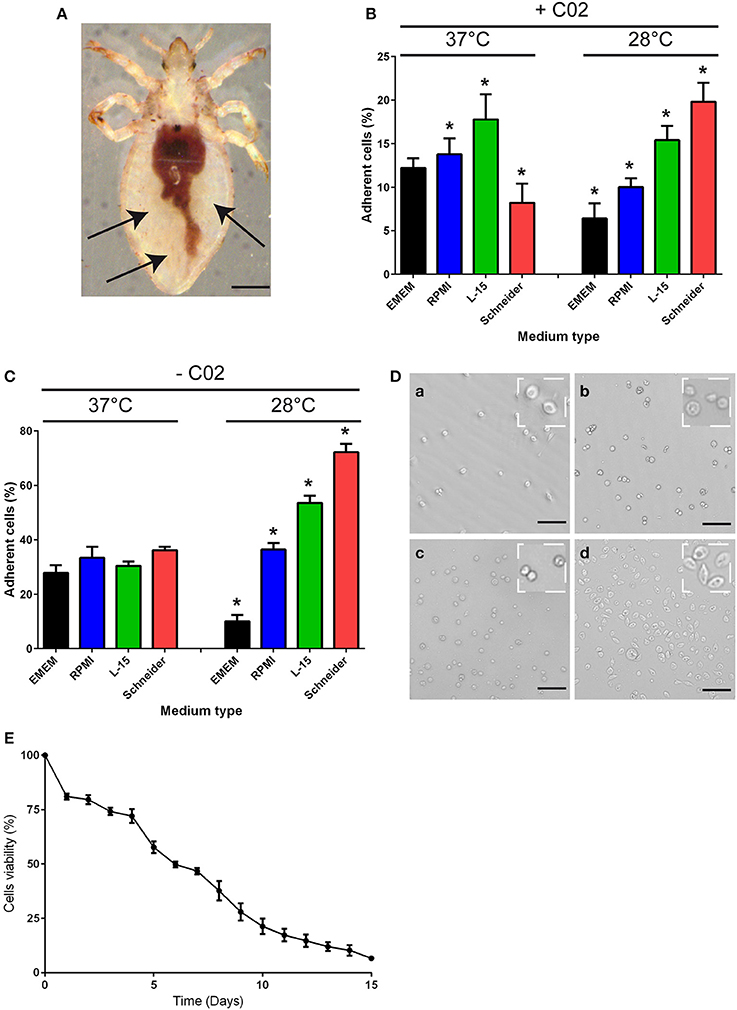

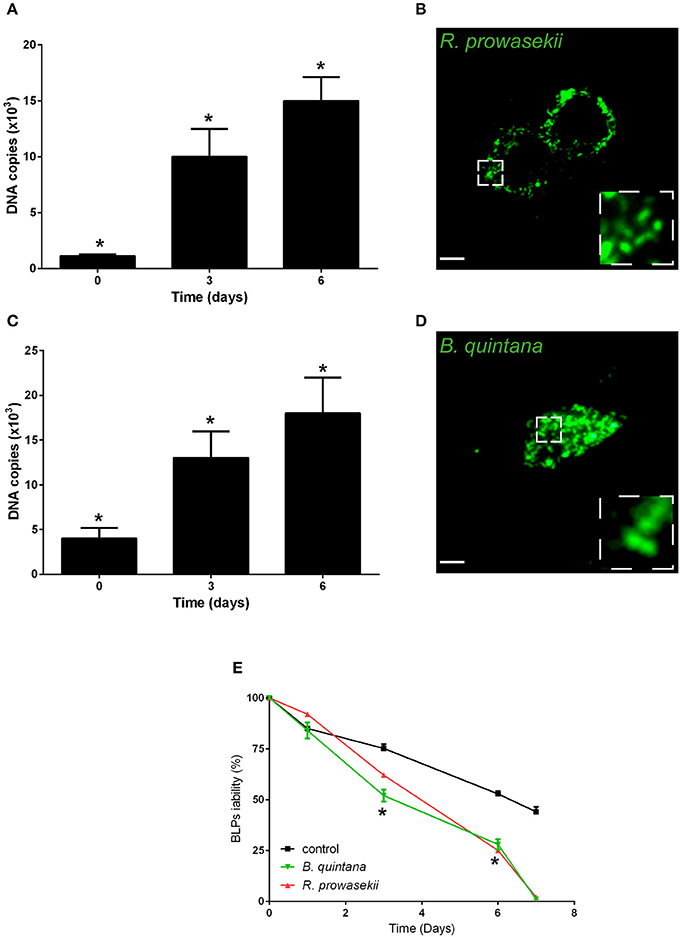

Next, we investigated whether BLPs may serve as hosts for bacterial pathogens. For that, we selected several microbes that are vectorized by Pediculus humanus humanus, including R. prowazekii, B. quintana, and A. baumannii. BLPs were infected with the set of selected microbes and cultivated for several days at 28°C in Schneider medium, and the bacterial behaviors and BLP viability were evaluated (Figure 3). After internalization, R. prowazekii survived and replicated in BLPs. Indeed, using real time PCR, we detected 1 × 103 ± 140 copies of bacterial DNA after 4 h of infection (day 0); the number of copies of bacterial DNA increased at day 3 and then reached 1.5 × 104 ± 2 × 103 copies 6 days post-infection (Figures 3A,B). We observed that R. prowazekii replication dramatically affected the viability of the BLPs (Figure 3E), and thus bacterial replication led to BLP death and bacterial release into the culture medium. In a similar manner, we found that B. quintana was internalized by BLPs (4 × 103 ± 1.20 × 103 B. quintana DNA copies) and that B. quintana replicated in the phagocytes (1.8 × 104 ± 4 × 103 B. quintana DNA copies at day 6) (Figures 3C,D). As for R. prowazekii, BLPs infected with B. quintana exhibited decreased viability (Figure 3E). Surprisingly, we observed that A. baumannii was not internalized by BLPs, and this lack of internalization was independent of the infection time or the bacteria-to-cell ratio (Table 1).

Figure 3. BLPs are reservoirs for R. prowazekii and B. quintana. Body lice phagocytes were infected for 4 h (day 0) with R. prowazekii (100 bacteria-to-cell ratio) or B. quintana (100 bacteria-to-cell ratio), bacterial replication was then evaluated by real time PCR, and cell viability was evaluated. (A) R. prowazekii replicate in BLPs. The results are shown as the means ± SDs (n = 4, *p < 0.05). (B) Representative epifluorescence microscopy image of body lice phagocytes infected with R. prowazekii (green) at 6 days post-infection. Scale bar, 25 μm. (C) B. quintana replicate in BLPs. The results are shown as the means ± SDs (n = 3, *p < 0.05). (D) Representative epifluorescence microscopy image of body lice phagocytes infected with B. quintana (green) at 6 days post-infection. (E) Cell viability was evaluated by cell counting. The results are shown as the means ± SDs (n = 3, *p < 0.05).

To complete the analysis, we compared the behaviors of the bacteria in BLPs to their behaviors in human macrophages. Interestingly, we found that R. prowazekii, B. quintana, and A. baumannii were able to infect human macrophages (Table 2). R. prowasekii and B. quintana survived but did not replicate in human macrophages, whereas A. baumannii replicated and induced the death of human macrophages (Table 2). Taken together, these results revealed that BLPs were unable to eliminate R. prowazekii and B. quintana and allowed their replication.

Discussion

Several experimental models of body louse infestation (Houhamdi et al., 2002) have shown that body lice acquire R. prowazekii after feeding from an infected host, thereby allowing R. prowazekii to infect the epithelial cells of the upper gut of the lice (Houhamdi et al., 2002). While the immune systems of insects such as Drosophila melanogaster (Lemaitre and Hoffmann, 2007) have been carefully investigated, few studies have focused on the immune systems of body lice (Pedra et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2012). Recently, it was reported that the immune system of body lice involves a humoral immune response that requires phagocytosis (Kim et al., 2012). However, the cells involved in this process were not characterized, and their contributions to disease vectorization by the body louse Pediculus humanus humanus remained unknown. We have isolated hemocytes from body louse hemolymph and have unraveled the capacity of these cells to produce ROS and to internalize and eliminate non-pathogenic bacteria, similar to mammalian phagocytes. Thus, we suggest that body lice hemocytes are phagocytic cells (BLPs) that are fully equipped to have antimicrobicidal activity. Body lice, similar to other organisms, have an immune system containing phagocytes.

Next, we investigated the capacity of BLPs to be infected by human pathogens vectorized by Pediculus humanus humanus. BLPs were able to phagocytose pathogens such as R. prowazekii and B. quintana; however, despite their antimicrobial capacity, BLPs were unable to eliminate internalized R. prowazekii. In addition, we found that R. prowazekii and B. quintana replicated within BLPs. Interestingly, we observed that replication of R. prowazekii and B. quintana induced BLP lysis, and thus, the bacteria were released into the culture media. Surprisingly, A. baumannii is not internalized by BLPs, indicating that BLPs are not permissive to A. baumannii. We compared the behaviors of R. prowazekii, B. quintana and A. baumannii in BLPs to their behaviors in human macrophages. Interestingly, the becoming of R. prowazekii and B. quintana into human macrophages was different than in BLPs. Indeed, we observed survival of R. prowazekii and B. quintana in human macrophages; however, these bacteria replicated strongly in BLPs. This finding suggests that BLPs most likely do not have the microbicidal equipment to kill R. prowazekii and B. quintana, in contrast to human macrophages. Unlike A. baumannii, R. prowazekii and B. quintana, we found that A. baumannii were not internalized by BLPs, whereas there were internalized by macrophages. It is possible that receptors allowing A. baumannii uptake in mammalian phagocytes are not expressed by BLPs or are not conserved from mammalian phagocytes to BLPs.

Our results suggest that BLPs might host microbes and contribute to making Pediculus humanus humanus a vector for human diseases. In addition, our data provide new knowledge about the possible localization of human pathogens in body lice. It was known that R. prowazekii invades the gut cells (Houhamdi et al., 2002); here, we discover that hemocytes can also be hosts for this pathogenic bacterium. Moreover, the death of the BLPs during bacterial replication might contribute to the spreading of the bacteria into the body lice, and thus, this could be a method for bacterial contamination of the host. It is possible that some viruses and microbes that are responsible for human diseases have no identified vectors because there are hiding in hemocytes, which is small population of the cells of body lice (we scored ~750 hemocytes/body lice), and thus, the microbes responsible for human diseases could not be detectable using the classical methods of investigation. We also suggest that, in the near future, it will be important to search for viruses and microbes that infect BLPs because as amoebas, BLPs could be reservoirs for unidentified pathogens. In conclusion, we have characterized phagocytes of body lice and unraveled their capacity to be vectors for human pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Media

PMI 1640, DMEM Leibovitz's 15 medium, and Schneider medium were obtained from Invitrogen and were supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL) and 100 U/ml penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), gentamycin (10 μg/ml), and vancomycin (5 μg/ml). Before the experiments, the antibiotics were removed by extensive washing.

Bacterial Strains

Rickettsia prowazekii (Rp22 strain) (Birg et al., 1999; Bechah et al., 2010), Bartonella quintana strain Oklahoma (ATCC 49793) (Kernif et al., 2014), and Acinetobacter baumannii homeless isolate (La Scola and Raoult, 2004) were grown as previously described.

Body Lice Strains

Colonies of Pediculus humanus humanus, strain Orlando, were grown as previously described (Fournier et al., 2001).

Hemolymph Collection

Pediculus humanus humanus were starved for 48 h and then washed 3 times in each of four successive solutions: solution A, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7, plus Tween 80 (0.1%); solution B, sterile water; solution C, 70% ethanol; solution D, sterile PBS, pH 7. The hemolymph was collected from the abdomens of body lice using an insulin syringe equipped with 29G needles. The collected hemolymph was added to the culture media.

Cell Viability

The percentage of adherent cells was measured using a phase contrast microscope (Leica DMI 3000 B; Leica, France) as previously described (Prescott and Breed, 1910).

Phagocytosis Assay

Cells were incubated at day 3 with latex beads (1 μm, Sigma) at 28°C, washed extensively to remove non-internalized beads and then fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Using an epifluorescence microscope (Leica DMI 3000 B), the numbers of latex beads per cell and the numbers of cells containing latex beads were evaluated. The phagocytosis index is defined as (the average number of latex beads per cell in cells containing latex beads) × (the percentage of cells containing beads).

Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species

The production of reactive oxygen species was evaluated using the NBT test, as previously described (Jozefowski and Marcinkiewicz, 2010). The cells were incubated with latex beads (1 μm, Sigma) for 2 h in Schneider medium at 28°C to induce the production of ROS.

Bacterial Infection

BLPs were infected with R. prowazekii, B. Quintana, or A. baumannii and then extensively washed to remove the free bacteria; the BLPs were then incubated further. In some experiments, the bacteria were visualized by immunofluorescence, as previously described (Bechah et al., 2010), and cellular F-actin was stained using Alexa 488-conjugated phallacidin. Infection was quantified by real time PCR or cfu counting.

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as the means ± SDs and were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

We thank Berthe Amelie Iroungou for technical assistance.

References

Aderem, A., and Underhill, D. M. (1999). Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Badiaga, S., and Brouqui, P. (2012). Human louse-transmitted infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 332–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03778.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bechah, Y., Capo, C., Mege, J. L., and Raoult, D. (2008). Epidemic typhus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8, 417–426. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70150-6

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bechah, Y., El Karkouri, K., Mediannikov, O., Leroy, Q., Pelletier, N., Robert, C., et al. (2010). Genomic, proteomic, and transcriptomic analysis of virulent and avirulent Rickettsia prowazekii reveals its adaptive mutation capabilities. Genome Res. 20, 655–663. doi: 10.1101/gr.103564.109

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Birg, M. L., La Scola, B., Roux, V., Brouqui, P., and Raoult, D. (1999). Isolation of Rickettsia prowazekii from blood by shell vial cell culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 3722–3724.

Blandin, S. A., and Levashina, E. A. (2007). Phagocytosis in mosquito immune responses. Immunol. Rev. 219, 8–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00553.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brouqui, P., and Raoult, D. (2006). Arthropod-borne diseases in homeless. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1078, 223–235. doi: 10.1196/annals.1374.041

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fournier, P. E., Minnick, M. F., Lepidi, H., Salvo, E., and Raoult, D. (2001). Experimental model of human body louse infection using green fluorescent protein-expressing Bartonella quintana. Infect. Immun. 69, 1876–1879. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1876-1879.2001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hillyer, J. F. (2009). Transcription in mosquito hemocytes in response to pathogen exposure. J. Biol. 8:51. doi: 10.1186/jbiol151

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Houhamdi, L., Fournier, P. E., Fang, R., Lepidi, H., and Raoult, D. (2002). An experimental model of human body louse infection with Rickettsia prowazekii. J. Infect. Dis. 186, 1639–1646. doi: 10.1086/345373

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Houhamdi, L., and Raoult, D. (2005). Excretion of living Borrelia recurrentis in feces of infected human body lice. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 1898–1906. doi: 10.1086/429920

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jozefowski, S., and Marcinkiewicz, J. (2010). Aggregates of denatured proteins stimulate nitric oxide and superoxide production in macrophages. Inflamm. Res. 59, 277–289. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0096-5

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kernif, T., Leulmi, H., Socolovschi, C., Berenger, J. M., Lepidi, H., Bitam, I., et al. (2014). Acquisition and excretion of Bartonella quintana by the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis felis. Mol. Ecol. 23, 1204–1212. doi: 10.1111/mec.12663

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, J. H., Min, J. S., Kang, J. S., Kwon, D. H., Yoon, K. S., Strycharz, J., et al. (2012). Comparison of the humoral and cellular immune responses between body and head lice following bacterial challenge. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41, 332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.01.011

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kounatidis, I., and Ligoxygakis, P. (2012). Drosophila as a model system to unravel the layers of innate immunity to infection. Open Biol. 2:120075. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120075

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Koutsogiannaki, S., Franzellitti, S., Fabbri, E., and Kaloyianni, M. (2014). Oxidative stress parameters induced by exposure to either cadmium or 17beta-estradiol on Mytilus galloprovincialis hemocytes. The role of signaling molecules. Aquat. Toxicol. 146, 186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.11.005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

La Scola, B., and Raoult, D. (2004). Acinetobacter baumannii in human body louse. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 1671–1673. doi: 10.3201/eid1009.040242

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lemaitre, B., and Hoffmann, J. (2007). The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pedra, J. H., Brandt, A., Li, H. M., Westerman, R., Romero-Severson, J., Pollack, R. J., et al. (2003). Transcriptome identification of putative genes involved in protein catabolism and innate immune response in human body louse (Pediculicidae: Pediculus humanus). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33, 1135–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00133-4

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Prescott, S. C., and Breed, R. S. (1910). The determination of the number of body cells in milk by a direct method. Am. J. Public Hygiene 20, 663–664.

Puertollano, M. A., Puertollano, E., De Cienfuegos, G. A., and De Pablo, M. A. (2011). Dietary antioxidants: immunity and host defense. Curr. Top Med. Chem. 11, 1752–1766. doi: 10.2174/156802611796235107

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pukkila-Worley, R., and Ausubel, F. M. (2012). Immune defense mechanisms in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal epithelium. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.10.004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Raoult, D., and Roux, V. (1999). The body louse as a vector of reemerging human diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29, 888–911. doi: 10.1086/520454

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tassanakajon, A., Somboonwiwat, K., Supungul, P., and Tang, S. (2013). Discovery of immune molecules and their crucial functions in shrimp immunity. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 34, 954–967. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.09.021

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Underhill, D. M., and Goodridge, H. S. (2012). Information processing during phagocytosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 492–502. doi: 10.1038/nri3244

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Underhill, D. M., and Ozinsky, A. (2002). Phagocytosis of microbes: complexity in action. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 825–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.103001.114744

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: phagocytes, body lice, typhus

Citation: Coulaud P-J, Lepolard C, Bechah Y, Berenger J-M, Raoult D and Ghigo E (2015) Hemocytes from Pediculus humanus humanus are hosts for human bacterial pathogens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4:183. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00183

Received: 04 November 2014; Accepted: 10 December 2014;

Published online: 30 January 2015.

Edited by:

Benjamin Coiffard, Hôpital Nord, FranceReviewed by:

Stephane Gasman, CNRS, FranceBenjamin Coiffard, Hôpital Nord, France

Massimo Mallardo, University of Naples, Italy

Copyright © 2015 Coulaud, Lepolard, Bechah, Berenger, Raoult and Ghigo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eric Ghigo, Faculté de Médecine, URMITE, 27 Bld. Jean Moulin, 13385 Marseille 05, France e-mail:ZXJpYy5naGlnb0B1bml2LWFtdS5mcg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Pierre-Julien Coulaud†

Pierre-Julien Coulaud† Didier Raoult

Didier Raoult Eric Ghigo

Eric Ghigo