95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 22 May 2024

Sec. Polymer Chemistry

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2024.1402870

This article is part of the Research Topic Biocompatible Hydrogels: Properties, Synthesis and Applications in Biomedicine View all 7 articles

Yanting Han1‡

Yanting Han1‡ Jing Cao1‡

Jing Cao1‡ Man Li2‡

Man Li2‡ Peng Ding1

Peng Ding1 Yujie Yang1

Yujie Yang1 Oseweuba Valentine Okoro2

Oseweuba Valentine Okoro2 Yanfang Sun3

Yanfang Sun3 Guohua Jiang4,5

Guohua Jiang4,5 Amin Shavandi2

Amin Shavandi2 Lei Nie1*†

Lei Nie1*†The healing of damaged skin is a complex and dynamic process, and the multi-functional hydrogel dressings could promote skin tissue healing. This study, therefore, explored the development of a composite multifunctional hydrogel (HDCP) by incorporating the dopamine modified hyaluronic acid (HA-DA) and phenylboronic acid modified chitosan (CS-PBA) crosslinked using boric acid ester bonds. The integration of HA-DA and CS-PBA could be confirmed using the Fourier transform infrared spectrometer and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance analyses. The fabricated HDCP hydrogels exhibited porous structure, elastic solid behavior, shear-thinning, and adhesion properties. Furthermore, the HDCP hydrogels exhibited antibacterial efficacy against Gram-negative Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). Subsequently, the cytocompatibility of the HDCP hydrogels was verified through CCK-8 assay and fluorescent image analysis following co-cultivation with NIH-3T3 cells. This research presents an innovative multifunctional hydrogel that holds promise as a wound dressing for various applications within the realm of wound healing.

The skin serves to prevent the invasion of microorganisms and dehydration. Although the human skin has considerable self-regeneration capabilities, it is vulnerable to skin defects that cannot spontaneously heal in extreme situations (Graça et al., 2020; Tavakoli and Klar, 2020). The skin injury caused by cuts, tears, or punctures resulting from external stimulation or trauma, such injuries can inflict permanent pain and lead to long-term psychological distress in patients (Cai et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2021a; Cao et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2021). The wound healing process is intricate and involves overlapping stages of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling (Liang et al., 2021a). The appropriate wound dressing is necessary for the restorative process of wound healing. To promote wound repairs, dressings of different types, such as membranes (semipermeable), gauze, film, hydrocolloids, hydrogels, etc., have been investigated (Han et al., 2017; He et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). Among these, hydrogels are recognized as the preferred candidates for the fabrication of wound dressings due to their porous structure resembling the extracellular matrix, customizable mechanical properties, superb tissue compatibility, favorable hydrophilicity, and hygroscopicity properties (Ahmed, 2015). Besides, the properties of hydrogels are beneficial in that they can absorb exudates or blood, thus providing an environment that is moist and clean, allowing for the exchange of oxygen and water permeability in areas affected by skin defects. This supports wound healing and helps alleviate the pain experienced by patients (Nie et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021b; Jin et al., 2022; Zou et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2023). Diverse biopolymers like chitosan, collagen, hyaluronic acid, and others have been utilized to create hydrogels for wound dressings. The multifunctional hydrogels could be fabricated using crosslinking approaches, such as borate ester bonds and Schiff base bonds (Rasool et al., 2019; Shavandi et al., 2020; Dhand et al., 2021; Jafari et al., 2021; Mirzaei et al., 2021). Earlier studies have shown that the boric acid ester bonds established between diols and boronic acid offer numerous benefits, including an easy preparation process, mild reaction conditions, and effective tissue-adhesive properties (Cambre and Sumerlin, 2011; Kotsuchibashi et al., 2013; Hong et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022). The wound dressing incorporating boric acid ester bonds demonstrates a dynamic recovery feature, responding to breakage and formation while being susceptible to destruction in low pH and low glucose concentrations, making it responsive to the microenvironment of diabetic ulcers. Furthermore, the hydrogel, crosslinked through boric acid ester bonds, exhibits loading and release of bioactive agents, thereby enhancing their utilization. Therefore, wound dressings based on the crosslinking of boric acid ester bonds need to be further explored.

Among common biopolymers, hyaluronic acid (HA) is a high molecular weight polymer compound with biocompatibility, biodegradability, and hydrogel characteristics. These attributes render it well-suited for applications in wound treatment (Grégoire et al., 2023; Nie et al., 2023). As a extracellular component, it plays a vital role in the skin wound repair process. Previous studies have demonstrated that HA can facilitate cell signal transduction, enhance the proliferation and differentiation of endothelial cells, support cell migration, angiogenesis, and modulate inflammation in the course of wound healing. This ultimately contributes to tissue regeneration. Due to these characteristics, HA stands out as a compelling candidate for use as a tissue adhesive (Zhou et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021c). However, the main drawback of HA is its insufficient adhesive performance to close the wound site. Studies have indicated that hydrogels based on polydopamine or containing catechol frequently exhibit strong wet tissue-adhesive capabilities. This phenomenon can be attributed to chemical crosslinking and physical bonding occurring between the polydopamine or catechol groups and soft tissues (Liang et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2022). Therefore, in this research, dopamine was grafted onto HA to compensate for the insufficient adhesion of HA, which also gives the wound dressing enhanced adhesiveness, which is beneficial for wound repair.

The natural polysaccharide of chitosan (CS) is known for its biocompatibility, bioactivity, and biodegradability. It exhibits unique antioxidative, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and hemostatic characteristics, rendering it especially beneficial for use in wound treatment applications (Deng et al., 2021; Deng et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Nie et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2024). The antibacterial action of chitosan primarily relies on the presence of amino groups along its linear molecular chain. These amino groups have the ability to bind with acidic molecules, acquiring a positive charge. As a result, chitosan can interact efficiently with the negatively charged regions of bacterial proteins, resulting in the deactivation of bacteria. Chitosan demonstrates extensive antibacterial effectiveness against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, attributed to its abundant hydroxyl and amino groups capable of forming numerous hydrogen bonds. Consequently, it possesses strong chelating adsorption ability, effectively adsorbing charged substances and finding applications in various fields. However, limitations arise when the pH of chitosan exceeds 6, leading to expansion upon water absorption, poor tensile mechanical properties, rapid degradation, and challenging dissolution. These factors impose some constraints on its application.

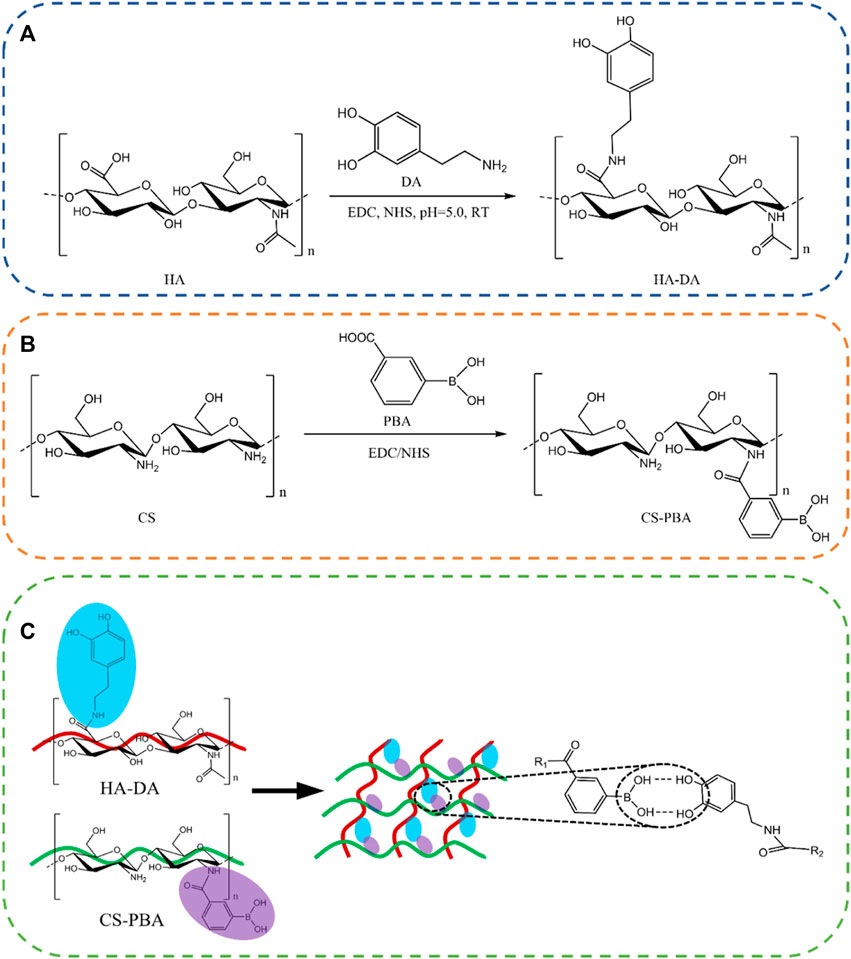

To address above limitations, chitosan is frequently combined with other polymer materials to create composite hydrogels, mitigating the mentioned issues (Ding et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2024). The modification of chitosan with the grafting of carboxymethyl and quaternary ammonium salt groups enhanced the solubility of chitosan and its antibacterial properties (Guo et al., 2024). Alternatively, additional biochemical modifications can be employed to enhance its water solubility and overall performance (Ding et al., 2020). To further increase the solubility and cytocompatibility of chitosan, chitosan was modified by phenylboronic acid to obtain products of phenylboronic acid modified chitosan (CS-PBA) in this paper. At the same time, HA was modified using dopamine to produce dopamine modified hyaluronic acid (HA-DA). Based on the boric acid ester bonds between synthesized CS-PBA and HA-DA, the multifunctional composite hydrogel (HDCP) was fabricated (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Reaction structure diagram of HA-DA (A) and CS-PBA (B). (C) Schematic diagram of HA-DA/CS-PBA hydrogel.

Chitosan (CS), with a deacetylation degree of 80%–95% and viscosity ranging from 50 to 800 cP, was sourced from Ron reagent in Shanghai, China. Dopamine hydrochloride (DA) with a purity of 98%, 3-carboxyphenylboronic acid, N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), N-hydroxy succinimide (NHS), and 2-Morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES) were obtained from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd in Shanghai, China. Hyaluronic acid (HA) was acquired from Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd in Shanghai, China. Fetal bovine serum, trypsin, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Wuhan Huashun Biotechnology Co., Ltd in Wuhan, China. All other solvents and chemicals utilized in this study were of analytical grade and employed without further purification.

The preparation of HA-DA followed a previously reported method with certain modifications. (Cui et al., 2022). Briefly, 1.0 g of CS was dispersed in 100 mL of deionized (DI) water. Subsequently, 575 mg of EDC and 345 mg of NHS were introduced and stirred for 30 min. Following this, 569 mg of dopamine hydrochloride was added to the mixture, maintaining the pH at 5.0 using MES for 3 h. The reaction was conducted at 37°C for 24 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. Following the reaction, the mixture underwent dialysis under acidic conditions for 3 days to remove unreacted molecules. The resulting product, HA-DA, was obtained through freeze-drying and then stored at −20°C for subsequent use.

Initially, 2 g of chitosan (CS) was dissolved in a 1% acetic acid solution. Once complete dissolution was achieved, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 5.5 using 50% MES. Subsequently, 30 mL of N-N dimethyl diamide solution (20% wt), 1.5 g of 3-aminobenzenboric acid, 2.079 g of EDC, and 1.248 g of NHS catalyst were added and stirred for 30 min. Following thorough mixing, the mixture was stirred at room temperature (RT) to ensure sufficient reaction. Finally, the mixture underwent dialysis (MWCO = 10,000 Da) with deionized (DI) water for 3 days. After the dialysis process, the resulting products were freeze-dried and designated as CS-PBA.

Initially, the HA-DA polymer was dissolved in 3% PVA water to create solutions of 1 wt% (w/v), 1.5 wt% (w/v), and 3 wt% (w/v) HA-DA, respectively. Simultaneously, the CS-PBA polymer was dissolved in DI water to generate a 3 wt% (w/v) CS-PBA solution. Subsequently, HDCP composite hydrogels were formed by combining the CS-PBA solution and HA-DA solutions in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio at 25 °C. In this study, HDCP hydrogels were prepared using 1 wt% (w/v), 1.5 wt% (w/v), and 3 wt% (w/v) HA-DA solutions, denoted as HDCP-1, HDCP-1.5, and HDCP-3, respectively. According to the 1H NMR results, the molar ratio of phenylboronic acid and dopamine in HDCP-1, HDCP-1.5, and HDCP-3 were 1.25, 0.625, and 0.417, respectively.

The synthesized polymers (HA, CS, HA-DA, CS-PBA) were dissolved in D2O and subjected to analysis using a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (1H NMR, 600 MHz, NMR spectrometer, JNM ECZ600R/S3). Additionally, the effective crosslinking between HA-DA and CS-PBA in HDCP composite hydrogels was validated through 1H NMR (Lin et al., 2020; Jabrail et al., 2023).

The Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, ThermoFisher) was employed to analyze the functional groups present in HA-DA and CS-PBA polymers and examine potential chemical interactions within HDCP composite hydrogels. FT-IR spectra were collected within the range of 400–4,000 cm-1.

The morphologies and microstructures of the fabricated HDCP hydrogels were examined using a cold field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi, Regulus8220). The freeze-dried samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen for 5 min and then sliced into thin sections. Prior to analysis, a platinum layer was applied to the sample surfaces and maintained for 120 s.

Dynamic rheological testing at room temperature was executed using a modular compact rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) equipped with a circular spline having a 25 mm diameter. An oscillating strain sweep experiment was employed to determine the linear viscoelastic region of the hydrogel. The strain sweep spanned from 0.1% to 1,000% at a frequency of 1 Hz. Following this, a frequency sweep test was conducted on the hydrogel spline under constant conditions of γ = 0.5%, covering frequencies from 0.01 rad/s to 500 rad/s. Additionally, the shear flow properties of the hydrogels were characterized through oscillation frequency experiments performed at 25°C. These experiments involved maintaining a constant strain of 1% while altering the shear rate from 0.1 rad/s to 100 rad/s.

The freeze-dried HDCP hydrogels were measured, and the initial mass (WA) in grams was recorded. Subsequently, the hydrogels were immersed in water and removed at specific times. Following retrieval, the hydrogels were reweighed (WB), and the mass in grams was documented, with excess water removed using filter paper from the hydrogel surface. The swelling rate (SR) of the hydrogels was calculated using Eq. 1 as follows:

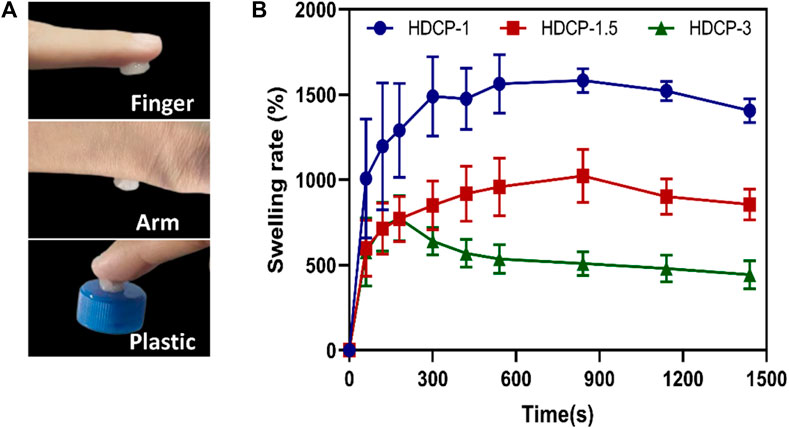

The adhesive characteristics of HDCP hydrogels were evaluated by examining their performance upon direct application to finger, arm, and plastic surfaces. The HDCP hydrogel specimen was attached to the surface of substrates with a little pressure for 1 min, and the photos were recorded, and the adhesive performance was confirmed by keeping the hydrogel attached for 10 min.

Stable 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyls (DPPH) free radicals were employed to assess the antioxidant properties of HDCP hydrogels. In summary, hydrogels were introduced into the DPPH solution, followed by stirring and incubation in darkness for 30 min. The wavelength of DPPH in the mixture was then determined using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Lambda950) over a range of 200 nm–800 nm. The absorbance value at 517 nm was measured, and the scavenging ratio was calculated using the following Eq. 2:

Here, A0 represents the absorbance of the blank, and A1 represents the absorbance of the samples.

In this analysis, two representative bacterial strains, namely, the Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) and Gram-negative Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), served as representative bacteria to analyze the in vitro antibacterial efficacy of HDCP hydrogels. In this context, HDCP hydrogel disks, measuring 4 mm in diameter and 1.5 mm in thickness, were created and underwent sterilization using UV light. Following this, 100 μL of E. coli and S. aureus bacterial suspensions with a concentration of 107 U/mL were individually applied to nutrient agar (NA) plates, each having a diameter of 90 mm. Subsequently, the plates were placed in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 24 h with the HDCP hydrogel disks. After incubation, the diameters of the inhibition zones were measured, and each experiment was independently conducted three times.

To evaluate the cytotoxicity of HDCP hydrogels, mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (NIH-3T3 cells, CRL-1658TM, ATCC) were chosen as the model. NIH-3T3 cells (1 × 105/well, 100 μL) were seeded in a 96-well plate with a 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) DMEM at 37 °C (5% CO2). After subjecting each hydrogel to sterilization through immersion in 75% ethanol under UV for 30 min and subsequent washing with sterilized PBS three times, HDCP hydrogels were introduced into the cell culture. Subsequently, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well after 24, 48, and 72 h, followed by an incubation period of 1 h. The data were recorded at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate. The morphologies of cells after co-culturing with the hydrogel extract for 24 and 72 h were observed using phalloidin-FITC and 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining through an inverted phase microscope and a laser confocal fluorescence microscope.

Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data were presented as means accompanied by the standard deviation (±SD). SPSS software (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL) was employed for the analysis. Statistical significance between groups was determined through analysis of variance (ANOVA), with a significance level set at a p-value of <0.05, <0.01, and <0.001 for 95%, 99%, and 99.9% confidence, respectively.

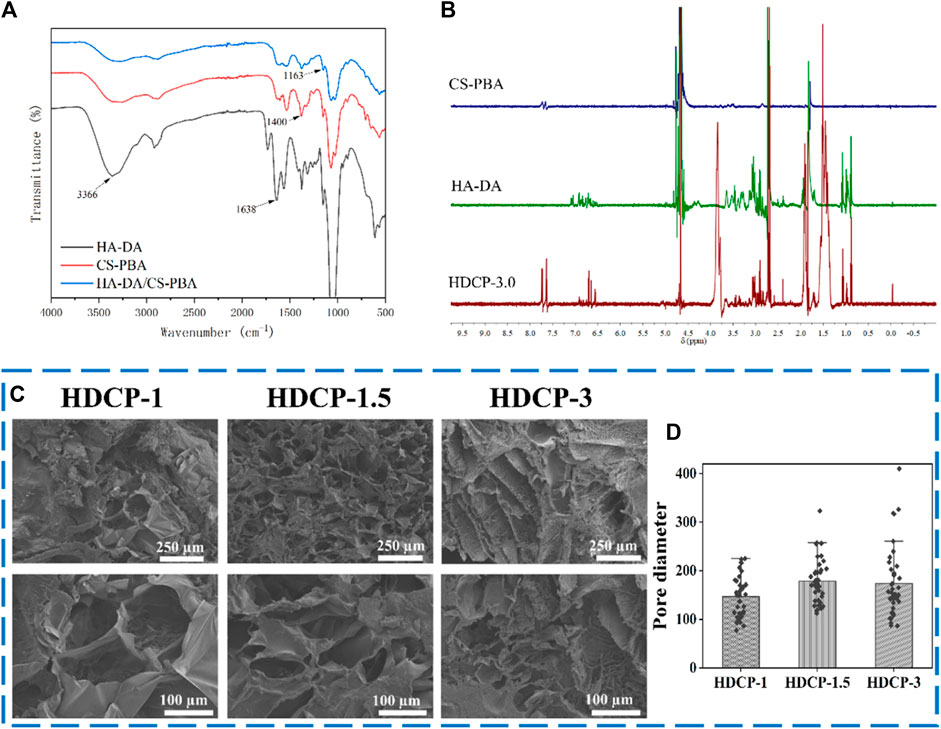

FT-IR and 1H NMR analyses were utilized to discern the structure of CS-PBA and HA-DA polymers (refer to Figure 1). In Figure 1A, the distinctive absorption peak at 1,636 cm−1 in CS-PBA indicates the presence of the amide bond. The peaks observed at 3,375 cm−1 and 1,450–1,600 cm−1 correspond to the N-H stretching vibration of the amide bond and the skeleton vibration of the benzene, respectively, signifying the successful modification of CS with phenylboronic acid. Figure 1B provides confirmation of grafted dopamine through an amide reaction in hyaluronic acid. The broad absorption peak around 3,400 cm−1 corresponds to the O-H bond, while the robust absorption peaks at 1,043 cm−1 and 1,615 cm−1 are attributed to the C-O and N-H bonds, respectively. The spectra of HA-DA reveal a pronounced peak at 1,638 cm−1, indicating the presence of hyaluronan through amide bonds formed by dopamine grafting, thereby affirming the successful DA grafting onto HA. Furthermore, the emergence of a new peak ranging from 7.5 to 8.0 ppm in Figure 1C suggests the successful grafting of phenylboronic acid onto the chitosan segment. The substitution degree of phenylboronic acid onto the chitosan could be calculated using 1H NMR, and in this work, the substitution degree of phenylboronic acid was ∼8%. Additional clarification on the chemical structure of HA-DA was obtained through 1H NMR analysis (Figure 1D). The 1H NMR spectrum of HA-DA reveals a distinct chemical shift at 6.7 ppm, indicating the presence of the proton peak from the benzene ring in the DA catechol group. According to the 1H NMR spectrum of HA-DA, the degree of substitution of dopamine (i.e., catechol conjugation efficiency) was ∼10%. The above results confirmed the successful grafting of dopamine onto hyaluronic acid (HA) through the amide reaction.

The FT-IR spectrum of HDCP hydrogels, the prominent peak at 1,163 cm-1 (see Figure 2A) is due to the borate bond, signifying the positive interaction between CS-PBA and HA-DA polymers. The 1H-NMR spectrum of the HDCP hydrogel further supports the successful crosslinking between the two polymers (see Figure 2B). Subsequently, the morphology and microstructure of the HDCP hydrogels were examined using SEM (see Figure 2C). Porosity is essential for fostering the process of wound healing when hydrogels are used (Liu et al., 2023). It influences not only the rate and depth of cell growth in vivo, as well as cell adhesion and activity, but also affects the processes of nutrient and waste exchange, influencing cell permeability. As shown in Figure 2C, all hydrogels display a porous structure, aiding the transport of molecules during the wound healing process. According to the pore size distribution analysis using the software ImageJ according to SEM images (5 SEM images for each sample) (Figure 2D), sample HDCP-1.5 exhibits a higher pore size than the other two samples. SEM images indicate relatively uniform and interconnected pore structures, suggesting good structural stability and a homogeneous chemical composition.

Figure 2. FT-IR spectra (A) and 1H NMR spectra (B) of HDCP hydrogels. (C) SEM images of HDCP hydrogels, and (D) the pore size distribution analysis of HDCP hydrogels according to SEM images using ImageJ software.

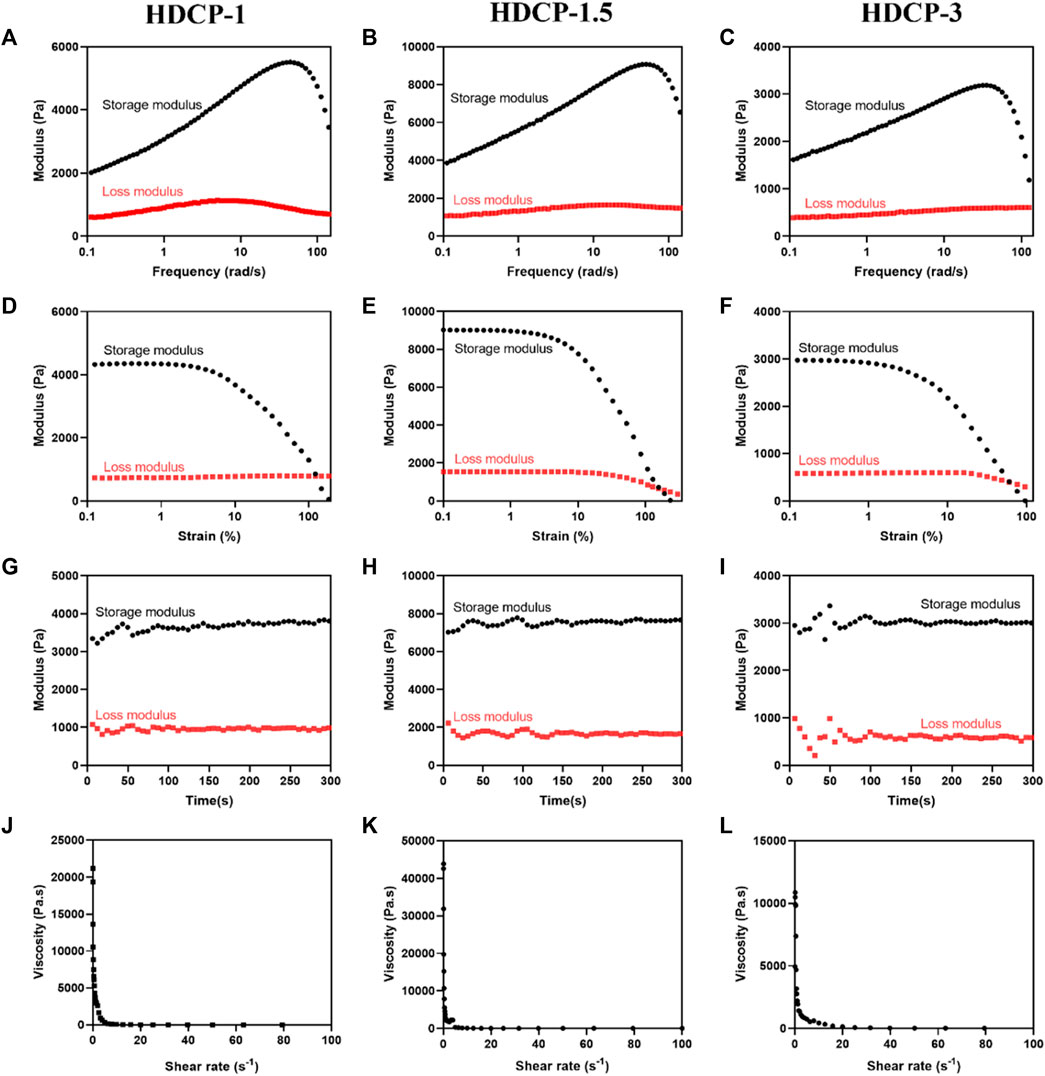

Figure 3 illustrates that all HDCP hydrogels exhibit comparable non-linear rheological characteristics, with the storage modulus (G′) always higher than the corresponding loss modulus (G″) throughout, affirming the elastic solid behavior of the hydrogels (see Figures 3A–C). Additionally, upon the initial application of stress, the hydrogels demonstrate the expected behavior, where the G′ value exceeds the G″ value. Especially, sample HDCP-1.5 displayed higher G′ and G″ values than that of HDCP-1 and HDCP-3 at the first stage of strain (since 0% strain), mainly due to the fact that sample HDCP-1.5 had the optimal ratio of CS-PBA and HA-DA, resulting in the higher crosslinking density than other two samples. However, a prolonged increase in stress can lead to the convergence of G′ and G″, showing the degradation of the network structure within the hydrogel (see Figures 3D–F). The strain tolerance of the hydrogels before “structural failure” follows the order: HDCP-1.5 > HDCP-1 > HDCP-3. Furthermore, the stability of G′ and G″ over time indicates the hydrogels’ consistent behavior, with G′ consistently exceeding G'' (see Figures 3G–I). Furthermore, hydrogels exhibiting excellent injectability can efficiently fill irregular wound areas. Consequently, the injectability of the HDCP hydrogel was further evaluated by analyzing the viscosity’s dependence on the shear rate using a rheometer. Illustrated in Figures 3J–L, the apparent viscosities of the diverse HDCP hydrogels decrease as the shear rate increases, showcasing shear-thinning behavior. In conclusion, the rheological findings suggest that all HDCP hydrogels possess advantageous shear-thinning and injectability characteristics.

Figure 3. Rheological characteristics of the formulated HDCP hydrogels were assessed, including the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″), examined across frequency (A–C), strain (D–F), and time (G–I). Alterations in the viscosity of HDCP hydrogels concerning shear rate were also investigated (J–L).

Figure 4A shows that the HDCP hydrogels have good adhesiveness on the human arm, finger, and plastic surface. The adhesion was assigned to the interactions between unreacted phenolic hydroxyl groups and the surrounding skin tissue surface, including hydrogen bonds and electrostatics (Nie et al., 2023). Moreover, studies have indicated that the adhesive strength is contingent on the hydrogel’s cohesion and interfacial adhesiveness. The heightened crosslinking density enhances the hydrogel’s cohesion, thereby augmenting its adhesiveness (Liang et al., 2021b). Furthermore, a hydrogel with absorbent capabilities can efficiently soak up excess exudate from the wound area, promoting the wound healing process (Liu et al., 2022). Figure 4B, shows that all HDCP hydrogels possess good swelling properties after soaking in deionized water due to the interconnection network and porous structure of hydrogels. Moreover, HDCP-1 exhibits better swelling behavior compared to HDCP-1.5 and HDCP-3.

Figure 4. (A) Photographs display the HDCP hydrogel (HDCP-1) adhered to the human finger and arm, and plastic. (B) Swelling property of HDCP hydrogels in DI water.

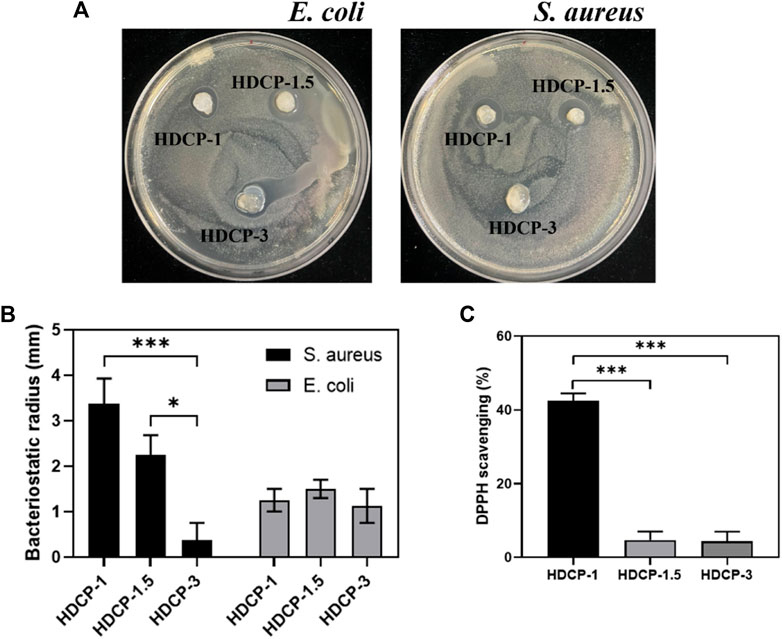

The composite coatings were subjected to a contact-killing bacteria experiment to evaluate their antibacterial activity. Two bacterial models, Gram-negative E. coli and Gram-positive S. aureus, were employed. An inhibition zone test was conducted for both E. coli and S. aureus to assess the antibacterial efficacy of HDCP hydrogels (Figures 5A, B). The results revealed varying degrees of antibacterial effects for all HDCP hydrogels, as depicted in Figure 5B. Notably, HDCP-1 exhibited more consistent and enduring antibacterial properties against S. aureus compared to other HDCP hydrogels. On the other hand, HDCP-1.5 displayed the most enduring antibacterial effects against E. coli compared to the other hydrogels.

Figure 5. (A) Images depicting the antibacterial activity of the hydrogels against E. coli and S. aureus after 24 h. (B) The recorded radius of the inhibitory zone of the hydrogels against E. coli and S. aureus. (C) Assessment of the DPPH scavenging effect of HDCP hydrogels. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

In the dynamic progression of chronic wound healing, inflammation is initiated by infection or cellular exudate, prompting the activation of the immune system and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The excessive build-up of ROS in cells disrupts the equilibrium between oxidants and antioxidants, resulting in tissue damage, intensified infections, and hindered wound healing. (Hamidi et al., 2022). Hence, it is crucial to promptly and continuously eliminate excess ROS from the damaged tissue to facilitate effective wound healing. As depicted in Figure 5C, all HDCP hydrogels demonstrated a certain degree of clearance of DPPH, with HDCP-1 hydrogel achieving ∼42% DPPH clearance rate. This occurrence can be attributed to the transfer of electrons or the provision of hydrogen atoms from nitrogen ion segments to DPPH free radicals.

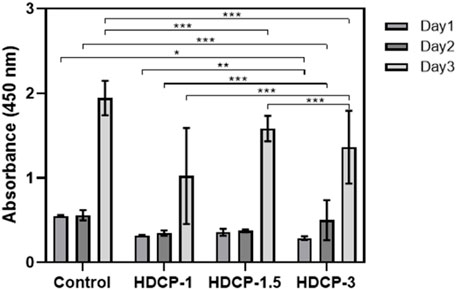

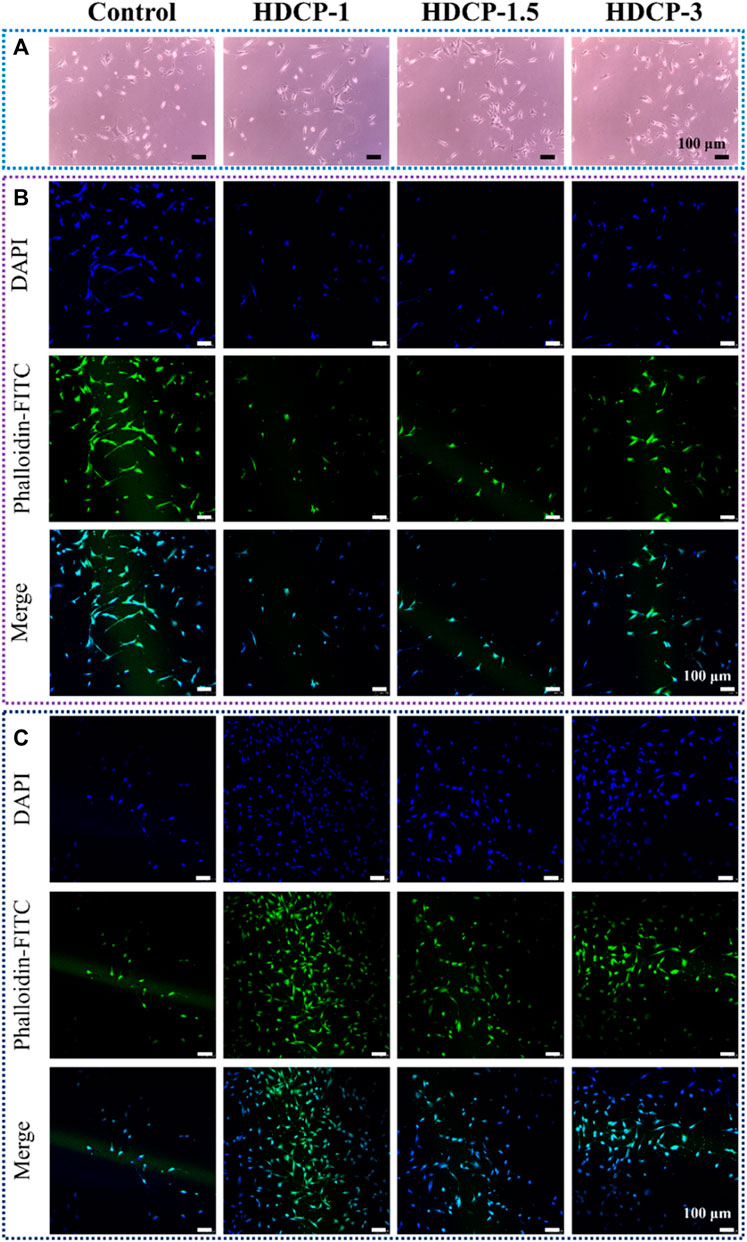

The cytocompatibility of HDCP hydrogels was initially evaluated through the standard CCK-8 method, involving the cultivation of NIH-3T3 cells for varying durations, as illustrated in Figure 6. Based on the CCK-8 results, the proliferation of NIH-3T3 cells showed an upward trend across all HDCP hydrogels from day 1 to day 3, with a notably substantial increase noticed in the HDCP-1.5 hydrogel. These outcomes suggest cytocompatibility of HDCP hydrogels. Furthermore, the evaluation of NIH-3T3 cells cultured with extracts from HDCP hydrogels on both day 1 and day 3 involved examination using an inverted phase microscope and a laser confocal fluorescence microscope (Figure 7). The images reveal that after 24 h of co-culture with the hydrogel extracts at 37 °C, NIH-3T3 cells exhibited normal morphology (Figure 7A), and the cell count increased with prolonged cultivation time (Figures 7B, C), indicating the hydrogels possess cytocompatibility.

Figure 6. The cytocompatibility of HDCP hydrogels was evaluated through CCK-8 after incubation with NIH-3T3 cells for various days. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured, and a control group without the addition of hydrogels was included. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 7. The assessment of biocompatibility for HDCP hydrogels included: (A) Optical microscope images capturing NIH-3T3 cells cultured with HDCP hydrogel extracts on day 1. (B) Fluorescent microscopy images displaying NIH-3T3 cells cultured with HDCP hydrogel extracts for 1 day, stained with phalloidin-FITC/DAPI. (C) Corresponding images for 3 days of cell culture.

This research showcases innovative HDCP hydrogels produced by utilizing dopamine-modified hyaluronic acid (HA-DA) and phenylboronic acid-modified chitosan (CS-PBA), interconnected through boric acid ester bonds crosslinking. The investigation extended to exploring the physicochemical, antibacterial, and cytocompatibility features of the HDCP hydrogels. The resulting hydrogels exhibited a porous structure along with favorable rheological, adhesive, and swelling properties. Additionally, the HDCP hydrogels displayed significant antioxidant activity, effective antibacterial characteristics, and good cytocompatibility. These findings collectively underscore the promising potential of HDCP hydrogels across various biomedical applications, particularly in the realm of wound dressing.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

YH: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. JC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–review and editing. ML: Formal Analysis, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. PD: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. YY: Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. OO: Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. YS: Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. GJ: Writing–review and editing. AS: Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. LN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Nanhu Scholars Program for Young Scholars of XYNU, the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (242300421338), and the Key Scientific Research Projects of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province (24A430034).

We appreciate the contribution of bachelor students Yanbo Wang and Jingyu Li from the Biomedical Engineering Lab of XYNU on the antibacterial properties and cytocompatibility investigation of hydrogels. We acknowledge the help from Prof. Lingling Wang, Prof. Qiuju Zhou, Miss Zihe Jin, Dr. Zongwen Zhang, and Dr. Dongli Xu, in the Analysis and Testing Center of XYNU.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahmed, E. M. (2015). Hydrogel: preparation, characterization, and applications: a review. J. Adv. Res. 6, 105–121. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2013.07.006

Cai, Y., Zhong, Z., He, C., Xia, H., Hu, Q., Wang, Y., et al. (2019). Homogeneously synthesized hydroxybutyl chitosans in alkali/urea aqueous solutions as potential wound dressings. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2, 4291–4302. doi:10.1021/acsabm.9b00553

Cambre, J. N., and Sumerlin, B. S. (2011). Biomedical applications of boronic acid polymers. Polymer 52, 4631–4643. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2011.07.057

Cao, J., Wu, P., Cheng, Q., He, C., Chen, Y., and Zhou, J. (2021). Ultrafast fabrication of self-healing and injectable carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel dressing for wound healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 24095–24105. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c02089

Cui, L., Li, J., Guan, S., Zhang, K., Zhang, K., and Li, J. (2022). Injectable multifunctional CMC/HA-DA hydrogel for repairing skin injury. Mater. today. Bio 14, 100257. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100257

Deng, P., Jin, W., Liu, Z., Gao, M., and Zhou, J. (2021). Novel multifunctional adenine-modified chitosan dressings for promoting wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 260, 117767. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117767

Deng, P., Yao, L., Chen, J., Tang, Z., and Zhou, J. (2022). Chitosan-based hydrogels with injectable, self-healing and antibacterial properties for wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 276, 118718. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118718

Dhand, A. P., Galarraga, J. H., and Burdick, J. A. (2021). Enhancing biopolymer hydrogel functionality through interpenetrating networks. Trends Biotechnol. 39, 519–538. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.08.007

Ding, H., Li, B., Liu, Z., Liu, G., Pu, S., Feng, Y., et al. (2020). Decoupled pH- and thermo-responsive injectable chitosan/PNIPAM hydrogel via thiol-ene click Chemistry for potential applications in tissue engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, e2000454. doi:10.1002/adhm.202000454

Ding, P., Ding, X., Li, J., Guo, W., Okoro, O. V., Mirzaei, M., et al. (2024). Facile preparation of self-healing hydrogels based on chitosan and PVA with the incorporation of curcumin-loaded micelles for wound dressings. Biomed. Mater. 19, 025021. doi:10.1088/1748-605x/ad1df9

Ding, X., Li, G., Zhang, P., Jin, E., Xiao, C., and Chen, X. (2021). Injectable self-healing hydrogel wound dressing with cysteine-specific on-demand dissolution property based on tandem dynamic covalent bonds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2011230. doi:10.1002/adfm.202011230

Graça, M. F. P., Miguel, S. P., Cabral, C. S. D., and Correia, I. J. (2020). Hyaluronic acid—based wound dressings: a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 241, 116364. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116364

Grégoire, S., Man, P. D., Maudet, A., Le Tertre, M., Hicham, N., Changey, F., et al. (2023). Hyaluronic acid skin penetration evaluated by tape stripping using ELISA kit assay. J. Pharm. Biomed. analysis 224, 115205. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2022.115205

Guo, W., Gao, X., Ding, X., Ding, P., Han, Y., Guo, Q., et al. (2024). Self-adhesive and self-healing hydrogel dressings based on quaternary ammonium chitosan and host-guest interacted silk fibroin. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 684, 133145. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.133145

Hamidi, M., Okoro, O. V., Milan, P. B., Khalili, M. R., Samadian, H., Nie, L., et al. (2022). Fungal exopolysaccharides: properties, sources, modifications, and biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 284, 119152. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119152

Han, L., Lu, X., Liu, K., Wang, K., Fang, L., Weng, L.-T., et al. (2017). Mussel-inspired adhesive and tough hydrogel based on nanoclay confined dopamine polymerization. ACS Nano 11, 2561–2574. doi:10.1021/acsnano.6b05318

He, J., Liang, Y., Shi, M., and Guo, B. (2020). Anti-oxidant electroactive and antibacterial nanofibrous wound dressings based on poly(ε-caprolactone)/quaternized chitosan-graft-polyaniline for full-thickness skin wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 385, 123464. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123464

Hong, S. H., Shin, M., Park, E., Ryu, J. H., Burdick, J. A., and Lee, H. (2020). Alginate-boronic acid: pH-triggered bioinspired glue for hydrogel assembly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908497. doi:10.1002/adfm.201908497

Jabrail, F. H., Mutlaq, M. S., and Al-Ojar, R. K. (2023). Studies on agrochemical controlled release behavior of copolymer hydrogel with PVA blends of natural polymers and their water-retention capabilities in agricultural soil. Polym. (Basel) 15, 3545. doi:10.3390/polym15173545

Jafari, H., Delporte, C., Bernaerts, K. V., De Leener, G., Luhmer, M., Nie, L., et al. (2021). Development of marine oligosaccharides for potential wound healing biomaterials engineering. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 7, 100113. doi:10.1016/j.ceja.2021.100113

Jin, L., Guo, X., Gao, D., Liu, Y., Ni, J., Zhang, Z., et al. (2022). An NIR photothermal-responsive hybrid hydrogel for enhanced wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 16, 162–172. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.03.006

Kotsuchibashi, Y., Agustin, R. V. C., Lu, J.-Y., Hall, D. G., Narain, R., and Temperature, pH. (2013). Temperature, pH, and glucose responsive gels via simple mixing of boroxole- and glyco-based polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2, 260–264. doi:10.1021/mz400076p

Li, M., Zhang, Z., Liang, Y., He, J., and Guo, B. (2020). Multifunctional tissue-adhesive cryogel wound dressing for rapid nonpressing surface hemorrhage and wound repair. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 35856–35872. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c08285

Liang, Y., He, J., and Guo, B. (2021a). Functional hydrogels as wound dressing to enhance wound healing. ACS Nano 15, 12687–12722. doi:10.1021/acsnano.1c04206

Liang, Y., Li, Z., Huang, Y., Yu, R., and Guo, B. (2021b). Dual-dynamic-bond cross-linked antibacterial adhesive hydrogel sealants with on-demand removability for post-wound-closure and infected wound healing. ACS Nano 15, 7078–7093. doi:10.1021/acsnano.1c00204

Liang, Y., Zhao, X., Hu, T., Chen, B., Yin, Z., Ma, P. X., et al. (2019). Adhesive hemostatic conducting injectable composite hydrogels with sustained drug release and photothermal antibacterial activity to promote full-thickness skin regeneration during wound healing. Small Weinheim der Bergstrasse, Ger. 15, e1900046. doi:10.1002/smll.201900046

Lin, X., Miao, L., Wang, X., and Tian, H. (2020). Design and evaluation of pH-responsive hydrogel for oral delivery of amifostine and study on its radioprotective effects. Colloids surfaces. B, Biointerfaces 195, 111200. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111200

Liu, S., Zhao, Y., Li, M., Nie, L., Wei, Q., Okoro, O. V., et al. (2023). Bioactive wound dressing based on decellularized tendon and GelMA with incorporation of PDA-loaded asiaticoside nanoparticles for scarless wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 466, 143016. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.143016

Liu, S., Zhao, Y., Wei, H., Nie, L., Ding, P., Sun, H., et al. (2022). Injectable hydrogels based on silk fibroin peptide grafted hydroxypropyl chitosan and oxidized microcrystalline cellulose for scarless wound healing. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 647, 129062. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129062

Mirzaei, M., Okoro, O. V., Nie, L., Petri, D. F., and Shavandi, A. (2021). Protein-based 3D biofabrication of biomaterials. Bioengineering 8, 48. doi:10.3390/bioengineering8040048

Nie, L., Li, J., Lu, G., Wei, X., Deng, Y., Liu, S., et al. (2022). Temperature responsive hydrogel for cells encapsulation based on graphene oxide reinforced poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)/hydroxyethyl-chitosan. Mater. Today Commun. 31, 103697. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.103697

Nie, L., Sun, S., Sun, M., Zhou, Q., Zhang, Z., Zheng, L., et al. (2020). Synthesis of aptamer-PEI-g-PEG modified gold nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin for targeted drug delivery. JoVE J. Vis. Exp., e61139. doi:10.3791/61139

Nie, L., Wei, Q., Sun, M., Ding, P., Wang, L., Sun, Y., et al. (2023). Injectable, self-healing, transparent, and antibacterial hydrogels based on chitosan and dextran for wound dressings. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 233, 123494. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123494

Rasool, A., Ata, S., and Islam, A. (2019). Stimuli responsive biopolymer (chitosan) based blend hydrogels for wound healing application. Carbohydr. Polym. 203, 423–429. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.083

Shavandi, A., Hosseini, S., Okoro, O. V., Nie, L., Eghbali Babadi, F., and Melchels, F. (2020). 3D bioprinting of lignocellulosic biomaterials. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 2001472. doi:10.1002/adhm.202001472

Sun, S., Peng, S., Zhao, C., Huang, J., Xia, J., Ye, D., et al. (2022). Herb-functionalized chronic wound dressings for enhancing biological functions: multiple flavonoids coordination driven strategy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32. doi:10.1002/adfm.202204291

Tang, S., Chi, K., Xu, H., Yong, Q., Yang, J., and Catchmark, J. M. (2021c). A covalently cross-linked hyaluronic acid/bacterial cellulose composite hydrogel for potential biological applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 252, 117123. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117123

Tang, X., Chen, X., Zhang, S., Gu, X., Wu, R., Huang, T., et al. (2021a). Silk-inspired in situ hydrogel with anti-tumor immunity enhanced photodynamic therapy for melanoma and infected wound healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2101320. doi:10.1002/adfm.202101320

Tang, X., Wang, X., Sun, Y., Zhao, L., Li, D., Zhang, J., et al. (2021b). Magnesium oxide-assisted dual-cross-linking bio-multifunctional hydrogels for wound repair during full-thickness skin injuries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2105718. doi:10.1002/adfm.202105718

Tavakoli, S., and Klar, A. S. (2020). Advanced hydrogels as wound dressings. Biomolecules 10, 1169. doi:10.3390/biom10081169

Wu, Q., Wang, L., Ding, P., Deng, Y., Okoro, O. V., Shavandi, A., et al. (2022). Mercaptolated chitosan/methacrylate gelatin composite hydrogel for potential wound healing applications. Compos. Commun. 35, 101344. doi:10.1016/j.coco.2022.101344

Yang, L., Yu, C., Fan, X., Zeng, T., Yang, W., Xia, J., et al. (2022). Dual-dynamic-bond cross-linked injectable hydrogel of multifunction for intervertebral disc degeneration therapy. J. Nanobiotechnology 20, 433. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01633-0

Zeng, X., Chen, B., Wang, L., Sun, Y., Jin, Z., Liu, X., et al. (2023). Chitosan@Puerarin hydrogel for accelerated wound healing in diabetic subjects by miR-29ab1 mediated inflammatory axis suppression. Bioact. Mater. 19, 653–665. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.04.032

Zhou, D., Li, S., Pei, M., Yang, H., Gu, S., Tao, Y., et al. (2020). Dopamine-modified hyaluronic acid hydrogel adhesives with fast-forming and high tissue adhesion. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 12, 18225–18234. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b22120

Keywords: hyaluronic acid, chitosan, hydrogels, cytocompatibility, wound dressing

Citation: Han Y, Cao J, Li M, Ding P, Yang Y, Okoro OV, Sun Y, Jiang G, Shavandi A and Nie L (2024) Fabrication and characteristics of multifunctional hydrogel dressings using dopamine modified hyaluronic acid and phenylboronic acid modified chitosan. Front. Chem. 12:1402870. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2024.1402870

Received: 18 March 2024; Accepted: 07 May 2024;

Published: 22 May 2024.

Edited by:

Christopher Synatschke, Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research, GermanyReviewed by:

Yazhong Bu, University of Galway, IrelandCopyright © 2024 Han, Cao, Li, Ding, Yang, Okoro, Sun, Jiang, Shavandi and Nie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Nie, bmllbGVpZnVAeWFob28uY29t, bmllbGVpQHh5bnUuZWR1LmNu

†ORCID: Lei Nie, orcid.org/0000-0002-6175-5883

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.