- 1Center for Reproductive Medicine, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 2National Research Center for Assisted Reproductive Technology and Reproductive Genetics, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Reproductive Endocrinology of Ministry of Education, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 4Shandong Provincial Clinical Medicine Research Center for Reproductive Health, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 5Reproductive Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan, China

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is defined as depletion of ovarian function before 40 years of age, which affects 3.7% of women in reproductive age. The etiology of POI is heterogeneous. Recently, with the widespread use of whole-exome sequencing (WES), the DNA repair genes, especially for those involved in meiosis progress, were enriched in the causative gene spectrum of POI. In this study, through the largest in-house WES database of 1,030 patients with sporadic POI, we identified two novel homozygous variations in HSF2BP (c.382T>C, p.C128R; c.557T>C, p.L186P). An in vitro functional study revealed that both variations impaired the nuclear location of HSF2BP and affected its DNA repair capacity. Our studies highlighted the essential role of meiotic homologous recombination genes in the pathogenesis of sporadic POI.

Introduction

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is defined by depletion of ovarian function before the age of 40 years, characterized by amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea and elevated serum level of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (Webber et al., 2016). A recent meta-analysis found that 3.7% of women before 40 years of age are affected by POI (Golezar et al., 2019). The etiology of POI is heterogeneous. Genetic disorders, autoimmune disease, and iatrogenic factors account for nearly 50% of the patients, with the remaining half of the cases being idiopathic (Vujovic, 2009; De Vos et al., 2010). Nearly 20% of the cases have first- or second-degree relatives with POI. Therefore, genetic disorder is an indispensable factor in POI pathogenesis (Qin et al., 2015). Recently, with the widespread use of whole-exome sequencing (WES) in POI pedigrees, DNA repair genes, especially for those involved in the meiosis process, have been enriched in the spectrum of causative genes of POI (Jiao et al., 2018). However, the contribution of those genes in sporadic cases was rarely reported.

Meiosis is a crucial process during oogenesis. In the prophase of the first meiotic division, DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are generated by SPO11 (Keeney et al., 1997). After the modification by MRN, EXO1, and RPA (Soustelle et al., 2002; Lisby et al., 2004; Zakharyevich et al., 2010), the 3′-tailed single-strand DNA (ssDNA) of DSBs are recognized by BRCA2, RAD51, and DMC1, which execute the critical step of strand invasion, followed with homologous recombination (HR) and crossover formation (Barlow et al., 1997; Moens et al., 2002; Sharan et al., 2004). HSF2BP is a recently identified meiosis-specific protein, which interacted with BRCA2 and BRME1 to form a complex to mediate the recruitment of RAD51 and DMC1 to the meiotic recombination sites and facilitate the strand invasion (Zhang et al., 2020). Hsf2bp knockout female mice exhibited subfertility due to disruption of the recruitment of RAD51 and DMC1 onto ssDNA and delayed synapsis (Zhang et al., 2019). Recently, a homozygous missense variation in HSF2BP (HGNC:5226) was identified in a consanguineous family with POI (Felipe-Medina et al., 2020). However, the role of HSF2BP variations in sporadic POI pathogenesis was still unknown.

In the present study, through the variation screening of HSF2BP in the largest in-house WES database of 1,030 sporadic POI, two novel homozygous variations were identified. Functional studies showed both variants disturbed the nuclear localization of HSF2BP and affected its DNA repair capacity, highlighting the essential role of meiotic HR genes in the pathogenesis of sporadic POI.

Materials and Methods

Variation Screening of HSF2BP in the In-House Whole-Exome Sequencing Database of Premature Ovarian Insufficiency

A total of 1,030 females affected by idiopathic POI were recruited at the Center for Reproductive Medicine, Shandong University. The idiopathic POI was diagnosed by 1) primary or secondary amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea before 40 years of age; and 2) at least twice serum FSH >25 IU/L at an internal of 4–6 weeks. Patients with chromosomal abnormalities, ovarian surgery, chemo/radiotherapy, or autoimmune disease that might cause POI (such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune thyroiditis) were excluded.

Genomic DNA of the 1,030 patients was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Exome sequences were captured with SureSelect Target Enrichment system for Illumina Paired-End Sequencing Library (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and DNA sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina HiSeq, San Diego, CA, USA). Reads were mapped to the hg19 reference genome, and variants were called and annotated using Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK), ANNOVAR, and custom pipelines. The variants of HSF2BP were screened using the following strategies: 1) alter protein sequence (nonsense, missense, splicing-site variant, and coding indels); 2) allele frequencies <0.001 in the public databases 1000 Genomes, ESP6500, ExAC, and gnomAD; 3) variants predicted as deleterious variations by more than half of the software (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, MutationTaster, MutationAssessor, PROVEAN, and M-CAP); and 4) follow recessive inheritance pattern (homozygous or compound heterozygous). Then the variants were classified as pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), or variations of uncertain significance (VUS) according to the guidelines proposed by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) (Richards et al., 2015).

Plasmids Construction and Mutagenesis

The wild-type HSF2BP-FLAG plasmids were generated by inserting human HSF2BP cDNA tagged with FLAG into pcDNA3.1 vector. One non-pathogenic single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) with relatively high allele frequency in gnomAD was chosen as a negative control. The mutant and polymorphic HSF2BP-FLAG plasmids were generated using QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions, with the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1 and confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Cell Culture

HeLa cells (human cervix carcinoma cell line) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/high glucose (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco). KGN cells (human granulosa cell line) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F-12 (Gibco) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Immunofluorescence

HeLa cells and KGN cells were cultured in 24-well plates and transiently transfected with wild-type, mutant, and polymorphic HSF2BP-FLAG plasmids with the use of Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States). After being cultured for 48 h, the cells were divided into three groups: without treatment, treated with etoposide (ETO; 5 μg/ml, Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 1 h, and treated with mitomycin (MMC; 500 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) for 8 h. Then, the treated cells were cultured with a normal medium and recovered for a specific time at 37°C. Then, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Solarbio) for 20 min at room temperature. Then the slides were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, blocked with 10% bovine albumin for 1 h, incubated with anti-FLAG antibody (1:500 dilution, CST14793, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States) at 4°C overnight, followed with incubation with fluorescent secondary antibody for 1 h, and then treated with antifade mounting medium with DAPI (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Intervening phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) washes were performed after incubation when necessary. Images were captured with an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) BX61 microscope. The nuclear vs. cytoplasmic ratio of the HSF2BP proteins in HeLa cells and KGN cells was quantified by ImageJ software.

DNA Damage and Repair Assay

HeLa cells were cultured and transfected with wild-type or mutant HSF2BP-FLAG plasmids as mentioned above. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were incubated with ETO (5 μg/ml) for 1 h or MMC (500 ng/ml) for 8 h at 37°C to induce DNA damage. Then the culture medium with ETO or MMC was removed, and the cells were cultured with normal medium for a specific time at 37°C. The phosphorylation of the Ser-139 residue of histone variant H2AX (γH2AX; 1:1,000 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich, 05-636), which was a sensitive marker for DNA damage, was analyzed by Western blotting. Three independent experiments were conducted. Moreover, to compare the change of γH2AX level, we quantified the grayscale scores of Western blotting bands using ImageJ software and normalized the levels of γH2AX to the β-actin loading control in each group. The grayscale scores of γH2AX in the cells treated with ETO or MMC and recovered at specific time points were divided by those of untreated cells in each group. We compared the relative grayscale score between the wild-type and mutant groups at specific time points.

Results

Homozygous Missense Variations of HSF2BP Identified in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency Patients

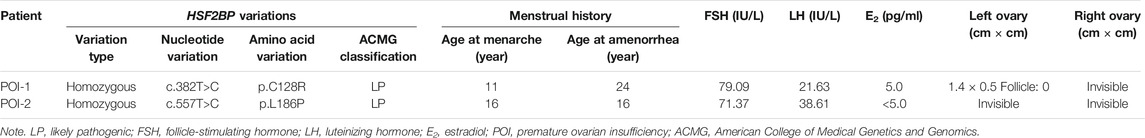

Through variation screening in the in-house WES database of sporadic POI, eight variations in HSF2BP (GenBank: NM_007031.2) have been identified. However, only two homozygous missense variations (following recessive inheritance pattern) were found, c.382T > C (p.C128R) and c.557T > C (p.L186P), which were with frequencies below 0.001 in the public databases 1000 Genomes, ExAC, and gnomAD, and were absent in the genomics database of 114,783 normal Han Chinese individuals (PGG.Han, http://www.pgghan.org). Both variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 1B), and the two amino acid sites were highly conserved among species (Figure 1C). According to the ACMG guideline, the two variants were classified as VUS.

FIGURE 1. HSF2BP variations identified in premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) patients. (A) The structure of HSF2BP protein and the localization of the two variations. (B) The DNA sequence chromatograms of two variations identified in present study. (C) The amino acid sites of the two variations were highly conserved among species.

Clinical Characteristics of Variation Carriers

Patient POI-1, who carried HSF2BP p.C128R, experienced menarche at 11 years old, underwent irregular menstrual cycle (2–12 months per menstrual cycle) since 13 years old, and suffered amenorrhea at 24 years of age. Patient POI-2, who carried HSF2BP p.L186P, experienced menarche at 16 years old, followed by an irregular menstrual cycle that ceased at the age of 18. Ultrasound examination showed the two patients had atrophic ovaries without follicles (Table 1).

Variations Impaired the Nuclear Localization and DNA Repair Capacity of HSF2BP

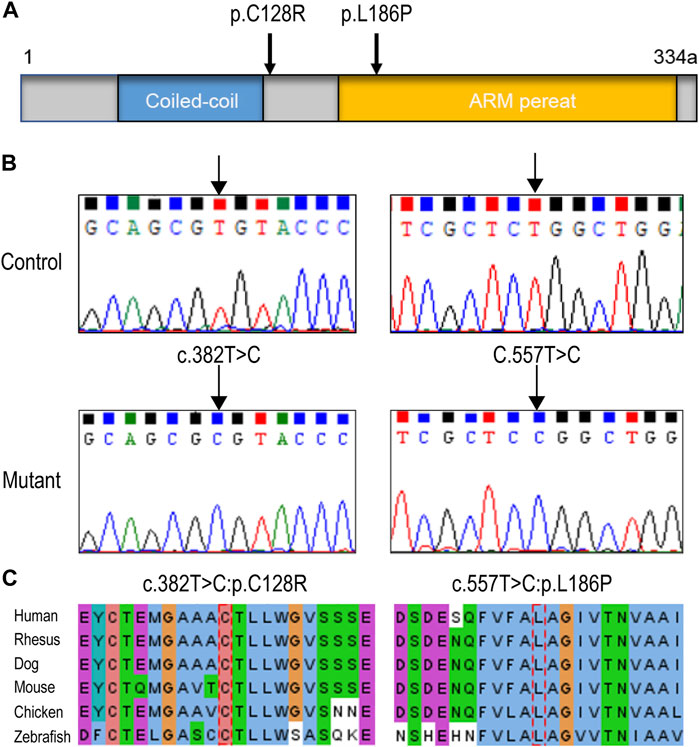

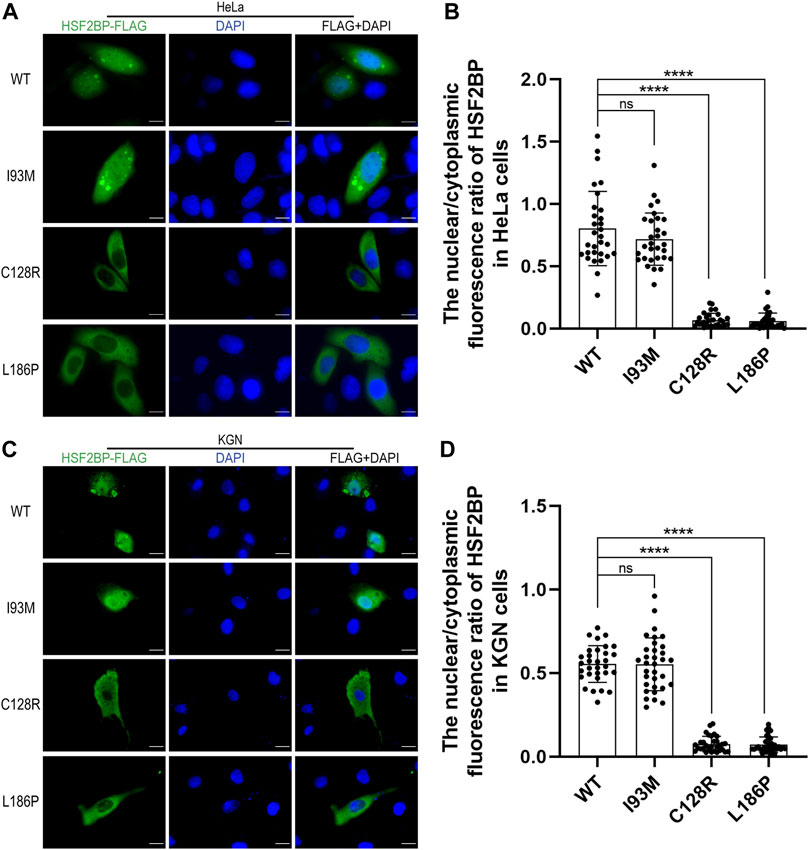

The wild-type or mutant HSF2BP-FLAG plasmids were transfected into HeLa cells and KGN cells, and the immunofluorescence against FLAG was performed to test the cellular localization of protein HSF2BP. The polymorphic variant I93M (rs200533753) was used as the negative control. The wild-type HSF2BP and I93M were expressed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of HeLa and KGN cells. However, the signals of two mutant proteins (C128R and L186P) localizing in the nucleus were significantly lower than those of the wild-type protein (Figure 2). Moreover, after treatment with ETO or MMC, the localization of mutant proteins in cells was not changed (Figure 3). These results suggested that the variations C128R and L186P impaired the nuclear location of HSF2BP, where its DNA repair function was proposed to be performed, and the disturbed nuclear localization of mutant HSF2BP was not affected by DNA damaging agents.

FIGURE 2. The two variations impaired the nuclear localization of HSF2BP. (A,C) Immunofluorescence against FLAG (green) in HeLa cells (A) and KGN cells (C) overexpressing wild-type (WT) or mutant HSF2BP (I93M, C128R, and L186P) plasmids. The mutant I93M was a polymorphism variant used as a control here. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars are 10 μm. (B,D) The nuclear vs. cytoplasmic ratio of HSF2BP proteins in HeLa cells (B) and KGN cells (D). The differences of nuclear vs. cytoplasmic ratio between wild-type and mutant C128R or L186P groups were statistically significant. ****p < 0.0001.

FIGURE 3. The disturbed nuclear localization of mutant HSF2BP was not affected by DNA damaging agents. (A,B) Immunofluorescence against FLAG (green) in HeLa cells overexpressing wild-type (WT) or mutant HSF2BP (I93M, C128R, and L186P) plasmids with etoposide (ETO) (A) or mitomycin (MMC) (B) treatment. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars are 10 μm. (C,D) The nuclear vs. cytoplasmic ratio of HSF2BP proteins in HeLa cells with ETO (C) or MMC (D) treatment and recovery at specific time points.

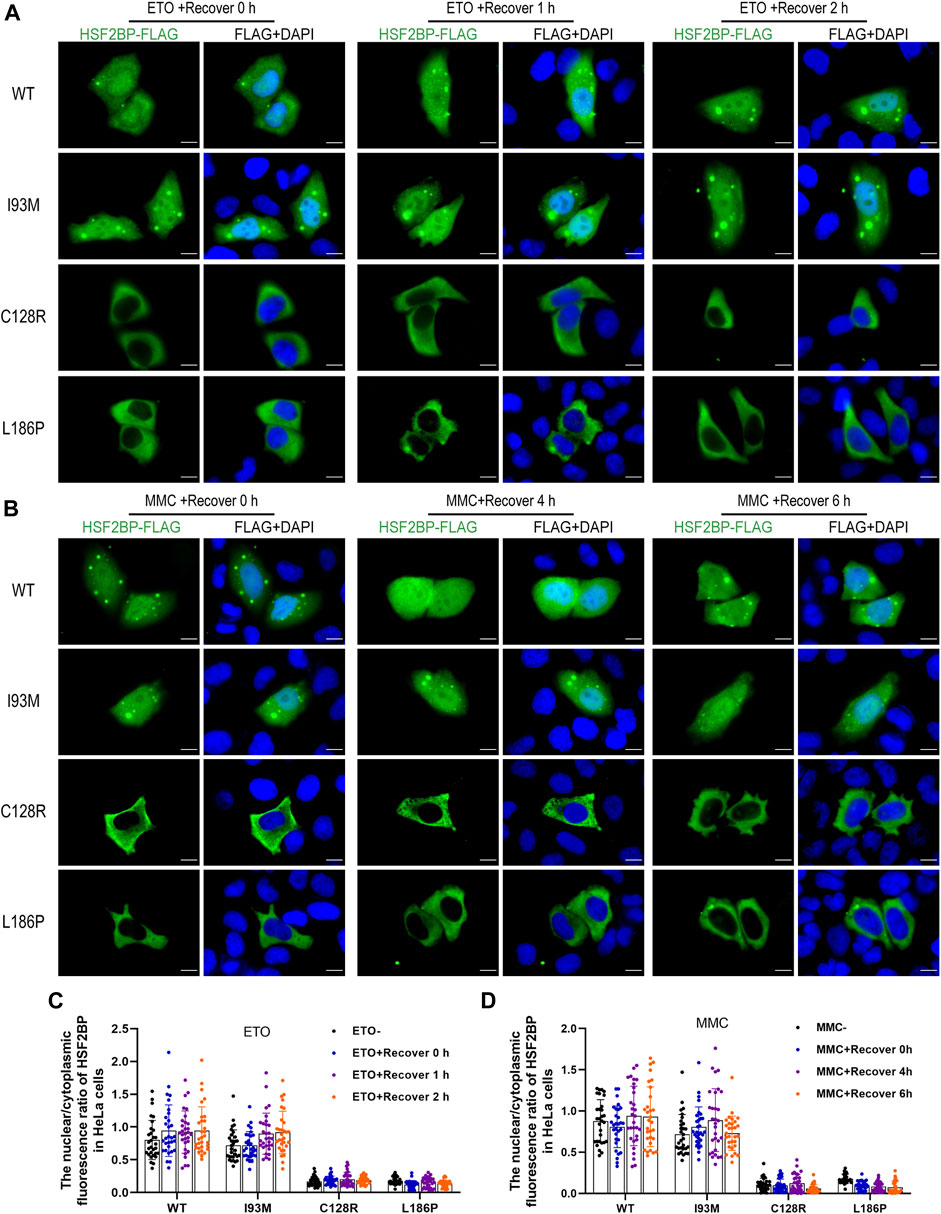

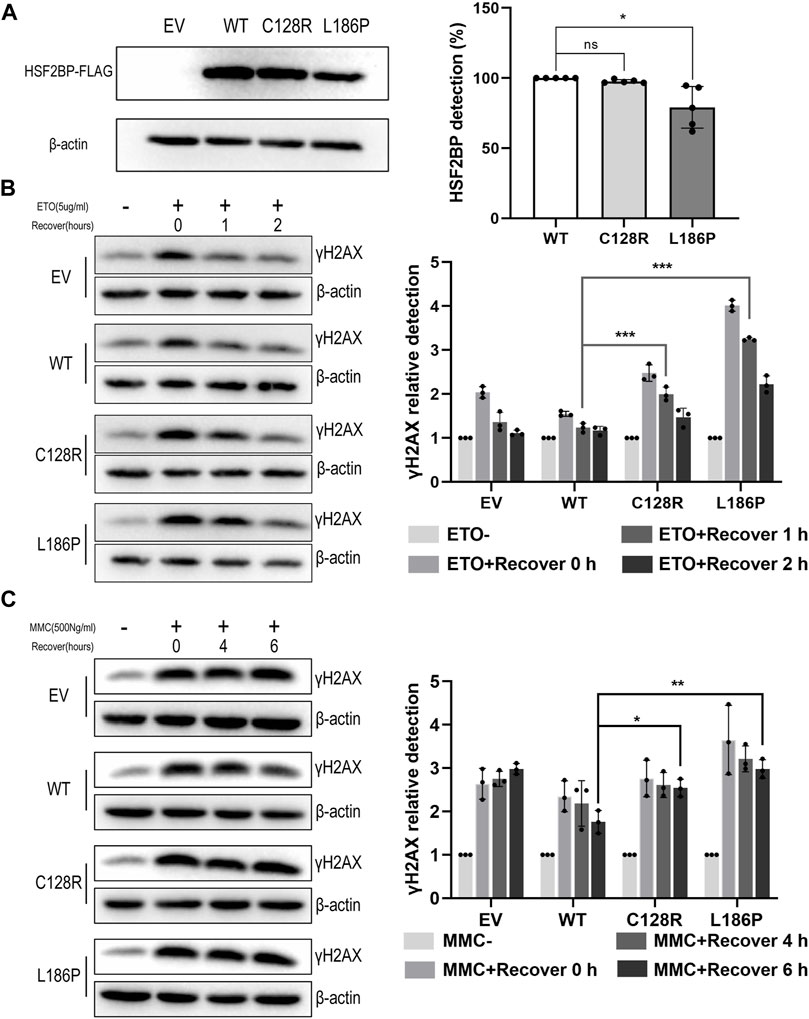

To elucidate whether the two variations impaired the DNA repair capacity of HSF2BP, DNA damage assays were performed. The result showed that the level of γH2AX in HeLa cells overexpressing wild-type HSF2BP increased immediately after ETO treatment and decreased to the untreated level after recovery for 1 h. Whereas, the γH2AX level in cells overexpressing mutant HSF2BP was significantly higher than that in the wild-type group after recovery for 1 h (Figure 4B). Similar results were observed in the MMC treatment groups, in which the γH2AX level in cells overexpressing mutant HSF2BP was significantly higher than that in wild-type cells after recovery for 6 h (Figure 4C), indicating that the mutant HSF2BP had impaired DNA repair capacity. Considering that HSF2BP was especially expressed in germ cells, the ultimately repaired DNA damage, demonstrated by decreased γH2AX level after 2 h of recovery in ETO-treated cells, might be caused by the endogenous DNA repair mechanism of HeLa cells. Then, with those functional studies, both variations were classified as LP according to the ACMG guideline (Table 1).

FIGURE 4. The variation C128R and L186P impaired the DNA repair capacity of HSF2BP. (A) The expression level of wild-type (WT) and mutant HSF2BP-FLAG (C128R and L186P) were tested by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control. Graph on the right represents the relative quantification of the immunoblotting. *p < 0.05. (B,C) The γH2AX level was detected by Western blotting in HeLa cells overexpressing empty vector (EV), wild-type (WT), or mutant HSF2BP-FLAG (C128R and L186P) with or without etoposide (ETO) (B) or mitomycin (MMC) (C) treatment. The relative grayscale scores of γH2AX in the cells overexpressing mutant HSF2BP (C128R and L186P) were compared with those overexpressing wild-type (WT) HSF2BP at specific recovery time points after ETO or MMC treatment (the grayscale of no treatment was considered as one in each group). β-Actin was used as the loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

In the present study, two novel pathogenic homozygous variations of HSF2BP were identified in two patients with sporadic POI. Functional studies revealed the variations adversely affected the DNA repair capacity of HSF2BP due to disturbed nuclear localization, highlighting the essential role of meiotic HR genes in the pathogenesis of sporadic POI.

HSF2BP is an interactor of the heat shock response transcription factor HSF2 and is predominately expressed in germline cells (Yoshima et al., 1998; Brandsma et al., 2019). Recent studies found that HSF2BP interacted with BRME1 to form a complex that facilitated BRCA2-mediated recruitment of RAD51 and DMC1 onto ssDNA and strand invasion, which was essential for meiotic HR and crossover formation (Zhang et al., 2020). The knockout female mice of Hsf2bp exhibited a dramatically reduced number of oocytes (Zhang et al., 2019). In a consanguineous family with three cases of POI, homozygous variation p.S167L in HSF2BP was firstly reported. The point mutant mice Hsf2bpS167L/S167L showed reduced fertility with smaller litter sizes. With the observation that homozygous oocytes had a reduced number of RAD51/DMC1 foci on DSBs and subsequent reduction in the number of crossovers, HSF2BP p.S167L was assumed to cause POI by altered meiotic recombination (Felipe-Medina et al., 2020).

In the current study, with the in-house WES database of sporadic POI, two novel homozygous missense variations in HSF2BP (c.382T>C, p.C128R; c.557T>C, p.L186P) were identified, providing the evidence of HSF2BP variations participating in the pathogenesis of sporadic POI. A previously reported variation p.S167L resulted in the reduced protein level of HSF2BP and subsequent insufficient BRME1, RAD51, and DMC1 localizing at DSBs during meiotic recombination (Felipe-Medina et al., 2020). However, our in vitro studies merely found a modest reduction protein expression level of HSF2BP p.C128R and p.L186P (Figure 4A), indicating that their pathogenic effects on HSF2BP were different from those of p.S167L. Intriguingly, the hypothesis was confirmed by the observation that HSF2BP protein with variation p.C128R or p.L186P was barely transferred into the nuclei. A further study demonstrated that the DNA repair capacities of mutant HSF2BP were lower than those of the wild type. Therefore, HSF2BP p.C128R and p.L186P might lead to dysfunctional oogenesis by inefficient meiotic recombination due to disturbed nuclear localization of HSF2BP. Moreover, with the observation that the cells overexpressing mutant HSF2BP had increased sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, the role of accumulated DNA damage in somatic cells cannot be excluded in the pathogenesis of POI, especially for the cells during early embryo development (Yuen et al., 2012).

The establishment of the ovarian follicle pool is initiated by the primordial germ cells (PGC) migrating to the genital ridge; after PGC proliferation and meiosis prophase I, oocytes arrest at the diplotene stage in the form of primordial follicles, which determined the ovarian reserve (Baerwald et al., 2012). Meiotic HR is essential for genetic stability and diversity of oocytes, which also ensure the proper separation of homologous chromosomes during division (Baudat et al., 2013). Meiotic defects would cause accelerated oocytes apoptosis, resulting in diminished ovarian reserve even POI (Handel and Schimenti, 2010). Recent studies with next-generation sequencing extremely expanded the spectrum of POI candidate genes (França and Mendonca, 2020). Intriguingly, the genes involved in meiotic processes were intensively reported, such as DSB end processing genes EXO1 (HGNC:3511), MND1 (HGNC:24839), and MEIOB (HGNC:28569) (Caburet et al., 2019; Jolly et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2020); HR genes RAD51 (HGNC:9817), BRCA2 (HGNC:1101), MSH4 (HGNC:7327), and MSH5 (HGNC:7328) (Carlosama et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2020); and synaptonemal complex genes SYCE1 (HGNC:28852), C14ORF39 (HGNC:19849), and STAG3 (HGNC:11356) (de Vries et al., 2014; Jaillard et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2021). The identification of HSF2BP further highlighted the essential role of meiotic HR genes in the pathogenesis of POI, for both familial and sporadic cases.

Intriguingly, recent studies found that the somatic cells overexpressing HSF2BP were sensitive to DNA interstrand crosslink, which increased cancer susceptibility (Brandsma et al., 2019; Sato et al., 2020). However, the two patients in the present study had no history of tumors at the time of the investigation. That might be caused by the observation that the two variations did not influence the expression level and tissue localization of HSF2BP. Even so, longtime follow-up of tumors for the HSF2BP variation carriers should be suggested.

In conclusion, two novel pathogenic homozygous variations of HSF2BP were identified in sporadic POI cases, further expanded the spectrum of POI causative genes, and highlighted the essential role of meiotic HR genes in sporadic POI pathogenesis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: SCV001832610.1; SCV001832609.1 (ClinVar, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/).

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Institutional Review Board of Reproductive Medicine of Shandong University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

YQ and TG designed the study. SL and WX performed the experiments and collected the data. WX, BX, SG, QZ, and TG were involved in the sample collection, whole exome sequencing, and screening for the mutations. TG and SL drafted the manuscript. YQ modified the manuscript. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos 2018YFC1003702 and 2017YFC1001100); The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 32070847, 81771541, and 81671413); Basic Science Center Program of NFSC (No. 31988101); Taishan Scholars Program for Young Experts of Shandong Province (No. tsqn20161069); and Shandong University Education Foundation Public Welfare Project (No. 23460047102008).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.768123/full#supplementary-material

References

Baerwald, A. R., Adams, G. P., and Pierson, R. A. (2012). Ovarian Antral Folliculogenesis during the Human Menstrual Cycle: a Review. Hum. Reprod. Update 18 (1), 73–91. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr039

Barlow, A. L., Benson, F. E., West, S. C., and Hultén, M. A. (1997). Distribution of the Rad51 Recombinase in Human and Mouse Spermatocytes. EMBO J. 16 (17), 5207–5215. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.17.5207

Baudat, F., Imai, Y., and de Massy, B. (2013). Meiotic Recombination in Mammals: Localization and Regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14 (11), 794–806. doi:10.1038/nrg3573

Brandsma, I., Sato, K., van Rossum-Fikkert, S. E., van Vliet, N., Sleddens, E., Reuter, M., et al. (2019). HSF2BP Interacts with a Conserved Domain of BRCA2 and Is Required for Mouse Spermatogenesis. Cel Rep. 27 (13), 3790–3798. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.096

Caburet, S., Todeschini, A.-L., Petrillo, C., Martini, E., Farran, N. D., Legois, B., et al. (2019). A Truncating MEIOB Mutation Responsible for Familial Primary Ovarian Insufficiency Abolishes its Interaction with its Partner SPATA22 and Their Recruitment to DNA Double-Strand Breaks. EBioMedicine 42, 524–531. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.075

Carlosama, C., Elzaiat, M., Patiño, L. C., Mateus, H. E., Veitia, R. A., and Laissue, P. (2017). A Homozygous Donor Splice-Site Mutation in the Meiotic Gene MSH4 Causes Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26 (16), 3161–3166. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddx199

De Vos, M., Devroey, P., and Fauser, B. C. (2010). Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. The Lancet 376 (9744), 911–921. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60355-8

de Vries, L., Behar, D. M., Smirin-Yosef, P., Lagovsky, I., Tzur, S., and Basel-Vanagaite, L. (2014). Exome Sequencing Reveals SYCE1 Mutation Associated with Autosomal Recessive Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99 (10), E2129–E2132. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1268

Fan, S., Jiao, Y., Khan, R., Jiang, X., Javed, A. R., Ali, A., et al. (2021). Homozygous Mutations in C14orf39/SIX6OS1 Cause Non-obstructive Azoospermia and Premature Ovarian Insufficiency in Humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108 (2), 324–336. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.01.010

Felipe-Medina, N., Caburet, S., Sánchez-Sáez, F., Condezo, Y. B., de Rooij, D. G., Gómez-H, L., et al. (2020). A Missense in HSF2BP Causing Primary Ovarian Insufficiency Affects Meiotic Recombination by its Novel Interactor C19ORF57/BRME1. eLife 9, e56996. doi:10.7554/eLife.56996

França, M. M., and Mendonca, B. B. (2020). Genetics of Primary Ovarian Insufficiency in the Next-Generation Sequencing Era. J. Endocr. Soc. 4 (2), bvz037. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvz037

Golezar, S., Ramezani Tehrani, F., Khazaei, S., Ebadi, A., and Keshavarz, Z. (2019). The Global Prevalence of Primary Ovarian Insufficiency and Early Menopause: a Meta-Analysis. Climacteric 22 (4), 403–411. doi:10.1080/13697137.2019.1574738

Guo, T., Zhao, S., Zhao, S., Chen, M., Li, G., Jiao, X., et al. (2017). Mutations in MSH5 in Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26 (8), 1452–1457. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddx044

Handel, M. A., and Schimenti, J. C. (2010). Genetics of Mammalian Meiosis: Regulation, Dynamics and Impact on Fertility. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11 (2), 124–136. doi:10.1038/nrg2723

Jaillard, S., McElreavy, K., Robevska, G., Akloul, L., Ghieh, F., Sreenivasan, R., et al. (2020). STAG3 Homozygous Missense Variant Causes Primary Ovarian Insufficiency and Male Non-obstructive Azoospermia. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 26 (9), 665–677. doi:10.1093/molehr/gaaa050

Jiao, X., Ke, H., Qin, Y., and Chen, Z.-J. (2018). Molecular Genetics of Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 29 (11), 795–807. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2018.07.002

Jolly, A., Bayram, Y., Turan, S., Aycan, Z., Tos, T., Abali, Z. Y., et al. (2019). Exome Sequencing of a Primary Ovarian Insufficiency Cohort Reveals Common Molecular Etiologies for a Spectrum of Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 104 (8), 3049–3067. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00248

Keeney, S., Giroux, C. N., and Kleckner, N. (1997). Meiosis-specific DNA Double-Strand Breaks Are Catalyzed by Spo11, a Member of a Widely Conserved Protein Family. Cell 88 (3), 375–384. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81876-0

Lisby, M., Barlow, J. H., Burgess, R. C., and Rothstein, R. (2004). Choreography of the DNA Damage Response. Cell 118 (6), 699–713. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.015

Luo, W., Guo, T., Li, G., Liu, R., Zhao, S., Song, M., et al. (2020). Variants in Homologous Recombination Genes EXO1 and RAD51 Related with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105 (10), e3566–e3574. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa505

Moens, P. B., Kolas, N. K., Tarsounas, M., Marcon, E., Cohen, P. E., and Spyropoulos, B. (2002). The Time Course and Chromosomal Localization of Recombination-Related Proteins at Meiosis in the Mouse Are Compatible with Models that Can Resolve the Early DNA-DNA Interactions without Reciprocal Recombination. J. Cel Sci 115 (Pt 8), 1611–1622. doi:10.1242/jcs.115.8.1611

Qin, Y., Jiao, X., Simpson, J. L., and Chen, Z.-J. (2015). Genetics of Primary Ovarian Insufficiency: New Developments and Opportunities. Hum. Reprod. Update 21 (6), 787–808. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmv036

Qin, Y., Zhang, F., and Chen, Z.-J. (2019). BRCA2 in Ovarian Development and Function. N. Engl. J. Med. 380 (11), 1086–1087. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1813800

Richards, S., Aziz, N., Bale, S., Bick, D., Das, S., Gastier-Foster, J., et al. (2015). Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: a Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 17 (5), 405–424. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30

Sato, K., Brandsma, I., van Rossum-Fikkert, S. E., Verkaik, N., Oostra, A. B., Dorsman, J. C., et al. (2020). HSF2BP Negatively Regulates Homologous Recombination in DNA Interstrand Crosslink Repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 (5), 2442–2456. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz1219

Sharan, S. K., Pyle, A., Coppola, V., Babus, J., Swaminathan, S., Benedict, J., et al. (2004). BRCA2 Deficiency in Mice Leads to Meiotic Impairment and Infertility. Development (Cambridge, England) 131 (1), 131–142. doi:10.1242/dev.00888

Soustelle, C., Vedel, M., Kolodner, R., and Nicolas, A. (2002). Replication Protein A Is Required for Meiotic Recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 161 (2), 535–547. doi:10.1093/genetics/161.2.535

Vujovic, S. (2009). Aetiology of Premature Ovarian Failure. Menopause Int. 15 (2), 72–75. doi:10.1258/mi.2009.009020

Webber, L., Davies, M., Anderson, R., Bartlett, J., Braat, D., Cartwright, B., et al. (2016). ESHRE Guideline: Management of Women with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. 31 (5), 926–937. doi:10.1093/humrep/dew027

Yoshima, T., Yura, T., and Yanagi, H. (1998). Novel Testis-specific Protein that Interacts with Heat Shock Factor 2. Gene 214 (1-2), 139–146. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00208-x

Yuen, W. S., Merriman, J. A., O'Bryan, M. K., and Jones, K. T. (2012). DNA Double Strand Breaks but Not Interstrand Crosslinks Prevent Progress through Meiosis in Fully Grown Mouse Oocytes. PloS one 7 (8), e43875. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043875

Zakharyevich, K., Ma, Y., Tang, S., Hwang, P. Y.-H., Boiteux, S., and Hunter, N. (2010). Temporally and Biochemically Distinct Activities of Exo1 during Meiosis: Double-Strand Break Resection and Resolution of Double Holliday Junctions. Mol. Cel. 40 (6), 1001–1015. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.032

Zhang, J., Fujiwara, Y., Yamamoto, S., and Shibuya, H. (2019). A Meiosis-specific BRCA2 Binding Protein Recruits Recombinases to DNA Double-Strand Breaks to Ensure Homologous Recombination. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 722. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08676-2

Keywords: premature ovarian insufficiency, homologous recombination, HSF2BP, whole-exome sequencing, gene mutation

Citation: Li S, Xu W, Xu B, Gao S, Zhang Q, Qin Y and Guo T (2022) Pathogenic Variations of Homologous Recombination Gene HSF2BP Identified in Sporadic Patients With Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:768123. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.768123

Received: 31 August 2021; Accepted: 14 December 2021;

Published: 31 January 2022.

Edited by:

Fei Gao, State Key Laboratory of Stem Cell and Reproductive Biology, Institute of Zoology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Judith Yanowitz, Magee-Womens Research Institute, United StatesJitu W. George, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United States

Copyright © 2022 Li, Xu, Xu, Gao, Zhang, Qin and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ting Guo, Z3RseXAyMDA4QDEyNi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Shan Li1,2,3,4,5†

Shan Li1,2,3,4,5† Yingying Qin

Yingying Qin Ting Guo

Ting Guo