- 1Department of Chemistry, Inorganic Chemistry Section, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India

- 2Henkel Limited, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Chemistry and Environment, Heritage Institute of Technology, Kolkata, India

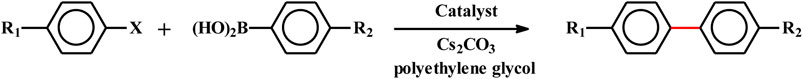

Reaction of [Rh(PPh3)3Cl] with two Schiff base ligands, viz. N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)furan-2-aldimine (H2L1) and N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)thiophene-2-aldimine (H2L2), in refluxing toluene affords organorhodium complexes of type [Rh(PPh3)2(L)Cl] (L = L1 and L2). Similar reaction with [Ir(PPh3)3Cl] yields organoiridium complexes of type [Ir(PPh3)2(L) (H)] (L = L1 and L2). Crystal structures of [Rh(PPh3)2(L1)Cl] and [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] have been determined, where the imine ligands are found to bind to the metal centers as CNO-donors. Structures of [Rh(PPh3)2(L2)Cl] and [Ir(PPh3)2(L1) (H)] have been optimized by density functional theory method. Formation of the organometallic complexes is believed to proceed via C-H and O-H bond activation of the imine ligands. All four complexes show intense absorptions in the visible and ultraviolet regions. Cyclic voltammetry on the complexes shows an oxidation on the positive side of SCE and a reduction on the negative side. The organoiridium complexes are found to efficiently catalyze Suzuki-type C-C cross coupling reactions.

Introduction

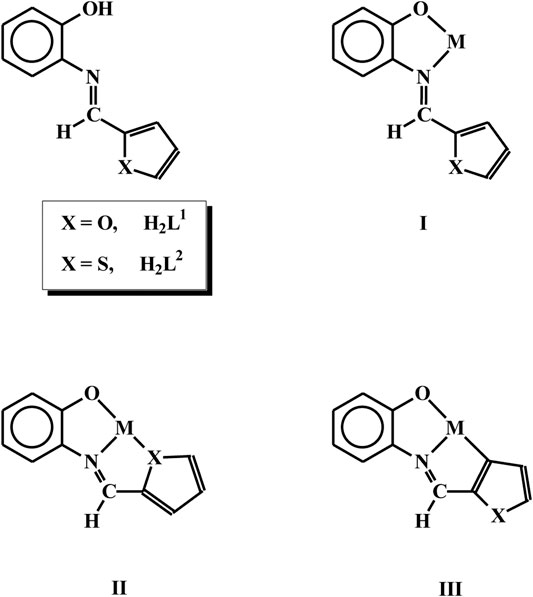

The chemistry of rhodium and iridium has been receiving considerable current attention (Chi et al., 2017; Colombo et al., 2020; Mao et al., 2020; Shaikh et al., 2020; Alsalahi and Trzeciak, 2021; Davison et al., 2021; Monti et al., 2021; Vuuren et al., 2021), largely because of the interesting properties exhibited by the complexes of these metals. As properties of the complexes are dictated primarily by the coordination environment around the metal center, complexation of rhodium by ligands of selected types has been of significant importance, and the present work has originated from our interest in this area (Dutta et al., 2000a; Dutta et al., 2000b; Das et al., 2002; Dutta et al., 2002; Acharyya et al., 2004a; Acharyya et al., 2004b; Acharyya et al., 2005; Acharyya et al., 2006; Basu et al., 2006; Baksi et al., 2007a; Basu et al., 2007; Baksi et al., 2007b; Dasgupta et al., 2008; GuhaRoy et al., 2008; Acharyya et al., 2009; GuhaRoy et al., 2009; Baksi et al., 2010; Basu et al., 2010; Majumder et al., 2011; Seth and Bhattacharya, 2011; Bhattacharya et al., 2012; Paul and Bhattacharya, 2012; Sengupta and Bhattacharya, 2013; Paul et al., 2014). Herein we have selected two Schiff base ligands, viz. N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)furan-2-aldimine (H2L1) and N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)thiophene-2-aldimine (H2L2), derived from 2-aminophenol and, furan-2-aldehyde and thiophene-2-aldehyde respectively. The selected ligands may, in principle, bind to metal ions in three possible modes (I, II and III). We were particularly interested to induce binding mode III via metal mediated C-H bond activation of these imine ligands. With this target in mind, we selected a rhodium(I) complex [Rh(PPh3)3Cl], and an analogous iridium(I) complex [Ir(PPh3)3Cl], as the metal precursors. In our earlier studies we experienced the ability of these two complexes in bringing about C-H bond activation of organic ligands (Dutta et al., 2000b; Dutta et al., 2002; Acharyya et al., 2004b; Acharyya et al., 2005; Basu et al., 2006; Baksi et al., 2007a; Paul and Bhattacharya, 2012; Paul et al., 2014). It is relevant to mention here that metal-mediated C-H bond activation is of significant interest, with particular reference to synthesis of targeted organic molecules (Kumar et al., 2017; Zhu and Zhou, 2017; Cheng et al., 2019; Woźniak et al., 2020; Dongbang et al., 2021; Rej et al., 2021). Reaction of the rhodium and iridium starting materials with the two selected Schiff base ligands has indeed afforded organorhodium and organoiridium complexes. The chemistry of all these complexes is reported here, with particular reference to their formation, structure and catalytic application.

Experimental

Materials

Rhodium trichloride and iridium trichloride were purchased from Arora Matthey, Kolkata, India. [Rh(PPh3)3Cl] and [Ir(PPh3)3Cl] were prepared by following reported methods (Osborn and Wilkinson, 1967; Acharyya et al., 2004b). Furan-2-carbaldehyde, thiophene-2-carbaldehyde, and 2-aminophenol were obtained from SRL, AVRA Synthesis and Merck, respectively. The two aldimine ligands (H2L1 and H2L2) were prepared by reacting equimolar mixture 2-aminophenol and the respective aldehyde in hot ethanol. Tetrabutylammonium hexaflurophosphate (TBHP), obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and AR grade acetonitrile, procured from Merck, India, were used for electrochemical work. All other chemicals and solvents were reagent grade commercial materials and were used as received.

Syntheses of Complexes

[Rh(PPh3)2(L1)Cl]: N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)furan-2-aldimine (20 mg, 0.11 mmol) was dissolved in hot toluene (30 ml) and [Rh(PPh3)3Cl] (100 mg, 0.11 mmol) was added to it. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 6 h producing a purple solution. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to give a purple solid, which was purified by thin layer chromatography on a silica plate. Using benzene as the eluant a major purple band separated, which was extracted with acetonitrile. Evaporation of this purple extract gave [Rh(PPh3)2(L1)Cl] as a crystalline solid. Yield: 62 mg (68%). Anal. Calc. for C47H37NO2P2ClRh: C, 66.56; H, 4.37; N, 1.65. Found: C, 66.18; H, 4.28; N, 1.63%. 1H NMR: 5.69 (d, H), 6.17 (t, H, J = 3.9 Hz), 6.26 (d, H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.56 (t, H), 6.62 (d, H), 6.99 (d, H), 7.18–7.23 (PPh3), 7.64–7.70 (H + PPh3)*. IR: 3452, 3057, 2924, 2854, 1744, 1637, 1591, 1533, 1479, 1435, 1403, 1317, 1267, 1188, 1122, 1094, 1030, 999, 841, 746, 694, 538 and 519 cm−1.

[Rh(PPh3)2(L2)Cl]: N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)thiophene-2-aldimine (22 mg, 0.11 mmol) was dissolved in hot toluene (30 ml) and [Rh(PPh3)3Cl] (100 mg, 0.11 mmol) was added to it. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 6 h producing a pink solution. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to give a pink solid, which was purified by thin layer chromatography on a silica plate. Using 1:10 acetonitrile-benzene as the eluant a major pink band separated, which was extracted with acetonitrile. Evaporation of this pink extract gave [Rh(PPh3)2(L2)Cl] as a crystalline solid. Yield: 56 mg (60%). Anal. Calc. for C47H37NOP2SClRh: C, 65.32; H, 4.28; N, 1.62. Found: C, 65.29; H, 4.22; N, 1.61%. 1H NMR 1: 5.68 (d, H, J = 3.8 Hz), 6.32 (t, H, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.15–7.20 (H + PPh3)*, 7.28 (t, H), 7.48 (d, H, J = 4.9 Hz), 7.56–7.66 (H + PPh3), 7.83 (s, H). IR: 3433, 3055, 2924, 2854, 1661, 1589, 1553, 1464, 1433, 1402, 1315, 1273, 1180, 1121, 1094, 1028, 996, 937, 856, 744, 696, 535 and 517 cm−1.

[Ir(PPh3)2(L1) (H)]: N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)furan-2-aldimine (19 mg, 0.10 mmol) was dissolved in hot toluene (30 ml) and [Ir(PPh3)3Cl] (100 mg, 0.10 mmol) was added to it. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 24 h to produce a purple solution. The solvent was evaporated to give a purple solid, which was purified by thin layer chromatography on a silica plate. Using 1:10 hexane-benzene as the eluant a major purple band separated, which was extracted with acetonitrile. Evaporation of this purple extract gave [Ir(PPh3)2(L1) (H)] as a crystalline solid. Yield: 62 mg (70%). Anal. Calc. for C47H38NO2P2Ir: C, 62.51; H, 4.21; N, 1.55. Found: C, 62.64; H, 4.23; N, 1.53%. 1H NMR 1: -13.76 (t, hydride, J = 32.4 Hz), 5.69 (d, H), 6.17 (t, H, J = 3.9 Hz), 6.26 (d, H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.56 (t, H), 6.62 (d, H), 6.99 (d, H), 7.18–7.23 (PPh3), 7.64–7.70 (H + PPh3)*. IR : 3435, 3055, 2924, 2854, 2160, 1747, 1636, 1593, 1542, 1485, 1435, 1385, 1312, 1261, 1178, 1130, 1059, 1032, 998, 836, 746, 696, 538 and 518 cm−1.

[Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)]: N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)thiophene-2-aldimine (20 mg, 0.10 mmol) was dissolved in hot toluene (30 ml) and [Ir(PPh3)3Cl] (100 mg, 0.10 mmol) was added to it. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 24 h to produce a purple solution. The solvent was evaporated to give a purple solid, which was purified by thin layer chromatography on a silica plate. Using 1:10 hexane-benzene as the eluant a major purple band separated, which was extracted with acetonitrile. Evaporation of this purple extract gave [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] as a crystalline solid. Yield: 59 mg (65%). Anal. Calc. for C47H38NOP2SIr: C, 61.42; H, 4.14; N, 1.52. Found: C, 61.37; H, 4.16; N, 1.54%. 1H NMR: −13.52 (t, hydride, J = 34.5 Hz), 5.90 (t, H, J = 4.5 Hz), 6.06–6.11 (m, 2H), 6.16 (d, H, J = 8.1 Hz), 6.50 (t, H, J = 4.7 Hz), 6.64 (d, H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.20–7.33 (PPh3), 7.53–7.63 (H + PPh3)*. IR: 3462, 3057, 2924, 2854, 2060, 1748, 1635, 1591, 1537, 1479, 1435, 1385, 1308, 1273, 1182, 1094, 1032, 998, 839, 744, 698, 539 and 519 cm−1.

Physical Measurements

Microanalyses (C, H, N) were performed using a Heraeus Carlo Erba 1108 elemental analyzer. Mass spectra were recorded with a Micromass LCT electrospray (Qtof Micro YA263) mass spectrometer. Magnetic susceptibilities were measured using a Sherwood MK-1 balance. IR spectra were obtained on a Perkin-Elmer 783 spectrometer with samples prepared as KBr pellets. Electronic spectra were recorded on a JASCO V-570 spectrophotometer. 1H NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solution with a Bruker Avance DPX 300 NMR spectrometer using TMS as the internal standard. Electrochemical measurements were made using a CH Instruments model 600A electrochemical analyzer. A platinum disc working electrode, a platinum wire auxiliary electrode and an aqueous saturated calomel reference electrode (SCE) were used in the cyclic voltammetry experiments. All electrochemical experiments were performed under a dinitrogen atmosphere at 298 K. Optimization of ground-state structures and energy calculations for all the complexes were carried out by density functional theory (DFT) method using the Gaussian 09 package (Frisch et al., 2009). GC-MS analyses were performed using a Perkin Elmer CLARUS 680 instrument.

X-Ray Crystallography

Single crystals of the complex [Rh(PPh3)2(L1)Cl] and [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] were grown by slow evaporation of an acetonitrile solution of the respective complexes. Selected crystal data and data collection parameters are given in Supplementary Table S1. Data on the crystal were collected on a Bruker SMART CCD diffractometer using graphite monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). X-ray data reduction, structure solution and refinement were done using SHELXS-97 and SHELXL-97 programs (Sheldrick, 1997). The structures were solved by the direct methods.

Application as Catalyst

General Procedure for Suzuki Coupling Reactions

In a typical run, an oven-dried 10 ml round bottom flask was charged with a known mol percent of catalyst and base, phenylboronic acid (1.2 mmol) and aryl halide (1 mmol) with the appropriate solvents (4 ml). The flask was placed in a preheated oil bath at required temp. After the specified time the flask was removed from the oil bath and water (20 ml) added, followed by extraction with ether (4 × 10 ml). The combined organic layers were washed with water (3 × 10 ml), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and filtered. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in hexane and analyzed by GCMS.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structure

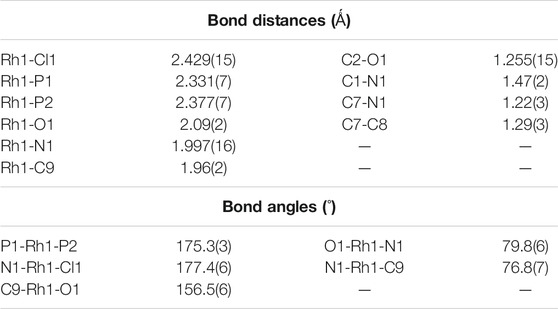

As delineated in the introduction, the initial goal of the present study has been to synthesize mixed-ligand rhodium and iridium complexes of the two selected ligands, viz. N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)furan-2-aldimine (H2L1) and N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)thiophene-2-aldimine (H2L2) and find out their mode of binding to the metal center. We began with reactions of the imine-ligands (H2L1 and H2L2) with [Rh(PPh3)3Cl], which proceeded smoothly in refluxing toluene to afford complexes of type [Rh(PPh3)2(L)Cl] (L = L1 and L2) in decent yields. Preliminary characterizations (microanalysis, IR, NMR, etc.) on these complexes indicated presence of an imine-ligand, a chloride and two triphenylphosphines in the coordination sphere. In order to find out stereochemistry of these complexes, as well as to ascertain coordination mode of the imine-ligands in them, structure of [Rh(PPh3)2(L1)Cl], was determined by X-ray crystallography. The structure is shown in Figure 1 and some relevant bond parameters are listed in Table 1. The structure revealed that the N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)furan-2-aldimine ligand is coordinated to rhodium in the tridentate CNO-mode (III; M = Rh, X = O), via loss of two protons, viz. the hydroxyl proton and a C-H proton from the furan ring. The CNO-coordinated imine ligand, rhodium and chloride constitute one equatorial plane of the octahedron with rhodium at the center, where the chloride is trans to the coordinated imine-nitrogen. The two triphenylphosphines have taken up the remaining two axial positions and hence they are mutually trans. The CNOP2Cl coordination sphere around rhodium is distorted octahedral in nature, which is reflected in all the bond parameters (Table 1) around the metal center. The Rh-C, Rh-N, Rh-O, Rh-P and Rh-Cl distances are all quite normal (Dutta et al., 2000b; Basu et al., 2006; Baksi et al., 2007a). Crystal structure of [Rh(PPh3)2(L2)Cl] could not be determined as good quality crystals of it could not be grown even after repeated attempts. However, its structure was optimized by DFT calculations. The DFT-optimized structure of [Rh(PPh3)2(L2)Cl] (Supplementary Figure S1) is found to be similar to the crystal structure of [Rh(PPh3)2(L1)Cl], and the computed bond parameters (Supplementary Figure S2) are also comparable to those found in [Rh(PPh3)2(L1)Cl]. Besides, we recorded mass spectrum of the [Rh(PPh3)2(L2)Cl] complex, which shows a distinct peak at M/z = 863.99 (Supplementary Figure S2), which corresponds to [M + H]+ and is consistent with the composition of this complex.

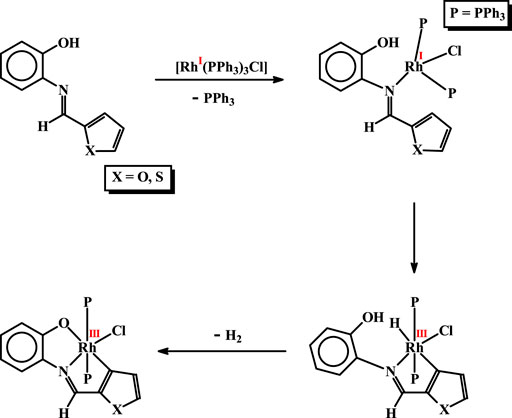

Formation of the organorhodium complexes, viz. [Rh(PPh3)2(L1)Cl] and [Rh(PPh3)2(L2)Cl], from the reaction of [Rh(PPh3)3Cl] with the imine ligands (H2L1 and H2L2), has been quite intriguing. Some speculated sequences behind formation of these complexes, that seem probable, are illustrated in Scheme 1. In the initial step the imine-nitrogen of the H2L ligand seems to bind to the metal center in [Rh(PPh3)3Cl], via displacement of a PPh3, to generate an intermediate. In the next step C-H activation at the 3-position of the heterocyclic ring takes place, whereby oxidative insertion of rhodium into the C-H bond takes place generating a hydrido-rhodium(III) species. Such rhodium(I) assisted C-H bond activation is well documented in the literature (Wiedemann et al., 2006; Gardiner et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2021; Lou et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021). The rhodium-bound hydride then interacts with the nearby phenolic O-H fragment, which leads to abstraction of the O-H proton and furnish the final product via elimination of molecular hydrogen. It is interesting to see that in spite of the presence of a recognized donor atom in the heterocyclic ring of the imine ligands, it did not participate in coordination. Instead, C-H activation from the same heterocyclic ring takes place. This is attributable to ability of the rhodium(I) center to activate a proximal C-H bond.

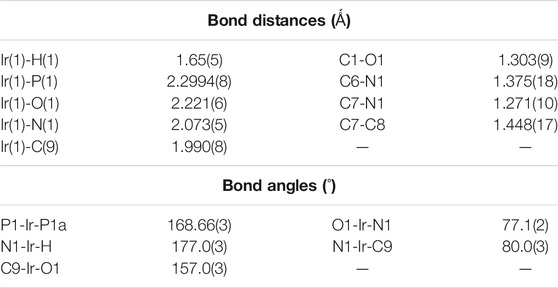

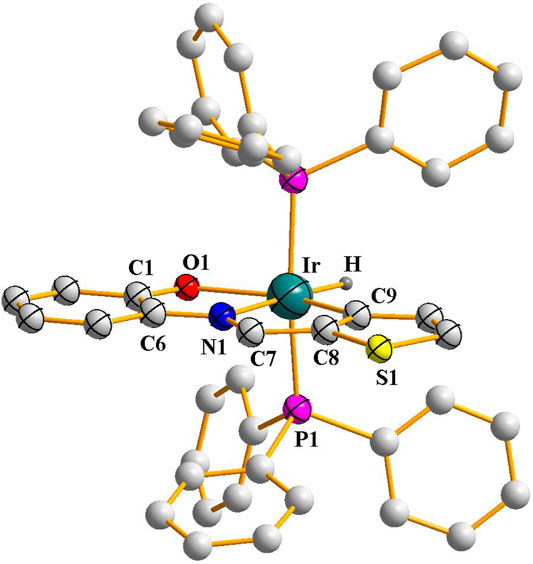

Successful synthesis of the organorhodium complexes from the reaction of [Rh(PPh3)3Cl] with the two selected imine ligands, H2L1 and H2L2, prompted us to explore analogous iridium reactions. Accordingly, reaction of [Ir(PPh3)3Cl] was carried out with the imine ligands in refluxing toluene, which afforded complexes of type [Ir(PPh3)2(L) (H)] (L = L1 and L2) in good yields. The reflux needed to be continued for a longer period of time for achieving optimum yield of the complexes. Preliminary characterizations (microanalysis, IR, NMR, etc.) on these complexes were found to correspond well with their compositions. Crystal structure of [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] was determined (Figure 2), which shows that the N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)thiophene-2-aldimine ligand is bound to iridium in the tridentate CNO-mode (III; M = Ir, X = S) via O-H and C-H bond cleavage. Unlike the rhodium complexes, a hydride ligand is found to be coordinated to iridium, and the rest of the structure is qualitatively similar to the that of the rhodium complexes. The Ir-C, Ir-N, Ir-O, Ir-P and Ir-H distances (Table 2) are all quite normal (Acharyya et al., 2004b). Crystal structure determination of [Ir(PPh3)2(L1) (H)] was not possible owing to unavailability of crystals of appropriate quality. Hence its structure was optimized by DFT method, and the DFT-optimized structure (Supplementary Figure S3; Supplementary Table S3) is found to be similar to the crystal structure of [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)]. The mass spectrum of the [Ir(PPh3)2(L1) (H)] complex (Supplementary Figure S4) that shows a distinct peak at M/z = 903.86 consistent with [M + H]+ also supports the composition of this complex.

FIGURE 2. Crystal structure of [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] (hydrogen atoms, except the hydride hydrogen coordinated to iridium, are omitted for clarity).

A formation scheme for the [Ir(PPh3)2(L) (H)] (L = L1 and L2) complexes is presented in (Supplementary Scheme S1), which is similar to that for the organorhodium complexes (Scheme 1). The only difference being in the disposition of the coordinated hydride and chloride in the Rh(III) and Ir(III) intermediates, an interesting feature observed earlier by us in similar reactions (Dutta et al., 2000a; Acharyya et al., 2004b; Basu et al., 2006; Baksi et al., 2007a; Paul and Bhattacharya, 2012; Paul et al., 2014), and this is attributable primarily to difference in the experimental conditions. In the last step, elimination of HCl takes place, which is believed to be facilitated by the closeness of Ir-Cl bond to the phenolic O-H fragment in the iridium(III) intermediate, and thus the organoiridium complexes are obtained as end products. It is relevant to mention here that like rhodium(I), iridium(I) is also known to bring about C-H bond activation (Boutry et al., 1997; Tang et al., 2009; Press et al., 2016; Hung et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Slack and Colacot, 2021; Yoshino and Matsunaga, 2021).

Spectral Properties

Magnetic susceptibility measurements show that all four complexes are diamagnetic, which corresponds to the trivalent state of rhodium and iridium (low-spin d6, S = 0) in these complexes. 1H NMR spectra of the complexes were recorded in CDCl3 solution, which show broad signals within 7.15–7.70 ppm for the coordinated PPh3 ligands. The hydride signal in [Ir(PPh3)2(LL2) (H)] and [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] complexes is observed respectively at −13.52 ppm and -13.76 ppm as a distinct triplet due to coupling with two equivalent phosphorus nuclei with a coupling constant of ∼19 Hz. Most of the expected aromatic proton signals, as well as the azomethine-proton signal, from the coordinated imine-ligand are clearly observed in the expected region, while a few could not be detected due to their overlap with other signals in the same region.

Infrared spectra of the rhodium and iridium complexes show many bands of different intensities in the 400–4000 cm−1 region. No attempt has been made to assign each individual band to a specific vibration. However, comparison with the spectra of the corresponding uncoordinated imine ligands shows that the O-H stretch, observed near 3377 cm−1 in the uncoordinated ligands, is absent in the complexes. Three prominent bands, observed near 518, 695 and 745 cm−1 in all the complexes, are attributed to the coordinated triphenylphosphine ligands. Several sharp bands are also observed in the [Rh(PPh3)2(L)Cl] and [Ir(PPh3)2(L) (H)] (L = L1 and L2) complexes, which were absent in the [M(PPh3)3Cl] (M = Rh and Ir), and hence these are attributed to the coordinated imine-ligands. Infrared spectra of [Ir(PPh3)2(L1) (H)] and [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] show a sharp band at 2161 cm−1 and 2060 cm−1 respectively, which are attributed to Ir-H stretch.

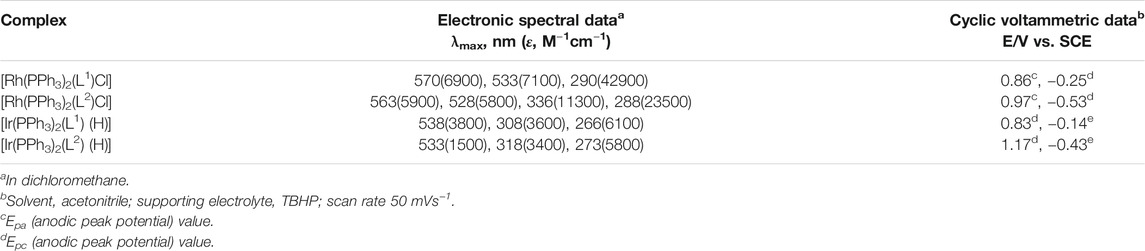

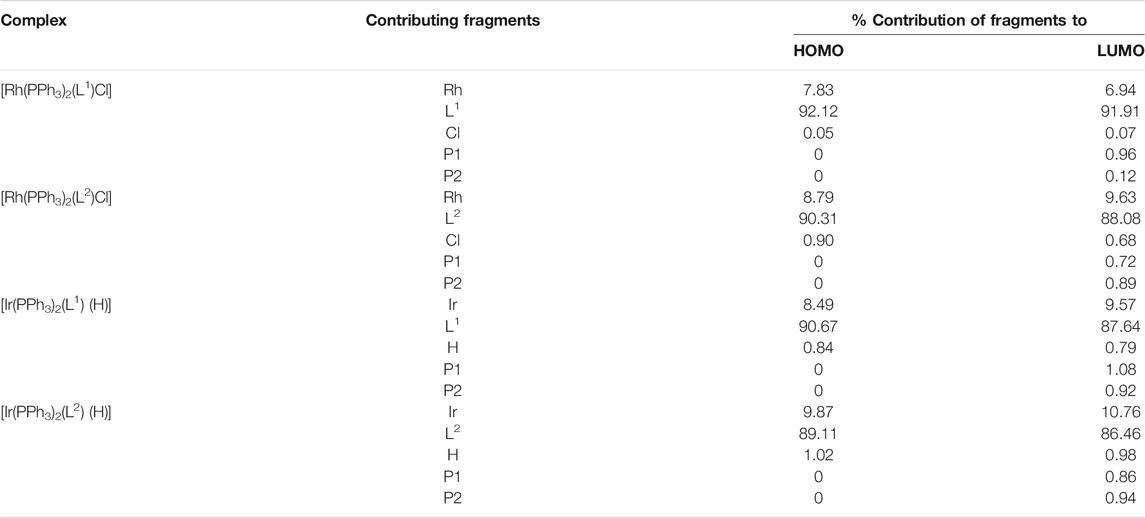

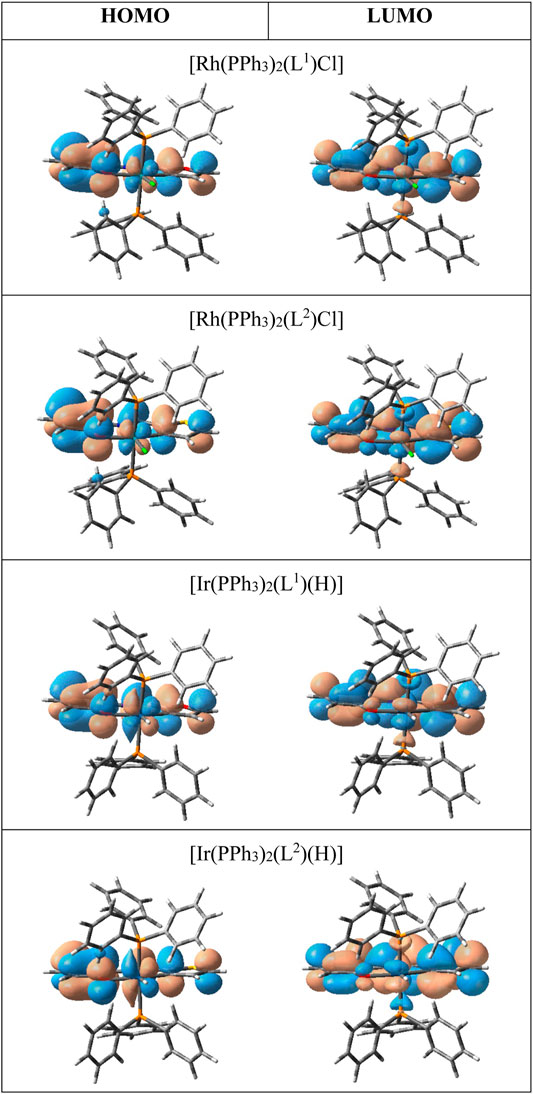

All four complexes are highly soluble in organic solvents like benzene, dichloromethane, acetonitrile, etc., producing intense pink solution. Electronic spectra of the complexes were recorded in dichloromethane solutions. Spectral data are presented in Table 3. The complexes show several intense absorptions in both the visible and ultraviolet regions. The absorptions in the ultraviolet region are attributable to transitions within the ligand orbital. To have an insight into the nature of absorptions in the visible region, DFT calculations were performed on the complexes. Structures of all four complexes were optimized through DFT calculations, and nature of the two Frontier orbitals, viz. the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), was examined. Compositions of the HOMO and LUMO for all four complexes are given in Table 4, and contour plots of these orbitals in the complexes are shown in Figure 3. In all the complexes the HOMO and LUMO are found to be concentrated mostly over the imine-ligand, with much less contribution from the metal center. Hence the lowest energy absorption in the visible region is attributable largely to a transition within these filled and vacant orbitals of the imine ligand.

Electrochemical Properties

Electrochemical properties of the rhodium and iridium complexes were studied by cyclic voltammetry in acetonitrile solution (0.1 M TBHP). Voltammetric data are given in Table 3 and two selected voltammogram are shown in (Supplementary Figure S5). All four complexes show an irreversible oxidative response on the positive side of SCE and an irreversible reductive response on the negative side. Similar cyclic voltammetric responses were observed before for organorhodium and organoiridium complexes of similar type (Dutta et al., 2000a; Acharyya et al., 2004b; Basu et al., 2006; Baksi et al., 2007a; Paul and Bhattacharya, 2012; Paul et al., 2014). In view of composition of the HOMO in all these complexes, the oxidative response is assigned to oxidation of the coordinated imine-ligand. Similarly, based on the composition of the LUMO, the reduction is assigned to reduction of the coordinated imine-ligand.

Catalytic Properties

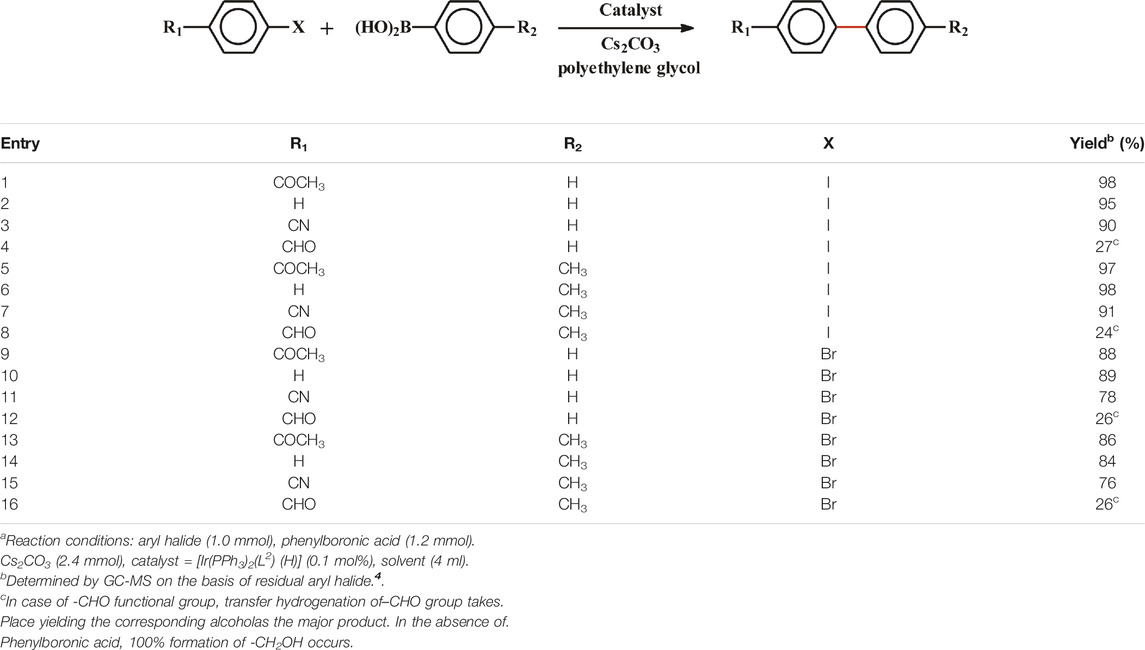

Metal center in complexes having ability to undergo two-electron transfer reaction should, in principle, be capable of serving as catalyst for bringing about C-C cross coupling reactions. Palladium complexes are familiar examples of such catalysts (Corbet and Mignani, 2006; Gu et al., 2019; Sebastian and Morales, 2019; Dickmu and Smoliakova, 2020; Lutz and Morandi, 2021). Rhodium and iridium centers in the present group of complexes may also be expected to display such catalytic property, as they can also undergo two-electron transfer reactions. With this expectation we examined the catalytic potential of these rhodium and iridium complexes towards Suzuki type C-C cross-coupling reaction. Initially, coupling reaction between phenylboronic acid and p-iodoacetophenone was tried to yield the corresponding biphenyl product. All the experimental parameters were systematically varied to achieve an optimum yield of the product, and after extensive optimization (Supplementary Table S4) it was found that 0.1 mol% [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] complex as catalyst, Cs2CO3 (2.4 mmol) as base, polyethylene glycol as solvent, a reaction temperature of 120°C, and a reaction time of 4 h, furnished an excellent (98%) yield of the expected product (entry 1). With the other iridium complex, viz. [Ir(PPh3)2(L1) (H)], as catalyst, the product was obtained in slightly lower yield (entry 11). However, the rhodium complexes were found to be much less effective as catalyst, where the product was obtained in poor yields (entries 12 and 13). Hence only the results obtained with [Ir(PPh3)2(L2) (H)] complex as the catalyst precursor are reported here.

The scope of the C-C coupling reaction is summarized in Table 5. Using the optimized the reaction conditions, C-C coupling reaction was performed by varying both the arylhalide and the arylboronic acid. Four different aryliodides and the corresponding four aryl bromides, and two aryl boronic acids (viz. phenylboronic acid and p-tolylboronic acid) were used in the coupling reactions. From majority of the reactions the expected bi-aryls were obtained in good (76–98%) yields, resulting in an average turn-over number of ∼ 103. Reactions with arylhalides having a–CHO group afforded the biaryls in rather poor (24–27%) yields (entries 4, 8, 12, and 16). These aryl aldehydes were found to get reduced to the corresponding alcohols, which were obtained as the major product. Catalytic transfer hydrogenation of aldehyde seems to have taken place in PEG as the solvent. In similar reactions carried out in the absence of any aryl boronic acid, the alcohols corresponding to the p-halobenzaldehydes were obtained as the only product in excellent (≥95%) yields.

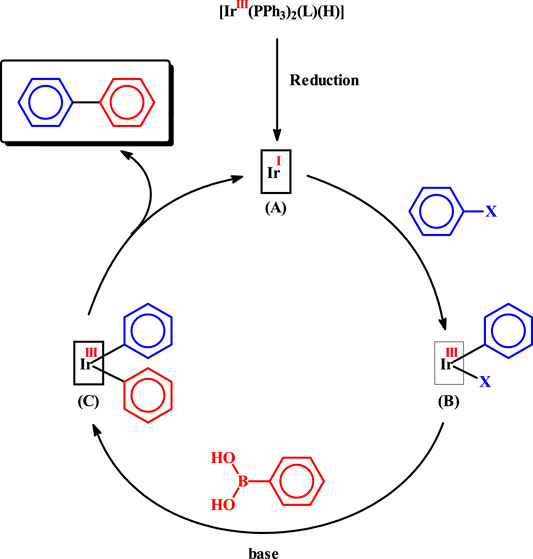

The observed catalytic C-C coupling reactions are believed to follow the sequences shown in Scheme 2, which are essentially similar to those known for the palladium-catalyzed reactions. In the initial step, the [Ir(PPh3)2(L) (H)] catalyst-precursor (L = L1 or L2) undergoes a two-electron reduction reaction to generate an iridium(I) species 2, depicted as A, and thus entry into the catalytic cycle takes place. The exact nature of A is not clear at this moment. However, the soft triphenylphosphines, the hydride, and the nitrogen of the imine-ligand are likely to remain coordinated to the iridium(I) center in A. In the following step, oxidative addition of aryl halide takes place generating an iridium(III) species, represented as B. Transmetalation happens next, producing another iridium(III) species, depicted as C. Finally reductive elimination of the biaryl product takes place, along with simultaneous regeneration of species A, and the catalytic cycle thus continues.

Though the observed catalytic efficiency of the iridium complexes is not that great compared to that of the well-known palladium catalysts, it is pleasing to see that iridium complexes are also capable of catalyzing C-C coupling reactions under relatively mild experimental condition. Another noticeable aspect of the observed catalysis is that no additional ligands were necessary for the cross-coupling reactions 3. Presence of a soft hydride ligand in the iridium(III) pre-catalyst [Ir(PPh3)2(L) (H)], might be helpful for its relatively facile reduction to generate the catalytically active iridium(I) species (A). Similar reduction of the rhodium(III) complexes [Rh(PPh3)2(L)Cl], with a chloride instead of the hydride, was presumably not so favorable. And this difference in composition of the pre-catalysts accounts for the observed difference in catalytic efficiency of the iridium and rhodium complexes.

Conclusion

The present study shows that the two selected imine-ligands, H2L1 and H2L2, can readily undergo rhodium and iridium mediated activation of the C-H and O-H bonds producing organometallic complexes. Interestingly, the available donor atom X (X = O or S) in the heterocyclic ring of the imine-ligands is found to remain unreactive, whereas a C-H bond in the same ring underwent cleavage. The iridium complexes serve as efficient catalyst precursor for Suzuki type about C-C cross coupling reactions. It is worth mentioning in this context that though iridium complexes are known to serve as photocatalyst for C-C coupling reactions of some other types (Donabauer and Konig, 2021), iridium-catalyzed Suzuki type C-C coupling appears to be unprecedented.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

Financial assistance received from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi (Sanction No. 01(2994)/19/EMR-II) and JU-RUSA 2.0 program (Ref. No.: R-11/96/19) is gratefully acknowledged. The DST-FIST and DST-PURSE programs of the Department of Chemistry, Jadavpur University, are also gratefully acknowledged for providing financial and infrastructural supports. PD. thanks the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, for his fellowship (Grant Nos.: 09/096(0839)/2015-EMR-I).

Conflict of Interest

PS was employed by Henkel Limited.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2021.696460/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Chemical shifts for all NMR data are given in ppm and the multiplicity of the signals, along with the associated coupling constant(s), is given in parentheses. Overlapping signals are marked with an asterisk (*).

2The solvent and/or base served as the reducing agent.

3Attempted reactions with additional phosphine ligands did not have any positive effect on the catalytic reactions.

References

Acharyya, R., Basuli, F., Peng, S. M., Lee, G. H., Wang, R. Z., Mak, T. C. W., et al. (2005). Iridium Mediated Methyl and Phenyl C-H Activation of 2-(arylazo)phenols. Synthesis, Structure, and Spectral and Electrochemical Properties of Some Organoiridium Complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 690, 3908–3917. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.05.025

Acharyya, R., Basuli, F., Rosair, G., and Bhattacharya, S. (2004). Synthesis, Structure and Electrochemical Properties of Some Oxime Complexes of Rhodium. New J. Chem. 28, 115–119. doi:10.1039/B309412J

Acharyya, R., Basuli, F., Wang, R. Z., Mak, T. C. W., and Bhattacharya, S. (2004). Iridium(III) Complexes Formed by O-H And/or C-H Activation of 2-(Arylazo)phenols. Inorg. Chem. 43, 704–711. doi:10.1021/ic034785w

Acharyya, R., Dutta, S., Basuli, F., Peng, S. M., Lee, G. H., Falvello, Larry. R., et al. (2006). Rhodium Assisted C-H Activation of Benzaldehyde Thiosemicarbazones and Their Oxidation via Activation of Molecular Oxygen. Inorg. Chem. 45, 1252–1259. doi:10.1021/ic050505w

Acharyya, R., Peng, S. M., Lee, G. H., and Bhattacharya, S. (2009). Iridium Mediated Phenolic O-H Activation and Cyclometalation of 2-(naphthyl-1′-Azo)-4-Methylphenol - Formation of Organoiridium Complexes. J. Chem. Sci. 121, 387–395. Permanent link: https://www.ias.ac.in/article/fulltext/jcsc/121/04/0387-0395.

Alsalahi, W., and Trzeciak, A. M. (2021). Rhodium-catalyzed Hydroformylation under green Conditions: Aqueous/organic Biphasic, “On Water”, Solventless and Rh Nanoparticle Based Systems. Coord. Chem. Rev. 430, 213732. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213732

Baksi, S., Acharyya, R., Basuli, F., Peng, S. M., Lee, G. H., Nethaji, M., et al. (2007). Rhodium-Mediated C–C Bond Activation of 2-(2′,6′-Dialkylarylazo)-4-Methylphenols. Elimination and Migration of Alkyl Groups. Organometallics 26, 6596–6603. doi:10.1021/om700826t

Baksi, S., Acharyya, R., Dutta, S., Blake, A. J., Drew, M. G. B., and Bhattacharya, S. (2007). Interaction of 2-(arylazo)phenols with Rhodium. Usual Coordination vs. C-H and C-C Activation. J. Organomet. Chem. 692, 1025–1032. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.10.063

Baksi, S., Seth, D. K., Tadesse, H., Blake, A. J., and Bhattacharya, S. (2010). Interaction of 2-(2ʹ,6ʹ-Dialkylphenylazo)-4-Methylphenols with Iridium. C-H Activation and Migration of Alkyl Group. J. Organomet. Chem. 695, 1111–1118. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.01.015

Basu, S., Acharyya, R., Basuli, F., Peng, S. M., Lee, G. H., Mostafa, G., et al. (2010). Iridium Assisted S-H and C-H Activation of Benzaldehyde Thiosemicarbazones. Synthesis, Structure and Electrochemical Properties of the Resulting Complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 363, 2848–2856. doi:10.1016/j.ica.2010.04.009

Basu, S., Acharyya, R., Sheldrick, W. S., Figge, H. M., and Bhattacharya, S. (2007). Synthesis, Structure and Electrochemical Properties of Some Thiosemicarbazone Complexes of Iridium. Struct. Chem. 18, 209–215. doi:10.1007/s11224-006-9090-5

Basu, S., Dutta, S., Drew, M. G. B., and Bhattacharya, S. (2006). Rhodium Assisted C-H Activation of N-(2ʹ-hydroxyphenyl)benzaldimines. Synthesis, Structure and Electrochemical Properties of a Group of Organorhodium Complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 691, 3581–3588. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.04.020

Bhattacharya, I., Dasgupta, M., Drew, M. G. B., and Bhattacharya, S. (2012). N-(Aryl)picolinamide Complexes of Rhodium : Synthesis, Structure and, Spectral and Electrochemical Properties. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 89, 205–216.

Boutry, O., Poveda, M. L., and Carmona, E. (1997). Formation of 1,2,3-Η3-Butadienyl Derivatives by Photochemical C-H Activation of Ir(I)-η4-1,3-diene Complexes Containing Tris(pyrazolyl) Borate Ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 528, 143–150. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(96)06613-2

Chen, W., Li, C. Y., Li, H. J., and Wu, Y. C. (2021). Intermolecular Amination of Ketoximes with Anthranils by Rh-Catalyzed C−H Bond Activation in Air. Asian J. Org. Chem. 10, 838–844. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202100043

Cheng, Q., Tu, H. F., Zheng, C., Qu, J. P., Helmchen, G., and You, S. L., Iridium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Substitution Reactions. Chem. Rev., 2019, 119, 1855–1969. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00506

Chi, Y., Chang, T. K., Ganesan, P., and Rajakannu, P. (2017). Emissive Bis-Tridentate Ir(III) Metal Complexes: Tactics, Photophysics and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 346, 91–100. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2016.11.016

Colombo, A., Dragonetti, C., Guerchais, V., Hierlinger, C., Colman, E. Z., and Roberto, D. (2020). A Trip in the Nonlinear Optical Properties of Iridium Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 414, 213293. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213293

Corbet, J. P., and Mignani, G. (2006). Selected Patented Cross-Coupling Reaction Technologies. Chem. Rev. 106, 2651–2710. doi:10.1021/cr0505268

Das, A., Basuli, F., Peng, S. M., and Bhattacharya, S. (2002). Oxidation of Rhodium(I) by Hydroxamic Acids. Synthesis, Structure, and Electrochemical Properties of Bis(hydroxamate) Complexes of Rhodium(III). Inorg. Chem. 41, 440–443. doi:10.1021/ic0106930

Dasgupta, M., Tadesse, H., Blake, A. J., and Bhattacharya, S. (2008). Interaction of N-(aryl)picolinamides with Iridium. N-H and C-H Bond Activations. J. Organomet. Chem. 693, 3281–3288. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2008.07.027

Davison, R. T., Kuker, E. L., and Dong, V. M., Teaching Aldehydes New Tricks Using Rhodium- and Cobalt-Hydride Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res., 2021, 54, 1236–1250. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00771

Dongbang, S., Confair, D. N., and Ellman, J. A., Rhodium-Catalyzed C–H Alkenylation/Electrocyclization Cascade Provides Dihydropyridines that Serve as Versatile Intermediates to Diverse Nitrogen Heterocycles. Acc. Chem. Res., 2021, 54. 1766–1778. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00027

Dickmu, G. C., and Smoliakova, I. P. (2020). Cyclopalladated Complexes Containing an (sp3)C–Pd Bond. Coord. Chem. Rev. 409, 213203. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213203

Donabauer, K., and Konig, B. (2021). Strategies for the Photocatalytic Generation of Carbanion Equivalents for Reductant-free C–C Bond Formations. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 242–252. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00620

Dutta, S., Basuli, F., Peng, S. M., Lee, G. H., and Bhattacharya, S. (2002). Synthesis, Structure and Redox Properties of Some Thiosemicarbazone Complexes of Rhodium. New J. Chem. 26, 1607–1612. doi:10.1039/B205338C

Dutta, S., Peng, S. M., and Bhattacharya, S. (2000). Ligand Control on Molecular Oxygen Activation by Rhodium Quinone Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 39, 2231–2234. doi:10.1021/ic990999v

Dutta, S., Peng, S. M., and Bhattacharya, S. (2000). Synthesis, Structure and Redox Properties of Some 2-(arylazo)phenolate Complexes of Rhodium(III). J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans., 4623–4627. doi:10.1039/b005902l

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., et al. (2009). Gaussian 09, Revision E.01. Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc..

Gardiner, M. S. W., Fu, R., Fortman, G. C., Nielsen, R. J., Gunnoe, T. B., and Goddard, W. A. (2015). Arene C–H Activation Using Rh(I) Catalysts Supported by Bidentate Nitrogen Chelates. Cat. Sci. Tech. 5, 96–100. doi:10.1039/C4CY00972J

Gu, Q., Jia, Q., Long, J., and Gao, Z. (2019). Heterogeneous Photocatalyzed C−C Cross-Coupling Reactions under Visible-Light and Near-Infrared Light Irradiation. ChemCatChem. 11, 669–683. doi:10.1002/cctc.201801616

GuhaRoy, C., Butcher, R. J., and Bhattacharya, S. (2008). Rhodium Complexes of 1,3-diaryltriazenes: Usual Coordination, N-H Bond Activation and, N-N and C-N Bond Cleavage. J. Organomet. Chem. 693, 3923–3931. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2008.10.006

GuhaRoy, C., Drew, M. G. B., and Bhattacharya, S. (2009). Tris-(1,3-diaryltriazenide) Complexes of Rhodium - Synthesis, Structure and, Spectral and Electrochemical Properties. J. Chem. Sci. 121, 257–266. doi:10.1007/s12039-009-0028-5

Hung, M. U., Press, L. P., Bhuvanesh, N., and Ozerov, O. V. (2021). Examination of a Series of Ir and Rh PXL Pincer Complexes as (Pre)catalysts for Aromatic C–H Borylation. Organometallics 40, 1004–1013. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00081

Kumar, A., Bhatti, T. M., and Goldman, A. S., Dehydrogenation of Alkanes and Aliphatic Groups by Pincer-Ligated Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev., 2017, 117, 12357–12384. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00247

Liu, J., Li, Y., Jiang, J., Liu, Y., and Ke, Z. (2021). Mechanism of Ir-Mediated Selective Pyridine O-C–H Activation: The Role of Lewis Acidic Boryl Group. ACS Catal. 11, 6186–6192. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c00310

Lou, J., Han, W., Liu, Z., and Xiao, J. (2021). Rhodium-catalyzed Enone Carbonyl Directed C–H Activation for the Synthesis of Indanones Containing All-Carbon Quaternary Centers. Org. Chem. Front. 8, 1447–1453. doi:10.1039/D1QO00056J

Majumder, P., Baksi, S., Halder, S., Tadesse, H., Blake, A. J., Drew, M. G. B., et al. (2011). Formation of Organorhodium Complexes via C-H Bond Activation of 1,3-di(phenylazo)benzene. Dalton Trans. 40, 5423–5425. doi:10.1039/c1dt10247h

Mao, H. T., Li, G. F., Shan, G. G., Wang, X. L., and Su, Z. M. (2020). Recent Progress in Phosphorescent Ir(III) Complexes for Nondoped Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 413, 213283. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213283

Monti, F., Baschieri, A., Sambri, L., and Armaroli, N., Excited-State Engineering in Heteroleptic Ionic Iridium(III) Complexes. Acc. Chem. Res., 2021, 54, 1492–1505. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00825

Lutz, M. D. R., and Morandi, B., Metal-Catalyzed Carbon–Carbon Bond Cleavage of Unstrained Alcohols. Chem. Rev., 2021, 121, 300–326. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00154

Osborn, J. A., and Wilkinson, G. (1967). Tris(triphenylphosphine)Halorhodium(I). Inorg. Synth. 10, 67. doi:10.1002/9780470132418.ch12

Paul, P., and Bhattacharya, S. (2012). Iridium Mediated N-H and C-H Bond Activation of N-(aryl)pyrrole-2-aldimines. Synthesis, Structure and, Spectral and Electrochemical Properties. J. Organomet. Chem. 713, 72–79. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2012.04.023

Paul, P., Richmond, M. G., and Bhattacharya, S. (2014). Iridium-mediated N-H and Methyl C-H Bond Activations in N-(2ʹ,6ʹ-dimethylphenyl)pyrrole-2-aldimine. Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Applications. J. Organomet. Chem. 751, 760–768. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2013.07.066

Press, L. P., Kosanovich, A. J., McCulloch, B. J., and Ozerov, O. V. (2016). High-Turnover Aromatic C–H Borylation Catalyzed by POCOP-type Pincer Complexes of Iridium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9487–9497. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b03656

Rej, S., Das, A., and Chatani, N. (2021). Strategic Evolution in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Directed C–H Bond Activation and Future Directions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 431, 213683. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213683

Sebastian, L. G., and Morales, D. M. (2019). Cross-coupling Reactions Catalysed by Palladium Pincer Complexes. A Review of Recent Advances. J. Organomet. Chem. 893, 39–51. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2019.04.021

Sengupta, P., and Bhattacharya, S. (2013). Rhodium Complexes of 3,5-Di-Tert-Butylcatechol : Synthesis, Structure and, Spectral and Electrochemical Properties. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 90, 169–179.

Seth, D. K., and Bhattacharya, S. (2011). Reactivity of the Sulfur center in Rhodium-Bound Benzaldehyde Thiosemicarbazones towards Molecular Oxygen. A Theoretical Investigation. J. Organomet. Chem. 696, 3779–3784. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2011.08.036

Shaikh, S., Wang, Y., Rehman, F., Jiang, H., and Wang, X. (2020). Phosphorescent Ir(III) Complexes as Cellular Staining Agents for Biomedical Molecular Imaging. Coord. Chem. Rev. 416, 213344. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213344

Sheldrick, G. M. (1997). SHELXS-97 and SHELXL-97, Fortran Programs for crystal Structure Solution and Refinement. Gottingen, Germany: University of Gottingen.

Slack, E. D., and Colacot, T. J. (2021). Understanding the Activation of Air-Stable Ir(COD)(Phen)Cl Precatalyst for C–H Borylation of Aromatics and Heteroaromatics. Org. Lett. 23, 1561–1565. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c04210

Tang, C. Y., Smith, W., Vidovic, D., Thompson, A. L., Chaplin, A. B., and Aldridge, S. (2009). Sterically Encumbered Iridium Bis(N-Heterocyclic Carbene) Systems: Multiple C−H Activation Processes and Isomeric Normal/Abnormal Carbene Complexes. Organometallics 28, 3059–3066. doi:10.1021/om9000082

Vuuren, E. V., Malan, F. P., and Landman, M. (2021). Multidentate NHC Complexes of Group IX Metals Featuring Carbon-Based Tethers: Synthesis and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 430, 213731. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213731

Wang, C., Chen, F., Qian, P., and Cheng, J. (2021). Recent Advances in the Rh-Catalyzed cascade Arene C–H Bond Activation/annulation toward Diverse Heterocyclic Compounds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 19, 1705–1721. doi:10.1039/D0OB02377A

Wiedemann, S. H., Lewis, J. C., Ellman, J. A., and Bergman, R. G. (2006). Experimental and Computational Studies on the Mechanism of N-Heterocycle C−H Activation by Rh(I). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 2452–2462. doi:10.1021/ja0576684

Woźniak, Ł., Tan, J. F., Nguyen, Q. H., Vigné, A. M., Smal, V., Cao, Y. X., et al. (2020). Catalytic Enantioselective Functionalizations of C–H Bonds by Chiral Iridium Complexes. Chem. Rev. 120, 10516–10543. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00559

Yoshino, T., and Matsunaga, S. (2021). Chiral Carboxylic Acid Assisted Enantioselective C–H Activation with Achiral CpxMIII (M = Co, Rh, Ir) Catalysts. ACS Catal. 11, 6455–6466. doi:10.1021/acscatal.1c01351

Yu, H., Zhao, H., Xu, X., Zhang, X., Yu, Z., Li, L., et al. (2021). Rhodium(I)-Catalyzed C2-Selective Decarbonylative C−H Alkylation of Indoles with Alkyl Carboxylic Acids and Anhydrides. Asian J. Org. Chem. 10, 879–885. doi:10.1002/ajoc.202000712

Keywords: N-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)furan/thiophene-2-aldimine, C-H and O-H bond activations, organorhodium and organoiridium complexes, formation mechanisms, catalytic C-C cross-coupling reaction

Citation: Sengupta P, Das R, Dhibar P, Paul P and Bhattacharya S (2021) Rhodium and Iridium Mediated C-H and O-H Bond Activation of Two Schiff Base Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Properties of the Organometallic Complexes. Front. Chem. 9:696460. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.696460

Received: 16 April 2021; Accepted: 06 July 2021;

Published: 09 August 2021.

Edited by:

Soumyajit Roy, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, IndiaReviewed by:

Ebbe Nordlander, Lund University, SwedenMithun Kumar Ghosh, Pandit S. N. Shukla University, India

Copyright © 2021 Sengupta, Das, Dhibar, Paul and Bhattacharya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Samaresh Bhattacharya, c2FtYXJlc2hfYkB5YWhvby5jb20=

Poulami Sengupta1,2

Poulami Sengupta1,2 Samaresh Bhattacharya

Samaresh Bhattacharya