Erratum: Porous adsorption materials for carbon dioxide capture in industrial flue gas

- 1Zhejiang Tongji Vocational College of Science and Technology, Hang Zhou, China

- 2College of Geomatics and Municipal Engineering, Zhejiang University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Hang zhou, China

- 3Empa, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, ETH Domain, Dübendorf, Switzerland

Due to the intensification of the greenhouse effect and the emphasis on the utilization of CO2 resources, the enrichment and separation of CO2 have become a current research focus in the environment and energy. Compared with other technologies, pressure swing adsorption has the advantages of low cost and high efficiency and has been widely used. The design and preparation of high-efficiency adsorbents is the core of the pressure swing adsorption technology. Therefore, high-performance porous CO2 adsorption materials have attracted increasing attention. Porous adsorption materials with high specific surface area, high CO2 adsorption capacity, low regeneration energy, good cycle performance, and moisture resistance have been focused on. This article summarizes the optimization of CO2 adsorption by porous adsorption materials and then applies them to the field of CO2 adsorption. The internal laws between the pore structure, surface chemistry, and CO2 adsorption performance of porous adsorbent materials are discussed. Further development requirements and research focus on porous adsorbent materials for CO2 treatment in industrial waste gas are prospected. The structural design of porous carbon adsorption materials is still the current research focus. With the requirements of applications and environmental conditions, the integrity, mechanical strength and water resistance of high-performance materials need to be met.

1 Introduction

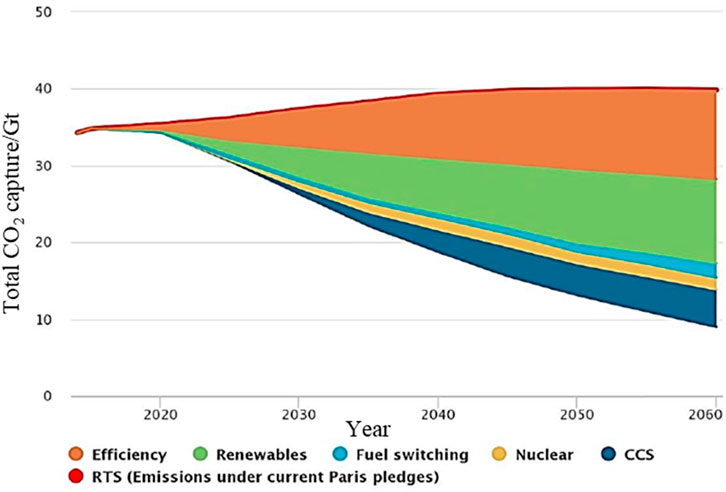

Due to the massive consumption of fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas), greenhouse gases cause global temperature rise, and it is imminent to curb global warming. As the 195 member states of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change reached the Paris Agreement at the Paris Climate Change Conference, the agreement established a global action plan to limit the rise in global average temperature this century to 2°C of pre-industrial revolution levels or lower. And try to control the global temperature rise below 1.5°C to avoid the crisis brought by climate change, which also builds a bridge between today’s policy and the climate goals by the end of this century (Lesnikowski et al., 2017). With the goal of controlling the temperature rise of 2°C, both the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Energy Agency (IEA) have emphasized the important role of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology in achieving long-term high-efficiency carbon dioxide emission reduction. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is considered, one of the effective measures to cope with the challenge of climate change. It has irreplaceable advantages in reducing carbon dioxide emissions. CCS has strong adaptability to the existing energy system, stable operation, and can achieve substantial emission reduction of carbon dioxide in the power system. It is essential to ensure energy security and achieve sustainable development (Bui et al., 2018). CCS is the only way for coal-intensive industries such as coal chemical industry, cement, steel and oil refineries to achieve substantial carbon dioxide emissions reductions. CCS and renewable energy can form complementary technologies to achieve decarbonization goals (Haszeldine, 2009). Carbon dioxide direct air capture technology (DAC) and biomass energy CCS technology (BECCS) can achieve large-scale harmful carbon emissions (Change, 2014; Ma et al., 2021). The combination of CCS and steam methane reforming can obtain “blue hydrogen”, also called carbon-neutral hydrogen, which promotes the transformation of the energy system to carbon-neutral (Davison, 2009). However, the current promotion of CCS still has a high degree of uncertainty, and its progress depends on the degree of reduction in energy consumption and cost of the whole chain of CCS, the cost competition between CCS and other low-carbon technologies. The gain of carbon capture benefits throughout the life cycle of CCS and other factors. Figure 1 shows the “2 °C scenario (2DS)” energy technology route given by IEA in the “Energy Technology Outlook 2017” (Orr, 2009). The model predicts that from 2015 to 2060, the cumulative carbon emission reduction achieved through CCS technology will be 14%. In 2050 and 2060, the carbon dioxide emission reduction through CCS will need to reach 4.2 Gt and 4.9 Gt, respectively. In the below 2°C scenario (B2DS) route predicted by the IEA, by 2060, the cumulative carbon emission reduction contribution contributed by CCS needs to reach 32%. How to efficiently capture the carbon dioxide in the flue gas is a favorable way to effectively control the increase of greenhouse gases.

FIGURE 1. The contribution rate of different technologies to carbon emission reduction in the 2DS scenario (IEA, 2017).

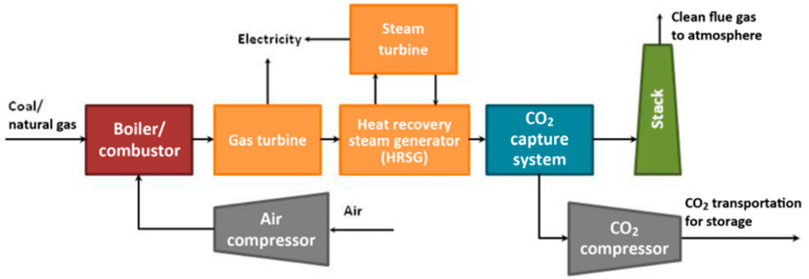

CCS is a unified whole of the organic connection of carbon dioxide capture, transportation, storage, and utilization. The technology involved in the entire process chain is diverse and complex, and the development stages of different technologies are not the same. According to the technical characteristics of the carbon dioxide separation process, the carbon dioxide capture technology of thermal power plants is usually divided into most mature carbon capture technology is the post-combustion carbon dioxide capture technology of chemical absorption based on alcohol amine absorbents (Gibbins and Chalmers, 2008). The post-combustion carbon dioxide capture technology of chemical absorption based on alcohol amine absorbents is currently the most mature carbon capture technology. Large-scale commercial operations were achieved in the United States and Canada in 2014 and 2017 (Lipponen et al., 2017). In addition, MTR (Membrane Technology and Research) successfully developed for the first time a polymer membrane (Polaris Membrane) that can be used in commercial applications to separate carbon dioxide from syngas (Kniep et al., 2017). Post-combustion capture is a technology that captures carbon dioxide from the flue gas after the boiler is burned. It separates carbon dioxide with a lower partial pressure from high-concentration nitrogen and a small amount of oxygen and water vapor mainly used in coal-fired, oil-fired and gas-fired power plants or carbon dioxide capture in natural gas combined cycles. This technology has little impact on the existing power plant production process. The energy consumption of carbon dioxide capture can be controlled by adjusting the carbon dioxide separation efficiency or flue gas flow. In addition, this technology can be used in many industrial processes (such as the cement industry and the steel industry). However, due to the low concentration of carbon dioxide and the low partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the flue gas, the CO2 capture material after combustion needs to have good CO2 adsorption and separation performance under low pressure (Kanniche et al., 2010). Based on the characteristics of low CO2 partial pressure of power plant flue gas, post-combustion capture is currently the most common capture method. The capture mode can be divided into the absorption method, adsorption method, membrane separation method, cryogenic distillation method, etc., Compared with the post-combustion capture technology, the integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) pre-combustion capture and oxygen-enriched combustion technology has a lower technical readiness index, and large-scale commercial applications have not yet been realized.

The post-combustion capture system is shown in Figure 2. The post-combustion capture process can be divided into the following three steps: 1) Pre-purification of flue gas, boiler flue gas is purified by denitration, dust removal, and desulfurization to meet the requirements of CO2 separation equipment; 2) CO2 capture, flue gas enters CO2 absorption/adsorption device (such as MEA absorption tower) realizes the removal of CO2, and the flue gas (mainly N2, water vapor) that does not contain (or contains low concentration) CO2 is discharged through the chimney; 3) Absorbent/adsorbent Regeneration, the CO2-rich absorbent or adsorbent releases high-purity CO2 to achieve regeneration. It is worth noting that the CO2 content in the flue gas during post-combustion capture is the lowest among the three capture technologies, only 3–20 vol% (Ebner and Ritter, 2009). Therefore, this technology has very high requirements for absorbents/adsorbents. Since the temperature range of the synthesis gas for capturing CO2 before combustion in IGCC is 250–400°C (Xiao et al., 2011), a medium temperature adsorbent should be used. The post-combustion capture system in coal-fired power plants mainly adopts the solvent absorption method based on alcohol amine solution. However, the traditional solvent absorption method has shortcomings such as high energy consumption and high corrosiveness, and it is urgent to develop a more cost-effective absorbent/adsorbent (Subha et al., 2015; Vega et al., 2020; Kearns et al., 2021). Common CO2 capture materials include activated carbon, zeolite, molecular sieves, metal oxides, and metal-organic framework materials (Leperi et al., 2019; Pardakhti et al., 2019; Omodolor et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2021). The main criteria for a better adsorbent material should include the following aspects: higher specific surface area, better adsorption selectivity, good adsorption performance and cycle stability. This review discusses how to optimize porous adsorption materials based on the treatment of CO2 in industrial waste gas around the above three dimensions. And summarized a series of problems currently faced, and looked forward to the future research direction.

FIGURE 2. Schematic diagram of the combustion CO2 capture device of a coal-fired power plant (Zaman and Lee, 2013).

2 Adsorption Mechanism of Carbon Dioxide

The adsorption method uses an adsorbent to selectively adsorb a specific gas to achieve the purpose of separation. The complete adsorption process includes two steps: adsorption and desorption. Periodic adsorption and desorption are used to complete the concentration of carbon dioxide and the regeneration of adsorbent materials. The continuous operation can be achieved by parallel adsorption towers (Shen et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020a). According to the different adsorption mechanism, the adsorption method can be divided into physical and chemical adsorption. Physical adsorption refers to the combination of adsorbate molecules and the surface of the adsorbent through microscopic forces (Coulomb force and Van der Waals force) to form stable adsorption without forming chemical bonds. When the adsorbed gas contacts the adsorbent, due to the attraction of the adsorbent surface, the adsorbed gas will form an adsorption layer on the surface of the adsorbent. This adsorption layer is called the adsorption phase. The density of the adsorption phase is much greater than thegas density. The remaining gravitational force on the surface and the gravitational force of the gas molecules are combined, and the adsorption affinity produced by the mutual combination is called the adsorption force. There are generally three sources of adsorption force: 1) Van der Waals force including repulsive force and attractive force prevailing between atoms and molecules; 2) Electrostatic Coulomb force between charged particles; 3) Due to the induction of the permanent dipole moment, the adjacent molecules produce charge displacement, which causes the induced polarization and produces the induced force of the induced dipole moment. The desorption of adsorbed gas molecules on the surface of the framework material can be completed under low energy consumption, and the reuse of the framework material is realized, which is the most significant advantage of physical adsorption. Physical adsorption adsorbent has good regeneration performance, but its selectivity is poor, and the adsorption capacity is low at high temperatures. Chemical adsorption refers to the formation of chemical bonds between gas molecules and the surface of the adsorbent to bond them together.

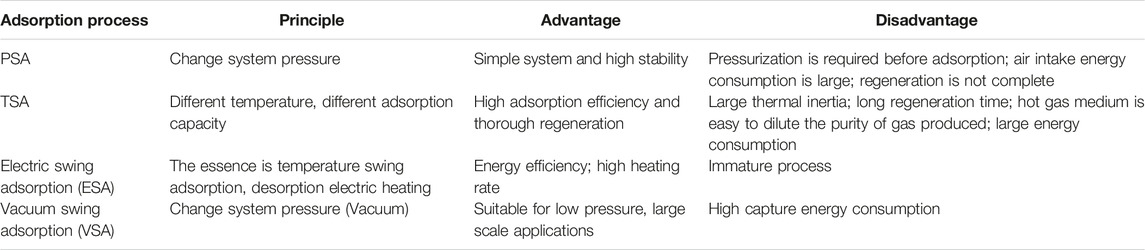

The adsorbent has a high adsorption capacity and good selectivity, but its desorption temperature is high, and regeneration consumes a lot of energy. Regarding the renewal and recycling of adsorbent materials in the process of adsorbing carbon dioxide by the adsorption method, the adsorption process generally includes the following: temperature swing adsorption (TSA), regenerative pressure swing adsorption (PSA), and electric swing adsorption (ESA). TSA relies on temperature changes to achieve carbon dioxide adsorption separation and regeneration of adsorbent materials and relies on pressure changes to achieve carbon dioxide separation and adsorption materials, while PSA and ESA change the coupling effect of temperature and pressure, as shown in Table 1.

Pressure swing adsorption technology is a fixed-bed separation technology. The separation or purification of carbon dioxide and the regeneration of adsorption materials are carried out by changing the adsorption pressure under constant temperature conditions. Generally speaking, at the same temperature, the equilibrium adsorption capacity increases as the pressure increases; when the pressure decreases, the equilibrium adsorption capacity also decreases. Therefore, adsorption can be carried out at high pressure, and desorption can be carried out at low pressure. Pressure swing adsorption uses periodic pressure changes to make the adsorption material adsorb and separate carbon dioxide, this is pressure swing adsorption (Liu et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2017; Wawrzyńczak et al., 2019). The general pressure swing adsorption operation process indicates high-pressure adsorption and atmospheric desorption. Nowadays, vacuum pressure swing has been developed, which means adsorption under normal pressure or slightly higher than normal pressure and desorption under vacuum conditions. Pressure swing adsorption achieves adsorption and desorption by periodically changing the pressure,, including adsorption at high pressure, and then achieves desorption by reducing the pressure or vacuuming. Electric swing adsorption is to directly heat the adsorbent particles to increase the temperature, so as to achieve the purpose of desorption. This method has the advantages of fast desorption speed and high energy utilization, but this method usually requires the adsorbent material to have good conductivity (Grande et al., 2009; Grande et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2018). Under certain conditions, the adsorbent selectively adsorbs CO2 in the flue gas. It then changes certain conditions (such as temperature, pressure, etc. ) to desorb CO2 from the adsorbent to achieve the purpose of CO2 separation. Rigid solid adsorbent materials capture gas molecules through physical adsorption and are one of the most potential carbon dioxide capture and separation candidates..

The temperature swing adsorption is simple to operate and easy to implement, but it has higher requirements for the thermal conductivity of the adsorbent material. Temperature swing adsorption relies on the characteristic that the adsorption capacity of carbon dioxide changes with temperature. Under normal circumstances, when the temperature is at the same pressure, the lower the temperature, the equilibrium adsorption capacity increases as the temperature decreases; when the temperature increases, the equilibrium adsorption capacity decreases. Therefore, it can be adsorbed at low temperature and desorbed at high temperatures. The adsorption material can be circulated to adsorb and separate carbon dioxide through periodic temperature changes, demonstrating temperature swing adsorption (Zhao et al., 2019). When capturing carbon dioxide in flue gas, for some adsorption materials with a strong affinity for carbon dioxide, it is challenging to complete the regeneration of the adsorption material if only by changing the pressure. Therefore, temperature swing adsorption is required. There are two types of temperature swing adsorption. One is to use a heating medium to heat, such as purging the adsorption material with high-temperature inert gas, or using the adsorption material’s resistance for electrical heating, and the other is indirect heating, such as the use of coils, jackets, etc. Generally speaking, temperature swing adsorption products have a high recovery rate and low loss. Still, the cycle is long, the investment is enormous, the energy consumption is high, and the service life of the adsorbent is not long. The pressure swing adsorption cycle is short and the adsorbent utilization rate is high, but the recovery rate is low. Therefore, the independent use of temperature or pressure swing methods to recycle molecular sieves has certain defects (Choi et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2018).

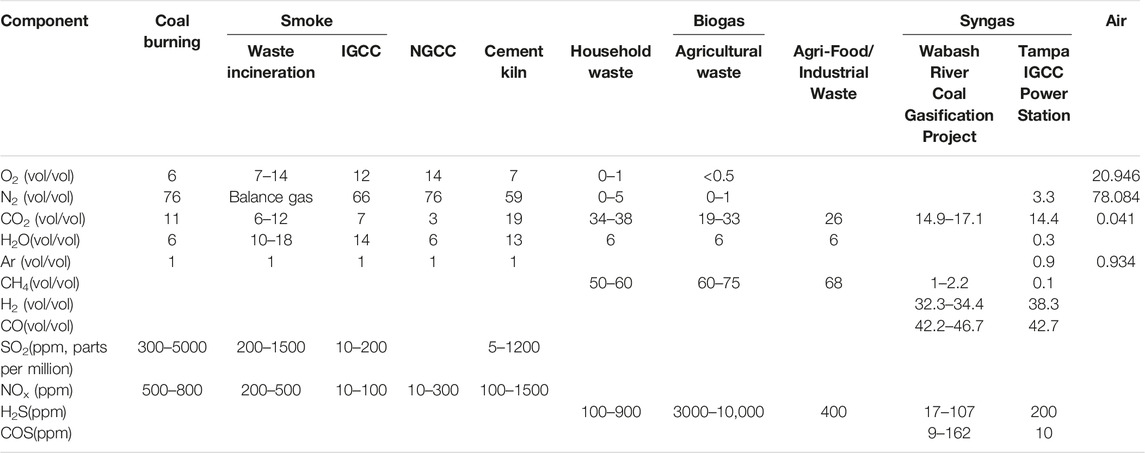

Table 2 lists the main carbon emission sources to which adsorption methods can be applied. Traditional post-combustion carbon capture is the process of separating CO2 from the flue gas formed after the combustion of fuel and air. Among them, the type of fuel and excess air coefficient determine the total gas volume and dry basis CO2 concentration of flue gas, ranging from 3% to 4% of natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) to pulverized coal boiler power station and integrated coal gasification combined cycle (IGCC) ranging from 14%. Pre-combustion carbon capture requires the conversion of fuel (coal, heavy oil, residual carbon, etc.) into syngas or reformed gas through steam reforming or partial oxidation, decarbonization, and combustion in a gas turbine to generate electricity, or CO through water-gas shift (WGS) reaction into CO2 and H2, followed by decarbonization. For the latter case, the CO2 concentration in the shift gas can be as high as 60%, so it is easier to separate CO2 and simultaneously obtain high-purity H2 as an energy carrier or chemical raw material. It should be noted, however, that the initial fuel gasification/reforming process is expensive to operate. In addition to the above two typical capture technologies, adsorption methods can also be applied to carbon capture from emission sources such as steel mills, cement plants, biogas, and flare gas. Recently, adsorption-based direct air capture (DAC) has also received more and more attention as a potential negative emission technology.

TABLE 2. Main emission sources of common adsorption carbon capture (Jahandar Lashaki et al., 2019).

The adsorption method to capture carbon dioxide has the outstanding advantages of simple process, mild operating conditions, extensive operating flexibility, sizeable operating temperature range, low operating cost, stable performance, and no corrosion and pollution, suggesting a carbon dioxide capture method with excellent development potential. The post-combustion capture process of flue gas is characterized by its high temperature, atmospheric pressure, and low CO2 concentration. Therefore, the physical adsorption method greatly affected by the CO2 concentration cannot effectively separate CO2. In contrast, the solvent absorption method requires the gas to be cooled to a specific temperature first, which has a significant energy loss and high energy consumption for regeneration of the absorption solvent. It is corrosive to equipment (Rochelle, 2009). If a solid adsorbent is used to capture CO2 in this temperature range, the above problems can be effectively avoided.

3 Research Direction of CO2 on Porous Adsorption Materials

3.1 Specific Surface Area of the Porous Adsorbent

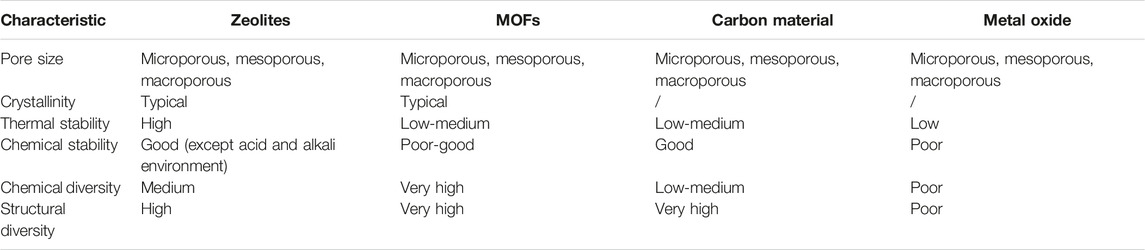

To continuously meet the demand for a high specific surface area of adsorbent materials, under the inspiration of nature, researchers have designed and synthesized a wealth of porous materials, which has promoted the rapid development of porous materials. In order to facilitate the study and discussion of it, according to the composition of the porous material framework, the carbon dioxide porous adsorbent materials are roughly divided into two categories: 1) inorganic porous materials, such as zeolites, mesoporous silica, and metal oxide and 2) inorganic-organic hybrid porous materials, such as metal organic frameworks (MOFs) (Xu et al., 2016; Senker, 2018; Zhao et al., 2020). These two types of materials have different structural characteristics and therefore have distinct material properties. The comparison of their properties is shown in Table 3. It can be seen that although the pore size and crystal type of the two porous adsorption materials are more common, the chemical stability and thermal stability are still quite different, which limits their application environment (including temperature and pH, etc.). MOFs materials are more diverse in chemistry and structure than zeolite.

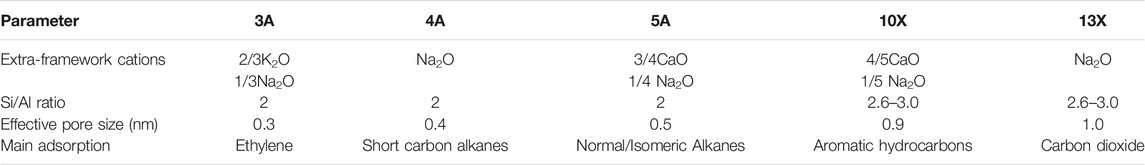

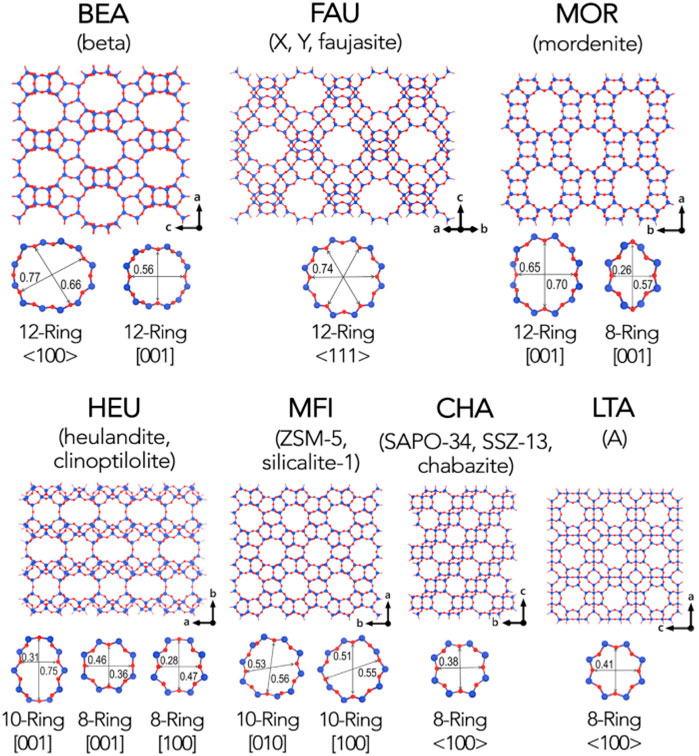

Zeolite is an aluminosilicate with a porous crystal structure and a TO4 (T is Si or Al) tetrahedral periodic structure. Its unique molecular sieve effect is widely used in gas separation processes. In the framework of a molecular sieve, primary structural units such as silicon-oxygen tetrahedron (SiO4) and aluminum-oxygen tetrahedron (AlO4) combine to form a variety of multi-ring secondary structural units through shared oxygen atoms (Figure 3). Oxygen bridge bonds connect the multiple rings to form molecular sieve materials with different types of three-dimensional network structures (Li et al., 2017). The most classic molecular sieve structures are LTA and FAU. As a typical physical adsorbent material, zeolite has a robust electrostatic force between carbon dioxide molecules and alkali metal ions in the process of CO2 capture (Krishna and Van Baten, 2007), the adsorption rate of carbon dioxide is very speedy, and it often reaches saturation within a few minutes. Zeolite has a unique pore structure, and the inside of the crystal has a specific electrostatic force and dispersion force, which gives zeolite selective adsorption characteristics (Krishna and van Baten, 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). However, its adsorption performance is affected by adsorption temperature and pressure. As the adsorption temperature increases, the CO2 adsorption capacity of the zeolite decreases, and as the CO2 partial pressure increases, the CO2 adsorption capacity of the zeolite increases. As shown in Table 4, molecular sieves can be divided into A-type molecular sieves, X-type molecular sieves, Y-type molecular sieves, ZSM series molecular sieves (Siriwardane et al., 2001), and so on, according to the crystal framework structure of molecular sieves. Among these molecular sieves, A-type, X-type and Y-type molecular sieves are the most used for carbon dioxide adsorption.

FIGURE 3. Common framework types of zeolite molecular sieve (Li et al., 2017). The blue sphere represents the T atom, and the red sphere represents the oxygen atom.

In addition, the strong cation exchange properties make zeolite easy to modify, and the cost of zeolite is low, which is very suitable for large-scale production applications (Thang et al., 2014). Pham et al. (Pham et al., 2016) studied the CO2 capture performance of synthetic nano-zeolites by temperature swing adsorption (TSA). The results show that under the conditions of 20°C and 1bar, the adsorption capacity of nano-zeolite for CO2 is 4.81 mmol/g. Using ideal adsorption solution theory (IAST), the selective adsorption of nano-zeolite is calculated to be 18.65. The CO2 removal rate was maintained above 88% through ten cycles of adsorption-desorption regeneration experiments. Zeolite has strong hydrophilicity, and the apparent decrease of CO2 adsorption performance under humid conditions limits its further development. In zeolite materials, factors such as the composition and structure of the framework, the replacement of cations, the purity of the zeolite, the size and distribution of the pore size and other factors will affect the adsorption performance of the zeolite molecular sieve to adsorb carbon dioxide.

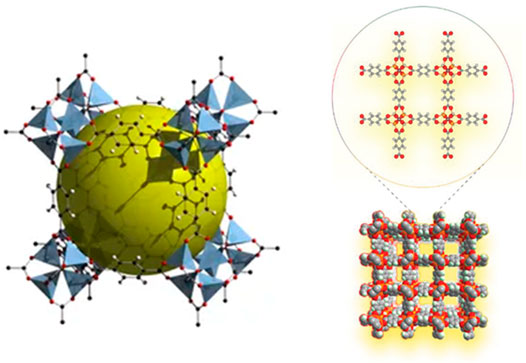

Although zeolite molecular sieves have a high specific surface area and uniform pore structure, their poor framework controllability and difficult control during the synthesis process restrict their development. In order to make up for its shortcomings and play its strengths, after continuous exploration and research, a major challenge has been completed in the synthesis of solid crystalline materials. Without changing the topological structure of the material, the chemical composition, functionality, and pore size of the material are systematically controlled. Yaghi’s research group first proposed the concept of MOFs and synthesized the landmark new porous material MOF-5 (Figure 4) (Li et al., 1999). This type of porous material connects metal ions and organic carboxylate ligands through coordination bonds to form a network structure. They have a high specific surface area and porosity, excellent controllability, and easy functionalization (Shen et al., 2021a). By selecting different metal ions and a variety of organic ligands, adjusting the ratio between the metal and the ligand, and using appropriate synthesis methods, MOFs with varying pore characteristics can be obtained. The research group represented by Yaghi (Li et al., 1999; Furukawa et al., 2010) systematically studied the structure of MOFs and their CO2 adsorption behavior. Among them, the M-MOF-74 series (Caskey et al., 2008) has superior selective adsorption capacity for CO2; Williams et al. The adsorption capacity of HKUST-l [38] for CO2 under normal temperature and pressure can reach 4.1 mmol/g. Matzger et al. prepared Mg-MOF-77 with a two-dimensional hexagonal pore structure and exposed metal nodes. The gas adsorption test showed that under 296 K and 1bar conditions, the saturated adsorption capacity of CO2 reached 8.0 mmol/g (Chui et al., 1999). Britt et al. tested the CO2 adsorption and separation performance of Mg-MOF-77 under dynamic breakthrough conditions, and found that the saturated adsorption capacity still reached 2.0 mmol/g, and showed excellent CO2/CH4 separation performance (Britt et al., 2009). In recent years, people have conducted continuous research and improvement on the synthesis method of MOFs. Currently, the procedures for synthesizing MOFs include the solvent method (Zulys et al., 2020), microwave synthesis method (Jhung et al., 2005), and reagent-free-mechanochemical synthesis method (Pichon et al., 2006). MOFs’ rich and diverse structure makes these materials widely used in gas adsorption and storage, separation, catalysis, and sensing (Rosi et al., 2003; Horcajada et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014; Cadiau et al., 2016). Among the many reported MOFs, the metal-organic framework material MOF-74, due to its strong adsorption force between the unsaturated metal sites and CO2, is currently a hot spot in the field of CO2 adsorption and separation (among which Mg-MOF-74, the CO2 adsorption capacity at 298 K and 1bar is as high as 8.3 mmol/g (Caskey et al., 2008). Table 5 compares the CO2 adsorption performance of the more common metal-organic framework materials under low pressure. It can be seen that the metal organic framework material Mg-MOF-74 has better CO2 adsorption performance under low pressure.

FIGURE 4. MOF-5 three-dimensional structure diagram (Li et al., 1999; Xie et al., 2022).

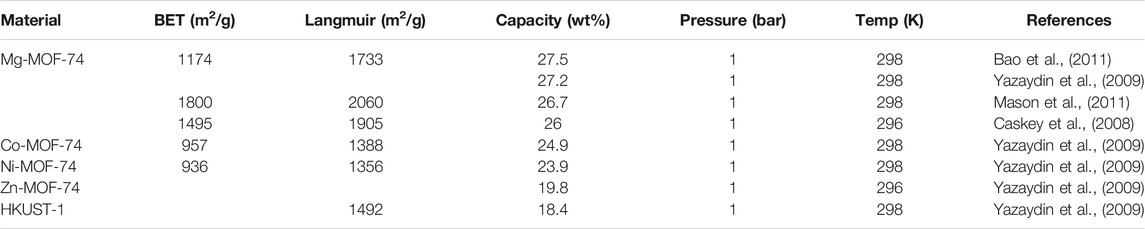

TABLE 5. Comparison of CO2 adsorption performance of common adsorbent materials under low pressure (Li et al., 2020b).

The pore size of the mesoporous silica material is between 2 nm and 50 nm. Mesoporous silica materials mainly include silica nanoparticles, silica hollow spheres, silica nanotubes, mesoporous silica foams and aerogels. Mesoporous silica has the advantages of high specific surface area, large pore volume, narrow pore size distribution, and good regeneration stability. It has also made significant progress in CO2 capture The widely used mesoporous silica (Sharp et al., 2021), including MCM-41, SBA-15 and KIT-6 series, can successfully separate CO2 from the mixture of CH4 and N2. However, the hydrothermal stability of mesoporous silica is low, which is due to the easy hydrolysis of Si-O-Si in the presence of water vapor at high temperatures (Rafigh and Heydarinasab, 2017). Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2019) used the silicate supernatant extracted from the alkali melt as the raw material, and used the addition polymer of polypropylene glycol and ethylene oxide (polyether) P123 and trimethylbenzene (TMB) was used as the structure orientation. Agent and swelling agent, mesoporous silica foam materials were prepared under acidic conditions. The study found that the CO2 adsorption capacity can reach 4.7 mmol/g at 75°C and 1bar.

3.2 Adsorption Selectivity

The CO2 molecule has a large quadrupole moment and a high polarization rate (29.11 × 10−25 cm3), so the polar surface of the porous adsorbent has a strong inducing effect on CO2 and has a large affinity. With the deepening of the understanding of the structure and chemical properties of ZIFs materials, researchers began to explore the relationship between CO2 adsorption and separation performance and structure. Banerjee et al. (Banerjee et al., 2009) used a series of materials with different pore structure parameters and surface polarities (ZIF−68, −69, −70, −78, −79, −80, −81, −82) as the research object. The effects of pore size, specific surface area and surface groups on the CO2 adsorption capacity and selectivity were analyzed. They found that the amount of CO2 adsorbed at low pressure is directly related to the polarity of the surface groups. ZIF-78 (−NO2) and ZIF-82 (−CN) with strong polar groups show better selectivity than other ZIFs. This is because the strongly polar group exhibits a strong dipole motion, which has a stronger dipole quadrupole interaction with the CO2 molecule, thereby enhancing the affinity for the pair and exhibiting better selectivity. Morris et al. (Morris et al., 2010) conducted experiments and grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations on a set of ZIFs with the same topological structure. The two methods verified the surface polarity and the configuration of nitrogen-containing groups and the electrons between CO2 molecules. The attraction has a decisive effect on the adsorption capacity of low-pressure CO2.

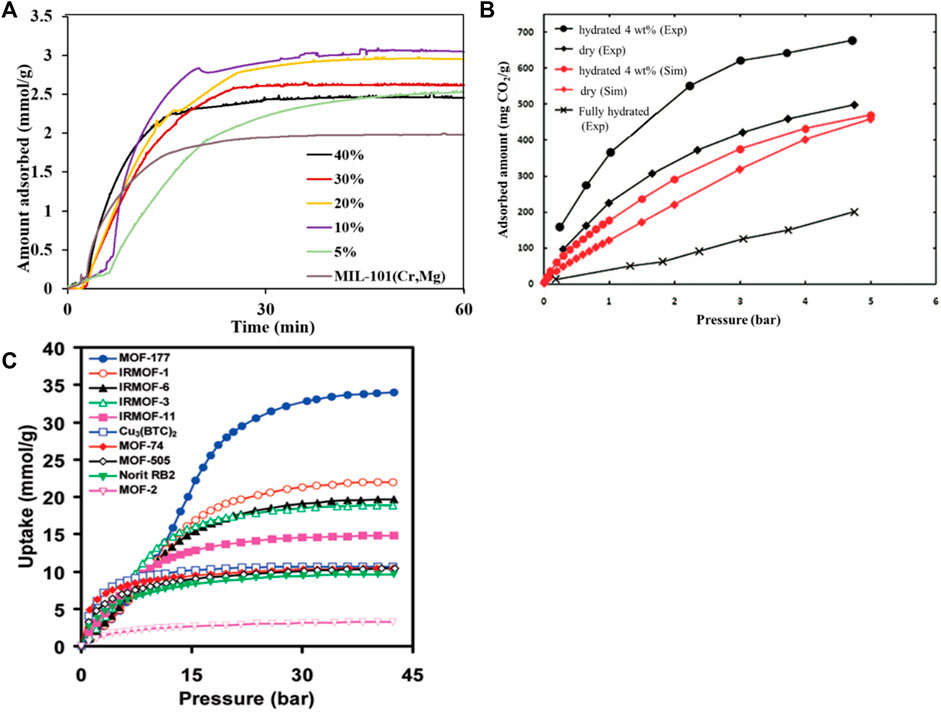

Traditional physical adsorbents such as activated carbon and molecular sieves have small adsorption capacity, low selectivity, and sensitivity to adsorption temperature. MOFs have the characteristics of good selectivity, easy regeneration, high thermal and chemical stability, large specific surface (up to 7000 m2/g), large pore volume (55–90%), and low density (0.21–1 g/cm3)). Their pore structure is regular and adjustable, and the organic ligands can be modified to design and synthesize crystalline materials with specific physical properties and chemical functions (Li et al., 2009). Gaikwad et al. (Gaikwad et al., 2019) synthesized a series of MIL-101 (Cr, Mg) adsorbents with different polyethyleneimine (PEI) loadings, as shown in Figure 5A. The study found that although the specific surface area and total pore volume of MIL-101 (Cr, Mg) decreased significantly with the increase of PEI loading, the MIL-101 (Cr, Mg) adsorbent showed significant performance under low pressure (Giménez-Marqués et al., 2019; Chanut et al., 2020). At 25°C and 1bar, when the PEI loading is 20 wt%, the CO2 adsorption capacity of the adsorbent can reach 3 mmol/g. It is generally believed that in water vapor, the CO2 adsorption capacity and selectivity of the metal-organic framework will decrease because water molecules will compete with CO2 for adsorption sites (Liu et al., 2010). However, Snurr et al. (Yazaydın et al., 2009) synthesized a new type of metal-organic framework HKUST-1, and performed CO2 adsorption experiments on it when the mixed flue gas contained 4 vol% water vapor. As shown in Figure 5B, it is found that unlike other metal-organic frameworks, water vapor increases the CO2 adsorption capacity. Millward et al. (Millward and Yaghi, 2005) reported that under a pressure of 3.5 MPa, with MOF-177 as the adsorbent, the highest carbon dioxide adsorption capacity was as high as 33.5 mmol/g, as shown in Figure 5C. Subsequently, the water molecules and the open metal sites of the framework material are coordinated and complex. Therefore, the selectivity of the Cu-BTC organic framework material to CO2 is significantly improved. The current research results show that metal organic frameworks can adsorb carbon dioxide with a strong quadrupole moment by selecting metal clusters with strong interactions with carbon dioxide or selecting different nodes to construct different pore sizes. In addition, the CO2 adsorption capacity of MOFs can be increased by modification. However, the adsorption capacity is very low under high temperature and humidity, which limits its industrial application. To obtain a metal framework with a high adsorption capacity in a humid environment, further research and exploration are needed.

FIGURE 5. The selective absorption of CO2 by MOFs: (A) the effect of PEI loading on the adsorption selectivity of MIL-101 (Cr, Mg) adsorbent (Gaikwad et al., 2019); (B)the adsorption selectivity of HKUST-1 for CO2/H2O (Yazaydın et al., 2009) ((C) the adsorption properties of MOF-177 and Cu-BTC under different pressures (Millward and Yaghi, 2005).

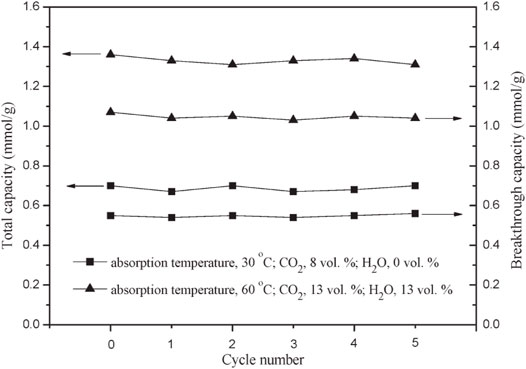

Metal oxides separate carbon dioxide from mixed gases by reacting with CO2 molecules. Common metal oxide materials mainly include calcium oxide, magnesium oxide, lithium zirconate/lithium silicate, and other materials. Carbon dioxide is an acid gas, which is easier to adsorb on the basic sites of metal oxides. Therefore, metal oxide adsorbents have high adsorption capacity, good selectivity, vast sources, and low cost. MgO and CaO are alkaline adsorbents, and their adsorption mechanism is usually the acid-base neutralization reaction with the acid gas CO2 to form carbonate (Li et al., 2005; Shen and Zhang, 2020). Among them, the MgO-based adsorbent has a higher theoretical adsorption capacity, about 1.1 g⋅g−1, and is considered an ideal medium temperature CO2 adsorbent. However, in practical applications, the adsorption rate of MgO-based adsorbents is slow, the actual adsorption capacity is low, generally lower than 0.01 g⋅g−1, and the cycle stability is poor. These problems limit the industrial use of MgO-based adsorbents. The extensive application of the above (Wang et al., 2011). In order to increase the adsorption capacity of MgO-based adsorbents, researchers used a loading method with porous alumina, activated carbon, and mesoporous silica as carriers (Gu et al., 2010; Han et al., 2014; Hanif et al., 2016) to increase the adsorption capacity to 0.085 g⋅g−1. For example, CaO reacts with CO2 to form CaCO3 under certain conditions. This method fixes CO2 through chemical reaction has the advantages of high selectivity and large adsorption capacity, so it has quickly become a research hotspot. Li et al. (Li et al., 2010) prepared MgO/Al2O3 adsorbent and studied its performance in low-temperature capture of CO2 on a fixed bed. The results show that when the MgO loading is 10 wt%, the MgO/Al2O3 adsorbent has the largest CO2 adsorption capacity. And as the water vapor concentration increases, the CO2 capture capacity of the adsorbent first increases and then decreases. As shown in Figure 6, when the adsorption temperature is 60°C and the concentration of CO2 and water vapor are 13 vol%, the CO2 adsorption capacity of the adsorbent reaches its peak value, which is 1.36 mmol/g. In addition, after five regeneration experiments, it was found that the adsorption performance of the adsorbent remained stable. However, metal oxides as CO2 capture materials also have obvious defects, such as high adsorption temperature (the adsorption temperature of CaO is above 450°C (Nie et al., 2017), low adsorption capacity (the adsorption capacity of CO2 is 0.5 mmol/g at 450°C and 20 bar (Hassanzadeh and Abbasian, 2010)), and slow adsorption rate [the lithium-based oxide needs 2 days to reach adsorption saturation at 600 °C (Ida et al., 2004)]. The high regeneration energy consumption is high [the degassing temperature is above 250°C (Harada et al., 2015)]. In short, a chemical adsorbent that uses a chemical reaction between adsorbent and carbon dioxide has the advantages of large CO2 adsorption capacity and good selectivity to carbon dioxide, but it also has the disadvantages of difficult desorption and high energy consumption for regeneration.

FIGURE 6. Carbon dioxide’s total capacity and breakthrough capacity on the MgO/Al2O3 adsorbent in the presence and absence of water vapor in multiple absorption/desorption cycles (Li et al., 2010). The pressure is 1 bar, the flow rate is 80 ml/min, the balance gas is N2, the regeneration temperature is 350°C, and the amount of MgO/Al2O3 adsorbent is 7.2 g.

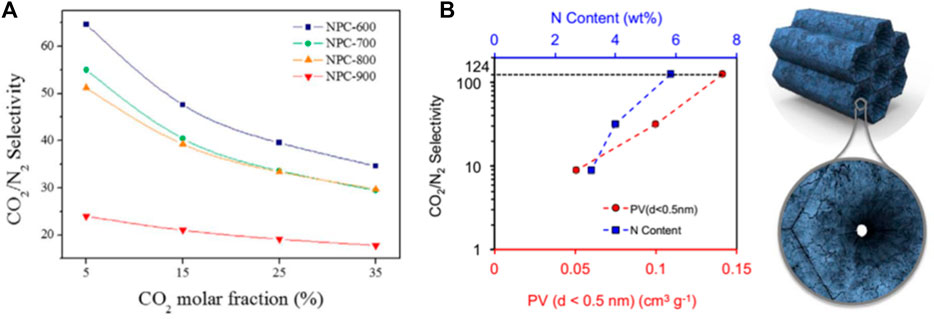

The polar surface of the CO2 adsorption material is another important factor that affects the CO2 adsorption performance, especially the type and quantity of nitrogen-containing groups in the carbonaceous adsorption material. Surface functionalization methods of porous carbon materials include two types (Li et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020c): 1) utilization of functionalized precursors (such as nitrogen-rich compounds) to obtain heteroatom-doped porous carbon in one step and 2) post-treatment to introduce specific functional groups. In terms of stability, the former has outstanding advantages. The surface modified by nitrogen functional groups have a solid inducing effect on CO2 molecules, and strong interaction with them, which enhances the selective recognition of CO2 molecules and improves the CO2 adsorption capacity of the material. Lee et al. (Lee et al., 2016) discussed the effect of nitrogen content on the CO2/N2 separation performance of pitch-based porous carbon, as shown in Figure 7A. Studies have shown that the interaction between strong acids leads to the presence of N elements that is beneficial to CO2 adsorption, and the decrease in nitrogen content will increase the hydrophobicity of N2. Improve the selectivity of CO2/N2. Jennifer and Bao et al. (To et al., 2016) studied the effects of different nitrogen chemical states on the CO2 adsorption capacity and CO2/N2 selectivity of polypyrrole-based carbons, and confirmed that pyrrolic N-5 and pyridonic N-5′ are most conducive to the improvement of CO2 adsorption performance, as shown in Figure 7B. Govind Sethia also got a similar conclusion (Sethia and Sayari, 2015), the ultra-microporous doped nitrogen plays an important role in CO2 adsorption. Doping basic or electron-rich heteroatoms, such as nitrogen, into activated porous carbon frameworks effectively improves the CO2 uptake capacity of adsorbents. Because there are abundant basic sites on the surface that can act as anchors to capture weakly acidic CO2 molecules. In addition, selecting different precursors (such as fruit shell, organic matter, coal-based, etc. ) to prepare porous carbon materials with high specific surface area and rich pore structure can effectively adsorb carbon dioxide molecules in the adsorbent. Using natural plants as raw materials, it has low cost, high electrochemical performance and certain adsorption, and has broad application prospects in the fields of energy and environmental protection. However, the adsorption of CO2 by porous carbon materials is physically-interacted primarily, and the adsorption strength is weak. Therefore, the adsorption performance is sensitive to temperature, and the selectivity is poor. The development of porous carbons with high selectivity and high adsorption capacity or the selection of highly active materials for composites is still the focus of future research.

FIGURE 7. Effect of nitrogen modified carbon-based adsorbent on CO2 selectivity: (A) Nitrogen-containing pitch-based activated carbon (NPC) selectivity as a function of CO2 mole fraction at 298 K and 1 bar total pressure (Lee et al., 2016); (B) The correlation between CO2/N2 selectivity and ultra-small pore volume and the correlation between CO2/N2 selectivity and N content (To et al., 2016).

3.3 Adsorption Stability

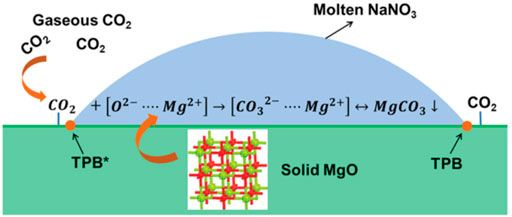

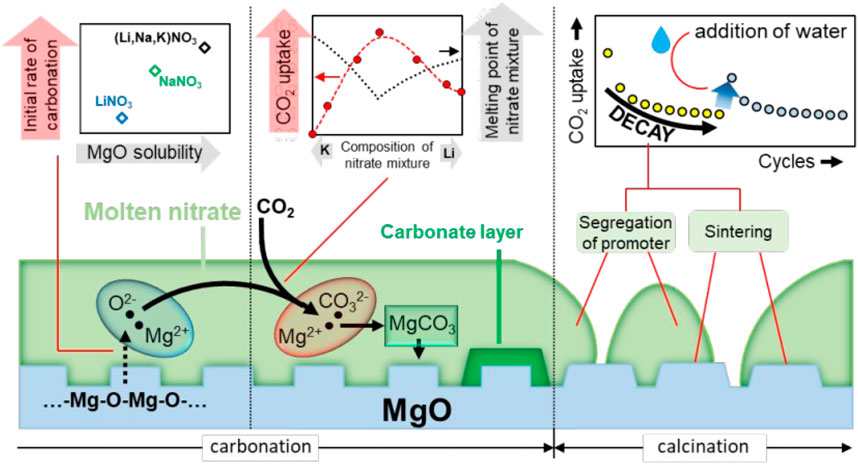

In practical applications, an essential condition for measuring the performance of an adsorption material is its cyclic adsorption performance. After many times of adsorption and desorption, its adsorption performance should not be significantly degraded (Liu et al., 2021). According to analysis, the alkali metal salt is in a molten state at high temperature (350–400°C). It is easy to flow in a wide range, resulting in poor cycle stability of the adsorbent. However, the main challenge of MgO-based adsorbents is that due to their high (Mg2+ - O2-) lattice energy, the actual CO2 adsorption capacity of MgO is very low, and the CO2 adsorption rate is poor. In recent years, studies have shown that modifying MgO with alkali metal carbonate or nitrate can effectively improve its CO2 capture performance. Since the alkali metal nitrate is in a molten state in the medium temperature range (250–500°C), the reason why it promotes the adsorption performance of the MgO-based adsorbent mainly lies in the following two aspects: First, the CO2 in the gas phase is in the molten alkali metal nitrate. There is a certain degree of solubility in nitrate, which can be converted into

FIGURE 8. Molten NaNO3 promotes the CO2 adsorption mechanism of MgO-based adsorbents (Zhang et al., 2014).

Pozzo et al. (Dal Pozzo et al., 2019) studied the mechanism of molten nitrate promoting the adsorption performance of MgO and clarified the reason for the deactivation of the adsorbent material for a long time. Studies have pointed out that the promotion of MgO by molten NaNO3 is mainly the dissolution of MgO in molten alkali metal nitrate, promoting the faster formation of Mg2+. Therefore, the dissolution of MgO in molten alkali metal nitrate is the decisive step in adsorption, as shown in Figure 9. In addition, studies have shown that the adsorption capacity of molten NaNO3 modified MgO adsorbents gradually decreases during the cycle, which is mainly due to the aggregation of molten alkali metal nitrates, resulting in a decrease in the active surface. Based on this, they proposed a method of activating the adsorbent material, the deactivated material is re-dissolved in water and then dried. The alkali metal nitrate on the surface of the adsorbent material is redistributed, and its adsorption performance is also improved.

FIGURE 9. Molten alkali metal nitrate promotes CO2 adsorption by MgO-based adsorbents (Dal Pozzo et al., 2019).

Regarding the stability of porous carbon adsorbents, studies have found that the type and number of nitrogen-containing groups in porous carbon will be affected by the pyrolysis temperature. With the increase in pyrolysis temperature, the number of nitrogen-containing active sites gradually decreased. The nitrogen-containing groups gradually changed from pyrrolic N-5 and pyridonic N-5′ to Quatemary-N (To et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2021). Commonly used nitrogen introducing agents include ammonia, urea, organic amine solutions, etc [65], covering three modification methods of gas, solid and liquid. Przepiórski et al. (Przepiórski et al., 2004) used commercial activated carbon as a raw material, fed ammonia gas at 200–1000 °C and kept it for 2 h to prepare nitrogen-doped activated carbon. The study found that the activated carbon after ammonia heat treatment has stronger CO2 adsorption performance than commercial activated carbon, confirming the effectiveness of ammonia nitrogen incorporation; the adsorbent prepared at 400°C has the largest CO2 adsorption capacity; The poor adsorption performance of samples activated at temperatures above 400°C may be due to the nitrogen-containing functional groups blocking the micropores or changing the pore structure (Shen et al., 2021b). Many scholars have studied the formation mechanism of nitrogen-containing functional groups during high-temperature ammonia treatment. Studies have shown that ammonia gas will decompose into free radicals at high temperatures, such as NH2, NH, hydrogen atoms, and nitrogen atoms. These free radicals are accelerated by Brownian motion at high temperatures and continually collide with carbon atoms to form nitrogen-containing functional groups (Bota and Abotsi, 1994). Karimi et al. (Karimi et al., 2018) mixed commercial activated carbon with urea and activated it at a high temperature of 800°C. The study found that the activated carbon doped with nitrogen via urea has a larger CO2 adsorption capacity than other samples. Keramati et al. (Keramati and Ghoreyshi, 2014) modified commercial activated carbon by immersion in a triethylenetetramine (TETA) solution. The results showed that the amine functionalization of activated carbon significantly improved its CO2 adsorption performance. Under 25°C and 40bar conditions, the maximum CO2 adsorption capacity of the activated carbon adsorbent impregnated with organic amine solution is as high as 16.16 mmol/g, which is 90% higher than the adsorption capacity of the original commercial activated carbon. Various studies have confirmed that urea and organic amine solution doped with nitrogen can significantly improve the common activated carbon adsorbent.

As for MOF materials, the framework of MOFs is formed by connecting metal ions and ligands through coordination bonds. This coordination bond is easily damaged under harsh conditions such as high temperature, humidity, and acid-base environment, resulting in the collapse of the entire skeleton. Metal-organic framework materials Ni-MOF-74 and Co-MOF-74 have higher water stability and hydrophobicity than Mg-MOF-74. Yang et al. (Jiao et al., 2015) compared Mg-MOF-74 doped with Co., or Ni metal through metal doping, compared the effects of doping metal type and doping ratio on the performance of MOF-74, and finally found that when doped with Ni content of 16%, the water stability of the Ni&Mg-MOF-74 framework containing heterogeneous metals is maximized. However, there are few works about the CO2 adsorption performance of metal-doped MOF-74, especially the CO2 adsorption performance under humid conditions. In 2016, Zhai et al. (Zhai et al., 2016) studied the regulation effects of heterogeneous metals Sc/Mg and V/Mg on the adsorption performance and heat of adsorption of MOF-74. The study found that MOF-74 with V and Mg as the metal center is at 273 K. Its CO2 adsorption performance can reach 207.6 cm3/g under the condition of 1bar. In 2017, Joshua et al. (Howe et al., 2017) further studied the effect of Ni or Cd doping on the stability of Mg-MOF-74, and pointed out that the MO bond on the top of M-MOF-74 is the key to the water stability of the material. Among all MO bonds, the top MO bond is the most unstable and most susceptible to the influence of H2O molecules. The doping of metals brings about asymmetric defects in the lattice structure of the skeleton, thereby bringing about contraction of the top M-O bond, enhancing the stability of the M-O bond, and further enhancing the water stability of the skeleton.

Modification of MOF-74 after synthesis is currently the most widely reported modification method in the literature. Chemical solution impregnation is the most common and effective way, such as ammonia impregnation and ethylenediamine solution impregnation. Cao et al. (Cao et al., 2013) used different mass fractions of tetraethylpentamine (TEPA) to modify the metal-organic framework Mg-MOF-74, and explored its effect on CO2 adsorption performance. The breakthrough curve obtained by the test shows that the CO2 adsorption capacity of TEPA-Mg-MOF-74 with appropriate modification amount is increased from 2.67 mmol/g to 6.06 mmol/g compared with Mg-MOF-74, and the CO2 adsorption capacity under humid conditions further increase to 8.31 mmol/g. The cycle stability test showed that the CO2 adsorption capacity of TEPA-Mg-MOF-74 decreased by only 3% after five cycles of absorption and desorption, which indicated that the amino-modified Mg-MOF-74 is a better method after synthesis. Choi et al. (Choi et al., 2012) used ethanediamine (ED) solution to modify Mg-MOF-74 after synthesis. After modification, each unit cell of ED-Mg-MOF-74 contained an ethylenediamine molecule. After four cycles of absorption/desorption, the stability and regeneration capacity of the material are significantly improved, and the CO2 adsorption capacity of the framework material when the CO2 partial pressure is less than 400 ppm (298 K) is also reduced from 1.35 mmol/g before modification, slightly increased to 1.51 mmol/g. In addition, Mcdonald et al. (McDonald et al., 2012) successfully applied the post-synthesis modification method to introduce the dimethylethylenediamine (mmen) group into Mg-MOF-74. They found that the modified mmen-Mg-MOF-74 It has a very high CO2 adsorption capacity under low pressure. At 0.39 mba and 298 K, the CO2 adsorption capacity is 2.38 mmol/g (9.5 wt%), and its isometric heat of adsorption reaches -74 kJ/mol, showing strong adsorption force. In 2017, Su et al. (Su et al., 2017) were based on solution immersion modification and used macromolecular tetraethylpentamine (TEPA) to modify the MOF material Mg-MOF-74 after synthesis. The study found that the TEPA modification combined the framework to the single the adsorption capacity of component CO2 increased from 23.4 wt% to 26.9 wt%. In addition, the CO2 adsorption capacity and adsorption stability of the framework under humid conditions (CO2/H2O mixed gas) have also been significantly improved. It shows that the synergistic effect of the amine functional group and the metal center has a positive effect on the CO2 adsorption capacity of the framework. Although most of the post-synthesis modification studies focus on different kinds of ammonia solution immersion modification, there are other methods. For example, in 2015, Fernandez et al. (Fernandez et al., 2015) impregnated the metal organic framework material Ni-MOF-74 with a chloroform solution (P123), and introduced the hydrophobic group P123 to the outer surface of the Ni-MOF-74 pores by adsorption. The original CO2 adsorption capacity of the framework is retained. In addition, the water stability of the material is significantly improved, and the H2O adsorption capacity is reduced by three times.

In addition to NOX, the flue gas also contains impurities such as water vapor, SOX, OX, and heavy metals. If the adsorbent is not tolerant to these impurities, the overall economics of the CO2 separation process will increase. In general, moisture will adversely affect the CO2 adsorption process of various physical sorbents. The vast majority of reports on physical sorbents have not studied the effect of humidity, so the technology to absorb CO2 from flue gas may include an upstream drying step. It is generally believed that CO2 adsorbents have a high affinity for NOX and SOX, which may adversely affect the CO2 adsorption capacity of the material. Therefore, in most cases, NOX and SO2 need to be removed from the flue gas before CO2 capture.

4 Summary and Outlook

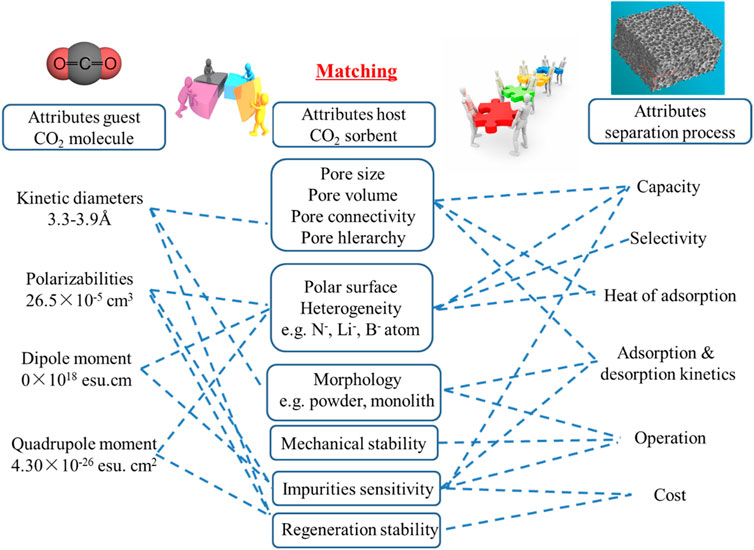

Comprehensive literature reports show that the design of high-efficiency CO2 adsorption materials must match the characteristics of the application object and meet the requirements of the application process. The essential features of CO2 molecules are small dynamic size (approximately 3.3 Å) and electric quadrupole properties

In short, in principle, the physical adsorption process is mainly based on the intermolecular attraction between the guest molecules and the active points on the surface of the porous solid adsorbent, which is a surface process. From the perspective of adsorption effect, large adsorption capacity, high selectivity, fast adsorption kinetics and excellent cycle stability are the key parameters for maintaining high performance in adsorption separation. Efficient adsorption materials should have abundant micropores (storage space), specific surface chemistry (with strong interaction), short diffusion paths (multi-level pores, small-scale structural units) and excellent structural stability (mechanical properties) good). As mentioned earlier, post-combustion carbon capture technology has the following characteristics: relatively low CO2 partial pressure (3–20 vol%), contains water vapor (1–10 vol%) (White et al., 2003; Demessence et al., 2009), large volume flow, etc., (Yazaydin et al., 2009; Plaza et al., 2010) These conditions require the adsorption material to have strong adsorption capacity, resistance to water vapor and good mechanical properties (wear resistance and powdering resistance) under dynamic low partial pressure conditions.

The monolithic material is a structural material in which the internal framework and the pores are continuous. Common monolithic materials include cordierite, cinnamon dioxide, polymers, and porous carbon materials. They have the following characteristics:

1) The design is flexible, easy to operate, and can meet the needs of the macroscopic appearance of the application.

2) The staggered skeleton and pores form an isotropic microstructure, which can ensure the uniform diffusion of the fluid in all directions;

3) The mass transfer resistance is small, the contact efficiency is high, and the penetration is quick. One of the current research hotspots is designing and preparing functional monolithic porous carbon, which includes explicitly developing a new type of polymerization system or a new type of carbon source, precise control of the pore structure, and surface-oriented functionalization. The design and realization of a series of multi-stage pores is the primary goal of precise pore structure control. CO2 adsorption separation is a process of fluid transmission, diffusion, and storage. The macropores and mesopores in adsorption materials function as the channels for rapid CO2 transmission in this process, ensuring rapid adsorption kinetics. The abundant micropores of the adsorption material can be used as the CO2 storage place ensuring high adsorption capacity. In nature, organisms, ranging from towering trees to small system organizations, generally use multi-level structures as organizational frameworks to complete their life processes, which involve fluid diffusion, transmission, and storage, such as the transmission of water and nutrients in plants. After thousands of years of evolution of the survival of the fittest, the multi-level structure is still the main structural organization form, indicating that the structure has certain advantages, which is also the inspiration for researchers from nature. Given the advantages and disadvantages of various adsorption materials’ structure and performance, as well as inspired by the structure and organization of natural organisms and their fluid transportation and diffusion behavior, it can be concluded that the multi-level pore monolithic structure is an ideal organization structure.

Although porous carbon materials have achieved good adsorption and separation effects, most of them are powder samples, and there are usually problems such as pore blockage during the molding process (Williams, 2001; El Kadib et al., 2009; Lohe et al., 2009). Under the dynamic impact of airflow, the pulverization is severe, which leads to the reduction of adsorption and separation efficiency [99–101]. In addition, most of the currently reported adsorption and separation studies are limited to equilibrium adsorption, which is far from the dynamic penetration conditions in practical applications. In summary, we believe that developing a monolithic material preparation method with a controllable structure and good mechanical properties and the static equilibrium adsorption and dynamic penetration and separation of the obtained adsorbent materials is the areas where current research needs to be strengthened. Based on maintaining the adsorption capacity of the material, improving its mechanical properties is conducive to improving the structural stability of the material during the adsorption process; the comprehensive study of equilibrium adsorption and dynamic penetration can deepen the understanding of the dynamic adsorption separation process. Considering the characteristics of high flow rate and high impact of the air source, the material also needs to have a certain degree of mechanical strength. Most of the current research is focused on improving the adsorption capacity of porous materials, and significant progress has been made. However, the stability of the material structure, especially the stability of the adsorption and separation cycle under dynamic conditions, has not attracted enough attention. Therefore, research on the mechanical strength and the cycle performance in adsorption and separation also needs to be strengthened.

This review discusses the current research progress of porous adsorption materials from the perspective of industrial flue gas carbon capture. After comparing a variety of carbon adsorption materials, including carbon-based materials, zeolites, metal organic framework materials, and metal oxides, it can be found that different adsorbents immobilize CO2 under very different temperatures, pressures, carbon dioxide concentrations, and relative humidity of the gas. Therefore, the choice of adsorbent needs to be determined according to the actual application. The ideal adsorbent needs to meet the following requirements: the higher the carbon dioxide adsorption capacity, the higher the adsorption and desorption rate, the better the cycle stability, the better the mechanical strength, and the lower the preparation cost. There are currently no suitable adsorbent materials to meet the above requirements, and each material has its inherent advantages and disadvantages. When selecting adsorbents, the advantages and disadvantages of various materials should be comprehensively analyzed, and the lowest-cost adsorbent material that meets the CO2 capture requirements should be chosen according to the actual working conditions.

Author Contributions

HZ conceived of the presented idea. HZ, DX, and YL wrote and revised the manuscript. XQ and YL provided the suggestions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by Major Project of Fundamental Research Funds for Universities of Zhejiang Province (FRF20PY005) Innovation and Technology Fund (PRP/067/19AI). Open access funding was provided by Empa - Swiss Federal Laboratories For Materials Science And Technology.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Banerjee, R., Furukawa, H., Britt, D., Knobler, C., O’Keeffe, M., and Yaghi, O. M. (2009). Control of Pore Size and Functionality in Isoreticular Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks and Their Carbon Dioxide Selective Capture Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3875–3877. doi:10.1021/ja809459e

Bao, Z., Yu, L., Ren, Q., Lu, X., and Deng, S. (2011). Adsorption of CO2 and CH4 on a Magnesium-Based Metal Organic Framework. J. colloid interface Sci. 353, 549–556. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2010.09.065

Bota, K. B., and Abotsi, G. M. K. (1994). Ammonia: a Reactive Medium for Catalysed Coal Gasification. Fuel 73, 1354–1357. doi:10.1016/0016-2361(94)90313-1

Britt, D., Furukawa, H., Wang, B., Glover, T. G., and Yaghi, O. M. (2009). Highly Efficient Separation of Carbon Dioxide by a Metal-Organic Framework Replete with Open Metal Sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 20637–20640. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909718106

Bui, M., Adjiman, C. S., Bardow, A., Anthony, E. J., Boston, A., Brown, S., et al. (2018). Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS): the Way Forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1062–1176. doi:10.1039/c7ee02342a

Cadiau, A., Adil, K., Bhatt, P. M., Belmabkhout, Y., and Eddaoudi, M. (2016). A Metal-Organic Framework-Based Splitter for Separating Propylene from Propane. Science 353, 137–140. doi:10.1126/science.aaf6323

Cai, Z., Li, Z., Ravaine, S., He, M., Song, Y., Yin, Y., et al. (2021). From Colloidal Particles to Photonic Crystals: Advances in Self-Assembly and Their Emerging Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 5898–5951. doi:10.1039/d0cs00706d

Cao, Y., Song, F., Zhao, Y., and Zhong, Q. (2013). Capture of Carbon Dioxide from Flue Gas on TEPA-Grafted Metal-Organic Framework Mg2(dobdc). J. Environ. Sci. 25, 2081–2087. doi:10.1016/s1001-0742(12)60267-8

Caskey, S. R., Wong-Foy, A. G., and Matzger, A. J. (2008). Dramatic Tuning of Carbon Dioxide Uptake via Metal Substitution in a Coordination Polymer with Cylindrical Pores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10870–10871. doi:10.1021/ja8036096

Change, I. C. (2014). “Mitigation of Climate Change,” in Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 1454.

Chanut, N., Ghoufi, A., Coulet, M. V., Bourrelly, S., Kuchta, B., Maurin, G., et al. (2020). Tailoring the Separation Properties of Flexible Metal-Organic Frameworks Using Mechanical Pressure. Nat. Commun. 11, 1216–1217. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15036-y

Choi, S., Watanabe, T., Bae, T.-H., Sholl, D. S., and Jones, C. W. (2012). Modification of the Mg/DOBDC MOF with Amines to Enhance CO2 Adsorption from Ultradilute Gases. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 1136–1141. doi:10.1021/jz300328j

Choi, W., Min, K., Kim, C., Ko, Y. S., Jeon, J. W., Seo, H., et al. (2016). Epoxide-functionalization of Polyethyleneimine for Synthesis of Stable Carbon Dioxide Adsorbent in Temperature Swing Adsorption. Nat. Commun. 7, 12640–12648. doi:10.1038/ncomms12640

Chui, S. S.-Y., Lo, S. M.-F., Charmant, J. P. H., Orpen, A. G., and Williams, I. D. (1999). A Chemically Functionalizable Nanoporous Material [Cu 3 (TMA) 2 (H 2 O) 3 ] N. Science 283, 1148–1150. doi:10.1126/science.283.5405.1148

Dal Pozzo, A., Armutlulu, A., Rekhtina, M., Abdala, P. M., and Müller, C. R. (2019). CO2 Uptake and Cyclic Stability of MgO-Based CO2 Sorbents Promoted with Alkali Metal Nitrates and Their Eutectic Mixtures. ACS Appl. Energy Mat. 2, 1295–1307. doi:10.1021/acsaem.8b01852

Davison, J. (2009). Electricity Systems with Near-Zero Emissions of CO2 Based on Wind Energy and Coal Gasification with CCS and Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 3, 683–692. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2009.08.006

Demessence, A., D’Alessandro, D. M., Foo, M. L., and Long, J. R. (2009). Strong CO2 Binding in a Water-Stable, Triazolate-Bridged Metal−Organic Framework Functionalized with Ethylenediamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8784–8786. doi:10.1021/ja903411w

Ebner, A. D., and Ritter, J. A. (2009). State-of-the-art Adsorption and Membrane Separation Processes for Carbon Dioxide Production from Carbon Dioxide Emitting Industries. Sep. Sci. Technol. 44, 1273–1421. doi:10.1080/01496390902733314

El Kadib, A., Chimenton, R., Sachse, A., Fajula, F., Galarneau, A., and Coq, B. (2009). Functionalized Inorganic Monolithic Microreactors for High Productivity in Fine Chemicals Catalytic Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48, 4969–4972. doi:10.1002/anie.200805580

Fernandez, C. A., Nune, S. K., Annapureddy, H. V., Dang, L. X., McGrail, B. P., Zheng, F., et al. (2015). Hydrophobic and Moisture-Stable Metal-Organic Frameworks. Dalton Trans. 44, 13490–13497. doi:10.1039/c5dt00606f

Furukawa, H., Ko, N., Go, Y. B., Aratani, N., Choi, S. B., Choi, E., et al. (2010). Ultrahigh Porosity in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 329, 424–428. doi:10.1126/science.1192160

Gaikwad, S., Kim, S.-J., and Han, S. (2019). CO2 Capture Using Amine-Functionalized Bimetallic MIL-101 MOFs and Their Stability on Exposure to Humid Air and Acid Gases. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 277, 253–260. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.11.001

Gibbins, J., and Chalmers, H. (2008). Carbon Capture and Storage. Energy policy 36, 4317–4322. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.058

Giménez-Marqués, M., Santiago-Portillo, A., Navalón, S., Álvaro, M., Briois, V., Nouar, F., et al. (2019). Exploring the Catalytic Performance of a Series of Bimetallic MIL-100 (Fe, Ni) MOFs. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 20285–20292.

Grande, C. A., Ribeiro, R. P. L., Oliveira, E. L. G., and Rodrigues, A. E. (2009). Electric Swing Adsorption as Emerging CO2 Capture Technique. Energy Procedia 1, 1219–1225. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2009.01.160

Grande, C. A., Ribeiro, R. P. P. L., and Rodrigues, A. E. (2010). Challenges of Electric Swing Adsorption for CO2 Capture. ChemSusChem 3, 892–898. doi:10.1002/cssc.201000059

Gu, F. N., Wei, F., Yang, J. Y., Wang, Y., and Zhu, J. H. (2010). Fabrication of Hierarchical Channel Wall in Al-MCM-41 Mesoporous Materials to Enhance Their Adsorptive Capability: Why and How? J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 8431–8439. doi:10.1021/jp1009143

Han, S. J., Bang, Y., Kwon, H. J., Lee, H. C., Hiremath, V., Song, I. K., et al. (2014). Elevated Temperature CO2 Capture on Nano-Structured MgO-Al2O3 Aerogel: Effect of Mg/Al Molar Ratio. Chem. Eng. J. 242, 357–363. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2013.12.092

Hanif, A., Dasgupta, S., and Nanoti, A. (2016). Facile Synthesis of High-Surface-Area Mesoporous MgO with Excellent High-Temperature CO2 Adsorption Potential. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55, 8070–8078. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.6b00647

Harada, T., Simeon, F., Hamad, E. Z., and Hatton, T. A. (2015). Alkali Metal Nitrate-Promoted High-Capacity MgO Adsorbents for Regenerable CO2Capture at Moderate Temperatures. Chem. Mat. 27, 1943–1949. doi:10.1021/cm503295g

Hassanzadeh, A., and Abbasian, J. (2010). Regenerable MgO-Based Sorbents for High-Temperature CO2 Removal from Syngas: 1. Sorbent Development, Evaluation, and Reaction Modeling. Fuel 89, 1287–1297. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2009.11.017

Haszeldine, R. S. (2009). Carbon Capture and Storage: How Green Can Black Be? Science 325, 1647–1652. doi:10.1126/science.1172246

Horcajada, P., Chalati, T., Serre, C., Gillet, B., Sebrie, C., Baati, T., et al. (2010). Porous Metal-Organic-Framework Nanoscale Carriers as a Potential Platform for Drug Delivery and Imaging. Nat. Mater 9, 172–178. doi:10.1038/nmat2608

Howe, J. D., Morelock, C. R., Jiao, Y., Chapman, K. W., Walton, K. S., and Sholl, D. S. (2017). Understanding Structure, Metal Distribution, and Water Adsorption in Mixed-Metal MOF-74. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 627–635. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b11719

Ida, J.-i., Xiong, R., and Lin, Y. S. (2004). Synthesis and CO2 Sorption Properties of Pure and Modified Lithium Zirconate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 36, 41–51. doi:10.1016/s1383-5866(03)00151-5

IEA, I. (2017). “Energy Technology Perspectives 2017,” in Catalysing Energy Technology Transformations. OECD, 443.

Jahandar Lashaki, M., Khiavi, S., and Sayari, A. (2019). Stability of Amine-Functionalized CO2 Adsorbents: a Multifaceted Puzzle. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 3320–3405. doi:10.1039/c8cs00877a

Jhung, S.-H., Lee, J.-H., and Chang, J.-S. (2005). Microwave Synthesis of a Nanoporous Hybrid Material, Chromium Trimesate. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 26, 880–881.

Jiang, L., Roskilly, A., and Wang, R. (2018). Performance Exploration of Temperature Swing Adsorption Technology for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Energy Convers. Manag. 165, 396–404.

Jiao, Y., Morelock, C. R., Burtch, N. C., Mounfield, W. P., Hungerford, J. T., and Walton, K. S. (2015). Tuning the Kinetic Water Stability and Adsorption Interactions of Mg-MOF-74 by Partial Substitution with Co or Ni. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 12408–12414. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.5b03843

Kanniche, M., Gros-Bonnivard, R., Jaud, P., Valle-Marcos, J., Amann, J.-M., and Bouallou, C. (2010). Pre-combustion, Post-combustion and Oxy-Combustion in Thermal Power Plant for CO2 Capture. Appl. Therm. Eng. 30, 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.05.005

Karimi, M., C. Silva, J. A., Gonçalves, C. N. d. P., L. Diaz de Tuesta, J., Rodrigues, A. E., and Gomes, H. T. (2018). CO2 Capture in Chemically and Thermally Modified Activated Carbons Using Breakthrough Measurements: Experimental and Modeling Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 11154–11166. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.8b00953

Kearns, D., Liu, H., and Consoli, C. (2021). Technology Readiness and Costs of CCS. Brussels, Belgium: Global CCS Institute.

Keramati, M., and Ghoreyshi, A. A. (2014). Improving CO2 Adsorption onto Activated Carbon through Functionalization by Chitosan and Triethylenetetramine. Phys. E Low-Dimensional Syst. Nanostructures 57, 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.physe.2013.10.024

Kniep, J., Sun, Z., Lin, H., Mohammad, M., Thomas-Droz, S., Vu, J., et al. (2017). FIELD TESTS of MTR MEMBRANES for SYNGAS SEPARATIONS: Final Report of CO2-Selective Membrane Field Test Activities at the National Carbon Capture Center. Available at: https://www.nationalcarboncapturecenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Membrane-Technology-and-Research-Field-Tests-of-MTR-CO2-Selective-Membranes-for-Syngas-Separations-2017.pdf.

Krishna, R., and van Baten, J. M. (2020). Using Molecular Simulations for Elucidation of Thermodynamic Nonidealities in Adsorption of CO2-Containing Mixtures in NaX Zeolite. ACS omega 5, 20535–20542. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c02730

Krishna, R., and Van Baten, J. M. (2007). Using Molecular Simulations for Screening of Zeolites for Separation of CO2/CH4 Mixtures. Chem. Eng. J. 133, 121–131. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2007.02.011

Lee, M.-S., Park, M., Kim, H. Y., and Park, S.-J. (2016). Effects of Microporosity and Surface Chemistry on Separation Performances of N-Containing Pitch-Based Activated Carbons for CO 2/N 2 Binary Mixture. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–11. doi:10.1038/srep23224

Leperi, K. T., Chung, Y. G., You, F., and Snurr, R. Q. (2019). Development of a General Evaluation Metric for Rapid Screening of Adsorbent Materials for Postcombustion CO2 Capture. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 11529–11539. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b01418

Lesnikowski, A., Ford, J., Biesbroek, R., Berrang-Ford, L., Maillet, M., Araos, M., et al. (2017). What Does the Paris Agreement Mean for Adaptation? Clim. Policy 17, 825–831. doi:10.1080/14693062.2016.1248889

Li, H., Eddaoudi, M., O'Keeffe, M., and Yaghi, O. M. (1999). Design and Synthesis of an Exceptionally Stable and Highly Porous Metal-Organic Framework. nature 402, 276–279. doi:10.1038/46248

Li, J.-R., Kuppler, R. J., and Zhou, H.-C. (2009). Selective Gas Adsorption and Separation in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477–1504. doi:10.1039/b802426j

Li, J., Bhatt, P. M., Li, J., Eddaoudi, M., and Liu, Y. (2020). Recent Progress on Microfine Design of Metal-Organic Frameworks: Structure Regulation and Gas Sorption and Separation. Adv. Mat. 32, 2002563. doi:10.1002/adma.202002563

Li, L., Wen, X., Fu, X., Wang, F., Zhao, N., Xiao, F., et al. (2010). MgO/Al2O3 Sorbent for CO2 Capture. Energy fuels. 24, 5773–5780. doi:10.1021/ef100817f

Li, Y., Li, L., and Yu, J. (2017). Applications of Zeolites in Sustainable Chemistry. Chem 3, 928–949. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2017.10.009

Li, Z., Jin, J., Yang, F., Song, N., and Yin, Y. (2020). Coupling Magnetic and Plasmonic Anisotropy in Hybrid Nanorods for Mechanochromic Responses. Nat. Commun. 11, 2883–2894. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16678-8

Li, Z.-s., Cai, N.-s., Huang, Y.-y., and Han, H.-j. (2005). Synthesis, Experimental Studies, and Analysis of a New Calcium-Based Carbon Dioxide Absorbent. Energy fuels. 19, 1447–1452. doi:10.1021/ef0496799

Li, Z., Gadipelli, S., Yang, Y., He, G., Guo, J., Li, J., et al. (2019). Exceptional Supercapacitor Performance from Optimized Oxidation of Graphene-Oxide. Energy Storage Mater. 17, 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.ensm.2018.12.006

Li, Z., Yang, F., and Yin, Y. (2020). Smart Materials by Nanoscale Magnetic Assembly. Adv. Funct. Mat. 30, 1903467. doi:10.1002/adfm.201903467

Lin, J.-B., Nguyen, T. T. T., Vaidhyanathan, R., Burner, J., Taylor, J. M., Durekova, H., et al. (2021). A Scalable Metal-Organic Framework as a Durable Physisorbent for Carbon Dioxide Capture. Science 374, 1464–1469. doi:10.1126/science.abi7281

Lipponen, J., McCulloch, S., Keeling, S., Stanley, T., Berghout, N., and Berly, T. (2017). The Politics of Large-Scale CCS Deployment. Energy Procedia 114, 7581–7595. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.1890

Liu, J., Chen, L., Cui, H., Zhang, J., Zhang, L., and Su, C.-Y. (2014). Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks in Heterogeneous Supramolecular Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6011–6061. doi:10.1039/c4cs00094c

Liu, J., Thallapally, P. K., McGrail, B. P., Brown, D. R., and Liu, J. (2012). Progress in Adsorption-Based CO2capture by Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2308–2322. doi:10.1039/c1cs15221a

Liu, Y., He, G., Jiang, H., Parkin, I. P., Shearing, P. R., and Brett, D. J. L. (2021). Cathode Design for Aqueous Rechargeable Multivalent Ion Batteries: Challenges and Opportunities. Adv. Funct. Mat. 31, 2010445. doi:10.1002/adfm.202010445

Liu, Y., Hu, E., Khan, E. A., and Lai, Z. (2010). Synthesis and Characterization of ZIF-69 Membranes and Separation for CO2/CO Mixture. J. Membr. Sci. 353, 36–40.

Liu, Z., Grande, C. A., Li, P., Yu, J., and Rodrigues, A. E. (2011). Multi-bed Vacuum Pressure Swing Adsorption for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Flue Gas. Sep. Purif. Technol. 81, 307–317. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2011.07.037

Lohe, M. R., Rose, M., and Kaskel, S. (2009). Metal-organic Framework (MOF) Aerogels with High Micro- and Macroporosity. Chem. Commun. 2009, 6056–6058. doi:10.1039/b910175f

Ma, H., Zhang, Y., and Shen, M. (2021). Application and Prospect of Supercapacitors in Internet of Energy (IOE). J. Energy Storage 44, 103299. doi:10.1016/j.est.2021.103299

Mason, J. A., Sumida, K., Herm, Z. R., Krishna, R., and Long, J. R. (2011). Evaluating Metal-Organic Frameworks for Post-combustion Carbon Dioxide Capture via Temperature Swing Adsorption. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3030–3040. doi:10.1039/c1ee01720a

McDonald, T. M., Lee, W. R., Mason, J. A., Wiers, B. M., Hong, C. S., and Long, J. R. (2012). Capture of Carbon Dioxide from Air and Flue Gas in the Alkylamine-Appended Metal-Organic Framework Mmen-Mg2(dobpdc). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7056–7065. doi:10.1021/ja300034j

Millward, A. R., and Yaghi, O. M. (2005). Metal−Organic Frameworks with Exceptionally High Capacity for Storage of Carbon Dioxide at Room Temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 17998–17999. doi:10.1021/ja0570032

Morris, W., Leung, B., Furukawa, H., Yaghi, O. K., He, N., Hayashi, H., et al. (2010). A Combined Experimental−Computational Investigation of Carbon Dioxide Capture in a Series of Isoreticular Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11006–11008. doi:10.1021/ja104035j

Nie, F., He, D., Guan, J., Zhang, K., Meng, T., and Zhang, Q. (2017). The Influence of Abundant Calcium Oxide Addition on Oil Sand Pyrolysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 155, 216–224. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.06.020

Omodolor, I. S., Otor, H. O., Andonegui, J. A., Allen, B. J., and Alba-Rubio, A. C. (2020). Dual-function Materials for CO2 Capture and Conversion: a Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 17612–17631. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.0c02218

Orr, F. M. (2009). CO2 Capture and Storage: Are We Ready? Energy Environ. Sci. 2, 449–458. doi:10.1039/b822107n

Pardakhti, M., Jafari, T., Tobin, Z., Dutta, B., Moharreri, E., Shemshaki, N. S., et al. (2019). Trends in Solid Adsorbent Materials Development for CO2 Capture. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 11, 34533–34559. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b08487

Pham, T.-H., Lee, B.-K., Kim, J., and Lee, C.-H. (2016). Enhancement of CO2 Capture by Using Synthesized Nano-Zeolite. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 64, 220–226. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.04.026

Pichon, A., Lazuen-Garay, A., and James, S. L. (2006). Solvent-free Synthesis of a Microporous Metal-Organic Framework. CrystEngComm 8, 211–214. doi:10.1039/b513750k

Plaza, M. G., Rubiera, F., Pis, J. J., and Pevida, C. (2010). Ammoxidation of Carbon Materials for CO2 Capture. Appl. Surf. Sci. 256, 6843–6849. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.04.099

Przepiórski, J., Skrodzewicz, M., and Morawski, A. (2004). High Temperature Ammonia Treatment of Activated Carbon for Enhancement of CO2 Adsorption. Appl. Surf. Sci. 225, 235–242.

Rafigh, S. M., and Heydarinasab, A. (2017). Mesoporous Chitosan-SiO2 Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and CO2 Adsorption Capacity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 10379–10386. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b02388

Rochelle, G. T. (2009). Amine Scrubbing for CO 2 Capture. Science 325, 1652–1654. doi:10.1126/science.1176731

Rosi, N. L., Eckert, J., Eddaoudi, M., Vodak, D. T., Kim, J., O'Keeffe, M., et al. (2003). Hydrogen Storage in Microporous Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 300, 1127–1129. doi:10.1126/science.1083440

Sethia, G., and Sayari, A. (2015). Comprehensive Study of Ultra-microporous Nitrogen-Doped Activated Carbon for CO2 Capture. Carbon 93, 68–80. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2015.05.017

Sharp, C. H., Bukowski, B. C., Li, H., Johnson, E. M., Ilic, S., Morris, A. J., et al. (2021). Nanoconfinement and Mass Transport in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 11530–11558. doi:10.1039/D1CS00558H

Shen, M., Ai, F., Ma, H., Xu, H., and Zhang, Y. (2021). Progress and Prospects of Reversible Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Materials. Iscience 24, 103464. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103464

Shen, M., and Zhang, P. (2020). Progress and Challenges of Cathode Contact Layer for Solid Oxide Fuel Cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 45, 33876–33894. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.09.147

Shen, M., Zhang, Y., Xu, H., and Ma, H. (2021). MOFs Based on the Application and Challenges of Perovskite Solar Cells. Iscience 24, 103069. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103069

Shen, Y., Zhou, Y., Li, D., Fu, Q., Zhang, D., and Na, P. (2017). Dual-reflux Pressure Swing Adsorption Process for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Dry Flue Gas. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 65, 55–64. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2017.08.020

Siriwardane, R. V., Shen, M.-S., Fisher, E. P., and Poston, J. A. (2001). Adsorption of CO2 on Molecular Sieves and Activated Carbon. Energy fuels. 15, 279–284. doi:10.1021/ef000241s

Su, X., Bromberg, L., Martis, V., Simeon, F., Huq, A., and Hatton, T. A. (2017). Postsynthetic Functionalization of Mg-MOF-74 with Tetraethylenepentamine: Structural Characterization and Enhanced CO2 Adsorption. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 9, 11299–11306. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b02471

Subha, P. V., Nair, B. N., Hareesh, P., Mohamed, A. P., Yamaguchi, T., Warrier, K. G. K., et al. (2015). CO2 Absorption Studies on Mixed Alkali Orthosilicates Containing Rare-Earth Second-phase Additives. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 5319–5326. doi:10.1021/jp511908t