- 1Department of Pharmacology and Physiology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, United States

- 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, United States

- 3Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, United States

- 4Center for Musculoskeletal Research, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, United States

Mechanical factors play critical roles in the pathogenesis of joint disorders like osteoarthritis (OA), a prevalent progressive degenerative joint disease that causes debilitating pain. Chondrocytes in the cartilage are responsible for extracellular matrix (ECM) turnover, and mechanical stimuli heavily influence cartilage maintenance, degeneration, and regeneration via mechanotransduction of chondrocytes. Thus, understanding the disease-associated mechanotransduction mechanisms can shed light on developing effective therapeutic strategies for OA through targeting mechanotransducers to halt progressive cartilage degeneration. Mechanosensitive Ca2+-permeating channels are robustly expressed in primary articular chondrocytes and trigger force-dependent cartilage remodeling and injury responses. This review discusses the current understanding of the roles of Piezo1, Piezo2, and TRPV4 mechanosensitive ion channels in cartilage health and disease with a highlight on the potential mechanotheraputic strategies to target these channels and prevent cartilage degeneration associated with OA.

Introduction

Articular cartilage is a tissue that provides a low-friction surface for smooth movement of diarthrodial joints under mechanical loading. More than 300 million people globally and 35 million Americans are affected by osteoarthritis (OA), a debilitating disease with risk factors of increasing age, female sex, obesity, joint injuries, and overuse of joints (Buckwalter and Martin, 2006; Michael et al., 2010; Kloppenburg and Berenbaum, 2020; Yunus et al., 2020). The hallmark of OA is progressive cartilage degeneration, and patients with OA usually experience pain with everyday movement that can ultimately lead to a loss in function of the joint (Lawrence et al., 2008). OA patients also have an increased rate of comorbidities including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, likely due to decreased physical activity resulting from loss in joint function (Suri et al., 2012; Muckelt et al., 2020). Numerous disease-modifying OA drugs (DMOADs) have been developed to reduce cartilage degeneration and joint discomfort, yet none have demonstrated long-term efficacy and safety (Hodgkinson et al., 2021; Oo et al., 2021).

Mechanical cues influence chondrocyte biosynthesis via mechanotransduction, a conversion process of mechanical stimuli into intracellular biochemical responses (Lee et al., 2000; Leong et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2020). Chondrocytes are intrinsically mechanosensitive and sense a wide-range of mechanical loading due to the abundantly expressed mechanically-activated (MA) ion channels, including Piezo1, Piezo2, and TRPV4 (Suzuki et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Delco and Bonassar, 2021). These channels are apart of the chondrocyte channelome, where different ion channels can play a role in regulating membrane potential, cell volume, intracellular pH, or mechanotransduction (Erickson et al., 2001; Barrett-Jolley et al., 2010; Mobasheri et al., 2019). A large gradient in Ca2+ concentration is maintained at rest, where Ca2+ is more abundant extracellularly than intracellularly, allowing Ca2+ influx into chondrocytes upon activation of MA channels (Lv et al., 2018). Mechanical stimuli activate MA channels for a rapid influx of ions, such as Ca2+, to depolarize the cell membrane, and initiate downstream signaling cascades, including changes in gene expression and protein synthesis. Intracellular Ca2+ functions as a second messenger to influence cell responses through modulation of cell proliferation, transcription, protein secretion, and apoptosis (Héraud et al., 2000; Chao et al., 2006; Fodor et al., 2013; Gong et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). In particular, TRPV4 channels have been shown to influence chondrocyte differentiation, with intracellular Ca2+ promoting increased SOX9, collagen II (Col-II), and aggrecan expression (Muramatsu et al., 2007; Wuest et al., 2018).

Since chondrocytes experience an array of mechanical loads, including compression, tension, shear, and hydrostatic and osmotic pressure through extracellular matrix (ECM) and pericellular matrix (PCM), the local composition and stiffness of matrix is altered during OA progression, and, in turn, influences chondrocyte mechanosensitivity and mechanotransduction (Yellowley et al., 1997; Holloway et al., 2004; Buckwalter et al., 2005; Sanchez-Adams et al., 2011; Guilak et al., 2018; Chery et al., 2020). Understanding OA-associated mechanotransduction mechanisms and key mechanotransducers in chondrocytes may provide novel strategies to inhibit or slow the rate of chondrocyte death and ECM degradation that leads to severe OA (Sanchez-Adams et al., 2014). Suspended in cartilage tissue are a few chondrocytes that secrete ECM and regulate tissue homeostasis. Cartilage ECM includes negatively charged proteoglycans, and other molecules like Col-II. The charged nature of proteoglycans attracts water into the matrix, allowing the cartilage to support compressive forces, while Col-II provides tensile strength (Sanchez-Adams et al., 2011; Mardones et al., 2015; Hodgkinson et al., 2021). Immediately surrounding the chondrocyte is the PCM, which can act as a mechanical adaptor to regulate local stress and strain, protecting chondrocytes from large local strains (Korhonen and Herzog, 2008; Wilusz et al., 2013).

In the chondrocyte, Ca2+ homeostasis is important in maintaining ECM components and overall health of the cartilage (Wilkins et al., 2003). Disruption of this homeostasis can affect synthesis of ECM molecules and promote catabolism (Guilak et al., 1999; Sánchez and López-Zapata, 2015; Gong et al., 2017). In particular, basic calcium phosphate crystals, found in severe forms of OA, were shown to stimulate chondrocytes by elevating intracellular Ca2+. As a result of abnormal Ca2+ levels, increased catabolic enzyme production and chondrocyte apoptosis occurred, showing the importance of homeostatic intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in maintaining chondrocyte health and cartilage integrity (Nguyen et al., 2012).

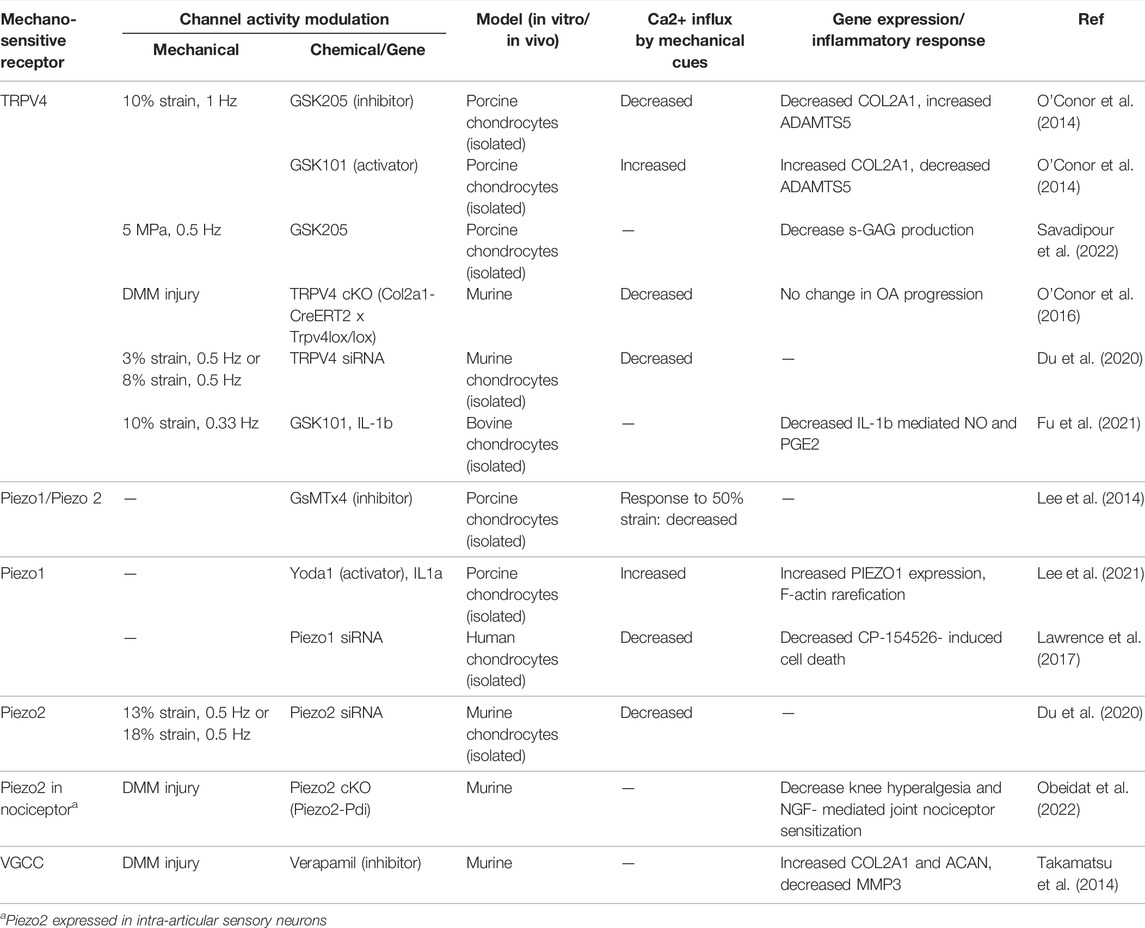

It is well established that exercise or physiologic loads promote cartilage anabolism, while traumatic or hyper-physiologic loads trigger cartilage catabolism (Griffin and Guilak, 2005; Guilak, 2011; Ashwell et al., 2013; McCutchen et al., 2017). In vivo study of rats demonstrated exercise’s ability to promote DNA repair, ECM synthesis, and suppress ECM degradation enzymes (Blazek et al., 2016). In vitro studies reveal that chondrocytes sense applied loads to elicit an appropriate catabolic or anabolic response in strain magnitude-, loading frequency-, and loading duration-dependent manners. For instance, Bleuel et al. showed that chondrocytes under 3–10% strain, 0.17–0.5 Hz, and 2–12 h of stimulation enhances anabolic responses, including increased Col-II and aggrecan expression; and strain, frequency, and duration above 10%, 0.5 Hz, and 12 h, respectively, led to catabolic activity, including upregulation of degradative enzymes like matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and downregulation of Col-II and aggrecan expression (Bleuel et al., 2015). Different mechanically activated Ca2+ channels in the chondrocyte channelome are the specialized sensors for physiologic or hyper-physiologic loading, initiating specific downstream metabolic responses depending on the magnitude or frequency of a mechanical load. These specific mechano-signaling mechanisms provide potential therapeutic targets for cartilage degeneration. This review summarizes the current understanding of the mechano-signaling mechanisms mediated by TRPV4, Piezo1, and Piezo2 channels in healthy and OA cartilage (Table 1). In addition, we highlight potential therapeutic strategies to halt OA progression.

TABLE 1. Selected studies demonstrating mechanosensitive ion channel activity, Ca2+ response to mechanical cues, and biosynthetic activities.

Chondrocyte Mechanotransduction Mechanisms

Cartilage Matrix Homeostasis and OA

Chondrocytes regulate cartilage homeostasis by balancing the synthesis of matrix molecules (Col-II, proteoglycans, aggrecan, etc.) and degrading enzymes (MMPs, ADAMTs, etc.) (Goldring and Marcu, 2009). Physiological loading helps to maintain the integrity of cartilage by decreasing activities of MMPs and suppressing pro-inflammatory factors, but promoting the secretion of more ECM (Wong et al., 1999; Bonassar et al., 2001; Mauck et al., 2003; Goldring and Marcu, 2009; Ng et al., 2009; Leong et al., 2011; Torzilli et al., 2011). Dynamic loading also facilitates transport of molecules throughout the cartilage using convection, which is faster compared to diffusion (Mow et al., 1994; Grodzinsky et al., 2000; Quinn et al., 2001; Evans and Quinn, 2006a; Evans and Quinn, 2006b; Chahine et al., 2009). The transition from healthy to diseased cartilage occurs through an imbalance in the metabolism (catabolic and anabolic reactions) of ECM. Under injurious loading, inflammation promotes enzymatic degradation of ECM proteins through increased MMP activity, resulting in the loss of proteoglycan and other structural matrix components (Sanchez-Adams et al., 2014; Fukui et al., 2015). This matrix degradation alters compressive stiffness and shear resistance of cartilage (Boschetti and Peretti, 2008; Wong et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2019; Mieloch et al., 2019).

In the early phase of OA, these changes are pronounced in the PCM, the extracellular environment immediately surrounding the chondrocyte (Wilusz et al., 2014). In particular, chondrons (chondrocytes and their surrounding PCM) from human OA cartilage experience about 40% reduction in Young’s elastic moduli and 66% more compressive strains than their healthy counterparts (Alexopoulos et al., 2003; Alexopoulos et al., 2005). Aggrecan is synthesized primarily in the PCM and turns over at a faster rate in the PCM than in the surrounding territorial domain ECM (Quinn et al., 1999). During OA related degradation, aggrecan is the first component of the matrix to be degraded (Lark et al., 1995; Han et al., 2011; Chery et al., 2020). Chery et al. performed destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) surgery on mouse knees, an injury model of OA progression, and showed that decrease in the PCM compressive modulus occurs about 3-days post-injury, which correlated with a reduction in aggrecan staining seen in the PCM. This decrease in modulus was lower in the PCM than surrounding ECM, suggesting that changes related to OA first occur in the PCM (Guilak et al., 2018; Chery et al., 2020). Compressive modulus in the PCM was further decreased as OA progressed. Blocking of PCM degradation with GM6001, an MMP and aggrecanase inhibitor, lead to an increase in PCM modulus after injury, suggesting PCM integrity at early stages of OA is important to maintaining joint health (Chery et al., 2020). Yet, several experimental therapies targeting MMPs have not been successful in preventing cartilage degradation (Krzeski et al., 2007; Grässel and Muschter, 2020). On the other hand, TRPV4, Piezo1, and Piezo2 channels play a role in Ca2+ signaling dependent on substrate stiffness. Specifically, TRPV4 responds to stiffer substrates, while Piezo1/2 to less stiff substrates, making these ion channels potential targets for OA treatment (Du et al., 2021).

TRPV4-Mediated Mechanotransduction Under Physiologic Loading

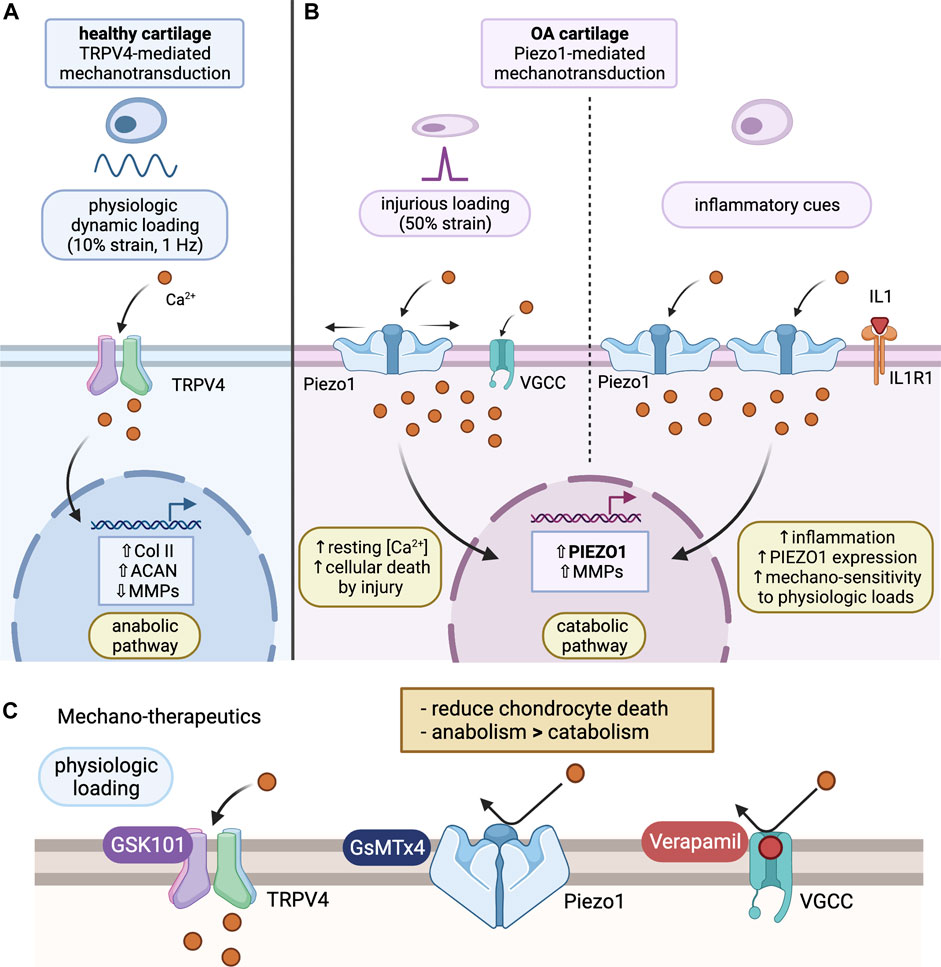

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) is a cation channel that allows influx of Ca2+, mediating anabolic responses of chondrocytes triggered by physiological loading (Figure 1A) (Nilius et al., 2003; Hattori et al., 2021); thus, TRPV4 is a potential therapeutic target for OA treatment. TRPV4 is more sensitive to osmotic pressure as a result of increasing charge density by cartilage compression, suggesting that TRPV4 activation is stimulated by osmotic stress transduced from mechanical loading (Sánchez et al., 2014; Lv et al., 2018; Nims et al., 2021). In addition, TRPV4 has been shown to have a delay in Ca2+ response after osmotic stimulation (Lv et al., 2018). In vitro experiments involving the use of TRPV4 agonist (GSK101) and antagonist (GSK205) found that TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ signaling plays an essential role in the transduction of mechanical stimuli to reinforce and maintain the cartilage matrix and joint health. Physiological loading in this case was defined as 10% strain. TRPV4 activation resulted in an increase in Col-II and sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in cartilage. However, chondrocytes with GSK205 in the presence of a mechanical load expressed significantly lower levels of Col-II and higher levels of MMPs (O'Conor et al., 2014; Trompeter et al., 2021a; Savadipour et al., 2022). The effect of TRPV4 activation using GSK101 has been observed to be analogous to that of a mechanical load; chondrocytes treated with GSK101 decrease the synthesis of pro-inflammatory molecules and degradative enzymes (Fu et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1. Chondrocyte mechanotransduction and potential mechano-therapeutics. (A) TRPV4-mediated Mechanotransduction of Healthy Cartilage: under physiological loading (10% strain), Ca2+ ions enter through activated TRPV4 channel and promote an anabolic pathway. This leads to increased collagen II and aggrecan expression, as well as reduced expression of MMPs. Ultimately, this prevents degradation of the cartilage ECM and promotes synthesis of important ECM molecules. (B) Piezo1-mediated Mechanotransduction of OA cartilage: under injurious loading (50% strain) or inflammatory activation via IL-1α, Ca2+ enters the cell through Piezo1 channels. Activation of Piezo1 channels also triggers voltage gated Ca2+ channel opening, resulting in excess Ca2+ concentrations in the chondrocyte, activating a catabolic pathway. This will result in enhanced PIEZO1 and MMP expression, increasing mechanosensitivity of chondrocytes to mechanical loading. (C) Proposed Mechano-therapeutics: GsMTx4, an inhibitor of Piezo1, prevents Ca2+ influx in response to Piezo1 activation under injurious loading, acting to protect the chondrocytes. Verapamil, a VGCC inhibitor, further regulates Ca2+ homeostasis by preventing excess Ca2+ influx through VGCCs that activate in addition to Piezo1 channels under abnormal loading. GSK101, an agonist of TRPV4, mediates an anabolic phenotype, resulting in reduced expression of degradative enzymes, like MMP, and enhanced expression of cartilage ECM components, like collagen II and aggrecan. Combined, these therapeutics can be used to promote an anabolic pathway, decrease ECM degradation, and prevent progression of the cartilage into an OA phenotype. (Figure created using BioRender.com).

TRPV4 has been noted as a possible sensor for excessive stress, resulting in chondrocyte apoptosis (Xu et al., 2019). However, the loading procedure performed in this study was direct stimulation (20% stretch) to the chondrocytes. As TRPV4 channels are usually activated by osmotic stresses, the difference in stimulation mode as well as the hyper-physiological strain on the chondrocytes may have caused cell death, a different effect than the usual anabolic pathway that TRPV4 mediates under physiologic loads.

In vivo experiments have also highlighted the essential role of TRPV4 channels for cartilage health and disease. Mice with cartilage-specific TRPV4-deletion in adulthood exhibit reduced severity of aging-associated OA compared to control mice; however, analysis following DMM injury show similar levels of cartilage degradation and OA severity between control and TRPV4-deficient mice (O'Conor et al., 2016). This suggests that age-related and post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PT-OA) are mediated through distinct pathways. As TRPV4 inhibition did not prevent the progression of OA after injury, it is not a suggested therapeutic strategy for PT-OA treatment (O'Conor et al., 2016). The reduced aging-OA phenotype in cartilage of TRPV4-deleted mice may be due to imbalanced matrix metabolism, or redundancy in the mechanotransduction pathways that may compensate for TRPV4-deletion (Servin-Vences et al., 2017). In short, these collective data demonstrate the essential roles of TRPV4 in cartilage maintenance and anabolism (O'Conor et al., 2014).

Piezo1/Piezo2-Mediated Mechanotransduction Under Injurious Loading

Piezo1 and Piezo2 channels are mammalian-expressing mechanosensitive cation channels discovered in 2010 that allow passage of Ca2+ into chondrocytes (Coste et al., 2010; Coste et al., 2012). Both Piezo1 and 2 channels are directly and rapidly activated by mechanical cues (τac_Piezo1 < 5 msec) with rapid subsequent inactivation time (τinac_Piezo1∼ 16 msec, τinac_Piezo2 ∼ 7 msec) (Coste et al., 2010). Yet, these channels have distinct gene expression patterns and are associated with different types of human diseases. Piezo1 is robustly expressed in mechanically stimulated tissues, including lung, colon, bladder, kidney, blood vessels, and in cells, including red blood cells, cardiac fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells (Xu et al., 2020). Activated by mechanical forces at the cell membrane, Piezo1 channels mediate responses in the cell, such as adjusting cell volume or remodeling host tissue, through activation of intracellular signaling pathways. Mutations in the Piezo1 channel are associated with lymphatic dysplasia and hemolytic anemia (Syeda et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2020). In contrast, Piezo2 channels are highly expressed in sensory systems, including proprioceptive mechanosensors and Merkel cells, controlling limb movement and touch sensation (Xu et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021). Mutations in Piezo2 lead to muscular atrophy, distal arthrogryposis, and scoliosis arthrogryposis (Anderson et al., 2017; Assaraf et al., 2020).

Articular chondrocytes express both Piezo1 and Piezo2 channels (Piezo1/2) robustly, and both channels are key mechanotransducers sensing injurious level (high-strain) mechanical loads (Lee et al., 2014; Du et al., 2020). Compression with a strain of ∼50% by atomic force microscopy (AFM) probes on isolated chondrocytes leads to a significant and prolonged intracellular Ca2+ influx with τinac_chondrocyte ∼ 16 s (not msec). These robust Ca2+ transients were diminished in chondrocytes with either Piezo1-knockdown or Piezo2-knockdown, as well as with GsMTx4 (an inhibitor of both Piezo1 and Piezo2) or verapamil [an inhibitor of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC)] treatment. These data suggest the synergistic action of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in transducing mechanical signals, and the role of VGCC in amplifying intracellular Ca2+ after Piezo1/2 activation (Figure 1B). The synergistic activation of Piezo1 and Piezo2 channels were further seen in heterologous cells with co-transfection of Piezo1 and Piezo2 under AFM-based compression or electrophysiology-based membrane stretch, but not in model cells with only-Piezo1 or only-Piezo2 transfections (Lee et al., 2014). The chondroprotective effect of Piezo1/2 inhibition using GsMTx4 was shown in a cartilage explant injury model, where porcine osteochondral explants were injured with a biopsy punch, resulting in chondrocyte damage at the area of injury. GsMTx4 pre-incubation of the explants was shown to decrease the “zone of death,” or damaged area, demonstrating GsMTx4’s effect of protecting chondrocytes from mechanical trauma via Piezo1/2 inhibition (Lee et al., 2014; Lawrence et al., 2017). GsMTx4 will be explored further as a potential therapeutic in a later section.

Role of Piezo1 in Inflammatory Signaling of Chondrocytes

Osteoarthritic joints and acutely injured joints exhibit significantly increased levels of interleukin-1 (IL-1) cytokines with enhanced inflammatory signaling in chondrocytes. Chondrocytes express functional IL-1 receptor (IL1R) and respond to both isoforms of IL-1α and IL-1β (Martel-Pelletier et al., 1992; McNulty et al., 2013). IL-1α-treatment increases Piezo1 preferentially, but not Piezo2 or TRPV4 channels, in primary articular chondrocytes. Chondrocytes in porcine and human OA cartilage also express 2-fold Piezo1 channels compared to healthy cartilage (Lee et al., 2021). Piezo1 augmentation further increases hyper-mechanosensitivity of chondrocytes in vitro (Figure 1B). AFM-based assay data reveal the increased Ca2+ influx from cyclic physiologic loading in IL-1α-treated or Yoda1 (a Piezo1-specific agonist) chondrocytes compared to controls, which in turn was diminished by co-treatment with Piezo1-siRNA or GsMTx4. These data suggest Piezo1’s role in the inflammatory response, disrupting Ca2+ homeostasis and increasing mechano-sensitivity of chondrocytes to mechanical loads.

Inflammation also affects the cytoskeleton, particularly filamentous actin (F-actin), as force transduction through F-actin is important in chondrocyte mechanotransduction (Wang et al., 1993; Haudenschild et al., 2008; Trompeter et al., 2021b; Dieterle et al., 2021). With exposure to IL-1α, F-actin of primary chondrocytes was reduced—an effect that was also seen in human OA cartilage samples. However, F-actin was restored with Piezo1 inhibition via GsMTx4 or Piezo1-targeting siRNA. Exposure to IL-1α also resulted in a decrease in cellular Young’s modulus, leading to increased cellular deformation with the same magnitude of mechanical loading compared to control samples. Inhibition of Piezo1 returned the cellular modulus and cell deformation to control levels. This shows that influx of Ca2+ through Piezo1 can affect cytoskeletal components including F-actin, resulting in a decrease in mechanical stiffness of the chondrocyte, increasing the likelihood of tissue degeneration. IL-1α-treatment also augmented Piezo1 via p38-MAPK signaling pathways and ATF2/CREBP1/HNF4 transcription factors (TFs). Testing of MAP-kinases downstream of IL1R showed that inhibition of p38-MAP kinase led to a decrease in Piezo1 mRNA expression with IL-1α exposure. Screening for TFs showed that inhibition of ATF2/CREBP1 and HNF4 attenuated Piezo1 mRNA expression in response to IL-1α.

Altogether, inflammatory cytokine IL-1α activates IL1R, where the signal is transduced by p38-MAPK, resulting in the activation of Piezo1 expression through TFs, ATF2/CREBP1 and HNF4. The increased expression of Piezo1 can result in increased Ca2+ influx, resulting in the loosening of the F-actin network (Lee et al., 2021). This can decrease cellular stiffness, and in turn decrease tissue stiffness, increasing the chance of developing an OA phenotype.

OA-Mediated Pain and the Role of Piezo2 in Joint Nociception

Piezo2 channels expressed in intra-articular sensory neurons have been studied in the context of nociception, mediating inflammation and nerve injury-induced sensitized mechanical pain or mechanical allodynia. Piezo2 expression is high in low threshold mechanoreceptors, likely contributing to their sensitivity to mechanically activated pain. Knockout of Piezo2 in mice impaired nociceptor firing, resulting in disrupted responses to noxious mechanical stimuli (Murthy et al., 2018). In a study by Szczot et al., Piezo2 mediated inflammation-induced pain in tactile allodynia. With Piezo2 knockout, mice failed to develop sensitization and pain in response to touch after skin inflammation, suggesting a possible role of Piezo2 in mediating pain sensation under inflammation (Szczot et al., 2018).

There has been ongoing investigation of the role of Piezo2 in OA mediated pain, however, the mechanism of this pain transduction pathway is not yet completely understood. Miller et al. studied pain reactions in mice with homozygous or heterozygous Piezo2 deletion in a DMM surgery-induced mouse OA model. In wild-type mice with intact Piezo2, knee hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia of the ipsilateral hind paw developed 4-weeks post-surgery. Less mechanical allodynia was seen with heterozygous deletion of Piezo2 4-weeks after DMM, however, knee hyperalgesia did not change compared to the mice with intact Piezo2. In mice with Piezo2 homozygous deletion, less knee hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia was seen in the hind paw at 4-weeks post-DMM surgery (Miller et al., 2019). In further study, it was shown that conditional knockout of Piezo2 in mice lead to attenuated nerve growth factor (NGF)-mediated knee swelling and mechanical pain (Obeidat et al., 2022). These data suggest an essential role of Piezo2 in mediating OA-associated joint nociceptor sensitization.

Current and Potential Mechano-Therapeutic Strategies

Current Therapeutic Strategies

The goal of OA therapeutics is to prevent progressive cartilage degeneration and joint dysfunction. OA therapeutics are urgently needed especially for younger patients who have a high risk for PT-OA a decade after joint injury (Anderson et al., 2011; Schenker et al., 2014; Krishnan and Grodzinsky, 2018; Eskelinen et al., 2020). Exercise and physical therapies are currently suggested after surgery to promote anabolism, presumably by targeting the TRPV4 ion channels. In addition to exercise, patients may receive intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid (HA) or corticosteroids, to increase cartilage lubrication or decrease local inflammation, respectively. HA is a GAGs found in the cartilage and synovial fluid, which provides the joint with lubrication and shock absorbance (Fusco et al., 2021). With OA progression, HA in the synovial fluid usually depolymerizes from high to low molecular weight, resulting in a decline in mechanical and viscoelastic properties of the joint. Exogenous injection of HA can promote synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins, proteoglycans, and/or GAGs, and have anti-inflammatory effects (Bowman et al., 2018). Usually used for short-term pain-relieving treatment, HA injection has shown to provide some pain relief, however, injections are expensive (Trigkilidas and Anand, 2013; Liu et al., 2018). Some patients also receive intra-articular injections of corticosteroids, which have immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects on the joint, blocking synthesis of pro-inflammatory molecules (IL-1) and catabolic proteins (MMPs). Patients with joint inflammation caused by OA benefit more with corticosteroid injection, compared with HA. However, corticosteroid treatment provides only temporary, short term pain relief (Ayhan et al., 2014; Fusco et al., 2021; Primorac et al., 2021).

The above therapies are limited in that they only control the symptoms of OA after disease onset and progression, and they are used as conservative therapies before the need for surgical intervention. Disease-modifying OA drugs (DMOAD) are currently being investigated with the goal to halt cartilage degradation, promote matrix regeneration, and reduce OA-mediated pain. This includes therapies aiming to inhibit MMPs, like MMP-13 and aggrecanases, to prevent the degradation of cartilage matrix that occurs in OA (Kurz et al., 2005; Chubinskaya et al., 2015). A clinical trial was conducted for MMP inhibitor PG-116800 to test its ability to delay cartilage destruction. PG-116800 has high affinity for MMP-2, -3, -8, -9, -13, and -14, and low affinity for MMP-1 and MMP-7. The trial was terminated due to a musculoskeletal toxicity side effect. There was also no significant difference in radiographic knee joint space between treatment and placebo groups, suggesting the therapy was ineffective in preventing degradation of cartilage. The major adverse effect seen was arthralgia. The investigators hypothesized that the musculoskeletal symptoms may have been due to MMP inhibitors ability to inhibit sheddase activity, which normally converts cytokines into inactive forms (Krzeski et al., 2007). Inhibition of this activity would then result in paradoxical inflammation. Another hypothesis made was that the toxicity was due to MMP-1 inhibition. Efforts to develop a selective compound to target inactivation of only MMP-13 are in progress, but results are forthcoming (Baragi et al., 2009; Vandenbroucke and Libert, 2014; Li et al., 2017).

Other therapies targeting inflammatory cytokines active in OA, like IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, have been studied as well (Jacques et al., 2006; Chubinskaya et al., 2015). Most of these therapeutics were originally developed for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and adapted to treat OA. However, these treatments were ultimately ineffective in preventing pain or cartilage degradation. An example is anakinra, an IL-1 receptor antagonist. Investigators attributed this lack of effectiveness due to the mode of treatment administration, a single intra-articular injection to the knee (Chevalier et al., 2009). Further studies are anticipated to investigate more long-lasting, potent IL-1 receptor antagonists (Jotanovic et al., 2012).

Senescent cells have also been targeted since these cells are accumulated in areas of cartilage degeneration in OA. Senescence has been shown to promote oxidative stress and inflammation in diseased cartilage (Vinatier et al., 2018). A senolytic molecule, UBX0101, was developed to remove these cells by inhibiting MDM2/p53 interactions, reducing the release of inflammatory factors and associated pain (Loeser, 2011; Collins et al., 2018; Hsu et al., 2019; Coryell et al., 2021). However, this trial of UBX0101 intra-articular injection was discontinued as it failed to meet week-12 primary endpoints, with no significant difference between treatment and placebo groups (Hsu et al., 2019; Grässel and Muschter, 2020).

Potential Therapy: GsMTx4 Peptide Therapy Targeting Piezo1

GsMTx4, a 34 amino acid peptide derived from tarantula venom, inhibits Piezo1 and Piezo2 channels (Bowman et al., 2007; Gottlieb et al., 2007; Copp et al., 2016; Alcaino et al., 2017). GsMTx4 anchors to the outer membrane surface by lysine residue at low tension. When the membrane is under tension, GsMTx4 is able to physically sink deeper into the membrane, leading to partial relaxation of the outer monolayer of the membrane. This disrupts the distribution of tension near mechanosensitive channels including Piezo1, causing a less efficient transfer of force from the bilayer to the channel without physical block of ion pore regions. The change in membrane tension creates a 30 mmHg rightward shift in the pressure-gating curve, making it harder for Piezo1 to open under mechanical stimulation (Bae et al., 2011; Gnanasambandam et al., 2017). GsMTx4 has been shown to be ineffective in inhibiting TRPV4 channels, demonstrated in juxtaglomerular cells, bladder urothelium, and endothelial cells (Seghers et al., 2016; Ihara et al., 2018; Swain and Liddle, 2021). In chondrocytes, GSK205 (a TRPV4 inhibitor) failed to inhibit Ca2+ influx under hyperphysiological loading, while GsMTx4 treatment did, further confirming GsMTx4’s ability to selectively inhibit Piezo channels. A possible mechanism as to why GsMTx4 is specific to Piezo may be due to the unique structure of these channels. Piezo channels have three curved, blade-like structures that widen from the base of the protein to the mechanosensing portion on the outer layer of the plasma membrane (Fang et al., 2021). This may allow GsMTx4 to embed closer to the Piezo channel and influence membrane tension more locally, effecting Piezo channel activation specifically.

The use of GsMTx4 has been studied in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). DMD is caused by genetic mutation resulting in a loss of dystrophin, which is linked to increased permeability of the sarcolemma to extracellular Ca2+. This leads to a decline in muscle mass due to increased Ca2+-dependent proteolysis and necrosis of muscle fibers. GsMTx4-D, an enantiomer of GsMTx4, was shown to decrease loss in muscle mass and improve the muscle’s functional capacity due to inhibiting mechanically stimulated channels like Piezo1 (Suchyna, 2017). Ward et al. studied the pharmacokinetics of GsMTx4 in mice. Through 50 mg/kg dose subcutaneous injection, GsMTx4 accumulation of 0.1–5 μM in skeletal muscle and heart was achieved within 24 h, a range shown to effectively limit MA channel activity. GsMTx4 also demonstrated long half-life in tissues, but rapid depletion in the blood, suggesting higher affinity of GsMTx4 for tissues than serum proteins. D-amino acid peptides are less prone to enzymatic degradation, which may contribute to GsMTx4-D’s long half-life. No apparent adverse effects or signs of toxicity were shown during the 6-weeks study in mice, although further study of long-term effects, particularly on growth and development, would be needed (Ward et al., 2018).

A cardio-protective effect was also seen with use of GsMTx4 in the context of cardiac ischemic reperfusion injury, which is often associated with an elevation of Ca2+ influx. Wang et al. showed that mice with intravenous injection of GsMTx4-D during an ischemic event or with subcutaneous injection prior to ischemic challenge show reduced infarct size, less arrhythmic activity, and increased cardiac output post ischemia. GsMTx4 treatment also improved heart contraction by restoring normal Ca2+ release and blocked apoptotic signaling to improve cardiomyocyte survival. Slowing of cation influx through ion channels with GsMTx4 during ischemia and reperfusion prevented cell swelling that occurs with cation overload. GsMTx4 was mostly active at pathological conditions, as there was little effect of the treatment on normally functioning controls (Wang et al., 2016).

In the context of OA, GsMTx4-treated cartilage demonstrates a chondroprotective effect in hyper-physiological loading by inhibiting Piezo1 and Piezo2 channels. Osteochondral cartilage explants with pre-incubation of GsMTx4 showed significantly decreased chondrocyte damage and death after biopsy punch injury (Lee et al., 2014). GsMTx4 was also shown to prevent inflammation-induced rarefication or loosening of F-actin, an important cytoskeleton component in chondrocyte mechanotransduction. Inhibition of the Piezo1 channel via GsMTx4 preserved the cellular modulus in the presence of IL-1α as well (Lee et al., 2021). To date, the effect of GsMTx4 in the context of articular cartilage injury has been studied in in vitro and ex vivo models. Moving forward, further study would be needed to see whether the chondroprotective effect translates to in vivo animal models and potential clinical use. Along with this, appropriate dosing for intra-articular injection of GsMTx4 would need to be determined, as well as any potential toxicities related to long term use of GsMTx4. Based on its application to treatment of other disease, GsMTx4 seems to be nontoxic and effective in treating pathologies related to Piezo1 channel dysfunction.

Potential Therapy: Verapamil Targeting VGCC

As an FDA-approved drug, verapamil has been used in the treatment of various cardiac conditions including angina, arrhythmias, and hypertension, with no major adverse effects observed (Brogden and Benfield, 1996; De Simone et al., 2003). A commonly prescribed L-type voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC) blocker, verapamil has also been studied as a therapeutic to attenuate Wnt/β-catenin signaling in OA (Matta et al., 2015; Vaiciuleviciute et al., 2021). The activation of β-catenin can induce hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes and upregulate ECM catabolic enzymes, leading to development of an OA-phenotype (De Santis et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019; Lories and Monteagudo, 2020). Verapamil is able to suppress Wnt/β-catenin signaling by enhancing FRZB gene expression, an antagonist of Wnt signaling, which leads to suppressed ECM degradation (lower MMP activity), enhanced gene expression of aggrecan and Col-II, and decreased hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes (lower type X collagen expression). In a study by Takamatsu et al., 50 μM of verapamil was delivered to rats intra-articularly after DMM, preventing progression of OA without apparent adverse effects, although long term use in clinical practice needs further investigation (Takamatsu et al., 2014).

In their investigation of chondrocytes, Lee et al. suggest that Piezo1 activation may lead to activation of VGCCs, amplifying intracellular Ca2+ signaling in response to injurious loading. Verapamil was shown to decrease the Ca2+ transients in response to injurious compression, suggesting that VGCCs may be activated in addition to Piezo1 with hyper-physiological loading, as opposed to Ca2+ movement via TRPV4 in response to hypo-osmotic stress (Lee et al., 2014; Nims et al., 2021). This may indicate a correlation between Piezo1, VGCCs and Wnt signaling which are all activate during injurious loading. Further study is needed to confirm Piezo1’s direct effect on Wnt signaling in chondrocytes.

Future Direction

Targeting OA-associated chondrocyte mechanotransduction shows promise as future therapeutics for OA. Based on current knowledge, OA therapeutic strategies would be to promote TRPV4-mediated cartilage anabolism and to inhibit Piezo1-mediated chondrocyte death and inflammatory feed-forward responses. These strategies may be achieved by administrations of GSK101, GsMTx4, and verapamil (Figure 1C). Intra-articular injections are suggested to specifically target tissues in synovial OA joints, reducing systemic side effects to other organ systems, in addition to increasing the drug’s bioavailability. The use of mechanoresponsive biomaterials can further control the delivery of drugs (Geiger et al., 2018). For example, nanoparticles containing these drugs may release its contents into the joint space over time, generating a sustained release. Release of a drug can also be controlled based on compressive, tensile, or shear forces applied to a hydrogel containing the drug. Specifically, in this application, a hydrogel may be tuned to release GsMTx4 under hyper-physiological loads (ex. >300 nM compression), thus, releasing the drug only as needed. This technology may increase the longevity of a single treatment and reduce overall treatment costs over time (Hodgkinson et al., 2021).

Conclusion

TRPV4-, Piezo1-, and Piezo2-mediated mechanotransduction mechanisms of chondrocytes play essential roles in cartilage regeneration and degeneration. Our understanding of the specific mechanosignalling pathways and downstream signals of these mechanosensitive Ca2+ channels yield potential safe and efficient OA treatments. Potential mechano-therapies include activating TRPV4-mediated mechanotransduction and inhibiting Piezo1-mediated mechanotransduction to promote cartilage anabolism and prevent cartilage catabolism or degradation. The continued advances in chondrocyte mechanobiology will lead to successful DMOADs with long-term safety to restore cartilage integrity for OA patients.

Author Contributions

WG, HH, DA, and WL were involved in drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alcaino, C., Knutson, K., Gottlieb, P. A., Farrugia, G., and Beyder, A. (2017). Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Piezo2 Is Inhibited by D-GsMTx4. Channels 11 (3), 245–253. doi:10.1080/19336950.2017.1279370

Alexopoulos, L. G., Haider, M. A., Vail, T. P., and Guilak, F. (2003). Alterations in the Mechanical Properties of the Human Chondrocyte Pericellular Matrix with Osteoarthritis. J. Biomech. Eng. 125 (3), 323–333. doi:10.1115/1.1579047

Alexopoulos, L. G., Setton, L. A., and Guilak, F. (2005). The Biomechanical Role of the Chondrocyte Pericellular Matrix in Articular Cartilage. Acta Biomater. 1 (3), 317–325. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2005.02.001

Anderson, D. D., Chubinskaya, S., Guilak, F., Martin, J. A., Oegema, T. R., Olson, S. A., et al. (2011). Post-traumatic Osteoarthritis: Improved Understanding and Opportunities for Early Intervention. J. Orthop. Res. 29 (6), 802–809. doi:10.1002/jor.21359

Anderson, E. O., Schneider, E. R., and Bagriantsev, S. N. (2017). Piezo2 in Cutaneous and Proprioceptive Mechanotransduction in Vertebrates a aThis Work Was Supported by Grants from National Science Foundation (1453167), National Institutes of Health (1R01NS097547-01A1) and American Heart Association (14SDG17880015) to S.N.B. E.R.S. Was Partially Supported by a Training Grant from National Institutes of Health T32HD007094 and a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation. E.O.A. Is a Fellow of the Gruber Foundation and an Edward L. Tatum Fellow. Correspondence Should Be Addressed to S.N.B (slav.bagriantsev@yale.Edu). Curr. Top. Membr. 79, 197–217. doi:10.1016/bs.ctm.2016.11.002

Ashwell, M. S., Gonda, M. G., Gray, K., Maltecca, C., O'Nan, A. T., Cassady, J. P., et al. (2013). Changes in Chondrocyte Gene Expression Following In Vitro Impaction of Porcine Articular Cartilage in an Impact Injury Model. J. Orthop. Res. 31 (3), 385–391. doi:10.1002/jor.22239

Assaraf, E., Blecher, R., Heinemann-Yerushalmi, L., Krief, S., Carmel Vinestock, R., Biton, I. E., et al. (2020). Piezo2 Expressed in Proprioceptive Neurons Is Essential for Skeletal Integrity. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 3168. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16971-6

Ayhan, E., Kesmezacar, H., and Akgun, I. (2014). Intraarticular Injections (Corticosteroid, Hyaluronic Acid, Platelet Rich Plasma) for the Knee Osteoarthritis. Wjo 5 (3), 351–361. doi:10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.351

Bae, C., Sachs, F., and Gottlieb, P. A. (2011). The Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Piezo1 Is Inhibited by the Peptide GsMTx4. Biochemistry 50 (29), 6295–6300. doi:10.1021/bi200770q

Baragi, V. M., Becher, G., Bendele, A. M., Biesinger, R., Bluhm, H., Boer, J., et al. (2009). A New Class of Potent Matrix Metalloproteinase 13 Inhibitors for Potential Treatment of Osteoarthritis: Evidence of Histologic and Clinical Efficacy without Musculoskeletal Toxicity in Rat Models. Arthritis Rheum. 60 (7), 2008–2018. doi:10.1002/art.24629

Barrett-Jolley, R., Lewis, R., Fallman, R., and Mobasheri, A. (2010). The Emerging Chondrocyte Channelome. Front. Physio. 1, 135. doi:10.3389/fphys.2010.00135

Blazek, A. D., Nam, J., Gupta, R., Pradhan, M., Perera, P., Weisleder, N. L., et al. (2016). Exercise-driven Metabolic Pathways in Healthy Cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 24 (7), 1210–1222. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2016.02.004

Bleuel, J., Zaucke, F., Brüggemann, G.-P., and Niehoff, A. (2015). Effects of Cyclic Tensile Strain on Chondrocyte Metabolism: a Systematic Review. PLoS One 10 (3), e0119816. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119816

Bonassar, L. J., Grodzinsky, A. J., Frank, E. H., Davila, S. G., Bhaktav, N. R., and Trippel, S. B. (2001). The Effect of Dynamic Compression on the Response of Articular Cartilage to Insulin-like Growth Factor-I. J. Orthop. Res. 19 (1), 11–17. doi:10.1016/s0736-0266(00)00004-8

Boschetti, F., and Peretti, G. M. (2008). Tensile and Compressive Properties of Healthy and Osteoarthritic Human Articular Cartilage. Biorheology 45 (3-4), 337–344. doi:10.3233/bir-2008-0479

Bowman, C. L., Gottlieb, P. A., Suchyna, T. M., Murphy, Y. K., and Sachs, F. (2007). Mechanosensitive Ion Channels and the Peptide Inhibitor GsMTx-4: History, Properties, Mechanisms and Pharmacology. Toxicon 49 (2), 249–270. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.030

Bowman, S., Awad, M. E., Hamrick, M. W., Hunter, M., and Fulzele, S. (2018). Recent Advances in Hyaluronic Acid Based Therapy for Osteoarthritis. Clin. Transl. Med. 7 (1), 6. doi:10.1186/s40169-017-0180-3

Brogden, R. N., and Benfield, P. (1996). Verapamil. Drugs 51 (5), 792–819. doi:10.2165/00003495-199651050-00007

Buckwalter, J. A., Mankin, H. J., and Grodzinsky, A. J. (2005). Articular Cartilage and Osteoarthritis. Instr. Course Lect. 54, 465–480.

Buckwalter, J., and Martin, J. (2006). Osteoarthritis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 58 (2), 150–167. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.006

Chahine, N. O., Albro, M. B., Lima, E. G., Wei, V. I., Dubois, C. R., Hung, C. T., et al. (2009). Effect of Dynamic Loading on the Transport of Solutes into Agarose Hydrogels. Biophysical J. 97 (4), 968–975. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.047

Chao, P.-h. G., West, A. C., and Hung, C. T. (2006). Chondrocyte Intracellular Calcium, Cytoskeletal Organization, and Gene Expression Responses to Dynamic Osmotic Loading. Am. J. Physiology-Cell Physiology 291 (4), C718–C725. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00127.2005

Chery, D. R., Han, B., Li, Q., Zhou, Y., Heo, S.-J., Kwok, B., et al. (2020). Early Changes in Cartilage Pericellular Matrix Micromechanobiology Portend the Onset of Post-traumatic Osteoarthritis. Acta Biomater. 111, 267–278. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2020.05.005

Chevalier, X., Goupille, P., Beaulieu, A. D., Burch, F. X., Bensen, W. G., Conrozier, T., et al. (2009). Intraarticular Injection of Anakinra in Osteoarthritis of the Knee: a Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Arthritis Rheum. 61 (3), 344–352. doi:10.1002/art.24096

Chubinskaya, S., Haudenschild, D., Gasser, S., Stannard, J., Krettek, C., and Borrelli, J. (2015). Articular Cartilage Injury and Potential Remedies. J. Orthop. Trauma 29 (Suppl. 12), S47–S52. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000462

Collins, J. A., Diekman, B. O., and Loeser, R. F. (2018). Targeting Aging for Disease Modification in Osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 30 (1), 101–107. doi:10.1097/bor.0000000000000456

Copp, S. W., Kim, J. S., Ruiz-Velasco, V., and Kaufman, M. P. (2016). The Mechano-Gated Channel Inhibitor GsMTx4 Reduces the Exercise Pressor Reflex in Decerebrate Rats. J. Physiol. 594 (3), 641–655. doi:10.1113/jp271714

Coryell, P. R., Diekman, B. O., and Loeser, R. F. (2021). Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications of Cellular Senescence in Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 17 (1), 47–57. doi:10.1038/s41584-020-00533-7

Coste, B., Mathur, J., Schmidt, M., Earley, T. J., Ranade, S., Petrus, M. J., et al. (2010). Piezo1 and Piezo2 Are Essential Components of Distinct Mechanically Activated Cation Channels. Science 330 (6000), 55–60. doi:10.1126/science.1193270

Coste, B., Xiao, B., Santos, J. S., Syeda, R., Grandl, J., Spencer, K. S., et al. (2012). Piezo Proteins Are Pore-Forming Subunits of Mechanically Activated Channels. Nature 483 (7388), 176–181. doi:10.1038/nature10812

De Santis, M., Di Matteo, B., Chisari, E., Cincinelli, G., Angele, P., Lattermann, C., et al. (2018). The Role of Wnt Pathway in the Pathogenesis of OA and its Potential Therapeutic Implications in the Field of Regenerative Medicine. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 7402947. doi:10.1155/2018/7402947

De Simone, A., De Pasquale, M., De Matteis, C., Michelangelo, C., Michele, M., Luigi, S., et al. (2003). VErapamil Plus Antiarrhythmic Drugs Reduce Atrial Fibrillation Recurrences after an Electrical Cardioversion (VEPARAF Study). Eur. Heart J. 24 (15), 1425–1429. doi:10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00311-7

Delco, M. L., and Bonassar, L. J. (2021). Targeting Calcium-Related Mechanotransduction in Early OA. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 17 (8), 445–446. doi:10.1038/s41584-021-00649-4

Dieterle, M. P., Husari, A., Rolauffs, B., Steinberg, T., and Tomakidi, P. (2021). Integrins, Cadherins and Channels in Cartilage Mechanotransduction: Perspectives for Future Regeneration Strategies. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 23, e14. doi:10.1017/erm.2021.16

Du, G., Chen, W., Li, L., and Zhang, Q. (2021). The Potential Role of Mechanosensitive Ion Channels in Substrate Stiffness-Regulated Ca2+ Response in Chondrocytes. Connect. Tissue Res., 1–10. doi:10.1080/03008207.2021.2007902

Du, G., Li, L., Zhang, X., Liu, J., Hao, J., Zhu, J., et al. (2020). Roles of TRPV4 and Piezo Channels in Stretch-Evoked Ca2+ Response in Chondrocytes. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 245 (3), 180–189. doi:10.1177/1535370219892601

Erickson, G. R., Alexopoulos, L. G., and Guilak, F. (2001). Hyper-osmotic Stress Induces Volume Change and Calcium Transients in Chondrocytes by Transmembrane, Phospholipid, and G-Protein Pathways. J. Biomechanics 34 (12), 1527–1535. doi:10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00156-7

Eskelinen, A. S. A., Tanska, P., Florea, C., Orozco, G. A., Julkunen, P., Grodzinsky, A. J., et al. (2020). Mechanobiological Model for Simulation of Injured Cartilage Degradation via Pro-inflammatory Cytokines and Mechanical Stimulus. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16 (6), e1007998. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007998

Evans, R. C., and Quinn, T. M. (2006). Dynamic Compression Augments Interstitial Transport of a Glucose-like Solute in Articular Cartilage. Biophysical J. 91 (4), 1541–1547. doi:10.1529/biophysj.105.080366

Evans, R. C., and Quinn, T. M. (2006). Solute Convection in Dynamically Compressed Cartilage. J. Biomechanics 39 (6), 1048–1055. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.017

Fang, X.-Z., Zhou, T., Xu, J.-Q., Wang, Y.-X., Sun, M.-M., He, Y.-J., et al. (2021). Structure, Kinetic Properties and Biological Function of Mechanosensitive Piezo Channels. Cell Biosci. 11 (1), 13. doi:10.1186/s13578-020-00522-z

Fodor, J., Matta, C., Oláh, T., Juhász, T., Takács, R., Tóth, A., et al. (2013). Store-operated Calcium Entry and Calcium Influx via Voltage-Operated Calcium Channels Regulate Intracellular Calcium Oscillations in Chondrogenic Cells. Cell Calcium 54 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2013.03.003

Fu, S., Meng, H., Inamdar, S., Das, B., Gupta, H., Wang, W., et al. (2021). Activation of TRPV4 by Mechanical, Osmotic or Pharmaceutical Stimulation Is Anti-inflammatory Blocking IL-1β Mediated Articular Cartilage Matrix Destruction. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 29 (1), 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2020.08.002

Fukui, T., Tenborg, E., Yik, J. H. N., and Haudenschild, D. R. (2015). In-vitro and In-Vivo Imaging of MMP Activity in Cartilage and Joint Injury. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 460 (3), 741–746. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.03.100

Fusco, G., Gambaro, F. M., Di Matteo, B., and Kon, E. (2021). Injections in the Osteoarthritic Knee: a Review of Current Treatment Options. EFORT Open Rev. 6 (6), 501–509. doi:10.1302/2058-5241.6.210026

Geiger, B. C., Wang, S., Padera, R. F., Grodzinsky, A. J., and Hammond, P. T. (2018). Cartilage-penetrating Nanocarriers Improve Delivery and Efficacy of Growth Factor Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 10 (469). doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aat8800

Gnanasambandam, R., Ghatak, C., Yasmann, A., Nishizawa, K., Sachs, F., Ladokhin, A. S., et al. (2017). GsMTx4: Mechanism of Inhibiting Mechanosensitive Ion Channels. Biophysical J. 112 (1), 31–45. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2016.11.013

Goldring, M. B., and Marcu, K. B. (2009). Cartilage Homeostasis in Health and Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Res. Ther. 11 (3), 224. doi:10.1186/ar2592

Gong, X., Xie, W., Wang, B., Gu, L., Wang, F., Ren, X., et al. (2017). Altered Spontaneous Calcium Signaling of In Situ Chondrocytes in Human Osteoarthritic Cartilage. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 17093. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-17172-w

Gottlieb, P. A., Suchyna, T. M., and Sachs, F. (2007). “Properties and Mechanism of the Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Inhibitor GsMTx4, a Therapeutic Peptide Derived from Tarantula Venom,” in Current Topics in Membranes. Editor O. P. Hamill (Academic Press), 81–109. doi:10.1016/s1063-5823(06)59004-0

Grässel, S., and Muschter, D. (2020). Recent Advances in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. F1000Res 9. doi:10.12688/f1000research.22115.1

Griffin, T. M., and Guilak, F. (2005). The Role of Mechanical Loading in the Onset and Progression of Osteoarthritis. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 33 (4), 195–200. doi:10.1097/00003677-200510000-00008

Grodzinsky, A. J., Levenston, M. E., Jin, M., and Frank, E. H. (2000). Cartilage Tissue Remodeling in Response to Mechanical Forces. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2, 691–713. doi:10.1146/annurev.bioeng.2.1.691

Guilak, F. (2011). Biomechanical Factors in Osteoarthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatology 25 (6), 815–823. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.11.013

Guilak, F., Nims, R. J., Dicks, A., Wu, C.-L., and Meulenbelt, I. (2018). Osteoarthritis as a Disease of the Cartilage Pericellular Matrix. Matrix Biol. 71-72, 40–50. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2018.05.008

Guilak, F., Zell, R. A., Erickson, G. R., Grande, D. A., Rubin, C. T., McLeod, K. J., et al. (1999). Mechanically Induced Calcium Waves in Articular Chondrocytes Are Inhibited by Gadolinium and Amiloride. J. Orthop. Res. 17 (3), 421–429. doi:10.1002/jor.1100170319

Han, L., Grodzinsky, A. J., and Ortiz, C. (2011). Nanomechanics of the Cartilage Extracellular Matrix. Annu. Rev. Mat. Res. 41, 133–168. doi:10.1146/annurev-matsci-062910-100431

Hattori, K., Takahashi, N., Terabe, K., Ohashi, Y., Kishimoto, K., Yokota, Y., et al. (2021). Activation of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 Protects Articular Cartilage against Inflammatory Responses via CaMKK/AMPK/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 15508. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-94938-3

Haudenschild, D. R., D'Lima, D. D., and Lotz, M. K. (2008). Dynamic Compression of Chondrocytes Induces a Rho Kinase-dependent Reorganization of the Actin Cytoskeleton. Biorheology 45, 219–228. doi:10.3233/bir-2008-0499

Héraud, F., Héraud, A., and Harmand, M. F. (2000). Apoptosis in Normal and Osteoarthritic Human Articular Cartilage. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59 (12), 959–965. doi:10.1136/ard.59.12.959

Hodgkinson, T., Kelly, D. C., Curtin, C. M., and O’Brien, F. J. (2021). Mechanosignalling in Cartilage: an Emerging Target for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 18, 67–84. doi:10.1038/s41584-021-00724-w

Holloway, I., Kayser, M., Lee, D. A., Bader, D. L., Bentley, G., and Knight, M. M. (2004). Increased Presence of Cells with Multiple Elongated Processes in Osteoarthritic Femoral Head Cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 12 (1), 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.001

Hsu, B., Jennifer, V., Mark, G., Kimberly, W., Mahru, A., Remi-Martin, L., et al. (2019). Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Clinical Outcomes Following Single-Dose IA Administration of UBX0101, a Senolytic MDM2/p53 Interaction Inhibitor, in Patients with Knee OA. Hoboken, New Jersey: Arthritis Rheumatol John Wiley & Sons, 71.

Ihara, T., Mitsui, T., Nakamura, Y., Kanda, M., Tsuchiya, S., Kira, S., et al. (2018). The Oscillation of Intracellular Ca2+ Influx Associated with the Circadian Expression of Piezo1 and TRPV4 in the Bladder Urothelium. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 5699. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-23115-w

Jacques, C., Gosset, M., Berenbaum, F., and Gabay, C. (2006). The Role of IL‐1 and IL‐1Ra in Joint Inflammation and Cartilage Degradation. Vitam. Horm. 74, 371–403. doi:10.1016/s0083-6729(06)74016-x

Jotanovic, Z., Mihelic, R., Sestan, B., and Dembic, Z. (2012). Role of Interleukin-1 Inhibitors in Osteoarthritis. Drugs & Aging 29 (5), 343–358. doi:10.2165/11599350-000000000-00000

Kloppenburg, M., and Berenbaum, F. (2020). Osteoarthritis Year in Review 2019: Epidemiology and Therapy. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 28 (3), 242–248. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2020.01.002

Korhonen, R. K., and Herzog, W. (2008). Depth-dependent Analysis of the Role of Collagen Fibrils, Fixed Charges and Fluid in the Pericellular Matrix of Articular Cartilage on Chondrocyte Mechanics. J. Biomechanics 41 (2), 480–485. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.09.002

Krishnan, Y., and Grodzinsky, A. J. (2018). Cartilage Diseases. Matrix Biol. 71-72, 51–69. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2018.05.005

Krzeski, P., Buckland-Wright, C., Bálint, G., Cline, G. A., Stoner, K., Lyon, R., et al. (2007). Development of Musculoskeletal Toxicity without Clear Benefit after Administration of PG-116800, a Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitor, to Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: a Randomized, 12-month, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 9 (5), R109. doi:10.1186/ar2315

Kurz, B., Lemke, A. K., Fay, J., Pufe, T., Grodzinsky, A. J., and Schünke, M. (2005). Pathomechanisms of Cartilage Destruction by Mechanical Injury. Ann. Anat. 187 (5), 473–485. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2005.07.003

Lark, M. W., Bayne, E. K., and Lohmander, L. S. (1995). Aggrecan Degradation in Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Acta Orthop. Scand. 66, 92–97. doi:10.3109/17453679509157660

Lawrence, K. M., Jones, R. C., Jackson, T. R., Baylie, R. L., Abbott, B., Bruhn-Olszewska, B., et al. (2017). Chondroprotection by Urocortin Involves Blockade of the Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Piezo1. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 5147. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04367-4

Lawrence, R. C., Felson, D. T., Helmick, C. G., Arnold, L. M., Choi, H., Deyo, R. A., et al. (2008). Estimates of the Prevalence of Arthritis and Other Rheumatic Conditions in the United States: Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 58 (1), 26–35. doi:10.1002/art.23176

Lee, H. S., Millward-Sadler, S. J., Wright, M. O., Nuki, G., and Salter, D. M. (2000). Integrin and Mechanosensitive Ion Channel-dependent Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Focal Adhesion Proteins and β-Catenin in Human Articular Chondrocytes after Mechanical Stimulation. J. Bone Min. Res. 15 (8), 1501–1509. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.8.1501

Lee, W., Leddy, H. A., Chen, Y., Lee, S. H., Zelenski, N. A., McNulty, A. L., et al. (2014). Synergy between Piezo1 and Piezo2 Channels Confers High-Strain Mechanosensitivity to Articular Cartilage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111 (47), E5114–E5122. doi:10.1073/pnas.1414298111

Lee, W., Nims, R. J., Savadipour, A., Zhang, Q., Leddy, H. A., Liu, F., et al. (2021). Inflammatory Signaling Sensitizes Piezo1 Mechanotransduction in Articular Chondrocytes as a Pathogenic Feed-Forward Mechanism in Osteoarthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118 (13). doi:10.1073/pnas.2001611118

Leong, D. J., Hardin, J. A., Cobelli, N. J., and Sun, H. B. (2011). Mechanotransduction and Cartilage Integrity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1240, 32–37. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06301.x

Li, H., Wang, D., Yuan, Y., and Min, J. (2017). New Insights on the MMP-13 Regulatory Network in the Pathogenesis of Early Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 19 (1), 248. doi:10.1186/s13075-017-1454-2

Liu, S.-H., Dubé, C. E., Eaton, C. B., Driban, J. B., McAlindon, T. E., and Lapane, K. L. (2018). Longterm Effectiveness of Intraarticular Injections on Patient-Reported Symptoms in Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Rheumatol. 45 (9), 1316–1324. doi:10.3899/jrheum.171385

Loeser, R. F. (2011). Aging and Osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 23 (5), 492–496. doi:10.1097/bor.0b013e3283494005

Lories, R. J., and Monteagudo, S. (2020). Review Article: Is Wnt Signaling an Attractive Target for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis? Rheumatol. Ther. 7 (2), 259–270. doi:10.1007/s40744-020-00205-8

Lv, M., Zhou, Y., Chen, X., Han, L., Wang, L., and Lu, X. L. (2018). Calcium Signaling of In Situ Chondrocytes in Articular Cartilage under Compressive Loading: Roles of Calcium Sources and Cell Membrane Ion Channels. J. Orthop. Res. 36 (2), 730–738. doi:10.1002/jor.23768

Maier, F., Lewis, C. G., and Pierce, D. M. (2019). The Evolving Large-Strain Shear Responses of Progressively Osteoarthritic Human Cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 27 (5), 810–822. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2018.12.025

Mardones, R., Jofré, C. M., and Minguell, J. J. (2015). Cell Therapy and Tissue Engineering Approaches for Cartilage Repair And/or Regeneration. Ijsc 8 (1), 48–53. doi:10.15283/ijsc.2015.8.1.48

Martel-Pelletier, J., Mccollum, R., Dibattista, J., Faure, M.-P., Chin, J. A., Fournier, S., et al. (1992). The Interleukin-1 Receptor in Normal and Osteoarthritic Human Articular Chondrocytes. Identification as the Type I Receptor and Analysis of Binding Kinetics and Biologic Function. Arthritis & Rheumatism 35 (5), 530–540. doi:10.1002/art.1780350507

Matta, C., Zákány, R., and Mobasheri, A. (2015). Voltage-Dependent Calcium Channels in Chondrocytes: Roles in Health and Disease. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 17 (7), 43. doi:10.1007/s11926-015-0521-4

Mauck, R. L., Nicoll, S. B., Seyhan, S. L., Ateshian, G. A., and Hung, C. T. (2003). Synergistic Action of Growth Factors and Dynamic Loading for Articular Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. 9 (4), 597–611. doi:10.1089/107632703768247304

McCutchen, C. N., Zignego, D. L., and June, R. K. (2017). Metabolic Responses Induced by Compression of Chondrocytes in Variable-Stiffness Microenvironments. J. biomechanics 64, 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.08.032

McNulty, A. L., Rothfusz, N. E., Leddy, H. A., and Guilak, F. (2013). Synovial Fluid Concentrations and Relative Potency of Interleukin-1 Alpha and Beta in Cartilage and Meniscus Degradation. J. Orthop. Res. 31 (7), 1039–1045. doi:10.1002/jor.22334

Michael, J. W.-P., Schlüter-Brust, K. U., and Eysel, P. (2010). The Epidemiology, Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 107 (9), 152–162. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0152

Mieloch, A. A., Richter, M., Trzeciak, T., Giersig, M., and Rybka, J. D. (2019). Osteoarthritis Severely Decreases the Elasticity and Hardness of Knee Joint Cartilage: A Nanoindentation Study. J. Clin. Med. 8 (11). doi:10.3390/jcm8111865

Miller, R. E., Ishihara, S., and Malfait, A.-M. (2019). The Ion Channel Piezo2 Plays a Role in Early Pain Behaviors Following DMM Surgery in Mice. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 27, S74. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2019.02.104

Mobasheri, A., Matta, C., Uzielienè, I., Budd, E., Martín-Vasallo, P., and Bernotiene, E. (2019). The Chondrocyte Channelome: A Narrative Review. Jt. Bone Spine 86 (1), 29–35. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2018.01.012

Mow, V. C., Bachrach, N. M., Setton, L. A., and Guilak, F. (1994). “Stress, Strain, Pressure and Flow Fields in Articular Cartilage and Chondrocytes,” in Cell Mechanics and Cellular Engineering (Springer), 345–379.

Muckelt, P. E., Roos, E. M., Stokes, M., McDonough, S., Grønne, D. T., Ewings, S., et al. (2020). Comorbidities and Their Link with Individual Health Status: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of 23,892 People with Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis from Primary Care. J. Comorb 10, 2235042x20920456. doi:10.1177/2235042X20920456

Muramatsu, S., Wakabayashi, M., Ohno, T., Amano, K., Ooishi, R., Sugahara, T., et al. (2007). Functional Gene Screening System Identified TRPV4 as a Regulator of Chondrogenic Differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 282 (44), 32158–32167. doi:10.1074/jbc.m706158200

Murthy, S. E., Loud, M. C., Daou, I., Marshall, K. L., Schwaller, F., Kühnemund, J., et al. (2018). The Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Piezo2 Mediates Sensitivity to Mechanical Pain in Mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 10 (462). doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aat9897

Ng, K. W., Mauck, R. L., Wang, C. C.-B., Kelly, T.-A. N., Ho, M. M.-Y., Chen, F. H., et al. (2009). Duty Cycle of Deformational Loading Influences the Growth of Engineered Articular Cartilage. Cel. Mol. Bioeng. 2 (3), 386–394. doi:10.1007/s12195-009-0070-x

Nguyen, C., Lieberherr, M., Bordat, C., Velard, F., Côme, D., Lioté, F., et al. (2012). Intracellular Calcium Oscillations in Articular Chondrocytes Induced by Basic Calcium Phosphate Crystals Lead to Cartilage Degradation. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 20 (11), 1399–1408. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2012.07.017

Nilius, B., Watanabe, H., and Vriens, J. (2003). The TRPV4 Channel: Structure-Function Relationship and Promiscuous Gating Behaviour. Pflugers Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 446 (3), 298–303. doi:10.1007/s00424-003-1028-9

Nims, R. J., Pferdehirt, L., Ho, N. B., Savadipour, A., Lorentz, J., Sohi, S., et al. (2021). A Synthetic Mechanogenetic Gene Circuit for Autonomous Drug Delivery in Engineered Tissues. Sci. Adv. 7 (5), eabd9858. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd9858

O'Conor, C. J., Leddy, H. A., Benefield, H. C., Liedtke, W. B., and Guilak, F. (2014). TRPV4-mediated Mechanotransduction Regulates the Metabolic Response of Chondrocytes to Dynamic Loading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111 (4), 1316–1321. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319569111

O'Conor, C. J., Ramalingam, S., Zelenski, N. A., Benefield, H. C., Rigo, I., Little, D., et al. (2016). Cartilage-Specific Knockout of the Mechanosensory Ion Channel TRPV4 Decreases Age-Related Osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 6, 29053. doi:10.1038/srep29053

Obeidat, A. M., Wood, M. J., Ishihara, S., Li, J., Wang, L., Ren, D., et al. (2022). Piezo2 Expressing Nociceptors Mediate Mechanical Sensitization in Experimental Osteoarthritis. NY, USA: bioRxiv Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. doi:10.1101/2022.03.12.484097

Oo, W. M., Little, C., Duong, V., and Hunter, D. J. (2021). The Development of Disease-Modifying Therapies for Osteoarthritis (DMOADs): The Evidence to Date. Dddt Vol. 15, 2921–2945. doi:10.2147/dddt.s295224

Primorac, D., Molnar, V., Matišić, V., Hudetz, D., Jeleč, Ž., Rod, E., et al. (2021). Comprehensive Review of Knee Osteoarthritis Pharmacological Treatment and the Latest Professional Societies' Guidelines. Pharm. (Basel) 14 (3). doi:10.3390/ph14030205

Quinn, T. M., Maung, A. A., Grodzinsky, A. J., Hunziker, E. B., and Sandy, J. D. (1999). Physical and Biological Regulation of Proteoglycan Turnover Around Chondrocytes in Cartilage Explants: Implications for Tissue Degradation and Repair. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 878, 420–441. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07700.x

Quinn, T. M., Morel, V., and Meister, J. J. (2001). Static Compression of Articular Cartilage Can Reduce Solute Diffusivity and Partitioning: Implications for the Chondrocyte Biological Response. J. Biomechanics 34 (11), 1463–1469. doi:10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00112-9

Sánchez, J. C., and López-Zapata, D. F. (2015). Effects of Adipokines and Insulin on Intracellular pH, Calcium Concentration, and Responses to Hypo-Osmolarity in Human Articular Chondrocytes from Healthy and Osteoarthritic Cartilage. Cartilage 6 (1), 45–54. doi:10.1177/1947603514553095

Sánchez, J. C., López-Zapata, D. F., and Wilkins, R. J. (2014). TRPV4 Channels Activity in Bovine Articular Chondrocytes: Regulation by Obesity-Associated Mediators. Cell Calcium 56 (6), 493–503. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2014.10.006

Sanchez-Adams, J., and Athanasiou, K. A. (2011). “Biomechanical Characterization of Single Chondrocytes,” in Cellular and Biomolecular Mechanics and Mechanobiology. Editor A. Gefen (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg), 247–266.

Sanchez-Adams, J., Leddy, H. A., McNulty, A. L., O’Conor, C. J., and Guilak, F. (2014). The Mechanobiology of Articular Cartilage: Bearing the Burden of Osteoarthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 16 (10), 451. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0451-6

Savadipour, A., Nims, R. J., Katz, D. B., and Guilak, F. (2022). Regulation of Chondrocyte Biosynthetic Activity by Dynamic Hydrostatic Pressure: the Role of TRP Channels. Connect. Tissue Res. 63 (1), 69–81. doi:10.1080/03008207.2020.1871475

Schenker, M. L., Mauck, R. L., Ahn, J., and Mehta, S. (2014). Pathogenesis and Prevention of Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis after Intra-articular Fracture. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 22 (1), 20–28. doi:10.5435/jaaos-22-01-20

Seghers, F., Yerna, X., Zanou, N., Devuyst, O., Vennekens, R., Nilius, B., et al. (2016). TRPV4 Participates in Pressure-Induced Inhibition of Renin Secretion by Juxtaglomerular Cells. J. Physiol. 594 (24), 7327–7340. doi:10.1113/jp273595

Servin-Vences, M. R., Moroni, M., Lewin, G. R., and Poole, K. (2017). Direct Measurement of TRPV4 and PIEZO1 Activity Reveals Multiple Mechanotransduction Pathways in Chondrocytes. Elife 6. doi:10.7554/eLife.21074

Shen, X., Liqiu, H., Zhen, L., Liyun, W., Xiangchao, P., Chun-Yi, W., et al. (2021). Extracellular Calcium Ion Concentration Regulates Chondrocyte Elastic Modulus and Adhesion Behavior. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (18). doi:10.3390/ijms221810034

Suchyna, T. M. (2017). Piezo Channels and GsMTx4: Two Milestones in Our Understanding of Excitatory Mechanosensitive Channels and Their Role in Pathology. Prog. Biophysics Mol. Biol. 130 (Pt B), 244–253. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2017.07.011

Suri, P., Morgenroth, D. C., and Hunter, D. J. (2012). Epidemiology of Osteoarthritis and Associated Comorbidities. PM&R 4 (5 Suppl. l), S10–S19. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.01.007

Suzuki, Y., Yamamura, H., Imaizumi, Y., Clark, R. B., and Giles, W. R. (2020). K+ and Ca2+ Channels Regulate Ca2+ Signaling in Chondrocytes: An Illustrated Review. Cells 9 (7), 1577. doi:10.3390/cells9071577

Swain, S. M., and Liddle, R. A. (2021). Piezo1 Acts Upstream of TRPV4 to Induce Pathological Changes in Endothelial Cells Due to Shear Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100171. doi:10.1074/jbc.ra120.015059

Syeda, R., Xu, J., Dubin, A. E., Coste, B., Mathur, J., Huynh, T., et al. (2015). Chemical Activation of the Mechanotransduction Channel Piezo1. Elife 4. doi:10.7554/elife.07369

Szczot, M., Liljencrantz, J., Ghitani, N., Barik, A., Lam, R., Thompson, J. H., et al. (2018). PIEZO2 Mediates Injury-Induced Tactile Pain in Mice and Humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 10 (462). doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aat9892

Takamatsu, A., Ohkawara, B., Ito, M., Masuda, A., Sakai, T., Ishiguro, N., et al. (2014). Verapamil Protects against Cartilage Degradation in Osteoarthritis by Inhibiting Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. PLoS One 9 (3), e92699. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092699

Torzilli, P. A., Bhargava, M., and Chen, C. T. (2011). Mechanical Loading of Articular Cartilage Reduces IL-1-Induced Enzyme Expression. Cartilage 2 (4), 364–373. doi:10.1177/1947603511407484

Trigkilidas, D., and Anand, A. (2013). The Effectiveness of Hyaluronic Acid Intra-articular Injections in Managing Osteoarthritic Knee Pain. annals 95 (8), 545–551. doi:10.1308/rcsann.2013.95.8.545

Trompeter, N., Farino, C. J., Griffin, M., Skinner, R., Banda, O. A., Gleghorn, J. P., et al. (2021). Extracellular Matrix Stiffness Alters TRPV4 Regulation in Chondrocytes. NY, USA: bioRxiv Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, doi:10.1101/2021.09.14.460172

Trompeter, N., Gardinier, J. D., DeBarros, V., Boggs, M., Gangadharan, V., Cain, W. J., et al. (2021). Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Regulates the Mechanosensitivity of Chondrocytes by Modulating TRPV4. Cell Calcium 99, 102467. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2021.102467

Vaiciuleviciute, R., Bironaite, D., Uzieliene, I., Mobasheri, A., and Bernotiene, E. (2021). Cardiovascular Drugs and Osteoarthritis: Effects of Targeting Ion Channels. Cells 10 (10). doi:10.3390/cells10102572

Vandenbroucke, R. E., and Libert, C. (2014). Is There New Hope for Therapeutic Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibition? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13 (12), 904–927. doi:10.1038/nrd4390

Vinatier, C., Domínguez, E., Guicheux, J., and Caramés, B. (2018). Role of the Inflammation-Autophagy-Senescence Integrative Network in Osteoarthritis. Front. Physiol. 9, 706. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00706

Wang, J., Ma, Y., Sachs, F., Li, J., and Suchyna, T. M. (2016). GsMTx4-D Is a Cardioprotectant against Myocardial Infarction during Ischemia and Reperfusion. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 98, 83–94. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.07.005

Wang, N., Butler, J. P., and Ingber, D. E. (1993). Mechanotransduction across the Cell Surface and through the Cytoskeleton. Science 260 (5111), 1124–1127. doi:10.1126/science.7684161

Wang, Y., Fan, X., Xing, L., and Tian, F. (2019). Wnt Signaling: a Promising Target for Osteoarthritis Therapy. Cell Commun. Signal 17 (1), 97. doi:10.1186/s12964-019-0411-x

Ward, C. W., Sachs, F., Bush, E. D., and Suchyna, T. M. (2018). GsMTx4-D Provides Protection to the D2.Mdx Mouse. Neuromuscul. Disord. 28 (10), 868–877. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2018.07.005

Wilkins, R. J., Fairfax, T. P., Davies, M. E., Muzyamba, M. C., and Gibson, J. S. (2003). Homeostasis of Intracellular Ca2+ in Equine Chondrocytes: Response to Hypotonic Shock. Equine Vet. J. 35 (5), 439–443. doi:10.2746/042516403775600541

Wilusz, R. E., Sanchez-Adams, J., and Guilak, F. (2014). The Structure and Function of the Pericellular Matrix of Articular Cartilage. Matrix Biol. 39, 25–32. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2014.08.009

Wilusz, R. E., Zauscher, S., and Guilak, F. (2013). Micromechanical Mapping of Early Osteoarthritic Changes in the Pericellular Matrix of Human Articular Cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 21 (12), 1895–1903. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2013.08.026

Wong, B. L., Bae, W. C., Chun, J., Gratz, K. R., Lotz, M., and Sah, R. L. (2008). Biomechanics of Cartilage Articulation: Effects of Lubrication and Degeneration on Shear Deformation. Arthritis Rheum. 58 (7), 2065–2074. doi:10.1002/art.23548

Wong, M., Siegrist, M., and Cao, X. (1999). Cyclic Compression of Articular Cartilage Explants Is Associated with Progressive Consolidation and Altered Expression Pattern of Extracellular Matrix Proteins. Matrix Biol. 18 (4), 391–399. doi:10.1016/s0945-053x(99)00029-3

Wuest, S., Caliò, M., Wernas, T., Tanner, S., Giger-Lange, C., Wyss, F., et al. (2018). Influence of Mechanical Unloading on Articular Chondrocyte Dedifferentiation. Ijms 19 (5), 1289. doi:10.3390/ijms19051289

Xu, B., Xing, R., Huang, Z., Yin, S., Li, X., Zhang, L., et al. (2019). Excessive Mechanical Stress Induces Chondrocyte Apoptosis through TRPV4 in an Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Transected Rat Osteoarthritis Model. Life Sci. 228, 158–166. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2019.05.003

Xu, B. Y., Jin, Y., Ma, X. H., Wang, C. Y., Guo, Y., and Zhou, D. (2020). The Potential Role of Mechanically Sensitive Ion Channels in the Physiology, Injury, and Repair of Articular Cartilage. J. Orthop. Surg. Hong. Kong) 28 (3), 2309499020950262. doi:10.1177/2309499020950262

Yellowley, C. E., Jacobs, C. R., Li, Z., Zhou, Z., and Donahue, H. J. (1997). Effects of Fluid Flow on Intracellular Calcium in Bovine Articular Chondrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 273 (1 Pt 1), C30–C36. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C30

Yunus, M. H. M., Nordin, A., and Kamal, H. (2020). Pathophysiological Perspective of Osteoarthritis. Med. Kaunas. 56 (11). doi:10.3390/medicina56110614

Zhang, K., Wang, L., Liu, Z., Geng, B., Teng, Y., Liu, X., et al. (2021). Mechanosensory and Mechanotransductive Processes Mediated by Ion Channels in Articular Chondrocytes: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Osteoarthritis. Channels 15 (1), 339–359. doi:10.1080/19336950.2021.1903184

Keywords: chondrocyte, mechanotransduction, osteoarthritis, mechanically-activated calcium channels, Piezo1, Piezo2, TRPV4, mechano-therapeutics

Citation: Gao W, Hasan H, Anderson DE and Lee W (2022) The Role of Mechanically-Activated Ion Channels Piezo1, Piezo2, and TRPV4 in Chondrocyte Mechanotransduction and Mechano-Therapeutics for Osteoarthritis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10:885224. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.885224

Received: 27 February 2022; Accepted: 20 April 2022;

Published: 04 May 2022.

Edited by:

Albrecht Schwab, University of Münster, GermanyReviewed by:

Jormay Lim, National Taiwan University, TaiwanCsaba Matta, University of Debrecen, Hungary

Copyright © 2022 Gao, Hasan, Anderson and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Whasil Lee, d2hhc2lsX2xlZUB1cm1jLnJvY2hlc3Rlci5lZHU=

Winni Gao

Winni Gao Hamza Hasan2

Hamza Hasan2 Devon E. Anderson

Devon E. Anderson Whasil Lee

Whasil Lee