94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Chem., 26 September 2024

Sec. Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2024.1465459

This article is part of the Research TopicMedicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry Editor's Pick 2024View all 10 articles

Venoms are complex mixtures produced by animals and consist of hundreds of components including small molecules, peptides, and enzymes selected for effectiveness and efficacy over millions of years of evolution. With the development of venomics, which combines genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to study animal venoms and their effects deeply, researchers have identified molecules that selectively and effectively act against membrane targets, such as ion channels and G protein-coupled receptors. Due to their remarkable physico-chemical properties, these molecules represent a credible source of new lead compounds. Today, not less than 11 approved venom-derived drugs are on the market. In this review, we aimed to highlight the advances in the use of venom peptides in the treatment of diseases such as neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, or cancer. We report on the origin and activity of the peptides already approved and provide a comprehensive overview of those still in development.

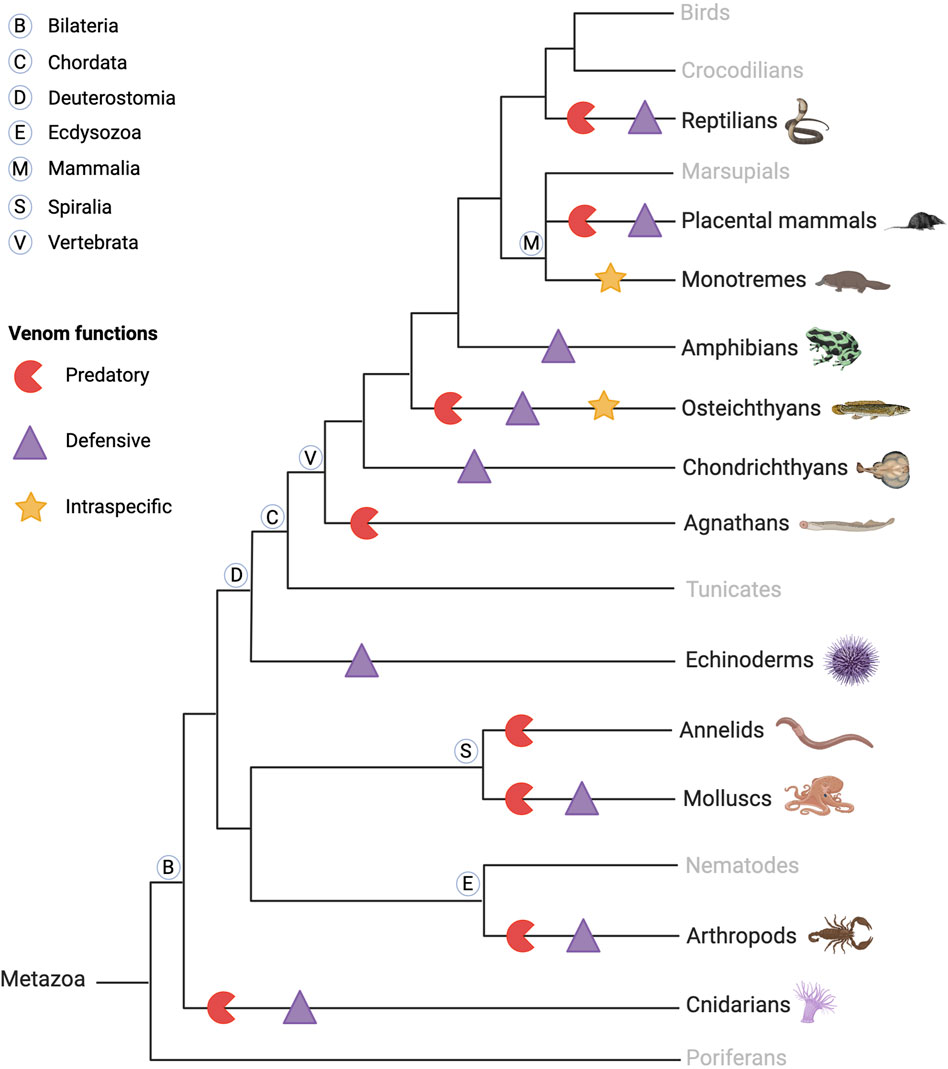

Venomous animals are widely distributed taxonomically, represented in both invertebrates (annelids, arthropods, mollusks, nematodes, cnidarians … ) and vertebrates (platypus, snakes, lizards, fish, shrews … ), as shown in Figure 1 (Morsy et al., 2023). Venomous species are ubiquitous, having colonized many aquatic and terrestrial biotopes, in temperate, tropical, and equatorial areas. Fry et al. have defined venom as “a secretion, produced in a specialized gland in an animal, and delivered to a target animal through the infliction of a wound” (Fry et al., 2009). However, in addition to predation and defense, venom serves various functional roles including communication, mating, and offspring care (Schendel et al., 2019). Animal venoms are complex chemical cocktails composed of hundreds of molecules, mostly peptides, and proteins, but also small molecules and salts. Peptides and proteins from venoms are commonly referred to as toxins, but enzymes have also been identified among them (Simoes-Silva et al., 2018). The main families of venom enzymes are L-amino oxidases (LAAOs), phospholipases A2 (PLA2s), proteinases (especially snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs), and snake venom serine proteinases (SVSPs) in snake venoms), acetylcholinesterases, and hyaluronidases. Even if they have a deleterious effect on the prey, such enzymes are not (always) considered to be toxins (Utkin, 2015).

Figure 1. Schematic phylogenetic tree of venomous animal diversity and key venom functions. Venomous animals are found in invertebrates and vertebrates, aquatic and terrestrial animals, and predators and prey. They use their venom for predation and defense, and some use their venom against conspecifics, intraspecifically, in competition for reproduction, as in the platypus. Created with BioRender.com (2024) and inspired by Schendel et al. (2019).

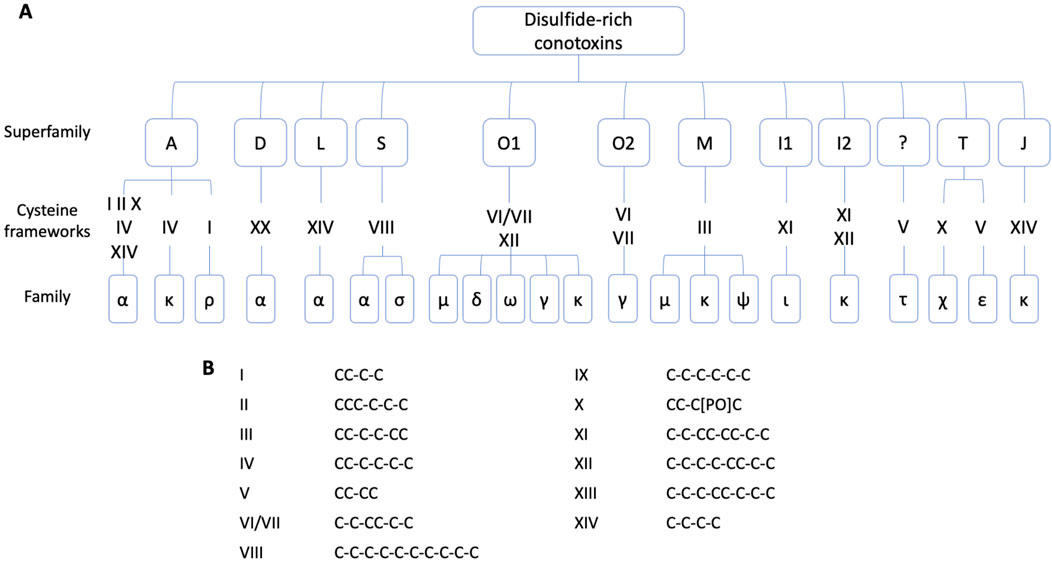

Venomous animals have evolved highly complex venoms over millions of years of evolution. Based on recent transcriptomic and proteomic studies, it is generally accepted that an average of a few hundred toxins are present in each venom. Knowing that hundreds of thousands of venomous species have been identified to date, animal venoms can be seen as an incredibly diverse molecular toolbox composed of tens of millions of bioactive peptides and proteins (Herzig et al., 2020). Biologically active venom peptides and proteins act selectively and efficiently against molecular targets, such as ion channels (ICs) and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) but also enzyme-linked receptors (Ghosh et al., 2019; Utkin et al., 2019). Venom toxins have the incredible ability to activate, inhibit, or modulate their functions paving the way for the elucidation of critical physiological processes. From a molecular structural point of view, venom toxins are mostly highly structured peptides with disulfide bridges, providing the molecule with the perfect conformation to bind to the receptors and conferring high stability and resistance to proteases (King, 2013).

Venoms exhibit high chemical diversity and exert a wide range of pharmacological activities. Their toxins act at low doses with high selectivity for receptors, and even for specific subtypes of receptors. From this simple point of view, toxins are extremely attractive for developing therapeutic drugs. However, some of them are not as selective and may target not only a single (sub)type of receptor but a variety of them. In that context, the development of innovative pharmacological drugs appears tricky, if not possible, as the new tool acts on the receptor of interest, without activating additional receptors that may be involved in critical physiological functions (Smith et al., 2015). As these requirements are never met, such polypharmacological toxins are usually discarded from the pool of interest. In the development of toxin-based therapies, the blood-brain barrier passage remains another major obstacle that researchers are actively trying to overcome. It has been shown that adding positively charged amino acids to the terminal ends of the peptide improves its delivery to the target (Teesalu et al., 2009). Although such modification generally reduces potency, it increases the half-life of the active venom-derived peptide drugs. Another critical parameter to explore is oral bioavailability, which depends on the mass and hydrophobicity of the drug candidates. This is not necessarily limiting, depending on the target site of action. Intravenous or local administration is a credible option to circumvent this difficulty (Stepensky, 2018). While toxins can be valuable in therapeutic research, understanding their pharmacological properties, including pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics is critical to the successful development of a lead peptide.

Despite these challenges, the potential for venom peptides in developing therapeutic molecules remains significant. Therefore, venom peptides are ideal candidates for developing novel therapeutic molecules due to their high potency, selectivity, and stability (Holford et al., 2018). To date, eleven venom-derived molecules have been approved and marketed for the treatment of disease from lizard (exenatide and lixisenatide), cone snail (ziconotide), leech (bivalirudin and desirudin), and snake (captopril, enalapril, tirofiban, eptifibatide, batroxobin, and cobratide) venoms. These drugs are used: as anticoagulants for bivariludin and desirudin, as antithrombotics for eptifibatide and tirofiban, as defibrinogenating agents for batroxobin, in case of hypertension for captopril and enalapril, to reduce pain for cobratide and ziconotide, and to treat type 2 diabetes for exenatide and lixisenatide. These drugs are synthetic toxins or molecules derived from natural toxins (Bordon et al., 2020). Many studies are underway in preclinical and clinical settings for treating chronic pain, certain cancers, depression, or diabetes (Miljanich, 2004; Mamelak et al., 2006; Osteen et al., 2016). In this context, this review proposes a journey in the recent advances of venom toxins exploited in potential treatments for both cancer and non-cancer diseases. For the reader’s information, this review will not discuss the antimicrobial activity of toxins. More information can be obtained from the review Antimicrobials from Venomous Animals: An Overview by Yacoub et al. (2020).

Venomous snakes cause up to 2.7 million cases of envenomation worldwide each year (WHO, 2021). Venom toxins and enzymes disrupt the victim’s physiological systems and cause morbidity or even death if left untreated. The therapeutic use of snake venom was documented in Ayurveda as early as the 7th century and was also mentioned by ancient Greek philosophers and physicians for its pharmacological properties (King, 2013). More recently, technological advances have allowed researchers to transform these potentially deadly toxins into life-saving therapeutics. Components of snake venom have shown potential for the development of new drugs, from the development of captopril, the first drug derived from the bradykinin-potentiating peptide of Bothrops jararaca (southeast coast of South America), to disintegrins with potent activity against certain types of cancer. Snake venom exhibits cytotoxic, neurotoxic, and hemotoxic activities, making it the focus of many research projects. The study of the cytotoxic properties of venoms for cancer treatment is ongoing. Despite extensive research on the neurotoxicity of snake venoms for neuronal diseases, no drug derived from snake toxin has been marketed for this purpose. Due to the complexity of the neuronal system, this area of research is still in progress (Oliveira et al., 2022).

The classification proposed by Tasoulis and Isbister in 2017 identifies four primary (see Table 1) and six secondary protein families (see Table 2) (Tasoulis and Isbister, 2017), which can be respectively associated with enzymatic and non-enzymatic bioactivities (Kang et al., 2011). Several toxins and enzymes exhibit species-specific properties, including defensins, waglerin, maticotoxin, and cystatins. In contrast, PLA2 is the most abundant protein family detected in snake venoms and is present in nearly all snake species (Tasoulis and Isbister, 2023). The PLA2s family is followed in prevalence by the three-finger toxins (3FTxs), a family of non-enzymatic toxins named as such due to the three loops formed by the peptide chain constrained by a conserved disulfide-bond pattern. Beyond these general considerations, it is important to keep in mind that the composition of snake venom is highly species-dependent. It is also influenced by the gender, age, geographic area, and feeding habits of the snake (Gopal et al., 2023). For example, elapid venoms consist mainly of PLA2s and 3FTxs. In contrast, viper venoms are mostly devoid of 3FTxs and contain more snake venom metalloproteinases, PLA2s, and snake venom serine proteases. Crotal venoms also lack 3FTxs, except for Atropoides nummifer (Tasoulis and Isbister, 2017).

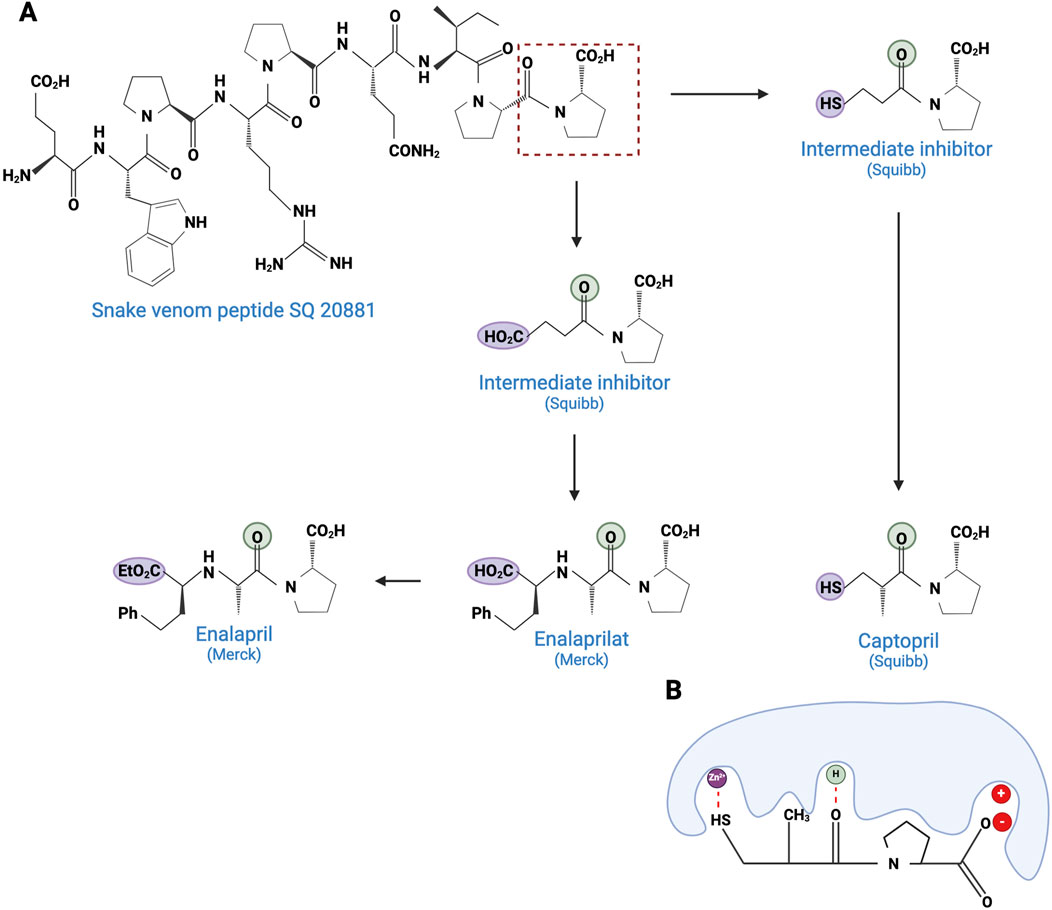

As early as 1981, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first venom-based treatment, a toxin isolated from the venom of the Brazilian pit viper, Bothrops jararaca (see Figure 2). Captopril (Capoten®) is a derivative of bradykinin potentiating peptides (BPPs), which lower blood pressure and reduce cardiac hypertrophy (Kini and Koh, 2020). BPPs, which belong to the natriuretic peptide family, inactivate bradykinin and catalyze the conversion of Angiotensin I to the vasoconstrictor Angiotensin II, by inhibiting the proteolytic Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) (Ferreira et al., 1970). Captopril mimics the BPP Pro-Ala-Trp triad, the recognition motif for ACE, and binds strongly to the enzyme’s active site (Ki = 1.7 nM) (Cushman and Ondetti, 1991). Captopril is hydrophilic and has a low molecular weight (Stepensky, 2018). However, its main disadvantage is the presence of a thiol group, which has been reported to cause side effects, such as skin rash and loss of taste. To circumvent this drawback, this reactive thiol has been replaced by a carboxylate function in the first step, resulting in a new molecule called enalaprilat. This replacement induced a lack of oral bioavailability, but replacing the carboxylate with an ethylic ester greatly improved it, resulting in enalapril (Patchett, 1984). Based on these initial developments, many drugs have been commercialized (lisinopril, quinapril, ramipril, etc.) (Acharya et al., 2003).

Figure 2. Development of captopril and next ACE inhibitors. (A) The natural peptide SQ 20881 (sequence EWPRPQIPP), discovered in Bothrops jararaca venom, is an inhibitor of ACE, inducing a drop in blood pressure. Squibb company synthetized a derivative which led, after optimization, to the captopril (1981). Because of the side effects of the thiol group, Merck replaced the latter with a carboxylate, resulting in the enalaprilat molecule (1985). However, as this modification resulted in the loss of oral bioavailability, the esterification of the enalaprilat was considered by Merck to solve the problem successfully and created the enalapril (1985). The conserved zinc binder is shown in purple. The H-bond acceptor is shown in green. (B) Interaction between captopril and ACE. By preventing the binding of the inert Angiotensin I to ACE, captopril inhibits the formation of Angiotensin II. Created with BioRender.com (2024).

Snake toxins and enzymes have also been described as potent antithrombotic drugs. For instance, echistatin (49 residues) from Echis carinatus venom and barbourin (74 residues) from Sistrurus miliarius belong to the disintegrin family, due to their potency to bind to integrins. Integrins αIIbβ3 are membrane receptors found on the surface of blood platelets. These receptors play a critical role in platelet aggregation (Casewell et al., 2013). In arterial thrombosis, rupture of the atherosclerotic plaque triggers platelet adhesion and aggregation, leading to clot formation in the arteries, obstructing blood flow to the brain and heart. Ligands for integrins, such as fibronectin, fibrinogen, and von Willebrand factor, interact in the final step of platelet aggregation, via a common recognition motif: a tripeptide sequence RGD (Arg, Gly, Glu) (Lebreton et al., 2016). This motif is commonly found in many PII-type SVMPs. It is unsurprisingly present in echistatin, and a similar sequence, KGD (Lys, Gly, Gluc), is also found in the barbourin. The advantage of the KGD sequence is that it does not block the adhesive functions of other RGD-dependent integrins, and therefore specifically inhibits platelet-dependent thrombus formation. Echistatin and barbourin have led to the development of two αIIbβ3 inhibitors, called tirofiban (Aggrastat®) and eptifibatide (Integrilin®), respectively, both of which were approved by the FDA in 1998 (Bledzka et al., 2013).

Another target of snake toxins is fibrinogen for anticoagulation purposes (Kini, 2006). For example, consider batroxobin, a 231-residue serine protease isolated from Bothrops moojeni venom. Batroxobin is a snake venom thrombin-like serine protease (svTLEs) that catalyzes the cleavage of the Arg16-Gly17 bond of the Aα chain of fibrinogen. By catalyzing this cleavage, it reduces plasma levels of fibrinogen, making clots more fragile and easier to dissolve (Vu et al., 2013). The advantage of this substitute over the well-known thrombin is double as it is more stable and not inhibited by heparin and hirudin (Funk et al., 1971). Treatment with Defibrase®, the drug derived from batroxobin and marketed in China and Japan, is used in ischemia caused by vascular occlusive disease, peripheral and microcirculatory dysfunction, and acute cerebral infarction (D'Amelio et al., 2021).

In the venom of the lancehead pit viper, Bothrops atrox, an enzymatic system has been discovered and demonstrated a powerful anti-hemorrhagic activity. This system, composed of batroxobin and a thromboplastin-like enzyme, has been derived into a pharmaceutical specialty called Reptilase®, which plays the role of haemocoagulase (Oliveira et al., 2022). The thromboplastin-like enzyme is a metalloprotein that activates Factor X to fXa, which converts prothrombin into thrombin. Combining the two activities, forming haemocoagulase, accelerates the hemostasis process, reducing bleeding and clotting times (Pentapharm).

The sixth drug based on a snake venom toxin is α-cobrotoxin (cobratide), purified from the venom of Naja naja atra, a cobra found in China. α-Cobrotoxin is a 3FTx α-neurotoxin, known to act selectively and with high affinity on muscle type α1 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). α-Cobrotoxin exhibits analgesic activity without opiate dependence and can therefore substitute for morphine (Gazerani and Cairns, 2014).

Other snake toxins are currently under development in the pharmaceutical field, to play a role in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases as antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents, and potentially even in the treatment of certain types of cancer (Kini and Koh, 2020; da Rocha et al., 2023).

As noted above, some drugs have already been developed as antiplatelet agents (tirofiban and eptifibatide). Still, many more toxins with similar activities are being discovered, reinforcing the great potential of toxins used as antiplatelet drugs. Like the drugs already on the market, some 3FTxs share the same RGD motif, which is a key for binding to platelet receptors. This is the case of dendroaspin (also known as mambin) (McDowell et al., 1992), S5C1 (Joubert and Taljaard, 1979), both isolated from the venom of Dendroaspis jamesoni kaimosae and thrombostatin from Dendroaspis angusticeps (Prieto et al., 2002). They possess the RGD motif in loop III (see Table 1). Dendroaspin targets the most abundant platelet integrin αIIbβ3 and thus prevents the binding of fibrinogen. When the RGD motif is mutated in RYD or RCD, the binding becomes selective for β1 and β3 integrins. Toxin binding inhibits ADP-induced platelet aggregation (Wattam et al., 2001). Another 3FTx, γ-bungarotoxin, isolated from Bungarus multicinctus, also shares the RGD motif. In γ-bungarotoxin, the motif is located in loop II, which is less accessible and induces a lower activity for the receptor than in loop III (IC50 = 34 µM) (Shiu et al., 2004). All these 3FTxs exhibit anticoagulant properties, making them interesting as potential antithrombotic agents. Other 3FTxs present anticoagulant potential. Hemetexin AB, exactin, and ringhalexin, all from the venom of Hemachatus haemachatus, target specific coagulation factors or complexes with inhibitory activity (Banerjee et al., 2005; Barnwal et al., 2016; Girish and Kini, 2016). The disadvantage of exactin and ringhalexin for therapeutic use is that they are also slightly neurotoxic. However, their high selectivity would allow the development of interesting molecular probes or diagnostic tools (Kini and Koh, 2020).

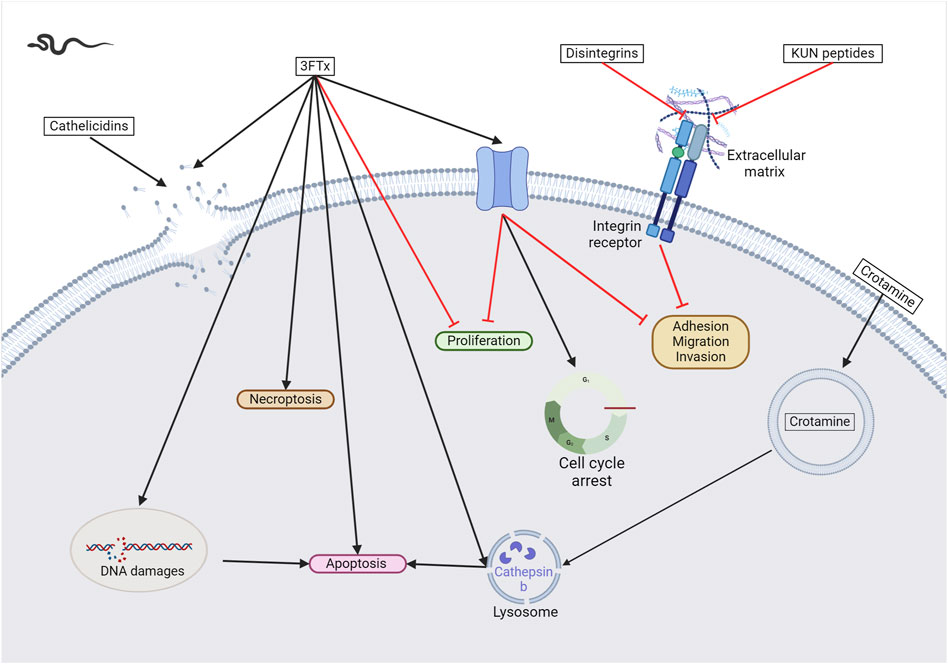

Snake toxins also present an interest in the cancer field (see Figure 3). Indeed, some 3FTxs are strongly cytotoxic. In that context, cytotoxins have been the focus of numerous studies investigating various cancer cell types. For instance, sumaCTX, a cytotoxin extracted from the venom of Naja sumatrana, has received much attention from the community due to its cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Teoh and Yap, 2020). It induces membrane hyperpolarization and apoptosis via activation of the two caspases 3 and 7. Changes in the secretome of cells treated with high doses of sumaCTX were later observed (Hiu and Yap, 2021). Most of the expressed proteins were involved in carbon metabolism, immune response, and necroptosis. Naja sumatrana cytotoxin was also tested on two types of cancer cells, lung adenocarcinoma and prostate cancer (Chong et al., 2020). The results showed significant differences in cellular behavior, with an increase in late apoptotic and necrotic cells compared to untreated cells. However, the specific mechanisms involved remain unclear.

Figure 3. Snake venom toxins as potential anticancer agents. In various cancer cell lines, 3FTx have been demonstrated to have a lytic activity by disrupting cell membranes, inducing DNA damage, and/or the release of lysosomal cathepsin B that further leads to apoptosis, to induce necroptosis and/or to stop cell proliferation (Abdel-Ghani et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2019). Moreover, these toxins can also target ion channels, halting cancer cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and invasion, and inducing cell cycle arrest (Bychkov et al., 2021; Sudarikova et al., 2022). Cathelicidins are mainly described to form pores in cancer cell membranes ((Wang et al., 2013). Finally, disintegrins and Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors (KUN) peptides primarily affect the interactions between the extracellular matrix and cell membrane receptors, reducing cancer cell adhesion, migration, and invasion (Zhou et al., 2000a; Brown et al., 2008; Minea et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2021; Bhattacharya et al., 2023). Created with BioRender.com (2024).

Other cytotoxins in snake venoms are being extensively studied for their potential anticancer properties. The NKCT1 (purified Naja kaouthia protein toxin) was first extracted from Naja kaouthia venom in 2010 and showed cardiotoxic and cytotoxic properties against two leukemia cell lines (U937 and K561) (Debnath et al., 2010). Recently, a growing interest in conjugating this toxin with gold nanoparticles to target leukemia, glioblastoma, hepatocarcinoma, and breast cancer cells emerged (Bhowmik et al., 2013; Bhowmik and Gomes, 2017; Bhowmik et al., 2017). A synergistic effect of administering gold nanoparticle-NKCT1 conjugates was then observed. Indeed, while the conjugation induces apoptosis of cancer cells through caspase activation, it also reduces cytotoxicity against non-cancerous cells. Treatment with GNP-NKCT1 induces autophagy in leukemia cells (Bhowmik and Gomes, 2016). In breast cancer cells, it induces cell cycle arrest by inactivating CDK4 and reduces migration and invasion by inhibiting MMP-9 (Bhowmik and Gomes, 2017).

Naja atra cytotoxins (CTX) have also been studied in various cancer cell types. In leukemia cells, CTX1 treatment led to the initiation of necroptosis and the activation of the FasL/Fas-mediated death signaling pathway (Liu et al., 2019; Chiou et al., 2021). Notably, the venom of Naja atra contains numerous CTX isoforms, of which only CTX1 can induce this type of cell death whereas CTX3 induces autophagy-dependent apoptosis in leukemia cells (Chiou et al., 2019). This result suggests that different mechanisms may mediate CTX cytotoxicity. In addition, CTX can cause the loss of the lysosomal membrane integrity in breast cancer cells, leading to the release of lysosomal enzymes, including cathepsin B, which induces necrosis or apoptosis (Wu et al., 2013). Intramuscular administration of CTX1 in mice currently results in skeletal muscle necrosis, making its clinical use impossible, without sequence optimization or improved delivery (Ownby et al., 1993).

Another cobra species, Naja nubiae, caught the scientific community’s attention by providing the cytotoxin nubein 6.8 (Abdel-Ghani et al., 2019). This peptide shows similarities with other cytotoxins identified in different cobra species and shares the first 6 N-terminal amino acids. In addition, it shows cytotoxic effects against several types of cancer cells, including melanoma and ovarian carcinoma. Cytotoxin nubein 6.8 has been shown to cause DNA damage leading to apoptosis. However, the precise mechanisms underlying this cytotoxicity have not been fully elucidated yet.

NN-32 is a peptide isolated from the cobra Naja naja that shows strong homology to other cytotoxins from Naja species (Das et al., 2011). When treated with NN-32, leukemia, and breast cancer cells show a reduction in cell viability and proliferation, with a concomitant decrease in lysosomal activity and induction of apoptosis (Das et al., 2013; Attarde and Pandit, 2017). More recently, nanogold particles have been conjugated with the NN-32 peptide, resulting in GNP-NN-32. The goal of developing GNP-NN-32 was the same as for NKCT1, i.e., to increase the selective cytotoxicity against breast cancer cells. The results showed lower IC50 values (Attarde and Pandit, 2020).

Dendroaspis polylepis polylepis, the famous Black mamba, produces mambalgins that inhibit acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs). ASICs are voltage-insensitive receptors that are activated by extracellular protons. By selectively and potently inhibiting the ASIC1a and ASIC1b subtypes, with an IC50 between 11 and 300 nM, mambalgin-1 showed a potent analgesic effect, while mambalgin-2 is a powerful and reversible inhibitor of ASIC1a (Diochot et al., 2012). In the context of cancer, this channel has recently been described to be overexpressed in breast, melanoma, lung, and liver cancers (Jin et al., 2015; Bychkov et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Sudarikova et al., 2022). The mambalgin-2 application to leukemia cells reduces their growth and induces cell cycle arrest (Bychkov et al., 2020). In glioma cells, the constant cation current required for cell growth and migration was shown to be mediated by ASIC1a (Rooj et al., 2012). Their treatment with mambalgin-2 induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Acidification, which promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasiveness, is facilitated by this channel in melanoma (Bychkov et al., 2021). Treatment with mambalgin-2 reduces this phenotype. The same conclusion has recently been drawn for lung adenocarcinoma (Sudarikova et al., 2022).

Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors (KUN) are small proteins that contain a Kunitz domain. These domains are approximately 50–60 amino acid residues with alpha and beta-fold structures stabilized by three conserved disulfide bridges and inhibit the enzymatic activity of serine proteases (Munawar et al., 2018). KUNs have also been investigated for their promising anticancer activity. Vipegrin, extracted from Daboia russelli (Russell’s viper) venom, is cytotoxic against breast cancer cells while showing no significant effect on non-cancerous cells (Bhattacharya et al., 2023). This property suggests that vipegrin may follow a specific pathway for killing cancer cells, but unfortunately, it has not been identified to date. Another example is PIVL, a peptide derived from the venom of Macrovipera lebetina, which possesses an anti-tumor activity by primarily blocking integrin receptor function, resulting in reduced adhesion of cancer cells. This suggests that PIVL’s anticancer activity is not related to cell viability but affects cancer cell migration and invasion (Morjen et al., 2013).

Crotoxin, derived from the venom of Crotalus durissus terrificus, is a complex of two subunits, namely phospholipase A2 (crotactin) and a non-enzymatic subunit (crotapotin) that enhances the activity of the first subunit (Faure et al., 1993). This β-neurotoxin activates both autophagic and apoptotic pathways in leukemia, breast, and lung cancer cells (Yan et al., 2006; Yan et al., 2007; Han et al., 2014). Crotoxin has also been shown to enhance the efficacy of gefitinib in lung adenocarcinoma cells (Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). Gefitinib is an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which is used to treat lung cancer. One hypothesis explaining the synergistic effect is based on the observation that crotoxin modulates EGFR signaling (Donato et al., 1996). Recent studies show that crotoxin also exhibits cytotoxic effects against several cancer cell types, including esophageal, brain, cervical, and pancreatic cancer (Muller et al., 2018). Further evidence shows that crotoxin may have an anti-tumor effect on estrogen-positive (ER+) breast cancer by decreasing the phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 protein, with the antiproliferative effect then being related to the inhibition of the MAPK pathway (Almeida et al., 2021). Crotoxin treatment (10 μg/kg) did not induce any changes in body weight or biochemical parameters in mice (He et al., 2013; da Rocha et al., 2023). However, it was still effective in reducing tumor growth in transplanted esophageal and oral cancer mice. A phase 1 clinical trial was initiated to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of the toxin in patients with advanced breast cancer (Cura et al., 2002), and an open-label phase 1 clinical trial in patients with advanced cancer using intravenous administration was more recently initiated in 2018 and has shown promising results for the efficacy of the toxin in cancer treatment (see Table 3).

The Caspian cobra, Naja naja oxiana, is considered the most venomous species among the Naja sp. This cobra secretes a specific cytotoxin called oxineur (Sadat et al., 2023). Oxineur shows cytotoxic activity against colon cancer cells while not affecting normal cells. However, more extensive testing is required to evaluate the effects of its administration on animals.

Disintegrins are components of snake venoms that interact with integrins through the RGD domain (see Table 2). Because integrins are involved in angiogenesis and metastasis, integrin ligands are potentially potent anticancer reagents. For instance, obtustatin, a disintegrin inhibitor of the α1β1 integrin isolated from the venom of Macrovipera lebetina obtusa venom, inhibits melanoma growth in mice (Brown et al., 2008). The inhibition mechanisms are mainly due to obtustatin’s anti-angiogenic activity, which activates apoptosis in endothelial cells. Obtustatin also reduces tumor size in sarcoma-bearing mice, via angiogenesis inhibition (Ghazaryan et al., 2015; Ghazaryan et al., 2019). Contortrostatin, a disintegrin homodimer derived from the venom of Agkistrodon contortrix contortrix, is another potent integrin inhibitor, that is selective for β1, β3, and β5 integrins (Zhou et al., 2000a). Contortrostatin, although non-cytotoxic, inhibits the adhesion and invasion of breast cancer cells in vitro (Zhou et al., 2000b). This anti-invasive effect was attributed to the blockage of αvβ3, an integrin highly expressed in metastatic cells. Interestingly, migration and invasion are also reduced in prostate cancer. However, this effect cannot be attributed to αvβ3 inhibition as this prostate cancer cell line (PC-3) does not express this integrin but αvβ5 may be an alternative target (Lin et al., 2010). Furthermore, encapsulation of contortrostatin in liposomes prevents potential clinical side effects such as platelet binding and immunogenicity (Swenson et al., 2004). These findings are promising for the long-term use of the compound in clinical trials. According to a recent review published in 2020, the next step will be to submit an investigational new drug application to initiate a phase 1 clinical trial (Schonthal et al., 2020). In addition, Zhang and co-workers have recently developed a recombinant fusion protein known as IL-24-CN, a tumor suppressor protein (Zhang et al., 2021). Overexpression of IL-24 can inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. The study successfully demonstrated the growth-suppressive and apoptosis-inducing effects of IL-24-CN on melanoma cells.

Vicrostatin is a disintegrin produced by recombination of the C-terminal tail of echistatin with contortrostatin (Minea et al., 2010). Despite its immunogenicity, this construct not only retains the native binding properties of contortrostatin but also shows an innovative binding to the integrin α5β1. Intravenous administration of vicrostatin in mice showed no side effects. As previously demonstrated for other disintegrins, vicrostatin can inhibit angiogenesis, thereby reducing both tumor vascular density and metastasis (Minea et al., 2010). In the context of glioma treatment, brachytherapy is an emerging method in which radioactive material is delivered to the tumor to minimize damage to healthy tissue. Radioiodinated vicrostatin (131I-VCN) has been developed to treat glioma, a tumor type expressing high levels of integrins. 131I-VCN has been successfully tested in glioma animal models and has been shown to prolong survival (Swenson et al., 2018). Moreover, Jadvar and colleagues have recently developed a 64Cu-labeled vicrostatin probe for PET imaging of tumor angiogenesis in prostate cancer, suggesting that venom components can be used as both diagnostic and therapeutic tools (Jadvar et al., 2019). Other disintegrins found in snake venom are also listed in Table 4.

Cathelicidins are a class of antimicrobial peptides found in insects, fish, amphibians, and mammals. They are effective against a wide range of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa (Wang et al., 2013). Interestingly, these peptides have also shown cytotoxic activity against cancer cells. More specifically, BF-30 is a cathelicidin-like polypeptide, extracted from Bungarus fasciatus. BF30 inhibits the proliferation of metastatic melanoma cells without affecting normal cells (Wang et al., 2013). In vivo, this compound effectively reduces cell proliferation and has low toxicity in mice. Furthermore, BF30 reduces angiogenesis by decreasing VEGF gene expression levels. BF-30 derivatives have been developed to improve the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters of BF-30 (Qi et al., 2020).

In the venom of Crotalus durissus terrificus, crotamine is a β-defensin that possesses cell-penetrating properties by efficiently translocating into cells (Pereira et al., 2011). Crotamine exhibits targeted cytotoxicity against melanoma cell lines, with a specificity of 5 times higher than normal cells. Interestingly, no toxicity was observed in treated animals. The precise mechanisms underlying the cytotoxic effects of crotamine are not well understood. One hypothesis is that crotamine is endocytosed and transported to the lysosome, resulting in an increase in lysosomal content and the leakage of content into the cytosol. Furthermore, lysosomes have been shown to trigger intracellular Ca2+ transients and affect mitochondrial membrane potential (Nascimento et al., 2012). In addition, crotamine has been found to accumulate in tumor cells, suggesting that it could act as a diagnostic tool like vicrostatin (Kerkis et al., 2014). To facilitate the advancement of crotamine in clinical trials, an oral administration of the molecule was assessed in animals (Campeiro et al., 2018). Small changes in glucose clearance, total cholesterol, triglyceride, and lipoprotein levels were measured but were considered harmless. No other adverse toxic effects were observed. Synthetic crotamine has since been produced with similar properties to the native peptide, allowing for improved analogs with fewer potential side effects and better properties (de Carvalho Porta et al., 2020). This provides an opportunity for further research into developing new applications for these analogs.

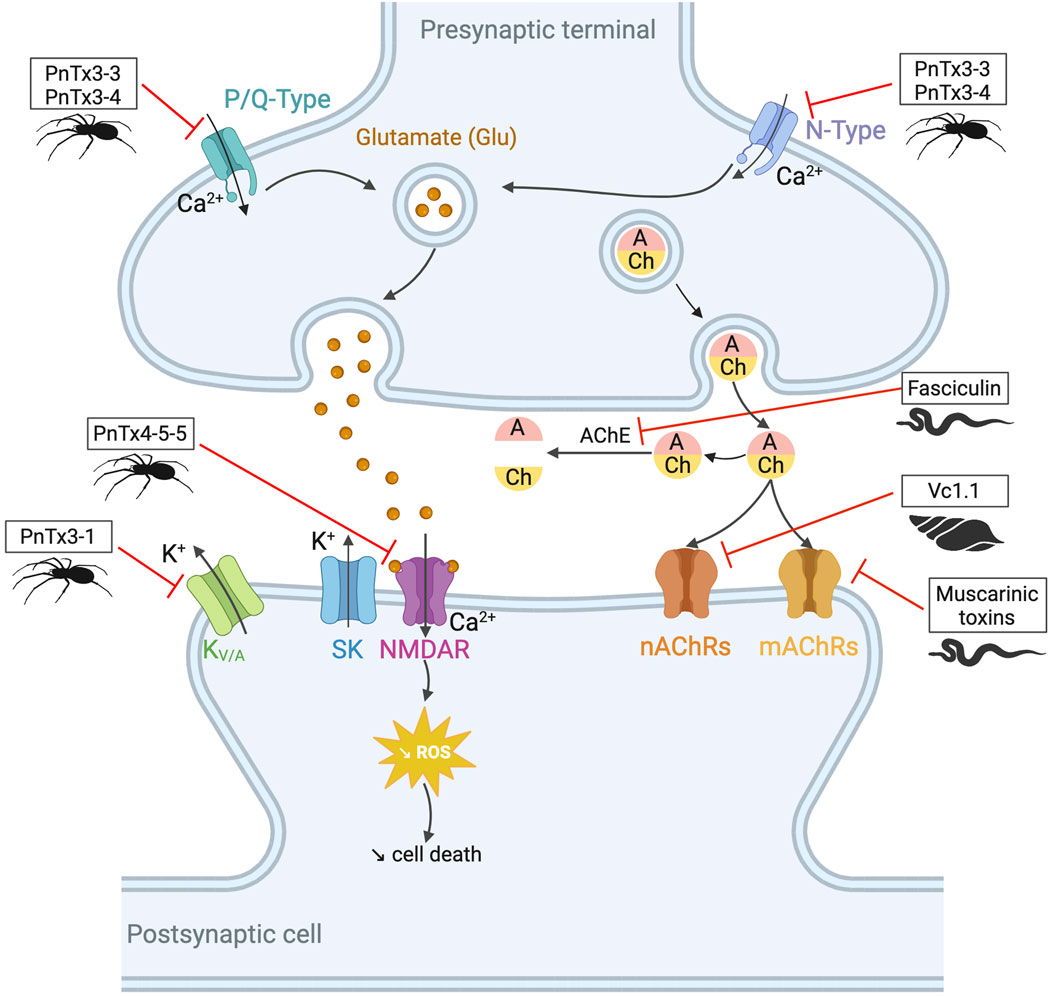

Snake venom contains other toxins that may have potential in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s (see Figure 4). For instance, interesting bioactivity in the context of Alzheimer’s disease comes from fasciculin, a 61-residue 3FTx isolated from Dendroaspis angusticeps (Waqar and Batool, 2015). By inhibiting the acetylcholinesterase (AChE), fasciculin restores normal levels of acetylcholine (Harel et al., 1995). Since a reduction in this neurotransmitter leads to cognitive impairment, particularly the memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Winblad and Jelic, 2004), the effect of fasciculin may be beneficial. In parallel, RVV-V, a peptide discovered in the venom of Daboia russelli russelli is a procoagulant enzyme activator of factor V that destabilizes β-amyloid (Aβ) aggregates. Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by insoluble plaques composed of Aβ peptide fibrils. Destabilizing these aggregates would help prevent amyloidosis (Bhattacharjee and Bhattacharyya, 2013).

Figure 4. Potential toxin inhibitors involved in neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and chronic pain. Vc1.1 has antagonistic activity on neuronal nAChRs involved in neuropathic pain (Sandall et al., 2003; Bordon et al., 2020). Inhibition of AChE by fasciculin helps to counteract the acetylcholine deficiency seen in disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. Blocking KV/A channels with PnTx3-1 reduces memory deficits (Gomes et al., 2013). PnTx4-5-5 has a neuroprotective effect by blocking the NMDA receptors by reducing glutamate release (Silva et al., 2016). N- and P/Q-type channels also release glutamate by controlling the calcium flux. PnTx3-3 and PnTx3-4 have inhibitory activity on these two channels (Vieira et al., 2005; Dalmolin et al., 2011; Souza et al., 2012; Pedron et al., 2021). The reduction of glutamate prevents ROS formation. Muscarinic toxins can regulate mAChRs when they are dysfunctional. Adapted from “NMDAR-dependent long-term depression (LTD),” Created with BioRender.com (2023).

Ionotropic γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors are massively present in the central nervous system. They modulate Cl− conductance across the cell membrane and thus shape synaptic transmission (Sieghart, 2006). These receptors have been implicated in many diseases including epilepsy, schizophrenia, and chronic pain. Some snake toxins (α-bungarotoxin and α-cobratoxin) show activity for GABAA receptors, but unfortunately also act on nAChRs avoiding any easy use of these toxins for medical purposes.

The venom of the Eastern green mamba, Dendroaspis angusticeps, but also the black mamba Dendroaspis polylepis polylepis (black mamba), contains muscarinic toxins that selectively target muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs; M1 – M5). These toxins exhibit high affinity, selectivity, and low reversibility for their receptors (for a table with the inhibition constants of each toxin for each channel subtype, see the review by Servent et al. (2011)). M1, M4, and M5 are mainly found in the central nervous system, whereas M2 and M3 are found in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Muscarinic toxins offer the possibility to regulate dysfunctional receptors and thus provide solutions for neurological diseases as well as diseases related to the peripheral system, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, incontinence, overactive bladder, etc. (Servent et al., 2011). The Eastern green mamba venom is a rich source of drug candidates as another toxin, called mambaquaretin-1 (MQ-1) shows high affinity and selectivity for the vasopressin type 2 receptor (V2R), with a Ki = 2.81 nM (Ciolek et al., 2017). Interestingly, MQ-1 does not interact with the other subtypes of the vasopressin receptors (V1a, V1b) and with the oxytocin receptor OT (Ki > 1 mM), making it a true molecular tool for the specific study of the V2R. From a therapeutic point of view, this Kunitz-type venom protein has the potential to treat polycystic kidney disease (PKDs), a genetic disorder characterized by the formation of numerous cysts in the kidneys, leading to end-stage renal failure. Selective inhibition of the V2 receptor reduces cAMP levels. This molecule stimulates chloride-induced cell proliferation and fluid secretion into the cyst lumen in polycystic kidneys. Since the discovery of MQ-1, eight other mambaquaretin-like toxins have been discovered in mamba’s venoms. All of them are antagonists of V2R, interacting with the receptor with nanomolar affinity (Droctove et al., 2022).

Arthropods are the largest group of animals on Earth, comprising approximately 80% of the 1.5 million described animal species (according to the IUCN Red List in 2023). This phylum includes insects, arachnids, crustaceans, and myriapods, such as bees, scorpions, and spiders (Soltan-Alinejad et al., 2022).

Scorpions have evolved over 400 million years to produce powerful toxins that affect various targets, especially localized in the nervous system (Estrada-Gomez et al., 2017). Scorpion venoms include peptides, enzymes, and non-protein compounds, such as salts, free amino acids, lipids, nucleotides, and neurotransmitters (Almaaytah and Albalas, 2014). Peptides are divided into two main classes according to their structural and functional properties: disulfide-bridged peptides (DBPs), and non-disulfide-bridged peptides (NDBPs). Five families comprise the DBPs, sodium channel toxins (NaTx), potassium channel toxins (KTx), chloride channel toxins (ClTx), calcium channel toxins (CaTx), and transient receptor potential channel toxins (TRPTx), all described in Table 5. Among the NDBPs, short antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and bradykinin potentiating peptides (BPPs) are commonly found (Hmed et al., 2013). As seen in the case of the snakes, scorpions produce L-amino acid oxidases (LAAOs), serine proteases, hyaluronidases, metalloproteinases, nucleotidases, and phospholipases A2 (Soltan-Alinejad et al., 2022). Although NDBPs do not have specific ion channel targets, they are increasingly studied for their potential as antimicrobial, antiviral, and anticancer agents (Almaaytah and Albalas, 2014).

Overall, scorpion DBP toxins primarily target ion channels (ICs). Because ICs modulate essential functions in the body, their dysfunction can lead to the development of neurological disorders such as chronic pain, depression, autoimmune diseases, epilepsy, and cancer, as well as metabolic diseases such as diabetes. These dysfunctions, known as channelopathies, can be caused by the deregulation of channel opening/closing, changes in current amplitude, or problems regulating protein activity (Mendes et al., 2023). Neurotoxins of arthropods targeting these channels with remarkable specificity and potency constitute true molecular scalpels for studying IC distributions, functions, structures, and real candidates for tomorrow’s drugs. This review section is divided into five parts corresponding to the sodium, potassium, chloride, and calcium channels targeted, as well as other potential activities of scorpion venom.

Voltage-gated sodium channels (Nav) play an essential role in pain transmission, especially with Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 subtypes, the most expressed in sensory neurons. Scorpion-derived peptides exert analgesic effects by regulating various Nav channels, especially Nav1.1, Nav1.6, Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 (Cummins et al., 2007; Eagles et al., 2022). Many NaTxs possess analgesic potency. Among them, BmK AS, BmK AS1, and BmK IT2 act on Nav1.8, Nav1.9, and Nav1.3 by reducing the peak Na+ conductance in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons. Others like BmKM9, BmK AGAP, and AGP-SYPU1 inhibit the inactivation of the activated Nav1.4, Nav1.5, and Nav1.7. All these peptides are derived from Buthus martensii Karsch. BmK AGAP alleviates inflammatory pain by inhibiting the expression of peripheral and spinal mitogen-activated protein kinases and induces long-lasting analgesia by blocking TRPV1 currents when injected with lidocaine. It is considered a promising analgesic due to its multitarget capabilities (Kampo et al., 2021). Despite the discovery of numerous potent and selective Nav channel inhibitors, which are pharmacologically interesting, very few of these inhibitors have resulted in effective pain relief in preclinical models or human clinical trials (Eagles et al., 2022).

Potassium channels are divided into four groups according to their activation mode and the number of transmembrane segments (TM). Inwardly rectifying K+ (KIR) channels have 2 TM and two pore domains, whereas potassium channels (K2P) consist of 4 TM and two pores, KCa are calcium-activated potassium channels with 6 or 7 TM, and KV are voltage-gated potassium channels with 6 TM (Wulff et al., 2009). KV channels have been implicated in several diseases including cancer, autoimmune, neurological, and cardiovascular diseases.

In 1984, patch-clamp studies highlighted the role of the voltage-gated KV channels in the activation of thymus-derived lymphocytes (T cells). Therefore, ion channels are involved in the immune response (Matteson and Deutsch, 1984). KV1.3 (KCNA3) and calcium-activated KCa3.1 channels are primarily responsible for K+ efflux and are important therapeutic targets in various autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and type-1 diabetes (Chandy and Norton, 2017). Charydbotoxin (ChTX), identified from the venom of Leiurus quinquestriatus, is a blocker of KV channels (Kd = 3 nM) but also of intermediate conductance calcium-activated channels (IKCa1) (Kd = 5 nM). Other inhibitors of the KV1.3 channel are margatoxin (MgTX), from Centruroides margaritatus, and HsTX1 from Heterometrus spinnifer venom. They are both potent blockers in the picomolar range of KV1.3. HsTX1 is a potentially attractive candidate for the treatment of KV1.3-related diseases due to its selectivity (IC50(KV1.3) = 29 ± 3 pM; IC50(KV1.1) = 11,330 ± 1,329 pM). To further improve selectivity, analogs of this toxin (HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14Abu]) have been developed. The arginine at position 14 is replaced by a neutral residue to prevent ionic interaction with KV1.1. This toxin binds to the E353 amino acid of this potassium channel but does not bind to KV1.3. Thus, the affinity for KV1.1 is reduced without affecting the affinity for KV1.3. The selectivity of HsTX1[R14A] is then more than 2,000-fold for KV1.3 over KV1.1 (Rashid et al., 2014). Other synthetic analogs of scorpion toxins show potent activity against KV1.3. Among them, OSK-1[E16K, K20D] has a five-fold higher IC50 than the native peptide OSK-1 (α-KTx3.7) from Orthochirus scrobiculosus: 3 pM versus 14 pM, respectively (Mouhat et al., 2005). Other peptides are listed in Table 6.

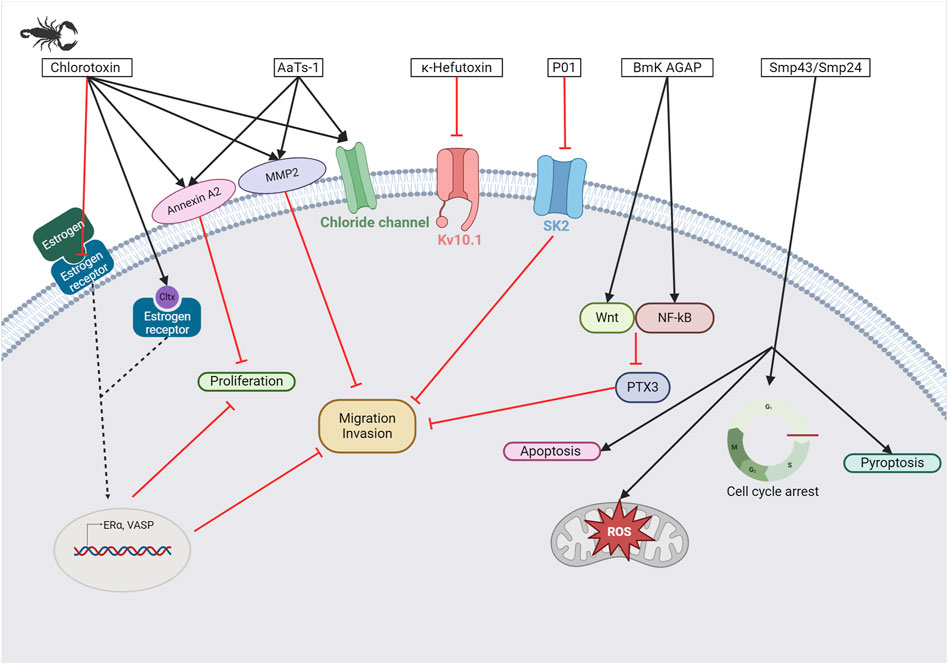

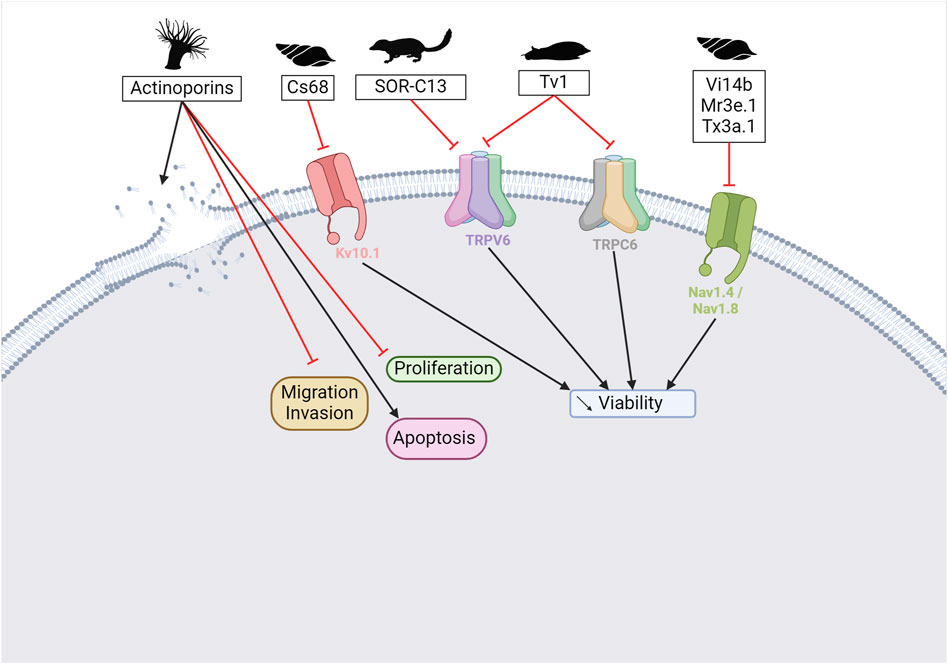

Scorpion venom also contains several peptides with anticancer activity (see Figure 5). For instance, κ-hefutoxin-1, a peptide isolated from the venom of Heterometrus fulvipes, is a potassium channel inhibitor. Specifically, it can inhibit the oncogenic KV10.1 channel, which is overexpressed in several types of cancer (Pardo et al., 1999; Moreels et al., 2017). However, the effects of this peptide on cancer cells remain to be determined. Interestingly, P01-toxin, extracted and purified from the venom of Androctonus australis is a potent inhibitor of the SK2 potassium channel (Mlayah-Bellalouna et al., 2023). While the peptide was shown to reduce cell viability, adhesion, and migration in glioma cells, no such effects were observed in breast and colon cancer cells. These results suggest that SK2 channels are involved in the formation of glioma tumors. Another peptide toxin derived from the same species, AaTs-1, shares more than 80% homology with chlorotoxin (Aissaoui-Zid et al., 2021). Like chlorotoxin, AaTs-1 binds to chloride channels, MMP-2, and annexin 2, leading to a reduction in glioma cell proliferation and migration. In terms of anticancer activity, the effects of Buthus martensii Karsh antitumor analgesic peptide (BmK AGAP) on breast cancer cells have been studied, revealing its ability to inhibit cancer cell stemness, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, and invasion (Kampo et al., 2019). The mechanisms underlying these effects have been investigated, and it has been found that the downregulation of PTX3 via NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling is critical.

Figure 5. Scorpion toxins as potential anticancer therapy. Chlorotoxin has four cellular targets: estrogen receptor (ERα), annexin A2, MMP2, and chloride channel. Overall, the binding of chlorotoxin to these targets leads to inhibiting cell proliferation and/or reducing cancer cell migration and invasion (Boltman et al., 2023). Binding to chloride channels can also help to visualize tumor sites in brain tumors. Sharing 80% of homology with chlorotoxin, AaTs-1 binds annexin A2, MMP2, and chloride channels (Aissaoui-Zid et al., 2021). κ-hefutoxin-1 is a KV10.1 inhibitor, a potassium channel known to be overexpressed in several cancer types (Pardo et al., 1999; Moreels et al., 2017). P01 is a potent SK2 channel inhibitor that leads to the inhibition of cancer cell migration and invasion (Mlayah-Bellalouna et al., 2023). BmK AGAP has been shown to reduce cancer cell migration and invasion by the downregulation of PTX3 via NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin (Kampo et al., 2019). Finally, Smp43 and Smp24 are two antimicrobial peptides that can trigger apoptosis, pyroptosis, an accumulation of reactive oxygen species, or a cell cycle arrest in cancer cells (Chai et al., 2021; Elrayess et al., 2021). Created with BioRender.com (2024).

ClTxs are divided into two subgroups. The vast majority have an inhibitory cystine knot (ICK) motif, characterized by two disulfide bonds pierced by a third to form a pseudoknot. The second motif, the disulfide-directed hairpin (DDH), would result from a simplification of the ICK motif to only two bonds (Smith et al., 2013). The best-known toxin targeting chloride channels is chlorotoxin, isolated from the venom of Leiurus quinquestriatus. Chlorotoxin can also bind to matrix metalloproteinase-2, annexin A2, estrogen receptor α, and neuropilin-1 receptor. This peptide has been extensively studied in the context of glioblastoma and neuroblastoma where those proteins are all involved in cell migration and invasion, as recently reviewed by Boltman and colleagues (Boltman et al., 2023). In addition, chlorotoxin has a wide range of applications, including tumor imaging and combination with other therapeutics or molecules as this peptide can cross the blood-brain barrier (Veiseh et al., 2007; Formicola et al., 2019; Vannini et al., 2021; Dardevet et al., 2022). Numerous clinical trials are underway to establish the safety and pharmacokinetic properties of BLZ-100, a chlorotoxin-based imaging agent containing indocyanine green as a fluorophore (Patil et al., 2019) (see Table 3). The efficacy of chlorotoxin in the treatment of other cancers has also been investigated. Efficacy against cervical cancer cells is significantly improved when coupled with a platinum complex (Graf et al., 2012). In breast cancer, chlorotoxin has the potential to inhibit cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by either directly binding to the estrogen receptor (ER) or by preventing estrogen binding to its receptor. This thereby inhibits the ER signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2019).

Because calcium channels are involved in pain pathways, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, seizures, migraine, and ataxia, they are promising and interesting targets (Zamponi, 2016). As scorpion venoms are a rich source of toxins that act on Ca2+ channels, they may have therapeutic potential. Such scorpion toxins include calcins, a family of cell-penetrating peptides composed of 33 residues (35 for hadrucalcin) and three disulfide bridges. They have an ICK motif and potently target Ryanodine receptors (RyRs), intracellular ion channels that regulate the Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic and sarcoplasmic reticulum, thereby triggering myocardial contraction (Vargas-Jaimes et al., 2017). Imperacalcin (formerly imperatoxin A), identified from the venom of Pandinus imperator, is the first member of the calcium-targeting toxins to bind to RyR1 with nanomolar affinities (Valdivia et al., 1992). Subsequently, maurocalcin, from the venom of Scorpio maurus palmatus, was isolated based on sequence similarity to imperacalcin (82% sequence identity). Both increase skeletal RyR (RyR1) activity but also have a nanomolar affinity for cardiac RyR (RyR2) (De Waard et al., 2020). Other toxins of interest are listed in Table 6.

CPP-Ts, isolated from Tityus serrulatus venom, is a cell-penetrating peptide, that crosses both cellular and nuclear membranes. This peptide increases the contractile frequency of cardiomyocytes by activating the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R), a ligand-gated Ca2+ release channel. This activation leads to a transient change in intracellular calcium levels. CPP-Ts can be internalized by cancer cells and not by normal cell lines, making it a potential intranuclear delivery tool to target cancer cells (Oliveira-Mendes et al., 2018).

Scorpion venom also contains antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which belong to the group of non-disulfide-bridged peptides (NDBPs) (Almaaytah and Albalas, 2014). Their role in venom and their molecular target remains to be elucidated. However, the antimicrobial peptides Smp43 and Smp24 from the Egyptian scorpion Scorpio maurus palmatus were studied in different cancer cell types including hepatocellular, non-small cell lung, and leukemia cancer cell lines. Smp43 exhibits antitumor properties in hepatocellular carcinoma by inducing apoptosis, autophagy, necrosis, and arresting cell cycle progression (Chai et al., 2021). In addition, both peptides stimulate pyroptosis, a regulated cell death mechanism that recruits the inflammasome, which subsequently activates caspases (Elrayess et al., 2021). These two peptides also induce a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, leading to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in lung and hepatocellular cancer cells (Guo et al., 2022; Nguyen T. et al., 2022; Deng et al., 2023). Interestingly, Smp43 only has minor effects on a lung fibroblast cell line, MRC-5 (Deng et al., 2023).

Scorpion peptides have also been investigated for the treatment of malaria. This disease, caused by Plasmodium falciparum infection, occurs in more than one hundred countries and can be fatal, especially in children (Murray et al., 2012). Scorpine, isolated from Pandinus imperator, shows activity in the ookinete and gamete stages of the development of the parasite Plasmodium berghei. Since the developmental stages of the two parasites are the same, scorpine could represent a promising model for malaria treatment (Conde et al., 2000). Lastly, some peptides with antimicrobial activities are also important antimalarial candidates, such as meucin-24, meucin-25, and hadrurin (Ortiz et al., 2015).

Spiders, like scorpions, have evolved over more than 400 million years. Although about 50,000 species have been described so far, the diversity is estimated to be more than 100,000 (Agnarsson et al., 2013; World Spider Catalog, 2023). Spider venoms consist of proteins, peptides, nucleotides, and small molecular weight organic molecules, such as organic acids, nucleotides, amino acids, amines

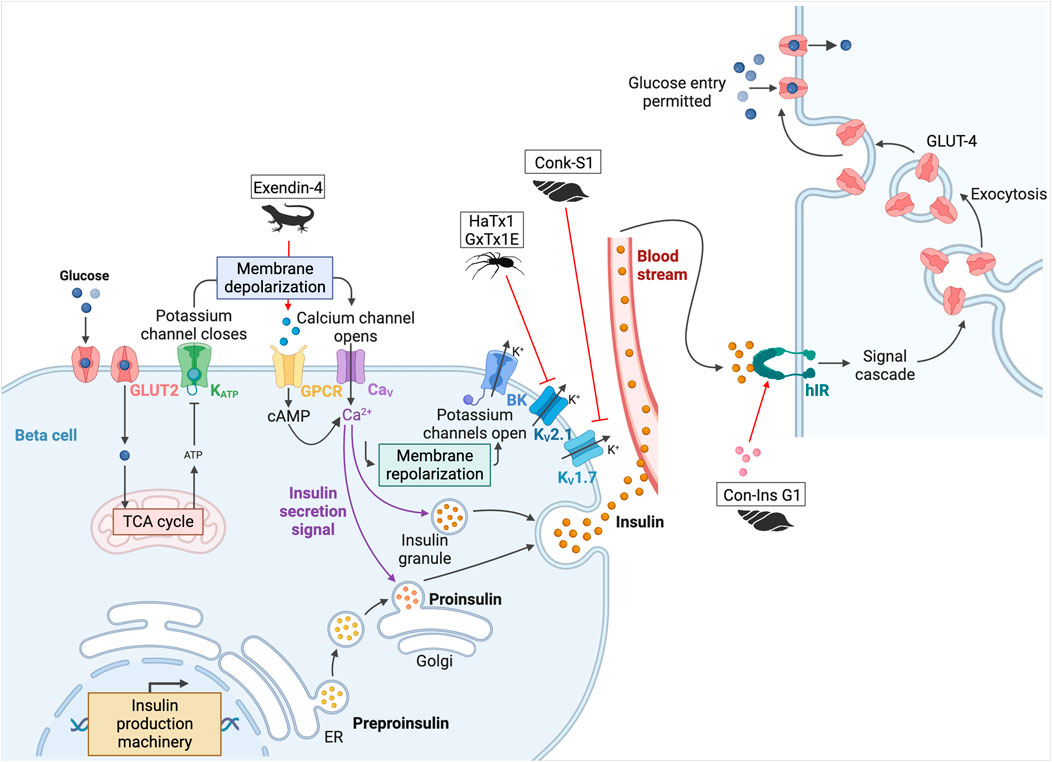

As mentioned above, arthropod venom contains toxins with activities on ion channels. These channels are involved in physiological mechanisms, including the regulation of insulin secretion by glucose. They allow membrane depolarization and trigger an action potential that induces the release of insulin granules. The channels involved in this process are ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels. Their closure leads to the depolarization of the cell, which opens voltage-dependent calcium (CaV) channels, triggering the action potential that allows insulin granules to be released from the pancreas (Ashcroft and Rorsman, 1989). This is followed by repolarization of the cell with activation of large conductance calcium-activated K+ (BK) and voltage-gated potassium (KV2.1 and KV1.7) channels (Herrington, 2007). κ-theraphotoxin-Gr1a (hanatoxin-1, HaTx1), a toxin with inhibitory activity on these KV2.1 channels, was isolated from the venom of the Chilean pink tarantula, Grammostola rosea (Swartz and MacKinnon, 1995). By blocking them, the HaTx1 increases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (see Figure 6) (Herrington et al., 2005). Unfortunately, this peptide, as well as guangxitoxin-1 (GxTx1E, κ-theraphotoxin-Pg1a), isolated from the venom of the Chinese tiger tarantula (Chilobrachys guangxiensis), also shows an affinity for other various channels, such as KV4.2 and CaV2.1 and KV2.2 and 4.3 respectively. This lack of selectivity prevents its use as a treatment (Herrington, 2007).

Figure 6. Potential toxins involved in the insulin pathway. Glucose is transported into pancreatic beta cells by facilitated diffusion through GLUT2 glucose transporters. Once inside the cell, glucose is converted to ATP by glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation. When the ATP/ADP ratio is high, K+ channels are inhibited, leading to cell membrane depolarization. Closure of the KATP channels leads to the depolarization of the cell, which opens the CaV channels and triggers the action potential that allows insulin granules to be released from the pancreas. This is followed by repolarization of the cell with activation of BK, KV2.1, and KV1.7. Once produced, insulin is delivered to target tissues, such as the liver, adipocytes, muscle, and brain. Insulin binds to hIR, initiating a phosphorylation cascade that ultimately leads to glucose uptake and storage in glycogen, thereby lowering blood glucose levels. HaTx1 and GxTx1E are two spider peptides, and Conk-S1 is a cone snail peptide that inhibits KV2.1 and KV1.7 respectively (Herrington et al., 2005; Herrington, 2007; Finol-Urdaneta et al., 2012). Inactivation of these channels leads to an increase in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Another cone snail toxin, Con-Ins G1 is an insulin-like peptide that can activate hIR (Xiong et al., 2020). Finally, the most famous one is exenatide-4, from the Gila monster, which led to the development of the drug exenatide (Byetta©) (Nadkarni et al., 2014). This peptide binds to the incretin hormone GLP-1 receptor. This GPCR stimulates adenylyl cyclase activity and cAMP accumulation, leading to insulin secretion. Adapted from “Insulin production pathway” and “Insulin pathway,” created with BioRender.com (2024).

The ion channel activity of spider venom peptides may lead to potential treatments for chronic pain (see Figure 4). Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs), transient receptor potential (TRP), and NaV and CaV channels are involved in the transduction of stimuli into depolarization of the cell membrane and are therefore important in the development of analgesics (King and Vetter, 2014). Among the ion channels, voltage-gated calcium channels are the main target of spider toxins. For instance, the venom of Phoneutria nigriventer, one of the most studied with not less than 41 neurotoxins identified, is a rich source of potential analgesic drugs due to its activity on CaV channels (Peigneur et al., 2018). ω-ctenitoxin-Pn2a (also known as PnTx3-3) and ω-ctenitoxin-Pn4a (PnTx3-6 or Phα1β), two toxins identified from this venom, both block CaV2.1, CaV2.2, and CaV2.3 channels, as well as CaV1 and CaV1.2. Despite the apparent lack of selectivity, the peptides show analgesic activity in mouse models without side effects (Vieira et al., 2005; Dalmolin et al., 2011). As PnTx3-3 reduces pain and depressive symptoms, it is a credible drug candidate for fibromyalgia (Pedron et al., 2021). In addition to opioid treatment, PnTx3-6 potentiates the analgesic effect of morphine and reduces the adverse effects of regular morphine use, such as tolerance, constipation, and withdrawal symptoms (de Souza et al., 2011). Phoneutria nigriventer venom is also being studied for Huntington’s disease, a fatal neurodegenerative disorder, as Joviano-Santos and colleagues recently demonstrated the neuroprotective effect of PnTx3-6 (Joviano-Santos et al., 2021). Indeed, neuronal survival was improved, and the release of L-glutamate was reduced in mice treated with the toxin. Huntington’s disease is associated with the formation of insoluble aggregates and glutamatergic excitotoxicity associated with progressive neuronal death. This led to an improvement in behavioral and morphological parameters related to motor tests (Joviano-Santos et al., 2021). PnTx3-6 may have important potential in various diseases. Compared to current drugs (morphine and ziconotide), the spider toxin is more effective and has fewer side effects (Rigo et al., 2013). The inconvenience is the limitation of administration, as it is unlikely to be available orally (Tonello et al., 2014).

Other toxins inhibiting CaV2.2 (N-type) channels are of primary interest because of their involvement in pain pathways (for review see Sousa et al., 2013). In addition to chronic pain, CaV2.1 (or P/Q type) channels have been implicated in many neurological disorders including migraine, Alzheimer’s disease, and epilepsy (Nimmrich and Gross, 2012; Inan et al., 2024). ω-Agatoxin-Aa4a (ω-agatoxin IVA) and ω-agatoxin-Aa4b (IVB), from the venom of the American funnel-web spider Agelenopsis aperta, are the most selective blockers of this calcium channel subtype, with an IC50 of about 2 and 3 nM, respectively. The remaining problem for this type of peptide is the poor permeability of the blood-brain barrier (Smith et al., 2015).

NaV1.7 – NaV1.9 voltage-gated sodium channels are expressed in nociceptive neurons and therefore play a critical role in pain signaling. NaV1.7 is by far the most important target for analgesic development (Alexandrou et al., 2016). All spider toxins identified to bind to this channel come from theraphosid spiders (tarantulas) and share the ICK motif. These include huwentoxin-IV (Haplopelma schmidti), GpTX-1 (Grammostola portei), ceratotoxin-1 (Ceratogyrus cornuatus), Pn3a (Phamphobeteus nigricolor), β-theraphotoxin-Tp2a/ProTx-II (Thrixopelma pruriens), and β-theraphotoxin-Cj2a/JzTX-V (Chilobrachys jingzhao). ProTx-II is the most potent NaV1.7 blocker (IC50 = 0.3 nM) of the six currently known, but none is sufficiently selective to be developed as a therapeutic drug. The recent review from Neff and his co-workers describes the peptide engineering of each toxin to achieve better selectivity and highlights some interesting analogs (Neff and Wickenden, 2021). JNJ-63955918, derived from the ProTx-II, increases the selectivity for NaV1.7 from 100- to 1000-fold compared to other NaV channels, but unfortunately, the affinity is altered by ∼10-fold (Flinspach et al., 2017). AM-6120, derived from JzTX-V, was designed as a potent and selective peptide with >750-fold potency against NaV1.5, 1.6, and 1.8. Similarly, ProTx-II analogs optimized for the ability to cross the blood-nerve barrier in vivo have recently been successfully developed (Adams et al., 2022; Nguyen P. T. et al., 2022).

Spider toxins targeting NaV channels are not only interesting for pain treatment. NaV1.1 channels are involved in Dravet syndrome, a form of infantile epilepsy with ataxia and loss of motor skills. Hm1a, identified from Heteroscodra maculata venom, selectively inhibits these NaV1.1 channels and constitutes a promising candidate for treating the disease as its administration improved seizure inhibition and reduced the number of seizures per day in mouse models (Richards et al., 2018).

Spider venom has also been extensively studied in stroke. During cerebral ischemia, which occurs in most strokes (>80%), oxygen is depleted and the brain switches from oxidative phosphorylation to anaerobic glycolysis (Duggan et al., 2021). The pH drops from ∼7.3 to 6.0–6.5 and even below 6.0 in severe ischemia. This low pH activates the acid-sensing ion channels 1a which are the main acid sensors in the brain. Some studies have shown that removing or inhibiting ASIC1a by genetic ablation reduces neuronal death (Xiong et al., 2004). More recently, in 2017, Hi1a, isolated from the Australian funnel-web spider Hadronyche infensa, was shown to be a potent inhibitor of ASIC1a. The real revolution of this peptide is its protection of the brain from neuronal damage for 8 h after a stroke event, instead of “only” 2–4 h for other potential drugs such as psalmotoxin 1 (PcTx1) from Psalmopoeus cambridgei (Chassagnon et al., 2017). Hi1a has a high sequence similarity to PcTx1, but is a more potent inhibitor, and is more selective with no effect on ASIC2a and ASIC3 channels. As a brief aside, in addition to its neuroprotective activity, PcTx1 is also of interest for reducing cartilage destruction in rheumatoid arthritis, in which ASIC1 plays a key role (Saez and Herzig, 2019). Hi1a has the ideal characteristics to be a therapeutic candidate. Very recently, the Australian government announced the next steps for the development of this peptide as the first spider-based drug. The search for other ASIC inhibitors continues with the Hm3a (Heteroscodra maculata) identification, which shows some similarities to PcTx-1. Both completely block ASIC1a with high potency (IC50 PcTx-1 ≃ 0.9 nM and IC50 Hm3a ≃ 1.3 nM) and have a lower activity for ASIC1b (EC50 ≃ 46.5 nM for both). A key advantage of Hm3a over the other drug candidates is its better biological stability (Er et al., 2017).

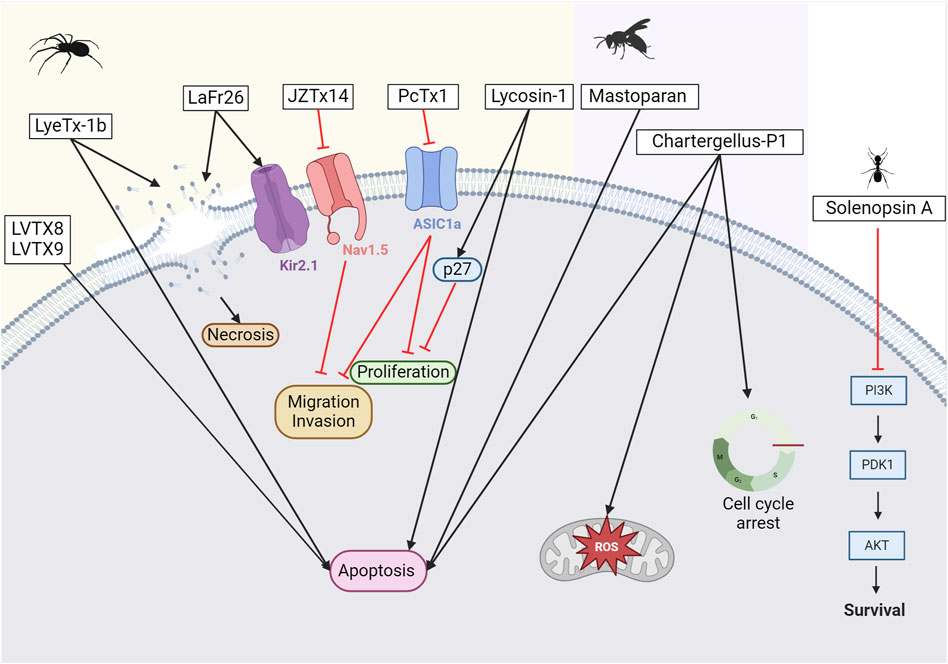

The potential of spider toxins has also been explored in cancer treatment (see Figure 7). Indeed, the venom of Chilobrachys jingzhao has been shown to have the ability to inhibit voltage-gated sodium channels. This is the case of JZTx-14, which was first reported by Zhang in 2018, who demonstrated its ability to block current flow in voltage-gated sodium (NaV1.2–1.8) channels (Zhang et al., 2018). Having observed the pro-metastatic effects of NaV1.5 and knowing that inhibitors of NaV1.5 are seen as emerging therapeutic candidates for breast cancer, Wu and colleagues conducted tests to analyze the potential of the peptide as an inhibitor of this channel in triple-negative breast cancer cells (Luo et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2023). Although this peptide did not reduce cancer cell proliferation, an inhibition of cancer cell migration by affecting the extracellular matrix and cell adhesion molecules was observed.

Figure 7. Potential anticancer toxins from other Arthropods. From left to right, an overview of some toxins with anti-cancer activity from spiders, wasps, and ants. From spider venoms, LVTX8 and LVTX9 can trigger apoptosis in some cancer cells (Zhang P. et al., 2020). LyeTx-1b has been demonstrated to either create pores leading to necrosis or trigger apoptosis (Abdel-Salam et al., 2019). LaFr26 is a pore-forming peptide specific to the Kir2 channel (Okada et al., 2019). JZTx14 is an inhibitor of the NaV1.5 channel. Inhibiting this channel leads to a reduction in the migration and invasion of cancer cells (Zhang et al., 2018). PcTx1 is an inhibitor of the ASIC1a channel. Its inhibition reduces cell proliferation (Rooj et al., 2012). Lycosin-1 can upregulate the p27 protein, which reduces cancer cell proliferation (Liu et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2016). However, it can also trigger apoptosis. From wasp venoms, mastoparan induces apoptosis, while chartergellus-P1 can increase reactive oxygen species and induce cell cycle arrest (de Azevedo et al., 2015; Soares et al., 2022). From ant venom, solenopsin A blocks PI3k and its downstream pathway (Arbiser et al., 2007). Created with BioRender.com (2024).

It has also been shown that ASIC1a expression is altered in gliomas. Consequently, inhibition of ASIC1a with PcTx-1 can reduce the proliferation and migration of glioma cells (Rooj et al., 2012). Notably, reducing ASIC1a expression in other types of cancer cells can also limit proliferation, migration, and invasion (Jin et al., 2015). Due to its remarkable selectivity, PcTx-1 has also recently been used as a true pharmacological tool to identify the ASIC1 subtype associated with breast cancer progression (Yang et al., 2020).

With more than 200 species described to date, spiders of the genus Lycosa have been extensively studied for this purpose. Lycosin-I peptide, derived from a toxin identified in the venom of Lycosa singorensis, a spider found in Central and Eastern Europe, has shown promise as a potential treatment option. Lycosin-I inhibits cancer cell growth in vitro by inducing programmed cell death (Liu et al., 2012). It sensitizes cancer cells to apoptosis and inhibits their proliferation by upregulating the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B, p27, whose major function is to stop the cell cycle at the G1 phase. The mechanisms through which this peptide interacts with membrane cancer cells were investigated by Tan and colleagues (Tan et al., 2016). Furthermore, in 2018, Shen and colleagues demonstrated that lycosin-I inhibits the invasion and metastasis of prostate cancer cells (Shen et al., 2018). To improve the delivery of lycosin-I to cancer cells, the amino acid sequence of the peptide was modified by replacing a lysine with an arginine (Zhang et al., 2017). This change improved the interaction between R-lycosin I and the cancer cell membrane. The selectivity against cancer cells was then improved, while the IC50 against non-cancerous cells remained stable. In addition to amino acid modifications, various fatty acids were incorporated at the N-terminus of the R-lycosin I peptide to enhance its anticancer activity (Jian et al., 2018). The cytotoxicity of the obtained lipopeptide R-C16 with a 16-carbon fatty acid chain was three times higher for cancer cells than that of the original peptide. This was mainly due to the increased hydrophobicity, which enhanced the interaction between the peptide and the cell membrane. In 2017, Tan and colleagues created lycosin-I-modified spherical gold nanoparticles to improve intracellular delivery and were shown to accumulate in cancer cells, in vitro and in vivo (Tan et al., 2017). This suggests a high potential for clinical application in cancer therapy. Gold nanoparticles have been developed for selective targeting of cancer cells, as they can accumulate at tumor sites via non-specific receptor-mediated endocytosis. These particles can be applied locally and activated by laser light via the hyperthermia principle to penetrate directly into the tumor (Vines et al., 2019). Recently, the same team successfully developed lycosin-I-inspired fluorescent gold nanoparticles for tumor cell bioimaging (Tan et al., 2021). In parallel, a lycosin-I peptide coupled to HCPT, a DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor, has been developed (Zhang Q. et al., 2020). This conjugate forms in-solution nanospheres that enhance its antitumor and antimetastatic activity both in vitro and in vivo.

Another peptide, LyeTx I, from another species of the genus Lycosa, Lycosa erythrognatha, was synthesized and evaluated already in 2009 (Santos et al., 2010). This peptide was initially assessed for its antimicrobial properties, against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Candida krusei. Despite a mild hemolytic activity, LyeTx I is a promising candidate for potential clinical applications. In 2018, an optimized peptide known as LyeTx I-b was prepared by incorporating a deletion of the His at position 16 and acetylating the N-terminus (Reis et al., 2018). The new compound exhibits antimicrobial activity that is 10 times higher than the native peptide. LyeTx I-b is not only interesting for its antimicrobial activity but also for its antitumor activity on brain tumor cells (Abdel-Salam et al., 2019). Interestingly, the IC50 values are lower for cancer cells (U-87 MG, glioblastoma cells) than for normal cells (<30 µM versus >100 µM), indicating a selectivity for the cancer cells. Notably, there was no effect on either apoptosis or autophagy in normal cells. However, exposure to IC50 treatment for a short period (approximately 15 min) degrades the integrity of cell membranes. This observation was confirmed by electron microscopy, which revealed pores, holes, and slits indicative of necrotic cell death (Abdel-Salam et al., 2019). The LyeTx I-b peptide has also been studied for its selectivity in degrading breast cancer cells (Abdel-Salam et al., 2021; de Avelar Junior et al., 2022). Exposure to this peptide induced apoptotic death in breast cancer cells but not in glioblastoma ones. Interestingly, systemic injection of the peptide into mice did not result in toxicity to the liver, kidneys, brain, spleen, or heart. Hematological parameters remained normal. In vitro studies confirmed that the peptide has antitumor activity and reduces tumor size. In addition, the peptide was found to have an immunomodulatory effect, reducing the number of monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. This discovery was significant because it demonstrated the involvement of leukocytes in tumor migration and metastasis. Moreover, the combined use of LyeTx-Ib and the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin showed an increase in selectivity and a synergistic effect in a triple-negative breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231(de Avelar Junior et al., 2022). The combination of LyeTx-Ib and cisplatin showed reduced nephrotoxicity compared to cisplatin alone. Cisplatin treatment is associated with significant side effects, with nephrotoxicity occurring in more than 20%–30% of patients. These recent positive results are promising for future clinical trials.

The last Lycosa species under review is Lycosa vittata, mainly found in Southwestern China. Two interesting peptides have been described from its venom, LVTX-8 and LVTX-9. Both showed cytotoxic activity and the ability to induce apoptosis in lung carcinoma cells (A549 and H460) (Zhang P. et al., 2020). Furthermore, RNA sequencing analysis of treated and control samples showed that regulation of the p53 pathway inhibited cancer cell growth and migration. These findings were further validated in a mouse model of metastasis. More recently, analogs of LVTX-8 were shown to increase stability and resistance to protease degradation (Chi et al., 2023). Similarly, LVTX-9 was derived from the Lycosa vittata venom gland cDNA library (Li et al., 2021). However, this peptide exhibits lower levels of cytotoxicity against cancer cells. Chemical modifications involving the addition of fatty acids of different lengths to the N-terminus of LVTX-9 significantly increased the hydrophobicity of the peptides and, in turn, their cytotoxicity. LVTX-9-C18 showed the highest cytotoxicity due to an 18-carbon fatty acid inclusion in its sequence.

The potential effects of tarantula venom on cancer cells have been extensively studied. Of particular note is SNX-482, derived from the African tarantula Hysterocrates gigas. The 41 amino acids peptide, first reported in 1998 (Newcomb et al., 1998), is known to affect the influx of ion channels, specifically, the CaV2.3 subunit-containing R-type calcium channel. However, the role of this channel in cancer initiation and progression is not fully understood. A study investigating the effects of SNX-482 on macrophages has shown that the peptide activates M0-macrophages, and increases molecules involved in antigen presentation, unraveling its potential for cancer immunotherapy (Munhoz et al., 2021).

So far, Lachesana spiders have revealed two peptides of interest: LaFr26 and latarcin-3a. LaFr26 is a pore-forming peptide that can conduct ions, like ionophores (Okada et al., 2015). Notably, this peptide was revealed to be specific for HEK293T cells overexpressing the inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir2.1) channel. Therefore, LaFr26 may be a remarkable choice for hyperpolarized K+ channel expressing cancer cells. This has been demonstrated later and confirmed for two lung cancer cell lines, LX22 and BEN (Okada et al., 2019). The second peptide, latarcin-3a, was first described in 2006 (Kozlov et al., 2006). Various latarcins have been discovered in the venom of Lachesana tarabaevi, with numerous effects noted (for a detailed review, see Dubovskii et al. (2015). For its anticancer properties, the amino acids of the latarcin-3a peptide have recently been modified to increase its hydrophobicity and net charge, resulting in increased antitumor activity (de Moraes et al., 2022).

GsMTx4, a modulator of mechanosensitive ion channels (MSCs), was isolated from the tarantula Grammostola rosea (Gnanasambandam et al., 2017). This peptide has great potential for the treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), a fatal orphan muscle disease for which there is currently no treatment. DMD is caused by a mutation in the gene encoding the dystrophin protein, resulting in a reduction or an absence of this protein and increased activation of MSCs (Ward et al., 2018). Interestingly, GsMTx4 can modulate the MSCs associated with dystrophin deficiency without affecting the MSCs involved in hearing and touch. This clear advantage, combined with its non-toxicity, non-immunogenicity, and high stability, makes it a good therapeutic candidate for DMD (Sachs, 2015). GsMTx4 has been in clinical development since 2014 and has been renamed AT-300 (Saez and Herzig, 2019).

Hymenoptera is an order that includes several species of bees, ants, and wasps and contains over 150,000 species. Hymenoptera venoms are composed of toxins and non-toxic components, such as inorganic salts, sugars, formic acid, free amino acids, hydrocarbons, peptides, and proteins (Guido-Patino and Plisson, 2022). Honeybee (Apis mellifera) venom has been widely studied for many years for its potential in a wide range of treatments, particularly for its antimicrobial activity. The venom consists of peptides, with melittin being the major compound, bioactive amines, non-peptide compounds, and enzymes such as hyaluronidase and PLA2 (group III) (Son et al., 2007).

Group III PLA2s have real potential in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as prion, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s diseases. Prion disease involves the accumulation of a misfolded, β-sheet-enriched isoform (PrPSc) of cellular prion protein (PrPC). The misfolded isoform is partially resistant to protease digestion, and forms aggregated and detergent-insoluble polymers in the CNS (Saverioni et al., 2013). Neuronal cell death caused by prion peptides can be prevented by PLA2s, which reduce PrP (106–126)-mediated neurotoxicity (Jeong et al., 2011). In Alzheimer’s disease, an Aβ peptide aggregation occurs, leading to neuroinflammation with microgliosis. PLA2s, found in bee venom, aid in suppressing microglial activation, leading to reduced cognitive and neuroinflammatory responses (Ye et al., 2016). PLA2s also offer therapeutic potential for Parkinson’s disease. This neurodegenerative disorder is characterized by a progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. As in Alzheimer’s disease, neuroinflammatory mechanisms are involved in neuronal degeneration (Hirsch and Hunot, 2009) and PLA2s have a beneficial neuroprotective effect by increasing the survival of dopaminergic neurons. They can also induce the activation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) (Chung et al., 2015).

While bee venom products, such as melittin, have been extensively studied for their effects on cancer cells, this review will focus on other Hymenoptera species that possess anticancer activities (Pandey et al., 2023). Ant venom has received limited attention in cancer treatment. The red imported fire ant (RIFA), Solenopsis invicta Buren, is a widely distributed invasive species responsible for painful stings annually reported. The venom of this species consists primarily of non-peptide piperidine alkaloids called solenopsins and other noxious substances (Mo et al., 2023). Studies have shown that solenopsin A can reduce angiogenesis in a zebrafish model (Arbiser et al., 2007). Treatment in vitro appears to block the activation of Akt and PI3k, thereby regulating their downstream pathway. This PI3k/Akt pathway is well known to play a role in cancer cell growth, survival, and carcinogenesis (see Figure 7).