- 1Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

- 2UOP, A Honeywell Company, Des Plaines, IL, United States

The introduction of two distinct dopants in a microporous zeotype framework can lead to the formation of isolated, or complementary catalytically active sites. Careful selection of dopants and framework topology can facilitate enhancements in catalysts efficiency in a range of reaction pathways, leading to the use of sustainable precursors (bioethanol) for plastic production. In this work we describe our unique synthetic design procedure for creating a multi-dopant solid-acid catalyst (MgSiAPO-34), designed to improve and contrast with the performance of SiAPO-34 (mono-dopant analog), for the dehydration of ethanol to ethylene. We employ a range of characterization techniques to explore the influence of magnesium substitution, with specific attention to the acidity of the framework. Through a combined catalysis, kinetic analysis and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) study we explore the reaction pathway of the system, with emphasis on the improvements facilitated by the multi-dopant MgSiAPO-34 species. The experimental data supports the validation of the CFD results across a range of operating conditions; both of which supports our hypothesis that the presence of the multi-dopant solid acid centers enhances the catalytic performance. Furthermore, the development of a robust computational model, capable of exploring chemical catalytic flows within a reactor system, affords further avenues for enhancing reactor engineering and process optimisation, toward improved ethylene yields, under mild conditions.

Introduction

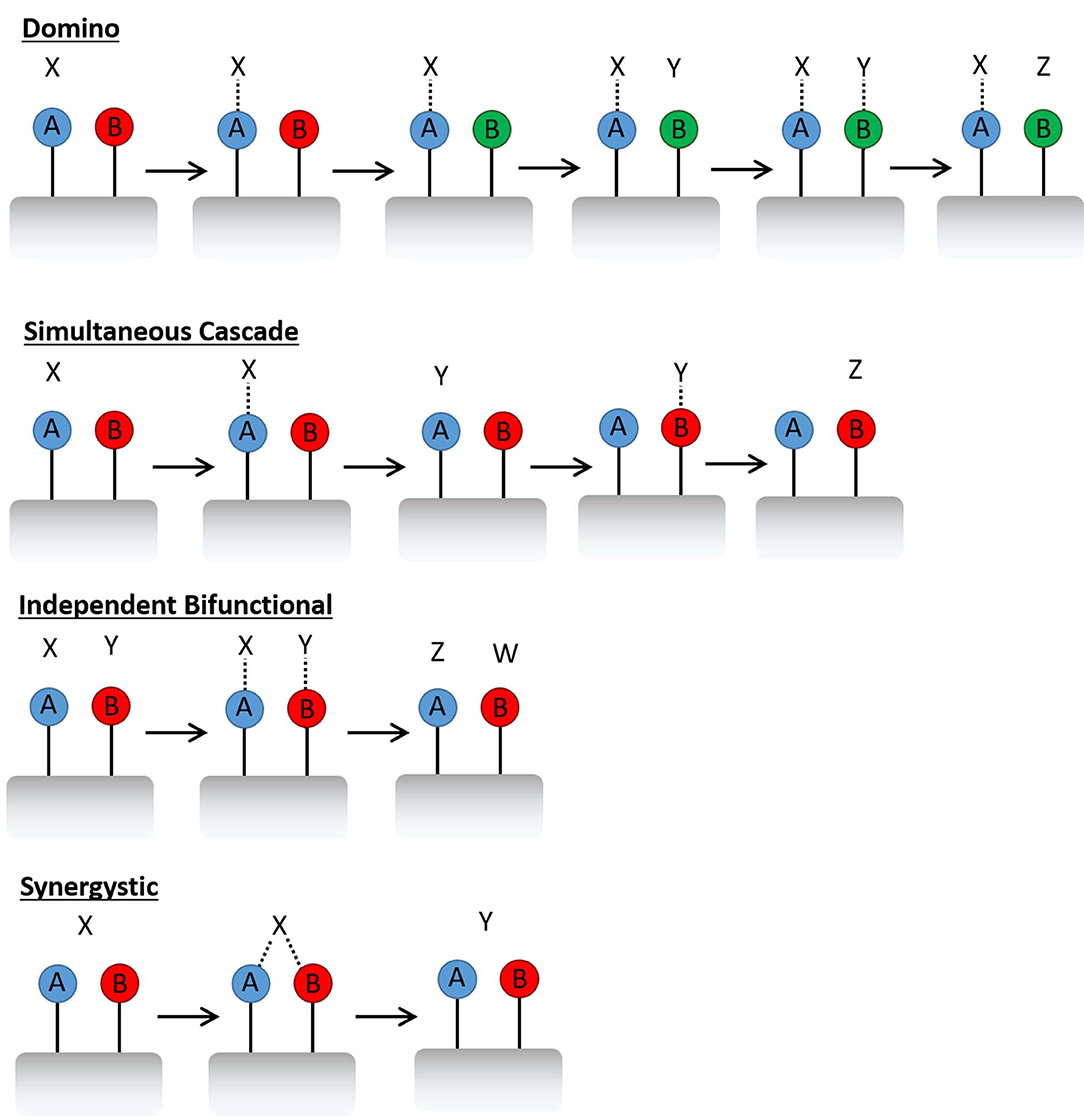

Rational catalytic design is an emerging theme that enables the targeted discovery of single-site heterogeneous catalysts (Thomas et al., 2005) that can be tailored for chemical applications, by dextrous manipulation of active sites within framework architectures. Many examples exist, where subtle modifications to a material, such as a change of active-site precursor, or variation in synthesis conditions, have facilitated significant catalytic improvements (Munnik et al., 2015; Rogers et al., 2017; Li Y. et al., 2018). While many systems have benefited from this type of synthetic optimisation, a large proportion of catalysts have been improved by the addition of a second metal (Thomas and Raja, 2005; Huo et al., 2011; Alonso et al., 2012; Villa et al., 2015; Xiao and Varma, 2018). Metallic promoters are common place in industry, often used to improve the catalysts lifetime, making it less susceptible to coking or sintering (De et al., 2016). Though a second metal site also offers a range of catalytic possibilities in multi-step catalysis, such as the creation of bifunctional materials for domino or simultaneous cascade reactions (Figure 1) (Zeidan et al., 2006; Paterson et al., 2011; Bui et al., 2013). In such processes, one active site will form an intermediate, which either triggers the next active site (domino) (Bui et al., 2013) or results in a product which initiates the next process (simultaneous cascade) (Zeidan et al., 2006). The active site can also be designed in such a way that two metals perform complementary roles, where either, each active site performs an unique role in a concerted fashion, or can synergistically enhance the same role (Leithall et al., 2013).

In all cases the precise proximity of the two metals, at the atomic level, is vital for engineering improved catalytic behavior, thus must be carefully controlled (Leithall et al., 2013; Potter et al., 2015). Creating multi-dopant entities is often trivial, and readily achieved through simplistic impregnation and deposition processes; however this seldom gives predictive control over the relative locations of the two metals (Jiang et al., 2015). A range of synthetic techniques can promote interactions between the different metals, this is particularly true in nanoparticle design, where core-shell nanoparticles encourage partial mixing of two different metals (Price et al., 2011). Similarly alloyed multi-dopant nanoparticles can be synthesized (Hermans et al., 2001; Raja et al., 2001; Hungria et al., 2006; Adams et al., 2013) in situ or formed through precursors complexes such as Ir3(CO)9(μ3-Bi) which decomposes to yield Ir3Bi nanoparticles on a suitable support (Adams et al., 2013). While elegantly designed, such metallic nanoparticles are often prone to oxidation, agglomeration and sintering under intense reaction conditions. In contrast, isomorphous framework substitution, where the dopant metal forms a part of the structural framework, often lead to more resilient species. Zeotype frameworks, particularly aluminophosphates (AlPOs), are excellent hosts for this type of substitution pathway. The basic AlPO framework is constructed of alternating AlO4 and PO4 tetrahedra, joined through corner sharing Al-O-P bonds. These primary building units (PBUs) then combine to form a range of secondary building units (SBUs), which are typically based on combinations of 4 and 6 membered rings. The type and binding motifs of these SBUs then leads to the formation of a specific microporous framework, with pore dimensions ranging from 3 to 8 Å (Pastore et al., 2005).

By substituting framework Al3+ or P5+ species with dopant metals it is possible to engineer a range of active sites. Redox active sites are created by substituting aluminum with a M2+/3+ species, such as cobalt, iron, manganese etc., this allows the metal to alternate between the adjacent available oxidation states, creating the redox species (Frache et al., 2003; Beale et al., 2005). Solid-acid sites, can be introduced into an AlPO framework facilely, but more importantly, the nature and choice of dopant (mono- or multi-), can advantageously modulate the acid strength of the resulting catalyst (Saadoune et al., 2003; Dai et al., 2013; Potter et al., 2013, 2018b; Gianotti et al., 2014; Mortén et al., 2018). This is achieved by deliberately creating a charge imbalance in the framework, such as substitution Al3+ with a divalent species such as magnesium or nickel (Saadoune et al., 2003; Mortén et al., 2018), or substituting P5+ with a tetravalent species such as Si4+ or Ti4+ (Figure S1) (Dai et al., 2013; Mortén et al., 2018; Potter et al., 2018b). Acid characteristics of the different species depend on many variables including the size and electronegativity of the metal, the precise substitution mechanism and the framework topology of the AlPO structure (Corà et al., 2003). In our previous work, we show the inclusion of multiple dopant sites is also a viable technique to control the acidity of metal-substituted aluminophosphates (Potter et al., 2013; Gianotti et al., 2014). This led to the synthesis of a novel Mg2+Si4+AlPO-5 catalyst, which outperformed the analogous mono-dopant Mg2+AlPO-5 and Si4+AlPO-5 for the both alkylation of benzene, and the Beckmann rearrangement of cyclohexanone oxime, despite the reactions requiring differing acid strengths (Potter et al., 2013; Gianotti et al., 2014). The findings from this study were instrumental in the predictive design of solid catalysts for the acid catalyzed dehydration of ethanol (Potter et al., 2014, 2018a), where we have shown that SiAlPO-34 is a promising catalyst for converting ethanol to ethylene at low (<250°C) temperatures. This is partially attributed to the isolated silicon sites creating effective acid centers, but also the constricting micropores of SiAlPO-34 (3.8 Å), that promote the formation of ethylene over the larger diethyl ether intermediate. In principle, it is possible to keep increasing the amount of Si in the synthesis gel to enhance the concentration of active sites. However, in our previous work (Potter et al., 2017) we have shown that increasing the Si quantity leads to type III substitution and Si islanding, lowering the overall number of acid sites. We have therefore decided instead to keep the Si loading constant, relative to our SAPO-34 procedure, and instead add a second dopant. To probe the mechanism of the acid-catalyzed process we required a metal with limited redox capability, that would undergo type I substitution, to not compete with the Si for phosphorus substitution (type II). Mg is known to produce stronger Brønsted acid sites when inserted into an AlPO framework (Potter et al., 2013; Gianotti et al., 2014), therefore allowing us to probe the influence of additional stronger acid sites on our catalytic pathway. As such, MgSiAlPO-34 was chosen, as one can control the isomorphous substitution of Mg(II) sites in framework positions of Al(III) sites via a type 1 substitution mechanism, yielding isolated active sites for probing the influence of stronger acid sites on the kinetic pathway of ethanol dehydration.

Zeolites have also been widely used in the dehydration of ethanol to ethylene (Phung et al., 2015; Kadam and Shamzhy, 2018; Li X. et al., 2018; Masih et al., 2019), facing similar challenges of selectively forming ethylene at lower temperatures. It has been shown that zeolites preferentially form diethyl ether at lower temperatures, and that ethylene formation is only favored above 215°C (Kadam and Shamzhy, 2018). Though H-FER and H-USY can achieve high ethylene yields at 300°C, however similar systems are hampered by the formation of longer-chain by-products, leading to coking (Phung et al., 2015; Li X. et al., 2018). In our previous work with SAPO-34 we did not see any products aside from diethyl ether and ethylene, suggesting that the smaller pore may play a significant role in ethylene formation (Potter et al., 2014, 2018a). The benefits of smaller pores have been investigated by others, comparing RHO and MFI zeolites, where the smaller pore of RHO lead to superior ethylene selectivity, alongside a higher quantity of medium-strong acid sites (Masih et al., 2019). As such, we discuss the design of the multi-dopant MgSiAPO-34 framework, and the effect the inclusion of magnesium has on the resulting acid strength, catalytic performance, and reactor design through computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations.

Various forms of MgSiAlPO-34 have previously been synthesized (Zhang et al., 2008; Salmasi et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2017; Abdulkadir et al., 2019), with particular emphasis on the methanol-to-olefin (MTO) reaction, where SiAlPO-34 has been the industrial standard for many decades. Work by Salmasi et al. showed that adding magnesium to the SiAlPO-34 framework reduced the total number of acid sites, but resulted in a greater proportion of “strong” acid sites (Salmasi et al., 2011). This led to superior catalytic performance over a longer time period, extending the lifetime of the system. This finding was counter-intuitive, as framework substituted magnesium typically creates stronger acid sites, and therefore the above finding could result from the formation of extra-framework magnesium sites (Salmasi et al., 2011). The latter is evidenced from reports on varying the magnesium content of the SiAlPO-34 species (Zhang et al., 2008), where initially small amounts of magnesium in the framework (0.33 wt%) result in increased overall acidity. However, higher loadings (0.83 and 1.65 wt%) significantly decreases the acidity to 85 and 58 % (respectively) of the original SiAlPO-34 system. It was however shown that, with the exception of the highest loading of magnesium (1.65 wt%), the other catalysts resulted in improved activity for the conversion of chloromethane to C2-C3 hydrocarbons. We therefore intend to see the influence of incorporating small quantities of Mg2+ ions into the framework of SiAlPO-34, using a unique synthesis procedure, to promote isomorphous substitution of Mg2+ and Si4+ ions, as single-site entities. In line with our previous work, we have carried out in-depth kinetic analysis of solid acid catalyzed dehydration of ethanol to ethylene, as a function of time and temperature, to directly probe the effect of adding magnesium to the framework (Potter et al., 2018a). We will then use these findings as an input for the experimentally defined CFD simulations, to explore local variations in the chemical concentrations across the catalyst bed, with the intention of simultaneously optimizing catalyst and reactor design (Potter et al., 2018a).

Confirming the Structural Integrity of MgSiAlPO-34

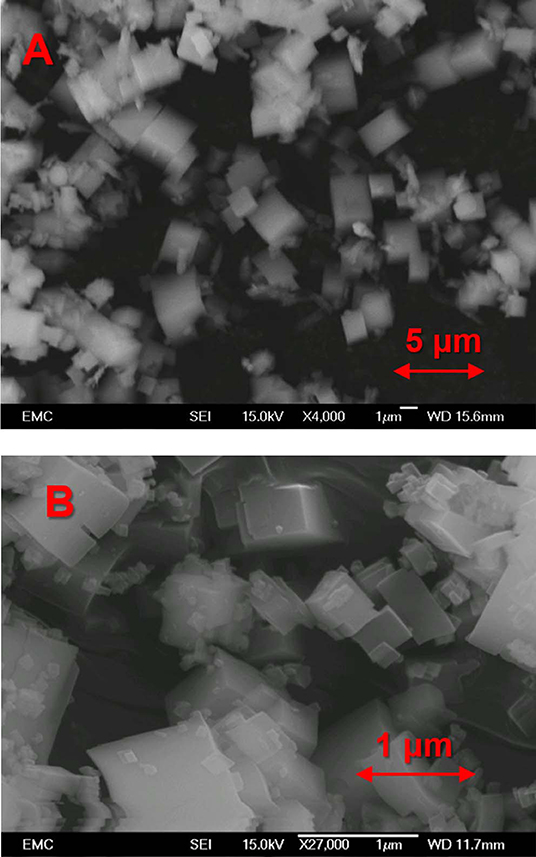

In our previous work (Potter et al., 2014, 2018a) we have developed synthesis methods to create a phase-pure crystalline SiAlPO-34 catalysts, utilizing tetraethylammonium hydroxide as the structure directing (templating) agent. To synthesize MgSiAlPO-34 we modified this protocol to incorporate a small fraction of magnesium (molar ratio Mg:Si = 1:15), with the aim of limiting extra-framework Mg, promoting isomorphous substitution. This represents the first case (to our knowledge) of MgSiAlPO-34 being synthesized in the absence of triethylamine or morpholine, with all previous reports utilizing either of these templates. The result of our unique multi-dopant synthesis protocol was characterized using a range of physicochemical and in situ spectroscopy techniques to confirm the structural integrity of the catalyst, and to explore the influence of magnesium on the acidic properties. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed that our MgSiAlPO-34 catalyst exclusively contains chabazite (CHA) (Figure S2) (Wragg et al., 2012), as expected for the SiAlPO-34 framework, with no visible signs of extra-framework MgO, or any other crystalline phases. On performing a Reitveld refinement (Table S1), the unit cell parameters show excellent agreement with our analogous SiAlPO-34 species, which further confirms phase purity. N2 physisorption experiments were used to probe the porosity of the system, and in combination with the XRD findings, confirmed the microporous nature of the system (Table S2), in agreement with the SiAlPO-34 (Sun et al., 2014). To investigate the crystallinity of the system scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to explore the particle morphology, showing smooth cubic crystals of around 1-2 μm in length (Figure 2). Again this is in good agreement with previous observations (Potter et al., 2014, 2018a). ICP analysis (Table S3) shows similar levels of Al, P and Si in the MgSiAlPO-34 and SiAlPO-34 catalysts, as variations are within experimental error. We were however successful in incorporating only a small amount of magnesium into the MgSiAlPO-34 framework, as intended, and lower than any previous studies. The combination of these findings suggests there are very little physicochemical differences on introducing magnesium to the framework. Therefore, we can attribute any changes in acidity or catalytic activity to the nature of the active site.

Figure 2. SEM images of (A) MgSAPO-34 and (B) SAPO-34, both showing predominantly cubic crystals of 1–2 μm in size in both cases.

Influence of Magnesium on Framework Atoms

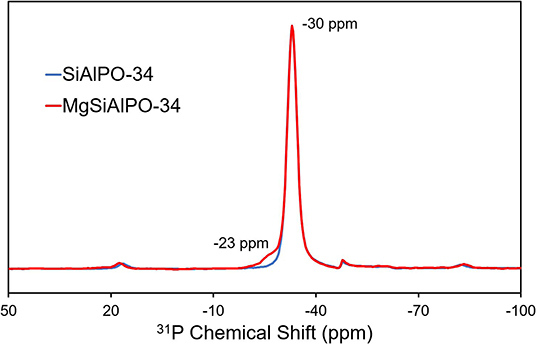

The local environment of the framework elements; aluminum, phosphorus and silicon, can be probed using 27Al, 31P and 29Si solid state NMR (respectively). Due to the low loading of magnesium (0.12 wt%), we did not explore the magnesium environment by ssNMR; furthermore, 25Mg has a very low sensitivity for NMR, poor natural abundance and quadrupolar. 27Al of MgSiAlPO-34 (Figure S3A) shows a peak at 33 ppm, attributed to a Al(OP)4 species, with peak shape and position in excellent agreement with SiAlPO-34 (Buchholz et al., 2003). Subtle differences between the spectra occur in the 10–12 ppm region, which is typically attributed to surface alumina sites, bound to water or templating agents (Buchholz et al., 2003). Here we can see MgSiAlPO-34 shows a paucity of these sites, suggesting a slightly more crystalline framework. Probing the 31P nuclei (Figure 3) shows a near identical P(OAl)4 species at −30 ppm (Buchholz et al., 2003), again showing a nearly identical peak shape to SiAlPO-34, suggesting that the inclusion of magnesium does not significantly influence this feature. However, MgSiAlPO-34 shows an additional feature at −23 ppm, which has previously been attributed to P(OAl)3(OMg) species (Deng et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2008), suggesting that magnesium has indeed been isomorphously substituted into the framework, occupying an aluminum site via type I substitution (Gianotti et al., 2014). Similarly the 29Si NMR (Figure S3B) is in excellent agreement between the two catalysts, both show a prominent signal at −95 ppm, attributed to Si(OAl)4 environments, suggesting type II substitution (Gianotti et al., 2014) and isolated silicon atoms (Blackwell and Patton, 1988). Again, identical line shape shows the addition of small quantities of magnesium has no significant effect on this feature. Therefore, we conclude that MAS NMR demonstrates that the addition of magnesium has only subtly changed the chemical environments of the framework, with the 31P NMR showing the presence of framework-substituted magnesium ions (Figure 3).

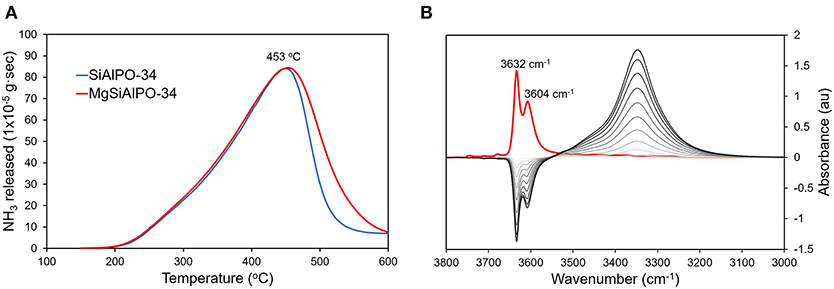

Ammonia-probed temperature programmed desorption (NH3-TPD) was used to explore the influence of magnesium on the acidity of the catalyst. The TPD data for MgSiAlPO-34 and SiAlPO-34 show near identical behavior up until 450°C (Figure 4A). This suggests that the weaker acid sites, attributed to framework silicon and surface hydroxyl groups, are unaffected by magnesium. Above 450°C, MgSiAlPO-34 shows notably more stronger acid sites, whereas SiAlPO-34 shows a steep decline, indicating fewer stronger acid sites. Throughout our discussion we carefully use the word “stronger” to describe the Mg acid sites. As although these acid sites are among the strongest one can engineer into an AlPO framework, they are still notably weaker than those in zeolites and other solid acid catalysts. Quantifying the area under these signal (Tables S4, S5) shows that MgSiAlPO-34 has significantly more acid sites than SiAlPO-34 (0.944 and 0.822 mmol/g, respectively). We note that the small differences in silicon loading (SiAlPO-34 3.4 wt%, MgSiAlPO-34 3.6 wt%, Table S3) is not significant to account for the difference in acid sites measured by NH3-TPD, further inferring that the incorporation of magnesium has a notable influence. We note that from ICP analysis, SiAlPO-34 should theoretically have 1.211 mmol/g of acid sites (based on Si loading), and MgSiAlPO-34 should have 1.335 mmol/g of acid sites (on the basis of Mg + Si loading), which is higher than the values detected by NH3-TPD (Table S6). As the 29Si NMR revealed the presence of isolated silicon species, we believe that the discrepancy between the theoretical and experimental NH3-TPD values must arise from pore-blockage. As SiAlPO-34 is a small-pored framework (3.8 Å), then it is conceivable that bound NH3 species could block the pores, hindering access to other available sites. We also note that MgSiAlPO-34 has a greater number of stronger acid sites (>450°C) than SiAlPO-34, and also a greater proportion of stronger acid sites (by 15%). This is in good agreement with previous findings (Zhang et al., 2008), who also showed the total acidity would increase, when Mg loadings below 0.33 wt% were included in the SAPO-34 catalyst. As our Mg loading is 0.11 wt% (Table S3), our results are in good agreement with these findings. Overall this suggests that substituting magnesium into the framework results in the formation of stronger acid sites, in accordance with previous experimental and computational findings (Corà et al., 2003; Potter et al., 2013; Gianotti et al., 2014).

Figure 4. (A) NH3-Temperature Programmed Desorption (TPD) data comparing the total number, and relative strength of acid sites in MgSAPO-34 and SAPO-34 and (B) in situ FTIR data showing CO absorption on MgSAPO-34.

FT-IR experiments focussing on the hydroxyl region (3800 – 3000 cm−1) of dry MgSiAlPO-34 reveal analogous characteristics toSiAlPO-34 (Figures S4A,B), showing two strong hydroxyl features at 3,632 and 3,604 cm−1, which can be attributed to Brønsted acid sites from silicon framework substitution, giving Al-OH-Si species (Figure S4A) (Smith et al., 1996; Bordiga et al., 2005; Martins et al., 2007). The peak is split due to the two different OH positions, with protons residing in either the 6 or the 6-6 SBUs (Smith et al., 1996; Bordiga et al., 2005; Martins et al., 2007). We also see the typical P-OH band at around 3,678 cm−1 and a band at 3,748 cm1, attributed to extra framework Si-OH species, both of which are ubiquitous in SiAlPO materials (Figure S4B) (Smith et al., 1996; Bordiga et al., 2005; Martins et al., 2007). A feature, unique to MgSiAlPO-34, is also present at 3,711 cm1, which can be attributed to the presence of magnesium in the system. On dosing MgSiAlPO-34 with CO to collect in situ FT-IR data, the peaks at 3,632 and 3,604 cm1 completely diminish, showing that protons are able to interact with the CO probes (Figure 4B). The CO binding causes a shift in the frequency of the hydroxyl group, to a lower energy, as seen by the appearance of a feature at 3,343 cm−1 (Smith et al., 1996; Bordiga et al., 2005; Martins et al., 2007). In the CO stretching region (2250 – 2100 cm−1), two features appear with increasing CO concentrations. The primary feature at 2,172 cm−1 is attributed to CO bound to Brønsted acid sites, while the secondary feature at 2,141 cm−1 is physisorbed “liquid-like” CO (Figure S4C) (Smith et al., 1996; Bordiga et al., 2005; Martins et al., 2007). Again, this is in excellent agreement with our previous work on SiAlPO-34 (Potter et al., 2018a). Integrating the CO signal gives a value of 1.39 au for MgSiAlPO-34, compared to 1.08 au for SiAlPO-34, confirming that the addition of magnesium increases the number of acid sites, as seen through NH3-TPD.

Catalytic Behavior of MgSiAlPO-34

The efficacy of the multi-dopant substitution in MgSiAlPO-34 was contrasted with the mono-dopant SiAlPO-34, by using the low-temperature, catalytic dehydration of ethanol as a model reaction. The wider benefits of designing catalysts that can operate at low-temperatures, notwithstanding the energy savings, extends scope for deployment of bio-based feedstocks, such as bioethanol that can be derived from sugarcane waste (bagasse) and corn. Bioethanol has been identified as a possible sustainable energy source for the future with developing countries such as Brazil already utilizing a significant amount for fuel, from the fermentation of sugar cane (Hira and Guilherme de Oliveira, 2009). Extending this notion it is possible to also use bioethanol as a feedstock for bulk and fine chemical production Hira and Guilherme de Oliveira (2009) reducing the requirements for crude oil. Ethylene is used globally as a plastic and pharmaceutical precursor, the vast majority coming from steam cracking (Zhang and Yu, 2013), and low-temperature dehydration of bioethanol could offer a sustainable solution for ethylene production.

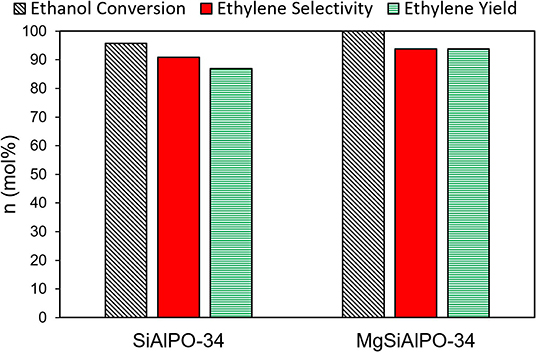

Under identical reactions conditions, MgSiAlPO-34 achieves an overall ethylene yield of 94 mol%, compared to 87 mol% for SiAlPO-34 (Figure 5 and Table S7), highlighting the benefits of our design strategy to form a multi-dopant catalyst. The improved catalytic behavior is likely due to the addition of “stronger” acid sites from magnesium doped into the framework. As we saw no other products, we can conclude that these Mg acid sites were not sufficiently strong enough to enforce unwanted side reactions, such as ethylene polymerisation, and are therefore more favorable than those present in zeolites. In order to better understand the influence of magnesium, a kinetic study was performed, varying contact time, and temperature, to contrast with previous work on SiAlPO-34. We also show that the MgSiAlPO-34 maintains a high level of activity after 7 h on stream (Figure S5), analogous to SiAlPO-34 in our previous work (Potter et al., 2018a), vindicating the stability of our catalyst.

Figure 5. Comparing the ethylene production of SAPO-34 and MgSAPO-34 catalysts at 225°C, 0.3 g catalyst, He carrier gas = 25 mL/min, WHSV = 0.3 hr−1.

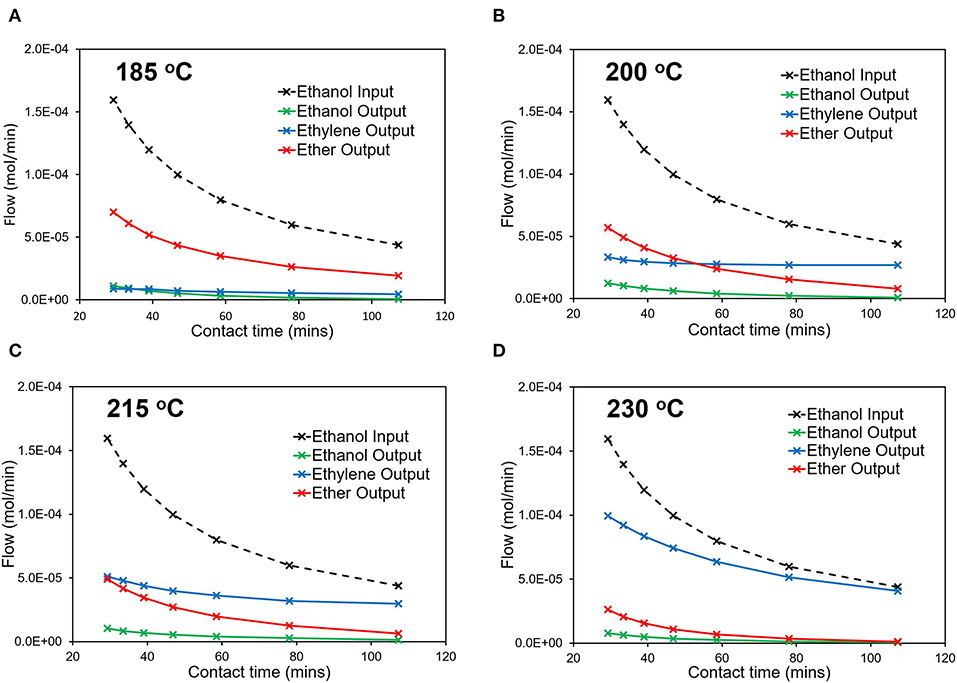

Varying ethanol contact time with the multi-dopant catalyst (MgSiAlPO-34), influences the overall reactivity (Figure 6) and, even at the lowest temperature (185°C), a significant amount of ethanol is converted (Figure 6A), primarily forming the intermediate, diethyl ether. The flows are expressed as mol/min for ease of translating to kinetic and CFD analysis. However, care must be taken, as the ethanol input (mol/min) will not necessarily equal the sum of the output flows, due to two moles of ethanol being required to form one mole of diethyl ether. In doing so, this calculation leads to an accurate carbon balance, but cannot always lead to an accurate mole balance. With increased contact times, the ethanol output continues to decrease, suggesting higher conversions at higher contact times. Also while diethyl ether remains the primary product, the relative amount of ethylene increases as contact time increases. This is in line with our previous observations on mono-dopant SiAlPO-34 (Potter et al., 2018a), suggesting at low temperatures the dominant reaction is the formation of diethyl ether. Increasing the temperature, we see a similar trend for the conversion, with minimal ethanol in the output stream, which continues to decreases with increasing contact times. The product distribution also varies, with increasing temperatures, resulting in increased ethylene yields, and lowering diethyl ether formation. To emphasize this point, above 215°C (Figures 6C,D) ethylene becomes the primary product, under our conditions. This is in line with the decomposition of diethyl ether to ethylene, as this is a limiting step in this process (Potter et al., 2018a). Further, the relative amount of ethylene continues to increase as a function of contact time. This is best shown at 200°C (Figure 6B), where the primary product switches from diethyl ether to ethylene in the 40–60 min contact time range. This transition occurs at a lower temperature than SiAlPO-34, where ethylene only becomes the primary product at 215°C (Figure 6C). This suggests that the increased number of stronger acid sites in MgSiAlPO-34, due to the inclusion of magnesium in the framework, is able to promote the formation of the desired ethylene product.

Figure 6. Catalytic data detailing how the output stream composition varies with contact time at (A) 185°C, (B) 200oC, (C) 215oC, and (D) 230°C.

Kinetics

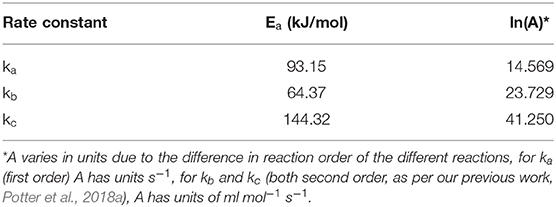

The rate constants for the three steps were determined in an analogous fashion to our previous work on SiAlPO-34 (Potter et al., 2018a). The product distributions, varying as a function of contact time, were used as inputs to calculate the rate constants of the three steps, at the different temperatures and flow rates. The open-source software Copasi (Hopps et al., 2006) was used to calculate the rate constants for all three steps (Figure S6). We present the individual rate constants established using the multi-set data for the different experimental cases. As per our previous work (Potter et al., 2018a), the individual cases were considered to ascertain whether any reactions are kinetically limited (constant with varying WHSV) or diffusion limited (varying with WHSV). The present studies show the rate constants for the multi-dopant MgSiAlPO-34 differ from those presented previously for SiAlPO-34. For SiAlPO-34, the rate constants for reactions a and b (ka and kb) were roughly constant, regardless of the WHSV, therefore these steps were considered kinetically limited. On the other hand, the rate constants for step c (kc) decreased with increasing flow, suggesting it was diffusion limited at lower WHSVs. With the MgSiAlPO-34, ka, kb and kc vary with increasing WHSV (Figure S6), before converging at higher WHSVs in the range of 0.92–1.47 hr−1. This suggests that in the current MgSiAlPO-34 case, the chemical transformations, at low flow rate, are occurring sufficiently fast that the reaction is now limited by diffusion, due to poor mass-transfer. This deviation is most pronounced at highest temperature studied (230°C), as again the kinetic reaction is occurring so rapidly, that the diffusion of reactants and products to the active site, is not the rate determining step. The convergence of the rate constant at higher flows shows the reaction transitions to being chemically limited, likely due to shorter contact time, leading to the formation of fewer ethoxy intermediates. Therefore, our investigation will consider the kinetic rate constant values for the higher WHSVs (0.92–1.47 hr−1) only, ensuring we are in the kinetically limited regime, to extract the activation energy and pre-exponential factors via an Arrhenius plot (Table 1 and Figures S7, S8). In this region the Arrhenius plot followed a linear trend (Figure S7), yielding ln(A) and Ea values in a similar range to those of SiAlPO-34 (Table 1 and Figure S9). Comparing these rate constants as a function of temperature (Figure S8) should be done carefully, as the rate constants have different units due to their different orders; ka being first order (s−1) and kb and kc are second order (ml mol−1 s−1). As such direct comparison is only possible between kb and kc, both increase as expected with temperature (Figure S8) however due to the higher activation energy and pre-exponential factor (Table 1) kb increases more drastically with temperature than kc. This suggests step c (ethylene formation from diethyl ether) is more susceptible to increases in temperature than step b (diethyl ether formation).

Table 1. Calculated activation energies and pre-exponential factors for the rate constant of the individual reaction steps of MgSiAlPO-34, using the 0.92–1.47 hr−1 WHSVs cases.

Comparing the Arrhenius plots of MgSiAlPO-34 and SiAlPO-34 (Figures S7–S9) shows the influence of the additional stronger Brønsted acid sites, brought about by the incorporation of Mg2+ ions into the framework. For SiAlPO-34, step a was found to have little influence on the activity of the system, and in the MgSiAlPO-34 case, we see that the rate constants are even lower (Figure S9A), suggesting this will play even less of a role under the conditions studied. Extending the data points to higher temperatures would see the MgSiAlPO-34 ka surpass that of SiAPO-34, and potentially lead to this pathway becoming more significant, suggesting that stronger acid sites can promote the direct dehydration of ethanol to ethylene under certain conditions (further work in progress and outside the scope of this study). We note that kb shows a significant decrease in activation energy on including Mg2+ ions (Figure S9B), with MgSiAlPO-34 having an activation energy of 64.4 kJ/mol, compared to SiAlPO-34 with 70.7 kJ/mol (Potter et al., 2018a). Therefore, we can conclude that the presence of stronger acid sites in the multi-dopant catalyst lowers the energy barrier for the formation of the diethyl ether intermediate. MgSiAlPO-34 showed higher kb values across the whole temperature range studied, and the lower activation energy also confirms that it would be a more suitable candidate for diethyl ether (and ethylene) production at lower temperatures. In terms of kc (Figure S9C), the activation energy of the two species is almost identical, suggesting the enhanced acidity has little influence on the decomposition of diethyl ether to yield ethylene, step c (page S4). MgSiAlPO-34 however maintains a higher rate constant than SiAlPO-34, due to a higher pre-exponential factor, suggesting a greater number of collisions between the molecules. This may simply be a product of the greater number of acid sites present in the MgSiAlPO-34 (0.944 mmol/g) compared to SiAPO-34 (0.822 mmol/g), providing more sites to facilitate this reaction, or to a more specific interplay between these sites located a proximal positions within the framework (Potter et al., 2013, 2014, 2018a; Gianotti et al., 2014). However, the similar activation energies suggest that the change in overall acid site strength has little influence on the reaction pathway. Therefore, we conclude the enhanced catalytic activity of the MgSiAlPO-34 over SiAPO-34 is due to the stronger acid sites, generated through multi-dopant substitution, promoting the formation of the diethyl ether intermediate, and the subsequent modulation of Mg2+Si4+ active species providing more sites to form ethylene form the diethyl ether.

Computational Fluid Dynamics of the MgSiAlPO-34 System

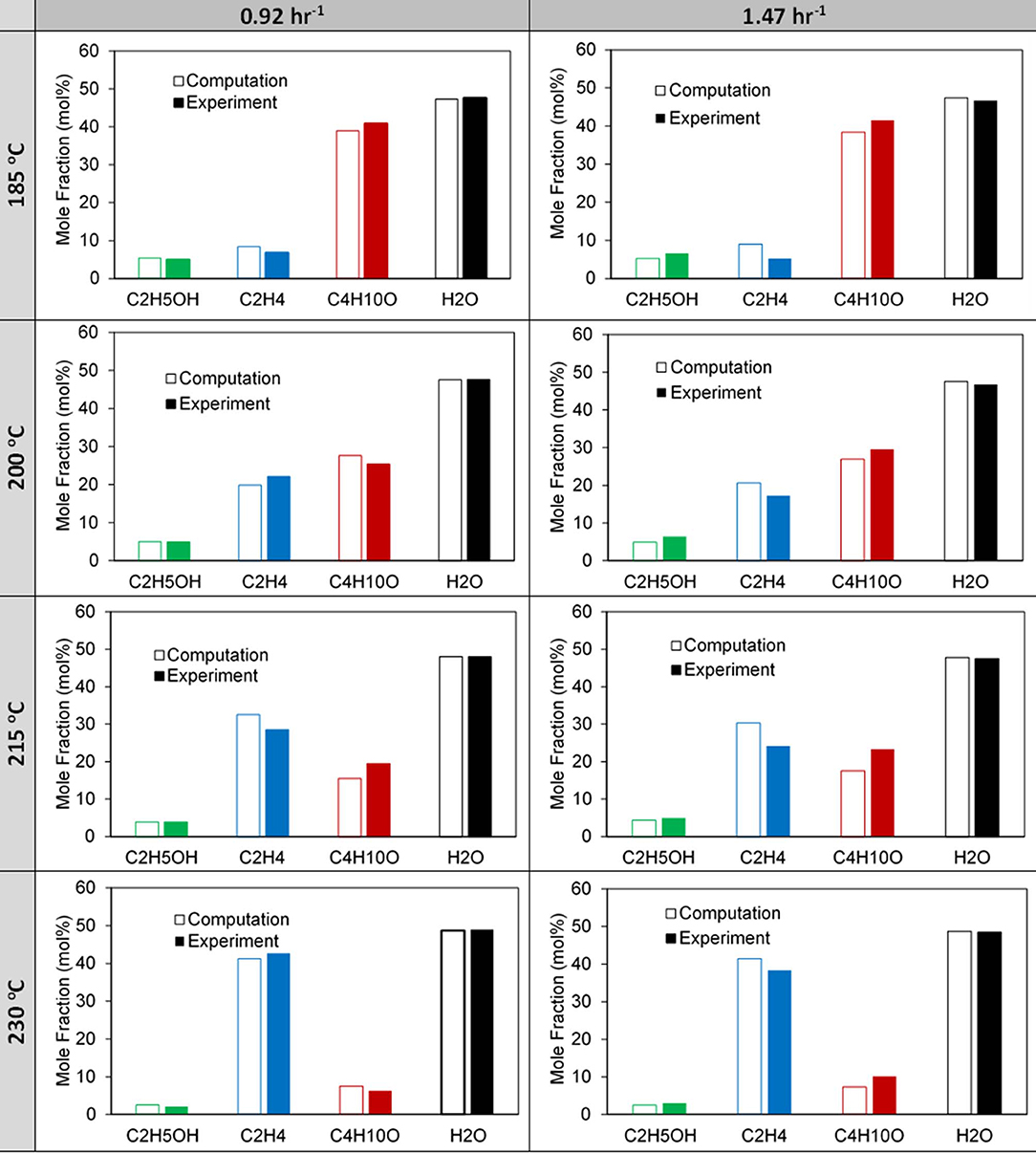

Two-dimensional CFD simulations were performed using a reactive porous model in ANSYS Fluent 17.11. The model set up is described in detail in our previous work (Potter et al., 2018a). We extend this study to the reaction kinetics of the multi-dopant MgSiAlPO-34 experiment, presented in Table 1; focusing on the presence of Mg2+ and formulating additional active sites. Comparing the simulated and experimental mole fractions over a range of temperatures for the 0.92 hr−1 and 1.42 hr−1 WHSV, (Figure 6), shows the simulated results capture the key profiles of the existing products, although some subtle deviations occur at 200 and 215°C. This is likely due to the rate constants at these temperatures deviating more from the linear trend for each of the reactions (Figure S6). As noted previously for the SiAlPO-34 case, it is between these two temperatures that a transition is observed, where ethylene becomes the dominating product, as opposed to diethyl ether. This transition point is consistent for both the 0.92 and 1.47 hr−1 WHSV cases.

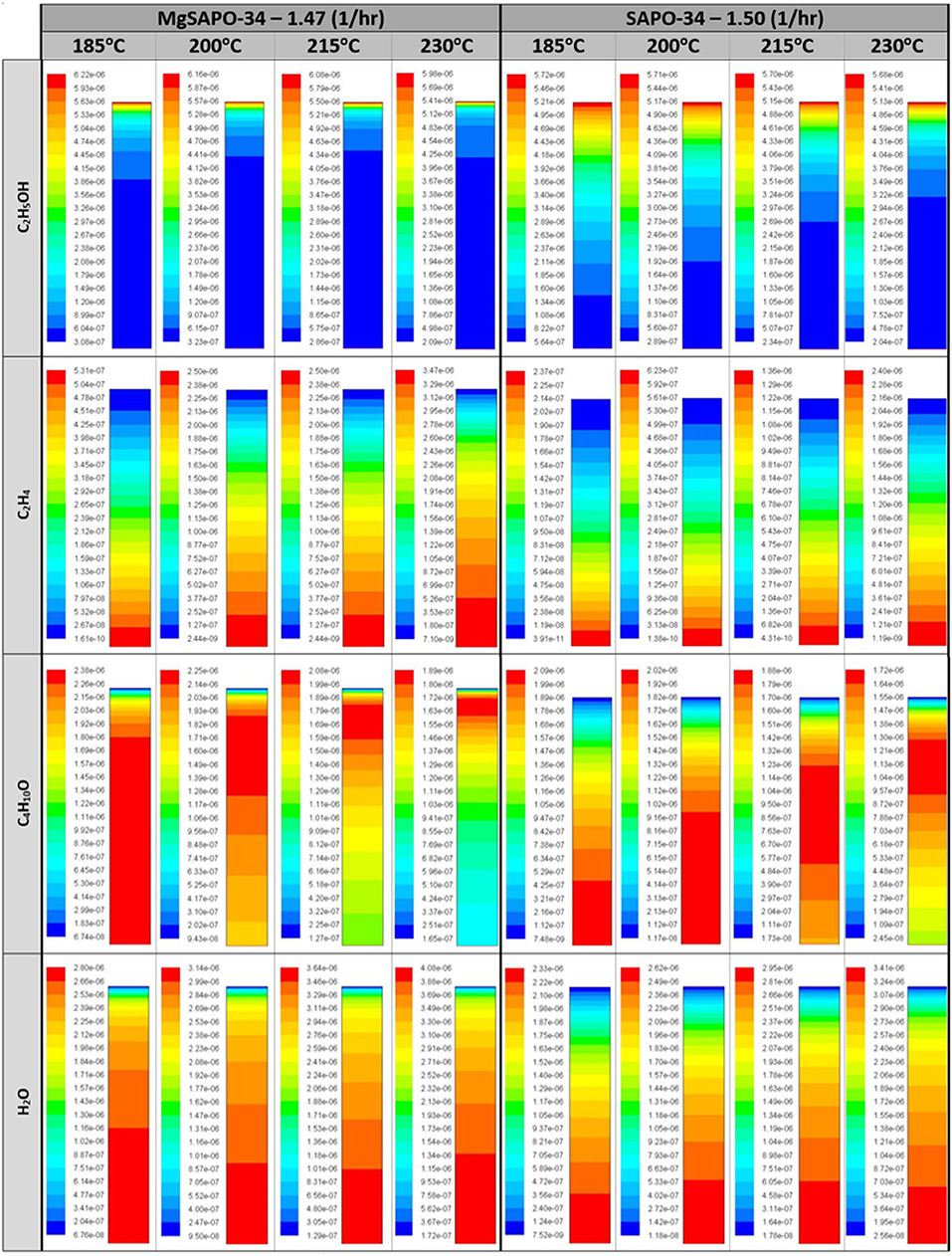

The computationally predicted outlet stream concentrations and mole fractions, from our CFD model, showed excellent agreement with the experimental values (Figure 7 and Table S8) over a range of temperatures and WHSV values. As such we are confident in the models ability to replicate the experimental values, thus validating it. Following this we then observed the spatial variation of the reaction components within the catalytic bed of the reactor, similar to our previous work (Figure 8) (Potter et al., 2018a). Comparing MgSiAlPO-34 and SiAlPO-34 under similar conditions (WHSV of 1.47 and 1.5 hr−1, respectively), further emphasizes the influence of the additional stronger acid sites, present in the multi-dopant catalyst. MgSiAlPO-34 is able to more readily activate ethanol than SiAPO-34, due to the faster decline in ethanol concentration down the catalytic bed, across all temperatures. This is in good agreement with the higher kb values in the MgSiAlPO-34 kinetic analysis (Table 1), and as a result, means diethyl ether reaches a maximum concentration much earlier in the catalytic bed. It is envisaged the presence of the multi-dopant active sites and, possibly their proximal location within the framework architecture, accelerates the overall rate of the reaction, due to the stronger acidity of this modulated catalyst. As the formation of ethylene from diethyl ether is second order, with respect to diethyl ether, then increased diethyl ether concentration will subsequently increase the formation of ethylene in the catalytic reaction. As such, noticeably more ethylene is produced in the reaction, while reaching a maximum value earlier in the bed, compared to the SiAlPO-34 case. The latter observation suggests that the catalytic bed could even be shortened, which on larger scales would result in significant reductions in cost of catalyst, or allow the temperature to be decreased further, offering additional process benefits.

Figure 7. Comparison of computational and experimental exiting mole fractions for the 0.92 and 1.47 h−1 WHSV cases for increasing reactor temperature.

Figure 8. Molar concentration (mol/ml) distribution of species at varying temperatures for the MgSAPO-34 at 1.47 WHSV (hr−1) and the SAPO-34 at 1.5 WHSV (hr−1) with varying reactor height (y-axis), as the chemicals are introduced at the top of the reactor and exit through the bottom.

Conclusion

By utilizing a novel synthesis protocol with tetraethylammonium hydroxide we were able to form phase-pure, crystalline MgSiAlPO-34. Through a range of physicochemical characterization procedures the structural and compositional integrity were evaluated, with solid state NMR suggesting the isomorphous substitution of Mg2+ for Al3+ via type I substitution. Despite structural similarities (with the mono-dopant SiAlPO-34), incorporating both Mg2+ and Si4+ ions simultaneously into the multi-dopant MgSiAlPO-34 chabazite framework, altered the acidic characteristics of the catalytic system. This prompted an increase in both the quantity and relative strength of the Brønsted acid sites, compared to mono-substituted SiAlPO-34. These differences in acidity initially showed that MgSiAlPO-34 was a superior catalyst for ethanol dehydration, producing improved ethylene yields under analogous conditions to SiAlPO-34. Further kinetic and CFD work on the system highlights that this improvement is due to two factors. First the stronger acid sites lower the energy barrier for the formation of the diethyl ether intermediate, thereby increasing the rate of reaction for subsequent ethylene formation. Furthermore, the increased number of solid-acid sites, possibly facilitated through proximal location of the Mg2+ and Si4+ species, facilitates more collisions for the latter step, also leading to greater ethylene yields. In line with these findings, CFD shows diethyl ether reaches a maximum concentration much higher up the catalyst bed in MgSiAlPO-34 than SiAlPO-34, facilitating the improved ethylene yields. Overall this work reinforces the benefits of multi-dopant substitution in framework architectures, which lead to improved product yields, under less energy intensive reaction conditions, furthering the need for unique and novel synthetic methods for such systems.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

MP performed catalyst synthesis, physicochemical characterization, and catalyst testing. L-MA performed the CFD modeling and kinetic analysis. MC performed NMR characterization and data analysis. TM performed TPD and FTIR experiments and data analysis. RR assisted with initial reactor design and associated theories in this paper.

Funding

This work was funded by the EPSRC under the grant: Adventures in Energy, EP/N013883/1; 2016-2018.

Conflict of Interest

TM was employed by the company UOP, A Honeywell company.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2020.00171/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^ANSYS Fluent 17.1, http://www.ansys.com/ (accessed December 2017).

References

Abdulkadir, B. A., Ramli, A., Lim, J. W., and Uemura, Y. (2019). Study on the influence of Mg and catalytic activity of SAPO-34 on biodiesel production from rambutan seed oil. Biofuels 1–7. doi: 10.1080/17597269.2019.1583715

Adams, R. D., Chen, M., Elpitiya, G., Potter, M. E., and Raja, R. (2013). Iridium–bismuth cluster complexes yield bimetallic nano-catalysts for the direct oxidation of 3-picoline to niacin. ACS Catal. 3, 3106–3110. doi: 10.1021/cs400880k

Alonso, D. M., Wettstein, S. G., and Dumesic, J. A. (2012). Bimetallic catalysts for upgrading of biomass to fuels and chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 8075–8098. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35188a

Beale, A. M., Sankar, G., Catlow, C. R. A., Anderson, P. A., and Green, T. L. (2005). Towards an understanding of the oxidation state of cobalt and manganese ions in framework substituted microporous aluminophosphate redox catalysts: an electron paramagnetic resonance and X-ray absorption spectroscopy investigation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 1856–1860. doi: 10.1039/b415570j

Blackwell, C. S., and Patton, R. L. (1988). Solid-state NMR of silicoaluminophosphate molecular sieves and aluminophosphate materials. J. Phys. Chem. 92, 3965–3970. doi: 10.1021/j100324a055

Bordiga, S., Regli, L., Lamberti, C., Zecchina, A., Jorgen, M., and Lillerud, K. P. (2005). FTIR adsorption studies of H2O and CH3OH in the isostructural H-SSZ-13 and H-SAPO-34: formation of H-bonded adducts and protonated clusters. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 7724–7732. doi: 10.1021/jp044324b

Buchholz, A., Wang, W., Arnold, A., Xu, M., and Hunger, M. (2003). Successive steps of hydration and dehydration of silicoaluminophosphates H-SAPO-34 and H-SAPO-37 investigated by in situ CF MAS NMR spectroscopy. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 57, 157–168. doi: 10.1016/S1387-1811(02)00562-0

Bui, L., Luo, H., Gunther, W. R., and Román-Leshkov, Y. (2013). Domino reaction catalyzed by zeolites with brønsted and lewis acid sites for the production of γ-valerolactone from furfural. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 8022–8025. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302575

Corà, F., Alfredsson, M., Barker, C. M., Bell, R. G., Foster, M. D., Saadoune, I., et al. (2003). Modeling the framework stability and catalytic activity of pure and transition metal-doped zeotypes. J. Solid State Chem. 176, 492–529. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4596(03)00275-5

Dai, W., Wu, G., Li, L., Guan, N., and Hunger, M. (2013). Mechanisms of the deactivation of SAPO-34 materials with different crystal sizes applied as MTO catalysts. ACS Catal. 3, 588–596. doi: 10.1021/cs400007v

De, S., Zhang, J., Luque, R., and Yan, N. (2016). Ni-based bimetallic heterogeneous catalysts for energy and environmental applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 3314–3337. doi: 10.1039/C6EE02002J

Deng, F., Yue, Y., Xiao, T. C., Du, Y. U., Ye, C. H., An, L. D., et al. (1995). Substitution of aluminum in aluminophosphate molecular sieve by magnesium: a combined NMR and XRD study. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 6029–6035. doi: 10.1021/j100016a045

Frache, A., Gianotti, E., and Marchese, L. (2003). Spectroscopic characterisation of microporous aluminophosphate materials with potential application in environmental catalysis. Catal. Today 77, 371–384. doi: 10.1016/S0920-5861(02)00381-4

Gianotti, E., Manzoli, M., Potter, M. E., Shetti, V. N., Sun, D., Paterson, J., et al. (2014). Rationalising the role of solid-acid sites in the design of versatile single-site heterogeneous catalysts for targeted acid-catalysed transformations. Chem. Sci. 5, 1810–1819. doi: 10.1039/C3SC53088D

Hermans, S., Raja, R., Thomas, J. M., Johnson, B. F. G., Sankar, G., and Gleeson, D. (2001). Solvent-free, low-temperature, selective hydrogenation of polyenes using a bimetallic nanoparticle Ru–Sn catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 1211–1215. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010401)40:7<1211::AID-ANIE1211>3.0.CO;2-P

Hira, A., and Guilherme de Oliveira, L. (2009). No substitute for oil? How Brazil developed its ethanol industry. Energy Policy 37, 2450–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.02.037

Hopps, S., Sahle, S., Gauges, R., Lee, C., Pahle, J., Simus, N., et al. (2006). COPASI—a complex pathway simulator. Bioinformatics 22, 3067–3074. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl485

Hungria, A. B., Raja, R., Adams, R. D., Captain, B., Thomas, J. M., Midgley, P. A., et al. (2006). Single-step conversion of dimethyl terephthalate into cyclohexanedimethanol with Ru5PtSn, a trimetallic nanoparticle catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 4782–4785. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600359

Huo, C. F., Wu, B. S., Gao, P., Yang, Y., Li, Y. W., and Liao, H. (2011). The mechanism of potassium promoter: enhancing the stability of active surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7403–7406. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007484

Jiang, Z., Shen, B. X., Zhao, J. G., Wang, L., Kong, L. T., and Xiao, W. G. (2015). Enhancement of catalytic performances for the conversion of chloromethane to light olefins over SAPO-34 by modification with metal chloride. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 12293–12302. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b03586

Kadam, S. A., and Shamzhy, M. V. (2018). IR operando study of ethanol dehydration over MFI zeolite. Catal. Today 304, 51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2017.09.020

Leithall, R. M., Shetti, V. N., Maurelli, S., Chiesa, M., Gianotti, E., and Raja, R. (2013). Toward understanding the catalytic synergy in the design of bimetallic molecular sieves for selective aerobic oxidations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2915–2918. doi: 10.1021/ja3119064

Li, X., Rezaei, F., Ludlow, D. K., and Rownaghi, A. A. (2018). Synthesis of SAPO-34@ZSM-5 and SAPO-34@Silicalite-1 core–shell zeolite composites for ethanol dehydration. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 1446–1453. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b05075

Li, Y., Cao, H., and Yu, J. (2018). Toward a new era of designed synthesis of nanoporous zeolitic materials. ACS Nano 12, 4096–4104. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02625

Martins, G. A. V., Berlier, G., Coluccia, S., Pastore, H. O., Superti, G. B., Gatti, G., et al. (2007). Revisiting the nature of the acidity in chabazite-related silicoaluminophosphates: combined FTIR and 29Si MAS NMR study. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 330–339. doi: 10.1021/jp063921q

Masih, D., Rohani, S., Kondo, J. N., and Tatsumi, T. (2019). Catalytic dehydration of ethanol-to-ethylene over Rho zeolite under mild reaction conditions. Micropor. Mespor. Mater. 282, 91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.01.035

Mortén, M., Mentel, L., Lazzarini, A., Pankin, I. A., Lamberti, C., Bordiga, S., et al. (2018). A systematic study of isomorphically substituted H-MAlPO-5 materials for the methanol-to-hydrocarbons reaction. Chemphyschem 19, 484–495. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201701024

Munnik, P., de Jongh, P. E., and de Jong, K. P. (2015). Recent developments in the synthesis of supported catalysts. Chem. Rev. 115, 6687–6718. doi: 10.1021/cr500486u

Pastore, H. O., Coluccia, S., and Marchese, L. (2005). Porous aluminophosphates: from molecular sieves to designed acid catalysts. Ann. Rev. Mater. Res. 35, 351–395. doi: 10.1146/annurev.matsci.35.103103.120732

Paterson, J., Potter, M. E., Gianotti, E., and Raja, R. (2011). Engineering active sites for enhancing synergy in heterogeneous catalytic oxidations. Chem. Commun. 47, 517–519. doi: 10.1039/C0CC02341H

Phung, T. K., Hernández, L. P., Lagazzo, A., and Busca, G. (2015). Dehydration of ethanol over zeolites, silica alumina and alumina: Lewis acidity, Brønsted acidity and confinement effects. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 493, 77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.12.047

Potter, M. E., Armstrong, L.-M., and Raja, R. (2018a). Combining catalysis and computational fluid dynamics towards improved process design for ethanol dehydration. Catal. Sci. Technol. 8, 6163–6172. doi: 10.1039/C8CY01564C

Potter, M. E., Chapman, S., O'Malley, A. J., Levy, A., Carravetta, M., Mezza, T. M., et al. (2017). Understanding the role of designed solid acid sites in the low-temperature production of ϵ-caprolactam. ChemCatChem 9, 1897–1900. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201700516

Potter, M. E., Cholerton, M. E., Kezina, J., Bounds, R., Carravetta, M., Manzoli, M., et al. (2014). Role of isolated acid sites and influence of pore diameter in the low-temperature dehydration of ethanol. ACS Catal. 4, 4161–4169. doi: 10.1021/cs501092b

Potter, M. E., Kezina, J., Bounds, R., Carravetta, M., Mezza, T. M., and Raja, R. (2018b). Investigating the role of framework topology and accessible active sites in silico aluminophosphates for modulating acid-catalysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 8, 5155–5164. doi: 10.1039/C8CY01370E

Potter, M. E., Paterson, A. J., Mishra, B., Kelly, S. D., Bare, R. R., Corà, F., et al. (2015). Spectroscopic and computational insights on catalytic synergy in bimetallic aluminophosphate catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8534–8540. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03734

Potter, M. E., Sun, D., Gianotti, E., Manzoli, M., and Raja, R. (2013). Investigating site-specific interactions and probing their role in modifying the acid-strength in framework architectures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 13288–13295. doi: 10.1039/c3cp51182k

Price, S. W. T., Speed, J. D., Kannan, P., and Russell, A. E. (2011). Exploring the first steps in core–shell electrocatalyst preparation: in situ characterization of the underpotential deposition of Cu on supported Au nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19448–19458. doi: 10.1021/ja206763e

Raja, R., Khimyak, T., Thomas, J. M., Hermans, S., and Johnson, B. F. G. (2001). Single-step, highly active, and highly selective nanoparticle catalysts for the hydrogenation of key organic compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 4638–4642. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4638::AID-ANIE4638>3.0.CO;2-W

Rogers, S. M., Catlow, C. R. A., Chan-Thaw, C. E., Chutia, A., Jian, N., Palmer, R. E., et al. (2017). Tailoring gold nanoparticle characteristics and the impact on aqueous-phase oxidation of glycerol. ACS Catal. 4, 2266–2274. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.6b03190

Saadoune, I., Corà, F., and Catlow, C. R. A. (2003). Computational study of the structural and electronic properties of dopant ions in microporous AlPOs. 1. Acid catalytic activity of divalent metal ions. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 3003–3011. doi: 10.1021/jp027285h

Salmasi, M., Fatemi, S., and Najafabadi, A. T. (2011). Improvement of light olefins selectivity and catalyst lifetime in MTO reaction; using Ni and Mg-modified SAPO-34 synthesized by combination of two templates. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 17, 755–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2011.05.031

Smith, L., Cheetham, A. K., Marchese, L., Thomas, J. M., Wright, P. A., Chen, J., et al. (1996). A quantitative description of the active sites in the dehydrated acid catalyst HSAPO-34 for the conversion of methanol to olefins. Catal. Lett. 41, 13–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00811705

Sun, Q., Wang, N., Xi, D., Yang, M., and Yu, J. (2014). Organosilane surfactant-directed synthesis of hierarchical porous SAPO-34 catalysts with excellent MTO performance. Chem. Commun. 50, 6502–6505. doi: 10.1039/c4cc02050b

Thomas, J. M., and Raja, R. (2005). Design of a “green” one-step catalytic production of ε-caprolactam (precursor of nylon-6). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13732–13736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506907102

Thomas, J. M., Raja, R., and Lewis, D. W. (2005). Single-site heterogeneous catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 6456–6482. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462473

Villa, A., Wang, D., Su, D. S., and Prati, L. (2015). New challenges in gold catalysis: bimetallic systems. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5, 55–68. doi: 10.1039/C4CY00976B

Wang, Y., Chen, S. L., Gao, Y. L., Cao, Y. Q., Zheng, Q., Chang, W. K., et al. (2017). Enhanced methanol to olefin catalysis by physical mixtures of SAPO-34 molecular sieve and MgO. ACS Catal. 7, 5572–5584. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b01285

Wragg, D. S., O'Brien, M. G., Bleken, F. L., di Michiel, M., Olsbye, U., and Fjellvåg, H. (2012). Watching the methanol-to-olefin process with time- and space-resolved high-energy operando x-ray diffraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7956–7959. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203462

Xiao, Y., and Varma, A. (2018). Highly selective nonoxidative coupling of methane over Pt-Bi bimetallic catalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 2735–2740. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b00156

Zeidan, R. K., Hwang, S. J., and Davis, M. E. (2006). Multifunctional heterogeneous catalysts: SBA-15-containing primary amines and sulfonic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 6332–6335. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602243

Zhang, D., Wei, Y., Xu, L., Chang, F., Liu, Z., Meng, S., et al. (2008). MgAPSO-34 molecular sieves with various Mg stoichiometries: synthesis, characterization and catalytic behavior in the direct transformation of chloromethane into light olefins. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 116, 684–692. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2008.06.001

Keywords: catalysis, zeotypes, solid-acid, ethanol, CFD

Citation: Potter ME, Armstrong L-M, Carravetta M, Mezza TM and Raja R (2020) Designing Multi-Dopant Species in Microporous Architectures to Probe Reaction Pathways in Solid-Acid Catalysis. Front. Chem. 8:171. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00171

Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 25 February 2020;

Published: 17 March 2020.

Edited by:

Shinya Maenosono, Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, JapanReviewed by:

Honghong Shi, University of Kansas, United StatesTugce Ayvali, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Potter, Armstrong, Carravetta, Mezza and Raja. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew E. Potter, bS5lLnBvdHRlckBzb3Rvbi5hYy51aw==; Lindsay-Marie Armstrong, bC5hcm1zdHJvbmdAc290b24uYWMudWs=

Matthew E. Potter

Matthew E. Potter Lindsay-Marie Armstrong

Lindsay-Marie Armstrong Marina Carravetta1

Marina Carravetta1 Thomas M. Mezza

Thomas M. Mezza Robert Raja

Robert Raja