- 1State Key Laboratory of Urban Water Resource and Environment, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China

- 2Faculty of Science, Center for Clean Energy Technology, School of Mathematical and Physical Science, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3Harbin Institute of Technology, Academy of Fundamental and Interdisciplinary Sciences, Harbin, China

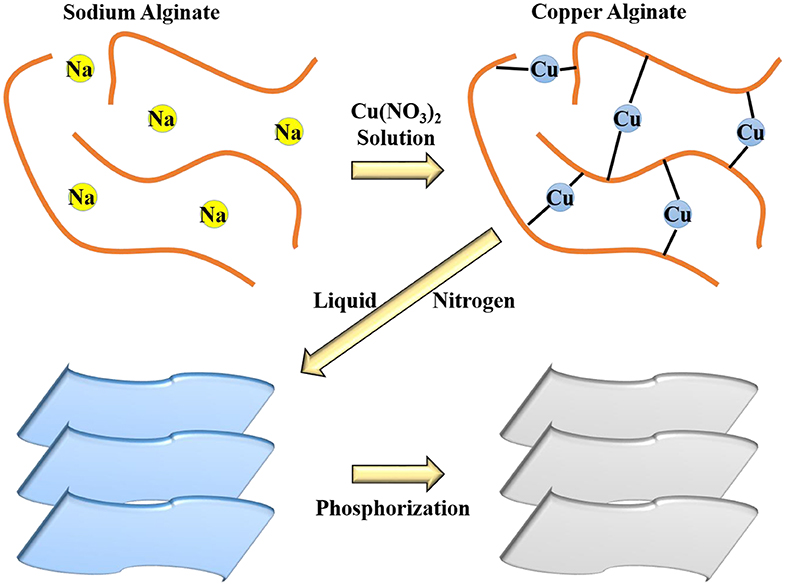

Biomass-derived approaches have been accepted as a practical way for the design of transitional metal phosphides confined by carbon matrix (TMPs@C) as energy storage materials. Herein, we successfully synthesize P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheets encapsulating Cu3P nanoparticles (Cu3P@P/N-C) by a feasible aqueous reaction followed by a phosphorization procedure using sodium alginate as the biomass carbon source. Cu-alginate hydrogel balls can be squeezed into two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets through a freeze–drying process. Then, Cu3P@P/N-C was obtained after the phosphorization procedure. This rationally designed structure not only improved the kinetics of ion/electron transportation but also buffered the volume expansion of Cu3P nanoparticles during the continuous charge and discharge processes. In addition, the 2D P/N co-doped carbon nanosheets can also serve as a conductive matrix, which can enhance the electronic conductivity of the whole electrode as well as provide rapid channels for electron/ion diffusion. Thus, when applied as anode materials for sodium-ion batteries, it exhibited remarkable cycling stability and rate performance. Prominently, Cu3P@P/N-C demonstrated an outstanding reversible capacity of 209.3 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1 after 1,000 cycles. Besides, it still maintained a superior specific capacity of 118.2 mAh g−1 after 2,000 cycles, even at a high current density of 5 A g−1.

Introduction

In recent years, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have been widely applied from portable electronic devices to electric vehicles (Zou et al., 2017, 2019; Qiu et al., 2019). However, the shortage of lithium sources limited the further development of LIBs (Wang et al., 2018a; Wu C. et al., 2018). Over the past few years, sodium-ion batteries (SIBs), owing to their low cost of production and earth-abundant sodium sources, show tremendous potential as a promising replacement of LIBs for large-scale energy storage applications (Kundu et al., 2015; Larcher and Tarascon, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016, 2018; Song et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2018, 2020). However, when compared with LIBs, SIBs are still an immature technology that is confronted with a lot of challenges, such as low specific energy, poor cycleability, and low power density (Wessells et al., 2011; Lotfabad et al., 2014; Li and Zhou, 2018). Anode, as the main component of SIBs, has a great influence on the overall electrochemical performance. In recent years, red phosphorus has been regarded as one of promising SIB anode materials owing to its comparatively low redox potential (~0.4 V vs. Na/Na+) and extremely high theoretical specific capacity (2,596 mAh g−1) (Kim et al., 2013; Qian et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2018; Wu Y. et al., 2018). However, the low electrical conductivity (~10−14 S cm−1) and the huge volume expansion (~490%) during the continuous Na+ insertion/extraction process make red phosphorus suffer from inferior cycling stability and rate performance (Sun et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018b). Fortunately, forming transition metal phosphides (TMPs) by combining red phosphorus with conductive transition metals has been proven to be an efficient way to enhance the electronic conductivity and reduce the volume change of phosphorus-based anode materials (Fullenwarth et al., 2014; Pramanik et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2016; Wang X. et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018).

Transitional metal phosphides (TMPs, M = Fe, Cu, Co, etc.) have drawn tremendous attention because of their high specific capacity and safe operating potential (Kim et al., 2013; Qian et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2018; Wu Y. et al., 2018). Particularly, copper phosphide-based anode materials for SIBs have a low reduction potential (0.015–0.4 V vs. Na+/Na) and comparatively high specific capacity (Fan et al., 2016; Kong et al., 2018). However, similar to other conversion-type SIB anode materials, the volume expansion during the charge/discharge process has not been entirely overcome, and its diffusion kinetics is comparatively weak (Ge et al., 2017; Miao et al., 2017; Wang J. et al., 2017).

Fortunately, several effective strategies revealed promising potential ability in boosting the sodium storage performance of TMP anode materials. For example, constructing nanostructured materials, such as nanospheres and nanoparticles, can not only improve the reaction kinetics by shortening the diffusion distance of Na ions within the solid state but also relieve the mechanical strain generated by the large volume change during the conversion reaction (Xu et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2018). In addition, combining TMPs with conductive carbon matrices can also buffer the huge volume expansion and enhance the electronic conductivity of the electrode, thus resulting in better sodium storage performance (Qian et al., 2014; Li et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). For instance, Cu3P/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite synthesized by Tong et al. showed superior cycling stability and good rate capability (Liu et al., 2016). The carbon-confined Cu3P nanoparticles prepared by Zhou et al. exhibited superior cycling stability with a high capacity of 159 mAh g−1 at 1.0 A g−1 over 100 cycles (Kong et al., 2018). Although much progress has been achieved by reducing the particle size of Cu3P as well as introducing conductive carbon, it still remains a major challenge to develop a scalable and inexpensive method for practical application.

Biomass-derived carbon, profiting from its economy, environmental benignity, and sustainability, has attracted increasing attention (Moreno et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2017). Among them, sodium alginate has high availability and biodegradability, is non-toxic, and of low price (Comaposada et al., 2015). In particular, sodium alginate can cross-link with di- or trivalent ions (Marcos et al., 2016), thus making it a proper carbon source to synthesize TMP anode materials combined with conductive carbon matrices.

Herein, we present the preparation of Cu3P nanoparticles encapsulated in P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheets (Cu3P@P/N-C) through a feasible aqueous reaction followed by a phosphorization procedure. Cu3P nanoparticles are well-dispersed and encapsulated in two-dimensional (2D) carbon nanosheets, which can not only buffer the large volume expansion but also prevent the agglomeration of Cu3P nanoparticles, thereby maintaining the integrity of the whole electrode. Furthermore, the 2D carbon nanosheet structure can shorten the Na+ diffusion path, provide more active sites of Na+, as well as enhance the electronic conductivity of the entire electrode. Benefiting from these advantages mentioned above, Cu3P@P/N-C exhibited a long cycle life and outstanding rate performance when applied as anode for SIBs. Cu3P@P/N-C anode materials demonstrated a long cycle life (209.3 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1 after 1,000 cycles) and excellent rate performance (118.2 mAh g−1 even at a high current density of 5 A g−1 after 2,000 cycles).

Experimental Section

Materials

All materials in the experiment were used without further purification. Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (ACS, 98.0–102.0%) was purchased from Aladdin. Sodium alginate (AR) was purchased from Aladdin. Red phosphorus (AR) was purchased from Kermel. Argon gases were supplied in cylinders by Qinghuaqiti with 99.999% purity.

Preparation of Cu-Alginate Gel

Sodium alginate (1.0 g) was dispersed in 50 ml distilled water to form an aqueous solution. Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (2.0 g) was also dispersed in 50 ml distilled water to form an aqueous solution. Then, the sodium alginate aqueous solution was dropped slowly by a disposable plastic dropper into Cu(NO3)2·3H2O aqueous solution to form Cu-alginate hydrogel under magnetic stirring at room temperature. The obtained hydrogel was separated from the solution after 6 h and washed with deionized water several times. The as-prepared Cu-alginate hydrogel was frozen by liquid nitrogen and then dried through freeze–drying for 24 h to obtain Cu-alginate aerogel.

Preparation of Cu3P@P/N-C

In a typical synthesis of Cu3P@P/N-C, Cu-aerogel was kept at 300°C for 1 h at a heating rate of 2°C min−1 under air atmosphere. After cooling to room temperature, the CuO@C nanosheets aerogel was collected (Figure S1). One hundred milligrams of the obtained CuO@C nanosheet aerogel and 200 mg red phosphorus were put into two separate ceramic boats in a tube furnace and then were heated to 800°C for 2 h under Ar atmosphere with a heating rate of 5°C min−1 to produce Cu3P@P/N-C. After cooling to room temperature, the sample was washed with deionized water three times by centrifugation and dried at 60°C in vacuum oven for 12 h.

Morphology and Structural Characterization

The morphology of the obtained samples was characterized by a field-emission scanning electron microscope (Hitachi Limited SU-8010) and transmission electron microscopy (JEOL-2100FS). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern was determined by PANalytical X'Pert PRO (PANalytical X'Pert PRO, monochromated Cu Kα radiation 40 mA, 40 kV) to characterize the crystal structure. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed with a Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha (Fisher Scientific Ltd., Nepean, ON).

Electrochemical Measurements

The anode slurry was prepared by mixing 70 wt% active materials, 20 wt% Super-P, and 10 wt% polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) by a high-speed electric agitator for 12 h. The slurry was pressed onto a cleaned copper foil by a doctor-balding method and dried in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 12 h. The performance of the SIBs was tested using standard 2032-type coin cells in an argon-filled glove box. The separator was glass fiber (GF/D) from Whatman, and sodium foils were used as the counter and reference electrodes. The electrolyte was 1.0 M NaClO4 in diethylene glycol dimethyl ether (Diglyme). The active material loading of the electrode was 0.5–0.8 mg cm−2. The cells were galvanostatically charged and discharged over a cutoff voltage window of 0.01–3.00 V at room temperature on a battery test system (Shenzhen Neware Electronic Co., China). Cyclic voltammetry behavior was studied by the CHI 650d electrochemical workstation at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1.

Results and Discussion

The carbon source we chose is sodium alginate. Sodium alginate is a natural polysaccharide extracted from brown seaweeds and some kinds of bacteria, which consists of a linear copolymer of (1–4)-linked β-D-mannuronic acid (M) and α-L-guluronic acid (G) in alternating blocks. Sodium alginate has high availability and biodegradability and low price. Its aqueous solution has a high viscosity and is non-toxic, which makes it widely useful as food thickeners, stabilizers, emulsifiers, etc. (Comaposada et al., 2015; Zou et al., 2018). In particular, sodium alginate can cross-link with di- or trivalent ions to form the uniform, transparent, water-insoluble, and thermo-irreversible gels at room temperature (Marcos et al., 2016). Scheme 1 exhibits the typical synthesis of Cu3P@P/N-C. Sodium alginate aqueous solution was added dropwise into Cu(NO3)2·3H2O aqueous solution to form Cu-alginate hydrogel balls. During the freezing process by liquid nitrogen, subsequently, the growth of the ice crystals squeezed the Cu-alginate macromolecules into 2D nanosheets. Then, the sample was dried by freeze drying. In the end, after the phosphorization procedure, Cu3P@P/N-C was obtained.

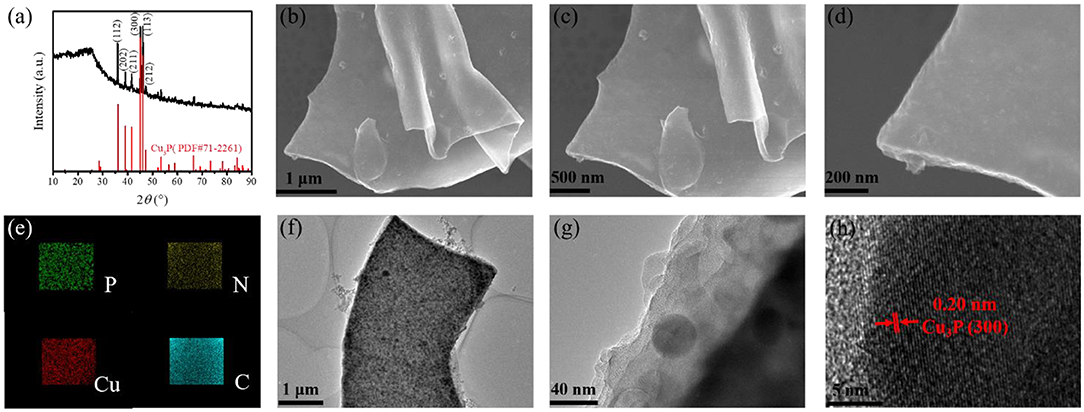

As shown in Figure 1a, the crystal structure and composition of the as-prepared samples were first tested by XRD measurements. There are several diffraction peaks in the XRD pattern of Cu3P@P/N-C at 36.0, 39.1, 41.6, 45.1, 46.1, and 47.3°. These peaks can be indexed to the (112), (202), (211), (300), (113), and (212) lattice planes of Cu3P crystalline (PDF#71-2261), matching well with a formerly reported study (Wang R. et al., 2018). In addition, there is a broad peak at around 24.7°, corresponding to the (002) plane of amorphous carbon. There are no other crystalline phases observed, which suggests that the as-prepared Cu3P@P/N-C has high purity.

Figure 1. (a) X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of Cu3P@P/N-C. (b–d) SEM images, (e) energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mappings, (f,g) transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images, and (h) high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of Cu3P@P/N-C.

The morphologies of the Cu-alginate aerogel and Cu3P@P/N-C were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Figure S2 exhibits the typical 2D nanosheet morphology of Cu-alginate aerogel. And as shown in Figures 1b–d, the 2D nanosheet morphology remained well after the phosphorization procedure. Figure 1e displays the typical energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mappings of Cu3P@P/N-C, where P, N, Cu, and C elements were observed, suggesting the homogeneous distribution of these several elements. The distribution of P element was uniform, indicating that P not only came from Cu3P but also doped in the carbon nanosheets. The typical 2D nanosheet morphology was also confirmed by the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of Cu3P@P/N-C (Figures 1f, g). The Cu3P nanoparticles with sizes of around 30 nm distributed uniformly as well as encapsulated in P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheets, which can not only provide rapid diffusion channels for the electron/ion but also prevent Cu3P nanoparticles from agglomeration. Figure 1h shows the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image in which the lattice fringes can be observed distinctly. The distance of these lattice fringes is 0.20 nm, matching well with the Cu3P crystalline (300) lattice plane (Liu et al., 2016), verifying the existence of the Cu3P nanoparticles.

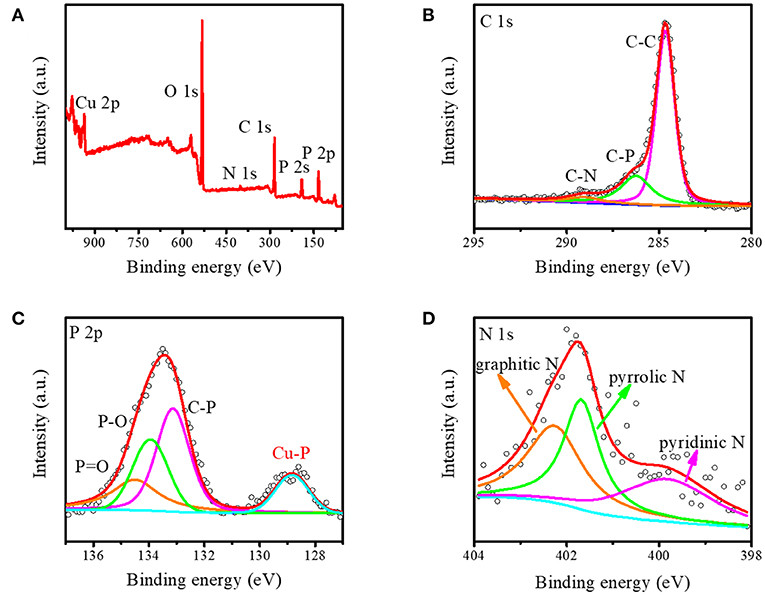

Furthermore, the X-ray photoelectron energy spectra (XPS) measurement was applied to study the detailed chemical states of Cu3P@P/N-C. As shown in Figure 2A, the signals of the C, N, O, P, and Cu elements were observed obviously without other impurities. The element O may come from the absorbed O species in the air. The N element came from the nitrate radical of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, which was not completely removed during the washing process. The C 1s spectrum in Figure 2B could be attributed to three peaks at 284.6, 286.3, and 289.1 eV. The major peak at approximately 284.6 eV was attributed to graphitic carbon. The other two peaks at 286.3 and 289.1 eV were fitted by carbon bonding with phosphorus and nitrogen, respectively, which can manifest the co-doping of both P and N atoms into the carbon nanosheets. The P2p spectrum in Figure 2C indicates the P chemical states in Cu3P@P/N-C. The P2p spectrum could be fitted into four peaks at 129.9, 134.2, 135.1, and 135.6 eV. The peak at 129.9 eV was attributed to the P in Cu3P. The two peaks at 135.1 and 135.6 eV were ascribed, respectively, to P–O and P=O bonds. And the peak at 134.2 eV could be ascribed to the C–P bond, corresponding to the C 1s bonding peak at 286.3 eV. The N 1s spectrum (Figure 2D) can be fitted into three component peaks at 399.4, 401.8, and 402.3 eV, which can be assigned to pyridinic nitrogen, pyrrolic nitrogen, and graphitic nitrogen, respectively. This could further confirm that both P and N are doped into the as-prepared carbon nanosheets.

Figure 2. (A) The integrated X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum and the corresponding XPS spectrum of (B) carbon, (C) phosphorus, and (D) nitrogen for Cu3P@P/N-C.

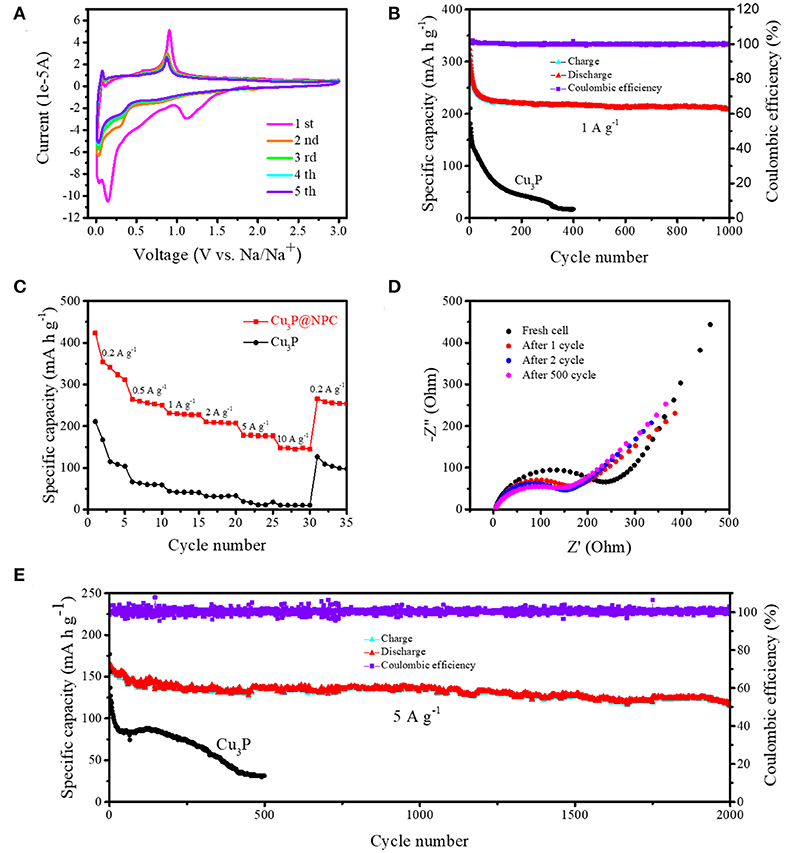

The electrochemical performance of Cu3P@P/N-C was measured in detail as anode materials for SIBs. First, its electrochemical reaction was studied by cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements from 0.01 to 3 V at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1 (Figure 3A). In the first cathodic process of the CV curves of Cu3P@P/N-C, there was a reduction peak at around 1.1 V, which can be associated with side reactions [the irreversible decomposition of the electrolyte and the formation of the solid electrolyte interface (SEI) layer on the electrode surface] (Zhu et al., 2019). Then, a strong reduction peak appeared between 0.07 and 0.4 V, which could be ascribed to the reaction of Cu3P with sodium. In the anodic scan process, the reverse of this reaction formed a distinct oxidation peak at around 0.9 V, as the following equation with the release of sodium ions shows:

The CV profiles from the second to the fifth cycles matched well, indicating the highly reversible and stable cycling performance of Cu3P@P/N-C as SIB anode materials.

Figure 3. (A) Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of Cu3P@P/N-C at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1 in the initial five cycles. (B) Cycling performance at a current density of 1 A g−1 and (C) rate performance of Cu3P@P/N-C and pure Cu3P. (D) Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) curves of Cu3P@P/N-C at different cycles during the first 500 cycles. (E) Cycling performance at a current density of 5 A g−1 of Cu3P@P/N-C and pure Cu3P.

Figure 3B shows the galvanostatic cycling performance of the Cu3P@P/N-C electrode under 1.0 A g−1 (0.01 and 3.0 V vs. Na+/Na). Pure Cu3P was also synthesized by the phosphorization of commercial Cu powder using red phosphorus as a P source for comparison (as shown in Figures S3–S5). Compared with pure Cu3P, the Cu3P@P/N-C electrode exhibited better electrochemical performance, maintaining an excellent reversible capacity of 209.3 mAh g−1 at 1.0 A g−1 after 1,000 cycles. The charge–discharge profiles of the initial three cycles of Cu3P@P/N-C are shown in Figure S6. The initial discharge and charge capacities were 1,029.6 and 562.3 mAh g−1; thus, the initial coulombic efficiency was 54.6%. This capacity loss was mainly caused by the irreversible formation of the SEI layer. Additionally, to estimate the sodium storage performance of the Cu3P@P/N-C electrode at a high rate, a high current density at 5.0 A g−1 was chosen. An outstanding cycling performance of 118.2 mAh g−1 is maintained (Figure 3E), even after 2,000 cycles. As shown in Table S1, Cu3P@P/N-C exhibited superior cycling performance and excellent rate performance. In sharp contrast to Cu3P@P/N-C, pure Cu3P had rapid capacity loss, resulting in only 44.0 mAh g−1 at 1.0 A g−1 after 200 cycles and 30.6 mAh g−1 at 5.0 A g−1 after 500 cycles. Thereby, the superior cycling performance of Cu3P@P/N-C reflects their structural stability as anode materials for SIBs. The SEM images and the EDX mappings of the selected area of Cu3P@P/N-C after 500 cycles are exhibited in Figures S7, S8. The typical nanosheet morphology of Cu3P@P/N-C can still be observed obviously, indicating its superior stability.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was investigated to further understand the cycling performance of Cu3P@P/N-C. As shown in Figure 3D, the semicircle in the high-frequency region corresponded to the charge transfer resistance of the electrode. The sloped line in the low-frequency region is attributed to the Warburg impendence. After the first cycle, the semicircle became much smaller, which could be explained by the formation of the SEI layer. The semicircles overlaid well after the second cycle, indicating the excellent cycling stability of Cu3P@P/N-C.

Figure 3C shows the rate performance of the Cu3P@P/N-C and pure Cu3P electrodes. The current densities were selected from 0.2 to 10 A g−1. The reversible specific capacities acquired were of 311.8, 250.3, 226.8, 207.2, 177.1, and 144.8 mAh g−1 at the current densities of 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 A g−1, respectively. When the current density was set back to 0.2 A g−1, the reversible specific capacity remained at 265.2 mAh g−1, suggesting the outstanding rate performance. On the contrary, pure Cu3P showed reversible specific capacities of only 104.0, 59.1, 41.0, 33.4, 18.1, and 10.2 mAh g−1 at the current densities of 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 A g−1, respectively, which were far inferior to those of Cu3P@P/N-C. The difference between these two materials could be ascribed to the introduction of P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheets, which could enhance the electron transfer during the discharge/charge process.

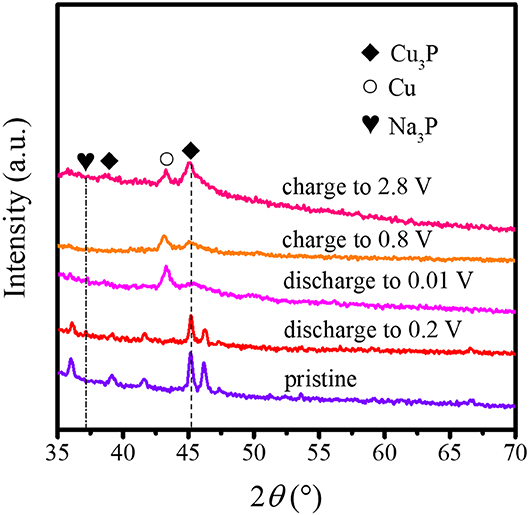

To further understand the electrochemical reaction process of the Cu3P@P/N-C electrode, we disassembled the cells for the ex situ XRD measurement at different states during the charge and discharge processes. As shown in Figure 4, the pristine Cu3P@P/N-C electrode only exhibited diffraction peaks of Cu3P. During the discharge process, the primary diffraction peak of Cu3P at around 45.1° corresponding to the (300) plane gradually receded and almost disappeared when completely discharged to 0.01 V. At the same time, a peak at about 43.5° came out, originating from the generation of Cu. In addition, a new peak came out at about 37° corresponding to the (103) plane of Na3P. During the charging process, the above composition change reversed. Such observations can identify the reversible sodiation/desodiation process of Cu3P conducting by conversion mechanism as in the following equation (Fan et al., 2016):

This conversion mechanism was consistent with the CV measurements.

Figure 4. Ex situ XRD patterns of Cu3P@P/N-C at different states during charge and discharge processes.

Conclusion

In summary, through a feasible aqueous reaction at room temperature followed by a phosphorization procedure, we have successfully fabricated biomass-derived P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheets encapsulating Cu3P nanoparticles as high-performance anode materials for sodium-ion batteries. Given the help of the 2D P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheets, the Cu3P nanoparticles could be well-encapsulated, thus being prevented from agglomeration. When applied as anode materials, superior cycling stability and excellent rate performance were exhibited. Prominently, Cu3P@P/N-C exhibited an outstanding reversible capacity of 209.3 mAh g−1 at 1 A g−1 after 1,000 cycles. In particular, an excellent specific capacity of 118.2 mAh g−1 could be maintained after 2,000 cycles, even at an ultrahigh current density of 5 A g−1. This remarkable electrochemical performance is mainly attributed to the rational design of the 2D P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheet structure, which could buffer the volume change of Cu3P nanoparticles as well as improve the electron/ion transport kinetics during the Na+ insertion/extraction process. Additionally, the 2D P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheets also could serve as a conductive matrix, which could enhance the electronic conductivity of the electrode. This feasible and facile preparation approach could be further developed to the synthesis of a variety of 2D P/N-co-doped carbon nanosheets encapsulating TMP electrodes for energy storage devices.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

YY and NZ contributed to the conception and design of the study. YY organized the database. YY, YZ, and NL performed the statistical analysis. YY wrote the manuscript. BS and NZ helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 21646012), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (nos. 2016M600253, 2017T100246), the State Key Laboratory of Urban Water Resource and Environment, Harbin Institute of Technology (no. 2019DX13), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. HIT. NSRIF. 201836). BS gratefully acknowledges financial support by the Australian Research Council (ARC) through the ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE180100036).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2020.00316/full#supplementary-material

References

Comaposada, J., Gou, P., Marcos, B., and Arnau, J. (2015). Physical properties of sodium alginate solutions and edible wet calcium alginate coatings. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 64, 212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.05.043

Fan, M., Chen, Y., Xie, Y., Yang, T., Shen, X., Xu, N., et al. (2016). Half-cell and full-cell applications of highly stable and binder-free sodium ion batteries based on Cu3P nanowire anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 5019–5027. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201601323

Fullenwarth, J., Darwiche, A., Soares, A., Donnadieu, B., and Monconduit, L. (2014). NiP3: a promising negative electrode for Li- and Na-ion batteries. Mater. J. Chem. A. 2, 2050–2059. doi: 10.1039/C3TA13976J

Ge, X., Li, Z., and Yin, L. (2017). Metal-organic frameworks derived porous core/shell CoP@C polyhedrons anchored on 3D reduced graphene oxide networks as anode for sodium-ion battery. Nano Energy 32, 117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.11.055

Hu, Y., Li, B., Jiao, X., Zhang, C., Dai, X., and Song, J. (2018). Stable cycling of phosphorus anode for sodium-ion batteries through chemical bonding with sulfurized polyacrylonitrile. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28:1801010. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201801010

Kim, Y., Park, Y., Choi, A., Choi, N.-S., Kim, J., Lee, J., et al. (2013). An amorphous red phosphorus/carbon composite as a promising anode material for sodium ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25, 3045–3049. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204877

Kong, M., Song, H., and Zhou, J. (2018). Metal–organophosphine framework-derived N,P-codoped carbon-confined Cu3P nanopaticles for superb na-ion storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 8:1801489. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201801489

Kundu, D., Talaie, E., Duffort, V., and Nazar, F. L. (2015). The emerging chemistry of sodium ion batteries for electrochemical energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3431–3448. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410376

Larcher, D., and Tarascon, M. J. (2015). Towards greener and more sustainable batteries for electrical energy storage. Nat. Chem. 7, 19–29. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2085

Li, F., and Zhou, Z. (2018). Micro/nanostructured materials for sodium ion batteries and capacitors. Small 14:1702961. doi: 10.1002/smll.201702961

Li, Z., Zhang, L., Ge, X., Li, C., Dong, S., Wang, C., et al. (2017). Core-shell structured CoP/FeP porous microcubes interconnected by reduced graphene oxide as high performance anodes for sodium ion batteries. Nano Energy 32, 494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.01.009

Liu, S., He, X., Zhu, J., Xu, L., and Tong, J. (2016). Cu3P/RGO nanocomposite as a new anode for lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 6:35189. doi: 10.1038/srep35189

Liu, Z., Yang, S., Sun, B., Chang, X., Zheng, J., and Li, X. (2018). Peapod-like CoP@C nanostructure from phosphorization in low-temperature molten salt for high-performance lithium ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 10187–10191. doi: 10.1002/anie.201805468

Lotfabad, M. E., Ding, J., Cui, K., Kohandehghan, A., Kalisvaart, P. W., and Hazelton, M. (2014). High-density sodium and lithium ion battery anodes from banana peels. ACS Nano 8, 7115–7129. doi: 10.1021/nn502045y

Ma, Y., Ma, Y., Bresser, D., Ji, Y., Geiger, D., Kaiser, U., et al. (2018). Cobalt disulfide nanoparticles embedded in porous carbonaceous micro-polyhedrons interlinked by carbon nanotubes for superior lithium and sodium storage. ACS Nano. 12, 7220–7231. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b03188

Marcos, B., Gou, P., Arnau, J., and Comaposada, J. (2016). Influence of processing conditions on the properties of alginate solutions and wet edible calcium alginate coatings. LWT Food Sci Technol. 74, 271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.07.054

Miao, X., Yin, R., Ge, X., Li, Z., and Yin, L. (2017). Ni2P@Carbon core–shell nanoparticle-arched 3D interconnected graphene aerogel architectures as anodes for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Small 13:1702138. doi: 10.1002/smll.201702138

Moreno, N., Caballero, A., Hernán, L., and Morales, J. (2014). Lithium–sulfur batteries with activated carbons derived from olive stones. Carbon 70, 241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.01.002

Pramanik, M., Tsujimoto, Y., Malgras, V., Dou, S. X., Kim, J. H., Yamauchi, Y., et al. (2015). Mesoporous iron phosphonate electrodes with crystalline frameworks for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Mater. 27, 1082–1089. doi: 10.1021/cm5044045

Qian, J., Wu, X., Cao, Y., Ai, X., and Yang, H. (2013). High capacity and rate capability of amorphous phosphorus for sodium ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 4633–4636. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209689

Qian, J., Xiong, Y., Cao, Y., Ai, X., and Yang, H. (2014). Synergistic Na-storage reactions in Sn4P3 as a high-capacity, cyclestable anode of na-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 14, 1865–1869. doi: 10.1021/nl404637q

Qiu, L., Xiang, W., Tian, W., Xu, C.-L., Li, Y.-C., Wu, Z.-G., et al. (2019). Polyanion and cation co-doping stabilized Ni-rich Ni–Co–Al material as cathode with enhanced electrochemical performance for Li-ion battery. Nano Energy. 63:103818. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.06.014

Song, J., Xiao, B., Lin, Y., Xu, K., and Li, X. (2018). Interphases in sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8:1703082. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201703082

Sun, J., Zheng, G., Lee, H.-W., Liu, N., Wang, H., Yao, H., et al. (2014). Formation of stable phosphorus-carbon bond for enhanced performance in black phosphorus nanoparticle-graphite composite battery anodes. Nano Lett. 14, 4573–4580. doi: 10.1021/nl501617j

Wang, J., Liu, Z., Zheng, Y., Cui, L., Yang, W., and Liu, J. (2017). Recent advances in cobalt phosphide based materials for energy-related applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 22913–22932. doi: 10.1039/C7TA08386F

Wang, R., Dong, X. Y., Du, J., Zhao, J. Y., and Zang, Q, S. (2018). MOF-derived bifunctional Cu3P nanoparticles coated by a N,P-codoped carbon shell for hydrogen evolution and oxygen reduction. Adv. Mater. 30:1703711. doi: 10.1002/adma.201703711

Wang, X., Chen, K., Wang, G., Liu, X., and Wang, H. (2017). Rational design of three-dimensional graphene encapsulated with hollow FeP@carbon nanocomposite as outstanding anode material for lithium ion and sodium ion batteries. ACS Nano 11, 11602–11616. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b06625

Wang, Y., Fu, Q., Li, C., Li, H., and Tang, H. (2018b). Nitrogen and phosphorus dual-doped graphene aerogel confined monodisperse iron phosphide nanodots as an ultrafast and long-term cycling anode material for sodium-ion batteries. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 15083–15091. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b03561

Wang, Y., Wu, C., Wu, Z., Cui, G., Xie, F., Guo, X., et al. (2018a). FeP Nanorod arrays on carbon cloth: a high-performance anode for sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 54, 9341–9344. doi: 10.1039/C8CC03827A

Wessells, D. C., Peddada, V. S. A., Huggins, R., and Cui, Y. (2011). Nickel hexacyanoferrate nanoparticle electrodes for aqueous sodium and potassium ion batteries. Nano Lett. 11, 5421–5425. doi: 10.1021/nl203193q

Wu, C., Hua, W., Zhang, Z., Zhong, B., Yang, Z., Feng, G., et al. (2018). Design and synthesis of layered Na2Ti3O7 and tunnel Na2Ti6O13 hybrid structures with enhanced electrochemical behavior for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 5:1800519. doi: 10.1002/advs.201800519

Wu, X., Fan, L., Wang, M., Cheng, J., Wu, H., Guan, B., et al. (2017). A long-life lithium-sulfur battery derived from nori based nitrogen and oxygen dual-doped 3D hierarchical biochar. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 18889–18896. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b04583

Wu, Y., Liu, Z., Zhong, X., Cheng, X., Fan, Z., and Yu, Y. (2018). Amorphous red phosphorus embedded in sandwiched porous carbon enabling superior sodium storage performances. Small 14:1703472. doi: 10.1002/smll.201703472

Xiao, Y., Wang, P.-F., Yin, Y.-X., Zhu, Y.-F., Niu, Y.-B., Zhang, X.-D., et al. (2018). Exposing {010} active facets by multiple-layer oriented stacking nanosheets for high-performance capacitive sodium-ion oxide cathode. Adv. Mater. 30:1803765. doi: 10.1002/adma.201803765

Xiao, Y., Zhu, Y., Xiang, W., Wu, Z., Li, Y., Lai, J., et al. (2020). Deciphering abnormal layered-tunnel heterostructure induced via chemical substitution for sodium oxide cathode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 1491–1495. doi: 10.1002/anie.201912101

Xu, X., Cao, R., Jeong, S., and Cho, J. (2012). Spindle-like mesoporous α-Fe2O3 anode material prepared from MOF template for high-rate lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 12, 4988–4991. doi: 10.1021/nl302618s

Zhang, B., Dugas, R., Rousse, G., Rozier, P. M., Abakumov, A., and Tarascon, J. N. (2016). Insertion compounds and composites made by ball milling for advanced sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 7:10308. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10308

Zhang, H., Hasa, I., and Passerini, S. (2018). Beyond insertion for Na-Ion batteries: nanostructured alloying and conversion anode materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 8:1702582. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201702582

Zhang, K., Park, M., Zhang, J., Lee, G.-H., Shin, J., and Kang, Y.-M. (2017). Cobalt phosphide nanoparticles embedded in nitrogendoped carbon nanosheets: promising anode material with high rate capability and long cycle life for sodiumion batteries. Nano Res. 10, 4337–4350. doi: 10.1007/s12274-017-1649-5

Zhang, Y., Wang, G., Wang, L., Tang, L., Zhu, M., Wu, C., et al. (2019). Graphene-encapsulated CuP2: a promising anode material with high reversible capacity and superior rate-performance for sodium-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 19, 2575–2582. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b00342

Zhou, J., Liu, X., Cai, W., Zhu, Y., Liang, J., Zhang, K., et al. (2017). Wet-chemical synthesis of hollow red-phosphorus nanospheres with porous shells as anodes for high-performance lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 29:1700214. doi: 10.1002/adma.201700214

Zhu, J., He, Q., Liu, Y., Key, J., Nie, S., Wu, M., et al. (2019). Three-dimensional, hetero-structured, Cu3P@C nanosheets with excellent cycling stability as Naion battery anode material. J. Mater. Chem. A. 7, 16999–17007. doi: 10.1039/C9TA04035H

Zou, Y., Chang, G., Chen, S., Liu, T., Xia, Y., Chen, C., et al. (2018). Alginate/r-GO assisted synthesis of ultrathin LiFePO4 nanosheets with oriented (0 1 0) facet and ultralow antisite defect. Chem. Eng. J. 351, 340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.06.104

Zou, Y., Yang, X., Lv, C., Liu, T., Xia, Y., Shang, L., et al. (2017). Multishelled Ni-Rich Li(NixCoyMnz)O2 hollow fibers with low cation mixing as high-performance cathode materials for li-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 4:1600262. doi: 10.1002/advs.201600262

Keywords: sodium-ion batteries, biomass, Cu3P, P/N-co-doped carbon, nanosheets

Citation: Yin Y, Zhang Y, Liu N, Sun B and Zhang N (2020) Biomass-Derived P/N-Co-Doped Carbon Nanosheets Encapsulate Cu3P Nanoparticles as High-Performance Anode Materials for Sodium–Ion Batteries. Front. Chem. 8:316. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00316

Received: 17 February 2020; Accepted: 30 March 2020;

Published: 05 May 2020.

Edited by:

Weijie Li, University of Wollongong, AustraliaCopyright © 2020 Yin, Zhang, Liu, Sun and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bing Sun, YmluZy5zdW5AdXRzLmVkdS5hdQ==; Naiqing Zhang, em5xbXd3QDE2My5jb20=

Yanyou Yin1

Yanyou Yin1 Bing Sun

Bing Sun