- 1Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 3Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai, China

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is considered to be a principal cause of cancer death across the world, and nanomedicine has provided promising alternatives for the treatment of NSCLC in recent years. Photothermal therapy (PTT) and chemodynamic therapy (CDT) have represented novel therapeutic modalities for cancer treatment with excellent performance. The purpose of this research was to evaluate the effects of PPy@Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) on inhibiting growth and metastasis of NSCLC by combination of PTT and CDT. In this study, we synthesized PPy@Fe3O4 NPs through a very facile electrostatic absorption method. And we detected reactive oxygen species production, cell apoptosis, migration and protein expression in different groups of A549 cells and established xenograft models to evaluate the effects of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs for inhibiting the growth of NSCLC. The results showed that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs had negligible cytotoxicity and could efficiently inhibit the cell growth and metastasis of NSCLC in vitro. In addition, the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs decreased tumor volume and growth in vivo and endowed their excellent MRI capability of observing the location and size of tumor. To sum up, our study displayed that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs had significant synergistic effects of PTT and CDT, and had good biocompatibility and safety in vivo and in vitro. The PPy@Fe3O4 NPs may be an effective drug platform for the treatment of NSCLC.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the most common malignant cancer, which has the highest rates of mortality. (Nasim et al., 2019; Woodman et al., 2021) Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is one of the histological subtypes, which accounts for approximately 80–85% among lung cancers. (Oser et al., 2015) Over the last decade, considerable progress has been made in the treatment of NSCLC, helping us to understand tumor biology deeply and promoting the early detection and multimodal cancer treatment. (Herbst et al., 2018) However, metastatic lung cancer is still an incurable disease and has a median survival of only 5 months. (Riihimäki et al., 2014; Rosell and Karachaliou, 2015) At present, the conservative therapeutic methods including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are efficient modes to manage advanced lung cancer, but remain unsatisfactory for improving the therapeutic efficacy. (Luo et al., 2018) As such, continuous researches on novel therapeutic compounds and combination treatments are required to amplify clinical outcomes and to improve the survival outcomes of NSCLC.

In recent years, new advances in the bioapplication of nanomaterials substantially improved the diagnosis and treatment of tumors. (Guan et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021) Compared with conventional inorganic nanoparticles (NPs) and small molecule-based organic nanocarriers, polymers show excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability and minimal side effects on normal tissues. (Wang, 2016) Besides, polymer chemical structures can provide various responsive components for both external stimuli [such as light, (Hribar et al., 2011) radiofrequency, (Zhang et al., 2016) ultrasound, (Paris et al., 2015) and magnetic field (Mirvakili et al., 2020)] and internal states (such as pH, (Wang et al., 2016) temperature, (Zhang et al., 2020) enzyme, (Wei et al., 2016) and redox (Zhuang et al., 2018) environment). Recently, polypyrrole (PPy) NPs have extensively investigated as powerful photothermal agents exhibiting high photothermal conversion efficiency and exceptional photostability. (Zha et al., 2013) Meanwhile, PPy NPs are easy to fabricate, with low cost and high yield. (Phan et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018) And it is well known that iron oxide NPs are positive contrast agents for T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) due to their low toxicity and superior magnetic properties. (Wei et al., 2017) In this study, since Fe3+ ions are used as the oxidation agents to produce PPy NPs, many ferric (Fe3+) and ferrous ions (Fe2+) remain in the obtained PPy NPs. And Fe ions in the PPy NPs are selected as precursors for in situ formation of Fe3O4 crystals onto the surface of pre-synthesized PPy NPs. The final products (PPy@Fe3O4 NPs) possess both chemodynamic therapy (CDT) and photothermal therapy (PTT) functions, holding tremendous potential for remarkable efficiency to inhibit tumor growth. PTT, which uses photothermal agents to ablate tumors by converting absorbed light energy into intense localized heat, has attracted widespread attention as a non-invasive therapeutic technology. (Chen et al., 2019) On the other hand, CDT is an emerging therapy that generates toxic hydroxyl radicals (·OH) from endogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) using Fenton/Fenton-like reaction to control tumor progression in the tumor microenvironment (TME). (Tang et al., 2019) As generally known, compared with normal cells, cancer cells have special intracellular microenvironment with higher levels of H2O2 and weak acidity, which offers prerequisites to CDT application. (Yang et al., 2017, 2019; Shen et al., 2018) Thus, PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, which have noteworthy synergistic therapeutic effects, may play different roles in the growth and metastatic of NSCLC.

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex biopolymer mixture produced by different kinds of cells in the extracellular space. The ECM not only is crucial in cell adhesion and tissue organization, but also modulates cell differentiation, activation and migration. (Pickup et al., 2014; Eble and Niland, 2019) Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) belong to a large family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases that are involved in ECM degradation and play essential roles in cancer progression-associated pathways, including tumor growth, invasion and migration. (Gonzalez-Avila et al., 2019) Matrix metalloproteinase 2/9/13 (MMP2/9/13) are key members of the MMP family. Among these MMPs, MMP2 and MMP9 can selectively degrade type IV collagen, promoting tumor cells migrating through the basement membrane. (Wang et al., 2018) And MMP13 has the capability to degrade native collagen fibrillar types I, II, III, and VII and is related to the ECM remodeling. MMP2, MMP9 and MMP13 have been found upregulated and enhance the migration capability of lung cancer cells (Li et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020). Meanwhile, down-regulating the expression of MMP2, MMP9 aand MMP13 can reduce tumor cell growth, proliferation and metastasis (Tan et al., 2015; Poudel et al., 2016). We are wondering if PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could decrease the expression of MMP2, MMP9 and MMP13.

In this research, we examined the anti-tumor efficacy of the novel PPy@Fe3O4 NPs in vitro and in vivo. Our results displayed that the growth of tumors was considerably inhibited by the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, and the levels of MMP2, MMP9 and MMP13 decreased. These results demonstrated that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were excellent MRI-guided synergistic chemodynamic/photothermal cancer therapy agents and might be promising drugs to treat NSCLC because of inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

Polyvinyl alcohol 1788 (PVA; Alcoholysis degree: 87.0–89.0%), iron (III) chloride anhydrous (FeCl3; 99.9%) and pyrrole (99%) were purchased from Aladdin chemistry Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Absolute ethyl alcohol (C2H5OH; AR) and ammonium hydroxide solution (NH3·H2O; 28.0–30.0%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Deionized water (H2O) was prepared by a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, United States). All the chemical reagents were used without further purification.

Preparation of PPy@Fe3O4 Nanoparticles

We synthesized the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs by a very facile electrostatic adsorption method. First, PVA (0.75 g) was added in the deionized water (10 ml) and heated to 95°C until the solution was entirely dissolved. Later, FeCl3 (0.373g, 2.30 mmol) was mixed homogeneously with the above mixture under strong magnetic stirring for 1 h. Next, pyrrole monomer (69.2μl, 0.9970 mmol) was slowly dropped, and the reaction was maintained for 4 h at 4°C under magnetic stirring. The final solution turned dark green, indicating that PPy NPs were successfully synthesized. Subsequently, the solution (2.5 ml) was taken out, mixed with deionized water (15 ml) and ethanol (2 ml) under stirring at 70°C. Afterwards, 1 ml 1.0 wt% aqueous ammonia liquid was dropped into the solution followed by stirring for 30 min. Then 1 ml of 1.0 wt% aqueous ammonia liquid was added dropwise again, and the mixture lastly maintained for 30 min at 70°C. Finally, after being washed three times by deionized water, the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were collected by centrifugation (11000rpm) for 50 min.

Characterization of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs

The morphology and size of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were determined using a JEM-200 transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 200kV acceleration voltage. The characteristic functional group and crystal structures of nanomaterials were measured using Fourier-Transformed Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer and X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) respectively.

Photothermal Effect Evaluation

Briefly, aqueous solutions of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with different concentrations (100, 200 and 400 μg/ml) were separately irradiated by an 808 nm near-infrared (NIR) laser (1.0W/cm2). The temperature profiles were monitored and recorded using a thermal imaging camera (Fotric, Shanghai, China) over time. Then the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (400 μg/ml) solutions were irradiated with the NIR laser for 10 min, and cooled down to room temperature. Last, we calculated the photothermal conversion efficiency (η) by the temperature curves according to published study. (Leng et al., 2018)

Cytotoxicity Assay

We evaluated the cytotoxicity of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assays. In detail, normal human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) and Human lung adenocarcinoma cells (A549) were respectively seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 104 cells per well and cultured in pH7.4. The following day, we replaced the medium with fresh medium (pH7.4) containing the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs of different concentrations (25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μg/ml) for another 24 h. Then we changed the medium with 100 μl serum-free medium and 10 μl CCK-8 reagent. Following incubation for 2 h, we measured the absorbance value of wells at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo, United States). The calculated formulas were listed in Supplementary Material.

ROS Detection Assay

The A549 cells were incubated in the culture plates and divided into four groups: 1) control; 2) PPy@Fe3O4 (400 μg/ml); 3) H2O2 (100 μM); 4) PPy@Fe3O4 (400 μg/ml) + H2O2 (100 μM). After 24 h of treatment, we used the probe solution 2, 7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) to estimate the intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). After DCFH-DA treatment for 20 min, the cells were washed three times by phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffer and blank medium was added. Finally, we acquired images using Confocal laser scanning Microscopy (CLSM, Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany).

Anticancer Effect in vitro

The anti-cancer effect of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs was evaluated by the Calcine-AM/propidium iodide (PI) test (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and the Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis kit (Multi Sciences, Hangzhou, China). To investigate the PTT effect of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, A549 cells were incubated in the culture plates at pH6.5 and divided into 6 groups; group 1 with cells only; group 2 cultured with NIR only; group 3 cultured with H2O2 (100 μM) only; group 4 cultured with PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (400 μg/ml) + NIR; group 5 cultured with PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (400 μg/ml) + H2O2 (100 μM); group6 cultured with PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (400 μg/ml) + H2O2 (100 μM) + NIR. After incubation with PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (400 μg/ml) for 12 h, the cells of group 2,4 and 6 were exposed to an 808 nm NIR laser (1.0 W/cm2) for 10 min. Afterwards, we stained the A549 cells with Calcein-AM and PI for about 15 min, and images were acquired by CLSM.

And we detected cell apoptosis by Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis kit. The A549 cells in different groups were harvested and washed with PBS and Binding Buffer. Then the cells were resuspended in 500 μl Bind Buffer with 5 μl Annexin V-FITC and 10 μl PI solution to mix evenly for 5 min at room temperature in darkness. And we measured cell apoptosis immediately by flow cytometry (cytoflex LX, Beckman Coulter).

Transwell Migration Assay

In vitro migration assay, 24-well Transwell chambers with a polycarbonate filter membrane of 8 μm pore size (Corning, United States) were used to assess the effect of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on A549 cell migration. Cells were divided into control group and PPy@Fe3O4 group. After starvation of A549 cells for 24 h, we resuspended cells in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium and serumfree RPMI 1640 medium containing the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs at a concentration of 400 μg/ml respectively. Next, the A549 cells were inoculated into the upper chamber and the RPMI 1640 medium was placed in the lower chamber. After culturing for 24 h, the A549 cells that migrated to the bottom of the membranes were immobilized and stained with 1% crystal violet (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Finally, the migrated cells of each groups were counted under a microscope (Leica, Germany).

Western Blotting

A549 cells (5*105) were seeded into 6-well plate and divided into the control group and the PPy@Fe3O4 group (400 μg/ml). After incubation for 24 h, the cells were washed by PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer. Then we removed the cell debris by centrifugation, and the supernatants were harvested and stored at −80°C. Equivalent amounts of protein (25 µg) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto 0.22 um polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies including anti-MMP2/MMP9/MMP13 (Abclonal, China, 1:1,000 dilution) and anti-β-actin (Proteintech, China, 1:10,000 dilution). The following day, we washed the membranes three times for 10 min each time by Tris-buffered saline with Tween20 (TBST), and then incubated them in the corresponding secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP), goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP, 1:1,000, Affinity Biosciences, China) at room temperature for 2 h. Following washing three times for 10 min with TBST buffer, the membranes were treated with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, EpiZyme, Shanghai, China) reagent for exposure.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging in vivo

For in vivo MRI measurements, we intratumorally injected the A549 tumor-bearing mice with 200 μl of 3 mg/ml PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, when tumor size reached visible size (7–9 mm in diameter). Then we scanned the mice before and 3 h after injection. Thus, we successfully acquired the high-resolution T2-weighted MRI scan images of mice by a 3.0T MRI system (Ingenia 3.0T CX, Philips Healthcare). The T2-weighted MRI parameters were as follows: pulse waiting time (TR) = 2,800 ms, echo time (TE) = 60 ms, slice width (SW) = 5.0 mm.

Tumor Treatment in vivo

When the tumors reached 7–9 mm in diameter, we divided the mice into four groups (n = 6 per group): 1) control; 2) PBS + NIR; 3) PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (3 mg/ml); 4) PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (3 mg/ml) + NIR. The mice of group3 and 4 were injected intravenously with 200ul PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (3 mg/ml) and the mice of group2 was injected intravenously with 200ul PBS. Then 8 h after injection, the mice of group2 and 4 were irradiated with 808 nm laser (1W/cm2) for 10 min. Meanwhile, we measured the temperature changes of the tumor by a FLIR A300 thermal imaging camera. Simultaneously, tumor volume and body weight were monitored every 2 days. On day 14, the mice were sacrificed. Then the major organs were isolated for photograph or histological analysis (hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining), and the tumor was stained subsequently by immunohistochemistry (Ki67) and immunofluorescence (TUNEL).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

The tumor tissues specimens of mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and embedded in paraffin. Then the tissue blocks were cut into sections of 3-5 um thickness. For Ki67 staining, the sections were immunostained overnight at 4°C with an anti-Ki67 antibody (Abcam). After washing in PBS, the sections were subsequently incubated with the second antibody for 1 h. Then the slides were stained with 3, 3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and hematoxylin separately, dehydrated, and mounted. Images were captured using a microscope (Leica, Leica DMi8). For TUNEL staining, the proportion of apoptotic cells were performed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining kit (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). We obtained all images using a CLSM.

Statistical Analysis

All results and measurements were shown as the mean ± SD (standard deviation). Comparison between the mean values of different groups were analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student’s t-test: (*) p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; (**) p < 0.01 and (***) p < 0.001 was considered highly statistically significant; (****) p < 0.0001 was considered extremely statistically significant.

Results

Synthesis and Characterization of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs

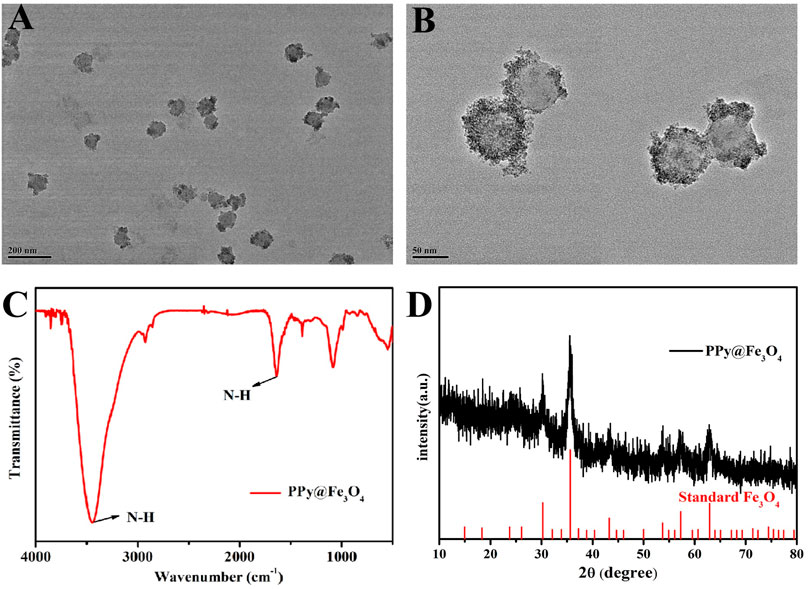

We used TEM to determine the sizes and morphologies of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. The PPy@Fe3O4 NPs are shown in Figure 1A, Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1. As we can see, the mean diameter of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs was measured to be 71.0 nm, and many tiny Fe3O4 nano-crystals were surface adsorbed on PPy NPs. The FTIR spectrum showed clearly the characteristic absorption peaks of PPy, indicating the successful formation of PPy (Figure 1C). And XRD patterns showed that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs had characteristic peaks (Figure 1D), which could be indexed to the Fe3O4 nanocrystals (JCPDS No. 65–3,107). (Wang et al., 2020) The above results demonstrated that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs had been successfully prepared.

FIGURE 1. The characterization of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. (A) Low- and (B) medium-magnification TEM image of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. (C) FTIR spectra of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. (D) XRD spectra of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs.

Photothermal Performance of PPy@Fe3O4 Nanaparticles

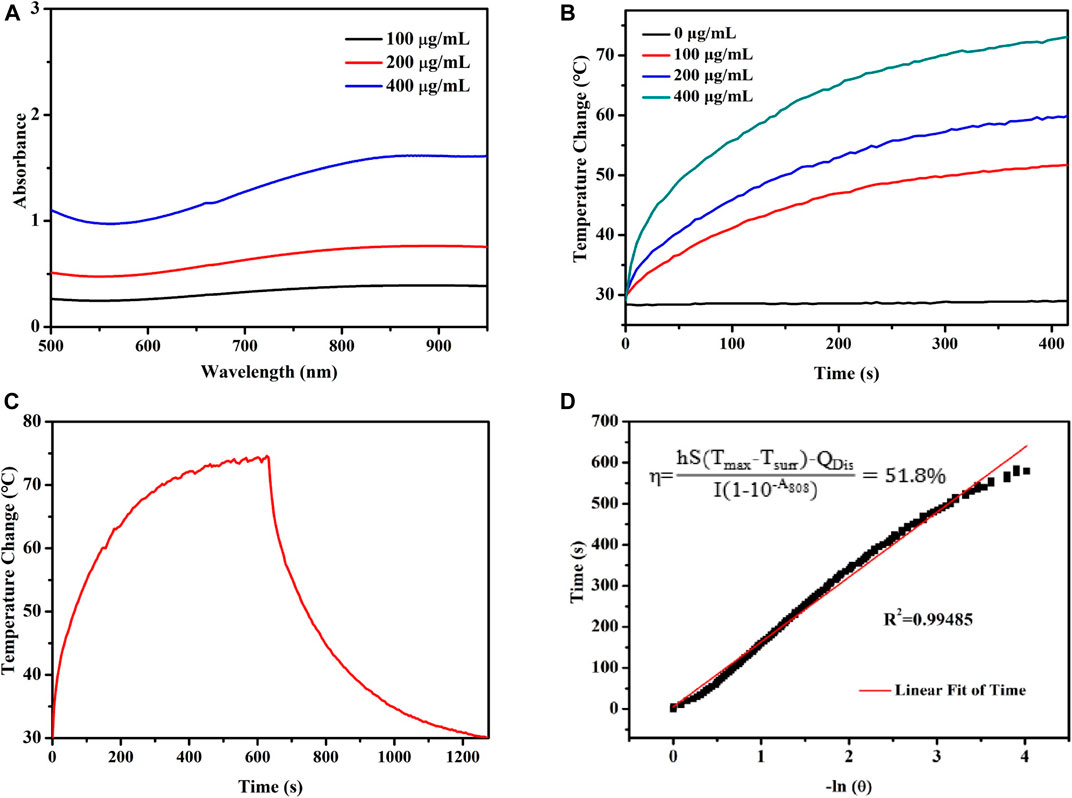

As shown in Figure 2A, the aqueous dispersion of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs had a broad absorption throughout the visible to the NIR region, which demonstrated that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were good potential PTT agents. We further evaluate the photothermal properties of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with NIR light irradiation. With the prolonging of the irradiation time and increased concentration of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, the temperature rose rapidly (Figure 2B). Finally, when the concentration of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs reached 400 μg/ml, the temperature reached about 70°C after 5 min of irradiation, which was high enough for irreversible tumor ablation (Figure 2C). Next, we tested the photothermal conversion efficiency (ŋ) of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, which can show the capability of converting energy of light into heat. As shown in Figure 2D, the ŋ value of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs was figured out to be ∼51.8%, which is much higher than traditional PTT agents, such as Cu2-xSe nanocrystals, Cu9S5 nanocrystals and Au nanorods. (Hessel et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2011)

FIGURE 2. Evaluation of the photothermal properties of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. (A) UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. (B) Temperature changes of PPy@Fe3O4 NCs at varying concentrations for 5 min with laser irradiation. (C) The curves of temperature increase with irradiation and nature cooling for PPy@Fe3O4 NCs solution (400 μg/ml). (D) Linear regression with a system time constant of the cooling curve shown in (C).

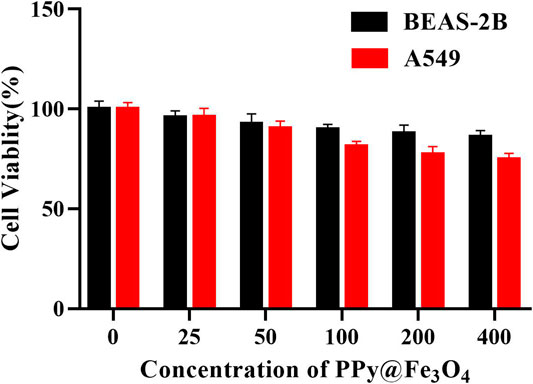

In vitro Cell Cytotoxicity Assay

To assess the cytotoxic effects of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, the CCK8 assay was performed on BEAS-2B and A549 cells. The cells were incubated with PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (0, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μg/ml) for 24 h to test the cell viability. The results indicated that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs exhibited lower cytotoxicity towards normal and cancer cells as high as 400 μg/ml (Figure 3), demonstrating that they have good biocompatibility.

FIGURE 3. Cell viability of A549 cells and BEAS-2B cells cultured with PPy@Fe3O4 NPs for 24 h at different concentrations.

The PPy@Fe3O4 NPs Increase Intracellular ROS Generation Induced by H2O2 and Induce Cell Apoptosis

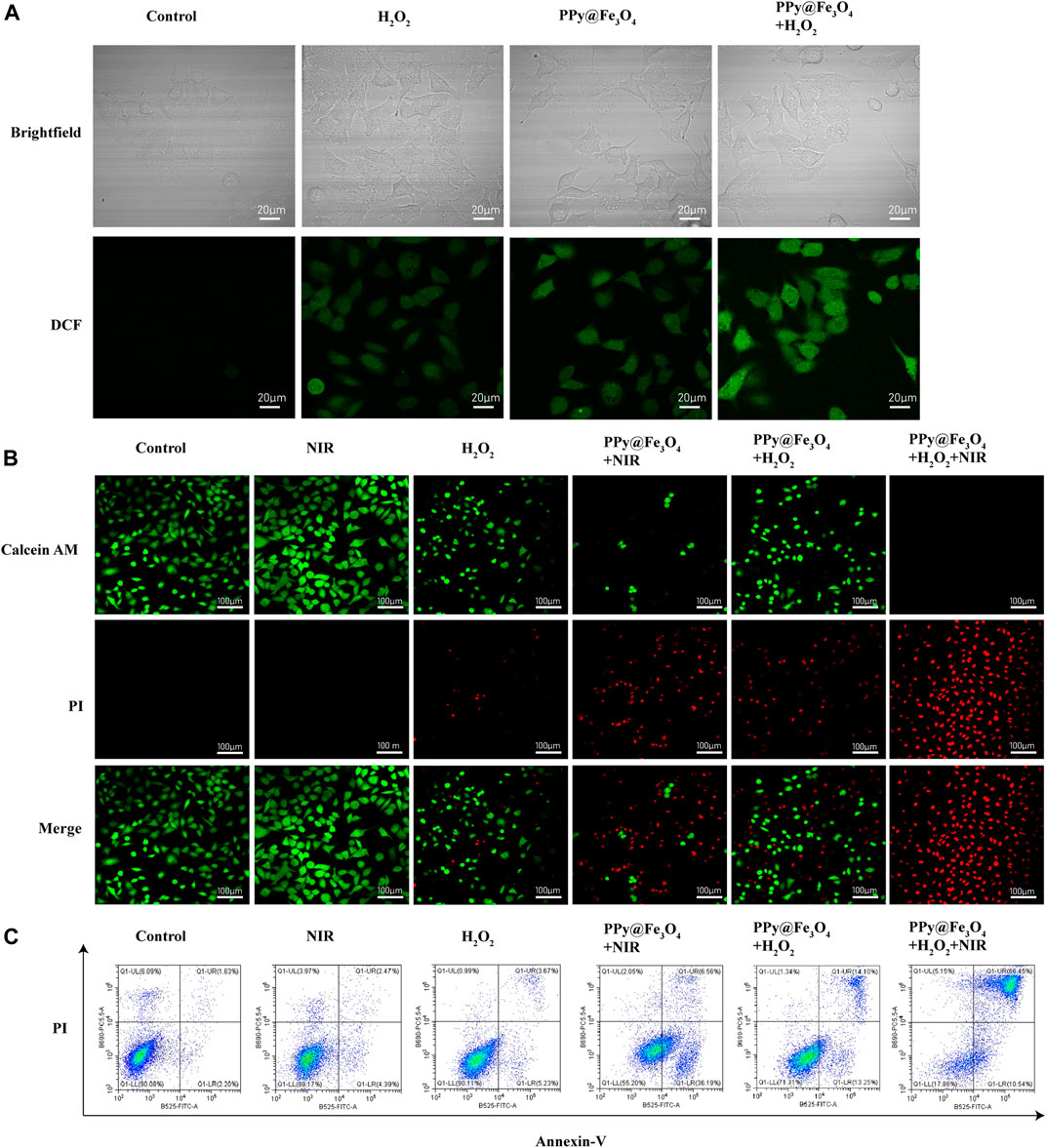

Chemodynamic therapy is an effective therapeutic treatment that causes damage of tumor cells by producing ROS. To examine the effects of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on ROS production, we detected ROS by fluorescent probe 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA), which was oxidized to 2, 7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) in the presence of ROS. As displayed in Figure 4A, compared with control group, the intensity of DCF fluorescence in H2O2 group and PPy@Fe3O4 NPs group increased weakly. When treated with both H2O2 and PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, the cells displayed strong and extensive green fluorescence, indicating that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could increase Fenton-induced ROS generation in the presence of H2O2.

FIGURE 4. The PPy@Fe3O4 NPs increase intracellular ROS generation induced by H2O2 and induce cell apoptosis. (A) Brightfield images and confocal images of ROS level in A549 cells. (B) Confocal images of Calcein-AM and PI co-stained A549 cells in different groups. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Cell apoptosis measured by flow cytometry.

Given the desirable photothermal conversion performance and significant synergistic effects, we further determined the in vitro therapeutic efficacy of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs through Calcine-AM/PI test. Living cells were stained with green fluorescent calcein AM, while dead cells were stained with red fluorescent PI (Figure 4B). Compared with the control group, A549 cells exhibited strong green fluorescence and no red fluorescence under exposure of NIR laser radiation, which indicated that the viability of the cells was not compromised. In contrast, H2O2 slightly increased the percentage of dead cells. And A549 cells showed a remarkable cell death after treatment by PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with NIR irradiation or PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with H2O2, suggesting that the photothermal therapy and chemodynamic therapy of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could effectively killed the A549 cells. When A549 cells were treated by the combination of PTT and CDT, very few living cells were observed. To sum up, PPy@Fe3O4NPs have satisfactory synergistic therapeutic effects.

We measured the influence of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on cell apoptosis by using Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure S2). The early apoptosis cells were defined as Annexin V (+)/PI (−), and cells in the late stage of were considered as Annexin V (+)/PI (+). The flow cytometry results showed that NIR group had no evident difference compared to the control group. Nevertheless, after treatment with H2O2, the percentage of apoptosis cells increased to 8.9%. After treatment by PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with NIR irradiation and PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with H2O2, the percentage of apoptosis cells significantly increased to 42.75% and 27.35%. And most surprisingly, the apoptosis rate in the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs + H2O2 + NIR group increased highly to 76.99%, which further demonstrated that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs + H2O2 + NIR group had the highest killing effect due to synergistic PTT and CDT.

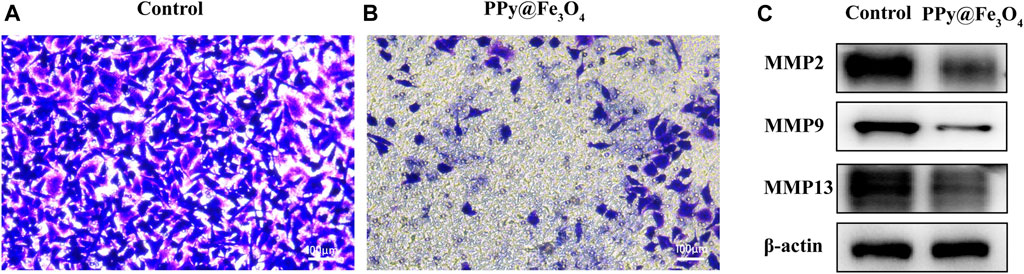

The PPy@Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Inhibit the Migration of Lung Cancer Cells and Decrease MMP2/MMP9/MMP13 Expression Levels

To assess cell mobility in response to the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, we used transwell cell cultures in vitro, which certified the effect of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on suppressing the migration of lung cancer cells (Figures 5A,B).

FIGURE 5. The PPy@Fe3O4 NPs inhibit the migration of human lung cancer cells. (A,B) The migration capacity of A549 cells measured using transwell assays after PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (400 μg/ml) treatment for 48 h. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Protein levels of MMP2/MMP9/MMP13 in different groups.

MMP2/9/13 had been found to play vital functions in the invasion and metastasis of malignant tumors. Therefore, we examined the impact of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on these protein expressions in A549 cells using western blotting (Figure 5C). The outcomes showed that the expressions of MMP2, MMP9 and MMP13 were obviously declined in the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs group compared to the control group. In summary, these experiments suggested that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could suppress the growth and metastasis of A549 cells.

The PPy@Fe3O4 Nanaparticles Inhibit the Growth of Xenograft Tumors in Nude Mice

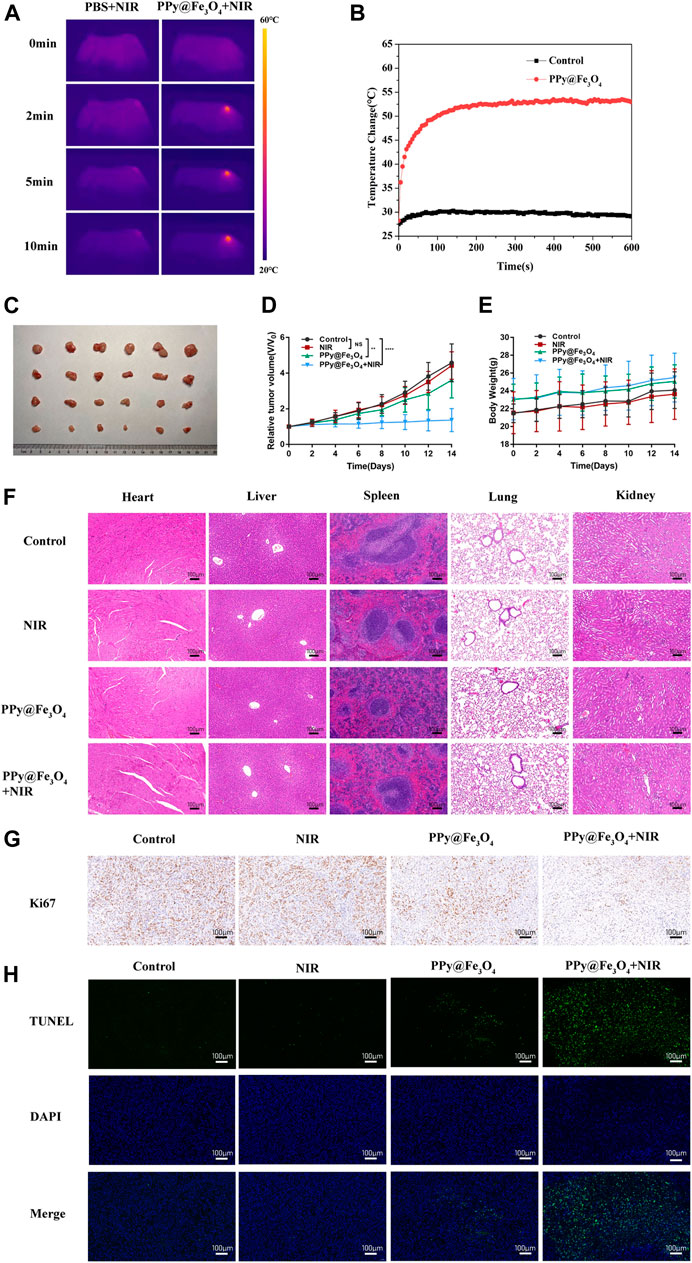

To identify the therapeutic efficacy of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on tumor growth in vivo, we conducted further comparative studies. 1 × 106 A549 cells were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice. When the volumes of tumors reached to approximately 100 mm3, we divided the mice into four groups randomly: 1) control; 2) PBS + NIR; 3) PPy@Fe3O4 NPs; 4) PPy@Fe3O4 NPs + NIR. Mice of the group 2 were injected with 200ul PBS via the tail vein, and mice of group 3, 4 were injected with PPy@Fe3O4 NPs (3 mg/ml) via the tail vein. After 8 h, the mice of group 2, 4 were irradiated by an 808 nm NIR laser (1.0W/cm2) for 10 min. Meanwhile, by using an infrared thermal camera, we found that the tumor temperature of mice injected with PPy@Fe3O4 NPs rapidly increased to ∼53°C during irradiation, which was sufficient for ablating tumors. However, the tumor temperature of the group 2 had negligible rise (Figures 6A,B). After 14 days, the mice were sacrificed and the tumor volumes and body weights were recorded (Figures 6C–E). The growth of tumors in group 2 was similar to the control group, demonstrating that NIR alone could not inhibit tumor growth. Whereas, tumor growth in the group 3 was partially inhibited due to CDT of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. Noticeably, the tumor growth in group 4 was substantially inhibited because of the synergistic effects of PTT and CDT. Representative pictures of the tumors in different groups further determined the therapeutic efficacy. There was no obvious difference in body weight among the groups, suggesting that the adverse effect of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs was negligible. Additionally, the main tissues and organs of different groups were collected for H&E staining to estimate the safety of various treatments (Figure 6F). We could not find evident damage in the group 2, 3, 4, compared to the control group, illustrating that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were biologically safe in vivo.

FIGURE 6. The PPy@Fe3O4 NPs inhibit the growth of tumor xenografts in nude mice. (A) Infrared thermography pictures of A549 tumor-bearing mice treated with PBS and PPy@Fe3O4 NPs under irradiation (808 nm, 1.0 W/cm2). (B) Profile of temperature variation of the tumor areas. (C) Tumor photo excised on day 14 after treatments. (D) Relative tumor volume and (E) body weight of mice in different groups. (F) H&E staining of main organs collected from mice in different groups. Scale bar, 100 μm. (G) Representative immunohistochemical stain images for Ki67 in xenograft tumors. Scale bar, 100 μm. (H) Representative TUNEL stain images in xenograft tumors. Blue color: DAPI staining for cell nuclei. Green color: positive apoptotic cells. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Next, we evaluated the proliferation and apoptosis of tumor cells by immunocytochemistry and immunofluorescence (Figures 6G,H). We noticed that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could slightly reduce the expression of the proliferation marker Ki67 and increase apoptosis, compared with the control group. Moreover, treatment of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with NIR further significantly decreased the level of Ki67 and caused cell apoptosis more effectively. These results clearly showed that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with NIR could suppress effectively tumor growth in vivo.

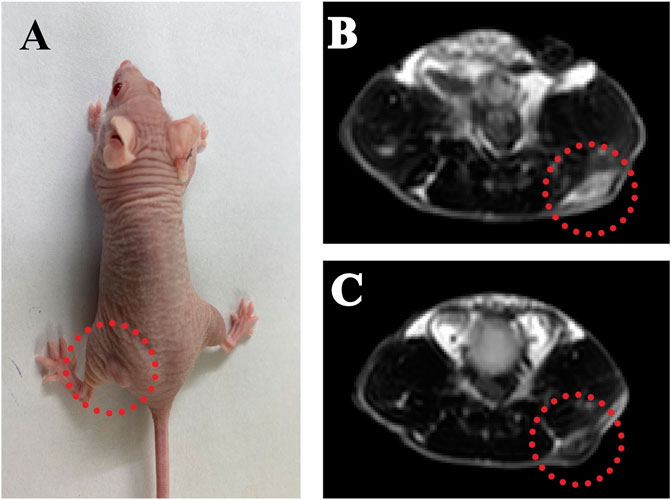

The PPy@Fe3O4 Nanoparticles can Serve as Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents to Detect Tumors

MRI offers excellent spatial resolution and tissue penetration, which is a noninvasive method for the identification and early cancer diagnosis. We used PPy@Fe3O4 NPs as contrast agents to evaluate the contrast-enhancing effect in vivo (Figure 7A). We treated the tumor-bearing mice with the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs by intratumor injection, and utilized T2 weighted MRI to observe the tumor before PPy@Fe3O4 NPs injection and 2 h post-injection (Figures 7B,C). Compared with pre-injection, we revealed that the signal intensity of tumor sites changed obviously 2 h after injection, which indicated that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs might be ideal contrast agents for MRI in future applications.

FIGURE 7. The PPy@Fe3O4 NPs can serve as MRI contrast agents to detect tumors. (A) Representative MRI images of A549 tumor-bearing mice; (B) T2-weighted MRI before and (C) after injection of PPy@Fe3O4 dispersions.

Discussion

For a long time, NSCLC has been a type of disease characterized by late diagnosis and resistance to therapy. (Hirsch et al., 2017) The greatest challenge in the modern nanomedicine of lung cancer is to develop promising tools for diagnosing and treating the advanced NSCLC owing to the rapid metastasis, which is the major impediment of successful treatments in the clinical procedures. Encouragingly, in this study, the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs showed satisfactory safety and efficacy as eminent photothermal agents for NSLC therapy. Additionally, we revealed that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could suppress the proliferation, migration and metastasis of cells of NSCLC.

Polypyrrole nanoparticle, a flexible and conductive polymer, is a recognized valuable multipurpose material due to its conductive properties, outstanding stability and high absorbance in the NIR region. Therefore, it can be used in various biomedical fields, especially in the therapy of cancer. (Chiang and Chuang, 2019) Nevertheless, because of some shortcomings of PPy, such as insolubility to water, the photothermal applications of PPy-based nanoparticles are still in the development. (Chen and Cai, 2015; He et al., 2018) For overcoming these shortcomings, we formed Fe3O4 crystals onto the surface of PPy NPs in this study. Fe3O4 greatly improved the solubility and could be used as T2 contrast agents in MRI to provide diagnostic information. (Wang et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2017) And we disclosed the synergistic therapeutic effects of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, including PTT and CDT. PPy@Fe3O4 NPs converted NIR light energy into heat energy and initiated the Fenton reaction under the mildly acidic conditions of the TME. Therefore, the apoptosis of cells would be induced and the growth and metastasis of cells would be inhibited.

In PTT, different kinds of photothermal agents contribute to the localized heating of cells and tissues. When irradiated by the light of appropriate wavelength, these agents absorb the photon energy and the singlet ground state could be converted to a singlet excited state. The excited electrons can go back to the ground state through vibrational relaxation, mediated by the interaction between the excited molecules and the surrounding molecules. Thus, the heating of the surrounding microenvironment appears due to increased kinetic energy. (Li X. et al., 2020) When the temperature reaches a certain value, cell necrosis will happen. (Knavel and Brace, 2013) Considering the high NIR photothermal conversion efficiency of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs, we performed a series of experiments to assess whether PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could be potential photothermal agents to inhibit the proliferation of lung cancer cells. We first studied the cytotoxicity of PPy NPs by CCK8 assay in vitro and the outcomes showed that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs had negligible cytotoxicity to BEAS-2B and A549 cells as high as 400 μg/ml. Additionally, our study showed that administration of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs did not induce damage to major organs, which reflected the safety of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs in vivo. The Safety and efficiency of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs demonstrated that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs might be perfect candidates for further clinical application of lung cancer. Then Annexin V-FITC/PI assay and Calcine-AM/PI test were performed to observe apoptosis induced by the PTT of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. The results indicated that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs had strong apoptosis-inducing effects on A549 cells under the condition of NIR irradiation. For in vivo experiments, the data showed that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs under the NIR irradiation condition obviously caused severe tumor damage while the adjacent normal tissue would not be affected. Meanwhile, the results of the Ki67 and TUNEL assay also demonstrated that PTT of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could inhibit growth and induce apoptosis of cells.

Chemodynamic therapy, which is regarded as in-situ treatment by Fenton and Fenton-like reactions, has received an increasing amount of attention. (Min et al., 2020) The highly oxidative •OH or O2 generated from Fenton and Fenton-like reactions, can be stimulated by the endogenous H2O2 of cancer cells and catalyzed by transition metal ions or their complexes. (Li Y. et al., 2020) Briefly, PPy@Fe3O4 NPs dissolve ferrous ions under the mildly acidic conditions of the TME and activate the Fenton reaction. The Haber–Weiss reaction is as follows:

On the one hand, excessive production of •OH can oxidize vital cellular constituents, such as DNA, proteins and lipids, which can induce cell apoptosis or necrosis. (Goldstein et al., 1993) On the other hand, O2 production mediated by Fenton reaction can alleviate tumor hypoxia, which may improve cancer therapeutic combination strategies. (Ma et al., 2016) As we all know, hypoxia is a crucial driver to drug resistance in tumor therapy. (Piao et al., 2017) Thus, the Fenton reaction can enhance the anticancer efficacy by supplying O2 to the hypoxic TME, when used with other anticancer methods. Additionally, iron ions exert a crucial role in the process of ferroptosis, where lipid ROS level increases due to the suppression of system xc- and glutathione (GSH) synthesis. (Liu et al., 2018) GSH is the major endogen antioxidant system that leads to a decrease of ROS. (Cajas et al., 2020) Herein, Fenton reaction-based nanomaterials are of great importance in lung cancer therapy. DCFH-DA fluorescence intensity assays showed that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs significantly increased ROS levels generated from A549 cells under the conditions of H2O2. We also found that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs promoted apoptosis of the cells of lung cancer induced by H2O2, as revealed by the Annexin V-FITC/PI assay and Calcine-AM/PI test. Therefore, the results of these experiments draw the following conclusion that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs could enhance antitumor effects through ROS damage.

Migration and invasion are two essential features of tumor metastasis. In metastasis, cancer cells invade and migrate from the primary site to the extracellular matrix and surrounding basement membrane, which further colonize the distant site. (Albuquerque et al., 2021) Therefore, the inhibition of migration and invasion could suppress the progression of lung cancer and extend the survival of patients. In our research, transwell chambers were established to confirm the inhibitory efficacy of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on A549 cell migration. The results showed that all PPy@Fe3O4 NPs significantly suppressed A549 cell migration. Moreover, tumor metastasis is a very complicated process that involves the interaction of various genes and proteins, especially MMPs. MMPs have been reported as proteolytic enzymes with the capacity of degrading the extracellular matrix components and other secreted proteins of the lungs. (Gonzalez-Avila et al., 2019) And they are also associated with endothelial basement membrane destruction. The crack in the basement membrane allows cells to enter the circulation, which transports the tumor cells to the distant extravasation site. (Bonomi, 2002) MMP2, MMP9 and MMP13 are prominent enzymes that promote tumor cell invasion and migration and regulate the progress of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is a transformation process of the epithelial cells to the mesenchymal cells and can promote cancer metastasis. (Scheau et al., 2019) Meanwhile, the levels of these proteins all had been reported to be elevated in certain lung cancer patients. (Li et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020) Here, our results indicated that MMP2, MMP9 and MMP13 were manifestly downregulated by PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. Thus, these findings suggested that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs suppressed human lung cancer cell metastasis.

Conclusion

In our study, we synthesized PPy@Fe3O4 NPs and demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs in vivo and in vitro. The PPy@Fe3O4 NPs exhibited excellent synergistic effects of PTT and CDT, which could inhibit the growth and metastasis of lung cancer cells efficiently. Additionally, the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs was remarkable MRI contrast agents for tumors. However, the underlying mechanisms of tumor growth and metastasis need to be further discussed. Taken together, our study revealed the potential of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs to develop a new therapeutic strategy for NSCLC.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The animal experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Shanghai General Hospital.

Author Contributions

DF and HJ designed and conducted a series of experiments. XH analyzed the experimental data. YS proofread the manuscript and the methods. ZL supervised the experiments and reviewed the manuscript. SB provided funding and supervised the experiments. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 81570018).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2021.789934/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviation

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; NPs, nanoparticles; PPy, polypyrrole; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PTT, photothermal therapy; CDT, chemodynamic therapy; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; ECM, extracellular matrix; TME, tumor microenvironment; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; PVA, Polyvinyl alcohol; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; FTIR, Fourier-Transformed Infrared; XRD, X-ray powder diffraction; NIR, near-infrared; CCK-8, cell counting kit-8; DCFH-DA, dichlorofluorescein-diacetate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; CLSM, Confocal laser scanning Microscopy; PI, propidium iodide; PVDF, polyvinylidene difluoride; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; TBST, Tris-buffered saline-Tween20; ECL, enhanced chemiluminescence; GSH, glutathione; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.

References

Albuquerque, C., Manguinhas, R., Costa, J. G., Gil, N., Codony-Servat, J., Castro, M., et al. (2021). A Narrative Review of the Migration and Invasion Features of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Cells upon Xenobiotic Exposure: Insights from In Vitro Studies. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 10, 2698–2714. doi:10.21037/tlcr-21-121

Bonomi, P. (2002). Matrix Metalloproteinases and Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors in Lung Cancer. Semin. Oncol. 29, 78–86. doi:10.1053/sonc.2002.31528

Cajas, Y. N., Cañón-Beltrán, K., Ladrón de Guevara, M., Millán de la Blanca, M. G., Ramos-Ibeas, P., Gutiérrez-Adán, A., et al. (2020). Antioxidant Nobiletin Enhances Oocyte Maturation and Subsequent Embryo Development and Quality. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5340. doi:10.3390/ijms21155340

Chen, F., and Cai, W. (2015). Nanomedicine for Targeted Photothermal Cancer Therapy: where Are We Now? Nanomedicine 10, 1–3. doi:10.2217/nnm.14.186

Chen, J., Ning, C., Zhou, Z., Yu, P., Zhu, Y., Tan, G., et al. (2019). Nanomaterials as Photothermal Therapeutic Agents. Prog. Mater. Sci. 99, 1–26. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.07.005

Chiang, C.-W., and Chuang, E.-Y. (2019). Biofunctional Core-Shell Polypyrrole–Polyethylenimine Nanocomplex for a Locally Sustained Photothermal with Reactive Oxygen Species Enhanced Therapeutic Effect against Lung Cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 14, 1575–1585. doi:10.2147/IJN.S163299

Eble, J. A., and Niland, S. (2019). The Extracellular Matrix in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 36, 171–198. doi:10.1007/s10585-019-09966-1

Goldstein, S., Meyerstein, D., and Czapski, G. (1993). The Fenton Reagents. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 15, 435–445. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(93)90043-t

Gonzalez-Avila, G., Sommer, B., Mendoza-Posada, D. A., Ramos, C., Garcia-Hernandez, A. A., and Falfan-Valencia, R. (2019). Matrix Metalloproteinases Participation in the Metastatic Process and Their Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications in Cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 137, 57–83. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.02.010

Guan, S., Liu, X., Fu, Y., Li, C., Wang, J., Mei, Q., et al. (2022). A Biodegradable "Nano-Donut" for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Enhanced Chemo/Photothermal/Chemodynamic Therapy through Responsive Catalysis in Tumor Microenvironment. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 608, 344–354. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.09.186

Han, L., Sheng, B., Zeng, Q., Yao, W., and Jiang, Q. (2020). Correlation between MMP2 Expression in Lung Cancer Tissues and Clinical Parameters: a Retrospective Clinical Analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 20, 283. doi:10.1186/s12890-020-01317-1

He, Y., Gui, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Liao, S., and Wang, Y. (2018). A Polypyrrole Elastomer Based on Confined Polymerization in a Host Polymer Network for Highly Stretchable Temperature and Strain Sensors. Small 14, 1800394. doi:10.1002/smll.201800394

Herbst, R. S., Morgensztern, D., and Boshoff, C. (2018). The Biology and Management of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Nature 553, 446–454. doi:10.1038/nature25183

Hessel, C. M., Pattani, V. P., Rasch, M., Panthani, M. G., Koo, B., Tunnell, J. W., et al. (2011). Copper Selenide Nanocrystals for Photothermal Therapy. Nano Lett. 11, 2560–2566. doi:10.1021/nl201400z

Hirsch, F. R., Scagliotti, G. V., Mulshine, J. L., Kwon, R., Curran, W. J., Wu, Y.-L., et al. (2017). Lung Cancer: Current Therapies and New Targeted Treatments. Lancet 389, 299–311. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30958-8

Hribar, K. C., Lee, M. H., Lee, D., and Burdick, J. A. (2011). Enhanced Release of Small Molecules from Near-Infrared Light Responsive Polymer−Nanorod Composites. ACS Nano 5, 2948–2956. doi:10.1021/nn103575a

Knavel, E. M., and Brace, C. L. (2013). Tumor Ablation: Common Modalities and General Practices. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 16, 192–200. doi:10.1053/j.tvir.2013.08.002

Leng, C., Zhang, X., Xu, F., Yuan, Y., Pei, H., Sun, Z., et al. (2018). Engineering Gold Nanorod-Copper Sulfide Heterostructures with Enhanced Photothermal Conversion Efficiency and Photostability. Small 14, 1703077. doi:10.1002/smll.201703077

Li, W., Jia, M., Wang, J., Lu, J., Deng, J., Tang, J., et al. (2019). Association of MMP9-1562C/T and MMP13-77A/G Polymorphisms with Non-small Cell Lung Cancer in Southern Chinese Population. Biomolecules 9, 107. doi:10.3390/biom9030107

Li, X., Lovell, J. F., Yoon, J., and Chen, X. (2020a). Clinical Development and Potential of Photothermal and Photodynamic Therapies for Cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 657–674. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0410-2

Li, Y., Zhao, P., Gong, T., Wang, H., Jiang, X., Cheng, H., et al. (2020b). Redox Dyshomeostasis Strategy for Hypoxic Tumor Therapy Based on DNAzyme‐Loaded Electrophilic ZIFs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22537–22543. doi:10.1002/anie.202003653

Liu, T., Liu, W., Zhang, M., Yu, W., Gao, F., Li, C., et al. (2018). Ferrous-Supply-Regeneration Nanoengineering for Cancer-cell-specific Ferroptosis in Combination with Imaging-Guided Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Nano 12, 12181–12192. doi:10.1021/acsnano.8b05860

Luo, J., Zhu, H., Jiang, H., Cui, Y., Wang, M., Ni, X., et al. (2018). The Effects of Aberrant Expression of LncRNA DGCR5/miR‐873‐5p/TUSC3 in Lung Cancer Cell Progression. Cancer Med. 7, 3331–3341. doi:10.1002/cam4.1566

Ma, Z., Zhang, M., Jia, X., Bai, J., Ruan, Y., Wang, C., et al. (2016). FeIII-Doped Two-Dimensional C3N4Nanofusiform: A New O2-Evolving and Mitochondria-Targeting Photodynamic Agent for MRI and Enhanced Antitumor Therapy. Small 12, 5477–5487. doi:10.1002/smll.201601681

Min, H., Qi, Y., Zhang, Y., Han, X., Cheng, K., Liu, Y., et al. (2020). A Graphdiyne Oxide‐Based Iron Sponge with Photothermally Enhanced Tumor‐Specific Fenton Chemistry. Adv. Mater. 32, 2000038. doi:10.1002/adma.202000038

Mirvakili, S. M., Ngo, Q. P., and Langer, R. (2020). Polymer Nanocomposite Microactuators for On-Demand Chemical Release via High-Frequency Magnetic Field Excitation. Nano Lett. 20, 4816–4822. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c00648

Nasim, F., Sabath, B. F., and Eapen, G. A. (2019). Lung Cancer. Med. Clin. North Am. 103, 463–473. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.006

Oser, M. G., Niederst, M. J., Sequist, L. V., and Engelman, J. A. (2015). Transformation from Non-small-cell Lung Cancer to Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Molecular Drivers and Cells of Origin. Lancet Oncol. 16, e165–e172. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71180-5

Paris, J. L., Cabañas, M. V., Manzano, M., and Vallet-Regí, M. (2015). Polymer-Grafted Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as Ultrasound-Responsive Drug Carriers. ACS Nano 9, 11023–11033. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5b04378

Phan, T. T. V., Bui, N. Q., Cho, S.-W., Bharathiraja, S., Manivasagan, P., Moorthy, M. S., et al. (2018). Photoacoustic Imaging-Guided Photothermal Therapy with Tumor-Targeting HA-FeOOH@PPy Nanorods. Sci. Rep. 8, 8809. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-27204-8

Piao, W., Hanaoka, K., Fujisawa, T., Takeuchi, S., Komatsu, T., Ueno, T., et al. (2017). Development of an Azo-Based Photosensitizer Activated under Mild Hypoxia for Photodynamic Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13713–13719. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b05019

Pickup, M. W., Mouw, J. K., and Weaver, V. M. (2014). The Extracellular Matrix Modulates the Hallmarks of Cancer. EMBO Rep. 15, 1243–1253. doi:10.15252/embr.201439246

Poudel, B., Ki, H.-H., Luyen, B. T. T., Lee, Y.-M., Kim, Y.-H., and Kim, D.-K. (2016). Triticumoside Induces Apoptosis via Caspase-dependent Mitochondrial Pathway and Inhibits Migration through Downregulation of MMP2/9 in Human Lung Cancer Cells. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 48, 153–160. doi:10.1093/abbs/gmv124

Riihimäki, M., Hemminki, A., Fallah, M., Thomsen, H., Sundquist, K., Sundquist, J., et al. (2014). Metastatic Sites and Survival in Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer 86, 78–84. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.07.020

Rosell, R., and Karachaliou, N. (2015). Relationship between Gene Mutation and Lung Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 34, 243–248. doi:10.1007/s10555-015-9557-1

Scheau, C., Badarau, I. A., Costache, R., Caruntu, C., Mihai, G. L., Didilescu, A. C., et al. (2019). The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Anal. Cell Pathol. 2019, 9423907. doi:10.1155/2019/9423907

Shen, Z., Song, J., Yung, B. C., Zhou, Z., Wu, A., and Chen, X. (2018). Emerging Strategies of Cancer Therapy Based on Ferroptosis. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704007. doi:10.1002/adma.201704007

Tan, M., Gong, H., Wang, J., Tao, L., Xu, D., Bao, E., et al. (2015). SENP2 Regulates MMP13 Expression in a Bladder Cancer Cell Line through SUMOylation of TBL1/TBLR1. Sci. Rep. 5, 13996. doi:10.1038/srep13996

Tang, Z., Liu, Y., He, M., and Bu, W. (2019). Chemodynamic Therapy: Tumour Microenvironment‐Mediated Fenton and Fenton‐like Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 946–956. doi:10.1002/anie.201805664

Tian, Q., Jiang, F., Zou, R., Liu, Q., Chen, Z., Zhu, M., et al. (2011). Hydrophilic Cu9S5 Nanocrystals: a Photothermal Agent with a 25.7% Heat Conversion Efficiency for Photothermal Ablation of Cancer Cells In Vivo. ACS Nano 5, 9761–9771. doi:10.1021/nn203293t

Wang, L., Li, J., Jiang, Q., and Zhao, L. (2012). Water-soluble Fe3O4 Nanoparticles with High Solubility for Removal of Heavy-Metal Ions from Waste Water. Dalton Trans. 41, 4544–4551. doi:10.1039/c2dt11827k

Wang, W., Wang, B., Ma, X., Liu, S., Shang, X., and Yu, X. (2016). Tailor-Made pH-Responsive Poly(choline Phosphate) Prodrug as a Drug Delivery System for Rapid Cellular Internalization. Biomacromolecules 17, 2223–2232. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00455

Wang, X., Yang, B., She, Y., and Ye, Y. (2018). The lncRNA TP73‐AS1 Promotes Ovarian Cancer Cell Proliferation and Metastasis via Modulation of MMP2 and MMP9. J. Cel Biochem. 119, 7790–7799. doi:10.1002/jcb.27158

Wang, X., Liu, X., Xiao, C., Zhao, H., Zhang, M., Zheng, N., et al. (2020). Triethylenetetramine-modified Hollow Fe3O4/SiO2/chitosan Magnetic Nanocomposites for Removal of Cr(VI) Ions with High Adsorption Capacity and Rapid Rate. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 297, 110041. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110041

Wang, M. (2016). Emerging Multifunctional NIR Photothermal Therapy Systems Based on Polypyrrole Nanoparticles. Polymers 8, 373. doi:10.3390/polym8100373

Wei, X., Luo, Q., Sun, L., Li, X., Zhu, H., Guan, P., et al. (2016). Enzyme- and pH-Sensitive Branched Polymer-Doxorubicin Conjugate-Based Nanoscale Drug Delivery System for Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 8, 11765–11778. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b02006

Wei, H., Bruns, O. T., Kaul, M. G., Hansen, E. C., Barch, M., Wiśniowska, A., et al. (2017). Exceedingly Small Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as Positive MRI Contrast Agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 2325–2330. doi:10.1073/pnas.1620145114

Woodman, C., Vundu, G., George, A., and Wilson, C. M. (2021). Applications and Strategies in Nanodiagnosis and Nanotherapy in Lung Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 69, 349–364. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.02.009

Yang, G., Xu, L., Chao, Y., Xu, J., Sun, X., Wu, Y., et al. (2017). Hollow MnO2 as a Tumor-Microenvironment-Responsive Biodegradable Nano-Platform for Combination Therapy Favoring Antitumor Immune Responses. Nat. Commun. 8, 902. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01050-0

Yang, Y., Wang, C., Tian, C., Guo, H., Shen, Y., and Zhu, M. (2018). Fe3O4@MnO2@PPy Nanocomposites Overcome Hypoxia: Magnetic-Targeting-Assisted Controlled Chemotherapy and Enhanced Photodynamic/photothermal Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 6, 6848–6857. doi:10.1039/c8tb02077a

Yang, B., Liu, Q., Yao, X., Zhang, D., Dai, Z., Cui, P., et al. (2019). FePt@MnO-Based Nanotheranostic Platform with Acidity-Triggered Dual-Ions Release for Enhanced MR Imaging-Guided Ferroptosis Chemodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 11, 38395–38404. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b11353

Zha, Z., Yue, X., Ren, Q., and Dai, Z. (2013). Uniform Polypyrrole Nanoparticles with High Photothermal Conversion Efficiency for Photothermal Ablation of Cancer Cells. Adv. Mater. 25, 777–782. doi:10.1002/adma.201202211

Zhang, K., Li, P., He, Y., Bo, X., Li, X., Li, D., et al. (2016). Synergistic Retention Strategy of RGD Active Targeting and Radiofrequency-Enhanced Permeability for Intensified RF & Chemotherapy Synergistic Tumor Treatment. Biomaterials 99, 34–46. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.014

Zhang, Y., Yan, J., Avellan, A., Gao, X., Matyjaszewski, K., Tilton, R. D., et al. (2020). Temperature- and pH-Responsive Star Polymers as Nanocarriers with Potential for In Vivo Agrochemical Delivery. ACS Nano 14, 10954–10965. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c03140

Zhao, H., Wang, J., Li, X., Li, Y., Li, C., Wang, X., et al. (2021). A Biocompatible Theranostic Agent Based on Stable Bismuth Nanoparticles for X-ray Computed Tomography/magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Enhanced Chemo/photothermal/chemodynamic Therapy for Tumours. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 604, 80–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.06.174

Keywords: PPy@Fe3O4 nanoparticles, photothermal therapy, chemodynamic therapy, non-small cell lung cancer, tumor metastasis

Citation: Fang D, Jin H, Huang X, Shi Y, Liu Z and Ben S (2021) PPy@Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Inhibit Tumor Growth and Metastasis Through Chemodynamic and Photothermal Therapy in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Chem. 9:789934. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.789934

Received: 05 October 2021; Accepted: 20 October 2021;

Published: 08 November 2021.

Edited by:

Houjuan Zhu, Institute of Materials Research and Engineering (A∗STAR), SingaporeReviewed by:

Yanyan Jiang, Shandong University, ChinaYu Luo, Shanghai University of Engineering Sciences, China

Copyright © 2021 Fang, Jin, Huang, Shi, Liu and Ben. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Suqin Ben, YmVuc3VxaW4wMTJAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Zeyu Liu, bGl1emV5dTE3OTlAZ21haWwuY29t

†These authors contributed equally to the paper

Danruo Fang

Danruo Fang Hansong Jin

Hansong Jin Xiulin Huang

Xiulin Huang Yongxin Shi1

Yongxin Shi1 Zeyu Liu

Zeyu Liu Suqin Ben

Suqin Ben