- 1Department of Biomedical Sciences, Creighton University, Omaha, NE, United States

- 2Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN, United States

- 3Department of Translational Neuroscience, College of Medicine, University of Arizona, Pheonix, AZ, United States

- 4Molecular Otolaryngology and Renal Research Laboratories, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States

- 5School of Biomedical Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 6Department of Neurological Sciences, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, United States

The transcription factor Lmx1a is widely expressed during early inner ear development, and mice lacking Lmx1a expression exhibit fusion of cochlear and vestibular hair cells and fail to form the ductus reuniens and the endolymphatic sac. Lmx1a dreher (Lmx1adr/dr), a recessive null mutation, results in non-functional Lmx1a expression, which expands from the outer sulcus to the stria vascularis and Reissner’s membrane. In the absence of Lmx1a, we observe a lack of proteins specific to the stria vascularis, such as BSND and KCNQ1 in marginal cells and CD44 in intermediate cells. Further analysis of the superficial epithelial cell layer at the expected stria vascularis location shows that the future intermediate cells migrate during embryonic development but subsequently disappear. Using antibodies against pendrin (Slc26a4) in Lmx1a knockout (KO) mice, we observe an expansion of pendrin expression across the stria vascularis and Reissner’s membrane. Moreover, in the absence of Lmx1a expression, no endocochlear potential is observed. These findings highlight the critical role of Lmx1a in inner ear development, particularly in the differentiation of cochlear and vestibular structures, the recruitment of pigment cells, and the expression of proteins essential for hearing and balance.

Introduction

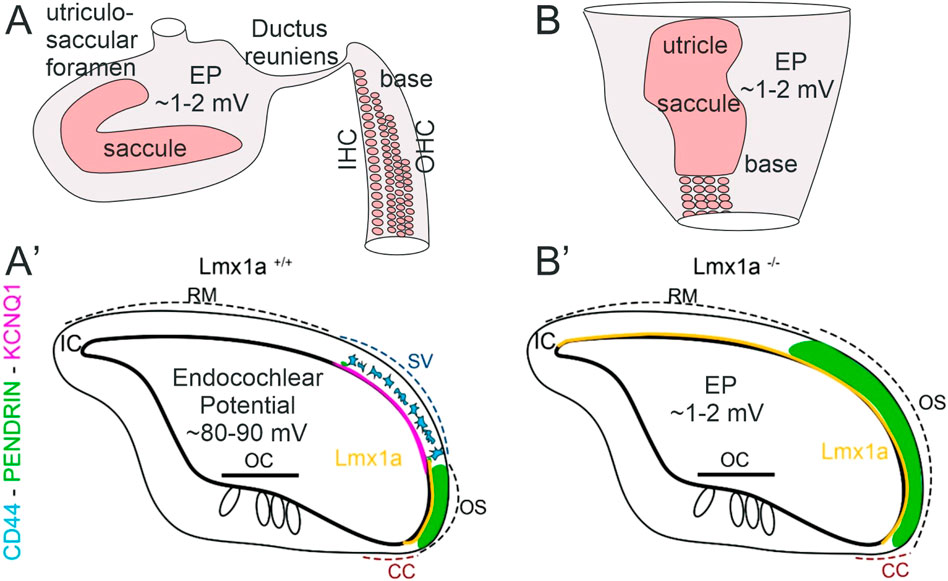

In mammals, a hearing (cochlea) and balance system (three semicircular canals, utricle, and saccule) are separated by the ductus reuniens that provides a connection between the cochlear basal tip with the saccule (Kopecky et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2024). The stria vascularis provides high potassium in the cochlea to generate an endocochlear potential of ∼80–100 mV (Köppl and Manley, 2018; Strepay et al., 2024; Wangemann, 2006), whereas the vestibular system does not show an elevated potential of ∼1–2 mV (Hibino et al., 2010; Wangemann, 1995). A typical formation of the stria vascularis (Bovee et al., 2024; Thulasiram et al., 2024) is essential to separate the ductus reuniens from the saccule (∼1 mV) with the basal turn of the cochlea (∼80 mV). Moreover, the narrow ductus reuniens of 0.14 mm might be blocked, resulting in Meniere’s disease (Hornibrook et al., 2021). In contrast to the narrow ductus reuniens, only three mutants have been described that fuse the basal tip with the saccule that eliminates the ductus reuniens: Lmx1a (knock out) KO, n-Myc KO, and Irx3/5 (double knock out) DKO (Fritzsch et al., 2024; Kopecky et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2008). An incomplete fusion of utricle and saccule is shared between Otx1 KO mice and Lmx1a KO (Fritzsch et al., 2001; Nichols et al., 2008). One mutant survives beyond birth to study the function of the cochlear system and the stria vascularis in the absence of a ductus reunion: Lmx1a KO mice (Supplementary Figure S1).

Lmx1a, like Lmx1b, is one of the LIM-homeodomain transcription factors expressed in the inner ear (Chizhikov et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2008). Previous work have shown that an A-to-T transversion in exon 2 results in an aspartate-to-valine substitution at amino acid 44, which effectively creates null alleles for Lmx1a, including the dreher mutation (Chizhikov et al., 2006). Several human mutations in LMX1A have been associated with hearing loss, but the exact cellular mechanisms of deafness are unclear (Lee et al., 2020; Schrauwen et al., 2018; Wesdorp et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2023). Previous research in mice showed that Lmx1a expression participates in mechanisms that maintain separation between the posterior crista and basal cochlear sensory epithelium (Koo et al., 2009; Nichols et al., 2008; Steffes et al., 2012). Moreover, others showed that the absence of Lmx1a led to the ablation of the endolymphatic sac (Nichols et al., 2008; Roux et al., 2023). The continuation of the basal turn blends with the saccule and the utricle, abolishing the ductus reuniens and the utriculosaccular foramen. During the early development of the inner ear (E8.5) and until embryonic day E16.5, Lmx1a remains broadly expressed in the otic non-sensory epithelium (Failli et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2008; Koo et al., 2009; Nichols et al., 2020; Nichols et al., 2008; Steffes et al., 2012). This includes the epithelium that will form the Reissner’s membrane, the marginal cell layer of the stria vascularis, and the outer spiral sulcus (Jean et al., 2023; Qin et al., 2024; Renauld et al., 2021). After E18.5, Lmx1a expression withdraws from Reissner’s membrane and the marginal cell layer but persists in the outer sulcus (Huang et al., 2008; Koo et al., 2009; Nichols et al., 2008).

The stria vascularis, located lateral to the organ of Corti and between the outer sulcus and Reissner’s membrane, is a complex epithelium. The stria vascularis is responsible for the specialized ionic environment in the endolymph and the positive endocochlear potential that is indispensable for hearing sensitivity (Koh et al., 2023; Strepay et al., 2024). Morphologically, the stria vascularis is formed by three main cell layers, namely, the marginal, intermediate, and basal cells. Each cell layer arises from a distinct embryonic origin, with the marginal cells originating from the otic vesicle, the intermediate cells from the neural crest cells, and the basal cells from the otic mesenchyme (Bovee et al., 2024; Renauld et al., 2022; Rose et al., 2023; Sagara et al., 1995; Steel and Barkway, 1989; Trowe et al., 2011). Although the stria vascularis is typically classified as an epithelium, it is unusual as it lacks a basal lamina underneath the basal cell layer. During development, the basal lamina beneath the marginal cells is degraded around birth to allow the interdigitation between marginal and intermediate cells (Kikuchi and Hilding, 1966; Sagara et al., 1995). Furthermore, the abundant blood capillaries in the stria vascularis possess their basilar membrane (Kikuchi and Hilding, 1966). Additionally, the stria vascularis is distinct in having tight junctions that seal both its luminal (marginal cell layer) and abluminal (basal cell layer) surfaces (Kikuchi and Hilding, 1966; Koh et al., 2023; Steel and Barkway, 1989). This tight junctional seal, which separates the stria vascularis from the rest of the inner ear, confers a highly resistive pathway essential for generating endocochlear potential for hearing (Diaz et al., 2007; Gow et al., 2004; Kitajiri et al., 2004; Koh et al., 2023; Nin et al., 2008; Qin et al., 2024; Roux et al., 2023; Souter and Forge, 1998; Wang et al., 2009; Wangemann, 2006).

Adjacent to the stria vascularis, other cells play a crucial role in maintaining inner ear fluid homeostasis. A mutation in a gene affecting the gap junctional system, essential for K+ recycling across the stria vascularis, results in profound hearing losses (Chan and Chang, 2014; Mei et al., 2017; Szeto et al., 2022). A recent analysis of the pendrin null mutation (Slc26a4−/−) revealed that in the cochlea, pendrin is needed for the development of the spindle cells and the spiral ligament contains extrinsic cellular components that enable cell-to-cell communication (Koh et al., 2023). Without pendrin expression, pH regulation is altered, leading to the absence of endolymphatic potential (Kim and Wangemann, 2011; Koh et al., 2023). In addition, the loss of SOX9 and SOX10 genes reduces Slc26a4 expression, resulting in endolymphatic dysregulation and hydrops (Szeto et al., 2022).

Despite its essential role in hearing, generating the endocochlear potential, promoting K+ recycling, and the numerous human deafness mutations resulting from the genes expressed in the stria vascularis, little is known about its molecular developmental mechanisms (Pingault et al., 2010; Ritter and Martin, 2019; Thulasiram et al., 2024). During inner ear development, the cochlea’s roof epithelium, which expresses OC90 can be divided into two populations as early as E13.5 (Hartman et al., 2015; Qin et al., 2024). One cell population is Wnt4-positive, which gives rise to Reissner’s membrane, and the second population is GSC-positive, representing the future marginal cell layer (Qin et al., 2024). Recent findings have shown that the absence of Esrp1, an RNA binding protein, expands the expression of Otx2, potentially through FgF9/FgFr2-IIIc signaling, leading to the replacement of the stria vascularis by Reissner’s membrane (Rohacek et al., 2017).

In this study, we show that Lmx1a is essential for the development of the marginal cells, and its absence leads to an expansion of pendrin-expressing cells and the replacement of the stria vascularis by the outer sulcus and spiral prominence, which contains the spindle cells. We also showed that Lmx1a is essential for the stria vascularis epithelium development and migrating melanoblasts’ recruitment to integrate the intermediate cell layer of the stria vascularis. The results showed that in the absence of Lmx1a, the endocochlear potential is abolished, explaining the previously published profound deafness in the Lmx1a null mutant (Steffes et al., 2012).

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

We bred Lmx1a heterozygotes [Lmx1a drJ, Jackson Laboratory strain #000636 (Chizhikov et al., 2006)] to generate null, heterozygote, and control mice [Lmx1a+/+ (WT), Lmx1adr/+ (Het), and Lmx1adr/dr (KO)]. According to JAX, a total of 26 mutations of Lmx1a are known, with more details available for 16 spontaneous mutations (https://www.informatics.jax.org/marker/MGI:1888519). Eight spontaneous mutations are among those associated with hearing and vestibular defects. We know that a transversion in exon 2 resulted in an aspartate-to-valine substitution, effectively creating null alleles for Lmx1a (Chizhikov et al., 2006). Mice were collected at E12.5, E13.5, E15.5, E18.5, P2, P8, P10, P14, and P21; genotyped; and fixed in 4% PFA in 0.1 M P04 with 300 mM sucrose. Fixation was reduced to 0.4% PFA in 0.1 M PO4 with 300 mM sucrose before shipping the fixed mice to UNMC for processing. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center [IACUC #15-057 and 18-037] and Creighton University (IACUC #10-35).

Histology on whole mounts

Animals were dissected to isolate the inner ear of control and Lmx1a KO mice. Frozen cochlear whole mounts were blocked and permeabilized with a 30% normal goat serum solution and 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight in 1% normal goat serum solution and 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1X PBS. Cochlear and vestibular samples were immunostained with anti-pendrin (1:100, #2842). Alexa Fluor 488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat#A-21202, RRID: AB-141607) was used as a secondary antibody at a 1:1,000 concentration for 12 h at room temperature (Koh et al., 2023). DAPI (Life Technologies) was used to highlight the expression of all cell nuclei. We also used a recently developed antibody against pendrin [Supplementary Figure S2 (Roux et al., 2023)].

Antibodies were applied to whole mounts flattened after Reissner’s membrane was cut open. In addition, sections were taken at 50-µm thickness using a vibratome, allowing for detailed expression of DAPI and pendrin. Images were captured using a Zeiss 700 microscope at 10x (0.45 NA), 20x (0.8 NA), and 40x (1.3 NA) magnification. Imaging was processed using Zen 3.8 to generate z-stacks and single images.

Dye tracing

Dye tracing was performed by inserting dye into the brainstem to label afferents leading to the cochlea, as described by Elliott et al. (2023) and Nichols et al. (2008).

Histology on cryosection

Samples were rinsed with PBS thrice, then placed in 30% sucrose overnight, and embedded in OCT. Sections were performed at −20°C with a 12 µm thickness on a cryostat (Leica). Slides were dried at room temperature, then rinsed with PBS, and permeabilized with Triton X-100 1% for 10 min, followed by blocking in 10% donkey serum for 30 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies diluted in 5% serum/PBS were placed on the slides overnight at 4°C [BSND (Rabbit AB196017-1001; 1/100); CD44 (Rat MA4405; 1/250); KCNQ1 (Guinea-pig APC-022-GP; 1/200) anti-pendrin (1:100, #2842) (Renauld et al., 2021; Renauld et al., 2022)]. The primary antibodies were washed three times, with each washing lasting 5 min, in PBS, and the secondary antibodies were placed at room temperature for 1 h (Alexa anti-rabbit 488; Alexa anti-guinea-pig 488 and Alexa anti-rat 555). Phalloidin-635 (A34054; 1/1,000) was used in conjunction with the secondary antibodies. Images were taken using a Zeiss 700 confocal imaging microscope at 10x (0.45 NA), 20x (0.8 NA), and 40x (1.3 NA) magnification. Imaging was processed using Zen 3.8 to generate z-stacks and single images.

In situ hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridizations were carried out according to the standard procedures (Pauley et al., 2003) using previously characterized digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes for dopachrome tautomerase (Dct) (Steel et al., 1992) and Tbx18 (Trowe et al., 2011; Trowe et al., 2008). Anti-digoxigenin-AP antibody and BM Purple (Roche) were used for colorimetric signal detection. Stained tissue was embedded in soft epoxy resin, sectioned, and documented as described above. Minimizing exposure to 100% EtOH and propylene oxide during embedding is critical for preserving this stain. Hybridizations omitting probes yielded a uniformly pale background stain. Where two ears are described as being simultaneously stained, all steps in the staining procedure were conducted in the same reaction vial. Identical camera settings were used to image different samples.

Endocochlear potential measurements

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (16.6 mg/mL) and xylazine (2.3 mg/mL) and supplemented as needed to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia. The core temperature was maintained at 38°C with a heating pad. An incision was made in the inferior portion of the right postauricular sulcus. The bulla was perforated, allowing for exposure of the stapedial artery and the cochlea’s basal and upper turns. A hole was made in the wall of the cochlea near the basal turn using a fine drill. A glass capillary pipette electrode (10–20 MΩ) filled with 150 mM KCl was mounted on a hydraulic micromanipulator and advanced until a stable potential was observed that did not change with increased electrode depth. The ground electrode was implanted in the dorsal neck muscles. The biological signals (filtered at 1 kHz) were amplified under current-clamp mode using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Probe, Sunnyvale, CA) and acquired using pCLAMP 9.1 software (Molecular Probe) and Digidata 1322B. The voltage changes during entry into the endolymph were continuously recorded under the gap-free model using Clampex in the pCLAMP software package (version 9.2, Molecular Probe). The sampling frequency was 10 kHz. Data were analyzed using Clampfit and Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Portland, OR). Six animals from each age/genotype were used.

Results

Lmx1a is required for the differentiation of the marginal cells and the formation of the stria vascularis

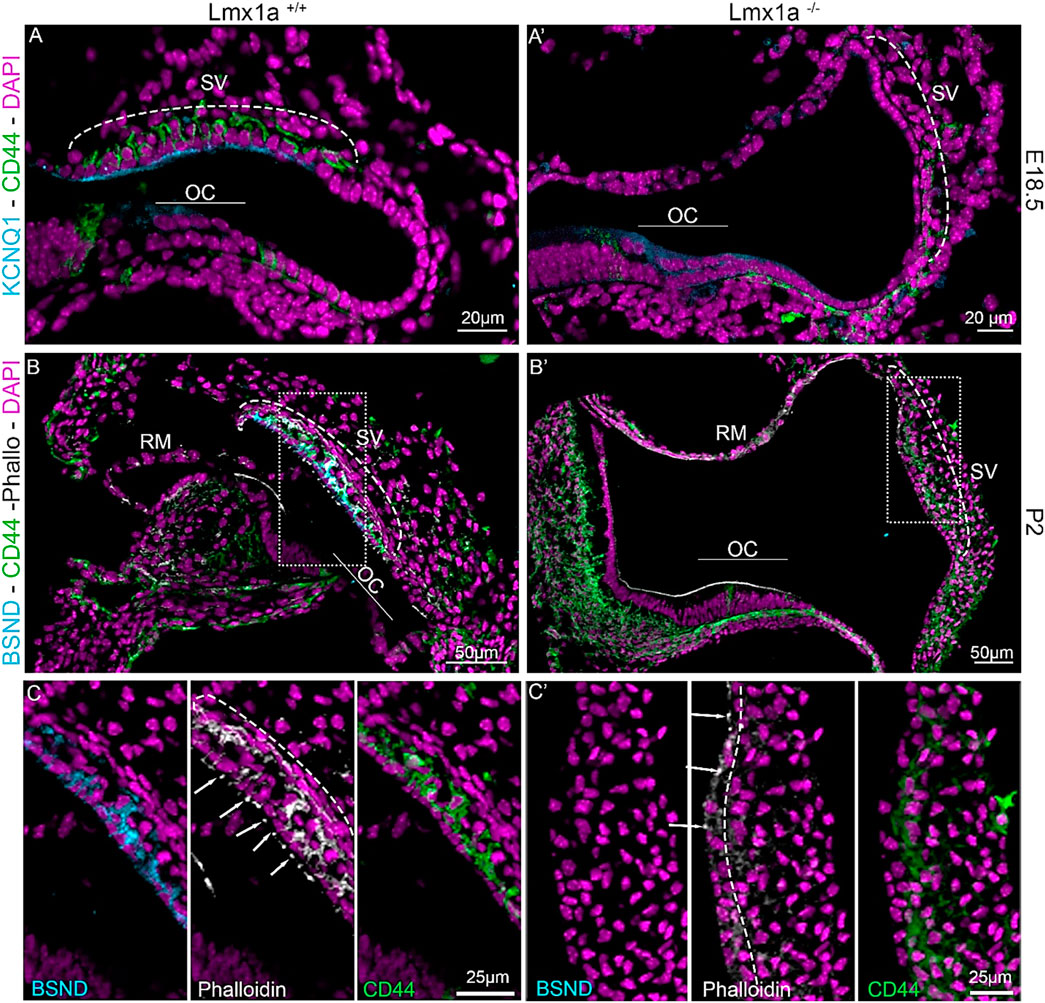

Previous publications have shown the expression of Lmx1a during cochlea development. Lmx1a is expressed as early as E8.5, and by E10.5, it is expressed in almost the entire otocyst. After initial expression, Lmx1a becomes more absorbed in the endolymphatic sac, which is absent in E18.5-old mice, and the lateral side of the cochlear duct (Mann et al., 2017; Nichols et al., 2020; Nichols et al., 2008). To understand the role of Lmx1a in the lateral wall formation, we analyzed the cochlear ducts of Lmx1a WT and KO at E18.5 and P2 through histological sections (Figure 1). To recognize the different cell layers of the stria vascularis, we used well-known markers such as BSND (barttin) and KCNQ1 (potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1) for the marginal cell layer and CD44, a cell surface adhesion receptor for the intermediate cell layer (Morris et al., 2006; Rickheit et al., 2008; Rohacek et al., 2017; Sakagami et al., 1991). KCNQ1, a channel protein essential for extruding K+ into the endolymph and ordinarily present at the luminal surface of the marginal cells, is absent in Lmx1a−/− mice (Figures 1A, A′). In Lmx1a+/+ mice, BSND labels the marginal cells and CD44 labels the intermediate cell layer. Phalloidin allows the delineation of the stria vascularis, which is rich in actin (Figures 1B, B′). In Lmx1a−/− mice, BSND expression is absent, and phalloidin labeling highlights a superficial epithelial layer in opposition to the three layers present in the WT (Figures 1C, C′, middle panel). The absence of landmark proteins in the marginal and intermediate cells of the stria vascularis, along with the morphology of single-cell epithelium, shows that the cellular architecture of the stria vascularis is severely compromised in Lmx1a−/− KO mice (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1. Lmx1a−/− mutant cochlea does not express marginal cell markers and fails to develop a proper stria vascularis. Immunostaining of E18.5 and P2 Lmx1a+/+ (A–C) and Lmx1a −/− (A′–C′) cochlea with the white dashed rectangle magnified in inserts. Future intermediate cells labeled with CD44 (green) are on top of the cochlear duct and ingress in the lateral wall between the marginal cells labeled with Kcnq1 (cyan) in the WT cochlea (A). In the Lmx1a−/− cochlea, at E18.5, CD44-positive cells are visible above the lateral wall but do not ingress as the marginal cell layer is absent (A′). At P2, Lmx1a+/+ cochlea showed a multilayered stria vascularis, where the first layer is labeled with BSND (cyan), another marker for marginal cells, CD44 for intermediate cells (green), and Phalloidin (white), which highlights the actin-based tight junction closing the marginal layer (arrows) and the basal layer (dashed line) of the stria vascularis (B). In Lmx1a−/−, the stria vascularis cannot be recognized without BSND labeling (cyan) and phalloidin staining on the basal side of the stria (dashed line (C′) insert). Some CD44-positive cells are still present but do not create the intermediate cell layer (B′, C′). OC, organ of Corti; SV, stria vascularis; RM, Reissner’s membrane.

Intermediate cells’ melanoblasts migrate during development but fail to integrate into the stria vascularis without Lmx1a

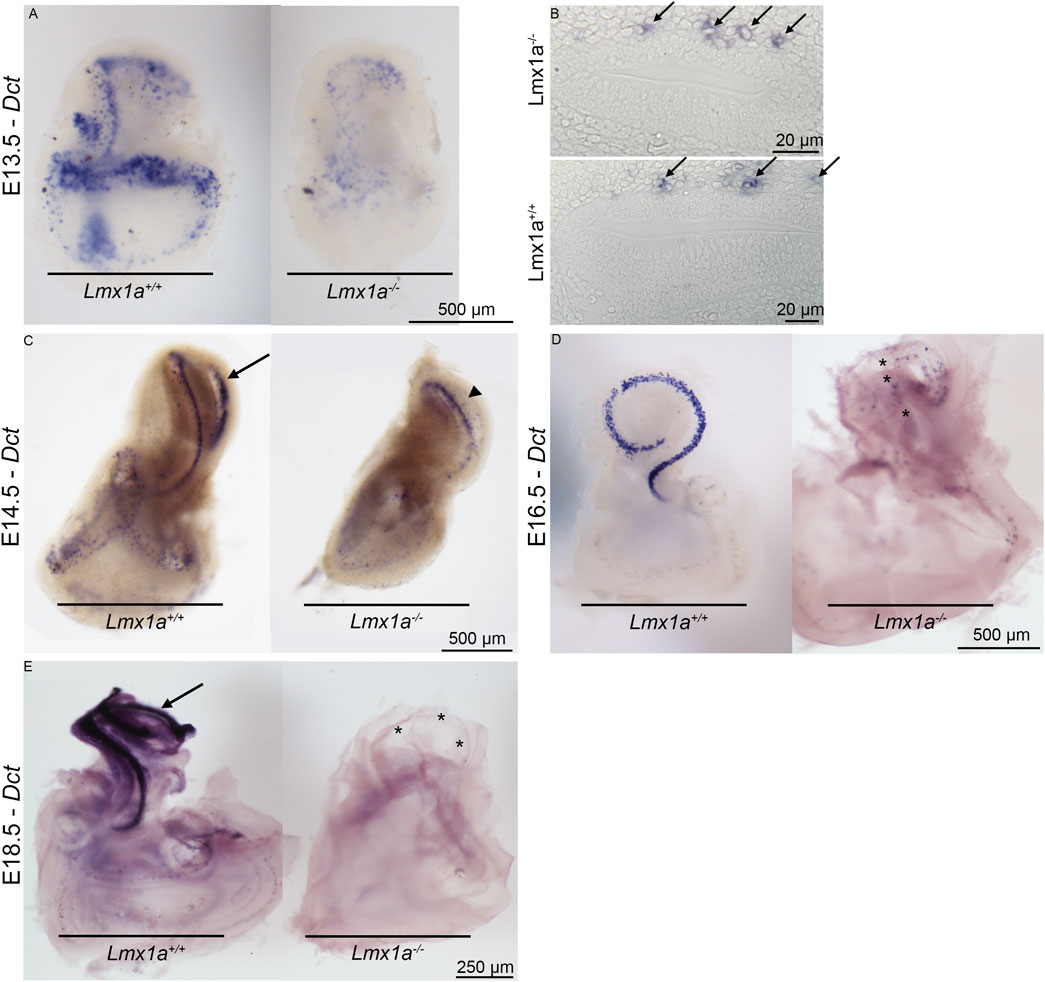

During the development of the inner ear, neural crest cells that give rise to the intermediate cell layer can be observed lining up above the roof of the cochlear duct as early as E12.5 (Renauld et al., 2022). At E15.5, the melanoblast cells start to ingress into the single-cell layer that starts differentiating into marginal cells. In the absence of Lmx1a, we observe the migration of melanoblasts along the membranous labyrinth from the base to the apex of the cochlear coil (E14.5 in Figures 2A–C), but 2 days later (E16.5), Dct (a melanoblast marker)-positive cells are sparse (Figure 2D, asterisk) and lost by E18.5 (Figure 2E), probably due to the absence of either intrinsic factors or signaling factors required by marginal cells in the epithelial layer of the stria vascularis. On the transverse section at E13.5, the Dct-positive cells are visible above the cochlear roof epithelium in the Lmx1a WT and KO mice (Figure 2B, arrows). At E14.5, Lmx1a−/− cochlea has one cochlear turn instead of two (Figure 2C, arrowhead versus arrow; Koo et al., (2009); Nichols et al., (2008)).

Figure 2. Melanoblasts are first present and then lost from Lmx1a−/− mutant ears stained for Dct mRNA expression. Whole-mount (A) and crossed section (B) views of E13.5 wild-type and mutant ears. Many melanoblasts have already homed to the cochlear roof regions of both (arrows). At E14.5 (C), melanoblasts form a thin line following the cochlear turns (arrow). Lmx1a−/− cochlea is made of only one cochlear turn that shows labeling melanoblasts (arrowhead). In E16.5 cochlea (D), most cochlear melanoblasts have homed to the pre-marginal region, showing a narrow band in the medial view of the cochlea of Lmx1a control mice. The cochlear cartilage was removed before staining. The intact vestibular capsule prevented staining of vestibular melanoblasts. Medial view of an E16.5 mutant ear from which the cochlear capsule and part of the vestibular capsule have been removed. Scattered melanoblasts are present, with some concentrated in the apical cochlear duct and absent in the more basal part of the cochlear turn (asterisks). Lateral views of E18.5 mutant and wild-type ears (E). Cochlear capsules have been removed. Melanoblasts are abundant in the wild-type (arrow) and rare in the mutant cochlea (asterisks).

Pigment cell abnormality in Lmx1a KO mice

Antibodies against several proteins can be used to label the pigment cells, including microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) and a cluster of differentiation 44 [CD44 (Renauld et al., 2022)]. We used CD44 labels, which are highly positive for pigment cells within the stria vascularis (Supplementary Figure S1B), and also labeled other cells, such as the lateral wall of the Claudius cells (CCs) (Supplementary Figure S1B′). Brainstem dye insertion shows the spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs) that radiate to reach out to the inner and outer hair cells (Supplementary Figure S1A) by radial fibers (RFs) and the modiolus. Lmx1a KO mice revealed poor segregation of the saccule and cochlear basal turn (Nichols et al., 2008) and showed a different pattern of radial fibers in the base (Supplementary Figures S1C, C′). Massive innervation extends to the posterior canal (PC), while the utricle (U) is incompletely fused between the anterior and horizontal canals (AC and HC). In contrast to the control mice, which show pigment cells in the stria vascularis region (Supplementary Figure S1B), Lmx1a KO mice exhibit a large cluster of CD44-positive cells (potentially pigment cells) that do not extend to innervate the stria vascularis (Supplementary Figures S1B, D). Similar to the WT mice, Lmx1a KO mice have a slight stretch of CCs labeled with CD44 (Supplementary Figures S1B′, D′).

Otic fibrocyte and basal cell layer fail to differentiate without Lmx1a

Since we observed the absence of marginal cell markers and the failure of the melanoblasts to integrate into the stria vascularis, we studied whether the mesenchymal portion of the lateral wall underneath the stria vascularis was also affected. Previous papers have shown that Tbx18 is essential for condensation and mesenchymal–epithelial transition into the basal cell layer of the stria vascularis (Trowe et al., 2008). At E18.5, the in situ hybridization showed the expression of Tbx18 in the lateral wall above the developing stria vascularis (Figure 3A). In the absence of Lmx1a, the expression of Tbx18 is either exceptionally low or absent (Figure 3B). Further work using quantification is needed. Nevertheless, the near absence of Tbx18 expression and the absence of pigment cells (unlabeled in Figure 3A) in the mesenchymal cells above the stria vascularis may explain the absence of basal layer formation, as observed in Figure 1B′.

Figure 3. Tbx18 mRNA expression in the periotic mesenchyme that forms the basal layer. Wild-type (A) and mutant (B) cochlear ducts stained for Tbx18 expression. In the wild-type mice, uniformly stained cells are present beneath the pre-strial epithelium (SV), while in the mutant, they are dispersed, and separation between the outer sulcus and stria vascularis cannot be precisely determined (arrowhead). OC, organ of Corti; OS, outer sulcus; RM, Reissner’s membrane; SV, stria vascularis.

Expansion of pendrin expression from the spiral prominence into the location of the stria vascularis

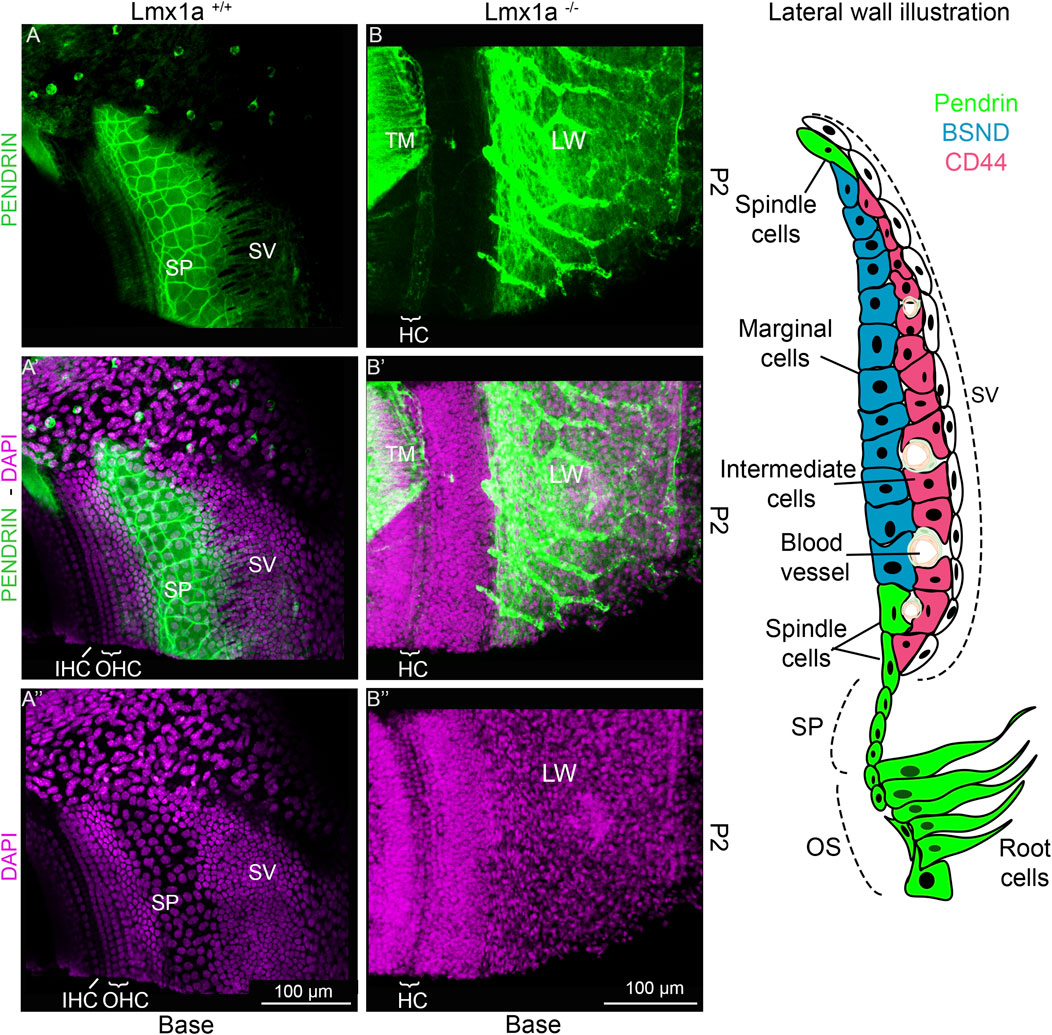

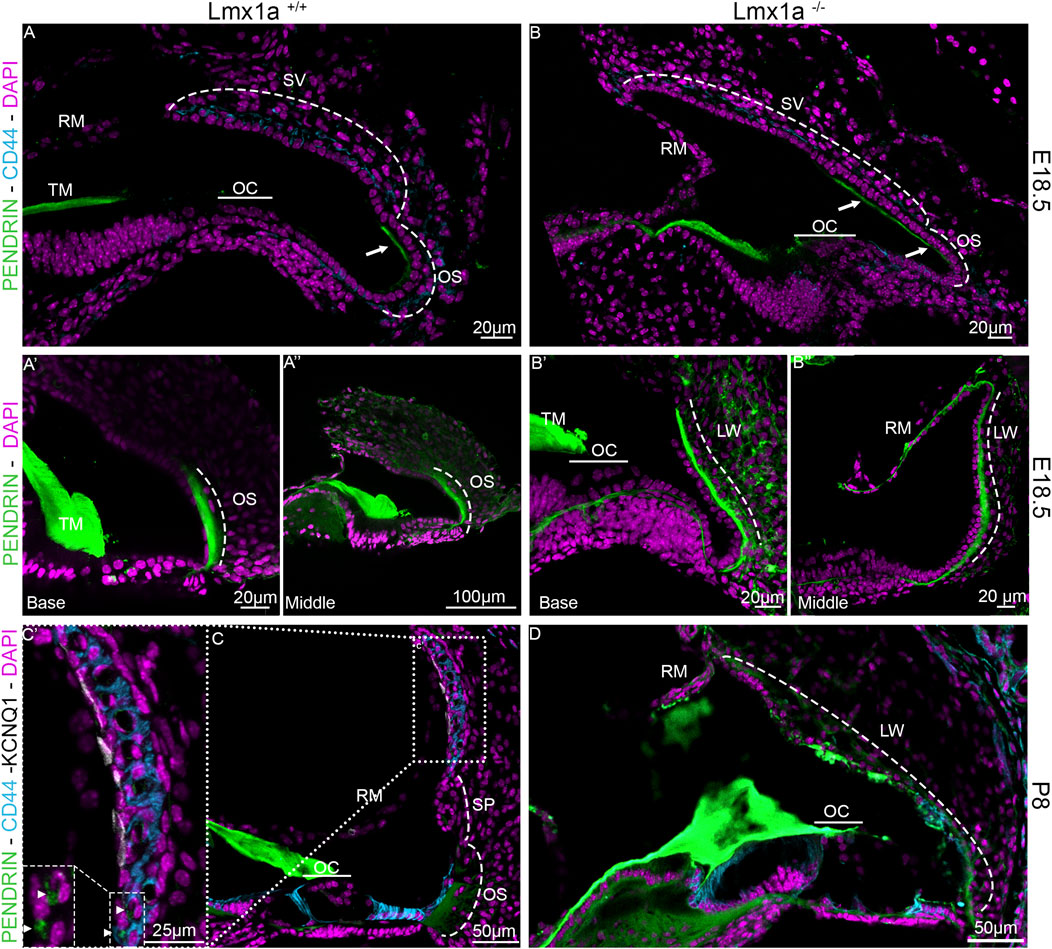

Previous publications of Lmx1a KO have shown that in the absence of a functional Lmx1a protein, there is pendrin-positive cell expression expansion (Mann et al., 2017; Nichols et al., 2008). To verify whether this expansion changes the fate of the cells at the stria vascularis level, we analyzed the features on cochlear roof epithelium and outer sulcus cells with specific markers. In previous research, in the absence of Esrp1, the cochlear duct showed an expansion of Reissner’s membrane (Rohacek et al., 2017). In this study, in the absence of Lmx1a, we observed an expansion of the outer sulcus/spiral prominence positivity for pendrin, visible in the whole mount of the organ of Corti and lateral wall, showing intense positive staining for pendrin (Figure 4A). In control mice, a sharp positive signal contrasts with the broader and gradual reduction in pendrin expression in Lmx1a KO mice. Counterstaining with DAPI (Figures 4A′′, B′′) shows a reduction in the number of OHCs from three to one, adjacent to IHC (HC), as previously reported (Nichols et al., 2020; Nichols et al., 2008; Steffes et al., 2012). The density difference in the cells positive for pendrin likely corresponds to the root and the spindle cells (Figures 4A′, B′). In the whole mount, we noticed specific labeling for the acellular tectorial membrane (TM) that is, in part, removed (Figures 4A, B). The extracellular matrix of the TM can be labeled by specific and less specific labeling such as TECTA, collagen, lectin, and Emilin2 (de Sousa Lobo Ferreira Querido et al., 2023; Fritzsch et al., 2024; Jean et al., 2023; Niazi et al., 2024). Pendrin is labeled with one antibody (Figure 4) but remains unlabeled with another antibody (Supplementary Figure S2), suggesting non-specific labeling. Overall, the expression of pendrin is not only observed in the spiral prominence but also in the root cells and outer sulcus (Figure 4A). Immunostaining on sections shows the highly positive expression of pendrin for the spiral prominence with no labeling on the stria vascularis (SV; Figures 5A–C). In contrast to pendrin-positive cells that end in the spiral prominence in the WT sections (Figures 5A–C), pendrin-positive expression continuous between the outer sulcus to the expected site for Reissner’s membrane in Lmx1a KO mice (Figures 5B′, B′′, D). A more detailed investigation will be required to differentiate whether it corresponds to root or spindle cells.

Figure 4. Pendrin is expressed in the spiral prominence in control and Lmx1a KO mice. Whole mounts flattened out of the basal tip near the ductus reuniens of the cochlea are highly positive for the pendrin antibody (A, B) that is expressed in the outer sulcus and spiral prominence (SP; green). Control mice (A–Aʺ) show that expression has a sharp definition of pendrin (green) that ends up in the base, showing the slightly larger nuclei, which are indicated adjacent to the stria vascularis (SV) that are positive for spiral prominence cells. In contrast, Lmx1a KO mice show no clear delineation of pendrin, which expands from the outer sulcus (OS) beyond the stria vascularis (B–Bʺ). The staining of the tectorial membrane (TM) is counterstained with pendrin, which is not positive for the acellular matrix (A, B). The insert on the right shows the different cell types that have been described in the stria vascularis and adjacent cells according to Koh et al. (2023). Abbreviations: CCs, Claudius cells; HCs, hair cells; LW, lateral wall; MCs, marginal cells; IHCs, inner hair cells; IMCs, intermediate cells; OHCs, outer hair cells; OS, outer sulcus; RC, root cells; SC, spindle cells; SL, spiral ligament; SP, spiral prominence. The bar indicates 100 µm.

Figure 5. Expansion of pendrin expression in Lmx1a KO mice. Immunolabeling of E18.5 Lmx1a WT (A) and KO (B) for pendrin (green) and CD44 (cyan). At E18.5, pendrin expression is restricted to the apical portion of the outer sulcus cells (A–Aʺ). In the Lmx1a mutant (B–Bʺ), the labeling for pendrin (green) is expanded compared to WT and seems to overlap above the position of the future stria vascularis (two arrows). At P8, the stria vascularis is easily defined by marginal cells labeled by KCNQ1 (white) and intermediate cells labeled by CD44 (cyan) in Lmx1a+/+ (C, C′) but not in Lmx1a−/− (D), where pendrin (green) labels the lateral wall (LW) from the outer sulcus (OS) to Reissner’s membrane (RM; labeled with DAPI, lilac). Pendrin is also expressed in the spindle cells (arrowhead) of the stria vascularis in the WT cochlea, as shown in the magnification insert (C′). Spiral prominence is indicated (SP in (C)).

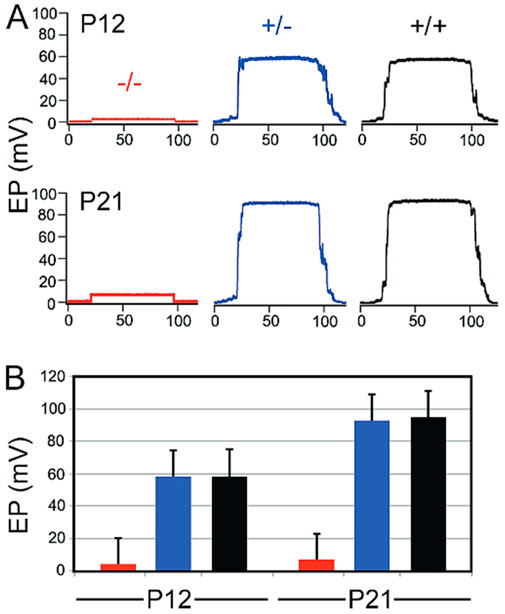

Lmx1a is required for the development of the endocochlear potential

We examined the functional status of the Lmx1a mutant stria by comparing wild-type, heterozygote, and mutant EP (endocochlear potential) at P12 and P21. Six animals from each age/genotype were used. Figure 6 illustrates representative EP waveforms. Without a functional stria vascularis, the EP, a direct measurement of stria function, was not generated, leading to hearing loss. In this Lmx1a KO model, we measured the EP at P12 (during development) and P21 (mature EP) and confirmed a total absence of EP remained at less than 6-mV, as expected in the absence of a differentiated stria vascularis (Figures 6A, B). This absence of EP aligned with previous publications showing a profound hearing loss in Lmx1a KO mice. Thus, a functioning stria vascularis capable of producing the endocochlear potential is never present in Lmx1a mutant mice.

Figure 6. Lmx1a mutant never develops an endocochlear potential. Representative EP waveforms from mutant (red), heterozygous (blue), and wild-type (black) ears at P12 and P21 (A). Means and standard deviations for EP’s on P12 and P21 (B).

Discussion

Our data show that the fusion of the base with the saccule in Lmx1a KO mice leads to an expansion of the pendrin expression in the lateral wall, which lacks a normal formation of a stria vascularis. The loss of Lmx1a causes the cochlear base and saccule to abnormally fuse. The ductus reuniens, which connects the cochlear base with the saccule, relies on a normal EP to maintain fluid homeostasis and separates the auditory (∼80 mV) and vestibular (∼1 mV) fluids (Figure 6).

Lmx1a is required for the formation of the stria vascularis

The molecular development of the lateral wall is not fully understood, but its failure to appropriately develop leads to profound hearing loss due to its essential role in endolymph homeostasis (Bovee et al., 2024; Thulasiram et al., 2024; Wangemann, 1995). During embryonic development, the cochlear roof epithelium expresses OC90 as early as E10.5 (Hartman et al., 2015). More recently, Qin et al. showed by RNAseq that OC90-positive cells can be divided into two populations. One is the Wnt4-positive population, which will give rise to Reissner’s membrane, and the other is the GSC-positive population, which will give rise to the future marginal cells (Munnamalai and Fekete, 2020; Qin et al., 2024). Examples of genes essential for forming the stria vascularis have been shown through mutations, such as integrating a retrotransposon in chromosome 11 and creating a cochlear duct without a lateral wall. In this mutant, the spiral prominence attaches directly to Reissner’s membrane, creating a truncated cochlear duct, where the scala media is smaller due to the relatively low height at which Reissner’s membrane is attached (Song et al., 2021). In the knockout for a splicing protein Espr1, the stria vascularis is absent and replaced by a longer Reissner’s membrane due to an ectopic Fgf9 signaling, creating a cell fate switch from marginal cells to Reissner’s membrane cells (Rohacek et al., 2017). In this study, we observed a different cell fate switch toward spiral prominence instead of Reissner’s membrane identity (Figures 1, 5). A similar cell fate has also been reported in the absence of ERR-beta/NR3B2, which led to a partial conversion of marginal cell fate toward the neighboring pendrin-expressing cells (Chen and Nathans, 2007). Further studies are required to elucidate the signaling pathway through which the lateral wall takes the spiral prominence identity.

During normal development, after marginal cells’ differentiation and intermediate cells’ recruitment, the mesenchymal cells aggregate and form the basal cell layer. This allows for the isolation of the stria vascularis interstitial space from the rest of the inner ear, and this separation is essential for hearing function (Gow et al., 2004; Nin et al., 2008; Souter and Forge, 1998; Wangemann, 2006; Xie et al., 2023) In the Lmx1a−/− mouse model, we note a single layer of epithelial cells at the level of the stria vascularis, which is visible with phalloidin staining on postnatal sections. Furthermore, the absence of the basal cell layer may be mediated by an absence of Tbx18, a transcription factor essential for mesenchymal aggregation onto the basal cell layer (Figure 3) during the development (Trowe et al., 2008). This absence of proper development into marginal, intermediate, and basal cell layers explains the absence of the endocochlear potential (Figure 6) and compromised hearing in Lmx1a KO mice, as previously reported for this mouse model (Steffes et al., 2012).

Lmx1a is required for the proper recruitment of melanoblasts onto the stria vascularis

To develop properly, the stria vascularis requires the recruitment of pigment cells that will become intermediate cells and extrude K+ (Renauld et al., 2022; Steel and Barkway, 1989; Wangemann, 2006). In the absence of Lmx1a, we observed the migration of the melanoblasts (positive for Dct at E13.5), but later, these cells were absent from the cochlear roof (Figure 2). It would be interesting to study more systematically the disappearance of these cells to determine whether they died due to the absence of a survival signal as observed in other strial-defect-related deafness models, such as for the MITF mutation, where MITF has been suspected to be an important melanocyte survival factor (Ni et al., 2013; Steel and Barkway, 1989). A noticeable difference is the timeline of melanoblast disappearance occurring between P1 and P7 in the MITF mutation versus the current model, where the melanoblasts are almost inexistent as early as E18.5 (Figure 2E). This intrinsic defect would also explain the lack of pigmentation in the thoracic region of mutant mice (Ni et al., 2013). Another explanation for the disappearance of the melanoblasts on the roof of the cochlear duct could be that the cells integrate into the glial cells of the spiral ganglion in the absence of recruitment signals from the marginal cell layer as 80% of the intermediate cells originate from glial cell precursors (Renauld et al., 2022). Notably, many CD44-positive cells are clustered around the spiral ganglion neurons (Supplementary Figure S1), but further lineage tracing experiments are required to confirm whether these cells come from the Dct-positive cells present above the cochlear roof at E13.5.

The absence of Lmx1a expands the expression of the anion exchanger protein pendrin on the lateral wall

A recent analysis of the pendrin null mutation (Slc26a4−/−) revealed a role of pendrin in the development of the cochlea, where it is needed for the formation of spindle cells and the spiral ligament, which contain extrinsic cellular components, a factor that enables cell-to-cell communication (Koh et al., 2023). The loss of pendrin disrupts the pH homeostasis mechanism, leading to acidic pH in the endolymphatic potential (Koh et al., 2023). As the stria vascularis is absent and pendrin expression is expanded, it would be interesting in future experiments to assess the pH present in Lmx1a KO mice endolymph. So far, few genes influencing pendrin have been identified in inner ear development. Pendrin expression is dependent on Foxi1, which regulates endolymphatic sac homeostasis and controls the hydrops formation (Hulander et al., 2003; Szeto et al., 2022). Without Lmx1a expression, the inner ear lacks the formation of an endolymphatic duct (Nichols et al., 2008) that is highly positive in pendrin (Figures 4, 5, 7; Supplementary Figure S2). Foxi1 has been shown to regulate pendrin expression in the endolymphatic sac, but its absence does not prevent pendrin expression in the cochlea (Hulander et al., 2003). Pendrin is also not dependent on Pax2, a highly expressed transcription factor in the lateral wall of the developing cochlear duct (Bouchard et al., 2010; Burton et al., 2004; Hosoya et al., 2022). In this study, the expression of non-functional Lmx1a showed increased pendrin expression, extending from the spiral prominence to Reissner’s membrane (Figures 4, 5; Supplementary Figure S2). Future studies on the molecular interaction between Lmx1a and pendrin may be warranted.

Figure 7. Inner ear abnormality in Lmx1a KO mice. In control mice (A), hair cell organization is nearly close to the tip of the base that segregates from the saccule by the ductus reuniens. In addition, a foramen segregates between the saccule and utricle. In contrast to Lmx1 KO mice (B), middle turn is already broad and will be wider close to the saccule that blends with the basal tip. Note that the utricle and saccule fuse with each other and thus do not show neither the ductus reuniens nor the utriculosaccular foramen, shown in control mice. After E18.5 (A′), Lmx1a expression is limited to the spiral prominence in WT mice adjacent to SV but expands in Lmx1a KO mice (Nichols et al., 2008). Our current study revealed that in Lmx1a KO mice (B′), pendrin expression is expanded compared to wild-type mice. In WT mice, Lmx1a in situ signal (yellow, Nichols et al., 2008) is in the lateral wall that extends between the Claudius cells and is adjacent to the stria vascularis (SV) that contains the pigment cells that will develop into the intermediate cells (blue, CD44) adjacent to KCNQ1 (lilac). In contrast, the Lmx1a mutant mice show an expansion of Lmx1a expression. Claudius cells (CCs) and interdental cells (ICs) are weakly positive for pendrin. Neither the pigment cells (CD44 and KCNQ1) nor the stria vascularis can be found in Lmx1a KO mice. The pendrin protein expression (green) overlaps with Lmx1a in the WT but will expand and overlap with the stria vascularis in Lmx1a KO.

It was shown that SOX9 causes deafness via distinct mechanisms in the endolymphatic sac (ES)/duct and cochlea. SOX10 is downregulated, and there is developmental persistence of progenitors, resulting in fewer mature cells. In the postnatal stria vascularis, there is impaired normal interaction of SOX9 and SOX10, repressing the expression of the water channel Aquaporin 3, thereby contributing to endolymphatic hydrops (Szeto et al., 2022). In contrast, to expand hydrops, the ear remains small in the absence of the endolymphatic sac (Nichols et al., 2008; Roux et al., 2023), which does not form a simple sac without canal cristae that continue between the saccule and basal turn in Lmx1a KO mice (Nichols et al., 2020).

In conclusion, the absence of Lmx1a profoundly alters cochlear morphology and function, preventing the formation of a functional stria vascularis and cochlear potential. This disruption leads to an abnormal auditory–vestibular continuum, shedding light on the role of Lmx1a in establishing the distinct ionic environments necessary for auditory and vestibular function. These findings provide important insights into congenital hearing and balance disorders linked to developmental disruptions in inner ear compartmentalization and ion homeostasis. In the absence of Lmx1a, we observe an absence of stria vascularis markers due to the failure of marginal cells to differentiate correctly, the inability to recruit migrating melanoblasts, and the absence of aggregation of basal cells. Furthermore, we also observed an expansion of pendrin expression (schematic, Figure 7), which highlights the importance of Lmx1a in the cell fate determination and differentiation of the lateral wall of the cochlear duct, which does not segregate by a ductus reuniens. Moreover, the absence of the ∼80 mV endocochlear potential in Lmx1a KO mice requires the three layers of the stria vascularis in the cochlea, while it forms a simpler two-layer structure in the lateral wall, resembling the vestibular system with a ∼1 mV potential.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center IACUC #15-057 and by Creighton University IACUC #10-35. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JR: writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. II: data curation, methodology, resources, and writing–review and editing. EY: funding acquisition, validation, and writing–original draft. RS: funding acquisition, investigation, and writing–review and editing. CA: data curation, resources, and writing–review and editing. DH: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, and writing–review and editing. HL: data curation, methodology, and writing–review and editing. DN: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, resources, visualization, and writing–review and editing. JB: methodology and writing–review and editing. MN: methodology, investigation, and writing–review and editing. XW: data curation and writing–review and editing. TQ: data curation and writing–review and editing. MS: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, and writing–review and editing. VC: writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. BF: writing–original draft and writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. ENY and BF were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants AG060504 and AG051443 and DC016099 and DC015135); RJHS was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants DC002842, DC012049, and DC017955); VC was supported by R01 NS093009 and R01 NS127973; and MHS was supported by the Research Grant Council in Hong Kong (RGC GRF 17115520). JR was supported in part by revenue from Nebraska’s Tobacco Settlement Funds through the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Its contents represent the view(s) of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of the State of Nebraska or DHHS. This research was partially conducted at the Auditory and Vestibular Technology Core (AVT) at Creighton University, Omaha, NE (RRID: SCR_023866). This facility is supported by the Creighton University School of Medicine and (grants GM103427 and GM139762) from the National Institute of General Medical Science (NIGMS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This investigation is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Garret Soukup and Marcia Pierce for their help in designing and preparing primers, Ian Jackson for the DCT plasmid, and Andreas Kispert for the Tbx18 plasmid.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2025.1537505/full#supplementary-material

References

Bouchard, M., de Caprona, D., Busslinger, M., Xu, P., and Fritzsch, B. (2010). Pax2 and Pax8 cooperate in mouse inner ear morphogenesis and innervation. BMC Dev. Biol. 10, 89–17. doi:10.1186/1471-213X-10-89

Bovee, S., Klump, G. M., Köppl, C., and Pyott, S. J. (2024). The stria vascularis: renewed attention on a key player in age-related hearing loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 5391. doi:10.3390/ijms25105391

Burton, Q., Cole, L. K., Mulheisen, M., Chang, W., and Wu, D. K. (2004). The role of Pax2 in mouse inner ear development. Dev. Biol. 272, 161–175. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.024

Chan, D. K., and Chang, K. W. (2014). GJB2-associated hearing loss: systematic review of worldwide prevalence, genotype, and auditory phenotype. Laryngoscope 124, E34–E53. doi:10.1002/lary.24332

Chen, J., and Nathans, J. (2007). Estrogen-related receptor beta/NR3B2 controls epithelial cell fate and endolymph production by the stria vascularis. Dev. Cell 13, 325–337. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.011

Chizhikov, V., Steshina, E., Roberts, R., Ilkin, Y., Washburn, L., and Millen, K. J. (2006). Molecular definition of an allelic series of mutations disrupting the mouse Lmx1a (dreher) gene. Mamm. Genome 17, 1025–1032. doi:10.1007/s00335-006-0033-7

Chizhikov, V. V., Iskusnykh, I. Y., Fattakhov, N., and Fritzsch, B. (2021). Lmx1a and Lmx1b are redundantly required for the development of multiple components of the mammalian auditory system. Neuroscience 452, 247–264. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.11.013

de Sousa Lobo Ferreira Querido, R., Ji, X., Lakha, R., Goodyear, R. J., Richardson, G. P., Vizcarra, C. L., et al. (2023). Visualizing collagen fibrils in the cochlea’s tectorial and basilar membranes using a fluorescently labeled collagen-binding protein fragment. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngology 24, 147–157. doi:10.1007/s10162-023-00889-z

Diaz, R. C., Vazquez, A. E., Dou, H., Wei, D., Cardell, E. L., Lingrel, J., et al. (2007). Conservation of hearing by simultaneous mutation of Na, K-ATPase and NKCC1. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngology 8, 422–434. doi:10.1007/s10162-007-0089-4

Elliott, K. L., Iskusnykh, I. Y., Chizhikov, V. V., and Fritzsch, B. (2023). Ptf1a expression is necessary for correct targeting of spiral ganglion neurons within the cochlear nuclei. Neurosci. Lett. 806, 137244. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2023.137244

Failli, V., Bachy, I., and Rétaux, S. (2002). Expression of the LIM-homeodomain gene Lmx1a (dreher) during development of the mouse nervous system. Mech. Dev. 118, 225–228. doi:10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00254-x

Fritzsch, B., Signore, M., and Simeone, A. (2001). Otx 1 null mutant mice show partial segregation of sensory epithelia comparable to lamprey ears. Dev. genes Evol. 211, 388–396. doi:10.1007/s004270100166

Fritzsch, B., Weng, X., Yamoah, E. N., Qin, T., Hui, C. C., Lebrón-Mora, L., et al. (2024). Irx3/5 null deletion in mice blocks cochlea-saccule segregation and disrupts the auditory tonotopic map. J. Comp. Neurology 532, e70008. doi:10.1002/cne.70008

Gow, A., Davies, C., Southwood, C. M., Frolenkov, G., Chrustowski, M., Ng, L., et al. (2004). Deafness in Claudin 11-null mice reveals the critical contribution of basal cell tight junctions to stria vascularis function. J. Neurosci. 24, 7051–7062. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1640-04.2004

Hartman, B. H., Durruthy-Durruthy, R., Laske, R. D., Losorelli, S., and Heller, S. (2015). Identification and characterization of mouse otic sensory lineage genes. Front. Cell Neurosci. 9, 79. doi:10.3389/fncel.2015.00079

Hibino, H., Nin, F., Tsuzuki, C., and Kurachi, Y. (2010). How is the highly positive endocochlear potential formed? The specific architecture of the stria vascularis and the roles of the ion-transport apparatus. Pflügers Archiv-European J. Physiology 459, 521–533. doi:10.1007/s00424-009-0754-z

Hornibrook, J., Mudry, A., Curthoys, I., and Smith, C. M. (2021). Ductus reuniens and its possible role in Menière's disease. Otology and Neurotol. 42, 1585–1593. doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000003352

Hosoya, T., Takahashi, M., Honda-Kitahara, M., Miyakita, Y., Ohno, M., Yanagisawa, S., et al. (2022). MGMT gene promoter methylation by pyrosequencing method correlates volumetric response and neurological status in IDH wild-type glioblastomas. J. Neuro-oncology 157, 561–571. doi:10.1007/s11060-022-03999-5

Huang, M., Sage, C., Li, H., Xiang, M., Heller, S., and Chen, Z. Y. (2008). Diverse expression patterns of LIM-homeodomain transcription factors (LIM-HDs) in mammalian inner ear development. Dev. Dyn. 237, 3305–3312. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21735

Hulander, M., Kiernan, A. E., Blomqvist, S. R., Carlsson, P., Samuelsson, E.-J., Johansson, B. R., et al. (2003). Lack of pendrin expression leads to deafness and expansion of the endolymphatic compartment in inner ears of Foxi1 null mutant mice. Development. 130, 2013–2025. doi:10.1242/dev.00376

Jean, P., Wong Jun Tai, F., Singh-Estivalet, A., Lelli, A., Scandola, C., Megharba, S., et al. (2023). Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of the mouse cochlea: an atlas for targeted therapies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 120, e2221744120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2221744120

Kikuchi, K., and Hilding, D. A. (1966). The development of the stria vascularis in the mouse. Acta Otolaryngol. 62, 277–291. doi:10.3109/00016486609119573

Kim, H. M., and Wangemann, P. (2011). Epithelial cell stretching and luminal acidification lead to a retarded development of stria vascularis and deafness in mice lacking pendrin. PLoS One 6, e17949. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017949

Kitajiri, S., Miyamoto, T., Mineharu, A., Sonoda, N., Furuse, K., Hata, M., et al. (2004). Compartmentalization established by claudin-11-based tight junctions in stria vascularis is required for hearing through generation of endocochlear potential. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5087–5096. doi:10.1242/jcs.01393

Koh, J.-Y., Affortit, C., Ranum, P. T., West, C., Walls, W. D., Yoshimura, H., et al. (2023). Single-cell RNA-sequencing of stria vascularis cells in the adult Slc26a4-/-mouse. BMC Med. genomics 16, 133–217. doi:10.1186/s12920-023-01549-0

Koo, S. K., Hill, J. K., Hwang, C. H., Lin, Z. S., Millen, K. J., and Wu, D. K. (2009). Lmx1a maintains proper neurogenic, sensory, and non-sensory domains in the mammalian inner ear. Dev. Biol. 333, 14–25. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.016

Kopecky, B., Johnson, S., Schmitz, H., Santi, P., and Fritzsch, B. (2012). Scanning thin-sheet laser imaging microscopy elucidates details on mouse ear development. Dev. Dyn. 241, 465–480. doi:10.1002/dvdy.23736

Kopecky, B., Santi, P., Johnson, S., Schmitz, H., and Fritzsch, B. (2011). Conditional deletion of N-Myc disrupts neurosensory and non-sensory development of the ear. Dev. Dyn. 240, 1373–1390. doi:10.1002/dvdy.22620

Köppl, C., and Manley, G. A. (2018). A functional perspective on the evolution of the cochlea. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 9 (6), a033241. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a033241

Lee, S. Y., Han, J. H., Carandang, M., Kim, M. Y., Kim, B., Yi, N., et al. (2020). Novel genotype–phenotype correlation of functionally characterized LMX1A variants linked to sensorineural hearing loss. Hum. Mutat. 41, 1877–1883. doi:10.1002/humu.24095

Mann, Z. F., Galvez, H., Pedreno, D., Chen, Z., Chrysostomou, E., Żak, M., et al. (2017). Shaping of inner ear sensory organs through antagonistic interactions between Notch signalling and Lmx1a. Elife 6, e33323. doi:10.7554/eLife.33323

Mei, L., Chen, J., Zong, L., Zhu, Y., Liang, C., Jones, R. O., et al. (2017). A deafness mechanism of digenic Cx26 (GJB2) and Cx30 (GJB6) mutations: reduction of endocochlear potential by impairment of heterogeneous gap junctional function in the cochlear lateral wall. Neurobiol. Dis. 108, 195–203. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2017.08.002

Morris, J. K., Maklad, A., Hansen, L. A., Feng, F., Sorensen, C., Lee, K.-F., et al. (2006). A disorganized innervation of the inner ear persists in the absence of ErbB2. Brain Res. 1091, 186–199. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.090

Munnamalai, V., and Fekete, D. M. (2020). The acquisition of positional information across the radial axis of the cochlea. Dev. Dyn. 249, 281–297. doi:10.1002/dvdy.118

Ni, C., Zhang, D., Beyer, L. A., Halsey, K. E., Fukui, H., Raphael, Y., et al. (2013). Hearing dysfunction in heterozygous M itfMi-wh/+ mice, a model for W aardenburg syndrome type 2 and T ietz syndrome. Pigment cell and melanoma Res. 26, 78–87. doi:10.1111/pcmr.12030

Niazi, A., Kim, J. A., Kim, D. K., Lu, D., Sterin, I., Park, J., et al. (2024). Microvilli control the morphogenesis of the tectorial membrane extracellular matrix. Dev. Cell. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2024.11.011

Nichols, D. H., Bouma, J. E., Kopecky, B. J., Jahan, I., Beisel, K. W., He, D. Z., et al. (2020). Interaction with ectopic cochlear crista sensory epithelium disrupts basal cochlear sensory epithelium development in Lmx1a mutant mice. Cell tissue Res. 380, 435–448. doi:10.1007/s00441-019-03163-y

Nichols, D. H., Pauley, S., Jahan, I., Beisel, K. W., Millen, K. J., and Fritzsch, B. (2008). Lmx1a is required for segregation of sensory epithelia and normal ear histogenesis and morphogenesis. Cell tissue Res. 334, 339–358. doi:10.1007/s00441-008-0709-2

Nin, F., Hibino, H., Doi, K., Suzuki, T., Hisa, Y., and Kurachi, Y. (2008). The endocochlear potential depends on two K+ diffusion potentials and an electrical barrier in the stria vascularis of the inner ear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 1751–1756. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711463105

Pauley, S., Wright, T. J., Pirvola, U., Ornitz, D., Beisel, K., and Fritzsch, B. (2003). Expression and function of FGF10 in mammalian inner ear development. Dev. Dyn. 227, 203–215. doi:10.1002/dvdy.10297

Pingault, V., Ente, D., Dastot-Le Moal, F., Goossens, M., Marlin, S., and Bondurand, N. (2010). Review and update of mutations causing Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 31, 391–406. doi:10.1002/humu.21211

Qin, T., So, K. K. H., Hui, C. C., and Sham, M. H. (2024). Ptch1 is essential for cochlear marginal cell differentiation and stria vascularis formation. Cell Rep. 43, 114083. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114083

Renauld, J. M., Davis, W., Cai, T., Cabrera, C., and Basch, M. L. (2021). Transcriptomic analysis and ednrb expression in cochlear intermediate cells reveal developmental differences between inner ear and skin melanocytes. Pigment cell and melanoma Res. 34, 585–597. doi:10.1111/pcmr.12961

Renauld, J. M., Khan, V., and Basch, M. L. (2022). Intermediate cells of dual embryonic origin follow a basal to apical gradient of ingression into the lateral wall of the cochlea. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 867153. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.867153

Rickheit, G., Maier, H., Strenzke, N., Andreescu, C. E., De Zeeuw, C. I., Muenscher, A., et al. (2008). Endocochlear potential depends on Cl− channels: mechanism underlying deafness in Bartter syndrome IV. EMBO J. 27, 2907–2917. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.203

Ritter, K. E., and Martin, D. M. (2019). Neural crest contributions to the ear: implications for congenital hearing disorders. Hear Res. 376, 22–32. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2018.11.005

Rohacek, A. M., Bebee, T. W., Tilton, R. K., Radens, C. M., McDermott-Roe, C., Peart, N., et al. (2017). ESRP1 mutations cause hearing loss due to defects in alternative splicing that disrupt cochlear development. Dev. Cell 43, 318–331. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2017.09.026

Rose, K. P., Manilla, G., Milon, B., Zalzman, O., Song, Y., Coate, T. M., et al. (2023). Spatially distinct otic mesenchyme cells show molecular and functional heterogeneity patterns before hearing onset. iScience 26, 107769. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.107769

Roux, I., Fenollar-Ferrer, C., Lee, H. J., Chattaraj, P., Lopez, I. A., Han, K., et al. (2023). CHD7 variants associated with hearing loss and enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct. Hum. Genet. 142, 1499–1517. doi:10.1007/s00439-023-02581-x

Sagara, T., Furukawa, H., Makishima, K., and Fujimoto, S. (1995). Differentiation of the rat stria vascularis. Hear Res. 83, 121–132. doi:10.1016/0378-5955(94)00195-v

Sakagami, M., Fukazawa, K., Matsunaga, T., Fujita, H., Mori, N., Takumi, T., et al. (1991). Cellular localization of rat Isk protein in the stria vascularis by immunohistochemical observation. Hear. Res. 56, 168–172. doi:10.1016/0378-5955(91)90166-7

Schrauwen, I., Chakchouk, I., Liaqat, K., Jan, A., Nasir, A., Hussain, S., et al. (2018). A variant in LMX1A causes autosomal recessive severe-to-profound hearing impairment. Hum. Genet. 137, 471–478. doi:10.1007/s00439-018-1899-7

Smith, C. M., Curthoys, I. S., and Laitman, J. T. (2024). A morphometric comparison of the ductus reuniens in humans and Guinea pigs, with a note on its evolutionary importance. Anat. Rec. doi:10.1002/ar.25534

Song, C., Li, J., Liu, S., Hou, H., Zhu, T., Chen, J., et al. (2021). An L1 retrotransposon insertion–induced deafness mouse model for studying the development and function of the cochlear stria vascularis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2107933118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2107933118

Souter, M., and Forge, A. (1998). Intercellular junctional maturation in the stria vascularis: possible association with onset and rise of endocochlear potential. Hear Res. 119, 81–95. doi:10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00042-2

Steel, K. P., and Barkway, C. (1989). Another role for melanocytes: their importance for normal stria vascularis development in the mammalian inner ear. Development 107, 453–463. doi:10.1242/dev.107.3.453

Steel, K. P., Davidson, D. R., and Jackson, I. J. (1992). TRP-2/DT, a new early melanoblast marker, shows that steel growth factor (c-kit ligand) is a survival factor. Development 115, 1111–1119. doi:10.1242/dev.115.4.1111

Steffes, G., Lorente-Cánovas, B., Pearson, S., Brooker, R. H., Spiden, S., Kiernan, A. E., et al. (2012). Mutanlallemand (mtl) and Belly Spot and Deafness (bsd) are two new mutations of Lmx1a causing severe cochlear and vestibular defects. PloS one 7, e51065. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051065

Strepay, D., Olszewski, R. T., Nixon, S., Korrapati, S., Adadey, S., Griffith, A. J., et al. (2024). Transgenic Tg (Kcnj10-ZsGreen) fluorescent reporter mice allow visualization of intermediate cells in the stria vascularis. Sci. Rep. 14, 3038. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-52663-7

Szeto, I. Y., Chu, D. K., Chen, P., Chu, K. C., Au, T. Y., Leung, K. K., et al. (2022). SOX9 and SOX10 control fluid homeostasis in the inner ear for hearing through independent and cooperative mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2122121119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2122121119

Thulasiram, M. R., Yamamoto, R., Olszewski, R. T., Gu, S., Morell, R. J., Hoa, M., et al. (2024). Molecular differences between neonatal and adult stria vascularis from organotypic explants and transcriptomics. bioRxiv, 590986. doi:10.1101/2024.04.24.590986

Trowe, M. O., Maier, H., Petry, M., Schweizer, M., Schuster-Gossler, K., and Kispert, A. (2011). Impaired stria vascularis integrity upon loss of E-cadherin in basal cells. Dev. Biol. 359, 95–107. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.08.030

Trowe, M. O., Maier, H., Schweizer, M., and Kispert, A. (2008). Deafness in mice lacking the T-box transcription factor Tbx18 in otic fibrocytes. Development 135, 1725–1734. doi:10.1242/dev.014043

Wang, X., Levic, S., Gratton, M. A., Doyle, K. J., Yamoah, E. N., and Pegg, A. E. (2009). Spermine synthase deficiency leads to deafness and a profound sensitivity to alpha-difluoromethylornithine. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 930–937. doi:10.1074/jbc.M807758200

Wangemann, P. (1995). Comparison of ion transport mechanisms between vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells. Hear. Res. 90, 149–157. doi:10.1016/0378-5955(95)00157-2

Wangemann, P. (2006). Supporting sensory transduction: cochlear fluid homeostasis and the endocochlear potential. J. Physiol. 576, 11–21. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112888

Wesdorp, M., de Koning Gans, P. A., Schraders, M., Oostrik, J., Huynen, M. A., Venselaar, H., et al. (2018). Heterozygous missense variants of LMX1A lead to nonsyndromic hearing impairment and vestibular dysfunction. Hum. Genet. 137, 389–400. doi:10.1007/s00439-018-1880-5

Xiao, M., Zheng, Y., Huang, K. H., Yu, S., Zhang, W., Xi, Y., et al. (2023). A novel frameshift variant of LMX1A that leads to autosomal dominant non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss: functional characterization of the C-terminal domain in LMX1A. Hum. Mol. Genet. 32, 1348–1360. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddac301

Keywords: Lmx1a, pendrin, Slc26a4, stria vascularis, spiral prominence, pigment cells

Citation: Renauld JM, Iskusnykh IY, Yamoah EN, Smith RJH, Affortit C, He DZ, Liu H, Nichols D, Bouma J, Nayak MK, Weng X, Qin T, Sham MH, Chizhikov VV and Fritzsch B (2025) Lmx1a is essential for marginal cell differentiation and stria vascularis formation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1537505. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2025.1537505

Received: 04 December 2024; Accepted: 03 February 2025;

Published: 05 March 2025.

Edited by:

Raj Ladher, National Centre for Biological Sciences, IndiaReviewed by:

Dalia Mohamedien, South Valley University, EgyptNorio Yamamoto, Kyoto University Hospital, Japan

Suraj Chakravarthy, Jackson Laboratory, United States

Neelanjana Ray, National Centre for Biological Sciences, India, in collaboration with reviewer SC

Copyright © 2025 Renauld, Iskusnykh, Yamoah, Smith, Affortit, He, Liu, Nichols, Bouma, Nayak, Weng, Qin, Sham, Chizhikov and Fritzsch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victor V. Chizhikov, dmNoaXpoaWtAdXRoc2MuZWR1; Bernd Fritzsch, YmZyaXR6c2NoQHVubWMuZWR1

Justine M. Renauld

Justine M. Renauld Igor Y. Iskusnykh

Igor Y. Iskusnykh Ebenezer N. Yamoah

Ebenezer N. Yamoah Richard J. H. Smith

Richard J. H. Smith Corentin Affortit

Corentin Affortit David Z. He

David Z. He Huizhan Liu

Huizhan Liu David Nichols1

David Nichols1 Mahesh K. Nayak

Mahesh K. Nayak Xin Weng

Xin Weng Tianli Qin

Tianli Qin Mai Har Sham

Mai Har Sham Victor V. Chizhikov

Victor V. Chizhikov Bernd Fritzsch

Bernd Fritzsch