95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 15 March 2022

Sec. Catalysis and Photocatalysis

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.833784

This article is part of the Research Topic 2021 Highlights from Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Fellows View all 11 articles

Taoran Chen1

Taoran Chen1 Mengqing Li1

Mengqing Li1 Lijuan Shen1

Lijuan Shen1 Maarten B. J. Roeffaers2

Maarten B. J. Roeffaers2 Bo Weng2*

Bo Weng2* Haixia Zhu3

Haixia Zhu3 Zhihui Chen3

Zhihui Chen3 Dan Yu4

Dan Yu4 Xiaoyang Pan5

Xiaoyang Pan5 Min-Quan Yang1*

Min-Quan Yang1* Qingrong Qian1

Qingrong Qian1Metal halide perovskites (MHPs) have been widely investigated for various photocatalytic applications. However, the dual-functional reaction system integrated selective organic oxidation with H2 production over MHPs is rarely reported. Here, we demonstrate for the first time the selective oxidation of aromatic alcohols to aldehydes integrated with hydrogen (H2) evolution over Pt-decorated CsPbBr3. Especially, the functionalization of CsPbBr3 with graphene oxide (GO) further improves the photoactivity of the perovskite catalyst. The optimal amount of CsPbBr3/GO-Pt exhibits an H2 evolution rate of 1,060 μmol g−1 h−1 along with high selectivity (>99%) for benzyl aldehyde generation (1,050 μmol g−1 h−1) under visible light (λ > 400 nm), which is about five times higher than the CsPbBr3-Pt sample. The enhanced activity has been ascribed to two effects induced by the introduction of GO: 1) GO displays a structure-directing role, decreasing the particle size of CsPbBr3 and 2) GO and Pt act as electron reservoirs, extracting the photogenerated electrons and prohibiting the recombination of the electron–hole pairs. This study opens new avenues to utilize metal halide perovskites as dual-functional photocatalysts to perform selective organic transformations and solar fuel production.

The selective oxidation of alcohols to carbonyls represents one of the most important reactions in both the fine chemical industry and laboratory research (Shibuya et al., 2011; Yang and Xu, 2013; Sharma et al., 2016; Xue Yang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018a; Huang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2021); the carbonyl products are widely used intermediates and precursors for the manufacture of perfumes, pharmaceuticals, and dyes (Liu et al., 2015; Agosti et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2021). Generally, the oxidative dehydrogenation of alcohols is carried out in the presence of chemical oxidants such as iodine, manganese, chromium oxide, or molecular oxygen. The utilization of costly and toxic chemical agents not only results in the production of stoichiometric amounts of waste but also often generates overoxidized products (Mallat and Baiker, 2004; Lang et al., 2014; Meng et al., 2018a; Meng et al., 2018b; Kampouri and Stylianou, 2019; Crombie et al., 2021; Shang et al., 2021). Particularly, the removed protons are consumed by the oxidant in these strategies resulting in the loss of a potentially interesting source of hydrogen gas (Han et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). In this respect, if the hydrogen atoms released from the alcohols during oxidation can be converted into H2, that is, combining the dehydrogenation reaction with H2 evolution, it would not only improve the atom economy of the reaction and the added value of the products but also provide a revolutionary technology for H2 production. However, coupling the oxidative dehydrogenation of alcohols with reductive hydrogen production is challenging.

Within this context, the advancement of photocatalytic anaerobic oxidation technology in recent years provides a promising strategy. This approach utilizes photogenerated holes to oxidize organics while employing photoelectrons to reduce the removed protons to produce H2, thus completing the oxidative–reductive coupled reaction (Weng et al., 2016; Han et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2020; Peixian Li et al., 2021). Different from traditional photocatalytic aerobic oxidation, the oxygen-free condition effectively inhibits the consumption of the removed protons to produce water and avoids the formation of strong oxidation radicals (like superoxide radicals), which is favorable for improving the product selectivity. Theoretically, the anaerobic dehydrogenation coupled to H2 evolution is initiated by the oxidation half-reaction to remove protons, which is considered to be a rate-limiting step (Liu et al., 2018b; Wang et al., 2021). As such, to obtain high catalytic efficiency, the efficient separation and migration of holes, that is, the exploration of advanced photocatalytic materials with high hole mobility and long carrier lifetime, to oxidize the organic substrates, is essential.

In recent years, the halide perovskite (ABX3) material has been deemed as a promising new-generation photocatalyst alternative due to its remarkable optoelectronic properties such as a large extinction coefficient and an excellent visible light-harvesting ability (Zhao and Zhu, 2016; Xu et al., 2017; Akkerman et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). Importantly, the halide perovskite with a delocalized energy level exhibits a small hole effective mass (Yuan et al., 2015) and high hole mobility (100 cm2 V−1 s−1), which is hundreds of times higher than traditional semiconductor materials such as TiO2 (Wehrenfennig et al., 2014; Bin Yang et al., 2017). Moreover, the perovskite also shows a long carrier lifetime of tens to hundreds of µs and diffusion length of μm levels, providing more opportunities for the diffusion and utilization of photoinduced holes and electrons (Dong et al., 2015; Bi et al., 2016). In this context, these unique features enable the metal halogen perovskite to be an appealing candidate for the organic conversion-coupled hydrogen production reaction, but the research is still rarely reported so far.

Inspired by the foregoing considerations, we herein fabricate CsPbBr3/GO-Pt composites for photocatalytic coupling redox reaction. In the composite, the CsPbBr3 acts as a photoactive component, while the GO plays an important role in decreasing the particle size of CsPbBr3, together with Pt as electron reservoirs to extract photogenerated electrons and prohibit the recombination of electron–hole pairs. By taking selective anaerobic oxidation of aromatic alcohols as model reactions, the as-prepared CsPbBr3/GO-Pt shows obvious photoactivity for the simultaneous production of aromatic aldehydes and H2. An optimal H2 evolution rate of 1,060 μmol g−1 h−1 along with a benzyl aldehyde production rate of 1,050 μmol g−1 h−1 is realized over the CsPbBr3/1.0% GO-1%Pt composite under visible light irradiation (λ > 400 nm). Mechanism study reveals that the carbon-centered radical serves as a pivotal radical intermediate during the photoredox process.

Cesium bromide (CsBr, 99.999%) and lead bromide (PbBr2, 99.0%) were purchased from Macklin. N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF), toluene, graphite powder, potassium persulfate (K2S2O8), phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5), concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), concentrated nitric acid (HNO3, 65%), hydrogen peroxide solution (H2O2, 30%), potassium permanganate (KMnO4, 99.5%), tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6, 98%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36%), ethanol, acetonitrile, ethyl acetate, acetone, isopropanol, and benzyl alcohol all were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All the chemicals were used as received without further purification.

GO was synthesized from natural graphite powder using a modified Hummers’ method (Hummers and Offeman, 1958; Yang and Xu, 2013). The details are described in the supporting information.

CsPbBr3/GO was synthesized via a well-established anti-solvent precipitation method at room temperature (Huang et al., 2018). In brief, a certain amount of GO (2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 mg) was first dispersed in 10 ml of N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) by ultrasonication. Then, 1 mmol CsBr and 1 mmol PbBr2 were added to the solution. After completely dissolving CsBr and PbBr2, the mixture was added dropwise into 80 ml toluene under vigorous stirring, which generated orange precipitation immediately. After that, the precipitation was centrifuged, washed with toluene three times, and then dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 12 h. The blank CsPbBr3 was prepared by following the same procedure without the addition of GO.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the samples were characterized by using Hitachi 8100. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were recorded using a 200 kV JEOL-2100f transmission electron microscope. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the catalysts were characterized on a Bruker D8 advance X-ray diffractometer operated at 40 kV and 40 mA with Cu Kα radiation in the 2θ ranging from 10° to 80°. UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) were obtained on an Agilent CARY-100 spectrophotometer using 100% BaSO4 as an internal standard. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was recorded on Thermo Fisher (Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+) equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα as the X-ray source. All binding energies were referenced to the C 1s peak at 284.8 eV of surface adventitious carbon. Raman spectra were recorded by using a Thermo Fisher-DXR 2xi with a laser at a wavelength of 532 nm. Photoluminescence (PL) measurements were performed on a spectrophotometer (MS3504i) with an excitation wavelength of 405 nm, and time-resolved PL (TRPL) was recorded by using a photon-counting photomultiplier (PMT) (Pico Quant, PMC-100–1).

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements were performed at room temperature using a Magnettech ESR5000 spectrometer. For EPR measurements, 10 mg sample powders were dispersed in a mixed solution of 0.5 ml CH3CN containing 10 μL benzyl alcohol (BA) and 2 μL 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO). Then, the suspension was injected into a glass capillary, which was further placed in a sealed glass tube under argon (Ar) atmosphere. The sealed glass tube was placed in the microwave cavity of the EPR spectrometer and was irradiated with a 300-W Xe lamp (PLS-SXE 300D, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd.) equipped with a 400-nm cutoff filter during the EPR measurement at room temperature.

All the electrochemical measurements were recorded in a conventional three electrodes cell using a CHI 760E instrument. A platinum wire was used as the counter electrode (CE), and an Ag/AgCl electrode was used as the reference electrode (RE). The electrolyte was ethyl acetate solution containing 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6). The working electrodes were prepared using CsPbBr3 and CPB/1.0% GO samples. Typically, the fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate was first cleaned by ultrasonication in ethanol and then rinsed with deionized water and acetone for half an hour. Then, 10 mg of the catalyst was dispersed in 1 ml of isopropanol to get slurry. After that, 50 µL of the slurry was spread on the conductive surface of the FTO glass and then dried at 60°C for 2 h to improve adhesion. The exposed area of the working electrode was 1 cm2. A 300-W Xe lamp system (PLS-SXE 300D, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd.) equipped with a 400-nm cutoff filter was used as the irradiation source. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were carried out in a frequency range from 1 Hz to 1 MHz. The photocurrent measurement was performed under visible light irradiation (λ > 400 nm) using a 300-W Xenon lamp source (PLS-SXE 300D, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd.).

The photocatalytic H2 evolution integrated with aromatic alcohol oxidation was tested in a quartz reactor. Typically, 10 mg of photocatalyst, 0.2 mmol aromatic alcohol, and 1.0% Pt (H2PtCl6 as a precursor) were added into a quartz reactor containing 3 ml CH3CN (purge with Ar gas for 15 min). Then, the reactor was irradiated by visible light (λ > 400 nm) using a 300 W Xe lamp (PLS-SXE 300D, Beijing Perfect light Technology Co., Ltd.) under continuous stirring. After the reaction, the gas product was analyzed by a gas chromatograph (GC 9790pLus, Fu Li, China, TCD detector, Ar as the carrier gas). Liquid products were analyzed by gas chromatography (Shimadzu GC-2030, FID detector) after centrifuging the suspension at 10,000 rpm to remove the catalyst. The test conditions for the long-time experiment were similar to the aforementioned description, except that the reaction time was extended to 20 h.

The conversion efficiency of aromatic alcohols (A) and selectivity of aldehydes (AD) production were calculated using the following equations:

where C0 is the initial concentration of aromatic alcohols, and CA and CAD are the concentrations of aromatic alcohols and aldehydes measured after the photocatalytic reaction for a specific time, respectively.

The fabrication of the CsPbBr3/GO (denoted as CPB/GO) composite is realized via a simple anti-solvent method by adding GO into the precursor solution of CsPbBr3 (for more details, please refer to the experimental section), as illustrated in Scheme 1. The crystal structures of the CsPbBr3 and CPB/GO composites were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD). As displayed in Supplementary Figure S1A (Supporting Information), for all the as-obtained samples, the main XRD peaks are indexed to the monoclinic CsPbBr3 (JCPDS card NO. 00–018–0,364) (Chen et al., 2021). No GO diffraction peaks were observed in the XRD patterns of the CPB/GO samples because of the low weight content (≤1.5%). Raman analysis in Supplementary Figure S1B shows that the as-prepared GO and CPB/GO composite both display two peaks at 1,599 and 1,360 cm−1, which belong to the typical D and G bands of GO, respectively (Huang et al., 2021). Moreover, an obvious peak at 308 cm−1 assigned to the CsPbBr3 was detected in CsPbBr3 and CPB/GO (Wang et al., 2020), which verifies the formation of the hybrid composite. Supplementary Figure S1C shows the UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) of blank CsPbBr3 and CPB/GO composites. Owing to the addition of GO, the light absorption of CPB/GO composites in the region of visible light (550–800 nm) gradually enhances with the increase in the weight ratios of GO, and the colors of the samples change from yellow to brown (Supplementary Figure S2), which can be attributed to the significant background absorption of GO (Xu et al., 2011). The absorption edges for CsPbBr3 and CPB/GO are around 548 nm, which correlates with the intrinsic absorption of the material (Supplementary Figure S3).

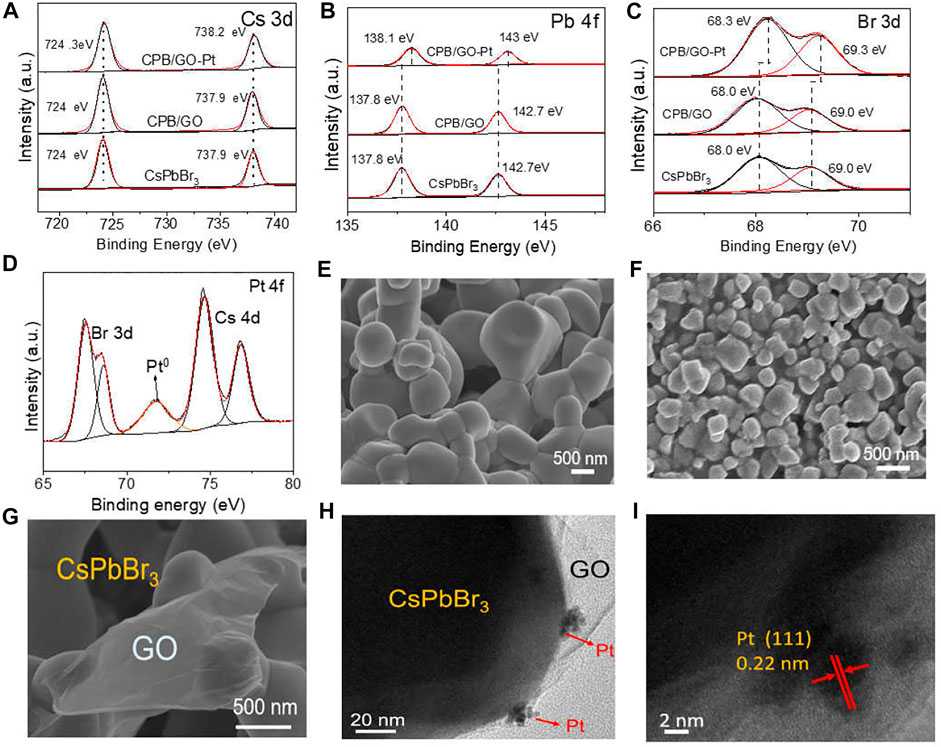

Noble metal Pt nanoparticles are further introduced into the CPB/GO composite for enhancing the catalytic performance. The valence states of different elements have been investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). High-resolution C 1s peaks of CPB/GO and CPB/GO-Pt samples in Supplementary Figure S4 show a C–O bond at 286.6 eV and C=O bond at 287.7 eV, which can be ascribed to the introduction of GO. Figure 1A shows the Cs 3d spectra of blank CsPbBr3, CPB/GO, and CPB/GO-Pt samples. The double peaks of Cs 3d at 724.1 and 738.1 eV are ascribed to Cs+ in CsPbBr3 (Jiang et al., 2020; Liang Li et al., 2021), and no obvious change was observed for blank CsPbBr3 and CPB/GO, while a positive shift was detected for the CPB/GO-Pt sample. This is attributed to the electron transfer from CsPbBr3 to Pt, thus reducing the electron density and altering the coordination environment of Cs. A similar observation can also be made for both the Pb 4f and Br 3d spectra over these samples (Figures 1B, C). The Pt 4f spectrum in Figure 1D exhibited a peak located at 71.6 eV assigned to the Pt0 (Qadir et al., 2012), while another peak is the superposition with the Cs 4d peaks, which suggests that Pt is present in metallic state (Wang et al., 2017). The CsPbBr3/1.0% GO-1%Pt was characterized by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), and the detected mass content of Pt is ca. 0.95% (Supplementary Table S1), closely matching the targeted amount (i.e., 1%).

FIGURE 1. (A) Cs 3d, (B) Pb 4f, (C) Br 3d, and (D) Pt 4f XPS spectra of CsPbBr3, CPB/GO, and CPB/GO-Pt composites; SEM images of (E) blank CsPbBr3 and (F,G) the CPB/GO composite; (H) TEM and (I) HRTEM images of the CPB/GO-Pt composite.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is used to study the morphologic details of blank CsPbBr3, CPB/GO, and CPB/GO-Pt samples (Figures 1E–G and Supplementary Figure S5). The average particle size of the CPB/GO composite is much smaller (0.3–0.5 µm) than that of the blank CsPbBr3 sample (0.8–1.2 µm) (Supplementary Figure S6A). This can be attributed to the fact that GO with abundant functional groups promotes the nucleation process of CsPbBr3, thus producing more seeds and hence leading to the smaller size of final perovskite. The structure-directing role of GO to decrease the size of a semiconductor has been widely reported over graphene-based semiconductor composites (Yang et al., 2014). The enlarged SEM image of the CPB/GO composite in Figure 1G shows an intimate interfacial contact between the GO sheets and the CsPbBr3 particles. The CPB/GO-Pt sample features the same morphology as CPB/GO (Supplementary Figure S5), proving the maintenance of the structure during the Pt modification. This has been further verified by TEM analysis. As shown in Supplementary Figures S6B, C, the TEM image of the CPB/GO composite discloses the fact that the CsPbBr3 particles have been well linked with or wrapped by GO nanosheets, and Cs, Pb, and Br are homogeneously distributed on the C element (Supplementary Figure S6D). Moreover, Figures 1H, I clearly show that the Pt nanoparticles are loaded onto the surface of CsPbBr3 with a lattice fringe of 0.22 nm corresponding to Pt (111), and the size of Pt was calculated to be ca. 3.1 nm (Supplementary Figure S7).

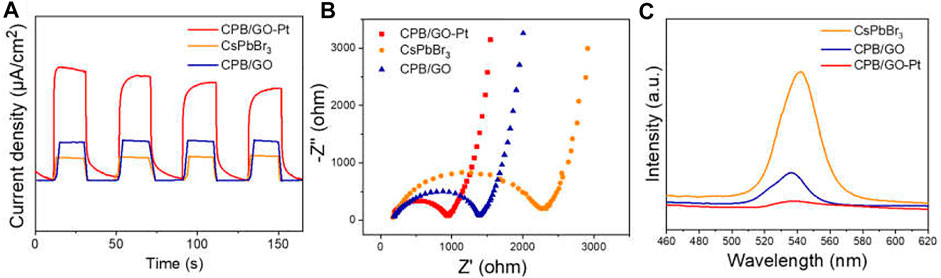

To further study the influence of the introduction of GO and Pt on charge separation and migration, a series of photoelectrochemical characterizations over blank CsPbBr3, CPB/GO, and CPB/GO-Pt composites have been carried out. As shown in Figure 2A, the photocurrent response tests of these samples reveal that the CPB/GO-Pt hybrid composite (taking CPB/1.0% GO-1%Pt with optimal photoactivity as an example) displays higher current density than blank CsPbBr3 and CPB/GO samples, indicating a more efficient separation of the photogenerated carrier (Liao et al., 2021). Figure 2B presents the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) study of these samples, which is employed to study the charge transfer resistance of the samples. The hybrid CPB/GO-Pt shows the smallest arc diameter among these samples, demonstrating a more efficient charge transfer between the electrode and electrolyte solution over CPB/GO-Pt as compared with CsPbBr3 and CPB/GO samples (Lu et al., 2021). This result is consistent with the observation in photocurrent responses tests.

FIGURE 2. (A) Chopped photocurrent responses, (B) Nyquist plots, (C) PL spectra of CsPbBr3, CPB/GO, and CPB/GO-Pt composites.

Moreover, photoluminescence (PL) has been performed to investigate electron–hole recombination. As shown in Figure 2C, blank CsPbBr3 shows a strong emission peak at 546 nm in the PL spectrum upon excitation with 364-nm electromagnetic waves. For CPB/GO and CPB/GO-Pt composites, the PL intensity is significantly quenched since the radiative recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs is diminished due to the electron-accepting nature of GO and Pt (Min-Quan Yang et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021). This is also supported by the time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) decay analysis, as displayed in Supplementary Figure S8 and Supplementary Table S2. The TRPL curve of CPB/GO exhibits a faster decay than that of blank CsPbBr3, which can be attributed to the efficient transfer of photogenerated electrons from CsPbBr3 to GO sheets at a suitable energy level (Xu et al., 2017; Su et al., 2020). The collective photoelectrochemical analyses consolidate that the integration of GO and Pt with CsPbBr3 leads to a more efficient electron–hole separation and rapid charge transfer in the composite, which is critical for boosting the photoactivity (Yang et al., 2019).

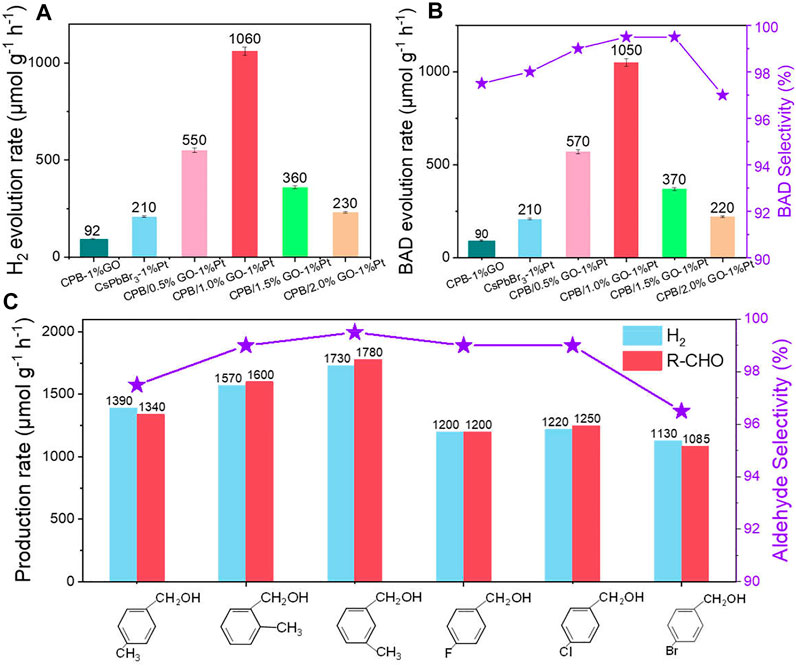

Next, the photocatalytic performances of the samples have been evaluated for the anaerobic photocatalytic oxidation of aromatic alcohols coupled with H2 production under visible light irradiation (λ > 400 nm). Both H2 and BAD are not detected in the dark or without the catalyst, indicating that the reaction is driven by a photocatalytic process (Supplementary Figure S9). The samples of GO and GO-Pt mainly serve as cocatalysts since no products are detected during the photocatalytic reaction process. Moreover, the blank CsPbBr3 cannot produce any products due to the limited reaction kinetics, while the construction of the CPB/1%GO composite leads to low photoactivity toward H2 (90 μmol g−1 h−1) and BAD (94 μmol g−1 h−1) generation. The introduction of Pt into CsPbBr3 improves the catalytic performance, and the production of BAD and H2 are obtained in almost stoichiometric amounts over CsPbBr3-1%Pt, indicating a high selectivity (>99%) of the reaction.

After integration with both GO and Pt, the BAD and H2 evolution efficiencies are further enhanced compared with those of CsPbBr3-1%Pt and CPB/1%GO. In detail, the optimal photoactivity is obtained on the sample of the CPB/1% GO-1%Pt composite (H2 and BAD evolution rates of 1,060 and 1,050 μmol g−1 h−1, respectively), which is about fivefold as high as that of the CsPbBr3-1%Pt sample (Figures 3A,B). This is well in accordance with previous reports stating that loading a suitable amount of GO, which acts as an electron acceptor, with semiconductor photocatalysts can notably improve photoactivity (Chen et al., 2021). Increasing the GO content further to 1.5% resulted in decreased photoactivity. This may be ascribed to the shielding effect of the GO (Yang et al., 2013). On the one hand, the active sites on the surface of CsPbBr3 may be blocked due to the addition of high amounts of GO. On the other hand, GO with black color could also absorb the light, which is competed with CsPbBr3 and inhibits light passing through the depth of the reaction solution.

FIGURE 3. (A) Photocatalytic activity of H2 evolution, (B) BAD evolution and selectivity of CsPbBr3-1%Pt and CPB/x% GO-1%Pt with different weight ratios of GO. (C) The photocatalytic activities for H2 and aldehyde generation of different aromatic alcohols using CPB/1.0% GO-1%Pt as a photocatalyst. Reaction conditions: 10 mg catalyst, 1.0% Pt, 0.2 mmol BA, 3 ml of CH3CN, Ar atmosphere, and visible light (λ > 400 nm).

Based on the high photocatalytic performance of the CPB/1.0% GO-1%Pt, the photocatalytic anaerobic dehydrogenation of a series of aromatic alcohols with different substituents has been tested. As shown in Figure 3C, moderate H2 generation and aldehyde production are obtained for 4-chlorobenzyl alcohol, 4-bromobenzyl alcohol, 4-fluorobenzyl alcohol, 4-methylbenzyl alcohol, 3-methylbenzyl alcohol, and 2-methylbenzyl alcohol. Particularly, for all the substrates bearing electron-donating or electron-withdrawing functional groups, the reactions show high selectivity for aldehyde production (>98%). There is no other byproduct generated during the photocatalytic period, verifying good applicability of the CPB/GO-Pt as a photocatalyst toward solar light–driven integrated organic synthesis and H2 evolution.

To assess the stability of the CPB/GO-Pt composite, a long-term photoactivity test has been carried out. As depicted in Supplementary Figure S10, under continuous irradiation for 20 h, the CPB/1.0% GO-1%Pt photocatalyst shows no obvious deactivation with consistent H2 and BAD production. The composite material manifests excellent stability of the binary composite. In addition, the morphology and crystal structure of the used CPB/1.0% GO-1% Pt have been investigated by SEM (Supplementary Figures S11 and S12) and XRD (Supplementary Figure S13), and no obvious changes between the used and fresh composites were detected. All these aforementioned results are strong evidence for the good stability of the CPB/GO-Pt composite under the used experimental conditions, which is attributed to the mild polarity of acetonitrile and CsPbBr3 substrates that are demonstrated to be stable in this solution (Ou et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021).

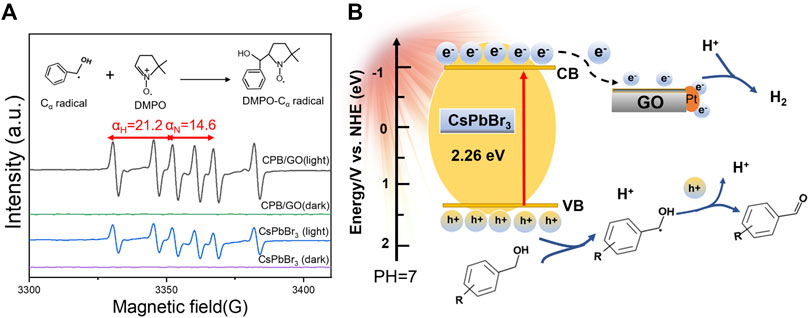

To further study the radical intermediates involved in the catalytic system, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis is performed under visible light using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as a trapping agent. As presented in Figure 4A, there were no free radical signals in the dark. Under light illumination, six characteristic signal peaks were observed for both CsPbBr3 and the CPB/1.0% GO composite, which belongs to the carbon-centered radical adduct (αH = 21.2 and αN = 14.6, corresponding to the hydrogen and nitrogen hyperfine splitting for the nitroxide nitrogen) (Qi et al., 2020). The signal intensity of DMPO-CH(OH)Ph over the CPB/GO composite is stronger than that of blank CsPbBr3, indicating that a larger amount of such carbon-centered radicals was generated in the CPB/GO-catalytic system. This should be ascribed to the enhanced photogenerated charge–transferring ability of CPB/GO in contrast to blank CsPbBr3, which increases their likelihood of interaction with the alcohol substrates. The chemical reaction equations for photocatalytic BA oxidation coupled with H2 generation over CsPbBr3/GO-Pt are presented in Supplementary Figure S14.

FIGURE 4. (A) In situ EPR spectra of CsPbBr3 and CPB/GO composites tested in Ar-saturated CH3CN solution in the presence of DMPO. (B) Schematic illustration of photocatalytic H2 production integrated with aromatic aldehyde synthesis.

On the basis of the aforementioned analyses, a tentative photocatalytic mechanism is proposed for the coupled reaction system toward H2 evolution integrated with the conversion of aromatic alcohols to aromatic aldehydes over the CPB/GO-Pt composite. As displayed in Figure 4B, under the illumination of visible light, CsPbBr3 in the CPB/GO-Pt composite is excited to generate electrons and holes. Owing to the matched energy level and intimate interfacial contact between CsPbBr3 and GO, the electrons tend to migrate from CsPbBr3 to GO and Pt, leaving photoinduced holes in the valence band (VB) of CsPbBr3. Meanwhile, the holes will attack the C–H bond of absorbed BA to generate CH(OH)Ph radicals and protons (Wu et al., 2018). Then, the CH(OH)Ph radicals can be further oxidized to generate BAD and protons. The abstracted protons from BA are reduced to produce H2 by the electrons collected on the surfaces of GO and Pt in the CPB/GO-Pt composite, thus completing the coupled redox reaction.

In summary, we have realized efficient photocatalytic dehydrogenation of aromatic alcohols for simultaneous aldehyde production and H2 evolution over CsPbBr3/GO-Pt composite under visible light (λ > 400 nm). The results show that optimal amounts of CsPbBr3/GO-Pt composite can obtain nearly five times the yield of products (BAD and H2) as high as that of CsPbBr3-Pt. The enhanced photoactivity of CPB/GO-Pt composite is ascribed to the critical roles of GO in tuning the size of CsPbBr3 and together with Pt to extract the photogenerated electrons to boost the migration of photogenerated charge carriers. Furthermore, the carbon-centered radicals have been proven as the pivotal radical intermediate during the photoredox reaction by in situ electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). This work is anticipated to open an avenue for the utilization of halide perovskites as promising candidates in cooperative organic transformation coupling with solar fuel production by the full utilization of photogenerated electrons and holes.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

TC proposed and performed the experiments. ML and LS performed the TEM measurement. ZC and HZ measured the PL and TRPL images. MR, DY, XP, and QQ assisted in designing experiments and manuscript revision. BW and M-QY proposed the research direction and supervised the project. All authors participated in the discussion and reviewed the manuscript before submission.

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21905049, 21902132, 22178057), the Award Program for the Minjiang Scholar Professorship and the Natural Science Foundation of the Fujian Province (2020J01201), the Research Foundation–Flanders (FWO Grant Nos. G.0B39.15, G.0B49.15, G098319N, 1280021N, 12Y7221N, 12Y6418N, VS052320N, and ZW15_09-GOH6316N), the KU Leuven Research Fund (C14/19/079, iBOF-21–085 PERSIST, and C3/19/046), the Flemish government through long term structural funding Methusalem (CASAS2, Meth/15/04), and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 891276.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.833784/full#supplementary-material

Agosti, A., Nakibli, Y., Amirav, L., and Bergamini, G. (2020). Photosynthetic H2 Generation and Organic Transformations with CdSe@CdS-Pt Nanorods for Highly Efficient Solar-To-Chemical Energy Conversion. Nano Energy 70, 104510. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104510

Akkerman, Q. A., Rainò, G., Kovalenko, M. V., and Manna, L. (2018). Genesis, Challenges and Opportunities for Colloidal lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals. Nat. Mater 17 (5), 394–405. doi:10.1038/s41563-018-0018-4

Bi, Y., Hutter, E. M., Fang, Y., Dong, Q., Huang, J., and Savenije, T. J. (2016). Charge Carrier Lifetimes Exceeding 15 μs in Methylammonium Lead Iodide Single Crystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7 (5), 923–928. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00269

Chen, Y.-H., Ye, J.-K., Chang, Y.-J., Liu, T.-W., Chuang, Y.-H., Liu, W.-R., et al. (2021). Mechanisms behind Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction by CsPbBr3 Perovskite-Graphene-Based Nanoheterostructures. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 284, 119751. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119751

Crombie, C. M., Lewis, R. J., Taylor, R. L., Morgan, D. J., Davies, T. E., Folli, A., et al. (2021). Enhanced Selective Oxidation of Benzyl Alcohol via In Situ H2O2 Production over Supported Pd-Based Catalysts. ACS Catal. 11 (5), 2701–2714. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c04586

Dong, Q., Fang, Y., Shao, Y., Mulligan, P., Qiu, J., Cao, L., et al. (2015). Electron-hole Diffusion Lengths > 175 μm in Solution-Grown CH3NH3PbI3 Single Crystals. Science 347 (6225), 967–970. doi:10.1126/science.aaa5760

Han, G., Jin, Y.-H., Burgess, R. A., Dickenson, N. E., Cao, X.-M., and Sun, Y. (2017). Visible-Light-Driven Valorization of Biomass Intermediates Integrated with H2 Production Catalyzed by Ultrathin Ni/CdS Nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (44), 15584–15587. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b08657

Han, G., Liu, X., Cao, Z., and Sun, Y. (2020). Photocatalytic Pinacol C-C Coupling and Jet Fuel Precursor Production on ZnIn2S4 Nanosheets. ACS Catal. 10 (16), 9346–9355. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c01715

Huang, H., Yuan, H., Janssen, K. P. F., Solís-Fernández, G., Wang, Y., Tan, C. Y. X., et al. (2018). Efficient and Selective Photocatalytic Oxidation of Benzylic Alcohols with Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Perovskite Materials. ACS Energ. Lett. 3 (4), 755–759. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.8b00131

Huang, H., Yuan, H., Zhao, J., Solís-Fernández, G., Zhou, C., Seo, J. W., et al. (2019). C(sp3)-H Bond Activation by Perovskite Solar Photocatalyst Cell. ACS Energ. Lett. 4 (1), 203–208. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01698

Huang, H., Pradhan, B., Hofkens, J., Roeffaers, M. B. J., and Steele, J. A. (2020). Solar-Driven Metal Halide Perovskite Photocatalysis: Design, Stability, and Performance. ACS Energ. Lett. 5 (4), 1107–1123. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.0c00058

Huang, Z., Wang, J., Lu, S., Xue, H., Chen, Q., Yang, M.-Q., et al. (2021). Insight into the Real Efficacy of Graphene for Enhancing Photocatalytic Efficiency: A Case Study on CVD Graphene-TiO2 Composites. ACS Appl. Energ. Mater. 4 (9), 8755–8764. doi:10.1021/acsaem.1c00731

Hummers, W. S., and Offeman, R. E. (1958). Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80 (6), 1339. doi:10.1021/ja01539a017

Jiang, Y., Chen, H. Y., Li, J. Y., Liao, J. F., Zhang, H. H., Wang, X. D., et al. (2020). Z‐Scheme 2D/2D Heterojunction of CsPbBr3/Bi2WO6 for Improved Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30 (50), 2004293. doi:10.1002/adfm.202004293

Kampouri, S., and Stylianou, K. C. (2019). Dual-Functional Photocatalysis for Simultaneous Hydrogen Production and Oxidation of Organic Substances. ACS Catal. 9 (5), 4247–4270. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b00332

Lang, X., Ma, W., Chen, C., Ji, H., and Zhao, J. (2014). Selective Aerobic Oxidation Mediated by TiO2 Photocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2), 355–363. doi:10.1021/ar4001108

Li, J., Li, M., Sun, H., Ao, Z., Wang, S., and Liu, S. (2020). Understanding of the Oxidation Behavior of Benzyl Alcohol by Peroxymonosulfate via Carbon Nanotubes Activation. ACS Catal. 10 (6), 3516–3525. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b05273

Li, L., Zhang, Z., Ding, C., and Xu, J. (2021). Boosting Charge Separation and Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction of CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots by Hybridizing with P3HT. Chem. Eng. J. 419, 129543. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.129543

Li, P., Yan, X., Gao, S., and Cao, R. (2021). Boosting Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production Coupled with Benzyl Alcohol Oxidation over CdS/metal-Organic Framework Composites. Chem. Eng. J. 421, 129870. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.129870

Liao, W., Chen, W., Lu, S., Zhu, S., Xia, Y., Qi, L., et al. (2021). Alkaline Co(OH)2-Decorated 2D Monolayer Titanic Acid Nanosheets for Enhanced Photocatalytic Syngas Production from CO2. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 13 (32), 38239–38247. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c08251

Liu, Y., Zhang, P., Tian, B., and Zhang, J. (2015). Core-Shell Structural CdS@SnO2 Nanorods with Excellent Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity for the Selective Oxidation of Benzyl Alcohol to Benzaldehyde. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 7 (25), 13849–13858. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b04128

Liu, H., Xu, C., Li, D., and Jiang, H.-L. (2018). Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production Coupled with Selective Benzylamine Oxidation over MOF Composites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (19), 5379–5383. doi:10.1002/anie.201800320

Liu, H., Xu, C., Li, D., and Jiang, H.-L. (2018). Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production Coupled with Selective Benzylamine Oxidation over MOF Composites. Angew. Chem. 130 (19), 5477–5481. doi:10.1002/ange.201800320

Lu, S., Weng, B., Chen, A., Li, X., Huang, H., Sun, X., et al. (2021). Facet Engineering of Pd Nanocrystals for Enhancing Photocatalytic Hydrogenation: Modulation of the Schottky Barrier Height and Enrichment of Surface Reactants. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 13 (11), 13044–13054. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c19260

Mallat, T., and Baiker, A. (2004). Oxidation of Alcohols with Molecular Oxygen on Solid Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 104 (6), 3037–3058. doi:10.1021/cr0200116

Meng, S., Ye, X., Zhang, J., Fu, X., and Chen, S. (2018). Effective Use of Photogenerated Electrons and Holes in a System: Photocatalytic Selective Oxidation of Aromatic Alcohols to Aldehydes and Hydrogen Production. J. Catal. 367, 159–170. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2018.09.003

Meng, S., Ning, X., Chang, S., Fu, X., Ye, X., and Chen, S. (2018). Simultaneous Dehydrogenation and Hydrogenolysis of Aromatic Alcohols in One Reaction System via Visible-Light-Driven Heterogeneous Photocatalysis. J. Catal. 357, 247–256. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2017.11.015

Ou, M., Tu, W., Yin, S., Xing, W., Wu, S., Wang, H., et al. (2018). Amino-Assisted Anchoring of CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots on Porous g-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (41), 13570–13574. doi:10.1002/anie.201808930

Qadir, K., Kim, S. H., Kim, S. M., Ha, H., and Park, J. Y. (2012). Support Effect of Arc Plasma Deposited Pt Nanoparticles/TiO2 Substrate on Catalytic Activity of CO Oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 116 (45), 24054–24059. doi:10.1021/jp306461v

Qi, M.-Y., Li, Y.-H., Anpo, M., Tang, Z.-R., and Xu, Y.-J. (2020). Efficient Photoredox-Mediated C-C Coupling Organic Synthesis and Hydrogen Production over Engineered Semiconductor Quantum Dots. ACS Catal. 10 (23), 14327–14335. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c04237

Shang, W., Li, Y., Huang, H., Lai, F., Roeffaers, M. B. J., and Weng, B. (2021). Synergistic Redox Reaction for Value-Added Organic Transformation via Dual-Functional Photocatalytic Systems. ACS Catal. 11 (8), 4613–4632. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c04815

Sharma, R. K., Yadav, M., Monga, Y., Gaur, R., Adholeya, A., Zboril, R., et al. (2016). Silica-Based Magnetic Manganese Nanocatalyst - Applications in the Oxidation of Organic Halides and Alcohols. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 4 (3), 1123–1130. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01183

Shibuya, M., Osada, Y., Sasano, Y., Tomizawa, M., and Iwabuchi, Y. (2011). Highly Efficient, Organocatalytic Aerobic Alcohol Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (17), 6497–6500. doi:10.1021/ja110940c

Su, K., Dong, G.-X., Zhang, W., Liu, Z.-L., Zhang, M., and Lu, T.-B. (2020). In Situ Coating CsPbBr3 Nanocrystals with Graphdiyne to Boost the Activity and Stability of Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 12 (45), 50464–50471. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c14826

Wang, W., Wang, Z., Wang, J., Zhong, C.-J., and Liu, C.-J. (2017). Highly Active and Stable Pt-Pd Alloy Catalysts Synthesized by Room-Temperature Electron Reduction for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Adv. Sci. 4 (4), 1600486. doi:10.1002/advs.201600486

Wang, X., He, J., Li, J., Lu, G., Dong, F., Majima, T., et al. (2020). Immobilizing Perovskite CsPbBr3 Nanocrystals on Black Phosphorus Nanosheets for Boosting Charge Separation and Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 277, 119230. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119230

Wang, H., Hu, P., Zhou, J., Roeffaers, M. B. J., Weng, B., Wang, Y., et al. (2021). Ultrathin 2D/2D Ti3C2Tx/semiconductor Dual-Functional Photocatalysts for Simultaneous Imine Production and H2 Evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A. 9 (35), 19984–19993. doi:10.1039/d1ta03573h

Wang, C., Huang, H., Weng, B., Verhaeghe, D., Keshavarz, M., Jin, H., et al. (2022). Planar Heterojunction Boosts Solar-Driven Photocatalytic Performance and Stability of Halide Perovskite Solar Photocatalyst Cell. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 301, 120760. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120760

Wehrenfennig, C., Eperon, G. E., Johnston, M. B., Snaith, H. J., and Herz, L. M. (2014). High Charge Carrier Mobilities and Lifetimes in Organolead Trihalide Perovskites. Adv. Mater. 26 (10), 1584–1589. doi:10.1002/adma.201305172

Weng, B., Quan, Q., and Xu, Y.-J. (2016). Decorating Geometry- and Size-Controlled Sub-20 Nm Pd Nanocubes onto 2D TiO2 Nanosheets for Simultaneous H2 Evolution and 1,1-diethoxyethane Production. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4 (47), 18366–18377. doi:10.1039/c6ta07853b

Wu, Y., Ye, X., Zhang, S., Meng, S., Fu, X., Wang, X., et al. (2018). Photocatalytic Synthesis of Schiff Base Compounds in the Coupled System of Aromatic Alcohols and Nitrobenzene Using CdXZn1−XS Photocatalysts. J. Catal. 359, 151–160. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2017.12.025

Xia, B., Zhang, Y., Shi, B., Ran, J., Davey, K., and Qiao, S. Z. (2020). Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Coupled with Production of Value‐Added Chemicals. Small Methods 4 (7), 2000063. doi:10.1002/smtd.202000063

Xu, T., Zhang, L., Cheng, H., and Zhu, Y. (2011). Significantly Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance of ZnO via Graphene Hybridization and the Mechanism Study. Appl. Catal. B 101 (3), 382–387. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.10.007

Xu, Y.-F., Yang, M.-Z., Chen, B.-X., Wang, X.-D., Chen, H.-Y., Kuang, D.-B., et al. (2017). A CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dot/Graphene Oxide Composite for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (16), 5660–5663. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b00489

Yang, M.-Q., Dan, J., Pennycook, S. J., Lu, X., Zhu, H., Xu, Q.-H., et al. (2017). Ultrathin Nickel boron Oxide Nanosheets Assembled Vertically on Graphene: a New Hybrid 2D Material for Enhanced Photo/electro-Catalysis. Mater. Horiz. 4 (5), 885–894. doi:10.1039/c7mh00314e

Yang, B., Zhang, F., Chen, J., Yang, S., Xia, X., Pullerits, T., et al. (2017). Ultrasensitive and Fast All-Inorganic Perovskite-Based Photodetector via Fast Carrier Diffusion. Adv. Mater. 29 (40), 1703758. doi:10.1002/adma.201703758

Yang, X., Zhao, H., Feng, J., Chen, Y., Gao, S., and Cao, R. (2017). Visible-light-driven Selective Oxidation of Alcohols Using a Dye-Sensitized TiO2-Polyoxometalate Catalyst. J. Catal. 351, 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2017.03.017

Yang, M.-Q., and Xu, Y.-J. (2013). Selective Photoredox Using Graphene-Based Composite Photocatalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15 (44), 19102–19118. doi:10.1039/c3cp53325e

Yang, M.-Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, N., Tang, Z.-R., and Xu, Y.-J. (2013). Visible-Light-Driven Oxidation of Primary C-H Bonds over CdS with Dual Co-catalysts Graphene and TiO2. Sci. Rep. 3 (1), 3314. doi:10.1038/srep03314

Yang, M.-Q., Zhang, N., Pagliaro, M., and Xu, Y.-J. (2014). Artificial Photosynthesis over Graphene-Semiconductor Composites. Are We Getting Better? Chem. Soc. Rev. 43 (24), 8240–8254. doi:10.1039/c4cs00213j

Yang, M. Q., Shen, L., Lu, Y., Chee, S. W., Lu, X., Chi, X., et al. (2019). Disorder Engineering in Monolayer Nanosheets Enabling Photothermic Catalysis for Full Solar Spectrum (250-2500 Nm) Harvesting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (10), 3077–3081. doi:10.1002/anie.201810694

Yuan, Y., Xu, R., Xu, H.-T., Hong, F., Xu, F., and Wang, L.-J. (2015). Nature of the Band gap of Halide Perovskites ABX3 (A=CH3 NH3, Cs; B=Sn, Pb; X=Cl, Br, I): First-Principles Calculations. Chin. Phys. B 24 (11), 116302. doi:10.1088/1674-1056/24/11/116302

Zhang, Z., Shu, M., Jiang, Y., and Xu, J. (2021). Fullerene Modified CsPbBr3 Perovskite Nanocrystals for Efficient Charge Separation and Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 414, 128889. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.128889

Zhao, Y., and Zhu, K. (2016). Organic-inorganic Hybrid lead Halide Perovskites for Optoelectronic and Electronic Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45 (3), 655–689. doi:10.1039/c4cs00458b

Zhou, P., Chao, Y., Lv, F., Wang, K., Zhang, W., Zhou, J., et al. (2020). Metal Single Atom Strategy Greatly Boosts Photocatalytic Methyl Activation and C-C Coupling for the Coproduction of High-Value-Added Multicarbon Compounds and Hydrogen. ACS Catal. 10 (16), 9109–9114. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c01192

Keywords: perovskite, CsPbBr3, graphene oxide, anaerobic oxidation of aromatic alcohols, H2 production, photocatalysis

Citation: Chen T, Li M, Shen L, Roeffaers MBJ, Weng B, Zhu H, Chen Z, Yu D, Pan X, Yang M-Q and Qian Q (2022) Photocatalytic Anaerobic Oxidation of Aromatic Alcohols Coupled With H2 Production Over CsPbBr3/GO-Pt Catalysts. Front. Chem. 10:833784. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.833784

Received: 12 December 2021; Accepted: 11 February 2022;

Published: 15 March 2022.

Edited by:

Wee-Jun Ong, Xiamen University, MalaysiaCopyright © 2022 Chen, Li, Shen, Roeffaers, Weng, Zhu, Chen, Yu, Pan, Yang and Qian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bo Weng, Ym8ud2VuZ0BrdWxldXZlbi5iZQ==; Min-Quan Yang, eWFuZ21xQGZqbnUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.