- 1College of Electromechanical Engineering, Shandong Engineering Laboratory for Preparation and Application of High-Performance Carbon-Materials, Qingdao University of Science & Technology, Qingdao, China

- 2Military Representative Office of Army, Qingdao, China

Gas hydrates have promising application prospects in the fields of future energy sources, natural gas storage and transportation, CO2 capture and sequestration, gas separation, and cold energy. However, the application of hydrate technologies is being restricted due to the slow formation rate of gas hydrates. Kinetic promoters have been receiving increased attention, given that they can improve the hydrate formation rate with very small doses and do not affect gas storage capacity. However, most kinetic promoters are non-renewable, petrochemical-derived, non-degradable materials, inevitably leading to resource waste and environmental pollution. Biopromoters, derived from biomass, are renewable, biodegradable, environmentally friendly, non-toxic (or low toxic), and economically feasible. This mini review summarizes the current status of already discovered biopromoters, including lignosulfonate, amino acid, biosurfactant, and biological porous structures, which have the potential to replace petrochemical-derived promoters in hydrate technologies. Finally, future research directions are given for the development of biopromoters.

Introduction

Gas hydrates are a form of non-stoichiometric crystalline, in which water molecules form the host lattice via hydrogen bonds and guest gases are trapped in the host lattice via intermolecular forces (He et al., 2019). Gas hydrates have been getting increased attention due to their promising number of applications, such as in future energy sources, natural gas storage and transportation, CO2 capture and sequestration, gas separation, and cold energy (Sun and Kang, 2016; Veluswamy et al., 2018; He et al., 2019). However, the application of hydrate technology is restricted by the slow formation rate of hydrates.

Kinetic promoters can improve the hydrate formation rate with very small doses and do not affect gas storage capacity (He et al., 2019). Researchers have used various kinetic promoters for gas hydrate formation, such as synthetic surfactants, activated carbon, porous silica, metal nanoparticles, graphene, carbon nanotubes, glass beads, sand grains, and dry water (Siangsai et al., 2015; Chong et al., 2016; He et al., 2019). However, most of the promoters above are non-renewable, petrochemical-derived, non-degradable materials, which will inevitably lead to resource waste and environmental pollution. Synthetic surfactants show an obvious superiority compared with other promoters, particularly given the material cost, especially for sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (He et al., 2019). However, synthetic surfactants, such as SDS, sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS), and sodium hexadecyl sulfate (SHS) can cause chronic toxicity in living organisms (Lewis, 1991), which restricts the application of hydrate technologies. For example, Ocean CO2 sequestration in the form of CO2 hydrates is being considered as an effective way to decrease the CO2 content in the atmosphere (Sun and Kang, 2016). If CO2 hydrates sequestrated in ocean sediments are formed using synthetic surfactants with chronic toxicity, the ocean ecological environment will suffer a dramatically adverse impact once those promoters are leaked into the ocean.

Biopromoters derived from biomass are renewable, biodegradable, environmentally friendly, nontoxic (or low toxic), and economically feasible. Biopromoters could be considered as promising promoters instead of traditional promoters for the application of hydrate technology. With the purpose of achieving a comprehensive evaluation on the discovered biopromoters and creating effective guidance for future research, this mini review summarizes the promoting effects and promoting mechanisms of discovered biopromoters which have the potential to replace petrochemical-derived promoters in gas hydrate technologies.

Biopromoter

In the last 10 years, scholars have explored and discovered some biopromoters that can be used for gas hydrate formation, which can be divided into four categories: (1) lignosulfonates (LSs), (2) amino acids, (3) biosurfactants, and (4) biological porous structures. These four categories of biopromoters will be separately discussed in the following sections. The promoting effects of different biopromoters under corresponding experimental conditions are listed in Table S1.

LS

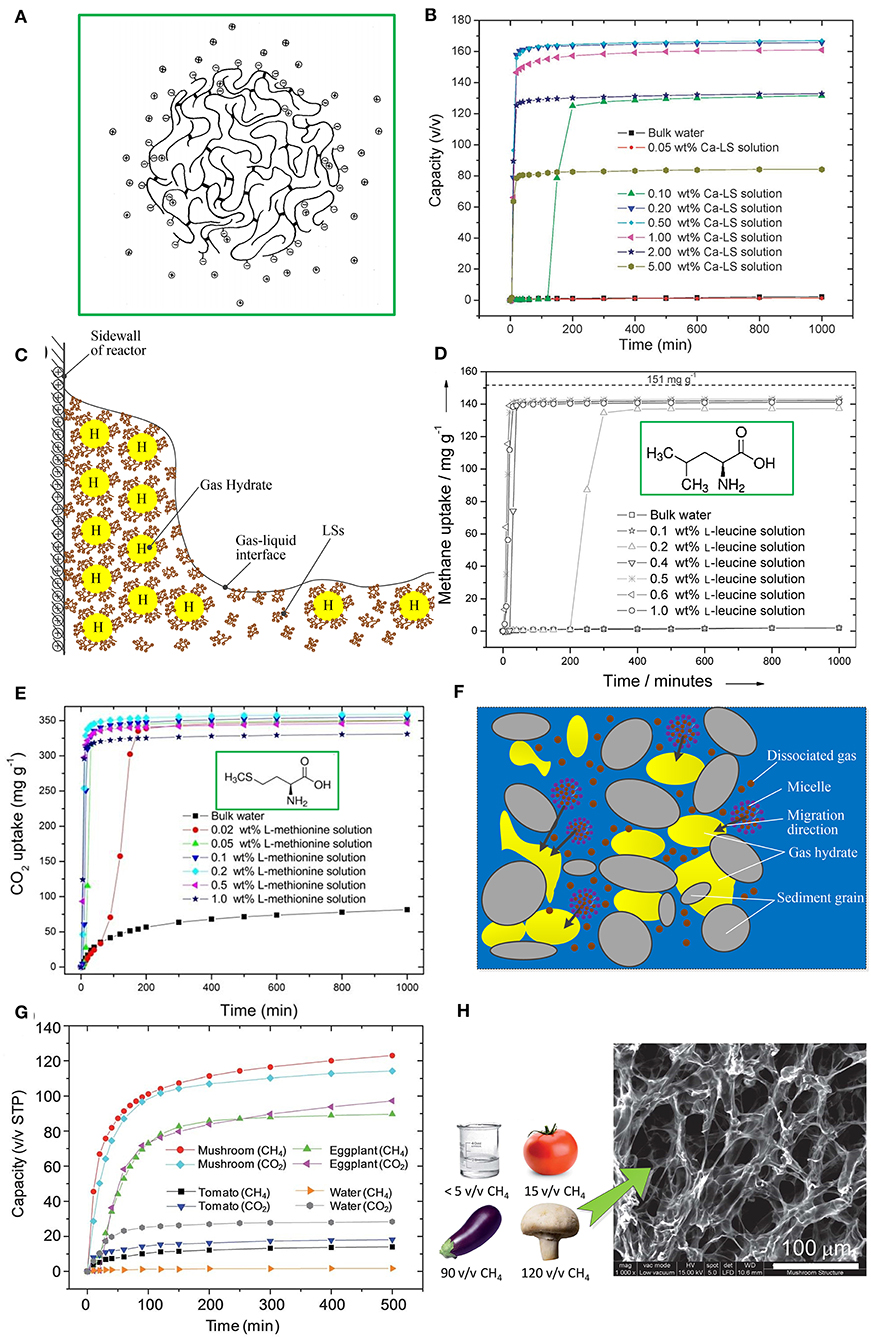

LSs, as byproducts of the sulfite pulping process in the pulp and paper industry, are obtained by cutting α-O-4 ether bonds in nature lignin and sulphonating α- and/or γ-positions of the side chains of C9 units (Myrvold, 2008). The basic structure of LSs is a phenylpropane derivative, including a C3-C6 hydrophobic skeleton. LSs also contain hydrophilic groups, such as the sulfonic acid group, carboxyl group, and phenolic hydroxyl group. Although the microstructure of LSs in aqueous solutions is still inconclusive, it has been confirmed that LS macromolecules can generate cross-links and form spherical, disc-like, or sheet-like microgels with sulfonic acid groups located on its outer surface (Myrvold, 2008). Figure 1A shows a spherical microgel model of LS macromolecules (Rezanowich and Goring, 1960). The cross-link of LS macromolecules may offer a hydrophobic space for dissolving more guest gases, and sulfonic acid groups can associate cross-linked LS molecules with water molecules through a hydrogen bond (Wang et al., 2017).

Figure 1. (A) Spherical microgel model of an LS macromolecule. Reproduced from Rezanowich and Goring (1960) with permission from Elsevier. (B) CH4 formation kinetics in a Ca-LS aqueous solution at 273.2 K and 9.5 MPa. Reproduced from Wang et al. (2012) with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. (C) Schematic diagram of the promoting mechanism of LSs. (D) CH4 formation kinetics in a L-leucine aqueous solution at 273 K and 9.5 MPa. Reproduced from Liu et al. (2015) with permission from John Wiley and Sons. (E) CO2 formation kinetics in L-methionine aqueous solution at 273.2 K and 3.3 MPa. Reproduced from Cai et al. (2017) with the permission from the John Wiley and Sons. (F) Schematic diagram of the promoting mechanism of biosurfactant in seabed sands/clay; (G) CH4 and CO2 formation kinetics for tomato, eggplant, and mushroom samples. Reproduced from Wang et al. (2013) with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. (H) SEM image of a mushroom sample showing a fine porous structure. Reproduced from Wang et al. (2013) with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Formation kinetics of gas hydrates in LS aqueous solutions were first reported by Wang et al. (2012). Figure 1B shows the formation kinetics of a CH4 hydrate in a calcium lignosulfonate (Ca-LS) aqueous solution with different concentrations (Wang et al., 2012). It can be seen that LS significantly improved the formation rate and gas storage capacity of the CH4 hydrate. The storage capacity of the CH4 hydrate reached 167 v/v (storage capacity was defined as the volume of guest gas stored in per unit volume of hydrate) within 1000 min in 0.5 wt% Ca-LS aqueous solution, t90 (the time to achieve 90% of the corresponding gas storage capacity) was only about 20 min, and the induction time reduced to <6 min. Among synthetic surfactants, the promoting effect of SDS is recognized as the best. However, a large amount of foam is generated during the dissociation process of the hydrate using SDS as a promoter, which not only influences the release of methane gas from the methane hydrate but also causes the loss of the SDS promoter in cyclic utilization (He et al., 2019). By contrast, the generated foam had a significant reduction during hydrate dissociation when the hydrate formed in a sodium lignosulfonate (Na-LS) aqueous solution, because the dissolution of Na-LS only generated a small amount foam (Mofrad et al., 2016). Besides, under certain concentrations, the CH4 storage capacity using Na-LS as a promoter is better than that of SDS, although the formation rate of Na-LS is still lower than that of SDS (Mofrad et al., 2016). For a CO2/CH4 gas mixture system, gas storage capacity under a Na-LS promoter was about 1.7 times higher than that in pure water, but the hydrate formation still had a longer induction time, ranging from 46.7 min to 400 min (Yi et al., 2019).

Most scholars think the promoting mechanism of LSs comes from their being capillarity-driven and their mass transfer. As observed by Wang et al. (2012), a CH4 hydrate grew upward along the inner wall of the reactor in an LS aqueous solution, which was a representative phenomenon from something that is capillarity-driven. As shown in Figure 1C, LS molecules can adsorb on the surface of forming hydrate particles under the action of hydrogen bonds between partial hydrophilic groups and hydrate molecules. Meanwhile, partial hydrophilic groups, such as sulfonic acid group and carboxyl group, are exposed to the outside surface of forming hydrate particles, which leads to mutual repulsion among forming hydrate particles under electrostatic action (Dicharry et al., 2016). And the hydrate particles become more wettable for water molecules due to hydrophilic groups. A water-wettable porous hydrate structure is formed, which drives the capillary action for sucking the water molecules to the reaction site of hydrate. CH4 hydrate formation has stronger capillarity-driven action than a CO2 hydrate formation (Daniel-David et al., 2015). On the other hand, the LS molecules arrange on the gas-liquid interface and reduce interfacial tension, which enhances the diffusion of gas molecules from a gas phase to a liquid phase. As a result, the supersaturation of gas molecules in a liquid phase promotes hydrate nucleation. However, it is necessary to use higher concentrations of LS to reduce interfacial tensions, compared with single molecule surfactants (Gupta and Washburn, 2014).

Amino Acids

Amino acids are the basic constituent units of biologically macromolecular proteins and are an indispensable nutrient in the biological body. There are 20 species of amino acids obtained after proteolysis, around which researches have been focusing on both promoting hydrate formation and inhibiting hydrate formation in the last 10 years (Bavoh et al., 2019). The side chain of amino acids, ranging from a nonpolar alkyl chain to a charged or uncharged polar chain, plays a key role in their physico-chemical properties (Madeira et al., 2014).

Amino acids used for promoting gas hydrate formation were first reported by Liu et al. (2015). Leucine showed the best promoting effect for a CH4 hydrate among the surveyed Amino acids. As shown in Figure 1D, CH4 storage capacity reached 144 mg per g water (equivalent to a storage capacity of 161 v/v according to conversion Equation (1) in the Supplementary Material) and t90 was about 20 min. While for the CO2 system, L-methionine showed the best promoting effect, as shown in Figure 1E, where CO2 storage capacity reached 356 mg per g water (equivalent to a storage capacity of 144 v/v) and t90 was about 15 min (Cai et al., 2017). Summarizing previous studies, it can be found that for different guest gases the same amino acid will exert different effects. For example, L-histidine presented a promoting effect for a CH4 hydrate (Bhattacharjee et al., 2016), while presenting an inhibiting effect for a CO2 hydrate (Roosta et al., 2016). Leucine was reported to exert a poor promoting effect for an ethane hydrate and THF hydrate (Naeiji et al., 2014), but a favorable promoting effect for a CH4 hydrate (Liu et al., 2015). For a CH4 hydrate, the amino acids with a kinetic promoting effect are listed in order at concentration of 0.5 wt% as follows: L-leucine > L-isoleucine > D-leucine > L-methionine > L-phenylalanine > L-tryptophan > L-valine > L-arginine > L-glutamic acid > L-histidine > L-threonine (Liu et al., 2015). For CO2 hydrate, the amino acids with a kinetic promoting effect are listed in order as follows: L-methionine > L-norleucine > L-tryptophan > L-norvaline > n-hexylamine at concentration of 0.2 wt% reported by Cai et al. (2017) and L-methionine > L-cysteine > L-valine > L-threonine > L-phenylalanine at concentration of 0.5 wt%, reported by Prasad and Kiran (2018).

Most authors think the promoting effect comes from the surface activity of amino acids generated by the amine group, carboxylic group, and side chain. Given that the amine group and carboxylic group have hydrophilic properties, the amino acids with an aromatic sided chain and hydrophobic properties generally present a promoting effect (Bavoh et al., 2019). The formation of a hydrate film on the gas-liquid interface at the initial formation stage reduces the diffusion of gas molecules from a gas phase to a liquid phase. The surface activity of amino acids can restrain the formation of this initial hydrate film, which enhances gas mass transfer. The forming hydrates in an amino acid aqueous solution are very flexible and expandable, which indicates that being capillarity-driven also plays a role in the growth phase of hydrates (Veluswamy et al., 2016). In addition, amino acids can chemically adsorb CO2 molecules in a CO2 system via a zwitterionic mechanism, which is speculated to influence CO2 hydrate formation (Zhang et al., 2018). The CO2 molecule firstly reacts with the amine group, producing a zwitterion, and then the zwitterion reacts with the amine group, producing amino acid salt. The CO2 adsorption rate is related to the promoting effect of CO2 hydrate formation (Bavoh et al., 2019).

Biosurfactant

Biosurfactants are secreted metabolites with surface activity during the metabolism of microorganisms under certain conditions. Microorganisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus subtilis were found from exploiting natural gas hydrate samples in the Gulf of Mexico (Lanoil et al., 2001). These two microorganisms can produce biosurfactants, i.e., rhamnolipid and surfactin, respectively, which has attracted the attention of hydrate researchers. Rhamnolipid is composed of 1-2 rhamnose rings (hydrophilic group) and saturated or unsaturated hydroxy fatty acids (hydrophobic group). Surfactin is a combination of a peptide ring containing 7 amino acid residues and β-hydroxy fatty acid containing 13-16 carbons by lactone bond (Arora et al., 2014).

Surfactin and rhamnolipid were first proven to have a promoting effect for natural gas hydrate formation in seawater-saturated sand/clay by Rogers et al. (2003), in which the hydrate formation rate increased by 96–288% and induction time decreased by 20–71%. Rhamnolipid was used as a co-promoter in a C-type silica-gel bed for promoting CH4 hydrate formation (Arora et al., 2016). As a result, the hydrate formation rate increased by 42.97% and induction time decreased by 22.63%, compared with a C-type silica-gel bed with saturated pure water. Biosurfactants also exhibited comparability with SDS. According to the research of Jadav et al. (2017), for 200 ppm surfactin, rhamnolipid, and SDS aqueous solution, the conversion rate from CH4 to hydrate was 42.7, 47.3, and 33.3%, and induction time was about 0.21, 0.23, and 1.13 h, respectively.

Biosurfactants have a lower critical micellar concentration (CMC) compared with synthetic surfactants (Arora et al., 2014). The CMC of the rhamnolipid seawater solution was about 13 ppm, which was easily achieved through minimal microbial activity in seabed sands/clay (Rogers et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 1F, the promoting effect of biosurfactants in seabed sands/clay was thought to be due to a micelle migration process, where micelles, dissolving hydrocarbon gas, migrated through seabed sand/clay with saturated seawater to the hydrate formation zone. On the other hand, both surfactin and rhamnolipid belong to anionic surfactants. Surfactin and rhamnolipid molecules can adsorb on the surface of hydrate particles to form a loose hydrate structure and enhance capillarity-driven action (Jadav et al., 2017). Rhamnolipid presents a better promoting effect compared with surfactin. This may be due to the difference in molecular structure. The anionic groups in surfactin and rhamnolipid molecules are nitrogen bonding and carboxylate, respectively, while rhamnolipid has more tails than surfactin, which helps to enhance the adsorption of rhamnolipid molecules on the surface of hydrate particles (Jadav et al., 2017). Rhamnolipid with a concentration of not <0.5 wt% was proved to form well-dispersed CH4 hydrate morphology in an oil-water system (Hou et al., 2018), which has an anti-agglomeration function. Besides, surfactin and rhamnolipid can also enhance mass transfer between the gas phase and liquid phase (Arora et al., 2014).

Biological Porous Structure

Various biological structures have evolved for tackling gas transport and enhancing mass transfer in nature, such as alveoli, gills, stoma of leaves, etc., which encourages scholars to find some natural biological structures for promoting gas hydrate formation. Wang et al. (2013) first studied the promoting effect of the biological porous structure from mushroom, eggplant, and tomato on CH4 and CO2 hydrate formation, as shown in Figure 1G. CH4 storage capacity could reach 120 and 90 v/v within 500 min in mushroom and eggplant samples, respectively. CO2 storage capacity was similar to CH4 storage capacity. The better promoting effect benefits from the large surface-to-volume ratio and fine porous structure, as shown in Figure 1H, which improves gas mass transfer and helps to form loose gas hydrates with a biological porous structure as a framework. However, when mushroom and eggplant samples were used for the second hydrate cycle, there was a significant drop in gas storage capacity and formation rate. This was because the porous structure was destroyed after a hydrate-decomposition process.

Given that natural biological porous materials lack the structural stability for use in the recycling application of promoters in hydrate technologies, artificially biological structures may provide a better recycling stability. Nambiar et al. (2015) applied a porous cellulose foam fixed-bed for a hydrate-based CO2 separation from a CO2/H2/C3H8 gas mixture. They found that, compared with the saturation level of 100%, a cellulose foam fixed-bed under a saturation level of 50% presented a better promoting effect, because there was more available gas for gas mass transfer and migration of water molecules in the porous structure during hydrate formation. Unfortunately, there was no report on the recycling performance of a cellulose foam fixed-bed in the paper.

Conclusion and Prospect

This mini review summarizes the current status of already discovered biopromoters, including LSs, amino acids, biosurfactants, and biological porous structures. In general, the order of promoting effect from strong to weak is as follows: LSs > amino acids > biological porous structures > biosurfactants. The surface activity and capillarity-driven action of LSs, amino acids, and biosurfactants play key roles in promoting gas hydrate formation. A biological porous structure improves gas mass transfer and helps to form loose gas hydrates. The following research direction should earn more attention in the future:

(1) There is no consensus on the promoting mechanisms of biopromoters. Further study on promoting mechanisms is necessary, which would help to provide guidance for the selection of biologic materials as biopromoters.

(2) At present, biopromoters have not shown enough advantages to replace petrochemical-derived promoters in gas hydrate technologies, particularly given the promoting effect. The gas storage capacity under biopromoters can be better than that under petrochemical-derived promoters, but only at certain concentrations. However, there is still a gap between the formation rates of gas hydrate under biopromoters and petrochemical-derived promoters. Nature is a treasury of biologic materials. It is necessary to seek new promising natural biopromoters to achieve a higher formation rate.

(3) Artificially preparing biopromoters through chemical modification or by constructing a porous structure could be a promising approach for improving the promoting effect and recycling performance of promoters in hydrate technologies.

Author Contributions

FW conceived the structure of the manuscript. F-LC collected materials and data. Y-TZ wrote the manuscript. S-JY wrote the Supplementary Material. FW revised and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21978142, 21706269), the Youth Innovation Talent Development Project for Universities of Shandong Province, and the Taishan Scholar Project of Shandong Province (ts20190937).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2020.00514/full#supplementary-material

References

Arora, A., Cameotra, S. S., Kumar, R., Balomajumder, C., Singh, A. K., Santhakumari, B., et al. (2016). Biosurfactant as a promoter of methane hydrate formation: thermodynamic and kinetic studies. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep20893

Arora, A., Cameotra, S. S., Kumar, R., Kumar, P., and Balomajumder, C. (2014). Effects of biosurfactants on gas hydrates. J. Petrol. Environ. Biotechnol. 5:170. doi: 10.4172/2157-7463.1000170

Bavoh, C. B., Lal, B., Osei, H., Sabil, K. M., and Mukhtar, H. (2019). A review on the role of amino acids in gas hydrate inhibition, CO2 capture and sequestration, and natural gas storage. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 64, 52–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2019.01.020

Bhattacharjee, G., Choudhary, N., Kumar, A., Chakrabarty, S., Kumar, R., et al. (2016). Effect of the amino acid l-histidine on methane hydrate growth kinetics. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 35, 1453–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2016.05.052

Cai, Y., Chen, Y., Li, Q., Huang, H., Wang, S., Wang, W., et al. (2017). CO2 Hydrate formation promoted by a natural amino acid l-methionine for possible application to CO2 capture and storage. Energy Technol. 5, 1195–1199. doi: 10.1002/ente.201600731

Chong, Z. R., Yang, M., Khoo, B. C., and Linga, P. (2016). Size effect of porous media on methane hydrate formation and dissociation in an excess gas environment. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55, 7981–7991. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b03908

Daniel-David, D., Guerton, F., Dicharry, C., Torré, J. P., and Broseta, D. (2015). Hydrate growth at the interface between water and pure or mixed CO2/CH4 gases: Influence of pressure, temperature, gas composition and water-soluble surfactants. Chem. Eng. Sci. 132, 118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2015.04.015

Dicharry, C., Diaz, J., Torré, J. P., and Ricaurte, M. (2016). Influence of the carbon chain length of a sulfate-based surfactant on the formation of CO2, CH4 and CO2-CH4 gas hydrates. Chem. Eng. Sci. 152, 736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2016.06.034

Gupta, C., and Washburn, N. R. (2014). Polymer-grafted lignin surfactants prepared via reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer polymerization. Langmuir 30, 9303–9312. doi: 10.1021/la501696y

He, Y., Sun, M. T., Chen, C., Zhang, G. B., Chao, K., Lin, Y., et al. (2019). Surfactant-based promotion to gas hydrate formation for energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 21634–21661. doi: 10.1039/C9TA07071K

Hou, G., Liang, D., and Li, X. (2018). Experimental study on hydrate anti-agglomeration in the presence of rhamnolipid. RSC Adv. 8, 39511–39519. doi: 10.1039/c8ra07215a

Jadav, S., Sakthipriya, N., Doble, M., and Sangwaia, J. S. (2017). Effect of biosurfactants produced by Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa on the formation kinetics of methane hydrates. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 43, 156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2017.03.032

Lanoil, B. D., Sassen, R., La Duc, M. T., Sweet, S. T., and Nealson, K. H. (2001). Bacteria and archaea physically associated with gulf of Mexico gas hydrates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 5143–5153. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.5143-5153.2001

Lewis, M. A. (1991). Chronic and sublethal toxicities of surfactants to aquatic animals: a review and risk assessment. Water Res. 25, 101–113. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(91)90105-Y

Liu, Y., Chen, B., Chen, Y., Zhang, S., Guo, W., Cai, Y., et al. (2015). Methane storage in a hydrated form as promoted by leucines for possible application to natural gas transportation and storage. Energy Technol. 3, 815–819. doi: 10.1002/ente.201500048

Madeira, P. P., Bessa, A., Álvares-Ribeiro, L., Aires-Barros, M. R., Rodrigues, A. E., Uversky, V. N., et al. (2014). Amino acid/water interactions study: a new amino acid scale. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 32, 959–968. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2013.800994

Mofrad, H. R., Ganji, H., Nazari, K., Kameli, M., Rezaie Rod, A., Kakavand, K., et al. (2016). Rapid formation of dry natural gas hydrate with high capacity and low decomposition rate using a new effective promoter. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 147, 756–759. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2016.10.002

Myrvold, B. O. (2008). A new model for the structure of lignosulphonates: Part 1. behaviour in dilute solutions. Ind. Crop. Prod. 27, 214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2007.07.010

Naeiji, P., Arjomandi, A., and Varaminian, F. (2014). Amino acids as kinetic inhibitors for tetrahydrofuran hydrate formation: experimental study and kinetic modeling. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 21, 64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2014.07.029

Nambiar, A., Babu, P., and Linga, P. (2015). CO2 capture using the clathrate hydrate process employing cellulose foam as a porous media. Can. J. Chem. 93, 808–814. doi: 10.1139/cjc-2014-0547

Prasad, P. S. R., and Kiran, B. S. (2018). Are the amino acids thermodynamic inhibitors or kinetic promoters for carbon dioxide hydrates? J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 52, 461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2018.02.001

Rezanowich, A., and Goring, D. A. I. (1960). Polyelectrolyte expansion of a lignin sulfonate microgel. J. Colloid Sci. 15, 452–471. doi: 10.1016/0095-8522(60)90049-0

Rogers, R. E., Kothapalli, C., Lee, M. S., and Woolsey, J. L. (2003). Catalysis of Gas Hydrates by Biosurfactants in Seawater-Saturated Sand/Clay. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 81, 973–980. doi: 10.1002/cjce.5450810508

Roosta, H., Dashti, A., Mazloumi, S. H., and Varaminian, F. (2016). Inhibition properties of new amino acids for prevention of hydrate formation in carbon dioxide-water system: Experimental and modeling investigations. J. Mol. Liq. 215, 656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2016.01.039

Siangsai, A., Rangsunvigit, P., Kitiyanan, B., Kulprathipanja, S., and Linga, P. (2015). Investigation on the roles of activated carbon particle sizes on methane hydrate formation and dissociation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 126, 383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2014.12.047

Sun, Q., and Kang, Y. T. (2016). Review on CO2 hydrate formation/dissociation and its cold energy application. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev., 62, 478–494. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.04.062

Veluswamy, H. P., Hong, Q. W., and Linga, P. (2016). Morphology study of methane hydrate formation and dissociation in the presence of amino acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 16, 5932–5945. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.6b00997

Veluswamy, H. P., Kumar, A., Seo, Y., Lee, J. D., and Linga, P. (2018). A review of solidified natural gas (SNG) technology for gas storage via clathrate hydrates. Appl. Energy 216, 262–285. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.02.059

Wang, F., Guo, G., Luo, S. J., and Guo, R. B. (2017). Preparation of –-coated nanopromoters for methane hydrate formation: effects of the existence pattern of – groups on the promotion efficiency. J. Mater. Chem. A. 5, 2640–2648. doi: 10.1039/C6TA08839B

Wang, W., Ma, C., Lin, P., Sun, L., and Cooper, A. I. (2013). Gas storage in renewable bioclathrates. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 105–107. doi: 10.1039/c2ee23565j

Wang, W. X., Huang, Z., Chen, H. R., Tan, Z., Chen, C., and Sun, L. (2012). Methane hydrates with a high capacity and a high formation rate promoted by biosurfactants. Chem. Commun. 48, 11638–11640. doi: 10.1039/C2CC35603A

Yi, J., Zhong, D. L., Yan, J., and Lu, Y. Y. (2019). Impacts of the surfactant sulfonated lignin on hydrate based CO2 capture from a CO2/CH4 gas mixture. Energy 171, 61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2019.01.007

Keywords: gas hydrate, biopromoter, kinetic promoter, biomass, mechanism

Citation: Zhang Y-T, Chen F-L, Yu S-J and Wang F (2020) Biopromoters for Gas Hydrate Formation: A Mini Review of Current Status. Front. Chem. 8:514. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00514

Received: 20 February 2020; Accepted: 18 May 2020;

Published: 08 July 2020.

Edited by:

Zhuhua Zhang, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, ChinaReviewed by:

Jincheng Lei, Rice University, United StatesSenbo Xiao, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

Copyright © 2020 Zhang, Chen, Yu and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fei Wang, ZWxsaW90X3dhbmdAcXVzdC5lZHUuY24=

Yong-Tao Zhang

Yong-Tao Zhang Fu-Lin Chen1

Fu-Lin Chen1 Fei Wang

Fei Wang