- Department of Chemistry, Kookmin University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

The hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) has attracted considerable attention lately because of the high energy density and environmental friendliness of hydrogen energy. However, lack of efficient electrocatalysts and high price hinder its wide application. Compared to a single-phase metal oxide catalyst, mixed metal oxide (MMO) electrocatalysts emerge as a potential HER catalyst, especially providing heterostructured interfaces that can efficiently overcome the activation barrier for the hydrogen evolution reaction. In this mini-review, several design strategies for the synergistic effect of the MMO catalyst on the HER are summarized. In particular, metal oxide/metal oxide and metal/metal oxide interfaces are explained with fundamental mechanistic insights. Finally, existing challenges and future perspectives for the HER are discussed.

1 Introduction

Net-zero emissions have been extensively discussed in the context of combating climate change (Dresp et al., 2019; Na et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021). However, more than 80% of our energy demand is met by fossil fuels such as oil, coal, and gas (Ritchie et al., 2020). The development of green and clean energy sources, such as solar and wind energy, has been hindered because of their intermittent weather-dependent nature (Song et al., 2020). Hydrogen is as an alternative green energy source with a high energy density of 120 MJ kg-1, which exceeds that of its predecessor fuels such as oil, coal, and gas, and only H2O is produced as the combustion by-product (Hughes et al., 2021). However, hydrogen only accounts for 2.5% of global energy consumption, with 94 million tons (Mt) in demand in 2021. Only 1 Mt hydrogen is produced from low-carbon emission sources. In the future, 100 Mt of low-emission hydrogen is required to be produced annually to meet net-zero emissions by 2050 (IEA, 2022).

Sustainable hydrogen production via water electrolysis can be easily achieved by placing two electrodes in an aqueous electrolyte (Ifkovits et al., 2021; Raza et al., 2022). A sufficient voltage difference will cause water to split into its elemental components, with hydrogen (H2) being formed at the cathode and oxygen (O2) being formed at the anode. Depending on the electrolyte conditions, H2 can be formed through the reaction 2H+(aq) + 2e− → H2(g) in acidic conditions or 2H2O+ 2e− → H2 + 2OH− in alkaline conditions. One factor that limits hydrogen production from water splitting is the sluggish kinetics and high thermodynamic energy barrier in the form of overpotential energy (Choi et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Platinum is the best catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). However, its scarcity and high price limit its wide application. Hence, there is a need for developing electrocatalysts with materials that are more abundant and cheaper for the HER.

Metal oxides have been receiving significant attention from the research community owing to their compositional and structural diversity, flexible tunability, low cost, abundance, and environmental friendliness for use as electrocatalysts (Song et al., 2018; Zhu Y. et al., 2020). Despite its unique properties, pristine metal oxides remained unsatisfactory for practical application, especially in the HER, due to the unfavorable intermediate binding strength and stability issues (Cho et al., 2018; Adamson et al., 2020). Mixed metal oxides (MMOs) emerge as a new strategy to fully utilize metal oxides for HER electrocatalysts because they still inherit their unique pristine properties. Optimized adsorption energies can be obtained, and the intrinsic catalytic activity limit can be surpassed in heterostructured MMOs, resulting in a higher HER efficiency. (Lv et al., 2019; Suryanto et al., 2019). Also, the electrocatalysts’ stability in an aqueous environment and alkaline electrolyte was improved significantly (Bates et al., 2015; Cho et al., 2018). Compared to other mixed metal-based ceramic materials, heterostructured MMO is also one of the potential approaches as an affordable electrocatalyst for industrial applications due to its facile synthesis method and lower noble metal loading amount (Seuferling et al., 2021; Nie et al., 2022; Pagliaro et al., 2022). However, there is still no clear guideline for use of MMOs as HER electrocatalysts.

In this mini-review, recent advancements in heterogeneous heterostructured MMOs for HER electrocatalysts, characterized by their overpotential and Tafel slope values, are summarized. We start by elaborating the mechanistic understanding of the HER mechanism and then, summarize the achievement of heterogeneous heterostructured MMO electrocatalysts in the HER. Design strategies for heterostructured MMO electrocatalysts, such as metal oxide/metal oxide and metal/metal oxide heterojunctions, are also explained fundamentally. The synergistic effects of each heterostructured MMO’s composition, morphology, and structure with high HER performance are also fundamentally explained. Finally, we highlight the challenges faced in catalyst development and provide future directions for catalyst development.

2 Reaction mechanisms

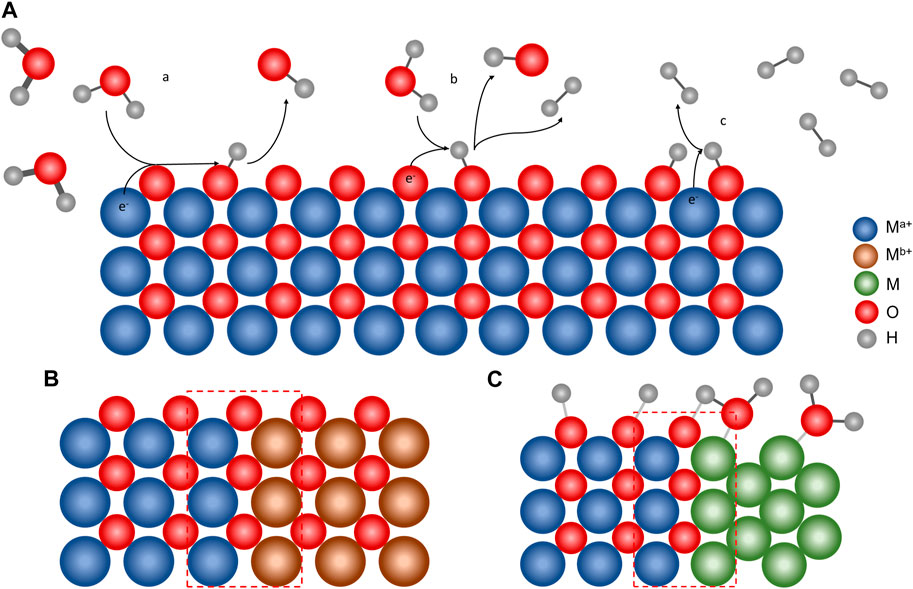

The HER occurs via a multistep electrochemical process (i.e., Volmer, Heyrovsky, and Tafel steps) that involves a two-electron transfer and takes place on the catalyst surface, as shown in Figure 1A. In an acidic medium, the hydronium ion (H3O+) acts as a proton source, and the HER proceeds as follows:

FIGURE 1. (A) Mechanism of the HER on a metal oxide surface, with (a) Volmer, (b) Heyrovsky, and (c) Tafel steps. Material strategies to increase the HER performance by heterostructured MMOs: (B) metal oxide/metal oxide and (C) metal/metal oxide interfaces. The heterojunction shown in red dashed lines plays an important role in enhancing the HER activity of the heterostructured MMO.

A proton is adsorbed on the catalyst’s vacant site, which is represented by M, and an M–H bond is formed (Eq. 1). Then, hydrogen formation can occur in two ways: the dissociation of the M–H bond and H+ transfer from another H3O+ in the bulk solution (Eq. 2) or the dissociation of two M–H bonds (Eq. 3). The proton can originate from H2O in an alkaline or neutral medium, and in this case, the Volmer and Heyrovsky steps changed as follows:

Dissociation of H2O is critical for M–H bond formation in an alkaline or neutral medium. Breaking the H–O–H bond to provide a proton requires higher energy than breaking the H3O+ ion, which readily gives a proton in an acidic medium. Therefore, the HER rate in an alkaline or neutral medium is lower than that in an acidic medium (Hao et al., 2018; Nie et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023).

It is well-known that the Tafel slope is closely related to the HER mechanism. Suppose the Tafel slope is about 120 mV dec−1, the Volmer step is the rate-determining step (RDS), while the values of around 40 and 30 mV dec−1 correspond to Heyrovsky and Tafel steps, respectively. If the Volmer step is the RDS, hydrogen coverage on the electrode surface should be 0 because almost all of the adsorbed hydrogen will be consumed rapidly in the Heyrovsky and Tafel steps. By contrast, the Heyrovsky step-limiting reaction has nearly constant full hydrogen coverage on the electrode surface (Bao et al., 2021).

3 Current progress on mixed metal oxide electrocatalysts for the HER

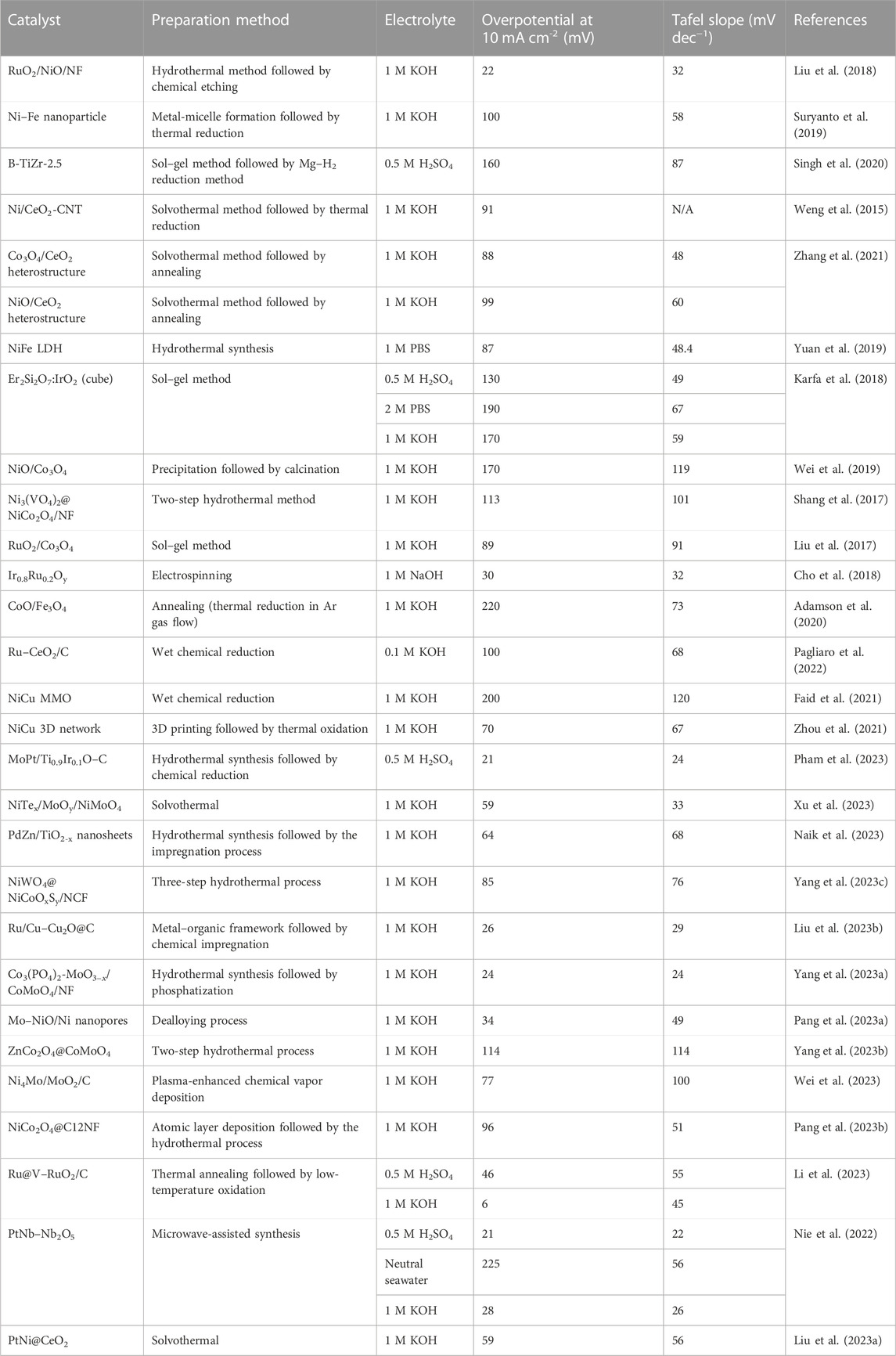

Heterostructured MMOs have been used as electrocatalysts in the HER. The performance of heterostructured MMOs, such as the overpotential and Tafel slope values, is listed in Table 1. Previous studies have shown that MMOs have high HER activity, close to the Pt/C catalyst, known as the HER catalyst benchmark (Cho et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022). This section discusses several strategies for developing heterogeneous MMO electrocatalysts categorized by their metal oxide/metal oxide interface and metal/metal oxide interface (Figures 1B, C).

TABLE 1. Overview of MMO electrocatalyst materials for the HER under acidic, alkaline, and neutral environment.

3.1 Metal oxide/metal oxide interface

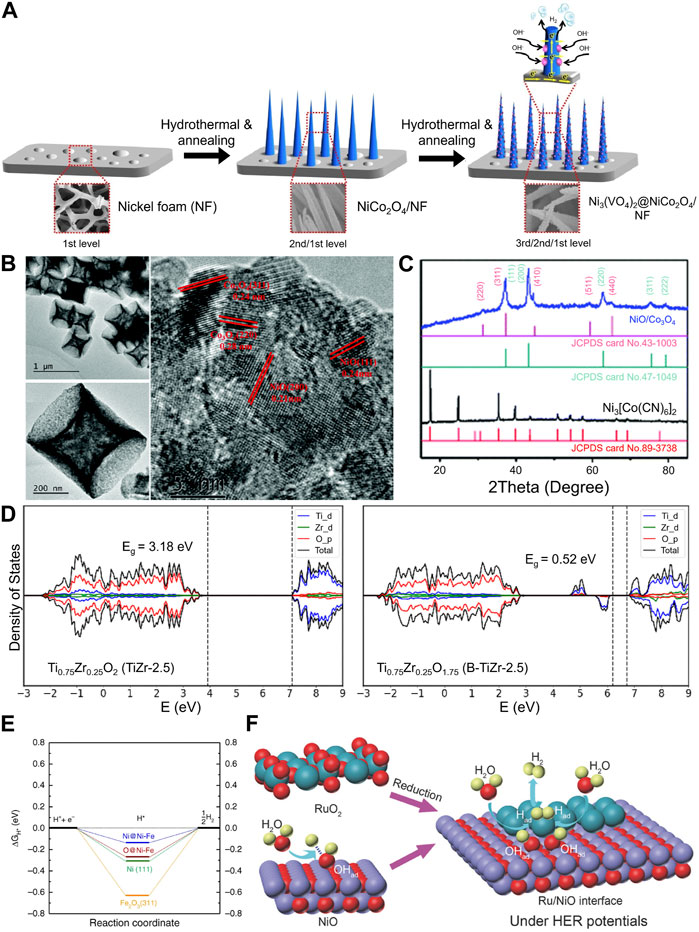

Transition metal oxides (TMOs) have been used as the HER electrocatalyst, yet single-TMO catalysts have been limited by their intrinsic activity. Electrocatalytic activity kinetics is closely related to reactant availability at the catalyst surface (Nguyen et al., 2020). Heterostructured MMOs utilized highly engineered morphology by overgrowing certain compounds on top of each other. One example is by growing Ni3(VO4)2@NiCo2O4 on nickel foam (NF) by using a two-step hydrothermal process. First, NF was used as a foundation to provide the macropores necessary for electrolyte penetration (micropore size: 300 µm). Then, one-dimensional structured NiCo2O4 was grown on the top of the NF. Last, Ni(VO4)2 was grown on the top of NiCo2O4 nanowires, as shown in Figure 2A. The catalyst showed high HER performance at the heterojunction between Ni3(VO4)2 and NiCo2O4 to obtain an overpotential of 113 mV at 10 mA cm-2 with a Tafel slope value of 101 mV dec−1 (Shang et al., 2017).

FIGURE 2. (A) Schematic diagram of the steps involved in the fabrication of a three-dimensional hierarchical structure of Ni3(VO4)2@NiCo2O4/NF. In the fabrication process, NiCo2O4 nanowires were grown on nickel foam by a hydrothermal process, and Ni3(VO4)2 was then grown on NiCo2O4 nanowires by a hydrothermal process reproduced with permission from Shang et al. (2017). (B) HRTEM image of the heterostructured NiO/Co3O4 concave microcuboid which shows individual lattices of Co3O4 and NiO. (C) Individual lattice was also supported by XRD measurement which shows NiO and Co3O4 peaks coexisted in the sample [reproduced with permission from Wei et al. (2019)]. (D) Density of states of Ti0.75Zr0.25O2 and partially reduced Ti0.75Zr0.25O1.75. Introducing oxygen vacancies can generate new electronic states, thereby lowering the bandgap [reproduced with permission from Singh et al. (2020)]. (E) Gibbs free energy diagram of the hydrogen adsorption and desorption on the Fe2O3(311) and Ni(111) surface and the Ni–Fe interface [reproduced with permission form Suryanto et al. (2019)]. (F) MMO-derived Ru–NiO interface showing the synergistic effect induced by the interface of RuO2-derived Ru and NiO interface under HER potentials [reproduced with permission from Liu et al. (2018)].

Later, it was found that the heterojunction on the metal oxide/metal oxide interface plays an important role in enhancing catalytic activity; the heterojunction in the heterostructured MMO has shown better HER activity than alloys or oxide composites. The heterojunction allowed MMOs to have a more exposed active site than alloys or oxide composites (Faid et al., 2021). To increase the number of heterojunctions to an atomic level, Wei and coworkers prepared NiO/Co3O4 concave surface microcubes from a metal–organic framework (MOF) precursor (Ni3[Co(CN)6]2) (Wei et al., 2019). The MOF precursor can ensure homogeneous distribution of NiO/Co3O4 on the cubes. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) analysis shows a lattice of NiO and Co3O4 on the cube surface. It was also supported by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, which shows that NiO and Co3O4 coexisted in the sample (Figures 2B, C). Furthermore, the concave surface obtained from step-by-step annealing allows for electrolyte penetration and increased surface area. The obtained catalyst allowed electrolyte penetration, which favored HER kinetics, and it showed an overpotential of 169.5 mV to achieve a 10 mA cm-2 current density and a Tafel slope of 119 mV dec−1.

Seuferling et al. (2021) showed that a wide compositional range of heterostructure metal oxide catalysts could be deposited easily on an electrode substrate by using a microwave-assisted method involving metal carbonate precursors. Microwave assistance provides sufficient heating for decomposing metal carbonates and facilitates a homogeneous distribution of amorphous oxides on the substrate. Among various amorphous metal oxides synthesized, Co0.8Ni0.2 deposited on NF showed the highest performance, with an overpotential of 350 mV being needed to achieve a current density of 100 mA cm-2 (Seuferling et al., 2021).

The electrocatalytic activity of a particular reaction is dependent on the binding intermediates, which determine the reaction kinetics and final product (Hao et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018). The electronic structure of the catalyst surface governs the binding affinity for the energy of the reaction intermediates. Furthermore, electronic structure engineering modulates electron transport across the catalyst (Chandrasekaran et al., 2020). Hence, an appropriate design of the electronic structure can enhance electronic conductivity and increase charge transfer between the catalyst and electrolyte.

Similar to single-metal oxide electrocatalysts, oxygen vacancy (VO) engineering can be used to tailor the electronic structure of MMO electrocatalysts (Zhang et al., 2018; Hona et al., 2020, 2021). Singh et al. (2020) successfully improved the HER activity of a TiO2/ZrO2 composite by introducing oxygen vacancies into the catalyst to obtain an overpotential value of 160 mV at 10 mA cm-2 and a Tafel slope value of 87 mV dec−1. The grain boundary defects resulting from the introduced ZrO2 could create a charge imbalance on the heterostructure. As a result, an extra proton binds onto the oxygen atom associated with the charge imbalance, creating an excess of -OH groups on the surface, increasing surface acidity. Moreover, the density of state calculation showed that introducing VO to the obtained composite heterostructure generates new electronic states, and the bandgap was reduced from 3.18 to 0.52 eV (Figure 2D), thus increasing the electronic conductivity of the catalyst.

Cerium oxide (CeO2) has shown potential electrocatalytic activity due to the flexible transition valence state between Ce4+ and Ce3+ (Weng et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2022). The idea to generate a TMO/CeO2 heterostructure rich in VO has been employed by Zhang et al. (2021). The interaction between CeO2 and TMOs, such as Co3O4, can tune the electronic structure and reduce HBE. Furthermore, the coexistence of both Ce3+ and Ce4+, and also Co2+ and Co4+, could generate an abundance of VO on the surface. Consequently, the Co3O4/CeO2 catalyst showed a high HER performance of 88 mV overpotential to achieve a 10 mA cm-2 current density and a Tafel slope of 48 mV dec−1.

Further optimization in the electronic structures can be achieved by creating multiple vacancies from a combination of the VO-modulated surface with metal vacancies. For example, Yuan et al. (2019) fabricated the NiFe layered double hydroxide with multiple vacancies. The formation of multiple vacancy defects, including oxygen and metal vacancies, leads to an increase in the electrochemical surface area (ECSA), smaller charge resistance, lower bandgap, and increased reaction kinetics. As a result, incredible HER performance was observed in a neutral solution of 87 mV to obtain a 10 mA/cm−2 with 46.3 mV dec−1 of the Tafel slope value (Yuan et al., 2019).

3.2 Metal/metal oxide interface

Yan and coworkers introduced an amorphous heterostructure catalyst for the HER and developed a three-dimensional core/shell nanosheet by chemically reducing Co3O4 nanosheets in a hydrogen atmosphere (Yan et al., 2015). The reduction in the hydrogen atmosphere results in the formation of a Co(100) core and a thin layer of amorphous cobalt oxide, which can be observed by HRTEM analysis. This unique structure can provide high electrical conductivity in the core, which acts as an electron reservoir, and high HER activity on the surface resulting from defects such as dangling bonds and oxygen vacancies on the surface. The structure showed an overpotential of 129 mV to drive a 20 mA cm-2 current density and a Tafel slope of 44 mV dec−1. Yet, prolonged HER activity performance will only result in a decrease of cobalt oxide due to electrochemical reduction.

Optimizing the H intermediate adsorption energy is the key to enhancing the HER activity. It can be achieved by delicately designing the catalyst interface (Kim et al., 2020). According to the Sabatier principle, the interaction between the catalyst and intermediate reaction should be just right, neither too strong, where the intermediates fail to desorb and block the active sites, nor too weak, in which the intermediates fail to bind to the catalyst (Zhu J. et al., 2020). Moreover, heterostructuring could promote single-metal oxide catalysts and reduce the noble metal loading amount (Kim et al., 2022). Therefore, introducing two components with different binding strengths on the catalyst interface would modify the binding strength, which would imitate the ideal catalyst.

Due to its nature, metal oxides often undergo electrochemical reduction during the HER (Adamson et al., 2020). Heterostructuring the Ni/NiOx composite with TMOs such as Cr2O3 stabilizes Ni/NiOx (Bates et al., 2015). Suryanto et al. (2019) also showed that Fe3+ in the Fe2O3 half-cell potential was altered due to the heterostructure. The Janus Ni–Fe2O3 nanoparticles were formed through ion-oleate metal surfactant complex (micelles) formation that facilitates adjacent iron oxides and metallic Ni. The heterogeneous interface of Ni(111) and Fe2O3(311) surfaces was connected via bridge O atoms. Density-functional theory (DFT) calculations showed that O atoms of Fe2O3 and Ni could act as H atom adsorption sites. Interestingly, bridge O atoms and Ni atoms at the interface had more optimal ΔGH* values of −0.27 and −0.14 eV compared to −0.62 and −0.31 eV of Ni(111) and O atoms in the Fe2O3(311) site, respectively (Figure 2E). Consequently, the Janus Ni–Fe2O3 nanoparticles had a high HER activity with a low overpotential value of 46 mV at 10 mA cm-2 and a small Tafel slope of 58 mV dec−1 (Suryanto et al., 2019).

The formation of a heterostructure interface could help promote water dissociation in the water-splitting reaction. Two different compounds adjacent to each other, which have different binding strengths, could modulate water dissociation completely. Using this idea, Qiao’s group used NiO as a bifunctional promotor for RuO2 in the water-splitting reaction because of the strong M–OH bond affinity of NiO, which could promote HO–H cleavage (Figure 2F). The reduction of RuO2 species into metallic Ru under HER potential could facilitate hydrogen adsorption and recombination. Thus, the synergistic effect of Ru metal and NiO resulted in high HER performance with an overpotential of 22 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm-2 and a Tafel slope of 31.7 mV dec−1 (Liu et al., 2018).

Heterostructuring can generate a new way to break the intrinsic catalytic activity. Easier water dissociation is promoted by synergistic effects at the interfaces. The charge transfer induced from the interfaces enables weakened reactant adsorption, hence preventing surface poisoning from the bonded reactants (Janani et al., 2022; Surendran et al., 2022), resulting in easier hydrogen adsorption and desorption.

The morphological shape is an important factor to be considered for enhancing HER activity (Karfa et al., 2018). The edge and corner sites have a higher electric field distribution, which is conducive to easier charge transfer (Alfath and Lee, 2020). One-dimensional structured catalysts have caught the attention of the research community lately (Kuang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017). The strong electric field at the tip of the 1D structured catalyst allows higher charge transfer. Furthermore, the structure is believed to enhance bubble removal during the HER. Cho et al. (2018) developed nanofibers composed of Ir/IrO2 and RuO2 by using electrospinning and calcination. Optimizing the Ir-to-Ru ratio was helpful in controlling the morphology obtained. The catalyst had incredible HER activity in an alkaline environment, with an overpotential of 29.5 mV and a Tafel slope of 31.5 mV dec−1. Due to the direct generation of metallic Ir and Ru during cathodic polarization, which results in a mixed state between metallic and oxides states, the stability was also significantly enhanced. Hence, the dissolution problem arising from pristine oxides during the HER could be solved, indicating the importance of heterostructure MMO electrocatalysts.

4 Summary

We review the recent advances in heterostructured MMOs owing to their potential for use as HER electrocatalysts and identify the design strategies that hold promise for achieving high HER performance, which was evaluated based on the overpotential and Tafel slope values. The grain boundaries in heterostructured MMOs play an important role as a more exposed active site. The number of exposed active sites can easily be enhanced by increasing the number of heterojunctions. The heterojunction optimized the HER binding strength by combining two components from two different leg positions in the volcano plot. Heterostructured MMOs can also enhance the stability of metal oxides by altering the half-cell potential of the oxides. Therefore, MMOs are promising candidates for HER electrocatalysts because of their high HER activity, vast metal oxide choices, and various preparation strategies. Although many MMO catalysts have been reported with outstanding performances, challenges remain, such as the need for mechanistic understandings on active sites, due to the compositional diversity and dynamic change during the catalytic reaction. In situ analysis techniques, such as Raman spectroscopy and infrared spectroscopy, could reveal direct evidence of active sites of catalysts. In conjunction with spectroscopic approaches, computational science could also be applied to theoretically support the experimental results. This review provides a comprehensive understanding of the MMO design strategy for improving HER performance and provides new insights into the development of MMO interfaces.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by a National R&D Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2021M3D1A2051636); the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry (IPET); and the Korea Smart Farm R&D Foundation (KosFarm) through the Smart Farm Innovation Technology Development Program, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) and the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Rural Development Administration (RDA) (No. 421036-03-1-HD030). It was also supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (NRF-2022R1A4A1019296).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adamson, W., Bo, X., Li, Y., Suryanto, B. H. R., Chen, X., and Zhao, C. (2020). Co-Fe binary metal oxide electrocatalyst with synergistic interface structures for efficient overall water splitting. Catal. Today 351, 44–49. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2019.01.060

Alfath, M., and Lee, C. W. (2020). Recent advances in the catalyst design and mass transport control for the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to formate. Catalysts 10, 859. doi:10.3390/catal10080859

Bao, F., Kemppainen, E., Dorbandt, I., Bors, R., Xi, F., Schlatmann, R., et al. (2021). Understanding the hydrogen evolution reaction kinetics of electrodeposited nickel-molybdenum in acidic, near-neutral, and alkaline conditions. ChemElectroChem 8, 195–208. doi:10.1002/celc.202001436

Bates, M. K., Jia, Q., Ramaswamy, N., Allen, R. J., and Mukerjee, S. (2015). Composite Ni/NiO-Cr2O3 catalyst for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 5467–5477. doi:10.1021/jp512311c

Chandrasekaran, S., Ma, D., Ge, Y., Deng, L., Bowen, C., Roscow, J., et al. (2020). Electronic structure engineering on two-dimensional (2D) electrocatalytic materials for oxygen reduction, oxygen evolution, and hydrogen evolution reactions. Nano Energy 77, 105080. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.105080

Cho, Y., BinYu, A., Lee, C., Kim, M. H., and Lee, Y. (2018). Fundamental study of facile and stable hydrogen evolution reaction at electrospun Ir and Ru mixed oxide nanofibers. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 10, 541–549. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b14399

Choi, H., Surendran, S., Kim, D., Lim, Y., Lim, J., Park, J., et al. (2021). Boosting eco-friendly hydrogen generation by urea-assisted water electrolysis using spinel M 2 GeO 4 (M = Fe, Co) as an active electrocatalyst. Environ. Sci. Nano 8, 3110–3121. doi:10.1039/D1EN00529D

Dresp, S., Dionigi, F., Klingenhof, M., and Strasser, P. (2019). Direct electrolytic splitting of seawater: Opportunities and challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 933–942. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.9b00220

Faid, A. Y., Barnett, A. O., Seland, F., and Sunde, S. (2021). NiCu mixed metal oxide catalyst for alkaline hydrogen evolution in anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. Electrochim. Acta 371, 137837. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2021.137837

Hao, Z., Yang, S., Niu, J., Fang, Z., Liu, L., Dong, Q., et al. (2018). A bimetallic oxide Fe1.89Mo4.11O7 electrocatalyst with highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction activity in alkaline and acidic media. Chem. Sci. 9, 5640–5645. doi:10.1039/c8sc01710g

Hona, R. K., Karki, S. B., Cao, T., Mishra, R., Sterbinsky, G. E., and Ramezanipour, F. (2021). Sustainable oxide electrocatalyst for hydrogen- and oxygen-evolution reactions. ACS Catal. 11, 14605–14614. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c03196

Hona, R. K., Karki, S. B., and Ramezanipour, F. (2020). Oxide electrocatalysts based on earth-abundant metals for both hydrogen- and oxygen-evolution reactions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 11549–11557. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c02498

Hughes, J. P., Clipsham, J., Chavushoglu, H., Rowley-Neale, S. J., and Banks, C. E. (2021). Polymer electrolyte electrolysis: A review of the activity and stability of non-precious metal hydrogen evolution reaction and oxygen evolution reaction catalysts. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 139, 110709. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110709

Ifkovits, Z. P., Evans, J. M., Meier, M. C., Papadantonakis, K. M., and Lewis, N. S. (2021). Decoupled electrochemical water-splitting systems: A review and perspective. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4740–4759. doi:10.1039/d1ee01226f

Janani, G., Surendran, S., Choi, H., An, T. Y., Han, M. K., Song, S. J., et al. (2022). Anchoring of Ni12P5Microbricks in nitrogen- and phosphorus-enriched carbon frameworks: Engineering bifunctional active sites for efficient water-splitting systems. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 1182–1194. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c06514

Karfa, P., Majhi, K. C., and Madhuri, R. (2018). Shape-dependent electrocatalytic activity of iridium oxide decorated erbium pyrosilicate toward the hydrogen evolution reaction over the entire pH range. ACS Catal. 8, 8830–8843. doi:10.1021/acscatal.8b01363

Khan, M. A., Al-Attas, T., Roy, S., Rahman, M. M., Ghaffour, N., Thangadurai, V., et al. (2021). Seawater electrolysis for hydrogen production: A solution looking for a problem? Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4831–4839. doi:10.1039/d1ee00870f

Kim, D., Surendran, S., Jeong, Y., Lim, Y., Im, S., Park, S., et al. (2022). Electrosynthesis of low Pt-loaded high entropy catalysts for effective hydrogen evolution with improved acidic durability. Adv. Mat. Technol. 2200882, 2200882–2200888.doi:10.1002/admt.202200882

Kim, J. C., Lee, C. W., and Kim, D. W. (2020). Dynamic evolution of a hydroxylated layer in ruthenium phosphide electrocatalysts for an alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mat. Chem. A 8, 5655–5662. doi:10.1039/c9ta13476j

Kuang, M., Han, P., Wang, Q., Li, J., and Zheng, G. (2016). CuCo hybrid oxides as bifunctional electrocatalyst for efficient water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mat. 26, 8555–8561. doi:10.1002/adfm.201604804

Lee, C. W., Yang, K. D., Nam, D. H., Jang, J. H., Cho, N. H., Im, S. W., et al. (2018). Defining a materials database for the design of copper binary alloy catalysts for electrochemical CO2 conversion. Adv. Mat. 30, 1704717–1704718. doi:10.1002/adma.201704717

Li, Y., Wang, W., Cheng, M., Feng, Y., Han, X., Qian, Q., et al. (2023). Arming Ru with oxygen vacancy enriched RuO 2 sub-nanometer skin activates superior bifunctionality for pH-universal overall water splitting. Adv. Mat. 10, 2206351. doi:10.1002/adma.202206351

Liu, H., Xia, G., Zhang, R., Jiang, P., Chen, J., and Chen, Q. (2017). MOF-derived RuO2/Co3O4 heterojunctions as highly efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for HER and OER in alkaline solutions. RSC Adv. 7, 3686–3694. doi:10.1039/c6ra25810g

Liu, J., Xu, G., Zhen, H., Zhai, H., Li, C., and Bai, J. (2023a). Directed self-assembled pathways of 3D rose-shaped PtNi@CeO2 electrocatalyst for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 931, 167379. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.167379

Liu, J., Zheng, Y., Jiao, Y., Wang, Z., Lu, Z., Vasileff, A., et al. (2018). NiO as a bifunctional promoter for RuO2 toward superior overall water splitting. Small 14, 1704073. doi:10.1002/smll.201704073

Liu, Y., Cheng, L., Huang, Y., Yang, Y., Rao, X., Zhou, S., et al. (2023b). Electronic modulation and mechanistic study of Ru-decorated porous Cu-rich cuprous oxide for robust alkaline hydrogen oxidation and evolution reactions. ChemSusChem 119, 361–416. doi:10.1002/cssc.202202113

Lv, C., Xu, S., Yang, Q., Huang, Z., and Zhang, C. (2019). Promoting electrocatalytic activity of cobalt cyclotetraphosphate in full water splitting by titanium-oxide-accelerated surface reconstruction. J. Mat. Chem. A 7, 12457–12467. doi:10.1039/c9ta02442e

Na, J., Seo, B., Kim, J., Lee, C. W., Lee, H., Hwang, Y. J., et al. (2019). General technoeconomic analysis for electrochemical coproduction coupling carbon dioxide reduction with organic oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 5193. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12744-y

Naik, K. M., Hashisake, K., Higuchi, E., and Inoue, H. (2023). Bifunctional intermetallic PdZn nanoparticle-loaded deficient TiO 2 nanosheet electrocatalyst for electrochemical water splitting. Mat. Adv. 4, 561–569. doi:10.1039/D2MA00904H

Nguyen, D. L. T., Lee, C. W., Na, J., Kim, M. C., Tu, N. D. K., Lee, S. Y., et al. (2020). Mass transport control by surface graphene oxide for selective CO production from electrochemical CO2 reduction. ACS Catal. 10, 3222–3231. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b05096

Nie, N., Zhang, D., Wang, Z., Yu, W., Ge, S., Xiong, J., et al. (2022). Stable PtNb-Nb2O5 heterostructure clusters @CC for high-current-density neutral seawater hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 318, 121808. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.121808

Pagliaro, M. V., Bellini, M., Bartoli, F., Filippi, J., Marchionni, A., Castello, C., et al. (2022). Probing the effect of metal-CeO2 interactions in carbon supported electrocatalysts on alkaline hydrogen oxidation and evolution reactions. Inorganica Chim. Acta 543, 121161. doi:10.1016/j.ica.2022.121161

Pang, C., Zhu, S., Xu, W., Liang, Y., Li, Z., Wu, S., et al. (2023a). Self-standing Mo-NiO/Ni electrocatalyst with nanoporous structure for hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 439, 141621. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2022.141621

Pang, N., Tong, X., Deng, Y., Xiong, D., Xu, S., Wang, L., et al. (2023b). Self-supporting NiCo2O4 nanoneedle arrays on atomic-layer-deposited CoO nanofilms on nickel foam for efficient and stable hydrogen evolution reaction. Mat. Sci. Eng. B 289, 116255. doi:10.1016/j.mseb.2022.116255

Pham, H. Q., Huynh, T. T., and Huynh, Q. (2023). Mixed-oxide-containing composite-supported MoPt with ultralow Pt content for accelerating hydrogen evolution performance. Chem. Commun. 59, 215–218. doi:10.1039/D2CC05663A

Raza, A., Deen, K. M., Asselin, E., and Haider, W. (2022). A review on the electrocatalytic dissociation of water over stainless steel: Hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 161, 112323. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112323

Ritchie, H., Roser, M., and Rosado, P. (2020). Energy. Our World Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/energy (Accessed October 24, 2022).

Seuferling, T. E., Larson, T. R., Barforoush, J. M., and Leonard, K. C. (2021). Carbonate-derived multi-metal catalysts for electrochemical water-splitting at high current densities. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 16678–16686. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c05519

Shang, X., Chi, J., Lu, S., Dong, B., Liu, Z.-Z., Yan, K., et al. (2017). Hierarchically three-level Ni3(VO4)2@NiCo2O4 nanostructure based on nickel foam towards highly efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution. Electrochim. Acta 256, 100–109. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2017.10.017

Singh, K. P., Shin, C. H., Lee, H. Y., Razmjooei, F., Sinhamahapatra, A., Kang, J., et al. (2020). TiO2/ZrO2 nanoparticle composites for electrochemical hydrogen evolution. ACS Appl. Nano Mat. 3, 3634–3645. doi:10.1021/acsanm.0c00346

Song, F., Bai, L., Moysiadou, A., Lee, S., Hu, C., Liardet, L., et al. (2018). Transition metal oxides as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction in alkaline solutions: An application-inspired renaissance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7748–7759. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b04546

Song, J., Wei, C., Huang, Z. F., Liu, C., Zeng, L., Wang, X., et al. (2020). A review on fundamentals for designing oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 2196–2214. doi:10.1039/c9cs00607a

Surendran, S., Jesudass, S. C., Janani, G., Kim, J. Y., Lim, Y., Park, J., et al. (2022). Sulphur assisted nitrogen-rich CNF for improving electronic interactions in Co-NiO heterostructures toward accelerated overall water splitting. Adv. Mat. Technol. 8, 2200572. doi:10.1002/admt.202200572

Suryanto, B. H. R., Wang, Y., Hocking, R. K., Adamson, W., and Zhao, C. (2019). Overall electrochemical splitting of water at the heterogeneous interface of nickel and iron oxide. Nat. Commun. 10, 5599. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13415-8

Wang, M., Zhang, M., Song, W., Zhou, L., Wang, X., and Tang, Y. (2022). Heteroatom-doped amorphous cobalt-molybdenum oxides as a promising catalyst for robust hydrogen evolution. Inorg. Chem. 61, 5033–5039. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c03976

Wang, S., Lu, A., and Zhong, C. J. (2021). Hydrogen production from water electrolysis: Role of catalysts. Nano Converg. 8, 4. doi:10.1186/s40580-021-00254-x

Wei, G., Wang, C., Zhao, X., Wang, S., and Kong, F. (2023). Plasma-assisted synthesis of Ni4Mo/MoO2 @carbon nanotubes with multiphase-interface for high-performance overall water splitting electrocatalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 939, 168755. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.168755

Wei, X., Zhang, Y., He, H., Gao, D., Hu, J., Peng, H., et al. (2019). Carbon-incorporated NiO/Co3O4 concave surface microcubes derived from a MOF precursor for overall water splitting. Chem. Commun. 55, 6515–6518. doi:10.1039/c9cc02037c

Weng, Z., Liu, W., Yin, L. C., Fang, R., Li, M., Altman, E. I., et al. (2015). Metal/oxide interface nanostructures generated by surface segregation for electrocatalysis. Nano Lett. 15, 7704–7710. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b03709

Xu, W., Wu, K., Wu, Y., Guo, Q., Fan, F., Li, A., et al. (2023). High-efficiency water splitting catalyzed by NiMoO4 nanorod arrays decorated with vacancy defect-rich NiTex and MoOy layers. Electrochim. Acta 439, 141712. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2022.141712

Xu, Y., Hao, X., Zhang, X., Wang, T., Hu, Z., Chen, Y., et al. (2022). Increasing oxygen vacancies in CeO2 nanocrystals by Ni doping and reduced graphene oxide decoration towards electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. CrystEngComm 24, 3369–3379. doi:10.1039/d2ce00209d

Yan, X., Tian, L., He, M., and Chen, X. (2015). Three-dimensional crystalline/amorphous Co/Co3O4 core/shell nanosheets as efficient electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Lett. 15, 6015–6021. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02205

Yang, M., Shi, B., Tang, Y., Lu, H., Wang, G., Zhang, S., et al. (2023a). Interfacial chemical bond modulation of Co3(PO4)2-MoO3–<i>x</i> heterostructures for alkaline water/seawater splitting. Inorg. Chem. 3, 2838–2847. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c04181

Yang, W.-D., Xiang, J., Zhao, R.-D., Loy, S., Li, M.-T., Ma, D.-M., et al. (2023b). Nanoengineering of ZnCo2O4@CoMoO4 heterogeneous structures for supercapacitor and water splitting applications. Ceram. Int. 49, 4422–4434. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.09.329

Yang, Y., Zhang, L., Guo, F., Wang, D., Guo, X., Zhou, X., et al. (2023c). A robust octahedral NiCoOxSy core-shell structure decorated with NiWO4 nanoparticles for enhanced electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 439, 141618. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2022.141618

Yuan, Z., Bak, S. M., Li, P., Jia, Y., Zheng, L., Zhou, Y., et al. (2019). Activating layered double hydroxide with multivacancies by memory effect for energy-efficient hydrogen production at neutral pH. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 1412–1418. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.9b00867

Zhang, H., Guo, X., Liu, W., Wu, D., Cao, D., and Cheng, D. (2023). Regulating surface composition of platinum-copper nanotubes for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction in all pH values. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 629, 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2022.08.116

Zhang, T., Wu, M. Y., Yan, D. Y., Mao, J., Liu, H., Hu, W. Bin, et al. (2018). Engineering oxygen vacancy on NiO nanorod arrays for alkaline hydrogen evolution. Nano Energy 43, 103–109. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.11.015

Zhang, Y., Liao, W., and Zhang, G. (2021). A general strategy for constructing transition metal Oxide/CeO2 heterostructure with oxygen vacancies toward hydrogen evolution reaction and oxygen evolution reaction. J. Power Sources 512, 230514. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230514

Zhou, B., Hu, H., Jiao, Z., Tang, Y., Wan, P., Yuan, Q., et al. (2021). Thermal oxidation–electroreduction modified 3D NiCu for efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 46, 22292–22302. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.04.090

Zhu, J., Hu, L., Zhao, P., Lee, L. Y. S., and Wong, K. Y. (2020a). Recent advances in electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution using nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 120, 851–918. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00248

Keywords: hydrogen evolution reaction, electrocatalyst, mixed metal oxide, reaction mechanism, modulation strategy

Citation: Pratama DSA, Haryanto A and Lee CW (2023) Heterostructured mixed metal oxide electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Front. Chem. 11:1141361. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2023.1141361

Received: 10 January 2023; Accepted: 01 March 2023;

Published: 14 March 2023.

Edited by:

Kyoungsuk Jin, Korea University, Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Haneul Jin, Dongguk University Seoul, Republic of KoreaUk Sim, Korea Institute of Energy Technology (KENTECH), Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2023 Pratama, Haryanto and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chan Woo Lee, Y3dsZWUxQGtvb2ttaW4uYWMua3I=

Dwi Sakti Aldianto Pratama

Dwi Sakti Aldianto Pratama Andi Haryanto

Andi Haryanto Chan Woo Lee

Chan Woo Lee