95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 23 November 2022

Sec. Electrochemistry

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.1064752

This article is part of the Research Topic Defect Chemistry in Electrocatalysis View all 6 articles

Producing hydrogen through water electrolysis is one of the most promising green energy storage and conversion technologies for the long-term development of energy-related hydrogen technologies. MoS2 is a very promising electrocatalyst which may replace precious metal catalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). In this work, doughty-electronegative heteroatom defects (halogen atoms such as chlorine, fluorine, and nitrogen) were successfully introduced in MoS2 by using a large-scale, green, and simple ball milling strategy to alter its electronic structure. The physicochemical properties (morphology, crystallization, chemical composition, and electronic structure) of the doughty-electronegative heteroatom-induced defective MoS2 (N/Cl-MoS2) were identified using SEM, TEM, Raman, XRD, and XPS. Furthermore, compared with bulk pristine MoS2, the HER activity of N/Cl-MoS2 significantly increased from 442 mV to 280 mV at a current of 10 mA cm−2. Ball milling not only effectively reduced the size of the catalyst material, but also exposed more active sites. More importantly, the introduced doughty-electronegative heteroatom optimized the electronic structure of the catalyst. Therefore, the doughty-electronegative heteroatom induced by mechanical ball milling provides a useful reference for the large-scale production of green, efficient, and low-cost catalyst materials.

Hydrogen production from water splitting has become the mainstream process to meet the sustainable development of society, energy, and the environment. (Zou and Zhang, 2015) Various strategies have been developed to produce hydrogen, of which, photo-electrocatalytic and electrocatalytic water splitting were shown to be efficient and clean high-purity hydrogen production technologies. (Benck et al., 2014) Precious metal-based catalysts are the most active electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER); however, their large-scale utilization is limited by their relative scarcities and high costs. (Wu et al., 2013) The development of non-noble metal HER catalysts is thus imperative. The two-dimensional material molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), a transition metal sulfide, has exhibited a promising HER catalytic activity, similar to that of the precious metal Pt. (Jaramillo et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2022) However, previous research demonstrated that the electrocatalytic activity of pristine MoS2 is poor for the HER, due to its inferior electrical conductivity. (Hinnemann et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2016) Increasing the number of catalytically active sites as well as the electrical conductivity of MoS2 is expected to improve its intrinsic activity for the HER. (Li et al., 2018) A conventional strategy to realize this is to expose more edge-sulfur atoms in order to increase the number of active sites. For example, previous studies have shown that MoS2 materials benefit from more active edge sites when their size is brought down to the nanometer scale. (Chen et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013) In particular, defect engineering is also an important strategy to modulate the electronic structures of electrocatalysts for enhanced electrocatalytic intrinsic activities. (Xie et al., 2019) For example, defective MoS2 was obtained by adjusting the ratio of precursors (S and Mo), with a markedly improve electrocatalytic HER activity achieved. (Xie et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2016) Additionally, strategies were also developed to increase the electronic conductivity of MoS2 by introducing composites or heteroatoms. (Guo et al., 2015; Peto et al., 2018) For example, Dai’s group reported the growth of MoS2 nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide, with an impressive catalytic HER activity obtained. (Li et al., 2011) Yang’s group reported that MoS2 nanosheets supported by amorphous carbon exhibited an improved catalytic performance for the HER. (Yang et al., 2016) In addition, Wang et al. constructed defective structure-affluent MoS2 using oxygen plasma technology to enhance the electronic conductivity and augment the number of active edge sites. (Tao et al., 2015) These previous studies verified that the intrinsic activity of MoS2 can be greatly enhanced by intentionally introducing defects. Therefore, inducing defects is indeed an effective strategy to optimize the activities of MoS2 materials.

The electronegativity of the doped atoms may play a unique role in the modulation of the electronic structure of the catalyst. (Zheng et al., 2014) However, there are few reports on the different electronegativities of introduced heteroatoms and how they affect the electrocatalyst activity. Halogen atoms, especially chlorine and fluorine, both of which exhibit strong electronegativities, are expected to significantly modulate the electronic structure of catalysts after doping. (Zhang et al., 2021b) In addition, bulk two-dimensional materials can be reduced to nanoscale sizes by the ball milling shear force; physical or chemical doping of the material’s defect structure can be realized during the mechanical ball milling process. (Buzaglo et al., 2017) Previous work demonstrated that edge-selective heteroatom-doped defects can be obtained by ball milling a mixture containing a two-dimensional material and an impurity atom source. (Xiao et al., 2016) For example, the Dai team used ball milling to mix graphite and non-metallic elements, obtaining heteroatom-doped graphene. (Jeon et al., 2013) Molybdenum disulfide and graphite are two-dimensional materials with layered structures. It can be expected that non-metallic target atoms can also be doped into the MoS2 crystal structure during the ball milling process.

Herein, we explore the doughty-electronegative heteroatom-induced defect structure of MoS2, in which the commercial bulk MoS2 incorporated strongly electronegative halogen atoms during mechanical ball milling processing. Ball milling not only reduced the size of the bulk material and made it thinner, but also exposed more active sites for catalytic reaction. At the same time, the doped defect heteroatom regulated and optimized both the surface and the electronic structure of MoS2. Thus, its intrinsic activity was significantly increased. Compared with bulk pristine MoS2, the HER activity of defect-induced MoS2 significantly increased from 442 mV to 280 mV at a current of 10 mA cm−2. The defect-induced effect of electronegative heteroatoms through ball milling provides a new design strategy to prepare effective HER catalyst materials, providing a useful reference for the research, development, and commercial mass production of high-performance catalysts.

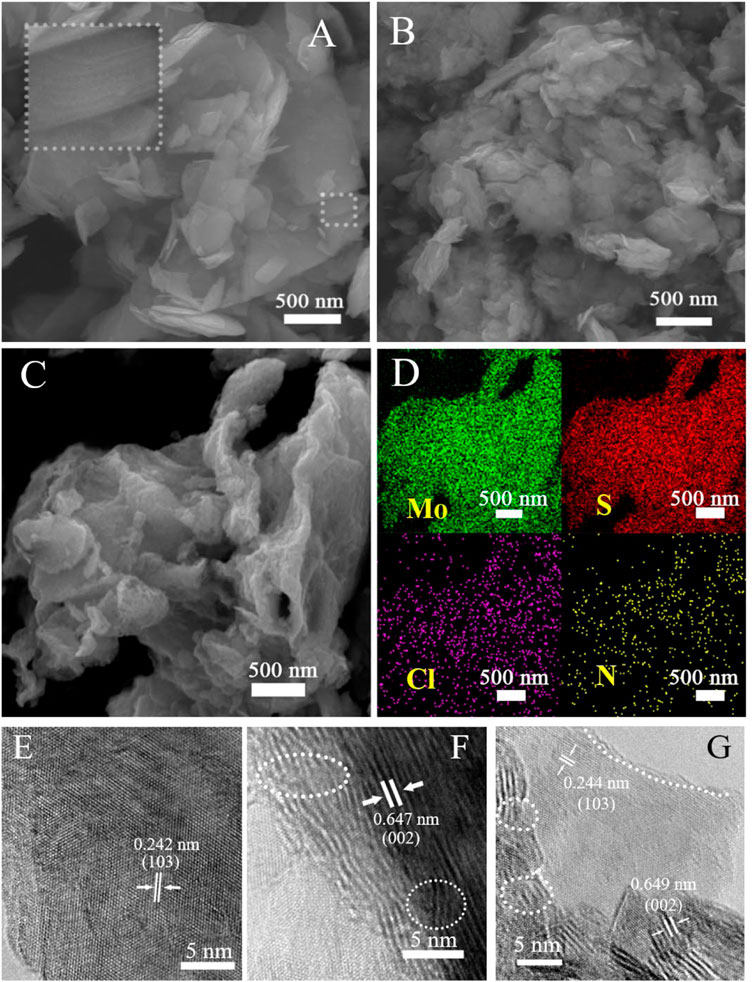

Doughty-electronegative heteroatom-induced defective MoS2 materials were prepared by simple mixed ball milling (see the Experimental section in the Supplementary Material S1). Briefly, bulk commercial MoS2 (denoted as pristine MoS2) and a halogen source containing doughty-electronegative elements (for example, NH4Cl as the N and Cl source) were mixed and ball-milled, followed by removal of the residual by-products and impurities. (Xue et al., 2015) The final catalyst product obtained was denoted as N/Cl-MoS2. Analogously, non-doping defective MoS2 was obtained (denoted as BM-MoS2) by directly ball milling bulk commercial MoS2 with no halogen source present. The morphologies of the as-prepared MoS2 samples were firstly examined by scanning electron microscopic (SEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), and the results are shown in Figure 1. Pristine MoS2 (Figure 1A) exhibits large-sized nanosheets that were closely packed to on another, resulting in fewer exposed active sites. However, compared with pristine MoS2, the BM-MoS2 (Figure 1B) and N/Cl-MoS2 (Figure 1C) were fragmented to the nanoscale, which was caused by ball milling with or without a halogen source. In strong contrast to pristine MoS2 which was on the micron size scale, the sizes of the BM-MoS2 and N/Cl-MoS2 decreased to a few hundred nanometers and exhibited exfoliated layered structures. SEM-EDS elemental mapping analysis was performed to confirm the contents of N and Cl, and the results are shown in Figure 1D and Supplementary Table S1. The results show that nitrogen and chlorine were successfully doped into the MoS2; the amounts of nitrogen and chlorine in the N/Cl-MoS2 were 6.04% and 4.00%, respectively. These results are consistent with previous studies on ball milling. (Buzaglo et al., 2017) Furthermore, the progressive morphologies of three catalyst materials were distinguished by HR-TEM imaging. Pristine MoS2 exhibits a relatively complete crystal structure, as shown in Figure 1E. An interplanar spacing of 0.242 nm was observed, which was consistent with the d spacing of the (103) planes of hexagonal MoS2. (Sun et al., 2022) The interplanar spacing (0.647 nm) was also observed in the HR-TEM image of MoS2 with no halogen doping, as shown in Figure 1F. However, the laminar structure was damaged, as indicated by the white dotted lines, indicating that edge faults are obtained by the ball milling shear force. As shown in Figure 1G, after nitrogen and chlorine were doped into the N/Cl-MoS2 by ball milling, in addition to the main lattice spacing (0.244 nm) corresponding to the (103) crystal plane structure, a lattice spacing of 0.649 nm corresponding to the (002) crystal plane structure was found to exist. This indicates that in the presence of a halogen precursor, ball milling produced a unique N/Cl-MoS2 product with more exposed surface structures, signifying that a variety of defect structures were introduced. After careful observation, the product was found to be relatively disordered in terms of the crystal structure. A reasonable explanation for this is that halogen atoms introduced to the MoS2 crystal structure formed localized areas of N-Mo and Cl-Mo bonds during ball milling, in which the original electronic structure was altered, forming unique locally disordered lattice structures. Thus, a novel, defective MoS2 structure was prepared, which should display a significantly superior intrinsic HER activity.

FIGURE 1. SEM images of (A) pristine MoS2, (B) BM-MoS2, and (C) N/Cl-MoS2. (D) EDS elemental mapping of N/Cl-MoS2 from (C). HR-TEM images of (E) pristine MoS2, (F) BM-MoS2, and (G) N/Cl-MoS2.

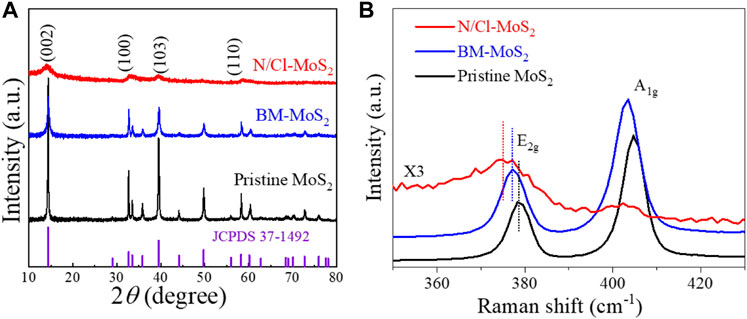

The crystal structure of N/Cl-MoS2 was identified by XRD. As shown in Figure 2A, the three MoS2 catalyst materials all correspond well to the hexagonal structure (JCPDS 37-1492) and display similar diffraction peaks. (Han et al., 2018) Compared with the pristine MoS2, the BM-MoS2 and N/Cl-MoS2 presented worse crystallinities with reduced intensity and broadened peaks. The crystallinities of the MoS2 samples after ball milling tend to be disordered. (Sun et al., 2022) After introducing the heteroatoms N and Cl, the XRD pattern of N/Cl-MoS2 was similar to that of pristine MoS2, with no new diffraction peaks present, indicating that no new phases (such as MoN or MoCl5) were formed. This result indicated that mechanical ball milling has a shear peeling effect on the material, generating smaller and thinner nanometer sized, layered molybdenum disulfide, consistent with the SEM and HR-TEM results. (Xie et al., 2012) In addition, Raman spectroscopy is an effective tool for characterizing the material structure and its defects. (Mignuzzi et al., 2015) As shown in Figure 2B, for all three MoS2 samples, characteristic peaks at approximately 405 cm−1 and 378 cm−1 were observed, which belong to the out-of-plane A1g and the in-plane E 12g modes, respectively. (Hong et al., 2012; Mignuzzi et al., 2015) Compared with the pristine MoS2, the BM-MoS2 Raman peaks were slightly shifted to lower wavenumbers, attributed to a sharp reduction in both the size and thinning due to ball milling, indicating a local change in the electronic structure. (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2016) After the introduction of N and Cl, the characteristic diffraction peaks of the N/Cl-MoS2 samples were significantly shifted, proving that the introduction of N and Cl heteroatoms with different electronegativities changed the electronic structure of N/Cl-MoS2. No new peak for the N/Cl-MoS2 appears in the range 300–500 cm−1 (the peak signal of N/Cl-MoS2 is too weak; magnified ×3), indicating that no MoN or MoCl5 were formed, consistent with the XRD and TEM results. The results so far are consistent; it is reasonable to speculate that N and Cl are present in the electrocatalytic material in doped form. On the other hand, compared with non-doped BM-MoS2, the intensities of the E 12g and A1g peaks for N/Cl-MoS2 were weaker. This indicates that the sample was more disordered, due to adjustment and optimization of the electronic structure of MoS2 upon introduction of electronegative impurity doping atoms that occupy defect sites. (Mignuzzi et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016) These results provide preliminary evidence that mechanical ball mill shearing and doughty-electronegative halogen doping 1) produced a N/Cl-MoS2 product that exhibits a nanoscale size and thickness, 2) exposed a large number of sulfur edge sites, and 3) optimized the electronic properties of molybdenum disulfide materials by introducing nitrogen and chlorine doping atoms at defect sites.

FIGURE 2. (A) XRD patterns of pristine MoS2, BM-MoS2, and N/Cl-MoS2. (B) Raman spectra of pristine MoS2, BM-MoS2, and N/Cl-MoS2.

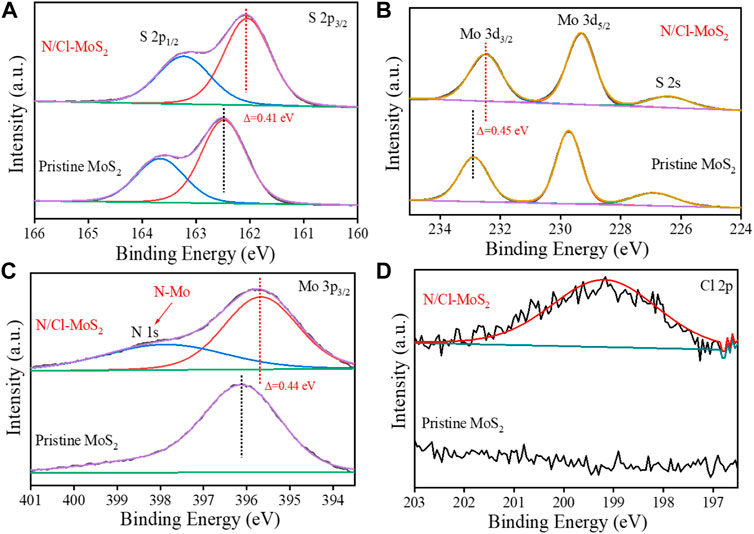

To investigate the defect-induced effect of doughty-electronegative N and Cl atoms on the electronic structure of the electrocatalyst, we performed X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis on the MoS2 samples. High-resolution XPS analysis of N/Cl-MoS2 and pristine MoS2 was performed, and the results are shown in Figure 3. The characteristic S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2 peaks were identified at 163.6 eV and 162.5 eV, respectively, as shown in Figure 3A. Compared with pristine MoS2, the S 2p3/2 peak for N/Cl-MoS2 tended toward lower binding energies and was shifted by 0.41 eV (Zhang et al., 2021b) Similarly, the Mo 3d3/2 (232.3 eV in Figure 3B) and Mo 3p3/2 peaks (396.1 eV in Figure 3C) for N/Cl-MoS2 were shifted to lower binding energies by 0.45 eV and 0.44 eV, respectively. The lower binding energies of the Mo 3d3/2 and S 2p peaks for heteroatom-induced defective MoS2 are attributed to the halogen heteroatom doping process, since halogen heteroatoms exhibit strong electronegativities that shifts the Fermi level of MoS2 toward the conduction band edge, consistent with previous reports. (Chen et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2021b) These results further prove the successful doping of N and Cl and their effect on the electronic structure of MoS2. In addition, as shown in Figures 3A,C characteristic N 1s peak was observed in N/Cl-MoS2, which indicates the formation of the N-Mo bond. (Xiao et al., 2017) Moreover, a characteristic Cl 2p peak appears at 199.2 eV as shown in Figure 3D, indicating that Cl was successfully doped into MoS2. (Zheng et al., 2014) These XPS results show that doughty-electronegative N and Cl atoms were successfully introduced into the defective MoS2, and that the electronic structure of MoS2 was modulated, providing a prediction for superior HER performance.

FIGURE 3. XPS spectra of the pristine MoS2 and N/Cl-MoS2. (A) XPS spectra of S 2p in MoS2 samples. (B) XPS spectra of Mo 3 d in MoS2 samples. (C) XPS spectra of Mo 3p and N 1s in MoS2 samples. (D) XPS spectra of Cl 2p in the MoS2 sample.

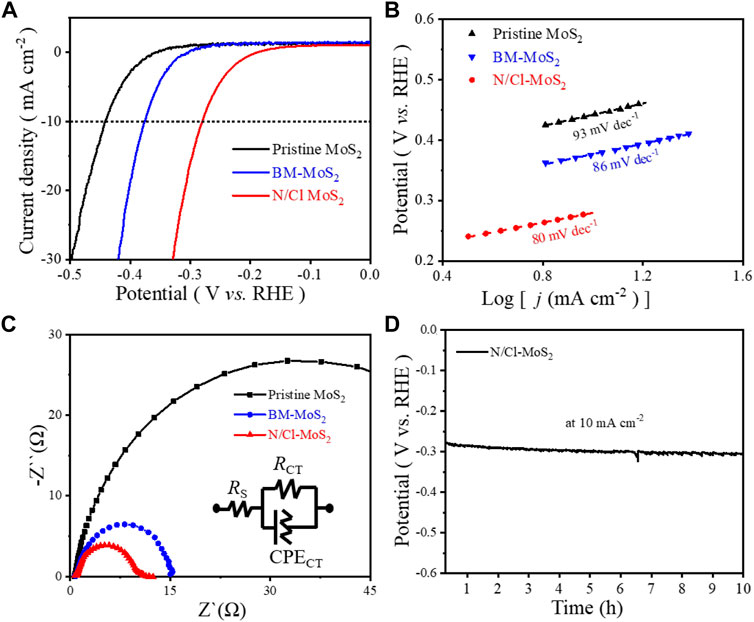

Through combined analysis of SEM, HR-TEM, XRD, Raman spectroscopy, and XPS, the unique defect-induced electronic structure caused by doughty-electronegative N and Cl atoms in disordered crystalline MoS2 has been determined. The N/Cl-MoS2 sample should present the best intrinsic conductivity compared with pristine MoS2 and BM-MoS2; this should also benefit the catalytic activity. Therefore, we expect the novel N/Cl-MoS2 to exhibit superior HER performance. To estimate the HER performances of these MoS2 samples (as shown in Figure 4), we obtained linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) polarization curves for the pristine MoS2, BM-MoS2, and N/Cl-MoS2 by using a typical three-electrode system. LSV curves were obtained with iR-compensation (95%) at 5 mV s−1 in a 1.0 mol L−1 KOH solution, as shown in Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S1. We tested the HER performances of ball milled MoS2 samples for different ratios of NH4Cl as a N and Cl atom source, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Initially, the activity increased as the ratio of NH4Cl increased. The best ratio of NH4Cl to MoS2 was found to be 5:1. We also investigated either a single Cl source or a single N source as a dopant at a ratio of 5:1. The electrochemical results showed that the HER catalytic activity of defect-induced MoS2 using double halogen atoms is superior to using a single dopant. As shown in Figure 4A, the LSV curves of the pristine MoS2 and BM-MoS2 exhibit poor HER performance with inferior overpotentials (approximately 310 mV and 280 mV, respectively) as well as low cathodic current densities. Pristine MoS2 required an overpotential of 442 mV and BM-MoS2 372 mV to reach 10 mA cm−2, however, the N/Cl-MoS2 only required 280 mV; the N/Cl-MoS2 exhibits excellent HER activity. These preliminary results showed that, compared with pristine MoS2 and BM-MoS2, after introducing Cl and N heteroatoms, N/Cl-MoS2 exhibited superior activity for the HER. The results also showed that bulk pristine MoS2 was smaller and thinner after mechanical ball milling shear stripping, thus exposing more sulfur sites to enhance the catalytic performance of the HER reaction. More importantly, the NH4Cl source was broken into electronic N and Cl atoms during ball milling, which doped the molybdenum disulfide to obtain N/Cl-MoS2, exhibiting a higher HER performance than undoped MoS2. Therefore, the electronic structure of molybdenum disulfide was regulated and optimized by the introduction of N and Cl defect doping atoms, enhancing the intrinsic conductivity and HER catalytic activity. Furthermore, Supplementary Table S2 summarizes the HER catalytic activity of various Mo-based electrocatalysts, which shows that the HER catalytic activity of the N/Cl-MoS2 electrocatalyst prepared in this paper is not inferior to other Mo electrocatalysts.

FIGURE 4. (A) LSV polarization curves for pristine MoS2, BM-MoS2, and N/Cl-MoS2. (B) Tafel plots for pristine MoS2, BM-MoS2, and N/Cl-MoS2. (C) Nyquist plots for pristine MoS2, BM-MoS2, and N/Cl-MoS2. (D) Stability measurements for N/Cl-MoS2.

Usually, the Tafel slope curve equation is fitted to the LSV data to explain the kinetics of catalyst materials during the HER. (Junfeng et al., 2013) It is well known that the smaller the Tafel slope, the faster the velocity of the catalytic process, and the more conducive to practical application of catalysts. (Yan et al., 2014) The corresponding Tafel plots of the three MoS2 samples are shown in Figure 4B. Compared with the Tafel slopes of pristine MoS2 (93 mV dec−1) and BM-MoS2 (86 mV dec−1), the N/Cl-MoS2 exhibited a smaller Tafel slope of 80 mV dec−1, indicating higher hydrogen evolution activity and a faster electron transfer rate. To investigate the charge transfer ability of the catalysts at the electrolyte/electrode interface, electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) for the pristine MoS2, BM-MoS2, and N/Cl-MoS2 were obtained. Figure 4C shows the EIS results for the three MoS2 catalysts. Furthermore, the interface reactions and electrode kinetics of the MoS2 samples were clarified using Nyquist plots; they reveal a dramatically decreased charge-transfer resistance for N/Cl-MoS2 compared with BM-MoS2 and pristine MoS2. (Jiang et al., 2021) As shown in Supplementary Table S3, the impedance fitting data for the MoS2-based electrocatalyst was summarized. The results showed that N/Cl-MoS2 exhibited a lower charge transfer resistance (Rct = 143Ω) and a faster electron transfer rate than those of pristine MoS2 (Rct = 997 Ω) and BM-MoS2 (Rct = 219 Ω), indicating that N/Cl-MoS2 possessed a faster charge transfer capability in the HER. (Wang et al., 2013) In addition, stability is also an important index for catalyst materials. After continuous galvanostatic operation for 10 h (Figure 4D), the attenuation degree of the electrocatalytic current density is almost negligible for N/Cl-MoS2, indicating that the long-term stability is relatively reliable. In other words, the introduction of electronegative heteroatoms in defective MoS2 significantly regulates the material’s crystal structure and electron characteristics upon co-doping with N and Cl atoms, improving the conductivity and catalytic activity.

The electrochemical surface areas (ECSAs) were calculated by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. The double layer capacitance (Cdl) of N/Cl-MoS2 was 3.1 mF cm−2, which is significantly higher than that of pristine MoS2 (0.7 mF cm−2), but lower than that of BM-MoS2 (7.8 mF cm−2). This result is consistent with the SEM, Raman, and XRD characterization. Compared with non-doped BM-MoS2, although the number of catalytic sites in N/Cl-MoS2 was reduced, the electrochemical data (such as LSV polarization curves) indicated that the HER catalytic activity of N/Cl-MoS2 was significantly enhanced. Therefore, a reasonable inference is that the introduced halogen atoms enhanced the intrinsic activity, rather than it relying solely on an increase in the number of active sites. These results prove that N/Cl-MoS2 possessed more effective active sites due to the introduction of halogen atoms during ball milling, regulating the electronic structure to enhance the intrinsic HER activity.

The ball milling strategy could also be used to tailor the electronic structure of MoS2 with other halogen atoms (such as N/F-MoS2, the detailed experimental preparation and characterization results of which are provided in the Supplementary Material S1 and Supplementary Figures S3–S6). We tested the electrochemical activity of N/F-MoS2 for the HER. Supplementary Figure S7 shows the LSV curves for N/F-MoS2, prepared using different ratios of NH4F and MoS2. The catalytic HER results suggested that the best ratio of NH4F to MoS2 was 10:1. Its performance was also superior to F-MoS2 under identical conditions. The electrochemical surface area of N/F-MoS2 (15.4 mF cm−2) was higher than that of pristine MoS2 (0.7 mF cm−2) and BM-MoS2 (7.8 mF cm−2), as shown in Supplementary Figure S8. Similar to N/Cl-MoS2, N and F doping of MoS2 also showed reasonable stability (Supplementary Figure S9). These electrochemical results for N/F-MoS2 were similar to the results for N/Cl-MoS2 discussed above. Compared with single heteroatom introduction, nitrogen and halogen double heteroatom-induced defective MoS2 exhibited superior electrocatalytic HER activity, indicating that the electronic structure of the catalyst was regulated by heteroatoms, whether single or double. However, according to the preliminary electrochemical data, modulation using two different doped heteroatoms was more appropriate. In addition, under identical conditions, the N and Cl doped MoS2 electrocatalyst was more active compared to doping with N and F, indicating that the introduced doping heteroatom should not be too electronegative, otherwise inferior results will be obtained. Further research into this will be carried out in future.

In summary, the doughty-electronegative heteroatoms N and Cl were successfully introduced into the crystal structure of MoS2 by utilizing a ball milling strategy. The obtained N/Cl-MoS2 electrocatalyst presents a significantly improved HER catalytic activity. Compared with the large micrometer-sized bulk pristine MoS2, the size of the N/Cl-MoS2 is remarkably reduced to the nanometer scale, and the number of exposed active sites is significantly increased. On the other hand, the electronic structure of N/Cl-MoS2 is effectively modulated by ball milling and introducing the doughty-electronegative heteroatom N and Cl; the HER activity is significantly enhanced. Compared with pristine MoS2, the overpotential of N/Cl-MoS2 is observably reduced from 442 mV to 280 mV at 10 mA cm−2. This work demonstrates that defect introduction using a doughty-electronegative doping heteroatom could significantly modulate the electronic structure of MoS2, thereby enhancing the HER activity and providing a useful strategy for the design of high-efficiency electrocatalysts.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

ZX and SDL contributed equally to this work. ZX and SDL conducted the project. SDL, WD, and SH performed the measurements. XZ and YPL helped analyze and discuss the data. LY provided valuable technical support for the ball milling experiments. ZX, SDL, and SWL wrote and revised the paper. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and have read and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the fund of the Innovation center for Academician team of Hainan Province, and the specific research fund of the Innovation Platform for Academicians of Hainan Province (YSPTZX202123).

The authors also acknowledge the financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2020JJ5039).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.1064752/full#supplementary-material

Benck, J. D., Hellstern, T. R., Kibsgaard, J., Chakthranont, P., and Jaramillo, T. F. (2014). Catalyzing the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) with molybdenum sulfide nanomaterials. ACS Catal. 4 (11), 3957–3971. doi:10.1021/cs500923c

Buzaglo, M., Bar, I. P., Varenik, M., Shunak, L., Pevzner, S., and Regev, O. (2017). Graphite-to-Graphene: Total conversion. Adv. Mat. 29 (8), 1603528. doi:10.1002/adma.201603528

Chen, Z., Cummins, D., Reinecke, B. N., Clark, E., Sunkara, M. K., and Jaramillo, T. F. (2011). Core–shell MoO3–MoS2 nanowires for hydrogen evolution: A functional design for electrocatalytic materials. Nano Lett. 11 (10), 4168–4175. doi:10.1021/nl2020476

Chen, M., Nam, H., Wi, S., Ji, L., Ren, X., Bian, L., et al. (2013). Stable few-layer MoS2 rectifying diodes formed by plasma-assisted doping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103 (14), 142110. doi:10.1063/1.4824205

Guo, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., and You, T. (2015). Defect- and S-rich ultrathin MoS2 nanosheet embedded N-doped carbon nanofibers for efficient hydrogen evolution. J. Mat. Chem. A Mat. 3 (31), 15927–15934. doi:10.1039/C5TA03766B

Guo, M., Qayum, A., Dong, S., JiaoX., , Chen, D., and Wang, T. (2020). In situ conversion of metal (Ni, Co or Fe) foams into metal sulfide (Ni3S2, Co9S8 or FeS) foams with surface grown N-doped carbon nanotube arrays as efficient superaerophobic electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. J. Mat. Chem. A Mat. 8 (18), 9239–9247. doi:10.1039/D0TA02337J

Guo, M., Zhan, J., Wang, Z., Wang, X., Dai, Z., and Wang, T. (2022). Supercapacitors as redox mediators for decoupled water splitting. Chin. Chem. Lett.. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.07.052

Han, X., Tong, X., Liu, X., Chen, A., Wen, X., Yang, N., et al. (2018). Hydrogen evolution reaction on hybrid catalysts of vertical MoS2 nanosheets and hydrogenated graphene. ACS Catal. 8 (3), 1828–1836. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b03316

Hinnemann, B., Moses, P. G., Bonde, J., Jørgensen, K. P., Nielsen, J. H., Horch, S., et al. (2005). Biomimetic hydrogen evolution: MoS2 nanoparticles as catalyst for hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (15), 5308–5309. doi:10.1021/ja0504690

Hong, L., Qing, Z., Ray, Y. C. C., Kang, T. B., Tong, E. T. H., Aurelien, O., et al. (2012). From bulk to monolayer MoS2: Evolution of Raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mat. 22 (7), 1385–1390. doi:10.1002/adfm.201102111

Huang, G., Li, Y., Chen, R., Xiao, Z., Du, S., Huang, Y., et al. (2022). Electrochemically formed PtFeNi alloy nanoparticles on defective NiFe LDHs with charge transfer for efficient water splitting. Chin. J. Catal. 43 (4), 1101–1110. doi:10.1016/S1872-2067(21)63926-8

Jaramillo, T. F., Jørgensen, K. P., Bonde, J., Nielsen, J. H., Horch, S., and Chorkendorff, I. (2007). Identification of active edge sites for electrochemical H2 evolution from MoS2 nanocatalysts. Science 317 (5834), 100–102. doi:10.1126/science.1141483

Jeon, I.-Y., Choi, H.-J., Jung, S.-M., Seo, J.-M., Kim, M.-J., Dai, L., et al. (2013). Large-scale production of edge-selectively functionalized graphene nanoplatelets via ball milling and their use as metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (4), 1386–1393. doi:10.1021/ja3091643

Jiang, Z., Xiao, Z., Tao, Z., Zhang, X., and Lin, S. (2021). A significant enhancement of bulk charge separation in photoelectrocatalysis by ferroelectric polarization induced in CdS/BaTiO3 nanowires. RSC Adv. 11 (43), 26534–26545. doi:10.1039/D1RA04561J

Junfeng, X., Hao, Z., Shuang, L., Ruoxing, W., Xu, S., Min, Z., et al. (2013). Defect-Rich MoS2 ultrathin nanosheets with additional active edge sites for enhanced electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mat. 25 (40), 5807–5813. doi:10.1002/adma.201302685

Krishnamoorthy, K., Pazhamalai, P., Veerasubramani, G. K., and Kim, S. J. (2016). Mechanically delaminated few layered MoS2 nanosheets based high performance wire type solid-state symmetric supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 321, 112–119. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.04.116

Li, Y., Wang, H., Xie, L., Liang, Y., Hong, G., and Dai, H. (2011). MoS2 nanoparticles grown on graphene: An advanced catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (19), 7296–7299. doi:10.1021/ja201269b

Li, Y., Yin, K., Wang, L., Lu, X., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., et al. (2018). Engineering MoS2 nanomesh with holes and lattice defects for highly active hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 239, 537–544. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.05.080

Liu, Q., Weijun, X., Wu, Z., Huo, J., Liu, D., Wang, Q., et al. (2016). The origin of the enhanced performance of nitrogen-doped MoS2 in lithium ion batteries. Nanotechnology 27 (17), 175402. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/27/17/175402

Liu, X., Hou, Y., Tang, M., and Wang, L. (2022). Atom elimination strategy for MoS2 nanosheets to enhance photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chin. Chem. Lett.. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.05.003

Mignuzzi, S., Pollard, A. J., Bonini, N., Brennan, B., Gilmore, I. S., Pimenta, M. A., et al. (2015). Effect of disorder on Raman scattering of single-layerMoS2. Phys. Rev. B 91 (19), 195411. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.91.195411

Peto, J., Ollar, T., Vancso, P., Popov, Z. I., Magda, G. Z., Dobrik, G., et al. (2018). Spontaneous doping of the basal plane of MoS2 single layers through oxygen substitution under ambient conditions. Nat. Chem. 10 (12), 1246–1251. doi:10.1038/s41557-018-0136-2

Sun, C., Liu, M., Wang, L., Xie, L., Zhao, W., Li, J., et al. (2022). Revisiting lithium-storage mechanisms of molybdenum disulfide. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (4), 1779–1797. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.052

Tao, L., Duan, X., Wang, C., Duan, X., and Wang, S. (2015). Plasma-engineered MoS2 thin-film as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 51 (35), 7470–7473. doi:10.1039/c5cc01981h

Wang, H., Lu, Z., Xu, S., Kong, D., Cha, J. J., Zheng, G., et al. (2013). Electrochemical tuning of vertically aligned MoS2 nanofilms and its application in improving hydrogen evolution reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110 (49), 19701–19706. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316792110

Wu, Z., Fang, B., Wang, Z., Wang, C., Liu, Z., Liu, F., et al. (2013). MoS2 nanosheets: A designed structure with high active site density for the hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Catal. 3 (9), 2101–2107. doi:10.1021/cs400384h

Xiao, Z., Huang, X., Xu, L., Yan, D., Huo, J., and Wang, S. (2016). Edge-selectively phosphorus-doped few-layer graphene as an efficient metal-free electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 52 (88), 13008–13011. doi:10.1039/C6CC07217H

Xiao, W., Liu, P. T., Zhang, J. Y., Song, W. D., Feng, Y. P., Gao, D. Q., et al. (2017). Dual-functional N dopants in edges and basal plane of MoS2 nanosheets toward efficient and durable hydrogen evolution. Adv. Energy Mat. 7 (7), 1602086. ARTN 1602086. doi:10.1002/aenm.201602086

Xiao, Z., Xie, C., Wang, Y., Chen, R., and Wang, S. (2021). Recent advances in defect electrocatalysts: Preparation and characterization. J. Energy Chem. 53, 208–225. doi:10.1016/j.jechem.2020.04.063

Xie, J., Wu, C., Hu, S., Dai, J., Zhang, N., Feng, J., et al. (2012). Ambient rutile VO2(R) hollow hierarchitectures with rich grain boundaries from new-state nsutite-type VO2, displaying enhanced hydrogen adsorption behavior. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14 (14), 4810–4816. doi:10.1039/C2CP40409E

Xie, J., Zhang, H., Li, S., Wang, R., Sun, X., Zhou, M., et al. (2013). Defect-Rich MoS2 ultrathin nanosheets with additional active edge sites for enhanced electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mat. 25 (40), 5807–5813. doi:10.1002/adma.201302685

Xie, X., Jiang, Y.-F., Yuan, C.-Z., Jiang, N., Zhao, S.-J., Jia, L., et al. (2017). Ultralow Pt loaded molybdenum dioxide/carbon nanotubes for highly efficient and durable hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 121 (45), 24979–24986. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b08283

Xie, C., Yan, D., Chen, W., Zou, Y., Chen, R., Zang, S., et al. (2019). Insight into the design of defect electrocatalysts: From electronic structure to adsorption energy. Mater. Today 31, 47–68. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2019.05.021

Xie, S., Liu, C., Song, R., Ji, Y., Xiao, Z., Huo, C., et al. (2022). A facile and environmental-friendly approach to synthesize S-doped Fe/Ni layered double hydroxide catalyst with high oxygen evolution reaction efficiency in water splitting. ChemElectroChem 9 (11), e202200217. doi:10.1002/celc.202200217

Xu, J., Jeon, I.-Y., Seo, J.-M., Dou, S., Dai, L., and Baek, J.-B. (2014). Edge-Selectively halogenated graphene nanoplatelets (XGnPs, X = Cl, Br, or I) prepared by ball-milling and used as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mat. 26 (43), 7317–7323. doi:10.1002/adma.201402987

Xu, Y., Wang, L., Liu, X., Zhang, S., Liu, C., Yan, D., et al. (2016). Monolayer MoS2 with S vacancies from interlayer spacing expanded counterparts for highly efficient electrochemical hydrogen production. J. Mat. Chem. A Mat. 4 (42), 16524–16530. doi:10.1039/C6TA06534A

Xue, Y., Chen, H., Qu, J., and Dai, L. (2015). Nitrogen-doped graphene by ball-milling graphite with melamine for energy conversion and storage. 2D Mat. 2 (4), 044001. doi:10.1088/2053-1583/2/4/044001

Yan, D., Xia, C., Zhang, W., Hu, Q., He, C., Xia, B. Y., et al. (2022). Cation defect engineering of transition metal electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 2202317. doi:10.1002/aenm.202202317

Yan, Y., Xia, B., Xu, Z., and Wang, X. (2014). Recent development of molybdenum sulfides as advanced electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Catal. 4 (6), 1693–1705. doi:10.1021/cs500070x

Yang, L., Zhou, W., Lu, J., Hou, D., Ke, Y., Li, G., et al. (2016). Hierarchical spheres constructed by defect-rich MoS2/carbon nanosheets for efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nano Energy 22, 490–498. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.02.056

Ye, G., Gong, Y., Lin, J., Li, B., He, Y., Pantelides, S. T., et al. (2016). Defects engineered monolayer MoS2 for improved hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Lett. 16 (2), 1097–1103. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04331

Zhang, P., Xu, B. H., Chen, G. L., Gao, C. X., and Gao, M. Z. (2018). Large-scale synthesis of nitrogen doped MoS2 quantum dots for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochimica Acta 270, 256–263. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2018.03.097

Zhang, S., Zhang, Z., Si, Y., Li, B., Deng, F., Yang, L., et al. (2021). Gradient hydrogen migration modulated with self-adapting S vacancy in copper-doped ZnIn2S4 nanosheet for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. ACS Nano 15 (9), 15238–15248. doi:10.1021/acsnano.1c05834

Zhang, R., Zhang, M., Yang, H., Li, G., Xing, S., Li, M., et al. (2021). Creating fluorine-doped MoS2 edge electrodes with enhanced hydrogen evolution activity. Small Methods 5 (11), 2100612. doi:10.1002/smtd.202100612

Zheng, Y., Jiao, Y., Li, L. H., Xing, T., Chen, Y., Jaroniec, M., et al. (2014). Toward design of synergistically active carbon-based catalysts for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. ACS Nano 8 (5), 5290–5296. doi:10.1021/nn501434a

Zhu, Y., Ling, Q., Liu, Y., Wang, H., and Zhu, Y. (2015). Photocatalytic H2 evolution on MoS2-TiO2 catalysts synthesized via mechanochemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17 (2), 933–940. doi:10.1039/C4CP04628E

Keywords: defect-induced, molybdenum disulfide, electronegative, electrocatalysts, hydrogen evolution reaction

Citation: Xiao Z, Luo S, Duan W, Zhang X, Han S, Liu Y, Yang L and Lin S (2022) Doughty-electronegative heteroatom-induced defective MoS2 for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Front. Chem. 10:1064752. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.1064752

Received: 08 October 2022; Accepted: 01 November 2022;

Published: 23 November 2022.

Edited by:

Longlu Wang, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, ChinaReviewed by:

Hongda Li, Guangxi University of Science and Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Xiao, Luo, Duan, Zhang, Han, Liu, Yang and Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhaohui Xiao, eGlhb3poQGhhaW5hbnUuZWR1LmNu, eGlhb3poQGhudS5lZHUuY24=; Shiwei Lin, bGluc3dAaGFpbmFudS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.